Running on Empty: Depletion and Social Reproduction in Myanmar and Sri Lanka

Abstract

A social reproduction framework that uses depletion reveals how multiple crises intersect. We deploy this framework to examine the relationship between depletion and conflict. Drawing on research undertaken in Myanmar and Sri Lanka in early 2020, we argue that the weight of social reproduction under conflict conditions increases women's depletion. Our findings showed, however, that increased depletion was not due primarily to increased social reproductive labour but because of the intervening effects of conflict and violence against women. These findings add utility to the concept of depletion. We argue that understanding the depth of depletion in conflict requires more than a mathematical calculation. We also contend that depletion of social reproductive resources is a tactic of conflict. Therefore, to understand depletion through social reproduction in conflict, we must expand the concept to include the depletion of social reproduction. Lastly, we show that violence against women is a significant factor in women's depletion.

Introduction

This epigraph comes from Chellakumary,1 a research participant in a study undertaken between 2019 and 2021 investigating social reproduction in conflict-affected environments. Chellakumary, a Tamil women in Sri Lanka's Northern Province, lost her lower leg in 2009 in the island's civil war. At the time of research, she was caring for two school-age children and was the household breadwinner, doing piecemeal daily labour. Her husband, also in poor physical health, was an alcoholic; it was hinted that these issues were partly caused by the war. Chellakumary had no disability support beyond a pair of crutches. Nearly 11 years after the end of the war, the household did not have running water and had to use a neighbour's well. It was clear the lack of basic infrastructure and the unequal gender division of household labour made her everyday social reproductive labours more time-consuming. However, Chellakumary emphasised how she used to do substantially more social reproductive (and productive) work every day. For her, the issues were not to do with the gender inequality and time-use of her social reproductive labour but directly because of the lack of support for her as a disabled woman grappling with the multiple, long-term individual and household effects of conflict and violence.All work is hard for me. Nothing is easy. If I had my leg, then it wouldn't be that hard. I got married when I was 18 and I was working and earning since then. I have always worked. I worked on the farms and when I came home, I did my work at home … But now, after the disability, my body gets sick all the time and I also think a lot and all of that causes more pain.

Chellakumary's experiences point to nuances in the conceptual and empirical connections between depletion, social reproduction, and conflict that are raised in this paper, which brings feminist political economy (FPE) into conversation with feminist conflict studies (FCS). Within FPE, the concept of “depletion through social reproduction” (DSR) was developed by Rai et al. (2014) to expose and measure the highly gendered, resource-draining effects of doing social reproductive labour. Social reproduction is the “hidden abode” of capitalism: unpaid and underpaid labour largely performed by women, and integral to capitalism's functioning (Fraser 2014). In Rai et al.'s framework, “depletion” is caused by a gap between inputs to social reproduction and social reproductive labour—the income earned, medical care received, educational support for children—and outflows from humans (typically women) and their bodies via the effort required to provide domestic, affective, and reproductive labour.

Given the feminist utility of the depletion framework in bringing to light the material effects of uncounted and undervalued labour on women, the study on which this paper is based set out to empirically investigate the costs of social reproduction, including depletion, in conflict-affected geographies, namely Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Extant feminist conflict scholarship explores how social reproduction shapes and is affected by war and conflict (e.g. Enloe 2000; Hedström 2020; Peterson 2009) and we seek to build on recent research strands that also examine depletion. Key within our findings is that, while increased gendered depletion connected to social reproduction in the most conflict-affected areas, the depletion observed and documented was not due to increased social reproductive work. The most conflict-affected women were not, largely, doing more social reproductive labour to compensate for a lack of social infrastructure and other social reproductive inflows. Rather, research participants had already exhausted their resources because of the multiple effects of conflict: they were already running on empty. Furthermore, in all sites, violence against women caused depletion. However, although this was enacted within the social reproductive sphere, we contend it is distinct from depletion though social reproductive labour.

Therefore, we argue the straight accounting measure of depletion as social reproductive inflows of support minus outflows of social reproductive labour is not sufficient to explain the depth and nature of depletion in a conflict or crisis context, where populations are already running on empty. That is, the sum total of “depletion” cannot be captured by only counting social reproductive inputs and outputs. Social reproductive loads have very different effects depending on the context. This is acknowledged by the feminist depletion framework (Rai et al. 2014), but we argue that it needs to be a more central analytical consideration.

The paper makes three contributions to feminist debates, which we propose can fruitfully build on the framework of depletion through social reproduction. First, in contexts where people are running on empty already, we need to understand and measure depletion as more than an accounting calculation. Second, we propose that we need to expand the definition of depletion, to include depletion as a deliberate tactic of conflict. The third area of consideration is how to analyse the relationship between violence against women (VAW) and depletion.

Understanding Hidden Labour Processes Using Depletion

The depleting effects of labour and the need for constant replacement (reproduction) because of “wear and tear” were noted in Capital, Volume 1 (Marx 1976; Vogel 2013). Engels, more concerned with women's labour and position, noted the effects of factory work specifically on women, as “physical and moral—[family] bond deformations, diseases, miscarriages, harder child births, fear of lost wages because of pregnancy” (Engels 2009:121; Vogel 2013). For Marx and Engels, though, despite the obviously depleting and gendered effects of labour under certain conditions, labour time and wages rather than the effects of work were the main measures of the human costs of labour. As such, the contemporary development of depletion as a measurement offers a more complete picture enabling an analysis of labour conditions and their effects.

The concept of depletion was developed by Rai et al. (2014:95–97) to better measure, examine, and account for the costs of doing social reproduction inside the home, the community, the state, and across the globe. Depletion through social reproduction (DSR) occurs when human resource outflows exceed resource inflows, as a result of “carrying out social reproductive work over a threshold of sustainability, making it harmful for those engaged” in it (Rai et al. 2014:88–89). Different from earlier measurements of social reproduction as comprising hours worked and converting that into a dollar value, Rai et al. (2014) propose a formulation where the resource available in any given society to sustain human wellbeing is the difference between inflows (medical care, education—termed “social infrastructure” by feminist economists [see e.g. Seguino 2019]—support networks, leisure) and outflows (time spent caring, domestic and community labour, biological reproduction) over time. The outflows within this calculation are those expended doing social reproduction, defined as the reproduction of social life. This includes biological reproduction, the unpaid production of goods and services in the home, social provisioning such as voluntary work to maintain communities, and the reproduction of culture and ideology (Hoskyns and Rai 2007). The labours of social reproduction thus consist in the variety of socially necessary work that provides the means to maintain and reproduce the population, including to “produce” the (often male) worker (Bhattacharya 2017; Laslett and Brenner 1989). Rai et al. (2014) connect their conceptualisation of depletion (that is, DSR) to environmental accounting that maps the costs of the gradual and substantive destruction of natural resources. However, they specify that different from that body of work, DSR is concerned with “the individual and collective costs of reduced welfare, natural and human resources through participating in SR” (Rai et al. 2014:95). The key focus of the DSR framework, then, is the harmful consequences of doing social reproductive labour, including caring activities. Rai et al. (2014:97) advocate measuring these consequences through feminist methodologies that foreground time-use, especially time spent doing unpaid SR work; examining the household as a site of SR; and taking into account the role of community networks and community voluntary work. Earlier analysis also highlighted how depletion manifests asymmetrically across the global South and global North, with international political economy shifts including the globalisation of production/social reproduction driving this unevenness (Hoskyns and Rai 2007).

DSR serves the ongoing feminist task of drawing attention to the significance of the social reproductive sphere as a core contributor to economic development. As Fraser (2014) pointed out, we can only understand the “hidden abodes” of capitalist production when we also explore their background conditions of possibility; that is, the labours and dynamics of social reproduction.

In theorising the costs of social reproduction, the depletion framework speaks to questions about the inputs needed for capitalist relations to function, which feed into ongoing Marxist-feminist debates on social reproductive labour and the generation of value (Elson 1979; Mezzadri 2019, 2021). Depletion is well-suited to bridging feminist political economy debates on the interrelations of production and social reproduction within the capitalist system. Rather than focusing on the spatial and economic specificities of a discrete work site such as a factory, the focus of the measurement is on inflows and outflows of resources, and both time-use and labour conditions are included in the calculation. The depletion framework is better attuned to the empirical realities of “life's work” (Mitchell et al. 2003), which for vast numbers of the world's women demands their engagement in both production and social reproduction (Meehan and Strauss 2015; Waring 1989). Especially in highly precarious labour regimes, reproduction can only be sustained through multiple forms of work, entangled together in the everyday: social reproductive care of family members, casual waged work, small-scale and subsistence farming, and income-generating activities (Stevano 2018, 2019). Examining depletion urges our attention towards the impacts of these labour regimes at multiple levels: upon the individual, household, community, and beyond. Keeping both production and reproduction in the frame, Gunawardana (2016) analyses the interaction of global markets and social reproduction in a section of Sri Lanka, arguing that both factory export processing zones (EPZs) and households are sites of depletion for women. Women come to work in the factories because social reproductive resources “at home” are depleted and factory work offers a relatively stable source of employment. However, women are then also depleted by neoliberal drives for workforce efficiency: wages and leisure time are insufficient and existing patriarchal relations are reproduced within the factory's worker/management hierarchy. In the latest neoliberal era, multiple crises of production and reproduction, driven by predatory debt systems and the COVID-19 pandemic, stack up to intensify gendered depletion through social reproduction (Brickell et al. 2020).

As well as taking time-use into account as a resource outflow, the depletion framework is sensitive to the varying temporal dimensions and impacts of social reproduction. In the feminist political economy of everyday life, it can be used to analyse not only the daily but also the intergenerational effects of neoliberal development policy on women's bodies and women collectively (Elias and Rai 2015). The temporalities implied by the term “depletion”—rather than “destruction” or “damage”—are those whereby harm accrues over time when social reproduction is unsupported; whereby human capabilities are eroded through gradual, incremental processes rather than necessarily or only via discrete or visible events. The non/malrecognition of social reproductive work that drives such depletion is a form of gendered (structural and everyday) violence, as are the bodily impacts of inadequate access to social reproductive resources such as healthcare and nutrition (Elias and Rai 2019). The conceptual connection made to gendered violence resonates with calls by FCS scholars to look beyond war and (re)focus attention on the many forms of violence against women that occur during “peacetime” (True 2012:6, in Elias and Rai 2019:214). It raises the question of the relationship between depletion and violence and opens the door to investigating how depletion through social reproduction manifests and is experienced in conflict-affected contexts.

Depletion and Social Reproduction in Conflict

Feminist conflict scholarship analyses the multifaceted, spatial, and temporal dimensions of violence. In regard to its multifaceted nature, violence cannot be understood in terms of its physicality alone (Elias and Rai 2015; Hedström 2021). On spatial dynamics, studies of war and conflict show the connections between “war front” and “home front” violence (Brickell 2020; Enloe 2000). On the temporal continuum, physical and sexual violence against women (VAW) often continue and worsen after war (Cockburn 2004; Davies et al. 2016; Enloe 2002). Moreover, conflict-specific dynamics of VAW include “post-war gender backlashes” that are likely to manifest within and through the social reproductive sphere (Pankhurst 2007). On social reproduction, women's (economic) insecurity can become entrenched “post-war”. They are more likely to be driven into illicit or shadow economy work, and work to just “cope”, as they simultaneously undertake the social reproductive work that keeps households functioning (Peterson 2009).

The growing literature on depletion and war points to the relevance of the DSR framework in explaining gendered dynamics of conflict and, especially, post-war reconstruction. We engage with and seek to contribute to two—overlapping—strands of this research. Broadly, the first strand analyses how women's depletion is caused by gender inequalities in post-war transitions and processes of reconstruction. These gender-unequal socio-economic and political structures exacerbate women's already existing conflict-related insecurities. For example, Hedström and Olivius (2020) show how the nature of the post-war development process in Myanmar that focuses on production means that women cannot benefit from paid economic opportunities because they are carrying a disproportionate (unpaid) social reproductive load. Such studies connect individual DSR to national economic trajectories, which in turn are shaped by global neoliberal imperatives. The public health implications of neoliberal development in the wake of conflict and crisis are deeply gendered; there is a mutually reinforcing process of disempowerment. The failure to support and enable access to healthcare in conflict-affected contexts entrenches the bodily depletion of women and girls affected by sexual and gender-based violence (Tanyag 2018). Depletion through social reproductive labour is exacerbated by continuing VAW and economic insecurity, perpetuated by the unequal gender power relations that inhere in processes of neoliberal state-/“peace-“building (Hedström 2021). These continuities raise significant questions about the meanings of “peace” and “justice” following war (Davies and True 2017; True 2012). They also raise important questions about the relationship between DSR and VAW, to which our paper seeks to add some clarity, whilst recognising the intricacies. Meanwhile, the post-war capitalist economy harnesses women's unpaid social reproductive labours to power economic growth.

The lack of support for social reproduction in “peace”/post-war development processes is “not an innocent omission, but a violent one” (Hedström 2021:384). This gender inequality, which drives depletion, is an example of the structural violence of non/malrecognition of social reproductive labour (Elias and Rai 2019).

The second strand of research argues for understanding depletion in conflict not only through the lens of the gender inequalities wrought by global capitalism but also through analysis of domestic political economy settlements. These settlements may drive the depletion of subordinate/“loser” social groups’ reproductive resources and capacities. The nature of the state demands examination: there is, for example, a “complex relationship between the postcolonial state, violence and gendered processes of reconstruction” (Martin de Almagro and Ryan 2019:1074). Relations between productive and social reproductive economic spheres need to be unpacked, but so too do racialised social relations (ibid.). Processes of accumulation and associated dispossession that unfold in and after war urge questions about who is benefiting from conflict, at whose expense (Hedström and Olivius 2020; Sarma et al. 2023). We propose that the DSR framework, which focuses on depletion through social reproductive labour, can address these matters by considering more centrally the depletion of social reproductive resources. This paper, drawing on fieldwork in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, examines depletion through social reproductive labour as per the formulation of the DSR framework (Rai et al. 2014), but it identifies the significant role that the deliberate depletion of social reproductive resources plays in the lives of conflict-affected populations. Both countries researched in this paper belong to a growing number of contemporary examples of post-war/ceasefire reconstruction processes managed by national elites, via the state. The reconstruction processes include some but actively exclude and marginalise others (de Oliveira 2011) and states act in consort with international capital to accumulate by dispossessing subordinated groups (Woods 2011). That is, states themselves can be agents of depletion.

Geopolitics can come to bear, violently and unevenly, on capacities to socially reproduce (Brickell 2014; Fernandez 2018). Different geopolitical contexts shape states’ positionings vis-à-vis social reproduction and depletion. Chilmeran and Pratt (2019) analyse differences between gendered depletion and the shaping of social reproduction in two contemporary conflict-affected environments, Iraq and Palestine. The roles of the Iraqi and Israeli states are crucial in both contexts but are shaped by their divergent historical and geopolitical trajectories. While the Iraqi postcolonial state intervenes to control and manage the social reproduction of Iraqi citizens in the service of postcolonial state formation, Israel, a settler-colonial state, targets Palestinian social reproduction with the core objective of erasing Palestinian life (Chilmeran and Pratt 2019:587). The contrast is that in Iraq, state violence, war, and conflict exacerbate the depletion of Iraqi citizens, but in Palestine, the undermining of social reproduction and subsequent depletion of Palestinian citizens “is not merely an effect of conflict and violence but is integral to the logics of Israeli settler colonialism” (ibid.). In summary: states intervene differently in processes of social reproduction for specific populations, according to their own geo-territorial objectives. As this paper will show, the implications for depletion vary for differentially conflict-affected populations, even within the same country.

“Depletion”, then, is a valuable framework to examine and measure the costs of social reproduction. The DSR framework (Rai et al. 2014) is unique in its attention to the temporal dimensions of social reproductive labour and harms. However, the straight account of depletion as consisting of social reproductive inflows of support minus outflows of social reproductive labour may not be sufficient to explain the nature and depth of depletion under certain conditions. Existing research raises questions about the relation of conflict conditions to depletion when social reproductive resources are deliberately under attack. Finally, while depletion scholars identify structural violence is a causal factor, and FCS scholars highlight the relationship between depletion and VAW, further investigations are needed to unpack the relationship between depletion and violence.

Using Feminist Methods to Investigate Depletion in Conflict-Affected Geographies

The two countries where research was undertaken, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, are both conflict-affected, with relative similarity on a number of variables. Both are Buddhist majority countries, with postcolonial histories of violent majoritarian states, ethnonationalist conflict, and separatist struggles for self-determination. The sites, scale, and intensity of those conflicts have varied over time in both countries. In Myanmar, Kachin, Shan, Mon, and Karen ethnic groups, as well as communist groups, have resisted the state through separatist movements and insurgencies. In Sri Lanka, Tamil demands for self-government from the 1970s escalated into civil war between the state and mainly the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) from 1983 to 2009; the state also fought Marxist youth insurrections in the rural south. In both countries, increasingly muscular state ethnonationalism and Buddhist violent extremism targets Muslim populations. Both states have been characterised by heavy and changing degrees of militarisation over the last decades and beset by political and economic crises in the past two years.

The fieldwork was carried out between January and early March 2020, just before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic and lockdowns began. In Sri Lanka, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, Defence Secretary at the brutal end in 2009 of the country's civil war, had won the Presidential election two months earlier, generating much fear among Tamil citizens. In Myanmar, civil–military tensions simmered but the military coup of February 2021 was yet to take place. Thus, fieldwork timings meant researchers were working within significant political and social currents and able to observe and document the everyday impacts of these upon already conflict-affected populations.

Research was undertaken with 19 adult women in households in six sites across the two countries.2 The six sites were chosen in relation to their exposure to conflict on a scale from “directly conflict-affected”, to “proximate to conflict”, to “relatively stable” (see Table 1). While recognising the limitations of these categorisations, doing the research in differently conflict-affected geographies enabled examination of the effects of conflict and violence in relation to depletion and social reproduction. In both countries, people in the “directly conflict-affected” and “proximate to conflict” sites were from defeated or subordinated social groups. Those in “relatively stable” areas were from majority social groups and considered their place to be peaceful, despite heavy militarisation or violence against women. In “proximate to conflict” sites, participants were less recently or immediately war-affected; here, though, the limitations of this categorisation were more evident. For example, one “proximate to conflict” participant in Sri Lanka had, years earlier, suffered the murder of multiple family members and the abduction and torture of her husband; in ontological reality, she was directly conflict-affected.

| Country | Myanmar | Sri Lanka | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximity to conflict | Site 1: Directly Conflict-Affected | Site 2: Proximate to Conflict | Site 3: Relatively Stable | Site 1: Directly Conflict-Affected | Site 2: Proximate to Conflict | Site 3: Relatively Stable |

| Location | Kachin State, Myitkyina, IDP Camp | Kachin State, Town of Namti (Grey Zone) | Mon State, Mawlamyine, Paung Township | Kilinochchi District, Northern Province | Batticaloa District, Eastern Province | Anuradhapura District, North-Central Province |

Researchers used the Feminist Everyday Observatory Tool (FEOT), a three-step method that brings together in-person observation and ethnographic time-use data gathering and analysis (Rai and True 2020). First, in a 30-minute pre-observation meeting, the researcher gathers key demographic information about the research participant. Second, during a day of observation, the researcher shadows the participant, ideally from when she gets up until she goes to bed, to understand her time-use and everyday activities. The researcher records in a journal the participant's activities every 15 minutes for the full day and notes their own observations about the context and modalities of time-use. The observational method is preferable to a self-competed time-use survey because the researcher can record how multiple labours of social reproduction and production are typically being undertaken at any one time (Drago and Stewart 2010; Rai and True 2020). Third, there is a 1.5–2-hour post-observation in-depth interview. In it, researcher and participant discuss significant aspects of the observation day and the wider environment.

The qualitative and observational nature of this method and its multi-dimensional approach to data collection enabled us to refine the meaning of DSR. We focused on what social reproductive work was being done, by whom, and with what available resources. Additionally, the FEOT method generated data on people's subjective realities, histories of violence and conflict, and how these shaped depletion in the present day. We could observe and reflect upon the complex ways in which individual experiences were embedded in household and community lives. Furthermore, it was possible to discuss with participants interconnections between individual depletion and depletion of households and whole communities. With these multi-sited and multi-levelled analyses, we were able to identify patterns in the relations between depletion, social reproduction, and conflict.

The FEOT allowed us as researchers to partially experience, in real time, the depleting (draining; monotonous) effects of everyday social reproductive work as well as the material and psychological demands of these labours in a conflict-affected environment. This does, simultaneously, highlight the method's limitations: the mental-health burden upon researchers of long workdays and in such environments is not insignificant. This is especially so for more precariously positioned local research assistants and therefore the FEOT risks exacerbating the well-documented uneven power dynamics of fieldwork (Cronin-Furman and Lake 2018). In both countries, we worked closely with in-country research organisations and their expertise was crucial for establishing contact and building trust with participants, and for managing security risks in politically sensitive environments. As researchers from global North institutions, we sought to remunerate research assistants as fairly as possible but remain conscious that the post-fieldwork mental-health needs of local research assistants are rarely recognised or supported. On this, we propose that the FEOT method builds in steps to ethically manage the “exit from the field”, for all researchers and participants.

Conflict as a Force Depleting Social Reproduction

Three interlinked empirical analyses illustrate our core argument that DSR—especially depletion in conflict—needs to be conceptualised as consisting of more than a straight calculation of social reproductive resource inflows minus outflows. First, we propose that conflict increases depletion, but this is not necessarily because the conflict environment increases the quantity of social reproductive work. Second, the deliberate depletion of social reproduction under conditions of conflict is a major causal factor, exacerbating depletion in the social reproductive sphere. Third, depletion is caused by conflict-related violence against women.

Conflict Increases the Intensity of Depletion

In the directly conflict-affected locations in both Myanmar and Sri Lanka, conflict and the long effects of conflict were amplifying the effects of depletion. However, for the research participants, this was not due to increases in the volume of social reproductive work; increased depletion was not caused by increases in the hours spent doing social reproductive labour. In fact, in some cases, time spent doing social reproduction was less because of the conflict context. For example, in the directly conflict-affected site in Myanmar, a camp for internally displaced persons (IDP) in Kachin State, research participants were not able to do the same amount of social reproductive activities as they would in their homes due to the lack of resources, infrastructure, and kin networks. In Sri Lanka, the civil war had officially ended nearly 11 years earlier but research participants in the directly conflicted-affected location of Kilinochchi District in the Northern Province still lacked safe, secure land and homes with basic resources. Kin and community relations remained fractured and distanced due to conflict; research participants were socially and geographically isolated. They were undertaking social reproductive labours alongside productive work but were doing so under unsupported conditions. Having to rebuild life under these conditions, with allegations of war crimes and disappearances unaddressed and in the wake of the immense brutality of the war's end, added extra intensity to these everyday labours. These conditions were distinct from those of participants in relatively stable sites. There, depletion through social reproduction was also documented and participants undertook multiple social reproductive and productive tasks over long hours, such as childcare for extended family, cooking for extended family, tending sizeable homes and land. For some, such as the widow of a state military officer killed in action, the brutality of the war still loomed large. However, participants had better resources—land, houses, kin networks in close proximity—to mitigate against depletion.

In the most conflict-affected sites, then, it was conflict and its enduring effects that increased the intensity of women's depletion rather than increased hours spent carrying out social reproduction.

The lack of basic infrastructure undermined social reproduction, contributing to women's depletion. Take the example of the IDP camp in Myitkyina. Research participant Hpaure Ong3 was the de facto head of household; her husband was away fighting with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). She explained that she was exhausted because the whole family—herself, four children, and her mother-in-law who was disabled—had to live in one room. At night, she was constantly woken up by one of the children or her mother-in-law; “all she wanted” was an extra room to sleep in.4

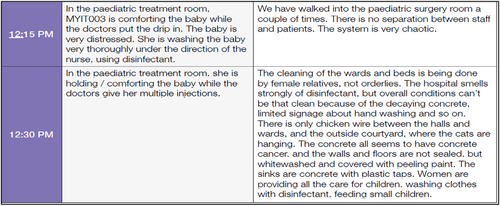

Depletion was intensified in this site by the paucity of social infrastructure, most notably health and medical services. During one observation day, the research participant's one-year-old child became very unwell. The observational time-use diary (Figure 1) documents what happened, including the emergency visit to the under-resourced camp hospital:

The rest of day's diary documents how the depletion experienced by Kwangtse, the baby's mother and research participant, was not driven by having to care for longer hours or having to undertake a greater amount of care for her sick child. Rather, the conflict environment and lack of safe and accessible healthcare infrastructure were threatening her baby's life, and this was the cause of her extreme psychological depletion.

That said, the short time-use diary extract above does indicate that women, generally, were compensating for the lack of basic medical services at the hospital with additional social reproductive labour. These were not the study's research participants, so this was a general observation rather than through systematic documenting of time-use with the FEOT method. This adds nuance to the FEOT's findings: while Kwangtse's individual depletion was not caused by additional care work, observation of the broader context during the day suggested that conflict was likely causing more care work, which was collectively falling to women. The scope of the study and this paper do not permit in-depth consideration of how depletion at these different scales—in this instance, at individual and community levels—were interacting. However, with connections drawn in the existing conflict literature, these will be important to trace in future studies.

He came home once in a while when he got leave, and I did all the work at home anyway … But when he was here, the dynamics were different. We were happy. That is the part we miss now, but everything else is kind of the same.5

Further data from this site in Sri Lanka illustrate how depletion through social reproduction was caused by enduring conditions of conflict. Returning to the participant quoted at the start of the paper: Chellakumary was living with injuries caused by war, suffering alcoholism and violence within the home, and undertaking both productive and social reproductive labour for the household without basic physical infrastructure. One of the study's hypotheses was that war causes injuries and women are more likely to undertake additional social reproductive work to support injured family members, further driving their depletion. Given the study's small research sample size, we cannot discount the possibility that this was happening in other households. For Chellakumary, though, there was no additional resource, of any gender, to deplete through additional social reproductive labour: the household was already running on empty. In fact, in the post-observation interview, she spoke with sadness about not being able to do as much work as she had in the past because of the lack of support for her as a disabled person; and of worrying more now, because of the multiple, ongoing effects of conflict within her home and the community. In this instance, at least, conflict was a more direct source of depletion than DSR.

In the relatively stable site in Sri Lanka, community workers and activists emphasised the need there, too, for better support for disabled people and for mental-health issues. Such needs were especially prevalent in state military households.6 However, as the next sub-section discusses, at least some replenishment was provided by the state for these citizens, unlike in the conflict-affected site.

Depletion as a Tactic of Conflict (or, Depletion of Social Reproduction)

The DSR analytical framework concentrates upon the ways that people, especially women, experience depletion as a result of doing social reproductive work without adequate support or replenishment. That is, the focus is on depletion through social reproduction. We argue, however, that this framework needs to also include how depletion is caused, and is gendered, when social reproduction itself is under attack.

This is especially relevant in contexts of conflict. In Myanmar and Sri Lanka, there was deliberate depletion by aggressors of the social reproductive resources and capabilities of marginalised social groups. As women are disproportionately engaged in the social reproductive sphere, this, correspondingly, drove their human depletion. In the directly conflict-affected geographies in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, social reproductive resources were depleted as a purposeful tactic of war and ongoing conflict, to subdue and control certain populations. This was notable as a strategy of the ethnonationalist state in both countries; operationalised through state security forces, that is, militaries, against social groups that contested their authority. In our case studies, these subordinated groups were the Kachin population in Kachin State (Myanmar) and the Tamil population in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka. As women are disproportionately engaged in the social reproductive sphere, such deliberate depletion of social reproduction impacted them.

In the former war territories in Sri Lanka, the military tracked women searching for missing family members and harassed them at checkpoints as they passed through to collect children from tuition after dark.I fear that we might meet Burmese soldiers in the jungle while collecting firewood. I fear because I am a woman. We do not have the strength to respond back when things happen.8

Recently, every time I pick my son up from the main road, there are about 25 military men with a temporary sentry point. They check the handbags, jackets, and vehicle. They were there for two or three days continuously … I am worried to take my children to tuition; I even worry if they are targeting me.9

Depletion of household financial resources occurred to distressing levels in conflict-affected sites. Take Ah Kyi, a research participant in the IDP camp in Myanmar. She compared her current life in the camp with her previous life of subsistence cultivation and hunting. Since displacement, food was “used up more quickly” and they “have to borrow from others”. The result of this constant financial depletion was chronic stress about the very basics of social reproduction: “about rice” and “about the next meal”.10

There was a women's programme I attended in Mullaitivu [former LTTE territory]. There, I learned that the wives of the departed [state] military men will receive pension for the rest of their lives. But here, there is not even one such scheme for women who have lost their husbands. We asked them why there isn't such support for them, like for wives of [state] military men. They said these are two different things.11

She talked at length, very disoriented, about her disappeared son, almost immediately from the start of the meeting. Every point that came up, she made it about her disappeared son. She was disoriented, lacking details, e.g. confused about dates. She talked only about her disappeared son, not the children who were still alive. The RA said she sees this with many women protesting for disappeared.12

In fact, against this backdrop of the depletion of social reproduction, being able to carry out social reproductive labour as normal—safely, within the home, on one's own land—was desirable and a relief for some. For example, researcher notes from the time-use diary on the observation day with Benita document how she seemed much calmer and more grounded as she carried out everyday social reproductive tasks such as subsistence farming and cooking. The routine rhythms of social reproductive labour can represent familiarity and security, which are absent in displacement or when navigating the traumas of conflict in particular times and spaces.

The data presented here, of everyday depletion of social reproductive capacities and resources, represent continuities in deliberate state strategies to disrupt and damage social reproduction. In both Sri Lanka and Myanmar, ethnonationalist state forces have, over several decades, attacked and sought to destroy the social reproduction of subordinated social groups in contested territorial spaces. People have been displaced from their land and homes and prevented from having access to the means of production and social reproduction. The Tatmadaw developed and deployed the “Four Cuts” from the early 1960s—a strategy to crush ethnic insurgency by “cutting off” insurgents’ access to food, recruits, funds, and intelligence (see Smith 1999). At the height of conflict, state militaries stand accused of war crimes, including in Sri Lanka mass sexual violence against the Tamil population, especially in the final months of the civil war in 2008/2009 (see UN Panel of Experts 2011). The everyday spatial insecurities and ever-present threats of violence from the same military forces represent continuities of the same deliberate strategy of depletion of social reproduction, with the consequence of gendered depletion through and within the social reproductive sphere.

Meanwhile, in the relatively stable sites in both countries (as defined in the methodology section earlier), where the political conditions and social infrastructure are more supportive, there was more evidence of depletion through social reproduction due to the gender division of labour and women's double burden of labour. However, the relative stability of the political environment allowed for some mitigation and replenishment, which were not available to participants in the other locations. For example, some participants individually engaged in creative activities such as music or embroidery to mitigate against the effects of depletion. Others took pride in their work activities; felt emotionally replenished by love and contact with kin networks; were financially and emotionally replenished by the state, to which they felt connected.13

Violence Against Women is a Major Driver of Depletion

The third key finding is that violence against women (VAW) drives physical and mental depletion. VAW was present across all sites in both countries, in various forms and at various intensities. It happened within and through the social reproductive sphere, meaning the findings concur with the feminist conflict literature that there are complex connections between violence and social reproductive depletion.

Violence was disclosed by gatekeepers such as community health workers, and participants, often in post-observation interviews after researchers had observed participants’ depletion and stress during the observation day. Violence was perpetrated by state agents (military) and also happened within the household, typically intimate partner violence (IPV). Military violence as a deliberate tactic, by the state, to deplete the social reproduction of subordinated social groups was discussed in the previous sub-section. Meanwhile, the household, where much social reproduction occurs, was also a site of physical, sexual, and psychological violence. This was not universally the case, of course, but it was notable that domestic violence was present across all six sites, regardless of proximity to conflict. That being so, in the most conflict-affected sites in both countries, women were more vulnerable to both state and household violence as they carried out social reproduction.

Violence took multiple forms. In the relatively stable site in Sri Lanka, research participant Lakmini had married from poverty into a military household and experienced violence, mostly from her in-laws. One of the accusations was that she didn't do the household work properly; she was judged not to work hard enough, care well enough for her family, or uphold the cultural values of the strong Sri Lankan nation. Lakmini was physically drained and mentally always anxious because of the ongoing psychological abuse, vividly describing the impact: “I'm decaying.”14 In this instance, violence and depletion are imbricated: the familial violence Lakmini was suffering caused depletion on its own terms but also directly drove DSR as she felt compelled to exhaust herself further through domestic labour in order to satisfy her in-laws.

Nonetheless, we analytically distinguish the two concepts of violence and depletion because for other research participants, we observed a pattern whereby the cause of increased depletion was violence itself and not social reproductive labour that is the key concern of the DSR framework.

Here, IPV caused depletion through physical and psychological damage and exhaustion. It led to additional burdens of biological reproduction which we can reason were very likely to cause DSR. However, Lahpai's depletion as documented through the FEOT and triangulated through supplementary interviews, was because of IPV.Lahpai is a tough case. Poor woman. Her husband beats her and rapes her, that's why she has so many kids. Before the birth of her last child, Lahpai hid the pregnancy from the nurse … She was ashamed, and afraid of her husband. The nurse had arranged [with Lahpai's consent] for someone to adopt the baby [knowing Lahpai was exhausted] but the husband refused.15

Nazia experienced lost sleep and extreme anxiety and stress, leading to further physical impacts including high blood pressure. She described how violence and care demands would collide at night in bed: her husband, on one side, would pull on her demanding sex, and her young son, on her other side, would wake up and pull on her too, causing further anger from her husband. We contend that the sex Nazia was forced into and depleted by was not additional social reproductive labour but violence in and of itself. We recognise there are different analytical and political positions feminists take on this, but we argue for the need to distinguish depletion due to social reproductive labour from depletion due to gender-based violence.I have to attend to my husband. He expects me to sleep with him … If he is at home, then he wants me to sleep with him every day. If I say no, he says very harsh things, it hurts me … Even if I fall asleep accidentally sometimes, he wakes me up. So, I try to satisfy him, but he never stops even when I have my period or am sick. I cannot explain how I feel when he does that, I don't know if it is right or wrong. He doesn't consider how I feel, my feelings don't count. He forces me most of the time.16

In these findings, physical, sexual, and psychological violence, coercive control, and the threat of violence drive depletion. The empirical data record the depleting effects of this violence and demonstrate that depletion was not caused by an increase in social reproductive work or increased intensity of social reproduction.

That being the case, the data show how VAW was enacted within and through the social reproductive sphere. The framework of depletion has purchase because it enables us to bring both phenomena—social reproductive labour and VAW—together in analysis. The concept of “depletion” allows analytical incorporation of how damage occurs over time, incrementally, and even long after the obvious or visible instances of violence. For example, in the post-observation interview, Nazia described how, “weirdly”, she felt worse psychological effects now than before, even though the violent situation was “a bit better now”; her depletion was greater, she thought, because she had started to reflect on everything.17

Running on Empty: Conclusion

“Depletion through social reproduction” enables analysis of gendered depletion through work in important ways. The counting of social reproductive inflows of support and outflows of labour valorises the unpaid domestic work that women are expected to perform even when exhausted and “decaying”, as in Sri Lanka. It recognises the significance of social infrastructure that was so deficient in the Myanmar IDP camp when a baby needed urgent hospital treatment. Our study's feminist methods exposed the extra weight of social reproductive labour as women undertake multiple tasks simultaneously and demonstrated the importance of measuring time-use as a social reproductive outflow that contributes to depletion.

Our data show, though, that to understand and measure depletion, we need to analyse it as more than a mathematical calculation. The straight measure of social reproductive inflows of support minus outflows of labour was not sufficient to understand the nature and depth of depletion in conflict-affected Myanmar and Sri Lanka, where people were exhausted of resources and already running on empty. The heightened levels of depletion among the most conflict-affected women connected to social reproduction but were not caused by countable increases in social reproductive labour or the lack of social infrastructure. Rather, the conflict context itself intensified depletion. Participants lacked the most basic infrastructure, such as access to their own water supply or a decent room to sleep in. Participants were depleted by the immense weight of continuing everyday life while displaced from their homes and caring for young children and vulnerable family members; and rebuilding everyday life while still grappling with unresolved, deeply traumatic wartime issues such as disappeared family members. The sum total of depletion could not be captured by only counting social reproductive inputs and outputs; the conflict context needs to be a much more central consideration in the analysis.

Depletion was also an enduring tactic of conflict. In both case study countries, states deliberately depleted and failed to support the social reproduction of former or current “insurgent” populations. Military violence and harassment obstructed women's everyday social reproductive work. Financial resources for households’ social reproduction were depleted to distressing levels. The brutality of war crimes remained unaddressed, and this political backdrop perpetuated psychological depletion of the most conflict-affected individuals, households, and communities. Social reproduction was undermined to the extent that for some, it was simply not possible to do as much of it; for others, when it was possible to undertake routinely and unencumbered, the work was experienced as a relief. In conflict contexts, then, depletion occurs through the social reproductive sphere but rather than only depletion through social reproduction, it is the deliberate depletion of social reproduction. We propose that the DSR framework is expanded to include this.

Finally, violence against women (VAW) was present across all research sites in both countries and was a significant driver of depletion. Violence related to different kinds of social reproductive labour but the two categories of social reproductive labour and VAW were distinct. We would not describe the relentless, forced biological reproduction experienced by one research participant and ongoing rape in marriage experienced by another as social reproductive labour but as gender-based violence, itself causative of depletion. The concept of depletion through social reproduction was valuable, though, because it enabled the two issues of social reproduction and VAW to be understood as distinct but brought together in analysis of their effects. It also allowed us to better capture the temporal dimensions of such violence, through recognition of how damage occurs over time, incrementally and at different times from visible or overt instances of violence. Depletion through VAW may be especially under-recognised in conflict contexts because of the tendency to focus on visible fighting and time-specific instances of physical violence.

Recognising the utility of the depletion framework in bringing to light the material effects of undervalued labour on women, this paper has proposed three ways to fruitfully build on it. It is hoped that the findings and analysis will enhance feminist political economy understandings of depletion in conflict and other contexts where people are already running on empty.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Monash-Warwick Alliance Accelerator Grant (2019-21). We are grateful to Shirin Rai and Jacqui True, Principal Investigators on the grant, for their intellectual input and mentorship throughout and beyond our time working on the study. Many thanks to Special Issue guest editors Vincent Guermond, Nithya Natarajan and Katherine Brickell for working with us so supportively on this manuscript; and to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We are indebted to those in Myanmar and Sri Lanka who worked with us on the research. Especial thanks to Hkawng Yang, Gam Aung, Ja Htoi Ban, Danseng Lawn and Zin Mar Phyo in Myanmar and to Anushani Alagarajah, Sandun Thudugala, Sakuntala Kadirgamar, Uda Deshapriya, Natasha Vanhoff, and an independent feminist researcher, in Sri Lanka. Our deepest thanks go to the women in Myanmar and Sri Lanka who gave their time, knowledge and insights, through participation in the study. We hope this paper accurately reflects and does justice to what was shared with us. All shortcomings in the paper are of course our own.