Multicenter investigation of the reliability and validity of the live donor assessment tool as an enhancement to the psychosocial evaluation of living donors

Abstract

The live donor assessment tool (LDAT) is the first psychosocial assessment tool developed to standardize live donor psychosocial evaluations. A multicenter study was conducted to explore reliability and validity of the LDAT and determine its ability to enhance the psychosocial evaluation beyond its center of origin. Four transplant programs participated, each with their own team of evaluators and unique demographics. Liver and kidney living donors (LDs) undergoing both standard psychosocial evaluation and LDAT from June 2015 to September 2016 were studied. LDAT interrater reliability, associations between LDAT scores and psychosocial evaluation outcome, and psychosocial outcomes postdonation were tested. 386 LD evaluations were compared and had a mean LDAT score of 67.34 ± 7.57. In 140 LDs with two LDATs by different observers, the interrater scores correlated (r = 0.63). LDAT scores at each center and overall stratified to the conventional grouping of psychosocial risk level. LDAT scores of 131 subjects who proceeded with donation were expectedly lower in LDs requiring postdonation counseling (t = −2.78, P = .01). The LDAT had good reliability between raters and predicted outcome of the psychosocial evaluation across centers. It can be used to standardize language among clinicians to communicate psychosocial risk of LD candidates and assist teams when anticipating postdonation psychosocial needs.

Abbreviations

-

- LD(s)

-

- living donor(s)

-

- LDAT

-

- live donor assessment tool

-

- RMTI

-

- Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institute

1 INTRODUCTION

Live organ donation has become a prominent source of transplantation to fill the discrepancy between the need and availability of organs. There are 116 929 people awaiting life-saving organs in the United States, the majority of whom are in need of a kidney or liver transplant.1 In 2016 alone, approximately one quarter of all kidney and liver transplants were from living donors (LDs) (5979/23 247); this has been consistent over the past 5 years.1 Although the specific process of the live organ donor evaluation may differ by transplant center, all LD candidates must undergo an extensive medical and psychosocial screening to determine their suitability for donation.2-4

Studies have shown that psychosocial factors are an important predictor of LD candidacy and can have a large impact on postdonation outcome.5-11 This makes not only the identification of psychosocial risk but also the communication of its associated meaning essential for donor safety. The psychosocial assessment is conducted by clinical social workers, psychologists, and/or psychiatrists, whose training and approach may differ. As a critical part of the evaluation process, the findings are discussed with all members of the team. A standardized tool can assist in effective and efficient communication of psychosocial risk amongst clinicians.

The live donor assessment tool (LDAT) was created for clinicians involved in the psychosocial evaluation process and was found to be reliable and valid in both retrospective and prospective studies at a single academic transplant center.12, 13 The tool consists of 29 items that had been deemed important through expert opinion and/or empiric research to include in a donor psychosocial evaluation (Appendix S1), and came from 9 domains (motivations for donation, knowledge about donation process, relationship with the recipient, support available to the donor, donor's feelings about donation, postdonation expectations, stability in life, psychiatric history, and alcohol and substance use).2, 10, 12, 14-16 The individual items scored from 0 to 3 were each given similar weight with higher numbers corresponding to lower psychosocial risk. The overall score ranging from 0 to 82 is a proxy for overall psychosocial risk and can be used to help guide practice and improve care both pre- and postdonation alongside the conventional psychosocial evaluation.13

A multicenter study was conducted to further explore the reliability and validity of the LDAT and determine its ability to enhance the psychosocial evaluation beyond its center of origin. Four diverse transplant programs participated, each with its own team of evaluators and unique donor demographic profiles. We prospectively (a) tested the LDAT's interrater reliability, (b) determined associations between LDAT scores and the LD psychosocial evaluation outcome, and (c) identified whether the LDAT predicts LD psychosocial outcomes postdonation. Findings of this study will help to establish the LDAT as a standardized approach, enhancing the communication of psychosocial risk among clinicians.

2 METHODS

We conducted an institutional review board-approved multicenter prospective study. Four centers were involved in evaluating participants: Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institution at Mount Sinai Hospital (RMTI) (NY), University of California San Francisco Medical Center Transplant Center (CA), William J. von Liebig Center for Transplantation and Clinical Regeneration, Mayo Clinic (MN), and The Kidney and Pancreas Transplant program at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine (NY).

2.1 LDAT training

The psychosocial evaluations were conducted by licensed clinicians (social workers and psychiatrists) employed at the transplant programs. Clinicians all had several years of experience conducting psychosocial evaluations of LD candidates. Prior to beginning the study, the psychosocial clinicians were provided with standardized training on use of the LDAT and relevant materials. The training consisted of 2 phases. First, a group conference call was conducted to introduce the tool and research process. Next, trainees accessed the online LDAT learning module created by RMTI. The module includes videos of the conventional psychosocial evaluation using simulated patient interviews and an interactive scoring module with explanations on how the LDAT is scored, providing an opportunity for each clinician to complete the tool with guidance.17 Additional discussions for clarification were carried out via conference calls as needed.

2.2 Participants

All potential English-speaking LDs at the 4 sites who underwent LD evaluation from June 30, 2015 to September 22, 2016 were eligible for the study. Liver donors being assessed to donate for the reason of acute liver failure in an emergent situation were excluded. Participants met with the transplant coordinator and nephrologist/hepatologist and completed a psychosocial evaluation. Eligible LD candidates were informed of the study. Those who were interested were provided with information about the study, its purpose, and procedures and explicitly informed that study participation would not affect their evaluation process, nor would it influence their clearance as a donor. Candidates were advised that the score would be completed after the psychosocial evaluation and kept confidential and deidentified. Each enrollee provided written informed consent and was made aware of their right to discontinue participation in the study at any time.

2.3 Procedure

The prescreening, order of the comprehensive LD evaluation process, and triggers for the psychiatric assessment differed across centers (Table 1). An experienced psychosocial clinician conducted the psychosocial portion of the evaluation according to the standard practice in the transplant program. All programs had similar processes for psychosocial evaluation and for noting a conventional but subjective psychosocial risk group categorization (high risk, moderate risk, and low risk) in the clinical chart.18, 19

| Center 1 | Center 2 | Center 3 | Center 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescreen |

|

|

|

|

| Length |

|

|

|

|

| Interval bet medical eval and LDAT | After education, RN and MD visits | Day 2 or by phone for distant donors | Varies | After RN and MD |

| Psychiatry triggers | Liver donors: all kidney donors with:

|

Liver and kidney donors with:

|

Liver donors: all kidney donors with:

|

Kidney donors with:

|

- MD, medical doctor; RN, registered nurse; ILDA, independent living donor advocate; KPD, kidney paired donation.

2.4 Measures

Clinicians completed all 29 LDAT items in REDCap for each enrolled subject after completion of the psychosocial evaluation. Subjects who required both social work and psychiatric evaluation had scores from 2 independent clinicians. For the subjects who proceeded to donation, 6 psychosocial outcomes were assessed by a separate clinician at 6 weeks postdonation. Nonadherence to treatment along with psychosocial interventions were noted in the chart by the clinician. Work impairment, relationship impairment, psychological status (eg new symptoms/changes, anxious or low mood, feelings of regret), and pain requiring intervention were reported by the patient. These 6 variables were scored in REDCap as improved = −1, unchanged = 0, or impaired = 1.

2.5 Data analysis

Reliability of the LDAT was assessed by (a) internal consistency, and (b) interrater reliability. Internal consistency, which signifies whether the individual items measure same/similar constructs, was measured by calculation of Cronbach's alpha of 386 primary LDAT scores. Interrater reliability was measured by calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient for the 140 LDAT score pairs by 2 independent clinicians (social worker and psychiatrist).

Validity was assessed by comparing the LDAT to existing psychosocial risk categories, and postdonation outcomes. ANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc test of mean LDAT scores of each category was used to look into how the total LDAT score can differentiate the conventional clinical risk classification. Postdonation psychosocial outcome was evaluated. ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's Honest Significance test was used to analyze whether the preoperative LDAT scores were indicative of the outcomes that were categorized as improved, unchanged, or impaired.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

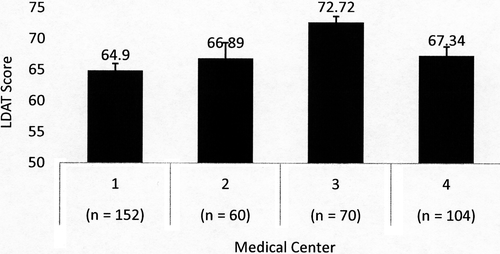

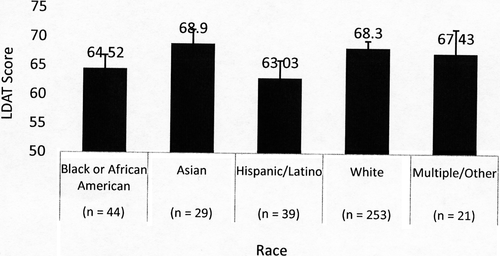

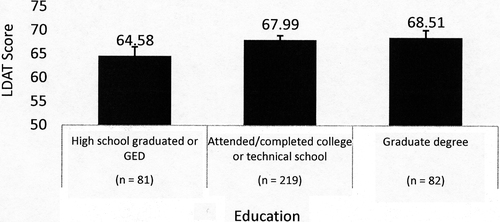

Out of 402 consented LD candidates, 386 evaluations were completed. Overall mean age of the sample was 42.4 years (SD = 12.6) and mean LDAT score was 67.34 (SD = 7.57). Kidney donor candidates were older than liver donor candidates (mean 43.0 vs 38.3 years) and female donor candidates were older than male donor candidates (mean 44.0 vs 40.6 years). Comparison of the LDAT score mean of Center 3 was significantly higher than the other centers with a large pooled Cohen effect size (d = 0.90), and remained different when controlling for race and education level in a logistic regression model (Figure 1). Race was categorized using standard National Institutes of Health (NIH) classification.20 Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino LDAT score means were significantly lower than White and lower than Asian when controlling for center and education. High school graduate LDAT score means were significantly lower than those with college or graduate school education when controlling for the other variables in this model (Figures 2, 3). Other characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 2.

| Characteristic (n) | Age (SD) | Mean LDAT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (386) | 42.4 (12.6) | 67.34 (66.58-68.09) |

| Organa | ||

| Kidney (337) | 43.0 (13.1) (P = .01) | 67.53 (66.74-68.32) |

| Liver (49) | 38.3 (7.4) | 66.02 (63.73-68.30) |

| Sexa | ||

| Male (177) | 40.6 (12.9) (P = .01) | 66.12 (64.91-67.33) |

| Female (209) | 44.0 (12.3) | 68.37 (67.45-69.29) |

| Centera (Figure 1) (P < .001) | ||

| Center 1 (152) | 64.90 (63.80-66.00) | |

| Center 2 (60) | 66.89 (64.40-69.38) | |

| Center 3 (70) | 72.72 (71.77-73.67) | |

| Center 4 (104) | 67.34 (65.89-68.79) | |

| Racea (Figure 2) (P = .002) | ||

| Black or African American (44) | 64.52 (62.18-66.86) | |

| Asian (29) | 68.90 (66.47-71.33) | |

| Hispanic/Latino (39) | 63.03 (60.01-66.05) | |

| White (253) | 68.30 (67.09-69.50) | |

| Multiple/other (21) | 67.43 (63.29-71.57) | |

| Directednessa (P = .03) | ||

| Directed (345) | 67.86 (67.04-68.68) | |

| Nondirected (41) | 62.98 (61.17-64.79) | |

| Relationshipa (P < .001) | ||

| Related (280) | 68.96 (68.16-69.76) | |

| Unrelated (106) | 63.07 (61.58-64.56) | |

| Education levela (Figure 3) (P = .004) | ||

| Graduated high school or GED (81) | 64.58 (62.68-66.48) | |

| Attended/completed college/technical school (219) | 67.99 (67.06-68.91) | |

| Postcollege graduate degree (82) | 68.51 (66.98-70.04) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time (263) | 67.97 (67.13-68.81) | |

| Part time (58) | 65.97 (63.81-68.13) | |

| Not working (60) | 66.42 (64.19-68.65) | |

| Disability (5) | 61.00 (52.09-69.91) | |

- a Indicates statistically significant difference between groups.

3.2 Reliability

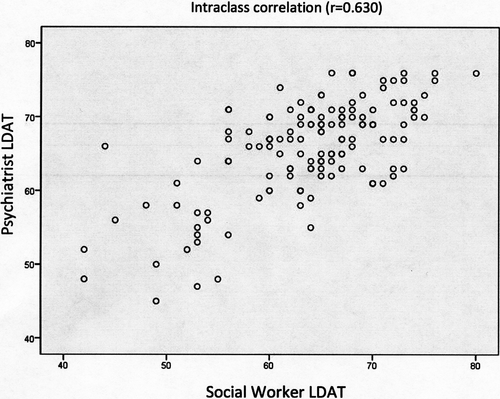

Among the 386 LD candidates with completed evaluations, 140 were administered 2 LDATs during the process by 2 different evaluators, a social worker, and a psychiatrist. The intraclass correlation across the 4 centers was good (r = 0.630, P < .001) (Figure 4).

LDAT internal consistency for 383 candidates with complete data showed that α= 0.759 among all 29 items, indicating an acceptable level of internal consistency.

3.3 Validity

3.3.1 LDAT association with conventional clinical risk status

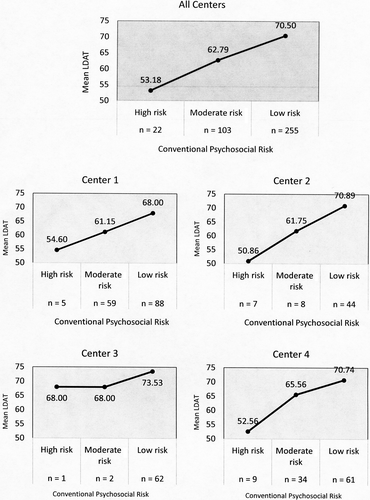

Among the participants, 22 (6%) were categorized as high risk with a mean LDAT = 53.18; 95% CI, 49.93-56.42 (range 42-68); 103 (27%) were categorized as moderate risk with a mean LDAT = 62.79; 95% CI, 61.49-64.09 (range 42-76); and 255 (67%) were categorized as low risk with a mean LDAT = 70.50; 95% CI, 69.87-71.13 (range 54-80). Post hoc analysis showed that all 3 groups' mean LDAT score were significantly different (P < .001) with a very large Cohen effect size (d = 1.32). Results of LDAT association with conventional psychosocial risk status by center are shown in Figure 5.

3.3.2 LDAT association with postdonation psychosocial outcomes

There were 131 LD postdonation outcomes assessed as part of this study. The overall mean LDAT score of candidates who eventually donated (n = 255) was 68.83; 95% CI, 68.04-69.62. There was a statistical difference with the mean LDAT score of 66.57; 95% CI, 65.20-67.94 for candidates who did not donate (n = 131).

Twenty-six donors experienced medical complications, 1 donor experienced a recipient death, and 3 donors experienced a recipient with graft failure (including recipient death).

Because of a small number of negative psychosocial outcomes and poor recipient outcomes, comparisons of centers and correlations between donor and recipient outcomes could not be carried out.

Psychosocial outcomes were assessed at a 6-week time-point (n = 131) using 6 categories (work, relationships, psychological status, psychosocial interventions required, pain, and treatment adherence). There were 14 LDs who needed additional counseling by either social work or psychiatry after donation and n = 117 who received standard follow-up. Those who needed additional counseling had a preoperative mean LDAT score of 65.79 (63.71-67.87) were significantly lower (P = .01) than those with a standard follow-up (mean LDAT of 69.20 [68.00-70.39]). Besides a correlation between those who required additional counseling, other psychosocial outcomes (including work impairment, relationship impairment, and psychological status) that were assessed did not show statistically significant results in mean LDAT score. There were 21 LDs who were rated as nonadherent to follow-up. Their preoperative mean LDAT score of 72.52 (70.27-74.77) was significantly higher compared to the adherent donors 68.25 (67.07-69.43).

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate the reliability and validity of the LDAT as a semistructured psychosocial assessment in a sample of potential LD candidates at 4 diverse centers. The results of this multicenter study successfully replicate our previous retrospective and prospective single-center work and show that the LDAT has good reliability and demonstrates evidence of validity to be used in the psychosocial assessment of living organ donors in a variety of settings by a diverse group of clinicians.

This study found that the 29 LDAT items demonstrate acceptable internal consistency (α = .759), closely replicating the value obtained in the single-center study of α = .799.13 Despite the multidimensional nature of the LDAT, its internal consistency could be improved. The LDAT was reliably scored across trained raters (12 in total) demonstrating “good” interrater reliability in 140 cases that were independently rated by 2 evaluators. When used in conjunction with the conventional psychosocial evaluation, the LDAT had validity. LDAT scores differentiated the conventional outcome categories resulting from the standard psychosocial evaluation, revealing a significant difference in LDAT scores among the high-, moderate-, and low-risk groups. Moreover, the LDAT scores increased from high-risk to moderate-risk to low-risk groups as would be predicted.

Given our results, it is hoped that the LDAT may be used more broadly to standardize and enhance the LD psychosocial evaluation and promote efficient discussion within and between living donation teams across different centers. The results of this study are promising in that the LDAT can indeed be used as a standardized language among clinicians when communicating psychosocial risk of potential LD candidates and improve the training of new psychosocial clinicians. Centers participating in kidney paired donation and distant donor evaluations now have a standardized language to use when considering LDs evaluated elsewhere. Recently a new tool, the ELPAT psychosocial assessment tool (EPAT), was developed to guide the practitioner in “how” to conduct the psychosocial interview with the LD.21 Although the 28-item EPAT contains overlapping domains with the LDAT, it requires a more directed semistructured interview. In contrast, the LDAT allows practitioners to conduct their own interview and then holistically measure and report a scored outcome of the psychosocial evaluation.

As a heuristic tool developed to include all the standard domains of a LD psychosocial evaluation along with risk stratification, the LDAT models standard practice at most US transplant centers. In this study, the LDAT was adopted at 3 additional centers with diverse facilities and practice. Each center's evaluators were able to complete the standardized tool at the end of their usual interview that included all the guideline-based components of the LD assessment. In addition to clinical utility, the output of the LDAT language and scores may serve centers to study and report the psychosocial characteristics of their donor pool.

Although the 4 centers differed in their evaluation process, particularly in the prescreening of donors prior to evaluation, the order of testing, and perhaps their tolerance for risk, it was observed that they also manifest a different range of LDAT scores. Center 3 recorded the highest mean LDAT score and had the most robust prescreening of all the centers. They also serve significantly more White LDs (90%) as compared to Center 1 with the lowest mean LDAT score and lowest number of that demographic (58%). Despite different practice protocols, donor demographics, and comfort level for risk, the total LDAT score mapped onto the individual center's conventional evaluation category (high, moderate, and low risk). This further illustrates that the components of the LDAT mirror essential areas covered in existing practices.

The diversity among the centers was also seen in the demographics such as race and educational level. The LDAT scores differed by race with mean scores of Asian and White donors significantly higher than mean scores of Black and Hispanic donors. Additionally, those donor candidates with lower education levels had lower LDAT scores. There is not enough data to determine whether these differences are clinically relevant and predict outcome. Furthermore, the limited sample size did not allow for investigation of associations with respect to all confounding variables including center, organ type, sex, directedness, relationship, education, or employment status. We would be remiss, however, not to note that US disparities in socioeconomic status have a profound effect on access, delivery, and perception of health care services,22, 23 and implicit bias could not be ruled out. Further study is warranted.

A direct association was found between LDAT scores and one indicator of postdonation psychosocial outcome. Lower LDAT scores seemed to predict who needed postoperative psychosocial intervention. Such statistical difference shows that the LDAT can prospectively flag patients who may need further psychosocial counseling. This would allow clinicians to more efficiently identify those at risk for postdonation psychosocial intervention and alter postoperative care plans as needed.

It must be noted that the purpose of the LDAT is not to be an obstacle for living donation but rather a tool to assist in helping appreciate candidates' psychosocial risk profile and intervene as needed to minimize risk. The tool's 29 questions cover all expertly identified areas of importance to the psychosocial evaluation. The LDAT's quantitative measure is not a means to rule out more candidates than would a standard psychosocial evaluation or the conventional low/moderate/high risk classification. On the contrary, the LDAT can serve as a practical tool to identify targeted intervention prior to donation to support candidacy. For example, LDs who present with problems in specific areas in their knowledge can be referred for additional education and those with insufficient support can be placed on hold while resources are secured. Ambivalence may be reduced to improve negative donor outcomes such as regret. Other factors found important to postdonation psychological health that cannot be modified, such as the relationship with the recipient (ie nondirected, close relationship, distant relationship), can nonetheless be codified and studied later for meaning.

This study has notable strengths. The LDAT was developed by a seasoned multidisciplinary team with decades of experience in the live organ donation process and psychosocial research and in consultation with experts around the world. The tool covers a range of psychosocial factors found in the literature that relate to the process of live organ donation. The study group found similar reliability and validity in a wider and varied subject group. Replicating the results at multiple sites with multiple clinicians and different demographics only strengthens the tool, eliminating any bias that existed in the prospective study and proving value by increasing the generalizability of the results to the larger live organ donor population. One of the limitations of this study was that Center 2 was closed for 6 months of the study duration due to unforeseen circumstances. Although the number of evaluations in the center suffered, it did not harm the integrity of the prospective multicenter study as the center continued data collection afterwards.

Another limitation of the study was that the 4 centers that participated in the study were quite heterogeneous in terms of prescreening processes, patient population, and/or overall donation process. Although this may have resulted in different mean LDAT scores of donor candidate populations with statistical significance in different centers, there were still interrater reliability and internal consistency across evaluations of the subjects enrolled by all 4 centers. In practice, this could signify that the LDAT can be adjusted to meet the needs of different centers.

Lastly, there were only a few postdonation outcomes that showed correlation: the need for postdonation counseling and postdonation adherence to follow-up. Our results for postdonation adherence showed contradicting results from previous prospective single-center study; hence, its reliability is in question. The LDATs ability to predict who may require counseling, however, is an important finding with enormous clinical implications. Lack of additional correlations may be attributed to the small number of eventual donors that experienced negative outcomes. Prescreening and a rigorous donor candidate evaluation both medically and psychosocially take place before a candidate is cleared for donation. Programs screen out donor candidates who would have negative outcomes; therefore, few have negative outcomes. This makes it inevitable for minimal number of negative outcomes to occur in donors, which is unfortunate for the study design.

This study opens potential for further research to improve the LDAT. For a more distinct differentiation of risk evaluation of a potential donor, investigating which items on the LDAT affect the total score may help reorganize the weight or points that the items are allocated. Likewise, distinguishing risk factors that may more likely predict short-term psychosocial distress vs long-term and how individual risk profiles change over time may be beneficial. Other factors, including socioeconomic status that may influence the LDAT score should be further studied.

In conclusion, the LDAT was developed to address the need for a standardized approach to the psychosocial evaluation for live organ donors. In this multicenter study the LDAT tool demonstrated good psychometric properties (reliability and validity) as well as utility in predicting LDs who are at risk for negative postdonation outcomes, specifically the need for counseling postdonation. We feel that the tool has significant clinical utility beyond the standard psychosocial evaluation: (a) it adds an objective score to what can be viewed as a subjective assessment of risk; (b) it can improve the communication of risk within the psychosocial team and the clinical team; (c) it can improve the communication of risk to the donor – instead of saying a prospective donor is not a candidate from a psychosocial perspective, it can provide donors a more comprehensive view of the issues; (d) it can facilitate communication in the setting of KPD; (e) it can identify donors at risk for negative psychosocial outcomes, and (f) it may guide the team in the development of interventions to improve donor candidacy.

It is hoped that our results support further implementation of the LDAT across different transplant centers with a goal to standardize and enhance the communication of psychosocial risk and evaluation of donor candidates, which will ultimately guide practice toward providing improved care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The LDAT Study Group: Zorica Filipovic-Jewell, MD, Brandy Haydel, Brian Iacoviello, Ph.D, Ella Mershon, Tamara Turner LMSW, David Serur, MD, Marian Charlton, RN, Katherine Rhee, Meredith Aull, Pharm D, Tami Halverson, LICSW, Stephanie Hokanson, Lisa King, RN-CCTC, Kay Kosberg, RN-CCTC, Deb Tarara, RN-CCTC, Nicola Ehrenberg, RN, Finesse Wong, RN, Alvin Lau, MD, Brian Lee, MD.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.