Where have all the (HCV-positive) kidneys gone?

See also: Kiberd et al, Kadatz et al, and Chascsa et al

Abstract

Sawinski reviews two Markov decision analyses for timing of HCV therapy and expanded use of HCV-positive kidneys, as well as the real-world transplant consequences of HCV treatment in transplant candidates. See the companion articles on pages 2443, 2457, and 2559.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment has been revolutionized. Once a chronic infection associated with poor posttransplant outcomes, it is now a highly curable condition. Effective therapies exist, even for patients with end-stage renal disease or kidney transplants. This has created new quandaries around treatment timing as well as new opportunities, including transplantation of HCV-infected organs into uninfected recipients.

In this issue of the Journal, two Markov decision models are presented.1, 2 The first examines the decision faced by HCV+ kidney transplant candidates on the waiting list—to treat HCV now or postpone therapy in order to facilitate transplantation with an HCV-infected donor. The second explores the cost-effectiveness of the still-experimental practice of transplanting HCV-infected organs into HCV-negative recipients.

Using parameters from HCV+ dialysis patient cohorts and the United States Renal Data System, while assuming a 1-year wait-time advantage for those accepting an HCV-infected donor, Kiberd et al1 determined that pretransplant treatment for HCV was associated with increased life years gained as well as greater quality adjusted life years (QALYS). However, they noted that if the burden of HCV-related mortality was assumed to be low or there was an abundance of HCV-infected organs, then posttransplant treatment conferred a survival advantage. The authors did not specify at what stage of liver fibrosis, pre- versus posttransplant treatment dominated, leaving this as an open research question.

In the work by Kadatz et al,2 using data from the Canadian health system, the authors demonstrated that transplanting HCV- recipients with HCV-infected organs was associated with greater QALYS than waiting for an HCV- kidney; this strategy was cost-effective even if the wait-time to transplantation was reduced by as little as one year, with greater gains realized if 2 years of dialysis time could be saved. These findings persisted in sensitivity analyses in which HCV transmission to recipients was not universal, and in which allograft survival from HCV-infected donors was inferior to HCV- kidneys.

Why the seemingly divergent study results? Although Kadatz et al employed Canadian data, their costs are comparable to those encountered in the United States; another study utilizing data from the United Kingdom also found a cost benefit.3 However, there are significant differences in the populations simulated—in the Kiberd study, HCV+ waitlist candidates had an established burden of HCV disease; the risk of disease progression was balanced against the benefit of earlier access to transplantation. To the contrary, in the work by Kadatz, all transplant candidates were HCV- and therefore only derived benefit by accelerating transplantation.

It is important to remember that these studies are simulations; although designed to assist decision-making, they are only models, and real-world evidence to support their findings is necessary. In this regard, the data from Chascsa et al4 are particularly useful. They reported the differing outcomes of HCV+ patients at 2 transplant centers within the same health system. One center treated candidates pretransplant; for these patients the kidney transplant rate was significantly lower (12.5% versus 67.9%) and the median wait-time was significantly longer (650 days versus 122 days). HCV+ candidates at the second center were treated posttransplant; 68% received an HCV-infected organ and 100% of patients achieved HCV cure. None of the patients in the posttransplant treatment group experienced hepatic decompensation despite a third of them having cirrhosis on biopsy.

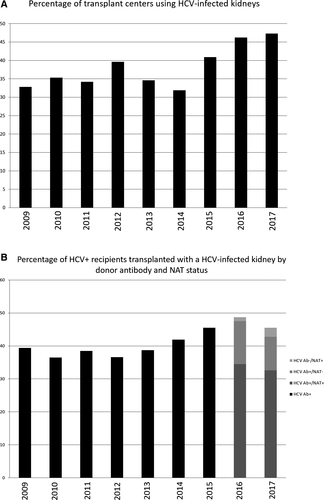

Central to all 3 manuscripts is the availability of HCV-infected organs and the wait-time advantage provided by accepting them, which was last formally studied more than a decade ago.5 Current data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) demonstrate that less than 50% of HCV+ recipients are transplanted with HCV-infected kidneys and less than 50% of transplant centers utilize these organs (Figure 1A,B); the median time to transplantation for HCV+ recipients of HCV antibody–positive kidneys from 2009-2017 was 209 days (interquartile range [IQR] 59-558) compared to 776 days (IQR 261-1482) for antibody-negative organs. Why? For the minority of patients who spontaneously clear their infection but remain antibody positive for life, an HCV-negative kidney is appropriate. Patients or transplant providers may have concerns about the negative effect of HCV on allograft longevity, as reflected in the Kidney Donor Risk Index6; although posttransplant treatment may ameliorate these risks, this remains unproven. Reassuringly, the biopsies performed in the study by Chascsa failed to demonstrate significant pathologic abnormalities, but numbers were small. Generally patients accepting HCV-infected organs are transplanted more quickly; therefore transplant candidates may feel that this benefit outweighs the potential risks. So how can they advocate on their own behalf? Patients look to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Program Specific Reports for guidance about the quality of the care provided at their transplant center. Including information regarding center acceptance practices for HCV-infected donor organs, as is reported for high Kidney Donor Risk Index or “hard to place” organs, should be considered; this would inform transplant candidates of their options and encourage centers to revisit their practices. As the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients updates their reporting to make it more patient-centered, the addition of this type of information would be helpful to patients and providers alike.

With growing momentum for the use of HCV-infected organs in HCV- recipients in response to ever-increasing waits for transplantation, we should first consider if we have provided all HCV+ candidates with the opportunity to accept an HCV-infected kidney. If not, then greater efforts to enable access to HCV-infected kidneys for all HCV+ recipients who will accept them are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The data reported here have been supplied by UNOS as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the U.S. Government. This study used data from the OPTN. The OPTN data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the OPTN. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN contractor. The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Wiseman and Dr. Roy Bloom for thoughtful discussions on this topic.

DISCLOSURE

The author of this manuscript has no conflicts of interest to disclose as defined by the American Journal of Transplantation.