Inotuzumab ozogamicin compassionate use for French paediatric patients with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Paediatric patients with refractory or relapsed (r/r) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (BALL) are facing therapeutic challenges, considering their poor five year disease-free survival.1, 2 Immunotherapy could improve their survival and reduce adverse events.

The antibody drug conjugate, inotuzumab ozogamicin (InO), is a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 expressed at the surface of > 90% of paediatric B-ALL patients, linked to calicheamycin.3, 4 An adult INO-VATE (INotuzumab Ozogamicin trial to inVestigAte Tolerability and Efficacy) trial compared InO with standard chemotherapy in first or second salvage treatment for B-ALL and showed an increased complete remission (CR) rate (80·7% vs. 29·4%, P < 0·0001) and Minimal Residual Disease negativity among CR patients (MRD, 78·4% vs. 28·1%, P < 0·0001).4

In this French multicentre paediatric retrospective study, we assessed the efficacy and toxicity of InO obtained through a compassionate use program, in r/r B-ALL.

Patients ≤ 18 years old were reviewed for demographic data, treatment history, InO's efficacy, and toxicity. CR was defined by < 5% of residual blasts in bone marrow and CRi by incomplete haematologic recovery (platelet < 100 G/l or neutrophils < 1 G/l). MRD, performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for immunoglobulin rearrangements, was considered negative at a threshold of 10−5. Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were defined according to international standards. Toxicities were evaluated using the CTCAE 4.03, focusing on haematologic and hepatic toxicities. European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) paediatric criteria were used for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) diagnosis and severity grading.5

For a subset of patients, B- and T-cell subpopulations post-InO were studied by immunofluorescence (immunostaining, lyse/no-wash and fluorescent beads addition, and analysed on a Navios cytometer, Beckman Coulter).

Twelve patients, aged from 3·7 to 18·2 years old (median 14·5 years), received at least one dose of InO between November 2015 and June 2017 in six haematologic French centres (Table SI). Patients had been heavily pre-treated: 5/12 with haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and 8/12 with immunotherapy, bi-specific antibody blinatumomab (n = 6) or CD19-CART-cells (n = 2). They were either refractory to their last regimen (6/12) or in first to fourth relapse. No patient had received anti-CD22 therapy before InO. Surface CD22 expression was > 90% for all patients at baseline.

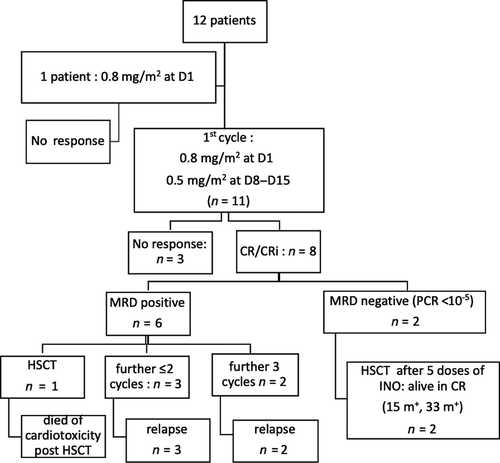

Patients received 1–9 doses of InO (median 5). All centres used adult phase III dosage: 0·8 mg/m2 at day 1 and 0·5 mg/m2 at days 8 and 15, reduced to 0·5 mg/m2 per week if CRi was achieved. Four patients were refractory to treatment. CR/CRi were observed in 8/12 patients, and two achieved MRD negativity after their first cycle of InO and are still in remission with ≥15 months of follow-up (Fig 1).

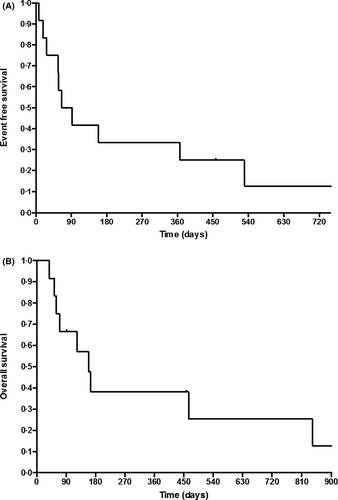

Four patients underwent HSCT after InO, two of them are disease-free with a mean follow-up of 23 months. One patient underwent a chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T cell) infusion but relapsed 13 months later. Two patients relapsed upon InO therapy (27 and 65 days from first injection) and one relapsed 72 days after the first cycle. Ten out of 12 patients died, nine from relapse or progression and one from cardiotoxicity during HSCT. At 12 months, EFS was 33% ± 13·6% [IC 95% (0·15–0·74)] and OS 38% ± 14% [IC 95% (0·18–0·81)] (Fig 2A, B).

Grade 3/4 hepatic toxicities were reported in 4/12 patients after the first course of InO: grade 3 transaminase elevation and mild SOS for one patient and grade 3 GGT increase without hyperbilirubinemia for three other patients. After the second course, one patient developed cytolysis with grade 3 transaminitis and grade 4 hyperbilirubinemia without SOS criteria, in a context of disease progression. During subsequent HSCT, 2/4 patients developed SOS, which resolved with no sequelae. No potential risk factor was observed, which included the number of doses of InO, the days between the last dose of InO and HSCT, and prior HSCT. There was no correlation between transaminase or bilirubin elevation during InO and occurrence of SOS following HSCT. Haematologic toxicities of grade 3/4 were frequent: neutropenia occurred in up to 83% of patients during the first cycle, 50% of whom were associated with infection. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia and anaemia were observed in up to 75% and 33% of patients, respectively, during the first course of InO. Infusion reactions (grade 1 and 2) and tumor lysis syndrome (grade 3) were observed in three patients. No death was related to InO.

Lymphocyte subpopulations were studied in four patients: B-cell aplasia post InO was documented as soon as day 8 of cycle 1 and as late as day 16 after the last injection (Table SII).

Prior to this study, five children had been treated with InO in an adult phase II trial: one achieved CR, and two CRi, but all relapsed subsequently.6 The toxicity profile was comparable to their adult counterpart: infrequent hepatic toxicity and one SOS following HSCT.

A recent international retrospective study reported 51 patients ≤ 21 years old who received InO through a compassionate use program using the weekly dose.7 Two of them are also reported in our study. CR/CRi was obtained in 67% of patients, 71% of them showing MRD negativity. Nevertheless, MRD was evaluated either by PCR or Flow Cytometry (of lower sensitivity). Incidence of SOS was high: 52% of patients post-HSCT, from mild to severe, with two deaths. Modulation of CD22 cell surface expression has been proposed as an escape mechanism and was identified in one of our patients. Loss of CD19 was also described with blinatumomab or CAR-T cell therapy.8, 9

InO can be effective and safe in r/r CD22-positive B-ALL paediatric patients. Best outcomes were obtained in patients who achieved early MRD negativity. Interestingly, all four patients studied (from D8 of cycle 1 to D27 of cycle 2) had CD3+ T-cells > 150/mm3, a threshold used for feasibility of leukapheresis, and could therefore benefit from CART cell therapy (Table SII). As CD19 is currently the main target of CAR-T cells, using InO before would not have selected for CD19-negative clones, a risk being identified after blinatumomab exposure.

Prospective paediatric clinical trials are currently evaluating InO's toxicities and efficacy in children and adolescents affected by B-ALL10. This will help us define the exact place of InO in this context.

Acknowledgements

CC reviewed the literature, collected and analysed data and wrote the manuscript. BB, AB and CC designed the study. ACH, DA, BBru, LB, MDT and GWP provided clinical data and patients. NB, AB and BB analysed the data. JV performed the flow cytometry analysis. All authors read, provided comments and approved the final version of the manuscript.