Publish and perish: how plagiarism can penalize perpetrators

We should ignore whining about the supposedly awful pressures of ‘publish or perish’ when we have little credible evidence on what motivates misconduct, or on what motivates the conduct of honest, equally stressed colleagues. Laziness, desire for fame, greed and an inability to distinguish right from wrong are just as likely to be at the root of the problem.1

Academic authors have a moral obligation to credit others accurately and fully for their work. Imagine my surprise at being alerted to four separate episodes of apparent plagiarism in papers currently undergoing peer review in the BJD. How could this happen? The reasons are complex, but not altogether surprising. Before analysing this, let us consider the context.

In 2005, Martinson et al.2 published an overview of what research misconduct is generally accepted to be. They described how such misconduct manifests and estimated its extent. In the same year, a common definition of research misconduct was reissued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, with plagiarism defined as follows: ‘Plagiarism is the appropriation of another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit’. They went on to note that, ‘Research misconduct does not include honest error or differences of opinion’.3

The U.S. Office of Research Integrity (ORI) now provides the following working definition of plagiarism: ‘ORI considers plagiarism to include both the theft or misappropriation of intellectual property and the substantial unattributed textual copying of another's work. It does not include authorship or credit disputes. Substantial unattributed textual copying of another's work means the unattributed verbatim or nearly verbatim copying of sentences and paragraphs which materially mislead the ordinary reader regarding contributions of the author’.4

The so-called big three of publication ethics abuses are fabrication, falsification and plagiarism; all three are forms of misrepresentation in scientific publication. The AMA Manual of Style gives a more detailed definition of plagiarism as follows.

‘In plagiarism, an author documents or reports ideas, words, data, or graphics, whether published or unpublished, of another as his or her own and without giving appropriate credit. Plagiarism of published work violates standards of honesty and collegial trust and may also violate copyright law’.5 They go on, ‘Four common kinds of plagiarism have been identified. (i) Direct plagiarism: verbatim lifting of passages without enclosing the borrowed material in quotation marks or crediting the original author. (ii) Mosaic: borrowing the ideas and opinions from an original source and a few verbatim words or phrases without crediting the original author. In this case, the plagiarist intertwines his or her own ideas and opinions with those of the original author, creating a ‘confused, plagiarized mass’. (iii) Paraphrase: restating a phrase or passage, providing the same meaning but in a different form without attribution to the original author. (iv) Insufficient acknowledgement: noting the original source of only part of what is borrowed or failing to cite the source material in a way that allows the reader to know what is original and what is borrowed. The common characteristic of these kinds of plagiarism is the failure to attribute words, ideas or findings to their true authors, whether or not the original work has been published’.5

How does plagiarism come to light? Usually, by one of the following five mechanisms: (i) use of originality-screening software; (ii) an alert peer reviewer; (iii) an alert associate editor; (iv) an alert technical editor after acceptance but before publication or (v) an alert journal reader through postpublication peer review. Why not simply use originality-screening software on all papers? Unfortunately, this software provides a clue, but not the diagnosis. This editorial, for example, includes chunks of text that would be spotted by such software as having been lifted verbatim from other sources. The software is not yet smart enough to recognize appropriate attribution when the source has been clearly identified, and the text enclosed within quotation marks. Thus, when plagiarism is suspected, careful analysis of the suspect text is the editor's first responsibility. Unfortunately, all five ways by which plagiarism might be detected depend on the academic and publishing communities being alert. I say unfortunately, as this is one more job on top of many others for busy people who may already feel pressured for time. Running an originality check is extra work that requires someone to decide that it is needed. The peer reviewers, associate editors and technical editors already have plenty to think about without having to consider the possibility of plagiarism, fabrication or falsification. BJD readers have been encouraged to do more postpublication peer review, and the BJD is committed to supporting this through the correspondence section.6 It is only through collective alertness by all concerned that this malign practice can be minimized and eradicated.

What is the BJD doing to tackle plagiarism? The BJD recognizes the need to commit energy and resources to promoting best practice for all publication ethics issues, including plagiarism. But how best to do this as a single journal? By collective action where there is combined strength and unity of purpose. The BJD has three main resources for such collective action: membership of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE); our publisher, Wiley; and the Council of Dermatology Editors. COPE was established in 1997 and has rapidly grown to become the overarching umbrella organization for editors of academic journals interested in publication ethics. In addition to regular meetings and online forums for editors, COPE also provides advice on how to handle cases of research and publication misconduct based on their excellent flowcharts. Wiley is one of several major publishers who have enrolled their journals as COPE members. Additionally, in 2006 Wiley was the first major publisher to create and publish its own best practice guidelines on publication ethics, updated in 2014, and published simultaneously in five Wiley journals.7 An integral element of the support Wiley provide to their journal editors is an ethics helpdesk, an e-mail address for triage of incoming queries to the person at Wiley with the most appropriate expertise. The BJD is currently working with Wiley to create a publication ethics strategy for the journal commensurate with its place as a leader in the field of dermatology. Finally, editors of dermatology journals meet up annually at the Council of Dermatology Editors, to discuss the shared agenda, which includes publication ethics. This forum is ideal for sharing ideas and promoting best practice within the dermatology publishing community.

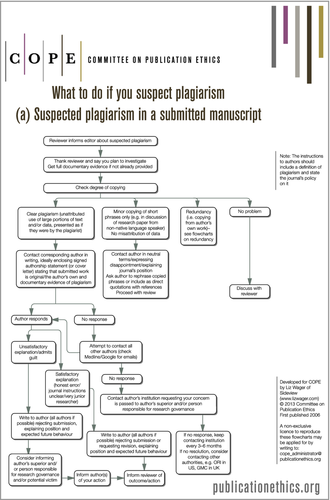

Returning to the four possible plagiarism cases that opened this editorial, how were they dealt with? Each case is confidential; it would therefore be inappropriate to share their details here. Suffice to say that they were initially spotted by a peer reviewer (n = 1), a section editor (n = 2) and a technical editor (n = 1). Each case of suspected plagiarism is dealt with by following the appropriate flowchart on the COPE website; there are 16 COPE flowcharts, two of which apply to plagiarism (one for submitted articles, the other for published articles). The sequence starts (Fig. 1) with someone in the publishing process realizing that plagiarism may have occurred and alerting the editor. The editor must then look at the information and see whether there may be a case to answer. If there is clear evidence of plagiarism (unattributed use of large portions of text and/or data, presented as if they were by the plagiarist), the corresponding author is contacted by the editor in writing, enclosing a copy of their signed authorship statement (stating that the submitted work is original and the author's own) and documentary evidence of plagiarism. It is then a matter for the editor and the corresponding author to follow the steps in the flowchart until the issue has been resolved.

The flowchart should make gloomy reading for plagiarists. Those who accept guilt receive a letter from the editor copied to their coauthors rejecting the submission, and explaining the position and expected future behaviour. If this were not bad enough, the editor then considers the possibility of informing the author's superior and/or the person responsible for the research. For plagiarizing authors, failure to respond to the editor opens up a more serious sequence of events (Fig. 1), including contacting the coauthors, the author's institution and ultimately their national professional licensing authority (for example the General Medical Council in the U.K.). If the journal editor receives a satisfactory explanation from the corresponding author (Fig. 1), the outcomes include rejection of the article, explaining the position and expected future behaviour of the authors, or revision of the manuscript to exclude the plagiarized sections. As for most bad things in life, prevention is the best course of action.

But how to prevent plagiarism? Firstly, through education of all concerned. Research supervisors have a responsibility to train their students to become excellent scientists; this includes a thorough understanding of publication ethics, including plagiarism. Secondly, journals such as the BJD can train junior authors in publication ethics. Investment in such training is likely to pay back with an enhanced reputation for the journal and author loyalty. Thirdly, by training journal editorial teams and peer reviewers how to identify plagiarism and the importance of spotting and reporting it. It should not be forgotten that proven plagiarism may have a devastating effect on a researcher's career. Editors have a responsibility to judge each case individually, assessing the degree of textual overlap and considering whether this might have been accidental or unintentional. As with other publication ethics issues, plagiarism may be nuanced, requiring a subtle, even sympathetic approach by the editor. Finally, prevention of plagiarism requires excellent role modelling from the academic community. Only two countries (Norway and Denmark) have enshrined publication ethics within law. Other countries have chosen not to go down this path, perhaps recognizing the danger of stifling freedom and creativity, which are essential to science; too many rules may alienate the contributors. In the absence of a legal framework it behoves us all to encourage and promote the highest ethical standards in publishing by leading by example. In the context of the current research culture, junior researchers need close supervision and support in order to avoid the temptation to compromise their research integrity.8-10

Acknowledgments

Julie Browne, Irene Hames and the Wiley Publication Ethics Team, Oxford, U.K.