Dental caries status and related factors among 12-year-old Somali school children in Hargeisa

Abstract

Objectives

There is little data on the oral health conditions of Somali children. The aim was to assess the dental caries status and related risk factors of 12-aged children in primary schools in Hargeisa, Somaliland.

Methods

A school-based survey was conducted in Hargeisa in December 2022. Using 2-stage cluster sampling, 405 children (12-aged) were randomly selected from 16 primary schools. Data collection involved WHO structured interviewer-administered questionnaire and clinical examinations. The DMFT index was measured according to WHO criteria, and accordingly, the mean for the significant caries index (SiC) was calculated. The association between the DMFT and the relevant variables was analysed using negative binomial regression in STATA.

Results

The overall prevalence of dental caries was found to be 62.7%, with a mean DMFT of 1.7 and a SiC score of 3.7. Non-public school pupils showed significantly higher prevalence of dental caries and mean DMFT compared to public school counterparts (68.5% vs. 58.6%) and (1.91 vs. 1.48), respectively. Merely 14.7% of the participants utilized dental care services in the previous year. The multivariable analysis showed a significant positive association of the DMFT outcome with attending a non-public school (95% CI 1.16–2.12) and having many previous dental visits (95% CI 1.22–2.83). In the adjusted model, fathers of low education had children with better dental caries status (lower mean DMFT) than their well-educated counterparts. The mean DMFT was not significantly influenced by the factors sex, location, educational attainment (school class of the participants) and frequency of teeth cleaning.

Conclusion

Although the overall mean DMFT of school children in Hargeisa could be regarded low, the high levels of untreated caries especially in the one-third most affected are a cause for concern. Children enrolled in non-public schools formed the high-risk group. Preventive oral public health programs targeting Somali school children are recommended.

1 INTRODUCTION

Globally, the combined prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease and tooth loss is higher than the prevalence of any other non-communicable disease. It has remained unchanged at 45% during the last three decades.1 In deprived communities, people are not sufficiently covered by oral health care due to shortages of oral health personnel and resources. The available services are mostly offered from central hospitals situated in urban centres, with little importance given to preventive or restorative dental care.2 A high prevalence of dental caries has been reported by recent studies conducted in some low- and middle-income African countries such as Ethiopia,3, 4 Eritrea,5, 6 Uganda,7 Tanzania,8 Kenya9 and Zimbabwe.10

Somalia, a developing nation situated in the Horn of Africa, was established in 1960 following the union of the former British Somaliland and Italian protectorate. However, post-independence instability escalated into a civil war in 1988, and then the northern region of Somaliland declared independence in 1991. It is noteworthy that international reports and research often group Somalia and Somaliland under the name of “Somalia”.11, 12 In 2021, the life expectancy of Somalis was 55 years, 53 for males and 57 for females.13 The main causes of death in this region were infectious diseases (particularly lower respiratory infections, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases and malaria) in addition to cardiovascular diseases.14 Hypertension and diabetes are the most prevalent chronic disease entities among adults in Somaliland.15

Comprehensive figures for annual health expenditure are unavailable for Somaliland, but the estimated cost of achieving objectives in the health sector included in the national development plan (2017–2021) only accounted for 7.2% of overall national budget,16 which is below the 15 per cent Abuja Declaration target set by African Union countries.17 This plan did not consider any targets related to oral health. Per capita dental expenditure was less than US$1 according to WHO report in 2022.1

There is limited knowledge about the oral health status of Somali individuals, as comprehensive oral health surveys have not been conducted. A general health screening conducted by nursing students in 2017 reported a caries prevalence of 26% in a convenience sample of school children of a wide age range, from 4 to 19 years, in two public primary schools in Hargeisa. The study only reported the overall prevalence across the age range, without considering the substantial variation in dental health between primary and permanent dentition. The questionnaire used in this screening did not collect information related to oral health and the details of the oral clinical examination were lacking.16 Hargeisa, the largest city in Somaliland with a population of about one million, encompasses a range of primary schools, both public and non-public, which may indicate varying levels of socioeconomic status and potentially different access to dental healthcare services.18 The aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess the dental caries status and related risk factors among 12-year-old school children in public and non-public schools in Hargeisa following the WHO standards for oral health surveys.

2 METHODS

In December 2022, this cross-sectional study was conducted in Hargeisa district of Maroodijieh region, the most populated in Somaliland. It contains the highest number of primary schools [162 public, 165 private and 7 non-governmental organization (NGO) schools] in the country. Boys constituted 56.1% of total students (Class 1–8), and 58% of the students in primary schools are enrolled in governmental schools. Students in rural areas represented only around 10% of primary education enrolment.19

2.1 Sample size and design

The sample size of 405 school children was calculated—guided by a 50% prevalence of a DMFT score of ≥1 (based on the results of recent studies in similar settings),20 a clinically relevant minimum effect size of 33% with twice more students in public schools as private schools, a precision of 5%, a power of 0.8, a design effect of 1.2, and an expected 5% non-response rate. The sample size was calculated with the free software G-power (Universität Düsseldorf).21 A low effect size and design effect were assumed based on other studies from Somaliland that showed no significant cluster effect and small differences between various SES (socioeconomic status).22, 23

2.2 Sampling method (two-stage cluster sampling)

2.2.1 Selection of schools

The updated list of primary schools in Hargeisa district received from the Ministry of Education was used as the sampling frame. Out of 334 primary schools, 16 schools were randomly selected without prior stratification. The final sample comprised nine non-public and seven public primary schools, two of the latter were situated in rural areas. Due to the refusal of four of the selected non-public schools to participate in the survey, an additional sampling using the non-public school list was implemented to replace them.

2.2.2 Selection of participants

The birth date records were unavailable in most of the selected schools and there was a significant number of students who started primary school late, particularly in rural areas. The team members visited all school classes up to grade 6 in each selected school in order to compile a comprehensive list of 12-year-old students (873 students in total) who met the criteria, from which participants were randomly selected for the study. (Flow diagram of participants in the supplemental file). The selected students were given a translated consent letter by their class teachers. To improve the response rate, the team members phoned the parents, verifying the date of birth of their child and explaining the purpose of the study, the content of the questionnaire, and the clinical examination procedure. On the following school day, the study team collected the consent letters from the students in their respective classes. The participants were only 12-year-old students (born in 2010) living in Hargeisa district, free from severe acquired or congenital diseases, who brought the informed consent signed or thumb imprinted by parents or guardians.

2.3 Data collection

A combination of self-assessment of oral health using the WHO structured Interviewer-administered questionnaire for children and oral clinical examination was utilized in this study.24 These assessments took place within the school premises. The questionnaire was used to collect information on experience of pain/discomfort related to teeth, frequency of dental visits, reason for dental visit, frequency of tooth cleaning, use of aids for oral hygiene, use of toothpaste containing fluoride, consumption of sugary foods and drinks, and the level of education of parents (questions /response options /analysed codes detailed in the Data S1).24 The questionnaire was initially translated from English to Somali by a Somali dentist and then a different interpreter performed back translation for validation. In the pilot study, the questionnaire was pretested to assess face validity and acceptability of questions. Discussion with all members of the team after pre-testing was made to ensure that the true meanings of questions were not lost during the process.

The questionnaire was filled out by the interviewers based on the participant's responses to the questions and data was entered later into spreadsheets. The oral clinical examination was performed under natural daylight and involved the assessment of the DMFT index and an evaluation of the need for dental intervention.24

Seven local certified dentists were recruited as research assistants. They were divided into two teams, three trained examiners for clinical examination and the rest for interview questionnaire. The principal investigator (certified dentist) supervised the calibration process of the clinical examination team and the clinical examination of the actual survey. To test the accuracy and reliability of the Somali translation of the WHO questionnaire, as well as to minimize any potential variability among interviewers and establish consistency in the clinical examination team, a pilot study was conducted (Measurements and the pilot study detailed in Data S1).

2.4 Data protection and statistical analysis

Service for sensitive data (TSD) offered by the University of Oslo (UiO) was used for storing the collected data. Data entry and analysis were done using STATA version 17. Due to the skewed distribution of the DMFT, Pearson's chi-squared test was used to test the differences in the proportions of each variable among the two school types, and Mann–Whitney U test was used to test difference in the distribution of mean ranks. Significance was set at p < .05. For the SiC Index, participants were sorted according to their DMFT values, and then one-third of the population with the highest caries scores was selected. The mean DMFT for this subgroup was calculated.25

The impact of cluster sampling was initially assessed and found to be non-significantly different from a simple random sample (p = .08). Given the over-dispersed and highly skewed distribution of DMFT, the multivariable analysis was conducted using negative binomial regression to analyse the association between the DMFT and the relevant variables, presenting incidence-rate ratios (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For estimating the direct association between the school type (non-public/public) and DMFT outcome, other relevant variables captured by our survey and informed by previous research were controlled for in the adjusted model (details in Table 3). Noteworthy, the data collected from the pilot study were excluded from the final analysis.

2.5 Ethical consideration

This research project was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) (Reference number: 2022/ 494 598 REK South-East) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). At the same time, the ethical clearance was obtained from the Ministry of Health Development (MOHD) in Somaliland (Reference number: MOHD/VM:3/509/2022) in addition to permissions from the Ministry of Education and school administrations of selected schools. The randomly selected participants were given informed consents translated into the Somali language for signing by their parents in case they accepted their children to participate in the survey. At the end of examination, participants were informed about their oral health status, given instructions on how to maintain good oral hygiene and received toothpastes and dental brushes for that purpose. In addition, parents were contacted in case of urgent or immediate dental intervention required for their children. For the pilot study, prior permission from the school administration and oral consent from participants were obtained.

3 RESULTS

Of the selected 405 students, 395 returned a signed consent form, giving a response rate of 97.5%. (Table 1). In this study, 12-year-olds belonging to the 6th grade constituted only 20.8% of the total sample, indicating that a high proportion of students started school late.

| Variable | Total (N = 395) (%) | Public schools (N = 232) (%) | Non-public (N = 163) (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Urban | 332 (84) | 169 (72.8) | 163 (100) | <.01 * |

| Rural | 63 (16) | 63 (27.2) | _ | |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | 229 (58) | 128 (55.2) | 101 (62) | .18 |

| Girls | 166 (42) | 104 (44.8) | 62 (38) | |

| School grade/class | ||||

| Normal (grade 6th) | 82 (20.8) | 41 (17.7) | 41 (25.1) | .17 |

| Late starters (grade 5th or below) | 292 (73.9) | 177 (76.3) | 115 (70.6) | |

| Not reported | 21 (5.3) | 14 (6) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Father's education | ||||

| No formal schooling | 70 (17.7) | 57 (24.6) | 13 (8) | <.01 * |

| Primary education or below | 60 (15.2) | 43 (18.5) | 17 (10.4) | |

| Secondary education | 46 (11.7) | 20 (8.6) | 26 (16) | |

| University education | 96 (24.3) | 32 (13.8) | 64 (39.3) | |

| No male adult in household | 14 (3.5) | 11 (4.8) | 3 (1.8) | |

| Don't know | 109 (27.6) | 69 (29.7) | 40 (24.5) | |

| Mother's education | ||||

| No formal schooling | 124 (31.4) | 88 (37.9) | 36 (22.1) | <.01 * |

| Primary education or below | 66 (16.7) | 39 (16.8) | 27 (16.6) | |

| Secondary education | 41 (10.4) | 23 (9.9) | 18 (11) | |

| University education | 47 (11.9) | 14 (6) | 33 (20.3) | |

| No female adult in household | 4 (1) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Don't know | 113 (28.6) | 66 (28.5) | 47 (28.8) | |

- * p-value <0.05 (significant).

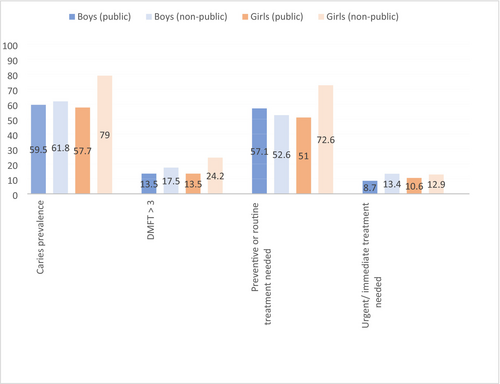

Out of all the participants, only six were absent during the dental clinical examination. The overall prevalence of dental caries was 62.7%, with 60.5% among boys and 65.7% among girls. There was a significant difference in dental caries prevalence between public and non-public schools, mainly driven by a significant difference in caries prevalence among girls in public schools and non-public schools (Table 2; Figure 1). The mean DMFT (SD) was 1.7 (1.8) for the overall sample. Moreover, it was significantly higher in non-public schools than in public ones, with no significant difference observed between boys 1.5 (1.7) and girls 1.8 (1.9).

| Variables | Total (N = 395) (%) | Public schools (N = 232) (%) | Non-public (N = 163) (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral clinical examination ** | ||||

| Caries prevalence | 244 (62.7) | 135 (58.6) | 109 (68.5) | .04* |

| DMFT mean (±SD) | 1.7 (±1.8) | 1.4 (±1.7) | 1.9 (±1.7) | <.01* |

| DT | 244 (61) | 135 (58) | 109 (66) | .06 |

| FT | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.2) | .46 |

| MT | 4 (1) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | .55 |

| DMFT categories | ||||

| DMFT = 0 | 149 (38.3) | 101 (43.9) | 48 (30.2) | .02* |

| DMFT = 1–3 | 177 (45.5) | 98 (42.6%) | 79 (49.7) | |

| More than three | 63 (16.2) | 31 (13.5) | 32 (20.1) | |

| Intervention level required | ||||

| No treatment needed | 101 (26) | 66 (28.7) | 35 (22) | .19 |

| Preventive or routine treatment | 221 (56.8) | 125 (54.3) | 96 (60.4) | |

| Prompt treatment (scaling) | 24 (6.2) | 17 (7.4) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Urgent/immediate treatment | 43 (11) | 22 (9.6) | 21 (13.2) | |

| Teeth cleaning (N = 395) | ||||

| Once or more a day | 356 (90.1) | 208 (89.7) | 148 (90.8) | .32 |

| Once or more a week | 11 (2.8) | 9 (3.9) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Once or more a month | 28 (7.1) | 15 (6.4) | 13 (8) | |

| Cleaning aids *** (N = 395) | ||||

| Toothbrush (yes) | 169 (42.8) | 58 (25) | 111 (68.1) | <.01 * |

| Wooden toothpick (yes) | 114 (28.9) | 83 (35.8) | 31 (19) | <.01 * |

| Dental floss/thread (yes) | 15 (3.8) | 5 (2.2) | 10 (6.1) | .04 * |

| Chewstick/Miswak (yes) | 229 (58) | 149 (64.2) | 80 (49.1) | <.01 * |

| Charcoal (yes) | 45 (11.4) | 36 (15.5) | 9 (5.52) | .01 * |

| Toothpaste (yes) | 232 (58.7) | 116 (50) | 116 (71.2) | <.01 * |

| Dentist's visits (N = 395) | ||||

| Never | 84 (21.3) | 42 (18.1) | 42 (25.8) | <.01 * |

| No visit in the past 12 months | 253 (64) | 170 (73.3) | 83 (50.9) | |

| Once or more in the past 12 months | 58 (14.7) | 20 (8.6) | 38 (23.3) | |

| Reason for the last dental visit | N = 58 (%) | N = 20 (%) | N = 38 (%) | |

| Pain | 48 (82.8) | 18 (90) | 30 (79) | .49 |

| Treatment/follow-up | 8 (13.8) | 1 (5) | 7 (18.4) | |

| Routine check-up | 2 (3.4) | 1 (5) | 1 (2.6) | |

- * p-value <0.05 (significant).

- ** Total sample (n = 389), n = 230 in public and n = 159 in non-public.

- *** Cleaning aids are dichotomized (yes/no).

The percentage of individuals with a mean DMFT greater than 3 was 14.9% for boys and 17.5% for girls. The overall SiC score was (3.7). Notably, the SiC scores of non-public schools (4.04), girls (4.0), and rural areas (4.0) were higher than public schools (3.5), boys (3.6), and urban areas (3.7). 57% of participants showed delayed eruption of permanent teeth. Most of the boys and girls required preventive or routine dental treatment. In addition, 10.7% of boys and 11.4% of girls were in need of urgent or immediate treatment. (Figure 1).

Approximately 31% of the participants reported experiencing toothache or discomfort within the past year. Overall, one-fifth of participants had never visited a dentist (Table 2). Within the previous year, students enrolled in non-public schools had a significantly higher rate of dental visits, nearly three times more than those in public schools.

While toothbrushes and toothpaste were the most commonly used oral hygiene tools among non-public school students, a majority of students in public schools used a chewstick called “Caday Qori” in the local language or the miswak (natural toothbrush made of the twigs of the Salvadora persica tree).26 The use of a chewstick with toothpaste was not uncommon (29.4%) in this setting.

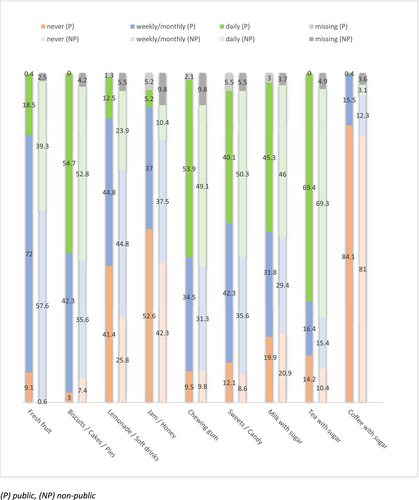

In public schools, only 18.5% of participants reported consuming fresh fruit daily. In contrast, the proportion of daily fresh fruit consumption among students in non-public schools was significantly higher at 39.3% (p < .01). Similarly, they consumed about twice as much soft drinks per day compared to their public-school counterparts (23.9% vs. 12.5%, p < .01). The consumption of biscuits, cakes, chewing gum, sweets, candy, milk and tea with sugar was similar among participants in both types of schools (Figure 2).

3.1 DMFT index and associated factors

The multivariable analysis showed significant associations between the DMFT index and both the type of school and dental visits (Table 3). Following adjusting for all other relevant variables in the adjusted model, an inverse relation was found, showing better dental caries status (lower mean DMFT) with the low level of father's education (primary education or less). Factors such as sex, location, educational attainment (participants' school class), and frequency of teeth cleaning did not have a significant impact on the mean DMFT (Table 3).

| Explanatory variables | DMFT mean (±SD) | Unadjusted IRR (CI) | p value | Adjusted IRR (CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School type | |||||||

| Public | 1.48 (±1.77) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Non-public | 1.91 (±1.79) | 1.34 | (1.06–1.72) | .01 | 1.39 | (1.03–1.88) | .03 |

| Location | |||||||

| Urban | 1.66 (±1.75) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rural | 1.67 (±1.99) | 1.01 | (0.73–1.38) | .97 | 1.35 | (0.93–1.95) | .10 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Boy | 1.56 (±1.71) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Girl | 1.80 (±1.89) | 1.15 | (0.91–1.46) | .23 | 1.21 | (0.95–1.55) | .11 |

| School grade/class | |||||||

| Late starters (grade 5th or below) | 1.66 (±1.80) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Normal (grade 6th) | 1.75 (±1.76) | 1.06 | (0.79–1.40) | .708 | 1.18 | (0.88–1.60) | .25 |

| Father's education | |||||||

| No formal schooling | 1.79 (±2.04) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Primary education or below | 1.27 (±1.75) | 0.71 | (0.46–1.08) | .11 | 0.59 | (0.38–0.91) | .01 |

| Secondary education | 1.57 (±1.68) | 0.87 | (0.56–1.37) | .55 | 0.64 | (0 .41–1.03) | .06 |

| University education | 1.70 (±1.56) | 0.94 | (0.66–1.36) | .76 | 0.79 | (0.52–1.21) | .28 |

| Mother's education | |||||||

| No formal schooling | 1.53 (±1.66) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Primary education or below | 1.78 (±1.94) | 1.12 | (0.82–1.66) | .39 | 1.19 | (0.84–1.70) | .31 |

| Secondary education | 1.56 (±1.73) | 1.02 | (0.67–1.56) | .92 | 0.92 | (0.59–1.43) | .72 |

| University education | 1.66 (±1.70) | 1.08 | (0.73–1.62) | .69 | 1.09 | (0.69–1.71) | .69 |

| Toothbrushing | |||||||

| No | 1.57 (±1.87) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.78 (±1.68) | 1.14 | (0.90–1.44) | .28 | 0.98 | (0.76–1.28) | .93 |

| Teeth cleaning frequency | |||||||

| Monthly or weekly | 1.89 (±2.15) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Daily | 1.63 (±1.75) | 0.86 | (0.59–1.26) | .45 | 0.87 | (0.58–1.31) | .53 |

| Dental visits | |||||||

| Never | 1.21 (±1.43) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Once/more (past 12 months | 2.21 (±1.98) | 1.82 | (1.22–2.72) | <.01 0.04 | 1.99 | (1.32–3) | <.01 |

| No visit (past 12 months) | 1.67 (±1.81) | 1.37 | (1.01–1.89) | 1.52 | (1.08–2.12) | .02 | |

| Fresh fruit | |||||||

| Never | 1.82 (±1.89) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Monthly or weekly | 1.51 (±1.72) | 0.83 | (0.50–1.37) | .46 | .91 | (0.53–1.55) | .74 |

| Daily | 1.95 (±1.90) | 1.07 | (0.63–1.81) | .79 | 1.11 | (0.62–1.97) | .72 |

| Soft drinks | |||||||

| Never | 1.63 (±1.90) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Monthly or weekly | 1.64 (1.68) | 1.01 | (0.77–1.31) | .96 | 1.01 | (0.75–1.33) | .97 |

| Daily | 1.67 (±1.79) | 1.02 | (0.72–2.65) | .89 | 0.94 | (0.65–1.36) | .76 |

| Biscuits, cakes | |||||||

| Never | 1.94 (±1.92) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Monthly or weekly | 1.55 (±1.77) | 0.80 | (0.46–1.39) | .423 | 0.96 | (0.54–1.72) | .91 |

| Daily | 1.71 (±1.80) | 0.88 | (0.51–1.52 | .643 | 1.12 | (0.63–1.99) | .68 |

| Sweets/candy | |||||||

| Never | 1.61 (±1.99) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Monthly or weekly | 1.65 (±1.69) | 1.02 | (0.68–1.54) | .912 | 1.02 | (0.64–1.54) | .92 |

| Daily | 1.72 (±1.83) | 1.07 | (0.71–1.59) | .753 | 1.01 | (0.66–1.52) | .98 |

- Note: Unadjusted: bivariate analysis. Adjusted: following adjusting for location, sex, school grade, parents' education, toothbrushing, teeth cleaning frequency, dental visits, fresh fruit, sugar consumption including soft drinks, biscuits/cakes, and sweets/candy. Significant values are given in bold.

4 DISCUSSION

This study showed that dental decay is a health concern among a subgroup of elementary school students in Hargeisa. The overall DMFT index recorded a value of 1.7, indicating a relatively low level of dental decay severity.27 The vast majority of participants reported a daily cleaning of their teeth using various cleansing aids. However, the global target SiC score of less than three was not attained across various sexes, locations or types of schools. Moreover, more than half of the participants needed preventive or routine dental treatments, while 11% required urgent or immediate interventions.

The study findings provide important baseline data on the status of dental caries and its associated factors among Somali children in primary schools in Hargeisa. This study employed probability sampling to ensure maximum representativeness of 12-year-old children attending both public and non-public primary schools in Hargeisa. The high response rate at individual level gives strength to the external validity of the study. Furthermore, the utilization of standardized data collection tools, such as the WHO questionnaire and oral clinical examinations conducted by trained dental professionals, enhanced the validity of the findings of this school-based survey. The WHO questionnaire included close-ended questions on many relevant variables and themes and provided several response options to improve the accuracy of responses.

However, it is important to approach these findings with caution when applying them to all children in Hargeisa, as the gross attendance ratio (GAR) for primary schooling in the Maroodijieh region in 2020, was found to be 50.4%.28 This highlights the need for additional efforts to survey children who do not attend school in order to compare their dental health status with that of children who are currently enrolled. The study design, being cross-sectional in nature, provided a static representation of the regional prevalence of dental caries without capturing its progression over time. Furthermore, it only offered a snapshot of the risk factors associated with the outcome, as the exposure and outcome were measured simultaneously,29 making it unattainable to establish causal relationships. Additionally, we never will know for sure whether the non-public schools that denied participation represented a different subgroup than the participating ones.

The potential for recall bias could exist, particularly on variables such as the frequency of teeth cleaning, consumption of sugary food, dental pain experience and dental visits. Social desirability bias could happen if the children tended to provide socially desirable answers. For the level of parental education, a considerable number of children (around 27.5%) responded with “don't know,” blurring the possible effect of parental education on the average DMFT in this context. The bivariate and multivariable analysis did not show significant associations between toothbrushing or frequency of cleaning and DMFT outcome. In order to thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of toothbrushing, additional information such as the age of initiation, brushing technique, and parental supervision should have been gathered during the interviews,30 which can be considered a limitation of the questionnaire used in this study. Although the questionnaire was pilot tested with the target group, a validity test of the translated questionnaire was not conducted. The lack of data on parental income and fluoride situation (e.g. water fluoridation) is another limitation.

Dental decay is common among more than half of the primary school children aged 12 in Hargeisa, which aligns with recent studies conducted on 12-year-olds in Eritrea,6 Uganda7 and Zimbabwe.10 In contrast, Nurelhuda et al. conducted a study on the prevalence of dental caries among school children aged 12 in seven major localities of Khartoum state, which had a population of over four million in 2009. They employed stratified random cluster sampling and reported a lower prevalence of caries (30.5%), as well as lower DMFT index (0.42) and SiC score (1.4),31 consistent with findings from Nigeria (Lagos, 2004)32 and Tanzania (2007).8 This variation from the recent studies can be partly attributed to the increased adoption of the Western pattern diet and high-sugar food consumption among school children over the past decades,33 alongside differences in sample sizes and sampling strategies used to recruit participants.

In this study, there was a significant association between the mean DMFT and school type. Non-public schools had a higher prevalence of dental caries and mean DMFT compared to public schools. No significant difference was observed between sexes, which is consistent with findings from a similar school-based survey conducted in Sudan.31 However, it was noted that girls had higher scores in both measures, which could be attributed to their earlier tooth eruption compared to boys,30, 34-36 resulting in a longer exposure to factors that contribute to dental caries.

The frequency of consuming soft drinks and fresh fruit was significantly higher in non-public schools. This observation may shed light on the potential impact of socioeconomic status on sugar consumption and consequently oral health outcomes. For instance, this study found that fathers of low education had children with lower DMFT than their well-educated counterparts in the adjusted model. In the Middle East and North Africa region, there is evidence from 20 studies suggesting that parents' education level could be a potential risk factor associated with dental caries. These studies consistently reported negative associations between parents' education and the dental health outcomes.30

Only 14.7% of the participants utilized dental care services in the previous year, without a significant difference between boys and girls. This finding aligns with the results from a recent study conducted in Northern Ethiopia, which reported a dental service utilization rate of 10.6% among school children.37 Our study findings showed that the main reason for seeking dental care in the past year was pain, indicating the lack of the culture or affordability of seeking dental visits for preventive purposes. The majority of the DMFT index (98.2%) was attributed to the “DT” component, with only 1% of participants having missing permanent teeth due to caries, and 0.8% receiving dental fillings. This suggests that the services provided during dental visits were primarily focused on pain relief, such as prescribing medication, rather than comprehensive restorative or preventive interventions.

Data regarding the average dentist-to-population ratio in Somalia are unavailable.38 Interaction with the community during our data collection indicates that apart from private dental clinics, oral health services available to school children in Hargeisa primarily rely on major public hospitals. However, these hospitals mainly offer dental extractions, while restorative and preventive dental procedures are infrequently performed. All services are provided on a fee-for-service basis, without any special advantages for children in terms of dental treatment. In the event of dental emergencies, children in rural and nomadic areas have the option to seek dental treatment in the city or turn to traditional healers. Furthermore, some private insurance companies offer dental treatment coverage at a high cost.

It is crucial to fully integrate essential oral health care within primary health care (PHC) systems in order to effectively prevent dental caries and ensure the sustainability of public dental services.39 School-based oral health care programs including regular screenings aimed at identifying children in need of urgent dental intervention in both rural and urban areas can be implemented by fostering collaborations among dental care providers, dental schools, and community health workers.40 There is a need for conducting both surveys and longitudinal studies across Somalia and Somaliland targeting different age groups for mapping oral health status and properly identifying the likely risk factors and causes of dental caries and other oral diseases.

5 CONCLUSION

The overall DMFT index for primary school children aged 12 in Hargeisa recorded a value of 1.7, indicating a relatively low level of dental decay severity. Non-public schools had significantly higher prevalence of dental caries and mean DMFT compared to public schools. The mean DMFT was not significantly influenced by factors such as sex, location, educational attainment (participants' school class) and frequency of teeth cleaning. Only a small percentage of participants with dental problems sought dental care services within the past year, indicating unmet dental treatment needs. The findings of this study can provide a baseline for monitoring dental caries status and its risk factors among school children and valuable guidance for government departments and non-governmental organizations to implement dental public health initiatives at individual and community levels.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AED designed the study and carried out the data collection, data analysis and writing of the article. EKH, MAH and AAM supervised the project including the study design, the data collection, data analysis and writing of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Dr. Saeed Mohamood and Dr. Liban Osman from the Ministry of Health for providing the ethical clearance as well as the staff of the Ministry of Education, school administrations, and school children and their parents for cooperation. A special appreciation to the local research assistants and dental professionals: Farhan Ahmed, Abdiwahab Mahdi, Mustafe Osman, Hamse Hamud, Zeinab Muhammad, Omar Mohamed and Hamse Ali for their great efforts in data collection including conducting interviews and the clinical examinations. We are indebted to the biostatistician Ibrahimu Mdala for his assistance in the statistical analysis.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was funded by the Department of Community Medicine and Global Health Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.