Defending the Land: Filipina Activists amidst Authoritarian Rule in the Philippines

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft. This research was generously funded by the ARC DP 220101503, Authoritarian Populism, Environmental Movements and Livelihood Change in the Philippines. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley-The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

ABSTRACT

In Southeast Asia, environmental and human rights activists resisting authoritarian rule and extractive development face harassment, intimidation and lethal danger in dramatically different ways. In the Philippines, this atmosphere of violence intensified under former President Rodrigo Duterte, a political ‘strongman’ whose militarized masculinity deepened the repression of left-wing women activists and other political opposition across the country. Despite macro-level studies examining the trends and patterns behind the surge in activist harassment, the micro-politics of Duterte's misogynistic and revanchist violence towards women activists has received insufficient attention. Drawing on feminist political ecology, this article explores how and why women activists on Palawan Island and elsewhere in the Philippines continued their advocacy work as they navigated intersectional spaces of violent misogyny and government repression. It shows how women activists in Palawan drew upon hope to persevere in their work amidst the violent atmospheres stoked by authoritarian masculinity. The article describes how the temporalities of intersectional gendered violence variously impacted the lives of women activists as they defended the environment and human rights on the island, while the country's highest office legitimated toxic chauvinism as a mode of governance.

INTRODUCTION

We defended the katutubo [Indigenous peoples]. We confronted illegal loggers, confiscated their chainsaws, and stopped those who illegally collected [forest] birds to be sold. In time, many people got angry at us, especially the buyers of the kiao. So as time went by, that was our life, but we continued our work.1

Shortly before Felicita Labog, an activist in southern Palawan Island, the Philippines, described her advocacy work to us in 2016, two hitmen on a motorbike had shot and killed her husband, Librito Labog,2 and a colleague after a meeting with their People's Organization (PO). Although Felicita's life was spared, the perpetrators threatened to kill her and her son if she continued her environmental activism. Despite going into hiding for several weeks, they continued to live in fear.

Felicita's tragic story is not an isolated case; it represents the harrowing reality faced by women environmental and human rights activists across the Philippines and Southeast Asia. These women stand on the frontlines of activism, defending agrarian frontiers, such as Palawan, from land grabs, resource extraction and human rights abuses (Aspinwall, 2020a; Loughlin and Milne, 2021). The situation has deteriorated dramatically for many women activists as authoritarian regimes worldwide tighten their grip on power, curtail civil liberties, amass resources and escalate violence (Grant and Le Billon, 2021; Loughlin and Milne 2021; Middeldorp and Le Billon, 2019; Neimark et al., 2019). Citing the Environmental Justice Atlas, Tran et al. (2020) note that violence against women has intensified across Latin America, Asia and Africa, particularly where multinational extractive companies, backed by governments and private actors, violently target them and their families. Already marginalized by institutionalized patriarchal oppression, these women disproportionately bear the violence of extractive development, while its benefits accrue to male capitalist elites (Tran, 2021; Tran et al., 2020).

Elected in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte's presidency unleashed a wave of authoritarian tactics, legitimizing and intensifying violence against left-wing activists across the Philippines (Curato, 2016; Dressler, 2021a; Maskovsky and Bjork-James, 2020). His anti-establishment populism, marked by illiberal ‘strongman’ tactics (Regilme, 2021), leaned on a rhetoric of perpetual crisis — whether drugs, communism or terrorism — to justify military and extrajudicial force (Curato, 2016; Miller, 2018). His confrontational style tapped into the sentiments of aggrieved sectors of society, using their discontent to legitimize violations of human rights, democratic institutions and the rule of law (Beck, 2020). Claiming to represent ‘the people’ and ‘the nation’ (Beck, 2020: 389; Moffitt and Tormey, 2014), Duterte deployed both discursive and structural violence against his opponents, through militarization and the erosion of civil liberties (Regilme, 2021).

Duterte's six-year term fostered an atmosphere of violence and impunity, enabling the harassment, intimidation and killing of countless environmental and human rights activists (Dressler and Smith, 2023; International Criminal Court, 2019; Theriault, 2020). While extrajudicial killings had surged under previous administrations — including Macapagal-Arroyo's post-9/11 counter-terrorism campaign (Regilme, 2021) — Duterte's misogyny and revanchism further normalized violence against women, especially women activists (Global Witness, 2019a, 2021; Parmanand, 2020). Despite legal protections such as the Magna Carta of Women (Republic Act 9710 of 2009; see Philippine Commission on Women, 2025), conditions worsened for women activists working in rural and urban areas throughout the Duterte presidency (Cook, 2019). Although direct causal links between Duterte's sexist rhetoric and violence against women defenders are difficult to establish, local women activists and NGOs have consistently voiced concerns that his misogynistic language emboldened others — predominantly men — to commit violence against women, LGBTQ+ individuals and activists (Parmanand, 2020).

Duterte's administration presided over horrific gendered violence. Beyond the hundreds of women among the 9,000-plus casualties of his ‘war on drugs’ (Jensen and Hapal, 2018; Mendoza, 2020; Reyes, 2016), at least 63 women environmental and land defenders were documented victims of extrajudicial killings, and 162 peasant women — including pregnant women and mothers with infants — were politically imprisoned (Global Witness, 2019a, 2019b, 2020; Karapatan, 2021, 2023). Many of these atrocities, fuelled by the violent rhetoric of Duterte's ‘war on drugs’, were accompanied by gendered harassment, intimidation and assault — long-standing issues in Philippine society (EJAtlas, 2021; Global Witness, 2019a, 2019b, 2020; Karapatan, 2021). The surge in violence against women activists under Duterte underscores the urgent need to examine how strongman rule, chauvinism and the suppression of leftist movements amplify threats to women's safety and political struggles. Indeed, this violence has persisted under the presidency of ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr., son of the former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, with at least 19 women activists murdered and another five forcibly disappeared since his 2022 election (Karapatan, 2024).

While the rise of authoritarianism and the murder of activists have been well documented across countries, including the Philippines (Butt et al., 2019; Dressler, 2021a; Loughlin and Milne, 2021; Menton and Le Billon, 2021; Regilme, 2021), far less is known about how women activists navigate and resist violence under authoritarian regimes. Studies rarely focus on how these women are able to persist in the face of escalating harassment, intimidation and violence (Pascale, 2019; Menton and Le Billon, 2021). Even fewer examine their subjective experiences or the grassroots efforts they undertake to sustain their work amidst uneven gender norms and authoritarian chauvinism. Notably, only Tran (2023), Tran and Hanaček (2023) and Tran et al. (2020) have comprehensively explored the gendered violence faced by Filipina environmental defenders. However, these studies have overlooked the everyday experiences and voices of women activists.

Our article aims to fill this lacuna by examining how and why women activists in Palawan — a frontier island in the Philippines which is gripped by escalating activist murders and extractivism — persisted in their work amidst the chauvinism and violence of Duterte's regime. We explore how Duterte's toxic masculinity and revanchist rhetoric permeated the local level, legitimizing both subtle and overt violence against women activists, despite the lack of evidence linking them to militant activism or insurgency (Dressler and Smith, 2023; Regilme, 2021). We show how these women's advocacy has endured nonetheless, fuelled by the hope of fostering positive change, while navigating varied violence (Mendoza, 2020; Reyes, 2016).

Drawing on feminist political ecology, we aim to deepen understandings of intersectional gendered violence and struggles under authoritarian rule, in which discursive and structural violence intersect to inflict compounding harms on women activists (Crenshaw, 1991; Nordstrom, 2004). Through ethnographic insights, we explore how women activists on Palawan Island experience and respond to overlapping forms of violence. We situate their activism within the broader context of civil society, extractivism and oppression in the Philippines, and the recent surge in resource accumulation and activist murders on Palawan. Rather than tracing causal ‘kill chains’ between the Duterte regime's authoritarianism and the violation of women activists’ rights, we document how these women navigate ‘slower’ and ‘faster’ forms of intersectional violence inflicted upon them and their families, and how, despite these challenges, they sustain activism through a sense of hopefulness. While the violence against women activists on Palawan parallels other instances of gendered violence against women defenders in the Philippines — both under Duterte and beyond — the way that patriarchal power among male political elites legitimizes such violence and suppresses these women's struggles remains poorly documented. Moreover, the everyday experiences of women activists and their responses to misogynistic violence under the former president, and more broadly in society, are often neglected and not well understood. In this context, a scaled feminist political ecology approach allows our analysis to move beyond narrow, unidimensional interpretations of violence to consider how the patriarchy of ‘violent atmospheres’ envelops the lives of women activists across the island (Mostafanezhad and Dressler, 2021).

After outlining our methods, ethical considerations and the dimensions of gendered violence, we explore the historical oppression and violence faced by women resisting social and environmental injustices in the Philippines under Duterte. We then examine the social history of civil society's response to extractivism on Palawan, focusing on how women activists navigate intersecting discursive and structural violence. We document how these forms of violence intersect at varying tempos, creating pervasive atmospheres of violence that permeate the lives and livelihoods of women activists.

METHODS

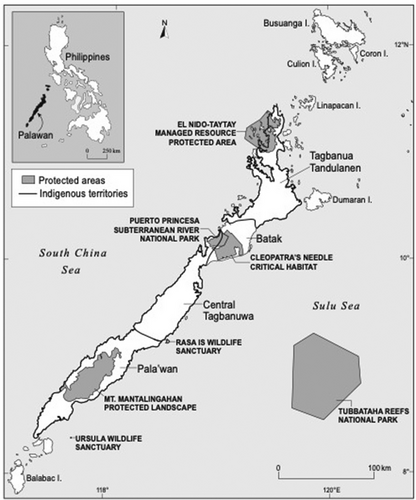

This article draws on a critical review of policy, media and interviews with women activists on Palawan Island in the southwestern Philippines (see Figure 1). To contextualize Duterte's presidential term, we examined five public websites, databases and media outlets (Philippine Daily Inquirer, Bulatlat, ABS-CBN, Rappler and Manila Times) to explore the broader challenges confronting women activists who face violence during their advocacy work. By triangulating these sources, we developed a reliable understanding of the political situations faced by various women activists on Palawan and beyond.

Palawan Island, the Philippines

© C. Jayasuriya, 2024 (Cartography, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)

We conducted semi-structured interviews to explore the experiences of women activists in Palawan, focusing on their social histories, community organizing efforts, local protests and use of state law to uphold social and environmental safeguards. Under Duterte's presidency, they all faced sustained harassment, intimidation and bodily harm ranging from sexist slander, to red-tagging,3 to murder. The interviews delved into the historical and contemporary violence experienced by women activists involved in environmental and human rights advocacy. We discussed public and private issues, including how gender inequality, chauvinism and caregiving responsibilities impacted their activism, as well as their perceptions of their roles as activists, mothers, partners and individuals. We considered how their sense of safety and security changed under Duterte.

In addition to five interviews conducted in the early 2000s by the second author, we recently interviewed 10 women activists involved in Indigenous rights, environmental and paralegal work, including frontline Indigenous women activists in rural Palawan. These interviews, conducted in Tagalog and English, took place in person in 2018 and online via video conferencing in 2021 due to COVID-19. We analysed the interview content using axial coding to identify broader themes from similar statements (Simmons, 2017). All interviewees provided informed consent and authorized the use of anonymized transcripts. We fully anonymized and de-identified all names, locations and organizational affiliations to ensure confidentiality and safety, omitting or redesignating specific contexts and geographical locations. We obtained formal approval from our university's Ethics Review Board in 2018 and 2020.

We are aware that our positionality influenced how we interpreted and communicated the results. Acknowledging that our gendered experiences and backgrounds differed from those of the women activists in Palawan (Trauger and Fluri, 2014), we approached this study with caution and a keen awareness of the potentially extractive nature of the research process in this and other political contexts (Oakley, 2016).

FEMINIST POLITICAL ECOLOGY, VARIED VIOLENCE AND WOMEN'S ACTIVISM

This article draws on feminist political ecology (FPE) to examine the micro-politics of women activists’ struggles against the gendered violence and marginalization arising from the confluence of patriarchal relations, environmental plunder and human rights abuses in the Philippines (Elmhirst, 2015; Rocheleau et al., 1996; Sultana, 2021). Partly developed in response to the white, male and Global North origins of political ecology, FPE's focus on gender as a central factor in shaping resource access and use (e.g. gendered knowledge, rights, organization) has foregrounded a feminist political economy analysis of power relations, struggle and marginalization amidst neoliberalism and global environmental change (Elmhirst, 2015). The field's alignment with feminist theories of power and subjectivity has emphasized how dominant patriarchal structures determine which gendered realities are valued, whose knowledge is recognized, and how institutional contexts can restrict women's lives and livelihoods over time (Rocheleau et al., 1996: 287; Sultana, 2021).

Building on these foundations, we adopt an intersectional FPE analysis to understand how women activists’ work and their responses to gendered violence are shaped by entanglements of class, ethnicity, age and religion amidst Duterte's toxic misogyny and chauvinism (Crenshaw, 1991; Elmhirst, 2015; Sultana, 2021). We show intersectional gendered violence emerging as a multifaceted and compounding harm that permeates society and impacts women activists’ everyday lives, fears and hopes (Kuperberg, 2018). This differentiated analysis recognizes that women activists do not all experience oppression and violence in the same way, but rather through intersecting and changing social relations, identities and structural conditions. Problematically portrayed as ‘naturally stoic’ (Roces, 2012), for example, Filipina activists’ struggles embody a dialectic of hope and despair in which a ‘cautious hope’ emerges relative to ethnicity, class, age and other factors (Anderson, 2006). We aim to challenge overly naturalized and undifferentiated categories of people, social relations and the environment by examining how gendered subjectivities and uneven struggles are co-produced through patriarchal violence — not only in the context of extractivism and authoritarian chauvinism, but also within broader societal spheres and the less visible spaces of everyday life (Elmhirst, 2015; Sultana, 2021). We show how the political desire to persist, with or without hope, is entangled with women activists’ struggles and practices.

As a modest contribution to new directions in FPE, our scaled, intersectional analysis of violence considers women activists’ hopes, frustrations and struggles as the violence against them saturates and impinges upon family life, work and broader societal conditions. Below, we consider the character and modalities of such violence and how it generates broader violent atmospheres in Palawan.

Types and Modalities of Gendered Violence

Gendered violence, in both discursive and structural forms, permeates and harms various facets of women activists’ lives and advocacy. This violence follows them along the spatial and temporal contours of public and private life, emerging gradually, dissipating and sometimes returning with devastating force that affects women activists and their families. Discursive violence includes historical events, ideas and beliefs that give rise to and legitimize socio-cultural stereotypes and expressions of gendered violence (Neumann, 2004). It involves deploying representations that perform and enable harm through naming, framing and enactment (Hall, 1985), for example, through publicly red-tagging women activists as communist terrorists. Such acts of signification subject something (a woman's body, caring roles, etc.) to political rhetoric that can reinforce gendered racialization, sexism and prejudice, reproducing gendered representations with significant emotional, biophysical and material consequences. As Roces (2010, 2012) describes, Filipina activists are subject to discursive violence that (re)constructs them as industrious, dutiful, caring, domestic women (Parreñas, 2015; Resurreción, 1999) who re-emerge as either ‘victims’ or ‘survivors’ rather than women with political agency and powerful legacies. This sexist discourse can gradually stabilize as received wisdom in society (Leach and Mearns, 1996), enveloping, subsuming and degrading women activists over time. As we show, Duterte's masculinized rhetoric and chauvinistic framings attempted to normalize and legitimate violence against women and women activists, making such framings easier to enact and forgotten by the public (Peluso and Watts, 2001).

With time, discursive gendered violence becomes cemented as structural (patriarchal) violence within and between societal institutions. Structural violence involves the less visible, implicit violence built into and harnessed from institutions (e.g. male-centred judiciaries, property rights), ideologies (e.g. anti-leftist) and political histories (e.g. anti-Muslim) in and of the dominant society (Galtung, 1969). Recognizing that women are not simply victims — indeed, they, like others, resist and overcome — Anglin (1998/2010) notes that gendered structural violence involves disciplinary techniques in law, economy and politics that emerge from and normalize the ‘status quo’ of patriarchy in society. Gendered hierarchies of control curtail the life chances of women activists (and women in general) through the routinization and normalization of dominant patriarchal discourses that subordinate them and their struggles (Anglin, 1998/2010: 147), such as the difficulties Filipinas face divorcing their husbands.4 Gendered structural violence thus reflects the institutional modalities or natures of harm that become regularized against women activists. Duterte's illiberal authoritarian regime amplified this gendered violence, making it systemic and embodied.

Gendered violence subsumes women activists’ public and private lives in ‘slow’ and ‘fast’ ways. Slow violence can ‘occur gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space’ (Nixon, 2011: 2). It is both visceral and psychological, playing out incrementally to produce environmental, social and physical injustices and harm. For example, discursive violence can emerge slowly and powerfully, reaching women activists through intermittent text messages with harmful sexist taunts or death threats, or as periodic media misrepresentations. Such violence can be diffuse, and it can be difficult to trace, identify, or assign culpability to perpetrators until it is too late (Nixon, 2011). Structural violence, even less visible, is often historically institutionalized and normalized, obscuring the perpetrators and their effects from view. However, both forms of violence often converge and ‘erupt … into instant sensational visibility’, the makings of fast violence with deadly consequences (ibid.: 2).

As such violence converges over time and space, it can amplify as broader ‘violent atmospheres’ across society under authoritarian regimes, exacerbating multifaceted harms, fears and anxieties among women activists and other marginalized groups. Overlapping gendered violences co-produce pervasive violent atmospheres across political, economic, social and environmental spheres (Mostafanezhad and Dressler, 2021). Atmospheric violence permeates all aspects of women activists’ lives, shaped by social histories, political and economic struggles, patriarchal structures and the drive for surplus accumulation. It is not merely territorial or a societal epiphenomenon (Tyner and Inwood, 2014: 771); it manifests in visual, non-visual and material forms through auditory, tactile and electronic modes of transmission. Under strongman authoritarian rule, these violent atmospheres are saturated with sexist language and patriarchal power dynamics, subordinating laws and practices through intertwined ideologies of capital accumulation and anti-leftist sentiments. Intersectional gendered violence is never an isolated event with discrete impacts; it is a societal unfolding with differential consequences at the individual, family and community level (Springer, 2011: 90).

Hope as Agency?

Far from being passive victims of violence, Filipina activists draw on the agency of hopefulness to persist amidst the discrimination and disadvantages entrenched in violent atmospheres (Crenshaw, 1991; Nightingale, 2011). In the Philippines, women activists’ experiences and struggles embody hope as much as frustration, fuelling their emotional investments in the ‘long game’ of protecting human rights and the environment. For many, a hopeful persistence can be powerfully generative. Hope can overcome fear and frustration by creating the political conditions or openings for real change, both now and in the future (Anderson, 2006; Wright, 2019). It represents a sustained investment in future-making among women activists who believe that they can positively influence outcomes, despite the fears and uncertainties stemming from harassment and other forms of violence (Dressler, 2021a; Kleist and Jansen, 2016; Wright, 2019). However, their hopefulness, while striving for better possibilities, is set against fear and concern. They understand how violence works to constrain their lives and those of their families (Anderson, 2006: 749). Such hopefulness is, therefore, not inherent to women activists’ struggle; rather, it ebbs and flows depending on the politics of struggle and the tumult of everyday life.

LEGACIES OF MASCULINITIES, MILITARIZATION AND RESPONSES FROM BELOW

Contemporary Philippine politics, economy and society — particularly gender relations, violence and responses to women's activism — have been profoundly shaped by the colonial legacies of Spanish (1565–1898) and American (1898–1946) imperialism. In particular, the ways in which patriarchal authority and powers have influenced property relations, military practice and resistance shed light on both the vilification of the Left and the plight of women activists under Duterte.

Sixteenth-century Spanish colonizers introduced a deeply paternalistic Catholicism and land law regime to the archipelago. Religious authority, property rights and ownership functioned together along the male line of authority, formally excluding women legally, politically and economically (Bejeno, 2021; Illo and Pineda-Ofreneo, 1995; Miralao, 1992; Rodriguez, 1990). The consolidation of elite male control over land and labour initially emerged under a feudalistic hacienda system (Rafael, 2018; Wright, 2019; Wright and Labiste, 2018), which opened new lands and concentrated peasants into smaller settlements (reduccion) (Anderson, 1976). As hacienda estates and trade expanded, smallholder production pivoted from subsistence towards export commodity crops largely under male ownership (Abinales, 2000; B. Anderson, 2010; E. Anderson, 1976).

After Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States in 1898, American colonial laws and policies incorporated the hacienda system, maintaining patriarchal control over land, labour and capital (Abinales, 2000; Bejeno, 2021; Rafael, 2018; Wright and Labiste, 2018). Despite the US colonial government's aim to break up land concentrations in 1903, most estates were sold to the male ‘Mestizo’ elite, who intensified cash crop production for the American market (Allen, 1938; Anderson, 2010). The 19th-century Torrens system further legislated property ownership under the male head of household, enabling male Filipino elites and the Catholic Church to consolidate peasant lands into larger private holdings, reinforcing their political power (Dressler, 2009; Miralao, 1992). The alignment of male authority in religion, property and capitalism entrenched patriarchal relations across family, state and religious institutions, at the expense of women (Miralao, 1992: 47).

After independence in 1946, agribusiness, mining, and extractivism persisted under the influence of male political elites in rural areas (McCoy, 2000), who retained legal and administrative authority over landed property and other natural resources (Miralao, 1992: 47). The landed elite's patriarchal control extended into family and community affairs in order to protect their political and financial interests (Fegan, 2009), with landlords increasingly using paramilitary forces to suppress leftist movements and their efforts to reclaim lands for tenant farmers (Bejeno, 2021; Fegan, 2009). While some women political elites held significant assets and lands, patriarchal power permeated most institutions including the Church, state, household and political clans, constraining women's political agency and opportunities (McCoy, 2000).

Since then, nationalist discourses have further propagated an enduring cult of masculinity centred on military service, armed operations and suppression of leftist dissent (McCoy, 1999, 2000; Rutten, 2001). The Republic's military institutions portrayed military men as courageous (and women as vulnerable) and military service as a rite of passage into manhood (McCoy, 2000). As military and police officers entered politics, they reasserted power and authority through local and national-level politics; others turned to paramilitary violence (Rutten, 2001). Militarized masculinity permeated elite political families and transnational corporations, which frequently used military operators, paramilitaries and hitmen to suppress activists defending land rights and agrarian reform (ibid.).

President Ferdinand Marcos's regime (1965–86) entrenched gendered violence and corruption, delegating control of public lands and resources to military and paramilitary commanders to secure patron–client relations and suppress communists and left-wing agitators during the Cold War. Influenced by American political and economic support tied to anti-communist interventions (IPON, 2012), Marcos's dictatorial rule and communist resistance set the stage for the oppression and red-tagging of leftists as part of broader surveillance and intimidation campaigns across the country (Holden et al., 2011; Rutten, 2001).5 As the military and police cracked down on anti-Marcos sentiment, communist affiliation and left-wing activism were conflated with violent intent. Many pacifist leftists appeared on secret lists of suspected communist collaborators circulated by the military or police, faced public accusations by prominent politicians, or were formally identified by various task forces. Many on these lists went missing.

State forces, alongside political elites and militias, violently evicted, marginalized and murdered agrarian reform activists and landless tenants (Kimura, 2006). Formed in 1969, the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA), escalated the agrarian struggle through violent guerrilla tactics (Dressler and Smith, 2023), engaging in a prolonged ‘people's war’ from the rural hinterland (Franco and Abinales, 2007). Many tenant farmers, including women, joined the CPP-NPA in response to land grabs and poor working conditions, while others were coerced by NPA threats. In response, Marcos imposed martial law (1972–81) to violently suppress the growing leftist and communist dissent (Vitug, 1993).

Less militant social movements also advocated for women's and peasants’ rights in the struggle against the Marcos regime (Dressler, 2021a; Lindio-McGovern, 2007; Roces, 2010). Women's groups formed coalitions, such as GABRIELA (General Assembly Binding Women for Integrity, Reform, Equality, Leadership and Action) to strengthen their role in the expanding anti-Marcos movement. However, after the military killed activist leaders like Lorena Barros and the state rescinded the Writ of Habeas Corpus, red-tagging and warrantless arrests surged, forcing many activists underground (Gomez, 1997; Roces, 2010). Red lists with the names of activists circulated as the state's militarized anti-communist agenda peaked (Dressler and Smith, 2023). Political elites, the military and landlords intensified red-tagging and intimidation, even targeting ‘centre-left’ activists with little sympathy for the CPP-NPA (Dressler, 2021a).6

Criminalizing Leftists Post-Marcos

After the People Power Revolt ousted Marcos in 1986, the harassment and killings of leftist activists temporarily subsided. The Corazon Aquino administration (1986–92) swiftly amended the Constitution in 1987, enshrining Indigenous rights, the right to protest and greater gender equality. However, these legislative gains were short-lived as political tensions between leftist activism, neoliberal extractivism and military repression once again escalated (Holden, 2014). Under President Fidel Ramos (1992–98) and subsequent administrations, neoliberal reforms and deregulation accelerated corporate investments in mining, plantations, dams and infrastructure on ancestral lands in frontier regions, such as Palawan (Dressler and Smith, 2023). Activists responded to corporate extractivism in different ways: some continued to support the radical left's armed struggle, while others shifted to peaceful protest, community organizing and policy reforms (Abinales, 2018; Dressler, 2009; Rutten, 2001). In both cases, state and non-state violence against activists persisted.

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo's tenure (2001–10), coinciding with the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in the USA, was especially violent for activists (Holden, 2011). Using millions of US dollars from foreign security agreements with the G.W. Bush administration, Arroyo launched a violent counter-terrorism campaign against Islamic terrorists and secessionist groups in Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago, and southern Palawan (Regilme, 2021). She expanded counter-terrorism policies, reinforcing militarized masculinities within state forces and targeting ‘left-wing political opposition, critical journalists, government critics, and local political opponents’ (Regilme, 2021: 88). With little credible evidence, her strategy conflated peaceful activist groups critical of government policies with terrorists (ibid.: 75), with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) often surveilling leftist activists during protests and marking them for execution (Holden, 2011). This normalization of counter-terrorism discourse and violence led to increased military interventions and a surge in extrajudicial killings, resulting in over 1,000 deaths during Arroyo's term, half of whom were affiliated with far-left NGOs (Karapatan, 2009). Of these, at least 131 were women activists (ibid.).

Rodrigo Duterte, then-mayor of Davao City, supported the Arroyo administration's violent suppression of insurgents and leftist activists. His endorsement of violent tactics, along with alleged ties to the ‘Davao Death Squad’ vigilante group — which targeted suspected criminals, street children and drug addicts — further fuelled the rise in extrajudicial killings under the guise of counter-terrorism. Although the killings of activists decreased under Benigno Aquino III's more pro-human rights presidency (2010–16) — 333 activists were killed, including 33 women among 139 human rights workers — Duterte's 2016 election as president led to a sharp escalation in state-sanctioned violence against environmental and human rights activists, particularly women defenders (Karapatan, 2021).

Duterte's Militarized Masculinity

After abandoning his campaign promises to tackle corruption, protect the environment and support Indigenous rights (Curato, 2016), Duterte pursued a violent blend of ‘authoritarian developmentalism’ across the country (Arsel et al., 2021; Bello, 2019; Crost and Felter, 2020). His administration, backed by Chinese infrastructure funding, lifted a nine-year moratorium on new mining and expanded palm oil plantations in Mindanao and Palawan, resulting in the repression and dispossession of rural smallholders (Bello, 2019; Dressler, 2021a). Partly to suppress rural resistance to extractivism, the president intensified legal and military offensives against remnants of the NPA insurgency and activists allegedly associated with the CPP (Dressler, 2021a). From 2017 to 2020, martial law was imposed in Mindanao, the National Taskforce to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC)7 was established, and the Anti-Terrorism Law (2020)8 was enacted. Almost anyone with leftist activist leanings was labelled a ‘communist’ terrorist and a threat to the state (McCoy, 2017a, 2017b).

Crucially, Duterte's revanchist and sexist rhetoric directed much of the discursive and structural violence towards women activists, with bloody consequences. As a ‘macho’ populist leader, his ‘militant form of masculinity’ was rooted in degrading women activists, crushing insurgents and targeting those involved, or accused of involvement, with drugs (Tapscott, 2020: 1570). Under Duterte, the historical link between the Philippine state, military service and masculine political authority (Brown et al., 2020: 18) was cemented through authoritarian strategies and violent tactics (Dressler, 2021a). Women and women activists bore the brunt of this toxic chauvinism, including harassment and intimidation.9

Duterte governed by wielding a violent mix of ‘street chauvinism’ and revanchist ‘jokes’ targeting women and their bodies, which resonated with predominantly male enforcement agencies (De Chavez and Pacheco, 2020; Gregorio, 2020). Cases of the president's misogyny abounded. After imposing martial law in Mindanao in 2017, for example, Duterte told male soldiers patrolling rural areas that they could rape up to three women without facing consequences (Gregorio, 2020), legitimizing the army's violent masculinity. His rhetoric then escalated when ‘joking’ about shooting rebel NPA women in the vagina as punishment for transgressing their roles as dutiful women and mothers (Parmanand, 2020). Without vaginas, he argued, these women would be ‘useless’ (Go, 2019: 34). Reflecting on the 1989 rape and murder of Australian missionary Jacqueline Hammill during his time as mayor of Davao, Duterte also infamously remarked, ‘I was angry because she was raped, that's one thing. But she was so beautiful, the mayor should have been first. What a waste’ (Burgos Jr. and Silva, 2016; Curato, 2016).

Duterte's weaponization of misogynistic discourse reinforced his governance agenda by sexualizing and degrading women's bodies and behaviours. This rhetoric further normalized sexism and toxic masculinity, emboldening other men to enact his misogyny through local violence (Rafael, 2020). Filipino human rights NGOs became increasingly alarmed by the escalating harassment, intimidation and killing of women activists under Duterte, with the NGO and human rights alliance Karapatan noting that: ‘while President Duterte rambles on with his sexist and anti-women rhetoric, poor women leaders are being killed in communities, while others face constant threats to their lives’ (Karapatan, cited in Gascon, 2018: 5). Duterte upheld patriarchal norms that policed women's bodies and behaviours, with his sexism serving as justification for often-violent outcomes (Manne, 2018).

The risks faced by women activists during Duterte's presidency intensified further during the COVID-19 pandemic. On 17 March 2020, Duterte declared the first ‘enhanced community quarantine’ for Metro Manila, with strict lockdowns imposed nationwide by early April (Aspinwall, 2020b). Under these emergency orders, the already dangerous work of women activists became even more perilous due to increased monitoring and restrictions. In rural and urban areas, activists who previously safeguarded themselves by altering travel routes, using safe houses and relying on protection from comrades were now spatially fixed — locked down — making them easier targets for state and non-state actors. At least half a dozen women activists were arrested, and two others were murdered by masked hitmen, as pandemic restrictions limited their ability to move (Dressler, 2021b).

The story of Elena Tijamo, 58, encapsulates the horror that many women activists endured during this time. Elena worked for an NGO, the Farmers Development Centre (FARDEC), offering paralegal advice to farmers on land disputes amidst widespread land grabbing (De Leon, 2020; Ecarma, 2020; Ellao, 2020; Esguerra, 2020; Marquez, 2020). Her rural activism (and that of FARDEC) allegedly ‘earned the ire of landlords in the region’ (Ellao, 2020).10 In early 2020, Elena reported a suspicious visit by individuals who claimed to be from the Department of Social Welfare and Development offering COVID-19 support, but who instead probed for personal information and failed to produce identification (Ecarma, 2020; Ellao, 2020). On the evening of 13 June 2020, six armed and masked men forcibly entered Elena's home (Ecarma, 2020). Her daughter and sister watched as she was allegedly thrown to the floor and had her hands bound and mouth gagged with duct tape. Despite their pleas and struggles, the figures dragged her away in front of her family members (Ecarma, 2020; Ellao, 2020; Esguerra, 2020). Over a year later, on 28 August 2021, Elena's body surfaced in a medical centre in Mandaluyong City. Her death remains unresolved (Ecarma and Bolledo, 2021; Enano, 2021).

Although the following cases on Palawan do not involve the murder of women activists, they highlight similar harassment and intimidation to that endured by Elena and others before their deaths under the regime. While each woman's situation is unique, they share common experiences of harassment, fear and grief. In the context of Palawan's social history, we present the lived experiences of three Indigenous women activists (Ate Carmela, Lambana Lazones, Felicita Labog) and two migrant activists (Ate Divina and Mahalia)11 from central and southern Palawan. These ‘centre-left’ activists continued their work under Duterte amidst a toxic mix of chauvinism, political repression and resource exploitation, on an island previously known more for its vast forests and biodiversity rather than for the harassment and intimidation of activists.

WOMEN ACTIVISTS OUT OF THE MARGINS: THE FIGHT FOR PALAWAN

Recognized for its contiguous forest cover, high levels of endemism, and diverse Indigenous peoples,12 Palawan Island was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1980 and quickly became part of the Filipino environmental imaginary (Fabinyi et al., 2019). While constructed as a notional ecological frontier by and for state and non-state actors, for the main Indigenous peoples of the island — the Pala'wan in the south and Batak and Tagbanua in central-north — it remains an ancestral home.

Drawn by Palawan's ‘unsettling beauty’ and a commitment to social justice, environmental and Indigenous rights NGOs arrived on the island in the late 1980s and 1990s to counter the legacy of human rights abuses and resource plunder from the Marcos regime (Goldoftas, 2006). Palawan's forests were being systematically cleared of valuable hardwoods by two major companies, Pagdanan Timber Products Inc. (PTP) and Nationwide Princesa Timber Company (NTPC), with timber concessions covering 168,000 hectares, or 25 per cent of the island's total forest area (Clad and Vitug, 1988; Eder, 1987). Between 1979 and 1988, an average of 19,000 hectares of forest were cut for timber each year (Clad and Vitug, 1988). Supported by Marcos, NTPC created logging roads to expand operations, bulldozing through and destroying much of the low-lying interior forest, including Agathis philippinensis, a conifer that produces Almaciga resin (Manila copal) harvested by Indigenous highlanders. Prominent politicians, military commanders and religious figures facilitated the continued extraction of not only timber but also rattan, Almaciga resin, copra and luxury seafood for global export (Clad and Vitug, 1988).13

Women Activist Stories on Palawan

In the early 1990s, as part of the Palawan-focused environmental movements, several women lawyer-activists (who shared social networks and studied law together at the University of the Philippines) established NGOs in Puerto Princesa City, the provincial capital. In 1989, the Palawan NGO Network Incorporated (PNNI) was founded by the charismatic Maani Banang (pseudonym) to unite NGOs and rural communities in countering the rise of inappropriate development in Palawan. Reflecting on that period, Banang noted in a 2002 interview, ‘It was a time when many government projects were coming here with no one examining whether they were suitable for the province. It was all being done through a top-to-bottom approach. But at that time, there were many NGOs … and most of them did not coordinate with each other and attempted to operate on their own’.14

When I was seeking funding for the CES, I had to set it up separately from another NGO because this was my dream; I needed more funding to get more lawyers. Wearing two hats would confuse people about where I belonged. I recruited another lawyer in 1994, and by early 1994, I had already set up the CES office here. Somehow, it worked out for me.15

By this time, the CES was already providing paralegal training to Indigenous peoples, farmers and fisherfolk, with a focus on land rights and environmental justice. Over time, Ate Divina expanded CES support to Indigenous communities facing broader social, political and environmental challenges. A close friend of Divina, Ate Carmela, assisted her uncle, a well-known Tagbanua priest, to establish the Indigenous rights NGO, the Indigenous Environmental Collective (IEC), in 1989. Influenced by her uncle's organization, the Indigenous People's Apostolate (IPA), under Carmela's guidance, the IEC grew into a well-organized, highly respected collective (currently representing over 57 Indigenous associations that are involved in community mobilization, paralegal advocacy and awareness building across Palawan).

During her time with the IEC, Carmela collaborated with PANLIPI to negotiate with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources for rattan-harvesting concessions, and to establish certificates of ancestral domain claims and, later, titled claims (Certificates of Ancestral Domain Titles — CADTs) (Pinto, 2000). Since its inception, the IEC has used laws such as the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 to help communities resist mining, plantation and other illegal activities in CADTs (or to negotiate with the perpetrators of such activities), while fostering partnerships with government agencies to award harvesting rights to Indigenous communities. Carmela recently left the organization to pursue intermittent activist work with Indigenous communities in southern Palawan.

In the early days, these women activists focused on building moral capital by investing in good ‘records and reputations’ (Hilhorst, 2000). Many NGOs relied on intermittently funded projects and community partnerships to raise Indigenous people's awareness of legal rights to ancestral lands and forests, enabling community mobilization and resistance against social and environmental crimes. The CES, PNNI and other NGOs provided paralegal training to local People's Organizations and Indigenous peoples, empowering them to carry out ‘citizen arrests’ of those involved in illegal resource harvesting. Larger corporations, such as mining companies, were taken to court. The more direct the intervention, the more violent the backlash against women activists and their colleagues.

Under multiple presidential administrations — from Ramos to Noynoy Aquino — mining operations and oil palm plantations expanded across central and southern Palawan Island (Dressler and Smith, 2023). By 2011, large-scale mining permits covered more than 38,303 hectares on the island, with additional applications targeting ancestral lands in the uplands (Novellino, 2014). Often flanking nickel mines, over 9,000 hectares of forests and farmland have been converted to oil palm plantations (Dressler, 2021a). Derived from ‘pinprick’ land grabs (Borras and Franco, 2024), smaller plantations for rubber, copra, cassava and other cash crops have also proliferated along new feeder roads, facilitating timber and wildlife poaching.

Recently, several young women activists have formed their own NGOs and POs to combat land grabs, extractive exploitation, and human rights abuses across Palawan. Many of the activists, including Mahalia, Lambana Lazones and Felicita Labog, serve as frontline defenders and community organizers. Mahalia, a migrant activist, co-founded and directs programmes at the Palawan Community Conservation Centre (PCCC), a female-led youth organization focused on Indigenous-led forest conservation. Lambana, an Indigenous woman, co-founded a PO that, in partnership with the IEC and PNNI, advocates against mining and palm oil plantations encroaching on ancestral lands. Felicita worked alongside her late husband, activist Librito Labog, to mobilize Tagbanua and Pala'wan communities in resisting land grabs, timber poaching and plantation expansion. Their PO was also affiliated with IEC and PNNI.

Below, the women activists describe navigating an increasingly violent atmosphere in both their public and private lives. Under Duterte, they faced chauvinistic harassment, red-tagging and threats of harm, all while balancing activism with family responsibilities.

Chauvinism-laced Harassment and Threats

On paper, it looks like there's a lot more equality [in the Philippines], [but even] declaring our organization as woman-led is a political statement in itself … community organizers and women going into the field to collect data face many more obstacles [than men] and the whole endeavour by our organization and our working, especially as forest conservationists, because we're women, has just been one challenge after another. [The environmental conservation space] is just dominated overwhelmingly by men, and … certain political stakeholders that, you know, don't want to work with us for reasons that don't seem clear, except that we're women.

So I'm about to give a really important presentation about a policy that needs to be passed, and I get interrupted because one of the members takes a liking to me and wants to know whether I'm single … and everybody just laughs ….

Definitely, there's been a shift in terms of what's allowed and what's not allowed. Like, I think that we're working in a space at the moment where … if you're a misogynist or you're sexist or, you know, you harbour or express those kinds of attitudes, it's harder to be shut down, because at the highest political office, it's accepted to act that way.

I do think that in terms of rhetoric, and what's politically acceptable to say openly, I think that there is definitely a lot less respect … because of the political environment we're in now.

We're women, and we're young …, and we're just easy targets. … Basically, we're covering these huge areas of remote forests, and if anybody just doesn't like us, it doesn't take much to get rid of us … [so] from a security perspective, I have to be very careful, [and] these are the kinds of concerns that, you know, a lot of men don't have to kind of deal with. It's a lot worse now.16

Red-tagging

Women activists must regularly navigate the overlapping discursive and structural violence of being red-tagged as members or sympathizers of the CPP and NPA, including the deep psychological and bodily violence this unleashes over time. Ate Divina (from the CES) recently learned that her organization had been red-tagged by intelligence personnel for allegedly being sympathetic to the ‘communists and the rebels’. She was worried, claiming, ‘this is all “a lot of talk”, anecdotal stories, and a lot of dangerous hearsay’. With a hint of exasperation, she stressed that the government had a significant military budget to conduct intelligence work and that red-tagging was often done by corrupt individuals ‘just to earn money’.17 In this way, numerous centre-left NGOs experienced escalating levels of harassment and intimidation due to Duterte's anti-communist campaign, spearheaded by the NTF-ELCAC and the surge in militarization near (and within) Indigenous communities across the countryside.

At the time, it was really hard for us to go into the community because of military checkpoints. We have to show our IDs, the company letter … just to prove that we do not support the NPA. … It's like an interrogation …. It's like they are almost saying that NGOs always support the NPA. … For us, it's too much. It really hurts us, the way the military interrogates us. So, for me, it's harassment.

The women leaders in the community … are the ones who bear the burden of all these harassments …. It really saddens me that, despite all of our women's laws, the reality is there's still a lot of killings. … But when I see women leaders killed … I cannot help but feel fortunate and lucky, still. I've experienced a lot of harassment [but] I'm thankful I'm not being physically attacked, you know, killed.18

The persistent threat of being red-tagged as a communist sympathizer posed a constant danger for mobile women activists working in remote areas of Palawan. This threat materialized through various means, including online trolling, public radio slander and official letters from the NTF-ELCAC — often without substantiation. The violence of red-tagging often escalates over time, manifesting through repeated public accusations and surveillance (Kunze et al., 2021). Powerful politicians frequently engage in systematic ‘smearing and tagging’ of NGO staff who oppose land deals and extractive projects that align with their financial interests or those of their constituents (Dressler, 2021b). The burden of proof then shifts to NGOs and women activists, forcing them to demonstrate that they have no ties to the CPP-NPA. Failure to do so can have severe consequences: red-tagging tarnishes organizational reputations, intensifies harassment and often culminates in the murder of staff members.

Various mining companies have entered our communities without pre-consultation with us … so we organized ourselves and with the help of NGOs, we told the mine over the radio waves not to operate here.

But we are prohibited now … the mine always says bad things about our group in public, so we are barred from the mining area. We are afraid to go near the mine now.

But we will continue our work, as we really don't want mining. Even if we are given millions of dollars, we won't accept mining because our lands and forests are enough for us.19

In the ensuing discussion, Lambana expressed concern that she might also be red-tagged one day.

Slow to Fast Violence

There's a lot of crimes and assassinations [in the Philippines]. It becomes a very lawless time during elections. I have to gear myself up because we have another election in May … so we have to make a safety plan for that time …. To give you an example, at our organization, before and after an election, we completely withdraw from all our community mobilizing work.

We essentially do political moratoria before and after elections for that reason. It's safety for the organization and safety for our female staff because if, for whatever reason, you know, someone doesn't like us, then the election is the best time to basically get us … when we're out in the field.20

Among the many experiences shared with us, Felicita Labog recounted the profound emotional stress and sorrow she endured due to the violence inflicted on her, her husband and their children. She explained how the legacy of this brutality continues to affect her and her children to this day, noting that before her husband, Librito, was murdered: ‘In our area, we saw the plight of the katutubo […] we saw their situation and together formed a katutubo organization to defend various aspects of their lives, because sometimes the government does not heed their complaints …. We faced all sorts of problems concerning illegal activities. Threats followed’.21

We requested two coffins so that they could be buried together … each with a coffin. After that, we brought him [the colleague] to his parents’ house and had a wake for him for five days. But our house … was guarded … there were people surrounding it because they threatened to blow up Librito's body and me, even though it was already in our house … that's how it was.

They would not let me go near the dead body because if they blew it up, I would be far from it and safe. After five days, we were about to bury him, but they still did not let me ride in the vehicle where the dead body was. They asked me to ride in a different car because they could still blow it up upon arriving at the cemetery.

I don't know why they hate that much. When we finally buried him, there was an SB23 member who said, ‘There! He's the one stopping the illegal activities here. He's tinik [a thorny threat]24 here in the town. He arrested a lot of people, so that's why he ended up dead’. This is what my child and my grandchild heard. And then, after that … on our last night, I heard they would barge into our house. They wanted to abduct us.25

The death of Felicita's husband and his colleague, along with the threats to her and her family, make this account deeply disturbing. While the PNNI and other NGOs assisted Felicita file a court case against those suspected of orchestrating Librito's murder, she and her children remained in mortal danger, forcing them to seek refuge in an undisclosed location (a ‘safe house’). The NGOs also assisted with her children's tuition fees and helped her establish a small sari-sari (general) store to provide additional income, lost after Librito's death. In this harrowing case, an activist mother and her children lost a loved one and had their lives and sense of security shattered, with little redress.

The combined impacts of military checkpoints, surveillance, red-tagging and heightened threats of sexual harassment have engendered deep fear and anxiety among these women activists. For many, the persistent fear of violence has severely restricted their daily mobility and quality of life. Remaining in one place to stay safe limits what can and cannot be done, constraining work and life chances. As the cumulative impact of ongoing harassment and sudden bodily violence lingers, these women activists and their families live in constant fear, with the entangled effects of slow and fast violence infiltrating their lives, compounding grief and suffering into the future. Indeed, Ate Divina acknowledged that learning about attacks on fellow women activists leaves her feeling anxious: ‘[it's] not good for [our] mental and emotional well-being … you also have to manage your stress … because there's still a lot of work to do’.26

Sustaining Hope and Persistence: ‘To Continue is to be Hopeful!’

Many women activists in Palawan emphasized that they would persevere with their work, despite the trials of balancing home life and the serious risks of activism. They explained that their moral commitments to social and ecological justice would endure while dealing with the responsibilities of caring for families and community activism in a male-dominated field (which implies having to work twice as hard as men to be heard and seen) laced with harassment and intimidation. Both Ate Carmela's and Felicita's stories illustrate how they sustained hope amidst the difficulties of balancing multiple roles and responsibilities.

I can say I will not stop working since I am the breadwinner of the family and since my heart is with my fellow katutubo … it's like it never ends, because when you go to the community you still need to have hope. The people recognize me as being with IEC, so they are always bringing me issues and problems to solve; ‘Can you help me?’, ‘Would you help us?’. So, I continue.27

Following her colleagues’ red-tagging experiences a few months earlier, she reflected further on being an Indigenous woman with a long-term commitment to helping katutubo: ‘For me, as long as I can help them, even in a small way, I will continue what I am doing. It's hard because you have to be balanced, since you have your family. I feel exhausted [but] there's still a lot of work that needs to be done’.28 Considerable emotional and physical labour goes into meeting the ever-changing needs of one's family, organization and Indigenous community partners. But hope fuels persistence. Mahalia found strength to continue her work in witnessing her colleagues’ determination to ‘keep fighting’ and ‘keep going’. For her, protecting the environment and supporting Indigenous peoples’ struggles for autonomy was ‘worth it. And at the end of the day, it's like you want to be on the right side of history’.29

Reflecting on the end of Duterte's term, Ate Divina and her staff also embraced a more hopeful politics. She noted that ‘we are hopeful. To continue is to be hopeful’, and argued that smaller local victories were the grounds for greater change at the national level: ‘perhaps there is hope’ in electing ‘a new set of leaders, a new president, who can again abide by what is in the constitution’.30 Filipina activists’ sense of hopefulness keeps them going in an increasingly constrained political space marked by discursive and structural violence. Ultimately, their perseverance is an investment in ‘future-making’ (Kleist and Jansen, 2016) with potential openings for positive change, despite the ongoing challenges of overwhelming sexism and violence. Remaining hopeful was — and is — a necessity.

DISCUSSION: FILIPINA ACTIVISM AMIDST VIOLENT ATMOSPHERES

Drawing on a feminist political ecology approach, this article has explored how the legacies of patriarchal colonialism influence the ways in which state and non-state actors co-produce gendered violence against women activists in the Philippines today. We described how intersectional gendered violence emerged as a multifaceted, compounding harm that infiltrated the public and private lives of Filipina activists, creating violent atmospheres of deep fear and anxiety under Duterte's rule. Through a scaled FPE analysis, our article revealed how structural and discursive violence work together to variously affect women activists, intersecting with their familial relationships, activist identities and sense of hope and despair. Often neglected in FPE is how modalities of violence manifest across different temporal and spatial dimensions—moving fast and slow from town to forest to home—following women activists across their lives and creating violent atmospheres that erode dignity and confidence. Going beyond a narrow causal analysis, we showed how such multi-dimensional violence, fuelled by sexist language, oppressive laws and patriarchal power, emerged gradually but erupted forcefully in gendered spaces, affecting the emotional politics of resistance. In the face of death and intergenerational trauma, these violent dynamics continue to shape the lived experiences of women activists in Palawan and beyond.

While the Duterte administration's record of extrajudicial killing of women activists may appear moderate compared to previous administrations, such as Arroyo's (Dressler and Smith, 2023; Regilme, 2021), Duterte's vulgar chauvinism and violent rhetoric legitimized a sexist, anti-left discourse that fed a violent atmosphere against Filipina activists and other progressives in the country. Under his rule, gendered violence manifested in varying intensities, affecting women activists’ experiences differently based on their histories and contemporary struggles. Despite these challenges, we illustrated how Filipina activists in Palawan persisted amid intersecting forms of sexism, red-tagging, bodily threats and resource plunder. Balancing multiple roles in their public and private lives, these brave women were able to continue their activism by cultivating cautious hopefulness, even as threats escalated. Their sense of hope, tempered by fear and frustration, fuelled their resistance struggles for social and ecological justice on the island (Anderson and Fenton, 2008; Terpe, 2016).

The Tempos of Violent Atmospheres

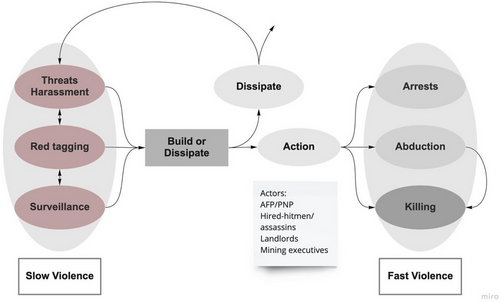

As demonstrated here, ‘slow’ gendered violence unfolds gradually but intensifies through the sustained harassment and intimidation of women activists via red-tagging and surveillance. These cumulative actions often culminate in dramatic events such as arrests, enforced disappearances and even murder, permeating local atmospheres with fear and anxiety. Such discursive violence operates through naming, framing and enactment (Hall, 1985), subjecting individuals to damaging political rhetoric that feeds prejudice and racialization (e.g. ‘upland terrorists’, ‘Muslim insurgents’). Over time, these representations become embodied and enacted in society, reinforcing blame and degrading victims with severe emotional, biophysical and material consequences.

The chronic anxiety experienced by women activists under Duterte's chauvinistic political repression exemplifies a deeper form of slow violence. His politics of fear operated both overtly and covertly, manifesting through online sexist slander and threatening text messages concerning bodily safety (Curato, 2016; McCoy, 2017a). Such slow violence — persistent yet insidious — spreads across time and space, embodying a delayed destruction (Nixon, 2011: 2). Women activists in Palawan revealed how slow violence materializes as mental and physical distress, exacerbated by systemic misogyny, red-tagging and the convergence of private and public responsibilities (or the ‘double day’) (Dressler, 2021a). As Christian and Dowler (2019: 1072) observe, ‘the invisibility of slow violence is deeply linked to the invisibility of feminized experience and space more broadly’.

While slow violence may dissipate, its various sources —online harassment, texting, stalking, public notices — can gain momentum and converge with other political events and circumstances, leading to arrest, abduction, or even murder (see Figure 2). As activists challenge powerful political actors, tensions escalate, thresholds are breached and harassment intensifies, often culminating in eruptions of ‘fast’ violence. This violence is never an isolated event; it is politically orchestrated, can occur in public arenas or private spaces, day or night. Often, these acts occur in front of the families of women activists, even with children present. Inflicting both physical and emotional harm, such violence is difficult to recover from and, in the worst cases, fatal. There is a persistent fear of being attacked.

Patterns of Repression (Slow/Fast Violence) of Women Activists in the Philippines [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: Authors’ design

Blurring Boundaries: Contesting Motherhood, Activism and Hope

The slow tempo of structural violence is particularly damaging for women activists who juggle family responsibilities, income generation and activist commitments. Embedded in patriarchal relations and institutionalized chauvinism, structural violence drives a less visible, often implicit form of harm rooted in state law and governance against women (Tran, 2023). Routinized patriarchal discourses and legal barriers (such as difficulties in divorcing, securing alimony and sharing familial responsibilities) reinforce gendered hierarchies of control that severely limit the life chances of women activists and their families.

On Palawan and in the Philippines more broadly, women activists navigated multiple roles within families, communities and political organizations, blurring the boundaries between political violence, activism and family life. Here, the personal becomes profoundly political (Pain, 2015). Perpetrators of violence against women activists disrupt both the public and private spheres these women seek to defend through their work. As a result, activists and their families are suppressed, silenced and dispossessed; red-tagging, criminalization and collective punishment become intergenerational among activist families. For example, Felicita and her children endured sustained harassment and fear before, during and after the murder of her husband, requiring that they be placed in a safe house. As younger generations witness the atrocities committed against their activist mothers (and fathers), they may either choose to continue the struggle for human rights and environmental justice or withdraw in fear. Intergenerational violence against women activists underscores the deeply violent and intimate entanglements of motherhood and activism.

Women activists in Palawan voiced how issues around intimacy, bodies and safety became sites of public amusement, contestation and conflict, with slow discursive violence gradually scarring their flesh and soul — the ultimate sacrifice for opposing government authority and resisting socio-ecological injustices. Sexist and chauvinistic acts frame, subsume and denigrate their bodies, beliefs and work as out of place, unacceptable and in need of control. Women are expected to balance their ‘gendered commitment’ to a cause with socially imposed responsibilities to their families and communities. The chauvinism that underpins the necessity of this balancing act is both compounding and constraining, emerging through the discursive and structural violence in Philippine society and disproportionately affecting women, mothers and their families.

Nevertheless, most women activists draw on hope to persevere in the face of adversity, creating the political conditions and opportunities for sustained justice (Anderson, 2006). Shaped by social position, age, ethnicity and political struggle, women activists’ hopefulness forces ‘openings in the present’ and acknowledges real ‘possibility in the now and the future’ (Wright, 2019: 1505). This sense of hope is powerfully generative; it ‘can be associated with a different way of being in the world, and a tenacious commitment to organizing together to realize it’ (ibid.: 1506). For many, being or becoming hopeful in difficult circumstances becomes an ordinary yet vital act of activism, one that ‘enables bodies to keep going’ (Anderson and Fenton, 2008: 78). Sustaining hope through practice (such as community mobilizing and protest) ensures that it is shared and realized as an attainable objective (Kotzé et al., 2013). As Ahmed (2004: 16) notes, hope, as emotion, can help enact change individually but, more importantly, can be amplified through solidarity networks within communities with shared struggles. Yet, a woman activist's hope is also fragile. When intertwined with despair, it oscillates ‘between absence and presence’ in the face of pervasive violence in the Philippines (Anderson and Fenton, 2008: 78).

In conclusion, our effort to document the multifaceted violence against women activists is also an act of hopeful ‘witnessing’: a reminder of what Filipina activists contend with daily. As Rose (2004: 30) notes, witnessing serves as a partial antidote to violence; it is ‘a refusal to succumb to the violence and amnesia; witnessing promotes remembrance and works against death’. Similarly, Hatley (2012) suggests that witnessing is a means of responding to the plight of others, summoning an ‘attentiveness’ to the ‘gravity of violence directed towards’ a particular other (ibid.: 3). FPE's attentiveness to women's subjective and embodied experiences of intersectional violence, particularly the local emotional politics of resistance, is crucial to witnessing the geographies of social and environmental injustices. Women's struggles for justice in the Philippines mirror those in other parts of the world, where the murder of women activists remains alarmingly routine (Menton and Le Billon, 2021; Tran et al., 2020). There is an urgent need for further critical feminist analysis and the witnessing of women activists’ grassroots solidarity building and resistance in the face of extractivist plunder and the global rise of authoritarianism. Our contribution is but one of many that seek to listen attentively, amplify the voices of women activists during times of deepening repression, and unearth the stories of those whose everyday resistance to state violence might otherwise be lost.

Biographies

Miriam Zimmermann ([email protected]) is an alumnus of the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia. She is currently an independent researcher interested in social and ecological justice issues.

Wolfram Dressler (corresponding author; [email protected]) is a professor of conservation and development in the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Ana Christina M. Bibal ([email protected]) is an alumnus of the University of the Philippines at Los Baños, the Philippines, with a research background in environmental justice, agrarian issues, forest conservation politics, and arts-based research and practice. She works with Indigenous peoples, environmental organizations and farmer-led networks related to Indigenous rights, agrarian struggles, seed and food sovereignty in the Philippines.

REFERENCES

- 1 Key informant interview, Felicita Labog (pseudonym), undisclosed location, March 2018. The kiao is the Palawan myna, an endangered bird.

- 2 Pseudonyms are used throughout this article to protect the identities of our informants.

- 3 Red-tagging is the practice of informally and formally labelling individuals, groups or organizations, or anyone with left-wing sentiments, as sympathizers, members or associates of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

- 4 Full divorce is largely impossible for women in the Philippines due to the patriarchal, Catholic-oriented 1987 Family Code (Fresnoza-Flot, 2019), although ‘separation’ is possible as marriages can be ‘voided’ through annulment (ibid.: 523).

- 5 Supreme Court Associate Justice Marvic Leonen defined red-tagging as: ‘the act of labelling, branding, naming and accusing individuals and/or organizations of being left-leaning, subversives, communists or terrorists (used as) a strategy … by State agents, particularly law enforcement agencies and the military, against those perceived to be “threats” or “enemies of the State”’ (see: https://verafiles.org/articles/vera-files-fact-sheet-why-red-tagging-dangerous).

- 6 While attempts had been made by early Philippine governments under Magsaysay (1953–57) and Macapagal (1961–65) to initiate land reform programmes to quell land-based peasant movements, these efforts were hampered by a conservative and largely male landowner-dominated Congress (Wright and Labiste, 2018). Rural development and resource extraction became the cornerstone of liberalizing Philippine economic development under the Marcos administration, which was held to ransom by International Monetary Fund structural adjustment programmes and American loan financing conditions (Crost and Felter, 2020; Lindio-McGovern, 2007).

- 7 The NTF-ELCAC was introduced in 2018 as the government's whole-of-nation approach to respond to the communist rebellion in the Philippines.

- 8 The new and revised Anti-Terrorism Law, with its broad, overly vague definition of ‘terrorism’, provided authorities with the pretext to manipulate its meaning and potentially target, arrest and detain critics of the government, including those working to defend land and the environment (Global Witness, 2019c; Human Rights Watch, 2020).

- 9 Well before his presidency, Duterte's image as the ruthless ‘Dirty Harry’ (after the film involving a police officer turned vigilante) mayor of Davao City (Thompson, 2016: 55) was forged by violently suppressing insurgencies and ‘salvaging’ alleged criminals to return ‘law and order’ to the city (ibid.: 53, 55; Human Rights Watch, 2009). Thompson (2016: 53) clarifies that the term ‘salvaged’ in this context is ‘an easily misunderstood Filipino-English expression that does not refer to saving someone but rather connotes their death through extrajudicial killing’. Duterte's violent mayoral record — transforming the once violent Davao into an ostensibly peaceful town with thriving businesses — promoted the ‘benefits’ of strongman rule and how it could be replicated across the country (Curato, 2016). His popularity as mayor of Davao was sustained during his six-year term, as he rode a wave of public discontent over crime, rising living costs and decaying infrastructure (ibid.).

- 10 In a house panel briefing in November 2019, both the Department of National Defense and the Armed Forces of the Philippines listed FARDEC as a communist terrorist front (De Leon, 2020).

- 11 To reiterate, the names of our informants/respondents are all pseudonyms.

- 12 The Indigenous peoples of the Philippines have been problematically defined and differentiated from broader Filipino society but may be best described as ethnolinguistic groups who have maintained degrees of cultural difference and independence from dominant society, during and after the colonial period.

- 13 With comprehensive evidence of illegal resource plunder in hand, other NGOs in Manila and Palawan began lobbying Congress to ‘Save Palawan’ through a signature campaign called Boto sa Inangbayan (‘vote for the motherland’), advocating for a commercial logging ban on the island. Haribon Palawan, the local chapter of Haribon Philippines (the country's oldest environmental NGO; Goldoftas, 2006) soon took up the campaign. Led by anti-Marcos activists and human rights lawyers from Manila, including Joselito Alisuag, they successfully petitioned for a logging moratorium across Palawan, which later expanded nationwide (Eder and Fernandez, 1997). After exposing military involvement in illegal logging on the island and starting the campaign in 1991, nine Haribon staff were arrested and interrogated by the Philippine National Police, while another five were charged with being members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (Human Rights Watch and the Natural Resources Defense Council, 1992).

- 14 Key informant interview, Maani Banang, Puerto Princesa City, June 2002.

- 15 Key informant interview, Ate Divina, Puerto Princesa City, June 2002.

- 16 Key informant interview, Mahalia, via video conference, February 2021.

- 17 Key informant interview, Ate Divina, via video conference, February 2021.

- 18 Key informant interview, Ate Carmela, via video conference, February 2021.

- 19 Key informant interview, Lambana Lazones, via video conference, February 2021.

- 20 Key informant interview, Mahalia, via video conference, February 2021.

- 21 Key informant interview, Felicita Labog, undisclosed location, March 2018.

- 22 Ibid.

- 23 The SB — Sangguniang Bayan or Municipal Council — is comprised of eight regular (elected) members and three ex officio members, including the municipal Indigenous Peoples Mandatory Representative.

- 24 Felicita uses the word tinik, which means thorn.

- 25 Key informant interview, Felicita Labog, undisclosed location, March 2018.

- 26 Key informant interview, Ate Divina, via video conference, February 2021.

- 27 Key informant interview, Ate Carmela, via video conference, February 2021.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Key informant interview, Mahalia, via video conference, February 2021.

- 30 Key informant interview, Ate Divina, via video conference, February 2021.