Food avoidance strategies in eosinophilic oesophagitis

Summary

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a chronic disease associated with significant morbidity that can result in permanent fibrosis and stricture formation. Given the complexity, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended to manage these patients. In the majority of children with EoE not responsive to proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), inflammation is driven by sensitivity to foods and treatment with an elimination diet can be effective. Foods most commonly identified to trigger EoE in children are milk and wheat, but egg, soy, meats and grains can also be triggers. Foods can be eliminated using a step-down or step-up approach. If the goal is to achieve quick remission, elemental diet or six food elimination diets are the most effective. A step-up approach starting from a 1-2 food elimination diet and increasing the number of foods based on a personalized dietary approach is recommended if the goal is to achieve remission using the least number of endoscopies and with increased acceptability to the patient. Children with EoE on elimination diets require frequent monitoring of growth and nutrition, as well as screening for symptoms of EoE, allergy and mindfulness regarding psychosocial impact of chronic disease on the family and child. Current research focused on tools to select patients who mostly will benefit from dietary treatment, identify relevant food allergens, obtain oesophageal tissue non-invasively and induce tolerance will greatly improve the treatment of EoE.

1 INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a world-wide chronic clinical-pathologic disease defined by eosinophil infiltration limited to the oesophageal epithelium.1, 2 Once considered a rare disease, it has now reached a yearly incidence of 1/10 000 with a 50- to 70-fold increases in the last decade3-9 and it is more common in Caucasian, atopic males.10-20 Currently when suspected, oesophagogastroduodenal endoscopy (OGD) is the only reliable tool available for diagnosis and follow-up monitoring of EoE.2

Eosinophilic oesophagitis appears to be a late manifestation of the atopic march, and as per other atopic diseases T helper type 2 (Th2), predominant inflammation driven by chronic antigen exposure from food and possibly environmental allergens has been demonstrated by multiple independent groups.18, 21-28 There is now global evidence that food allergens (eg milk and wheat) are the most common triggers in EoE; however, the pathological process that leads to food allergy driven inflammation in EoE is not completely elucidated. It is believed that genetically driven oesophageal epithelial dysfunction leads to increase contact of food allergens with immune reactive cells with consequent development of a specific Th2 response which initiates a vicious circle of further increase of epithelial permeability and chronic Th2 inflammation.29-31 The complex nature of the immunological response as well as a lack of knowledge on which specific cells are initiating and perpetuating the inflammation in EoE is great obstacles in the development of allergen testing to predict food allergen triggers in EoE. Indeed, classical food allergen testing, such as measurement of specific food IgE by in vivo (ie skin prick test [SPT]) or in vitro testing (ie ImmunoCap, ISAC) and delayed food allergen response by patch testing, has been unable to consistently predict EoE food allergen triggers.27, 28 For similar reasons, so far no peripheral biomarkers have been developed that can be used instead of the OGD for diagnosis and treatment monitoring.32 Therefore, dietary treatments are largely empirical and require many OGDs to establish efficacy.

This review will provide a practical guide to assist clinicians and dieticians in choosing and implementing dietary therapy for patients with EoE.

2 CLINICAL MANIFESTATION OF EOE AND MANAGEMENT OF EOE

Eosinophilic oesophagitis can occur at any age and has heterogeneous clinical presentations depending on age at the time of presentation.33

Children with EoE present with signs of oesophageal dysfunction (Table 1), whereas symptoms of ongoing fibrosis, such as dysphagia and food impaction, are the most common presenting symptoms in teenagers and adults1, 9, 34, 35 (Table 1). The difference in symptoms in various age groups is believed to be due to the Th2 eosinophilic inflammation, that if left untreated progresses to fibrosis. Therefore once the EoE diagnosis is established, it is important to initiate a therapy that controls the local eosinophilic inflammation to prevent fibrosis with its associated complications such as oesophageal stricture and food impaction2, 9

| Children | Adults |

|---|---|

| Feeding difficulties n | Dysphagia |

| Food aversion | Food impaction |

| Decreased appetite | Decreased appetite |

| Heartburn | Heartburn |

| Chest pain | Uncommon |

| Abdominal pain | Uncommon |

| Gagging | Uncommon |

| Nausea | Nausea |

| Regurgitation | Regurgitation |

| Sialorrhea | Sialorrhea |

| Vomiting | Vomiting |

| Slow growth/failure to thrisev/weight loss | Uncommon |

| Cough | Uncommon |

| Dysphagia (older children) | Common |

| Food impaction (adolescence) | Common |

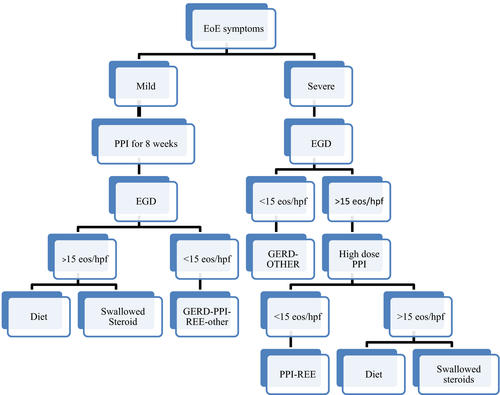

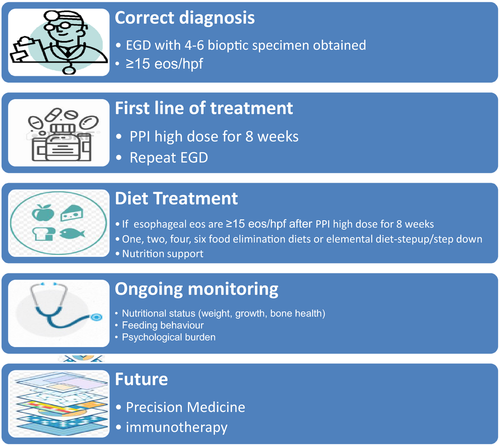

When EoE is suspected based on symptoms, a diagnosis is confirmed if at least 15 eosinophils per high power field (eos/hpf) as a peak value are found in one or more of at least four oesophageal biopsy specimens obtained from the oesophagus via OGD2 (Figure 1). OGD remains for now the only reliable method to assess the disease activity, and it is repeated at least 4-8 weeks after each therapeutic intervention to assess efficacy.2

The accepted treatments of EoE are high-dose proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), diet or steroids32 (Figure 1). When possible, patients should be maintained on monotherapy to avoid risk of lack of compliance due to therapeutic complexity, add unnecessary cost and side-effects.36, 37 If monotherapy fails, a combination therapy with steroids and food avoidance or food avoidance and PPI is acceptable.38 Short courses of oral/systemic steroids or oesophageal dilations have also been used for short-term control of the disease.36, 39

Most clinicians use PPI as first line treatment due to its safety profile, ease of administration36, 39, 40 and only in those cases not responsive to PPI progress to either topical steroids or food antigen avoidance2, 9 (Figure 1). Currently, patients are counselled with the different available “maintenance” therapeutic options for EoE: PPI, topical “swallowed” steroids or diet therapy. Choices are based on patient preferences. There are currently global research efforts to better understand the EoE pathogenesis and develop personalized therapeutic approaches. Tools to help to understand who will better benefit from food elimination diet vs other therapeutic options are highly needed. For example, we have recently demonstrated that being allergic to multiple foods is associated with the most recognized genetic risk for EoE, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) RS3806932 in the promoter region of the TSLP gene on 5q22.41 As we discover more connection between genotype and EoE phenotype, we will have more data to establish a personalized therapeutic approach.

3 FOOD ALLERGENS AS TRIGGERS OF EOE

In patients with EoE foods have been shown to be triggers in both adults and children through the use of elimination diets.9, 42-45 Elemental diets have demonstrated resolution of symptoms and normalization of biopsies in greater than 95% of pediatric and adult patients.9, 46, 47 Globally empiric and test directed diets have shown that most patients are allergic to 1-3 foods. These food allergens have been demonstrated to have a causative role in EoE following Koch's postulate as demostrated by clinical and endoscopical resolution of EoE once the food is removed and reexacerbation when the same food is reintroduced.9, 26, 43, 34 Reactions in each individual are reproducible. Most patients are allergic to milk alone or in combination of other foods.9, 26, 43, 34 The most common foods that have been found to elicit EoE are listed in Table 2. The exact mechanism leading to this food-allergic reaction is unknown, but IgE-mediated reactions seem not to play a major role: measurement of specific IgE to foods does not identify EoE triggers, anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) fails to induce remission, patients who undergo oral immunotherapy or who outgrow spontaneously IgE-mediated food allergy and reintroduce the food in the diet are at risk of developing EoE, and in mice without IgE EoE still develops.48 On the contrary, there is some evidence indicating that food may cause a Th2-specific sensitization. We have recently observed a predominant Th2-driven milk-specific antigen response in Peripheral T cells obtained from paediatric patients with milk-induced EoE.23 These findings suggest that EoE is a Th2-specific disease and raises the possibility that EoE is not limited to the oesophagus, but involves T cell activation also in the periphery.23 It is postulated that the initial Th2 response to food happens in genetically predisposed individuals, whose damaged oesophageal barrier inappropriately secretes various alarmins like thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-25, triggering Th2 cytokine secretion from innate (eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, invariant natural killer T cells [iNKTs]) and adaptive (Th2 cells) immune cells.33 Like in atopic dermatitis, these Th2 cytokines contribute to further damage the epithelial barrier which in turn leads to the establishment of sensitization to food allergens that ultimately then represent the chronic trigger of the disease in the majority of patients.33 Specific IgG4 to food is elevated in patients with EoE but their pathogenetic role is still unclear, as they could be an attempt of the immune system to down-regulate the Th2 inflammation.49 Specific IgG4 level to specific foods has not been shown to be able to predict food allergy in specific patients. IgG4 level to specific food largely overlaps in EoE and control patients.49-51

| Causative foods From six food avoidance diets | Causative foods four food avoidance diets | Causative foods From elemental diets | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | USA | USA | |||

| Adult 43, 68 | Pediatric 34, 59, 115 | Pediatric 70 | Pediatric 42, 75 | ||

|

Wheat (60%) Milk (50%) Soy (10%) Nuts (10%) Egg (5%) |

Milk (44%) Egg (44%) Wheat (22%) Shellfish (11%) Nuts (11%) |

Milk (65%) Egg (40%) Wheat (37%) Soy (38%) |

Milk (74%) Wheat (26%) Eggs (17%) Soy (10%) Peanut (6%) |

Milk (85%) Egg (35%) Wheat (33%) Soy (19%) |

Cow milk (70%) Soy protein (40%) Wheat (20%) Peanut (20%) Egg (10%) Beef (10%) Chicken (9%) |

| Spain 37 —adult | Spain 53 —adult | Spain 60 —pediatric | |||

|

Milk (62%) Wheat (29%) Egg (26%) Legumes (24%) Fish/Seafood (19%) Nuts (17%) |

Milk (64%) Wheat (28%) Egg (21%) Legumes (7%) |

Milk (50%) Egg (36%) Wheat (31%) Legumes (18%) |

Legumes (n = 1) | ||

| Australia 69 —adult | Netherlands 116 —adult | ||||

|

Wheat/gluten (43%) Milk (39%) Egg (35%) |

Milk: n = 3 (17.6%) based on histology; n = 2 (11.8%)based on symptoms Successive introduction of egg, nuts and/or seeds and wheat n = 3 (17.6%) based on endoscopy Unable to identify food n = 3 (17.6%) |

||||

4 DIET

Therapeutic diets in EoE are interventions aimed at inducing disease remission.

Most physicians will now start dietary intervention after showing that PPIs fail to induce remission; however, it can be used as first line therapy without trying PPI therapy first based on most recent international guidelines.32 After a PPI fails to induce remission and an elimination diet is initiated, there are no guidelines to aid the decision about continuing the PPI or pursuing diet alone.32

It is now clear that the more foods initially eliminated the more likely it is to achieve remission at the first endoscopy,52 with elemental diet being the most effective dietary treatment in EoE, even if most patients are allergic only to 1-3 foods.27, 37, 34, 53

Diet therapy compared to swallowed topical steroid and PPI has the advantage to achieve remission of EoE with similar effectiveness without using drugs with their real or perceived side-effects such as impact on final height or bone health.54 Especially in paediatrics, where steroids are typically more feared, refused, and difficult to use, diet is an attractive therapeutic option. Even more interesting is the fact that the few children who have been reported to truly outgrow the disease were all treated with diet.9

Dietary eliminations however are not risk free. Nutritional deficiency, decreased quality of life, psychological impact, risk of developing eating disorders, increased cost and complexity are major drawbacks in diet therapy.55 Patients on therapeutic diets should be followed by a nutritionist to maximize the number of options available in the diet, avoid nutritional imbalances and accidental exposures. Childrens’ growth parameters and feeding behaviours should be closely monitored. Moreover, feasibility, side-effect of the diet and patient preference weigh heavily on the decision on which food initially eliminates from the diet.

After the initial food elimination diet, an OGD is essential to show that the chosen diet has induced disease remission.32 Typically, a 6- to 8-week interval is desirable before repeating the OGD, however in a subset of patients longer may be necessary to induce histological remission after an initial symptomatic and inflammation improvement.52 Once remission is achieved, foods or food groups are sequentially reintroduced to identify the trigger food or foods, in order to maximize efficacy and minimize side-effects stemming from food restrictions. Each change in the diet needs to be followed by an OGD to confirm the outcome of the diet, as symptoms and peripheral biomarker do not correlate with oesophageal inflammation.32

Diet strategies that have shown effectiveness in EoE patients are (a) a strict elemental diet, (b) empiric food elimination based on the most common food antigens and (c) specific antigen avoidance based on allergy testing44, 46, 36, 56.

4.1 Elemental diets

4.1.1 Efficacy of elemental diet

A total elemental diet requires the complete replacement of foods with a nutritionally complete elemental formula, where the protein source is comprised entirely of synthetic amino acids (Table 3). For an elemental diet, all international food allergy and gastro-intestinal guideline groups recommend an amino acid formula for the management of EoE.57

| Contain | Free essential and non-essential amino acids |

| May contain | Corn syrup solids |

| Safflower | |

| Coconut | |

| Soy oils | |

| Medium chain triglycerides (MCT) oil | |

| Vitamins | |

| Minerals | |

| Does not contain | Sucrose |

| Lactose | |

| Milk | |

| Soy | |

| Fibre | |

| Wheat starch |

To date, nine papers have reported on the use of complete elemental diets in patients with EoE: seven papers in children and two papers in adults.

The first ever reported study using elemental diets in children with EoE was a prospective non-randomized study from the USA (n = 10) and showed symptom improvement in 8/10 (80%) of cases.42 Four retrospective reviews,44, 46, 58, 59 case-series from Spain and South Arabia60, 61and two non-randomized adult trials from the United States62 and Netherlands,63 were published with a response rate mostly greater than 90% (71%-97%).

A recent meta-analysis has shown that the overall efficacy of elemental diet in inducing histological remission of EoE defined as a reduction in peak eosinophil counts to <15 per hpf was 90.8% (95% CI, 84.7-95.5%).28

4.1.2 Limitations of elemental diet

Even if an elemental diet is effective, taste, craving for foods, social limitation, cost and poor quality of life significantly limit adherence to diet.44, 62, 63 With the exclusion of infants, in whom a liquid diet is age appropriate, elemental diets are really only practical for short periods and in few selected cases.

Elemental diets were used in the late nineties widely in patients with EoE, before swallowed steroids were used.9 Nowadays, elemental diets can still be used in infants with limited solid foods in their diet, as a way to induce quick EoE remission and do a controlled food introduction to discover food triggers. However the use of elemental diet in every other age group should be limited to those very rare patients in whom remission has not been achieved with dietary restriction, swallowed steroids and PPI or a combination of the above treatments. Indeed, most patients that require elemental formulas for prolonged period of times typically need tube feeding (eg gastric or nasogastric) and such intervention should be highly discouraged, especially in patients with feeding disorders. Therefore when EoE patient has passed the infancy stage, elemental diet should be used only as a last resort treatment when all other treatment alone or combined have failed. Indeed beyond infancy, elemental diets have the worse therapeutic index than all the other available treatment options

In children with feeding disorders and EoE, in those in whom diet leads to severe calories and protein restrictions, elemental formulas can be used as supplements boost protein/nitrogen intakes and energy intake which is particularly important in toddler years and during pubertal growth spurt.

4.1.3 Practical aspects of elemental diets

The taste of elemental formulas can limit patient acceptability. Flavoured and unflavoured formulas are available, and different strategies can be employed to enhance palatability. Manufacturers of elemental formulas can provide additional flavouring techniques and recipes designed to enhance palatability and adherence to the prescribed diet.

Sugar-based candies, Gatorade and artificially flavoured waters may be permitted for some patients.

Another option to increase acceptance of a low antigen diet is to use elemental formula to provide most of the nutritional needs, allowing a limited amount of solid food (usually lower-risk, such as fruits and vegetables and/or certain grains). Such strategies may help to patients to consume the required volume of elemental formula and in that way to avoid enteral tube feedings, while still keeping low antigen exposure.

Moreover, most elemental formulas do not contain dietary fibre. Fibre supplements may be helpful for those children who develop or are prone to constipation. As in the case of multivitamins and minerals, supplements should be free of known allergens. Guar-gum, psyllium and inulin-based supplements can be used by most patients.

The cost of elemental formulas may present a very real barrier to their use as primary—or even adjunct—therapy. Insurance coverage is possible, but can vary significantly depending on where the family lives and their insurance plan or healthcare system of the country of residence.

4.2 Elimination diets

Elimination diets are defined as therapeutic interventions in which one or more foods are restricted. The most common foods that cause Eoe are milk and wheat, followed by soy and egg as listed in Table 2. In EoE, we still talk about food and not single food antigens, as the specific food antigens responsible for EoE inflammation have not been identified. For example, it is under debate if wheat-free diet means wheat free or need to be gluten free.64 At present, advice is also to avoid foods in both their fresh and baked forms. Various empirical and test directed strategies have been studied to establish standardized ways to perform an elimination diet. The efficacy of a dietary change is determined entirely by assessment of histologic remission on oesophageal biopsy and control of EoE symptoms. Symptoms alone have been shown to be not reliable in assessing inflammation activity.65, 66 Various types of elimination have been used and described, with similar efficacy in both adults and children. In general, more foods are eliminated more likely is to have remission at first OGD, but most individuals are allergic really to only 1-3 foods.34 The different dietary options are typically presented to the patients.

Step-down (start from a more restrictive diet and reintroduce progressively all the eliminated foods) and step-up (eliminate 1-2 foods and if not effective progressively eliminate more foods) approaches are both acceptable. Consideration on specific patient characteristics when deciding to use either of those approaches are the following: severity of the disease, nutritional status, eating habits, ability to cook, economical resources, necessity to eat out of the house and reliance of pre-prepared foods. In an adult patient with significant disease (significant trouble swallowing, frequent vomiting etc.), with a normal to high BMI, a baseline diet rich in fruit and vegetable, time and resources to prepare own food a more restrictive diet may be easy to implement and will have higher chance to induce remission at first OGD. However, a step-up approach may be preferable in an individual with mild-moderate symptoms of long duration, who has a limited non-various diet rich in milk and wheat, has low acceptance for new foods, or relies on pre-prepared food and restaurant eating for most meals.

Various types of diets have been described in the literature in prospective and retrospective studies.

4.2.1 Six-food elimination diet

Six food elimination diets (SFEDs) typically exclude milk, egg, wheat, soy, all nuts (including peanuts) and all seafood.43 However, one Spanish trial excluded various cereals (wheat, rice, corn), milk, eggs, fish/seafood, all legumes/peanuts and soy37 and the other Spanish study excluded cow's milk, egg, wheat, all legumes including peanuts, nuts, fish and shellfish.67

Seven SFED studies are reported in the literature, five adult and two paediatric. The five adults studies include data from the USA,43, 68 Spain37, 67 and Australia,69 of which four of the five studies are prospective non-randomized trials(n = 17, 50, 56, 67)37, 43, 67, 69 and one a retrospective review(n = 9).68 In the Australian69 study, all the study participants received a PPI during the intervention. These trials showed a response rate of 52%-74%. The two retrospective paediatric studies (n = 26, 39) were both from the USA.44, 59 Kagalwalla et al44 used a criteria of ≤10 eos/hpf and showed that 26/35 (74%) children improved during a 6-week intervention. Using a criteria of <15 eos/hpf, Henderson et al59 reported that 21/26 (81%) achieved remission, but the duration of the intervention was not specified.

Overall, the SFED appears to have an efficacy between 52% and 80% with most studies reporting 70%-75% success rate.27

4.2.2 Four-food elimination diets

A four-food elimination diet typically involves exclusion of milk, egg, wheat, and soy and foods containing these allergens that globally have been recognized to be the most common triggers of EoE (Table 2).34, 43, 59

However, in the Spanish study,53 the following foods were excluded: mammalian milk, wheat/gluten-containing grains, eggs and soy/legumes including peanuts. Two prospective non-randomized trials of four food exclusion diets have been conducted, one in adults in Spain (n = 52)53 and another multi-centre trial in children (n = 78) from the USA.70 In adults, 54% (28/52) achieved remission defined as a 50% decrease in symptom score and histologic <15 eos/hpf after a 6-week intervention. In the US study, 64% (50/78) of children achieved remission defined as <15 eos/hpf after an 8-week intervention.

4.2.3 One food elimination diets

Two-, one-food exclusion diet studies (n = 17) (avoiding cow's milk and milk-containing products) have been published, both from the USA.58, 71 One study was a retrospective review indicating that 11/17 (65%) (≤15 eos/hpf) children achieved remission; time of intervention not specified.58, 71 The other prospective trial showed that 19/34 (64%) (n = 20), showed 9/14 (64%) achieved less than (≤15 eos/hpf) after 6-8 weeks of milk exclusion.71 Molina Infante72 and Spergel et al34 in prospective and retrospective studies, respectively, showed milk as the sole allergen in about 30% of children.

4.2.4 Two-, four-, six-food elimination diet—the step-up approach

More recently, Molina-Infante72 published a study including both adults (n = 105) and children (N = 25). This study recruited across 14 centres in Spain. Patients underwent a two-food elimination diet (milk and gluten-containing cereals) for 6 weeks, and 56/130 patients (43%) achieved remission based on criteria of symptom improvement and <15 eos/hpf. Twenty per cent of the non-responder achieved remission after a four-food exclusion diet (milk and gluten-containing cereals, egg and legumes). Thirty per cent of those who did not respond to the four food elimination diet achieved remission on a six-food exclusion diet (milk and gluten-containing cereals, egg and legumes, nuts and fish/seafood). Overall cumulative per-protocol clinicohistologic remission rates after TFGEDs (two food elimination), FFGEDs (four food elimination) and SFGEDs (six food elimination) were 43%, 60% and 79%. Foods most commonly triggering EoE were milk (81%), gluten-containing cereals (43%), egg (15%) and legumes (9%). Of those (n = 60) who reintroduced foods post the four and six food exclusion diet, 91% of cases had more than one trigger. Indeed, 92% of those who had 1-2 food triggers were identified with two and four foods elimination diets.

The authors concluded that using this approach of stepping up from a two-, four-, six-food exclusion diet has numerous benefits in terms of reduced need for endoscopies, quicker time to diagnosis, being able to identify almost all patients who had 1-2 food allergies and less dietary restrictions.

4.2.5 Test directed diets

Many studies have looked at the value of SPT and atopy patch tests (APT) in adults and children to find culprits foods in EoE. In adults, positive SPT to food allergens are rare and almost never predict food allergy.43, 73 An adult study from the Netherlands used the ISAC chip test, specific IgE tests and SPTs, to design diets in adult patients.74 Only one participant who happened to be sensitized to milk improved on a cow's milk-free diet (≤10 eos/hpf). This could be a chance finding as milk is one of the most common triggers of EoE.

In paediatric patients, more comprehensive studies have been reported.9, 75 Approximately two-thirds of children with EoE have positive skin tests to at least one food allergen, but their positive predictive value (PPV) is poor especially for key foods such as milk and wheat.9, 76 To increase PPV of skin testing in predicting the food that triggers EoE, APTs have been used.9, 76 APTs are typically used for the diagnosis of non-IgE, cell-mediated immune responses driven by T cells, such as contact dermatitis.77-79 In a study of 361 children with EoE who had eliminated foods based on SPT and APT, the authors found that 77% of the patients had resolution of their biopsy specimens.43

The role of allergy tests either skin or patch test to identify foods triggering EoE is highly debated at present. Arias et al28 summarized 15 studies in their systematic review, of which only two studies in adults, both showing a low response rate of 26.6%80 and 35%,68 which is lower than the accuracy in children. They concluded that these tests have a 45.5% efficacy in indicating which foods are triggering EoE. It is however difficult and complex to compare these studies due to different methodologies used.

Given the aforementioned limitation, the recent guidelines do not recommend the use of SPT, sIgE or APT for the initiation of elimination diet in EoE.32

4.2.6 Other elimination diets

Spergel et al34 compared in a retrospective study different type of elimination diets in a paediatric population with a definite diagnosis of food-induced EoE. The authors found that the SFED had a response rate of 53%, whereas those who eliminated three most common trigger foods (milk, egg and wheat) or milk alone had a respectively a 47% and 30% response rate. The most effective diet in such paper was instead the removal of the most common food groups (milk, egg, soy, wheat) and meats [chicken, turkey, beef and pork]), for a total of eight foods with a response rate at 77%. On the other hand, a vegan diet (no milk, egg, fish, shellfish, or meats; five food groups) had a similar response rate to removal of milk, egg and wheat at 48%.

5 NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS OF ELIMINATION DIETARY THERAPY

Each of the proposed methods for dietary treatment of EoE presents potential psychological, nutritional risks and can adversely affect growth in children.2-5, 81, 82 Once a food is removed, it is also essential to ensure that there is no accidental exposure. Therefore, a thorough nutrition assessment with a registered dietitian (RD) experienced in food allergy is advised for all patients undergoing dietary therapy to avoid nutritional deficit and educate patients on food ingredients and appropriate substitutions.36 (Tables 3-6)

| Food | Nutrients | Substitutions |

|---|---|---|

| Milk | Protein, calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, vitamin B12. | Meats, legumes, whole grains, nuts, fortified foods and enriched beverages (dairy, soy, tree nut-free), fortified orange juice |

| Wheat | Iron, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, folate, fibre | Fortified foods, fruits,vegetables, other fortified grains (barley, oat, corn, rice, rye). Alternative grains such as buckwheat, quinoa, millet, teff, amaranth |

| Egg | Protein, choline, vitamin A, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, biotin, selenium. | Meats, legumes, whole grains (gluten-free) or enriched gluten-free grains |

| Soy | Protein, thiamin, riboflavin, B6 folate, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, iron, zinc. | Meats, other legumes, enriched beverages (as above) |

| Peanuts/tree nuts | Protein, selenium, zinc, manganese, magnesium, niacin, phosphorus, vitamin E, B6, alpha linolenic acid, and linoleic acid | Meats, seeds, seed butters, legumes, vegetable oils |

| Fish/shellfish |

Protein, iodine, zinc, phosphorus, selenium, niacin Fatty fish: vitamin A, vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids |

Meats, legumes, seeds, vegetable oils (canola/flax), enriched beverages as above |

| Assessment | Data to collect |

|---|---|

| Accurate anthropometric data | Weight |

| Height | |

| BMI | |

| Detailed diet and symptom history | Temporal Correlations between symptoms and diet |

| Evaluation of dietary adequacy list | Typical breakfast |

| Typical lunch | |

| Typical snack | |

| 3 d food diary | |

| Identification of feeding difficulties/problematic feeding behaviours | Description of a typical meal |

| Food preferences | |

| Texture preference | |

| Food variety | |

| Meal structure | |

| Assessment of comorbidity list | Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease |

| Asthma | |

| Allergic rhinitis | |

| Behavioural issues | |

| Neurological issues | |

| Autism spectrum disorder | |

| Biochemical data | Vitamin D |

| Calcium | |

| CBC | |

| Ferritin | |

| Zinc | |

| Folate | |

| Vitamin B12, | |

| Phosphate | |

| Liver function tests (including alkaline phosphatase to monitor for occult rickets in young children). | |

| Albumin (if severe malnutrition is suspected) |

| Targets | All caregivers (parents, babysitters, grandparents etc.) |

| Patients (if mature enough) | |

| Modalities | Focus on what children can eat (vs what they cannot). |

| Give appropriate resources for additional information | |

| Written Resources | Allergen-free sample menus |

| Lists of allergen-free foods | |

| Food allergy cookbooks | |

| Online resources Food Allergy Research and | |

| Online resources | Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) |

| The American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (www.apfed.org) | |

| Other | Acknowledge impact on family life |

| Referrals for psychological counselling if patients experience ongoing sadness or anger regarding their treatment plan |

It is critical that the pre-diagnosis diet is reviewed, ideally by a dietitian, and assessed in detail (Table 5). Knowing which foods are in the diet at baseline will determine the degree of exposure to higher-risk foods and the potential impact—both nutritionally and on quality of life—that may occur with elimination of these foods.82-84 The risk of dietary inadequacy will increase with the number and types of foods removed from the diet, the degree to which the restricted foods were previously consumed, as well as the child's nutritional status upon diagnosis and presence of additional risk factors (feeding difficulties/texture aversion, IgE-mediated food allergies).82-84 Additional calories, protein and/or micronutrients may be required in children with a history of poor weight gain and comorbidity such as severe atopic dermatitis which increase nutritional requirements.82-84

Careful attention should be paid to the calories, protein and micronutrients remaining in the diet. Micronutrient supplementation, free from all the excluded allergens, should occur as needed if requirements cannot be met with diet alone. Product ingredients should be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure safety and compliance.

Identification of feeding difficulties is a critical component of the nutrition assessment. Many younger children with EoE will exhibit gagging/vomiting, dysphagia, food aversion and altered eating behaviours (limited variety, spitting out foods, neophobia, grazing, lack of mealtime structure).85. Behaviours should be reassessed throughout the course of treatment. If improvement is not observed once normal biopsies are achieved, a referral to a feeding specialist is indicated to determine the need for behavioural therapy.82-84

Adolescent girls may be at risk of feeding disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, as it is the case in IgE-mediated food allergy even if this has not been studied specifically in EoE86

Specific food avoidance has significant specific related issues as detailed below:

5.1 Milk avoidance

The milk antigen that causes EoE is not known. In general, following similarities with IgE-mediated food allergies all mammalian milk and partially and extensively hydrolysed formulas should be restricted.37, 82-84 During milk avoidance, all milk sources included baked milk should be avoided especially when the diet and the food triggers need to be established.43, 87 Later, when is known that the patient is allergic to milk, baked milk can be tried in the diet followed by OGD, as some patients maybe able to tolerate it.43, 87 Enriched soy milk can substitute for cow's milk, as it provides protein, calcium, vitamin D and riboflavin.84 As a general principle, caution needs to be exercised when substituting a frequent trigger such as milk with another frequent culprit like soy. Authors have seen some patients switch to soy milk develop EoE from soy unrecognized prior as diet had limited soy (unpublished data). Enriched tree nut based beverages are also available. However, they would not be permitted on an SFED. In this instance, enriched “milks” or “beverages” made from rice, coconut, oat, potato, flax/sunflower and pea may be considered.82-84 A variety of enriched products can also help meet calcium requirements for some patients. Most of these are lower in calories and protein than whole cow's milk, and the remainder of the diet should be carefully reviewed to ensure that nutritional requirements can be met with other foods.82-84 These products are not appropriate for younger children especially under the age of 2 years; severe malnutrition and rickets have been reported in toddlers provided rice beverages as a substitute for cow's milk.88 Table 7 provides information on some currently available dairy alternatives.

| Calories | Protein | Fat | Calcium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow's milk (whole) | 150 | 8 | 8 | 300 |

| Soy milk | 100-130 | 6 | 3-4 | 300-350 |

| Rice milk | 120-130 | 1 | 2.5 | 300 |

| Coconut milk | 45-90 | 1 | 5 | 100-450 |

| Hemp/sunflower/flax milk | 100 | 4 | 6 | 300 |

| Oat milk | 130 | 4 | 2.5 | 100 |

| Potato milk | 70-110 | 0 | 0 | 300 |

| Nut (almond/cashew/hazelnut) milk | 60-90 | 1 | 2.5 | 200-450 |

| Pea milk | 60-150 | 8 | 4.5 | 450 |

5.2 Wheat avoidance

Wheat and enriched wheat products provide iron, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, folate and fibre. Wheat-free grains are not usually enriched with the above vitamins and minerals, and use of refined flours can adversely affect intake of dietary fibre.82-84

Whole-grain wheat substitutes such as amaranth, buckwheat, gluten-free oats, quinoa, teff, millet and brown rice are better sources of dietary fibre and micronutrients than refined wheat-free flours.82-84 Patients should also be encouraged to increase fruits and vegetables as able.

The question of whether to remove wheat or all gluten-containing grains (wheat, rye, barley and standard oats, which does not contain gluten but can be contaminated by gluten if processed in the same facility as gluten-containing grains) has been raised.64 There are currently no studies suggesting improved histologic outcomes with the latter approach. Although it was unclear from past studies if participants were actually eating rye, barley and standard/non-gluten free oats, as for example in the United States most processed food that is wheat free is also gluten free.64

5.3 Egg avoidance

In an egg-free diet, both egg whites and egg yolks must be avoided. Baked egg should be removed as well, especially while the diet is being established. Eggs provide protein, choline, vitamin A, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, biotin and selenium. Most of these can usually be provided by other foods, depending on what remains in the diet after egg is removed.82-84 Eggs are an important ingredient in baked goods, providing leavening and structure. Instructions on how to replace eggs in baking should be provided to the patient, for example, egg can be replaced with apple sauce, mashed banana and flax seeds.82-84 Vegan alternatives (eg VeganEgg) based on algae are also suitable alternatives for baking and making scrambled eggs. Cholesterol-free egg substitutes such as Egg Beaters (ConAgra Foods, Inc., Omaha, NE, USA) contain egg whites and are not appropriate for use.

5.4 Soy avoidance

Soy provides protein, thiamin, riboflavin, pyridoxine, folate, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, iron and zinc. Its removal likely presents minimal nutritional risk unless it has been a significant part of the diet pre-diagnosis (ie milk-allergic infant or child on soy formula, vegetarian family). Refined soy oil and soy lecithin are tolerated by most soy-allergic individuals and are typically not avoided on a soy-elimination diet.84, 89

5.5 Peanut, tree nuts, fish and shellfish

Peanuts and tree nuts can be replaced with seeds (and seed butters). Major nutrients in fish and shellfish can be replaced with meats, along with seeds and vegetables oils high in omega-3 fatty acids.82-84

5.6 Label reading

Label reading will become a crucial skill for patients and all involved in food selection and preparation during an elimination diet. The specific legislation covering both the United States and the European Union is summarized in Table 8. These laws apply to conventional food products, dietary supplements, infant formulas and medical foods. Manufacturers must also list the specific tree nut, fish or crustacean shellfish used as an ingredient. Major food allergens must also be declared in spices, flavourings, colourings or additives, or if used to aid in processing. These regulations apply only to ingredients derived from the allergens listed in Table 8. Individuals who need to avoid ingredients not covered under the regulations must contact the manufacturer to confirm product safety. Ingredients and manufacturing processes can change over time, and labels should be read each time a food is purchased or consumed, even if the food has been used safely in the past.

| United States | European Union | |

|---|---|---|

| Legislation | Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA) | European Food Information to Consumers Regulation No. 1169/2011 (2014) |

| Allergens included | Eight major food allergens: milk, egg, soybean, wheat, peanut, tree nuts (almonds, Brazil nuts, cashews, coconut, hazelnuts, macadamia, pecan nuts, pistachio nuts, pine nut, walnuts), fish, crustacean shellfish | Fourteen major allergens: cereals containing gluten (wheat, rye, barley), crustaceans, egg, fish, peanuts, soy, milk, nuts (almonds, Brazil nuts, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia, pecan nuts, pistachio nuts, walnuts), celery, mustard, sesame, sulphites, lupin, molluscs |

| Other allergens not included | Molluscs (clams, oysters, mussels, scallops, squid, and octopus), rye, barley, mustard, sesame, lupin, legumes, sulphites, celery | Coconut, pine nut, legumes (eg beans, peas, lentils) |

| Items exempt |

|

|

| Format of information |

|

|

An ingredient used in some European products is codex wheat starch, which is rendered gluten free through extensive washing. It still contains other allergenic wheat proteins and therefore needs to be avoided during a wheat elimination diet for EoE. As per EU regulations, wheat will still be emphasized on the ingredients list, and education should be provided to ensure that gluten-free products are also checked to be wheat free.

In both the United States and EU, precautionary allergen labelling (PAL or “may contain” statements) is not a legal requirement and therefore the risk of contamination from allergens from foods bearing these warnings is variable. Accordingly, there is also a risk of cross-contamination on foods without any warnings.90 Individualized advice should be provided to families regarding PAL, particularly in the context of IgE-mediated food allergies. It is not yet known at this time whether trace exposure can trigger EoE but it is prudent at least in the initial stages to minimize all exposure.83

5.7 Nutritional aspects relating to children

Dietary avoidance, particularly long-term avoidance, can lead to nutritional inadequacies.91, 92 Nutritional deficiencies in food-allergic conditions have been well described in food allergy, indicating deficiencies in calories, protein, fat, vitamins (particularly B vitamins) and minerals (particularly calcium and iron).93 A recent study94 indicates that a number of nutrients may be suboptimal in children with food allergies such as protein, carbohydrate, zinc, calcium, iron and vitamin E.

As mentioned, milk is now considered the number one trigger food in EoE. Milk and dairy products are the main sources of calcium and contribute to vitamin D intake in most people's diets. Either milk substitutes with added calcium or a calcium supplement should be suggested in these cases. A recent study from the UK, focusing on children with non–IgE-mediated food allergies,95 concluded that these children are at risk of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency. Similar data were reported in terms of suboptimal intake of Vitamin D and calcium in children with EoE from the USA, reporting that Vitamin D and calcium intake (mean intake of 606 mg/d) was below the daily recommended intake (mean intake of 112 IU/d),82 despite normal serum levels above 30 ng/mL. None of these children were previously assessed by a RD, despite more than a 12 months difference between the mean age of diagnosis (3.4 years) and age of recruitment (4.8 years).

In one study, 10% children with EoE, presented with moderate malnutrition at baseline96 but no further weight loss was reported during the dietary intervention. Two studies from the same US-based centre indicated that previously 21% of children with EoE were diagnosed with failure to thrive,85 and a more recent study indicates that the BMI z score for children with EoE was 0.13 (45th percentile).82

5.8 Nutritional aspects relating to adults

Food allergy data from adult studies indicate insufficient intake of calcium, and that intake of energy, protein, lipid, phosphorus, zinc, vitamin B1, B2, niacin and cholesterol decreased as the number of food allergens increased. Intake of vitamin A, iron and vitamin B6 was also compromised.91, 97 A recent study from the United Kingdom however indicated that this low intake of nutrients may not be particularly related to food allergies, but general suboptimal nutrient intake in adolescents and adults; even taking nutrient supplements did not correct nutrient in (100% of the United Kingdom recommended nutrient intake]) for nutrients such as potassium, selenium and magensium.98

To date, few studies of dietary intervention have focused on nutritional outcomes in adult EoE. One major concern is that dietary restriction can lead to weight loss. Two studies of an elemental diet reported weight loss,45, 46 and one trial of the SFED reported no significant change in weight.24 However, none of these studies report baseline BMI of participants and other dietary intervention studies do not mention BMI or weight loss at all. A recent UK pilot study found that there was a statistically significant reduction in BMI postdietary intervention; however, for no participants were weight loss considered clinically significant and no BMI dropped below the normal range.99

A comparison of nutrient intake between food-allergic adults and non-allergic controls found micronutrient deficiencies in both groups thought to be due to poor food choices, with the food-allergic group faring slightly better.100 Nutritional deficiencies have also been shown to occur during dietary intervention for EoE; however, in this study these were also present at baseline and for all participants improved during the intervention.99 This is thought to be due to dietary counselling as well as decreased intake of convenience foods. Given the restrictive nature of prolonged elimination diets, further investigation into nutritional parameters is warranted.

In adults, lifestyle or social factors may affect adherence to dietary intervention, such as work, socializing and travel. Difficulty with adherence in particular with an elemental diet is reflected by high withdrawal rates in adult studies45, 46 and the overall low proportion of studies that have been completed in adults compared to children.47 Access to an experienced dietitian may also be a limiting factor due to lack of adult specialists in this area.

5.9 Ongoing evaluation

Dietitians should play a role in the assessment of nutritional status by taking a detailed allergy focused diet history, perform and interpret anthropometric measurements, and consider laboratory tests to confirm or rule out suspected nutritional deficiencies (albumin, total protein, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine). Micronutrient assessment of serum vitamin D (25-hydroxy vitamin D), iron (serum ferritin, iron and total iron binding capacity), zinc, vitamin B12, selenium, and folate levels and others may be suggested.83 These assessments should ideally be carried out every 6-12 months and more often when a deficiency was confirmed and is being treated. Adequate nutrition should ideally be provided by food rather than nutritional supplements. However, in some cases where it is difficult to find suitable alternative (allergen-free) foods due to limited access to foods or feeding aversions or food refusal, the use of nutritional supplements and amino acid-based formulas/beverages should be considered.

As we know more about the disease, we have learned that EoE can change over time. Even when a patient is on a stable effective diet period, OGD (once every 1-2 year) is recommended to be sure that the remission continues. Indeed, for example, dietary change may lead to increase consumption of allergenic foods rarely consumed before starting the diet (ie soy, pea proteins) that may become allergenic and induce EoE or patient adherence may reduce. On the other hand, occasionally patients can outgrow their food allergies so every few years reintroduction of the allergenic foods may be tried.101

Nutritional risks should decrease as foods are successfully reintroduced, and dietary variety expands. Periodic re-assessment of the diet via 3-day food record can be helpful in adjusting micronutrient supplementation. Families must be educated appropriately to enhance success with adherence to specific diet plans. Children must be monitored closely to ensure nutritional needs are met and adequate growth occurs.102-104 Quality of life can be negatively affected by elimination diets.105, 106 The impact of nutritional therapy for both the patient and family should be assessed on an ongoing basis. We mostly monitor blood levels only of Vitamin D as the level of other micronutrients has not shown to reflect real nutritional status

Periodic yearly Dexa scan is often used in prepubertal patients, postpubertal women and in all patient at risk of osteoporosis to monitor bone health, especially in patient on milk-free diet and on drugs such as PPI and steroids that can negatively affect bone mass accrual. No guidelines exist on the use of Dexa; therefore, its use is based on clinical judgment and feasibility of the procedure.

Ongoing monitor should also focus on compliance, and lack of compliance is frequent in dietary treatment not associated with acute symptoms.82

5.10 Reintroduction

Once a patient has a normal endoscopy, foods are reintroduced either singly or in groups to try to determine culprit(s). After each food is reintroduced, an OGD must be performed. The decision regarding which food(s) to reintroduce and in which order is often a clinical decision. Starting from either low- or high-risk foods are both acceptable options, and family preference often directs different reintroduction approaches.

In general, for high-risk food (milk, wheat, soy, egg) which are also the most nutritionally important one food at the time reintroduction is recommended followed by OGD after 6-12 weeks. One to three medium-risk (legumes, meats, seafood, peanut/nuts and grains) foods can be reintroduced at one time before repeating OGD depending of previous patient history. Typically, low-risk foods can be reintroduced in groups (fruit and vegetables)

5.11 Comorbidity with IgE-mediated food allergies

Patients with EoE have in 20%-30% of cases IgE-mediated food allergies,31 which add significant complexity in dietary management of EoE.

Nutritional deficit and difficulties in achieving food diversity increase as more foods are restricted. Children with IgE-mediated food allergy that reintroduce a food as they outgrow IgE-mediated food allergy or because they underwent immunotherapy for such food are at risk of developing EoE,48, 107 and children who have serum IgE specific for foods allergens but are able to tolerate the food may develop IgE-mediated food allergies including anaphylaxis after a period of prolonged avoidance108, 109 Therefore, each individual with a possible food allergy (at the present time or in the past) undergoing a diet for EoE should be evaluated by an allergist.

Eosinophilic oesophagitis that develops after previously outgrown IgE-mediated food allergy or oral immunotherapy107, 110 may explain why for high-risk foods like milk and egg the positive predictive value (but not the Negative predictive value) was elevated.75, 76 SPTs therefore may be useful in EoE patients with a possible past history of milk or egg allergy, as positives may point to a previous IgE-mediated food allergy to those foods that may now trigger EoE.

5.12 What if dietary treatment fails?

If a 6-food elimination diet is unsuccessful, one possible approach is to look at the patient's current diet. If there is a large consumption of rich in protein foods such as legumes (including pea protein now a popular cow's milk substitute) or meats, removal of those foods is advisable, before calling the patient non-responsive to dietary intervention.

However, about 20% of Children and adult treated with elimination diet do not respond to dietary therapy, even after step-up approach to remove mostly eaten foods and SFEDs approach is used.43, 46 When this happens is paramount to establish adherence to diet therapy, which is known to be poor in EoE especially when diet is used for long periods of time. In general, compliance is a significant problem when patients feel better in any therapeutic approach, even if there is no data on long-term compliance with diet or steroids. However, delayed in starting therapy leads to increased stenosis with every 10 years of age at diagnosis, the odd ratio increases 2-fold for strictures and 7-fold for dysphagia, suggesting that compliance should be encouraged to avoid long-term consequences.111

Once compliance is established, two options can be offered to patients. One is to start combination therapy with diet and PPI (especially if PPI were not used initially as first line therapy) (Figure 1), and second is to add steroids and slowly reintroduce all the eliminated food to see if steroids alone can maintain disease remission.36, 37

5.13 Future in EoE food allergy

Despite the clear evidence for efficacy of diet in EoE, the pathological process that leads to food allergy in EoE is not completely elucidated. The mechanism of food allergy-induced inflammation is probably complex and that is why in vitro testing for food allergies have been disappointing.

Measurement of IgG4 and T cell in vitro activation with specific food allergens23 is under active investigation to establish accuracy in predicting EoE-specific food allergies.49

IgG4 has been found elevated at the site of inflammation in EoE suggesting that it could be an IgG4-mediated disease.49 However, IgG4 is antibodies produced during a Th2 inflammation and have demonstrated the ability to reduce such inflammation as they are not able to effectively stimulate an immune response when bound to an antigen and they reduce the ability of other antibodies to bind to the antigen.51 Specific IgG4 to food responsible for EoE has been also been detected, but there is a large overlap with levels in healthy individuals, and therefore, they cannot be used clinically.49, 51

T cells from patients with EoE triggered by milk when stimulated with milk either in vitro or in vivo express high level of activation marker CD154 + , suggesting potential use in the future to predict specific food allergy in single individuals, but prospective studies will be needed to establish specificity and sensitivity of the assay for specific food allergens.23

Recently, Warners et al112 injected during OGD six allergens (wheat, milk, soy and three allergens based on the patients’ history) in the oesophagus of eight patients with EoE and three patients without EoE (controls). Five of the eight patients with EoE had evidence for an acute response (luminal obstruction and mucosal blanching); two other patients had a delayed wheal or flare reaction, during an endoscopy obtained 24 hours after the first one. No responses were observed in controls. The authors conclude that oesophageal mucosal food allergen injections induce acute and/or delayed responses in patients with EoE but not controls. No clinical relevance of such positive oesophageal prick test was established in the study112

Finally, minimally invasive and cheaper methods to obtain oesophageal tissue such as the oesophageal string test113 or cytosponge test114 are under active investigation and will make empiric diet more feasible if validated.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Eosinophilic oesophagitis is a chronic, non-fatal disease associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and if left untreated can result in permanent fibrosis and stricture formation. Given the complexity, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended to manage these patients (Figure 2). In the majority of children with non-PPI responsive EoE, inflammation is driven by sensitivity to foods and treatment with an elimination diet can be effective. We recommend evaluating one treatment at the time to assess efficacy. However, combination therapy with diet and PPI or diet and steroid may be advisable if single therapy approaches are not able to control the disease.

Foods most commonly identified to trigger EoE in children are summarized in Table 2. Foods can be eliminated using a step-down or step-up approach. If the goal is to achieve quick remission, elemental diet or SFEDs are the most effective. If the goal is to achieve remission using the least number of endoscopies and with better patient acceptability, a step-up approach starting from a 1-2 food elimination diet and increasing the number of foods based on a personalized dietary approach is advisable. The 1-2-4-6 food approach should also take in consideration the diet and the food which are consumed by the patients. Meats, which are not excluded by an of the standardized diet, can trigger EoE, but nuts, excluded from SFEDs, are rarely recognized as a trigger of EoE especially in the United States.34, 43 Finally, in the last decade an elemental diet is used only in selected cases in which a rapid remission is needed or prior to determining with a step-down approach which foods are causative in EoE.

Multiple OGDs are needed during a dietary treatment to establish efficacy of diet, reintroduce foods and monitor long-term efficacy of diet and food tolerance.

Children with EoE on elimination diets require also frequent monitoring of growth and nutrition, as well as screening for symptoms of EoE, allergy and mindfulness regarding psychosocial impact of chronic disease on the family and child. Current research focused on tools to select patients who mostly will benefit from dietary treatment, predict the specific food allergens, obtain oesophageal tissue non-invasively and induce tolerance will greatly improve the treatment of EoE.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.