A qualitative evaluation of rural and provincial surgery wānanga to enhance cultural safety among surgical registrars in Taranaki, New Zealand

Abstract

Background

The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) recently instituted cultural safety and cultural competency as its 10th competency with formalized cultural safety training yet to be instituted. Wānanga are Indigenous Māori teaching institutions that can be used contemporarily for cultural safety training.

Methods

In 2022, surgical registrars based at Taranaki Base Hospital (TBH) held in-hospital wānanga ranging from 1 to 3 h focussed on cultural safety, professionalism and wellbeing. This study explores the perspectives of these registrars who attended wānanga using a Kaupapa Māori aligned methodological stance and interpretive phenomenological analysis.

Results

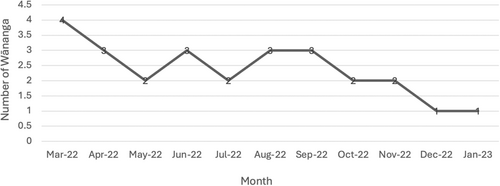

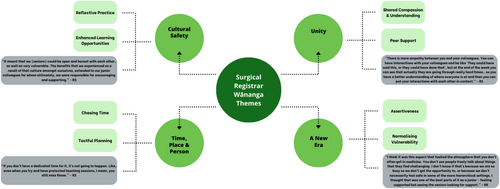

Twenty-six wānanga were held from March 22nd 2022 to January 30th 2023. Six registrars provided their perspectives with four major themes emerging from their stories including: cultural safety; unity; time, place and person; and a new era. Registrars valued the wānanga which was scheduled for Friday afternoons after daily clinical duties. Wānanga facilitated unity and understanding with registrars being able to reflect on the context within which they are practicing – describing it as a new era of surgical training. ‘Time’ was the biggest barrier to attend wānanga however, the number of wānanga held was testament to the commitment of the registrars.

Conclusions

Regular wānanga set up by, and for, surgical registrars cultural safety development is feasible and well subscribed in a rural or provincial NZ setting. We present one coalface method of regular cultural safety training and development for surgical registrars and trainees in NZ.

Introduction

Cultural safety and cultural competency form the recently added 10th competency of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS).1 Practising culturally safe surgical care to address health inequities requires that surgeons take responsibility for the environment in which surgeons work by critically assessing whether the services provided meet the needs of the community.2 The general surgical curriculum is yet to institute evidence-based, cultural safety teaching to ensure the training of a clinically competent and culturally safe general surgical workforce for New Zealand (NZ).

Wānanga are indigenous teaching forums that can be used for cultural safety training.3 Historically, whare wānanga were traditional Māori institutions of learning where specialized teachings were delivered by tohunga, revered keepers of knowledge within hapū (subtribes).4 Contemporarily, wānanga can be characterized as ‘teaching and research that maintains, advances, and disseminates knowledge and develops intellectual independence’.5 To foster a culturally safe environment, surgical registrars based at Taranaki Base Hospital (TBH) in NZ formed a rural and provincial surgery (RAPS) network to undertake regular wānanga. Taranaki is a provincial region in NZ with three general surgical trainee positions serving a region of 124 380 people of which Māori comprise 20%.6

In collaboration with mana whenua (local Māori), Māori clinicians and academics, surgical registrars at TBH held regular wānanga focussed on cultural safety, professionalism and wellbeing. The delivery framework adhered to key principles of the tenth RACS competency (Table 1).7-9 This study sought to explore registrars' perspectives of participating in regular surgical wānanga and how wānanga enhanced their professionalism, cultural safety, and wellbeing as surgical registrars.

| RACS cultural competence and cultural safety behavioural markers | RAPS wānanga initiative |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Methods

A qualitative study was deemed most useful for addressing the aims of this study for a small cohort of registrars. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies informed the reporting of this study.10

Methodology

Whilst most registrars who participated in RAPS wānanga were non-Māori, the intervention of interest is Kaupapa Māori and as such, this research was aligned with Kaupapa Māori research methodology. This ensured a Kaupapa Māori lens to assessment of the wānanga and promotes structural analysis of establishing cultural safety training for surgical trainees and non-training registrars utilizing mātauranga Māori. The research is led by Māori which ensured Māori autonomy and governance over research decision-making and processes.11 This research also opposes deficit theory and rejects racism in keeping with Te Tiriti and rights-based approaches to research.12

Data collection

Purposive sampling of all registrars who participated in the RAPS wānanga was utilized to recruit registrars into this evaluative study. A semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary Fig. 1) facilitated, in-depth, interpersonal interviews with either a local Māori clinical nurse specialist, who was independent of the registrar group (BD), or by the first author (J-LR). Interviews were conducted in person at TBH or via Zoom to facilitate flexibility for collaborators to participate given the busy nature of surgical registrars' schedules.

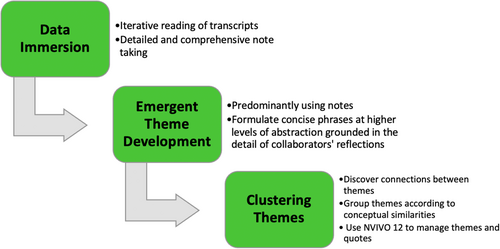

Data analysis

With a Kaupapa Māori methodological stance, interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was applied to facilitate in-depth analysis of surgical registrars' experiences of partaking in regular wānanga.13 This qualitative approach seeks to provide detailed examinations of personal lived experiences in its own terms rather than one prescribed by pre-existing theoretical preconceptions.14 It is also explicitly idiographic in its commitment to examining the detailed experience of each case in turn, and is considered most useful for examining topics which are complex, ambiguous and emotionally laden.15 Two researchers (J-LR and JT) initially immersed themselves in the data by reading the transcripts at least three times. Detailed exploratory notes were formulated in tandem to explore observations and reflections of potential significance in more depth (Fig. 1).16

Researcher positionality and reflexivity

As researchers' interpretative activity is also involved in IPA, known as a ‘double hermeneutic’, a transparent description of researcher positionality is described. The lead researcher (J-LR) is a surgical trainee who is also an experienced mixed-methods Kaupapa Māori researcher. Senior Kaupapa Māori, tikanga Māori and clinical health researcher support was provided by two senior Māori clinicians (MH and JT). Additionally, local mana whenua oversight was provided by a surgical and Māori health nurse specialist (BD) and who was also collaborated as an objective interviewer.

Ethical statement

All registrars who participated in wānanga were invited to be interviewed and to contribute to writing and editing this study to ensure their agency over their stories. Therefore, this research is co-created by a collective of collaborators rather than a small team conducting research upon passive ‘participants’.15 Informed consent was obtained from all registrar collaborators and all registrars consent to the publication of this study.

Results

Twenty-six wānanga were held between March 22nd, 2022 and January 31st, 2023 (Fig. 2). Six registrars collaborated in this research with the remaining three registrars consenting to be interviewed but not following through to book an interview timeslot. Following analysis, four superordinate themes were created with several subordinate themes leading to their development (Fig. 3) with Supplementary Figure 2 presenting a coding table of the key codes forming the superordinate themes.

Cultural safety

Despite its longstanding conceptualisation, cultural safety has only recently been recognized as a priority by governing medical bodies and specialty medical colleges.17, 18 Borne from the colonial context of NZ society in response to the poor health status of Māori, cultural safety is centred on continued self-reflection of one's own practice and how one's own cultural practices and biases may impact patient care.19 Cultural competency speaks to the attitudes, skills and knowledge needed to function effectively and respectfully when working with, and treating, people of different cultural backgrounds.18

Reflective practice

‘The wānanga is something that should be implemented and supported for trainees because it not only makes you a better doctor but it makes you a better person when you are able to reflect on your practice and reflect on how you interact with others’. – R1

Three registrars noted that the more senior registrars often openly shared their reflections within the group and with each other outside of wānanga. This enabled the junior registrars to develop trust within wānanga as the senior registrars attempted to role-model reflective practice through their honest discussions about their training experiences.

Enhanced learning opportunities

‘I don't think I would do anything to the format of it because I think that part of the beauty of it is that it just was what it was. We all turned up, we all had an opportunity to chat and I think if it was more structured or if you added anything else, that would take away from what it is potentially’. – R5

Integrity

‘I felt that it was absolutely a safe space and I think that was very well communicated from the get go. There was a real sense of trust in the room to be honest. I did feel that’. – R5

From the beginning, all registrars bought into participating in the wānanga as it was presented following the occurrence of difficult cases for which several of the registrars were directly involved. There was a pre-existing unity within the team and without that and the solid level of buy-in by all registrars; the wānanga would not have eventuated.

Unity

A recent study interviewed surgical registrars and residents to explore what makes a good surgical resident.23 Surgical registrars valued interpersonal skills within the surgical team as important and acknowledged that teams are comprised of many roles, differing personalities and communications styles and that adaptation to complexities of the team is essential.23

Shared compassion and understanding

‘It also unifies the team. With medicine and with surgery you get all these type A individuals that are there for – “I do my work, I do a good job, you're problem is not my problem”. Whereas that culture is really smashed with the culture of wānanga. You create more of a “we're all doing the same job, we're providing a service to the community”. That's my take on it anyway’. – R4

Peer support

Continuity of support was noted as wānanga progressed. Experiences were revisited and referred to more than once, and over multiple wānanga, if required. Peer learning should be incorporated into the delivery of the surgical ethics curriculum as it allows surgical trainees to feel comfortable to ask questions and voice their thoughts and opinions.24 In addition, the relaxation of formalities that accompanies peer learning also lends itself to more open discussion.25 The wānanga also fostered registrars' confidence in reaching out to their colleagues if they needed to debrief on work-related issues outside of wānanga itself.

Time, place and person

Chasing time

‘Where clinical work and acuity takes precedence then absolutely, teaching, wānanga/peer group and administrative duties will take a back foot. However, departments should recognise that whilst we have this natural understanding, and that service provision is their core business, this should not be used as an excuse to side-line our aspirations to refine and develop our non-technical skills such as cultural safety, communication and advocacy. We owe that to our patients, to each other, and to our profession’. – R3

Three registrars stated that they did not think surgical departments would support protected time given that they struggle to honour formal teaching sessions in work hours. This is largely because teaching is usually facilitated by consultant surgeons who also have their own schedules and because of the unpredictability of general surgery. Despite this, all registrars agreed that commitment to supporting non-technical skill development is needed by departments.

Tactful planning

Functional and positive relationships with colleagues enrich the clinical experience, aid in decision-making consensus for difficult cases, and facilitate the sharing of responsibilities.26, 27 However, ‘the team’ can also serve as a source of ethical dilemmas or conflict.26, 28 While collegial relationships were mostly positively described by registrars, it was acknowledged that where tension existed between individuals in the group, the wānanga was not the space for those interpersonal concerns to be aired. It was understood that wānanga did not displace the need for baseline workplace professionalism and communication.

‘I think that if this was to be done in a larger hospital setting then smaller groups would help to keep that trust and safety. I wonder if you did have the benefit of a larger hospital then smaller groups may allow people to raise concerns comfortably in one group that they may not be happy to raise in the wider group. That is something I would think about’.– R5

A new era

With the advent of policies established by the RACS around diversity, workplace bullying and harassment and Indigenous health, there was a unified understanding that registrars were coming through a new era of surgical training.29, 30

Assertiveness

All registrars felt safe enough to assert their voices in wānanga, especially when discussing negative clinical experiences. Most importantly, there were honest assertions by registrars relating to their own paradigms and how the wānanga compelled them to reflect on their own cultural identity and biases. It was observed that the culture within the registrar group evolved to cultivate mutual respect despite differences between individuals, within wānanga. This is because the values assigned to the time and space of wānanga were consistent with trust and confidentiality. Equally, registrars were able to assert themselves if they did not feel like contributing to discussions in wānanga.

Normalizing vulnerability

‘I think it was really cool to see people who often don't talk about things, as basically it's not what society pushes especially with males, and to see some of my male colleagues open up and be vulnerable and feel safe to do that was really encouraging as well because I know women do that well’. – R1

‘I've never seen anything like it so I wouldn't even know. It is so new and against the set system of what we expect in hospitals. I didn't know what to expect and what I got from it was amazing’. – R1

Discussion

This study shows that a regular wānanga set up by, and for, surgical registrars' training requirements is feasible and well subscribed in a rural or provincial NZ setting. In the absence of formal surgical education in cultural safety, the RAPS wānanga were set-up by industrious surgical registrars who were committed to learning cultural safety. Registrars valued the wānanga which was demonstrated by their sustained commitment to attending these sessions on Friday afternoons each week. Registrars experienced and reported that wānanga served as a culturally safe space to gain knowledge and skills necessary for becoming culturally safe practitioners. Additionally, wānanga facilitated unity among colleagues with registrars being able to reflect on the context within which they are practicing – describing it as a new era of surgical training. Lastly, registrars unanimously agreed that ‘time’ was the biggest barrier to attend wānanga but, given its value, made the time to be there. This is vital for all surgical departments in NZ but is particularly important for rural and provincial surgical departments who rely on a smaller workforce to deliver surgical care to their communities.

In January, 2023, Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa and Te Kaunihera o ngā Kāreti Rata o Aotearoa published a cultural safety training plan to support all medical colleges in the delivery of cultural safety training into their core curricula.32 The plan's primary intention was to advocate for high-quality healthcare and better health outcomes for Māori in clinical consultations. Following the introduction of cultural safety as a standard for doctors by the Medical Council of New Zealand in 2019, the RACS introduced its 10th competency entitled cultural safety and cultural competency.1 Currently, RACS fellows can earn continuing professional development points for cultural safety and cultural competence activities however, a formal curriculum and training module is yet to be developed for surgical trainees. Applying evidence-based, purposeful, pedagogical praxis that advances the required self-awareness, erudition and skills is critical to the success of cultural safety training. A recent systematic review appraising Indigenous cultural safety training programmes and workshops for healthcare workers internationally found limited evidence regarding the efficacy of specific approaches.33 This was due to multiple modalities of delivery and whilst each study described specific training approaches, formats or content and how they may have contributed to impact, most authors were careful to note the limitations of their outcomes and the need for further research.

The delivery of cultural safety training through regular on-site wānanga has not yet been considered in surgical training. So far, only one group has utilized wānanga in surgery through the delivery of an annual weekend wānanga to support Māori non-training registrars applying for surgical training.34 Nicholls et al. have continued to run this initiative since 2019 with their biggest resource comprising volunteer Māori surgical trainees.34 Whilst Hardy et al. reported only one cultural safety intervention for healthcare professionals in NZ in their systematic review, wānanga are being utilized in other colleges.33 Te Akoranga a Maui, the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners Māori group, are the first Indigenous representative group established by any Australasian medical college and have been in operation since 2002.35 This group delivers annual wānanga to deliver Māori health and cultural safety training to all of their trainee registrars. Additionally, many independent Māori and non-Māori organizations offer cultural safety training and would not have published evaluations of their services in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

In relation to rural and provincial surgery in NZ, research looking into the ways in which departments can successfully recruit surgeons is lacking. Rural communities struggle most for recruitment and our IMG surgical workforce has been key to maintaining our rural and provincial surgical workforce.36 It has been estimated that the annual recruitment of new surgeons required for rural NZ ranges from 30 to 47 new surgeons.37 Key to attracting surgeons to the country is adequate exposure during surgical training or earlier.36 Paynter et al. highlighted that rural general surgeons in their study cohort wanted a cohesive workplace with collaboration.38 Our study supports this notion with the RAPS wānanga promoting unity which was vital to the provincial surgical registrar experience.

This is a small study reporting registrars' experiences of a RAPS wānanga series from a single provincial hospital in NZ. Despite this, given a RAPS wānanga has never been instituted before, the design and methodological approach for this study is justified given the focus on a small group of registrars and alignment with previous interventions evaluated in the same manner.33 Lastly, the non-collaboration by three registrars, who were all male, should not diminish the fact that all three registrars attended wānanga regularly. Whilst their experience is not shared in this forum, their involvement and attendance is still valued and respected. Thank you.

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time that a wānanga delivered on-site and regularly dedicated to cultural safety and wellbeing is possible in a provincial NZ hospital. As a result of the findings of this study, collaborators present a framework by which other registrar groups may formulate a similar program for themselves (Supplementary Fig. 3). The Authors encourage all surgical specialty training bodies to consider mandating protected time for registrars to undertake cultural safety training on a regular basis and to support registrars developing their own wānanga, as required, for the cohesivity of their team.

Acknowledgements

The Authors acknowledge the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) Academy of Surgical Educators for funding Dr. Rahiri with a Research Scholarship to undertake this research and acknowledge Mr. Nigel Henderson (FRACS) for his invaluable support as a tuakana of our wānanga. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflict of interest

None declared.