Transpapillary selective bile duct cannulation technique: Review of Japanese randomized controlled trials since 2010 and an overview of clinical results in precut sphincterotomy since 2004

Abstract

In 1970, a Japanese group reported the first use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which is now carried out worldwide. Selective bile duct cannulation is a mandatory technique for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP. Development of the endoscope and other devices has contributed to the extended use of ERCP, which has become a basic procedure to diagnose and treat pancreaticobiliary diseases. Various techniques related to selective bile duct cannulation have been widely applied. Although the classical contrast medium injection cannulation technique remains valuable, use of wire-guided cannulation has expanded since the early 2000s, and the technique is now widely carried out in the USA and Europe. Endoscopists must pay particular attention to a patient's condition and make an attendant choice about the most effective technique for selective bile duct cannulation. Some techniques have the potential to shorten procedure time and reduce the incidence of adverse events, particularly post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, a great deal of experience is required and endoscopists must be skilled in a variety of techniques. Although the development of the transpapillary biliary cannulation approach is remarkable, it is important to note that, to date, there have been no reports of transpapillary cannulation preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. In the present article, selective bile duct cannulation techniques in the context of recent Japanese randomized controlled trials and cases of precut sphincterotomy are reviewed and discussed.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the standard procedure for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for pancreatobiliary diseases. Selective bile duct cannulation (SBDC) is the most basic and important technique for carrying out diagnostic and therapeutic biliary interventions. In 1968, McCune et al. reported the first use of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography.1 Two years later, in 1970, Takagi et al. reported the first use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography.2 Classen and Demling3 Kawai et al.,4 and Sohma et al.5 reported endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in 1974. Today, EST and EST-associated procedures play a central role in therapeutic biliary intervention. However, EST could not be carried out were it not for the development of SBDC. With regard to SBDC, the technical success rate for trainees is suggested to be 80–90%; for expert endoscopists, the success rate climbs to 95–100%.6 Although there have been major advances in techniques, devices, and sophistication of endoscopes, no standard SBDC technique has been established and it is still a challenging procedure in difficult cases.7 Moreover, difficult or failed SBDC is sometimes associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP). The success rate of SBDC is related to three factors: type of catheter, cannulation method, and skill of the endoscopist and assistant. Complication rates are also related to three factors: patient factors (e.g. individual anatomy), procedure factors, and expertise of endoscopist and assistant.7

Various endoscopic techniques for SBDC have been reported in the literature,6 including standard techniques (e.g. contrast injection technique, wire-guided cannulation [WGC]), pancreatic guidewire technique (e.g. double guidewire technique), precut sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillectomy,6 endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous procedure, and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage-guided procedure. In particular, rescue techniques such as precut sphincterotomy, pancreatic guidewire technique, or double guidewire cannulation are sometimes carried out after unintentional injection of contrast or insertion of a guidewire into the main pancreatic duct. Increased rates of successful SBDC and decreased rates of PEP are the primary objective.

Pancreatic guidewire technique and double guidewire technique

Use of the pancreatic guidewire technique also facilitates SBDC as a salvage technique. In 1998, Dumonceau et al.8 reported the first use of the pancreatic guidewire technique for failed SBDC in a patient with Billroth I reconstruction. In 2001, Gotoh et al.9 described the yield of the pancreatic guidewire technique. In 2003, Maeda et al.10 compared the pancreatic guidewire technique to conventional cannulation with contrast medium injection. Success rates of SBDC were 93% and 58%, respectively. No PEP developed in either group. When an ERCP catheter or sphincterotome is used for SBDC, this technique is called the pancreatic guidewire technique. In contrast, when WGC is used for SBDC, this technique is called the double guidewire technique. These techniques are useful for difficult SBDC with: (i) mobile Vater's ampulla; (ii) swelling of oral protrusion; (iii) a long narrow distal segment; or (iv) a bending narrow distal segment. These techniques also facilitate the use of a pancreatic stent.

Current status of selective bile duct cannulation

Recently, Japanese groups have conducted three randomized controlled trials (RCT) regarding SBDC. In 2010, Ito et al.11 described the Sendai RCT, a study that compared the use of a pancreatic stent versus no-pancreatic stent (a single-center, prospective, randomized study of pancreatic stent use during pancreatic guidewire technique by multiple endoscopists). The authors demonstrated a significant PEP prophylactic effect of pancreatic stent use in patients who underwent pancreatic guidewire cannulation (2.9% vs 23.0%, relative risk [RR] 0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.016–0.95). Furthermore, the study determined that no pancreatic stenting was the only significant risk factor for PEP (RR 16; 95% CI, 1.3–193, P = 0.071) by multivariate analysis. Accordingly, the authors recommended the use of a pancreatic stent during pancreatic guidewire procedures.

In 2012, we reported a RCT for WGC vs non-guidewire cannulation, which was known as the BIDMEN study (a multicenter, prospective, randomized study of selective bile duct cannulation carried out by multiple endoscopists).7 Success rate of SBDC within 10 min was not significantly different between the with-guidewire group and the without-guidewire group (70.6% vs 70.4%). However, WGC led to significantly shorter SBDC and fluoroscopic times during the procedure. Therefore, the BIDMEN study recommended WGC in terms of both SBDC and fluoroscopic time.

In 2013, Kobayashi et al.12 reported on a RCT for conventional SBDC versus WGC in a multicenter setting. Success rate of SBDC within 30 min was not significantly different between the conventional SBDC group and the WGC group (83% vs 87%, P = 0.40). PEP rates were similar, including occurrence and severity (6.3% vs 6.1%; P = 0.95). Furthermore, the study determined that unintentional contrast injection or guidewire insertion into the pancreatic duct was the only significant risk factor for PEP (RR 8.70; 95% CI, 2.46–30.81, P = 0.001), as determined through multivariate analysis.

In 2015, Sasahira et al.13 described a RCT for early use of double guidewire cannulation versus repeated single WGC, known as the EDUCATION trial (a multicenter, prospective, randomized study of double guidewire cannulation carried out by multiple endoscopists). In this study, randomization was done when the guidewire was unintentionally inserted into the pancreatic duct. Success rate of SBDC within 10 attempts and 10 min was not significantly different between the double guidewire cannulation group and the repeated single guidewire cannulation group (75% vs 70%; RR 1.07; 95% CI, 0.93–1.24; P = 0.42). PEP rates were similar, including incidence and severity (20% vs 17%; RR 1.17; 95% CI, 0.71–1.94, P = 0.53). The EDUCATION trial recommended repeated single WGC as conversion to a double guidewire technique; neither technique, however, facilitated selective bile duct cannulation nor decreased PEP incidence.

Taken together, the recommendation of these four Japanese RCT regarding SBDC is that WGC should be the first treatment choice. If unintentional insertion of the guidewire occurs, repeated single WGC is recommended. In addition, use of a pancreatic stent is recommended to decrease the risk of PEP.

Wire-guided cannulation

In 1987, Siegel and Pullano14 reported the first use of WGC for SBDC. The WGC technique is widely used with the development of devices, especially guidewire. Most RCT7, 12, 15-20 state that WGC facilitates primary SBDC and decreases the incidence of PEP (Table 1). However, recent Japanese RCT7, 12, 20 showed that the success rate of SBDC, and the occurrence and severity of PEP were not significantly different between the non-WGC group and the WGC group (Table 1). These conflicting results were caused by skill bias of endoscopist(s) and/or degree of backward oblique angle duodenoscope. Interestingly, Japanese RCT7, 12, 20 used a 15-degree backward oblique angle duodenoscope, which is the standard ERCP scope in Japan. In contrast, in Western countries, a five-degree backward oblique angle duodenoscope is currently used as a standard ERCP scope. We previously reported that the 15-degree backward oblique angle duodenoscope yielded a superior SBDC rate than did the five-degree backward oblique angle duodenoscope; it also did not require the bow-up function of the sphincterotome.21 Thus, we should use a 15-degree backward oblique angle duodenoscope during SBDC with emphasis on the ability to adjust to the axis of the bile duct.21, 22

| Author | Ref. | Year | Study design | No. of institutions | No. of endoscopists | Enrolled patients | Time limit | Attempts limit | MPD cannulation limit | Primary SBDC (%) | Primary SBDC time | Fluoroscopy time for primary SBDC | PEP | Angle of duodenoscope (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lella F | 15 | 2004 | S vs S + GW | 1 | 1 | 200 vs 200 | None | None | (-) | 97.5% vs 98.5% (NS) | 39 vs 37 min (medium) (NS) | (-) | 8 vs 0 (P < 0.01) | 5 |

| Artifon EL | 16 | 2007 | S vs S + GW | 1 | 1 | 150 vs 150 | (-) | 10 | (-) | 72% vs 88% (P < 0.001) | (-) | (-) | 25 vs 13 (P = 0.037) | 5 |

| Bailey AA | 17 | 2008 | S vs S + GW | 1 | 2 and fellows | 211 vs 202 | 10 min | (-) | (-) | 73.9% vs 82% (P < 0.03) | 150 vs 120 sec (median) (NS) | (-) | 13 vs 16 (NS) | (-) |

| 5 min fellow | ||||||||||||||

| Katsinelos P | 18 | 2008 | C vs C + GW | 1 | 1 | 165 vs 167 | 10 min | (-) | (-) | 53.9% vs 81.4% (P < 0.001) | 3.53 vs 4.48 min (average) (P = 0.04) | (-) | 13 vs 9 (NS) | (-) |

| Lee TH | 19 | 2009 | S vs S + GW | 1 | 1 | 150 vs 150 | 10 min | (-) | 5 | 82% vs 88% (NS) | (-) | (-) | 17 vs 3 (P = 0.001) | 5 |

| Nambu T | 20 | 2011 | C vs S + GW | 1 | Multiple | 86 vs 86 | 10 min | (-) | (-) | 73.8% vs 77.9% (NS) | (-) | (-) | 5 vs 2 (NS) | 15 |

| Kawakami H | 7 | 2012 | C vs C + GW vs S vs S + GW | 15 | Multiple | 101 vs 102 vs 100 vs 97 | 10 min | (-) | (-) | 71.3% vs 73.5% vs 68% vs 69.1% (NS) | 206 vs 172.8 vs 236.7 vs 176.2 sec (average) (NS) | 57.5 vs 38.7 vs 62.7 vs 34.1 sec (average) (NS) | 4 vs 6 vs 2 vs 2 (NS) | 15 |

| Kobayashi G | 12 | 2013 | C vs C + GW | 9 | Multiple | 159 vs 163 | 30 min | (-) | (-) | 87% vs 83% (NS) | 7.2± vs 7.4±8.3 min (mean) (NS) | (-) | 10 vs 10 (NS) | 15 |

- a S, sphincterotome; C. ERCP catheter; GW, guidewire; (-), not available; NS, not significant; SBDC, selective bile duct cannulation; PEP, post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Types of precut sphincterotomy techniques

In 1978, Caletti et al. reported the first precut sphincterotomy for difficult SBDC.23 To date, several precut techniques have been described, and there are many variations of the technique. The most common precut techniques are precut papillotomy, precut fistulotomy, and transpancreatic sphincterotomy.6, 24 In general, precut papillotomy is referred to as conventional precut sphincterotomy. However, in clinical settings, precut techniques are usually categorized into two groups according to the device used: needle-knife or sphincterotome (papillotome). Additionally, in most cases, device selection is highly dependent on individual anatomy, such as morphology of Vater's papilla. For small papilla, flat papilla, intra-diverticular papilla, or small oral protrusion, transpancreatic sphincterotomy using a standard traction papillotome (sphincterotomy) can be carried out more safely compared with precut papillotomy or precut fistulotomy. Conversely, for protruding papilla or swelling papilla after multiple attempts, precut papillotomy or precut fistulotomy would be considered more appropriate.

Standard techniques of precut sphincterotomy

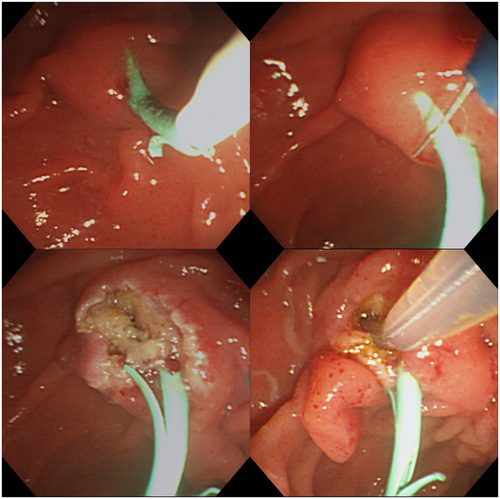

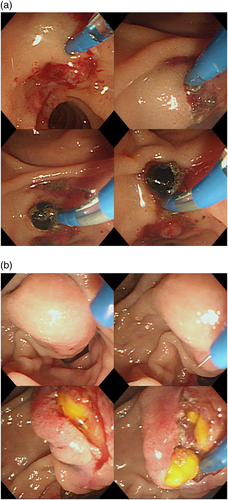

Precut papillotomy (Figs 1, 2) is done using a needle-knife. The incision is started at the orifice and then extended upward to the 11–12 o'clock position (below-upward); alternatively, the incision may be started above the orifice (the papillary sphincter or intraduodenal segment of the bile duct) at the 11–12 o'clock position and then extended downward to the orifice (above-downward). However, there is no consensus regarding the optimal direction for precut sphincterotomy. The incision is carried out in a layer-by-layer fashion24, 25 and is extended by cutting in 1- to 2-mm increments. In general, the biliary orifice is recognized by its whitish, slit appearance. The biliary sphincter muscle is sometimes identified as having a whitish, onion-skin appearance.25

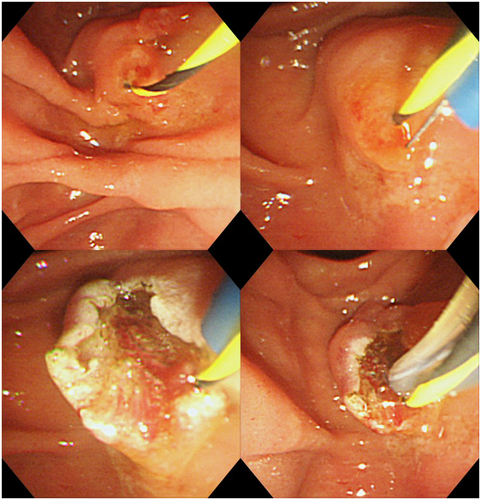

The precut fistulotomy (Figs 3, 4) technique is similar to above-downward precut papillotomy. The most important aspect of this technique is never to interfere with the orifice.26 This technique is useful for: (i) an impacted biliary stone at the orifice or terminal bile duct; (ii) a non-exposed tumor at Vater's ampulla; or (iii) marked swelling of oral protrusion or terminal bile duct with obstructive jaundice/iatrogenic edema during multiple attempts of SBDC.

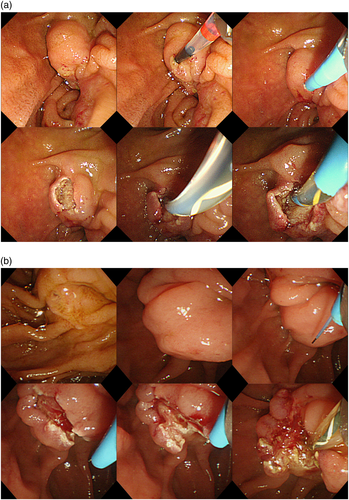

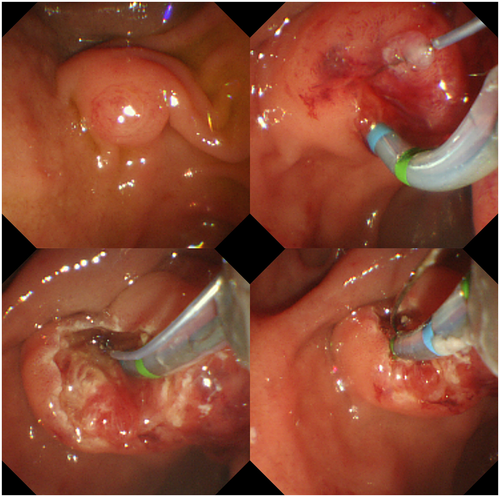

The transpancreatic sphincterotomy (Fig. 5) technique is similar to EST using a papillotome (sphincterotome). First, an incision is started and extended toward the 11 o'clock position. Regarding depth and direction of the incision, this technique is technically easy compared with precut papillotomy or precut fistulotomy, even for a trainee. Theoretically, the risk of perforation is lower compared with precut papillotomy and precut fistulotomy. However, the incision used for this technique is not done in a layer-by-layer method.

Precut sphincterotomy: Overview of clinical results since 2004

There are many clinical studies of precut sphincterotomy. In 2005, Freeman and Guda6 reviewed clinical results of precut sphincterotomy from 1986 to early 2004. Precut sphincterotomy was selected and carried out in conjunction with 4–38% of all failed SBDC or EST. Their review states a success rate of 35–96% and a complication rate of 0–18%.

We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed from 2004 to September 2015 using the following keywords: precut, precut sphincterotomy, ERCP precut, precut papillotomy, needle-knife sphincterotomy, needle-knife fistulotomy, or transpancreatic precut. All relevant articles irrespective of language, type of publication, or publication status were included in our analysis. Initially, the titles and abstracts were screened. As a result, 354 articles in total were gathered. Of these articles, 94 were not related to gastroenterology and 11 were from the field of gastroenterology but not related to ERCP. Eight articles were written in a language other than English. Forty-eight articles were identified as case reports, letters, reviews, meta-analyses, and so on. One hundred twenty-four articles were judged not suitable for pooled analysis based on their abstracts. After vetting was complete, 69 articles27-95 were reviewed.

Success and complication rates since 2014 for precut papillotomy, precut fistulotomy, transpancreatic sphincterotomy, and other techniques are shown in Tables 2-5, respectively. (Other techniques include precut sphincterotomies using combined techniques or without conventional devices.) The success rates of precut papillotomy, precut fistulotomy, transpancreatic sphincterotomy, and other techniques were 74.3% (2776/3736; range, 42.2–97%), 85.9% (1775/2067; range, 68.6–100%), 84.9% (1625/1914; range, 56.1–100%), and 91% (787/865; range, 75–100%), respectively. Complication rates of precut papillotomy, precut fistulotomy, and transpancreatic sphincterotomy were 12.3% (459/3736; range, 0–33.3%), 6.8% (140/2067; range, 0–15.8%), 10.1% (193/1914; range, 0–39.5%), and 8% (69/865; range, 0–38.2%), respectively. The overall success and complication rates were similar among three techniques in multiple trials (Tables 2-5). However, those trials involved one, or at most two, expert endoscopists in a single-center setting. Those trials also involved selection bias regarding the operator's preferred technique of precut sphincterotomy.

| Author/Ref/Year | Study design | No. institutions | No. endoscopists | Indication | Time limit (min) | Attempts | MPD cannulation | Timing | No. patients | No. successes | No. with PEP | No. with bleeding | No. with cholangitis | No. with retroperitoneal perforation | No. with sepsis | No. surgeries | No. deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katsinelos et al.272004 | Retrospective | Single | − | − | − | − | − | − | 68 | 44 | 3 | 5 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Catalano et al.282004 | RCT | Single | − | − | − | − | − | 7 | 34 | 26 | 4 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Abu-Hamda et al.292005 | Retrospective | Single | 3 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 95 | 88 | 9 | 5 | − | 2 | − | 1 | 0 |

| Kaffes et al.302005 | Prospective | Single | 3 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | 5 | Early | 70 | 58 | 1 | 6 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Ahmad et al.312005 | Retrospective | Single | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | 79 | 67 | 3 | 5 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Parlak et al.322007 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | − | − | A few | − | − | 65 | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lee et al.332007 | Retrospective | Single | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 195 | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Palm et al.342007 | Retrospective | Single | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 121 | 94 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | − | − | − |

| Horiuchi et al.352007 | Retrospective | Single | 2 | Failed cannulation | 15 | − | 2 | − | 30 | 27 | 1 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Kapetanos et al.362007 | Retrospective | Single | 2 | − | − | − | − | − | 15 | 8 | 0 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Fukatsu et al.372008 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | − | 80 | 70 | 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Akaraviputh et al.382008 | Retrospective | Single | − | − | − | − | − | − | 161 | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Siddiqui & Niaz392008 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | 59 | 56 | 2 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Misra & Dwivedi402008 | Retrospective | Single | 2 | − | − | − | − | − | 169 | 159 | 8 | 5 | − | 1 | − | 1 | 0 |

| Fukatsu et al.412009 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | − | 104 | 93 | 14 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Halttunen et al.422009 | Retrospective | Single | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 157 | 112 | 8 | 5 | − | − | 1 | − | 1 |

| Cennamo et al.432009 | RCT | Single | 2 | Failed cannulation | 5 | − | 3 | Early | 36 | 33 | 1 | 1 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| Figueiredo et al.442010 | Prospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10–15 | − | 5 | − | 43 | 34 | 2 | 3 | − | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bailey et al.452010 | Retrospective | Single | 2 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | − | − | 94 | 80 | 14 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Wang et al.462010 | Retrospective | Multicenter | − | − | − | Multiple | − | − | 76 | 69 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | − | − | − |

| Ang et al.472010 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 5 | − | 3 | Early | 55 | 49 | 1 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Chan et al.482012 | Retrospective | Single | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 66 | 50 | 3 | 4 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Coelho-Prabhu et al.492012 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | 10 | − | − | 78 | 75 | 8 | 5 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Katsinelos et al.502012 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 129 | 108 | 27 | 5 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| Kubota et al.512013 | Retrospective | Single | 3 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | − | 134 | 117 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 2 | − | − | − |

| Cha et al.522013 | RCT | Single | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 151 | 136 | 20 | 3 | − | 2 | − | − | − |

| Swan et al.532013 | RCT | Single | 4 | Failed cannulation | 5 | 5 | 2 | Early | 39 | 34 | 8 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Zhu et al.542013 | Retrospective | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | 5 | − | 56 | 51 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | − | − | − |

| Espinel-Díez et al.552013 | Retrospective | NA | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | − | 74 | 61 | 1 | 2 | − | 2 | − | − | − |

| de-la-Morena-Madrigal562013 | Retrospective | Multicenter | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | − | − | 69 | 60 | 2 | 7 | − | 2 | − | − | − |

| Pavlides et al.572014 | Retrospective | Single | 6 | − | − | − | − | − | 187 | 79 | 24 | 5 | − | 2 | 1 | − | − |

| Navaneethan et al.582015 | Retrospective | Single | 8 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 706 | 614 | 58 | 49 | − | 6 | − | − | − |

| Miao et al.592015 | Retrospective | Single | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 33 | 32 | 4 | 2 | 2 | − | − | − | − |

| Fiocca et al.602015 | Retrospective | Single | 4 | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | − | 138 | 132 | 10 | 4 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Baysal et al.612015 | RCT | Single | 1 | Failed cannulation | 15 | 10 | − | − | 70 | 60 | 3 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Total (%) | 3736 | 2776 | 281 | 140 | 6 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| 74.3 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

- a MPD, main pancreatic duct; ND, not described; PEP, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; −, not available.

| Author/Ref/Year | Study design | No. institutions | No. endoscopists | Indication | Time limit (min) | Attempts | MPD cannulation | Timing | No. patients | No. successes | No. with PEP | No. with bleeding | No. with cholangitis | No. with retroperitoneal perforation | No. with sepsis | No. surgeries | No. deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu-Hamda et al.292005 | Retrospective | 1 | 3 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 44 | 42 | 0 | 3 | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| Parlak et al.322007 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | − | − | A few | − | − | 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lee et al.332007 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Horiuchi et al.352007 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 15 | − | 2 | − | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Khatibian et al.622008 | RCT | 1 | 2 | From the beginning | 0 | − | − | Early | 106 | 88 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | − | − | − |

| Akaraviputh et al.382008 | Retrospective | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 32 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | – |

| Manes et al.632009 | RCT | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | 5 | − | 77 | 63 | 2 | 5 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Madácsy et al.642009 | Prospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | − | − | 22 | 20 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Donnellan et al.652010 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 10–15 | − | − | − | 352 | 317 | 1 | 15 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| Kevans et al.662010 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 187 | 151 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Yoon et al.672010 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | − | 60 | 54 | 5 | 2 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Lee et al.682011 | Retrospective | 2 | 2 | − | 10 | − | 5 | − | 159 | 139 | 9 | 6 | − | 1 | − | – | − |

| Testoni et al.692011 | Retrospective | 1 | 4 | Decided by operator | − | − | − | − | 170 | 161 | 11 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lim et al.702012 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | Early | 72 | 68 | 3 | 5 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| Ayoubi et al.712012 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 88 | 85 | 1 | 3 | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| Park et al.722012 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | 3 | − | 154 | 138 | 15 | 3 | − | 1 | − | − | 0 |

| Katsinelos et al.502012 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 78 | 72 | 2 | 4 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Lee et al.732014 | Prospective | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 71 | 67 | 7 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Lopes et al.742014 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 12–15 | − | − | − | 204 | 166 | 13 | 2 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| Lopes et al.752014 | Prospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 5 | 5 | Early | 48 | 41 | 2 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Lopes et al.752014 | Prospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 15 | 10 | − | 35 | 24 | 3 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | − | |

| Kim et al.762015 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | 5 | − | Early | 67 | 53 | 3 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | 0 | |

| Lee et al.772015 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 5 | 3 | Early | 19 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | − | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 2067 | 1775 | 80 | 52 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||

| (%) | 85.9 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

- a MPD, main pancreatic duct; PEP, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; −, not available.

| Author | Study design | No. institutions | No. endoscopists | Indication | Time limit (min) | Attempts | MPD cannulation | No. patients | No. successes | No. with PEP | No. with bleeding | No. with cholangitis | No. with retroperitoneal perforation | No. with sepsis | No. surgeries | No. deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akashi et al.782004 | Case series | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | 172 | 163 | 10 | 2 | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| Catalano et al.282004 | RCT | 1 | NA | − | − | − | − | 29 | 29 | 1 | 0 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Kahaleh et al.792004 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | − | 3 | 116 | 99 | 9 | 3 | − | 2 | − | − | − |

| Parlak et al.322007 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | − | − | A few | − | 147 | 136 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Horiuchi et al.352007 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 15 | − | 2 | 48 | 46 | 1 | 0 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Kapetanos et al.362007 | Retrospective | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | 40 | 29 | 2 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Weber et al.802008 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | 30 | − | 3 | 108 | 103 | 6 | 6 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Halttunen et al.422009 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | 262 | 147 | 23 | 4 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Wang et al.462010 | Retrospective | Multicenter | − | Failed cannulation | − | Multiple | − | 140 | 116 | 16 | 2 | 2 | − | − | − | − |

| Dhir et al.812012 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | 144 | 130 | 4 | 6 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Chan et al.482012 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | 53 | 36 | 2 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Katsinelos et al.502012 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | 67 | 67 | 15 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Yoo et al.822013 | Prospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | 10 | − | 37 | 34 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | − | – | − |

| Espinel-Díez et al.552013 | Retrospective | − | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | 125 | 117 | 4 | 6 | − | 1 | − | − | − |

| de-la-Morena-Madrigal562013 | Retrospective | Multicenter | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | − | 50 | 35 | 2 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Lin832014 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | 20 | 18 | 3 | 2 | − | 0 | − | 1 | − |

| Zang et al.842014 | Prospective | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | 73 | 70 | 5 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Huang et al.852015 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | 1 | − | 142 | 129 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | − | − | 1 |

| Kim et al.862015 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | − | 10 | − | 38 | 28 | 14 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Lee et al.772015 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 5 | 3 | 67 | 58 | − | 5 | 2 | 0 | − | − | − | |

| Miao et al.592015 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | 36 | 35 | 2 | − | 1 | − | − | − | − | |

| Total | 1914 | 1625 | 127 | 46 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| % | 84.9 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

- a MPD, main pancreatic duct; PEP, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; −, not available.

| Author/Ref/Year | Study design | No. institutions | No. endoscopists | Indication | Time limit (min) | Attempts | MPD cannulation | Timing | No. patients | No. successes | No. with PEP | No. with bleeding | No. with cholangitis | No. with retroperitoneal perforation | No. with sepsis | No. surgeries | No. deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uchida et al.872005 | Prospective | 1 | – | Failed cannulation | 20 | − | − | − | 26 | 24 | 0 | 1 | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| Park et al.882005 | Prospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 25 | 23 | 5 | 1 | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| de Weerth et al.892006 | RCT | 1 | 4 | From the beginning | 0 | − | − | − | 145 | 145 | 3 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Parlak et al.322007 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | − | – | A few | − | − | 17 | 17 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Akaraviputh et al.382008 | Retrospective | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Misra & Dwivedi402008 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − | 22 | 22 | 1 | 0 | − | 0 | − | 0 | − |

| Thomas et al.902009 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | − | − | − | 16 | 12 | 0 | 1 | − | − | 2 | − | − |

| Chiu et al.912010 | Prospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | − | – | − | 13 | 13 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Park et al.922010 | Retrospective | 1 | 2 | Failed cannulation | 5 | − | − | − | 59 | 51 | 4 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Dhir et al.812012 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | − | 5 | − | − | 58 | 57 | 0 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Riphaus et al.932013 | Prospective | 1 | 1 | − | − | 7 | − | − | 249 | 219 | 10 | 10 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Yoo et al.822013 | Prospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | 10 | 10 | − | − | 34 | 27 | 13 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Liu et al.942013 | Retrospective | 1 | 1 | Failed cannulation | − | – | − | − | 18 | 18 | 1 | 0 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Jamry952013 | Retrospective | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | 10 | − | − | − | 59 | 57 | 2 | 8 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Espinel-Díez et al.552013 | Retrospective | − | 1 | Failed cannulation | – | 5 | − | − | 48 | 40 | 0 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | − |

| Baysal et al.612015 | RCT | 1 | − | Failed cannulation | 5 | 10 | − | − | 69 | 62 | 2 | 1 | − | 0 | − | − | 0 |

| Total | 865 | 787 | 41 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| (%) | 91 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

- a MPD, main pancreatic duct; PEP, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; −, not available.

Our search had some major limitations. Number of complications may have been underestimated because of differences in each definition. Moreover, only what was described in each article could be calculated or counted.

Which precut sphincterotomy technique should be selected?

We identified only two retrospective studies and one RCT that included a direct comparison between two or among three techniques. In a retrospective study of 133 consecutive patients undergoing precut sphincterotomy, Abu-Hamda et al.29 compared three techniques: pancreatic fistulotomy with occasional pancreatic stenting, precut papillotomy with blended current without pancreatic stenting, and precut papillotomy with pure cutting current and frequent pancreatic stenting. Success rates of SBDC during the initial ERCP for each technique were 95.5%, 95.7%, and 89.6%, respectively. PEP rates associated with each technique were 0%, 6%, and 3%, respectively. Abu-Hamda et al. determined that precut fistulotomy may reduce the risk of PEP compared with precut papillotomy. In a retrospective study of 274 patients undergoing precut sphincterotomy, Katsinelos et al.50 compared three techniques: precut fistulotomy, pancreatic papillotomy, and transpancreatic sphincterotomy. Success rates of SBDC at initial ERCP for each technique were 92.3%, 97.7%, and 100%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the initial success rates of SBDC among the three groups. PEP rates for each technique were 2.6%, 20.9%, and 22.4%, respectively (P = 0.001). This study indicated that precut fistulotomy yielded a significantly lower incidence of PEP compared with precut papillotomy or transpancreatic sphincterotomy. In a RCT of 153 patients with suspected choledocholithiasis, Mavrogiannis et al.96 compared precut fistulotomy and precut papillotomy. Their study showed no significant difference between the two techniques. However, precut fistulotomy had a significantly lower incidence of PEP compared with precut papillotomy (0% vs 7.6%, respectively) (P < 0.05).

In another study, precut fistulotomy was associated with fewer complications compared with precut papillotomy or transpancreatic sphincterotomy.23 Theoretically, precut fistulotomy above the orifice of the papilla (i.e. not touching the orifice of the pancreatic duct) can prevent damage to the pancreatic duct or avoid edematous change of Vater's ampulla compared with other techniques starting at the orifice of Vater's ampulla. However, important questions remain to be answered regarding the most suitable technique of precut sphincterotomy. Moreover, further RCT will be required to determine which techniques are the most effective and feasible based on the morphology of Vater's papilla.

When is the appropriate time for precut sphincterotomy?

Precut sphincterotomy is a valuable technique to achieve SBDC for failed cases using conventional techniques. However, some reports have shown an increased incidence of PEP in precut sphincterotomy cases. Whether adverse events associated with precut sphincterotomy are because of the procedure itself or the repeated and prolonged attempts of SBDC using a conventional technique is still controversial. Recently, a study showed that early, rather than delayed, precut sphincterotomy may reduce the risk of PEP.45 Recent meta-analyses reported that although there is no significant difference in overall SBDC rates, the indication of early precut sphincterotomy significantly improved primary SBDC rates compared with persistent standard cannulation in patients with difficult SBDC.97-99 For experienced endoscopists, the early use of precut sphincterotomy did not increase the risk of adverse events (especially PEP and perforation), and may actually reduce these risks.

Regarding the use of a pancreatic stent during precut sphincterotomy, Cha et al.52 compared immediate removal at the end of the procedure and late removal 7–10 days after the procedure. Their study showed that the incidence and severity of PEP was significantly lower after late removal compared with immediate removal. Therefore, a pancreatic stent should be placed for prophylaxis of PEP after precut sphincterotomy.

Details of the technique used for precut sphincterotomy with respect to the morphology of Vater's ampulla, its timing, and the expertise of the endoscopist, among other factors, are subject to confirmation by additional RCT.

Conclusion

Evolution of the endoscope, peripheral devices, and endoscopic techniques has permitted a high success rate for SBDC. To prevent PEP after SBDC, we should consider standardization of the SBDC technique, devices, and timing. Furthermore, to date, there is no optimal transpapillary cannulation technique to achieve perfect SBDC and prevent all instances of PEP.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Kawakami is a consultant and gives lectures for Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan; Piolax Medical Devices, Kanagawa, Japan; and Taewoong-Medical Co., Ltd, Seoul, South Korea. Dr Kawakami is a consultant for Zeon Medical Inc., Tokyo, Japan and M.I.Tech Co., Ltd, Seoul, South Korea. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.