Higher spring temperatures increase food scarcity and limit the current and future distributions of crossbills

Abstract

Aim

Understanding how climate affects species distributions remains a major challenge, with the relative importance of direct physiological effects versus biotic interactions still poorly understood. We focus on three species of resource specialists (crossbill Loxia finches) to assess the role of climate in determining the seasonal availability of their food, the importance of climate and the occurrence of their food plants for explaining their current distributions, and to predict changes in their distributions under future climate change scenarios.

Location

Europe.

Methods

We used datasets on the timing of seed fall in European Scots pine Pinus sylvestris forests (where different crossbill species occur) to estimate seed fall phenology and climate data to determine its influence on spatial and temporal variation in the timing of seed fall to provide a link between climate and seed scarcity for crossbills. We used large-scale datasets on crossbill distribution, cover of the conifers relied on by the three crossbill species and climate variables associated with timing of seed fall, to assess their relative importance for predicting crossbill distributions. We used species distribution modelling to predict changes in their distributions under climate change projections for 2070.

Results

We found that seed fall occurred 1.5–2 months earlier in southern Europe than in Sweden and Scotland and was associated with variation in spring maximum temperatures and precipitation. These climate variables and area covered with conifers relied on by the crossbills explained much of their observed distributions. Projections under global change scenarios revealed reductions in potential crossbill distributions, especially for parrot crossbills.

Main conclusions

Ranges of resource specialists are directly influenced by the presence of their food plants, with climate conditions further affecting resource availability and the window of food scarcity indirectly. Future distributions will be determined by tree responses to changing climatic conditions and the impact of climate on seed fall phenology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Understanding the factors influencing species' distributions is a core challenge of ecology and biogeography (Gaston & Blackburn, 2000; Sexton, McIntyre, Angert, & Rice, 2009). Climate has been recognized as one of the main determinants of species' ranges (Huntley, Berry, Cramer, & McDonald, 1995; Pearson & Dawson, 2003; Pither, 2003), with species' ranges contracting and expanding in response to past and recent climate change (Davis & Shaw, 2001; Parmesan, 2006; Svenning, Normand, & Kageyama, 2008; Walther et al., 2002). However, other factors than climate influence species' distributions (Guisan & Thuiller, 2005; Pacifici et al., 2015; Wisz et al., 2013). For example, historical contingencies and dispersal abilities can shape distributions and the extent to which potential ranges are occupied, with important implications for predicting future distributions (Svenning & Skov, 2004, 2007). Biotic interactions also affect species' distributions (Sexton et al., 2009). However, biotic interactions are dynamic in space and time, interact in complex ways with climate (Gilman, Urban, Tewksbury, Gilchrist, & Holt, 2010; Tylianakis, Didham, Bascompte, & Wardle, 2008) and thus pose challenges for predicting species responses to global change (Kissling et al., 2012; Wisz et al., 2013). Resource specialists present a unique opportunity to understand the factors affecting distributions, given that they have a simpler and more tractable feeding ecology than other systems (Araújo & Luoto, 2007; Huntley, 1995; Kissling, Rahbek, & Böhning-Gaese, 2007; Koenig & Haydock, 1999; Li et al., 2015; Wisz et al., 2013). This is especially true when resource specialists have well-characterized natural histories, such that linking population dynamics and, for example, resource phenology is possible.

Here, we assess the role of climate in determining the seasonal availability of food for European crossbills (Loxia spp.), and the importance of climate and the occurrence of their food plants for explaining crossbill distributions. Crossbills are medium-sized finches specialized for feeding on seeds in conifer cones (Benkman, 1993, 2003; Newton, 1972), with crossed mandibles essential for accessing seeds (Benkman & Lindholm, 1991). Experimental studies reveal that the different species and ecotypes of crossbills in North America each specialize on conifers that hold seeds in their cones reliably, especially from late winter to summer when the next seed crop develops (Benkman, 1987, 1993, 2003).

Three closely related crossbill species occur regularly in Europe: common crossbill (L. curvirostra), parrot crossbill (L. pytyopsittacus) and Scottish crossbill (L. scotica; Newton, 1972; Cramp & Perrins, 1994). Common crossbills are widely distributed, occupying Russia, Fennoscandia, the British Isles and parts of central and Mediterranean Europe, feeding mostly on Norway spruce (Picea abies) in the north and multiple species of pine including Scots pine Pinus sylvestris, P. halepensis, P. mugo, P. nigra and P. uncinata in the south (Benkman & Mezquida, 2015; Cramp & Perrins, 1994; Newton, 1972). Parrot crossbills occur mainly from Russia west of the Urals to Scandinavia (Cramp & Perrins, 1994) and have an especially deep bill for foraging on the hard cones of Scots pine (Newton, 1972; Summers, Dawson, & Proctor, 2010). Scottish crossbills are a narrow-range endemic species restricted to Scotland where it is believed to have evolved since the last glaciation (Knox, 1990; Nethersole-Thompson, 1975). Even though their bill is intermediate in size between parrot and common crossbills, Scottish crossbills also are thought to be adapted for foraging on the cones of Scots pine (Knox, 1990; Nethersole-Thompson, 1975), the only conifer available to crossbills in Scotland until the last 100–200 years when multiple non-native conifer species were planted extensively (Marquiss & Rae, 2002; Summers et al., 2010).

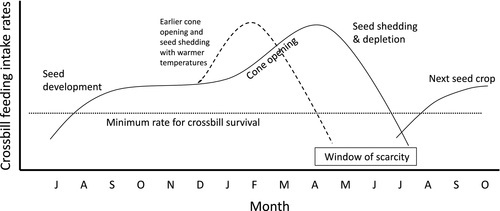

Although crossbills forage on Scots pine throughout Europe, crossbills specialized for foraging on Scots pine (i.e., parrot and Scottish crossbills) are confined to mostly northern Europe and Scotland, representing less than one-sixth of the geographic range of Scots pine (Knox, 1990; Newton, 1972). Seeds in developing Scots pine cones become profitable to crossbills by August (Figure 1; Marquiss & Rae, 2002). The cones mature in autumn, and large-billed crossbills in particular continue foraging on seeds in the closed cones through winter (Marquiss & Rae, 2002). By April, cones begin to open and shed seeds (Summers et al., 2010). Although seeds in open cones are more accessible than in closed cones, the availability of seeds to crossbills declines as seeds are shed (Figure 1; Benkman, 1987; Summers et al., 2010), with crossbills rarely foraging on seeds that have fallen to the ground (Marquiss & Rae, 2002). The window of time between when most of the seeds have been shed and the next cone crop becomes profitable to crossbills is potentially the period of greatest food limitation (Figure 1; Benkman, 1993; Summers et al., 2010). Because cone scales spread apart, releasing the seeds from their base, in response to dry conditions and high temperatures (Dawson, Vincent, & Rocca, 1997), a hypothesis for the northern distribution of “Scots pine” crossbills is that they are restricted to cooler climates because such conditions result in seeds being more reliably held in cones until a new cone crop becomes available in late summer (Figure 1).

Warmer conditions in the south are likely to cause Scots pine cones to open earlier (see Castro, Gómez, García, Zamora, & Hódar, 1999 for southern Spain where seed shedding begins in February) and shed their seeds more rapidly resulting in long periods of seed scarcity. Consistent with this hypothesis, the relatively small-billed common crossbills feeding on Scots pine in the Mediterranean regularly disperse during late spring (after pine seed dispersal) and summer to search for alternative seed sources until a new crop develops (Arizaga, Alonso, & Edelaar, 2015; E. T. Mezquida, pers. obs.). Similarly, rapid release of Scots pine seeds following a warm spell in April caused an exodus of common crossbills nesting in the Netherlands (Bijlsma, De Roder, & van Beusekom, 1988). If the window of seed scarcity in Scots pine increased in northern Europe in response to climate change, the massive-billed parrot crossbill might shift to feeding on seeds in Norway spruce, the one other co-occurring conifer in much of the parrot crossbill's range. However, Norway spruce, which already tends to shed its seeds in the spring earlier than does Scots pine (Newton, 1972), would probably also shed its seeds more rapidly. Moreover, the smaller billed common crossbill, which in northern Europe is adapted for foraging on Norway spruce (Newton, 1972), would likely outcompete the parrot crossbill for spruce seeds. Although crossbills may use alternative food resources when conifer seeds are scarce (Cramp & Perrins, 1994), crossbills are inefficient compared to other seed-eating birds at handling non-conifer seeds, and it is doubtful crossbills can persist for long by foraging on these alternative foods (Benkman, 1988).

We used datasets on the timing of seed fall in the Iberian Peninsula (only common crossbills occur), Scotland (where the Scottish crossbill was the only resident crossbill species until recently) and Sweden (parrot and common crossbills occur) to estimate the phenology of seed fall in Scots pine. We predicted that seed fall would occur earlier at lower latitudes (i.e., Iberian Peninsula). Second, we address the hypothesis that climate influences spatial and temporal variation in the timing of seed fall to provide a link between climate and seed scarcity for crossbills. Third, we assess the relative importance of climate variables associated with timing of seed fall and the cover of the main conifers relied on by each crossbill species, for predicting their distributions. If the climate variables related to delayed seed fall account for crossbill distributions, then this would support the hypothesis that longer seed retention is critical for crossbills to specialize on Scots pine, as well as other conifers (Benkman, 1993).

Finally, we use species distribution modelling to predict changes in the potential distributions of crossbills under future climate change scenarios. If future climate change hastens seed fall, it will likely negatively impact crossbills (Benkman, 2016). Indeed, an 80% decline in population size over 8 years in a resident crossbill (Cassia crossbill L. sinesciurus) in North America coincided with a reduction in annual survival in apparent response to premature releases of seeds following an increase in hot (≥32°C) summer days (Benkman, 2016; Santisteban, Benkman, Fetz, & Smith, 2012). Thus, climate-related factors that influence the availability of food resources may negatively impact the persistence of crossbill populations.

2 METHODS

2.1 Geographical and temporal variation in seed fall

We measured Scots pine seed fall at a total of four sites in two different regions in the Iberian System mountain range, Spain. One region was in Teruel Province at the south-eastern limit of the Iberian System, with sites in Valdelinares and Fortanete (40°23′N, 0°36′W). The other was in Soria Province at the north-western limit of the Iberian System, with sites in Duruelo de la Sierra and near Santa Inés mountain pass (42°00′N, 2°50′W). At each site, we systematically selected 15 trees every 30–60 m along 1 km transects and placed one trap to collect falling seeds under each tree. Seed traps consisted of aluminium trays placed on the ground with a catch area of 0.15 m2 and covered with 1.3-cm wire mesh to prevent seed removal by birds and mammals. Each year, traps were set up during February, and seeds were collected every 17–20 days until early July. Seed fall was recorded over 3 years (2010–2012).

We used seed fall data from Scots pine at Abernethy Forest, Scotland. Timing of seed fall in this forest has been previously described using part of this dataset (Summers, 2011; Summers & Proctor, 2005). Methods followed are those described in that study. In short, four sites were selected at Abernethy Forest (57°15′N, 3°40′W), three in stands of ancient native pinewood (Ice Wood, Memorial Wood, and Bognacruie) and one area of plantation woodland, grown from seeds of local provenance (Tore Hill). Five seed traps were located equidistantly under trees along 1–2 km transects set through each site. Seed traps were plastic pots with a catch area of 0.13 m2. Traps were set up in February, and seeds were collected at the end of each month until September. Seed fall was recorded for 16 seed years (1992–2007).

We used published information for two sites in central Sweden (Hannerz, Almqvist, & Hornfeldt, 2002) to characterize the timing of Scots pine seed fall in Scandinavia. Hannerz et al. (2002) recorded seed fall for 4 years (1993–1996) at Garpenberg (60°16′N, 16°11′E), using three plastic trays with a catch area of 0.14 m2 placed on the ground, 50-m apart. Traps were set up in early March, and seeds were collected on eight occasions until late July or early August. Seed fall was recorded for 3 years (1996, 1997, and 1999) at Knivsta (59°43′N, 17°49′E). At this site, seed traps consisted of circular bag nets with a catch area of 0.25 m2 placed about 1 m above the ground. Ten traps were set up in late March, with an average distance of 10 m between traps, and seeds were collected on 10–14 occasions until July.

To estimate the timing of seed dispersal, we followed similar calculations to those made by Hannerz et al. (2002). We counted the number of Scots pine seeds per seed trap at each collection date and calculated the number of seeds per square metre. Dates were transformed into Julian days (1 = 1 January), taking into account leap years, in which we added 1 day after February 28. We included seed fall data from March to late July. February was excluded from calculations because seed fall data were not gathered for February in some years in Scotland, and when measured in February, no seeds were trapped in nearly all of the years. We calculated the cumulative proportion of the total seed fall for every collection date at each site and used these values to fit a logistic function for each year and site. Models were fitted using nonlinear least squares estimation in statistica (Statsoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Regression coefficients were used to estimate the days when 10%, 50% and 90% of the seed fall occurred (D10, D50, D90, hereafter) (see Appendix S1).

For each year and site, we determined the monthly mean, maximum and minimum temperatures, and monthly precipitation using the European daily high-resolution gridded climate dataset (0.25° grid resolution; Haylock et al., 2008) to relate to the timing of seed fall. To determine the relationship between climate variables and annual variation in timing of seed fall, we used monthly climate variables and the estimated D50 for each year and site in Scotland (i.e., the longest time series dataset). Preliminary correlations indicated that D50 was consistently correlated with climate variables for March and April, and mainly with maximum temperature. We fitted a multiple linear regression model between D50, as the response variable, and March and April maximum temperatures, and March precipitation as the predictor variables. March and April mean and minimum temperatures were not included due to their high correlation with maximum temperatures (r > .75, for all correlations), and April precipitation was excluded because of its high correlation with April maximum temperature (r = −.68). Finally, to evaluate whether the same climate variables were related to annual variation in seed fall for the three European regions, we fitted a linear mixed model between D50 and March and April maximum temperatures, and March precipitation, including region as a random effect (we compared a random intercept model to a random intercept and slope model).

2.2 Modelling observed crossbill distributions

To examine whether observed crossbill distributions are related to climate variables that influence the timing of Scots pine seed fall and cover of different conifer taxa, we modelled the presence of each crossbill species in relation to March and April maximum temperatures as well as cover of Scots pine, spruce (Picea spp.) and pines (Pinus spp.) other than Scots pine (hereafter referred to as “other pines”). Information on the current distribution of the three crossbill species came from the Atlas of European Breeding Birds (Hagemeijer & Blair, 1997). Data in this Atlas record the presence and absence of species breeding in Europe within cells of 50 × 50 km (Appendix S1).

We used maps of Scots pine, spruce and other pines developed by Brus et al. (2012) for European countries excluding Russia and Iceland that provide percent cover for each tree species (0%–100%) at 1 × 1 km resolution (Brus et al., 2012;). “Other pines” mostly included species regularly foraged on by crossbills (P. halepensis, P. mugo, P. nigra and P. uncinata), but also some species not used by crossbills (e.g., P. cembra, P. pinea; Cramp & Perrins, 1994). Information to map species distributions also included plantations. Thus, groups of species (spruce and other pines) included, for example, non-native plantations in the British Isles comprised mainly of Sitka spruce Picea sitchensis and lodgepole pine Pinus contorta (Brus et al., 2012), which are commonly utilized by crossbills (Summers & Broome, 2012).

We used monthly mean climate data (~1950–2000) from the WorldClim dataset (Hijmans, Cameron, Parra, Jones, & Jarvis, 2005) at 5′ resolution. We extracted data for monthly maximum, mean and minimum temperatures, and precipitation. For each 50 × 50 km grid with crossbill presence/absence data, we calculated mean values for maximum temperatures and percent cover of the different conifer taxa. We modelled the distributions using boosted regression trees (BRTs), a robust algorithm used in species distribution modelling (Elith, Leathwick, & Hastie, 2008). We used a binomial error structure and followed recommendations by Elith et al. (2008) for parameter settings (Appendix S1).

We divided the dataset of each crossbill species by selecting 70% of the data for model calibration and using the remaining 30% of the data to evaluate the predictive performance of the models. To account for spatial autocorrelation in the data, we split the data by spatial blocking (Roberts et al., 2017), using the “checkerboard1” method in the ENMeval package (Muscarella et al., 2014) in R 3.1.2 (R Core Development Team). We provide the percentage of variance explained and the area under the ROC curve (AUC), estimated on the evaluation datasets (Elith et al., 2008), as measures of accuracy for the selected models.

We used the best-fitted BRT model for each crossbill species to estimate their current potential distribution in Europe (excluding Iceland and Russia; as predicted by the models). To compare the observed distribution of each crossbill species with its potential distribution, we also calculated the area where each species is present according to the European Atlas (i.e., the area of the grids with presence of each species in the Atlas excluding Iceland and Russia). To make both maps more comparable, we overlaid a map of Europe on the Atlas grids to exclude areas lying outside of land (e.g., sea) and rasterized grids to 5′ resolution for area calculation. This calculation provides a rough estimate of the similarity between the distribution of crossbill species and their potential suitable habitat under current climate conditions.

2.3 Modelling future shifts in crossbill distributions

To forecast shifts in future crossbill distributions, we first modelled current potential crossbill distributions across Europe as a baseline for comparison. We used the BRT model for each crossbill species using March and April maximum temperatures and conifer cover, as above, to predict their current potential distribution across Europe (including Iceland and Russia). However, we modelled the potential cover of each conifer group (which may not currently be present due to historical factors or human influence) instead of using forest cover maps so that we could also forecast future distributions. We built models with cover of each conifer group as a separate response variable and three environmental variables as predictors: growing degree-days (GDD), absolute minimum temperature (AMT) and water balance, using monthly mean climate data (~1950–2000) from the WorldClim dataset (Hijmans et al., 2005) at 5′ resolution (Appendix S1). Because cover values were integers including many zeros, we modelled conifer cover using BRTs with a Poisson error structure and similar procedures as explained above (Appendix S1).

Predictions from the BRT models for each crossbill species provided the probability of presence for each grid cell. To select the threshold for converting the continuous logistic probability scale to a binary prediction of potential presence or absence, we calculated model-specific thresholds that maximized the sum of sensitivity and specificity (Jiménez-Valverde & Lobo, 2007). The restricted distribution of the Scottish crossbill resulted in few presences in the Atlas dataset, and this threshold method usually overpredicts the distribution of species with low prevalence. Thus, we estimated the optimal threshold value for this species using the SDMTools package (http://www.rforge.net/SDMTools/) in R. These thresholds were used for each model of current potential crossbill distribution, and in all models using future climate projections.

To forecast the future distributions of each crossbill species, we used the BRT models built for each species using climate change projections for 2070 (IPCC Fifth Assessment Report data) at 5′ resolution, also available from the WorldClim database. We used the IPCC-CMIP5 climate projections from three Global Circulation Models (GCMs) under two representative concentration pathways (RCP 4.5 and 8.5) (Appendix S1). We extracted monthly temperature and precipitation values for the six scenarios and computed the same three climate variables (i.e., GDD, AMT and water balance) as for current conditions. First, the distribution for each conifer species was forecasted by calculating the set of three predictor variables (i.e., GGD, AMT and water balance) under future conditions and predicting with the BRT models fitted for each conifer species. Projections for each conifer species together with March and April maximum temperatures for each scenario were used to forecast potential crossbill distributions (i.e., potential suitable habitat for each species under future conditions), as done for current conditions. We then calculated the predicted area of distribution for each crossbill species under each projection. In addition, we estimated the area for which projections from the three GCMs for each RCP overlapped (i.e., ensemble of predictions), the area where any of two predictions overlapped, and the sum of the areas predicted by at least one projection. All models were built, evaluated and projected using the dismo, raster and gbm packages in R (Hijmans, 2014; Hijmans, Phillips, Leathwick, & Elith, 2013; Ridgeway, 2013).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Geographical and temporal variation in seed fall

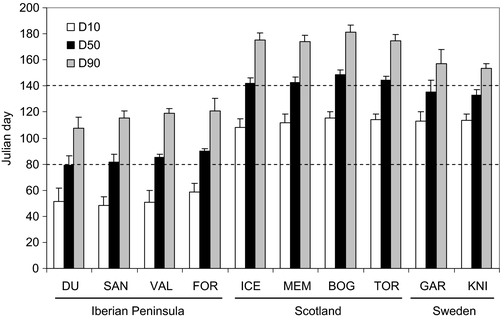

The estimated time when 10%, 50% and 90% of the seeds were shed (i.e., D10, D50 and D90) was 1.5–2 months earlier in the Iberian Peninsula than in Scotland or central Sweden (Figure 2; Appendix S2). The average date for D50 across all sites and years in each region was 25 March in the Iberian Peninsula, 23 May in Scotland and 14 May in central Sweden (Figure 2; Appendix S2).

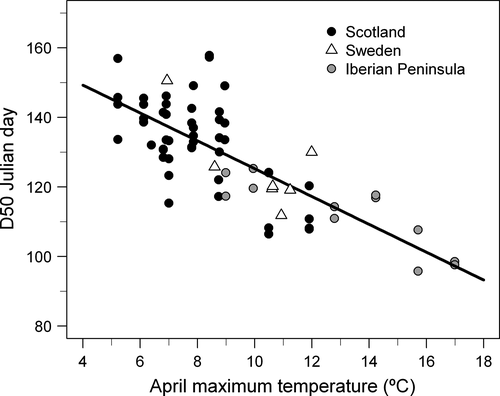

The linear multiple regression indicated that inter-annual variation in D50 in Scotland was negatively correlated with April maximum temperature (coefficient ± SE: −5.29 ± 0.99, p < .001), whereas March maximum temperature and precipitation did not have a detectable effect (−1.62 ± 1.05, p = .13; 0.07 ± 0.04, p = .11, respectively). The model explained 62% of the variation (F3,44 = 23.9, p < .001). The mixed model for all three regions including random variation around the intercept provided a better fit than a mixed intercept and slope model according to Akaike's Information Criterion (510.8 vs. 517.9), indicating that slopes did not differ among regions. The mixed intercept model showed that D50 was negatively associated with April maximum temperature (−4.00 ± 0.59, p < .001; Figure 3) and March maximum temperature (−3.18 ± 0.74, p < .001) and positively associated with March precipitation (0.08 ± 0.03, p = .018). Warmer spring temperatures accelerate seed fall and thereby increase the window of food scarcity for crossbills before the next seed crop develops (Figure 1).

3.2 Observed crossbill distributions

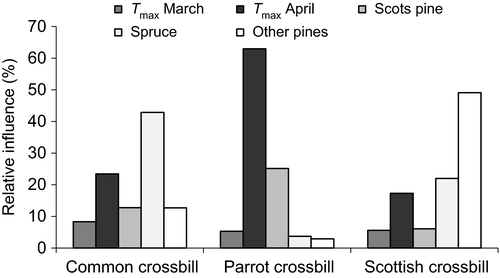

The BRT model for parrot crossbills performed well (% deviance explained: 83.2; AUC: 0.99), the one for common crossbills was less accurate, but still good (% deviance explained: 36.8; AUC: 0.88), with the model fit for Scottish crossbills intermediate (% deviance explained: 69.8; AUC: 0.99). The BRT model for common crossbills indicated that spruce cover (relative influence: 42.9%) and April maximum temperature (23.4%) contributed most to explain its observed distribution (Figure 4). April maximum temperature (63.0%) was the most important variable explaining parrot crossbill occurrence, followed by Scots pine cover (25.1%; Figure 4). The BRT model for Scottish crossbill distribution showed greater relative contributions for cover of other pines (49.1%), followed by spruce cover (22.0%) and April maximum temperature (17.3%; Figure 4). All crossbill species were more likely to occur where April maximum temperatures were lower (Table 1) and thus where seeds were more likely to be retained in the cones in late spring and early summer (Figure 3). Each crossbill species was also more likely to occur where the conifer on which it specializes was more abundant (Norway spruce for common crossbills, Scots pine for parrot crossbills; Table 1; Figure 4), or in the case of the Scottish crossbill where there were more introduced conifers (spruce and other pines; Table 1; Figure 4) that it now currently relies upon (Summers & Broome, 2012).

| Variables | Common crossbill | Parrot crossbill | Scottish crossbill | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | |

| March maximum temperature (°C) | 5.03 (0.14) | 9.06 (0.14) | 0.14 (0.13) | 8.56 (0.10) | 6.67 (0.24) | 7.16 (0.11) |

| April maximum temperature (°C) | 9.77 (0.12) | 14.10 (0.11) | 5.36 (0.12) | 13.39 (0.08) | 8.91 (0.28) | 12.08 (0.09) |

| Scots pine cover (%) | 14.11 (0.47) | 4.22 (0.20) | 29.91 (0.84) | 4.69 (0.16) | 6.77 (1.34) | 8.88 (0.27) |

| Spruce cover (%) | 11.35 (0.36) | 1.38 (0.09) | 19.12 (0.62) | 3.48 (0.16) | 8.90 (0.87) | 6.05 (0.20) |

| Pine cover (%) | 1.77 (0.16) | 2.25 (0.16) | 0.35 (0.06) | 2.36 (0.13) | 4.95 (0.94) | 2.01 (0.11) |

| Number of grids | 1,263 | 1,424 | 445 | 2,242 | 14 | 2,673 |

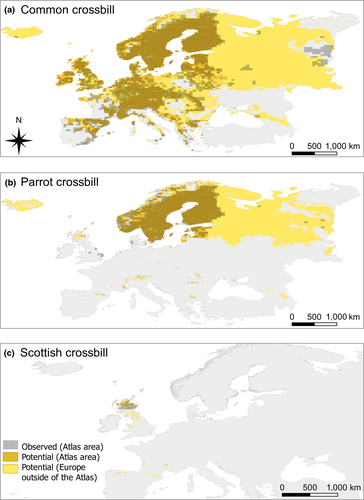

3.3 Potential crossbill distributions

The predicted potential distributions for common and parrot crossbills were similar (8%–9% difference) to the observed distributions within the area included in the European Atlas (Table 2; Figure 5). However, the predicted distribution for the Scottish crossbill was around half of the area calculated for the Atlas grids (Table 2; Figure 5), which it is expected due to the over-estimation of the area calculated at the grid resolution of the Atlas (see a detailed survey in Summers & Buckland, 2011). Extrapolating to all of Europe, the potential distribution of common crossbills increased 2.5-fold (Table 2), occupying Iceland and most of Russia (Figure 5); the distribution of parrot crossbills increased by 2.6-fold (Table 2), potentially occurring in parts of Iceland and the northern part of Russia (Figure 5); and the potential distribution of Scottish crossbills increased 2.8-fold (Table 2), potentially occupying Great Britain south of Scotland and scattered areas mainly in mountain ranges in the north of the Iberian Peninsula (Figure 5).

| Common crossbill | Parrot crossbill | Scottish crossbill | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current distributions | |||

| Observed (based on Atlas of European Breeding Birds) | 3,054,348 | 1,006,933 | 30,978 |

| Potential (predicted suitable habitat within the area covered by Atlas) | 2,770,140 | 1,088,389 | 14,592 |

| Potential (predicted suitable area for all of Europe) | 7,021,007 | 2,810,483 | 40,308 |

| Future distributions in 2070 (RCP 4.5) | |||

| CNRM-CM5 | 6,072,324 (14) | 1,460,725 (48) | 42,872 (+6) |

| HadGEM2-ES | 5,325,557 (24) | 1,096,851 (61) | 29,161 (28) |

| MPI-ESM-LR | 6,924,121 (1) | 1,791,610 (36) | 34,719 (14) |

| Average RCP 4.5 scenarios | 6,107,334 (13) | 1,449,729 (48) | 35,584 (12) |

| Predicted by the 3 scenarios | 4,922,889 (30) | 804,657 (71) | 4,040 (90) |

| Predicted by 2 scenarios | 1,194,859 | 599,078 | 18,380 |

| Predicted by 1 scenario | 1,163,618 | 737,058 | 57,872 |

| Future distribution in 2070 (RCP 8.5) | |||

| CNRM-CM5 | 5,457,918 (22) | 994,496 (65) | 36,754 (9) |

| HadGEM2-ES | 4,197,989 (40) | 584,946 (79) | 28,041 (30) |

| MPI-ESM-LR | 5,786,787 (18) | 1,254,073 (55) | 26,111 (35) |

| Average RCP 8.5 scenarios | 5,147,565 (27) | 944,505 (66) | 30,302 (25) |

| Predicted by the 3 scenarios | 4,013,086 (43) | 474,957 (83) | 1,721 (96) |

| Predicted by 2 scenarios | 1,196,412 | 474,523 | 14,431 |

| Predicted by 1 scenario | 1,010,610 | 459,599 | 56,881 |

3.4 Future crossbill distributions

Projections for the potential crossbill distributions under future (2070) climate change scenarios indicate a reduction in area for all three species, particularly for parrot crossbills (Table 2; Figure 6). The distribution of common crossbills was projected to expand in northern Russia, but decline overall by an average of 20% (Table 2) because of decreases in southern and central Europe (Figure 6). The future distribution for parrot crossbills contracted and shifted northwards in northern Fennoscandia and Russia (Figure 6) and declined overall by an average of 57% (Table 2). The future distribution for Scottish crossbill decreased on average by 18%, although one scenario predicted an increase of 6% (Table 2). Future projections predicted suitable areas remaining in Scotland, but also more distant areas in Iceland, along the Scandinavian coast and south-central Europe (mainly the Alps and the Pyrenees; Figure 6), areas the relatively sedentary Scottish crossbill is unlikely to colonize.

4 DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that timing of seed fall for Scots pine in southern Europe was 1.5–2 months earlier than in Scotland and Scandinavia, where the two “Scots pine” crossbills (Scottish and parrot) occur. Higher maximum temperatures during early spring (March–April) coincided with earlier seed fall, and maximum temperatures as well as precipitation during this period were associated with latitudinal differences in seed fall phenology. Consequently, the interval of food scarcity—the interval between when seeds are available between successive seed crops—for crossbills needing to rely on Scots pine seeds (Figure 1) increases dramatically from northern to southern Europe and likely accounts for the absence of a “Scots pine” crossbill in southern Europe. Further, climate variables related to the retention of seeds in the cones and to cover of conifers that comprise the main food plants for each crossbill species accounted for a substantial amount of the variation in their observed distributions, suggesting general indirect influences of climate on the distribution of crossbills. Climate change scenarios for the end of the century predict a reduction in the potential distribution of each crossbill species, which will be especially great for parrot crossbills whose observed distribution was the most strongly associated with cooler April temperatures. Below we discuss further climate effects on the phenology of seed fall and the effects of climate change on future crossbill distributions.

4.1 Climate factors influencing the phenology of seed fall

Our results are consistent with the important role of (spring) temperature for different phenological events of plants (Cleland, Chuine, Menzel, Mooney, & Schwartz, 2007; Gordo & Sanz, 2010; Sparks, Jeffree, & Jeffree, 2000). We found that higher spring (April) maximum temperatures were related to earlier seed fall in Scotland, in agreement with previous observations (Hannerz et al., 2002; Worthy, Law, & Hulme, 2006) and with the fact that cone scales spread apart, releasing the seeds from their base, in response to dry conditions and high temperatures (Dawson et al., 1997). Surprisingly, early spring precipitation was not correlated with the timing of seed fall in Scotland. However, higher spring (March) precipitation and lower spring (March and April) maximum temperatures were related to delayed seed fall across all three regions. Perhaps precipitation was less relevant to seed dispersal in Scotland because of its more consistently humid maritime climate. Consistently high humidity in Scotland might also account for why maximum spring temperatures contributed relatively little to the model for the distribution of Scottish crossbills (Figure 4).

4.2 Climate and food plants as determinants of crossbill distributions

Early spring (April) maximum temperature, which best explained the timing of Scots pine seed fall, and Scots pine cover contributed most to predicting the distribution of parrot crossbills (Figure 4). These results were consistent with the occurrence of parrot crossbills depending on Scots pine retaining seeds in its cones in late spring and into summer, and with specialization by parrot crossbills on Scots pine (Cramp & Perrins, 1994; Newton, 1972). In contrast, the distribution of the Scottish crossbill, which presumably evolved in isolated Scots pine forests in the British Isles (Knox, 1990; Nethersole-Thompson, 1975; Summers et al., 2010), was more related to other non-native pines and spruce cover than to Scots pine cover. This result is consistent with the now extensive use of introduced pine and spruce by Scottish crossbills (Summers & Broome, 2012). However, it is worth noting that the restricted distribution of Scottish crossbills and the coarse grid resolution of the Atlas data (Summers & Buckland, 2011) resulted in few occurrences for model building. As mentioned above, the minimal importance of spring temperature on the distribution of Scottish crossbills is perhaps related to the relatively humid marine climate in Scotland. Spruce cover was the main determinant, and April maximum temperature the second-most important determinant of the distribution of common crossbills. This crossbill is widely distributed in Europe and feeds mainly on spruce in central and northern Europe (Cramp & Perrins, 1994; Newton, 1972). The importance of April maximum temperature suggests that seed retention in the spring by Norway spruce is related to temperature as in Scots pine.

4.3 Ranges of crossbills under future climates

Climate change scenarios are expected to shift and reduce the distribution of crossbills in Europe, with a dramatic reduction for the species most specialized on Scots pine, the parrot crossbill. These reductions are the result of at least two factors. First, warming conditions during spring are expected to shift the timing of seed fall so as to increase the window of food scarcity for crossbills (Figure 1). Although earlier cone development in summer with increasing temperatures could act to reduce this window of food scarcity, this is an unlikely response given that Scots pine cones start to develop and become profitable to crossbills at similar times from southern to northern Europe (late July-early August; Marquiss & Rae, 2002; Worthy et al., 2006; E. T. Mezquida, pers. obs.). Second, climate scenarios predict a north-eastwards shift in the distributions of the main food plants (pine and spruce) for crossbills, as previously predicted for many European forest trees (Huntley et al., 1995; Thuiller, 2003). The common crossbill's distribution will contract in the central and southern areas as warmer conditions advance seed fall and thereby expand the period of seed scarcity, and as conifers suffer increased mortality due to drier conditions at their warm-edge range margins (Matías & Jump, 2012; Reich et al., 2015). New areas will potentially become suitable in northern Europe allowing northwards expansion. Parrot crossbills will be further restricted to perhaps only northern Fennoscandia and Russia. This range reduction is the result of future range shifts in Scots pine (Huntley, 1995) and the increase in spring temperature causing a longer interval of seed scarcity, especially in southern Fennoscandia.

Our predictions for Scottish crossbills are partly similar to those from previous simulations (Huntley, Green, Collingham, & Willis, 2007). Suitable areas in Scotland are predicted to remain, but additional areas are predicted for Iceland, Scandinavia and south-central Europe. However, it is doubtful that these small and widely spaced locations would be favourable to a relatively sedentary and localized specialist, as Scottish crossbills have been characterized (Knox, 1990; Marquiss & Rae, 2002; Nethersole-Thompson, 1975). Currently, Scottish crossbills often utilize non-native conifers (Summers & Broome, 2012). Although the use of these non-native conifers should aid in their short-term persistence, a much smaller billed crossbill similar to those specialized on these conifers (e.g., Pinus contorta and Picea sitchensis) in their native ranges in North America (Benkman, 1993; Irwin, 2010) will be favoured over the long term (Summers & Broome, 2012). In addition, common crossbills, which also feed on these non-native conifers in Scotland, could co-occur with Scottish crossbills more frequently, potentially increasing both competition and hybridization between this smaller billed crossbill and the Scottish crossbill (Marquiss & Rae, 2002; Summers, Dawson, & Phillips, 2007). We suspect that the outlook for a unique Scots pine specialist in Scotland is even bleaker than that for the parrot crossbill in northern Europe.

These forecasted range shifts for crossbills are consistent with future predictions for different bird species and diverse local scales (Thomas & Lennon, 1999; Tingley, Monahan, Beissinger, & Moritz, 2009) and with avian responses to changes in vegetation during past climates (Holm & Svenning, 2014). Our results suggest that climate change will impact European crossbills in an indirect way through their influence on the distribution of their food plants (Huntley, 1995; Kissling, Field, & Böhning-Gaese, 2008), timing of seed fall and seed availability (Benkman, 2016; Santisteban et al., 2012), and possibly seed production (Matías & Jump, 2012). This is consistent with increasing evidence that climate change has and will have its greatest impact by altering food resources and trophic interactions (Cahill et al., 2013; Ockendon et al., 2014; Pearce-Higgins & Green, 2014).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Predictions of species distributions and future suitable areas under climate change scenarios have improved by incorporating specific biotic interactions (Araújo & Luoto, 2007; Freeman & Mason, 2015; Li et al., 2015). Avian habitat specialists and species that feed on particular plants are expected to respond mostly to changes in the distribution of vegetation and the plants they rely on (Kissling et al., 2007; Koenig & Haydock, 1999; Preston, Rotenberry, Redak, & Allen, 2008). Crossbills are specialized granivores adapted to specific conifer species (Benkman, 1993, 2003), so their distributions will be influenced by tree responses to changing climate conditions and land use. Spring temperatures, which are strongly linked to the phenology of seed dispersal and thus to seed availability (Benkman, 1987), were also important predictors of the ranges of European crossbills and will affect their resources in the future. We hypothesize that cooler and moist spring conditions were especially critical in allowing crossbills to specialize on Scots pine. Consistent with this, the two crossbill species specialized on Scots pine (i.e., parrot and Scottish crossbills) are distributed in areas of unusual climates relative to the dominant climates of Europe (Ohlemüller et al., 2008). Species with relatively small ranges (such as the Scottish crossbill) in areas of uncommon climates are expected to be especially vulnerable to climate change (Ohlemüller et al., 2008). Besides the forecasted shifts and reductions in ranges for crossbills, changes in climate and land use may pose new threats by modifying movements of crossbills, potentially increasing competition between species and their likelihood of hybridization (Summers & Broome, 2012; Summers et al., 2007) and altering the trophic interactions and selection regimes that presumably led to their diversification.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the European Bird Census Council for providing the data for the European crossbills and the European Forest Institute for providing the tree species maps. We appreciate the comments made by C. Porter and two anonymous referees. We thank the Robert B. Berry Endowment, the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (CGL2010-15687) and REMEDINAL 2-CM research network (S-2009/AMB-1783) for financial support for our research. JCS considers this study a contribution to the Center for Informatics Research on Complexity in Ecology (CIRCE), funded by Aarhus University and Aarhus University Research Foundation under the AU IDEAS programme.

REFERENCES

BIOSKETCH

The authors' research interests include the ecology and evolution of biotic interactions, avian and plant ecology, global change biology, biogeography and biodiversity conservation.

Author contributions: E.T.M., J.-C.S. and C.W.B. conceived and designed the research; E.T.M. and R.W.S. collected the data; E.T.M. analysed the data and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results; and E.T.M. led the writing with contributions from all authors.