Green Energy and State Power: The Case of Zhanatas Wind Power Project in Kazakhstan

My biggest thanks go to my interviewees in southern Kazakhstan who generously shared their insights and experiences with me. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers at Development and Change for their highly constructive feedback and suggestions. Professor Nikita Sud at the Oxford Department of International Development offered many helpful comments while I wrote and revised this work. The research was supported by the Sino-British Fellowship Trust, Oxford Department of International Development, and St Antony's College, University of Oxford.

ABSTRACT

In current debates, green energy is often presented as an opportunity for peripheral states and regions to take a lead in energy production and challenge their peripheral status. This article offers a counterview. It builds on qualitative fieldwork at the Zhanatas 100 MW Wind Power Plant in southern Kazakhstan — Central Asia's largest wind farm at the time of construction. On terrain considered by some to be ‘wasteland’, wind is captured, extracted and centralized as an emerging energy resource. At the same time, the nomadic population remain politically marginalized and the land and its many non-human inhabitants continue to be ecologically vulnerable. This article argues that the long-term effect can be described as changing state power within unchanging and unequal centre–periphery power relations. The article provides a theoretical contribution to the understanding of how green energy and state power can substantially reconstruct each other on the ground; it furthers our knowledge of the relationship between space and state under the conditions of energy transition, and advocates for a focus on spatial and historical inequalities in the context of changing energy production.

INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of green energy projects are being built in what is referred to as the ‘periphery’ or ‘terra nullius’ (Dunlap et al., 2024; Stock, 2023; Tornel, 2023). Rooted in world systems theory, where it refers to countries, the term ‘periphery’ can also be applied to peripheral regions within a state that are politically, economically and socially less developed and integrated (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Wallerstein, 1974). Where such peripheries exhibit characteristics including rich wind and solar resources, low population densities and a sense of ‘remoteness’ and ‘emptiness’, they are liable to be chosen by powerful centres as a space of experimentation for large-scale green energy1 projects (Dunlap et al., 2024; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009).

To date, scholars have recognized green energy as a unique development opportunity for both peripheral states and peripheral regions within a state.2 For instance, in the energy transition literature, scholars have illustrated how hinterland cities can leverage green energy production projects to create new energy spaces, stimulate infrastructure investment and foster economic growth (Lin and Wang, 2023). On a global scale, peripheral countries have the potential to lead in green energy production, thus altering their position within the global power hierarchy (Baptista, 2018; Hancock, 2015; Levin and Thomas, 2016). Locally, well-conceived solar and wind energy projects can also mitigate development disparities between different geographical regions within a state (Cebotari and Benedek, 2017; McEwan, 2017).

However, states and regions do not exist in a vacuum. Rather, their status as peripheral reflects not only their geographical remoteness from the powerful centre but also their marginalized political, economic and even ecological positions within both regional and global systems (Dunlap et al., 2024; Sovacool, 2021; Stock and Birkenholtz, 2021). In the Global South, particularly, the periphery is profoundly entrenched in a history marked by colonialism, imperialism, extraction and capitalism (Alff, 2016; Andreucci et al., 2023; Sud and Sánchez-Ancochea, 2022). It is thus important — especially in the context of energy transition — to consider state power not merely as the inherent attribute of the state, but through the lens of centre–periphery relations (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009). This raises two questions: (a) how can large-scale green energy projects reconstruct state power on the ground; and (b) to what extent does energy transition change centre–periphery relations, especially within a Southern context?

The Zhanatas 100 MW Wind Power Project (hereafter simply the Zhanatas project) is located in Zhanatas in the Zhambyl region in southern Kazakhstan. Completed in 2021, it was at the time Central Asia's largest wind farm, estimated to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by nearly 300,000 tons a year (AIIB, 2019b). It sits on what is described as a forgotten ‘wasteland’ on the Central Asian steppe. Two multilateral development banks were the main investors in the project, and a major Chinese electricity company operated it. It thus serves as a useful case study for both its volume and its unique political context.

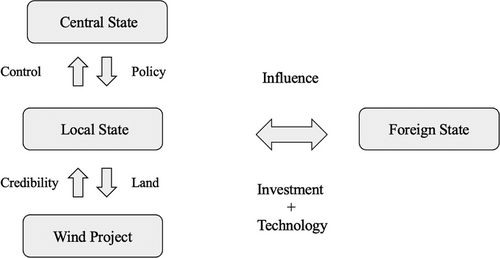

This article builds on qualitative fieldwork to interrogate the Zhanatas project. From March to June 2024, I conducted 46 semi-structured interviews, alongside participant observations and archival research, in Zhanatas. I argue that green energy and state power can substantially reconstruct each other on the ground. Through the large-scale wind energy project, three things occur: (a) the local state restores its authority and credibility; (b) the central state extends its spatial and political control; and (c) the foreign state projects its geopolitical and geo-economic influence.3 On the ‘wasteland’ of Zhanatas, while the wind is captured, extracted and centralized as an emerging energy resource, the population and many non-humans remain politically marginalized and ecologically vulnerable. This means that, while the form of production is changing, the unequal exchange relations of the centre–periphery remain unaltered. I therefore characterize the findings as changing state power within unchanged centre–periphery relations (see Figure 1).

Changing State Power in Unchanged Centre–Periphery Relations

Source: author's design

This article makes three significant contributions. First, it provides a theoretical input to critical development studies on local governance and green energy (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Lin and Wang, 2023), arguing that even in seemingly ‘empty’ places, green energy and state power(s) can substantially influence each other on the ground. Second, by emphasizing the spatial dimension of the energy transition, it conceptually furthers our knowledge of the relationship between space and state power under evolving conditions, thus addressing the political-ecology literature (Dunlap and Arce, 2022; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009). Third, it makes an empirical contribution to political-geographical studies of the on-the-ground effects of (green) development interventions (Avila et al., 2022; Stock, 2023; Tornel, 2023).

The Zhanatas project should be viewed as part of a broader global effort to address climate challenges. In the current energy system, while the form of energy production is evolving, unequal productive relations often persist (Alkhalili et al., 2023; Dunlap, 2017; Normann, 2021). In peripheral areas, these relations may be particularly deeply entrenched. For regions and states of the Global South, addressing these challenges is both difficult and potentially rewarding. This means that policy makers should focus not only on green energy production itself but also on the numerous ecological, political, economic and social implications it entails (Andreucci et al., 2023).

In the following section I discuss the role of green energy as a means for changing (or not) centre–periphery relations and state power, while the subsequent section describes my case selection, methods and analytical approach. I then examine the on-the-ground effects of the Zhanatas project, and discuss how it has substantially reconstructed existing state power(s). The article concludes with a summary of the main arguments, contributions and research recommendations.

GREEN ENERGY AND STATE POWER: BEYOND THE MACRO PICTURE

Centre–periphery relations have long been recognized as a core aspect of societal development. Throughout history, these relations have reinforced global inequalities, particularly between North and South, through processes of colonialism, imperialism, modernization and eventually capitalism (McKenzie, 1977; Wallerstein, 1974; Wellhofer, 1989). The centre, often characterized by rich states and advanced technologies, dominates economic and industrial production. In contrast, the periphery primarily supplies minerals, materials, products, labour and ultimately time and space, to sustain the centre's economic and technological dominance (Sud and Sánchez-Ancochea, 2022).4

The concept of centre–periphery relations, initially applied to the world system, has also been adapted to explain internal economic and political structures within states. Scholars have drawn parallels between international hierarchies and domestic inequalities, highlighting how internal economic development frameworks reproduce similar patterns of uneven development and internal colonialism (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979; Hechter and Agnew, 1999; Orridge, 1981). In general, this perspective suggests that relations within states mirror those in the international arena, where dominant metropolitan centres (such as central states) consolidate power, while peripheral regions (such as local states) remain economically and politically marginalized (Langan, 2017). In developing countries such as Kazakhstan, rural and non-urban local states often experience limited political access and socio-economic exclusion, reinforcing their peripheral status. Meanwhile, the central state — the prominent centre — enforces a unified national agenda and deepens these disparities.

In current debates, green energy is increasingly seen as offering a potential opportunity for peripheral states to alter their status within the hierarchy. This transformation is expected to occur through a combination of two mechanisms. First, recent scholarship in development studies and energy studies highlights how green energy can reshape state power on the ground (Hu, 2020; Liao and Agrawal, 2022; Lomax et al., 2023). These discussions focus on the state's material or actual power — its ability to control resources, levy taxes and implement policies to achieve developmental goals. By engaging in ‘green’, ‘clean’, ‘renewable’ and ‘sustainable’ energy projects, both central and local states can reconfigure governance structures, restore authority and stimulate economic growth (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Lin and Wang, 2023; Zeng, 2024).

Second, and more profoundly, green energy is considered a mechanism for reshaping state power within historically entrenched centre–periphery relations. Political-geography literature and policy discussions on energy transition — such as Conferences of the Parties, commonly known as COPs — suggest that large-scale solar and wind energy projects in peripheral regions present an opportunity to bypass or ‘leapfrog’ reliance on coal-based energy and adopt modern renewable energy technologies (Clark and Isherwood, 2010; Levin and Thomas, 2016). Consequently, green energy could help reduce long-standing historical centre–periphery inequalities, both within individual nation states and in the global system (Baptista, 2018; Hancock, 2015; McEwan, 2017). This perspective shifts the focus to a more abstract understanding of state power, which refers to a state's relative authority within the broader political system (Dunlap and Arce, 2022; Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009).

However, critical development studies and political-ecology research present a contrasting perspective, suggesting that green energy does not necessarily alter a state's peripheral status and may even result in practices such as ‘green extractivism’ or ‘green grabbing’ (Dunlap et al., 2024; Siamanta, 2019; Tornel, 2023; Ulloa, 2023). ‘Extractivism’ was originally conceptualized as the appropriation of material resources, primarily oil and minerals (Gudynas, 2021). As capitalist-driven modernist development and wealth accumulation intensified, the definition expanded to encompass a broader range of activities, including ‘farming, forestry, and even fishing’ (Acosta, 2013). In its crudest form, extractivism represents ‘a style of development based on the appropriation of Nature’ (Gudynas, quoted in Dunlap et al., 2024: 439). As states and state-led companies enter the ‘green finance’ and ‘energy transition’ spaces, and as more and more extractive projects are being branded ‘green’, ‘clean’, ‘environmental’ and ‘sustainable’, studies on extractivism extend to ‘solar extractivism’, ‘wind extractivism’ and ‘hydrological extractivism’ (Avila et al., 2022; Dunlap, 2018; Dunlap and Arce, 2022; Tornel, 2023; Ulloa, 2023; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009). For many, ‘green extractivism’ thus refers to a system of extractive development that harnesses climate change as profit-making opportunities (Andreucci et al., 2023; Dunlap et al., 2024; Gudynas, 2021). In short, while green energy might have the potential to reduce centre–periphery inequalities, it might also do the opposite.

Within the context of wind energy, centre–periphery dynamics often remain unchanged. For instance, examining conflicts over wind farms in rural Catalonia, Zografos and Martínez-Alier (2009) argue that wind energy perpetuates the traditional centre–periphery conflict. In many cases, these conflicts become ‘ecologized’ as wind farms benefit central regions while causing landscape degradation in peripheral areas (Banks and Schwartz, 2023; Fjellheim, 2023; Normann, 2021; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009). Similarly, Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein's (2023) investigation into the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project in northern Kenya challenges the optimistic assumptions surrounding green energy. They contend that while land in the region underwent a process of ‘centralisation’, the pastoralist inhabitants remained a ‘marginalised social periphery within the state’ (ibid.: 2). These findings underscore the view from political ecology and political geography that the so-called energy transition is not merely a geographical phenomenon but also a deeply historical process (Alkhalili et al., 2023; Allan et al., 2022; Avila, 2018; Avila et al., 2022; Stock, 2023).

Typically, for wind energy, both emerging and classic literature have highlighted the importance of examining the effects of wind farms on the ground, particularly in areas often labelled as ‘wasteland’ or ‘terra nullius’ (Dunlap, 2017, 2018; Dunlap and Arce, 2022; Fjellheim, 2023; Normann, 2021). Like other development projects, wind energy initiatives led by states or state-backed companies have long-term ecological, political, economic and social impacts on both human and non-human actors (Agrawal, 2005; Ferguson, 1990; Ndi, 2024; Wade, 2009). Only by unpacking these impacts can one discern whether centre–periphery relations have changed or remain static (Sovacool, 2021). It is, therefore, essential to approach the topics of ‘green energy’ and ‘state power’ by moving beyond macro-level analyses and engaging with the nuanced dynamics on the ground.

METHODOLOGY

Case Selection and Contextualization

The literature underscores the critical role of subnational (local) states in both land politics and the politics of green energy. Subnational states are seen as pivotal in the global capitalist economy and serve as a key to understanding the evolving nature of state power (Ndi, 2024; Sud, 2014). Central states, especially coastal and more developed states, might effectively leverage the energy transition to advance their developmental objectives (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Liao et al., 2021). In contrast, local states often face significant challenges, in which local leaders grapple with issues related to authority, credibility and accountability.

Zhanatas, which means ‘newly found rocks’ in Kazakh,5 is the administrative centre of an industrial area in southern Kazakhstan's Zhambyl Region (Figure 2). Sitting on the north of the Karatau slopes, the Soviet-style town has a population of around 24,000 (Open Democracy, 2021) and is surrounded by rocky hills. The Zhanatas population relies for its livelihood mainly on two things: traditional pasturing economies, and predatory-style phosphorate-extractive industries. Many see Zhanatas as characterized by ‘geographical remoteness’ and ‘social backwardness’, or as some say, ‘wasteland’.6

Map of Kazakhstan, Showing the Location of Zhanatas [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The pin on the map represents the location of Zhanatas Source: The World Factbook, Kazakhstan (www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/kazakhstan/map/)

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Zhanatas experienced severe poverty, unemployment and disease. Between 1996 and 1999, a major famine resulted in significant mortality. Cats and dogs reportedly disappeared from the streets because they were the ‘only affordable source of meat’ (OpenDemocracy, 2021). The area also endured an outbreak of tuberculosis lasting until 2007, with lingering health impacts. According to the Republic of Kazakhstan's Ministry of National Economy, Zhambyl Region was the poorest state in the country in 2015, with a poverty rate of 36 per cent (see World Bank Group, 2018a). This poverty is closely linked to high unemployment rates, with nearly half of the jobs in Zhambyl and neighbouring South Kazakhstan Region being classified as unproductive self-employment (see Table 1). Additionally, educational attainment is markedly lower in these areas; for instance, while over 90 per cent of youth in Astana and Almaty undertake some level of higher education, less than 50 per cent achieve this in Zhambyl and South Kazakhstan (OECD, 2017; World Bank Group, 2018a). Media reports also point out that Zhanatas has well-documented disparities, conflicts and uprisings, reflecting the local state's rapidly declining authority and credibility (Open Democracy, 2021).

However, this situation changed in the latter part of the 2010s, with the construction of the Zhanatas 100 MW Wind Power Plant. Located on a steppe 10 km away from Zhanatas town, the power plant was Central Asia's largest wind farm at the time (AIIB, 2019b). Once completed, it was expected to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by nearly 300,000 tons a year and to power one million households in Kazakhstan with green electricity (Xinhua, 2021). The ultimate goal behind the project, according to the investors, was to deliver ‘clean electricity generation of approximately 319 GWh per annum and contribute to the renewable energy development in Kazakhstan’ (Company X, 2021). Meanwhile, it would also ‘greatly alleviate the power shortage in southern Kazakhstan’ (ibid.). The design phase for the power plant began in 2015.

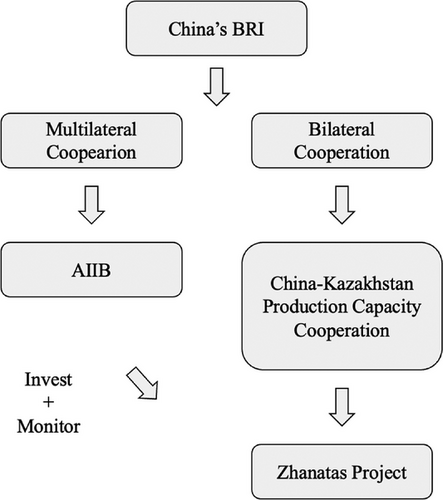

However, the project to ‘capture the wind’ in Zhanatas should be seen as an international effort. In 2013, China announced the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its massive infrastructure and development project (BRI Portal, 2024; Council on Foreign Relations, 2023). The aim of the BRI was to improve connectivity and cooperation between East Asia and Europe through physical infrastructure. In the following decade, the project expanded to Africa, Latin America and Oceania, representing ‘an unsettling extension of China's rising power’ (Council on Foreign Relations, 2023). According to the World Bank, by 2018 the BRI included countries and regions that account for more than one-third of world trade and global GDP, and over 60 per cent of the world's population (World Bank Group, 2018b).

China's BRI manifests both as a multilateral framework and a set of bilateral engagements. It has spurred the creation of various multilateral partnerships, investment funds and development banks, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), to promote financing and development across participating countries. At the bilateral level, the BRI operates through China's direct agreements with individual countries, tailored to meet their specific development needs. These agreements often include the construction of critical infrastructure projects such as roads, railways, ports and energy systems. In practice, the BRI's multilateral and bilateral components often complement each other to enhance the initiative's overall impact. The Zhanatas Wind Power Plant was added to the BRI ‘basket’ in 2016, and was developed within this broader context (see Figure 3). In 2018, legal documents were signed; construction began in 2019 and was completed in 2021.

The Zhanatas Project under China's BRI

Source: author's design

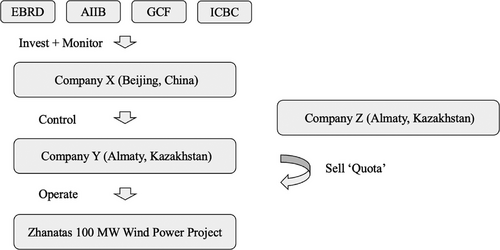

Figure 4 illustrates the network of relations behind the Zhanatas Wind Power Plant. While the main investor is AIIB, it is owned by a China-backed company registered in Almaty, Kazakhstan (referred to here as Company Y), which holds 80 per cent, and a major Kazakh energy company (referred to here as Company Z), which holds 20 per cent (AIIB, 2019b). Company Y and its Chinese parent company, X Group, one of the largest power utility conglomerates in the world, borrowed the money from four institutions: (a) the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD); (b) AIIB; (c) Green Climate Fund (GCF), the world's largest climate fund; and (d) the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the largest bank in the world (GCF, 2017). I would argue that, as a result, Zhanatas emerges not merely as a geographical location in which a large-scale energy transition project has been built: it can also be seen as: (a) a geostrategic region in which a rising power aims to project its influence; (b) a political territory where the state seeks to extend its power and control; (c) a social and economic domain in which local authorities need to restore their accountability and credibility; and (d) an ecological and cultural landscape within which extractive and colonial activities are ongoing (Dorian et al., 1997; Skalamera, 2020).

Relations behind the Zhanatas Project

Source: author's design

Research Methods

In this research I followed inductive principles, building insights from the ground up. I adopted mixed qualitative methods, including semi-structured interviews, focus groups, participatory observations and archival research. Together, these methods allowed me to look not only at the macro-level picture regarding networks that enable the extractive activities, but also at the many, complex and changing local dynamics within and around this specific wind power project (Dunlap and Arce, 2022).

I conducted qualitative fieldwork in Kazakhstan from March to June 2024. My research locations included the Zhanatas project site (10 km away from Zhanatas town), the Zhanatas National Grid Substation (5 km from Zhanatas town), Zhanatas town itself, Sdykbayuly village and several pasture farms further away from the project. I also spent time in Shymkent, Kazakhstan's third-biggest city, and Almaty, arguably Kazakhstan's cultural, economic and academic centre, where I worked temporarily as a visiting researcher at a university. Towards the end of my fieldwork, in late May and early June, the project investors and managers gave their approval for me to stay within the wind farm, during which time I observed and analysed how the wind farm actually captured, extracted and transformed the otherwise ‘damaging’ wind (Dunlap et al., 2024).

I conducted 46 semi-structured interviews in total. My participants included 19 project-affected locals, 12 project-related staff, nine local-level and regional-level officials, two NGOs and four academics (see Table 2 and Appendix Table A1). I approached these participants through snowball sampling and selected them for their relevance to the project or research questions. To capture subtle nuances in attitudes and ensure free conversations, I combined formal interviews with informal discussions; I often began dialogues with some fixed questions and then turned to conversation-style everyday exchanges. This strategy proved to be effective especially when talking to the marginalized communities and individuals, who are usually nomads (Gorayeb et al., 2024; Ndi, 2024). The data used in this article were thus gathered through interviews and publicly available documents. I obtained oral or written consent for each interview, and anonymized the names of participants, using labels such as ‘YH’ and brands such as ‘Company X’ as pseudonyms.

THE ON-THE-GROUND EFFECTS OF THE ZHANATAS WIND POWER PLANT

In Zhanatas, while the idea of capturing the wind may seem quite abstract, the effects of extractive practices are visible on the ground. These dynamics are particularly noteworthy given that the nomadic communities in Zhanatas have traditionally intertwined their identities and livelihoods with the wind, land and landscape.

People

It has been suggested that wind farms are by nature ‘floating’ (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023), meaning that they generate green energy while occupying only a limited amount of land, compared to conventional energy and solar energy. Land in Kazakhstan is state-owned; since the collapse of collective farms during the Soviet era, locals have rented land from the state at low prices for pasturing (Cameron, 2018; EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019). According to publicly available documents, seven farmers affected by land acquisition in the context of the Zhanatas project signed agreements with the local district council to relinquish ‘small parts’ of the state-leased land without economic compensation (AIIB, 2019a). There have also been two consultation meetings with six households whose land was directly affected by the construction of the project. Leaving aside the ‘regional council website’, to which local households have no access, there is no regular channel through which they could express their concerns.

Compared with other energy projects, such as coal projects, or even solar projects, one of our leverages is that we don't take much land. What we take are ‘points’ of land. Points, not areas. And not from the locals directly, but from the state. Plus, there is no such sense that ‘we take something away’ from the land. Indeed, we take wind, but the wind is invisible. What would you do with it otherwise?7

Official documents evaluating the project support NM's view. According to the Zhanatas Wind Power Plant Environmental and Social Analysis report, ‘the impact on the tenants of the land, small parts of which have been acquired for the wind farm components, is thought to be low’ (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019: 34). Regarding other impacts on local pastoralists, the report also states that ‘visual impact on the Peishbek farm is considered to be low and on the others, as insignificant’ (ibid.: 3).

However, the everyday experiences of several nomads I met in and around the large-scale project strongly challenge these assumptions. KB, a middle-aged local Kazakh whom I met within the wind farm while he was grazing his sheep and horses, expressed the following more nuanced view: ‘Come closer and stay for a while, you'll get tired of these columns [turbines]. Not to mention the sound. It is annoying. … Rumour has it in my village that these columns are not good for human health if you think about their long-term consequences. I do not know, perhaps’.8 Standing outside the wind farm, one can see more than 30 150-meter-tall turbines with 50-meter-long blades working on the steppe. The turbines are planted around 500 meters apart, in five groups. Even at the edge of Zhanatas town, which is 10 km away from the actual wind farm site, I managed to see the tips of several working turbines. Besides the obvious visual impact of the turbines, the noise involved appears to be another major concern. Of the 19 project-affected locals interviewed, 15 of them expressed concern about the constant noise that accompanies the Zhanatas project's construction and operation.

Another dimension of the project is the effect it has on ‘people as a community’. Zhanatas town currently has approximately 24,000 residents, less than half its population in the 1980s (Open Democracy, 2021). Despite this reduction, the town continues to struggle with insufficient employment opportunities. The remaining two factories — a Kazakh phosphate factory and a Russian-operated chemical factory — employ around 2,000 people, while others work in local service industries or remain unemployed (OpenDemocracy, 2021; Zhambyl Region Government, 2024). In 2018–19, when the regional government announced plans to build the largest wind farm in Central Asia, the community experienced a mix of emotions. On the one hand, residents hoped that the new ‘green factory’ would create jobs and opportunities, improving their challenging living conditions. On the other hand, they were apprehensive about engaging with Chinese companies for the first time and were deeply concerned about the project's potential environmental and political impacts.9

I understand how hard it was for both sides. For the Company [Y], it is a profit-making firm with strict security requirements. There is no way that it hires people it doesn't necessarily need. For the workers and pastoralists, their disappointments and fights are also understandable. I mean, if you consider how much they have been ripped off by people who entered the town in the past century. Or, past centuries, if I may remind you.11

This sentiment underscores the recurring clashes between two distinct economic systems: pastoralist economies and state-led modern economies. For the pastoralist population, Zhanatas has long served as a home where they pursue their livelihoods and build social networks. The state, however, views Zhanatas differently, often perceiving local pastoralists as elusive due to their mobility, communal land use and resistance to formal systems of control such as taxation or property ownership (Chatty, 2010; Kapila, 2008; Maru et al., 2022; Scoones, 2023). Local officials, similarly, view the pastoralist population as ‘hard to manage’, ‘far-away’ and ‘small’.12 In addition, as mentioned in the previous section, the state has struggled to establish its authority in pastoralist regions since the 1960s. Observations suggest that this invisible conflict has persisted, as wind — a resource now appropriated under the framework of modernization — gains economic value (Siamanta, 2019; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009).

Land

Unlike wind, which is invisible and for which NM (quoted above) could see no other use, land in green energy projects is more tangible and concrete. In a region such as Zhanatas, land is primarily understood as a physical property with economic value. For the local state, land represents one of its few points of leverage for attracting foreign investors.

Viewing land as, first and foremost, a physical property, my findings in Zhanatas echo the literature on global land deals, which has revealed how dominant powers and private capital often downplay the value of land to facilitate profit-driven production (Andreucci et al., 2023; Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Sud, 2020). The peripheral status of nomadic populations in Zhanatas has enabled authorities to manage land in a way that is convenient for the local state. First, no official ownership over the land has been claimed since the collapse of the Soviet Union; if there is any ownership, the land belongs to the state. Second, land is perceived to have limited economic value. Even when renting land from the state, local nomads only assert their rights over a broad but vague area of land, and use only its surface for agricultural and pasturing activities (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019). Third, temporary landholders — like the seven nomads mentioned above, who live around the Zhanatas project — have limited political and social access to opportunities for voicing their opinions regarding land deals. Under these conditions, the local state perceives land in Zhanatas as effectively available to be exchanged for foreign technologies and investments. The aforementioned environmental and social impact report claims: ‘They [farmers] have no attachment to the rented plots and giving up parts of the rented land on several occasions … has not deprived them of any access to the pastureland that is available in abundance’ (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019: 25).

TB: The windmill indeed does not affect my horses. Surprisingly, my horses seem to enjoy the shadows created by the huge windmill.

Author: I saw some of them. Indeed. Impressive.

TB: However, the windmill affects two [other] types of livestock. The first is the newborn. They are usually too weak to go across the roads. There are gaps on both sides of the roads if you take a look. I mean, they will go across them with help from their mothers, but it takes a longer time. The second is the sheep. They do not like the sound made by the windmill and are unwilling to go under it.

Author: Have you talked to anyone about this problem?

TB: Not my land now. I do not think it'll work.

(Minutes later)

TB: The government is on their [Company Y's] side. We are on this side [making gesture].13

Land, however, is not merely physical property with economic value. In Zhanatas, as in many other peripheral regions, land embodies significant social and political meanings that shape the identities of nomadic populations. For those communities that maintain a traditional lifestyle on the steppe, marginalized and distanced from processes of urbanization, land constitutes a vital part of the broader landscape that ‘produces’ people. My comprehension of the social and political meanings attributed to the landscape in southern Kazakhstan derives from interviews conducted with nomads between April and June 2024 in Zhanatas, Shymkent and subsequently in Almaty. First, from a historical-geographical perspective, the steppes in southern Kazakhstan are crucial to community-centred pastoralism and interethnic relations. The expansive, resource-rich plains foster an identity characterized by self-sufficiency, independence and freedom (Cameron, 2018; Sinor, 1990). In particular, around the Karatau Slopes, where the terrain is more mountainous, the landscape historically contributes to a sense of resilience and what James C. Scott described as ‘resistance’ (Scott, 2009). Second, from a social and political perspective, the landscape in Zhanatas, as in other parts of southern Kazakhstan, has facilitated a highly decentralized governance structure and a historically diverse ethnic composition. These features were largely preserved even during the Soviet era. Consequently, local authorities wield significant power, influencing regional autonomy and resource control (Khamitov et al., 2023). Third, the landscape sustains a nomadic culture in which rituals, folklore and art are transmitted from generation to generation. Crucially, what is also passed down is a mobile lifestyle adaptable to the unpredictable, changing and often harsh environment. GC, a local contact who worked for an environmental NGO that also looked into the Zhanatas case, stated: ‘I am not an expert in wind energy, but I'll encourage you to think about not just what happened underneath the device [wind blades]. Try this, to think about what happened outside the wind farm and outside the “sites”’.14

Together, these different components provide a novel perspective on wind energy, highlighting an important distinction often overlooked in the literature on global land grabs. While economic and political consequences, and long-term social, ecological and geographical effects, have been broadly discussed, the specific implications of wind energy remain underexplored. Contrary to the common belief that wind energy requires less land and thus results in less dispossession (Ndi, 2024; Wang and Wang, 2015), the case of Zhanatas demonstrates otherwise: the ‘floating’ nature of wind energy facilitates more subtle and intangible forms of dispossession, making land grabs easier for authorities and more detrimental to marginalized communities. Wind energy takes land, while changing not only the existing and potential economic value of the land, but also the landscape, in which the land is physically located, and the social, political and cultural meanings of the land. Furthermore, wind energy impacts on a space that transcends land, because land is confined to the ground, whereas wind energy affects the space above the ground and in the air.

Non-humans on the Land

As one of the leading green energy initiatives in Central Asia, the Zhanatas project was developed and implemented with what its investors claimed to be a sophisticated environmental risk monitoring and mitigation strategy. Between April and November 2019, EcoSocio Analysts LLC conducted a third-party environmental and social assessment (ESA) and concluded that the project did not present any critical environmental and social issues, categorizing it as a mid-level risk with impacts judged to be site-specific or short-term in nature. To date, this 55-page ESA report (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019), which included two 2-day environmental assessments, remains the only comprehensive evaluation of the project's environmental effects, providing a detailed account of the environmental, social and legal conditions at the project site. However, it failed to consider the project's long-term impacts.

In Zhanatas, as in many other wind energy projects, construction and operational activities significantly affect birds. The ESA report describes the impact on birds as minimal: ‘Both bird and mammal diversity and numbers are low at the WPP [Wind Power Project] territory during migration and breeding and are expected to be low during winter too. … Observation of their flight from a vantage point suggested low risk to these birds’ (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019: 19, 21). However, this assessment does not fully reflect the reality. According to archival data and consultant statements, over 75 species of waterfowl have been observed in the region, including the great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus), pygmy cormorant (Phalacrocorax pygmaeus), black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), great egret (Egretta alba), common shelduck (Tadorna tadorna) and grey heron (Ardea cinerea). More significantly, endangered bird species such as the white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus), common crane (Grus grus), Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus) and demoiselle crane (Anthropoides virgo) have been recorded within the wind farm's range.15 MY, a Kazakh technician responsible for monitoring and examining the operation of the project, told me: ‘I see the dead bodies of birds from time to time. Dead bodies are usually found under the turbines, and they are the dead bodies of small birds. … Even if [they] are not physically affected, [their] migration can be misguided’.16 Noting that he had also found dead birds under the wind turbines, TB confirmed MY's statement: ‘Birds are definitely affected. It does not matter how big or small [the birds] are. The real issue, in my opinion, is how much you [people] value the species. Sometimes I see dead birds and dead snakes under the device, and I feel sad. I feel sad not because of how many have died, but how many will continue to die’.17

In addition to the birds, the impact on other non-human elements, specifically the soil and vegetation, has been significant. During construction activities, the destruction of soil and vegetation occurred over an area of approximately 0.7 to 1.2 hectares surrounding the foundation, crane pad and storage and assembly zones of each turbine. The estimated loss of topsoil and vegetation encompasses 67.7 hectares. This includes 11.7 hectares beneath the road infrastructure (26 km x 4.5 m), 48 hectares under the wind turbines (1.2 hectares x 40 turbines), and 8 hectares allocated to the substation, concrete plant and storage areas (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019). Although the impacted areas are relatively small, recovery and regrowth of surficial vegetation are projected to take approximately eight years (ibid.). Furthermore, vehicular traffic taking indiscriminate shortcuts between turbines and main roads has resulted in substantial damage to vegetation. This damage is expected to persist throughout the operational phase because these shortcuts are likely to remain in use, reducing the potential for vegetation recovery.

CAPTURING THE WIND, ASSERTING THE POWER

According to Ferguson (1990: 256), ‘A development project may well serve power, but in a different way than any of the “powerful” actors imagined; it may only wind up, in the end, “turning out” to serve power’. In Zhanatas, green energy reshapes state power. Here, the concept of the ‘state’ is not a monolithic entity but rather operates at three distinct levels: subnational (local), national and international. Similarly, ‘state power’ should not be understood as simply administrative or bureaucratic authority. Echoing Ferguson (1990) and Agrawal (2005), it also includes the goals the state pursues and the way in which power is exercised. The dynamic interplay results in changing state power in unchanged centre–periphery relations.

Restoring a Local State (Zhanatas)

When the wind project was initially proposed, the local state had little to offer except land. Coupled with the wind that blows over it, the land became the state's leverage. To attract foreign investments and green technologies crucial for transformative progress, the local state willingly appropriated and separated 233.5 hectares of land from its State Reserve land (EcoSocio Analysts LLC, 2019). Additionally, it took responsibility for preparing the land by reclaiming it from seven farms. This effort has proven to be rewarding.

The project generates positive effects, especially for the local state. First, it brings significant stable income to the state in the form of tax: since 2021, Company Y has become the third-largest taxpayer in Zhanatas. For the local authorities, Company Y represents ‘free tax’, ‘clean tax’ and ‘constant tax’.18 This tax income appears to be critical for the local state of Zhanatas, given the town's past economic vulnerability (see above). Second, the project introduced jobs. At the peak of its construction, it provided over 500 positions for local workers. As part of its ongoing operation, it involves a number of long-term, stable jobs which are considered unique and which enable workers to acquire ‘green skills’ that might be just as valuable as their incomes (Company X, 2021). Third, Chinese Company Y contributed significantly to local infrastructure and made a number of donations (see Table 3). In 2019, Company Y donated an urgently needed ambulance worth approximately US$ 15,820 to the local public hospital. In 2020, it invested US$ 37,800 in public repairs of Linden Park and donated US$ 67,130 to provide supplies and repair houses for impoverished families (Company X, 2021).

| Region | Population 2014 (million) | Poverty Rate 2015 (US$ 5/day) (%) |

Self-employment, 2016 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almaty | 2.0 | 11.8 | 27.1 |

| Zhambyl | 1.1 | 36.0 | 44.7 |

| Atyrau | 0.6 | 11.1 | 10.2 |

| Aktobe | 0.8 | 24.3 | 18.5 |

| Karaganda | 1.4 | 18.6 | 9.5 |

| Astana City | 0.8 | 7.9 | 5.1 |

- Source: World Bank Group (2018a)

| Type | Number | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Project-affected locals | 19 | Semi-structured, including informal conversations; translators were used in interviews with Kazakh and Russian-language speakers |

| Project managers and Project operators | 12 | Semi-structured |

| Officials | 9 | Semi-structured, including some ‘off the record’ |

| NGOs | 2 | Semi-structured; online |

| Academics | 4 | Semi-structured; mostly in English |

| Total | 46 |

- Source: author's fieldwork

| Year |

Amount (in US$) |

Contributions of Company Y |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 15,820 | Donated an ambulance to the local public hospital |

| 2020 | 51,310 | Donation to help disabled women and children repair homes |

| 2020 | 15,820 | Donated goods and repair funds to many poor families |

| 2020 | 37,800 | Invested in the maintenance of the town park |

| 2021 | 37,200 | Helped complete swimming pool renovation project in Abuacla |

| 2021 | N/A | Received a thank-you letter from the mayor of Nantat for social and economic contributions to the Nantat Wind Power Project |

- Source: Company X (2021)

A beautiful swimming pool, isn't it? Used to be abandoned but the Chinese invested a lot of money to rebuild it in 2021. Around 260,000 RMB [US$ 37,200] I think. People come here after dinner, to drink beer and wine and to swim. We enjoy our partnership with the project. They [the Chinese] help us to finish what we did not finish.19

While the way that the local state of Zhanatas leveraged the project to re-establish its fragile authority and credibility over historically resistant populations is noteworthy, the theoretical implications of these observations extend far beyond this specific case. In many other peripheral regions similar to Zhanatas, ‘failing states’ have been able to extract abundant financial and political resources from green energy projects (Karatayev and Clarke, 2016; Lin and Wang, 2023). However, there is no guarantee that these resources will be utilized for the benefit of the local, project-affected populations. Instead, these resources can be diverted to target other social groups in different locations, thereby playing a role in the restoration, reconstruction and consolidation of state power on the ground. More often than not, green energy will be produced in one location and consumed in another, underscoring spatial inequalities (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Zografos and Martínez-Alier, 2009). Prioritizing state objectives over peripheral communities’ needs epitomizes an abstract yet profoundly unequal political dynamic (Avila, 2018; Tornel, 2023; Ulloa, 2023).

The New Frontiers of the Central State (Kazakhstan)

While ‘green’ initiatives are implemented at a practical level, they also represent, at a more theoretical level, what development anthropologists call a ‘point of entry’ for the dominant power of the central state to exercise its political authority and extend its spatial control (Achiba, 2019; Ferguson, 1990). The ‘green’ label justifies the state's expansionist intentions and ‘greenwashes’ its predatory behaviour (Dunlap et al., 2024; Sovacool, 2021; Stock and Birkenholtz, 2021).

First, the central state extends its resource control by incorporating (in this case) wind energy into its territory. Despite relatively low energy prices and abundant energy resources, energy poverty remains a serious concern in Kazakhstan due to income inequality, high demand and inefficient housing construction (OECD, 2017). A study surveying 12,000 households found that 28 per cent of households in Kazakhstan were energy-poor, with about one-fifth of the rural population lacking access to clean fuel for heating (World Bank Group, 2018a). It is anticipated that the Zhanatas wind power plant will contribute significantly to solving these problems. Furthermore, using Zhanatas as its flagship project, the state has demonstrated its capacity to access and control wind energy alongside oil, gas and rare minerals. This project showcases the state's ability to manage not only the resource itself but also the associated technologies, investments and infrastructure, thus reinforcing its broader objectives of technological and infrastructural governance. At the same time, people remain marginalized and dissatisfied on the ground. In this sense, the wind project has failed to reduce power asymmetries in southern Kazakhstan. Indeed, it has been enhancing them in their crudest form.

Second, state power extends into an additional space in southern Kazakhstan. Seeing wind, which would otherwise be abstract, as a ‘new frontier’, the exercising of state power over wind energy in southern Kazakhstan and the rise of wind energy within the central state's energy system represent a strategic move in resource control. This shift has increased the state's influence over the people, places and institutions in Zhanatas. As noted in the Introduction, during the Soviet era, Kazakhstan's southern regions, including Zhambyl (formerly known as Dzhambul), were marginalized in comparison to the industrialized northern and central regions, leading to various instances of political resistance and unrest. A notable example occurred in December 1986, when protests erupted in Almaty after the Soviet leadership replaced Dinmukhamed Kunayev, the ethnic Kazakh leader of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, with Gennady Kolbin, an ethnic Russian with no ties to Kazakhstan. While this decision severely affected Kazakh identity, it garnered significant sympathy and support from southern regions, including Zhambyl, underscoring the regional disparities and deep-seated frustrations among southern Kazakhs towards the abstract ‘centre’ (Alff, 2016; Cameron, 2018). Following Kazakhstan's independence in 1991, the central government in Astana also faced challenges in integrating the diverse regions of the newly independent state. In this sense, control over wind goes beyond resource control and becomes control over space. Many people share this sentiment. OM, a local technician working for the wind farm, described his feelings as follows: ‘The wind energy project attracts attention. Zhanatas used to be just the middle of nowhere. But nowadays, it seems like an oasis in southern Kazakhstan. So many leaders have visited here to learn. I know it is a tough place, but you [outsiders] will come [laughs]’.20

Third, through the Zhanatas project, the central state also invigorates its green energy agenda. This illuminates the temporal aspect of state power. Politically, states have managed historical narratives that align with their identities and strategic goals, while economically, they have engaged in long-term planning to optimize infrastructure and resource development. The Zhanatas project exemplifies this approach by contributing to Kazakhstan's Concept for Transition to a Green Economy, which set targets to increase the share of renewable energy to 3 per cent by 2020, 10 per cent by 2030, and 50 per cent by 2050 (World Bank Group, 2018a). This initiative also aligns with Kazakhstan's Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement, which commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 15 per cent (unconditional) and 25 per cent (conditional) by 2030, relative to 1990 levels (China Daily, 2024). In addition to these ambitious targets, the central state emphasizes international collaboration, seeking partnerships with global organizations to advance green energy initiatives and adopt best practices.

On the ground, Zhanatas appears like an isolated ‘oasis’, as OM put it, within Kazakhstan's vast but peripheral zones, deeply rooted in the central state's historical landscape. However, within the central state's green discourse, Zhanatas emerges as a pivotal nexus, a bridge between the country's extractivist past and its envisioned green future. The Zhanatas project now symbolizes the state's transition from a history of resource extraction to a progressive green energy agenda. By integrating Zhanatas into its renewable energy strategy, the central state not only addresses its environmental ambitions but also recontextualizes its developmental trajectory within the broader narrative of ‘greening Kazakhstan’.

Foreign States’ ‘Global Power Shopping’ (China)

The Zhanatas project also exemplifies how global power dynamics narrow down in specific local states, which might otherwise remain peripheral to the whole concept of ‘global governance’. Launched in 2013, the BRI is a strategic framework developed by the People's Republic of China to enhance connectivity across Asia, Africa and Europe through extensive land and maritime networks, aiming at regional integration, increased trade and economic growth. In 2014, Kazakhstan became the first nation to enter a BRI ‘production capacity cooperation’ agreement, which established a US$ 2 billion bilateral fund to bolster Kazakhstan's industrial development, job creation and local growth (State Council of PRC, 2023). By the end of 2022, this partnership had significantly advanced renewable energy projects, with the installed capacity from Chinese enterprises in Kazakhstan surpassing 1,000 MW (China Daily, 2024).

In the past, Kazakhstan had to rely on feed-in tariffs to support green energy: since 2018, however, the country has transitioned to using ‘auction mechanisms’ to establish tariffs for green energy projects. Between 2018 and 2021, Kazakhstan conducted auctions resulting in the allocation of over 1,700 MW of green energy capacity, culminating in the development of 75 projects (IEA, 2024). Auction-based power purchase agreements facilitate the sale of all generated power to a designated centralized buyer of green energy. The Kazakh Company Z, shown in Figure 4, was a domestic company that first ‘bought’ the Zhanatas project in the auction and then ‘sold’ it to the Chinese Company Y and its parent Company X. Different levels of the Kazakh state have facilitated the ‘trade’ administratively and politically.

Given the domestic politics of Kazakhstan, it seems clear that, as a pivotal element of China's geostrategic BRI, the Zhanatas project illustrates China's broader strategy of global power expansion (Cao et al., 2016; Khamitov et al., 2023). While initially conceived as a climate action initiative under the influence of multilateralism, the Zhanatas project not only fulfils the nation state's goals but also serves China's strategic interests (Cai, 2018). Zhanatas forcefully extends China's influence deep into the Eurasian heartland (Ohle et al., 2020).21 Through my fieldwork and discussions with regional officials and academics, it became evident that Central Asia's largest wind power project goes beyond the role of a ‘geostrategic masterpiece’. More profoundly, it illustrates the abstract yet significant connection between the centre and periphery in the changing global order. Normally, within the nation state framework, there is a clear distinction between the periphery, where wind resources are extracted (in this case, the Zhanatas project site), and the centre, which enjoys the political (Astana), economic (Almaty) and financial (Zhambyl) benefits. Here, this contrast also mirrors the dynamics between Beijing and Central Asia.

Today, because both the central and local states in Kazakhstan have failed to protect their pastoralist populations, nomads are in the process of becoming mere objects in Beijing's geostrategic games. Similarly, the land and its ecological value are being subjected to the profit-driven motives of foreign entrepreneurs in the name of ‘green’ energy (Siamanta, 2019; Tornel, 2023; Ulloa, 2023). By contrast, the wind has emerged as a symbol of tax revenue, infrastructure development and economic growth. Wind's emerging value is now picked up, protected, quantified and traded between the two nation states. As the wind is captured, Beijing asserts its power over Eurasian land, reflecting an unequal ecological and geopolitical relationship between centre and periphery.

CONCLUSION

Shifting dynamics between state and space in the changing mosaic of energy production have become a subject of study. Taking the Zhanatas 100 MW Wind Power Plant in southern Kazakhstan as a case study, this article reveals novel evidence of how state power and green energy can reconstruct each other in the context of peripheral development. The dynamics and complexities discussed here can be characterized as changing state power within unchanged centre–periphery power relations.

Under the huge blades of the wind turbines, state power in Zhanatas is going through a series of changes. Notably, the local state in the periphery, created not by its geographical location but by its colonial and extractive histories, is on its way to restoring authority and credibility. The central state in Astana, meanwhile, extends its resource control over green energy and its spatial control over the historical ‘wasteland’ (Baka, 2013; Ndi, 2024). Geostrategically, the foreign state — China — also manages to project its influence into Central Asia's heartland via its state-owned enterprises and multilateral development banks, in the name of being ‘green’. This means that green energy and state power(s) can substantially reconstruct each other on the ground, even on a ‘wasteland’.

This restructuring is not without costs. While the wind is now separated, captured, extracted and utilized, the nomadic population continues to be politically marginalized, while the land and the living things on the land remain ecologically vulnerable. This means that, although the method of energy production is changing, the unequal nature of value exchange between centre and periphery remains unchanged (Andreucci et al., 2023). The theoretical assumption that green energy can provide an opportunity for the periphery is therefore striking. The Zhanatas case study presented here, together with critical development studies provided by Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein (2023), Zografos and Martínez-Alier (2009), Dunlap and Arce (2022), Tornel (2023) and others, reveal that green energy — such as solar and wind energy — is equally likely to consolidate the historically entrenched power relations between the centre and periphery.

Conceptually, this article advances the political-ecology literature on the dynamics of state power under the evolving conditions of wind energy. Unlike solar or geothermal energy, wind energy appears to have a ‘floating’ nature, since it can produce clean electricity on a limited amount of land (Hashimshony Yaffe and Segal-Klein, 2023; Wang and Wang, 2015). However, this ‘floating’ nature also allows the power shift around energy production to occur in a more abstract yet potentially damaging way. The political, social and ecological complexities of wind energy production need to be examined against the realities on the ground (Dunlap, 2017, 2018; Normann, 2021; Tornel, 2023).

In this sense, this article also makes an empirical contribution to the literature on the physical effects of development interventions labelled ‘green’. Using the Zhanatas project as a case in which state power goes through dynamic changes, it aligns with the works of Ferguson (1990), Agrawal (2005) and Wade (2009). Looking at ‘green’ development intervention from a critical perspective, it also resonates with Ndi (2024), Alkhalili et al. (2023) and Andreucci et al. (2023). The practical and theoretical implications of the Zhanatas case go beyond this single case study and are of relevance to policy makers within and beyond the Global South.

Two avenues for further study suggest themselves. First, wind has been providing power for human activities, such as sailing, aviation and agricultural production, since ancient times. Besides being a physical property, it also carries many changing social and political meanings. Explorations into how wind intertwines with human development, both generally, on a global scale (Dunlap, 2019; Dunlap and Arce, 2022; Siamanta, 2019), and specifically, in local and regional contexts (Bell et al., 2005; Gorayeb et al., 2024) are invaluable. Second, studying how the many changing and sometimes conflicting players facilitate China's export of green investments and technologies on the ground (Peyrouse, 2016; Shen and Power, 2017) will contribute to the prevailing narratives of China's grand strategy.

APPENDIX

| Type | Pseudonym | Location | Occupations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project-affected locals | CC | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Pastoralist farmer |

| KB | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Pastoralist farmer | |

| TB | Turkestan Village | Pastoralist farmer | |

| YM | Ushbas Village | Pastoralist farmer | |

| YP | Zhanatas town | Service industry | |

| MN | Zhanatas town | Driver | |

| MD | Zhanatas town | Private business | |

| Project managers and operators | NS | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician (Head) |

| MY | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project monitor (Head) | |

| LJ | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician | |

| DR | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician | |

| TP | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician | |

| OM | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician | |

| YZ | Zhanatas Wind Farm | Project technician | |

| DN | Almaty, Kazakhstan and Zhanatas Wind Farm | VP, Company Y | |

| NM | Almaty, Kazakhstan, Zhanatas Wind Farm, and Online | Head of Zhanatas Project, Company Y | |

| Officials | QJ | Zhanatas Town | (Deputy) Akim [Head of local government] |

| BJ | Zhanatas Town and Project site | Energy official | |

| WM | Online | Official | |

| NGOs | GC | Almaty, Kazakhstan | NGO staff |

| GQ | Online | NGO staff | |

| Academics | PS | Almaty, Kazakhstan | Professor |

| SL | Almaty, Kazakhstan | Professor |

- Note: anonymization measures were employed to protect the identity of the interviewees

Biography

Weishen Zeng ([email protected]) is a DPhil Candidate at the Department of International Development, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. His research interests include the politics of development, the politics of green energy, and the political economy of development banks.

REFERENCES

- 1 ‘Green energy’ in this article refers to energy derived from natural resources which are reproduced at a higher rate than they are consumed. This includes solar energy, wind energy, geothermal energy, hydropower and ocean energy. This definition is close to the United Nations’ definition (UN, 2025).

- 2 The term ‘state’ in this article encompasses not only government and governmental organizations but also the network of institutions that form the state apparatus.

- 3 In this article, the ‘central state’ refers to the national level of authorities in Kazakhstan's political system. The ‘local state’, unless indicated otherwise in the text, refers to the state apparatus that operates at the regional (provincial) level. The ‘foreign state’ refers to a sovereign nation outside Kazakhstan; in this article, the ‘foreign state’ is China.

- 4 See, for example, the literature on the uneven centre–periphery relations between Western countries and Africa since the 1970s (Wallerstein, 1974).

- 5 Interviews with QJ and BJ, Zhanatas Wind Farm and Zhanatas town, April 2024.

- 6 Interviews with MN, MD, OM and WM, Zhanatas Wind Farm and Zhanatas town, May and June 2024.

- 7 Interview, NM, Zhanatas Wind Farm, 13 May 2024.

- 8 Interview, KB, Zhanatas Wind Farm, 1 June 2024.

- 9 Focus Group with LJ, DR, OM and others, Zhanatas Wind Farm, 17 May 2024.

- 10 Interviews with NM, March to June 2024, in-person in Almaty and Zhanatas and then via video call.

- 11 Interview, NS, Zhanatas Wind Farm, 18 May 2024.

- 12 Interviews with MN, MD, OM and WM, Zhanatas Wind Farm and Zhanatas town, May and June 2024.

- 13 Interview, TB, Turkestan village, 28 April 2024.

- 14 Interview, GC, Almaty, 27 March 2024.

- 15 My interview with GQ, an environmental specialist, also supports this view.

- 16 Interview, MY, Zhanatas Wind Farm, 20 May 2024.

- 17 Interview, TB, Turkestan village, 28 April 2024.

- 18 Interviews with QJ and BJ, Zhanatas town, Zhanatas Wind Farm and Almaty, May to June 2024.

- 19 Interview, QJ, Zhanatas Town, 25 May 2024.

- 20 Interview, OM, Zhanatas Wind Farm, focus group, 3 April 2024.

- 21 Interview, SL, Almaty, 25 March 2024.