Understanding the enablers to implementing sustainable health and well-being programs for older adults in rural Australia: A scoping review

Abstract

Introduction

Supporting the health and well-being of older Australians necessitates the implementation of effective and sustainable community-based interventions. Rural settings, however, pose unique challenges to intervention implementation and sustainability, with limited research exploring strategies employed to overcome these complexities.

Objective

To identify enabling strategies that support the sustainable implementation of community-based health and well-being interventions for older adults in rural Australia.

Design

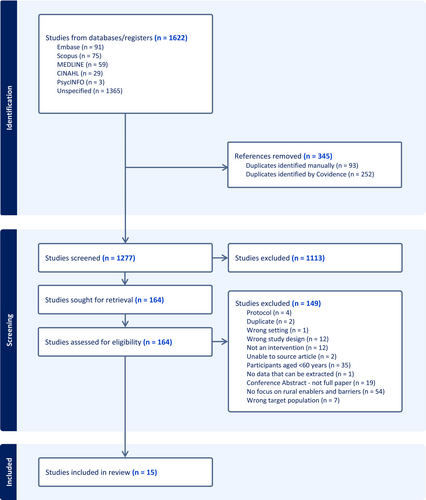

A scoping review, following methods by Arksey and O'Malley and enhanced by elements of the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), was conducted. An electronic search of seven databases was completed in April 2023. A thematic analysis was applied to provide a comprehensive and contextualised understanding of the phenomenon of interest.

Findings

Of 1277 records screened, 15 studies were identified and included for review. Five themes identified key enablers for rural implementation: (1) Co-designing for the local context; (2) Embedding local champions; (3) Leveraging existing local resources; (4) Maintaining impact beyond the end of the funded period and (5) Flexibility in funding models.

Discussion

The sustainable implementation of interventions requires active community involvement and consultation through all stages of program design and delivery to effectively meet the health and well-being needs of older rural-dwelling Australians.

Conclusion

Our findings advocate for clear implementation guidelines to support the design, delivery and adaptation of community-based programs that appropriately reflect the unique contextual needs and strengths of rural communities.

What is already known about this subject

- One-third of older Australians reside in rural areas, where they experience higher prevalence of chronic disease and poor health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts.

- Community-based programs designed within urban environments may not translate well to rural contexts.

What this paper adds

- Rural program design and implementation must recognise the pivotal role of collaborative processes that integrate local expertise through methods such as local partnerships and co-design.

- Tailoring health and well-being interventions to the specific needs of older people residing in rural communities can enhance their relevance, effectiveness and sustainability.

- Implementation strategies specific to the unique needs and strengths of individual rural communities are needed to support sustainable interventions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Community-based interventions are pivotal to optimising the health and well-being of Australia's ageing population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a critical challenge of governments and policy-makers globally is securing equitable access to health services for rural, regional and remote populations,1 collectively referred to as rural from herein. Investing in the health of older adults through activities relevant to their unique social determinants has become a public health priority.1, 2 Australia's demographic profile reflects long-term trends of younger people relocating to major cities and of retirees moving away from them, which has resulted in a higher proportion of older adults residing in rural areas.3 One-third of older Australians live outside of city areas,3 highlighting the critical need for effective and sustainable community-based health and well-being interventions in rural areas.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's (AIHW) Rural and Remote Health Report examines the unique challenges faced by rural Australians, acknowledging that geographic constraints and health service inequities lead to poorer health outcomes for rural people than are experienced by people living in cities.4 The availability of essential health and community services in rural settings is impacted by complexities such as higher service delivery costs, limited infrastructure, workforce shortages, reduced availability of services and fewer community and economic resources.4 The social, geographic and demographic diversity that characterises rural Australia also means that one-size-fits-all solutions often fall short of meeting the unique health and support needs of diverse rural communities.

Designing interventions that actively consider their successful implementation and sustainability is essential to supporting the accelerated translation of research into practice. This is particularly important when implementing community-based interventions in rural settings. The challenges associated with implementing rural programs are readily apparent; however, there is a dearth of literature that examines enabling factors, and no evidence-based guidelines to inform the design and implementation of effective and sustainable interventions in rural Australia. In rural areas, where the experience of health and well-being in later life is significantly impacted by the availability of appropriate community-based services and supports,3 addressing this gap becomes essential.

2 BACKGROUND

Implementation frameworks provide structured guidance on key considerations and strategies to be included in the planning, execution, evaluation and sustainability of successful programs. Understanding context is identified as a central component in most implementation frameworks and is described as having a practical understanding of how specific organisational practices, local systems and environmental settings influence implementation.5

The WHO identified and analysed nine leading implementation frameworks that were informed by a range of diverse theoretical and disciplinary perspectives.6 This analysis concluded that while all of the frameworks recognised local context as important and some provided tools to assess context, very few considered strategies to address the impact of identified issues on implementation.6 This analysis was used as the foundation to develop an overarching framework designed to address knowledge translation and the implementation of services and supports for older adults.6 The resulting guidelines concur with wider consensus that contextual tailoring is key to successful implementation,5, 7, 8 though as with other existing frameworks, consideration of the significant impact rural contexts have on implementation remains absent.

The challenges of applying frameworks conceptualised using urban indicators were explored recently in a scoping review by Montayre et al.9 This review examined how WHO's age-friendly guidelines inform interventions with older adults in rural and remote areas, revealing many health-related interventions lacked consideration of the physical or social environments in which they were implemented.9 The practical implications of this were demonstrated in a US study that analysed 70 projects funded to implement existing health programs in rural settings, with the most commonly identified challenge being the need for significant modification and tailoring of programs to fit local context and community-specific requirements.8 These adaptation problems were also discussed by Morgan et al.,10 who found urban-based models of care for people living with dementia lacked strategies to address geographic, service delivery and other challenges that impact implementation and sustainability in rural settings. These examples highlight the problematic nature of a primarily metropolitan-centric evidence base for interventions with older adults, particularly in the absence of evidence to guide implementation plans focused on the needs of rural communities.

A recent study of research translation in rural areas by King et al.11 highlighted the additional skills needed by rural health care professionals to not only understand and evaluate the original evidence but also to critically consider the clinical and environmental context to determine the adaptations necessary for implementation in their own rural location. King et al.'s11 findings emphasise the need wherever possible to support the conduct of place-based, contextually relevant rural research. A recent Australian study by Wong Shee et al.12 examining rural research capacity found researchers who understood local context was essential to generating interventions that were relevant, acceptable and effective in rural communities. The capacity for rural health professionals and organisations to engage in research, however, was impacted significantly by systemic factors such as macro-level workforce and rural research funding policies, health service expectations and organisational prioritisation of research.

The successful implementation of community-based programs and the quality of program outcomes are also impacted by their compatibility with broader community context and local delivery systems.8 These contextual considerations are widely promoted as central factors of success in implementation frameworks. However, guidelines and other published literature rarely focus on the distinctive characteristics of rural settings, limiting the availability of relevant information to effectively support researchers, program staff, funding bodies and supporting organisations during the design and execution of rural programs.8 This scoping review will explore the implementation of community-based health and well-being programs with older adults in rural Australia, by drawing together what is currently known about the enablers, barriers and strategies that impact the effectiveness and sustainability of interventions.

3 OBJECTIVES

The objective of this scoping review is to identify enabling strategies that support the sustainable implementation of health and well-being interventions for older adults residing in rural Australia. The specific review questions are: What are the enablers and barriers to implementing community-based interventions that support the health and well-being of older rural Australians? What strategies have been used to overcome the barriers to the effective implementation of community-based health and well-being programs with older rural Australians?

4 METHODS

This scoping review followed the methodological framework for scoping reviews described by Arksey and O'Malley13 and incorporated the recommendations for enhanced reviews developed by Levac et al.14 Eligibility criteria development was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Population, Concept and Context (PCC) elements for scoping reviews15 and strengthened by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.16 Following this methodology, a priori eligibility criteria were devised, with consideration given to the broad research question, based on the Population, Concept and Context (PCC) elements. The protocol was registered with Open Science Framework.17

4.1 Search strategy

A comprehensive electronic search of seven databases was conducted in April 2023. Search terms were developed with the assistance of a research librarian. Databases searched include Ageline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus. Search terms were mapped to medical subject headings as appropriate with all search terms and combination of Boolean operators displayed in a File S1 for transparency and replicability. All database search strategies were limited to English language and human studies. The search was date limited to between January 2011 and April 2023. This date range was selected to encompass literature published following release of the 2011 Productivity Commission Inquiry into Aged Care and the subsequent Living Longer Living Better Aged Care Reforms,18 which shifted the focus of aged care in Australia more overtly towards community-based supports. The search results from all databases were first imported into Endnote (V20) reference management software for removal of duplicates and then imported into Covidence systematic review software for record screening.

4.2 Study selection

During the first round of screening, publication titles and abstracts were independently screened by at least two reviewers (Authors 1, 2 and 5) according to the eligibility criteria displayed in Table 1. All conflicts were reviewed and discussed to achieve consensus. Full texts were then subject to a second round of screening by reviewers (Authors 1, 2, 3 and 4). Again, conflicts were discussed with consensus achieved on all studies included for review.

| Population |

|

| Concept |

|

| Context |

|

4.3 Data extraction

Data were extracted by at least two reviewers (Authors 1, 2, 3 and 5) using a custom extraction template developed within Covidence. Information extracted included publication title, authors, year of publication study aims, intervention type and details, study population, description of geographic context, methodology, study outcomes inclusive of enablers and barriers to implementation and how the intervention was cognisant of rurality. All conflicts were resolved by discussion between the listed reviewers with consensus achieved for all included data. Extracted data were then transferred out of Covidence into Microsoft® Excel® for analysis and synthesis.

4.4 Data analysis

Study characteristics were collated by Author 5 using descriptive statistics to provide an overview of the included articles. Extracted data were initially categorised by Author 1 and Author 3 to identify content relevant to the enablers, barriers and strategies used to implement programs within the rural context. A thematic analysis of these categories was then conducted by Author 3, with emerging themes reviewed by Authors 2 and 4. These themes were further developed and finalised in a full team discussion. Thematic analysis was chosen to explore common patterns within the data and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon of interest.19 Saturation was considered to have been achieved once no new codes or themes emerged from the data.20 All coding and theme development was conducted and tabled using Microsoft® Word®.

5 FINDINGS

The PRISMA flowchart displayed in Figure 1 details the identification, screening and inclusion of articles. Of 1277 records screened, 15 studies were identified and included for review as summarised in Table 2.

| Article | Study aim | Outcomes relevant to rural program implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Almeida et al. (2021)22 | An RCT to test if a behavioural activation program was more effective than usual care at reducing the risk of conversion to major depression over 52 weeks among adults aged 65 years or older living in rural Western Australia |

|

| Bateman et al. (2016)35 | To examine acceptability and feasibility of trained volunteers providing person-centred care to enhance emotional care, safety and well-being of individuals with dementia and/or delirium |

|

| Blackford et al. (2016)30 | An RCT of the home-based Albany Physical Activity and Nutrition program with people at risk of metabolic syndrome in a disadvantaged rural Western Australian community |

|

| Courtney-Pratt et al. (2011)26 | A pilot to investigate feasibility of a rural cardiac rehabilitation program while fostering further collaboration among local health care providers |

|

| Dent et al. (2017)27 | An RCT to determine the benefits of two approaches for the management of musculoskeletal conditions in rural South Australia: A self-management plus multi-component intervention versus usual care |

|

| Dollman et al. (2016)24 | To identify correlates of walking in middle age and older adults in two rural South Australian regions to inform community development framework for physical activity promotion in rural Australia |

|

| Lesjak et al. (2012)33 | Reports on the impact of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on the psychological well-being and quality of life for older men involved in a remote population |

|

| LoGiudice et al. (2012)25 | Development and implementation of a locally designed community service model of care for older people, and people with disability and/or mental health problems in remote Aboriginal Australia |

|

| Nott et al. (2019)34 | Pilot to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of Ageing Well, a community-based program for improving cognitive skills and mobility of rural older people |

|

| Orchard et al. (2020)21 | Using refined eHealth tools to improve, inform and assess cost-effectiveness of atrial fibrillation screening in the rural setting |

|

| Paul et al. (2019)31 | To determine the feasibility and acceptability of a new outreach model of allied health primary care for improving health outcomes for people living with chronic disease in remote and rural NSW |

|

| Roberts (2017)29 | To investigate factors associated with participation in a diabetes nurse-educator led self-management program that aimed to increase access to local diabetes support, education and management for rural Australian clients with Type 2 diabetes |

|

| Slater et al. (2012)32 | To evaluate the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary model of care for consumers with lower back pain living in geographically isolated areas of WA, using a modified (Self Training Educative Pain Sessions) program |

|

| Wilczynska et al. (2021)28 | A pilot to evaluate the preliminary effectiveness and feasibility of the ecofit intervention using a scalable implementation model in a rural Australian community |

|

| Winterton & Hulme Chambers (2017)23 | Explores barriers to delivering sustainable rural community programs to increase participation among Australian ethnic seniors |

|

5.1 Study characteristics

The studies included in this scoping review focused on a variety of different interventions and used a range of methodologies. As seen in Table 3, the majority of studies were conducted in NSW. Nine of the 15 studies classified their location as rural, although only three studies reported this using a valid measure of rurality (n = 2 used the Australian Statistical Geography Standard21, 22; n = 1 used the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia23). Community-based studies were the most frequently reported.

| Category | Detail | Per cent | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study location | New South Wales21, 28, 31, 33-35 | 40.0% | 6 |

| Western Australia22, 25, 30, 32 | 26.7% | 4 | |

| South Australia24, 27 | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Victoria23, 29 | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Tasmania26 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Study rural classificationa | Rural23, 24, 26-31, 35 | 60.0% | 9 |

| Remote25, 32 | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Regional34 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Regional/Remote22 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Rural/Regional21 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Rural/Remote33 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Study setting | Community-based program22-25, 27, 28, 31, 33 | 53.3% | 8 |

| Primary Health care/GP21, 26, 32 | 20.0% | 3 | |

| Community Health Service29 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| University Clinic34 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Home-based30 | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Volunteer-based hospital program35 | 6.7% | 1 |

- a Classification of rurality is presented as identified by authors of original articles.

Table 4 shows that almost all studies employed individual interventions using a quantitative methodology. Of the 15 studies, only 27% explicitly referred to considerations for implementing an intervention in a rural area in their methodology. The included studies consisted of an average of 333.8 participants, with a minimum of eight, and a maximum of 3103. More than half of the studies involved participants who were community members with specific health conditions. Most studies' samples consisted of a majority of females (n = 53%). One-fifth of the studies had a majority of male participants, and two studies reported equal male and female participation. Gender was not reported in two studies. Across all studies, the mean age of participants was 66.6 years (minimum age = 59.8; maximum = 83.8).

| Category | Detail | Per cent | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Quantitative | 80.0% | 12 |

| Mixed methods | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Qualitative | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Level of intervention | Individual | 80.0% | 12 |

| Group | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Organisation | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Type of participant | Community member with specific health issue | 53.3% | 8 |

| Community residents | 13.3% | 2 | |

| Hospital patients | 6.7% | 1 | |

| Community stakeholders | 6.7% | 1 |

Thematic analysis of the studies in this review identified five overarching themes that contributed to the enablers, barriers and strategies associated with the effective implementation of an intervention for older people in a rural community: co-designing for the local context; embedding local champions; leveraging off existing local resources; maintaining impact beyond the end of the funded period and flexibility in funding models.

5.2 Co-designing for the local context

A key success factor identified across the studies was embedding a co-design approach to understand the local context. Most studies highlighted that every rural community is different and employing a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be successful. From the experiences of the studies reviewed, adopting place-based approaches in the planning phase that incorporated all relevant stakeholders was seen as important for the successful implementation of interventions with rural older people.22, 24, 25 Using co-design methodologies to facilitate successful buy-in from the rural community enabled the intervention to be fit for purpose, while encouraging stakeholder engagement,23, 25-28 which was seen as critical for success within the local context.

Due to the uniqueness of individual rural communities, several studies suggested that during the co-design phase there needed to be consideration given to offering a range of intervention delivery methods and approaches that suited specific communities, to enable more program participation.22, 27, 29 In some rural areas, accessing appropriate transport, as well as the cost of transport, was a significant barrier to recruitment and retention in interventions.23, 29 Other studies highlighted the need to consider whether in-person programs, virtual care or a combination of both would be better suited for the specific community.21, 28, 30-32 Although virtual or web-based approaches were considered useful in overcoming access issues, two studies identified that unreliable internet access and low digital literacy led to poor retention in the interventions,28, 31 which also warrants consideration. The ability to be flexible and incorporate appropriate strategies based on early stakeholder engagement and co-design sessions was seen as a useful strategy to support rural implementation.23, 26, 29

The reviewed studies commonly identified that rural communities often had limited access to health professionals and specialists to support health outcomes. As such, there was a need to consider creative solutions during the design phase that allowed for flexibility in how the intervention was implemented or modified to suit older people living in different rural communities, given the variability of access to health services.27, 32 One way to address this variability was to offer preventative approaches either through specific programs or screening, which was seen as beneficial for older rural community members.21, 33, 34 For this to succeed, local stakeholder engagement was needed during the design phase to understand where the gaps were for individual communities and what cost-effective approaches would be most suitable21 rather than making assumptions about what was needed. Early identification of specific community needs related to access and availability of evidence-based resources to support program implementation at a community level was also seen as important.32

5.3 Embedding local champions

Four of the studies reviewed indicated that the range of challenges they experienced in translating and implementing interventions for older people in rural locations may have been better resolved if there were local champions to support the implementation phase.23, 26, 29, 35 One study by Winterton and Hulme Chambers23 indicated that having ongoing discussions with key local contacts would have more easily resolved issues on the ground and supported the recruitment aspect of the program. Other studies highlighted that the support of project champions such as local health professionals was likely to influence engagement and participation from older people, as these champions were trusted sources.26, 29, 35 This also extended to having localised project management for the intervention or program to ensure greater success and buy-in of stakeholders.25 Having local champions embedded within a program was seen as a key factor in program success because these individuals were already part of the community and held valuable insights about location-specific factors likely to impact implementation in their area.

5.4 Leveraging off existing local resources

One of the challenges noted in the studies was that it was often difficult to get staff with the right skill set within the specific rural location, and it was important to identify alternative options within the existing community to support programs or interventions on the ground.23 This often included developing the program in a way that provided flexibility in who can deliver it and supporting staff to gain the skill set needed.28, 29 Supporting the upskilling of existing health professionals and other local community members meant that skills were not lost at the end of the program or intervention, which had the potential to improve long-term sustainability.25 Deliberately designing programs or interventions that could be delivered without the need for highly specialised skills and knowledge was also considered a useful strategy, particularly in areas where there were limited resources to access.22

Incorporating existing local community assets, resources and attributes where possible was also seen as useful in supporting successful implementation of programs or interventions in rural locations.24, 26 Given the challenges often associated with the recruitment and retention of health care professionals in rural communities, the ability to create private–public partnerships or to leverage off existing programs or resources provided a cost-effective and more sustainable strategy to enable effective implementation of rural programs or interventions for older people.26, 35 The involvement of both public and private health care providers by Courtney-Pratt et al.26 enhanced local partnerships and even led to further planned collaborations between nurses from both sectors.

5.5 Maintaining impact beyond the end of the funded period

A key consideration often overlooked in the design of rural interventions is planning for how program impact can be maintained beyond the end of the funded period. Programs are commonly set up for a specific period of time, without direct focus given to sustainability within the post-program phase. The ability to identify and provide pathways for either ongoing support or alternative options for older rural people to continue with the potential benefits of programs once interventions have been finalised was seen as important across five of the included studies,23, 25, 30-32 particularly for organisations that have provided in-kind support and resources during the intervention phase.23

Two studies highlighted the need for deliberate support systems to be put in place, or at least considered, as part of the post-program sustainability.31, 32 Suggested systems included facilitating access to health services and having an appropriately skilled workforce to enable program participants to continue to be supported for longer periods after they complete the relevant program.31, 32 Without consideration of long-term sustainability, some older rural people may not be able to access necessary support to maintain benefits gained from the program, resulting in a loss of these benefits over the long term.25, 30 Understanding the existing resources and services within the local context and aligning these with the intervention or program outcomes was seen as an important opportunity to facilitate ongoing support of health outcomes for older rural people post-completion of the program or intervention.26

5.6 Flexibility in funding models

It was highlighted across all studies that there were often additional costs associated with implementing a program or intervention within a rural location and this needed to be considered in the design phase and reflected in funding applications. Due to funding limitations, it was common for staff to be employed part-time on rural programs or interventions. This often resulted in staff subsequently trying to manage multiple roles or competing priorities alongside their program/intervention role, which could result in delays and further cost implications.23 Lower population density in rural communities also meant that recruitment and retention activities often took longer than expected, which added pressure to staff and challenged program sustainability.23

Finally, providing opportunities to incorporate innovative or alternative local solutions was identified as a way to support the design and implementation of better rural programs and interventions. Ensuring funding was flexible enough to accommodate a range of different approaches, such as public–private collaboration, or upskilling staff to undertake a different or extended scope or practice given the resourcing limitations in rural communities was considered important.26, 29

6 DISCUSSION

The findings of this scoping review highlight the importance of community-driven, flexible and locally tailored approaches when implementing health and well-being interventions for older adults living in rural communities. The research suggests the need for active engagement with local stakeholders and project champions, appropriate resource allocation, adaptable funding models and evidence-based implementation strategies. Barriers impacting these interventions included individual and community differences, accessibility challenges, technological and health literacy barriers, resource limitations, issues with program design and adherence, and complexities in community engagement and decision-making processes. Conversely, key enablers identified in the review included facilitating local connections and trust, gaining support from health professionals, integrating social networks, minimising logistical challenges, and utilising co-design and community involvement to enhance social cohesion and address specific needs within the community. The research suggests that tailoring health and well-being interventions to the specific needs of older people residing in rural communities can enhance the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of rural programs.

Only a quarter of the reviewed studies explicitly considered in their methodology how the rural context might impact implementation. Understanding the unique enablers and barriers that might affect implementation, including socio-cultural considerations, resources and infrastructure, is vital to develop or adapt effective interventions.36 This becomes especially important if the intervention is designed outside of the local research setting, or by researchers and program implementers unfamiliar with the local context. Adopting a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be effective in these cases; instead, tailored and community-specific interventions are essential, especially in these settings. Ensuring access to evidence-based resources is also crucial; however, previous research has highlighted the underutilisation of research evidence in local health and well-being strategies, particularly in areas of complex need such as rural locations.37 Efforts to disseminate and support uptake of resources can be facilitated through digital platforms, community centres and local libraries.38

Collaborative research partnership approaches (e.g., co-design) involving consumers and communities have been recognised as valuable when developing and implementing health and well-being interventions in rural areas.39-42 Such approaches highlight the importance of embedding co-production strategies during the design, delivery and evaluation of health initiatives to ensure interventions address the distinct place-based challenges and needs of rural populations. Early and comprehensive engagement with stakeholders, including community members, local leaders and health care professionals, is essential to ensure relevant and culturally sensitive programs, highlighting factors such as building relationships, defining expectations and valuing diverse contributions.11, 39, 43-45

The active involvement of local champions and localised project management are also invaluable to the implementation of successful health and well-being interventions for rural populations. For example, Lê et al.46 found that local councils played a critical role in delivering health promotion initiatives in rural Australia and provided a greater understanding of the needs of their communities. Project management through local government and community-based services can ensure interventions are culturally relevant by providing an in-depth understanding of the community's culture, traditions and beliefs. As highlighted in this study by LoGiudice25 this approach may be especially pertinent in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.47 Local project champions embedded within the community are often familiar and well-trusted, which can encourage community members to participate and continue with programs. Their local knowledge and awareness of community challenges associated with access to health facilities, transportation issues and communication barriers can provide invaluable insights to navigate issues effectively.

In the reviewed studies, challenges frequently arose in maintaining programs beyond the initial funding period. Securing the ongoing commitment of local health professionals and resource providers to ensure program continuation was a key enabler to program sustainability demonstrated by Courtney-Pratt et al.,26 empowering the community to become self-sufficient and ensuring program longevity. Often, program implementers secure a grant and then conduct a trial without contemplating the post-intervention sustainability.48 This oversight can limit buy-in from rural communities, as they may perceive it as another short-term investment, potentially reducing engagement. Another financial enabler was showcased by Roberts,29 who demonstrated how a well-designed funding model provided the essential flexibility needed to ensure their program could be adapted to meet the unique needs of older participants in a rural setting.

These findings are consistent with and complement previous research indicating that active community participation, partnerships in designing interventions, and innovative and flexible funding approaches are pivotal in achieving sustainability and expanding access to health and well-being services in rural populations.7, 49 The enabling principles identified in these findings provide evidence-informed strategies to support the design and delivery of interventions with older Australians in rural areas.

6.1 Strengths and limitations

This review has some strengths and limitations. The search strategy was developed for the Australian context, encompassing diverse sources including peer-reviewed journal articles and grey literature, spanning seven multidisciplinary databases. Screening, extraction and analysis by at least two experienced, independent reviewers enhanced reliability. A limitation of this review lies in the absence of citation tracking for reviews and articles identified in the original search, potentially omitting additional relevant sources. Another limitation is that most of the studies reviewed were conducted in rural areas, so distinctions were not able to be made about differences between rural, regional and remote areas. It should also be noted that only three of the included studies reported their geographic classification by using a recognised measure. The focus solely on older adults in Australia means it is not possible to infer relevance of these findings to the implementation of rural programs with other population groups or to other countries. Further research examining the implementation of community-based programs with other populations in rural communities is required to build on this focused review of programs with older adults.

7 CONCLUSION

The themes identified in this scoping review interconnect to provide a comprehensive understanding of strategies that support the design and delivery of effective and sustainable rural health and well-being interventions with older Australians. The implications derived from this analysis underscore the need for a paradigm shift in approaching rural health interventions with older adults, and for rural health interventions more generally. Researchers, policy-makers, program designers and program implementers must recognise the pivotal role of collaborative research processes that integrate local expertise through methods such as co-design, harnessing community resources and deploying flexible funding models. The review highlights the need for comprehensive implementation strategies that actively consider the unique needs and strengths of rural communities to cultivate sustainable interventions. This integrated approach is not only vital for enhancing the health and well-being of older Australians in rural areas but also holds promise for similarly disadvantaged populations. Further research of the identified enablers is required to provide a robust evidence base to inform guidelines able to better support researchers and program designers to develop implementation strategies that can successfully navigate known challenges in providing effective and sustainable health and well-being interventions with older adults in rural Australia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Belinda Cash: Conceptualization; investigation; formal analysis; writing – original draft; funding acquisition; project administration. Michael Lawless: Conceptualization; investigation; formal analysis; writing – original draft; methodology. Kristy Robson: Writing – original draft; investigation; formal analysis. Shanna Fealy: Formal analysis; investigation; writing – review and editing. Denise Corboy: Writing – review and editing; formal analysis; investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Constance Kourbelis, Shannon Brown and Dr Carolyn Gregoric for their contributions to the early development of this review. BC acknowledges that Charles Sturt University Faculty of Arts and Education provided funding to support research assistance for this project (DC). KR is supported by the Three Rivers Department of Rural Health, who are funded by the Australian Government under the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program. Open access publishing facilitated by Charles Sturt University, as part of the Wiley - Charles Sturt University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All listed authors contributed directly to the conduct of the research presented and development of the manuscript. There are no conflicts to declare, and all authors have read and approved the manuscript for submission.