When Governments Deliver: Migrant Remittances and the Willingness to Pay Higher Local Taxes

ABSTRACT

This article deviates from prior research which considers only national-level and formal taxes when examining tax attitudes and behaviours in migrant-sending countries. It investigates the relationship between the receipt of remittances and ‘conditional tax compliance’, and how it varies between the local and the national levels. The article posits that remittance recipients are willing to pay higher taxes at the local level in exchange for better services, but this willingness does not extend to higher levels of government. Data from the AmericasBarometer support this hypothesis: those receiving remittances show greater readiness to pay higher taxes for better municipal services. Statistical findings also reveal that recipients’ greater conditional tax compliance at the local level correlates with higher trust in municipal authorities, increased demand making on them, greater attendance of town hall meetings and closer engagement in community affairs, including making tax-like payments towards community-improvement activities. Contrariwise, at the national level, recipients of remittances display no greater willingness to pay higher taxes for welfare, no greater trust in state authorities, and lower participation in presidential elections. These findings suggest that a local perspective can provide deeper insights into the tax attitudes and behaviours of migrants and their families and the nature of state–society relations in migrant-sending countries.

INTRODUCTION

How do international remittances relate to tax attitudes and behaviours in migrant-sending countries? Previous research on Latin America and Africa has associated the receipt of remittances with an increased tolerance for tax evasion and tax resistance (Doyle, 2015; Konte and Ndubuisi, 2022; López García and Maydom, 2021). These results are informed by the so-called ‘fiscal contract’ on the basis of which individuals (agree to) pay tax according to the quantity and quality of goods and services they receive from the state (Levi, 1988). As migrants (rather than the state) become providers of welfare and a greater number of people come to rely on remittances as an untaxed source of income (Adida and Girod, 2011; Sana and Hu, 2006), the state is increasingly seen as an unreliable provider of public goods and services. Individuals are therefore less likely to demand public goods from the state (Germano, 2018) or to feel compelled to comply with tax schemes (López García and Maydom, 2021). As recipients’ demand for public goods and services decreases, so the argument goes, origin-country governments have less incentive to spend on public welfare (Abdih et al., 2012; Ahmed, 2012, 2013; Doyle, 2015; Ebeke, 2011; Mina, 2019). Declining public service provision further weakens the incentive of citizens to voluntarily comply with the payment of taxes in those migrant-sending countries.1

From this perspective, migrant remittances and weak fiscal contracts are self-reinforcing. Migrant-sending economies reflect the absence of a (functional) fiscal contract between the state and its citizens, while remittances simultaneously undermine the latter's trust in the former's ability to provide public goods in these countries — and hence the fiscal contract. This is more likely in remittance-dependent countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti and Honduras, where these monetary inflows account for over 20 per cent of GDP (Plaza, 2023). One could argue that in order to restore the fiscal contract and broaden the tax base in these labour-export economies, governments should consider taxing the income and assets of remittance-receiving households.2

However, so far, scholars have examined whether remittance recipients differ from non-recipients in their belief that paying tax is ‘the right thing to do’, independent of how the government uses the revenues thus derived (see Doyle, 2015; López García and Maydom, 2021). Tax morale, denoting the intrinsic, normative-driven motivation to pay tax, also known as voluntary (or unconditional) tax compliance, is distinct from conditional tax compliance, which depends on citizens’ views of a government's ability to deliver public services and goods in exchange for their tax contributions (Dom et al., 2022; Ortega et al., 2016). Less scholarly attention has thus been paid to how remittance recipients differ from non-recipients in terms of their sense of reciprocity or conditional tax compliance.

Until now, researchers have mainly studied the national level when analysing the relationship between remittances and taxation (see Bak and van den Boogaard, 2023). However, citizens receive public goods and pay tax at different levels of government (Vincent, 2023). In fact, in economies with high levels of informality, only a small proportion of individuals have experience of direct taxation by the central government; the majority pay taxes and fees collected at the local level instead (Anyidoho et al., 2022, 2025; van den Boogaard et al., 2019).3 Moreover, in these contexts, citizens engage more with local institutions and trust them to a greater degree than they do national institutions (Córdova and Hiskey, 2015; Sabbi et al., 2024). Although the perceptions of most taxpayers in developing economies are formed at the local level (Bak and van den Boogaard, 2023), studies on the political economy of international migration have largely overlooked local-level taxation and assume remittance recipients avoid, or are resistant to, direct forms thereof (Doyle, 2015; Ebeke, 2011; López García and Maydom, 2021; Tyburski, 2025). This ‘national bias’, which is common in cross-national studies, can lead to a misrepresentation of taxpayers’ views and, hence, unfounded conclusions (Bak and van den Boogaard, 2023) — for example, that remittance recipients do not pay or prefer to avoid paying tax. This is an important omission, and one that needs to be rectified.

Researchers also often assume that taxes can only be paid to the state. Yet, citizens frequently contribute to the financing of public goods by making tax-like payments to non-state actors, such as migrant associations (Bak and van den Boogaard, 2023). Sometimes, non-state actors collaborate with authorities (Duquette-Rury, 2019), making it difficult to distinguish between formal and informal taxation (van den Boogaard and Santoro, 2023). To better understand the tax perceptions of remittance recipients, one should consider both the formal and informal contributions that citizens make to the financing of public goods in developing economies (Bak and van den Boogaard, 2023), as well as the types of goods that they receive at the local and community levels.

In light of all this, the following questions are posed: how does the receipt of remittances relate to the willingness of individuals to pay higher taxes in return for better services, or conditional tax compliance? How do these attitudes vary across the local and national levels? This article argues that remittance recipients are more willing than non-recipients to pay higher municipal taxes for improved services, and that this can be attributed to the nature of the local fiscal contract and recipients’ greater political engagement at the local level. The local-level fiscal contract (unlike that at the national level) does not distinguish between beneficiaries of public goods based on their source of income. Remittances are untaxed income; recipients enjoy local goods but have limited access to national ones. When authorities deliver public goods and services, trust in them grows (Dom et al., 2022). At the local level, recipients may trust that the taxes they pay to local authorities will translate into public goods they benefit from directly. The local level also offers opportunities to citizens to engage in decision making which are unavailable at the national level (Sabbi et al., 2024).4 Recipients have greater resources and hence interact more with local authorities, participate more in decision-making processes, have a greater capacity for local action and are more involved in community life than non-recipients (Córdova and Hiskey, 2015; Goodman and Hiskey, 2008). They are therefore able to monitor more closely how public funds are spent, and bargain more effectively with local governments. While recipients can see how their political participation and civic engagement are reflected in better municipal services, the connection between taxes paid and services received at the national level is less evident. It is thus harder for this group of citizens to trust that national authorities will deliver public goods in exchange for their tax contributions (e.g. VAT) or to see how their political participation leads to improved services they benefit from.

This article tests these claims using survey data from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), a region with high migration and informality and where, consequently, most of the direct taxes that people pay are collected locally. Over the past three decades, subnational governments in the region have acquired increased responsibilities vis-à-vis public-good spending and revenue collection (Nickson, 2023). Relative to advanced economies, state and local tax revenues remain low across the region, with subnational governments relying heavily on central transfers.5 Yet, LAC exhibits high levels of fiscal decentralization compared to other world regions, such as Francophone Africa (Eguiño and Pineda Manheim, 2023). Community modes of revenue raising and service provision are also commonplace in LAC, particularly in rural areas (Goodwin et al., 2022).

Due to data limitations, the analysis presented here remains correlational. Despite this, findings still align with theoretical expectations. Compared to non-recipients, those receiving remittances are more willing to pay higher taxes if this means that municipal services improve. Statistical results additionally show that increased conditional compliance of recipients correlates with greater trust in local authorities, increased demand making, greater attendance at town hall meetings and closer engagement in community affairs, including making tax-like payments towards community-improvement activities. At the national level, in contrast, recipients exhibit no greater willingness to pay higher taxes for nationally provided goods, show no significant difference in their levels of trust in national authorities and are less likely to participate in presidential elections. A local perspective can thus offer a better understanding of the tax attitudes and behaviours of migrants and their families and the nature of state–society relations in migrant-sending countries.

This article contributes to the relatively limited body of research to date on the links between remittances and taxation in migrant-sending countries (Doyle, 2015; Ebeke, 2011; Konte and Ndubuisi, 2022; López García and Maydom, 2021; Tyburski, 2025). In so doing, it connects this literature with the wider scholarship on taxation and aid dependence (Blair and Winters, 2020), as well as research on informal taxation and informal welfare provision (van den Boogaard and Santoro, 2023; van den Boogaard et al., 2019). By highlighting the links between subnational government and transnational households, it also adds to the work done on diasporic development engagement and the study of local politics in LAC in general (Duquette-Rury, 2019; Eaton, 2020).

The article proceeds as follows. First, it reviews previous work on remittances and the financing of public goods and services in origin countries. Next, it advances a series of hypotheses on how the receipt of remittances shapes the willingness of individuals to pay higher local taxes. It then outlines the data and methods used to test these claims, presenting and interpreting the results through a series of statistical models. It concludes with a discussion of the implications for taxation and state building in migrant-sending countries and offers suggestions for new research avenues going forward.

REMITTANCES AND FISCAL CITIZENSHIP REVISITED

Tax capacity, and therefore tax enforcement, varies widely both within and between countries. However, tax compliance depends not only on the coercive enforcement or audit capacities of the state but also on citizens’ trust in authorities (Dom et al., 2022). Trust is more likely to arise when citizens believe that everyone is paying their fair share and that tax burdens are equitably distributed, when revenues are effectively translated into public goods and services, and when authorities are held accountable for their use of public funds. Put differently, conditional tax compliance is more likely when the actions of government align with the expectations citizens have regarding the allocation and distribution of public goods.

National Taxation

The fiscal contract involves multiple types of exchange and degrees of inclusion and, therefore, different notions of state–society relations at varying levels of government (Johansson, 2020; Plagerson et al., 2022; Rogan, 2022). National and local fiscal contracts thus differ in terms of the fairness and equity of the respective tax systems (Prichard and Dom, 2022). Central government authorities, for instance, collect income tax only from those individuals and firms employed in the formal economy — medium and high earners, for example. At the national level, those dependent on untaxed sources of income — such as informal workers or remittance-receiving individuals — pay consumption taxes but lack welfare benefits and consideration as formal contributors in the eyes of the central state. Migrant families are often left unprotected by the state, they lack social protection and must carry the welfare burden themselves (Doyle, 2015; Germano, 2018; Levitt et al., 2023). For migrants and their families, the national fiscal contract is therefore a ‘one-way street’ (Meagher, 2016). When individuals feel that the tax burden is unevenly distributed and/or they fail to receive public goods from the government, they are less likely to trust that authorities will deliver in return for their paying tax (Dom et al., 2022).

Whether citizens sanction authorities’ specific uses of tax revenues also depends on the value they place on state-provided goods (Martin, 2023).6 Poor healthcare provision, for instance, is more likely to mobilize an individual who relies on state-provided health services than an uninsured individual (who has private access to healthcare) to vote or protest against authorities (ibid.: 38). In LAC, national authorities mostly provide healthcare (and pension) services; only citizens who pay income tax benefit from them. For many individuals, emigration is a social-protection tool (López García and Orraca-Romano, 2019; Sana and Hu, 2006). Remittances are used by households to purchase healthcare, education and social protection on the private market. Because they have limited or no access to public welfare, recipients are less concerned about whether or not they receive these services from the national government and have fewer incentives to punish authorities for the (mis)use of such funds (Germano, 2018).

Previous research shows that in LAC and Africa, those receiving remittances are, compared to non-recipients, not only less supportive of paying tax to the (national) government but also more likely to justify tax evasion and be resistant to taxation in general (Doyle, 2015; López García and Maydom, 2021). Studies also indicate that these recipients have fewer incentives to participate in (formal) politics at the national level (Dionne et al., 2014; Ebeke and Yogo, 2013; Goodman and Hiskey, 2008; López García, 2018). As such, they are less likely to punish incumbents for tax misuse via the ballot box — that is, by not voting (Ahmed, 2017; Bravo, 2012; Germano, 2018; Tertytchnaya et al., 2018).

Local Taxation

Subnational authorities, in contrast, collect direct payments from citizens without distinction regarding income source or amount owed. Some of the ways in which local governments extract financing from citizens is through property taxes as well as fees for licences, permits and basic services (Anyidoho et al., 2022). Compared to the national level, theoretically, everyone should benefit from goods and services at the local level in exchange for their tax contributions, regardless of the source of their income (Fox and Pimhidzai, 2013). Furthermore, in contrast to national authorities, local governments can more readily connect increased tax revenue to better service provision through ‘quick win’ policies, such as adding more bus routes, making road repairs, increasing the frequency of waste collection, and so on. In this way, taxpayers can better see how their taxes contribute to the community. Readily making such a link adds to citizens’ trust in local authorities, thereby fostering conditional tax compliance (Prichard and Dom, 2022). Remittance recipients are thus more likely both to perceive the local tax system as fairer and more inclusive and to benefit from tax revenues in the form of the public goods and services offered in return. At the national level, in comparison, tax streams may be used to fund broader but at the same time less immediately visible initiatives.

As noted above, remittances play an insurance role. When families face adverse shocks, migrants often send more money home to help them cope. By providing financial support during hard times, remittances help households maintain stable consumption levels despite fluctuations in the national economy (Stark, 1991; Stark and Bloom, 1985; Yang, 2008). This stability allows recipients not only to maintain their everyday spending but also to feel confident enough to consume and invest more in things like education, health, housing or small businesses. As a result of this increased participation, recipients are more likely to pay direct taxes and fees at the local level. Empirical findings from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) show that, compared to non-recipients, those living in remittance-receiving households are more likely to report paying property taxes as well as levies, registration dues and licence and permit fees (López García and Maydom, 2021), all of which are tax-like payments collected at lower levels of government. Recipients are thus more likely than non-recipients to participate as direct taxpayers at the local level.7 Recent research in SSA furthermore shows that the often-assumed negative relationship between remittance receipt and tax morale/unconditional tax compliance does not hold in contexts where there are high levels of satisfaction with public services (Konte and Ndubuisi, 2022). If individuals benefit from high-quality public services (such as water supply), they are more likely to pay taxes, even if they receive remittances. Scholars have yet to thoroughly explore how receiving remittances influences citizens’ conditional tax compliance — that is, their willingness to pay higher taxes in exchange for better services — and how these attitudes vary across different levels of government.

In contrast to the national level, opportunities for citizen participation in decision-making processes go beyond taking part in elections at the municipal level. These include participatory mechanisms such as budget hearings and town hall meetings. In this way, taxpayers can gain information about bureaucratic procedures, voice their opinions on the use of public funds and monitor government actions. Those who attend these meetings or participate in local councils are also more likely to believe that authorities will take their concerns seriously, thus regarding them as trustworthy. Tax compliance is higher when individuals can shape and scrutinize tax schemes and related spending decisions (Dom et al., 2022). Research from Brazil shows that municipalities with participatory institutions collect more property tax than municipalities without such institutions (Touchton et al., 2019).8

One of the assumptions of existing literature is that taxpayers are more likely to get involved in politics compared to those who do not pay tax, because they care about the way in which the government spends their money (Martin, 2023). Empirical research conducted in LAC establishes a connection between the receiving of remittances and an interest in local politics and engagement with frontline officials; recipients are more inclined to sign petitions, participate in town hall meetings and make demands on local authorities (Burgess, 2016; Córdova and Hiskey, 2015; Pérez Arméndariz and Crow, 2010). Of course, a link existing between taxation and accountability is not a given, especially at the local level (Prichard, 2015). However, tax bargaining is more likely in the presence of collective action. Organized citizens are better equipped than lone individuals to monitor and demand concessions from the state in exchange for payment of fees (ibid.; van den Boogaard et al., 2022).

Besides money, migrants also transmit ‘social remittances’ such as knowledge and social capital to their communities of origin (Levitt, 1998). In LAC and Africa, remittance recipients have greater capacity and resources to participate in community-based organizations and non-electoral activities such as strikes and demonstrations (Dionne et al., 2014; Escribà-Folch et al., 2022; Goodman and Hiskey, 2008). To better understand the willingness of these recipients to pay higher taxes in exchange for better services and their higher levels of trust in and engagement with authorities, a local view of the fiscal contract is needed.

Informal Taxation

Besides the payment of formal local taxes, remittance-receiving citizens are more likely to contribute to the financing of local public goods and government activities through (informal) contributions to community-improvement schemes (van den Boogaard and Santoro, 2023; Lough et al., 2013; Olken and Singhal, 2011). Migrant hometown associations (HTAs), for instance, are groups that consist of out-migrants and locals who mobilize funds for undertaking public projects in origin communities (e.g. schools, health centres, water amenities, roads, paving, sewage systems, electricity provision and other public services). Migrant-financed projects commonly involve collective ownership and management by community members. Citizen participation spans the planning stage through implementation and subsequent monitoring. Contributions often go beyond cash payments, including in-kind (e.g. giving goods or materials instead of money), labour offerings (e.g. helping to build a school or repair roads), and organizational efforts (e.g. helping to coordinate a project, manage funds, oversee the maintenance of the project, etc.) (Olken and Singhal, 2011).

Migrant fundraising schemes on behalf of the community can operate independently of government (Adida and Girod, 2011; VanWey et al., 2005), potentially undermining citizens’ support for local taxation and reducing incentives for local authorities to levy it. Most often, however, HTAs in LAC coordinate with local authorities on the collection of funds and co-produce goods and services (Duquette-Rury, 2019; McKenzie and Yang, 2015; Orozco and García Zanello, 2008). Furthermore, research on Mexico's 3 × 1 Programme has reported proactive involvement in these migrant–state forms of collaboration resulting in heightened civic skills, greater awareness of local affairs, improved perceptions of local service provision and higher levels of trust in local government among migrant community residents (Burgess, 2012; Duquette-Rury, 2019; Waddell, 2015). Similarly, findings from empirical research conducted in SSA indicate that, when organized, citizens and local authorities are inclined to jointly invest (in terms of cash or labour) in public goods, to the benefit of both. Given these positive outcomes, they are also more likely to keep cooperating, with positive effects for trust in local authorities and formal taxation (van den Boogaard and Santoro, 2023).9 Core issues surrounding the relationship between remittances and (informal) taxation thus require further investigation from a local community-based perspective.

HOW REMITTANCE RECIPIENTS’ WILLINGNESS TO PAY TAXES VARIES ACROSS GOVERNMENT LEVELS

The central claim of this article is that the relationship between remittance receipt and the willingness to pay tax in return for improved services varies across different levels of government. In contrast to their national counterparts, local governments do not distinguish between public service beneficiaries based on the source of their income or whether they belong to the formal or informal economy. Recipients do not pay income tax, which funds national programmes such as social security. Therefore, recipients face more restrictions when accessing public goods and services provided at the national level (such as public healthcare or pensions) compared to those offered at lower levels of government, even though they may fund these goods via indirect (consumption) taxes. At the local level, it is therefore easier for recipients to see how government converts tax contributions into public goods from which they directly benefit, such as water and electricity provision or public lighting. It follows that recipients should be more willing to pay higher taxes in exchange for improved municipal services. However, this connection is less obvious at the national level, as remittance recipients have more limited access to goods and services provided by the central government compared to non-recipients. In contrast, since non-recipients are more likely to pay income tax and/or have access to nationally provided goods, such as social security or public healthcare, their willingness to pay taxes is less sensitive to whether public services are provided by local or national authorities. This gives us a number of hypotheses to be tested.

Hypothesis 1.Remittance recipients are more willing to pay higher taxes to local authorities in exchange for improved services compared to non-recipients.

Individuals are willing to pay higher taxes to authorities when they have confidence that they will receive public goods and services in return. In other words, greater trust in government is related to a higher willingness to pay tax. Remittance recipients should find it easier to trust local authorities, because they can directly see how their tax contributions are mirrored back in municipal services. However, they may find it harder to trust national authorities given that there is no clear or direct relationship between the tax payments that they make to, and the public benefits they receive at this level. Because non-recipients tend to receive public services from both local and national authorities, their trust levels across different levels of governments are more uniform.

Hypothesis 2.Remittance recipients trust local authorities more compared to non-recipients.

Recipients' organizational capacity and propensity to participate in local politics and civil society are also higher than those of non-recipients (Córdova and Hiskey, 2015; Goodman and Hiskey, 2008). Individuals who participate more actively in their communities — whether through voting, attending town hall meetings or setting up targeted initiatives — are more likely to monitor and make their voices heard on how authorities spend their tax contributions. At the local level, recipients can thus see how civil society activism translates into direct and visible public goods. Recipients' participation at the local level is thus likely to be associated with higher levels of trust in local authorities and a greater willingness to pay higher taxes in return for better municipal services. However, it may be more difficult for recipients to feel heard by national authorities or to see how their political participation and consumption taxes translate into better public services at the national level. In contrast, non-recipients may view their political participation at the local level as less salient, compared to their engagement with national political institutions.

Hypothesis 3.Remittance recipients are politically more involved and effective at the local level compared to non-recipients.

Individuals might be less inclined to pay higher formal taxes in return for better services if they are filling public service gaps through community contributions. However, compared to others, individuals who make informal, tax-like contributions are likely to be more invested in their communities and therefore more socially and politically active at the local level. Because of this, they are better able to hold local authorities accountable for the way in which their contributions are used or local problems are addressed. As people see that their concerns are heard and acted upon, trust in the local government grows. Individuals who make informal contributions to public goods may thus not necessarily oppose local authorities or view formal taxes as a burden but see them as complementary measures in improving community well-being. When there is trust that authorities will deliver better services, those who pay local levies should be more willing to pay higher taxes in return for better municipal services. Because recipients are more involved in local affairs, they are more likely to make informal, tax-like contributions to community goods (e.g. financial levies or volunteer efforts). Recipients’ greater community involvement is also likely to be associated with a higher capacity to monitor and negotiate with local authorities, and therefore heightened levels of trust in and a greater willingness to pay formal taxes to local authorities.

Hypothesis 4.Remittance recipients are more likely to fund public goods through community levies compared to non-recipients.

Data

The above claims are tested using data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP). Their survey instrument, the AmericasBarometer, was selected because it is nationally representative and includes questions on remittance receipt, willingness to pay (higher levels of) tax to the municipality, trust in local authorities, demand making on the latter, participation in town hall meetings and engagement in community-based associations and community-improvement activities through cash or in-kind donations. It also covers citizens’ participation in presidential elections, as well as their trust in authorities and demand making towards them in general. The countries and survey waves are included as Supplementary Information which is available in the online version of this article.10

Variables

To measure remittance receipt, a binary variable is used, coded as 1 if respondents answered ‘yes’ to the question, ‘Do you, or does someone in your household, receive money from abroad?’ (q10), and 0 otherwise. To measure citizens’ conditional tax compliance at the local level, a simple binary measure is employed, based on one question asked in the 2004–12 rounds of the LAPOP survey, namely: ‘Would you be willing to pay more tax to the municipality so that it can provide better services, or do you believe that it would not be worth doing so?’ (lgl3). Those who reported a willingness to pay more tax were coded as 1, and all who answered ‘no’ as 0.

Also used are two questions asked in the 2012–16 rounds of the LAPOP survey. The first was: ‘Would you be willing to pay more tax than you currently do in order for the government to spend more on primary and secondary education?’ (soc5). The second was: ‘Would you be willing to pay more tax than you currently do in order for the government to spend more on public health?’ (soc9). It is worth noting that neither of these questions references the level of government. In most of LAC, however, these welfare goods are usually provided by national authorities. In some cases, like federal democracies, subnational authorities also play a role in their provision, although their role is usually secondary. Thus, these questions are used as proxies for citizens’ willingness to pay higher taxes to authorities in return for better nationally provided goods.

Trust in local authorities is measured based on responses to the question: ‘To what extent do you trust the local or municipal government?’ (b32), while trust in national authorities is registered based on responses to the questions: ‘To what extent do you trust the national government?’ (b14) and ‘To what extent do you trust the president (or prime minister)?’ (b21a). These are all ordinal variables, ranging from 0 to 6, with higher values indicating greater trust in authorities.

To capture citizens’ demand making on authorities, two questions are posed. The first is: ‘In order to solve your problems, have you ever requested help or cooperation from any local authorities (mayor, municipality, prefect)?’ (cp4a). The second is similarly framed, but does not specify the level of government: ‘Have you sought help of or presented a request to any office, official or council person from the municipality within the past 12 months?’ (np2).

Participation in town hall meetings and local councils is measured based on responses to the question: ‘Have you attended a town hall meeting or other meeting convened by the mayor in the past 12 months?’ (np1). This is a binary variable; those who answered ‘yes’ were coded as 1 and those who answered ‘no’ as 0. Participation in national elections is registered as a dichotomous variable, coded 1 if respondents reported having voted in the most recent presidential elections, and 0 otherwise (vb2).

Active involvement in community-based organizations is measured based on responses to the following question: ‘In the past year, have you contributed or tried to contribute to solving a problem or to bringing about any improvement in your community or your neighbourhood?’ (cp5). In the 2004–06/07 rounds, respondents who answered yes to this question were subsequently asked whether they had engaged in the following community-improvement activities: (i) donating money or material goods (cp5a); (ii) contributing through their own work or manual labour (cp5b); (iii) attending community meetings (cp5c); or (iv) helping to organize a new community group (cp5d). Responses to these questions are coded as binary variables of 1 for ‘yes’ and 0 for ‘no’; those related to labour or cash (in-kind) contributions to community goods are treated as measures of citizens’ participation in informal taxation schemes.11

Since the willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for public goods might depend on being satisfied with the public services received (Konte and Ndubuisi, 2020), models include as controls certain variables measuring citizens’ evaluation of municipal goods and services (sgl1) as well as their reported satisfaction with public education (sd3new2) and public healthcare (sd6new2). These are ordinal variables, with higher levels indicating their assessment of receiving better-quality public services. Respondents’ demographic and socio-economic characteristics — including age, gender, rural/urban residence, education, employment status and wealth12 — are also considered. This ensures that any correlations we might find between remittances and willingness to pay higher taxes are not simply due to the inclusion of those with additional resources (including from remittances). Table S2 provides a full description and summary statistics for all variables used in the respective analyses.

Empirical Strategy

Given the nature of the outcome variables, (ordered) probit models are employed. Table S8 depicts estimation results with alternative model specifications — (ordered) logit and ordinary least squares. Due to the (non-longitudinal) nature of the data, no causal claims can be made. Hence, the analysis in this article is purely correlational. Since the key questions remain the same throughout the waves, the data are pooled. Also included are dummies for every survey wave to control for unobserved or unmeasured differences across countries over time. Country-level weights are used in calculating the descriptive statistics, as well as in all the regression analyses.14

Addressing the Problem of Selection on the Observables

It is important to note that remittance receipt is not randomly assigned across individuals in the sample. Members of migrant households are self-selected and, therefore, differ from non-recipients on several observable characteristics (e.g. area of residence, age, gender, income and education levels). In the sample, for instance, those receiving remittances are less likely to be working or employed (difference = −0.041, p < 0.001) while, simultaneously, more likely to be younger (difference = −1.16, p < 0.001), reside in urban areas (difference = +0.01, p < 0.001), have a greater number of years of education (difference = +0.47, p < 0.001) and have higher levels of wealth than non-recipients (difference = +0.58, p < 0.001) (Figure S2).

Entropy balancing is employed to mitigate the problem of ‘selection on observables’ (Hainmueller, 2012). Entropy balancing is a non-parametric approach, but unlike coarsened exact matching, there is no loss in the number of observations made. This matching strategy allows the construction of a synthetic ‘control’ for the treatment group by applying a set of weights. In this case, the treatment group consists of respondents who live in remittance-receiving households. Moreover, sampling weights are considered alongside balancing weights; meanwhile, matching weights are constructed to achieve almost perfect balance between the treatment and control groups, minimizing the risk of selection bias. Entropy balancing is, therefore, the appropriate strategy to use in this instance.

To produce balance across the treatment and control groups, the following variables are considered: age, gender, area of residence (urban/rural), level of education, employment status and wealth. By matching the means of these covariates between remittance recipients and non-recipients, this approach allows us to better separate the influence of remittances from other factors shaping individuals’ tax preferences and thus create more valid comparisons (Figure S1). Differences in the means between the treatment and control groups and the related t-statistics and p-values (Table S3) confirm that the samples of recipients and non-recipients are well-balanced on observable characteristics.

RESULTS

Descriptives

In the full sample, 14.2 per cent of respondents reported receiving remittances from abroad. Approximately 23 per cent reported being willing to pay higher levels of municipal tax if it meant improved public services; 31 per cent expressed willingness to pay higher taxes specifically for improved public education; and 32 per cent are willing to do so for better public healthcare. The mean value of trust in local authorities is 3; the mean value of trust in national authorities is also 3, each measured on a scale from 0 to 6. Across countries, however, there is significant variation (Figures S2–S5).

Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas, has both the highest proportion of remittance recipients among its population (51 per cent) and the greatest share of individuals willing to pay higher local taxes in return for public goods (80 per cent). However, its citizens harbour the lowest levels of trust in local authorities (2.05). In contrast, Chile has the smallest share of remittance recipients (1 per cent), Panama the smallest share of respondents willing to pay higher municipal taxes in return for public goods (11 per cent) and El Salvador the highest level of trust in local authorities (3.6).

Uruguay has both the highest level of trust in national authorities (3.98) and trust in the president (3.66) and the largest proportion of individuals willing to pay higher taxes for improved public welfare, including healthcare (56 per cent) and education (57 per cent). In contrast, Brazil has the smallest share of respondents willing to pay higher taxes in return for education (20 per cent) and healthcare services (23 per cent). Peru records the lowest level of trust in national authorities (2.2).

Regression Results

This section presents the results of the regression models described above, after accounting for selection effects. The results reported below come from a series of models that include the full set of control variables, survey rounds and country-fixed effects, as discussed above. Full regression model results are reported in the online Supplementary Information. Since remittance receipt is not randomly assigned, all results should be taken as correlational, not as the causal effect of the variables.

First, the relationship between remittance receipt and conditional tax compliance at the local level is examined. The regression results are displayed in Table 1. Coefficients are reported as marginal effects, with all dummy variables set to 0 and average values for all other covariates. Estimates are consistent with expectations: remittance recipients are 2.9 per centage points more willing to pay higher local taxes if municipal services improve (supporting H1). The magnitude of the marginal effect of remittance receipt is not negligible. It is 44 per cent greater than that of moving from a rural to an urban area, which corresponds to a 1.8 percentage point higher willingness to pay taxes. It is also comparable to the average marginal effect of moving from having no education to being high-school educated, which is 3.3 percentage points. Although the marginal effect of remittances is not as large as that of having a college degree, which is 7.1 percentage points, remittances are more immediate, unlike education or wealth, which take time to accumulate. For instance, a one-unit increase on the 12-point wealth index is related to a 0.4 percentage point increase in the probability of willingness to pay taxes. To match the marginal effect of receiving remittances on willingness to pay taxes, wealth would need to increase by 2.5 standard deviations. Moreover, the coefficient of remittance receipt remains significant after adjusting for covariates and individual assessments of local services, with higher levels of satisfaction with local goods being associated with a greater willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for public goods (Table 1, Model 3).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remittance receipt | 0.029*** | 0.026*** | 0.025*** | 0.024*** | 0.024*** | 0.023** | 0.022** | 0.023** | 0.020** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Trust in local authorities | 0.026*** | 0.025*** | |||||||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||||||

| Help from local authorities | 0.052*** | 0.029** | |||||||

| (0.009) | (0.009) | ||||||||

| Help at municipal offices | 0.050*** | ||||||||

| (0.009) | |||||||||

| Townhall meetings | 0.077*** | 0.057*** | |||||||

| (0.009) | (0.009) | ||||||||

| Community activities | 0.043*** | 0.028*** | |||||||

| (0.006) | (0.007) | ||||||||

| Quality of local services | 0.098*** | 0.076*** | 0.097*** | 0.098*** | 0.098*** | 0.097*** | 0.076*** | ||

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||

| Female | −0.047*** | −0.051*** | −0.052*** | −0.049*** | −0.052*** | −0.050*** | −0.048*** | −0.048*** | |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | ||

| Age: 35–54 years | −0.006 | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.010 | −0.010 | −0.007 | −0.013+ | −0.012+ | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Age: +55 years | −0.032*** | −0.031*** | −0.036*** | −0.033*** | −0.031*** | −0.033*** | −0.036*** | −0.043*** | |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| Urban | 0.018* | 0.021** | 0.018* | 0.018* | 0.019* | 0.017* | 0.018* | 0.011 | |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | ||

| Secondary | 0.023* | 0.024* | 0.024* | 0.023* | 0.025** | 0.022* | 0.021* | 0.020* | |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.010) | ||

| High school | 0.033*** | 0.032*** | 0.032*** | 0.032*** | 0.032*** | 0.031*** | 0.029*** | 0.030*** | |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| College or higher | 0.071*** | 0.073*** | 0.077*** | 0.072*** | 0.069*** | 0.066*** | 0.067*** | 0.066*** | |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | ||

| Wealth (index) | 0.004* | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003+ | 0.003 | 0.003+ | 0.002 | 0.003* | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||

| Employed or working | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.000 | |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.007) | ||

| N | 43,664 | 43,641 | 41,148 | 40,400 | 40,935 | 40,541 | 39,078 | 40,878 | 37,956 |

| F-statistic | 49.10 | 38.69 | 46.08 | 51.82 | 45.44 | 47.32 | 46.15 | 44.53 | 47.59 |

- Notes: Matched sample. Country and wave dummies are included but omitted from the table for ease of presentation. Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients displayed as marginal effects. Coefficients significant at + p < 0.10 *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. All F-test p-values are <0.001.

- Source: AmericasBarometer (2004–12).

Furthermore, the coefficient of remittance receipt decreases but remains significant after accounting for citizens’ interactions with local authorities and community-based engagement. As expected, a 1-point increase in trust in local authorities is associated with a 0.26-point increase in a person's willingness to pay (higher) local taxes (Model 4). Similarly, citizens who had made demands on local officials or municipal offices are more willing to pay (higher) taxes in return for better municipal services, by 5.2 and 5 per cent, respectively (Models 5–6). Citizens who attend meetings convened by local authorities are likewise (7.7 per cent) more willing to pay higher local taxes than other citizens (Model 7). Meanwhile, participation in community improvement activities is associated with a 4.4 per cent greater willingness to pay higher municipal taxes (Model 8). Additional models (reported in Table S7) show that individual willingness to pay higher taxes in return for better municipal services is positively correlated with the propensity to make both cash and in-kind labour contributions to community goods, establish new community organizations and attend community meetings. As we will see below, remittances are not only directly associated with a higher willingness to contribute to local taxes for public goods, but also indirectly, through greater trust and increased political and civic engagement.

Next, the relationship between remittance receipt and citizens’ willingness to pay higher taxes for improved goods provided at the national level is explored. As noted earlier, AmericasBarometer does not include specific questions about respondents’ willingness to pay higher taxes in exchange for better nationally provided goods. However, it does include questions about their willingness to pay higher taxes in exchange for better public education and healthcare. As mentioned, in most LAC countries, the central government is responsible for providing social insurance, such as pensions or healthcare, to people who contribute taxes while working and who receive benefits when needed. Also, a common assumption in the political economy of international migration is that remittances are used as a transnational form of social protection (Germano, 2018). Therefore, these questions are used to estimate the relationship between remittance receipt and citizens’ willingness to pay higher taxes to the central government conditional on improved services.

The results of the regression models estimating these dependent variables are reported in Table 2. Across models, the coefficient of remittance receipt approaches 0 and lacks statistical significance. That is, people who receive remittances do not statistically differ from non-recipients in their support for making increased tax contributions in return for better public education. Nor are there significant differences between remittance recipients and non-recipients regarding their willingness to pay higher taxes in return for improved public healthcare. These results hold after controlling for satisfaction with public education and healthcare services (Models 2 and 6), trust levels in the national executive (Models 3 and 7)15 and reported participation in the most recent presidential elections (Models 4 and 8). These findings contrast with those at the local level, where recipients are more willing to pay higher taxes in exchange for better municipal services, but they align with expectations. At the national level, it is more difficult for remittance recipients to make a connection between their tax contributions and the public goods they receive from authorities. This is reflected in the absence of a significant relationship between remittance receipt and willingness to pay higher taxes for better public education and healthcare, services that are commonly provided by higher levels of government.

| DV: | Support for higher taxes for better education services | Support for higher taxes for better health services | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Remittance receipt | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.021 | 0.034 | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.006 |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| Satisfaction with public education | −0.007 (0.016) |

|||||||

| Satisfaction with public healthcare | −0.006 (0.016) |

|||||||

| Trust in the president | 0.020*** (0.006) |

0.012 (0.006) |

||||||

| Voted in the most recent presidential elections | −0.057* (0.027) |

−0.038 (0.029) |

||||||

| Female | −0.038 | −0.042 | −0.039 | −0.022 | −0.022 | −0.021 | ||

| (0.025) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | |||

| Age: 35–54 years | −0.061* | −0.052* | −0.047 | −0.044 | −0.041 | −0.034 | ||

| (0.025) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.029) | |||

| Age: +55 years | −0.088* | −0.093** | −0.082* | −0.071* | −0.082* | −0.072* | ||

| (0.035) | (0.033) | (0.034) | (0.036) | (0.034) | (0.036) | |||

| Urban | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.010 | −0.014 | −0.012 | −0.013 | ||

| (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |||

| Secondary | 0.023 | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.099* | 0.098* | 0.090* | ||

| (0.040) | (0.039) | (0.039) | (0.039) | (0.038) | (0.038) | |||

| High school | 0.061 | 0.077* | 0.067* | 0.041 | 0.047 | 0.041 | ||

| (0.035) | (0.033) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.034) | |||

| College or higher | 0.074 | 0.095* | 0.092* | 0.025 | 0.035 | 0.031 | ||

| (0.039) | (0.037) | (0.037) | (0.041) | (0.040) | (0.040) | |||

| Wealth (index) | 0.023*** | 0.022*** | 0.022*** | 0.030*** | 0.030*** | 0.030*** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||

| Employed or working | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.056* | 0.048 | 0.059* | 0.060* | ||

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |||

| N | 10,601 | 9,811 | 10,372 | 10,418 | 10,681 | 10,209 | 10,451 | 10,496 |

| F-statistic | 9.644 | 8.246 | 9.225 | 9.019 | 7.512 | 6.924 | 6.938 | 6.735 |

- Notes: Matched sample. Country and wave dummies are included but omitted from the table for ease of presentation. Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients displayed are marginal effects. Coefficients significant at *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. All F-test p-values are <0.001.

- Source: Americas Barometer (2012–16).

Mechanisms

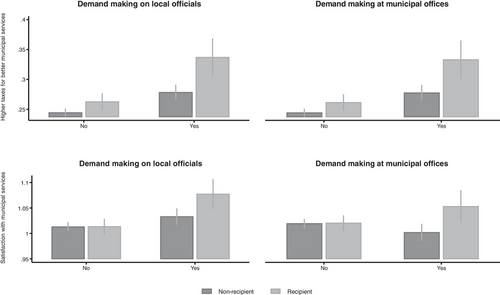

Findings thus far validate the claim that individuals living in remittance-receiving households are more willing to pay higher taxes in return for improved municipal services (H1). But what are the mechanisms behind this relationship? Results indicate that remittance recipients are more engaged in local decision making than non-recipients (supporting H3). More specifically, recipients are 2.8 per cent more likely to have made a demand on a local official in the past year, 2.5 per cent more likely to have ever requested help at a municipal office and 2.3 per cent more likely to attend town hall meetings compared to non-recipients (Table S6). Moreover, recipients are more likely than non-recipients to be satisfied with the quality of municipal services when they make demands on local authorities.16 The association between such demand making and willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for better services is also stronger for recipients than non-recipients (see Figure 1).17 When recipients feel that they are heard by authorities and/or their needs are being met, they are more willing to pay higher taxes.

Conditional Tax Compliance, Satisfaction with Municipal Services and Demand Making on Local Authorities per Remittance Receipt

Note: Predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals.

Source: AmericasBarometer (2004–12); http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/

Besides that, remittance recipients are 4.8 per cent more likely to participate in community-improvement activities, compared to non-recipients. This holds across all kinds of endeavours asked about in the respective survey rounds, from making cash donations to attending community meetings. Relative to non-recipients, recipients are 3.9 per cent more likely to make in-kind labour contributions, 3.1 per cent more likely to set up new community organizations, 2.9 per cent more likely to make cash donations to community-improvement schemes and 2.7 per cent more likely to attend community meetings (Figure S6). In other words, relative to non-recipients, recipients are more likely to report having paid informal taxes (supporting H4).

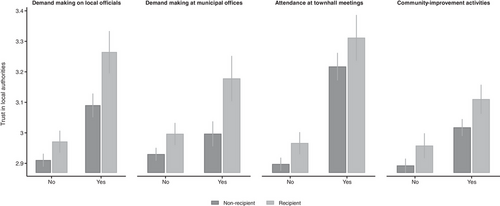

Consistent with expectations, results indicate that trust in local authorities is significantly higher when individuals interact with the latter as well as participate in community activities (Table S5). Also as predicted, remittance recipients place higher levels of trust in local authorities (+0.09 points) than non-recipients do (supporting H2). Moreover, recipients place more trust in local authorities when they make demands on them compared to non-recipients (see Figure 2).18 In sum, having direct interaction with frontline officials is associated with higher levels of trust in local authorities, greater satisfaction with municipal services and a stronger willingness to pay more tax for better services among remittance recipients. In contrast, non-recipients report lower levels hereof based on their own similar interactions.

Trust in Local Authorities, Engagement with Local Officials and Community Participation per Remittance Receipt

Note: Predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals.

Source: AmericasBarometer (2004–12); http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/

Findings thus validate the claims that recipients’ increased willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for better services relates to their higher trust in local authorities and greater local engagement. However, this is not the full story. As noted in the models estimating willingness to pay higher taxes (see Table 1 above), the remittance receipt coefficient remains significant even after accounting for trust- and engagement-related variables. This may have to do with the nature of the local fiscal contract. As discussed, at the subnational level recipients have greater access to public goods and services and can thus more easily associate the taxes they pay with the benefits they receive in return from authorities. However, it is more challenging for them to make these connections at the national level.

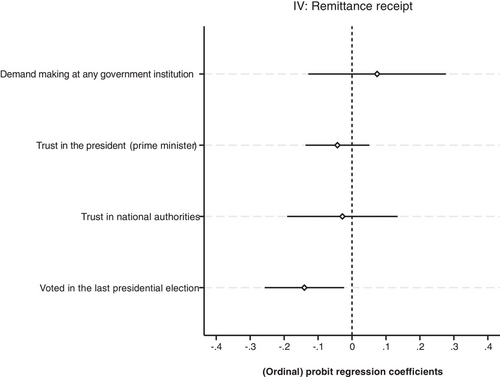

Indeed, as depicted in Table 2 above, recipients do not differ from non-recipients in their willingness to pay higher taxes for better public education or healthcare, as services commonly provided by national authorities. Results furthermore indicate that there is also no significant difference between recipients and non-recipients when asked about their demand making vis-à-vis any government institution, whether national or local. Although recipients are (1.7 per cent) less likely than non-recipients to report participation in presidential elections, they do not differ from non-recipients in their trust levels towards national authorities or the president (see Figure 3 below). This aligns with expectations.

Trust in National Authorities and Voting in Presidential Elections per Remittance Receipt.

Note: Predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals

Source: AmericasBarometer 2012‒16/17; http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/

SENSITIVITY CHECKS

Additional Variables

While remittance recipients might still participate in the labour force, empirical findings suggest that they predominantly do so in the informal economy (Ivlevs, 2016). To account for the overlap between remittance recipients and informal workers, the models include a dichotomous measure of reported self-employment status (ocup1a). While this is not a perfect indicator of participation in the informal economy, self-employed individuals often lack formal employment contracts or access to social security benefits such as public healthcare or pension schemes. Even after accounting for this variable, remittance receipt remains significantly associated with a greater willingness to pay higher taxes in return for better municipal services (Table S9). This may be due to recipients having a greater capacity to participate in local politics and community life.

To address the possibility of a person being less willing to pay higher taxes in return for better services when they intend to emigrate from their country of origin, a binary variable measuring individual plans to work or live abroad in the future (or serious consideration thereof) is also included (q14). This variable is highly correlated with remittance receipt and might capture some of the intrinsic characteristics of this demographic as it relates to a willingness to pay higher levels of local taxation. Findings show that the positive relationship between remittance receipt and willingness to pay higher local taxes holds after considering this variable. In fact, emigration aspirations (plans) are not associated with individuals’ reported willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for better services (Table S9, Model 2). Since the experience of (return) migration may shape individuals’ views of local goods as well as attitudes towards taxation in the origin country (López García et al., 2024), the models also include a binary variable measuring whether respondents have previous experience as migrants (q14h). Baseline results remain consistent after the inclusion of this variable: former migrants do not vary from other individuals in their willingness to pay higher taxes (Table S9, Model 3).

Corruption experiences might influence the provision of public goods and, hence, the trust of citizens in the capacity of authorities to deliver them. Previous research shows that individuals who experience petty corruption are less supportive of taxation (Jahnke and Weisser, 2019) and that remittance recipients are more likely to be asked to pay bribes (Ivlevs and King, 2017; Konte and Ndubuisi, 2020; Wong et al. 2024; Yeandle and Doyle, 2023). Thus, I examine whether the relationship between remittance receipt and conditional tax compliance holds when considering experiences of being asked to pay a bribe at the local level. Here, a binary variable was employed based on the responses to a series of questions asking about solicitation to pay a bribe to secure particular services at a municipal office in the year preceding the survey (exc11). The point estimate of remittance receipt remains significant after accounting for this experience. Having previously been asked to pay a bribe is not associated with citizens’ willingness to pay higher local taxes (Table S9).19

Criminal violence is widespread across LAC, with victims personally experiencing the state's failure to provide security. This can affect the fiscal contract, whereby governments are expected to provide security and welfare goods in exchange for taxation (Flores-Macías, 2022). Past research also associates the receipt of remittances with a greater likelihood of experiencing crime (López García and Maydom, 2021). To capture respondents’ exposure to criminal behaviour, a binary variable was used to measure whether they or a member of their household had been a victim of a crime in the 12 months before the survey (vic1ext, victim). Findings show that experiencing violent crime is not significantly related to individuals’ willingness to pay higher taxes to municipal authorities. Even after accounting for this variable, the coefficient of remittance receipt remains significant (Table S9).

Lastly, support for taxation might vary according to political ideology. This variable was measured on a scale from 0 to 9, with higher values indicating stronger identification with the Right and lower values with the Left (l1). Baseline results remain consistent after adding this variable into the mix (Table S9).

Heterogeneity Checks

Now it is explored whether the relationship between remittance receipt and willingness to pay higher local taxes in return for better services displays heterogeneous responses according to people's socio-economic and demographic characteristics (Table S10). At all wealth levels, the receipt of remittances is found to be positively related to an individual's willingness to pay higher local taxes in exchange for better services. This result suggests that this association does not apply merely to those recipients who are becoming wealthier and paying higher taxes to local authorities. Heterogeneous responses are also not detected along the lines of age, gender,20 rural/urban residence or (self-)employment status. This excludes the possibility that the receipt of remittances is capturing unobservable heterogeneity not controlled for in the respective models.

Outlier Checks

Since findings might change when focusing on a specific country context or time period, regressions were run excluding one country and one survey round each time.21 This was also done because there are three federal democracies in the LAC region: Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Although the magnitude of the coefficients differs when excluding particular countries and years, the results are similar to the baseline specifications (Tables S13, S14).

CONCLUSION

The subnational dimension has often been overlooked in past quantitative research on the relationship between migrant remittances and taxation. This article addresses that gap by examining how remittance receipt is associated with individuals’ willingness to pay higher taxes, and how this relationship varies between the local and national levels of government. It has been posited that the receipt of remittances is associated with a stronger willingness to pay (more) tax in return for better municipal services. Despite the results presented here being correlational, they still support this claim. Consistent with expectations, the willingness of an individual to pay higher taxes in return for better municipal goods and services correlates with their trust in local authorities as well as greater civic and political engagement at the local level. Findings indicate that compared to non-recipients, recipients trust local authorities more, are more likely to make demands on them and are more engaged in local politics (Córdova and Hiskey, 2015) and community life (Goodman and Hiskey, 2008). Individuals who make demands on local officials show higher levels of conditional tax compliance, trust in authorities and satisfaction with public services. Moreover, these links are stronger for remittance recipients than for non-recipients. However, these patterns are not observed at the national level. Recipients do not differ from non-recipients in their willingness to pay higher taxes for better welfare services, nor in their trust levels in national authorities.

The analysis shows that, besides formal taxes, remittance recipients are more willing to contribute to the financing of public goods and government activities through communal levies (Duquette-Rury, 2019), and that participation in community fundraising is associated with a higher willingness to pay taxes in return for better municipal services. Although remittance recipients are self-selected, findings remain robust after matching individuals on observable traits and controlling for a set of potential confounders. Estimates even hold true after excluding outliers from the sample and controlling for additional variables. No heterogeneous effects are detected depending on personal attributes theoretically related to tax attitudes.

The evidence presented here thus adds nuance to the conclusions from previous works, suggesting that migrant remittances are associated with lower tax morale and greater tax resistance (Doyle, 2015; López García and Maydom, 2021; Tyburski, 2025).22 The findings presented in this article show that when municipal governments deliver public goods and services, recipients are more willing to pay higher taxes. Ignoring the local level provides a distorted understanding of tax attitudes in migrant-sending communities, as most developing countries levy taxes at different levels of government.

This study has certain limitations. Due to the nature of the data, the results presented here are only correlational and hence questions of endogeneity or reverse causation cannot be ruled out. Although it may seem unlikely that people who are more willing to pay taxes for better municipal services are also more likely to emigrate or receive remittances, it is possible if we bear in mind that taxes are collected and public goods are provided at different levels of government. As discussed earlier, remittances serve an insurance function (Yang, 2008). People often leave their countries and send remittances back home to compensate for a lack of or restricted access to public goods (Germano, 2018; López García and Orraca-Romano, 2019; Sana and Hu, 2006), which, in the LAC context, are commonly provided by central (not local) governments. Future studies should address these limitations.

One could also consider that individuals who are willing to pay higher taxes to fund better municipal services might ask family members abroad to send remittances to enable the payment of taxes which helps to improve the well-being of their communities. Although I do not have data to test it, this idea is consistent with previous (qualitative) research on Mexican migrants in the United States, which shows how they organize abroad to send funds back home for schools as well as water, electricity and sanitation provision; this is often done in collaboration with local authorities (Duquette-Rury, 2019). Future scholarship, therefore, not only needs to differentiate between local and federal taxes and public goods, but also must consider local-level tax-like payments when analysing the links between migrant remittances and taxation in developing economies.

It is also possible that the conditional tax compliance of those receiving remittances is influenced by remittance senders. Migrants’ willingness to send money home can, for instance, decrease when taxes increase, with negative consequences for the local fiscal contract in origin countries (see Tyburski, 2025). Unfortunately, this article could not address this aspect as AmericasBarometer only covers in-country residents, not migrants living abroad. Exploring in greater detail how remittance senders might influence the tax attitudes of migrant households would certainly be an interesting line of research.23

Longitudinal surveys that include more refined questions on emigration, remittance receipt and how individuals’ conditional tax compliance and evaluations of the capacity of local and national authorities to deliver public goods and services change over time could be designed and used to validate the results obtained here. Experiments could likewise help provide causal leverage on the relationship between remittances and conditional tax compliance. Data on individuals’ reported payment (or refusal) of local taxes, the amount of local taxes they (should) pay for services, interactions with and perceptions of tax collectors and tax literacy were not available from the AmericasBarometer. Surveys could henceforth incorporate these key aspects, as well as the multiple actors involved in the financing of public goods (such as traditional authorities). The analysis presented here is based on individuals’ self-reported intentions to pay higher taxes in return for better services rather than actual tax behaviours; tax-related questions often suffer from social desirability bias, too. This article has focused specifically on the role of trust. Scholars working on remittances could furthermore examine the role of tax enforcement and facilitation in future research (Dom et al., 2022).

Qualitative accounts could also help shed further light on the claims advanced. Scholars might, for instance, wish to examine what a fair and inclusive fiscal contract means for remittance-receiving families, or how international emigration and remittances have redefined the latter's participation in local social contracts, including as regards expectations and norms. Ethnographic research could likewise be used in selected remittance-receiving communities to examine whether contact with local authorities or participation in decision-making processes and community-based tax schemes has helped cement or undermine the fiscal contract. This would help identify other pathways potentially informing the relationship between remittances and (conditional) tax compliance at the local level. Qualitative evidence could also be used to investigate whether municipal mayors in migrant communities face greater accountability pressures vis-à-vis how they spend tax revenues or whether they think they will not be re-elected in the event of corruption scandals.24 A local community-based perspective can thus offer a different view of the fiscal contract and add to our theoretical and empirical understanding of state–society relations in migrant-sending countries.

Another important limitation of this study is that it focuses on just one region. It would be fascinating to see how the links between remittance receipt and conditional tax compliance play out in other places around the globe, such as SSA and Asia. This study focuses only on the micro level; hence, future research is needed to explore how remittance inflows influence local tax capacity at the aggregate level (where relevant data are available). Analysing the micro- and macro-level dynamics of local taxation in migrant-sending countries represents a promising avenue for future research — one that deserves more scholarly attention beyond just LAC.25

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Irina Ciornei, Vanessa van den Boogaard, David Doyle, James Powell and Rose Shaber-Twedt for their generous comments and excellent suggestions on previous versions of this manuscript. Thanks are due also to Friedl Marincowitz and the anonymous referees of Development and Change for their comments and suggestions. The article benefited from feedback received during the MIGRADEMO Workshop at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (21‒22 November 2024); the MIGNEX Conference at Oxford University (25‒26 June 2024); the ISA Global South Caucus Conference (15‒18 December 2023); ‘The Public and Democracy in the Americas’ Conference (10 November 2023); the JUSTREMIT Workshop at the University of Leiden (12‒13 October 2023) and the IMISCOE Annual Conference (3‒6 July 2023). The article received support from the Governance and Local Development Institute Working Paper series. AmericasBarometer data were used and can be accessed at www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/. The author takes responsibility for all errors.

Biography

Ana Isabel López García ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Global Migration at Maastricht University, The Netherlands. Her work explores how connections with migrants abroad shape political and social attitudes in origin countries through remittances and return migration.

REFERENCES

- 1 That said, the aggregate-level relationship between remittance inflows and total tax revenue — measured as the tax-to-GDP ratio — is far from clear (Bangaké et al., 2024; Escribà-Folch et al., 2022). On the one hand, international emigration lowers labour supply: as more people become dependent on migrant remittances, the basis for income tax is reduced (Airola, 2008; Justino and Shemyakina, 2012; Rodríguez and Tiongson, 2001). On the other hand, migrant remittances smooth and increase purchasing power, thereby creating a larger base for consumption taxes (Asatryan et al., 2017; Ebeke, 2011).

- 2 The Cuban government, for instance, charges a tax of 20 per cent on every remittance transfer the country receives. In Haiti and Venezuela, similarly, the government collects a fee on every remittance transaction. Outside Latin America, taxes on remittance inflows have been imposed in Ethiopia, Ghana, Pakistan and the Philippines.

- 3 In various developing countries, fees feature more prominently than property taxes in the financing of local public goods and state governance functions. Furthermore, when individuals pay user fees, they can see in a more immediate way how they receive a particular service in return (van den Boogaard et al., 2019: 268). In Latin America and the Caribbean, property taxes are an important source of revenue for local governments (OECD, 2024).

- 4 I thank one of the reviewers for pointing this out.

- 5 On average, 18.9 per cent of fiscal revenues in LAC are collected at the state level and 7.6 per cent at the local level (OECD, 2024).

- 6 Direct and indirect taxes also elicit different reactions from citizens (Martin, 2023). Those who pay direct, for example property-related, taxes are more conscious of giving money to the government. In contrast, citizens can adjust over time to higher prices and indirect, for example consumption-related, taxes.

- 7 Local tax systems can, however, impose high burdens on low-income individuals through nuisance taxes (see Prichard and Dom, 2022).

- 8 In El Salvador and Mexico, migrant households are more likely to be courted through clientelistic tactics than others (Álvarez Mingote, 2019; Danielson, 2018; González-Ocantos et al., 2018). Yet, various studies show that remittance-receiving households are less likely to offer their electoral support in exchange for the delivery of goods and services, precisely because they can afford to buy and provide welfare themselves (Díaz-Cayeros et al., 2003; Pfutze, 2012). This is consistent with evidence from Africa, indicating that remittance recipients are more likely to oppose patronage and other types of electoral corruption (Dionne et al., 2014; Easton and Montinola, 2017; Escribà-Folch et al., 2022; Tyburski, 2012).

- 9 Van den Boogaard and Santoro (2023) also note that there is always the risk of state capture in informal community-based systems. This tends to occur when individuals are sidelined from the decision-making process. In Mexico, for instance, various reports indicate that the 3×1 Programme's resources are commonly diverted or misused for mayors’ private and electoral benefit. This includes municipal mayors inflating budgets, building infrastructure with low-quality materials, receiving kickbacks from contractors, being reluctant to disclose information about funding usage or using the funding for electoral purposes (Aparicio and Meseguer, 2012; Bada, 2016; Danielson, 2018; Duquette-Rury, 2019; Malone and Durden, 2018; Simpser et al., 2016; Waddell, 2015).

- 10 Tables and Figures referred to in the text as ‘S’ are included in the Supplementary Information online.

- 11 In the sample, willingness to pay higher municipal taxes and increased levels of trust in local authorities are positively correlated (p < 0.000). Trust is positively and significantly associated with levels of demand making on local officials (p < 0.000), attendance at town hall meetings (p < 0.000) and engagement in community-improvement activities (p < 0.000). These participation measures are, in turn, strongly and significantly related to each other (see Table S3).

- 12 Since household income is measured differently by the LAPOP survey across countries and waves, I use a wealth measure based on self-reported ownership of certain goods instead. While questions on banking and property ownership might also be relevant here, they were only included in LAPOP waves from 2018 onwards, which unfortunately still do not include questions on conditional tax compliance. Therefore, these items are not included in the analysis or accounted for in the ‘entropy balancing’.

- 13 Mexico is taken as the reference category in the models.

- 14 With complex survey data, ‘goodness-of-fit’ measures like LR Chi2, BIC0 and AIC cannot be used as observations are non-independent. Hence, F-statistics are reported instead in the models.

- 15 The variable measuring trust in national authorities (b14) was only available for two countries (Colombia and Guatemala) in the 2012–16 AmericasBarometer rounds, asking citizens about their willingness to pay higher taxes in exchange for better public education and healthcare services. Therefore, trust in the president/prime minister is used as a proxy for trust in national authorities (b21a).

- 16 More specifically, when individuals request assistance from a local official, the marginal effect is 6.38 percentage points for remittance recipients, compared to 2 percentage points for non-recipients. Likewise, when help is sought at a municipal office, the marginal effect is 3.27 percentage points for recipients but −1.75 percentage points for non-recipients.