Emergency presentations for farm-related injuries in older adults residing in south-western Victoria, Australia

Abstract

Introduction

Farm workers are at high risk for injuries, and epidemiological data are needed to plan resource allocation.

Objective

This study identified regions with high farm-related injury rates in the Barwon South West region of Victoria, Australia, for residents aged ≥50 yr.

Design

Retrospective synthesis using electronic medical records of emergency presentations occurring during 2017–2019 inclusive for Local Government Areas (LGA) in the study region. For each LGA, age-standardised incidence rates (per 1000 population/year) were calculated.

Findings

For men and women combined, there were 31 218 emergency presentations for any injury, and 1150 (3.68%) of these were farm-related. The overall age-standardised rate for farm-related injury presentations was 2.6 (95% CI 2.4–2.7); men had a higher rate than women (4.1, 95% CI 3.9–4.4 versus 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.3, respectively). For individual LGAs, the highest rates of farm-related emergency presentations occurred in Moyne and Southern Grampians, both rural LGAs. Approximately two-thirds of farm-related injuries occurred during work activities (65.0%), and most individuals arrived at the hospital by transport classified as “other” (including private car, 83.3%). There were also several common injury causes identified: “other animal related injury” (20.2%), “cutting, piercing object” (19.5%), “fall ⟨1 m” (13.1%), and “struck by or collision with object” (12.5%). Few injuries were caused by machinery (1.7%) and these occurred mainly in the LGA of Moyne (65%).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study provides data to inform future research and resource allocation for the prevention of farm-related injuries.

What is already known on this subject?

- Agricultural workers have some of the highest rates of injury of any occupation.

- WorkSafe Victoria released the “Agriculture Strategy 2020-23” describing the dangers and a plan to improve safety in agricultural settings, which requires contemporary evidence and data.

- Farm workers often continue work-related activities past the age of retirement.

What does this study add?

- Approximately 3.7% of all emergency presentations in adults aged ≥50 years occurred in in a farm environment.

- Higher rates of farm-related emergency presentations occurred in the Local Government Areas of Moyne and Southern Grampians.

- These results can help inform future research and prevention strategies for farm-related injuries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Agriculture is an occupation associated with a high risk of injury, given that workers are exposed to a wide variety of hazards including machinery, vehicles, falls, animals and chemicals.1-3 Injuries in the agricultural workforce can be severe due to the types of exposures, requiring significant time off work and potentially leading to death, psychological trauma or permanent disability.1, 4-6 A report from SafeWork Australia showed that agriculture had the highest rates of injury across all industries in 2019 and consequently has been identified as a priority industry for prevention strategies.3 In addition, agricultural workers (including farmers, farm managers and farm workers) often continue to perform farm-related tasks past the age of retirement due to financial concerns, a desire to maintain independence and productivity, and a perception of retirement as a major change to their identity.7 Older farm workers may also have multiple health conditions, which puts them at higher risk of significant injury or mortality and complicates their treatment in hospital following an injury.8-11 This is growing more common; the average age of farmers in Australia has increased from 47 years in 1986 to 51 years in 2001 and 58.8 years in 2018–2019.12, 13

The region of Victoria is Australia's second most populous state. In Victoria, the most dangerous workplaces are in the agricultural industry; only 2% of the total workforce is employed in agriculture, but during 2009–2019, 32% of all workplace fatalities occurred in this industry.14 WorkSafe Victoria has released the “Agriculture Strategy 2020–23”, which describes the dangerous nature of the industry and a plan to improve safety in agricultural settings.14 This strategy is based on the Hierarchy of Risk Controls outlined by Safe Work Australia,15 which describes management of risks through the most effective preventative option; firstly by elimination of the hazard, followed by substitution or isolation of the hazard, engineering controls, safer work practices and finally personal protective equipment. A key enabler for the plan described in the “Agriculture Strategy 2020–23” report will be the access to appropriate, contemporary evidence and data, both during the development phase and during longer term monitoring.

The principal data describing farm injuries in Victoria are derived from the emergency departments (EDs) of 14 regional and five metropolitan hospitals.2 These EDs provide 24-h services every day and are required to report to the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD), which is a complete data collection for the 40 EDs that report to the VEMD. The VEMD does not contain emergency presentations from smaller emergency facilities (e.g. Urgent Care Centres, or smaller hospital-based rural emergency facilities), designated one to three on a six-level ED classification.16 These facilities have fewer resources than larger EDs and are not required to provide data to the VEMD.17, 18 It has been reported that up to 35% of injury-related emergency presentations among children aged 0–14 years occur in small rural emergency facilities that do not report to the VEMD.19, 20 However, some of this deficit in emergency presentations are reported to the Victorian Department of Health in aggregate form via the AIMS Urgent Care Centre collection. Additionally, the VEMD captures fewer emergency presentations for injury in rural compared to urban areas.18 Consequently, to provide more comprehensive data for rural emergency presentations, the Rural Acute Hospital Database Register (RAHDaR) was established in 2017.21 This database collects similar data to the VEMD for 10 smaller centres located in the western region of Victoria, known as the Barwon South West region. The aim of RAHDaR is to provide epidemiological data to guide health service planning and coordination, policy assessment and formulation, clinical research and quality improvement.21

Given the increased number of potential sources of hazards in farming environments and the workforce often being older with multiple health conditions, safety strategies require detailed and relevant contemporary data. The aim of this study was to utilise data from the VEMD and RAHDaR to provide a more complete description of injuries sustained by older adults (≥50 years) in the region of south-western Victoria, which occurred on farms and required emergency treatment.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study region

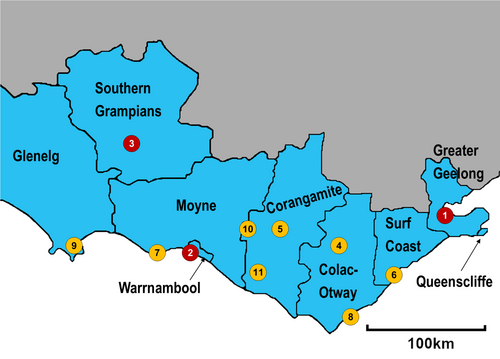

This study forms part of the Ageing, Chronic Disease and Injury (ACDI) Study, which has been described in detail elsewhere.22 The ACDI study aims to provide data for chronic disease and injury in older adults across a geographical area that includes urban, regional and rural settings, which can then inform strategies for targeted health services delivery and infrastructure development. The current study focusses on a smaller region of the larger ACDI study area, the Barwon South West (Figure 1), to align with the area covered by both RAHDaR and VEMD.

The state of Victoria (Australia) is divided into 79 smaller geographical regions, known as Local Government Areas (LGAs). The current study includes nine of these, located in the south-western region of the state. These LGAs include Colac-Otway, Corangamite, Glenelg, Greater Geelong, Moyne, Queenscliffe, Southern Grampians, Surf Coast and Warrnambool. According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics,23 the residential population aged ≥50 years residing in this region during 2016 was 152 714. The region includes a mix of urban rural towns and agricultural areas with a range of farm types including sheep and cattle grazing as well as dairy and cereal cropping.

2.2 Data sources

- The Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD), which keeps records for all public hospitals with an ED across Victoria. In the study region, this includes the University Hospital Geelong, Warrnambool & District Base Hospital and Hamilton Base Hospital. Data from the VEMD were requested with duplicate presentations removed.

- The Rural Acute Hospital Database Register (RAHDaR) contains data for hospital-based rural emergency facilities across the study region. These include Colac Area Health, Camperdown Hospital, Lorne Community Health, Moyne Health Services, Otway Health & Community Services, Portland District Health, Terang Health Service, and Timboon District Health. RAHDaR includes data for most, but not all the smaller centres within the study region.

Data were obtained for all emergency presentations resulting from injury which occurred from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019. Data collected included sex, LGA of residence, “activity when injured”, “arrival transport mode”, “injury cause” and “place where injured.” All emergency presentations where “injury cause” had been recorded were included in the study. Injury cause included the following categories (code description): [1] Motor vehicle – driver, [2] Motor vehicle – passenger, [3] Motorcycle – driver, [4] Motorcycle – passenger, [5] Pedal cyclist – rider or passenger, [6] Pedestrian, [7] Horse related (fall from, struck or bitten by), [8] Other transport-related circumstance, [9] Fall – low (same level or less than 1 metre, or no information on height), [10] Fall – high (greater than 1 metre), [11] Submersion or drowning – swimming pool, [12] Submersion or drowning – other, [13] Other threat to breathing (includes strangulation and asphyxiation), [14] Fire, flames and smoke, [15] Scalds (hot drink, food, water, other fluid, steam, gas or vapour), [16] Contact burn (hot object or substance), [17] Poisoning – medication, [18] Poisoning – other or unspecified substance, [19] Firearm, [20] Cutting and piercing object, [21] Dog related, [22] Other animal related, [23] Struck by or collision with person, [24] Struck by or collision with object, [25] Machinery, [26] Electricity, [27] Hot conditions (natural origin, includes sunlight), [28] Cold conditions (natural origin), [29] Other specified external cause, [30] Unspecified external cause.

The “place where injured” field was used to categorise the emergency presentations into two groups: (i) farm-related injuries (place of occurrence – code F, Farm) and (ii) non-farm-related injuries (place of occurrence – all other codes). Since the average age of farmers is 58.8 years and older adults are at higher risk of significant morbidity following an injury, this study included individuals aged ≥50 years.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Since the VEMD and RAHDaR include different centres within the region, aggregate data from both were combined for analyses. The incidence rates of emergency presentations for injuries (expressed as per 1000 population per year) were standardised to the 2016 Australian population using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census.23 Incidence rates were calculated for (i) only farm-related emergency presentations for injury and (ii) all emergency presentations for injury.

Additionally, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics24 regarding occupation at the 2016 Census for residents of each LGA were used to calculate incidence rates of farm-related injuries, thus taking into account the numbers of agricultural workers. Agricultural workers were defined as those who reported Agriculture as their Industry of employment and their Occupation as one of the following: (i) Technicians and Trades Workers, (ii) Machinery Operators and Drivers and (iii) Labourers. The rates were calculated as number of injuries/number of agricultural workers and expressed as per 1000 population per year. Due to small numbers of farm-related injuries and number of agricultural workers per LGA, these incidence rates were not age-standardised to the Australian 2016 population.

All incidence rates were calculated for men and women separately, as well as combined. The proportion of farm-related injuries out of the total number of injuries was also calculated.

For other variables, including “activity when injured,” “arrival transport mode” and “injury cause,” data were reported for two groups: (i) farm-related injuries and (ii) non-farm-related injuries (i.e., all other injuries). These analyses were performed for all LGAs combined, since the numbers were too small to stratify by LGA, or by sex.

Data were analysed using StataSE 16 (College Station, TX; StataCorp 2019).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Whole study region

During 2017–2019, there were 31 218 emergency presentations for injuries by residents of the study region aged ≥50 years. Of these presentations, 1150 (3.68%) resulted from an injury occurring in a farm environment. For men, there were 15 553 emergency presentations, with 879 (5.65%) of these listing farm as the place of injury. For women, the total number of presentations was similar, at 15665, but the number of injuries occurring in a farm environment was lower (271, 1.73%).

The age-standardised incidence rate for all injury emergency presentations (men and women combined) across the entire study region was 67.4 (95% CI 66.6–68.1) per 1000 population per year. For men and women, the incidence rates were 71.9 (95% CI 70.7–73.0) and 63.4 (95% CI 62.4–64.4), respectively. For farm-related emergency presentations due to injury, the age-standardised incidence rate was 2.6 (95% CI 2.4–2.7) for men and women combined. For men separately, the incidence rate was 4.1 (95% CI 3.9–4.4) and for women it was lower; 1.2 (95% CI 1.0–1.3).

The incidence rates of farm-related injuries per 1000 population per year among agricultural workers across the whole study region were 170.0 (95% CI 159.8–180.5), 135.0 (120.4–150.8) and 160.2 (151.8–168.9) for men, women and men and women combined, respectively.

3.2 Local government areas

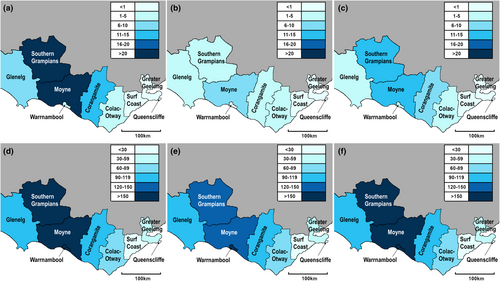

Table 1 shows the age-standardised incidence rates for both farm-related and all emergency presentations, stratified by LGA. Figure 2a–c show heat maps of age-standardised incidence rates for farm-related emergency presentations for injury. The highest incidence rates of farm-related emergency presentations occurred in the LGAs of Moyne and Southern Grampians. Both these LGAs are considered rural. In Moyne, the dairy industry is the dominant form of agriculture, with some sheep and cattle grazing and cereal crops. In the Southern Grampians, the pattern is of mixed agriculture. The lowest rates occurred in the LGAs of Greater Geelong, Queenscliffe and Surf Coast. These LGAs are not primarily agricultural; Greater Geelong, an urban centre, is the most populous LGA in the region, whereas Queenscliffe has the greatest numbers of retirees. Surf Coast is ranked highest in the region for socioeconomic status, and its main industries include tourism, electricity supply and building construction, with a smaller agriculture sector. The incidence rates of emergency presentations for farm-related injuries were also higher for men (Figure 2a) than women (Figure 2b) but followed a similar pattern for other LGAs. For women, Warrnambool, which is predominantly a rural city surrounded by the Moyne LGA, and the second most populous LGA in the study region, also had a low rate of emergency presentations.

| Local government area | Farm-related | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Males and females | ||

| Colac-Otway | 2.2 (1.6–2.7) | 64.2 (61.2–67.2) |

| Corangamite | 9.0 (7.8–10.2) | 106.1 (101.8–110.5) |

| Glenelg | 5.2 (4.3–6.0) | 104.1 (100.3–107.9) |

| Greater Geelong | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 36.6 (35.8–37.3) |

| Moyne | 15.6 (13.8–17.3) | 153.2 (147.9–158.6) |

| Queenscliffe | b | 25.9 (21.6–30.2) |

| Southern Grampians | 13.2 (11.7–14.7) | 161.4 (156.0–166.8) |

| Surf Coast | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 24.6 (23.0–26.3) |

| Warrnambool | 2.6 (2.1–3.1) | 175.2 (171.0–179.5) |

| Total | 2.6 (2.4–2.7) | 67.4 (66.6–68.1) |

| Males | ||

| Colac-Otway | 3.2 (2.2–4.2) | 67.7 (63.2–72.1) |

| Corangamite | 14.0 (11.8–16.2) | 114.3 (107.9–120.8) |

| Glenelg | 7.3 (5.9–8.8) | 106.5 (101.0–112.0) |

| Greater Geelong | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 39.5 (38.3–40.6) |

| Moyne | 23.9 (20.8–26.9) | 164.4 (156.6–172.3) |

| Queenscliffe | b | 25.6 (19.2–32.0) |

| Southern Grampians | 21.8 (19.0–24.7) | 176.3 (168.2–184.5) |

| Surf Coast | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 27.1 (24.6–29.5) |

| Warrnambool | 4.6 (3.6–5.6) | 180.9 (174.6–187.3) |

| Total | 4.1 (3.9–4.4) | 71.9 (70.7–73.0) |

| Females | ||

| Colac-Otway | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) | 61.1 (57.0–65.2) |

| Corangamite | 4.3 (3.1–5.4) | 98.4 (92.5–104.3) |

| Glenelg | 3.1 (2.2–4.0) | 101.7 (96.3–107.0) |

| Greater Geelong | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 34.1 (33.2–35.1) |

| Moyne | 7.3 (5.6–8.9) | 142.2 (135.0–149.5) |

| Queenscliffe | b | 26.4 (20.6–32.2) |

| Southern Grampians | 5.4 (4.1–6.7) | 148.4 (141.3–155.6) |

| Surf Coast | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) | 22.4 (20.2–24.6) |

| Warrnambool | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 170.5 (164.8–176.2) |

| Total | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 63.4 (62.4–64.4) |

- Note: Data presented as rate per 1000 persons per year (95% CI).

- a Standardised to the Australian 2016 Population.

- b No individuals in Queenscliffe presented for a farm-related injury.

For all emergency presentations, a similar pattern to the farm-related emergency presentations was observed (Figure 2d–f). The highest rates occurred in the more western LGAs of Moyne and Southern Grampians, as well as Warrnambool. LGAs to the east of the study region including Greater Geelong, Surf Coast and Queenscliffe had lower rates.

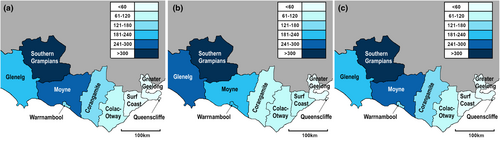

The incidence rates of farm-related emergency presentations among agricultural workers for each LGA are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. The patterns of emergency presentations were similar to those observed for injuries among all residents in each LGA. The highest rates of farm-related emergency presentations occurred in Moyne and Southern Grampians. However, in women, there were also high incidence rates in the LGA of Glenelg. The difference in incidence rates for farm-related emergency presentations between men and women was less pronounced when considering injuries among agricultural workers rather than all residents of each LGA.

| Local government area | Males and females | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colac-Otway | 79.1 (60.8–100.6) | 80.6 (59.2–106.7) | 75.1 (43.5–119.1) |

| Corangamite | 121.7 (105.8–139.0) | 133.9 (114.0–155.8) | 94.3 (69.6–124.2) |

| Glenelg | 222.7 (190.9–257.2) | 210.2 (174.3–249.8) | 259.3 (193.7–333.9) |

| Greater Geelong | 32.9 (23.8–44.3) | 36.7 (25.2–51.4) | 24.9 (12.0–45.3) |

| Moyne | 251.4 (227.0–276.1) | 268.2 (239.8–298.1) | 208.3 (167.5–254.0) |

| Queenscliffe | b | b | b |

| Southern Grampians | 353.3 (320.2–387.5) | 360.4 (322.8–399.4) | 327.6 (258.5–402.7) |

| Surf Coast | 53.8 (30.4–87.1) | 45.2 (19.7–87.1) | 68.6 (28.0–136.3) |

| Warrnambool | 177.4 (146.6–211.7) | 176.6 (142.6–214.9) | 181.0 (112.6–268.1) |

| Total | 160.2 (151.8–168.9) | 170.0 (159.8–180.5) | 135.0 (120.4–150.8) |

- Note: Data presented as rate per 1000 persons per year (95% CI).

- a Data for number of agricultural workers (Technicians and Trades Workers, Machinery Operators and Drivers and Labourers employed in the Agriculture Industry) obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.24

- b No individuals in Queenscliffe presented for a farm-related injury.

The proportions of farm-related emergency presentations by LGA are presented in Figure 4. The patterns observed are similar to those observed in Figure 2. The highest proportions of farm-related emergency presentations for injury occurred in the more western LGAs, particularly Moyne and Southern Grampians. Corangamite also had a higher proportion of farm-related emergency presentations, which has approximately one-third of the population employed in agricultural industries.

3.3 Additional information

3.3.1 Activity when injured

Most farm-related emergency presentations occurred while individuals were working for income (n = 398, 34.6%) or participating in other work (n = 349, 30.4%). Leisure was also reported as a common activity when individuals were injured (n = 217, 18.9%).

The activity when injured was different and more varied for all other emergency presentations. Leisure (n = 10 607, 35.3%), unspecified activity (n = 9153, 30.4%) and other specified activity (n = 3889, 12.9%) were the most common activities when the injury occurred.

3.3.2 Arrival transport mode

For both farm and non-farm-related emergency presentations, the most common methods of transport to the hospital or smaller centre were “other” (including private car) (farm: n = 958, 83.3%; non-farm: n = 19 898, 66.2%) and road ambulance service (farm: n = 183, 15.9%; non-farm: n = 9780, 32.5%). Individuals who sustained a farm-related injury were more likely to use “other” transportation than the non-farm injury group (p < 0.001).

3.3.3 Injury cause

For farm-related emergency presentations, there were several injury types that were most common, including “other animal-related injury” (excluding dog and horse; injuries from these animals are listed separately) (n = 232, 20.2%), “cutting, piercing object” (n = 224, 19.5%), “other specified external cause” (n = 173, 15.0%), “fall <1 metre (or no information on height)” (n = 151, 13.1%), and “struck by or collision with object” (n = 144, 12.5%). Machinery (excluding motor vehicles) was the cause of injury in only 20 cases (1.7%).

For non-farm-related emergency presentations, the injury causes differed. The most common injury cause was a “fall <1 metre (or no information on height)” (n = 10 546, 35.1%), “unspecified external cause” (n = 6639, 22.1%) and “other specified external cause” (n = 5506, 18.3%). Injuries caused by a “cutting piercing object (n = 2208, 7.3%)” and “struck by or collision with object” (n = 1518, 5.1%) were less common for non-farm-related emergency presentations compared to those identifying the farm as the place of injury (both p < 0.001).

4 DISCUSSION

The highest rates of farm-related injuries occurred in more rural LGAs (Moyne and Southern Grampians). For incidence rates taking into account the number of agricultural workers, patterns were similar. However, the differences between men and women were less pronounced. Many farm-related injuries occurred during work activities and patients were most likely to arrive at the hospital or smaller centre mainly by “other” transport, which includes private car, rather than by road ambulance. Many farm-related injuries were due to animals, cutting, piercing objects, falls and because a patient was struck by or collided with an object. Machinery was the cause of injury in only a small number of cases.

In this study, we observed a higher incidence of farm-related injuries among men. This has been reported previously in a study by Brumby et al.,25 showing that patients injured on a farm were more likely to be male compared to patients with injuries sustained in other places (75% vs. 58%, RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.26–1.35, p < 0.001). Franklin et al.26 also reported that 72.2% of individuals presenting to an Australian hospital for farm-related injury over a 12 month period were male. In another study by Lower et al.,27 males comprised 78.2% of hospitalisations for a farm-related injuries over a 4.5 year period in New South Wales. The Victorian Injury Surveillance Unit (VISU) has also published a report describing farm injuries across Victoria over a 3 year period.11 Of the 7259 ED presentations for farm-related injury during 2004–2006, 71% were for males. Additionally, a meta-analysis by Jadhav et al.28 showed that men were more likely to be injured in farm-related incidents than women (OR 1.68 95% CI 1.63–1.73). Another large Australian study has been published by the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, which examined hospitalisations for farm-related injuries across Australia during the 2010–2011 to 2014–2015 financial years.29 Although the publication describes hospitalisations rather than ED presentations, the patterns were similar to this study; of almost 22 000 hospitalisations from injuries that occurred on farms, 77% were male. In the state of Victoria, there are more men than women employed in an agricultural occupation; 68% of workers are male14 and thus it is not unexpected that men experience a higher number of farm-related injuries. However, incidence rates for fall-related emergency presentations among agricultural workers showed a smaller difference between men and women. This could indicate that both sexes are at risk of farm-related injury, and the higher rates among males may be due to the higher number of male compared to female agricultural workers.

In this study, we identified several common injury causes, specifically animals, cutting/piercing objects, falls <1 metre and struck by/collision with objects. These data are useful for focussing future studies investigating specific injury causes. Other Australian studies have also reported common causes of farm-related injuries, with the most frequent being machinery, transport and animal related.2, 11, 27, 29 It is important to target preventions towards these causes of injury because they have both been associated with a higher risk of hospitalisation and severe injury.4, 11, 30, 31 Other common causes of farm-related injuries included cutting/piercing objects, falls and being struck by objects.1, 2 Our results are largely similar to previous literature, but we observed few farm-related injuries resulting from machinery or other vehicles. It is possible that adequate safety mechanisms have been effective at reducing injuries from these specific causes. It is also possible that injuries due to machinery were included in other categories such as cutting/piercing objects, falls, or being struck by objects. However, the VISU publication11 also reported small numbers of machinery-related ED presentations for farm-related injuries (2%). Further work is needed to explore the cause of injury in greater detail to help guide preventative strategies.

In this study, we reported that most individuals (83.3%) who sustained a farm-related injury chose to arrive at the hospital by “other” transport (mainly private car), which could be a potential target for education and awareness strategies, encouraging individuals who sustain farm-related injuries to use health services including road ambulances. This has also been observed in other studies from Victoria, Australia. For example, Brumby et al.25 reported that the majority (83%) of patients presenting to the Emergency Department of a Victorian regional hospital during 2010–2015 arrived by private car. Another study by Adams et al.32 used data from RAHDaR to examine emergency presentations of farmers and non-farmers during high heat days, reporting that 82.4% arrived by “other” transportation (including private car). However, it is also possible that the majority of incidents occurring in this study were non-life threatening and therefore a road ambulance was not required. Unfortunately, information concerning the severity of injury was not available in this study and we were unable to investigate this further. Additionally, in rural areas, transportation by private car may be a quicker method of arriving at the hospital compared to a road ambulance.

Prevention of farm-related incidents and injuries is important, and the method of selecting the most appropriate prevention strategies are outlined in the Hierarchy of Risk Controls published by Safe Work Australia.15 The hierarchy describes that the most effective prevention strategy should be implemented first if practicable, then following an ordered list of alternative options. Specifically, hazards should be eliminated if possible, as this is the most effective option. Following this, the hazard should be substituted (e.g. using different equipment with a lower risk of injury), isolated (e.g. keeping people away from the hazard) or engineering controls should be used to minimise the risk. Less effective prevention strategies are then considered, including administrative controls to reduce exposure to the hazard, or personal protective equipment, the latter of which relies on individuals to consistently and correctly use the equipment. One example includes the National Centre for Farmer Health33 suggestions for preventing falls in a farming environment such as avoiding heights, using safety harnesses, keeping work spaces tidy and wearing appropriate non-slip footwear. Another example is described by Lower et al.31 regarding the use of quad bikes, which can roll over and cause injuries. If possible, the hazard should be eliminated or substituted (e.g. remove quad bikes from the farm or use a different vehicle with a lower risk), followed by engineering controls such as crush protection devices to reduce risks if the vehicle rolls over. Additionally, administrative controls such as removing passengers, loads and spray tanks from quad bikes, as well as providing appropriate training, supervision and personal protective equipment can also reduce the risk of injury. The current study can help develop further prevention strategies and informs the WorkSafe Victoria Agriculture Strategy 2020–2023 by providing contemporary and more complete data for the Barwon South West region.

This study has several strengths and limitations. One major strength was that we combined data from the VEMD and RAHDaR to provide a more complete description of farm-related injuries across the study region. Some strengths of the study include we were able to capture most of the major injuries occurring in the region, as these would likely be transferred to one of the larger hospitals (Geelong, Hamilton, or Warrnambool). This may have resulted in some duplicate presentations, however, the data obtained from the VEMD were provided with duplicates removed. Additionally, the data derived from the VEMD are good quality since reporting is mandatory.11, 34, 35 Furthermore, the data from the smaller centres in the region are also likely to be accurate since it has been shown they are able to manage acutely unwell patients17 and collect high-quality data.36 In this study, we were also able to calculate age standardised rates for injuries, as data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics were available to provide the total populations by LGA. We were also able to calculate incidence rates among agricultural workers in the region to provide more information about the individuals who are likely to be experiencing farm-related injury. Additionally, the study region contained LGAs with different characteristics, including a mix of rural towns, agricultural areas and urban areas. This study allows monitoring of farm-related injury rates across the region, which is a goal of the WorkSafe Victoria Agriculture Strategy 2020–2023 report. Some limitations of the study include that the data were not collected for general practitioner presentations, those to private hospitals, or those treated at home, and thus the results here are likely to be underestimated. There were too few farm-related injuries to stratify the results for “activity when injured,” “arrival transport mode” and “injury cause” by LGA and sex. Additionally, due to small numbers, it was not possible to age-standardise the data regarding agricultural workers from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.24 Perturbations have also been applied to these data, to protect confidentiality of individuals. This increases or decreases the true values by a small amount and overall these minor differences do not introduce any bias, but may have affected our results describing incidence rates taking into account the number of agricultural workers by LGA. Additionally, the data are reported by usual place of residence and this may not be where the farm-related injury occurred, as a person's workplace may be in an adjacent LGA. There are two smaller centres located in the LGA of Glenelg that are currently not included in RAHDaR (Casterton and Heywood) and the lack of data for these smaller centres may have affected the results. It is also possible that injuries were not coded correctly and thus some may have been missed.34, 35 For example, a previous study indicated that injuries occurring on a farm may be coded as occurring at home, as farms are both workplaces and homes and the distinction often becomes blurred.37, 38 This may also result in family members performing some work without adequate training, leading to a higher risk of injury. In addition, a study by Adams et al.32 reported that heat-related injuries are often not coded using the specific ICD-10 codes. Farm-related injuries can also be under-reported as many farmers accept that the work can be dangerous and that injuries are inevitable rather than preventable.14, 39 In addition, this study did not determine the injury types (e.g. fractures), or data for treatment such as referrals or discharge summaries. We also did not have data regarding the specific agents or mechanisms of injury, and were unable to investigate causes of injury further than the broad categories described. Finally, the results from this study may not be generalisable to other regions or populations, but the study does provide a profiling model that can be used to perform similar analyses in other geographical areas.

This study has provided data regarding farm-related injuries for the Barwon South West region in western Victoria. Age-standardised rates across nine LGAs were provided to show where farm-related injuries were most frequent. Most injuries occurred in men. Many injuries occurred during work activities and involved animals, cutting/piercing objects, falls or being struck by/colliding with an object. These types of injuries are likely to occur during routine tasks in a farm environment such as animal husbandry and production tasks (e.g. milking cows, shearing sheep and handling cattle), using sharp tools or machinery and lifting heavy loads such as hay bales. The results of this study provide comprehensive local data to assist with planning and prevention of farm-related injuries, as well as providing a profiling model for studies in other geographical regions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kara L. Holloway-Kew: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing – review and editing; writing – original draft. Timothy R. Baker: Data curation; investigation; project administration; resources; writing – review and editing. Muhammad A. Sajjad: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Tewodros Yosef: Writing – review and editing. Mark A. Kotowicz: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition. Jessie Adams: Writing – review and editing. Susan Brumby: Writing – review and editing. Richard S. Page: Writing – review and editing. Alasdair G. Sutherland: Writing – review and editing. Bianca E. Kavanagh: Data curation; investigation; writing – review and editing. Sharon L. Brennan-Olsen: Writing – review and editing. Lana J. Williams: Supervision; writing – review and editing. Julie A. Pasco: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; resources; supervision; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was funded by the Western Alliance Academic Health Science Centre, a partnership for research collaboration between Deakin University, Federation University and 13 health service providers operating across western Victoria. KLH-K is supported by an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship; MAS is supported by a Centre for Innovation in Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Treatment Strategic Research Centre (Deakin University) stipend; TY is supported by a Deakin University Postgraduate Research Scholarship (DUPRS); LJW is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leadership Fellowship (1174060). We acknowledge the Centre for Victorian Data Linkage at the Victorian Department of Health for the provision of data linkage and the Victorian Department of Health as the source of the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset. We also acknowledge the contribution of the Rural Acute Hospital Database Register for data from the smaller centres across the study region. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley - Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

SB is an Associate Editor of Australian Journal of Rural Health. All other authors have no conflict of interest of relevant disclosures to declare.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This research was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Barwon Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (reference no. 15/11). Data received from the VEMD and RAHDaR were de-identified.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Victorian Minimum Emergency Dataset and Rural Acute Hospital Database Register. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of the Victorian Minimum Emergency Dataset and Rural Acute Hospital Database Register.