Living with dementia in regional Australia: The experience of acute care hospital management from the carer's perspective

Abstract

Introduction

Family carers play a crucial role in dementia care. As the condition progresses, people with dementia become increasingly dependent on their carers for all areas of daily living. The risk of carer burnout is significant. One of the more stressful events for family carers is when hospital admission is required for the person they care for. Living in regional Australia adds complexity to the experience. Hospital and health services in regional Australia could use a greater understanding of the issues associated with hospital care to inform patient and carer management, improve outcomes for this population and support the goal of ‘ageing in place’.

Objective

To explore the experience of carers of people with dementia in regional Australia when hospital care or treatment was required for the person they provide care for.

Design

Six family carers living in regional Australia participated in this interpretative phenological study. Individual, semistructured interviews were held and transcribed verbatim shortly after. Data analysis occurred via three key processes: reading and highlighting, coding and grouping, which yielded the major themes and subthemes of the study.

Findings

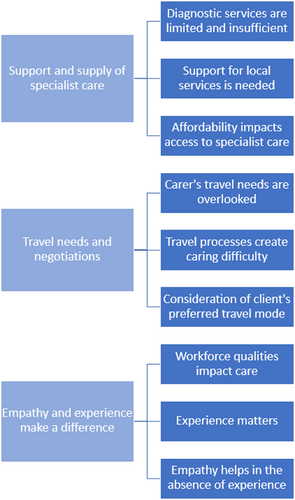

Three major themes and nine subthemes emerged from data analysis. The major themes were: (i) support and supply of specialist care; (ii) travel needs and negotiations; and (iii) empathy and experience make a difference.

Discussion

Findings from this study highlight aspects of care that healthcare providers can address to improve outcomes for patients with dementia and their carers. Carers need opportunities to seek clarification and provide input on care plans. Good communication, involvement and relationship building between healthcare staff and carers are vital to achieving optimal patient outcomes. Staff training supporting understanding of appropriate dementia care is essential for improved patient and carer outcomes.

Conclusion

Factors related to regional location, including lack of specialist care and support, compound carers' challenges. Healthcare provider education on dementia care and dementia-friendly processes in hospitals will support optimal patient and carers outcomes.

1 What this paper adds

- Patients with dementia and their carer need to be considered a dyad in relation to the hospital experience to optimise patient and carer outcomes.

- Hospital healthcare providers need training in dementia care to ensure the care provided is appropriate and acceptable.

- Hospital processes should be patient-centred and dementia-friendly to support patients with dementia and their carers during acute hospital admissions.

2 What is already known on this subject

- Hospital admission of a person with dementia is a highly stressful experience for both the person with dementia and their carer and is associated with poor patient outcomes.

- Specialist support within hospitals and the community is limited in regional Australia for individuals with dementia and their carers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a challenging and life-changing condition with substantial effects on the individual and their families. Dementia is the second leading cause of death among Australians.1 It is estimated that in 2020 between 400 000 and 459 000 Australians were living with dementia, affecting mainly those over 65 years; this rate is expected to increase significantly with our ageing population.2 Aged Care Services and subsidies by the Australian Government have evolved since 1963, with a recent, steady decline in demand on permanent residential aged care and growth in the utilisation of home care packages to support ‘ageing in place’.3 Support from a family carer positively affects the quality of life for the person living with dementia and delays their need to move into permanent residential aged care.4 Consequently, family carers play a crucial role in dementia care. As the condition progresses, people with dementia become increasingly dependent on their carers for all areas of daily living. The risk for carer burnout is significant; when compared with caring for a relative with another chronic disease, carers of a person with dementia report higher levels of subjective burden and lower quality of life.5 Thus, there is an urgent need to understand how family carers can be supported to continue in their carer role for as long as possible.

The experience of family members who provide care for individuals with dementia is becoming better understood; however, research into the regional Australian perspective is lacking. One of the more stressful events for family carers is when hospital admission is required for the person they care for.6-8 Hospital admission of people with dementia is associated with poor outcomes and patient decline,9 which can lead to the need for discharge to a residential aged care facility. To support optimal outcomes for the person with dementia (patient) and the family carer, it is recommended that they be considered a dyad related to the hospital experience.7 However, patients and carers frequently do not experience this with regional location adding complexity for several reasons. For instance, health services, such as assessment and diagnostic facilities, are limited in regional Australia.2 Additionally, access to suitably trained healthcare staff and local specialist services, such as neurology and gerontology, are less available.10, 11

A greater understanding of the issues associated with hospital care could be used to inform patient and carer management in regional areas of Australia, improve outcomes for this population and support the goal of ‘ageing in place’. This study explored the experience of carers of people with dementia in one regional location in Australia when hospital care or treatment was required for the person they provide care for. This paper discusses the findings related to the physical and emotional events that impacted carers during hospital admission and discharge.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design

Due to their proximity to the person with dementia, family carers can provide valuable insight into the experiences of these individuals. They will have navigated through the events of their lived experiences and reflected on the elements that were challenging or supportive for themselves and the person they provide care for. Interpretative phenomenology is a qualitative research approach that explores the lived experience of a phenomenon and was adopted for this study.12 The Central Queensland University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the research protocol (Approval number HREC/2021-032).

Three methods were used to support this study's rigour: a self-reflexive journal kept by the researcher, member checking of analysed findings with two study participants and investigator triangulation during data analysis with two research team members with experience in qualitative research. In addition, peer debriefing occurred throughout the research process.

2.2 Data collection

Participants were recruited via a 1 day respite centre located in regional Queensland, Australia. The nearest major city was Brisbane, Australia. Recruitment flyers were distributed at the respite centre to the carers of clients identified as people living with dementia. Consenting participants were then contacted via phone and screened for eligibility. There were three eligibility criteria for participants, including that (a) they were over the age of 18, (b) they were an unpaid carer of a person with dementia and (c) the person living with dementia that they cared for had been involved in an episode of care with the region's public hospital in the last 12 months. Pseudonyms were allocated to each carer participant (such as ‘Carer 1’) to maintain confidentiality. The person with dementia being cared for by participants is referred to as ‘patient’ in this paper to contextualise the hospital setting focus of the study.

Semi-structured interviews were held with each participant between May 2021 and June 2021. Three carers chose to be interviewed face to face at the day respite centre, one carer chose a local café as their interview location and two carers opted for a phone interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by the research team shortly after. Participants were asked to describe their experience of providing care for their family member who was living with dementia. Interviews consisted of 10 open-ended questions, such as: “Can you tell me a bit about your journey caring for [person with dementia]?”, “Could you tell me what it was like for you, when [person with dementia] was most recently admitted to hospital?” and “Were there any events that stood out for you, positive or negative?”.

2.3 Data analysis

Data analysis occurred via three key processes: reading and highlighting, coding and grouping. NVivo 24 (QSR International) was used for the data analysis process. First, each interview transcript was read and re-read to gain a global feel of the experience. Next, sections of text that were particularly revealing about the experience were highlighted. Finally, descriptive codes were used to allocate labels to text sections grouped together with similar meanings. These groupings formed the major themes and sub-themes for the study.

3 RESULTS

Eleven carers expressed an interest in participating in the study. Two were unable to be reached by phone, and three did not meet the eligibility criteria. One carer withdrew from the study before their scheduled interview due to carer responsibilities, and one additional carer contacted the researcher after being informed of the study by word of mouth from another participant. Two participants were carers for the same person living with dementia (carers 1 and 5). In total, six carers (n = 6) participated in the study. Table 1 provides further details about each participant.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Relationship to patient | Years as carer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carer 1 | 50 | Female | Daughter | 10 |

| Carer 2 | 74 | Male | Husband | 5 |

| Carer 3 | 72 | Female | Wife | 15 |

| Carer 4 | 71 | Female | Wife | 4 |

| Carer 5 | 78 | Female | Wife | 10 |

| Carer 6 | 52 | Female | Daughter | 15 |

Three major themes and nine subthemes emerged from data analysis, as shown in Figure 1. The major themes were as follows: (i) support and supply of specialist care, (ii) travel needs and negotiations and (iii) empathy and experience make a difference.

3.1 Theme 1: Support and supply of specialist care

3.1.1 Subtheme 1: Diagnostic services are limited and insufficient

So he [the patient] had to go over [to the local hospital] and be assessed by um, the neurologist. And he looked at him and he reckoned he'd had a deep brain uh, stroke…That was his assessment…So, anyway they did more scans at the hospital here. And the radiologist there could not see that. So okay. So at this point, we needed a decent assessment for his neurology. So we endeavoured to get him a place at the Brisbane hospital, there was a neurologist there…And um, got on the telephone and got an appointment with that doctor. And he [patient] had to wait a while. But he eventually got a transfer. In the aeroplane. (Carer 5)

Even when dad was discharged from Brisbane, he was supposed to get into a transition care programme which is a standard intervention however coming back here there's no continuity of care and he didn't get it so that was another challenge that dad had to get through. So not having access to any rehab. (Carer 1)

3.1.2 Subtheme 2: Support for local services is needed

Even the social part where we were lucky enough to get to the day-respite centre. And that was a godsend, it's gold standard. I was talking with the previous local government, they were trying to get rid of it and I said ‘No!’. They said it's not a fit for local government, and I said ‘yes I know there's a lot of legacy programs but it does fit with local governments because you look after local residents’. It doesn't matter um, I guess that you've taken it on board, that it's there. But it's facilitating community and a lot of contacts within the community, so there is a need. And knowing that Brisbane and the big areas do a lot different things with seniors. (Carer 1)

“I've got times set because I had this argument on Monday with the service in Brisbane. Um, they do all their rostering from down there. The lady who runs it here is fantastic, and she's not allowed to do rostering. And they change the times, like I said to her, ‘I make a specific time for a certain lady to come, say 10 o'clock till 12 o'clock’. Now, in that time when she's with the wife, I've got to make my appointments, whether it be a solicitor's appointment or a doctors appointment. I'll get my car to the garage, or I'll go and do grocery shopping. If you change that time, I don't know ‘til that carer gets there, or rings me up or sends me a text the night before. It's too late for me, I gotta cancel what I've got tot do because I can't get there, because she's not coming at that set time. I said, you gotta be realistic. (Carer 2)

3.1.3 Subtheme 3: Specialist care in regions is accessible if within one's financial reach

No, we don't [travel to Brisbane for care]. No because we've got private health. So we can, we get it here… I don't have to go through the public hospital… And I tell people I would starve before I gave up my private health. (Carer 3)

3.2 Theme 2: Travel needs and negotiations

3.2.1 Subtheme 1: Carers' travel needs are overlooked

Like I lived at the hospital [in Brisbane], I stayed across the road. Cost me $135 a night and I was at that hospital by 6 every morning and wouldn't leave till 9 o'clock [PM]. Sometimes if she was playing up, sometimes they'd ring me at 3 o'clock [AM], wake me up and ask me to come over, because she's uncontrollable… And if I wanted a coffee, I'd have to go and get it myself. I never got any meals or anything like that. Near the hospital, the only place that was open where I was, was Hungry Jacks down at the corner, near the servo. So I lived on chicken nuggets. I went from 95 kilos to 79 in 3 and a half weeks. (Carer 2)

So I think from a carers point of view, that aspect [carer's needs] is a key thing that's missing when I've been in hospitals and seen or heard other carers' stories to say that outside the hospital caring, um, should be facilitated to make sure they're fed, you know watered, that type of thing. And even unloading, because a lot of those carers including myself, we're sitting in there and then you go outside and you know, you deal with it on your own. (Carer 1)

Yeah, a month and a half ago, he was in the hospital. And, um, so I was travelling from my suburb to, um, Mum was staying at CWA [Country Women's Association] place in Spring Hill [Greater Brisbane area]. Which is great. Or was great, (it's closed down) for regional people to actually stay there. So, it was close enough for her and, um, got her out every morning or every afternoon just to go for walks in the garden, that sort of stuff. (Carer 1)

3.2.2 Subtheme 2: Travel processes create caring difficulty

So, getting Dad down to Brisbane was distressing enough – got on a flight…plane…none of us went…So even that, we didn't have time to prep Dad to get ready for a change of that magnitude. (Carer 1)

You know, it's like, they waited for somebody else that needed to go down, so we had about 20 minutes notification…That he [the patient] was getting on the aircraft to go to Brisbane. Which he did…there were stuff-ups all along. (Carer 5)

3.2.3 Subtheme 3: Consideration of clients' preferred travel mode

I just plan it to suit her [the patient]. Like, I don't go and rush her. And I put in for travel allowance at the hospital here, and one of the girls said, ‘why didn't you go by train? It's cheaper by train’. And I just said, ‘well if you have a dementia patient or a patient who's got brain damage and you go by train, and they want to go to the toilet you don't want to try and get up and down to the toilet’. I said, ‘In a motor car, you're independent, you can stop wherever you want, even if it's on the side of the road, for however long you want’. (Carer 2)

Well, at one stage, they were, they thought that he should be discharged and that, uh, I think the emphasis was for us to get an ambulance or whatever [to Brisbane] and um, we rejected that. And, uh, we stood, stayed where we were. And then, when an availability came, where someone needed to go on that aircraft, there was space there for him [the patient]. So, I was able to say bye-bye and we'll see you in Brisbane. And um, you know. Because he was going to the, um, Brisbane hospital. From my point of view, I was happy that he [the patient] was going where he went. He was happy because he likes aircraft. He'll go anywhere in an aeroplane. Oh, he was quite happy once he heard that he was going. (Carer 5)

3.3 Theme 3: Empathy and experience makes a difference

3.3.1 Subtheme 1: Workforce qualities impact care

So, they need a neurology referral process that is suitable, and to be honest, I know this is an area of need through, you know, area of need program, it's an Australian Government Funded Program. The States administer it, so Queensland looks after this area of need. Unfortunately, that program hasn't been evaluated in all its time. It's produced a revolving door of doctors and specialists, which I believe is contributing to the lack of continuity of care in regional areas. (Carer 1)

With the doctors up at the hospital, we have, in surgical and medical wards, now we have overseas-trained doctors. Many of them are very intelligent, but some could not be understood… Very challenging. (Carer 5)

So, I have to comment about the nurses and the doctors. Mum can't understand them. They're trying to explain something to her, and even to me, we have trouble trying to pick that up properly, because they have such accents that, half the time, it doesn't sound like what they're trying to say. It's very confusing. (Carer 6)

It's so important. It's more that just mum. All these other people will go to hospital and they don't understand and they can't work out the words that are coming out of the doctors and nurses mouths. They rush in there, they ‘blah, blah, blah’ to them, and then they race off. And they expect the patients to understand what they just said and what they're meant to do. (Carer 6)

3.3.2 Subtheme 2: Experience matters

The hospital, they keep missing everything. Like that time with that young bloke that did the x-rays and everything like that. They completely missed that mum had ripped her muscle from the bone on her buttocks. (Carer 6)

The young doctor who did that, he was really horrible and he made me feel like, um, this was all my fault. And that I was going to get into trouble and that they were gonna put mum in a nursing home, like I said. And I just felt like I had no rights. I had no say. I had to do everything I was told, He did not care that mum was in tears, or what he was doing to her. (Carer 6)

But she was older, experienced, she was everything you'd expect a Social Worker to be. And she gave us the information that we required. Answered all the questions and so forth. Yes. So, we went from there to, uh, to others. And, uh, they were both young, inexperienced, no empathy. Um, they – transferring information was, um, oh. They were… no. Awful! (Carer 5)

And we sat there [in the emergency waiting area] probably another hour and then there was another lady sitting beside me, who I chatted to. And I said, ‘he's getting irritable again’ and she just said to me, ‘well go and sit down, it won't be much longer’. But before I could go and sit down he took off outside again. And this time I was out there and I couldn't get him back in, and eventually the lady I'd been talking to came out. And she managed to talk him, sweet talk him, into going back in…. And it turns out she had worked in aged care when she worked, so she sort of knew a bit about it and knew how to talk to them. But I was just, a little bit upset that it was a lady in the waiting room that helped us… I think those at the desk might help if they knew a little bit about dementia. (Carer 4)

3.3.3 Subtheme 3: Empathy helps in the absence of specialised knowledge

And I must admit, once we saw a doctor [in the Emergency Department], we couldn't have got better treatment…When I mentioned to her that, you know, that he'd run away… she was apologetic, and, you know, got onto his medication straight away. And it was very good. They had that understanding and compassion there. (Carer 4)

4 DISCUSSION

This study explored the experience of carers of people with dementia in regional Australia when hospital care or treatment was required for the person they provide care for. A range of events impacted carers' ability to retain control over their family members' care and maintain their well-being. Three main themes emerged from interviews with carers (i) support and supply of specialist care, (ii) travel needs and negotiations and (iii) empathy and experience make a difference. The findings from this study highlight aspects of care that can be addressed to improve outcomes for patients with dementia and their carers.

The analysis identified the availability and access challenges to specialist treatment and carers in regional Australian hospitals. There are limitations on the availability of diagnostic and therapeutic services in regional hospitals; inter-hospital transfer (IHT) is frequently necessary when patient needs cannot be met at their current facility. Patients' well-being is critical when deciding on IHT, and the benefits of transfer must outweigh the risks.13 A hastily conducted and poorly coordinated transfer can increase the risk of harm to the patient.14 On the other hand, a patient-centred approach when IHT is necessary can optimise outcomes, particularly to ensure patient safety.15 In this study, carers experienced several challenges with IHT, which were mainly process-related. Lack of time to prepare their relative for transfer was a concern for carers as was their inability to accompany them, mainly when IHT occurred via air transport. In considering the person with dementia and their carer as a dyad,7 use of ground transport (where the carer can accompany the patient), may facilitate a more patient-centred approach and optimal IHT.

Specialist care is also related to the qualities of treating healthcare providers in regional Australia. Whilst medical staff choose to work in regional Australia, this tends to be transient.16 With most Australian-trained doctors choosing to live in metro areas, regional Australia remains reliant on internationally trained medical graduates.17 However, internationally trained medical (and nursing) staff face unique challenges when communicating with patients across language and cultural divides.18

Internationally trained medical graduates (IMG) can receive training in countries where doctors possess significant control, authority and power in the patient-healthcare provider relationship.19, 20 Some may have difficulty understanding patient involvement and autonomy.19 Carers in this study reported problems in understanding treatment and management plans for their relatives when internationally trained healthcare staff seemed unwilling to spend time with them. Language difficulties compounded the problem for carers. Whilst English language abilities may be sufficient amongst IMG working in Australia, accents and mastery of colloquial, rather than ‘medical’ English, can be problematic, potentially leading to misunderstandings.20 Key to achieving optimal patient outcomes is good communication, involvement and relationship building between healthcare staff and carers.6 Carers need opportunities to seek clarification and provide input on care plans.

Attitudes towards people with dementia can significantly impact the type of care they receive.21 Negative attitudes and stigmatisation can lead to inappropriate communication and poor care for these patients.21, 22 A study in Queensland, Australia, found that healthcare staff with dementia care education, who had spent more time working with people with dementia, and had more work experience in general, possessed more self-confidence and positive attitudes when caring for a person with dementia.23 However, healthcare professionals possessing specialist training are limited in regional Australia.10, 11, 24 The carers in this study reported better treatment from healthcare staff who had experience in their role and in working with people with dementia. Where carers perceived empathy and understanding from their healthcare practitioner, they felt the treatment received was considerate, acceptable and reflected a positive attitude towards their relative's condition. Staff training that supports understanding of appropriate dementia care is of key importance for improved patient and carer outcomes.6

4.1 Limitations

This study explored carers' perspectives across one regional area of Australia. The findings provide valuable insight into an under-researched population who are vital in the web of dementia care, however, the findings may not be transferrable to other states or regional areas where resourcing and distance to specialist care varies. The sample size, whilst small, provides viewpoints and evidence to compare to the existing research and can contribute to a better understanding of approaches that can support carers at this particularly challenging time.

5 CONCLUSION

This research adds to the understanding of carers' experiences, in regional Australia when the person with dementia they provide care for is admitted to an acute care hospital. It is known that carers experience much stress during such events; their well-being needs to be considered to support them in continuing in their carer role and optimise patient outcomes. Good communication by healthcare staff and the carer's involvement in treatment and care planning is crucial. Hospital staff training in appropriate dementia care and adopting dementia-friendly hospital processes will help address these carer challenges. Continued government interventions and strategies must be implemented to support the regional healthcare workforce and the high demand for quality dementia care services in these areas.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anthea OORLOFF: Conceptualization; methodology; investigation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; validation; formal analysis. Angel NISBET: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing; validation; methodology; formal analysis; data curation. Lisa LOLE: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing; validation; methodology; formal analysis; data curation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the carer participants in this study for taking the time to share the details of their experience with their family member during hospital admission. Open access publishing facilitated by Central Queensland University, as part of the Wiley - Central Queensland University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

6 ETHICAL APPROVAL

This research was conducted in regional Queensland, Australia, with approval from the Central Queensland University Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 2021-032).