Frequent users of health services among community-based older Australians: Characteristics and association with mortality

Funding information

This research was funded by Sydney Local Health District, South Eastern Sydney Local Health District and the South and Eastern Sydney Primary Health Network

Abstract

Objectives

To investigate characteristics of frequent users of general practice (GP; ≥21 visits in a year), medical specialist (≥10 visits), emergency department (ED; ≥2 presentations) and hospital services (≥2 overnight hospitalisations) and the association with mortality for people aged over 75 years.

Methods

The study included residents from Central and Eastern Sydney, Australia, aged over 75 years who participated in a large community-dwelling cohort study. Demographic, social and health characteristics data were extracted from the 45 and Up Study survey. Health service (GP, medical specialist, ED and hospitalisations) use and mortality data were extracted from linked administrative data. We calculated adjusted prevalence ratios to identify independent characteristics associated with frequent users of services at baseline (approx. 2008) and adjusted hazard ratios to assess the association between frequent users of services and mortality.

Results

Frequent users of services (GPs, medical specialists, EDs and hospitals) were more likely to be associated with ever having had heart disease and less likely to be associated with reporting good quality of life. Characteristics varied by service type. Frequent users of services were 1.5–2.0 times more likely to die within 7 years compared to those who were less frequent service users after controlling for all significant factors.

Conclusions

Our analysis found that frequent service users aged over 75 years had poorer quality of life, more complex health conditions and higher mortality and so their health service use was not inappropriate. However, better management of these frequent service users may lead to better health outcomes.

Policy Impact

This study found that older people who were frequent users of GPs, medical specialists, EDs and/or hospitals, had a greater mortality risk. The characteristics of frequent health service use provides a basis for services to develop algorithms to identify at-risk individuals. This study resource could also facilitate further locally based research to identify which additional assessment and care interventions will have the greatest impact.

1 BACKGROUND

The Australian population is ageing.1 In 2017, people aged 75 years and over represented 7% of Australia's population, which is projected to rise to 12% by 2066.1 A higher percentage of older individuals use health services compared to those who are younger. Analysis by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) found that people 65 years and older were responsible for 20%–45% of health service use in 2016/17 even though they represented only 15% of the Australian population.2 People aged 65 years and over made almost 2.3 times the number of claims for general practitioner (GP) attendances, more than 4 times as many claims for medical specialist services, accounted for 23% of emergency department (ED) presentations and 41% of overnight hospitalisations.

Burkett et al.3 projected that ED presentations by older Australians would increase between 2010 and 2050 by 2.4 times for those aged 65–84 years and by 4 times for those aged 85 years and over. A prospective 16-year longitudinal study of 1000 Australians 65 years and older revealed an increasing burden of disease for many older people and thus an additional demand for health and support services in the future.4

Although the proportion of individuals who frequently present to EDs (defined as six or more visits in a year) and other health services is small (~5%), there is evidence that they account for 20%–30% of visits and associated costs.5, 6 Frequent users of EDs are also often frequent users of other health services7; therefore, these frequent users can have a significant impact on the health system. For example, older adults who are frequent users of EDs are more likely to be sicker, be transported to ED by ambulance, require more urgent care, be admitted to ED or hospital, and have higher rates of adverse outcomes following discharge.8, 9

The Central and Eastern Sydney Primary and Community Health Cohort/Resource (CES-P&CH) was established to enable planners, policymakers and health service providers to investigate health issues and establish health priorities.10 A meeting of stakeholders considering Research Priorities for Central and Eastern Sydney (CES) in 2019 identified patients over 75 years of age who were frequent users of ED to be a population where research was needed. They wanted to understand the socio-demographic and health characteristics and outcomes associated with older frequent users of four health services: GP attendances, medical specialist attendances, ED presentations and overnight hospital stays. The service providers were particularly interested in reducing the number of frequent service users without impacting the quality of care. There were also some concerns that the frequent service users were inappropriately using health services when welfare services could be used, as has been identified by other authors.11

Although there is an abundance of studies that explore risk characteristics, predictors and outcomes of frequent service users,12-15 as far as we can ascertain, there are no Australian studies and very few overseas studies that investigated frequent service use in community-based older people. Also, studies looking at perceptions of inappropriate service use have usually only focused on one service, such as ED, and have not included long-term outcomes, such as mortality.9, 11 The aim of this study was to identify the characteristics independently associated with frequent users of four health services and to investigate the association between frequent users of services and mortality among people aged over 75 years.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and population

We conducted a prospective population-based cohort study using the CES-P&CH10 (n = 30,645) based on the Sax Institute's 45 and Up Study.16 The 45 and Up Study recruited 267,153 New South Wales (NSW) residents at baseline (2006–2009). Potential study participants aged 45 years or older in NSW were randomly sampled from the Services Australia (formerly the Australian Government Department of Human Services) Medicare enrolment database with oversampling in people aged 80 years and over in rural and remote areas. Participants joined the study by completing the baseline questionnaire on a range of participant characteristics and providing consent for long-term follow-up, including linkage of their questionnaire data to health and other records. The questionnaire needed to be self-completed. If people with conditions such as dementia or stroke were not able to complete the questionnaire unaided, they may have been under-represented in the cohort. The overall response rate was 18%.

The population for this study included participants who resided in CES and were aged over 75 years. The postcode of residence was geocoded and mapped to the CES Primary Health Network (PHN) region as defined by the Australian government. Participants were excluded if the individual had multiple dates of death (due to a linkage error) or died within the three-year baseline period.

2.2 Data sources and measures

This research used data from the CES-P&CH, which brings together population-based data from the Sax Institute's 45 and Up Study16 in NSW, Australia, and national and state administrative datasets provided by Services Australia and the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage. Deterministic linkage to the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) was facilitated by the Sax Institute using a unique identifier provided by Services Australia. Linkage to the state administrative datasets (Admitted Patient Data Collection [APDC], Emergency Department Data Collection [EDDC] and death registrations from the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages [RBDM]) were undertaken by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage using probabilistic techniques.17

The main measures used in the analysis were participant socio-demographic and health characteristics, frequency of health service use and mortality. Socio-demographic and health characteristics were based on the relevant questions in the 45 and Up Study baseline survey. These included age, gender, qualifications, income, work status, health insurance, marital status, smoking, alcohol, body mass index (BMI), treatment for high blood pressure and cholesterol, excellent, very good or good quality of life, fall in the past 12 months, osteoporosis, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer (see Table S1 that includes details about the survey and the variables described). Health services investigated included GP attendances that were based on GP attendance and activity items claimed by patients and subsidised by the MBS (Table S2); medical specialist attendances that were based on medical specialist attendance and activity items claimed by patients and subsidised by the MBS (Table S2); ED presentations were based on EDDC data; and overnight hospitalisations were based on APDC data. Deaths were based on entries in the NSW Death Registry.

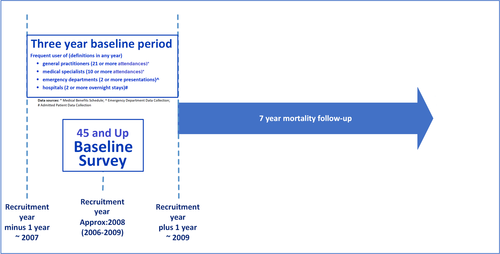

There are currently no agreed definitions for frequent users of health services. Studies either use a percentile cut-off (varying between the 66th percentile and the 97th percentile) or a number of attendances over varying periods to define frequent users.18-20 In our study, participants were categorised as frequent users (for each health service) based on their highest number of attendances/presentations/hospitalisations in any calendar year in the three-year baseline period (the year before recruitment, the recruitment year and the year following recruitment). Three years were used to increase the number of frequent users. The cut off points for each of the services were based on the literature18-20 and the data with frequent users of GPs being 21 or more attendances in any year, frequent users of medical specialists being 10 or more attendances, frequent users of EDs being two or more presentations and frequent users of hospitals being two or more overnight stays.

Participant death records were then examined for up to 7 years from the end of the three-year baseline period (see Figure 1). All-cause mortality occurring within 7 years of the end of the three-year baseline period was the outcome of interest.

2.3 Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted for this research study by the Research Ethics Committee and from the Human Research Ethics Committee for the 45 and Up Study overall. All participants provided written consent before participating in the 45 and Up Study, including consent to follow them over time using their health and other records, contact them in the future about changes in health and lifestyle, and use their data for health research.

2.4 Statistical analysis

To identify factors associated with frequent users for each of the health services (GP, medical specialist, ED and hospital), we used prevalence ratio (PR) as the measure of association. Poisson regression models were used to estimate the PRs and the 95% confidence intervals for frequent users of each health service. Crude and adjusted PRs were calculated adjusting for all of the other potential risks identified.

We calculated the death rate for the exposure groups using person-time as the denominator. Person-time started at the end of the 3-year baseline period (i.e., 1 year after the baseline survey) and was censored at the date of death or at 7 years whichever came first. Cox proportional hazard model estimated the hazard ratio (HR) where time to death from the starting point of follow-up was the time scale. HRs were adjusted for the potential confounders that were found to be associated with the exposure of interest at p < 0.05. Age and sex were forcefully put into the model if they were not found to be associated with the exposure of interest because age and sex have been shown in the literature to be related to the outcome.21 We also checked for effect modification for sex and age categories by including an interaction term between the exposure of interest and sex or age categories into the multivariable Cox proportional hazard model. If the coefficient of the interaction term was significant at p < 0.05, we also presented stratified analysis as supplementary analysis. Statistical significance was determined if the p values were <0.05%. We used SAS version 9.422 for data management and R version 3.5.123 for statistical analyses.

3 RESULTS

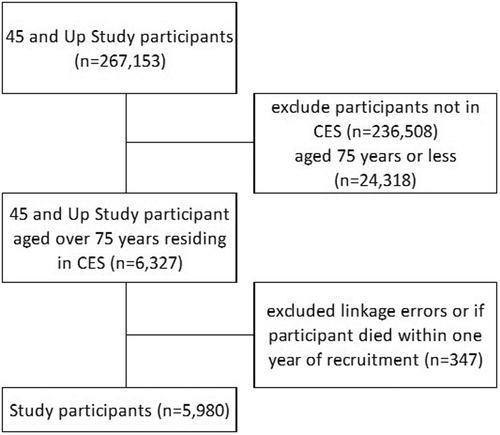

Of the 30,645 people in the CES who completed the 45 and Up Study baseline survey, 6327 (21%) were aged over 75 years, with 21% (1060) being older than 85 years. In the cohort, 53% (3325) were males, 45% (2745) had a trade, diploma or university qualifications, 19% (1221) spoke a language other than English at home, 94% (5813) were retired/not working, 57% (3614) had private health insurance and 53% (3336) currently had a partner (married or de facto). Table S3 summarises the characteristics of CES-P&CH participants aged over 75 years at recruitment into the 45 and Up Study. For the analysis, 347 participants were excluded because the individual either had multiple dates of death or died within 1 year of joining the 45 and Up Study. This gave a study population of 5980 participants (Figure 2).

Of the study population, 27% (1645) were determined to be frequent users of GPs (21 or more attendances in any year), 28% (1678) were frequent users of medical specialists (10 or more attendances), 16% (982) were frequent users of EDs (two or more presentations) and 22% (1288) were frequent users of hospitals (two or more overnight stays in any year of the three-year baseline period).

3.1 Characteristics associated with frequent service use

Table 1 shows the characteristics associated with frequent users of GPs, medical specialists, EDs and hospitals compared with less frequent users after controlling for all characteristics in the models (see Tables S4–S7 for more details).

| Factors | Adj. PR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent users of general practitioners (21 or more visits) | Frequent users of medical specialists (10 or more visits) | Frequent users of emergency department (2 or more presentations) | Frequent users of hospitals (2 or more overnight hospitalisations) | |

| Age at recruitment | ||||

| ≤80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 81–85 | 1.13 (0.99, 1.29) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.00, 1.36) |

| 86–90 | 1.13 (0.94, 1.34) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.57) | 1.37 (1.13, 1.66) |

| >90 | 1.25 (0.95, 1.63) | 0.68 (0.47, 0.95) | 1.49 (1.09, 2.02) | 1.46 (1.08, 1.94) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.98 (0.85, 1.12) | 0.94 (0.82, 1.08) | 0.77 (0.65, 0.92) | 0.79 (0.68, 0.93) |

| Highest educational qualification | ||||

| Less than high school | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Year 12 or equivalent | 0.97 (0.81, 1.15) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.22) | 1.15 (0.92, 1.44) | 1.14 (0.93, 1.38) |

| Trade/Diploma | 0.91 (0.79, 1.05) | 1.05 (0.92, 1.20) | 0.83 (0.69, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) |

| University or higher | 0.76 (0.63, 0.91) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.12) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) |

| Speaks other than English at home | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.41 (1.23, 1.61) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.90 (0.74, 1.08) | 0.82 (0.69, 0.98) |

| Household income | ||||

| <$20,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 0.85 (0.72, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.11) | 0.91 (0.73, 1.12) | 1.07 (0.90, 1.28) |

| 40,000–69,999 | 0.89 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.91 (0.75, 1.10) | 1.23 (0.94, 1.59) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.42) |

| 70,000 or more | 0.62 (0.46, 0.84) | 1.00 (0.80, 1.24) | 1.00 (0.70, 1.39) | 1.09 (0.82, 1.42) |

| Won't disclose | 0.95 (0.83, 1.09) | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) | 1.05 (0.89, 1.23) |

| Work status | ||||

| Not working | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Part-/Full-time working | 0.97 (0.75, 1.24) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.20) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.07) | 0.93 (0.71, 1.21) |

| Having private health insurance | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.25 (1.11, 1.41) | 2.33 (2.04, 2.67) | 0.68 (0.58, 0.80) | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) |

| Having a health-care concession card | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.31 (1.17, 1.47) | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.21) | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) |

| Currently married/partner | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.82, 1.04) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoked | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) | 1.22 (1.08, 1.37) | 1.13 (0.97, 1.33) | 1.25 (1.09, 1.43) |

| Current smoker | 1.16 (0.81, 1.59) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.58) | 1.35 (0.90, 1.96) | 1.01 (0.65, 1.50) |

| Adequate physical activity | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01) | 0.88 (0.78, 0.98) | 0.81 (0.70, 0.94) | 0.74 (0.65, 0.84) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Zero | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1–13 drinks/week | 0.87 (0.77, 0.98) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 0.82 (0.70, 0.97) | 0.83 (0.72, 0.95) |

| 14+ drinks/week | 0.76 (0.62, 0.91) | 0.97 (0.81, 1.15) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.14) | 0.86 (0.71, 1.05) |

| Body Mass Index category | ||||

| Underweight | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Normal weight | 0.98 (0.82, 1.17) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) | 1.02 (0.82, 1.26) | 1.01 (0.84, 1.24) |

| Overweight | 1.04 (0.87, 1.24) | 1.05 (0.88, 1.26) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.10) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.25) |

| Obese | 0.98 (0.80, 1.21) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.27) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.78, 1.26) |

| Being treated for high blood pressure | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.23 (1.09, 1.38) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | 1.07 (0.93, 1.22) |

| Being treated for high cholesterol | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.01 (0.87, 1.16) | 0.90 (0.78, 1.04) | 0.90 (0.74, 1.08) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

| Self-reported good quality of life | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.79 (0.69, 0.91) | 0.84 (0.73, 0.97) | 0.72 (0.61, 0.85) | 0.75 (0.65, 0.87) |

| Reported at least one fall in 12 months | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.09 (0.97, 1.23) | 1.19 (1.06, 1.33) | 1.33 (1.14, 1.54) | 1.21 (1.06, 1.38) |

| Self-reported osteoporosis | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.12 (0.96, 1.30) | 1.30 (1.12, 1.50) | 1.11 (0.91, 1.35) | 1.10 (0.93, 1.31) |

| Self-reported heart disease | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.41 (1.26, 1.58) | 1.44 (1.29, 1.61) | 1.58 (1.37, 1.83) | 1.50 (1.32, 1.71) |

| Self-reported diabetes | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.06 (0.90, 1.24) | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.17 (0.95, 1.43) | 1.23 (1.03, 1.46) |

| Self-reported cancer | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) | 1.26 (1.12, 1.41) | 1.09 (0.92, 1.28) | 1.20 (1.05, 1.38) |

- Note: Sample for General Practice use was 5980, medical specialist use was 5980, Emergency Department use was 5158 (data not available for 822 participants recruited in 2006) and overnight hospitalisations was 5980. For the adjusted analysis for each of the services, each variable in the table was controlled for using all of the other variables in the table. If significantly increased (p < 0.05) adjusted prevalence rate is bolded; if significantly less, adjusted PR is bolded and italicised. BMI categories underweight normal weight overweight obese.

The characteristics significantly more likely to be associated with frequent users of GPs were being aged 81–85 years, speaking a language other than English at home, having private health insurance, having a healthcare concession card, being an ex-smoker, reporting treatment for high blood pressure, and ever having heart disease. The characteristics significantly less likely to be associated with frequent users of GPs were having a university degree or higher, having a household income of $20,000–$39,999 or $70,000 or more, reporting 1–13 or 14 or more alcoholic drinks per week, and reporting good quality of life.

The characteristics significantly more likely to be associated with participants who were frequent users of medical specialists were as follows: having private health insurance, being an ex-smoker, reporting at least one fall in the last 12 months, reporting ever having osteoporosis, heart disease, or cancer. The characteristics significantly less likely to be associated with frequent users of medical specialists were being aged >90 years, having adequate physical activity, and reporting good quality of life.

The characteristics significantly more likely to be associated with frequent users of EDs were being aged >85 years, reporting at least one fall in the last 12 months, and reporting heart disease. The characteristics significantly less likely to be associated with frequent users of EDs were being female, having private health insurance, having adequate physical activity, consuming 1–13 alcoholic drinks per week, and reporting good quality of life.

The characteristics significantly more likely to be associated with frequent users of hospitals (overnight stay) were being aged >80 years, being an ex-smoker, reporting at least one fall in the last 12 months, ever having heart disease, diabetes or cancer. The characteristics significantly less likely to be associated with frequent users of hospitals were being female, speaking a language other than English at home, having a health concession card, being married or having a partner, having adequate physical activity, consuming 1–13 alcoholic drinks per week and reporting good quality of life.

3.2 Frequent users of health services and mortality

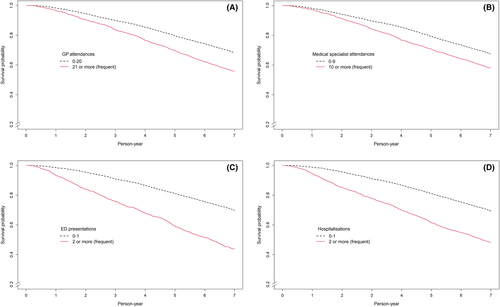

Among the people (n = 5980) who survived for at least 1 year after the baseline interview, 2103 (35%) had died within 7 years of follow up (Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that frequent users of GPs, medical specialists, EDs and hospitals were associated with a greater risk of mortality (Figure 3). Participants who were frequent users of EDs were almost twice as likely to die (Adj HR: 1.95; 95% CI:1.73, 2.19); while those who were frequent users of GPs or medical specialists were around 50% more likely to die than those who were not (GP—Adj HR: 1.50; 95% CI:1.33, 1.68; medical specialist—Adj HR: 1.44; 95% CI:1.30, 1.60). Those who were frequent hospital users had a 67% higher risk of dying than those who were not (Adj HR: 1.67; 95% CI:1.50, 1.86). We examined the interaction effect between frequent users for all of the services and 7-year mortality. We found a significant effect modifier for the age group for frequent users of medical specialists. The stratified analysis is provided in Table S8. The association between frequent users of medical specialists and 7-year mortality was significantly higher among the younger age groups.

| Highest number of services used in any year of the 3-year baseline period | N | Death ≤7 years of recruitment (+1 year) | Mortality per 1000 person-years | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adj. Hazard Ratio (95% CI)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practice attendances (n = 5980) | |||||

| 0–20 | 4335 | 1376 | 42.6 | 1 | 1 |

| 21 or more (frequent) | 1645 | 727 | 62.3 | 1.54 (1.41, 1.69) | 1.40 (1.26, 1.56) |

| Medical specialist attendances (n = 5980) | |||||

| 0–9 | 4302 | 1398 | 46.1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 or more (frequent) | 1678 | 705 | 58.6 | 1.41 (1.29, 1.54) | 1.44 (1.30, 1.60) |

| Emergency department presentations (n = 5158) | |||||

| 0–1 | 4176 | 1260 | 42.3 | 1 | |

| 2 or more (frequent) | 982 | 553 | 93.0 | 2.38 (2.16, 2.64) | 1.95 (1.73, 2.19) |

| Hospitalisations (n = 5980) | |||||

| 0–1 | 4692 | 1435 | 42.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 or more (frequent) | 1288 | 668 | 83.8 | 2.09 (1.91, 2.29) | 1.67 (1.50, 1.86) |

- Note: Emergency department data not available for 822 participants recruited in 2006. Adj. Hazard Ratio Model controlled for age, gender and all socio-demographic, health risk factor, health status and health-care utilisation characteristics that were statistically significant. If significantly increased (p < 0.05), hazard ratio is bolded.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first Australian population-based study to look at the characteristics independently associated with frequent users of GPs, medical specialists, EDs, and hospitals in an inner-city community dwelling population aged over 75 years and the impact on mortality.

We found some factors that were associated with frequent users across services, such as being ex-smokers, having at least one fall in the last 12 months and ever having been diagnosed with heart disease. Many of the studies reviewed did not investigate individual conditions but found measures of co-morbidity or the number of conditions were associated with frequent users of services.11, 13-15

There were also some factors that were less likely to be associated with frequent users across services, such as adequate physical activity, reporting good quality of life and consuming 1–13 alcoholic drinks per week. Reporting poorer or lower quality of life was supported by evidence that frequent users of medical specialists, EDs and hospitalisations were more likely to report poorer health.13, 14, 26 With regard to consuming 1–13 alcoholic drinks per week, there is growing evidence that low to moderate alcohol consumption is protective as people age,22 although it is not clear if the benefit is because of the ethanol or the social and pleasurable benefits of drinking alcohol.

However, it is important to remember that differences may exist between our study and others due to differences in the study population's socio-demographic and health characteristics, the data sources used, the scope and definitions of the various characteristics studied and the differences in social, cultural and health environments to Australia. We examined 21 demographic characteristics, risk factors and health conditions, many of which were not examined elsewhere.

We found that being a frequent user was significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality with frequent users of EDs having a 95% increased mortality followed by frequent users of hospitals (67% higher), frequent users of GPs (50% higher) and frequent users of medical specialists (44% higher). Our mortality risk results were slightly lower than other studies investigating outcomes of frequent users of EDs and hospitals on mortality rates, although many of these studies are not community-based.25, 26 A systematic review by Moe et al, which summarised evidence from 31 studies, found that frequent users of EDs are at increased odds of death of around 2.2.25 We are not aware of any studies investigating the impact of frequent users (GPs or medical specialists) on mortality. It is thought that this increased risk of death for frequent users of health services are most likely associated with the increased morbidity and disease complexity of this age group.7, 25, 27

A range of interventions have been evaluated to reduce the number of frequent users of emergency departments and hospital admissions, including risk identification, geriatric emergency departments, case management, individualised care plans, home visits, information sharing between hospital and community care providers, and combinations of these often referred to as ‘continuity of care’ interventions. The effectiveness of some of these individual interventions have shown mixed results for older people with some studies showing modest reductions in presentations and admissions and others showing no effect.28, 29 While interventions combining these individual interventions, such as continuity of care and transactional care interventions, have led to improvements in short- and long-term hospitalisations following hospital discharge among older people with chronic disease,30, 31 there is little evidence of their impact on ED return presentations and frequent GP visits. This study resource could facilitate further locally based research to identify which interventions may be best implemented for this population.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The CES-P&CH, based on the 45 and Up Study, is a unique data collection linking demographic, behavioural and health condition survey data about the participants with key health service data sources. CES-P&CH enabled the examination of frequent users of health services using a wide range of socio-demographic and health characteristics for residents of CES which would not have been possible without a huge investment in a time consuming and costly study. Our mortality analysis excluded those participants who died in the three-year baseline period when frequent service use was assessed, thus removing most participants whose frequent service use may be associated with their last year of life.

However, there are some limitations with the data and the analysis. The data on socio-demographic risk characteristics and conditions were limited to the information collected during the baseline survey in 2006–2009 and so our analysis may not include all the potential risk characteristics for frequent users of services identified in the literature, such as the presence of multiple co-morbidities and impairments that may have impacted upon our results. Also, the questionnaire needed to be self-completed and so if people with conditions, such as dementia or stroke, were not able to complete the questionnaire unaided, they may have been under-represented in the cohort. The study was limited to people living in metropolitan areas with overall good geographical access to services and so the results are unlikely to be generalisable to rural or remote areas. As part of this study was cross-sectional, we cannot determine if there is a casual relationship between the socio-demographic and health characteristics and frequent users of services. The study timeframe focused on the years around the initial recruitment of participants to the 45 and Up Study (2006–2009), which may limit the generalisation of the findings to 2021.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis found that frequent service users aged over 75 years had poorer quality of life, more complex health conditions and higher mortality and so their health service use could not be considered inappropriate. However, better management of these high service users, through early identification and targeted care, may reduce the need for ongoing frequent service use and ultimately improve their health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW; and partners: the Heart Foundation; NSW Ministry of Health; NSW Department of Communities and Justice; and Australian Red Cross Lifeblood. We thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study. We acknowledge the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CheReL) for linkage and provision of the hospital, emergency department and death data (http://www.cherel.org.au/) and Services Australia for the supply of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) data. We also acknowledge the Secure Unified Research Environment (SURE) for the provision of secure data access. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest declared. MB AK and MW's positions were funded by the funding partners. The CES Primary and Community Health Cohort/Linkage Resource management group includes representatives from each of the funding partners. The management group oversees what projects are conducted using the Resource and provides input into the overall design, interpretation of the results and knowledge translation opportunities.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Ethical approval was granted for this research study by the New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Ref # 2016/06/642) and from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee for the 45 and Up Study overall. All participants provided written consent before participating in the 45 and Up Study, this included consent to: follow them over time using their health and other records, contact them in the future about changes in health and lifestyle, and use their data for health research.

Data Sharing Statement

The analysis plan and programming code are available on request. Data that support the findings of this study are available from the Sax Institute, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Sax Institute.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The analysis plan and programming code are available on request. Data that support the findings of this study are available from the Sax Institute, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Sax Institute.