Preparing for colorectal surgery: a feasibility study of a novel web-based multimodal prehabilitation programme in Western Canada

Abstract

Aim

Prehabilitation for colorectal cancer has focused on exercise-based interventions that are typically designed by clinicians; however, no research has yet been patient-oriented. The aim of this feasibility study was to test a web-based multimodal prehabilitation intervention (known as PREP prehab) consisting of four components (physical activity, diet, smoking cessation, psychological support) co-designed with five patient partners.

Method

A longitudinal, two-armed (website without or with coaching support) feasibility study of 33 patients scheduled for colorectal surgery 2 weeks or more from consent (January–September 2021) in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Descriptive statistics analysed a health-related quality of life questionnaire (EQ5D-5L) at baseline (n = 25) and 3 months postsurgery (n = 21), and a follow-up patient satisfaction survey to determine the acceptability, practicality, demand for and potential efficacy in improving overall health.

Results

Patients had a mean age of 52 years (SD 14 years), 52% were female and they had a mean body mass index of 25 kg m−2 (SD 3.8 kg m−2). Only six patients received a Subjective Global Assessment for being at risk for malnutrition, with three classified as ‘severely/moderately’ malnourished. The majority (86%) of patients intended to use the prehabilitation website, and nearly three-quarters (71%) visited the website while waiting for surgery. The majority (76%) reported that information, tools and resources provided appropriate support, and 76% indicated they would recommend the PREP prehab programme. About three-quarters (76%) reported setting goals for lifestyle modification: 86% set healthy eating goals, 81% aimed to stay active and 57% sought to reduce stress once a week or more. No patients contacted the team to obtain health coaching, despite broad interest (71%) in receiving active support and 14% reporting they received ‘active support’.

Conclusion

This web-based multimodal prehabilitation programme was acceptable, practical and well-received by all colorectal surgery patients who viewed the patient-oriented multimodal website. The feasibility of providing active health coaching support requires further investigation.

What does this paper add to the literature?

Optimizing preoperative care for colorectal surgery patients could improve outcomes. Patient experiences of preparing for colorectal surgery could inform future interventions. We report findings from a feasibility study of a patient co-developed web-based preoperative program. There is high demand and very good acceptability of the new prehab program with most colorectal surgery patients setting goals for healthy eating, staying active or reducing stress. Patient-oriented research can help improve the quality of colorectal care.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal surgery is an important component of treatment for gastrointestinal conditions and colorectal cancer, which affects between 7% and 30% of Canadians [1, 2]. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in Canada [3]. Surgery, however, puts significant stress on a body that has a multifactorial pathophysiology, leading to multiple postoperative complications and permanent reduction in functional capacity and quality of life (QoL) [4, 5]. Despite minimally invasive surgical techniques and perioperative Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programmes, complications after colorectal surgery still occur in roughly one-third of patients; specifically, one-fifth of patients experience major complications and one-sixth experience minor complications [6]. Postoperative ileus is one minor complication that affects 10%–30% of colorectal patients and causes significant patient morbidity and reduced QoL [7]. Anastomotic leakage is another postoperative complication that affects 3%–15% of patients but accounts for at least a third of all surgery-specific mortality [8]. Postoperative complications that occur in hospital can increase in-hospital costs by fivefold; this burden is likely to expand due to rising nonemergency surgeries in an ageing population and a greater burden of chronic disease [9, 10]. Thus, reducing postoperative complications remains a public health and policy imperative.

In British Columbia, the average preoperative waiting times for 90% of cases were completed within 21 weeks for colostomy/ileostomy, 21 weeks for laparoscopy and 30 weeks for rectal surgery between June 2023 and August 2023 [11]. There is a growing body of research focused on earlier intervention in this preoperative phase, called prehabilitation, that may serve as a complementary strategy to mitigate the risk of postsurgical complications and reduce the healthcare costs of colorectal surgery by optimizing patients' preoperative physiological reserves [12-17]. Most studies on prehabilitation interventions have typically focused on exercise as the main component, sometimes with nutritional and/or psychological support [18, 19]. In general, these studies have had conflicting results due to small sample sizes, limited external validity beyond the intended target population and study heterogeneity [20]. In addition, this literature exists almost exclusively for colorectal cancer patients, with other non-cancer colorectal conditions that require surgery remaining largely unexamined and not included in prehabilitation programmes [21, 22]. Our prior research on multimodal prehabilitation involved focus groups of colorectal surgery patients, and we found that structured support was needed that was flexible, convenient and provided expert-vetted information appropriate to all subgroups of colorectal patients [23].

Recently, there has been significant interest in telemedicine and telehealth with the presence of the global coronavirus pandemic. Many studies have optimistically articulated the potential of telehealth, but further research is needed to provide evidence of efficacy [24-31]. Recently, a UK charity for cancer patients published guidelines on the concept of ‘universal prehabilitation’ as a self-delivered intervention focused on behaviour change [32]. However, no research on multimodal (universal) prehabilitation has yet explored the role of a digital/telehealth intervention combining smoking cessation, physical activity, diet and psychological support components, with or without active health coaching, to determine the feasibility and potential effects for improving QoL in all colorectal patients.

As a preliminary step to furthering this field of research, we aimed to (1) co-develop a novel web-based multimodal (universal) intervention consisting of four components (smoking cessation, healthy eating, physical activity and psychological support) and (2) test the feasibility of this patient-oriented structured support strategy (hereafter ‘PREP’) for all patients preparing for colorectal surgery in Western Canada.

METHODS

Research design

This feasibility study was conducted in one medium-sized tertiary research hospital (St Paul's Hospital, Vancouver), and eligible patients were recruited by health professionals working at the Colorectal Clinic through a letter of invitation that included a brief description of the study. Patients scheduled for colorectal surgery were contacted by clinical research coordinators to confirm eligibility and a potential willingness to participate. We invited 33 potential patients who had agreed to have colorectal surgery, screened 32 for eligible surgery dates and characteristics (no chemotherapy) and enrolled 28 patients who consented; 25 completed baseline surveys and 21 had information at follow-up and were included in analysis (Figure S1).

Participants

Patients scheduled for an elective colorectal surgical procedure for colorectal or stomach cancer and benign conditions (e.g. Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticular disease, polyps, etc.) were eligible for this study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) scheduled for elective colorectal procedures at the St Paul's Hospital Colorectal Clinic at least 2 weeks following decision for surgery; (2) were aged 19 years and older; and (3) had a good understanding of English to complete the consent form and baseline questionnaires and read the study instructions. Patients were ineligible if: (1) they were diagnosed with late-stage, metastatic colorectal cancer (requiring surgery in less than 2 weeks); (2) their surgeon had not agreed that the research team could approach the patient; or (3) they decided not to pursue surgery.

Web-based multimodal prehabilitation intervention (PREP)

During the period between enrolment and surgery, patients were encouraged to access a website consisting of four main components: smoking cessation, healthy eating, physical activity and healthy coping/psychological support. The components of PREP were chosen based on validated resources from the Strong for Surgery toolkit that emphasizes smoking cessation, being active, nutrition and social support [33]. The stress management aspect of ‘healthy coping’ was especially emphasized in PREP, as our previous work found a need and strong preference for mental/emotional health support [23].

The website was co-developed by a patient advisory group (PAG; n = 5) through four biweekly virtual meetings (May and June 2020) to discuss the content of each topic (resources, descriptions, etc.), the language used, the layout and structure of each webpage and the selection of images and patient quotes. The first meeting aimed to review the goal of the project and the four components of prehabilitation: smoking cessation, diet, activity and coping with stress. Prior to each subsequent meeting, a mock webpage was created for the PAG to review, discuss and suggest changes. The goal of the PAG meetings was to ensure that what information was provided, and how, for each topic (smoking cessation, diet, activity and coping) was appropriate, acceptable and accessible from the patient perspective (https://colorectal.providencehealthcare.org/patient-info/planning-ahead/prep-surgery). The PAG was formed from two formal patient partners who agreed to be named on the grant and three additional patient partners who responded favourably to our initial invitations to join the patient-oriented project. The PAG consisted of patient partners who had undergone colorectal surgical procedures in the past and had been invited from the participant list of our previous focus group research on experiences of and preferences for prehabilitation [23].

The PREP website comprised a front landing page with an overview of preparing for ‘bowel surgery’ and multiple tabs (presurgery, postsurgery, patient connections and more, including FAQ, contact us and about us) at the top row. The presurgery tab had a drop-down menu for ‘quit smoking’, ‘eating well’, ‘staying active’ and ‘coping with stress’. Figure 1 shows the diagram we provided on the front page to illustrate how we designed this prehabilitation programme and the relationship of this new website to other levels of structured support.

Each page included a relevant image, a patient quote from our PAG, a summary of scientific information regarding the benefits of how each topic improves the outcomes of bowel surgery, clear actions patients could take for self-management and a list of expert-vetted resources should patients seek further information on the selected topic (example webpages are available in Appendix S1). The ‘Coping with stress’ webpage was the psychological support component that focused on the importance of a positive mindset, which was considered the most relevant topic by our PAG, and offered six specific evidence-based recommendations for action along with additional resources to aid patients in finding stress-coping strategies, such as advising patients to seek positive support from those around them. Given this recommendation, the website also included a separate webpage to enable patients to connect with other patients who had had bowel surgery through external websites and programmes.

At the bottom of each page was a disclaimer stating: ‘This website is designed for patients of St Paul's Hospital who have planned colorectal surgery. It is strictly for informational purposes to support self-care in preparation for bowel surgery. The information provided is “as is” without warranty of any kind, either express or implied, but not limited to the implied warranties of merchantability, lifestyle change for a particular purpose and non-infringement’. Each page also included a sentence and link directing patients to email the research team should the they desire additional ‘active support’, which was specified as nutritional counselling by a registered dietitian and/or enhanced support by a registered health coach through the Health Coach Alliance™ and Canadian Association for Integrative Nutrition™. If applicable to patients who requested this PREP resource, health coaches were planned to be available to deliver ‘active support’ by telephone through an initial session of about 1 h during which baseline health behaviours and patient-driven modification goals would be discussed. Planned follow-up calls would have been weekly for about 30 min with the goal of reinforcing a patient's education, providing additional planning support and, using a standardized global attainment scale, to record achievement of goals set by the interested patient (as applicable). Analytics of website traffic are given in Figure S2.

Data collection

Data were collected using The University of British Columbia-approved REDCap software, a secure web application for building and managing research data collection instruments. Basic demographic data were extracted from electronic medical records (e.g. age, sex, body mass index) and entered by the clinical research coordinators to ensure privacy and confidentiality. At baseline and at 3-month follow-up, patients were directed to complete the validated EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L instrument, which is a patient-reported outcome survey measuring health-related QoL across five dimensions (self-care, usual activities, mobility, anxiety/depression, pain/discomfort) and is a common indicator of overall health and well-being. Each EQ-5D dimension is divided into five response levels (5L) from ‘no problems’ to ‘extreme problems’. At baseline, the validated Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool is a nutritional assessment tool equivalent to the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) widely used in hospital clinical practice to assess risk for malnutrition and identify patients who would benefit from nutritional care. At the 3-month follow-up, a self-reported patient satisfaction survey collected data to measure acceptability, practicality and demand for the new web-based prehabilitation intervention. The bespoke patient satisfaction survey contained 18 questions, of which five were open-ended for free-text responses, six questions were yes/no, six questions had specified temporal responses and one question was a matrix of 10 subsidiary questions with responses from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’. The survey is provided in Appendix S2.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results of the patient satisfaction survey and health-related QoL from the pre- and postintervention EQ5D-5L questionnaires. We report frequencies (proportions), means and standard deviations (SDs) and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) in tables and figures. We calculated the EQ5D-5L utility scores based on the Canadian version of the E5Q5D-5L value set [34] and compare the differences in mean through visual representation in a boxplot.

RESULTS

The average age of study participants was 52.6 years (SD 6.2 years) and 52% of the study participants identified as female. Reasons for attrition of patients included having less than 2 weeks between reviewing the website and undergoing surgery, having a hold on surgery/no surgery scheduled, feeling overwhelmed by the prognosis, being unable to access the website or surveys or giving no reason for withdrawal. Six (29%) patients had their SGA ratings obtained to measure risk for malnutrition: three patients were ‘severely’ or ‘moderately’ malnourished and three patients were ‘normal’. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics of the study sample.

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 25) |

|---|---|

| Femalea, n (%) | 13 (52) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 51.6 (14.2) |

| ≥50 (n, %) | 13 (52) |

| <50 (n, %) | 12 (48) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 25.04 (3.75) |

| Overweight (BMI = 25–29.9), n (%) | 10 (40) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30), n (%) | 2 (8) |

| Malnutrition riskb, n (%) | 3 (0.12) |

- Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

- a All pronouns provided matched the sex assigned at birth (i.e. all cisgender participants).

- b Based on the Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool (CNST), akin to the Subjective Global Assessment of malnutrition risk.

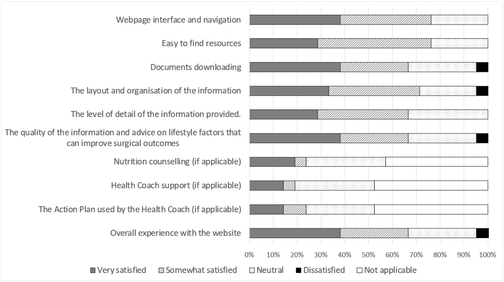

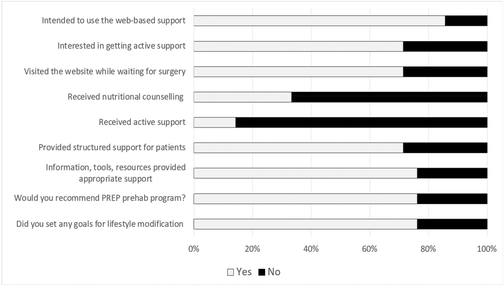

Patient satisfaction with the structured support provided by the web-based PREP programme

Based on quantitative and qualitative data (Table 2), the majority of patients were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the content (67%) and structure (71%) of the information provided, and with the overall experience (67%) of the patient-oriented website. Sixteen (76%) patients were satisfied with the webpage interface and navigation and with the ease of finding resources. Fifteen (71%) patients were satisfied with the layout and organization of the information, with 14 (67%) satisfied with the level of detail of the information provided and the quality of information and advice on lifestyle factors that can improve surgical outcomes. Notably, 18 (86%) patients had intended to use the web-based support and 15 (71%) reported they visited the website while waiting for surgery (Table 3). Most patients (48%) used the website once a month or less and 24% used it two to three times in a month, with use spread throughout the day: a third (33.3%) using it in the morning and a quarter in the evening (Table S1).

| Quantitative data | Qualitative data |

|---|---|

|

‘The information on the website made me aware of things I could do to improve the outcome of my surgery’ ‘Great idea, great info and helpful’ ‘For me, the more information, the better […]’ ‘The prehab website offered a proactive approach that allowed me to consider lifestyle changes I could make to improve my surgical recovery […]’ 'Very informational’ ‘It served its purpose well' ‘All the information on this website is easily found on others’ ‘This is much better than googling to search for information. I had the confidence that the information from your website is reliable, and it's easy to access’ |

- Note: The ‘dissatisfied’ response came from a single patient who described having a very negative encounter with a nurse who was part of standard care and not the PREP intervention itself.

Table 2 also shows that 10 patients (40%) reported that structured support through nutritional counselling and/or a health coach with structured action plans was not applicable. Of note, the survey responses indicated that seven patients indicated they had ‘received nutritional counselling’ and three had ‘received active support’; however, our research team had no record of patient requests to receive the ‘active support’ component from either the nutritional counsellors or health coach as part of the PREP programme. Table 3 shows that patients reported being very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with nutritional counselling (n = 5) and with health coaching (n = 4). Overall, three-quarters (76%) of patients felt that the information, tools and resources provided appropriate support and would recommend the PREP prehabilitation programme.

| Quantitative data | Qualitative data |

|---|---|

|

‘It was great, […] if I could have used it more, it would have been very beneficial. I would highly recommend it to all surgical patients’ ‘I felt extremely positive after the surgery … Thanks again for providing this service’ ‘I would recommend it’ ‘It helped’ ‘Great guidance in a time of concern’ ‘I didn't have access to the tool’ ‘I didn't get a good chance to use the site.[…] I had many work obligations in advance of my surgery’ ‘I didn't have an opportunity to participate’ |

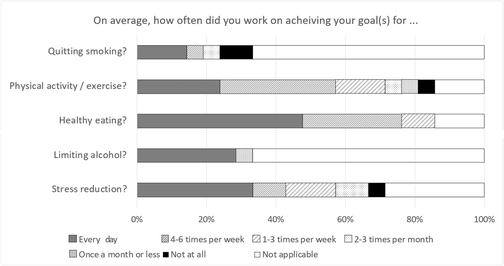

Patient lifestyle modification goals for prehabilitation before colorectal surgery

As shown in Table 3, 16 patients (76%) had set a goal for lifestyle modification prior to colorectal surgery. Table 4 gives the details of these goals and shows that, for the majority of patients (n = 14), the goals of quitting smoking and limiting alcohol were not applicable. When patients did set these goals, six patients aimed to limit alcohol every day and three sought to quit smoking every day as part of preparing for surgery. The most common lifestyle goals for colorectal surgery patients were healthy eating (86%) and/or staying active (81%)—only three patients reported that these goals were ‘not applicable’. Sixteen patients worked on healthy eating every day or four to six times per week, and 14 patients worked on staying active every day or four to six times per week. In addition, 14 patients set goals to reduce their levels of stress and 12 patients worked on stress reduction every day or every week. As indicated by the qualitative data, some patients were already working on lifestyle modification, which the website confirmed and reinforced for them as a good way to prepare for their surgery to optimize their health and recovery.

| Quantitative data | Qualitative data |

|---|---|

|

‘Although I had begun making changes to my diet and physical activity routine several months before surgery, the prehab website confirmed for me that I was on the right track and already taking steps to improve my outcome’ ‘I began changing my habits (exercising more and eating healthier) at least 3 months before surgery, assuming it would benefit my recovery, and I feel that I felt the effects of those changes through increased mobility post-op and a quicker recovery’ |

Feasibility concerns for the PREP structured support

‘I just wish the timeline for the prehab was longer.’

‘Would have been more valuable with more time.’

‘I feel that a 2-week presurgery time-frame was a bit time constraining. I am employed so couldn't put my full attention on this while trying to finish up my work before surgery.’

‘I was provided access to the prehab website 2 or 3 weeks before surgery. I think having earlier access (perhaps a couple of months before surgery) would encourage patients of elective bowel surgeries to adjust more effectively to healthy habits and routines before surgery.’

‘I am employed so couldn't put my full attention on this while trying to finish up my work before surgery.’

‘Covid, with all of it's rules, masks, long surgical wait times, and not easy access to doctors did not allow me to be nearly strong enough for my surgery.’

Potential for improving overall health and well-being

Table 5 shows the results of the EQ5D-5L questionnaires measured at baseline and at 3 months postsurgery. Results showed that, for most domains, patients had worse overall health and well-being at 3-months postsurgery than before surgery. We also found that the presurgery median EQ5D-5L utility score was 0.86 (IQR 0.082) which was slightly higher than the postsurgery median EQ5D-5L utility score [0.81 (IQR 0.083)]. Upon visual display, the lowest outlier values presurgery appeared lower than the lowest outlier values postsurgery.

| Level of problems | Mobility | Self-care | Usual activities | Pain/discomfort | Anxiety/depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |

| 1 (none) | 21 (84%) | 13 (62%) | 22 (88%) | 18 (86%) | 15 (60%) | 4 (19%) | 10 (40%) | 2 (10%) | 12 (48%) | 10 (48%) |

| 2 (slight) | 3 (12%) | 7 (33%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (10%) | 8 (32%) | 13 (62%) | 7 (28%) | 15 (71%) | 10 (40%) | 7 (33%) |

| 3 (moderate) | 1 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (19%) | 7 (28%) | 4 (19%) | 2 (8%) | 2 (10%) |

| 4 (severe) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | 1 (5%) |

| 5 (extreme) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Total | 25 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 21 (100%) |

| Number reporting any problems (levels 2–5) | 4 (16%) | 8 (38%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (14%) | 10 (40%) | 17 (81%) | 15 (60%) | 19 (90%) | 13 (52%) | 11 (52%) |

DISCUSSION

This patient-oriented feasibility study of a novel, web-based structured support strategy for universal colorectal surgery prehabilitation found high demand and very good acceptability among a sample of colorectal patients in Western Canada. The PREP intervention was co-created to primarily provide expert-vetted educational content on multiple components of preparing for colorectal surgery. It also was co-designed to include additional ‘active support’ in the form of either nutritional counselling and/or health coaching if patients requested this; however, this ‘active support’ was underutilized. Both quantitative and qualitative data support the importance of helping all colorectal surgery patients to better prepare for their surgery through a lay-oriented, expert-vetted educational tool that gives structured support for self-management of modifiable lifestyle factors, including reducing psychological stress. However, the practicality of patient self-directed access to more ‘active support’ requires further consideration as no patients contacted the team for this service as indicated on each webpage.

Findings in relation to other work

The high website visitation rates of 71% reported by patients were reflective of findings from previous feasibility studies on telehealth-delivered prehabilitation programmes which found adherence rates of >80% [35] and 71% [31]. The high participation rate of accessing the website may be attributed to the self-directed nature of the website, where patients had the flexibility to access the website on their own schedule with minimal active supervision, concordant with earlier work [23]. Not only the flexible access but also the ease of use of the website may explain the high utilization of PREP by colorectal surgery patients. In fact, three-quarters of patients reported that it was easy to find and access resources to help them prepare for colorectal surgery and that they would recommend this prehabilitation programme. This result was comparable to findings of similar feasibility studies that showed a similar proportion of patients reporting prehabilitation as easy to use (including wearable technology), pleasant and positively rated overall [35, 36].

We were surprised to find that, despite a strong reported interest in using the ‘active support’ component of the PREP programme, no patients contacted the team for health coaching sessions. Past studies have reported 68% utilization rates of similar active support components in a web-based inspiratory muscle training programme [37]. There are likely to be several reasons for our finding that reported interest differed from actual utilization rates of the ‘active support’ component of PREP. One main reason is that the availability and/or mode of access of ‘active support’ from a health coach versus nutritional counselling from a hospital dietitian was not clear to patients enrolled in PREP. This explanation is supported by the additional finding that a handful of patients reported having received ‘active support’ but our team did not receive any specific requests for either health coaching or nutritional counselling. Another possible explanation might be the premise through which the ‘active support’ was offered. In the recent study by Piraux et al. [37], the active support component was a necessary component of the prehabilitation programme, whereas the ‘active support’ offered in this study was an optional component of the prehabilitation programme that required patients to contact the team for more information. Another explanation is that the nature and extent of communication about the ‘active support’ component was insufficient for patient engagement with this aspect of the PREP programme: only a single sentence at the bottom of each webpage referred to the availability of ‘active support’ and referred to both nutritional counselling and health coaching. Finally, other reasons why patients did not actively request the ‘active support’ component of the PREP programme could be that they may have been overwhelmed with the information and diagnostic issues and did not want to engage with a health coach, or they may have had other priorities or resources available to them to help with their lifestyle modification in preparation for surgery.

Lifestyle modification as prehabilitation commonly included either healthy eating or physical activity. Our results showed that most participants worked on physical activity at least once a week, with over half reporting a goal of physical activity at least four times a week. Other feasibility studies found similar, though slightly higher (88%), proportions of patients attending exercise prescription appointments in a surgical prehabilitation programme [38]. Differences in study design and the format of prehabilitation may explain these results, since this study did not involve supervision of physical activity that was designed to be self-selected and self-guided by patients, as was previously emphasized in earlier focus groups [23]. The relatively high self-directed engagement in physical activity in this study suggests that patient-oriented prehabilitation may be not only respectful of patient preferences but also more cost-effective and sustainable for government-funded healthcare systems.

The largest majority of patients reported choosing healthy eating goals to prepare for colorectal surgery at least once a week and often nearly every day. This is a novel finding among existing prehabilitation studies, which typically involve nutrition supplementation as the dietary intervention rather than a focus on improving the overall quality of the diet and healthy eating practices [39, 40]. Notably, the proportion of patients in this study who reported healthy eating goals was comparable to previous research showing complete compliance with nutrition supplement prehabilitation by 72% of patients [39]. Similarly, other work has documented that 83% of patients were compliant with oral nutritional supplements in perioperative surgical care (i.e. 7 days prior to surgery) [40].

Another important and novel finding from this study was that nearly 70% of patients reported stress reduction as one of the goals for this multimodal prehabilitation programme (only six indicated this as ‘not relevant’), and nearly 60% worked on stress reduction at least once a week. Other prehabilitation studies involving psychological support have reported adherence rates of 96% for a supportive attention intervention [41] and 86% for an audio CD intervention [42]. In both Garssen et al. [42] and Parker et al. [41] the psychological interventions were active, supervised intervention, whereas the psychological support component in the current study offered supportive resources without any active supervision. This result echoes the importance of striking a balance between the benefit of active supervision and the benefit of flexibility from self-management and patient choice.

Methodological considerations

This feasibility study had loss to follow-up, although this was minimal. The study sample contained a low prevalence of obese patients and patients who smoked, and the study may be limited by selection bias from a more health-motivated population; however, the sample characteristics reflect the broader population of British Columbia, which has the lowest prevalence of obesity, cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol consumption and the highest prevalence of physical activity across all 10 Canadian provinces [43]. Due to ethics restrictions, no information was collected on socioeconomic status that may have helped with interpreting the malnutrition risk data that were available for a small number of enrolled patients. It is unknown whether the study sample was diverse and included more marginalized patients, thus additional research should over-sample more hard-to-reach subpopulations from remote and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. Most importantly, the duration of the surgical wait-time was very short for some patients (at or close to the 2-week minimum from the decision and consent inclusion criterion) which was a barrier to engaging in prehabilitation (i.e. using the new website and implementing lifestyle modifications). In addition, only patients who understood English were included for practical reasons, which might exclude non-English speakers and limit the external validity of the findings. Future research could employ revised inclusion criteria and a longer recruitment period to allow for patients to have more time to fully engage in prehabilitation and develop new behavioural habits to optimize their health before surgery. However, the length of surgical wait time for patients who enrolled was typically about 2–3 weeks. A randomized pilot study assessing additional objective measures of adherence and programme success is needed prior to a larger randomized controlled trial to collect further information, balanced against adding patient burden in the context of surgical recovery.

A key strength of this study was that it was patient-oriented with several patient partners who co-created the intervention at every stage. This enabled the resulting information and resources provided through the website to be engaging, relevant and accessible for all patient users. In addition, all the content was evidence-based and took a multimodal approach to addressing both the physical and mental/emotional health of patients. Another strength of this study was the very good sample size obtained to allow for robust feasibility testing. Finally, this study had strong leadership support from our clinical knowledge users which enabled the results of this research to be incorporated into clinical practice (https://colorectal.providencehealthcare.org/patient-info/planning-ahead/prep-surgery).

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that a comprehensive web-based intervention combining dietary advice, advice on physical activity, psychological support and smoking cessation support prior to undergoing colorectal resection was feasible for at least three-quarters of study participants, with the majority feeling satisfied with the intervention. However, modifications to the study process should be considered to better facilitate informing patients about the benefits of using a health coach in order to determine the feasibility of the enhanced component of ‘active support’. This study can help inform future trial research to assess the efficacy and effectiveness of delivering patient-centred multimodal prehabilitation in colorectal surgery.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by The University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H20-01358) and all patients gave written informed consent. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Annalijn I. Conklin: Conceptualization; methodology; data curation; investigation; funding acquisition; writing – original draft; visualization; project administration; formal analysis; supervision; software. Nathanael Ip: Writing – original draft. Kexin Zhang: Data curation; investigation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Ahmer Karimuddin: Funding acquisition; conceptualization; resources; writing – review and editing; validation. Carl Brown: Funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; resources; validation. Kristin L. Campbell: Funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; data curation. Joseph Puyat: Data curation; writing – review and editing; funding acquisition. Jason Sutherland: Methodology; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the study participants who gave up their time to participate in the feasibility study. We especially thank the five patient partners of the PAG who dedicated their time and expertise to co-create and co-design the PREP prehab website for this feasibility study. We are also grateful to the Research Coordinators of the St Paul's Hospital colorectal clinic for assistance with recruiting study participants.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This feasibility study was supported by a BC SUPPORT UNIT Pathways to Patient Oriented Research Award.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and appendices. Original data may be obtained from the senior author upon written request.