Otolith-based species identification in the killifish Aphaniops (Teleostei; Cyprinodontiformes; Aphaniidae) using both morphometry and wavelet analysis

Abstract

The killifish genus Aphaniops consists of nine species distributed in Eastern Africa and the Middle East. However, distinguishing these species from each other based on morphological traits is challenging. Here we investigate the utility of otoliths (sagittae) in distinguishing between A. dispar, A. ginaonis, A. hormuzensis, A. kruppi and A. stoliczkanus. Our approach is based on otoliths from 89 specimens and involves (1) otolith morphometrics, following prior recommendations, (2) shape analysis of otolith contours based on discrete wavelet transformation—a novel method in killifish otolith research—and comparative statistical analyses. Both methods reveal significant interspecific variation in the otolith regions of the rostrum, antirostrum and excisura. While method (1) effectively discriminates most species, method (2) struggles to differentiate A. hormuzensis, A. stoliczkanus and A. kruppi. Additionally, both methods encounter challenges in correctly classifying A. hormuzensis due to the high otolith variability of this species in our sample. Possible factors accounting for their variability are environmental fluctuations at the sampled hot sulphuric spring (Khurgo) and potential introgressive hybridization. We conclude that otolith morphometry is a valuable tool for Aphaniops species identification. Furthermore, we found that the distinctiveness of species-specific otolith traits increases with the divergence age of the species.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Old World killifish family Aphaniidae (order Cyprinodontiformes, toothcarps) is an important component of coastal and brackish faunas of the Mediterranean Sea, Dead and Red Sea, Persian Gulf, western Indian Sea and surrounding regions, and also occurs in the inland of Anatolia and Iran (Esmaeili et al., 2014; Freyhof & Yoğurtçuoğlu, 2020; Teimori et al., 2018; Wildekamp, 1993). Owing to its high environmental tolerance and adaptability, Aphaniidae has been used as model for studying various aspects, including micro-evolutionary processes and species diversification when populations become isolated (e.g. Buj et al., 2015; Cavraro et al., 2017; Chiozzi et al., 2018; Ferrito et al., 2007; Gonzalez et al., 2018; Teimori et al., 2018).

The taxonomic content of the Aphaniidae has undergone extensive revisions over the last decade, leading to the erection or re-validation of new genera and species (e.g. Esmaeili et al., 2020; Freyhof & Yoğurtçuoğlu, 2020; Freyhof et al., 2017; López-Solano et al., 2023; Teimori et al., 2018). One such example is the re-validation of the genus Aphaniops Hoedeman, 1951 by Esmaeili et al. (2020). The main distribution area of Aphaniops is the Red and Dead Sea, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, western Indian Sea and adjacent drainage basins. Initially, almost all aphaniid species in these regions were regarded as Aphanius dispar (Rüppell, 1829) (Hrbek & Meyer, 2003; Krupp, 1983; Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009; Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Teimori, Jawad, et al., 2012; Teimori, Schulz-Mirbach, et al., 2012; Teimori et al., 2018; Wildekamp, 1993). Now it has been established that Aphaniops dispar is limited to the Red Sea and that the further members of the previous dispar species group represent eight more species of Aphaniops, of which several were only recently identified or revalidated based on mitochondrial markers and a combination of morphological characters (Esmaeili et al., 2020; Freyhof et al., 2017; Teimori et al., 2018, 2022).

Of particular interest are the Aphaniops species inhabiting the Persian Gulf area of southern Iran and Oman, as their diversification can be linked to the geological history of the region (Hrbek et al., 2002; Teimori et al., 2014, 2018). Five species have been identified from this region, of which A. stoliczkanus (Day 1872) is the only species exhibiting a wide distribution in the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea and the surrounding areas (Bidaye et al., 2023; Freyhof et al., 2017). Three of the further species are endemic to the Hormuzgan Basin (southern Iran), namely A. ginaonis (Holly, 1929) (Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009), the scaleless A. furcatus (Teimori et al., 2014) and A. hormuzensis (Teimori et al., 2018). The fifth species is A. kruppi (Freyhof et al., 2017), which is known from localities in Oman and Yemen (Esmaeili & Hamidan, 2023; Esmaeili et al., 2020; Freyhof & Yoğurtçuoğlu, 2020; Freyhof et al., 2017; Zarei, Masoumi, et al., 2023).

Notably, except for A. furcatus (which has no scales), distinction among these species, and also their distinction from A. dispar, based on body morphology remains difficult due to overlaps in morphometric and meristic characters. To overcome this, otolith morphology has been suggested as an additional taxonomic tool for these species (Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Teimori et al., 2018), but with limited quantitative data to support it. The objective of this study is to examine whether otolith morphometry can reinforce a clear species separation among A. dispar, A. ginaonis, A. hormuzensis, A. kruppi and A. stoliczkanus. We used two approaches, that is, (1) statistical analysis of ten otolith variables and five shape indices (which are considered a measure of the otolith outline shape) and (2) outline shape analysis employing discrete wavelet transformation and using the produced wavelet coefficients as variables for statistical analyses. The results of our study indicate that otolith morphology combined with statistical analysis is a useful tool in species distinctions. Although the degree of success in species separation might differ between the methods used here, both can provide valuable insights into the taxonomic value of otolith morphology.

1.1 Otoliths

Otoliths are calcium carbonate increments inside membranous sacs of the inner ear of teleosts (Panfili et al., 2002). They form three pairs of mineralized structures called sagittae, lapilli and asterisci, which are each located in a distinct otolithic end organ (Parmentier et al., 2007). Otoliths serve as a tool to sense balance and sound and are associated with important biological functions such as feeding, swimming or intraspecific communication (Ghanbarifardi et al., 2020; Lombarte et al., 2010; Popper et al., 2005; Schulz-Mirbach et al., 2019). Among the three pairs, sagittae are mostly used in research, as they are usually the larger and easier to recover pair (Assis, 2005). Comparative study of sagitta morphology is a well-established taxonomic approach for species and genus identification (Nolf, 1985, 2013), even in the case of closely related sympatric species (Reichenbacher & Reichard, 2014; Reichenbacher et al., 2023; Zarei, Esmaeili, et al., 2023). Furthermore, the use of otolith morphometrics, geometric landmarks and otolith shape analysis can produce quantifiable and comparable results and thus represents a robust complementary tool in taxonomy and also in evaluating genetic results or life history hypotheses (Castonguay et al., 1991; Tracey et al., 2006; Tuset et al., 2016, 2019).

Otolith morphology (and morphometry) has been applied successfully to separate between species of Aphaniidae suggesting that their otoliths are species-specific and can assist in species discrimination (e.g. Gholami et al., 2014; Reichenbacher et al., 2007; Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Teimori et al., 2014, 2018). However, quantitative otolith data for closely related species of Aphaniops, specifically focusing on interspecies comparisons, are almost non-existent. Most studies have focused on employing such methods to explore intraspecific otolith variation, that is, variation within and between populations of individual Aphaniops species (Bidaye et al., 2023; Herbert Mainero et al., 2023; Masoumi et al., 2024; Motamedi et al., 2021; Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009; Teimori, Iranmanesh, et al., 2021; Teimori, Motamedi, & Zeinali, 2021).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Fish sampling, otolith extraction, SEM imaging

We used a total of 117 specimens from southern Iran, Saudi Arabia and Oman, encompassing Aphaniops dispar, A. hormuzensis, A. kruppi and A. stoliczkanus, for the extraction of their otolith pairs (see Table 1 and Figure 1 for details on sampling points, habitats, sample sizes, sex and specimen sizes). To test the utility of morphometry, particularly outline analysis—which has not yet been applied to comparisons of Aphaniops species—in distinguishing between species, single populations were used for each species to minimize the known impact of geographic variation on otolith morphology (see above). The sampling was done in the years 2017–2019 and complied with protocols approved by the responsible governmental authorities (according to the countries where the sampling was conducted). Species identification was additionally confirmed for three captive-bred A. kruppi based on cyt b (see Charmpila et al., 2020) and for the wild-caught A. kruppi based on CO1 gene markers (Freyhof et al., 2017; Freyhof pers. comm.). Furthermore, 48 left otoliths of A. ginaonis were available from the previous work of Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al. (2009).

| Species | N (M/F) | SC1, SL 20–32 | SC2, SL > 32–39 | SC3, SL > 39 | Sampling site, country | Habitat | Human impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. dispar | 9 (5/4) | 9 (5/4) | Al Arbaeen (21°17′26.9″N 39°06′15.5″ E), Saudi Arabia | Aquarium-bred | – | ||

| A. ginaonis | 48 (14/20) | 33 (11/5) | 15 (3/15) | Genow (56°17′97″ E 27°26′77.2″N), Iran | Hot sulphuric spring | Touristic interest | |

| A. hormuzensis | 22 (10/12) | 17 (9/8) | 5 (2/3) | Khurgo (27°31′34.1″N 56°28′08.2″ E), Iran | Hot sulphuric spring | Touristic interest | |

| A. kruppi | 16 (7/9) | 8 (3/5) | 8 (4/4) captive bred | Al Mudayrib (22°36′46″N 58°40’31″E), Oman | Seasonal water pools | ||

| A. stoliczkanus | 22 (12/10) | 22 (12/10) | Mirahmad (27°48′56.4″N 51°16′50.9″ E), Iran | Hot sulphuric spring | Touristic interest | ||

| Total | 117 | 89 | 20 | 8 |

- Abbreviations: F, number of female specimens; M, number of male specimens; SC1, size class 1; SC2, size class 2; SC3, size class 3; SL, standard length of fish individual in mm.

Left and right saccular otoliths (termed otoliths in the following text) were extracted dorsally. Following the protocol of Reichenbacher et al. (2007), residual tissues were removed by immersing the otoliths in a 1% KOH solution for 3 hours, followed by rinsing in distilled water for 4 hours. If necessary, the procedure was repeated, and the otoliths were then stored in distilled water overnight. To reduce possible effects of variation associated with ontogeny or right–left otolith asymmetry, otoliths were sorted into size classes of standard length (Table 1) and only left otoliths were used (exceptionally two right otoliths were used because their left counterparts could not be retrieved).

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging, otoliths were mounted on aluminium pin stubs (12.5 mm in diameter, 3.2 × 8 mm), to which adhesive tabs had been applied. A thin (20 nm) gold coating was applied to the stubs (sputter coating) in a high vacuum coater. The pin stubs were then inserted into the HITACHI SU 5000 Schottky FE-SEM at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (LMU Munich), and a current of 15 kV was applied. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop.

2.2 Method 1—Otolith morphology and morphometry

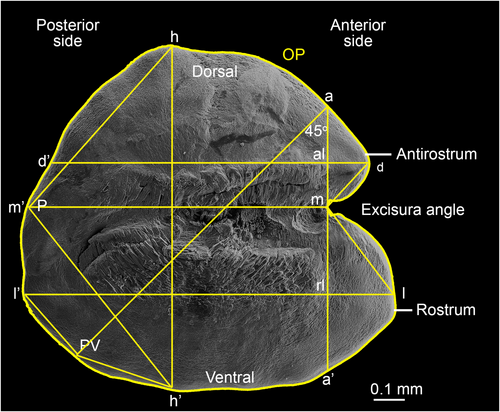

Morphological and morphometric otolith analyses were conducted based on the SEM images of the otoliths. For morphological descriptions of otoliths, the established otolith terminology, as shown in Figure 2, was used (Nolf, 1985; Reichenbacher et al., 2007; Smale et al., 1995; Tuset et al., 2008).

Morphometric analysis was conducted with ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) and followed the methodology introduced by Reichenbacher et al. (2007) for otolith variables, and Tuset et al. (2003) and Bani et al. (2013) for otolith shape indices. SEM images were oriented so that the ventral margin and the sulcus acusticus of the otolith were essentially horizontal (Figure 2). According to Reichenbacher et al. (2007), eight linear distances and three angles were measured for each of the otoliths (Figure 2, Table 2). Linear measurements were standardized as a function of either otolith length (OL) or height (OH), which resulted in 10 variables that were used in the statistical analyses. Following Bani et al. (2013), four morphometric measurements (otolith perimeter, otolith area, and maximum and minimum value of ferret diameter calculated at angles of 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 degrees) were calculated and combined in morphometric equations to produce five shape indices (Table 2).

| Abbreviation | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Otolith variables | ||

| D (% of OL) | Relative dorsal length | (d-d'/l-l’) × 100 |

| M (% of OL) | Relative medial length | (m-m’/l-l’) × 100 |

| A (% of OH) | Relative antirostrum height | (m-a/h-h’) × 100 |

| R (% of OH) | Relative rostrum height | (m-r/h-h’) × 100 |

| AL (% of OL) | Relative antirostrum length | (al-d/l-l’) × 100 |

| RL (% of OL) | Relative rostrum length | (rl-l/l-l’) × 100 |

| LH (% of OH) | L/H-Index | (l-l’/h-h’) × 100 |

| P (°) | Posterior angle | Angle h-m’-h |

| E (°) | Excisura angle | Angle d-m-l |

| PV (°) | Posteroventral angle | Angle l’-x-h’ |

| Shape Indices | ||

| Ff | Form factor | (4πA) P−2 × 100 |

| C | Circularity | P2A−1 |

| Ro | Roundness | (4A) (πFL2) −1 × 100 |

| Rt | Rectangularity | A (FL × FW) −1 × 100 |

| El | Ellipticity | (FL − FW) (FL + FW) −1 × 100 |

- Abbreviations: A, area (in mm2); FL, maximum and FW, minimum value of feret diameter (in mm) calculated at angles of 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 degrees; P, perimeter (in mm).

Univariate statistical analysis was performed based on the morphometric data obtained from the otoliths of size class 1 (20 mm ≤ SL ≤ 32 mm) using RStudio v 2023.3 (Posit Team, 2023). Violin plots for otolith variables, shape indices, and standard lengths were plotted for each species using Ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016). Normality of distribution was tested for each of the otolith variables and shape indices with Shapiro–Wilk's test for each species and for each sex within a species (p < 0.01, if non-normal). All variables and indices were normally distributed, so there was no need for transformation of values to fit a normal distribution. Sex differences for each species were tested with Student's t-test (p < 0.01) (no sex comparisons were possible for A. dispar and A. kruppi due to low sample sizes). As sex differences were not significant (p > 0.01) for A. ginaonis, A. hormuzensis (except antirostrum length and excisura angle) and A. stoliczkanus, female and male specimens were pooled for each species. One-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests was used to test the significance of differences in individual otolith variables and shape indices between groups. The homogeneity of variances was tested with Levene's test. In the case of heterogeneity (p < 0.01), individual variables were tested for differences with Tamhane's-T2 test (p < 0.01), and in the case of homogeneity, Duncan's (p < 0.01) post-hoc test was conducted.

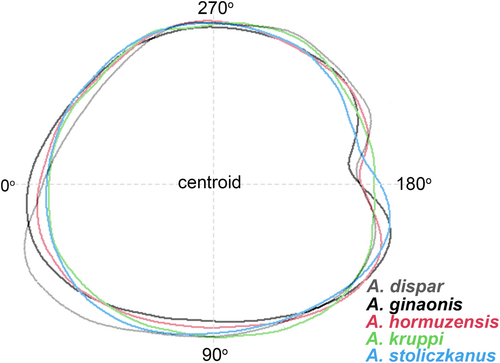

2.3 Method 2—Otolith shape analysis

Otolith outlines were extracted and generated with the ShapeR 0.1–5 package for R (Libungan & Pálsson, 2015) from the SEM images. Images were previously stored in JPEG format (*.jpg) with increased contrast between the otolith and the background, increased brightness of the otolith, and rotated with the rostrum to the left according to Libungan and Pálsson (2015). Equally spaced radii were drawn out starting horizontally from the otolith centroid to the otolith outline with the first drawn radius representing the 0° angle of the otolith outline and the following radii continuing counter clockwise until 360°; X and Y coordinates (polar coordinates) were collected from the drawn radii (Libungan & Pálsson, 2015). To reduce pixel noise, the “smoothout” function of ShapeR was set to 100 iterations. The polar coordinates were returned as wavelet coefficients after implementation of the wavelet transformations with the R package Wavethresh 4.6.8 (Nason, 2016). As no significant sex differences were indicated through method (1), samples were pooled for each species. Mean otolith shapes were plotted for each species using wavelet coefficients. The built-in function in the packages ShapeR and Wavethresh 4.6.8 employs a normalization technique based on regression (Lleonart et al., 2000) to remove the effect of allometric growth on otolith size. This involves scaling the wavelet coefficients with standard fish length (Libungan & Pálsson, 2015). Additionally, coefficients showing a significant interaction between species and fish length (p < 0.01) were automatically omitted from subsequent analyses. Finally, otolith outlines were reconstructed based on standardized wavelet coefficients (Libungan & Pálsson, 2015). The variation of the standardized wavelet coefficients along the otolith outline was shown by plotting the mean and standard deviation of coefficients against the otolith outline angle—see above (Libungan & Pálsson, 2015). Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP) with the standardized wavelet coefficients as variables was used to uncover patterns among species on canonical plots with the use of the function capscale in the R package Vegan 2.5–7 (Oksanen et al., 2020). The constrained ordination of species averages along the first two canonical axes from CAP was assessed graphically (plot not shown). The significance of the joint effect of wavelet coefficients on species ordination was examined with an ANOVA-like permutation test, also implemented in Vegan.

2.4 Further statistical analysis (for both methods 1 and 2)

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) with leave–one–out cross validation was performed for each dataset of the two methods to test for the significance of each dataset in species discrimination. The following packages in R and their functions were used for this: the lda function in the MASS 7.3–60.0.1 (Venables & Ripley, 2002) package and the confusion Matrix function in the Caret (Kuhn, 2008) package. Linear discriminant functions were plotted against each other with Ggplot2.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Results of otolith morphology

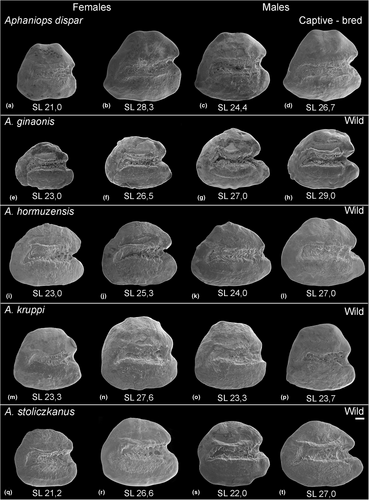

The otoliths of the studied Aphaniops species display the general characteristics of the genus in the following traits: (i) the shape is generally rounded-trapezoid to elongated-trapezoid and the margins are smooth; (ii) the well-formed heterosulcoid sulcus acusticus is in median position and extends more than ¾ of the length of the otolith; (iii) the sulcus opening is ostial and the cauda is markedly curved in its posteroventral end; (iv) the slightly deepened tubular ostium is usually shorter compared to the cauda (Figures 3 and 4). In addition, differences in specific otolith characters are identifiable in each species (Figures 3 and 4) and are summarized in Table 3. In short, A. dispar otoliths display two dorsal tips and a posteroventral projection, a short but well-formed rostrum and antirostrum and a deep excisura angle (Figure 3a–d). None of the other studied species displays a clear dorsal tip (Figure 3e–t), with very few exceptions, especially among the otoliths of A. hormuzensis (Figure S2). Aphaniops ginaonis and A. hormuzensis otoliths exhibit a medium-sized, more or less pointed rostrum and antirostrum, a V-shaped deep excisura angle (Figure 3e–l, Table 3), while the posterior margin is slightly more rounded and more symmetrically shaped in A. ginaonis. Additionally, high overall variability was noted in the A. hormuzensis subset (n = 22) (Figure S2). The otoliths of A. kruppi display a rounded-triangular outline with a short, rounded or truncated broad rostrum and U-shaped excisura angle (Figure 3m–p). Notably, the otoliths from the wild-caught A. kruppi specimens display a less developed antirostrum and shallower excisura angle as seen in the captive-bred A. kruppi (Figure 3m–p vs. Figure S1, Table 3). Aphaniops stoliczkanus exhibits a short to medium-sized round rostrum, a well-defined antirostrum and a U-shaped, moderately deep excisura (Figure 3q–t, Table 3).

| Species | A. dispar | A. ginaonis | A. hormuzensis | A. kruppi “wild” | A. kruppi captive | A. stoliczkanus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 9 | N = 48 | N = 22 | N = 8 | N = 8 | N = 22 | |

| Shape outline | Trapezoid | Elongated trapezoid | Rounded trapezoid to elongated | Rounded triangular | Rounded triangular | Discoidal |

| Excisura | Round or acute, deep | Acute (V-shaped), deep | Acute (V-shaped), deep | Round (U-shaped), shallow | Round (U-shaped), deep | Round (U-shaped), shallow |

| Rostrum | Short, round, broad | Medium-sized, pointed, thin | Medium-sized, round to pointed, thin | Short, round, broad | Short, round, broad | Short to medium-sized, round, broad |

| Antirostrum | Short, pointed | Medium-sized, round to pointed | Medium-sized, round | Poorly defined | Medium-sized, round | Short to poorly defined, round |

| Rostrum relative to antirostrum | Same length | Longer | Mostly longer | Slightly longer | Same length | Slightly longer |

| Anterior region | Double-peaked | Double-peaked | Double-peaked | Round | Double-peaked | Round to slightly peaked |

| Posterior region | Oblique with posteroventral projection | Round | Round | Round | Round | Round |

| Dorsal rim | Weakly developed double tip | Smooth | Weakly developed tip (sometimes) | Smooth | Smooth | Smooth |

- Abbreviation: N, total number of specimens.

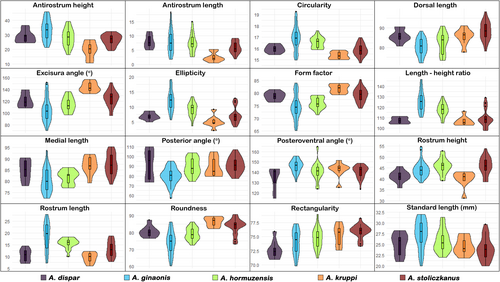

3.2 Results of otolith morphometry

Violin plots for otolith variables, shape indices, and standard lengths of each species are shown in Figure 4. The importance of each otolith variable in the separation among species was tested using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests (Duncan's test, if variance was homogeneous; Tamhane-T2 test in case of heterogeneous variances). Pairwise differences between species in otolith variables and indices are summarized in Table 4. In short, A. ginanonis differed significantly from all other species in the length–height ratio, circularity and ellipticity, which are all measures of overall shape. Furthermore, A. hormuzensis was significantly different vs. all species in the length–height ratio, and A. kruppi vs. all species in the antirostrum height and length and the excisura angle (Table 4). Moreover, otolith variables associated with the rostrum and antirostrum (heights and lengths), and overall otolith shape (length–height ratio, form factor, circularity) were significantly different between several species. The highest differentiation was shown for A. ginaonis and A. kruppi which differed vs. all other species respectively in several variables and indices (Table 4).

| Species | A. dispar | A. ginaonis | A. hormuzensis | A. kruppi | A. stolizckanus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 9 | N = 33 | N = 17 | N = 8 | N = 22 | |

| Otolith variables | |||||

| Dorsal length | gi | di, kr, st | st | gi | gi, ho |

| Medial length | kr, st | st | gi | gi, ho | |

| Antirostrum height | ho, st | gi | Δ | gi | |

| Rostrum height | ho, st | kr | di, kr | gi, ho, st | di, kr |

| Antirostrum length | Δ | ||||

| Rostrum length | gi, ho | di, kr, st | di, kr | gi, ho | gi |

| Length–height ratio | Δ | Δ | |||

| Excisura angle | st | Δ | gi | ||

| Posterior angle | gi | di, ho, st | gi | gi | |

| Posteroventral angle | gi | di | |||

| Shape indices | |||||

| Form factor | gi | di, kr, st | kr, st | gi, ho | gi, ho |

| Circularity | gi | di, kr, st | kr, st | gi, ho | gi, ho |

| Roundness | Δ | kr | ho | ||

| Rectangularity | ho, kr, st | st | di | di | di, gi |

| Ellipticity | Δ | kr | ho | ||

- Abbreviations: di, A. dispar; gi, A. ginaonis; ho, A. hormuzensis; kr, A. kruppi; st, A. stolizckanus; N, total number of specimens; Δ variable differs significantly (P < 0.01) between the indicated species and all other species.

3.3 Results of otolith shape analysis

Figure 5 shows the mean otolith outline of each species. Clear variation along the otolith outline was detected between 170° and 220°, corresponding roughly to the rostrum, excisura and antirostrum areas, and also between 10° and 70°, representing the posteroventral portion of the otoliths (Figure 5). CAP of standardized wavelet coefficients from all five species showed four principal coordinates with CAP1 (61.9%) and CAP2 (28.7%) explaining most of the variation in otolith shape, but species were overlapping when plotted against CAP1 and CAP2 (plot not shown). The results of the overall and pairwise ANOVA-like permutation tests to evaluate the significance of otolith shape variation among species are summarized in Table 5. The outcome indicated significant differences in otolith shape (p < 0.01) between almost all species pairs, but not for A. ginaonis versus A. hormuzensis, A. hormuzensis versus A. kruppi and A. kruppi versus A. stoliczkanus.

| Species | Sum of squares | F-value | P-value | Df |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All species | 32.772 | 7.063 | 0.001 | 4 |

| A. dispar v A. ginaonis | 16.689 | 14.243 | 0.001 | 1 |

| A. dispar v A. hormuzensis | 8.5594 | 8.4905 | 0.001 | 1 |

| A. dispar v A. kruppi | 3.4061 | 3.6202 | 0.004 | 1 |

| A. dispar v A. stoliczkanus | 11.134 | 12.214 | 0.001 | 1 |

| A. ginaonis v A. hormuzensis | 4.359 | 3.3961 | 0.017 | 1 |

| A. ginaonis v A. kruppi | 8.448 | 6.3931 | 0.001 | 1 |

| A. ginaonis v A. stoliczkanus | 12.110 | 10.052 | 0.001 | 1 |

| A. hormuzensis v A. kruppi | 2.574 | 2.0299 | 0.083 | 1 |

| A. hormuzensis v A. stolicz. | 5.621 | 5.05 | 0.003 | 1 |

| A. kruppi v A. stoliczkanus | 2.5632 | 2.3078 | 0.046 | 1 |

- Note: Results from ANOVA like permutation tests based on 1000 permutations, df: degrees of freedom, F-value: Pseudo F-value, P-value: Proportion of permutations which gave as large or larger F-value than the observed one, significant result in bold.

3.4 Results of multivariate analysis

Overall classification of otoliths after cross validation for the dataset of otolith variables and shape indices yielded 78.7% success (Table 6, Figure S3). In contrast, overall classification success after cross validation for the dataset of standardized wavelet coefficients was only 40% (Table 6). In both datasets, A. dispar had the highest score of correct classification (Table 6).

| Predicted classification | N | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otolith variables + shape indices | Wavelet coefficients | ||||||||||

| Obtained classification | |||||||||||

| Species | di | gi | ho | kr | st | di | gi | ho | kr | st | 89 |

| A. dispar | 89 (8) | 0 | 11 (1) | 0 | 0 | 78 (7) | 0 | 11 (1) | 11 (1) | 0 | 9 |

| A. ginaonis | 0 | 82 (27) | 6 (2) | 0 | 12 (4) | 3 (1) | 51 (17) | 27 (9) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | 33 |

| A. hormuzensis | 6 (1) | 17 (3) | 65 (11) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 0 | 35 (6) | 29 (5) | 6 (1) | 29 (5) | 17 |

| A. kruppi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88 (7) | 12 (1) | 13 (1) | 0 | 13 (1) | 13 (1) | 63 (5) | 8 |

| A. stoliczkanus | 0 | 9 (2) | 5 (1) | 9 (2) | 77 (17) | 0 | 14 (3) | 32 (7) | 27 (6) | 27 (6) | 22 |

- Note: Values in rows represent percentages (%) of classification into the given species in the columns, numbers of classified otoliths is in brackets. Correct classification indicated in bold.

- Abbreviations: di, A. dispar; gi, A. ginaonis; ho, A. hormuzensis; kr, A. kruppi; st, A. stoliczkanus; N, number of otoliths.

4 DISCUSSION

Several otolith variables and indices have been introduced to facilitate morphometric comparisons between otoliths and have been explored for their potential to separate the otoliths of different species (Annabi et al., 2013; Avigliano et al., 2018; Bani et al., 2013; Reichenbacher et al., 2007; Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009; Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Tuset et al., 2003, 2006; Zarei, Esmaeili, et al., 2023). In addition, shape analysis of otolith contours with the implementation of elliptic Fourier or discrete Wavelet transformations (Parisi-Baradad et al., 2005; Rohlf, 1990) has been widely used for population and stock differentiations (Campana & Casselman, 1993; Libungan et al., 2015; Sadeghi et al., 2020; Tuset et al., 2003). Some further studies indicate that these methods can also provide promising results for species separation (Bani et al., 2013; Gut et al., 2020; Lord et al., 2012; Tuset et al., 2006) and hybrid differentiations (Berg et al., 2018). Here, while otolith variables and indices helped distinguish between the studied Aphaniops species, wavelet coefficients were less successful in discerning between the studied species.

4.1 Distinctions among Aphaniops species using otoliths

Previous studies on the otolith morphology of Aphaniops have suggested that the otoliths of species within this genus possess species-specific characteristics, as well as features that differentiate among populations (Reichenbacher et al., 2007; Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009; Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Teimori, Schulz-Mirbach, et al., 2012). Specifically, the otolith length–height ratio, the relative height of both the antirostrum and rostrum, and the relative length of the rostrum are characters that vary among species. In contrast, characters associated with the excisura and posterior angle, along with the relative medial length and relative antirostrum length, are suitable for distinguishing among populations. Notably, in our study, the excisura angle and antirostrum length were variables that contributed to the distinction of the otoliths of A. kruppi from the other species (see below).

4.2 Distinction of Aphaniops dispar using otoliths

Among the here studied species, the otoliths of A. dispar were the most distinguishable in otolith morphology (Table 3). Although there is no otolith variable or shape index that distinguishes all species from one another (Table 4), multivariate analyses for each method successfully separated the otoliths of A. dispar based on their overall otolith shape (Table 6, Figure S3). According to the time calibrated phylogeny in Teimori et al. (2018), A. dispar diverged prior to the other Aphaniops species studied here in the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene (95% age credibility interval 9–4 million years ago [MYA]). The older age of A. dispar may be reflected in the more distinct morphology of its otoliths compared to the other Aphaniops species studied here. Another Aphaniops species, A. furcatus (not included in this study), which diverged from A. dispar in the middle Miocene (15.2–11.7 MYA) according to Teimori et al. (2018), also exhibits unique otolith morphology (Motamedi et al., 2021; Teimori et al., 2014). The idea that the geological age of a species can increase its otolith distinctness is further supported by the distinctive otolith morphology of two other species of the Aphaniidae, Esmaeilius vladykovi (Coad, 1988) and E. shirini (Gholami et al., 2014). Their otoliths are shown in Gholami et al. (2014: figure 4, as Aphanius). These two species may have diverged as early as the Middle or Late Miocene (Gholami et al., 2014). Additionally, E. vladykovi has been identified as the oldest species among the Iranian inland clade of the Aphaniidae (Esmaeili et al., 2014, as Aphanius).

4.3 Distinction among Aphaniops species from southern Iran using otoliths

According to Teimori et al. (2018), the divergence of A. ginaonis, A. hormuzensis and A. stoliczkanus occurred in the Late Pliocene–Early Pleistocene (3.2–2.0 MYA). Their relatively young geological age may account for the similarity of their otoliths, as revealed in our analyses (Figures 4 and 5). Nevertheless, otoliths of A. ginaonis were clearly distinguished from those of the other species due to their elongated shape (see shape index differences in Table 4 and otolith contour in Figure 5a). Aphaniops hormuzensis and A. stoliczkanus were less clearly distinguishable, particularly A. hormuzensis, whose classification based on the two methods did not yield high success; only the length–height ratio clearly separated it from all other species (Table 4). Visual inspection of the complete otolith sample of A. hormuzensis (n = 22) revealed considerable variability in otolith morphology (Figure S2), potentially posing a challenge for both methods in reliably distinguishing A. hormuzensis otoliths from those of other species.

4.3.1 Possible factors accounting for high otolith variability in A. hormuzensis

Sex dimorphism in otolith morphometry is known for some Aphaniops species (e.g. A. furcatus, see Motamedi et al., 2021; A. hormuzensis, see Teimori, Motamedi, & Zeinali, 2021), whereas other species do not show such dimorphism (e.g., A. kruppi, see Masoumi et al., 2024; A. stoliczkanus, see Herbert Mainero et al., 2023). In our sample of A. hormuzensis, sex dimorphism was weakly developed, with only two variables (antirostrum length, excisura angle) showing significant differences between sexes.

We suspect that environmental factors could also contribute to the high variability in otoliths of A. hormuzensis, as both genetic and environmental factors are known to significantly influence otolith morphology (Gholami, Esmaeili, Erpenbeck, & Reichenbacher, 2015; Lombarte & Lleonart, 1993; Vignon, 2012; Vignon & Morat, 2010). The Khurgo spring, where A. hormuzensis was collected, belongs to the Hormuzgan drainage system, which is a dryland water system with both perennial and intermittent rivers or streams, with water supply largely originating from mountain springs (Teimori et al., 2016, 2019). In such water systems, annual climate events, such as extended dry seasons or high precipitation, may cause strong fluctuations in environmental parameters like salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, minerals and food availability (Datry et al., 2014). It is plausible that these environmental instabilities affected otolith growth during the ontogenetic stages of fish individuals (see Geladakis et al., 2022; Vignon, 2018). Since otolith growth is associated with otolith morphology (D'Iglio et al., 2021), such growth irregularities may have led to increased intrapopulation variability in the otoliths of A. hormuzensis, as observed in our sample.

As a result, even though the otolith morphology of A. hormuzensis in our study is consistent with descriptions from previous works from the same site (Teimori et al., 2018; Teimori, Iranmanesh, et al., 2021), our sample exhibits more morphological variability, which may have led to less conclusive outcomes.

Another possible explanation for the observed otolith variation in the studied sample of A. hormuzensis may be the presence of hybrid offspring due to interspecific mating and subsequent backcrossing of hybrids into the parental lineages (see Funk & Omland, 2003). Although the complex geology and arid climate of southern Iran have led to the formation of endorheic river basins, frequently accompanied by the isolation of fish populations and subsequent allopatric speciation events (Gholami, Esmaeili, & Reichenbacher, 2015; Hrbek et al., 2002; Teimori et al., 2018), human activities may have reinstated gene flow between formerly isolated congeneric species. Teimori et al. (2016) mentioned that translocations of Aphaniops in Southern Iran are common due to their potential for mosquito control (Ali & Elamin, 2011; Ataur-Rahim, 1981). Furthermore, hybridization between aphaniids has been observed in nature (Villwock, 1985) and suggested in previous studies (Masoudi et al., 2016; Reichenbacher, Kamrani, et al., 2009; Zarei, Masoumi, et al., 2023). Schulz-Mirbach et al. (2008) suggested that hybrids of Poecilia (member of the Cyprinodontiformes, like Aphaniops) exhibit a mixture of otolith characteristics originating from both parental lineages, and the same can probably be assumed for hybrids of Aphaniops species. In this case, putative hybrids of species of Aphaniops could lead to increased intrapopulation variation.

In our sample of A. hormuzensis, a faint dorsal tip, which is a typical otolith characteristic of coastal A. stoliczkanus (see below), was observed in some specimens (Figure S2). Therefore, we propose that the A. hormuzensis population at Khurgo has experienced some hybridization with coastal populations of A. stoliczkanus, which could explain the high otolith variability observed in our sample. Future studies using both mitochondrial and nuclear markers of the species from this site should be conducted to test our hypothesis.

4.4 Otolith variation among A. stoliczkanus from inland and coastal sites

The studied otoliths of A. stoliczkanus from the Mirahmad hot mineral spring, a land-locked site in the Helleh Basin in Southern Iran, have a discoidal shape and lack a dorsal tip, which aligns with previous descriptions of this species from the same or other inland sites in Iran and Iraq (see Teimori, Jawad, et al., 2012, Teimori, Schulz-Mirbach, et al., 2012 [as A. dispar]; Teimori et al., 2018). Conversely, the coastal and coastal-associated populations of A. stoliczkanus in Reichenbacher et al. (2009, as A. dispar), Teimori et al. (2012, as A. dispar), Teimori et al. (2018) and Bidaye et al. (2023) always present a more triangular otolith shape with a more or less pronounced dorsal tip.

The formation of a dorsal tip on otoliths has been associated with environmental factors such as distance from the sea and salinity level (Bidaye et al., 2023; Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009; Teimori, Jawad, et al., 2012; Teimori, Schulz-Mirbach, et al., 2012; Teimori et al., 2018). However, an experimental study on reared specimens of purebred Atlantic herring and hybrid Atlantic/Baltic herring strongly suggests that salinity has minimal influence on otolith morphology, and that genetic factors are the primary driver of otolith variation (Berg et al., 2018). This suggests that coastal and coastal-associated populations of A. stoliczkanus from the Gulf of Oman may represent a distinct phylogenetic lineage within the species, as reflected by the consistent presence of a dorsal tip in their otolith morphology. On the other hand, COI barcoding data of A. stoliczkanus from Oman by Zarei, Masoumi, et al. (2023) detected only closely related haplotypes, separated by single mutational steps, between coastal and freshwater populations of this species.

4.5 Distinction of Aphaniops kruppi using otoliths

The otoliths of A. kruppi have not been previously examined in comparative studies. According to Teimori et al. (2022), A. kruppi is sister to the clade containing A. ginaonis, A. hormuzensis and A. stoliczkanus, suggesting that A. kruppi is also a relatively young species with an age dating back to the Late Pliocene–Early Pleistocene (3.2–2.0 MYA). Despite its young geological age, the otoliths of A. kruppi studied here can be distinguished from those of its congeners by a unique combination of characteristics, including the U-shaped excisura, short rostrum and weakly developed antirostrum (Figure 3m–p, Figure S1). Notably, otolith contour analysis (method 2) achieved minimal success in distinguishing between A. kruppi, A. hormuzensis and A. stoliczkanus (Table 6), likely attributed to the similar rounded shape of their otoliths, causing overlap and confusion. Conversely, the results of otolith morphometry (method 1) clearly reinforce that A. kruppi otoliths possess unique characteristics, with significant differences observed in three otolith variables (excisura angle, relative antirostrum height and relative antirostrum length) compared to all other studied species (Table 4). Remarkably, two of these variables, namely excisura angle and antirostrum height, are known to indicate differences between isolated populations rather than species (Reichenbacher et al., 2007). The significance of these variables in separating A. kruppi likely stems from the species' relatively young geological age.

Another interesting outcome was that otoliths from wild specimens of A. kruppi exhibit attenuated features compared to those from captive-bred specimens (see Figure 3m–p vs. Suppl. Figure S1, Table 3). These differences may be attributed to the distinct size difference between wild-captured (SL 29–32 mm) and captive-bred specimens (SL > 39 mm). Other reasons could be differences in water temperature, chemistry and food availability between the natural and the aquarium environment as such differences have been shown to influence otolith growth and morphology across multiple fish groups (e.g. D'Iglio et al., 2021; Gagliano & McCormick, 2004; Katayama & Isshiki, 2007; Lombarte & Lleonart, 1993; Mérigot et al., 2007; Tuset et al., 2003).

4.5.1 Comparison to the otoliths identified as A. kruppi in a previous study

Otoliths attributed to A. kruppi were described in Masoumi et al. (2024) based on samples from southern Oman (near Salalah, Mugsail region). In comparison to their results, the otoliths of A. kruppi studied here had a smoother and rounder outline, no dorsal tip and the rostrum and antirostrum of size class 1 otoliths were less prominent compared to similar sized specimens (size class II) in Masoumi et al. (2024). Also, the otoliths of A. kruppi of size class 3 of our study were quite different from the otoliths of similar sized specimens (size class IV) in Masoumi et al. (2024) in the characteristics mentioned above. On the other hand, the otoliths presented in Masoumi et al. (2024) appear somewhat similar to the otoliths of A. stoliczkanus from northern Oman and the United Arabian Emirates, with which they share the presence of a dorsal tip and a well-developed rostrum and antirostrum (see Reichenbacher, Feulner, & Schulz-Mirbach, 2009 [as Aphanius dispar]; Teimori, Jawad, et al., 2012 [as Aphanius dispar], Bidaye et al., 2023; Herbert Mainero et al., 2023).

According to Zarei, Masoumi, et al. (2023), A. kruppi and A. stoliczkanus are found in close proximity to each other in southern Oman (Zarei, Masoumi, et al., 2023: figure 2). In addition, COI data indicate that A. stoliczkanus from southern Oman represents a distinct “management unit” (Zarei, Masoumi, et al., 2023). The specimens identified as A. kruppi in Masoumi et al. (2024) could perhaps represent a mixture of A. kruppi, A. stoliczkanus and hybrids of the two. This would also explain why Masoumi et al. (2024) could not find species-specific traits in the otoliths of their sample, which is in contrast to the clear presence of such traits in the otoliths of A. kruppi used in our study. Additionally, Zarei, Masoumi, et al. (2023) noted that specimens morphologically identified as either A. kruppi or A. stoliczkanus can share mitochondrial haplotypes and interpreted this as indication of gene flow and introgressive hybridization between the two species in Oman. This corroborates the findings of Freyhof et al. (2017), who also suspected the occurrence of introgressive hybridization between A. stoliczkanus and A. kruppi within the Al-Hoota population (N Oman) and possibly across other populations. It underscores the necessity for further investigations to clarify the biogeography of A. kruppi and to accurately determine the extent of introgressive hybridization between the two species in the region.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Statistical analysis of otolith morphometric variables and shape indices proved more effective in species differentiation within Aphaniops compared to otolith shape analysis. However, the relatively small sample sizes relative to the numerous variables (wavelet coefficients) may have impacted the results of shape analysis; larger sample sizes could potentially enhance separation accuracy. Nevertheless, both methods revealed significant interspecific variability in the anterior part of Aphaniops otoliths and denoted the taxonomic value of otoliths for species identification. Our results also suggest the presence of a phylogenetic signal in otolith morphology, as evidenced by the more discernible otolith morphology observed in earlier diverged (geologically older) species, such as A. dispar.

An interesting aspect for future research is to investigate the drivers of the dorsal tip formation on otoliths, a feature that is either present or absent in otoliths of A. stoliczkanus, depending on the habitat. While most previous studies have suggested a link to habitat salinity, our findings suggest a genetic basis, possibly indicating a distinct lineage within A. stoliczkanus along the Gulf of Oman. However, this hypothesis requires further clarification.

In conclusion, our study underscores (i) the taxonomic significance of otolith characteristics for Aphaniops species differentiation and (ii) the necessity for further research to elucidate the extent of introgressive hybridization among sympatric Aphaniops species in the Middle East.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Jörg Freyhof (Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany) and Anton Weissenbacher (Zoo Vienna, Vienna, Austria) for providing the specimens of A. dispar and A. kruppi. We thank Neda Rahnamae (LMU Munich, Germany) and her family for transportation of specimens from Iran to Germany and vice versa. We are grateful to Erika Griesshaber (LMU, Germany) for technical assistance during SEM imaging and to Carolin Gut (Munich, Germany) and Reza Sadeghi (Shiraz University, Iran) for their help in the outline shape analysis. Finally, we thank Fatah Zarei and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments, which helped to improve our paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.