How the Institutional Context Creates a Neoliberal Politics of Aid: An Italian Case Study

Part of this work was supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark through the project Commodifying Compassion (Richey, PI 6109-00158). The article has benefited from the research assistance of Adriano Pedrana, Anna Salvatorini and Alex Maxelon and from collaborations with Maha Rafi Atal. It has been improved through collegial seminars at the Department of Culture, Politics and Society, University of Torino, hosted by Egidio Dansero and Paola Minoia, and the Department of Economics and Management, University of Padova, hosted by Valentina de Marchi and Eleonora di Maria, and the input of three anonymous peer reviewers. Any remaining flaws are the author's.

ABSTRACT

Transnational ‘helping’ today relies upon partnerships with private companies as enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, creating Faustian bargains of neoliberalism. However, a knowledge gap remains over how state institutional structures produce these neoliberal solutions. This article explores the case of Italy, an under-researched development actor, to analyse the interactions between its development institutions and their politics to better understand the role of for-profit actors in transnational helping. As in other donor countries, there has been a weakening of public trust in the traditional aid sector of Italian non-profits, combined with recent decreases in national funding for assistance abroad. The article is based on review of state, NGO and private sector documents, including laws and policies, as well as participant observation and review of academic literature in Italian and English. Using an historical institutional approach, the author demonstrates how Italian helping has been characterized by a strategic co-mingling of public and private aid, development and humanitarian aid, and of helping abroad and within Italy. In a changing institutional context for Italian NGOs characterized by reduced public solidarity, negative discursive framing and the need to diversify fund-raising channels, Italian businesses are being sought out for partnerships between for-profit and non-profit actors.

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, Save the Children International celebrated its centennial anniversary with a research conference in London supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund.1 At this event, where scholars of the organization reflected together with practitioners on fundamental questions of politics, humanitarianism and children's rights, a curious co-branded logo with Bulgari, the Italian luxury brand, appeared on the screen in front of the podium. During this celebration, no one mentioned publicly the possible conflict of interest between a for-profit brand and one of the world's largest aid organizations. Yet, conversations over ‘neutrality’ and funding — acknowledged as ‘never neutral’ — outlined the necessary distance between helping organizations and the politics of the states that fund them.2 The donation of ‘a part of the proceeds’ from a € 790 pendant with the NGO's logo ‘honouring the 10th anniversary of Bulgari's philanthropic partnership with Save the Children’3 was somehow less political than money with state strings attached.

Transnational ‘helping’, taking form in development, humanitarianism, advocacy and foreign policy, has increasingly involved partnerships with private companies like Bulgari. These partnerships are even enshrined in the ‘common framework’ of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with their own explicit goal, SDG 17 (see Richey et al., 2021). Scholarship on these partnerships across social sciences and business has raised concerns about the possible ‘Faustian bargains’ of neoliberalism (Barnett, 2023). Yet, there remains a gap in our understanding of how state institutional structures create these neoliberal solutions of incorporating private for-profit and philanthropic actors into frameworks of development cooperation and international assistance. To fill this gap, this article looks through the keyhole of the silver, onyx and ruby pendant which aims to save children, to better view the Italian institutional framework for transnational ‘helping’ that produced it. There is a paradox in the case of this donor country, where the church is deeply embedded in political, economic and societal structures and so outspoken in support of carità, or helping those in need, but which is also a prime example of the commodification of compassion and making business profit from transnational helping. Understanding these relationships of power will contribute to a better understanding of our contemporary neoliberal politics of aid.

This article uses the term transnational ‘helping’4 as an umbrella term for understanding the practices of international aid. This is not to dispute that there are different mechanisms and norms that govern humanitarian responses to crisis versus the continuous duty of development assistance. Humanitarian aid and what would later be called development aid went their separate ways after World War II (see Barnett, 2013). But connections between them remained and have become tighter in the 21st century as strategic partnerships have included businesses in the service of profit and do-gooding (Barnett and Richey, forthcoming). Here, ‘helping’ signals the intentionality of the donor agent, not an evaluation on the efficacy of any of the actual practices from the points of view of the donors or their intended beneficiaries. Using an historical institutional approach, this article argues that the governance structure of Italian helping — with its confluence of church, state and market — has been characterized by a strategic co-mingling of public and private aid, development and humanitarian aid, and of helping abroad and within Italy. Conflation across these dimensions has been correlated with and co-constituted by: (1) weakening public trust in Italian non-profits; (2) insufficient national funding in relation to perceived need; (3) the need to diversify funding sources; (4) fundraising from private sources through social networks; and (5) partnerships between businesses and non-profits.

The guiding premise of neoliberalism is the primacy of the market, yet markets do not create themselves and must be embedded within societal institutions. Scholars inspired by Karl Polanyi attribute the successes of neoliberalism to its ability to reshape the societal institutions in which it is embedded, including the state, to prioritize markets. The example of a humanitarian pendant from a collaboration between the Italian branch of Save the Children5 and a successful luxury brand does not result from the usual funding or values of humanitarianism. Instead, it exemplifies significant changes in the societal institutions of transnational helping. Understanding how the details of engagement between the state, church and market in the Italian institutional context led to what may be deemed an absurd product6 will shed light on the neoliberal politics of development.

Italy is a useful case for exploring the banality of neoliberalism in aid because it is, in many ways, an unexceptional, traditional donor. It ranks as the eighth largest donor of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC),7 yet only gives 0.28 per cent of its gross national income in aid, which is less than half of the UN target of 0.7 per cent and significantly lower than the DAC average of 0.45 per cent. A growing share of Italy's bilateral aid (approximately 41 per cent) is currently being used for managing migration within the country, raising concerns that international development efforts are overestimated.8 As this article will discuss, Italy's history of international cooperation has been historically entwined with the Catholic Church, which might suggest that strongly competing values of solidarity would make the country less open to embracing neoliberal development. However, Italy also has an institutional history of linking transnational helping directly with the promotion of Italian businesses. Today, the interface for helping brings together government legislation, state bodies, for-profit organizations, non-profit organizations, the church and individuals. As in other donor countries, there has been a weakening of public trust in the traditional aid sector of Italian non-profits, combined with recently decreasing national funding for humanitarian helping abroad. These trends have led to a growing need for non-profits to pivot their fund-raising campaigns towards individuals, social networks (De Carli, 2019) and businesses.

Italy is under-researched as an actor in transnational helping, yet it was itself a recipient of foreign aid and has now become a donor engaged in multiple forms of institutionalized helping abroad and at home. It is a useful case for examining the interplay between the church, the state and the market and changing values towards a neoliberal politics of development. While it is typically considered the home of church-based charity, Italy also has a long history of political consumerism (Graziano and Forno, 2012), where selling products for local causes is the norm. Analysing official documents including state laws and policies and NGO reports, reviewing the academic literature on international cooperation in Italian and English, and informed by participant observation, selected key informant interviews and conversations, this article argues that the institutional context of Italian aid is constituted by a moving constellation of relationships between the state, the church and NGOs. In this changing institutional context for Italian NGOs, characterized by decreasing public solidarity, negative discursive framing and the need to diversify fund-raising channels, Italian businesses are being sought out for partnerships between profit and non-profit actors (Alonso-Martínez et al., 2020). These businesses are bringing more than funding; they are bringing values that characterize the neoliberal politics of aid. It has never been the case — in Italy or elsewhere — that church, state and market exist as closed value systems with ‘pure’ and fully competing interests. Even though they constitute a deeply enmeshed set of social values and practices enacted by people embedded within cultures, disentangling the differences over time between shifts within the Italian institutional aid context is important for understanding its politics.

The article proceeds as follows: the next section presents literature explaining the use of the term ‘neoliberal’, the trends brought by new actors and alliances in global development, humanitarianism and philanthropy, and what we know thus far about these in the Italian case. The following two sections then explain the formal structures shaping humanitarianism and international development in contemporary Italy and their history, and examine the current framework for development and the organization of the cooperation system that links the state, non-profit and for-profit actors in helping. Next, the article examines the public funding trends for development helping, and then looks at the private funding available. The penultimate section discusses the changes in perceptions of non-state helping and doing good and how these promote neoliberal development. Finally, the article concludes with reflections on what this institutional context suggests for the mix of public and private values, institutions and helping in Italy within an increasingly illiberal global order.

NEOLIBERALISM AND ‘PRIVATIZATION CREEP’ OF NEW ACTORS AND ALLIANCES IN GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT

The neoliberalization of transnational helping is characterized by the significant shift from collaborations between accountable states and international organizations to those among genial elites (Budabin and Richey, 2021). Finalizing this article in the geopolitical context of drastic cuts in humanitarian and aid budgets across major DAC donors also demonstrates what happens when non-genial elites are making funding decisions. This trajectory can be better understood as an extension of, not a deviation from, neoliberal development. Although cognizant of the decades-long debate over the utility of the concept ‘neoliberalism’, it remains useful for characterizing ‘the deep transformations undertaken by national economies toward a greater role for markets, less regulation, and the erosion of state-enforced social solidarity’ (Ban, 2016: 8). The phenomenon of neoliberal ‘triumphalism’ is characterized by ‘[t]he specific market-triumphalist manner in which capitalist globalization has been shaped and reproduced’ (Kingfisher and Maskovsky, 2008: 116), ‘free-market fetishism’ and believing the market to be ‘the most efficient and moral institution for the organization of human affairs’ (Springer et al., 2016: 3), along with ‘the deployment of “enterprise models” that would allow the state itself to be “run like a business”’ (Ferguson, 2010: 170). State and non-state actors justify policies and actions that favour market-based solutions, producing a political rationality that can be studied for its suffusion into other areas of human life, in particular effecting a ‘discursive production of everyone as human capital’ (Brown, 2016: 33).

After the global financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, there has been a revived scholarly interest in neoliberalism's resilience to empirical challenges to its triumphalism (e.g. Schuurman, 2009). Yet, even at its best, post-neoliberalism has not been able to make a definitive break from neoliberalism's governance strategies (Córdoba et al., 2014). At its worst, neoliberalism has stripped the capacity of states, disinvested in the education of citizens, and shifted the values of transnational cooperation from public to private.

Today we see new configurations, new ‘eras’ of helping predicated upon the previous rise of NGOs, and their accompanying business partnerships. More participation by business has brought different sources of funding but also different values. Scholars identify differing normative and institutional structures in humanitarianism and development that, while demonstrating consistent elements over the long durée, nonetheless shape into overall eras or epochs of practice. Important changes have taken place that can be traced roughly from the beginning of the 21st century to the present. Barnett and Karunakara (forthcoming) refer to 21st century humanitarianism as the Age of Post-liberal Humanitarianism, in contrast to the previous period, the Age of Liberal Humanitarianism (see also Barnett, 2013). Brooks (2017) charts a shift from the ‘international development era’ to the post-development era. Kumar and Brooks (2021) characterize the financialization and marketi-zation of philanthropic funding for development organizations as the philanthrocapitalist epoch, which followed the partnership epoch (1970s–2000) and the scientific development epoch (1940s–1970s). In this journal, Horner and Hulme (2019) identify a transition from the post-World War II period to the early 2000s as one from ‘international development’ to ‘global development’ (see also Horner, 2019). While differences exist across modalities of international helping, whether we are now in the time of post-(neo)liberal humanitarianism, post-development, philanthrocapitalist or global development, there are common trends across transnational helping.

One trend identified across scholarship on humanitarianism, development and global philanthropy is the increasing role and influence of NGOs which partner with non-traditional actors, including business (see Brainard and Chollet, 2009; Fejerskov et al., 2017). The NGOs’ impulse to partner with businesses emerges partly from the expectation that businesses will bring corporate culture and management to the humanitarian field (Carbonnier and Lightfoot, 2015: 179) and the trends of shaping states to support markets in transnational helping. For example, a career-long leader of an international humanitarian organization explained that ‘NGOs could actually help resource-poor governments in fragile and conflict-affected states to get a better deal with corporations, and maybe a more lasting commitment from corporations, because, you know, the NGOs have a bit more clout, frankly, than the government’.9 In the 1980s, Western governments encouraged NGOs to administer social services at home and act as vehicles for government aid abroad (Lynch, 2013: 56). But the use of NGOs to deliver goods previously guaranteed by the state has not led to the gains expected, despite the use of more efficient, market-based mechanisms, underscoring the fact that the state has not ‘retreated’ from the equation in terms of humanitarian delivery and development aid, but rather has adopted a new role as a donor and monitoring agency (ibid.: 57). In turn, NGOs have adapted their approaches to suit funding and reporting practices in this new configuration. This reorientation has led to an adoption of and reliance on terms such as ‘capacity-building’, ‘partnership’, ‘innovation’ and ‘entrepreneurial endeavours’ for humanitarian goals (ibid.: 58–61).

Infusions of cash from the for-profit or philanthropic arms of business are seen in a positive light for many. As Dees (2008: 126) writes, philanthropists ‘can take the risk, subsidize higher cost structures, and be more patient than profit-seeking investors and the entrepreneurs’. Yet the meanings of these shifting global forces, as exemplified by the SDGs, have only recently been analysed. Mawdsley's (2018) critical commentary on the financialization of development (see also Christophers, 2015) argues that the SDGs’ call for private financing produces its own normalization of private capital relations. As Wilson (2017: 186) writes, ‘philanthrocapitalism suggests that saving the world and good business are one and the same’. The increasing profitability of helping can be situated within a larger realm of marketization of development and humanitarianism (Andreu, 2018; Glaab and Partzsch, 2018; Richey, 2018).

The replacement of the state with businesses in development and humanitarian contexts has, moreover, met considerable pushback. Brooks (2017) explains how the SDGs involve a loss of sovereignty from Southern states to ‘benevolent’ donors. The goals are also the epitome of an instrumentalized and utilitarian approach to humanitarian aid that is no longer based on principles but on effectiveness (Yanguas, 2018). The SDGs are constituted by corporate humanitarian partnerships; understanding how privatization has entered contexts of helping is therefore increasingly relevant.

Still, it remains unclear what the appropriate role for business is in navigating humanitarian contexts (Miklian and Schouten, 2014). As private contractors or sources of philanthropic funding, businesses participate in humanitarian work in ways that ‘can prove highly cost effective in managing reputational risks and bolstering public image’ (Carbonnier and Lightfoot, 2015: 172). Instrumental rationales of businesses include access to new markets, the reduction of business risks and the ability to build relationships with other humanitarian actors, including intergovernmental organizations, governments and local communities (Hotho and Girschik, 2019: 209–10). In partnership with relief agencies, companies ‘influence the political economy of humanitarian crises by affecting the distribution of wealth, income, power and agency in typically fragile institutional environments’ (Carbonnier and Lightfoot, 2015: 174). The case of the Italian institutional environment for cooperation illustrates neoliberal shifts toward helping as privatization creeps into Italian institutions designed to help.

While there has been considerable interest in neoliberal development from the usual suspects of the United States and the United Kingdom, Italian development or humanitarian cooperation is not the subject of much academic interest for scholars of aid overall or for Italian scholars of state–society relations. Nonetheless, there are notable exceptions. The quintessential text for understanding the entanglement of the state and market logic in Italy for providing help is the book The Moral Neoliberal: Welfare and Citizenship in Italy (Muehlebach, 2012). This book charts how neoliberal ideology, with its emphasis on individual responsibility and market-oriented solutions, has shaped the welfare state and transformed the understanding of citizenship in contemporary Italy. Aid, whether it be directed outside or inside the country, has a fundamental role in the struggle to create a ‘civil religion’ in which ‘the state's appropriation of the church's sacred right to administer and distribute carità was one of the primary grounds upon which the sacralization of politics in Italy took hold’ (ibid.: 73). In describing ‘the ethical state’, Muehlebach charts the development of Italy's liberal welfare state and ‘the slow building of social citizenship rights as a way for the state to depoliticize revolutionary struggles’ (Wolin, 1989: 154–55) by causing ‘revolutions to lapse into bureaucracy’ (Feher, 2009: 34), both quoted by Muehlebach (2012: 81).

Thus, while some scholarship has explored how Italian citizens negotiate their rights, obligations and entitlements within a system that increasingly prioritizes individual responsibility over collective welfare (Giudici, 2021; Martin and Tazzioli, 2023; Muehlebach, 2012), this article will look at the bureaucracy itself for insight into the neoliberalization of Italian helping. Italian capitalist helping is embedded within a stronger history of the dominance of the Catholic Church in its transnational politics. Giudici (2021: 45, note 3) argues that the Italian state has, since unification, been struggling not to alienate the Catholic Church, ‘because of its wealth and charitable apparatus’. Transnational helping has been described as the ‘bedrock of the West's late capitalist … expression of secular religiosity; and its mobilization of faith could make it a viable force for liberal renewal’ (Fiori et al., 2021: 17). Yet, as this article will argue, the Italian case shows something quite different. Instead of a struggle between the state, church and market, an historical institutional analysis shows how the Italian state was organized in ways that co-opted the church and Third Sector organizations, placing them on the same institutional footing as private businesses when organizing development and humanitarian aid.

FORMAL INSTITUTIONS OF ITALIAN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION

The regulation of Italian development cooperation is primarily governed by a law passed in 2014 to align Italian practices with international and European Union (EU) standards. The law defines development cooperation as ‘international cooperation for sustainable development, human rights, and peace’ and an ‘integral and qualifying part of Italy's foreign policy’ (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2014: 1).10 It sets various policy objectives such as the eradication of poverty, reduction of inequality, promotion of gender equality, democracy, support for peace-building and reconciliation processes and domestic and international development initiatives (ibid.). The law also encourages shared migration policies, which involve migrant communities in Italy, and education, awareness and civic participation in international cooperation and sustainable development measures, both in Italy and abroad (Ministero degli Affari Esteri, 2019). This legal framework encompassing both traditional development aid and aid to migrants in Italy from developing countries enables contemporary anti-immigrant politics to spill over into Italy's transnational helping.

Historical Background of Italian International Cooperation

After World War II, Italy was a net recipient of foreign aid, mainly through the Marshall Plan for post-war reconstruction (Carbone, 2008: 60) and for the economic development of the rural southern regions (Lorenzini, 2017: 462). Italy's outbound foreign assistance was largely limited to, and primarily associated with, its administration of Somaliland as a UN trust territory from 1950 to 1960. Additionally, funds were allocated to support Italian settlers in Libya (Van der Veen, 2011: 67), and for reparations to be paid to Ethiopia and Yugoslavia (Carbone, 2008: 60). Eager to retain political influence in international fora, Italy became a founding member of the International Development Association and the Development Assistance Group (Calandri, 2019: 365), but maintained an official ‘non-policy of cooperation’ for its own spending (Isernia, 1995: 76).

Lobbying by religious groups, international pressure and interest in promoting sales by domestic companies in developing markets all influenced Italy's move towards greater development cooperation. These factors led to the passing of a law in 1966 which allowed Italians to volunteer in developing countries as a substitute for compulsory military service (Calandri, 2019: 368). The law facilitated a new focus on neighbouring South Mediterranean and Latin American countries with a large Italian migrant population (Carbone, 2008: 60). Italy's first development policy was adopted in 1971 with the Law on Technical Cooperation with Developing Countries which provided for technical assistance and volunteer workers (Carbone, 2008; Gasbarri, 1982: 216). However, direct financial aid remained separate from technical cooperation until the creation of the Interministerial Committee for Foreign Economic Policy in 1977. During this period, there was increasing interest in multilateral cooperation, which absorbed 80 per cent of all aid (Isernia, 1995: 89).

The 1971 Law on Technical Cooperation represented a political compromise. In the context of international détente during the Cold War (Calandri, 2019: 370), the law was a compromise between the Christian Democratic Party and the Italian Communist Party. At the same time, the Institute for the Third World, which later became the Institute for Relations between Italy and the Countries of Africa, Latin America, and the Middle and Far East, or IPALMO (ibid.: 370–72) was founded. IPALMO had representatives from the three main political parties and included the Communist Party, giving it political clout. IPALMO allowed the Italian Communist Party to operate as a quasi-state delegation and a member of the Communist international movement, and also as a parallel Italian political leadership with connections to large state-owned industrial conglomerates (ibid.: 373). However, the bureaucratic struggles between conflicting and understaffed ministries slowed the new organizational infrastructure (ibid.: 370–72; Isernia, 1995: 93–98).

While Italy wanted the standing of being a multilateral actor, this came at a cost. There was decreasing interest from multilateral agencies in financing specific projects overall, and a limited number of projects in which Italy could participate. Thus, multilateralism limited Italy's ability to use aid to finance projects for Italian companies operating in developing countries (Gasbarri, 1982: 220). In response, Italy shifted focus from multilateral to bilateral aid, with bilateral aid increasing from 7 per cent to 43 per cent between 1979 and 1982 (ibid.). Aid also became a topic of greater societal interest. During the 1980s, Italy's Radical Party launched a public campaign against malnutrition and starvation with an urgent call to action for the general public, coupled with international pressure from the newly founded European Parliament (Isernia, 1995: 100–03). The Radical Party campaign made an ‘ambiguously clear’ (ibid.: 102) link between problem and solution, which translated into support for draft legislation in 1982 to set up a fund of Italian lire 3.5 billion (€ 6.2 billion) intended to feed at least three million people (Camera dei Deputati, 2020). Voted into law in March 1985, by February 1987, the Italian Aid Fund had managed to spend all its resources and became the subject of several mismanagement and corruption cases (Carbone, 2008: 61).

Shortly before the Italian Aid Fund expired, the parliament approved ‘new legislation on the cooperation between Italy and the developing countries’, which inaugurated the ‘institutionalization stage’, a third phase in Italian development history (Isernia, 1995: 119). This reform explicitly included cooperation for Italy's foreign policy and widened its scope to humanitarian, social and political targets. It also provided a response framework for catastrophes and emphasized integration within the policies of the recipient country (ibid.). The new legislation instituted a consultative committee with NGOs (Normattiva, 2020a: 8). This reflected the growing popularization of transnational helping, notably mixing domestic social welfare with development and humanitarian aid.

Over the years, this policy apparatus proved unwieldy, and it was ultimately dismantled. Foreign aid was used as a tool for contingent political and economic needs, sprinkling interventions across a vast number of countries and sectors. At the same time, the division of competencies between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in charge of bilateral initiatives and contributions to the EU budget) and the Ministry of Economics and Finance (handling contributions to the European Development Fund and to international banking institutions) undermined efficiency and coordination (Carbone and Quartapelle, 2016: 50–51). In 1992, the Mani Pulite (‘Clean Hands’) judicial investigation uncovered widespread, deep-rooted corruption across the Italian political establishment, including the Official Development Assistance (ODA) sector, which significantly undermined its credibility (Pedini, 1994: 376; Rhi-Sausi and Zupi, 2005: 336).

Since the late 1990s, maintaining Italy's status in the European Monetary Union, and subsequently in the Eurozone, has necessitated heavy cuts in state expenditure. Meanwhile, new international rules have limited the ability of donor countries to tie their aid — as Italy and others had previously done — to projects that promoted their own industry over that of other donor countries (Rhi-Sausi and Zupi, 2005: 337; Van der Veen, 2011: 19). Together, these factors contributed to a declining interest in foreign aid policy across the Italian political spectrum. Between 2001 and 2006, for example, no vice-minister for development was appointed, and instead, development functions were shared among four other under-secretaries (Carbone, 2008: 63–64). There were several unsuccessful attempts to reform the legal framework of development, with a decade of struggle over the independence of the new aid agency related to diplomatic and foreign policy objectives and the increasing interest in migration. Finally, in August 2014, Italy adopted its present development cooperation policy embodied in Law 125/2014; countries receiving aid today are those with a historical association with Italy. Much of what ‘counts’ as aid is either support for Italian businesses in DAC recipient countries or domestic resources for asylum seekers. In sum, as Italian transnational helping began to deliver fewer political spoils domestically, its help for ‘victims’ of human trafficking or persecution seeking asylum within Italy became the mechanism for manifesting ‘care’, or what Giudici (2021: 28) terms ‘subaltern inclusion’. But before we follow the money, it is important to understand the current institutional framework that is responsible for transnational helping.

THE CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK: THE COOPERATION SYSTEM

The State

The 2014 law defines the system for coordination between the state and non-state bodies constituting Italy's cooperation system. The development activities of the Italian government are currently overseen by five overlapping bodies.11 First, cooperation for development is part of Italy's foreign policy and, as such, falls under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, or MAECI) (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2014: 3), with a vice-minister responsible for cooperation (ibid.: 11). MAECI shares responsibility with the Interministerial Committee for Development Cooperation which includes the prime minister and representatives of nearly all ministries and local authorities. MAECI prepares three-year policy-planning documents (Camera dei Deputati, 2018) as well as an annual report. These documents must be approved by the Council of Ministers and so are subject to parliamentary and thus political scrutiny.

Second, the implementation of cooperation initiatives, as set out in the three-year plans, is the remit of the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (Agenzia Italiana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, or AICS), headquartered in Rome and Florence, with 21 offices abroad to allow for ‘monitoring, implementation, and on-site analysis of the development needs of partner countries’ (AICS, 2019a). Established as a public body with a public interest (AICS, 2018a: 3), it is responsible for the preliminary investigation, setup, financing, management and control of cooperation activities. AICS operates mainly through NGO partnerships, but it can also provide technical support to other bodies of the public administration that work in development cooperation, implement programmes from the EU or other international bodies and promote cooperation with private actors (AICS, 2018a: 4). Despite being formally autonomous in its administration, regulation and budget, AICS still falls under the purview of MAECI and is subject to its politics. A third body, the MAECI-AICS Joint Committee for Development Cooperation, approves initiatives worth more than € 2 million and defines annual programmes (Ministero degli Affari Esteri, 2019). Fourth, coordination between public and private actors is the responsibility of the National Council for Development Cooperation (Consiglio Nazionale del Terzo Settore — CNTS), an advisory body with representatives from public, private and non-profit sectors. The fifth and final body, the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP), is the financial institution that acts as development bank (Camera dei Deputati, 2018). The CDP is a joint stock company in which the majority stakeholder is the Ministry of Economics and Finance. Its aim is to ‘foster the development of the country [Italy] using national savings responsibly in order to support growth and boost employment, leveraging innovation, business competitiveness, infrastructure and local development’ (CDP, 2019). While the national government system for international development is no more unwieldy than other parts of the Italian state, it is interesting in that it facilitates the formal involvement of many other actors, including for-profit businesses.

The 2014 law specifies four categories of significant non-state bodies engaged in transnational helping. In the first category of state administrations, universities and public bodies, universities are called upon to promote capacity building using technical expertise. This might include institutional partnerships with universities in developing countries, joint training and study programmes, and research and teaching on sustainable development. Such efforts aim to transform academia into a development agent by ‘training the ruling class of the future’ (AICS, 2018b: 8–9). The second category, local authorities, is one of the original elements of the Italian cooperation system (AICS, 2015: 18) and dates back to a 1987 law permitting local and regional authorities to conduct their own international development programmes with oversight by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministero degli Affari Esteri, 2004). Local authorities can use up to 0.8 per cent of city budgets for international cooperation initiatives (Rhi-Sausi and Zupi, 2005: 341). Italy's decentralized cooperation system has gained international momentum and recognition at the EU level (Stocchiero et al., 2001: 3). While the EU also recognizes local authorities alongside civil society organizations, the Italian legal framework gives local authorities several unique roles. These include the ability to cultivate direct political and technical relationships with local authorities in recipient countries and the capacity to include local social capital — cultural, scientific or other types — in their programmes. Moreover, local authorities’ development efforts carry political meaning. When a city council commits to a project of international aid, every citizen becomes involved in international helping (ibid.: 3–5).

Local authorities play a particularly significant role in relation to migration, an increasingly important area in international aid because of the remittances sent by migrants to their originating countries and the philanthropic initiatives of migrant associations, both of which affect investments (Zupi, 2015: 38–46). Local authorities implement initiatives supporting global citizenship, work with associations of migrant communities, and make direct interventions in target countries (AICS, 2018b: 7–8). These initiatives can be financed through local authorities’ own funds, coordinated with public and private bodies, or co-financed with resources from AICS. For example, in 2020, the National Association of Municipalities launched the ‘Cities without Borders’ campaign in direct cooperation with fellow municipalities in receiving countries. This unique arrangement reflects both the state's ideals for global citizenship education as well as its need to link its citizens’ desires for transnational helping to the Italian government's development objectives.

Non-Profit Organizations in Italian Transnational Helping

As the previous discussion of the institutional framework for cooperation has shown, there are many different points of formal coordination; in fact, a kaleidoscope of interests and actors have become involved in helping, both non-profit and for-profit. The Italian non-profit sector has grown dramatically (over half of the country's 343,000 NGOs were founded after 2005). While the sector employs over 800,000 people, the majority of whom are in a few of the largest NGOs, most non-profit organizations rely exclusively on unpaid volunteers and are primarily domestic (ISTAT, 2018). The 1987 reform established a process for recognizing NGOs through an ad hoc commission. The requirements to become a recognized development NGO included: (1) a non-profit status; (2) structure and qualified personnel; (3) at least three years’ experience; and (4) ‘having as an institutional objective that of carrying out cooperation for development activities, in support of populations of the Third World’ (Normattiva, 2020b: 28). It is important to note that this support is for populations of, not necessarily, in the Third World which opens transnational helping to include asylum seekers within Italy. Article 32 of the 2014 law indicates that already recognized NGOs that also comply with the status of ‘socially oriented non-profit organizations’ (‘organizzazione non lucrativa di utilità sociale’) are automatically added to the national registry of non-profits (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2014: 32; Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2017: 89), and can also be included in the AICS list to receive development funding as described below.

In 2017, the sector underwent a significant reform, with new legislation that defines 26 fields of action ‘of public interest’ for non-profit organizations (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2017: 5). The reform creates a single national registry of non-profits, and only non-profits in this registry can receive public funding or private funding through public campaigns (Camera dei Deputati, 2019). Separately, the AICS has an ongoing list of NGOs entitled to apply for grants, tenders and collaboration. These accredited organizations (approximately 215) must follow the 2014 development policy law and adhere to commonly adopted social responsibility standards, environmental regulations and a code of ethics. Critically, NGOs on this list cannot rely solely on public funding and must document that at least 5 per cent of overall income is from private sources (AICS, 2018c: 6, emphasis added). This is important as it requires a universal if minimal level of privatization of all non-profit organizations.

For-Profit Bodies

The involvement of Italian companies in development cooperation policies dates to the 1950s and 1960s, when they represented an important tool for implementing government infrastructure projects in developing countries, while supporting domestic industries (Zupi, 2015: 13–14). Since the law of 2014, for-profit companies have been considered ‘fundamental for the new [model of] cooperation’ (AICS, 2019b). Internationalization of private Italian companies is a tool that can be leveraged for development in targeted countries and populations (Camera dei Deputati, 2018). Promoting synergies between the public and private sectors, as well as between the non-profit and for-profit sectors, can create consistency in cooperation activities across sectors and leverage more private financing. AICS (2019d) echoes the language of ‘committing billions and investing trillions’ (Kituyi, 2015), previously a buzzword of the 2015 UN Conference on Trade and Development in Addis Ababa. The AICS similarly reproduces the UN 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015), which underlines the role of private business by defining international trade as the ‘engine for an inclusive economic growth’ and calls for private bodies to ‘apply their creativity and innovation to solving sustainable development challenges’ (AICS, 2019c).

By partnering with the private sector, AICS aims to build business models that respect SDG 12 to ‘ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns’ and to consider the social and environmental impacts on populations in receiving countries (AICS, 2019c). The European Commission makes a distinction between ‘private sector development’ in developing countries and ‘the engagement of both local and European businesses for tangible and positive development outcomes on the ground’ (EC, 2014: 16). AICS also refers to the ‘experience of Italian SMEs [small and medium sized enterprises] aggregated in networks and organized with shared services to foster economies of scale [as] a replicable model to use in partner countries to contribute to the growth of their private sector’ (AICS, 2019d: 2). Companies can receive resources through a revolving fund to finance joint venture projects in partner countries (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2014: 27). This funding can also support for-profit initiatives consistent with general cooperation programming and objectives (AICS, 2019c). The CDP development bank also has the capacity to blend aid and credit to leverage private investment and to match funds collected through public funding (AICS, 2020a; Zupi, 2015: 31). Finally, AICS makes direct contributions to the private sector through public tenders for development projects in the sectors of industry, services, agriculture, fish and aquaculture. This scheme includes new businesses and start-ups as well as established Italian businesses operating in DAC-listed partner countries (AICS, 2020b). For-profit bodies must adhere to some of the same standards as non-profits to cooperate with AICS, and some businesses such as the armaments industry are explicitly excluded (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 1990: 3; Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2014: 27). The previous discussions have demonstrated that while the Italian institutional setting for transnational helping has always included a role for the private sector, this role has been expanded over time, making space for market values and business practices. The next section will briefly trace Italian funding for development to illustrate the interface between the spheres of public, private and political.

ITALIAN FUNDING FOR DEVELOPMENT

Funding is never neutral, whether it comes from the sale of products like those from the humanitarian organization/luxury brand collaboration that began this article, or from the Italian government's ODA, presented in smooth graphs from official data. Data on funding are always contentious. This section will present a brief review of Italian funding trends, first in public funding and then private.

Public Aid

For Italian public aid, MAECI collects data on official assistance from over 130 Italian institutions (ministries, universities, regional and local authorities, as well as AICS), and submits them to the OECD's DAC for validation (Ministero degli Affari Esteri, 2019). Military aid and the promotion of the donor country's security are excluded from such tallies, as are trade measures, such as export credits (OECD, 2019a: 1). Once approved, these data are published online by OpenAID, through a platform set up by the Italian Department for Public Administration aiming to ‘Strengthen national consensus on policy decisions on Italy's commitment in the field of international cooperation’ (Italian Government, 2016: 74)).12 This official website in English and Italian presents summary figures and data on monies committed and used, what they fund, where and how, from 2004 to 2016. The period since 2012 has been covered by Donor Tracker, from the social impact consulting group, SEEK Development, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.13 Aid transparency is no longer the domain of individual DAC donor states but is managed through private and philanthropic actors.

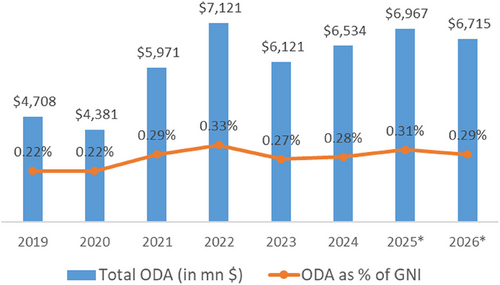

Data supplied by MAECI to OpenAID show that Italian ODA ebbed and flowed between 2004 and 2016; only in 2016 did it return to funding levels reached back in 2005, as illustrated in Figure 1. From Donor Tracker, we see that aid continued to grow until 2019 when the number of people seeking asylum declined, and expenditures fell accordingly (see Figure 2).14 In 2021, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and a return to higher spending on refugees, aid increased but dropped again in 2023. The data show a broadly upward trend in ODA since 2013, but the increase is mainly fuelled by expenses linked to ‘refugees’15 within Italy, which skyrocketed from € 304 million in 201316 to € 1.5 billion in 2022.17 This has been a point of contention across DAC countries. The New Humanitarian reported that ‘The money DAC countries spent on refugee costs at home outpaced humanitarian aid budgets by about a third — $29.3 billion for so-called in-country refugee costs compared to $22.3 billion on global humanitarian aid’ (Loy, 2023), and an Oxfam researcher cited in the same article claimed that ‘Donors have turned their aid pledges into a farce’ (ibid.). In 2023, over 20 per cent of Italy's ODA budget was allocated for Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni's € 1 billion ‘Albania project’, a refugee processing centre which was intended to keep asylum seekers outside Italian borders (Tondo, 2024), but which is currently ‘on-hold’ because it violates international law.18 Italy often uses multi-bilateral aid that involves giving bilateral donations to multilateral organizations while maintaining political alignment through earmarked funding. From observing the disaggregated reporting on ‘bilateral and multi-bilateral development assistance’,19 two important and linked trends emerge: first, when more money is spent, it is allocated to the category ‘refugees in donor countries’; and second, more modalities for using the funding have emerged over time, including those linked to business.

Italian Aid Flows 2004–16 (€ millions) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: OpenAID Italia, ‘Aid during the time’: http://openaid.esteri.it/ (last accessed 5 June 2025).

Italian Aid Flows 2019–26 (US$ millions and as % of GNI) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Years with asterisks are estimates.

Source: Donor Tracker, ‘Donor Profile Italy’: www.donortracker.org/donor_profiles/italy (last accessed 5 June 2025).

Private Funding for Helping, Including Development and Humanitarianism

Business involvement in Italian helping involves various forms of for-profit and philanthropic work. This article argues that the neoliberalization of development in Italy has resulted from relations between the state and business; this section therefore explains the role of private funding to non-profits in Italy, from individuals, foundations and companies. According to estimates based on tax declarations, donations from individuals in the 2016 tax year amounted to € 5.4 billion, an increase of nearly 10 per cent from the previous year (Arduini, 2019); this compared to € 873 million from companies, of which € 200 million came from corporate foundations (FIS, 2019a: 43). One interesting point is that some of the modalities for private aid were intended in their inception to provide support for the Catholic Church. Thus, the institutional forms of traditional charity become part of the Italian aid infrastructure. Overall, private funding has increased over time for Italian helping organizations (Arduini, 2019) and can take the form of individual donations, taxation, institutional philanthropy and corporate direct funding.

There are several ways for individuals to contribute to non-profit organizations, the simplest of which is direct donations. As in other OECD countries, these sums can be deducted from taxable income (up to 10 per cent of the taxable income) or taken as a tax rebate (currently 30 per cent of the sum to a maximum of € 30,000, or 35 per cent for organizations staffed exclusively by volunteers). Another common means of donating is through text messages or phone calls to dedicated premium-priced numbers promoted through media campaigns. Recognized non-profit organizations can apply for a premium number linked to a specific project (Codice, 2017: 15). In 2018, TIM, one of Italy's largest phone companies, collected € 11.3 million (80 per cent from landlines) through 128 fund-raising projects (65 per cent in Italy, 35 per cent abroad) (Telecom Italia, 2019); Vodafone and WindTre have similar initiatives (Vodafone, 2019: 57; WindTre, 2019).

Each person subject to direct revenue taxation in Italy can choose to allocate part of the tax amount due to a specific association or body. The main difference from an ordinary donation is that the taxpayer allocates funds that will be paid in any case as part of regular taxation. There are three different types of such optional allocations, two of which benefit international development. The otto per mille (‘8 per 1,000’) scheme allows the taxpayer to assign 0.8 per cent of the total taxes paid by all taxpayers nationally to a religious organization of their choosing. This provision was introduced in 1985, following an agreement between the Holy See and the Italian government. As the title of the 1985 law indicates (‘Provisions on ecclesiastic organizations and properties in Italy and on the support of Catholic clergy at the service of the dioceses’), this measure was originally limited to the Catholic Church, with the aim of giving a salary to its ministers. These salaries were meant to replace a previous wage integration under the 1929 Lateran Pact. Since then, the otto per mille scheme has been gradually extended to other religious bodies, with 12 currently eligible (Governo, 2019). The latest published data for the 2024 allocation (based on incomes from 2020 declared in 2021) show € 911 million allocated to the Catholic Church (70 per cent of the total), € 340 million to the government (24 per cent), and € 40 million for the Waldensian Protestant church (3 per cent), with all other churches receiving far less support (UAAR, 2024). The fact that taxes paid by those who do not select an otto per mille option are still used for the overall funding of the government is a source of considerable controversy, as is the fact that the scheme has increased the government contribution to the Catholic Church beyond its previous subsidy. The use of non-profit funds is also a matter of political debate because religious bodies advertise their charitable initiatives, but in fact spend the allocation on operational expenses and income for clergy (ibid.). In addition to the lack of state controls on the use of the funds allocated, critics also point to irregularities in the information about otto per mille choices forwarded by the tax support centres to the public authorities (Corte dei Conti, 2018: 19, 26). Italy's Court of Audit has been calling for a reform of the scheme since 1996, to no avail (ibid.: 25–26).

A second donation scheme cinque per mille (‘5 per 1,000’) was introduced in 2006 and allows the taxpayer to choose a beneficiary from among non-profits, scientific and health research institutes, universities, the social activities of city councils, amateur sport associations, and entities safeguarding natural heritage and protected areas (Ministero del Lavoro, 2019). Unlike the otto per mille, the amount each taxpayer can allocate is linked to their own individual taxes rather than to a percentage of the total tax collected nationally. Overall, in 2018, non-profit organizations received the largest portion of these funds (€ 334.4 million), followed by scientific and health research centres (€ 63.6 million and € 66.8 million, respectively), municipal social initiatives (€ 15 million), amateur sport associations (€ 13.7 million), and pro-heritage organizations (€ 1.6 million). Interestingly, Emergency,20 a humanitarian NGO working both inside Italy and abroad, was the second most popular non-profit to receive support from the scheme, coming only after AIRC, supporting cancer research (Gianotti, 2019).

Institutional philanthropy comes from foundations, corporate funders and other players that have their own financial resources, which they deploy strategically; they are independently governed, and use private resources for the public good, domestically or abroad. These organizations are bound by structures of accountability, public benefit and public reporting, and legal requirements (EFC, 2016: 3). In Italy, there are three principal types of institutional philanthropy (Italia Nonprofit, 2019a): banking foundations, community foundations and company/family foundations.

Banking foundations are independent, non-profit entities formed during the privatization of savings banks separating banking operations from philanthropic activities in the 1990s (ACRI, 2019). With a lineage that dates to the 19th century, the foundations now promote local and national development through grants and investments to non-profit organizations or local authorities. As of 2017 there were 88 banking foundations with total equities of € 39.8 billion (ACRI, 2018) and total revenues of € 2.1 billion (ibid.: 35). These foundations distributed € 984.6 million in 21 ‘permitted areas’, or issue areas defined by law (ibid.: 42, 103).

Community foundations, modelled after a US concept from the early 1900s, were introduced in Italy in 1999. They serve as mediators for philanthropy, managing legacies, wills and private charity (Assifero, 2017: 15). There are 37 such foundations in Italy, 27 of which were established by other foundations (Italia Nonprofit, 2019b). A 2017 questionnaire reported the total equities of 23 reporting foundations at € 191.7 million, with € 224.4 million in funds disbursed since the foundations were established (Assifero, 2017: 35–36). Their principal fields of activity are poverty eradication, education and training, personal services, heritage, unemployment and local development; their main beneficiaries are young people, disabled people, the elderly, refugees and immigrants, and women (ibid.: 34).

Company and family foundations are set up by companies or groups of companies to promote their own social responsibility, and there are currently approximately 150 of these in Italy. Family foundations manage family wealth to be used also for solidarity or social initiatives (Italia Nonprofit, 2019c). These types of foundations can act by granting resources or by implementing social projects directly. A peculiar case is Fondazione Italia Sociale (FIS), a private law foundation created within the context of the recent non-profit reform. FIS aims at creating a fund, through donations from both companies and citizens, to support social well-being and social equality within Italy, but it also engages in transnational helping. According to its statute, most of its funds must come from private donors (FIS, 2019b). After just two years in operation, its budget had reached € 700,000 (FIS, 2019c).

Companies can also make direct donations that remain separate from company foundations; these are deductible from corporate tax liability up to 10 per cent of the total, with no absolute upper threshold (Italia Nonprofit, 2019d). Companies can also donate goods, such as food, medicines and personal care items, including goods unsuitable for sale because of minor flaws (for example, in the packaging) but still suitable for use or consumption, and these donations are exempt from value-added tax charges (Normattiva, 2019: 16). Other common ways for companies to support non-profit organi-za-tion include schemes that allow individuals to make donations which are facilitated by the company, such as loyalty cards, wedding and Christmas gifts and employee fundraisers. In some cases, the company can still derive a tax benefit from the donation. Other schemes include direct donations of the company's own funds through sponsorships and co-marketing or ‘brand aid’ (Richey and Ponte, 2011) campaigns. Some non-profit organizations (see, for example, Emergency, 2018) have a public ethics code, excluding collaboration with specific industries or companies on ethical grounds.

An AICS-commissioned study found that 48 per cent of companies declared involvement in ongoing charity activities (De-LAB, 2017). However, for 61 per cent of the companies, these activities were not part of strategic corporate philanthropy but were reactive responses to emergencies and personal choices by company owners (ibid.: 16). Only 19 per cent of the responding companies — mainly the largest ones — have formalized guidelines for social engagement (ibid.: 17), and fewer than 8 per cent have adopted inclusive business practices (ibid.: 18) to proactively ‘contri-bute to human development by including the poor in the value chain as consumers, producers, business owners or employees’ (GIM, 2019). The study found that 41 per cent of companies were interested in developing such practices; these are mostly companies with a strong international vocation and are concentrated in the green economy and information and communication technology sectors (De-LAB, 2017: 19). Companies interested in ‘inclu-sive’ or development-focused business practices emphasized the possibility of co-financing with AICS (48 per cent) and tax benefits (23 per cent) as incentives (ibid.: 23). In short, state institutions are increasingly supporting private sector engagement, and internationally oriented companies see the business case for joining partnerships for development.

DISCUSSION: THE CRIMINALIZATION OF SOLIDARITY AND DECREASING PUBLIC TRUST IN BUONISTI

All the institutions mentioned here in the context of transnational helping in Italy are animated by shifting contexts of values and politics in the country. The significant shift in public discourse around the charity sector in Italy led to concerns about ethics and corruption, fuelled by the reporting of scandals in the non-profit sector. For example, there were claims that UNICEF in Italy was redirecting funds to a politician implicated in a scandal, further eroding public trust in the non-profit sector (UNICEF, 2018). These stories have led to a ‘do-it-yourself’ mentality among donors and corporations, who are increasingly creating their own foundations to support social causes instead of donating to existing organizations (Alvaro, 2018).

Reflecting what journalist Daniele Biella (2019) termed ‘the criminali-zation of solidarity’, Italian public attitudes have changed over the last decade also as a result of anti-migration sentiments. Between 2017 and 2019, Italy experienced a significant increase in this criminalization of solidarity, with various legal instruments used to target those aiding migrants. NGOs involved in rescuing migrants in the Mediterranean have been particularly targeted in a series of attacks (Info Cooperazione, 2017). Matteo Salvini, a populist politician who was the deputy prime minister until August 2019, spearheaded political attacks by suggesting that NGOs are working with human traffickers (Salvini, 2019a) and explicitly stated that NGOs help traffickers make money (Salvini, 2018). Salvini has also criticized Caritas, the Catholic pastoral organization established after the Second Vatican Council to promote human development, peace and justice. Salvini's co-deputy and then foreign minister, Luigi Di Maio, has referred to NGOs as ‘Mediterranean Sea taxis’ (Di Maio, 2017). These attacks on NGOs have been part of a broader xenophobic agenda of Salvini and Di Maio's political movement, which came to power in 2018, promising to put ‘Italians first’ and to ‘close ports’. Those who oppose this populist agenda are derogatorily labelled as buonisti or ‘do-gooders’, including individuals and organizations that help migrants, such as non-profits.

The criminalization of solidarity has been criticized by international organizations, including the United Nations and Amnesty International, for potentially violating human rights and deterring humanitarian efforts.21 There has been pushback from the side of the church in Italy, including the formation of a new movement called the Assisi Manifesto (OpenAID, 2020).22 This movement, inspired by Pope Francis's encyclical letter Laudato Si, mobilized a citizen-based movement to create an economy on a human scale against the climate crisis. While this movement emphasizes the importance of leaving no one behind, and of building a civilized, kind world (ibid.), it has not thus far had a noticeable impact on Italy's transnational helping.

Data on donations to non-profit organizations from 2017 show few effects of this change in attitude (Arduini, 2019; Info Cooperazione, 2019a; Vita, 2019). It is unclear how decreasing public trust in the non-profit sector will impact overall effectiveness, but it is opening a space for more involvement by for-profit businesses and for individualization of helping. A 2017 survey found that only 29 per cent of people who view ‘volunteering’ positively also had a positive attitude towards NGOs (Demos, 2017), which suggests that there may be a separation between the two concepts and that their futures may not be intertwined.

The relationship between politics and funding for Italian aid has been shifting as political priorities change. While there were significant increases in support and funding throughout the 2010s, more recent political priorities have reversed this. According to the OECD Peer Review, Italy's ODA experienced a sharp increase from 2012 to 2017, excluding in-donor refugee costs. However, ODA then decreased in 2018 (OECD, 2019b). Since then, the Italian government has reduced its allocation of funds to ODA, from € 5 billion in 2019, to € 4.7 billion each in 2020 and 2021 (Openpolis and Oxfam Italy, 2019), bringing it back to 2016 levels. Furthermore, ODA funds have been used for what Oxfam terms ‘inflated aid’ for refugees in Italy rather than providing more resources for development elsewhere (ibid.). The increased funding has thus prioritized border controls at the expense of fundamental services such as water, food and education, and has not reduced migration (ibid.: 11). Nonetheless, Italian politician Salvini promised to pursue trade and cooperation agreements only with countries that ensure control over migrants’ departures and readiness for deportations (Salvini, 2019b). This trend is concerning to Italian development professionals, who have expressed frustration over the subjugation of ODA to foreign policy considerations (Info Cooperazione, 2019b).

The current Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, embraces ‘cultural Christianity’ as a brand strategy for her regime's conservativism, but Italy's international development policy has arguably abandoned values of solidary or compassion in aid altogether (Dodman, 2024). Despite her photogenic relationship with the popular former Pope Francis, known for his compassion for refugees (Smith, 2025), Meloni's right-wing coalition government focuses on ever-harsher migration control at home, despite the country's need for migrant labour, and works to ‘prevent’ migration through free-market solutionism that emphasizes strategic partnerships and economic growth, particularly in Africa. In 2023, for example, the government announced a new partnership plan for international cooperation, called the Mattei Plan (named for Enrico Mattei, founder of the Italian energy company Eni) that will invest € 5.5 billion over four years in African countries, intended to counter Islamist radicalism, promote social stabilization, and support economic development by investing in strategic sectors, such as energy. At the 79th UN General Assembly in September 2024, Meloni highlighted Italy's foreign policy priorities: the Mattei Plan; combatting human trafficking; and AI governance. While the 2024 and 2025 aid budgets foresee nominal increases in development spending (reaching € 6.7 billion in 2025), a decline is projected starting in 2026, with an increasing share used for asylum seekers in Italy (Greco et al., 2024). Framed by the institutional relationship between the state, the church and the market in Italy, the neoliberal politics of aid has seen little contestation by the church and an increasing embrace by businesses at the centre of transnational helping.

CONCLUSIONS

The gaps between contemporary elite marketing of ‘development’ and the actual needs of the recipients of Italian public and private aid are not lessened by institutional politics. Where we might have expected more value struggles between the church, the state and the market, we have seen instead the organization of aid for profit. The Italian institutional context places the church and NGOs on the same institutional footing as private businesses. This article has shown how Italy's legal framework — encompassing both traditional development assistance and aid to asylum seekers in Italy — enables contemporary anti-immigrant politics to spill over into Italy's transnational helping. The church's influence is limited to ‘cultural Christianity’ embraced by Italian elites like Meloni, which obfuscates its lack of impact on Italian transnational helping in practice. Returning to the example of the jewelled pendant in support of Save the Children at the beginning of this article, Owen argues that ‘[a]ny organization that hosts gala dinner for billionaire supporters and has a Bulgari jewellery line in its name should accept that it will be seen as part of the elite’ which ‘makes good business sense’ for the organization (Owen, 2021: 53). This raises the question: so what if Italian NGOs want to raise money under the auspices of ‘help’? Is it a reasonable Faustian bargain if more funds are raised, and more children saved? Thus far, we have no reason to believe that the supposed beneficiaries are the ones ‘gaining’ from the neoliberalization of development.

Transnational helping, or the organization of do-gooding, as it was framed by Jo Littler (2008) almost two decades ago, is profitable for businesses and for their NGO partners. Buying a hand-knitted luxury sweater made by skilled artisans in a Peruvian prison (Richey, 2024) or drinking a ‘cup of hope’ from Starbucks’ collaboration with the Eastern Congo Initiative (Budabin and Richey, 2021; Richey and Ponte, 2021) gesture to a world where the playfulness, beneficence and good intentions of the donors are given priority over the needs of recipients or the ideals of sustainable development. The masters of these ceremonies of illusion are corporations, like Bulgari, skilled in selling ideas as products and linking products to desire. The beneficiaries are the largest, most professionalized organizations, like Save the Children, whose media savviness and presentation of good-doing can appease consumers and their elite norm-setters. Perhaps the other beneficiary of the distraction of glitzy marketing of the business of helping is the Italian government that can continue to call funds for the policing of its borders and support for its businesses ‘development’.

This article has charted the institutional context for Italian helping and its neoliberal politics of aid, and offers the following conclusions. First, the interface for ‘helping’ between government legislation, state bodies, businesses, NGOs, the church and individuals is rapidly changing, unevenly distributed, and sometimes quite opaque. Italian transnational helping is of very limited interest to the Italian public, and the media, long controlled by the parties in power, has little to gain from covering the debates, conflicts, or paradoxes that separate, in theory, the state from the church from the market. Often, humanitarian helping for refugees abroad is confused with support (or not) for asylum seekers in Italy. It seems that the discursive understandings, public opinion and actual funding are commonly mixed between humanitarian support and a positive disposition toward refugees. This resonates with the expanding critical scholarship on how value is extracted from refugees themselves in the provision of Italian humanitarianism at home (see, for example, Giudici, 2021; Martin and Tazzioli, 2023). There is also conceptual slippage in the academic literature between ‘humanitarianism’, when used to refer to helping abroad in times of crisis, and helping Black and brown people within Italian borders.

Second, corporations have always been part of the Italian development cooperation system as providers of services, funders of charity foundations, and participants in increasingly popular ‘profit + non-profit’ partnerships. The relationships are growing in importance as more resources are needed both at home and abroad, yet public aid remains politically contentious, and the neoliberal priorities of aid serve well the post-neoliberal political order of increasing authoritarianism in Italy

Third, the roles played by individuals as consumers, citizens and/or business owners in financing humanitarian helping are multiple. Notably, Italy is unique for its two systems of personal allocation of tax monies to chosen religious organizations (overwhelmingly the Catholic Church) through otto per mille, or to the non-profits of their choice through cinque per mille (where top recipients are AIRC, a domestic cancer charity, and Emergency, a humanitarian organization). However, in 2024, ‘for the first time since its inception’, the amount of funding for the Catholic Church as Italians’ choice for their otto per mille contribution fell below the € 1 billion mark — just one indication of the increasing secularization and mistrust of the church in Italy today (Faggioli, 2024).

Finally, it is interesting that Italy requires non-profit organizations to be at least minimally privatized (receiving at least 5 per cent of their income from private sources) to be eligible to apply for public grants, tenders and collaborations. This institutional framework shapes the environment of how helping is perceived — essentially as a private matter. Thus, it is not surprising that most contemporary data suggest that, in Italy, non-profits and corporations are forming ‘hybrid’ organizations to tackle global challenges and to support vulnerable persons and marginalized communities at home and abroad (De Marchi and Martinez, 2020: 6). Businesses, expected to demonstrate their ‘purpose’, partner with non-profits that can provide them with useful causes. This overall context provides fertile ground for forms of commodifying compassion and brand aid-style partnerships like that between Bulgari and Save the Children.

Biography

Lisa Ann Richey ([email protected]) is Professor of Globalization at the Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, where she works on the politics of transnational helping. Her recent books include Batman Saves the Congo: Business, Disruption and the Politics of Development (with Alexandra Budabin, University of Minnesota Press, 2021) and New Actors and Alliances in Development (co-edited with Stefano Ponte, Routledge, 2014). She also disseminates her work in popular media including Al Jazeera and The Conversation. She is currently leading a collaborative research project on ‘Everyday Humanitarianism in Tanzania’.

REFERENCES

- 1 United Kingdom Research and Innovation grant number ES/Po10873/1; the author was in attendance.

- 2 ‘It's never neutral funding. It's better to have another actor between the donors and the agencies’, stated Mark Bowden live at the conference (author's field notes). Bowden has been a senior humanitarian sector leader for over 30 years coordinating for the United Nations (UN), the British Government and Save the Children. See: odi.org/en/profile/mark-bowden/

- 3 See: www.bulgari.com/en-int/jewellery/necklaces/save-the-children-necklace-silver-black-356910

- 4 Another non-sectarian umbrella term used in the literature is ‘do-gooding’ (Littler, 2008).

- 5 That this was from the Italian branch was noted in disparaging terms by one respondent. Video interview, career humanitarian leader, 9 April 2024.

- 6 ‘Frippery for the rich’ was the term used by a humanitarian leader familiar with the product, who described it as ‘very expensive jewellery with nothing to do with poor people’. Video interview, 23 November 2023.

- 7 See: www.donortracker.org/donor_profiles/italy (accessed 26 May 2025).

- 8 See: www.openpolis.it/torna-a-ridursi-il-contributo-italiano-alla-cooperazione-allo-sviluppo/ (accessed 3 May 2024).

- 9 Video interview, 23 November 2023.

- 10 This government document and other sources for this article are published exclusively in Italian. Translations of quoted material into English are by the author and research assistants.

- 11 For an organizational diagram, see: www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/f11192cc-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/f11192cc-en

- 12 The OpenAID websites are part of a coordinated international effort to enhance ODA transparency and to introduce common standards coming out of the Fourth High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan, Republic of Korea, in 2011, which created a global commitment to transparency including the development of a digital open-data format under the name of IATI — The International Aid Transparency Initiative.

- 13 See: www.donortracker.org/about

- 14 DAC donors can report in-country refugee expenditures as part of ODA, but there are specific guidelines and restrictions they must follow. See: www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/oda-eligibility-and-conditions/in-donor-refugee-costs-in-official-development-assistance-oda.html (last accessed 20 May 2025).

- 15 I am using the report's own language, but it is important to recognize that most of these funds are for asylum seekers and not recognized refugees; thank you to an anonymous reviewer for clarifying this.

- 16 See: www.openaid.esteri.it/en/?year=2013

- 17 See: www.donortracker.org/donor_profiles/italy#oda-spending

- 18 See the (Italian language) video ‘Migrants: The Albania Project on “Standy-by”’: www.tgcom24.mediaset.it/2024/video/migranti-il-progetto-albania-in-stand-by-_90612795-02k.shtml

- 19 As defined by MAECI: ‘Bilateral transactions are those undertaken by a donor country directly with a developing country. They also encompass transactions with non-governmental organizations active in development and other, internal development-related transactions such as interest subsidies, spending on promotion of development awareness, debt reorganization and administrative costs’: www.openaid.esteri.it/en/?year=2004

- 20 See: en.emergency.it/what-we-do/humanitarian-programmes/ (last accessed 20 May 2025).

- 21 See: www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/02/italy-criminalisation-human-rights-defenders-engaged-sea-rescue-missions (last accessed 20 May 2025).

- 22 Assisi Manifesto downloaded from: www.symbola.net/manifesto2 (last accessed 8 March 2024).