Safety study of 38 503 intravitreal ranibizumab injections performed mainly by physicians in training and nurses in a hospital setting

Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate and to compare the safety of intravitreal ranibizumab injections performed by physicians and nurses at a single large hospital clinic in Denmark during 5 years.

Design

Retrospective, interventional, non-comparative study.

Methods

Setting: All eyes that underwent a protocolized ranibizumab injection procedure performed in an operating room mainly by nurses and physicians in their first year of ophthalmology training. Study population: A total of 4623 eyes in 3679 patients with subretinal neovascularization secondary to a variety of retinal diseases, mainly neovascular AMD treated with intravitreal therapy (IVT) at the Glostrup Hospital from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2011 with a mean follow-up of 12.2 months (95% confidence interval: 11.9–12.6). Main outcome measures: Frequency of endophthalmitis, traumatic cataract, intraocular haemorrhage and retinal detachment from 2007 to 2012.

Results

Overall, 38 503 intravitreal ranibizumab injections were performed in 4623 eyes. Injections were performed by nurses (32.5%), ophthalmology residents (61.3%) and vitreoretinal surgeons (6.2%). Severe complications to treatment were observed in 17 eyes: Endophthalmitis (14 eyes, 0.36 ‰ of injections whereof seven cases were culture-positive), anterior uveitis (one eye, 0.026 ‰), traumatic cataract (one eye, 0.026 ‰) and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (one eye, 0.026 ‰). Retinal pigment epithelial tears were registered in 14 eyes in 14 subjects within the first year of treatment with ranibizumab. Of the 14 cases of endophthalmitis, seven occurred within a period of 5 weeks in 2010 when occasionally abnormal needle outflow resistance prompted the needle replacement in the operating room. No drug-related adverse events were recorded.

Conclusions

Intravitreal ranibizumab injection performed by nurses and physicians without preinjection topical antibiotics was associated with a rate of injection-related adverse events of 0.44 ‰.

Introduction

Intravitreal treatment with ranibizumab (Lucentis, Novartis, Basel) has been shown to improve visual outcome in subfoveal choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Rosenfeld et al. 2006; Brown et al. 2006). Off-label use in other types of CNV has also been reported (Ruiz-Moreno et al. 2013). The invasive nature of the procedure has prompted careful monitoring for a range of potential safety issues in randomized studies. When compared to a sham injection procedure or a sham procedure plus verteporfin photodynamic therapy, rates of culture-positive endophthalmitis up to 0.7% per injection have been reported (Brown et al. 2006). Comparable rates have been reported in studies where a clinical diagnosis of endophthalmitis was made without seeking confirmation by obtaining and culturing a vitreous tap (Brown et al. 2006). A large study of pegaptanib, another intravitreal inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in CNV in AMD found a relatively high rate of endophthalmitis of 1.3% per patient where a cluster of events were related to injection protocol violations (Gragoudas et al. 2004). Other potential complications that were systematically monitored included cataract, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, retinal pigment epithelial tear and vitreous haemorrhage (Brown et al. 2006; Comert et al. 2013).

In the following, we report adverse events recorded during the first 5 years after introduction of routine intravitreal ranibizumab therapy for CNV in AMD and other diseases of the posterior pole of the eye at a single large hospital clinic in Denmark.

Patients and methods

Inclusion criteria were having received at least one injection of ranibizumab for CNV of any aetiology, diabetic macular oedema, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central serous chorioretinopathy, branch retinal vein occlusion or central retinal vein occlusion at the Department of Ophthalmology, Glostrup Hospital (Denmark) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2011. Exclusion criteria were having received ranibizumab during vitrectomy or any other intraocular surgical procedure other than IVT and having received any intravitreal agent other than ranibizumab between the first ranibizumab injection and the conclusion of ranibizumab therapy or the conclusion of follow-up, whichever came first.

Study outcomes were incident cataract, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage, endophthalmitis (acute severe intraocular inflammation not confined to the anterior segment, classified as culture positive, culture negative or resolved without having undergone vitreous tapping or antibiotic therapy) and any other event deemed by the reviewing physician to be a potential complication of IVT. The survey did not register minor transient adverse events such as postoperative subconjunctival haemorrhage, ocular foreign body sensation, conjunctival hyperaemia, blurred vision, ptosis or floaters.

The injection procedure and perioperative procedures were standardized and protocolized from the first injection. Patients who had not previously received an intravitreal injection with a VEGF inhibitor were informed verbally and in writing about the procedure and its potential side-effects and complications. No topical antibiotic or mydriatic was administered before the injection. Patients were instructed to apply topical chloramphenicol eye drops three times per day postoperatively. Patients were instructed to contact the hospital if experiencing increasing pain or increasingly blurred vision after having left the hospital.

All intravitreal injections were made in operating rooms, by physicians in their first year of ophthalmology training and nurses, both of which had been trained for the purpose by vitreoretinal surgeons. Training included injections on an eye model and then 8–10 injections performed under direct supervision. Injections were given without direct supervision when due experience had been acquired. Injections were scheduled at 15-min interval. Before the injection, patients were seated in a waiting room where a nurse updated their history and checked patients for new unforeseen problems such as blepharitis, which would lead to the injection being postponed and patient being examined by a physician. Patients who co-operated poorly, had experienced complications, had significant concomitant eye disease such as infection, nystagmus, malformations, etc.) or significant generalized disease or disability (tremor, kyphosis, etc.) were injected by physicians. Specific attention was made to symptoms or signs of cutaneous, palpebral, conjunctival or corneal infection. Before injection, the injecting physician controlled the patient's chart to verify the indication for therapy, the choice of therapeutic agent, the laterality of the eye to be treated and the plan for postoperative follow-up.

The IVT was given with the patient in the recumbent position on an operating table. A nurse assistant applied a drop of oxybuprocaine 1% three times on the surface of the eye, after which the periocular skin was disinfected with a 5% solution of povidone iodine and the conjunctival sac was flushed with a 0.5% solution of povidon iodine. Then, the patient's face was covered with a sterile drape fitted with a central transparent adhesive plastic sheet. From the 27th of January 2007, ranibizumab was delivered in custom packages including syringes, needles and medicine. The injecting physician/nurse and assisting nurse wore facial masks and sterile gloves that were changed after each procedure. After incision of the plastic sheet covering the eye, a sterile lid speculum was used to separate the lids while keeping the lid margins and the eye lashes covered by the plastic sheet. The injecting physician or nurse, seated at the head end of the operating table and observing the operating field under a binocular microscope, instructed the patient to look towards the tip of his or her nose to expose the upper temporal quadrant. A pincet was used to gently displace the conjunctiva a short distance over the sclera before forcing the 30-gauge cannula through the sclera 3.5 mm posterior to the limbus while aiming towards the centre of the eye. After having inserted the needle to the hilt, 0.05 ml of ranibizumab solution was injected into the vitreous. The patient's right eye was injected using the right hand and the left eye by the left hand. After removing the needle, one drop of chloramphenicol was applied to the surface of the eye. No limbal paracentesis was performed after injections. After removal of the lid speculum and the drape, the patient rose and left the operating room. The patient was not seen again until 1 month after the injection, except in rare cases where incidents such as pain or significant intraocular hypertension had occurred during or immediately after the procedure. The patients were permitted to stay sometime in the waiting room after the injection. Intravitreal treatments in fellow eyes were made at least 1 week apart.

Results

The study included 4623 eyes in 3679 consecutive patients who underwent IVT for neovascular AMD (3205 patients), diabetic macular oedema (239 patients), proliferative diabetic retinopathy (nine patients), CNV associated with central serous chorioretinopathy (61 patients), branch retinal vein occlusion (67 patients), central retinal vein occlusion (55 patients), myopia-associated choroidal neovascularisation (39 patients) and uveitis with macular oedema (four patients). Of the 38 503 intravitreal injections of ranibizumab, 23 590 injections (61.3%) were performed by 58 physicians in ophthalmology training (mean: 407 injections per physician, range: 12–1990), 12 542 injections (32.5%) were performed by four nurses (mean: 3136 injections per nurse, range: 2718–3520) and 2371 (6.2%) were made by seven vitreoretinal (VR) surgeons or physicians specialized in ophthalmology (mean: 339 injections per VR surgeon, range: 7–565). Each year 6–10 physicians were trained to perform the injection procedure.

Of the 38 503 intravitreal injections of ranibizumab given in 4623 eyes over the 5-year period of observation, 14 (0.36 ‰) injections were followed by endophthalmitis, 1 (0.026 ‰) by anterior uveitis, 1 (0.026 ‰) by traumatic cataract, 1 (0.026 ‰) by vitreous haemorrhage and 1 (0.026 ‰) by rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Retinal pigment epithelial tears developed after 14 (0.36 ‰) injections. Of the 14 cases of endophthalmitis, seven were culture-positive (five Staphylococcus aureus, one Staphylococcus epidermidis, one Streptococcus pneumoniae). Seven cases were culture-negative. All presumed endophthalmitis cases were treated with intravitreal and intravenous antibiotics without awaiting the microbiology test response. Seven of the 14 endophthalmitis cases suffered substantial vision loss to a BCVA of 20 of 200 or worse in the affected eye. Of these patients, five were due to culture-positive endophthalmitis and they never regained the lost vision. No patient experienced bilateral severe adverse events. Treatment with ranibizumab was resumed in nine of the 14 cases believed to have a potential to improve vision, 10 of which had been injected by a physician in training and four by a nurse. After excluding the cluster of cannula-related endophthalmitis cases in 2010, no significant difference could be detected between endophthalmitis rates in nurses and physicians in training.

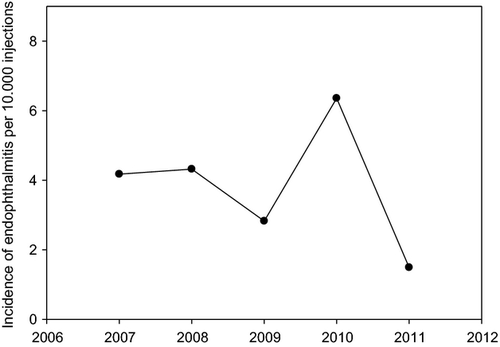

An overall decreasing trend in the endophthalmitis rate during the 5-year study period was interrupted in 2010 by a cluster (Fig. 1) of seven endophthalmitis cases (six culture negative and one culture positive) occurred within 5 weeks in 2010 during a short period when the need to apply unusual force during the IVT prompted the exchange of the custom package cannula with a comparable needle from another batch from the same manufacturer.

Discussion

This retrospective single-centre study of 38 503 ranibizumab injections found rates of endophthalmitis of 0.36 ‰ per injection and vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment both 0.026 ‰ per injection. With an average of 8.3 injections given per eye over a mean follow-up period of 12.2 months, this corresponds to an endophthalmitis rate of 0.38% per patient (the rate being 0.19% per patient if we only include culture-positive endophthalmitis). 10 and four of the endophthalmitis cases have been injected by physicians in training and nurses, respectively. The young residents performed with over 61% most of the injections (endophthalmitis rate 0.042 ‰), followed by nurses with nearly 33% (endophthalmitis rate 0.032 ‰). The amount of injections could be an explanation why no endophthalmitis occurred by injecting vitreoretinal surgeons (6.2% of the injections). Lasting severe visual loss to a BCVA of 20 of 200 or worse occurred in a majority of endophthalmitis cases.

Adverse event rates were low compared to controlled clinical trials, suggesting that the practice of using physicians in training and nurses to perform intravitreal injections is safe. Clearly, the results described here are not tied only to profession groups but also, and likely more significantly, to the specific training and injection procedures used at our institution. Rates of endophthalmitis in larger studies are between 0.02% and 1.3% (Gragoudas et al. 2004; Klein et al. 2009; Fintak et al. 2008; Pilli et al. 2008; Mezad-Koursh et al. 2010; Moshfeghi 2011; Mason et al. 2008; Diago et al. 2009). In a previous study from 2009 by Diago et al. (2009), the rate of endophthalmitis was 0.077% per injection. Of 1291 intravitreal injections, suspected bacterial endophthalmitis was reported in three cases. Two of the post injectional endophthalmitis cases were performed by residents in ophthalmology training and led to the conclusion that intravitreal injections performed by non-retina specialist physicians may be a risk factor for the development of endophthalmitis. In our study, the intravitreal injections were mainly performed by nurses and residents in a standardized procedure. Whether the standardization of the individual injection procedure steps were the key of success to achieve similar and even lower endophthalmitis rates as in most of the published studies remains unclear. We found a higher incidence of endophthalmitis in 2010 most likely due to a failure in the needles in the custom packages. Denmark was the first country that reported the incidents and from these reports, the needles were withdrawn from the custom packages. After excluding the cannula-related endophthalmitis cases in 2010, the incident rates of endophthalmitis were not higher in injections performed by nurses compared to physicians. On average, each nurse performed more than eight times as many injections as physicians and therefore achieved more routine in the injection procedure. Under a system where nurses only injected favourable cases, they achieved safety rates comparable to those of physicians in training. Simcock et al. (2014) reported recently similar findings in their study.

Other serious ocular adverse events like lens damage, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment after intravitreal anti-VEGF injection are reported in 0–0.8%, 0–5.4% and 0–0.7% respectively in larger studies (Diago et al. 2009; Nguyen et al. 2012; Campochiaro et al. 2010; Heier et al. 2012). Our data from a very large cohort are comparable to the sum of results from these controlled clinical trials.

In-theatre intravitreal injection procedure, as it was possible here in the setting of a large centralized institution in a metropolitan area, is associated with a 13-fold lower risk of endophthalmitis compared to in-office injections (Abell et al. 2012). Office injections may be a better option in rural areas where proximity to injection treatment facilities needs to be prioritized. It should be noted, however, that preoperative flushing of the conjunctival sac with povidone iodide is a thoroughly validated antiinfective procedure in eye surgery (Speaker & Menikoff 1991; Wykoff et al. 2011). Alternatively, topical polyhexanide seems to provide comparable antisepsis like povidon iodid (Ristau et al. 2014).

Our procedure did not include topical antibiotic treatment before the injection as it has been shown that conjunctival bacterial counts and postinjection endophthalmitis were not reduced more than with immediate preinjection antibiotics (Moss et al. 2009). It should be noted, though, that we systematically screened and treated for lid infection and lid inflammation before patients received IVT. Although there is no strong evidence for a prophylactic effect of routine postoperative use of antibiotic eye drops and two recent studies showed even a trend towards higher incidence of endophthalmitis using postinjection topical antibiotic drops, our patients did receive postoperative topical chloramphenicol (Bhatt et al. 2011; Storey et al. 2014).

Our results support that after systematic training and use of a standardized injection procedure in an operating room, physicians in training and nurses can perform intravitreal ranibizumab injections with a complication rate that is comparable with the best results from controlled clinical trials.