International Development Financing in the Second Cold War: The Miserly Convergence of Western Donors and China

We thank the editors and reviewers of Development and Change for their useful feedback on earlier versions of this article, and Aaron Magunna, Tristan Sluce and Monica DiLeo for their excellent research assistance. Responsibility for the final outcome is solely ours. This project was generously funded by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship FT200100613, ‘The Politics of Development Financing Competition in Asia and the Pacific’, and a University of Queensland ‘Capacity Building Package’.

ABSTRACT

China's rise as a major development financing provider is widely seen as challenging traditional donor states’ influence over the norms and institutions of global development and over aid recipients. Amid intensifying geopolitical rivalry, now often called a new or second Cold War, some argue that traditional donors are adopting Chinese-style practices to compete with China for developing countries’ allegiance. This article supports the convergence thesis but argues further that Chinese practices are also converging with those of traditional donors. Moreover, this convergence is on a less generous middle ground that will likely be worse for developing countries than the logic of geopolitical competition suggests. Rather than mobilizing additional resources, both sides are retrenching. This is because geopolitical competition is mediated through domestic political economy models entailing limits to providers’ generosity: China's commercial model confronts recipients’ declining repayment capacity, while traditional donors, unwilling to devote fiscal resources for aid, rely on mobilizing reluctant private finance.

INTRODUCTION

In February 2025, as this article was going to press and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was being forcibly dismantled by Elon Musk's ‘Department of Government Efficiency’, a reporter asked US Secretary of State Marco Rubio: ‘Isn't all of this angst, confusion, and upheaval a gift to America's geopolitical, geostrategic rivals such as Russia and China?’. Rubio replied: ‘This [is] not about ending foreign aid. It is about structuring it in a way that furthers the national interest of the United States’ (Rubio, 2025). It is unclear what this will involve, but early reports suggest USAID funding may be redirected to the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), established under Donald Trump's first presidency to invest in private sector operations abroad (Donnan et al., 2025).

Trump undoubtedly represents a more unilateralist and transactional approach to world politics. However, our contention here is that, notwithstanding his unusually dramatic attacks on USAID, the world's largest Official Development Assistance (ODA) provider, the ‘restructuring’ of ‘aid’ to serve narrow national self-interest long preceded Trump's return to office. In seeking to compete with China, Western states have become more like it, slashing real ODA and commercializing development assistance. As with his other policies, Trump is merely accelerating and being more open about these priorities. However, China has also become more like Western donors, reducing its disbursements of development financing and tightening governance to reduce risks and losses. The net result is to reduce development assistance to the Global South: a miserly convergence, not the generous courting of developing countries that many scholars of rising geopolitical competition expect.

China's rapid rise to become the biggest bilateral international development finance provider has long been viewed as challenging traditional donors, members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This challenge stemmed both from the vast size of China's programme, and its divergent model, involving loans for infrastructure megaprojects — neglected by Western donors — with few conditions, making them appealing to recipients. China has also refused to participate in the traditional donors’ institutions, notably the DAC, the OECD's Export Credit Group and the Paris Club, and to adopt their rules and norms (see Table 1). Its ‘rogue aid’ is widely seen as weakening traditional providers’ influence (Naím, 2009; Zeitz, 2021), and undermining the norms they espouse, including democracy, good governance and social and environmental protection (de Haan, 2011; Kragelund, 2019).

| DAC Norm/ Practice | Chinese Practice | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transparency: publishes what it funds | Opacity: very limited public data; lending contracts contain commercial confidentiality clauses |

| 2 | Aid: majority of transfers are ODA and concessional loans, targeted heavily at poorest countries | Commercial: flows are typically OOF, mostly commercial-rate loans to countries able to repay, often collateralized |

| 3 | Clear ODA/OOF boundaries, with rules against ‘tied aid’, benefiting donor-country firms | ODA and OOF muddled, often bundled with commercial projects, benefiting Chinese companies as implementers |

| 4 | Political-economic conditions often attached. Focus on poverty reduction, good governance, capacity-building | No conditions attached, except (implicitly) non-recognition of Taiwan. Focus on ‘hard’ infrastructure projects and productive sectors |

| 5 | High ESG and debt sustainability standards | Low ESG and debt sustainability standards |

Consequently, development programming became linked to geopolitical competition. Western observers and officials were already denouncing Chinese ‘imperialism’ and ‘colonialism’ in Africa by the late 2000s (Taylor and Xiao, 2009). China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, was seen as a strategy to undermine US hegemony (e.g. Kashmeri, 2019). US officials denounced Beijing for ensnaring developing countries in unsustainable debts so that China could seize strategic assets (see Jones and Hameiri, 2020). With geopolitical rivalry escalating, many observers herald a ‘new’ or ‘second’ Cold War (Schindler et al., 2024), with the West (at least until Trump's return to office) casting itself as defending the ‘rules-based international order’ against ‘revisionist’ states like China and Russia.

This neat binary has long been highly contestable. Several scholars argue that, in moving to compete with China, traditional development actors are converging with Chinese practices in the ‘Southernisation’ of development (Mawdsley, 2018a; see also Alami et al., 2021; Mawdsley et al., 2018; Zeitz, 2021). Mawdsley et al. (2018: O27–28), for example, argue that ‘the OECD-DAC donors are moving closer to some of the norms and modalities of … Southern partners than the other way around. This is motivated in part by growing respect for the[ir] achievements … but also by … fear that China and others are out-competing the “traditional” powers in pursuit of resources, markets and investment opportunities’. Similarly, Zeitz (2021: 267) argues that ‘the World Bank responds to competition by emulating the Chinese approach to development finance’. This corresponds to wider claims that the second Cold War will empower the ‘non-aligned’ Global South because East and West are competing for their affections by providing more ‘public goods’, including development financing (Ikenberry, 2024), allowing Southern countries to pursue independent development strategies hitherto off-limits (Chimhowu et al., 2019; Schindler and DiCarlo, 2022).

This article offers a different interpretation. We argue that providers’ domestic political economies condition their competition in global development, resulting in less generous assistance to developing countries. In the first half of the article, while agreeing that traditional donors’ practices have converged with China's, we highlight serious limits to their development ‘offer’, reflecting neoliberal constraints and self-interest, particularly reluctance to devote more fiscal resources to international development, especially since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Growing Western desire to compete with China — present since the late-2000s but intensifying under the BRI — consequently involves efforts to mobilize private finance, which is too risk-averse to meet development needs, and, consequently, parallel efforts to inflate donors’ contribution by changing DAC regulations. In the second half of the article, departing further from the ‘Southernisation’ thesis, we argue that China is also converging moderately with traditional donor practices and has also retrenched its offer. This is largely a reaction to the limits of China's commercial, profit-oriented development financing model. Poorly governed Chinese loans have provoked global criticism, particularly in the late 2000s and mid-2010s, and repayment challenges have mounted since the late 2010s, amid worsening economic conditions in the South. This has prompted tighter regulation and increased risk aversion, enhancing standards but contracting total lending. Chinese development policy has turned to smaller-scale activities, including in areas favoured by traditional donors. Consequently, given its protagonists’ constrained, self-interested behaviour, the ‘second Cold War’ will likely yield less development assistance for Southern countries than many imagine.

Methodologically, this article involves a high-level synthesis of the existing research base, supported by descriptive statistics on DAC and Chinese development financing. We reviewed the established literature to identify the main putative differences between the Western and Chinese models across the five domains in Table 1. We then compared these claimed differences to the available evidence on DAC and Chinese practices. As we will show, DAC practices are converging with China's across all five domains, while China is converging with traditional donors in the fourth and fifth domains. The article explains the drivers on each side before detailing the convergences identified.

TRADITIONAL DONORS’ CONVERGENCE WITH CHINA

This section argues that traditional donor practices have significantly converged with Chinese practices across all five areas of difference (see Table 1), through: declining transparency; the redirecting of ODA away from the neediest; the blurring of ODA/OOF (Other Official Financing) distinctions; weaker conditionality and a notional (but actually limited) shift to ‘hard’ infrastructure; and declining environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. This is caused not merely by the desire to compete with China, present since the late 2000s but intensifying from 2013, but principally by prevailing neoliberal policy constraints and unwillingness to devote additional fiscal resources for international development, particularly since the GFC, with ‘aid’ increasingly used to finance austerity-hit domestic budgets. This involves mounting dependence on mobilizing private finance, a long-standing objective cemented by the ‘billions to trillions’ agenda launched in 2015 to finance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The result is the commercialization of development assistance, entailing convergence with China's commercial model. Given private capital's reluctance to finance development, parallel measures seek to inflate Northern donors’ development contributions, including by weakening DAC rules. The North's competition with China is thus largely superficial, with limited benefit for the Global South.

Explaining Convergence: Neoliberalism, Financialization and Competition

Key to understanding Western donors’ convergence with Chinese practices is the growing financialization and commercialization of Western ‘aid’. This reflects long-standing neoliberal ideologies and constraints, later intersecting with growing competition from China.

Western donors and the multilateral development banks (MDBs) they dominate have sought to encourage private actors to facilitate and finance international development since at least the 1980s, when privatization was promoted through neoliberal structural adjustment policies. Nonetheless, until the mid-2000s, Western policy makers generally saw grants and concessional loans as more central tools of development assistance (Leigland, 2024: Chs 2, 8). For example, notwithstanding the promotion of public–private partnerships (PPPs), notably by the UK's Department for International Development and the World Bank's International Finance Corporation (IFC) (ibid.: Chs 3–5), the landmark report Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals (UN Millennium Project, 2005) stated that private investment would not flow to poor countries which lacked good infrastructure, healthcare and education, arguing it was the state's role to ‘push the economy over the threshold, so that private investors can earn [profits]’ (ibid.: 46). This was ‘entirely affordable’ if donors met their established target of devoting 0.7 per cent of gross national income to ODA (ibid.: xvii). Similarly, the 2005 Commission for Africa Report cautioned that PPPs could not fill Africa's infrastructure gap, calling for US$ 10 billion more ODA per year — to which donors ostensibly agreed (Leigland, 2024: 170–71).

Such optimism was crushed by post-GFC austerity and rising estimates of the development financing gap. Few Western countries had ever met the 0.7 per cent target, and fiscal austerity put intense pressure on aid budgets. While overall ODA was not cut, donor states increasingly used it to plug domestic spending holes (discussed further below), and benefit domestic businesses (Mawdsley et al., 2018). Simultaneously, however, the estimated cost of financing development rose dramatically, with the South's infrastructure needs alone costed at US$ 2 trillion by 2011 (Leigland, 2024: 171–72). This, alongside the world's failure to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, contributed to fractious negotiations through 2012–15 over their successor, the SDGs, with leading Southern countries — including China — demanding firm financial commitments from the West, and Western governments fiercely resisting this (Dodds et al., 2016).

Instead, Western donors turned to mobilizing private finance for development, a paradigm shift cemented by the 2015 launch of the ‘billions to trillions’ (BTT) agenda by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the five main regional MDBs. They noted that ODA totalled US$ 135 billion in 2015, but implementing the SDGs required US$ 1.4 trillion more in low- and lower-middle-income countries alone (AfDB et al., 2015: iii; Mawdsley, 2018b: 192). While ODA was unlikely to fill this gap, ‘large amounts of investable resources, mostly private’, existed (AfDB et al., 2015: 2). The institutions therefore proposed that ‘billions’ of ODA dollars should be refashioned to ‘crowd in’ ‘trillions’ of private-sector dollars — hence ‘billions to trillions’ (ibid.). Since private investors are not controlled by donor states but are motivated by ‘risk–reward considerations’, development agencies would ‘need either to decrease perceived risk or increase anticipated returns’ so that ‘private business can deliver profit’ (ibid.: 2, 12, 13). This agenda fostered the creation or revitalization of many Northern development finance institutions (DFIs), such as British International Investment in the UK and the Development Finance Corporation in the US. Although backed by public money, the funds that DFIs ‘mobilize’ are mostly private: 72 per cent, according to Attridge and Gouett's (2021) study of 12 leading examples.

Growing competition with China was a second, related driver of change. As mentioned, some Western commentators and policy makers began warning about China's role in Africa in the late 2000s. This reflected wider concern about the potential impact of ‘rising powers’ on global order, including in international development. This involved not only China but also ‘new’ actors like Brazil, India, South Korea and Turkey, disregarding DAC rules while using development financing to advance their own commercial and strategic interests. Initially, the DAC sought to co-opt these rising powers through ‘aid effectiveness’ discussions, culminating in the 2011 Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) (Kragelund, 2019: 114). However, China and others insisted that, as developing countries, they could retain their ‘unorthodox’ practices, rendering GPEDC effectively defunct by 2014 (Bracho, 2017). Many traditional donors still hoped to draw China into existing liberal norms by joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, launched in 2014, and shaping its rules — though the US and Japan were by then implacably hostile. By the early 2020s, Northern donors had moved openly to compete with China's BRI through initiatives like the US-led Blue Dot Network (launched in 2019), the G7's Build Back Better World (B3W) in 2021 and its Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII) in 2022, and the EU's Global Gateway Initiative in 2021.

Meanwhile, Western development practices had also moved in the commercial direction of China and other rising powers. As noted above, post-GFC, aid was increasingly reconfigured to benefit Western firms. Intersecting with the BTT agenda, trade and investment promotion (arguably principally benefiting Northern states) was also repositioned as mutually beneficial development cooperation, echoing China's ‘win-win’ rhetoric (Kragelund, 2019: 120; Xu and Carey, 2015: 867). Export credits and loans were presented as forms of development financing, merging development, trade and investment objectives that the DAC had traditionally sought to firewall (Mawdsley, 2018a: 182). This reflects deeper mutations within post-GFC neoliberalism, whereby Western governments and global governance institutions have embraced — albeit selectively and partially — aspects of ‘state capitalism’ in response to globalized capitalism's intensifying contradictions, including sclerotic growth, political disaffection and populist challenges, and the shift of economic and geopolitical power to Southern states like China (Alami and Taggart, 2024; Alami et al., 2024).

Existing criticism of these developments has, we think, missed the mark. Typically, critics argue that mobilizing private finance is about further subordinating development policy to capitalist interests by providing new investment and export opportunities (Gabor, 2021; Mawdsley, 2018b; Mawdsley et al., 2018). This implies strong capitalist interest in such expansion, which dictates policy making amid neoliberalism. However, remarkably little private finance has been mobilized for development, implying considerable capitalist disinterest (Bernards, 2024; Hameiri and Jones, 2024a). As discussed further below, quantifying this disinterest is difficult because Northern states conceal their dubious methodologies for calculating the quantity of private finance ‘mobilized’. However, accepting the OECD's (2024a) figures, the quantity has only risen from US$ 27.7 billion in 2015 to US$ 61.7 billion in 2022, with over a quarter comprising guarantees, which mostly involve no actual disbursements. With ODA totalling US$ 287 billion in 2022 (UNCTAD, 2024) — which is open to question, as discussed below — the ODA-to-private finance ratio is 1:0.2 — hardly consistent with ‘billions to trillions’ expectations.

The sectoral picture is similar. In 2009, Northern states pledged to ‘mobilize’ at least US$ 100 billion annually to help developing countries tackle climate change. This target was unmet until 2022, and even then, just 19 per cent of the total comprised private financing ‘attributed’ (again, questionably) to Northern agencies’ mobilization efforts (OECD, 2024b). The quantity of private finance mobilized for Southern infrastructure actually fell after BTT was launched, despite the North's ostensible desire to compete with China's BRI. The annual average declined from US$ 37 billion in 2008–14, to US$ 13 billion in 2015–17, to just US$ 9.3 billion in 2019–22 (IFC 2021, 2023, 2024; Tyson, 2018: 15). Risk-averse, profit-oriented investors instead redirected cash towards Northern markets, reflecting the tapering-off of US post-GFC quantitative easing and, more recently, rising interest rates. In 2023, private investors collectively withdrew US$ 200 billion from developing countries, dwarfing ODA and entailing a net US$ 68 billion outflow. Summers and Singh (2024) called this a ‘disaster in terms of support for the developing world … “billions to trillions”… has become “millions in, billions out”’.

The financialization of development is less a sign of capital's strength and determination than of the neoliberal state's weakness, with policy makers turning desperately — but unsuccessfully — to private finance to compensate. Northern governments have refused to substantially increase ODA spending, which would have allowed them to directly address the SDGs or compete with China. Average DAC ODA spending in 2023 was 0.37 per cent of GNI; only five donors met the 0.7 per cent target (OECD, 2024c). Moreover, as elaborated below, ODA is increasingly spent domestically and inflated by non-fiscal contributions. As Bernards (2024: 97–99) argues, challenges of inequality, underdevelopment and climate change ‘call for the mobilization of social resources on a global scale’. Yet, under neoliberalism, many ‘State institutional structures have … been hollowed out, and fiscal constraints … have been progressively tightened’. With the direct expropriation and use of capital rendered unthinkable, policy makers have little alternative but to try to ‘coax private capital into investing in Development’; yet capital's reluctance produces outcomes that ‘look precisely the reverse of capital “prospecting” for new streams of income’.

Accordingly, traditional donors have taken a performative turn, fudging and inflating figures to create the appearance of generosity and effective competition with China. Increasingly extravagant announcements often lack substance. For example, the G7's B3W promised to mobilize ‘hundreds of billions’ of dollars in 2021; in 2022, the PGII pledged ‘up to US$ 600 bn’ by 2027 (Hameiri and Jones, 2024a: 699, Table 1). Yet, as the aforementioned figures demonstrate, the quantity mobilized is paltry. Several Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) have been signed with important developing countries, pledging ostensibly impressive public and private investments. For example, Indonesia's JETP promised US$ 10 billion of each. However, just US$ 295.4 million of the public money pledged (less than 3 per cent) comprises grants and technical assistance, and only US$ 384.5 million (3.8 per cent) comprises equity investment. The bulk involves loans (US$ 6.9 billion concessional, US$ 8.4 billion requiring sovereign guarantees), and MDB guarantees (US$ 2 billion) that may never actually be used (Indonesia JETP Secretariat, 2023: Ch. 7), permitting apparent generosity without fiscal cost. Meanwhile, the US$ 10 billion private commitment is a purely notional target: private institutions will only invest where they see profitable opportunities. Senior Indonesian minister Luhut Pandjaitan thus remarked, ‘“where is the money?” … They're just talk’, saying Indonesia would still court Chinese investment (Rachman, 2023).

TRADITIONAL DONORS’ CONVERGENCE WITH CHINESE PRACTICES

The upshot is that traditional donors increasingly converge with Chinese practices and norms across all five domains identified in Table 1 (above), albeit with the aim of fudging and inflating their contributions, rather than emulating China to compete more generously and effectively for the Global South's affections.

Domain 1: Traditional Donors’ Development Programming Is Becoming More Opaque

Chinese development financing is notoriously opaque: Beijing publishes only occasional, questionable, high-level summaries, leaving academic researchers to discover the detail (Parks et al., 2023). While traditional donors remain more transparent than China, growing private sector operations entail greater opacity. Two developments are particularly important: DFIs’ growth relative to traditional aid agencies (discussed here), and changes to the ODA definition (discussed in the next subsection).

DFIs, the main institutions tasked with mobilizing private financing for development, operate very opaquely. As Attridge and Gouett (2021: 51) note: ‘There's little disclosure of investments, [or] documentation that supports investment additionality [i.e. claims to have mobilized investment that would not otherwise have materialized], or how impact is calculated’. One NGO ranked the transparency of 21 DFIs’ non-sovereign (private) operations and nine DFIs’ sovereign operations across 47 indicators. Transparency was higher for sovereign operations, although the top-ranked Asian Development Bank only scored 75.9/100. In non-sovereign operations, the IFC scored highest with 54.4/100. The top-scoring bilateral DFI was the DFC at sixth place, with just 38.2/100 (PWYF, 2023: 5, 16, 17). DFIs disclosed almost no information about non-sovereign investment results, the aggregate mobilization of private finance, or ESG issues (ibid.: 6, 26, 30–32). Verifying whether DFIs mobilize private finance efficiently or invest impactfully and ethically is consequently impossible.

Non-disclosure is often justified on grounds of ‘commercial confidentiality’ (Attridge and Gouett, 2021: 12). Opacity is exacerbated by DFIs’ preference to invest via local private ‘financial intermediaries’ (FIs), such as banks, funds, microfinance institutions and insurers. Whether these commercial actors fulfil DFIs’ mandates is unclear given their own opacity and limited DFI reporting (Attridge and Gouett, 2021: 29; PWYF, 2023: 34). This allows DFIs to inflate their mobilization figures and hence their developmental contribution (Kenny, 2020a). DFIs also provide little information about their investments’ ‘additionality’. Since additionality is DFIs’ main claim to be adding value, this undermines the credibility of reported figures (Attridge and Gouett, 2021: 52). Indeed, it creates the impression that risk-averse DFIs and their shareholders are, like their Chinese counterparts, focused on financial returns, not developmental outcomes (ibid.: 9). Risk aversion also constraints DFI investment for geopolitical goals in riskier markets.

Domain 2: Development Financing is Redirected away from ODA and the Neediest

Historically, traditional donors delivered most development assistance as ODA, and poorer countries received more ODA per capita and higher grant components than better-off countries (Steensen, 2014: 43). For example, from 2000 to 2017, three-quarters of US development financing was ODA, while just 12 per cent of Chinese financing was ODA-like, the bulk comprising commercial-rate lending to wealthier/resource-rich countries (Malik et al., 2021: 12, 17, 19, 37).

Today, however, ODA's share of development assistance is falling, and traditional donors are redirecting ODA away from the neediest. From 2013 to 2022, the share of ODA going to least-developed countries (LDCs) fell from 35 to 22 per cent, decreasing nominally from US$ 67.5 billion to US$ 65 billion in 2021–22 (UNCTAD, 2024: 13). From 2021 to 2022 alone, the share unallocated by income group rose from 34.2 to 44.7 per cent (OECD, 2023: 124–25). This reflects the increasing use of ODA to ‘fill funding gaps in other international and domestic agendas’, causing ‘reporting to become increasingly convoluted … opaque’ and unreliable (DAC-CSO Reference Group, 2023). In 2022, 19 per cent of ODA was never transferred to aid recipients (Craviotto, 2023: 9). Notably, to support its war with Russia, middle-income Ukraine was ‘allocated’ US$ 29.2 billion in ODA in 2022 — more than the next five countries combined, or any other country in history (Knox and Wozniak, 2024). From 2019 to 2023, the share of bilateral ODA spent on refugees — often domestically — increased by 184 per cent, from US$ 10 billion to US$ 29 billion, whereas all LDCs combined received just US$ 37 billion annually (OECD, 2024c). Donors also use ODA to fund climate mitigation outside aid-receiving countries. They have further inflated ODA by counting activities like the donation of surplus COVID-19 vaccines (7 per cent of total ODA in 2021) (Craviotto, 2023: 9). Although this padding ostensibly pushed ODA from DAC member countries to a record high of US$ 223 billion in 2023, eight major donors announced aid cuts in 2024 which, even before the Trump administration's assault on USAID, meant even artificially inflated ODA figures were set to fall (Gulrajani and Pudussery, 2025).

Furthermore, as development financing becomes commercialized, grants are increasingly being replaced by loans, allocated according to repayment capacity, not need. From 2012 to 2021, the share of ODA delivered as grants fell from 68 to 63 per cent, with concessionality declining, despite the Global South's mounting debt crises (Ritchie, 2024; UNCTAD, 2024: 10). Between 2013 and 2018, 80 per cent of funds mobilized by DFIs went to middle-income countries (MICs), versus 6.4 per cent to low-income countries (LICs), with the bottom decile receiving only 1.7 per cent (Attridge and Gouett, 2021: 24, 26). This reflects DFIs’ low risk appetite, given their mandates to remain self-financing (hence profitable) and to raise capital through risk-averse private investors (ibid.: 25). Both Chinese financiers and DFIs prefer loans over riskier equity investments. In 2013–18, the share of loans in funds provided by bilateral DFIs rose from 71 to 76 per cent, while the share of equity fell from 16.8 to 12.6 per cent (ibid.: 30, 32).

While the ODA provided to Ukraine suggests that ODA could be diverted to serve geopolitical goals, even there much of the spending supported Ukrainian refugees within donor states (Ursu, 2024). Furthermore, given fiscal austerity, ODA allocations are zero-sum: spending on one issue or country entails cuts elsewhere, denoting hard limits on traditional donors’ capacity to compete with China or Russia.

Domain 3: Blurring ODA/OOF Boundaries

Growing commercialization is also leading donors to blur the boundaries between ODA and OOF, by changing the definition of ODA and adopting new ‘comprehensive’ development financing measures that inflate their generosity, rather than genuinely expanding provision.

Historically, the DAC strove to de-commercialize aid by distinguishing rigidly between ODA and OOF — categories China eschews. Until recently, the DAC defined ODA as fiscal contributions, bilateral or via MDBs, aimed at promoting recipients’ development and welfare, with at least 25 per cent delivered as grants and the rest as highly concessional loans. Other Official Financing includes export credits, regulated by the OECD's Export Credit Group to prevent member states subsidizing their exports (Hopewell, 2021). The DAC also regulates ‘tied’ aid benefiting donor-state businesses, limiting it to poorer countries and requiring high concessional funding (OECD-DAC, 2025).

However, under pressure from austerity-racked member states, the DAC has steadily revised its definitions to allow activities to be counted as ODA without additional fiscal allocations. In 2016, ‘private sector instruments’ (PSIs) were introduced, incorporating official support to private sector companies in developing countries (Craviotto, 2023: 3; Griffiths, 2018). In 2018, the UK, seeking to inflate its aid figures to meet the 0.7 per cent target amid austerity, pushed the DAC to count DFI profits (which benefit donors) as ODA, threatening otherwise to act unilaterally (McVeigh, 2018). Consequently, from 2019 the DAC definition incorporated the ‘grant equivalent’ element of various forms of financing. For PSIs, the ‘grant element’ is based on the ‘discount rate’ of loans (the estimated rate at which the value of loans declines). If expected real-term returns are lower than the amount loaned, the difference is seen as grant equivalent. DAC rules effective from 2024 also permit government capitalization of DFIs and individual DFI activities that meet grant-equivalence standards to be counted as ODA (OECD-DAC, 2023).

Although PSIs currently comprise only around 3 per cent of ODA (OECD-DAC, 2023), these definitional changes significantly blur the ODA/OOF distinction, allowing donors to inflate aid figures without increasing fiscal effort and incentivizing them to deprioritize grants. This also represents convergence with China, as the bulk of its development financing is not financed fiscally but through policy banks’ bond issuance and profits from lending (Chen, 2024). New DAC rules allow instruments to count as ODA without any budgetary subsidy, including lending to private actors at market terms, investing in commercially viable and profitable projects, and selling guarantees to banks on their loans to developing countries. They only require that PSIs need be ‘concessional in character’ by providing financial ‘additionality’ (Craviotto, 2023: 4, 12). However, reflecting DFIs’ dubious measurement of, and claims around, ‘additionality’, analysis of the 2018–21 PSI data suggests that donors fail to demonstrate projects’ additionality (ibid.: 3). The discount rates used to calculate grant equivalence are also ‘far too high to reflect real donor effort’ (ODA Reform, 2023). Finally, donors can also now count debt forgiveness as ODA, recorded at a level higher than the amount actually forgiven. While ostensibly intended to incentivize debt relief over new lending, critics counter that no incentive is required, since relief is motivated by countries’ inability to repay; this is merely enabling ODA double-counting, first as loan, then as forgiveness (Saldinger, 2020). Moreover, given their commercial orientation, the rise of PSIs is accelerating the redirection of ODA, with 96 per cent of ODA-as-PSIs targeting MICs. PSIs are also often tied to benefit donor-state companies (Craviotto, 2023: 4).

The OECD's new statistical framework, ‘Total Official Support for Sustainable Development’ (TOSSD), introduced in 2021, also blurs ODA/OOF distinctions. The OECD claims TOSSD captures ‘the full array of resources to promote sustainable development in developing countries’, including ‘non-concessional flows, SSC [South–South Cooperation], triangular cooperation, activities to address global challenges and private finance mobilised by official interventions’ (Tomlinson, 2021: 9). To count, activities must contribute towards at least one SDG without undermining another. Pillar 1 of TOSSD measures cross-border flows, while Pillar 2 counts support for ‘international public goods, development enablers and global challenges’ (ibid.: 20).

TOSSD enables enormous inflation of countries’ SDG contributions. With ‘sustainable development’ left undefined, providers use different and questionable criteria. For example, two-thirds of reported energy sector activities supported non-renewables (ibid.: 24–25). Pillar 2 creates an even bigger loophole by allowing domestic spending to be counted based on questionable claims of benefit to developing countries. In a 2019 pilot, providers used 60 per cent of Pillar 2 funding not already monitored by the DAC's Creditor Reporting System domestically (ibid.: 31, 40, 44). For SDG 1 (ending poverty), 44 per cent of expenditures were in Pillar 2, while for SDG 10 (reducing inequality) and SDG 13 (addressing climate change), Pillar 2 shares were 58 per cent and 45 per cent respectively (ibid.: 36). Figures are further inflated by counting credit lines and guarantees that involve no actual expenditure, which comprised around half the so-called ‘mobilized’ financing reported in 2019 (ibid.: 49). As Cutts (2022) summarizes, ODA ‘statistics are no longer credible … donors have exaggerated their generosity at every turn, creatively padding the figures to give themselves room to cut their real aid expenditure’.

Domain 4: Weakened Conditionality and the (Failed) Shift towards Infrastructure Financing

The fourth convergence area is DAC donors’ weakening conditionality and ostensible return to infrastructure financing, though reliance on mobilizing private finance entails little practical benefit for developing countries.

As noted, to compete with China's BRI, Western donors have made increasingly extravagant pledges to finance Southern infrastructure1 (Hameiri and Jones, 2024a). The BRI's attraction was Beijing's willingness to lend large sums for, and quickly deliver, infrastructure projects without intrusive conditions. Some evidence suggests that, even before their vaunted return to infrastructure, traditional donors were diluting conditionality to compete with China (Chan and Lee, 2017). Where Chinese borrowing is higher, the IMF and MDBs impose fewer and weaker conditions (Groce and Köstem, 2023; Hernandez, 2017; Sundquist, 2021; Zeitz, 2021), and the democratizing effects of DAC aid diminish, suggesting weaker political conditionalities (Li, 2017). The IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization's governance prescriptions also display ‘partial convergence’ with state-capitalist practices (Alami and Taggart, 2024). However, other research shows that when countries heavily indebted to China seek IMF assistance, they often face heavier conditionality (Kern and Reinsberg, 2022).

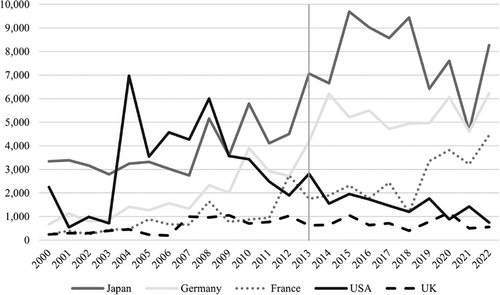

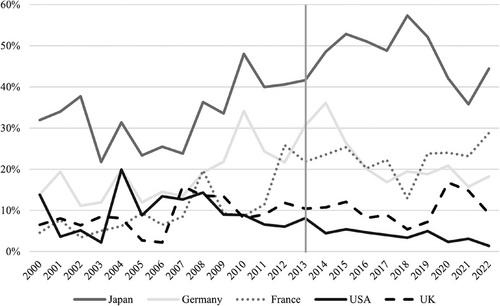

Perhaps more importantly, traditional donors’ infrastructure development support remains paltry. Despite forceful rhetoric around competing with China, and with the partial exception of Japan, lead donors’ ODA spending on infrastructure after the BRI's 2013 launch saw no sustained or substantial increase. Although French and German ODA was more infrastructure-focused than that of the US or UK, there was no dedicated ramping up on the scale needed to compete with the BRI, with Chinese disbursements peaking at US$ 80 billion in 2017 (see Figures 1-3). Reflecting fiscal austerity and commercialization among the traditional donors, the heavy lifting was outsourced to private finance, following the BTT framework. The PGII's pledge to mobilize up to US$ 600 billion over five years was based on ‘leveraging private sector investments’, with the White House (2022) claiming that ‘millions of [public] dollars can mobilize tens or hundreds of millions in further [private] investments and tens or hundreds of millions can mobilize billions’. But, as noted, private capital is largely disinterested. BTT's poor record was well-known when the G7 announced the PGII (Bernards, 2024). This suggests that, again, Western donors adopted a performative approach, talking up their competitive ‘offer’ to the Global South without committing the resources needed to make a real difference.

ODA Spending on Infrastructure (Constant 2022 US$m) Source: OECD-DAC (n.d.a)

Infrastructure Share of ODA Source: OECD-DAC (n.d.a)

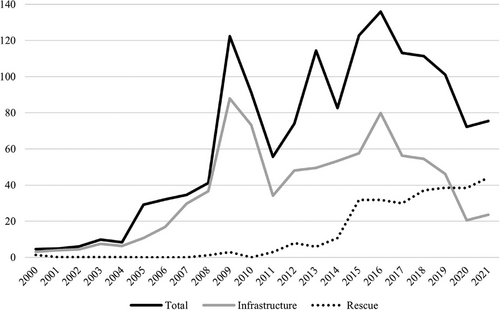

Chinese Overseas Development Financing: Grants and Loans (Constant 2021 US$bn) Source: Custer et al. (2023)

Domain 5: Declining ESG and Debt Sustainability Standards

Finally, traditional donors’ commercial turn had been undermining ESG and debt-sustainability standards long before the Trump administration expressed its scorn for climate aid. The DAC has long prided itself on defining ‘best practices in development cooperation’ on everything from the environment to gender, which member states should follow and report against (OECD-DAC, n.d.b). Together with the UN, it has also developed ‘impact standards for financing sustainable development’ to guide private SDG financing (OECD and UNDP, 2021), and guidelines on issues like tied aid. Traditional donors have also developed debt sustainability norms through the Paris Club and the IMF and World Bank's Debt Sustainability Framework, which limit developing countries’ external borrowing (Laskaridis, 2020). Chinese development financing is often criticized for eschewing such standards: 53 per cent of its overseas lending supports projects with significant ESG risk and China stands widely accused of unsustainable lending causing widespread debt distress (Parks et al., 2023).

However, traditional donors’ commercial turn is eroding standards. Their aforementioned shift from grants to loans is increasing developing countries’ indebtedness. Mobilizing private financing also draws them into global shadow banking, requiring high-yield public debt instruments and expensive central bank liquidity and insurance operations (Musthaq, 2021). DFIs’ reliance on FIs for onward lending also undermines ESG standards. As of 2017, FIs delivered 30–56 per cent of major DFIs’ activity (Donaldson and Hawkes, 2018: 7). Concealed by commercial confidentiality, FIs’ lending ‘neglect[s] principles and standards DFIs have put in place to ensure greater accountability after years of learning’ (Kenny, 2020b: 2). As Oxfam (2012: 6) states: ‘Scrutiny of what DFI funds accomplish in terms of social and environmental standards largely ends once funds are provided to an FI’.

In sum, we see growing convergence in every area typically portrayed as distinguishing Northern donors’ practices from China's. Yet, far from constituting a forceful attempt to compete with China by providing a more attractive ‘offer’ to developing countries, convergence is powerfully constrained by (‘mutated’) neoliberalism, with governments resorting to fudging and inflating their development contributions.

CHINA'S CONVERGENCE WITH TRADITIONAL DONORS

China has also converged with traditional donor practices in important, though more limited, ways. In the first three areas in Table 1, change has been minimal: Chinese financing remains opaque; most lending is non-concessional; and the ODA/OOF distinction remains blurry. However, China's infrastructure lending has collapsed (see Figure 3), with development cooperation refocusing on so-called ‘small but beautiful’ projects, governance, capacity building and cultivating consent for China's economic presence, bringing it closer to traditional donor programming. China's ESG and debt sustainability standards have also tightened, though implementation remains problematic. Rather than mobilizing more resources to compete fiercely with traditional donors in the South's favour, China is adopting a more risk-averse approach, reflecting Chinese development financing's commercial orientation.

Explaining Chinese Convergence

Chinese development financing's rise and fall can be explained by the shifting fortunes of the primarily commercial actors and motives driving it. Although Chinese leaders, diplomats and strategists undoubtedly hoped to benefit geopolitically from the BRI, this initiative and its antecedents were primarily driven by economic imperatives and organized on commercial lines, reflecting their role in promoting China's own ‘late development’ (Chen, 2024). The ‘going out’ policy of 2000 encouraged Chinese companies to seek overseas markets to surmount domestic market saturation and industrial overcapacity. Supporting these firms is the core international mission of Chinese policy banks, whose loans account for three-quarters of Chinese international development financing (Parks et al., 2023: 3). China's international aid programme was also configured to benefit Chinese firms through tied aid and accordingly was, until recently, administered by the Ministry of Commerce. China's policy banks are themselves commercial actors, raising their capital mainly through domestic bond sales to commercial banks and required to make profits (Chen, 2024). The imperative of externalizing surplus capacity and capital intensified post-GFC, as Western demand for Chinese exports declined. The BRI, and the associated outbound lending boom, was primarily intended to address these and other structural challenges in China's domestic economy (Jones and Hameiri, 2020).

The subsequent rise and fall of Chinese development financing primarily reflect changing global economic conditions and often associated external pushback. Initially, many Southern governments eagerly contracted Chinese loans and companies to undertake projects spurned by Western donors and firms. Their capacity to borrow, and Chinese banks’ willingness to lend, reflected four main factors. First, earlier Western debt forgiveness had freed up borrowers’ balance sheets. Second, high commodity prices (reflecting Chinese industrial demand) generated expectations of future income to repay loans. Third, although Chinese banks lent primarily at commercial rates (circa 6 per cent), the official interest rates upon which they were based were at historically low, stable levels, due to post-GFC quantitative easing. Fourth, risk–return calculations were often misguided on both sides, compounded by fractured, poor and corrupted governance (Jones and Hameiri, 2020). Chinese banks substituted robust feasibility and risk assessments and Western-style conditionalities with commercial-style contracts that incentivized repayment and provided resource or cash collateral (Parks et al., 2023).

However, China's lending boom quickly faced two main challenges. First, Western pushback, including ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ accusations, seemingly supported by revelations of high-profile projects going sour, dented Southern enthusiasm. Over 2017–19, Chinese regulators responded by tightening outbound investment and lending rules, and investigating corruption, further depressing lending (Carmody et al., 2022). Second, global economic conditions changed. The winding-down of quantitative easing appreciated the dollar, increasing debt-servicing costs and precipitating debt crises for countries like Sri Lanka, joined by many others following the COVID-19 lockdowns and interest rate hikes. Chinese lenders, primarily concerned with recouping their funds, have acted as ‘yield-maximising investment portfolio manager[s]’ (Parks et al., 2023: 46, original emphasis). They have seized cash collateral, restricted fresh lending, and switched to emergency loans to allow major debtors to keep servicing existing debts (see Figure 3), while battling rival creditors in restructuring talks to minimize their losses (Hameiri and Jones, 2024b). Consequently, as the second Cold War intensifies, rather than mobilizing to compete more fiercely over the Global South, Chinese development financing is being retrenched, reflecting resource constraints and commercial risk aversion. These developments have driven greater convergence with traditional donor practices through the de-privileging of infrastructure and tightening of ESG standards, as detailed below.

China's Infrastructure Focus Dwindles

As Figure 3 indicates, the quantity and focus of Chinese development financing have recently transformed. Total disbursements have nearly halved since the 2016 peak. By 2021, emergency lending — mostly central bank currency swaps — had surged to over 58 per cent of disbursements, while infrastructure commitments fell 70 per cent, to just 31 per cent of total lending. As policy banks have retrenched, commercial banks now account for roughly the same proportion of Chinese outbound lending, around 22 per cent (Parks et al., 2023: 3). These lenders are also being more risk averse, notably by syndicating their loans with more experienced foreign lenders with more robust due-diligence processes. Around half of Chinese non-emergency lending to developing countries is now syndicated, with 80 per cent of syndicates involving Western commercial banks/MDBs (Parks et al., 2023: 110–12). China is also experimenting with PPPs for similar reasons (van Wieringen and Zajontz, 2023). Repayment capacity has become China's critical ‘conditionality’: 95 per cent of project lending now flows to countries at lower default risk, principally MICs (Parks et al., 2023: 73, 108).

Chinese development policy has also broadened beyond infrastructure and loans, in ways that begin to touch upon recipients’ domestic politics. Like the ‘small but beautiful’ slogan, this is likely an attempt to compensate for dwindling financing by emphasizing less risky and costly offerings, indicating a continued desire to compete with the West, but — like the West — without additional resourcing. Accordingly, China's 2021 Development White Paper identifies eight areas for development cooperation, overlapping substantially with the SDGs: poverty reduction, food security, health, education, gender equality, sustainable and innovation-driven growth, climate and infrastructure, now just one focus among many (UNDP, 2021). The sections on humanitarian assistance and supporting growth also echo mainstream practice — for example, people-centred engagement, gender equality, focusing on the most vulnerable, enhancing local capacity, governance and technology — and emphasize multilateral cooperation, unlike the BRI's bilateral approach. This, plus other innovations in aid practices and governance, marks convergence with DAC approaches (Carmody et al., 2022; Chen, 2024; UNDP, 2021).

These changes also likely reflect growing Chinese recognition that some of its projects have failed (sometimes greatly damaging China's reputation) due to partner countries’ inadequate governance, requiring greater Chinese intervention — which, again, suggests convergence with the long-standing Western focus on developing countries’ internal arrangements, albeit not on substance. Although China ostensibly champions sovereignty and non-interference norms, in practice, it is increasingly reaching beyond its borders to secure its economic interests (Zou and Jones, 2020). This manifests in its development activity through expanding work on capacity building and governance. These are focal points for China's recent White Paper as well as its Global Development Initiative, Global Civilization Initiative, and Global Security Initiative, as China partly moves beyond infrastructure megaprojects (Wei, 2023).

Capacity building is a long-standing term in Chinese development cooperation, but it is reorienting to shape recipients’ internal governance. Earlier phases included industrial capacity building for ideologically aligned states, and training in the use of Chinese-built infrastructure and technology. However, since 2012, China has focused on sharing experience from the ‘modernization of [China's] national governance system and capacity’ (Wei, 2023: 122). Its training now covers social and political issues, in areas such as the rule of law, accountability, human rights and environmental protection, that China hitherto avoided as too interventionist. The 2021 White Paper makes ‘improving [developing countries’] capacity for governance, planning and economic development’ a particular focus, noting, for example, that ‘39 senior planning consultants’ had been despatched to various countries ‘to help formulate plans, policies and regulations’, while 31 states agreed memoranda on help to ‘streamline administration, delegate powers, improve regulation, and strengthen services’ (SCIO, 2021: 35–36). This is arguably about strengthening the context surrounding Chinese projects to increase their success. Training materials still openly ‘promote international project cooperation and technological product exports’ (Yau, 2024).

Despite converging with the West by focusing on developing countries’ internal governance, unsurprisingly, China's training materials reflect its own authoritarian approach, limiting convergence on substance (Yau, 2024). Moreover, because China still eschews conditionality, recipients have limited incentive to apply what they learn. Nonetheless, Chinese aid has funded training on topics familiar to Western donors, including gender equality, protecting ethnic minorities and limiting discrimination, and environmental conservation. Furthermore, Chinese training is often poorly suited to recipients’ conditions, does not reach the right people, and is of dubious impact — charges also levelled at Western programming (Wei, 2023: 128–29, 134–35). As with its lending splurge, China appears to be on a similar learning curve to Western states, albeit many years behind, reflecting its ‘latecomer’ status in international development (Chen, 2024).

China is also converging with traditional donors by using aid to pursue ‘soft power’, cultivating consent for Chinese leadership and economic activity beyond its historically narrow focus on ruling elites. Enduring examples include establishing Confucius Institutes and providing thousands of scholarships to developing countries (Carmody et al., 2022: 211–13). More recently, state-backed Chinese NGOs and religious associations have engaged their foreign counterparts to build ‘people-to-people bonds’, while Chinese firms’ corporate social responsibility activity has expanded to appease local communities (Zou and Jones, 2020). Although limited and often unsuccessful, these efforts indicate greater attempts to shape socio-political conditions in developing countries to favour Chinese interests, echoing a long-standing Western practice.

The 2024 Forum on China–Africa Cooperation illustrates China's convergence with the West, including the pursuit of eye-grabbing headlines while limiting resource commitments. China pledged RMB 360 billion (US$ 50 billion) in ‘financial support’ for Africa over three years. However, 58 per cent of this comprised credit lines for Chinese exports; 19 per cent would involve ‘investment by Chinese companies’; and 22 per cent (circa US$ 3.6 billion annually across the entire continent) is unspecified ‘assistance of different types’, possibly ODA-like allocations. Notwithstanding vague pledges to support ‘thirty infrastructure projects’, the ‘ten partnership initiatives’ are dominated by cheaper, less risky commitments: 1,000 ‘small but beautiful’ livelihoods projects, trade liberalization, training and ‘people-to-people exchanges’ (China Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2024). Despite moving into areas previously favoured by Western donors, then, China remains very cautious about increasing expenditure on aid. This makes it unlikely that Beijing will fill the gap left by USAID's destruction, beyond high-profile moves to gain publicity at Washington's expense.

Improving ESG and Debt Sustainability Standards

The second area of convergence with DAC practices is China's efforts to improve ESG and debt sustainability, largely to avoid commercial losses and diplomatic blowback. While similarly incipient, convergence here also indicates China's steep learning curve.

Chinese policy makers have engaged in two major rounds of regulatory tightening in response to criticism of their international development activity (Jones and Hameiri, 2021: 177–78). The first, around 2007–08, responded to accusations of ‘colonialism’ in Africa in the mid-2000s, generating guidelines around environmental protection and environmental and social impact assessments. The second, in the late 2010s, reacted to attacks on the BRI, some propagandistic (e.g. baseless claims of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, see Jones and Hameiri, 2020), many reflecting real problems. Due to lax oversight, the number and value of Chinese overseas projects exposed to significant ESG risks had increased from 17 projects valued at US$ 420 million in 2000 to 1,693 worth US$ 470 billion by 2021, with project cancellations surging from zero to 94 projects worth US$ 56 billion over that period (Parks et al., 2023: 2).

Chinese regulations have consequently been tightened considerably, including by incorporating international standards. In 2017–19, the China Banking Regulation Commission, the National Development and Reform Commission, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, and the Ministry of Commerce issued tougher guidelines on lending and overseas projects. In 2020, China and eight MDBs established the Multilateral Centre for Development Finance to implement the G20 Quality Infrastructure Principles and increase the ‘application and enforcement of accredited IFI [International Financial Institution] standards’ to address ‘quality and sustainability challenges impacting cross-border infrastructure and connectivity’ (MCDF, 2024). In 2021, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, a major shareholder in China's policy banks, announced it would adopt MDBs’ ESG criteria from decision making to post-investment management. China and the EU developed ‘Common Ground Taxonomy’ on environmentally sustainable investments, which has been incorporated into Chinese domestic regulations (Parks et al., 2023: 122–25, 164). These rule changes have been accompanied by anti-corruption crackdowns, including purges of top policy bank officials and the despatching of Central Commission for Discipline Inspection teams to investigate overseas projects (Kumar, 2024).

Consequently, ESG standards have improved considerably, albeit from a low base and with commercial banks outperforming the policy banks. The annual share of lending exposed to serious ESG risk fell from 65 per cent in 2013 to 54 per cent in 2014–17, to 47 per cent in 2017–21, and to 33 per cent in 2021, although risks from recent lending may yet manifest (Parks et al., 2023: 133). By 2021, 57 per cent of China's overseas infrastructure projects by value had strong de jure ESG safeguards, aligned with DAC standards, versus 0 per cent in 2001; de facto risk mitigation rose more modestly, covering 18 per cent (ibid.: 4, 151–52). The bulk of improvements likely expresses commercial banks’ growing share of overseas lending. Through syndication, these banks effectively outsource due diligence to more experienced and better-regulated partners, improving standards. Commercial banks syndicated 84 per cent of their loans to developing countries in 2021, versus the policy banks’ 36 per cent (ibid.: 110–12). Hence, standards may slip if policy bank lending resurges. Higher standards will arguably benefit those developing countries that do receive projects from China. However, given Chinese lenders’ growing risk aversion, total flows have nonetheless collapsed. Rather than competing fiercely with Northern donors, they seem set to focus on fewer, safer projects in less-risky countries.

CONCLUSION

This article has argued against accounts depicting traditional donors as the embattled, status-quo defenders of development norms and China as a revisionist challenger. Across the five areas typically identified as major differences between DAC donor and Chinese practices, we have shown that Western behaviour is becoming more like China's, while Chinese practice is converging with Western conduct in two areas, shifting focus away from infrastructure and tightening standards. While the degree of convergence should not be overstated, a crude binary is unsustainable, as is any account that exclusively emphasizes the ‘Southernisation’ of Western practices.

This analysis has significant implications for understanding the ‘second Cold War’. While the West and China clearly want to compete with one another, the constraints of their respective models mean they are not making generous offers to developing countries, which would empower the latter to pick and choose and pursue autonomous development pathways. The dominant theme on both sides is retrenchment. Western donors refuse to increase fiscal allocations for ODA, relying on ‘mobilizing private finance’ instead, and weakening DAC rules to facilitate this, thereby converging with Chinese practices. Since private capital refuses to be ‘mobilized’ at anything like the scale needed to address the SDGs, Western governments weaken DAC rules to exaggerate their development contributions, cultivating an image of generous competition with China, without real substance. Trump's destruction of USAID suggests that, at least in the US, even the pretence of generosity is perhaps gone.

Meanwhile, China has reined-in its development financing, tightening lending conditions, prioritizing repayment of existing loans, grabbing cash collateral and refocusing on ‘small but beautiful’ projects. This almost certainly reflects reactive policy learning after irrational exuberance led Chinese fingers to get burned in many developing countries. But these changes are primarily intended to protect Chinese lenders’ bottom line, reminding us that the bulk of Chinese development cooperation has never been selfless aid, exclusively benefiting recipients, but rather ‘win-win’ commercial activity designed to enrich Chinese businesses. China may lack the legacy of global imperialism that dogs many Northern donors, but its banks are behaving much like Western lenders to the Global South in the 1980s (Chen, 2023). The profit motive and attendant risk aversion are driving further Chinese convergence with Western practices. The triumph of profit motives on both sides means overall development financing is falling. Commercial logics and associated risk aversion mean that, while safer markets — predominantly MICs — will continue to receive (diminished) flows, poorer countries will lose most. Further research could investigate which countries and projects remain favoured and whether/which donors can still offer more generous terms in specific, geopolitically sensitive cases.

Overall, our study challenges expectations that the Global South will benefit from rising geopolitical rivalry. Perhaps based on stylized versions of Cold War history, in which cunning Third World leaders played both sides to extract aid and other benefits, this perspective overlooks the darker side of the Third World's experience of the first Cold War: violent decolonization struggles, external interventions, subversion and regime change, proxy wars, genocide and the crippling 1980s debt crisis, which terminated state-led development for many (Prashad, 2007). It also overlooks the nature of the second Cold War's protagonists — themselves reshaped by neoliberalism and its mutations — and their struggle. The first Cold War was a battle ‘for the soul of mankind’ between rival social, economic and political systems (Leffler, 2008). The second Cold War is a struggle between national units within globalized capitalism. Both sides cling to their respective models — ‘mutated neoliberalism’ in the West, commercialized ‘state capitalism’ in China (Alami et al., 2024) — exhibiting little capacity for fundamental reform. This conditions their global competition: narrow self-interest, risk aversion and profit motives abound, limiting their offer to the Global South.

Biographies

Shahar Hameiri ([email protected]) is a professor in the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland, Australia, and Research Associate at the Second Cold War Observatory (secondcoldwarobservatory.com). His research currently focuses on the political economy of US–China rivalry. See https://polsis.uq.edu.au/profile/1600/shahar-hameiri for further information.

Lee Jones (corresponding author; [email protected]) is Professor of Political Economy and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London, and Research Associate at the Second Cold War Observatory (secondcoldwarobservatory.com). His current research focuses on the political economy of US–China rivalry. See www.leejones.uk for further information.

REFERENCES

- 1 Unlike Western states, Japan never vacated this space, remaining a strong competitor with China.