Challenges and strategies to improve the provision of end-of-life cancer care in rural and regional communities: Perspectives from Australian rural health professionals

Abstract

Objective

To identify challenges and strategies to improve the provision of end-of-life (EOL) cancer care in an underserved rural and regional Australian local health district (LHD) from the perspective of general practitioners (GPs) and specialist clinicians while exploring the benefits of adopting a generalist health care approach to delivering EOL care in rural and regional communities.

Setting

Rural and regional Australia.

Participants

General practitioners and palliative care and cancer care specialists (medical and nursing) involved in the provision of EOL care to people with advanced cancer in the rural and regional areas of an Australian LHD.

Design

Qualitative descriptive study involving 22 participants in four face-to-face and online focus groups. Thematic analysis of the transcripts identified key issues affecting EOL care for people with advanced cancer in rural and regional areas of the LHD.

Results

Four themes including geographical remoteness, system structures, medical management and expertise and training emerged from the focus groups. Key barriers to effective EOL care included insufficient remuneration for GPs and other clinicians (especially home visits), resource limitations, limited community awareness of palliative care and lack of confidence and training of clinicians. Continuity of care was identified as an important facilitator to effective EOL care. Participants suggested greater Medicare rebates for palliative care and home visits, adequate equipment and resources, technology-enabled clinician training and greater rural-based training for specialist PC clinicians may improve the provision of EOL care in regional and rural communities.

Conclusions

Rural-based clinicians delivering EOL cancer care appear to be disproportionately affected by geographical challenges including resource and funding limitations. A multi-pronged strategy aimed at greater interdisciplinary collaboration, community awareness and greater resourcing and funding could help to improve the provision of EOL care in underserved rural and remote communities of Australia.

What is already known on this subject

- Inconsistent provision of end-of-life care across Australia, particularly in regional, rural and remote areas remains a public health challenge. A generalist approach promoting greater integration of primary care and hospital settings may help to improve the availability and accessibility of EOL care in rural and remote communities.

What this paper adds

- This paper explores the experiences of Australian GPs, palliative care and cancer care specialists (medical and nursing) delivering end-of-life care to advanced cancer patients living in rural and remote communities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Approximately one-third of Australia's population live in rural and regional areas; unfortunately, the end-of-life (EOL) care needs of advanced cancer patients in these communities are not being adequately met with the gap between the supply and demand for EOL care services continuing to widen.1 This is not a problem unique to Australia. Ensuring equitable access to EOL care services for rural and regional cancer patients and carers has been identified as a health system priority in many nations2, 3 and remains an issue requiring further investigation.4

In urban areas, EOL care is usually provided by a multidisciplinary team comprising of general practitioners (GPs) and palliative care specialists (medical and nursing).5 However, in rural and regional communities where health care accessibility is more limited due to workforce shortages and vast geography,6 many patients have limited access to palliative care specialists and are therefore reliant on GPs and other generalist clinicians for their EOL care needs. With GPs often well-placed and committed to delivering this care in their rural communities,7 research shows generalist-led palliative care under the leadership from a specialist palliative care (SPC) team to be a relatively effective method of improving the provision of EOL care services available for patients and their families.8 Although this approach of promoting greater generalist and specialist interdisciplinary collaboration has been found to improve the coordination of care,9 reduce acute care service usage10 and increase the likelihood of patients dying at home in line with their wishes,11 many GPs remain unsure about the scope and consistency of providing EOL care in rural and remote areas.12-14 As rural GPs face a number of challenges when providing EOL care, including limited resources,15 lack of training16 and inadequate remuneration12 a focus ought to be placed on developing and implementing methods to address these challenges in both the primary care and hospital settings to improve the accessibility of EOL care to all terminal patients in rural and remote communities.

As cancer and palliative care specialists (medical and nursing) are often involved in at least the early stages of EOL care to rural patients, capturing the perspectives of these specialists along with GPs may help to provide greater insight into the challenges and opportunities of improving EOL care provision across both primary care and hospital settings. Much of the current research has focused on the perspectives of GPs delivering EOL care with few exploring the perspectives of SPC and cancer care services. Our study focused on a local health district (LHD) in Australia that spans across rural and regional geographies. GPs from this region are able to connect with SPC and oncology teams when providing EOL care. Despite this, many GPs and their rural-based patients continue to face barriers in the accessibility of EOL care. To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide a comprehensive picture of the complex challenges faced by GPs and cancer and palliative care specialists (medical and nursing) involved in EOL cancer care in the rural and regional regions of an Australian LHD. The aim of this study was to: (1) identify the challenges that clinicians encounter when delivering EOL care in underserved rural and regional communities of Australia, (2) explore the benefits of adopting a generalist approach to delivering EOL care in rural and regional communities and (3) identify strategies to improve the provision of EOL care for advanced cancer patients living in rural and remote communities from the perspective of generalist and specialist health professionals.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and participants

Qualitative exploratory methodology involving focus group interviews was used to capture the views of health professionals working with advanced cancer patients. Promoting synergy and spontaneity, online and face-to-face focus groups were chosen over individual interviews because of their ability to encourage participants to clarify their views, voice their opinions and share their experiences that might not surface during individual interviews.17 Health professional participants were asked about the current state of EOL care and how the accessibility and delivery of EOL care can be improved in rural and regional areas. Health professionals were included if they: (1) cared for people with advanced cancer; (2) willing to participate in the interview; and (3) able to provide informed consent. Spread across the LHD, a general practice, a LHD research network of GP's and two hospital-based palliative care and oncology specialist teams were identified and approached via professional networks of the researchers. Recruitment occurred via email and participants were provided a study information sheet and consent form. The focus group interviews were conducted independently by the lead researcher via video conferencing (Zoom) and in-person at the general practice and hospital.

2.2 Data collection

To achieve maximum variability of data from various contexts to better understand the research question,18 a purposeful sampling strategy was used to identify experienced health care professionals with different medical disciplines involved in the delivery of EOL cancer care; oncology, SPC and general practice were captured. Researchers selected participants with variability across gender, medical speciality and years of experience (Table 2). As recommended by Guest, Namey19 four focus groups were undertaken as the most prevalent themes were identified within this sample size. Focus group interview questions adhered to an interview guide (Table 1). Focus group sessions were audio recorded using a Dictaphone or electronically using zoom software. All participants provided verbal consent prior to the interviews.

| 1. Can you tell me about the delivery of health care to cancer patients at end of life in the Local Health District? (What do you think about the consistency across the region? Do you think patients know what is available to them and where? Do you think the approach to the delivery of these services is well coordinated?) |

| 2. How does travel times and distance to health services affect health care in cancer patients at end of life? (Is the travel times to various services a barrier to cancer patients at end of life accessing and using health care services? Are there certain patterns of behaviour you have seen with patients apprehensive to use a service because of the location of that service?) |

| 3. Our analysis of data from the local health district revealed that cancer patients in more rural areas tended to underutilise specialist palliative care services in favour of acute health services. What do you think might be the reasons for this? (What can be done differently? What can health services/providers/carers do? What about across different cancer types?) |

| 4. What is the role of general practices in delivering EOL cancer care in rural locations? (Are there any foreseeable obstacles? What can be done about these?) |

| 5. Do you have any other suggestions to improve the provision of health care for individuals with cancer nearing the end of life? |

| 6. Is there anything else you want to add to what we have discussed? |

2.3 Data analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised using Sofix software. Using Clarke and Braun's inductive data analysis process,20 transcripts were thematically analysed with constant reflection and debriefing within the research team to support the dependability and credibility of the analytical process.21 Three members of the research team (X, Y, Z) reviewed samples of the transcripts X (100%), Y (50%) and Z (50%) and derived themes from the data independently. Data including field notes were analysed across the whole sample, which allowed for case comparisons and the meta-synthesis of all qualitative data to inform main themes. Findings were then discussed between the three researchers until a consensus was reached. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist22 was used to report on the study process.

2.4 Ethics approval

This research received approval from the Health and Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong (Reference: 2020/ETH00313).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

A total of 22 health professionals including; general practitioners (GPs) (n = 10), palliative care specialists (n = 5), medical oncologists (n = 5), a respiratory physician (n = 1) and a nurse practitioner (n = 1) participated in this study. Majority were female (59%) with a median age of 50 years. The number of years working in their current role ranged from 1 to 40 years and the mean duration of focus groups was 50 min (Table 2).

| Participant number | Focus group | Gender | Age | Current role | Number of years of experience in this role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Female | 54 | GP | 27 |

| 2 | 1 | Female | 57 | GP | 30 |

| 3 | 1 | Male | 67 | GP | 40 |

| 4 | 1 | Male | 58 | GP | 30 |

| 5 | 2 | Female | 31 | GP | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | Female | 37 | GP | 4 |

| 7 | 2 | Female | 31 | GP | 2 |

| 8 | 2 | Female | 66 | GP | 35 |

| 9 | 2 | Female | 68 | GP | 30 |

| 10 | 2 | Female | 28 | GP | 1 |

| 11 | 3 | Female | 38 | PC&C Specialist | 7 |

| 12 | 3 | Female | 46 | PC&C Specialist | 13 |

| 13 | 3 | Male | 38 | PC&C Specialist | 3 |

| 14 | 3 | Male | 35 | PC&C Specialist | 2 |

| 15 | 3 | Male | 66 | PC&C Specialist | 29 |

| 16 | 3 | Female | 60 | PC&C Specialist | 8 |

| 17 | 4 | Female | 28 | PC&C Specialist | 1 |

| 18 | 4 | Male | 67 | PC&C Specialist | 32 |

| 19 | 4 | Female | 40 | PC&C Specialist | 3 |

| 20 | 4 | Male | 35 | PC&C Specialist | 4 |

| 21 | 4 | Male | 68 | PC&C Specialist | 35 |

| 22 | 4 | Male | 71 | PC&C Specialist | 40 |

- Abbreviations: GP, General Practitioner; PC&C Specialist, Palliative Care and Cancer Specialist.

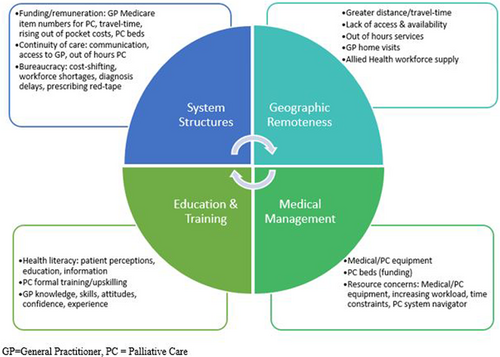

Four themes emerged: system structures, geographical remoteness, medical management and expertise and training. The themes overlapped and a summary of main themes are presented in Figure 1. Participants often described barriers to the provision of EOL care; fewer participants discussed facilitators of good-quality EOL care. Participants also proposed suggestions for improving the provision of EOL care in rural areas of the NSW LHD (Table 3).

| Themes | Strategies for improving rural-based EOL care |

|---|---|

| Geographical remoteness |

|

| Medical management |

|

| Education and training |

|

| System structures |

|

To protect the participants' identity, the professional background of the palliative care specialists, medical oncologists, respiratory physician and the nurse practitioner will be reported as ‘palliative care and cancer specialist (PC&C specialist)’.

3.2 Health care system structures

The health care system structure was identified as being of vital importance in the provision of EOL care to advanced cancer patients across primary care and hospital settings. Several organisational level issues influenced the accessibility and delivery of EOL in the LHD. These are described below.

3.2.1 Funding and remuneration

…the clients of our service are spread up and down the coast. Travel is time consuming and it's not remunerated. You're basically losing money when you do home visits for palliative care as a GP. [FG2, GP8]

GP's have to be paid for their equipment and their time and their expertise. That's why GP's often just flick it all off to the hospital because they know they've got all the equipment, all the drugs and it won't cost the patient anything. [FG1, GP4]

3.2.2 Continuity of care

The advantage of a setup like that is that GP's look after the patients in the practice and cover the hospital as well with the option to refer to or consult with the specialists in the big centre an hour away. The patients get a very good service, a lot of them in the last days get admitted to the hospital and given the final treatment in the hospital and pass away there. [FG2, GP6]

If they're admitted, the discharge summary is not arriving and we don't always receive letters back from the outpatient's clinic. Some of them are good and some of them are not. Communication is core. [FG2, GP7]

Moving towards more e-health and e-communication is great for referrals in and referrals back from all the hospital services. There are often big-time lags with getting information about the patients, up to 3 months. If the patient doesn't know what their treatment is or has forgotten their treatment folder, it's hard as a GP then to manage. [FG1, GP1]

So even if they want to die at home, they can't because they don't have the services that are adequate to support that sometimes. [FG1, GP3]

They [cancer patients] haven't been able to get appointments at practice easily and we'd like to be able to…it's about funding for general practice, Medicare, shortage of GP's. [FG2, GP9]

The difficulty is the after-hours palliative care. The palliative care service is terrific but where it's fallen over has been during the middle of the night or over the weekend where the only contact available would be through casualty. [FG2, GP5]

…we have in theory, telephone advice from the ward available to the region over night, but it's rarely utilised. [FG3, PC specialist 15]

3.2.3 Bureaucracy

And we don't even know who their boss is. If you ask me who my boss is, I don't really know who it is. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 22]

They cost shift between each other and it stops any progress. If you get chemotherapy inside this hospital, the state government pays for it. If you get chemotherapy in the cancer centre, the federal government pays for it. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 18]

There is a move from state level to do co-commissioning to set up projects where they've identified this is cheaper to do it outside the hospital than in. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

They can't get in to see their GP and the GPs are scared of prescribing narcotics. Getting access to the drugs is a real pain. You can give a 1-month supply and you've got to make the poor patient come back every month to get another lot of scripts because you can't give him a repeat. I worry that some people can miss out. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

3.3 Geographical remoteness

Key geographical-based factors affecting the delivery and accessibility of EOL care in the LHD included distance and travel time barriers to access SPC services and resource and workforce shortages in rural and remote regions.

3.3.1 Distance and travel time

What we do know for sure is that once you're 80 kilometres away from a cancer centre, the radiotherapy referral rates halve. [FG4, PC&C specialist 18]

Inpatient SPC services isn't viable because of the tyranny of distance for our patients down here, it's an hour plus drive for families to go and visit. [FG4, Medical Oncologist 21]

We had the highest mastectomy rate in the state and further [away from urban area] you went, the mastectomy rate was even higher. Young women can have 6 weeks of radiation where you've got to travel 100 km every day or you can have a mastectomy and you won't have to have that. So a lot of them elected to have their breast removed rather than having radiation… [FG4, PC&C specialist 21]

3.3.2 Resource concerns

… on a population level, we have <50% of the palliative care specialists that we should within the LHD. We are less than four full-time equivalent and should be between eight and nine. [FG4, PC&C specialist 20]

We've got a big geographic area, patients have difficulty accessing services and there's no after-hours service. We have an absolute lack of palliative care resources, we've virtually got to be at death's door before we can get a patient into palliative care. [FG4, PC&C specialist 21]

It's very short on the ground and patients don't have a regular GP. There's no continuity of care, nobody does home visits. [FG1, GP 7]

I've got terminal patients with end stage cancer but will be around for 12 to 24 months. They're not going to improve they're only going to deteriorate, yet they would benefit from physiotherapy treatment. It's a real challenge to get domiciliary physiotherapy services for these people. [FG4, PC&C specialist 21]

The last person I was involved with palliative care was after the telehealth items came in. It was very helpful to me because I was still able to bill them for things that I did after-hours. [FG4, PC&C specialist 21]

3.4 Medical management

Issues relating to access to SPC medical equipment and medication, access to SPC beds and patient navigators were described by the participants.

3.4.1 Medical equipment and medication

…some of the drugs we use in palliative care are not on the PBS. We also have to involve the palliative care team to set up a syringe driver. We don't have a kit to do it ourselves. Its equipment like a syringe driver and the drugs to go in it that we can't have in our doctor's bag because it's too expensive. That could be a PBS thing where they have a palliative care kit and end of life care in a box. [FG2, GP 8]

3.4.2 Access to SPC beds

…our entire district is under resourced bed-wise, and palliative care beds just disappear because of our acute patient load. [FG4, PC&C specialist 17]

…specialist beds would be nice, but what would they look like? Adapting rather than just transposing what works in a metropolitan area to a completely different context is important to consider. [FG3, PC&C specialist 12]

3.5 Education and training

…we're trained to work in metro areas and it's a huge shift to start working in rural areas. It's one thing to be able to do it in Sydney [Metropolitan area], it's a whole other thing to be able to do it in a rural area. [FG3, PC&C Specialist 12]

3.5.1 Medical professional skills and confidence

They might not have had a difficult palliative care discussion with a family for 5 years, they would have lost the skill. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

There's not a lot of knowledge from patients and their families about the capacity of how palliative care services assist. Some hospital medical staff also have a higher expectation of what we can offer than what realistically is available. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

3.5.2 Patient awareness

Education, education, education. People have this anonymity about palliative care. People think, oh they're just going to give you morphine and send you off to happy days. That's what we have to change. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

Disadvantaged people often do less well because they can't navigate the system. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 19]

…having navigators working with the community, palliative care and all these patients would be ideal. It could be a role for a social worker or other allied health professionals [FG2, GP 6]

…if they've been hooked up to the palliative care team, they seem to get all the numbers from the nurses there and the specialists and be told about the hotline so those patients seem to be pretty knowledgeable. [FG4, PC&C Specialist 21]

4 DISCUSSION

This study is one of the first to explore the complex challenges faced by GPs and palliative care and cancer care specialists (medical and nursing) involved in the provision of EOL care to people with advanced cancer in the rural and regional areas of an Australian LHD. Key interdependent themes revealed through analysis are summarised in Figure 1. According to our study, resource limitations and insufficient funding structures impede GPs and other generalist health professionals' provision of quality and timely EOL care to rural and regional patients. Health system issues including perceived cost-shifting between levels of government, overly restrictive opiate prescribing regulations, lack of community awareness and lack of clinician training were also identified by our participants as significant barriers to high-quality EOL care in rural and regional areas in the LHD. Adequate time, equipment and resources including organisational support were considered essential ingredients for high-quality EOL care. Participants in our study identified optimal EOL care as being a seamless collaboration between palliative care and cancer services, general practices, allied health professionals, patients and their loved ones. While most participants were pleased with the coordination and delivery of EOL across the region, many still found it difficult to deliver this care to patients in rural and regional areas.

Consistent with a previous study from Western Australia,13 the current study identified geographical remoteness and insufficient funding for home visits as important barriers to the delivery of EOL care. Although many rural GPs consider EOL care as a core function in their clinical practice, many find it difficult to deliver quality care to their rural patients because of increased workload and time constraints.23 The Medicare rebate for round-trip travel time during a home visit by a GP is a flat $27.85,24 irrespective of the travel time; the situation is even worse for non-GP specialists and other clinicians who do not have access to any travel remuneration from Medicare. Clearly, the situation needs to be addressed urgently, especially given the vast geographical distances that characterise rural and regional Australia and the unmet EOL care needs of rural patients. Three changes to Medicare could encourage more clinicians to undertake home visits as part of EOL care: first, an increase in the travel component of the home visit item numbers for GPs; second, increasing non-GP specialists (medical and nursing) home visit items to reflect the travel time (and resources); and third, structuring the travel component of the home visit item numbers so that the rebate amount scales with the patient's geographical distance from the clinic.

Resource limitations in rural areas including access to medical equipment, medication and palliative care beds were also discussed as barriers to EOL care in the current study. Participants described the importance of timely administration of medications to provide symptom control to EOL patients, and how poor EOL care could arise from restricted access to palliative care medications. Given the importance of community-based or home-based EOL care in rural communities, one of the key challenges rural clinicians face is the timely initiation of medications for symptom control.25 Our participants recommended the creation of special authority codes to enable rural GPs to prescribe greater number of repeats for selected palliative care medications; this could potentially reduce distress and suffering that could be experienced by patients who are not able to get a timely appointment with their doctor for medications especially if their symptoms worsened acutely. Taking the anticipatory prescribing concept further is the “Rural EOL Doctors kit” as suggested by a participant, containing medical equipment such as syringe drivers. Collaboration with rural pharmacies to dispense, assemble and store such kits might help to capitalise on the locality and develop collegial support between GPs, improve interoperability of information between hospitals, general practices and pharmacists.26 Rural EOL Doctors kits may also help to better equip GPs to assist in the timely administration of pain relief, the overall provision of EOL care in rural areas and reduce the travel burden rural patients face to access palliative care in the last months of life.

Previous studies have identified an integrated team approach to EOL care to be a key enabler in the provision of high-quality treatment and care for advanced cancer patients.27 As patients with advanced cancer often require complex care across multiple domains,28 our participants discussed the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in which medical and allied health care professionals work collaboratively. An expansion of the Medicare Chronic Disease GP Management Plan29 or introduction of a Medicare EOL management plan to include additional allied health services was suggested by some participants as a facilitator for multidisciplinary collaborative care. Opening the Medicare EOL management plans up to GPs, palliative care and cancer care specialists could promote interdisciplinary collaboration, further streamlining the accessibility of EOL care services for patients, irrespective of their point of contact with a GP or specialist clinician. The expansion of the number of allied health services claimable as part of an EOL management plan would also encourage more allied health providers to establish practices in rural and regional communities, contributing to increased specialised services that meet the needs of rural patients dying with cancer from a holistic manner.

Our study also reported variations in the levels of expertise and confidence by GPs and specialists (excluding palliative care and cancer care specialists) involved in the delivery EOL care in rural areas. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing low levels of confidence, variable interest and training in palliative care by Australian GPs,30 and limited education that GPs and specialists have in out-of-hours care,31 symptom control32 and counselling needs of patients.33 To overcome these issues, participants described strategies not dissimilar to those previously reported by Pelayo, Cebrián34 such as greater investment in palliative care upskill training delivered via distance learning and the inclusion of rural-based placements in advanced training in specialist palliative medicine. Fostering greater support between palliative and cancer care specialists and generalist doctors and tailoring palliative care training to incorporate technology-based learning and rural immersion could help to better support doctors to meet the challenges of delivering EOL care in rural and remote communities.

General practitioner and specialist participants also identified low levels of awareness of local resources as a barrier to providing quality EOL care. The development of an area-specific directory of local palliative care resources and services was suggested by the participants; this is not a new concept but has been previously proposed by other researchers13, 35 and has been implemented through initiatives such as the HealthPathways,36 albeit in a patchy manner. Greater funding will ensure local implementations of HealthPathways to be consistently high quality and remains current. And finally, increased funding for EOL patient navigators as part of a multidisciplinary palliative care team in rural areas of the LHD was described by the GP and specialist participants as providing an additional source of education and support to patients and families during the EOL phase, especially for those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Although this study focuses on localised health issues, many of the same geographical-based challenges are also experienced by other health care providers in other rural and regional areas. To a greater extent, many issues are also experienced among primary care health services operating in remote areas where SPC services may not be available due to greater remoteness and significantly smaller patient populations. A strength of this study lies in the multidisciplinary composition of the focus groups. The results provided us with a broader insight into the different perspectives of clinicians delivering EOL care in primary care and hospital settings. It is also possible, however, that the GPs who participated in this study may have had a special interest in EOL cancer care and therefore provided insights that are different to clinicians with less interest. While the size and heterogeneity of the study sample allowed for valid and comprehensive data collection, future studies involving a larger sample size representation from each of the professional categories involved in palliative care in primary care would help to further support the rigour of analysis.37

4.2 Conclusions

This study demonstrates EOL cancer care as an essential service in rural and regional communities of Australia, yet patients, their loved ones, and generalist and specialist clinicians involved in the provision of EOL care face additional challenges distinct from those in urban areas. A more integrated health care system with greater generalist and specialist interdisciplinary collaboration could help to improve the provision of EOL care in underserved rural and regional communities. Additional technology-enabled education and support, adequate equipment, resources and remuneration could assist more rural-based GPs to take on an expanded role in EOL care, with support from palliative and cancer care specialists (medical and nursing). Findings from this study can help to inform policies aimed at addressing disparities in the provision of EOL care in regional and rural communities of Australia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jessica Cerni: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – original draft; methodology; writing – review and editing; project administration; formal analysis; validation; visualization; software; funding acquisition; data curation. Joel Rhee: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; supervision; resources; methodology; project administration; validation. Hassan Hosseinzadeh: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; supervision; resources; project administration; validation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the health professionals who kindly provided their time and expertise in participating in this research. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley - University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This research received approval from the Health and Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong (Reference: 2020/ETH00313).