Self-reported mental health and the Dobbs decision: Variation by State abortion laws

[Correction added on 7 December 2024, after first online publication: Author Vivekananda Das affiliation have been updated in this version].

Abstract

When a US Supreme Court ruling allowed states to ban abortion, women of childbearing age in the states where abortion became illegal reported higher rates of anxiety symptoms compared to similar-aged women in other states and older women in the same states. This study highlights how people respond to major policy changes and underscores the importance of mental health as a measure of well-being for policymakers and researchers.

Abbreviations

-

- ACS

-

- American Community Survey

-

- DDD

-

- Difference-in-difference-in-differences

-

- GAD-2

-

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (2-item)

-

- HPS

-

- Bureau Household Pulse Survey

-

- LARC

-

- Long-acting reversible contraception

-

- NCHS

-

- National Center for Health Statistics

-

- PHQ-2

-

- Patient Health Questionnaire (2-item)

-

- TRAP

-

- Targeted regulation of abortion providers

1 INTRODUCTION

Abortion is a contentious issue in the US, with a range of conflicting positions on the tradeoffs between protecting unborn children versus the reproductive rights of pregnant women (Alvarez & Brehm, 1995). After 50 years of relatively stable federal policies, the US Supreme Court ruled on the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (No. 19-1392) on June 24, 2022, that the “Constitution does not confer a right to abortion.” The Dobbs case overruled the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, which prevented states from imposing complete bans on access to abortion services. It also immediately resulted in people in certain US states losing access to most abortion services without traveling to another state.

The Court's ruling was not a surprise in June of 2022. The media outlet Politico leaked an advance copy 6 weeks before the official release. To the extent the public trusted this information, it signaled to residents in states with more restrictive abortion laws that access to abortion would soon be even more limited. For women who valued the option to be able to access an abortion in the future, the Dobbs case could have impacted their mental health, mainly in the form of anxiety, as they feared losing a right they held previously.

A rational person in a state with trigger bans may have already “priced in” the potential for restrictions on abortion before the Court's ruling. These states already tended to have restrictions on abortion, including barriers to abortion medications, hospital affiliation requirements for providers, and other burdens that restricted the supply of abortion-related services. Prior studies show these laws effectively restricted access and made abortion less likely in these states (see Lindo et al. (2020), or Lindo and Pineda-Torres (2021) for example).

It remains unclear how much the general public would be expected to respond to such a policy change, especially people living in places with local policies that make abortion unlikely even prior to the Dobbs case. We might expect a wide degree of heterogeneity in how people view this policy change, not only based on the state laws they may face, but also their own view of the costs and benefits of having abortion available as an option.

The Dobbs case highlights a notable distinction between a court ruling directly affecting individuals, particularly women facing or at risk of unplanned pregnancies, and its impact on those who oppose abortion but are unlikely to experience unplanned pregnancies. The perceived detriment for women could potentially be more salient and have larger impacts on their mental health than the gains for opponents of abortion (Coast et al., 2018). Indeed, negative mental health responses are common among women considering an abortion, especially among women living in states with more restrictions on abortion access (Biggs et al., 2020).

There are two notable studies in medical journals that have estimated the effects of the Dobbs ruling on women's1 mental health. The first was by Dave et al. (2023), followed by Thornburg et al. (2024). These studies used biweekly data from the Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey (HPS), the same survey used in our study. Dave and colleagues estimated that female respondents aged 18–44 years old residing in states restricting abortion rights experienced a greater post- and pre-ruling increase in mental distress, a measure that combines anxiety and depression symptom measures, relative to similar-aged women living in states where abortion rights continued to be protected. The authors found no such differential change in this measure for older female respondents over the same period (January 26 to September 28, 2022). Thornburg and colleagues studied a slightly longer time period using the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) measure, which combines symptoms of anxiety or depression. They found a greater post- and pre-ruling increase in the rate of mental distress for those in trigger states versus non-trigger states among females aged 18 through 45 years.

Our study approaches mental health responses to the Dobbs ruling differently. First, we employ a difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) design to isolate the impact of the Dobbs decision on mental health using a stronger counterfactual than the ones used in prior studies. The DDD identification strategy controls for other state-specific time-varying events that may also influence mental health. Second, while the two previous studies used a single mental distress indicator as the outcome variable, we use separate anxiety (GAD-2) and depression (PHQ-2) symptom measures as these are distinct mental health conditions (Beuke et al., 2003). The loss of a right to an abortion is related to a loss of control or autonomy, which has more connections to anxiety than depression. Therefore, the Dobbs decision may have a relationship to anxiety but not likely to depression. Third, based on predictions from the economics literature, we explore heterogeneous effects based on gender, income, marital status, race, labor force attachment, and the presence and age of children in the household. Fourth, we use a more precise set of treatment and control states,2 with more careful considerations of effect sizes and duration, including differences across states based on a range of pre-existing abortion-related policies.

We find that women of childbearing age in the states where abortion became illegal, compared to similar-aged women in other states and older women in the same states, reported higher rates of anxiety, but not depression, after the Politico leak of the Dobbs ruling. At the subgroup level, the most pronounced relative change in anxiety symptoms occurred in women with young children.

These results suggest that policy changes, especially for residents of certain states, have a relationship to anxiety. The estimated impacts also moderate over time, suggesting that after the initial shock of a new policy regime, people's mental health reverts to previous patterns. Nevertheless, measures of self-reported mental health, like those in the Census survey, may prove to be a useful indicator of how policy changes influence people's perceptions of their well-being. Other major policy changes, especially where the authority of policies is transferred from the federal to state levels, may offer further opportunities to understand how local contexts influence how people respond to policy changes.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Responses to abortion bans

Access to abortion is a form of birth control for women who have an undesirable pregnancy. Economic models, including Becker's theory of fertility, as well as household bargaining (Becker, 1976, 1993) offer insightful frameworks in order to make predictions about how the Dobbs decision may influence people's well-being. When states ban abortion services, women effectively lose the option value of terminating a pregnancy, unless they are able to travel to another state or seek out unregulated abortion services. These alternatives substantially increase the costs of abortions for women in these states. Women's demand for abortions is unique in that it is episodic, unpredictable, and also highly stigmatized (Coast et al., 2018). Women who have no expectation of a future pregnancy, or who would never terminate a pregnancy, are not affected by state abortion bans. Women of childbearing age who prefer not to have a pregnancy, however, would be more likely to perceive they have lost an option after the Dobbs ruling, especially younger women (Kelly et al., 2020). Women who lack economic resources and are unable to travel to another state are likely the most affected. This may be especially true for women who already have young children and do not want another child. An abortion ban also increases the importance of the most effective preventative contraception methods. For example, women in states without access to abortion may be more likely to use long-acting reversible contraception (Crespi et al., 2022). While the availability of contraception could help reduce anxiety around an unplanned pregnancy for some women, abortion and preventative contraception are incomplete substitutes, especially for younger women (Myers, 2017). It is important to note there were no major changes in contraception access in 2022 around the time of the Dobbs ruling.

Indeed, statistics on abortion use supports differential responses to the Dobbs ruling. According to the Centers for Disease Control (Kortsmit, 2023), nearly four in five abortions are among women aged 18-34 and the majority already have a child. Other work shows that unmarried women with children were most worried about an unplanned pregnancy (Coverdale et al., 2023; Londoño Tobón et al., 2023).

It should be noted that an alternative for women in states without a legal abortion option is to travel to another state. However, many women are not able to travel or cannot afford the costs and time required (Jerman et al., 2017). At least before the Dobbs ruling, traveling more than 50 miles to obtain an abortion was also quite rare (Fuentes & Jerman, 2019; Myers, 2021; Smith et al., 2022).

There are also likely differential responses to the Dobbs ruling by race, especially since Black and Hispanic women have a higher rate of obtaining abortions than white women (Diamant & Mohamed, 2022). For example, studies by Ogbu-Nwobodo et al. (2022) and Räsänen et al. (2022) found that Black women were more concerned about losing access to abortion services. Lower-income women of color report greater concerns about the negative economic implications of an unwanted pregnancy (Sangtani et al., 2023) and stronger responses to state restrictions on abortions (Jones & Pineda-Torres, 2024).

Surveys show that men are more likely to be opposed to abortion (Loll & Hall, 2019). However, men's response to the Dobbs ruling could vary. Abortion bans could expose single men to greater paternity liability—a woman who does not terminate a pregnancy could demand child and other support (Doan & Schwarz, 2020). On the other hand, men who are in a relationship potentially gain power in a household if they want children. In a simple household bargaining model, men in relationships with women could gain value from the Dobbs ruling (Oreffice, 2007; Smith & Kronauge, 1990).

For people not of child-bearing age, abortion access is unlikely to impact their lives directly. To the extent that the Dobbs ruling is consistent with their beliefs, they may have improved mental health (Singh et al., 2011). This is consistent with studies in political science showing increased satisfaction, efficacy, and positive mental health outcomes for individuals perceived to be on the winning side of a political debate (Davis & Hitt, 2017).

We predict that women of childbearing age, low-income women and those out of the labor force, women who are unmarried, women with young children, and women of color (especially Black or Hispanic women) will be most likely to have greater reported anxiety symptoms after the Dobbs ruling.

2.2 Mental health outcomes

The decision to terminate a pregnancy is associated with stress and anxiety, at least in the short run (Biggs et al., 2017). Jacques et al. (2023) explored COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on abortion based on social media posts on Reddit, finding that people who were at risk of an unwanted pregnancy reported higher levels of concern, including postings that are consistent with stress and anxiety. Similarly, Biggs and Rocca (2022) found that restrictions on abortion access were associated with greater anxiety due to the additional steps, delays, or travel required to obtain care. Women also report general anxiety about pregnancy or becoming pregnant in states where abortion access is limited (Biaggi et al., 2016; Paltrow et al., 2022).

However, the research on mental health and abortion access varies widely, from general population estimates to effects among women who have an unplanned pregnancy and are contemplating an abortion. VanderWeele (2023) discusses the wide range of contexts that can result in mixed evidence that may muddy the policy debate on how abortion laws are related to people's mental health. People's perceptions of abortion restrictions range from strongly positive to strongly negative. The result is that the overall average population effects of abortion restrictions may cancel each other out. We should expect to find concerns about abortion access to be most salient among women at the highest risk of having an unwanted pregnancy (Wisner & Appelbaum, 2023).

2.3 State abortion laws

The abortion access status of each state is tracked by a number of different advocacy groups and in the media. States have changed restrictions on abortion over time, from reducing the number of clinics and weeks into pregnancy that abortions can be performed, to outright ‘trigger bans’ that would go into effect if the Supreme Court ruled to allow states to outlaw abortion. Based on our review of state policies as of the Dobbs ruling in 2022, 22 states had ‘restrictive’ anti-abortion policies in place, including 1) Alabama, 2) Arizona, 3) Arkansas, 4) Georgia, 5) Idaho, 6) Iowa, 7) Kentucky, 8) Louisiana, 9) Michigan, 10) Mississippi, 11) Missouri, 12) North Dakota, 13) Ohio, 14) Oklahoma, 15) South Carolina, 16) South Dakota, 17) Tennessee, 18) Texas, 19) Utah, 20) West Virginia, 21) Wisconsin, and 22) Wyoming. These laws included so-called “6-week” rules that severely limited but did not outright ban abortion.3

A subset of these states had laws which made abortion ’illegal’ in almost all circumstances after the Dobbs decision. These states were 1) Alabama, 2) Arkansas, 3) Idaho, 4) Kentucky, 5) Louisiana, 6) Mississippi, 7) Missouri, 8) Oklahoma, 9) South Dakota, 10) Tennessee, and 11) Texas. People in these states should have widely anticipated no access to abortion in light of the Dobbs decision. People in these states we would predict to have the strongest response to the Supreme Court's ruling.

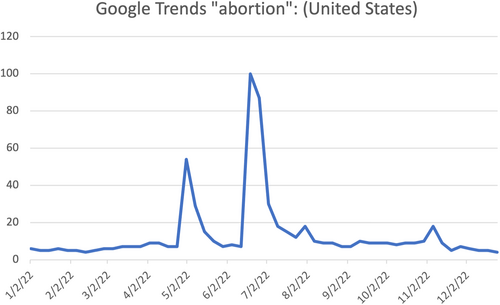

An important question is whether people know their state's abortion laws. Before Dobbs, the Roe v. Wade precedent meant that most people could count on some level of abortion access in their state. Swartz et al. (2020) found that the knowledge of abortion restrictions before Dobbs was quite low in general, and in fact, people's knowledge about abortion laws was most lacking in the most restrictive states. However, the Dobbs decision, and the leak of the Court's draft opinion 6 weeks prior, increased media and the public's attention on state-level abortion policies. Indeed, Google searches for abortion substantially increased initially after the Politico leak and then after the Court's ruling (see Appendix Figure A1).

3 DATA AND METHODS

For this study, we focus on self-reported two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) and two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) scales. These scales are commonly used screening tools in clinical settings and has been shown to be relatively reliable and valid across populations (Siconolfi et al., 2022). The question wording and scoring are provided in Appendix Table A1.

Based on prior work and economic theory, we would have focused on anxiety is the primary dimension on which women will respond to the Dobbs ruling in states where access is most restrictive. Anxiety as measured in the GAD-2 has been shown to be associated with feeliings of control or autonomy, which the Dobbs ruling would be mostly likely to influnce negatively (Hohls et al., 2023).

3.1 Data

The source of the data for this analysis is the HPS, conducted online by the United States Census Bureau in collaboration with other federal agencies, including the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (United States Census Bureau, 2024). The HPS is unique because of its high frequency data collection. The Census Bureau designed it for quickly and efficiently gathering data to measure social and economic impacts of emerging issues (United States Census Bureau, 2024). The HPS gathers a vast array of data on representative samples of American adults from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The sampling frame is derived from the Census Bureau's Master Address File, ensuring comprehensive coverage. Participants receive an invitation via email or text message, containing a unique link to the online survey. The survey is designed to be brief, typically taking less than 20 min to complete, and covers a wide range of topics, including employment status, food security, housing, health, and access to education. To address potential nonresponse bias, sample weights are applied. These weights adjust for differences between survey respondents and the overall population based on demographic benchmarks, such as those provided by the American Community Survey. Data collection occurs in waves, which allows for the continuous monitoring of trends and the identification of emerging issues. We use data from HPS waves 41–49, roughly capturing the period between January and September of 2022–before and after the Dobbs ruling. These waves followed an approximately 2-weeks on, 2-weeks off data collection and dissemination approach.4

The NCHS included the GAD-2 and PHQ-2 scales in the HPS to obtain information on the frequency of anxiety and depression symptoms. Appendix Table A1 shows these items, response options, and scores. Following the methodology used by the NCHS, we add the scores of the two items in each scale and consider a respondent to have symptoms of depression or anxiety if they scored three or higher. Both anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms are binary variables, which take a value of one if the respondent had the symptom and 0 otherwise. The main analytical sample consists of respondents aged 18–34 or 45–64 who answered the GAD-2 and PHQ-2 items in the HPS.

3.2 Descriptive statistics

Figure 1 shows the trends in anxiety (panel A) and depression (panel B) symptoms for younger (18–34) and older (45–64) women from the illegal and the control states (excluding restrictive but not illegal states).

Women reporting anxiety and depression symptoms by age group and states' abortion restriction status. Source: Census Household Pulse Survey (HPS) January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49) The sample consists of respondents who identified as females aged 18–34 or 45–64, lived either in a state where abortion was illegal or in a control state, and answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights. The figure shows an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms among women aged 18–34 in illegal states relative to similar-aged women in control states around the time the Supreme Court case became public.

The top two lines in Panel A suggest that 18–34 year olds reported anxiety symptoms in the comparison states was either equal to or higher than the same in the illegal states between January and April 2022. However, the trends flipped between May and September 2022 as younger respondents from the illegal states were more likely to report anxiety symptoms. The bottom two lines show that within 45–64 year olds, the incidence of anxiety symptoms was higher for the respondents from the illegal states in every wave before and after the Politico leak (May 2022). Taken together, these descriptive findings indicate that in the weeks after the Court's decision in the Dobbs case became public, anxiety symptoms worsened for women age 18–34 living in the illegal states relative to older women in comparison states.

In Panel B, the top two lines suggest a story similar to Panel A: between January and April, younger respondents from the illegal states reported either same or lower depression symptoms in most of the HPS waves; however, they reported higher depression symptoms in most of the HPS waves conducted between May and September. As indicated by the bottom two lines, for the older group, respondents from the illegal states reported higher depression symptoms throughout the studied period; however, the gap between the two groups increased to some extent. Overall, findings in Panel B indicate that in the weeks after the Politico leak, depression symptoms worsened among both younger and older women living in the illegal states.

Table 1 shows the weighted summary statistics of the main sample of women. Descriptively, it appears that, on average, respondents from the two types of states are somewhat different. For example, respondents from the illegal states are more likely to be lower income, have at least one child below 18 in the household and less likely to have a college degree. In the context of this study, more importantly, the average respondents from the illegal and the control states in the two periods (i.e., January–April and May–September, 2022) seem quite similar. This implies that although the HPS is a repeated-cross-sectional survey, on average, similar groups of people responded in the two periods.

| Illegal (11) | +Restrictive (22) | Control (29) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months | Jan-Apr | May-Sep | Jan-Apr | May-Sep | Jan-Apr | May-Sep |

| Proportions: | ||||||

| Income <50k | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.35 |

| Income 50k–150k | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| Income >150k | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Income unkn | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Married | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Employed | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| Children <18 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Children <5 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| White | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Black | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Asian | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Hispanic | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| College | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| Disability | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Mean (SD): | ||||||

| Age | 43 (14.33) | 43 (14.27) | 43 (14.28) | 43 (14.38) | 44 (14.21) | 44 (14.17) |

| Household size | 3.35 (1.67) | 3.33 (1.62) | 3.32 (1.65) | 3.31 (1.63) | 3.40 (1.71) | 3.35 (1.65) |

| N | 15,585 | 14,653 | 32,259 | 29,758 | 51,753 | 44,843 |

- Note: States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. ‘Restrictive’ states (22) include 11 ‘illegal’ states as well as Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Control states (29) include Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New, Hampshire, New, Jersey, New, Mexico, New, York, North, Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode, Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49) The sample consists of respondents who identified as females aged 18-34 or 45-64, lived either in a state where abortion was illegal or in a control state, and answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights.

3.3 Empirical strategy

We estimate relative changes in mental health in several ways. First, we consider the 11 states where abortion was illegal as the ‘treated’ states and states with no abortion restrictions as comparison or ‘control’ states, and ignoring states that have restricted but not policies making abortion illegal. Next, we consider the 22 states where abortion was either illegal or restricted as the treated states. In both cases, we consider the 29 states where abortion was neither illegal nor restricted as the control states. These alternative categorizations help us explore the heterogeneity in the effect of Dobbs decision on mental health across states, which differ based on the restrictiveness in abortion access. We would expect the most robust response would be in states where abortion was illegal post-Dobbs. We consider January-April as the pre-Dobbs period, and May-September as the post-Dobbs period.5

We also estimate differences by age. Following the age groups used by Zandberg et al. (2023), we compare women aged 18-34 to those aged 45-64 as the control group, who are unlikely to seek an abortion. We follow these same age group patterns to estimate the impact of state abortion laws on men.

is a vector of control variables: pre-tax annual household income category, race, Hispanic origin, age, homeownership status, marital status, gender assigned at birth, sexual orientation, educational attainment, number of dependents below 18, and household size. As the HPS is a repeated cross-section, we control for these variables to account for both within- and across-group differences in socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents.

The coefficient of interest is , which is the DDD estimator of the average impact of the Dobbs decision on anxiety and depression symptoms for the younger women (aged 18–34) living in the treated states in the four months following the Politico leak.

Previous studies used a DD approach to study the impact of the Dobbs decision on mental health, but this method may not account for state-specific time-varying factors affecting mental health. Therefore, we use a DDD approach, which includes older women (aged 45–64) from the same states as the younger women (aged 18–34) into the analysis. This DDD method, arguably, is more likely to control for state-specific trends that might affect mental health independent of the Dobbs decision. Therefore, the inclusion of an extra layer of comparison potentially provides a clearer and more accurate estimate of the effect of the Dobbs decision on mental health.

As the preferred empirical strategy, we estimate Equation (1) for the main analytical sample and seven subgroups. These subgroups are based on 1) pre-tax annual household income, 2) marital status, 3) race, 4) disability, 5) unemployment in the last 7 days, and 6) presence of children under 5 in the household. Along with the full sample, we focus at the sub-group level to explore potential heterogeneity in the impact of the Dobbs decision on the mental health of younger women. In all cases, we use the person-level weights provided in the HPS and cluster the standard errors at the state level (the level of ‘treatment’).

The key identifying assumption is that, conditional on the covariates, in the absence of the Politico leak of the Dobbs decision, the gap in mental health outcomes between younger (18–34) and older (45–64) respondents in the treated states would have trended the same way as the gap in outcomes between younger and older respondents in the control states.

We also explore whether the impact of the Dobbs decision on mental health varied depending on four state-level policies on health care access: Medicaid expansion, Medicaid coverage of family planning services, targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP), and pharmacy access policy for contraception.

As of 2022, only 12 states did not offer expanded Medicaid under federal provisions provided in 2014: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2024). Potentially women in these states face even more barriers to health care, including contraception and abortion (McDonnell et al., 2022), and the Dobbs ruling could make anxiety about abortion access worse in these states.

Some states have federal approval to extend Medicaid eligibility for family planning services (Sonfield, 2017). Given this context, we may find less of an anxiety response among low-income women in these states (Guttmacher Institute, 2023a).6

Targeted regulation of abortion providers laws expanded during the 2010s (Austin & Harper, 2018; Jones & Pineda-Torres, 2024). These laws vary but may require abortion providers to expand their buildings to comply with standards for hospitals, as well as require providers to maintain relationships with hospitals. This restricts the ability of providers to operate and reduces access to abortions. We therefore provide estimates for states with TRAP laws in place as of 2022, although these laws are highly correlated with restrictive states (Guttmacher Institute, 2023c).7

Lastly, state-level pharmacy access policies for contraception may reduce anxiety following the Dobbs decision. By allowing pharmacists to prescribe hormonal contraceptives, these policies enhance accessibility to birth control, especially for individuals in rural or underserved areas who face barriers to visiting a healthcare provider. Therefore, the Dobbs ruling could make anxiety about abortion access worse in states without these policies. We provide estimates seperately for these states (Guttmacher Institute, 2023b).8

4 FINDINGS

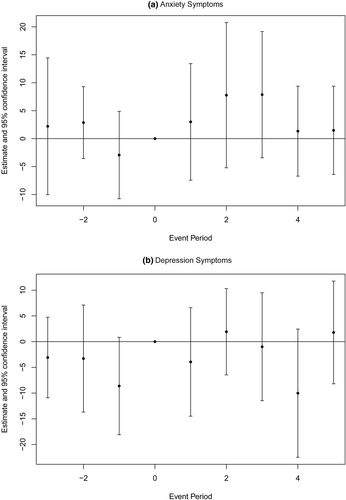

First, we examine the validity of the conditional parallel trends assumption based on the findings shown in Figure 2. Panel A and B show the estimated coefficients for anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively. For both outcomes, the coefficients in the periods before the reference period (i.e., the period immediately before the Politico leak) are statistically insignificant as the 95% confidence intervals intersect the origin for all three periods. These findings suggest that, conditional on the covariates, in the periods before the Politico leak, the gap in mental health outcomes between younger (18–34) and older (45–64) women in the illegal states was moving in parallel to the gap in outcomes between younger and older women in the control states. The evidence of conditional parallel pre-trends supports the validity of the conditional parallel trends assumption.

Relative changes in anxiety and depression symptoms among women before and after the politico leak of the supreme court's dobbs decision. Source: Census Household Pulse Survey (HPS) January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49) The sample consists of respondents who identified as females aged 18–34 or 45–64, lived either in a state where abortion was illegal or in a control state, and answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Person-level weights. “0” is survey wave 45 (conducted between April 27 and May 9, 2022) which captures May 3, the date of the Politico leak of the Supreme Court's Dobbs decision. Figure shows a relative increase in reports of anxiety symptoms (although not significant at the 5% significance level) for women aged 18–34 living in states where abortion became illegal after the Dobbs decision.

Next, we focus on unconditional DDD findings. Table 2 shows the mean rates of anxiety and depression symptoms before and after the Dobbs decision for women by age group and the abortion policy of their state. Women aged 18-34 in illegal states reported a 3.42 point post- and pre-Dobbs increase in anxiety symptoms (1). Similar aged women in control states reported a slight reduction in anxiety symptoms (−0.83, 2). On the contrary, women aged 45-64 in illegal states reported a 2.61 point (3) increase in anxiety symptoms, while similar-aged women in control states reported a 2.33 point (4) increase. The net difference between 1 - 2 and 3 - 4 (DDD) is 3.97, which suggests a large relative increase for the women aged 18–34, given a pre-Dobbs mean anxiety score of 43.15–about a 9% marginal increase relative to the baseline period mean for this group. The estimates for the depression symptoms are similar in direction, but smaller in most cases, and the relative differences across age groups are not statistically significant. The main effect appears to be reported anxiety symptoms among women age 18–34 in illegal states.

| Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Illegal State age 18–34 | ||

| Post | 46.57 | 35.14 |

| Pre | 43.15 | 34.05 |

| 1 = post-pre | 3.42** (1.11) | 1.09 (1.06) |

| Control State age 18–34 | ||

| Post | 44.26 | 32.65 |

| Pre | 45.09 | 34.39 |

| 2 = post-pre | −0.83 (0.62) | −1.74** (0.58) |

| DD1 = 1 - 2 | 4.25*** (1.23) | 2.83* (1.17) |

| Illegal State age 45–64 | ||

| Post | 34.01 | 28.33 |

| Pre | 31.4 | 25.51 |

| 3 = post-pre | 2.61*** (0.63) | 2.82*** (0.60) |

| Control State age 45–64 | ||

| Post | 30.89 | 22.58 |

| Pre | 28.56 | 21.02 |

| 4 = post-pre | 2.33*** (0.35) | 1.56*** (0.31) |

| DD2 = 3 - 4 | 0.28 (0.71) | 1.26. (0.65) |

| DDD = DD2-DD1 | 3.97** (1.25) | 1.56 (1.16) |

- Note: States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. Control states (29) include Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New, Hampshire, New, Jersey, New, Mexico, New, York, North, Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode, Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

- Abbreviation: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49) The sample consists of respondents who identified as females aged 18-34 or 45-64, lived either in a state where abortion was illegal or in a control state, and answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights.

Table 3 shows the findings of the DDD specification shown in Equation (1) estimated using weighted linear regression with state and period fixed effects. Columns (1) and (2) show the estimated effects of the Dobbs ruling on anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively. For the main analytical sample, estimates suggest the decision, on average, increased anxiety symptoms by 3.59% points in the post-Dobbs period among women aged 18–34 living in the illegal states. This estimate is close to the one shown in Table 2. The estimated effect could be as large as 7.24 based on 95% confidence interval. Appendix Table A4 shows a 43.15% prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms among women aged 18-34 in the pre-Dobbs period in the illegal states. Therefore, the estimated effect of 3.59% point increased anxiety refers to about a 8% point increase in anxiety symptoms compared to the pre-Dobbs period, which is a relatively large effect.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | |

| Overall (N = 126,834) | 3.59. (1.81) | 1.28 (2.43) |

| [−0.07, 7.24] | [−3.64, 6.20] | |

| Income <50k (N = 39,430) | 2.91 (3.44) | 0.70 (4.05) |

| [−4.06, 9.87] | [−7.49, 8.88] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 54,263) | 6.03. (3.56) | 3.43 (2.34) |

| [−1.18, 13.23] | [−1.30, 8.16] | |

| Income >150k (N = 21,916) | 8.41. (4.47) | 8.87* (4.00) |

| [−0.62, 17.44] | [0.77, 16.97] | |

| Non-married (N = 62,074) | 4.69 (2.85) | 0.76 (3.43) |

| [−1.08, 10.47] | [−6.17, 7.70] | |

| Married (N = 64,256) | −0.07 (2.17) | 2.35 (1.89) |

| [−4.46, 4.32] | [−1.47, 6.18] | |

| Black (N = 12,048) | 0.34 (5.14) | −8.33 (5.32) |

| [−10.05, 10.74] | [−19.08, 2.43] | |

| White (N = 100,716) | 2.91 (2.23) | 1.83 (2.79) |

| [−1.59, 7.42] | [−3.82, 7.48] | |

| Asian (N = 6622) | 17.80** (5.13) | 13.30. (7.63) |

| [7.39, 28.15] | [−2.10, 28.78] | |

| Other (N = 7448) | 9.32 (8.50) | 5.27 (9.19) |

| [−7.88, 26.52] | [−13.32, 23.87] | |

| Hispanic (N = 13,881) | 3.05 (5.61) | 4.69 (5.03) |

| [−8.30, 14.39] | [−5.50, 14.87] | |

| Disability (N = 5408) | 14.60 (13.4) | 29.00 (17.3) |

| [−12.48, 41.64] | [−5.85, 63.95] | |

| No disability (N = 121,426) | 3.92* (1.67) | 1.18 (2.43) |

| [0.54, 7.29] | [−3.73, 6.10] | |

| In labor force (N = 88,411) | 3.99. (2.19) | 2.88 (2.26) |

| [−0.44, 8.42] | [−1.68, 7.44] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 38,064) | 3.21 (2.88) | −1.18 (3.62) |

| [−2.61, 9.04] | [−8.51, 6.14] | |

| No children (N = 85,567) | 2.96 (2.28) | −1.31 (2.73) |

| [−1.65, 7.57] | [−6.84, 7.21] | |

| Children <5 (N = 11,698) | 16.80** (5.62) | 8.97. (4.94) |

| [5.48, 28.20] | [−1.01, 18.96] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 32,276) | 2.56 (2.99) | 4.57 (3.61) |

| [−3.49, 8.61] | [−2.72, 11.87] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate and standard error of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Abbreviation: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

Regarding the impact on subgroups, Table 3 shows some interesting patterns. Each estimate is the result of a regression model restricted to the population indicated in the far left column. For anxiety symptoms, the estimates for the three income groups intersect zero, meaning they are not statistically different from zero at the 5% significance level. However, the estimated confidence intervals show larger increases in anxiety symptoms for middle and upper income groups, reaching as high as 17.44 points for the highest income group. This could reflect greater awareness of the Dobbs decision among higher-income women, or increased anxiety about restricted abortion access. It is notable that the mean anxiety rate for higher income women is quite low (about 27 in the pre-Dobbs period in the illegal states, per Appendix Table A4), implying large marginal effect sizes.

The estimates also appear larger among Asian women and women in the labor force. The largest estimated increases are among women with children under age five–with the possibility of an effect as large as 28.2 points–a very large increase in anxiety symptoms. This is a group for whom pregnancy was a recent event, and the burden of an unplanned pregnancy may be viewed as especially burdensome.

In column (2) of Table 3, for the main analytical sample, there is no strong evidence of an increase in depression symptoms that is large in magnitude or statistically significant. At the subgroup level, the effect is significantly different from 0 at the 5% significance level only among women aged 18–34 with household income over $150,000. Although we find suggestive evidence of increased depression symptoms for the groups for whom increase in anxiety symptoms was higher (e.g., Asian, those with children under age five), overall, there appears to be less robust evidence suggesting that the Dobbs decision impacted depression symptoms.

Table 4 shows the findings of re-estimating Equation (1) for the same age groups, but among women living in all ‘restrictive’ states, including the illegal states estimated in Table 3. The patterns and trends in Table 4 are similar but smaller in magnitude and with larger standard errors. The estimates for these 22 states with a range of abortion restriction are less precise. Only the Asian subgroup has an estimate statistically different from zero. The upper bounds of the confidence intervals still show that higher income women had larger increases in anxiety symptoms, as do non-married women, women with disabilities, and women with young children. The differences between the two tables suggest that there was a stronger response in terms of reported anxiety symptoms in the illegal states: Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. When adding in the states with restrictions but not outright bans (Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming), the average effects of Dobbs on mental health are lessened.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Symptoms | Depression Symptoms | |

| Overall (N = 158,613) | 1.39 (2.16) | 0.61 (2.39) |

| [−2.95, 5.72] | [−4.19, 5.41] | |

| Income <50k (N = 50,158) | 1.38 (2.87) | 0.49 (4.01) |

| [−4.39, 7.16] | [−7.55, 8.54] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 68,451) | 4.80 (2.96) | 3.46* (1.51) |

| [−1.14, 10.74] | [0.44, 6.49] | |

| Income >150k (N = 26,064) | 2.79 (5.42) | 7.02. (3.62) |

| [−8.11, 13.67] | [−0.24, 14.29] | |

| Non-married (N = 76,663) | 2.51 (3.00) | 0.41 (3.27) |

| [−3.52, 8.54] | [−6.16, 6.99] | |

| Married (N = 81,335) | −1.84 (2.19) | 1.12 (1.88) |

| [−6.23, 2.53] | [−2.65, 4.90] | |

| Black (N = 15,076) | −3.59 (4.75) | −11.90* (4.67) |

| [−13.13, 5.95] | [−21.27, −2.52] | |

| White (N = 127,371) | 0.94 (2.24) | 1.44 (2.60) |

| [−3.55, 5.43] | [−3.88, 6.65] | |

| Asian (N = 7372) | 14.60** (4.43) | 10.80. (5.79) |

| [5.72, 23.51] | [−0.82, 22.46] | |

| Other (N = 8794) | 10.10. (5.93) | 9.35 (6.07) |

| [−1.84, 21.98] | [−2.84, 21.54] | |

| Hispanic (N = 15,967) | 5.53 (6.04) | 7.14 (5.51) |

| [−6.61, 17.67] | [−3.93, 18.21] | |

| Disability (N = 6881) | −1.46 (11.0) | 20.80 (13.10) |

| [−23.56, 20.63] | [−5.46, 47.14] | |

| No disability (N = 151,732) | 1.67 (2.15) | 0.35 (2.32) |

| [−2.65, 9.58] | [−4.32, 5.01] | |

| In labor force (N = 110,243) | 2.01 (2.38) | 0.87 (2.48) |

| [−2.77, 6.78] | [−4.12, 5.86] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 47,927) | −0.60 (3.61) | −0.10 (3.47) |

| [−7.86, 6.66] | [−7.07, 6.88] | |

| No children (N = 106,591) | 1.68 (2.39) | 0.10 (2.52) |

| [−3.12, 6.48] | [−4.96, 5.15] | |

| Children <5 (N = 15,217) | 9.75. (5.81) | 5.80 (4.75) |

| [−1.93, 21.43] | [−3.75, 15.35] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 40,552) | −1.25 (4.37) | 1.90 (4.70) |

| [−10.03, 7.53] | [−7.54, 11.34] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate and standard error of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. The 22 ‘illegal’ or ‘restrictive’ states include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

- Abbreviation: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

Furthermore, we re-estimate Equation (1) by dropping the state fixed effects and using four control variables capturing state-level policies on healthcare access. These variables are: 1) Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion, 2) Eligibility for Medicaid coverage of family planning services, 3) Pharmacy access policies for contraception, and 4) TRAP. These findings are shown in Appendix Table A5. The estimates of this alternative estimation is quite similar to the main findings (as shown in Table 3). Additionally, we re-estimate Equation (1) by conditioning the main analytical sample to each of the four aforementioned state-level policies (i.e., depending on the presence or absence of these policies). As Medicaid primarily provides benefits to lower-income people, we consider only those who lived in a household with annual income less than $35,000 in the relevant samples. Appendix Table A6 shows these estimates. Based on these findings, it appears that the Dobbs decision was linked to greater increase in anxiety symptoms among reproductive-age women living in illegal states when the analysis is conditioned on lower-income respondents living in (1) Medicaid expansion states, (2) states with Medicaid coverage of family planning services, and (3) states with no TRAP policies. We find larger estimates for women located in states without waivers, and smaller estimates for women in TRAP states—this is consistent with these women already knowing that their access to abortion is limited prior to the Dobbs ruling.

Finally, Table 5 shows the findings of re-estimating Equation (1) for men, and the Group variable takes a value of 1 for men aged 18-34 and the State variable takes a value of 1 for the ‘illegal’ states, and 0 for the control states, similar to Table 3 (but for men instead of women). These results are the opposite of those among women of a similar age. Relative to older men, and to men in control states, men in ‘illegal’ states show lowered rates of anxiety symptoms–about 7 points lower, on average. Looking at the subgroup estimates, conditional on being married, the estimated relative decrease in anxiety symptoms could be as large as 19.76 points. White men show the largest decrease in anxiety symptoms, again relative to older men and men in control states. Hispanic men and men who are not in the labor force also show large relative reductions in anxiety symptoms after Dobbs, as do men with no children.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | |

| Overall (N = 83,398) | −7.05* (2.72) | −4.86 (3.01) |

| [−12.56, −1.55] | [−10.94, 1.23] | |

| Income <50k (N = 18,622) | −9.35 (5.83) | −6.75. (3.85) |

| [−21.15, 2.44] | [−14.54, 1.04] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 35,975) | −4.44 (3.59) | −3.40 (4.78) |

| [−11.69, 2.82] | [−13.08, 6.27] | |

| Income >150k (N = 21,782) | 2.77 (4.33) | −1.56 (4.20) |

| [−5.99, 11.53] | [−10.06, 6.94] | |

| Non-married (N = 35,217) | −3.38 (3.78) | −0.33 (3.83) |

| [−11.03, 4.26] | [−8.07, 7.41] | |

| Married (N = 47,902) | −10.80* (4.46) | −8.09 (5.07) |

| [−19.76, −1.74] | [−18.33, 2.15] | |

| Black (N = 5333) | 14.50 (13.80) | 5.07 (11.30) |

| [−13.41, 42.41] | [−17.86, 28.00] | |

| White (N = 66,758) | −9.09** (3.05) | −7.62* (3.38) |

| [−15.26, −2.93] | [−14.45, −0.79] | |

| Asian (N = 6936) | 8.66 (9.48) | 13.3 (8.16) |

| [−10.52, 27.84] | [−3.19, 29.83] | |

| Other (N = 4371) | −16.60 (11.10) | −10.20 (10.20) |

| [−39.04, 5.89] | [−30.73, 10.38] | |

| Hispanic (N = 8812) | −17.00*** (4.58) | −6.23 (4.73) |

| [−26.26, −7.72] | [−15.79, 3.33] | |

| Disability (N = 2169) | −48.00. (23.8) | −6.93 (20.6) |

| [−96.17, 0.16] | [−48.59, 34.73] | |

| No disability (N = 81,229) | −4.98. (2.66) | −4.72 (2.82) |

| [−10.36, 0.40] | [−10.42, 0.98] | |

| In labor force (N = 64,826) | −1.73 (2.66) | −3.39 (2.60) |

| [−7.10, 3.65] | [−8.66, 1.87] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 18,321) | −22.82** (7.95) | −7.17 (6.30) |

| [−38.91, −6.73] | [−19.92, 5.58] | |

| No children (N = 57,923) | −6.22* (2.96) | −1.61 (3.51) |

| [−12.21, −0.23] | [−8.70, 5.48] | |

| Children <5 (N = 6066) | 1.55 (5.37) | −20.9** (6.39) |

| [−9.38, 12.41] | [−33.85, −8.00] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 20,233) | −10.70 (7.12) | −8.57 (7.92) |

| [−25.06, 3.76] | [−24.59, 7.46] |

- Note: ‘***’ , ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate and standard error of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Abbreviation: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

These estimates suggest the Dobbs decision had modest effects on depression symptoms among men living in the states where abortion became illegal, especially among white men and men with children. The overall estimates for depression are not statistically different from zero in the main estimates, but the estimate could be as large as −10.94. These estimates for men are striking when compared to the estimates among women in the same states and same age groups–the perceptions of the Dobbs ruling are quite different. Among women the decision increased anxiety symptoms. Among men, it reduced it, relative to overall trends.

5 DISCUSSION

Based on a DDD framework, it appears women of childbearing age expressed relatively higher rates of anxiety symptoms in response to the Dobbs ruling, at least for the first several weeks after Politico initially leaked the decision. These impacts were the largest among females in the “trigger” states where abortion was banned after the Dobbs ruling.

These estimates are for women of childbearing age (18–34) in the states where abortion became illegal, compared to older women (age 45–64), and women in comparison states with continued access to abortion. Women with children under age five reported larger relative increases in anxiety.

The effects of the Politico leak of the Dobbs ruling are dependent on people's awareness of abortion laws and perceptions of how the Court's ruling would impact future abortion access. The fact that the impact was greater among higher-income women may reflect their engagement with abortion policy news and information, for example, rather than perceptions about their access to abortion. Higher-income women would be more likely to be able to afford to travel to a state with legal abortions, which means they likely would still view abortion as a potential option (Myers, 2021). Lower-income women are likely to experience an actual reduction in abortion (Bailey et al., 2022). Future research could further estimate how the level of awareness and perceptions of these policies contributed to these responses. It is possible that people's initial perceptions of abortion restrictions were based on incomplete information.

While we predicted that women with young children would have more anxiety as a result of the Dobbs ruling, our estimate for this group is quite large (16.8 points in illegal states, nearly a 40% marginal effect). Mothers of young children have less ability to travel to obtain an abortion due to their care taking responsibilities, which could explain some of this magnitude. It is also possible these mothers reported higher anxiety post-Dobbs because they recently had a child and the costs of an unintended pregnancy were likely fresh in their mind. Potentially recall bias explains some of this result (Hall et al., 2017, 2019).

The differential impact of the Dobbs decision on the mental health of women and men in states where abortion became illegal after the Dobbs ruling are striking. Also, in states without abortion bans, men reported more anxiety symptoms after the Dobbs ruling, but not in states where abortion was illegal (see Appendix Table A3). The largest impact was among white men, men who were married, and men who were not working. These may reflect men who viewed abortion bans as being consistent with their political and religious views (Davis & Hitt, 2017; Singh et al., 2011). These men may also view abortion restrictions as increasing their household-level bargaining power, allowing them to actualize their preferences for having more children even if their partner does not share those preferences. Younger men, especially married men, may have gained bargaining power post-Dobbs.

It is important to highlight both the magnitude and duration of these estimates. Compared to other studies using the GAD-2 examining anxiety and worry, the size of these estimates overall, and even among most of the sub-populations we examined, are not large (Hohls et al., 2023). Most of these estimates are suggestive of a relationship between self-reported anxiety and the Dobbs ruling, but many are marginally statistically significant. The overall trends are suggestive there is a relationship between anxiety reports and Dobbs, but it is a noisy signal. Moreover, the event study results show that the impact among women reverted back to pre-Dobbs levels within about 2 months of the Politico leak. As the reality of the new policy became established, people's mental health might have adjusted. While states with abortion bans remained unchanged (and some restrictive states moved to illegal status), other state actions might have provided some support for women who needed evidence that there would remain some abortion access. For example, Kansas voters rejected a constitutional amendment banning abortion in August 2022.

Other reasons to treat these estimates with caution include the fact that the Census Household Pulse is a relatively new data source using an online sample and the data quality is uneven (Bradley et al., 2021). Also, the two-item anxiety (PHQ-2) and depression (GAD-2) measures are designed mainly as a brief clinical diagnosis rather than population-level metric (Staples et al., 2019). Also, these estimates are based on just nine survey periods in 2022, with four pre- and post- Dobbs periods. The unit of treatment is a state, with either 11 or 22 states as the treatment group, and 29 as the control group. We use robust clustered standard errors at the unit of treatment (states), but this is a relatively small number of clusters for estimation (Abadie et al., 2023).9 It is also important to note that the 11 states with illegal abortion laws should all experience similar treatments at the same time, providing the cleanest estimates using traditional state clustered errors.10 As expected, the confidence intervals are wider with the smaller sample, with fewer estimates statistically significant at the 95 or 90% level.

These findings are also instructive for studies on well-being and how people perceive policy changes, at least in the short run. The mental health losses that women of childbearing age report in response to the Dobbs decision are not necessarily comparable to the relative gains that men report, but researchers trying to explore overall well-being in a population should be cautious about such a high degree of underlying heterogeneity in responses. A study on overall responses to Dobbs, for example, may show no net changes in mental health since one group's response would counteract that of another.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the impact of the Supreme Court's Dobbs ruling in 2022 on self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms across different demographic groups. We found that women of reproductive age, especially those with young children, living in states where abortion became illegal after the ruling reported greater increases in anxiety symptoms relative to both older women living in the same states and similar-age women living in other states where abortion access remained unchanged. Younger men in states where abortion became illegal showed a relative improvement in anxiety, especially white men and men without children.

At a minimum, these findings indicate that people who responded to the Census Pulse survey had some awareness of abortion policy changes in their state, at least in terms of how they responded to the questions on mental health in the survey. How researchers should view these self-reported mental health changes remains unclear, however. These impacts seem to disappear as the realities of these state abortion laws settled in, and perhaps various alternative options for women became less uncertain. Nevertheless, mental health likely reflects people's attitudes and opinions, and these measures may be a useful proxy for policymakers as well as researchers trying to understand population-level well-being. Most importantly, these findings show great heterogeneity in how people respond to major policy changes, suggesting caution in how researchers interpret policy evaluations. The gains reported by ‘winners’ may be offset by the negative responses among the ‘losers’ in a pluralist system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by University of Wisconsin-Madison's Collaborative for Reproductive Equity (CORE), which supplied administrative and research management support for the project through a small grant program at the Center for Demography and Ecology (CDE). The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of any agency or institution.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

ENDNOTES

- 1 We use the term ‘women’ to refer to HPS respondents who selected “female” in response to the question asking about sex assigned at birth, although we also acknowledge that self-reported gender and sex may not be as precise as measured in birth or other administrative records.

- 2 We include Alaska, Florida, Montana, Nebraska, and Virginia as control states where abortion was available in 2022. Prior studies omitted these states.

- 3 Our main results use all 50 states and Washington DC. Some advocates may exclude some states based on how laws were being implemented or were uncertain as of 2022 subject to state court cases. We are careful not to selectively exclude states from the control group (28 states as well as Washington, DC), and even if we exclude states with some uncertainty, our estimates are similar.

- 4 Appendix Table A2 shows the data collection period, number of respondents, and response rate for each wave.

- 5 HPS wave 45 is the beginning of the post-treatment period based on the on May 2, 2022 Politico leak.

- 6 Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

- 7 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin.

- 8 Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia.

- 9 Given that the Census designed the HPS to observe the US population, these clustered standard errors might be viewed as producing more conservative, lower-bound confidence intervals.

- 10 We provide bootstrapped clustered standard error estimates (1000 repetitions and Rademacher weights) in the Appendix Tables A7, A8, and A9. Several estimates are no longer statistically significant although the confidence intervals have a similar distribution.

APPENDICES

Google searches for ‘Abortion’ in 2022. Source: Google Trends. Google Trends search results 2022 show a spike for the search term abortion when the Supreme Court case was made public.

| Adapted scale | Variable | Question | Response options |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-2 | INTEREST | Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things? Select only one answer. | Not at all = 0 |

| Several days = 1 | |||

| More than half the days = 2 | |||

| Nearly every day = 3 | |||

| DOWN | Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? Select only one answer. | Not at all = 0 | |

| Several days = 1 | |||

| More than half the days = 2 | |||

| Nearly every day = 3 | |||

| GAD-2 | ANXIOUS | Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge? Select only one answer. | Not at all = 0 |

| Several days = 1 | |||

| More than half the days = 2 | |||

| Nearly every day = 3 | |||

| WORRY | Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the not being able to stop or control worrying? Select only one answer. | Not at all = 0 | |

| Several days = 1 | |||

| More than half the days = 2 | |||

| Nearly every day = 3 |

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

| Wave | Event period | Data collection | Respondents | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | −3 | December 29 – January 10 | 74,995 | 7.2 |

| 42 | −2 | January 26 – February 7 | 75,482 | 7.2 |

| 43 | −1 | March 2 – March 14 | 84,158 | 7.9 |

| 44 | 0 | March 30 – April 11 | 63,769 | 6.0 |

| 45 | 1 | April 27 – May 9 | 61,767 | 5.8 |

| 46 | 2 | June 1 - June 13 | 62,826 | 6.2 |

| 47 | 3 | June 29 - July 11 | 58,304 | 5.7 |

| 48 | 4 | July 27 - August 8 | 46,801 | 4.4 |

| 49 | 5 | September 14 - September 26 | 50,937 | 4.7 |

| Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Illegal State age 18–34 | ||

| Post | 35.52 | 31.56 |

| Pre | 35.47 | 32.70 |

| 1 = post-pre | 0.05 (1.35) | −1.15 (1.32) |

| Control State age 18–34 | ||

| Post | 36.00 | 32.51 |

| Pre | 32.88 | 30.68 |

| 2 = post-pre | 3.12*** (0.72) | 1.82** (0.71) |

| DD1 = 1 - 2 | −3.07* (1.47) | −2.97* (1.42) |

| Illegal State age 45–64 | ||

| Post | 26.25 | 22.22 |

| Pre | 22.09 | 18.97 |

| 3 = post-pre | 4.16*** (0.73) | 3.26*** (0.69) |

| Control State age 45–64 | ||

| Post | 22.11 | 18.59 |

| Pre | 21.51 | 17.13 |

| 4 = post-pre | 0.60 (0.38) | 1.45*** (0.36) |

| DD2 = 3 - 4 | 3.56*** (0.79) | 1.80* (0.73) |

| DDD = DD2-DD1 | −6.63*** (1.44) | −4.77*** (1.37) |

- Note: States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. ‘Restrictive’ states (22) include 11 ‘illegal’ states as well as Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Control states (29) include Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New, Hampshire, New, Jersey, New, Mexico, New, York, North, Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode, Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49) The sample consists of respondents who identified as males aged 18–34 or 45–64, lived either in a state where abortion was illegal or in a control state, and answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights.

| Anxiety | Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illegal | Restrictive | Illegal | Restrictive | |||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Overall | 35.47 | 43.15 | 34.73 | 44.43 | 32.70 | 34.05 | 31.86 | 34.80 |

| Income <50k | 39.09 | 44.51 | 37.57 | 47.06 | 35.63 | 36.58 | 35.34 | 38.58 |

| Income 50k-150k | 38.56 | 44.62 | 33.24 | 41.39 | 35.38 | 35.99 | 29.88 | 29.97 |

| Income >150k | 22.87 | 27.34 | 21.14 | 30.69 | 17.63 | 16.23 | 16.02 | 18.66 |

| Non-married | 36.22 | 45.87 | 36.20 | 48.28 | 35.55 | 38.44 | 35.22 | 40.05 |

| Married | 33.89 | 38.91 | 31.62 | 38.30 | 26.70 | 27.20 | 24.76 | 26.41 |

| Black | 27.78 | 32.92 | 23.62 | 35.79 | 34.18 | 33.28 | 28.01 | 35.62 |

| White | 36.91 | 44.77 | 36.60 | 45.77 | 33.09 | 34.36 | 32.85 | 34.79 |

| Asian | 18.56 | 31.49 | 19.01 | 32.52 | 20.20 | 24.85 | 19.52 | 27.10 |

| Other | 38.39 | 52.30 | 34.57 | 52.88 | 35.46 | 37.23 | 32.12 | 37.53 |

| Hispanic | 33.72 | 41.90 | 31.79 | 43.31 | 28.49 | 32.55 | 29.72 | 34.64 |

| Disability | 85.53 | 39.99 | 75.45 | 52.05 | 34.96 | 34.58 | 36.60 | 46.94 |

| No disability | 33.86 | 43.21 | 33.81 | 44.28 | 32.63 | 34.04 | 31.76 | 34.55 |

| In labor force | 29.85 | 43.94 | 31.24 | 45.21 | 29.67 | 33.45 | 29.42 | 34.31 |

| Not in labor force | 51.93 | 41.46 | 46.52 | 42.66 | 41.57 | 35.31 | 40.11 | 35.92 |

| No children | 37.03 | 45.83 | 35.79 | 47.94 | 35.41 | 37.79 | 34.78 | 38.90 |

| Children <5 | 37.53 | 36.40 | 36.19 | 36.27 | 30.32 | 25.11 | 28.04 | 25.90 |

| Children 5-17 | 30.58 | 40.80 | 28.45 | 39.20 | 25.29 | 31.02 | 23.23 | 29.40 |

- Note: States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. ‘Restrictive’ states (22) include 11 ‘illegal’ states as well as Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Anxiety and depression symptoms rates are based on the PHQ-2 and GAD-2 scales, respectively.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-April 2022 (survey waves 41–44). Sample consists of respondents aged 18–34 who answered questions on mental health. Person-level weights.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | |

| Overall (N = 126,834) | 2.60. (1.46) | −1.26 (1.94) |

| [−0.36, 5.56] | [−5.18, 2.66] | |

| Income <50k (N = 39,430) | 0.63 (2.50) | −2.45 (2.55) |

| [−4.44, 5.60] | [−7.61, 2.72] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 54,263) | 5.20. (3.01) | 1.15 (2.69) |

| [−0.89, 11.30] | [−4.30, 6.59] | |

| Income >150k (N = 21,916) | 6.20 (4.70) | 7.25. (4.11) |

| [−3.32, 15.71] | [−1.07, 15.57] | |

| Non-married (N = 62,074) | 3.32 (2.27) | −2.84 (2.95) |

| [−1.28, 7.92] | [−8.81, 3.13] | |

| Married (N = 64,256) | −0.74 (2.00) | 0.75 (1.72) |

| [−4.79, 3.31] | [−2.73, 4.24] | |

| Black (N = 12,048) | 1.92 (4.84) | −6.98 (4.76) |

| [−7.87, 11.71] | [−16.62, 2.65] | |

| White (N = 100,716) | 1.49 (1.87) | −1.54 (2.40) |

| [−2.28, 5.26] | [−6.40, 3.32] | |

| Asian (N = 6622) | 11.1. (6.49) | 15.6* (7.32) |

| [−2.00, 24.23] | [0.75, 30.36] | |

| Other (N = 7448) | 9.02 (7.11) | 1.86 (6.38) |

| [−5.37, 23.41] | [−11.05, 14.77] | |

| Hispanic (N = 13,881) | 0.90 (4.28) | −2.54 (4.47) |

| [−7.75, 9.55] | [−11.58, 6.51] | |

| Disability (N = 5408) | 16.9 (12.3) | 32.3. (16.3) |

| [−8.01, 41.72] | [−0.67, 65.22] | |

| No disability (N = 121,426) | 2.70. (1.52) | −1.71 (1.99) |

| [−0.37, 5.76] | [−5.74, 2.32] | |

| In labor force (N = 88,411) | 2.28 (2.16) | −0.92 (2.15) |

| [−2.09, 6.64] | [−5.26, 3.43] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 38,064) | 3.84 (2.30) | −1.46 (2.90) |

| [−0.81, 8.50] | [−7.32, 4.40] | |

| No children (N = 85,567) | 2.65 (2.19) | −3.66 (2.32) |

| [−1.78, 7.06] | [−8.35, 1.03] | |

| Children <5 (N = 11,698) | 13.8* (5.54) | 6.76 (5.46) |

| [2.60, 25.01] | [−4.27, 17.80] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 32,276) | 1.04 (2.57) | 1.62 (3.07) |

| [−4.16, 6.23] | [−4.59, 7.82] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate and standard error of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term of a model similar to Equation (1) except it excludes state fixed effects and uses four control variables capturing state-level policies on healthcare access. These variables are: 1) Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion, 2) Eligibility for Medicaid coverage of family planning services, 3) Pharmacy access policies for contraception, and 4) Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers. Person-level weights. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

| (1) Anxiety | (2) Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Medicaid expansion (Yes) and income below $35,000 (N = 20,641) | 10.1** (3.62) | 0.99 (4.71) |

| [2.68, 17.45] | [−8.60, 10.60] | |

| Medicaid expansion (No) and income below $35,000 (N = 5973) | 4.73 (7.33) | −1.73 (4.47) |

| [−13.20, 22.66] | [−12.67, 9.21] | |

| Medicaid coverage of family planning services (Yes) and | 3.15 (3.25) | −2.95 (3.23) |

| Income below $35,000 (N = 18,370) | [−3.56, 9.86] | [−9.63, 3.72] |

| Medicaid coverage of family planning services (No) and | 6.83* (2.76) | −2.43 (3.78) |

| Income below $35,000 (N = 8244) | [0.92, 12.74] | [−10.53, 5.67] |

| Targeted regulation of abortion providers (Yes) (N = 57,342) | 1.69 (1.93) | −4.89* (2.28) |

| [−2.35, 5.72] | [−9.67, −0.11] | |

| Targeted regulation of abortion providers (No) (N = 69,492) | 8.36*** (1.81) | 3.21 (1.90) |

| [4.56, 12.14] | [−0.77, 7.19] | |

| Pharmacy access policy for contraception (Yes) (N = 79,699) | 3.22 (4.04) | −1.93 (3.38) |

| [−5.14, 11.58] | [−8.92, 5.06] | |

| Pharmacy access policy for contraception (No) (N = 47,135) | 1.75 (2.29) | −4.71. (2.52) |

| [−3.13, 6.64] | [−10.09, 0.66] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate and standard error of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

| (1) Anxiety | (2) Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 126,834) | 3.59. | 1.28 |

| [−0.86, 9.02] | [−3.54, 8.47] | |

| Income <50k (N = 39,430) | 2.91 | 0.70 |

| [−4.57, 11.75] | [−8.53, 11.28] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 54,263) | 6.03 | 3.43 |

| [−4.35, 12.81] | [−0.81, 11.29] | |

| Income >150k (N = 21,916) | 8.41 | 8.87* |

| [−9.03, 18.60] | [1.97, 24.73] | |

| Non-married (N = 62,074) | 4.69 | 0.76 |

| [−2.37, 13.85] | [−6.77, 10.30] | |

| Married (N = 64,256) | −0.07 | 2.35 |

| [−5.02, 6.19] | [−1.69, 7.11] | |

| Black (N = 12,048) | 0.34 | −8.33 |

| [−10.23, 15.22] | [−19.30, 4.18] | |

| White (N = 100,716) | 2.91 | 1.83 |

| [−2.14, 9.70] | [−3.76, 9.92] | |

| Asian (N = 6622) | 17.80 | 13.30 |

| [−15.40, 47.87] | [−27.30, 76.39] | |

| Other (N = 7448) | 9.32 | 5.27 |

| [−13.61, 25.72] | [−22.91, 21.39] | |

| Hispanic (N = 13,881) | 3.05 | 4.69 |

| [−27.91, 37.57] | [−22.40, 41.53] | |

| Disability (N = 5408) | 14.60 | 29.0 |

| [−13.10, 47.78] | [−24.40, 65.11] | |

| No disability (N = 121,426) | 3.92. | 1.18 |

| [−0.63, 8.71] | [−3.74, 8.30] | |

| In labor force (N = 88,411) | 3.99 | 2.88 |

| [−1.35, 10.85] | [−2.19, 9.84] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 38,064) | 3.21 | −1.18 |

| [−3.34, 9.86] | [−8.64, 8.70] | |

| No children (N = 85,567) | 2.96 | −1.31 |

| [−2.90, 9.67] | [−6.91, 7.90] | |

| Children <5 (N = 11,698) | 16.80. | 8.97 |

| [−0.23, 27.21] | [−6.18, 20.54] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 32,276) | 2.56 | 4.57 |

| [−4.66, 10.97] | [−5.18, 14.92] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. 95% confidence intervals estimated using wild bootstrap with 1000 repetitions. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

| (1) Anxiety Symptoms | (2) Depression Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 158,613) | 1.39 | 0.61 |

| [−4.04, 5.99] | [−4.53, 6.55] | |

| Income <50k (N = 50,158) | 1.38 | 0.49 |

| [−4.97, 8.84] | [−7.84, 10.56] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 68,451) | 4.80 | 3.46* |

| [−2.08, 11.21] | [0.53, 6.94] | |

| Income >150k (N = 26,064) | 2.79 | 7.02. |

| [−11.34, 13.93] | [−1.13, 16.11] | |

| Non-married (N = 76,663) | 2.51 | 0.41 |

| [−4.85, 9.65] | [−6.93, 8.60] | |

| Married (N = 81,335) | −1.84 (2.19) | 1.12 (1.88) |

| [−6.57, 2.68] | [−3.38, 5.34] | |

| Black (N = 15,076) | −3.59 | −11.90* |

| [−14.29, 8.61] | [−20.99, −1.03] | |

| White (N = 127,371) | 0.94 | 1.44 |

| [−4.06, 5.61] | [−3.89, 7.37] | |

| Asian (N = 7372) | 14.60* | 10.80 |

| [1.23, 23.19] | [−7.06, 24.10] | |

| Other (N = 8794) | 10.10 | 9.35 |

| [−3.57, 22.21] | [−6.35, 21.94] | |

| Hispanic (N = 15,967) | 5.53 | 7.14 |

| [−18.06, 27.97] | [−16.25, 27.51] | |

| Disability (N = 6881) | −1.46 | 20.80 |

| [−24.32, 22.77] | [−9.45, 49.73] | |

| No disability (N = 151,732) | 1.67 | 0.35 |

| [−3.63, 6.22] | [−5.00, 5.99] | |

| In labor force (N = 110,243) | 2.01 | 0.87 |

| [−3.45, 7.41] | [−5.12, 6.27] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 47,927) | −0.60 | −0.10 |

| [−9.44, 6.56] | [−8.28, 8.42] | |

| No children (N = 106,591) | 1.68 | 0.10 |

| [−3.71, 6.67] | [−5.58, 6.37] | |

| Children <5 (N = 15,217) | 9.75 | 5.80 |

| [−2.81, 23.04] | [−5.44, 16.21] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 40,552) | −1.25 | 1.90 |

| [−12.26, 7.52] | [−8.86, 12.90] |

- Note: ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. 95% confidence intervals estimated using wild bootstrap with 1000 repetitions. The 22 ‘illegal’ or ‘restrictive’ states include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022–September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

| (1) Anxiety | (2) Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 83,398) | −7.05. | −4.86 |

| [−14.07, 0.07] | [−12.82, 4.01] | |

| Income <50k (N = 18,622) | −9.35 | −6.75 |

| [−26.34, 3.28] | [−17.76, 2.10] | |

| Income 50k-150k (N = 35,975) | −4.44 | −3.40 |

| [−10.86, 8.40] | [−13.22, 11.10] | |

| Income >150k (N = 21,782) | 2.77 | −1.56 |

| [−14.83, 15.87] | [−18.94, 6.60] | |

| Non-married (N = 35,217) | −3.38 | −0.33 |

| [−13.25, 5.75] | [−10.48, 7.93] | |

| Married (N = 47,902) | −10.80. | −8.09 |

| [−21.70, 2.03] | [−17.62, 7.44] | |

| Black (N = 5333) | 14.50 | 5.07 |

| [−28.40, 42.61] | [−29.56, 25.75] | |

| White (N = 66,758) | −9.09. | −7.62 |

| [−14.82, 0.64] | [−14.44, 1.71] | |

| Asian (N = 6936) | 8.66 | 13.30 |

| [−41.98, 45.06] | [−36.31, 43.41] | |

| Other (N = 4371) | −16.60 | −10.20 |

| [−38.44, 16.38] | [−48.43, 23.20] | |

| Hispanic (N = 8812) | −17.00 | −6.23 |

| [−35.74, 10.27] | [−27.10, 22.24] | |

| Disability (N = 2169) | −48.00 | −6.93 |

| [−95.84, 21.54] | [−57.57, 57.96] | |

| No disability (N = 81,229) | −4.98. | −4.72 |

| [−12.61, 1.23] | [−12.55, 3.52] | |

| In labor force (N = 64,826) | −1.73 | −3.39 |

| [−9.75, 3.57] | [−9.92, 3.85] | |

| Not in labor force (N = 18,321) | −22.82. | −7.17 |

| [−38.18, 2.30] | [−23.27, 11.42] | |

| No children (N = 57,923) | −6.22 | −1.61 |

| [−13.25, 1.97] | [−8.50, 8.60] | |

| Children <5 (N = 6066) | 1.55 (5.37) | −20.90* (6.39) |

| [−12.50, 11.48] | [−36.10, −2.47] | |

| Children 5-17 (N = 20,233) | −10.70 | −8.57 |

| [−30.00, 9.06] | [−30.90, 10.49] |

- Note: ‘***’ , ‘**’ , ‘*’, ‘.’. Point estimate of the coefficient of the three-way-interaction term in Equation (1). Person-level weights. 95% confidence intervals estimated using wild bootstrap with 1000 repetitions. States (11) where abortion became effectively ‘illegal’ include Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

- Source: Census Household Pulse Survey January 2022-September 2022 (survey waves 41–49).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the US Census Bureau website: census.gov.