Rice Margins Under Climate Change: Labour and Knowledge in Mangrove Rice Networks in Guinea-Bissau

ABSTRACT

The effects of climate change add to the challenges facing those with rice-based livelihoods in West Africa. This article presents a long-term ethnographic case study in southern Guinea-Bissau where, in contrast to other reported cases in the region, uncertainty regarding the future of mangrove rice production overlaps with efforts to rehabilitate abandoned mangrove rice paddies. Agricultural knowledge is produced, renewed and transmitted along with the construction of site-specific, techno-ecological hybrids needed for water management in rice fields. This article analyses the role of communal, reciprocal and contract labour in the circulation of knowledge between villages with historically stable rice production (rice refugia) and villages where production has been discontinuous (rice margins). Knowledge circulation and experimentation are key to local adaptation to climate change and climate resilience programmes can play a role if they are able to adapt to current needs, for instance, by considering decentralized funding strategies. By promoting the exchange of services and goods, decentralization of funding can facilitate the redistribution of knowledge and labour, particularly if rice refugia, as regional knowledge repositories, participate in the recovery of rice production in rice margins. These connections revitalize and strengthen regional rice knowledge networks and their ability to confront climate change.

INTRODUCTION: RICE CENTRALITY UNDER CONTESTATION

The centrality of rice to the social, political, economic and religious realities of coastal peoples in West Africa has been described in studies carried out in the homelands of the Diola, Baga and Balanta in modern Gambia, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau and Guinea (Bivar and Temudo, 2014; Davidson, 2015; Linares, 1981; Ribeiro, 1989).1 One of the most productive rice farming systems in these coastal regions is on the inland side of mangrove forests, where swathes of mangrove swamps are cleared and converted into rice paddies. The establishment and maintenance of these mangrove rice paddies requires specific skills and knowledge and considerable labour to ensure effective water management through a system of dikes, ditches and sluices. These site-specific technological arrangements protect the development of rice plants from the unrelenting rhythms and the highest amplitudes of the estuarine tides and from the potentially devastating effects of rainwater flooding.

In most of these coastal communities, however, the centrality of rice has become subject to increasingly precarious conditions. Volatile political, economic and environmental conditions have combined to undermine both the sturdiness and stability of the water management infrastructure on which mangrove rice production depends and the social and communal structures necessary to build and maintain them. Countless villages have seen their mangrove rice production suspended, interrupted or only rudimentarily maintained.

In an ethnographic study among the Diola people in the village of Ensana, located in Suzana, Cacheu region in northern Guinea-Bissau, Joanna Davidson (2015) explains how rice — the sacred and totalizing element of life — has become a less and less viable crop. The online documentary ‘Zé Wants to Know Why’ (Divergente, 2015) highlights how climate change is affecting life in Elalab, another village in the same region, particularly the increasingly challenging task of preventing seawater from flooding rice fields. The village of Jobel,2 in the homeland of the Diola people, is facing displacement due to seawater flooding, a reality studied by Santos and Mourato (2022), Temudo and Cabral (2021) and Temudo et al. (2022). There seems to be a consensus among these authors that the effects of climate change are exacerbating long-standing tensions between Jobel and other villages. Also, in north-west Guinea-Conakry, Ramon Sarró (2021) describes major transformations of social life, agriculture and landscapes in the homeland of the Baga, where people are known for their deep-rooted mangrove rice farming skills and knowledge (Fields-Black, 2008). Near the city of Kamsar, lifeworlds based on mangrove rice are imperilled by more frequent seawater flooding (Sarró, 2021).

These peoples, who have based their livelihoods, social lives and worldviews on mangrove rice and who live in what were once called ‘rice societies’ (Davidson, 2015), are being pushed toward uncertain futures. Hawthorne's (2017: 499) review of Joanna Davidson's Sacred Rice (2015) poses the question: ‘Is there something unique about the present period? Or has life in the marshy lowlands of Guinea-Bissau long presented anxiety-laden challenges?’. Different narratives, memories and imaginaries remain in contestation when attempting to understand the extent to which climate change is leading to the disintegration of mangrove rice production as a mode of life.

A report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023: 1), notes that, ‘Relative sea level has increased at a higher rate than global mean sea level around Africa over the last three decades’. Guinea-Bissau, in particular, has a high coastal vulnerability index (Dada et al., 2024). The uneven distribution of rainfall and fast accumulation of rainwater runoff (Garbanzo et al., 2024; Mendes and Fragoso, 2024) add further challenges to the stability of dikes and other dam structures that protect the rice fields. Despite these challenges, in most regions of Guinea-Bissau, rainfall remains suitable for mangrove rice production,3 and hope lies in the fact that mangrove-based production of rice has been historically threatened by flooding, necessitating a long-standing tradition of constant adaptation. Efforts to protect rice fields from the spring tides appear throughout the historical record. For example, de Almada (1961: 36) notes that burst dikes were described in one of the first written accounts of the West African coast in the 16th century: ‘[they] make their rice fields in those lalas [savannah-dominated floodplains], and make ditches of earth because of the river that might come, even though the river often breaks them and floods the fields’. During the late colonial period, Espírito Santo (1949: 198) said that in Tombali, farmers ‘take care of ploughing of the soil, defending it with immense energy against, on the one hand, the rage of the tides, and on the other, the excess of pluvial water’. Rodney (1970: 17) mentions the ‘small canoes used by the Diolas to traverse their flooded rice fields’ in an early portrayal of the considerably flooded landscape in the Cacheu region. Burst dikes were also reported in the 1980s and 1990s by Gonçalves (1998) and Vieira (1989). The risk of flooding is inherent to the mangrove rice system, and one wonders what environmental and socio-economic conditions can ensure the reproduction of life in mangrove rice societies and for how long.

CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION AND THE LEGACY OF FOREIGN AID

The loss of land due to rising sea levels is and will continue to be harmful to the livelihoods that are connected to it. It has been broadly argued, including at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference or COP27, that peoples and places identified as most vulnerable to rising sea levels have not significantly contributed to the fossil fuel emissions leading to global warming (Pflieger, 2023; Roberts, 2001). Rather, they have been integrated in the economies of capital accumulation, which benefit from the energy extracted from burning fossil fuels, as sources of labour and resource extraction. Additionally, several other historical and colonial layers of social injustices, as described below, are relevant to the case of Guinea-Bissau.

The urgent and immediate need for new, additional, predictable and adequate financial resources to assist developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in responding to economic and non-economic loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events, especially in the context of ongoing and ex post (including rehabilitation, recovery and reconstruction) action. (UNFCCC, 2022: 2)

If it is true that the Loss and Damage Fund has the potential to address problems derived from climate change in countries like Guinea-Bissau, it is also important to recognize that its operationalization will depend on existing structures and practices developed by previous international programmes that have been identified as priorities in development (for example, biodiversity conservation, education, healthcare). In particular, the context of foreign aid after the 1990s is highly influential to the management of current and future climate change adaptation programmes. If the goal is to compensate or repair livelihoods destroyed by the effects of global warming, it does not seem logical or reasonable to accept the Loss and Damage Fund, or any other funding mechanism advertised as a climate change adaptation, without considering the literature on the effects of the so-called foreign aid on the lives of rural peoples in recipient countries.

A study by Herzer and Nunnenkamp (2012: 254) focusing on the effects of foreign aid in 21 countries from 1970 to 1995 points out that programmes intended to improve the quality of life of impoverished people not only failed to achieve their objectives but even reproduced and expanded inequality. From the 1980s, an emphasis on community participation was used to consolidate the legitimacy of development programmes in Africa, Asia and Latin and South America. Many NGOs were created under this umbrella and promoted as an alternative to the failed top-down approaches to development. However, by the mid-2000s, substantial literature had already been established (e.g. Hearn, 2007) showing how approaches to development continued to be dominated by donor models and were largely top-down, agenda-driven and expert-led. In addition, community participation had become ritualistic (e.g. Flint and Natrup, 2014) and instrumentalized (e.g. Pfeiffer, 2005; White, 2010).

In Guinea-Bissau, the foundation of village committees in rural areas during the struggle for independence (1963–74) was envisioned by Amílcar Lopes Cabral, founder and secretary-general of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde or PAIGC), who helped lead Guinea-Bissau to independence as a means to enable peasants to participate directly in the making of national political decisions (Washington, 1980). However, after independence village committees began occupying increasingly peripheral roles (if any) in the decision-making processes emerging from development agendas. Voices, agency and organization of rural peoples in development processes were replaced by non-governmental intermediaries that supposedly would be able to represent them. Earlier works by Galli (1990), Sousa et al. (2017) and Temudo (2012, 2015) have shown the limited, or even negative, effects of development and conservation programmes on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers.

Environmental-driven programmes, in particular, have been described as undermining local political authorities and contributing to the alienation of land essential to the reproduction of peasant modes of life. Except for a few examples in which farmers had direct access to funding (e.g. Sousa et al., 2021), NGOs and the state have been accused by farmers of using farmer associations as structures to capture funds for development projects with limited benefit to their lives (Temudo, 2015). In Senegal, Hiraldo and Böhm (2023) show how the implementation of policies aimed to mitigate the effects of climate change have worsened the already vulnerable situation of local peoples.4 Effective responses to climate injustice must address the roots of social injustice, otherwise policies directed at responding to the climate crisis will further entrench gendered, race- and class-based historical and contemporary inequalities. As noted by Borras and Franco (2018: 1320), ‘agrarian justice and climate justice have become dialectically linked: one cannot exist without the other’ and, in the face of climate disruption, peasant modes of life must be protected to ensure food sovereignty.

INDIGENOUS AGRICULTURAL KNOWLEDGE AND CLIMATE JUSTICE

Climate justice has been unpacked into several dimensions, one of which is recognition justice, which corresponds to the recognition of the knowledge, identities and values of rural and Indigenous peoples (Jones et al., 2024). Without this epistemic recognition it is not realistic that rural peoples can benefit from compensation programmes such as the Loss and Damage Fund mentioned above. Together with relational, procedural, distributive and restorative justice (see, for example, Jones et al., 2024; Parsons et al., 2021), recognition justice involves the consideration of different forms of governance. In the context of mangrove rice farming in Guinea-Bissau, the construction of water management infrastructure is immersed in local cosmopolitics and in the social organization enabling the (re)production of knowledge along lines of kinship, age and inter-village relations. In other words, processes of knowing coastal ecologies, acting upon them and organizing social life around them provide the basis for water governance, meaning that knowledge, ecologies and governance are indissociable. In fact, the importance of Indigenous agricultural knowledge in water management for climate change adaptation has been described for contexts such as Iran (Ghorbani et al., 2021), India (Laishram et al., 2020), Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan (Rivera-Ferre et al., 2021), among others. A recent study documented the importance of Indigenous knowledge and local knowledge to water management adaptation to climate change across Africa, although only 10.4 per cent of the African governments included Indigenous and local knowledge in their adaptation planning (Zvobgo et al., 2022).

Even if Indigenous knowledge systems and governance are recognized as meaningful to address ecological crises (Ratima et al., 2019), it is argued that epistemic recognition alone fails, and can even serve to maintain dispossession, if hierarchies and structures of power remain untouched (Coulthard, 2014). Considering this critique, together with a focus on knowledge, our analysis also discusses how processes of knowledge production and circulation can benefit from a change in the access of rural peoples to climate adaptation funding.

The research questions we address in this article include the following. How do different local histories of rice production contribute to the recovery of production regionally? How do knowledge and labour circulate regionally in processes leading to the recovery of mangrove rice farming? Why is the way knowledge circulates important for an effective use of external funds in the recovery of mangrove rice production under climate change? These questions will be explored by mapping the connections that allow for the circulation of knowledge and labour among villages in a multi-sited ethnography in southern Guinea-Bissau.

The article is structured as follows. The next sections explain the methodology and fieldwork and briefly describe the history of rice abandonment and rice persistence in the Tombali region in southern Guinea-Bissau. The article presents a multi-sited ethnography which focuses on the pre-existing and emerging connections among villages and which provides grounds for the rehabilitation of rice fields today. The article concludes with specific policy recommendations. These will be presented in detail below; in brief, we argue that: (1) rice production is linked to regional networks established among villages and cannot be understood as a sum of unconnected places; (2) places of marginal and/or interrupted rice production are intermittently part of the network and important for technological experimentation under climate change; (3) adaptation must be recognized as a long-standing process based on individual and collective learning where both successful and unsuccessful rice technology recovery attempts play important roles; and (4) funding efficiency can be established by providing direct access to funds and/or access to goods and services that allow for local responses to specific micro-environments and the social conditions of different villages and rice fields. Overall, this article contributes to the body of literature discussing the ways in which climate change adaptation interventions can be rooted in redistributive logics rather than in strategies that reinforce or create new vulnerabilities (Eriksen et al., 2021; Taylor, 2015).

METHODOLOGY AND FIELDWORK: FOLLOWING RICE CONNECTEDNESS

The empirical work presented in this article can be described as an ethnography of village-based connections in Cubucaré (Tombali region), homeland to the Nalu people, in southern Guinea-Bissau. We have followed connections established by kinship, reciprocity and labour contracts that are relevant to the circulation of mangrove rice knowledge and technology. Using the village of Caequene as a base, we engaged in multi-sited ethnography built from the connections identified between different micro-geographies of mangrove rice farming.

To explain how this multi-sited ethnography emerged, it is important to present succinctly how labour and work are organized in the region. At the scale of the moransa (patrilineal lineages that may include several houses — house is patrilocal), women and men perform tasks based on gender (Frazão-Moreira, 2009). A moransa includes different fugon, which has been described as the basic economic unit of production (Frazão-Moreira, 2009; Oliveira et al., 1993),5 grouping together people who share production commitments and benefit from common harvests. To maintain the workforce, elders may prevent young people from funding their own fugon to prevent labour scarcity (Frazão-Moreira, 2009).

At the village level, agricultural working groups are often organized by households or by age and gender. These working groups may labour collectively on a reciprocal rotating schedule or they may perform daily-wage activities for specific households (including in other villages). The monetization of labour, especially of young people's labour, together with urban migration have been described as affecting the labour available for mangrove rice farming (Bivar and Temudo, 2014; Infande, 2023) and attempts to reproduce mangrove rice farming have become heavily dependent on the motivations of young people. Youth work groups of one village can be hired to work in another village, which is another context that allows for inter-village knowledge sharing.

Land tenure in the region, including of mangrove rice fields, is patrilineal. In cases of long-term abandonment of rice fields, the mangrove regrows. If swamps are reactivated for rice production, the mangrove must be cut again and land rights are renegotiated. Previous land tenure is considered, but the division of land is updated to the new situation. This rearrangement is done according to the labour that contributed to the construction of the main dike — central to the reactivation of mangrove rice production by enabling the control of salinity inside the future rice fields. People participating in the construction of the main dike and representing their own fugon have access to rice parcels in the newly created rice fields. When land tenure is settled and the productive phase begins, plots to grow rice can be borrowed if the owners do not plan to use them all. Although largely patriarchal in terms of land tenure and access, matrilineality is also socially recognized as important for rituals, redistribution of harvests, childhood education (Frazão-Moreira, 2009) and labour distribution (a person can be asked to visit their maternal uncle in his village to help with agricultural work). These inter-village and family-based engagements around agricultural work are important to knowledge transmission.

Both local and regional networks through which knowledge is created and transmitted contribute to the similarities and diversity observed in rice technology along the coast of Guinea-Bissau and beyond.6 For example, it has been referenced in the literature that mangrove rice cultivation in the Nalu homeland resulted from the migration of Balanta people to the south of Guinea-Bissau (Frazão-Moreira, 2009) in the 1920s (Carvalho, 1949).7 Some scholars also attribute the earlier influence of the Baga peoples from northern Guinea-Conakry to the development of swamp rice in Tombali by the Nalu people (Sousa, 2017).8 The idea of micro-scale connectedness is key to this article and emerged from our shared experiences with local rice farming histories in Cubucaré.

Our team consisted of two researchers (the corresponding author and third author) and a mangrove rice farmer (second author). The work presented here resulted from a shared ethnography of rice production during which we documented efforts to rehabilitate mangrove rice production in several villages in Cubucaré. It is impossible to provide detail about the methodology of this work without providing an explanation about the long-term relationship of work and friendship. From 2009 to 2011, during the fieldwork for Joana Sousa's PhD dissertation, co-author Ansumane Braima Dabó was her field assistant, who quickly became a friend and a colleague with whom observations were discussed and perspectives shared. Together they measured crop damage in the village of Caequene (the central village in this article), including in mangrove rice fields, and Dabó helped with establishing contacts with key informants in neighbouring villages and acted as a translator whenever needed. Caequene was Sousa's base and even if she also worked in other villages, she would come back to Caequene to rest and organize field notes. Sousa was hosted by the fugon of Dabo's family. Major life events were shared between the authors, including Dabo's marriage, the visit of Sousa's family, hosted by Dabo and his family, and other episodes of care during times of recovery from disease or accidents. They worked together from 2009 to 2011 and in 2013, 2015 and 2019. In 2013, the three authors of this article combined their efforts during the construction of the main dike in Caequene and Ana Luisa Luz coordinated the production of a collaborative film on the construction during five months (Luz et al., 2015). Finally, in 2016–18, Sousa lived and worked as a university teacher in Bissau, during which time Dabo spent a few months at her house in Bissau. His stays allowed them (together with Luz) to co-write research outputs and allowed him to present the work at universities in Bissau.

In sum, since 2009, we have carried out different activities together, such as conducting fieldwork, showing the documentary film and collaborating at the university. These experiences have allowed us to share perspectives, complicating and adding nuance to the individual analyses and therefore creating a co-produced understanding of reality. During this process we became colleagues in research. Dabo has been a master of osprindadi (the Guinean Kriol for hosting) in Caequene. He patiently translated parts of his world, surrendered to the concerns and challenges of otherness, and became an experienced interlocutor of worlds.

In the writing of texts, the first and third authors of this article received Dabo as their ospri (guest), helping him to decode and demystify the language and meaning of academic publications relevant to their shared interests, and invited him to communicate his experience, knowledge and perspectives through writing and video. We believe that these life-methodologies can contribute to different forms of dialogue and collaboration that are important for social, ecological and political positioning and co-learning in the face of global warming and climate change. A version of this manuscript was first written in Portuguese so that all three team members could contribute to it, and discussions about the content of the article were held in Guinean Kriol. More recently, we have depended on email and social media during the revision process. A final version in Portuguese was also shared and revisions were incorporated.

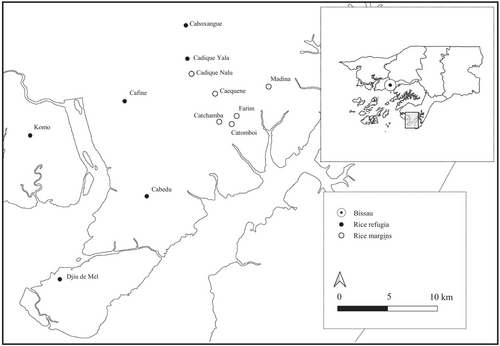

The empirical work that speaks directly to this article began in the Nalu village of Caequene (see Figure 1) in 2017 and 2019. We mapped the relationships established with other villages that allowed for the circulation of labour and knowledge in the context of rice farming, especially in Cadique Yala, Catchamba, Farim and Madina, as well as other cases that we followed less closely. We carried out semi-structured interviews with farmers, both old and young, and in-depth interviews with farmers recognized as having advanced knowledge of mangrove rice farming and we held many informal conversations with farmers while walking through the mangroves and rice fields, which produced a shared narration of the space (Lee and Ingold, 2006). Participant observation was carried out on working days and during the seasonal and daily life routines in rice agriculture, which proffered access to details of practice that evoked deeper histories and knowledge.

Location of the Villages Included in the Study.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

The direction of the interviews was largely determined by the interviewees, although core topics included technological history (for example, dikes, ditches, seeds), types of knowledge (for example, topography, hydraulics, oceanography), diffusion of knowledge (for example, lineages, extended family, age groups, gender), local history of mangrove rice cultivation and concerns about the future. Information was triangulated while interviewing multiple people in connected villages — especially in Caequene, Catchamba Nalu, Farim (all home to Nalu peoples), and Cadique Yala (village inhabited by Balanta people, details will be presented below).

As described above, agricultural tasks and the activities that sustain livelihoods in Cubucaré are gendered, and women and men are responsible for different realms of rice (re)production. The focus of this article is on the knowledge and practices required to instal water management infrastructure such as constructing and/or repairing dikes, digging out or closing canals and installing sluices. These activities are all performed by men. Women assist directly in the closing of canals and participate in the other tasks by providing cooked food and water to drink. Yet the site preparation tasks mainly belong to the masculine dimension of mangrove rice farming. For example, men's knowledge is directed at predicting spring tides, techniques for damming sea canals, topography and the architecture of water systems, among others. Men's labour is directed at the wielding of flat-bladed shovels to prepare fields for planting or using tools like machetes and axes and infrastructure items such as hollowed tree trunks or polyvinyl tubes used for drainage, or sticks of different shapes and sizes to provide structure for the dikes at the sites where seawater canals have been dammed. Consequently, this article is largely the result of an analysis of men's perspectives about mangrove rice farming technology and its transformations. There are limitations to not considering women's perspectives of technology such as their ideas about the interruption and re-emergence of rice production, and the advanced knowledge they hold about seedbeds and transplanting, rice varieties, rice transportation, processing and cooking.9 Similarly, the perspectives of children, who are largely responsible for guarding the rice fields and fishing in rice polders, were also not considered here because these activities escape the focus of the article. Finally, the stories told in this document are open-ended stories (see Tsing, 2015) since the present is immersed in uncertainty.

We identified differences among villages in terms of their relative importance as repositories of experience in rice farming, and from there we mapped the relationships established among them. An analysis of our fieldwork yielded two broad types of villages involved in mangrove rice production: ‘rice refugia’ and ‘rice margins’. A few villages, in many cases home to Balanta people (often not exclusively), have been refugia to rice knowledge and technology in times of crises. Some of these villages, like Bedanda, Cabedu, Caboxangue, Cadique Yala, Cafine and Darsalam, are regional centres of mangrove rice farming and places where mangrove rice has been cultivated despite the political, economic and climatic challenges of the 20th and 21st centuries (and where mangrove rice farming has not been interrupted in living memory).

During the colonial period, centres of rice production were recognized by the Portuguese colonial administration, which led to the installation of administration posts and/or storehouses in villages such as Bedanda, Cabedu, Caboxangue and Cafine, among other rice-producing villages. After independence, the first state office for agricultural research, the Caboxangue Experimental Station (Estação Experimental de Caboxangue), was established in 1977 in Caboxangue to develop and trial rice seed varieties.

Other villages constitute the margins of rice networks — they are on the periphery, but they serve as relevant connecting points among rice producing centres as this article demonstrates. These are often home to Nalu or Balanta communities and, less frequently, to Sosso or Mandinga communities. The phrase ‘rice margins’ describes places marked by interruptions in the production of mangrove rice. These include cases in which production has contracted, (almost) disappeared and then eventually emerged again. When active, rice production at the margins builds connectivity between villages and boosts vitality in the network as a whole by allowing labour and knowledge to circulate.

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF RICE IN CUBUCARÉ

In the 20th century, rice played an important role in the political history of Guinea-Bissau. In fact, the effects of climate change on rice production compound the processes of vulnerabilization, brought about through the control and manipulation of rice production by the colonial administration, the bombing of rice fields by the colonial army, misappropriation of funds and public goods by state elites and the failure of development programmes to promote rice production after independence. This section describes transitions in rice subjectivity in the context of southern Guinea-Bissau, particularly on the Cubucaré peninsula.

In the years preceding the start of the Struggle for Independence (1963–74) and in the same period that PAIGC was founded in 1956, the Front for the Liberation of Guinea and Cape Verde (Frente de Libertação da Guiné e Cabo Verde or FLGCV) accused members of the Council of Government and Trade Chamber of the colonial state of manipulating rice prices and supply as a strategy for forcing farmers to increase production: ‘It is known that this year's harvests would have been enough to feed the people until the next harvest. All was exported to the metrópole and to other countries, and our own farmers are starving and working and suffering again in the rice fields’ (FLGCV, 1960: 1).

During the early 1970s, the colonial administration's control over the rice trade was challenging; it tried to force farmers to sell their rice to colonial enterprises such as Casa Gouveia and Sociedade Ultramarina (Galli, 1995). The FLGCV excerpt quoted above is from a 1960 document denouncing colonial rice exportation policies that resulted in a lack of rice for subsistence in rural areas. In this context, the colonial administration had imported rice and was selling it at 14.3 per cent above the price fixed by the state. The rice supply became so scarce that women had to queue at the doorsteps of storehouses to try to purchase rice and they were routinely subjected to abuse and exploitation in exchange for sustenance (FLGCV, 1960). From the 1930s until the mid-1950s rice was exported from Portuguese Guinea to Europe (Temudo and Abrantes, 2013) and, based on the quote above, then continued until 1960. The micro-history of rice in Guinea-Bissau during the colonial period and struggle for independence, and the social relations it mediated, are yet to be studied in detail.

Throughout the struggle for liberation, rice continued to play a role in the conflict between colonialists and PAIGC, via strategies of diverting or destroying rice production. In the early years of the fight for independence, before the region of Tombali was liberated, the PAIGC guerrilla leader Marga (the nom de guerre of João Bernardo Vieira10) wrote a letter to Aristides Pereira11 describing a military offensive by the colonial army targeting rice fields and stated: ‘These days the Portuguese troops have set fire to almost all the houses and to the rice in the bolanhas12 [rice fields] of the people’. In the same letter, he mentions that 90 tons of rice were intercepted from Casa Gouveia and should be en route to Conakry (Casa Comum, 1971). In regions such as the one where Marga was a commander, rice played an important role in sustaining life and enabling the continuation of the struggle; when destroyed by colonialists, the intention was to increase hardship and dispirit the people.

In 1971, in the liberated zone of Tombali, PAIGC organized rice evacuation brigades (Brigadas de Evacuação do Arroz) that were in charge of collecting rice from farmers and managing rice stocks (ibid.). In these liberated areas, particularly in Tombali, the rice produced could be exchanged for clothes, needles, sandals and soap. The exchange rates were ‘established by the central party leaders on the recommendation of the local cadres … in such a way that the people [were] encouraged to produce more’ (Rudebeck, 1972: 4). In 1971, a report on the region of Catió mentioned that there were no rice scarcity problems among the PAIGC fighters; on the contrary, the concerns were about damage to rice in storehouses (Casa Comum, 1971). At the same time, in Cubucaré and in other areas of Tombali, the report stated that: ‘The spring tides caused considerable damage’ (ibid.: 9) and that the following year ‘would be a difficult one’ (ibid.: 26). Yet, the report mentioned that there was a ‘reasonable participation of the masses in the work in rice fields and orchards’ and that committees will ‘mobilize all people interested in repairing the dikes’ (ibid.).

Given the total control of the southern region by the PAIGC, and the importance of the region for rice production, the Portuguese decided to destroy and bomb parts of the dikes that protected the rice paddies from the tides, in order to limit the potential rice available for the population. … Outmigration led to a lack of labour for agricultural work and several rice paddies were abandoned, more than 50 per cent in some sectors [of Tombali]. (Penot, 1995: 9; authors’ translation from the French)

Independence was unilaterally declared in 1973;14 however, discontent grew in the decade that followed despite the country becoming an international example of a grassroots organization that achieved success with ‘the common determination to build a new non-exploitative society’ (Washington, 1980: 15). PAIGC had promised economic assistance for rural peoples, but ‘the government had moved to monopolize rural trade’ instead (Forrest, 1987: 102). Additionally, neglect of the basic infrastructure needed for peasant production and the concentration of public resources on imports represented clear continuities between the policies pursued by the Portuguese New State (Estado Novo) and the post-independence PAIGC governance (Galli, 1987).

Furthermore, droughts experienced in the Sahel in 1977 and 1979 resulted in a decrease in rice production in the region. The 1980 coup led by Nino Vieira, which ended the Luis Cabral regime (1974–80), was called the ‘rice coup’ due to the ‘serious [rice] shortages not only in the capital but throughout the country’ (Galli, 1990: 56). In 1983, not long after the coup, the shortage of basic needs worsened and President Nino Vieira granted the armed forces the ‘privilege of receiving the initial distribution of all imported rice’ (Forrest, 1987: 109). In a sense, rice production ‘acted as a barometer of producer–state relations, especially in the first ten years of independence’ (Galli, 1990: 55), which until 1989–90 was marked by a substantial decrease.

From 1985, the period of economic adjustment funded by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was also unable to improve rice production. On the contrary, the Structural Adjustment Programme encouraged non-productive rather than productive investment and did not bring the expected economic benefits to agricultural producers. According to Galli (1990: 58), ‘the major beneficiaries [of the funds] have been the members of the state class’. Moreover, as Galli (1990) notes, labour shortages, due to seasonal and permanent migration, further exacerbated the challenging conditions for rice production in the country.

In the 1990s, the advent of multi-party politics and the liberalization of the economy gave rise to a more complex political space, layered with private sector businesses, import–export actors, and national and international organizations acting in different fields. The increasing number of NGOs operating in the country began to build an interface with the rural peasantry which has been criticized ever since (Sousa et al., 2017; Temudo, 2015), including for failing to keep development promises, dismissing farmers’ calls for meetings and undermining traditional processes of decision making.

As a result, according to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) statistics, rice imports increased in the country from 1986 to 2005 although these numbers cannot be separated from the promotion of cashew production.15 In 2013, a World Food Programme report (WFP, 2013) noted that 80 per cent of the households benefited from cashew sales, which were described as having discouraged rice production in the country (Temudo and Abrantes, 2013, 2014). The same report recognized the importance of reinvesting in mangrove rice farming and proposed the inclusion of Food for Work activities, ‘to assist vulnerable populations to rehabilitate rice production infrastructures’, and to promote food security in Guinea-Bissau (WFP, 2013: 7). Later, in 2017, the National Plan of Agricultural Investment gave some weight to the promotion of rice production and aimed to decrease the rice deficit by 50 per cent by 2025 and to produce a national net rice surplus by 2030 (FAO, 2017).

Evidence of abandoned rice fields has also been described by chronological land cover studies (Andrieu, 2018; Temudo and Cabral, 2017), and if trained eyes scan Google Earth images of Guinea-Bissau it is possible to discern the perpendicular lines of old dikes in regrown mangrove forests. Mangrove canopies hide untold stories of past rice production. While walking through the mangrove, among the webs of aerial roots and awash in the estuarine water that cyclically covers the muddy soil, glimpses of eroded ridges also reveal a past that lies latent in the mud. Rice rests in the memory of elders, but younger generations, the protagonists of rice re-emergence under climate change, are scavenging those memories and re-opening the mangrove swamps.

REPAIRS WITHOUT REPARATION

While the history of rice has been shaped by political, social and environmental volatility, the continued existence of mangrove rice production in Cubucaré, and in the Tombali region more broadly, demonstrates the capability of rice livelihoods to persist and even to re-emerge, despite the present challenges. In several villages in Cubucaré, such as Abedaia, Caequene, Cafal Balanta, Cafal Nalu, Cafatche, Cassintcha, Catchamba Nalu, Catomboi, Farim, Madina and Sogobol, rice production ceased or substantially decreased prior to 2013. However, during the period 2013–19, we observed farmers in these communities working to rehabilitate or expand their rice paddies. These villages constitute the ‘margins’ of rice production: they rely on diverse livelihood strategies, their mangrove rice production has been historically discontinuous and they have established connections with other villages — the rice refugia — to reinforce the means and knowledge needed to pursue plans of rice rehabilitation.

As explained above, rice refugia have effective social mechanisms for labour allocation, are repositories of advanced knowledge and have proven more resilient to extreme climatic events. For example, during the rainy season of 2015, several dikes were damaged by the compounding effects of spring tides and strong winds. In the Balanta rice refugium of Cafine, two farmers described how the front dike ruptured in more than 20 places.16 While these events impacted rice production, production never ceased. Another farmer in Cafine described how more than 270 people from the village participated in repairing the dike in 2016, the year after the storm.17 Labour and knowledge are redistributed from these rice refugia to other villages through agreements involving reciprocity, payment or access to land.

Establishing New Rice Connections

In 2013, people in the rice margins village of Caequene built an 800 m-long dike, which was extended in 2017. This construction was locally unprecedented: there had never been as big a dike in the village. Specific, sophisticated and up-to-date knowledge was needed for successful construction. Knowledge was socialized through specific people in the village, the Nalu, a Balanta who has lived in Caequene for several decades and a Balanta farmer from a nearby village. In the village, key advice on technology was mainly provided by a Nalu elder who had advanced knowledge of water engineering and of the cycle of the tides as well as a Balanta elder who was also renowned for his knowledge in these matters, who years earlier had come to Caequene in search of medical treatment, and whose knowledge was transmitted to a few people in the village (Sousa et al., 2014). Crucially, a Balanta farmer from the nearby village of Cadique Yala, who was experienced in building dikes and damming seawater canals, was also involved as an adviser to the construction. This farmer had previously established relations of reciprocity with Caequene as he had been given land there to plant his cashew orchard. Cadique Yala is an historically important rice producing village, and this relationship of proximity and mutual assistance allowed for considerable knowledge transmission and technical consulting during the construction of the dike.

The first construction in 2013 was mainly promoted by a small number of young farmers (locally understood to encompass teenagers and young adults) but the work required the long-term commitment of both youth and elders.18 In August 2017, four years after the construction of the dike, considerable knowledge had been shared between generations and a younger generation of farmers were ploughing the rice paddies alongside the farmers who built the dike in 2013. These younger men had not had experience in mangrove rice farming back in 2013, when the dike was first constructed. It was striking how the connections between mangrove rice and a younger generation of farmers had become established so quickly following the rehabilitation of the dike a few years earlier.19

In 2019, an elder who could no longer work but who was involved in the planning and construction of the dike told us: ‘Hunger chases away young people’.20 ‘Hunger’ (or fomi in Guinean Kriol) is the term used in Guinea-Bissau to describe situations in which people do not have sufficient rice to eat. The elder was establishing a link between the availability of rice in the village and the expectations of young people regarding mangrove rice production itself. This reinforces the idea that rice is important for its own reproduction (see also Ribeiro, 1989). In fact, rice production in Caequene during the period 2009–12 was minimal (documented in Sousa, 2015), but production has been increasing since the construction of the main dike in 2013. Access to direct funding by an association enabled farmers to purchase rice, external labour and tools that were necessary for the construction of the dike.

Since 2013, the dike has ruptured several times, but the farmers were able to fix it, again with the counselling of the farmer from Cadique Yala. The dike broke twice in September 2023 in a section that was less critical to functional water management. These incidents, although highly detrimental to rice (re)production, facilitate knowledge transmission from ‘rice refugia’ to villages like Caequene at the ‘rice margins’. In addition, these small ruptures in the dikes and the continuous maintenance required are opportunities for different farmers and generations to share knowledge, and they provide a safe space for technological experimentation.

Cases from other villages where people have tried to build a main dike for rehabilitating mangrove rice production are briefly presented below. These cases help to illustrate the diverse ways in which knowledge and labour circulate in the region. The first and second cases benefited from mutual help arrangements between villages. In the third and fourth cases, hired skilled labour played a more important role. The outcomes of the efforts to rebuild the dikes were diverse and inform the discussion on the effects of failure in the rice networks as a whole, particularly in the context of climate change. This will be further explored in the last section.

Filling in Rice Margins

Case 1: Redistribution of Labour and Knowledge along Lines of Kinship

On the other side of the banks of the Mabok canal, opposite to Caequene, lies the village of Catchamba. People from Caequene and Catchamba Nalu visit each other regularly and hold direct familial ties through marriage. Marriage21 is a meaningful institution that celebrates ties between moransas and villages, particularly when two patrilineal lineages based at different villages inter-marry in the long term. Ties between villages are also strengthened when children are sent to their mother's original village and educated at the moransa where she was born. In these cases,22 people in different villages see themselves as belonging to a shared social unit — several times we heard the expression ‘we are only one’. This was observed between Caequene and Catchamba Nalu, while Frazão-Moreira (2009) described a similar relation between Catchamba Nalu and Sogobol.23

In 2015, villagers from Catchamba Nalu began building a new front dike to recover mangrove rice production. One man in Catchamba said: ‘Caequene rehabilitated their rice paddies. We went there to see it and our hearts were filled with hope’.24 He added: ‘Before we were forced to go to Cafine [a rice refugia village] to ask for rice paddies to work, but now that is over because we have built dikes around our own paddies’.25

People from Catchamba Nalu had participated in the construction of the first dike in Caequene in 2013. Similarly, in 2015–16, villagers from Caequene went several times to Catchamba to help build their front dike and share their experience. They dammed five saltwater inlets together — one was 14.60 m wide. Later, in 2017, people in Catchamba reciprocated again when Caequene lengthened their front dike. The farmer from Cadique Yala, who had assisted Caequene, also went to Catchamba Nalu a few times. Frazão-Moreira (2009) describes similar inter-ethnic interfaces of cooperation in mangrove rice farming in the 1990s among Nalu and Balanta peoples.

In August 2018, during the rainy season and at the beginning of the agricultural cycle, the front dike in Catchamba ruptured due to the accumulation of rainwater runoff inside the rice paddies. A farmer from Caequene, and co-author of this article, who is today recognized as having advanced knowledge in mangrove rice water management, visited Catchamba's rice fields. An initial 8 m rupture had grown to more than 40 m in three days. People from Caequene helped villagers in Catchamba repair their dike during this crisis. Following this repair, a farmer in Catchamba also became recognized for his advanced knowledge of water management strategies: ‘Here, Nabi is now also a tekniku [a person with advanced knowledge], he gained experience from Ansumane [from Caequene]’.26 Once again, the rupture of a dike — posing a major threat to the viability of an entire mangrove rice basin — served as an opportunity for experimentation and knowledge transmission among farmers from different villages. All knowledge, even when specialized, is incomplete (Agrawal, 1995); it evolves and changes as it circulates (Raj, 2013). Moments in which dikes need to be newly built or repaired are opportunities for both sharing, consolidating and updating knowledge.

Case 2: Successful Knowledge Redistribution Despite the Failure to Repair

In 2016 we visited Farim, another village close to Caequene. People in Farim were in the process of building the front dike to restore the rice production they had had before the Struggle for Independence. They were in the second phase of building the dike, during which the mud must be compressed (tchaboka in Guinean Kriol). A farmer from Farim showed us where someone with knowledge of mangrove rice dike construction had passed by the place they were working and left a message inscribed in the mud. The passerby had apparently noticed they were not doing the tchaboka correctly and shaped a prototype in the mud a few metres away from the construction. The ephemeral message in the mud was effective and the farmers working on the dike in Farim changed their tchaboka practice. The possibilities of sharing techniques and knowledge are manifold and the mangrove, the mud, the tides and the moon (Sousa and Luz, 2018) are important subjects in that transmission.

Farim received advice from different sources: farmers in Caequene (who also share strong family ties with Farim), the expert from Cadique Yala who had assisted in Caequene and Catchamba, and a Balanta farmer whose family was from Djiu de Mel (an area exposed to the sea, see Figure 1). The father of the Balanta farmer was a guest in Farim during the Struggle for Independence, lived there for several years and was given land to work. When he went back to Djiu de Mel, he gave the land back, but he said that maybe his son would come back to Farim one day. His son began advising the people of Farim in 2015 on water infrastructures and sharing his views about the best location for the dike and the best time to build it.

For so many years they [the youth in Farim] had never seen their fathers going to the mangrove rice fields …. If you tell them: ‘Sharpen your machete’, they are ready to go because that [upland shifting cultivation] is what they are used to — they saw us doing it. We should not blame them, they got used to what their fathers were doing.27

Farim lacked the internal labour to try to rebuild the dike once more. Perhaps with direct access to funds, they could gather the labour needed to repair the dike and build it to the required size in the present conditions. Then, eventually, a new generation of young farmers would have the opportunity to reconnect to mangrove rice farming and a technological solution for Farim could be found.

The swampy micro-environments are dynamic and highly diverse, and therefore only particular nature technologies specific to each site make rice fields functional. Knowledge repositories are enriched and transformed by perspectives and experiences informed by specific places (Sarasin, 2020: 2–3). Cases like the village of Farim, which is facing technological and labour difficulties, are relevant to the socialized repository of experiences, which inevitably includes failures.

Cases 3 and 4: Land and Cash for Labour and Infrastructure

In the first two cases described above, circulation of labour is rooted in kinship and/or reciprocity, yet circulation of labour and advanced knowledge among villages may also rely on cash payment. Examples of this type of exchange were found in two households, one in Madina and another in Ponta di Pursoris, which rely on cashew sales or on non-agricultural sources of income (for example, from teaching) to purchase rice for everyday household use.

In 2016, we interviewed a Mandinga man in Madina who had hired Balanta people to build dikes and restore his abandoned rice paddies. He hired a person from Darsalam, a rice refugia village, for 120,000 West African francs or XOF (equivalent to US$ 207.30 on 14 April 2016)28 for approximately two months’ work. He also hired seven people from a nearby village for XOF 40,000 or US$ 69.10, but the work done did not meet his expectations. His brother in Komo Island (south of another peninsula of the Tombali region, see Figure 1) suggested they hire some people from Komo who were known to be efficient and experienced, and he hired them for XOF 65,000 or US$ 112.30. Upon completion, he was so pleased that he tipped them with an iron shovel head (worth about XOF 10,000 or US$ 16.57). To maintain some rudimentary fixing, he also made land available in his rice paddies for a Balanta farmer from another village on the agreement that he would perform some damming work. This way he was able to create the conditions to grow some rice himself, although limited and only in the upper areas of the bolanha. When we visited his rice fields, we spoke with the Balanta farmer who was using his rice fields and making small dike repairs. In the end, the efforts put into the construction of the main dike were not sufficient. For an individual who is not part of the networks that enable the circulation of knowledge and labour except by payment, the labour needed for this type of construction from scratch is overwhelming. In 2022, these rice fields continued to be cultivated rudimentarily.

In 2019, in Ponta di Pursoris, a landowner also hired Balanta people to build new dikes in his underused mangrove swamps. Some people from Caequene also worked there for a day without accepting payment since the two men who owned the rice paddies in that area had been teachers at their school. We interviewed one of the landowners and participated in a day of work in which the man, his family and Caequene's youth worked together in building the main dike. As of 2022 these reclaimed rice fields were active and producing rice for the people who invested in their restoration.

Caequene, Farim and Catchamba are all connected by familial ties and have mutually benefited from shared labour and knowledge in the construction of their dikes. Mutual aid and counselling established between these rice margins (Caequene, Catchamba, Farim) and rice refugia (Cadique Yala, Djiu de Mel) are grounded in long-term reciprocal arrangements regarding land access. As van der Ploeg (1991: 107) notes regarding mangrove rice farming in Guinea-Bissau, ‘the more these non-commodity circuits are present and actively reproduced, the more food security is guaranteed, on inter- as well as an intra-village level’.

In the cases of Madina and Ponta di Pursoris, cash payments were crucial to access labour and knowledge. In the future, these people will likely continue to depend on hired labour to repair the dike in case it breaks in any significant way. Such paid labour incentivizes longer-distance networks; for example, farmers travel from Komo (located on another peninsula and about 60 km away by motorcycle) to work in Madina. Concerns about increased commoditization of labour have been justifiably raised in Guinea-Bissau and beyond (Palliere et al., 2018). However, in cases in which there are no previously established relationships between villages, mangrove rice technology exchange would have to be mediated through cash payments for labour. Moreover, this does not imply that all forms of labour are consequently affected. Van der Ploeg (1991: 95) notes that: ‘Commodity and non-commodity circuits, commoditisation and decommoditisation should not be conceptualized as mutually exclusive in time and space’. Also, the possibility of having access to cash through mangrove rice labour potentially works as an incentive for young people to reconsider their relation to the mangrove rice world.

Farim and Madina did not succeed in the rehabilitation of their main dikes and rice cultivation is being carried out only in the upper areas of the mangrove swamp, which are less affected by spring tides. Yet, the attempts to build the main dikes and occupy the lower parts of the basin played an important, although invisible, role in redistributing knowledge, providing opportunities for reconnection to the swamp ecologies (particularly in Farim), researching and trialling, and promoting the circulation of funds (particularly in Madina) between rice refugia and rice margins.

FUNDING THE MARGINS TO STRENGTHEN THE WHOLE

Concerns raised by Davidson (2015) and Hawthorne (2017) about the effects of climate in the disintegration of mangrove rice societies will probably be revisited several times in the future. If disintegration is understood as the breakdown of a whole into smaller parts, then this might lead to a situation in which rice production is reduced to a few rice refugia. A disjointed rice landscape might pave the way for more generalized disintegration of rice-producing systems. This disintegration can potentially be pre-empted by a reinvigoration of the cohesive forces of knowledge circulation.

Adaptation as a Long-standing and Network-based Process

Policies directed at supporting rice production in Guinea-Bissau must recognize rice production as a network through which labour and knowledge are exchanged, rather than one that envisions rice being produced in isolated locations. When a village is not able to provide the advanced knowledge or labour itself, support from other villages is sought, resulting in people from different cultural profiles and ages uniting around a particular effort. As described by Östling et al. (2018), knowledge is continuously being formed by cultural processes, and these moments allow for the sharing of experiences regarding the most effective techno-natures in water management suitable for the ever-changing conditions in mangrove rice paddies.

In this connected network, advanced knowledge of hydraulics, construction of infrastructure, topography and spring tides (Sousa and Luz, 2018) is distributed in knowledge networks shared among villages along lines of reciprocity, family ties or contract work. When mangrove rice rehabilitation takes place in a village of discontinuous rice production (like Caequene, Catchamba, Farim or Madina), the participating communities absorb and recreate advanced knowledge taken from rice refugia (e.g. Cadique Yala, Komo or Djiu de Mel). Therefore, the accumulated knowledge of rice refugia is redistributed during attempts to re-establish mangrove rice production in rice margins. These periods of rice rehabilitation strengthen and extend pre-existing networks, as other villages at the margins of mangrove rice production are integrated or re-integrated into the rice knowledge web. Such small-scale processes create a regional network that is ecologically informed and continuously updated about the ever-changing micro-geographies of different mangrove swamps.

Failure as Part of Adaptation

In southern Guinea-Bissau, the places where knowledge about mangrove rice cultivation is being produced are going through deep transformations, and the effects of climate change are increasingly carved into the landscape. Haraway (2003) argues that knowledge is imprinted in the social, political and cultural conditions of the places where it is produced, and it is, therefore, fundamentally hybrid and situated. Taking this into consideration, if farmers are gradually exposed to the processes of ecological and climate transformation, and can repair, rethink, trial and change water management infrastructure, their learning and production of knowledge is more successful, which leads to informed decision making. This is only made possible by the practice of doing. In the face of potential apocalyptic climate futures, strengthening the margins of the rice production network can incorporate novelty, including the knowledge produced with experiences of failure. Development programmes, however, are often guided by more siloed, controlled and limited models of knowledge transfer, where success and failure are evaluated in rather narrow terms. Failure and success are understood in the short term, when the context of climate transformation requires a long-term approach to trialling and experimentation, allowing for mangrove rice to evolve according to the changes taking place in climate and ecologies. Mangrove rice farming is historically mired in uncertainty, crises and risk; localized failures in the context of a rapidly changing climate are not surprising. Moreover, failure to fully and permanently restore rice production does not signify a failure in terms of knowledge production and transmission. On the contrary, failure to build a complete or enduring dike means that knowledge was shared, technology was experimented with, and learning about what did not work took place. Participants in these efforts are better prepared for future experience of reconstruction. Development strategies must recognize collective value in local failures.

Redistributive Margins

Efforts to rehabilitate rice production in villages located at the margins of the rice-producing web are relevant to existing rice refugia for two main reasons: (1) by hiring people from rice refugia for rehabilitation efforts, villages at the rice margins recognize knowledge and skills at rice refugia and reciprocate with goods, services, payments, or by other means; and (2) attempts at recovering rice production at the margins often involve experienced farmers from rice refugia villages who gain valuable insights from that process taking place in a different micro-environment, involving site-specific techniques and technology to experiment with and learn from. These interactions will end up benefiting not only the villages that potentially re-establish their rice production but also villages that are able to support them with labour and knowledge and receive in exchange payments in cash, access to land and knowledge inputs from new experiences, among other forms of compensation.

The enhanced social, experiential and intellectual connectivity that comes along with the resurgence of mangrove rice farming promotes the capacity for reproducing rice in rapidly changing ecologies by boosting knowledge circulation at a regional scale, redistributing services, goods, cash and social ties.

Decentring Development

The history of development programmes shows that considerable time and funding were used in the mediation between the supposed ‘beneficiaries’ of development and professional specialists (Redclift, 2018). This costly chain of actors is largely legitimized by specific beliefs about who the experts are, what expert knowledge means and what languages and practices must be used to achieve a certain development goal. Farmers must be included among those recognized as bearing advanced knowledge in agricultural management and as capable of managing small-scale funding and/or access to site-specific resources (for example, tools, food for work, hiring labour). However, to initiate this developmental trajectory, appropriate strategies must be implemented.

The works of Paul Richard (1985, 1996) have been seminal in explaining and advocating for the recognition that adaptations are an everyday practice of peasant life, since they arise from an ever-changing understanding of local ecosystem and agri-environmental processes. The knowledge produced in adaptation is immersed into cultural processes, and these have enabled peoples to resist the adversities of colonial policies, economic liberalization and, most recently, climate change. More emphasis should be put on supporting that inventiveness (Richards, 1985). The importance of ‘locally embedded processes of learning and innovation’ has also been recently highlighted for the context of mangrove rice farming in Guinea-Bissau (Martiarena and Temudo, 2023: 1). Based on this literature, to achieve the goals of the funds advertised in COP27, in the specific case of Guinea-Bissau, support to the production of mangrove rice should be delivered in a decentralized manner. We add that, as mentioned above, if this is carried out through the rice margins, the connections established can irrigate (through cash, reciprocity and experimentation) the rhizomatic networks that make up the rice landscapes in coastal Guinea-Bissau today.

Unchangeable Development

Reimagining development approaches by directly funding farmers’ associations or groups of farmers would make a structural difference to the legacy built with foreign aid programmes. It would potentially enable the people most knowledgeable on rice production to respond to the effects of global warming in the mangroves in ways that fit their social context and the micro-ecologies on which they depend. Also, other forms of alliances can be sought, such as one between international solidarity, universities and peasants (see, for example, Sousa et al., 2021). Funding directed at specific villages for recovering rice mangroves with the participation of researchers could possibly contribute effectively, firstly, to food security by having small funding directed at specific conditions of particular villages, mangroves and rice fields, and secondly to knowledge production through research outputs that could potentially influence policy making about processes of mangrove rice recovery and decentralized funding.

CONCLUSION

Adaptation to environmental change and variation in mangrove rice farming in Guinea-Bissau learns from knowledge networks and regional collaboration. Climate-induced transformations threaten to fragment these networks, reducing rice production to isolated refugia. However, the exchange of labour, knowledge and technology across villages counters this disintegration. Rehabilitating rice margins reinforces networks and redistributive expertise and fosters the capacity to respond to climate change. Failure in these efforts is also valuable as it enables learning, experimentation and future preparedness. Development strategies must recognize these processes, emphasizing decentralized funding and local advanced knowledge. By strengthening the connectivity of mangrove rice landscapes through reciprocal relationships and experimental practices, the staple producing sector in Guinea-Bissau can better navigate the challenges of climate change. This approach also offers a model for redefining development as a bottom-up, adaptive and context-specific process of innovation and ongoing adaptation.

This discussion, grounded at the local level, benefits from thinking through the historical politics of colonialism, persisting forms of coloniality and climate change. On the one hand, there are grounds to frame the recovery of the infrastructure needed for mangrove rice production as historical reparations for Portuguese colonialism, particularly regarding the bombing of rice fields by the colonial army during the 11-year War of Independence. On the other hand, considering that rises in sea levels have been largely caused by the Global North, resulting in new and considerable damage to the economies and lives of coastal peoples in Guinea-Bissau and beyond, a cancellation of public debt, which has been evaluated by the IMF (2024) as 80.3 per cent of the country's GDP, is a means for achieving a sort of redistributive climate justice. These considerations suggest that there should be organization and representation of peasants around the defence of their rights in decisions that affect their modes of life, as well as having an urban population and decision makers who will listen to and accommodate rural perspectives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are deeply thankful to the people in Guinea-Bissau who shared their knowledge, perspectives and experience. The first author is grateful to Conceição Vaz, Nuno Meireles, Linda Carney and Matthew Carney for their childcare work. The authors also thank Liam Carney for proofreading. This publication was supported by two individual grants, No. CEECIND/04424/2017 (first author) and No. CEECIND/03433/2021 (third author), and by the research project MARGINS, ‘People, Rice and Mangroves at the Margins: A Hybrid and Contested Interface in a Changing World’ (Grant No. PTDC/SOC-ANT/0741/2021), all funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT). The authors are also grateful to the four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article and to Boaventura Monjane and Paula Duarte Lopes who commented on a draft of this article.

Biographies

Joana Sousa (corresponding author; [email protected]) is a researcher at the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. She works on mangrove rice farming in the context of climate change, colonial and post-colonial agricultural policies and social change, more recently in the context of an interdisciplinary research project (MARGINS).

Ansomane Braima Dabó ([email protected]) is a farmer in Cabasane Biteraune, Caequene, Guinea-Bissau. In his village he is recognized for his advanced knowledge of mangrove rice water management. He studied in Cadique Nbitna, Catió and Iemberém. From 2009 to 2012 he was head of the youth association in the village of Caequene.

Ana Luísa Luz ([email protected]) is a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences, Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal. She is interested in the interface between nature conservation policies and local development in rural areas, and the management of the commons as a means to achieve local welfare and fire prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1 In West Africa, mangrove or tidal rice is also cultivated in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Rice farming histories are socially and technologically diverse. For example, Hawthorne (2001) describes how the Balanta people emerged as mangrove rice farmers in the mid-17th century having found protection in the lowlands in the context of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, while in Sierra Leone mangrove rice production depended on enslaved labour between 1882 and 1928 (Mouser et al., 2015).

- 2 Jobel, or Djobel, is a village surrounded by sea canals. The precarity of life in Jobel was also described 15 years ago by the International Committee for the Red Cross (see https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/114609), and yet it has received insufficient attention to date. Other villages in the Cacheu region such as Bulol, Djifunco, Edjim, Elalab Arame, Elia and Eossor are similarly surrounded by canals. See Fandé (2020: 91–92).

- 3 Garbanzo et al. (2024) state that there was a decrease in rainfall from 1961 to 1985 and an overall increase of 350 mm in the last four decades.

- 4 See also Bird (2016) for an account of the impact of mangrove forest conservation on local livelihoods in Senegal and Beymer-Farris and Bassett (2012) for a similar case in Tanzania.

- 5 This is contested by Temudo (1998: 87) who says that the fugon ‘can only be considered units in residential, social and symbolic terms, but not economic’.

- 6 The circulation of rice technology was given an Atlantic dimension in Carney (2002) who drew connections between West Africa, the USA and Brazil. Carmo et al. (2020) present a hypothesis on the role of West African knowledge in the early presence of rice in Portugal's estuarine areas in the 16th and 17th centuries. Van Andel et al. (2016) studied the connections of rice germplasm held by Maroon communities in Suriname with West Africa. Similar connections were more recently studied with reference to the USA, Brazil and Southeast Asia (van de Loosdrecht et al., 2024). There is a great number and diversity of designations given to rice varieties. Among Maroon communities, names can be kept for 300 years (Pinas et al., 2023), but in the Gambia, names are mainly changed after 20 years (Nuijten and Almekinders, 2008). Names alone are not a guide to defining specific rice varieties, but tracing the movement of names among different communities can help develop hypotheses about the connections established between rice-producing peoples. For example, Carney (2002) mentions a rice variety grown in South Carolina (USA) that was introduced in Sierra Leone by formerly enslaved people in the 19th century. She describes a possible linguistic connection between the term ‘America’ and variety/varieties known vernacularly as méréki or mériké described for the Niger River floodplain in 1899, in Sierra Leone in 1917, and in Guinea and Ivory Coast in 1996 (ibid.: 176). There is also a variety called ‘Americano’ described in Guinea-Bissau between 1948 and 1973 (Garbanzo et al., 2024) and a variety called merke in current use in southern Guinea-Bissau (authors’ observation in fieldwork).

- 7 Van der Ploeg (1991) describes this migration as a result of the Balanta people fleeing disadvantageous commodity relations based on groundnut cultivation in the north.

- 8 Although poorly studied, this influence may correspond to an expansion to the north of what Fields-Black (2008) describes as a meshwork of rice technologies applied to the different micro-environments in the lands of the Nalu, Baga and Nbulushi in northern Guinea.

- 9 Works by van Andel et al. (2023), Carney (2004) and Pinas et al. (2023) have largely included women's perspective of rice technology.

- 10 Mainly known as Nino Vieira, he became an important leader in the PAIGC guerrilla militia. He was prime minister from 1978 to 1980, the head of the 1980 coup and president in 1980–99 (until the civil war) and in 2005–09 (until his assassination). The association between Nino and Marga is also detailed in Mendy (2019: 129).

- 11 Aristides Pereira was an important figure in the PAIGC guerrilla militia in Guinea-Bissau and served as President of Cape Verde from 1975 to 1991.

- 12 Bolanha refers to an area seasonally or periodically flooded by rainwater or salt water that can be used to grow rice provided adequate infrastructure is built to manage salinity and water levels, among other more specific conditions.

- 13 Interview, village elder, Caequene, February 2013.

- 14 But officially recognized in 1974.

- 15 For FAOSTAT's ‘Food and Agriculture Data’, see www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home

- 16 Interviews, farmers, Cafine, January 2017.

- 17 Interview, farmer, Cafine, January 2017.

- 18 A more detailed description of this process can be found in the documentary ‘Maboan: Notes on the Construction of a Dam’ (Luz et al., 2015) and in Sousa et al. (2021).

- 19 Interviews, young farmers, Caequene, January 2017.

- 20 Interview, village elder, Caequene, January 2017.

- 21 Other studies have also described the role of marriage in the different types of reciprocal arrangements (Lundy, 2012; Temudo, 1998).

- 22 Among the Nalu people in Cubucaré there is some preference for marrying between crossed cousins, a custom that is decreasing but was and is still observed (Frazão-Moreira, 2009).

- 23 It was reaffirmed by both Frazão-Moreira (2009) and Temudo (1998) that each person is attached to a multidimensional framework of identities that link each and every person to many other people in different ways.

- 24 Interview, rice farmer, Catchamba, June 2019.

- 25 Ibid.

- 26 Interview, rice farmer, Catchamba, June 2019.

- 27 Interview, elder, Farim, June 2019.

- 28 The average daily wage is XOF 1,500 per day (about US$ 2.47 at the time of writing) for agricultural work, but the building of dikes is often paid as a contract and not by number of days worked. See www.oanda.com/currency-converter/en/?from=XOF&to=USD&amount=120000