Patch size and breeding status influence movement patterns in the threatened Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata)

Abstract

Information on the movement ecology of species can assist with identifying barriers to dispersal and appropriate management actions. We focus on the threatened Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata) whose ability to move and disperse within fragmented landscapes is critical for their survival. We also investigate the possible effects of climate change on Malleefowl movement. We used solar-powered GPS telemetry to collect movement data and determine the influence of breeding status, remnant vegetation patches and environmental variables. Seven Malleefowl were tracked between 1 and 50 months, resulting in 20 932 fixes. While breeding, Malleefowl had significantly smaller home ranges (92 ± 43 ha breeding; 609 ± 708 ha non-breeding), moved shorter daily distances (1283 ± 605 breeding; 1567 ± 841 non-breeding) and stayed closer to the incubation mound (349 ± 324 m breeding; 3293 ± 2715 m non-breeding). Most Malleefowl effectively disassociated from the mound once breeding stopped, with two birds dispersing up to 10.2 km. Movement patterns were significantly correlated with the size of the remnant native vegetation patch, with smaller home ranges being utilized in small patches than in large patches. One male almost exclusively remained within a 107-ha patch for over 4 years, but a female crossed between closely spaced uncleared patches. Long-range movements of nearly 10 km daily displacement were recorded in large remnants almost exclusively when not breeding. Temperature and rain had a significant effect on movement: modelling suggests daily distances decline from 1.3 km at 25°C to 0.9 km at 45°C, with steeper declines over 30°C. The influence of patch size on movement patterns suggests that Malleefowl movement may be governed by the size of remnant patches and that habitat continuity may be important for facilitating recolonization after catastrophic events and maintaining genetic diversity. Climate change may reduce Malleefowl movement during hot, dry periods possibly affecting breeding success.

INTRODUCTION

Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata) are large, ground-dwelling birds that build mounds from soil and leaf litter to incubate their eggs. Endemic to Australia, historically abundant and widely distributed, they are now a threatened species listed as vulnerable in Australia and globally (EPBC Act, 1999; IUCN, 2012). Malleefowl populations have been decreasing at least since European settlement and continue to decline in many parts of Australia (Benshemesh et al., 2020; Stenhouse & Moseby, 2022). Declines are due to a combination of factors such as habitat loss and fragmentation, predation by the introduced fox and cat, competition with overabundant herbivores and the effects of dry conditions on soil moisture and vegetation (Benshemesh, 2007; Ford et al., 2001; Harlen & Priddel, 1996; Priddel et al., 2007; Wheeler & Priddel, 2009). Climate change is expected to exacerbate these pressures by reducing precipitation, increasing the frequency and intensity of periods with hot temperatures and consequently leading to more droughts and wildfires (CSIRO and BOM, 2015; Garnett & Baker, 2021; Guerin et al., 2018; Head et al., 2014; Hughes, 2011; McKechnie & Wolf, 2010).

Malleefowl are diurnal and are predominantly ground-dwelling, flying only to roost in trees or escape predation (Benshemesh, 1992; Frith, 1962b; Priddel & Wheeler, 1997). They can spend up to 11 months a year (Frith, 1959) and 44% of daylight hours (Weathers & Seymour, 1998) at their breeding mound, with Frith (1959) observing maximum distances of 230 and 90 m from the mound for females and males respectively. Non-breeding Malleefowl move further, and adult Malleefowl have been observed up to 11 km from their mounds, some after a wildfire destroyed their habitat (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1985). Home range estimates vary widely from 3 to 370 ha for breeding and from 170 to 240 ha for non-breeding birds (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1987a). Little is known of Malleefowl movement when they are not breeding and are thought to be less closely associated with their mounds (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1985).

The size and proximity of habitat patches and environmental variables may influence movement patterns. Many Malleefowl live in areas of fragmented native vegetation scattered within a matrix of agricultural land. How Malleefowl move between habitat patches and use cleared agricultural land is largely unknown although they have been observed feeding at the edge of wheat paddocks (Short & Parsons, 2008; van der Waag, 2004) and in roadside vegetation strips, suggesting roadside vegetation may facilitate movement between habitat patches (Benshemesh, 2007). The ability of Malleefowl to move and disperse within and between habitat patches is critical to their survival, especially after drought, heatwaves or wildfire, all of which are predicted to increase in frequency. Understanding how such environmental factors influence movement patterns is thus imperative for implementing actions to protect or improve refuge habitat to enhance Malleefowl survival. Malleefowl have a heat tolerance of approximately 41–42°C (Booth, 1984), and above these temperatures, they show heat dissipation and avoidance behaviours like panting, gular fluttering, seeking shade and increasing rest periods (Benshemesh, 1992). These behaviours can lead to reduced foraging efficiency, loss of weight and overall condition in birds (McKechnie, 2019; van de Ven et al., 2019), but movement has not been studied in this context. Reduced movement is a known technique used to reduce heat stress in other animals (Shepard et al., 2013) and arid-zone birds have shown reduced activity at high temperatures (Pattinson et al., 2020). Reduced activity could lead to less time tending mounds or foraging, negatively impacting hatching success, recruitment and survival.

An understanding of how extrinsic and intrinsic factors influence movement patterns is essential to inform the appropriate scale of regional management. Most knowledge of Malleefowl ecology and behaviour comes from mound-based surveillance using cameras or direct observation (Benshemesh, 1992; Frith, 1962b; Neilly et al., 2021; Priddel & Wheeler, 2003; Weathers & Seymour, 1998). Malleefowl are well camouflaged and have acute hearing (Bellchambers, 1916), making them difficult to observe away from the mound. An initial understanding of Malleefowl movement ecology and time budgets was gained by using VHF radio tags (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1985, 1987a; Priddel & Wheeler, 1996). In these studies, although transmitters were attached for up to 2 years, data were recorded intermittently and only for up to 15 consecutive days, and some transmitters could not be located after short periods. Benshemesh (1992) and Booth (1987a) lost 30% and 50% of VHF-tagged adults respectively. These losses are indicative of the limitations of VHF tracking, as it is difficult to keep frequent track of birds on the ground for long periods, especially if they move out of their existing range. Malleefowl are difficult to catch and handle as they are prone to stress and become wary after capture, changing their movement patterns and making it difficult to collect unaffected movement data (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1987a). This is problematic as patchy data can cause inaccurate home range estimates (Silva et al., 2018).

Solar-powered GPS trackers can be fitted to birds for long periods with remote data download and without the need for recapture, thus enabling the collection of continuous fine-scale data. We fitted GPS transmitters to Malleefowl in a semi-arid environment to compare movement patterns during the breeding and non-breeding period and investigate the influence of patch size and environmental variables. We predicted that patch size would limit movement and that Malleefowl would rarely use cleared land. We also predicted that Malleefowl would move less with increasing temperatures to avoid heat stress. How Malleefowl use and move between habitat patches in agricultural matrices can inform managers about the size and distance between remnant patches that are required for the protection and persistence of Malleefowl. How much time Malleefowl spend in open agricultural land and the maximum distance they will move across open landscapes may inform about the position of functional habitat corridors connecting remnant patches and how matrix habitat can be augmented to improve dispersal (e.g. planting paddock trees as stepping stones or improving road-side vegetation strips). It can also assist managers in timing their management actions to reduce disturbances such as exposure to chemicals via food plants.

METHODS

Study sites

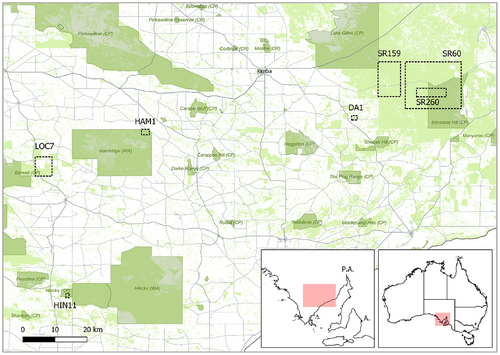

Study sites were on the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia (Figure 1), where Malleefowl persist in fragmented native vegetation patches. About 39% of native vegetation cover on the Eyre Peninsula remains, mostly in marginal areas unsuitable for agriculture (Brandle, 2010; NREP, 2017).

We trapped Malleefowl at six Mallee sites: Hincks and Hambidge Conservation Parks; one Heritage Agreement property near Lock (HA 370) and one near Cowell (HA 172), all with low to medium rainfall (320–400 mm); and at Secret Rocks Nature Reserve and a nearby private property (310 mm). Vegetation and rainfall details in SI1-Table S1.

Data collection

Malleefowl were trapped using a cage trap set on an active mound (i.e. while breeding) following Priddel and Wheeler (2003) but with a soft polyester nett top (see SI1: Appendix S1). Captured birds were fitted with solar-powered GPS transmitters (Solar Argos/GPS 30 g PTT, accuracy ±18 m; Microwave Telemetry Inc (2018)). High-resolution locations (fixes) were calculated 6–12 times a day (SI1) and transmitted via satellite (Argos CLS, 2021).

After capture, we determined whether birds returned to their mounds through GPS fixes and camera traps (HC600 HyperFire, Reconyx). In subsequent seasons, we determined breeding status through ground visits to areas with high-frequency fixes and cameras at mounds. Malleefowl were considered breeding when actively tending their mound, that is, visiting the mound at least every 2 days. They were considered non-breeding when they remained more than 100 m away from the mound for five or more successive days which included birds that abandoned their mound after capture as well as birds captured in one season that did not breed the following season. As capture causes stress and birds may subsequently move erratically, we disregarded all data until they returned to their mounds, or the first 3 days after capture if they did not. Two birds that died within 5 days of capture were excluded from all analyses.

Originally, home range was defined as the area an animal uses during its normal activities like foraging (Burt, 1943). Modern tracking technology added a temporal dimension, enabling us to determine the intensity of use of areas within the home range, known as the utilization distribution (UD; Worton, 1989). Here, we use the term home range for the 95% UD (areas used 95% of the time), estimated with dynamic Brownian bridge movement models (dBBMM; Kranstauber et al., 2020). dBBMMs perform better in estimating home ranges than other methods by strongly reducing type-2 errors (inclusion of unused areas), allowing for irregular sampling, behavioural heterogeneity and high data volumes (Kranstauber et al., 2012; Walter et al., 2015). For comparison with previous studies, we calculated the 95% minimum convex polygon (MCP) with adehabitatHR (Calenge, 2006). Total range length was the linear distance between the two most distant fixes per patch, breeding stage or the whole tracking period.

Movement patterns

To investigate Malleefowl movement patterns, we calculated a range of summary statistics using days where at least 75% of scheduled fixes were successful (SI1: Appendix S1). A ‘bird day’ was 24 h beginning just before the first dawn record. We recorded the daily distance (sum of all distances moved between fixes (non-linear) for a bird day), daily nett displacement (the distance between the first and last fix of that bird day, the greater the nett displacement, the greater the directionality of movement; henceforth daily displacement); distance to mound (distance from a fix to the current mound when breeding and the previous season's mound if not breeding, maximum distance from the mound for daily statistics) and hourly nett movement (henceforth hourly movement; straight line distance between two consecutive fixes (m) divided by the time (h) between the same two fixes). Further details about time-of-day determination can be found in (SI1: Appendix S1).

We also investigated the occurrence and frequency of Malleefowl long-range movements. Movement was considered as long range when the daily displacement of a bird exceeded four times the mean daily displacement of all birds (502 m). Long-range movements could be excursions or dispersal. We defined excursions as temporary exploratory movements outside of the home range, with an endpoint within the home range (Dingle & Drake, 2007; Earl et al., 2016) and dispersal as more permanent movements, with an endpoint outside of the home range, resulting in settlement in a new habitat and typically (but not necessarily) followed by reproduction (Clobert et al., 2012).

Effect of breeding status and patch size on home range and total range length

We investigated the effect of breeding and patch size on home range and total range length. We modelled the response variables separately as a function of patch size using multiple linear regression. We used breeding status (breeding/non-breeding) and patch size and their interaction term as the main effects. Response variables and patch size were log-transformed to fulfil model linearity assumptions and improve model fit. To reduce the influence of short tracking periods, we only used patches where birds remained for 12 or more days. Patch size was the size of the area of uninterrupted remnant native vegetation available to each Malleefowl.

Effect of breeding status, season and time of day on movement metrics

We used linear mixed-effects models to examine the effects of breeding status, seasons and time of day on movement metrics. We used bird-ID as a random effect to allow for individual differences. For daily movement, the response variables were daily distance, daily displacement and daily maximum distance to the mound. The fixed effects were breeding state, season (spring/summer/autumn/winter) and their interaction term. For hourly movement, the response variables were distance per hour. The fixed effects were breeding state, time of day (dawn/day/dusk/night) and their interaction term. Response variables were transformed (e.g. log, square root) to fulfil model linearity assumptions and improve model fit. Using the modelled data, we then estimated the marginal means and conducted a contrast analysis to test for significance of pairwise differences. We conducted this analysis separately on a data set with all birds (six males + one female) and a data set with only the six males to account for the uncertainty around the female's movements.

Effect of environmental factors on movement patterns

To examine the effects of temperature and rainfall on movement, we used generalized additive mixed models (GAMM). As one individual (DA1) was tracked over multiple seasons, we used a continuous correlation structure that tests for autocorrelation between subsequent observations within individuals. To allow for individual behavioural differences in different periods, we used an interaction term of bird-ID and breeding status as the random effect. The response variable was daily distance which was log (NB) and square root (B) transformed to fulfil model linearity assumptions. The fixed effects were maximum temperature (°C) and rainfall (yes/no). We then predicted daily distances travelled for maximum temperatures of up to 50°C on the population level (not taking into account individual variation).

Data analyses were performed with R Studio v1.4.1106 (R Core Team, 2020) with the following packages: tidyverse (data cleaning, plots; Wickham et al., 2019), nlme (mixed effect modelling; Pinheiro et al., 2006), DHARMa (model diagnostics; Hartig, 2022), MuMin (R2; Barton, 2019), emmeans (marginal means, contrasts, plots; Lenth, 2022), suncalc (times of day; Thieurmel & Elmarhraoui, 2019), effects and interactions (model plots; Fox & Hong, 2009; Long, 2019), mgcv (GAMMs, predictions; Wood, 2017) and gratia (GAMM appraisal, plots; Simpson, 2022). Maps were made with QGIS 3.16 (QGIS Development Team, 2021).

RESULTS

We trapped eight male and one female Malleefowl between December 2016 and December 2019. Of the nine tagged birds, seven died during the study. Two died within 5 days of release, one likely from stress and the other from fox predation but stress may have been a contributing factor. The remaining five birds died between 36 and 452 days after release. Three birds died from cat predation (one confirmed with DNA), one from fox or raptor predation and one probably of heat stress during a drought. An eighth transmitter stopped and the bird could not be found. Only one bird remained at the end of the study and had been tracked for over 1530 days. We collected a total of 20 932 GPS data points with a fix success rate of 88.8%, resulting in 18 645 successful fixes. One bird (DA1) had particularly low fix success rates in winters, with, at worst, no fixes recorded from May to July 2019 (Table 1). After data cleaning (Appendix S1: SI1), 17356 records remained.

| Location | ID | Tracking period | Days tracked | Fate | Day fixes | Night fixes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowell | COW17 | 15/02/2017–16/02/2017 | 1 | Suspected fox | - | - |

| Cowell | COW41 | 27/11/2017–03/12/2017 | 5 | Suspected fox | - | - |

| Yalanda | DA1 | 15/01/2017–25/03/2021 | 1530 | Alive | 5451 (77.5%) | 1401 (66.7%) |

| Hambidge | HAM1 | 01/12/2016–21/05/2017 | 171 | Cat | 912 | 250 |

| Hincks | HIN11 | 10/12/2016–15/01/2017 | 36 | Suspected cat | 196 | 32 |

| Lock (F) | LOC7 | 13/02/2017–22/10/2017 | 251 | Suspected fox/raptor | 1643 (99.8%) | 1239 |

| Secret Rocks | SR159 | 18/11/2018–17/11/2019 | 364 | Suspected heat stress in drought | 1795 | 568 |

| Secret Rocks | SR260 | 02/12/2017–27/02/2019 | 452 | Cat | 2307 | 656 |

| Secret Rocks | SR60 | 13/12/2019–17/11/2020 | 340 | Unknown | 1649 (99.9%) | 546 (31.2%) |

| Total | 3150 | 13 953 | 4692 |

- Note: We present the trapping location, bird-ID, tracking period and duration, cause of death (fate) and number (percentage) of successful day and nighttime fixes for each bird.

- Abbreviation: F, female.

Malleefowl spent at least 97.5% of their time in native vegetation. Three Malleefowl were caught at mounds that were within 300 m of agricultural land. DA1 was recorded moving up to 77 m onto agricultural land, but fixes on agricultural land accounted for only 1.3% of 5201 fixes (only October–March, as most complete monthly data). Fixes were most frequently found on agricultural land in November (2.5% of monthly fixes), followed by October (<2%) and December (1.5%), all just before and during crop harvesting time in December (confirmed by the landowner, pers. comm). In contrast, January–March only had 0.6%–0.9% of fixes on agricultural land. Only 1.5% of HAM1's fixes were on agricultural land and all fixes were less than 20 m from the edge of native vegetation, suggesting they could be an artefact of GPS inaccuracy (±18 m). LOC7, the female, only used agricultural land to cross to other patches of native vegetation.

Movement after capture

Capturing Malleefowl at their mounds affected their movement behaviour for various periods after trapping and only four males of the nine tagged Malleefowl returned to their mounds to resume breeding activities. Three of these birds returned after two (DA1), four (HAM1) and 11 (HIN11) days, and recommenced mound maintenance with their mate. Two of these three pairs completed their breeding activities, and the third pair (HIN11) continued until the tagged male died 36 days after release (the female continued tending the mound for 11 days afterwards). The fourth male (SR260) returned to the mound after 24 days by which time his mate, who had been tending the mound by herself for 8 days after his capture, had left the mound. He resumed mound tending activities (i.e. was considered breeding) by himself for a further 22 days (SI2-Table S2).

The five birds that did not return to the mound (i.e. were considered non-breeding) included the female that was tracked for 251 days, two males that were tracked for around a year each and two males that died within 5 days of capture.

During the 3 days after capture that were removed from analyses, the two males that did not return to their mounds moved up to 1500 m and the female up to 1280 m from the mound. Of the four males that did eventually return to their mounds, SR260 moved over 3.2 km away from their mound in the first 3 days, while the other three stayed within 1000 m.

In the week before trapping, of the males that returned to their mound, SR260 was recorded at the mound daily by camera trap (for 4 days only, as the SD card was full before that for about 4 weeks, before which the mound was tended daily), DA1 daily except on 1 day, HIN11 on 2 days and HAM1 was not recorded at all as the camera was only set up 2 days before capture. Of the birds that did not return after capture, LOC7, SR159 and COW41 were at the mound every day in the week prior to capture, COW17 was there on all but 2 days and SR60 was only seen once the day before trapping. Camera trap photos indicate that all non-tagged breeding mates continued visiting the mound when their mates were absent (SI2-Table S2).

Home range and total range length

Malleefowl home range and total range length were influenced by breeding status and patch size. Non-breeding home ranges of all seven Malleefowl averaged 609 ha (±708 ha s.d.) and ranged from 41 to 2168 ha. Breeding home ranges were much smaller, averaging 92 ha (±43 ha) and ranging from 44 to 176 ha (Table 2). The female had the largest breeding home range (176 ha) compared with the three breeding males (44–100 ha) but low sample size precluded statistical significance. The female used three patches but two were excluded to reduce the influence of short tracking periods (SI2-Table S3). All six males remained within one patch.

| Home range | Total range length | Daily distance | Daily displacement | Distance to mound | Hourly movement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Max | Mean ± SD | Max | Mean ± SD | Max | Mean ± SD | Max | ||

| F | B (1) | 176 | 2.2 | 1830 ± 517 | 2956 | 566 ± 324 | 1396 | 470 ± 267 | 1507 | 117 ± 82 | 484 |

| NB (1) | 234 | 4.7 | 1565 ± 557 | 3720 | 501 ± 378 | 1812 | 5599 ± 1178 | 7096 | 102 ± 96 | 697 | |

| M | B (7) | 79 ± 23 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1256 ± 596 | 3896 | 296 ± 247 | 1098 | 338 ± 326 | 2062 | 66 ± 78 | 537 |

| NB (7) | 591 ± 721 | 5.7 ± 5.6 | 1571 ± 880 | 10 394 | 647 ± 686 | 9738 | 2639 ± 2670 | 12 969 | 87 ± 98 | 959 | |

| All | B | 92 ± 43 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1283 ± 605 | 3896 | 310 ± 258 | 1396 | 349 ± 324 | 2062 | 69 ± 79 | 537 |

| NB | 609 ± 708 | 6.1 ± 5.3 | 1567 ± 841 | 10 394 | 624 ± 653 | 9738 | 3293 ± 2715 | 12 969 | 89 ± 97 | 959 | |

- Note: We present sex (F, female; M, male); breeding stage (B, breeding; NB, non-breeding (number of stages used for analyses)); home range (95% UD, ha); total range length (km); and mean ± 1 SD and maximum of daily distance, daily displacement, distance to mound and hourly movement (m). Maxima for each sex are in bold. Details in SI2-Table S3. Please note that only one female was tracked overall and only three males while breeding, one of which was tracked over five consecutive seasons.

Total range lengths varied from 0.9 to 14.4 km when not breeding and were larger than when breeding (1.1–2.4 km). The greatest total range length for the complete tracking period was 23.1 km for a male (SR60). The female's total range length over the complete tracking period was 7.8 km (SI2-Table S3).

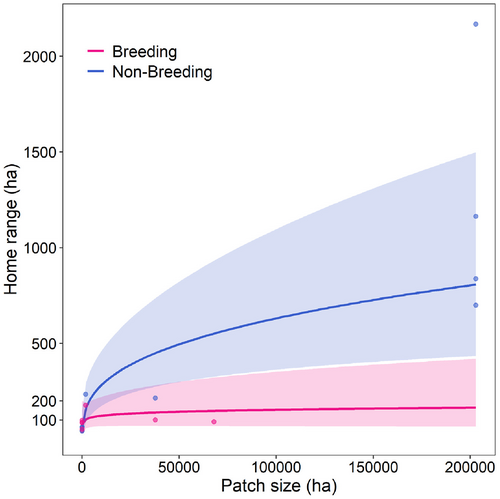

Over 83% of the variation in home range size (R2 = 0.858) and total range length (R2 = 0.835) could be explained by the factors in the multiple regression. Models showed that breeding status and patch size were significant predictors of both home range size and total range length. Home range size was positively related to patch size for non-breeders (r = 0.32, 95% CI [0.15, 0.49], p < 0.001, n = 17), but not for breeding birds (p = 0.3, Figure 2). Home ranges (r = −1.79 [−3.15, −0.43], p = 0.01) and total range lengths (r = −1.48 [−2.59, −0.38], p = 0.01) were significantly smaller at small patch sizes during non-breeding periods but not while breeding (SI2-Table S4; Figure S1). For example, DA1 (tracked 1530 days) was resident in a 107 ha patch and his home range never exceeded 98 ha. In contrast, SR60 (tracked 337 days) lived in a patch of over 200 000 ha and his non-breeding home range was 2168 ha.

Movement metrics

Overall, Malleefowl moved on average 1453 ± 768 m (mean ± 1 SD) per day, 81 ± 91 m per hour and while they stayed within 349 ± 324 m of their mound when breeding, they effectively disassociated from the mound when not breeding (SI2-Table S3).

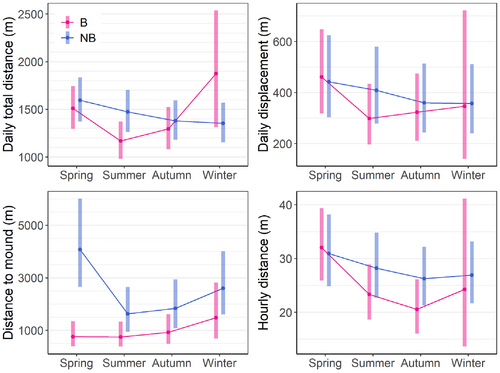

Movement patterns changed significantly depending on the birds' breeding status. Models also showed interaction effects of breeding status and season on daily movement and distance to mound, as well as interaction effects of breeding status and time of day on hourly movement and distance to mound (Figures 3 and 4, SI2-Table S6).

Daily total distance

In summer, breeding Malleefowl (M + F) moved significantly less per day (1164 ± 610 m) than non-breeding birds (1626 ± 893 m; p < 0.001, R2 = 3.8; Figure 3, SI2-Figure S3, Table S7).

All breeding Malleefowl moved significantly less per day in summer (All: 1164 ± 610 m) than in spring (M + F: 1486 ± 559 m; M: 1427 ± 546 m; p < 0.001), autumn (All: 1253 ± 559 m, p < 0.001; M: p = 0.027) and winter (All: 1762 ± 481 m, p = 0.038; M: p = 0.025; SI2-Figure S4 and Table S8). Non-breeding Malleefowl (both datasets) moved most per day in spring (1770 ± 1135 m), which was significantly further than in autumn (M + F: 1473 ± 657 m; M: 1463 ± 678 m) and winter (M + F: 1504 ± 749 m; M: 1475 ± 804 m; p ≤ 0.039; SI2-Figure S4, Tables S5 and S8).

Daily displacement

In summer, breeding Malleefowl (M + F) moved less directionally, that is, they had lower daily displacement (280 ± 246 m) than non-breeding Malleefowl (NB: 651 ± 568 m; R2 = 2%; p < 0.001; Figure 3, SI2-Figure S3, Table S7). In contrast, daily displacement did not significantly differ in other seasons nor in males (SI2-Figure S3, Tables S5 and S7).

Breeding Malleefowl (both data sets) moved more directionally in spring (384 ± 286 m) than in summer (280 ± 246 m) and autumn (259 ± 191 m; p ≤ 0.004). Non-breeders also moved more directionally in spring (850 ± 1025 m), significantly more than in autumn (522 ± 466 m; p = 0.05) and winter (581 ± 560 m; p = 0.04). In contrast, daily displacement did not significantly differ between seasons for non-breeding males (SI2-Figure S4, Table S8).

Distance to mound

Non-breeding Malleefowl across all seasons were located on average nearly an order of magnitude further from the mound than breeding birds (NB: 3292 ± 2715 m; B: 349 ± 324 m; SI2-Table S3; R2 = 31%; p < = 0.043; Figure 3, SI2-Figure S3, Table S7). Breeding males were closer to the mound than non-breeders in all seasons (p < 0.001) except winter. This may be due to limited data availability for breeding birds in winter (7 days).

Breeding Malleefowl were closer to the mound in summer (576 ± 329 m) than in autumn (653 ± 287 m; p = 0.011) and winter (1065 ± 49 m; p = 0.045). Summer had a stronger effect on breeding males (p ≤ 0.01) and they could be found closer to the mound in summer (576 ± 329 m) than in spring (697 ± 275 m), autumn (653 ± 287 m) and winter (1065 ± 49 m). Non-breeding Malleefowl (both data sets) were furthest from their last used mound in spring (5290 ± 3490 m) than in other seasons (p < 0.001; SI2-Figure S4, Table S8).

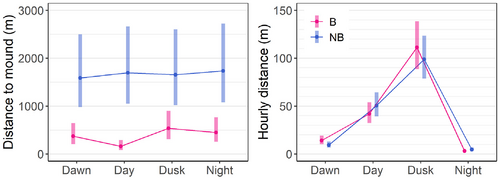

Breeding Malleefowl were significantly closer to the mound than non-breeders at all times of the day (p < 0.001, R2 = 35.1%) and could be found on average between 240 ± 288 m away from the mound during the day and 493 ± 314 m from the mound at night (Figure 4). This finding was the same for the males-only data, but the model explained less of the variation (R2 = 18.3%; SI2-Figure S3, Table S7). The males were closest to the mound during the day (217 ± 278 m) and furthest at night (509 ± 321 m; SI2-Table S5).

Breeding Malleefowl were closest to the mound during the day (M + F: 240 ± 288 m; M: 217 ± 278 m; Figure 4), significantly further away at dawn (M + F: 406 ± 315 m; M: 408 ± 316 m), further yet at dusk (M + F: 492 ± 321 m; M: 494 ± 324 m) and furthest away at night (M + F: 493 ± 314 m; M: 509 ± 321 m; SI2-Figure S4, Table S8; p ≤ 0.001, except dusk vs. night for males). Non-breeders (M + F), were significantly closer to the mound at dawn (3068 ± 2771 m) than at night (3668 ± 2689 m; p = 0.024; SI2-Figure S4, Tables S5 and Table S8).

Distance per hour

While non-breeding Malleefowl moved significantly further per hour than breeding Malleefowl in both summer and autumn (p < 0.001; R2 < 1%), the differences in autumn (B: 48 ± 67 m; NB: 61 ± 81 m) were smaller than in summer (B: 53 ± 76 m; NB: 74 ± 101 m; Figure 4; SI2-Figure S3, Table S7).

Breeding Malleefowl moved furthest per hour in spring (M + F: 64 ± 77 m; M: 61 ± 74 m) which was significantly further than in summer (53 ± 76 m) and autumn (48 ± 67 m) for both data sets (p < 0.001; SI2-Figure S4, Table S8). Non-breeders also moved most per hour in spring (78 ± 109 m) and although this was significantly further than in autumn (48 ± 67 m) and winter (70 ± 84 m), the differences to winter were not very pronounced (p ≤ 0.044; Figure 4; SI2-Table S5).

Non-breeders moved significantly more per hour than breeding Malleefowl during the day and at night (R2 = 44%, p < 0.001; Figure 4, SI2-Figure S3, Table S7) and these differences were considerable (NB: 93 ± ± 95 m; B: 69 ± 81 m during the day and NB: 12 ± 0 m; B: 4 ± 8 m at night; SI2-Table S5). In contrast, during dawn and dusk, non-breeders moved less per hour than breeding birds (p ≤ 0.013), and while the differences at dawn were small (NB: 22 ± 34 m; B: 25 ± 34 m), they were larger at dusk (NB: 143 ± 109 m; B: 114 ± 77 m). Non-breeding males also moved further per hour than breeding males during the day and night (NB: 90 ± 95 m; B: 65 ± 79 m during the day and NB: 14 ± 23 m; B: 4 ± 7 m at night), but there was no effect at dawn and dusk and less variation was explained by the model (R2 = 41.5%; SI2-Figure S3, Table S7).

Both breeding and non-breeding Malleefowl moved furthest per hour at dusk (B: 114 ± 77 m; NB: 143 ± 109 m); less during the day (B: 69 ± 81 m; NB: 93 ± 95 m); less again at dawn (B: 25 ± 34 m; NB:22 ± 34 m); and least during the night (B: 4 ± 8 m; NB: 12 ± 20 m; p < 0.001; SI2-Figure S4, Tables S5 and S8).

Sex

As we only tracked one female, we refrain from statistical testing to compare the two sexes. Nonetheless, a few findings are worth presenting. The female travelled 1829 ± 517 m each day compared to 1256 ± 596 m for males (SI2-Figure S5A). The female's movements were more directional with 566 ± 324 m per day versus 296 ± 247 m for males (SI2-Figure S5B). The female moved 117 ± 82 m per hour and males 66 ± 78 m. On average, the breeding female was 470 ± 267 m away from the mound and the males 338 ± 326 m (SI2-Figure S5C). Interestingly, the breeding female was furthest from the mound during the day with 550 ± 238 m, while the males were the closest with 217 ± 278 m (SI2-Figure S6B). The non-breeding female could be found much further away from the last used mound (5599 ± 1178 m) than the non-breeding males (2639 ± 2670 m; SI2-Figure S5C).

Movement patterns

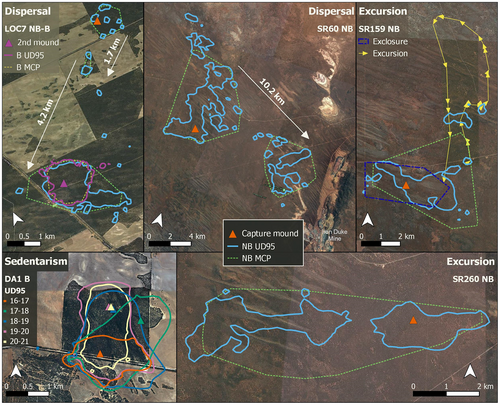

We observed three modes of movement in the Eyre Peninsula Malleefowl. Some birds were sedentary and did not move outside their home range, others showed short-term exploratory movements either within or outside of their home range, and others dispersed to new areas. Dispersal and excursions occurred almost exclusively when birds were not breeding, and the extent of these movements seemed to be influenced by patch size.

Dispersal

Dispersal was observed in two non-breeding Malleefowl. The female (LOC7) never went back to her mound after trapping and after 7 days left her initial patch. From there, she first moved to a small patch of native vegetation 1.7 km away, and after 3 days, moved to a large patch 4.2 km away, where she settled and maintained a mound in the following breeding season. As fixes were 2 h apart in each case, we cannot know the exact path, but the patches of uncleared habitat present suggested that the longest distance traversed in the open was about 250 m (Figure 5). LOC7 died 52 days into her new breeding season. SR60 also did not return to his mound after capture and moved to an area north of his trapping site for over 8 months where a home range was established of over 2000 ha. Ultimately, he resettled approximately 10 km away to the east of the capture site in September 2020 and established a new home range (Figure 5 and SI2-Figure S3).

Excursions

Exploratory movement with large daily displacement occurred much more frequently than dispersal. Three Malleefowl that lived in large habitat patches made short-term excursions outside and within their home ranges, almost exclusively while not breeding (exception: SR260 while single, i.e. tending the mound without its mate; see section Movement after capture). For example, SR159, in 362 days of tracking, had two excursions outside of his home range with a daily displacement of up to 9.8 km (Figure 5; SI2-Table S9). The second excursion was particularly noteworthy because SR159 travelled a linear distance of 10 km away from his home range before returning to it and dying 5 days later of suspected heat stress. SR159 also left and returned to the pest-proof exclosure (Details in SI1) it was captured in (Figure 5) on many occasions. In contrast, SR260 showed high displacement movement predominantly inside his home range. He initially frequently commuted between the western and central parts of his home range approximately 3–4 km apart. Later, from winter onwards, he ranged further and moved between the eastern and western parts of his range which were approximately 7 km apart (Figure 5; SI2-Figure S8). SR260 made a total of 21 long-range movements of 1–3 days with a daily displacement of up to 4.5 km in 426 days of tracking (SI2-Table S9; SI2-Figure S8). SR60 had 17 long-range movements of 1–2 days with a maximum daily displacement of 4.3 km in 337 days of tracking. Two excursions were outside the home range, of which one was part of a dispersal (Figure 5; SI2-Figure S7).

Sedentarism

The male in the smallest patch of native vegetation (DA1) was the most sedentary and showed no noteworthy exploratory behaviour. His average home range was the smallest at 64 ± 22 ha, and he very rarely left his 107 ha patch of native vegetation in 4 years (Figure 5). Two birds that lived in large patches, HAM1 and HIN11, also did not show exploratory behaviour.

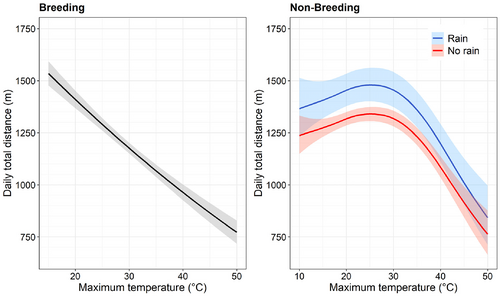

Environmental effects

A total of 30.5% of the variation in daily distances moved could be explained by the environmental data while breeding, where daily distance decreased with higher maximum temperature (Figure 6, SI2-Table S10). Rain did not improve this model and was therefore removed. When not breeding, GAMMs showed a non-linear relationship between maximum temperature, rain and the daily distance travelled, explaining 15% of the variation, with larger daily distances travelled when it rained and a strong decline when maximum temperatures were above 30°C (Figure 6). However, the effect of maximum temperature was not significant at the 5% level (p = 0.1); therefore we report relationship with low confidence.

While breeding, our models predict a daily movement of 1290 m [95% CI: 1260; 1321] at 25°C, 1067 m [1038; 1097] at 35°C and 865 m [819; 913] at 45°C. For a 1°C increase in maximum temperature from 24°C to 25°C, daily movement decreased by 1.8%, from 34°C to 35°C by 2% and from 44°C to 45°C by 2.2% (Figure 6).

While not breeding and with no rain, our model predicts a daily movement of 1317 [1280; 1355] at 30°C, 1229 [1188; 1272] at 35°C, 1081 [1031; 1133] at 40°C and 911 [839; 988] at 45°C. With rain, the model predicts a daily movement of 1454 [1372; 1541] at 30°C, 1357 [1274; 1446] at 35°C, 1193 [1106; 1288] at 40°C and 1005 [900; 1123] at 45°C. With or without rain, for a 1°C increase in maximum temperature from 29°C to 30°C, daily movement decreased by 0.7%, from 34°C to 35°C by 1.8%, from 39°C to 40°C by 3% and from 44°C to 45°C by 3.5% (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

We found that breeding status and patch size had the most significant influence on Malleefowl movement, together accounting for 83% of the recorded variation in Malleefowl movement. Breeding birds were more sedentary, always stayed within their home ranges and did not undertake any long-range movements. As a result, breeding birds had significantly smaller home ranges, shorter total range lengths, daily and hourly movement and remained closer to the mound than non-breeding birds. Average home range estimates of 92 ha (95% UD) and 83 ha (95% MCP) for breeding birds are smaller than those recorded by Booth (1985) (M: 260 ha, n = 1; F: 370 ha, n = 1) but larger than those of Frith (1962b) (M: 3–20 ha, F: 17 ha; n unknown) and Benshemesh (1992) (F: 49–75 ha, n = 2), possibly due to differences in rainfall, habitat or methodology.

When not breeding, the average home range size of tracked Malleefowl increased sixfold, daily displacement more than doubled to over 600 m and the average distance to the mound increased tenfold. These results support previous studies that found Malleefowl are tightly bonded (philopatric) to their mound while breeding and roam further from the mound when not breeding (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1985). Interestingly, overall mean daily movement increased to a much lesser extent when Malleefowl were not breeding, from 1.3 km per day when breeding to 1.6 km, but the highest daily movement and displacement were recorded in spring and the lowest in summer. This suggests that the distance travelled by Malleefowl each day is fairly consistent year-round but while breeding birds are highly attached to the mound in summer, when breeding activities usually peak, non-breeding birds move either for a longer period each day or in a more directional manner and roam over a larger area, especially in spring, which Malleefowl usually spend in preparation for breeding. This seasonal increase in movement and disassociation from the mound may enable Malleefowl to search for better nesting grounds, locate potential mates, escape disturbance or reduce pressure on food resources close to mounds. It may also reflect a decline in populations (see long-range discussion below). Such disassociation was suspected by Benshemesh (1992) when following non-breeding Malleefowl became very difficult, and our study shows Malleefowl can move up to 13 km from their breeding mound after breeding has finished. During breeding, the female moved considerably more, further from the mound and more directionally than males. Males remained closest to the mound during the day whereas the female was furthest from the mound at this time. This is consistent with the males' tighter bond to the mound than the females' (Neilly et al., 2021; Weathers & Seymour, 1998). Breeding females presumably move further to forage and cover the energy demand of egg production (Weathers et al., 1993; Weathers & Seymour, 1998). However, as only one female was tracked, it is hard to know if movement patterns of this individual were different because it was a female or for other reasons. For this reason, we refrained from statistical testing to compare the sexes and acknowledge that more research is needed to understand the influence of sex on movement patterns. However, due to the rarity and the cryptic nature of the species, we feel that presenting and contrasting the female and male data still has merit, but results should be treated with caution.

The consistent sedentary nature of Malleefowl recorded when breeding was unrelated to patch size. In contrast, a wider range of movement patterns was recorded when Malleefowl were not breeding including sedentarism (Berbert & Fagan, 2012), excursions (Bell, 1990) and dispersal (Clobert et al., 2012) which were related to patch size. One Malleefowl in the smallest patch of uncleared vegetation exhibited sedentarism when not breeding, but in contrast, long-range excursions were observed in three non-breeding Malleefowl. The three birds that displayed long-range movement were in the largest continuous native vegetation patch and were tracked for long periods (over 340 days), which may have confounded the results. Conversely, one male that was also in a large patch did not move long distances. However, a limitation of our study is our small sample size and low replication within each of the compared treatment combinations such as breeding versus non-breeding and large versus small patch size. For example, 77% of our non-breeding movement data came from three males in large continuous patches of mallee but 0% of our breeding data came from these three birds, leading to data asymmetries and strongly influencing movement metrics. Thus, our results may be reflective of individual-level differences rather than treatment effects. However, while acknowledging this limitation we feel it is still important to report the differences found to highlight areas for future research and to help formulate hypotheses for testing with larger sample sizes. Researching a threatened bird species that is cryptic and difficult to catch is challenging and our results should be interpreted cautiously. Mound activity has declined across the Eyre Peninsula over the last few decades and thus long-range movements may be an effort to locate mates where they occur in low densities. Other excursions are likely related to searching for food, water or familiarization with the surrounding topography (Bell, 1990). Malleefowl usually fulfil their water needs through food and drink little even when it is available; however, high ambient temperature may increase the need for water (Booth, 1987b). Two Malleefowl went to areas where satellite surface water records (CSIRO Data61, 2019) showed that water was present intermittently up until 2018 (but not at the time of excursion) in ephemeral lakes, dams and other surfaces. One Malleefowl died after an excursion to such an area in November 2019, the end of the driest year on record in South Australia. Drought-related Malleefowl deaths have been reported in the past (Priddel & Wheeler, 2003). Such excursions suggest these long-lived birds may have spatial knowledge over an area much larger than their home range, acquired over many years, as also suggested by Berbert and Fagan (2012).

Two Malleefowl dispersed during the study. The female resettled 7 days after being caught and commenced breeding in a new patch the following season. The female's late capture in the breeding season may have triggered dispersal, as late captures have caused cessation of egg laying and abandonment of breeding activities previously (Benshemesh, 1992; Booth, 1987a). However, a male dispersed only 9 months after capture and other captured birds did not disperse at all, suggesting dispersal may also be triggered by other events. Malleefowl are known to move to other mounds within continuous native vegetation due to habitat clearance, fire, trapping and available food sources, but some mound changes also appear to occur randomly as mounds abandoned by one pair after one season were used by another pair successfully in the next (Benshemesh, 1992; Frith, 1959). Only Benshemesh (1992) reported the ‘emigration’ (i.e. dispersal to new patches) of four Malleefowl after a fire. In contrast, Frith (1962a) reported that most Malleefowl struggle to colonize new areas when their habitat is heavily cleared and perish. Seasonal movements and (predominantly female) long-range dispersal in other medium-sized ground-dwelling birds that live in similarly fragmented habitats highlight the importance of dispersal in population connectivity and resulting gene flow (Earl et al., 2016; Vogel, 2015).

Our trapping clearly influenced the movement behaviour of the birds that did not return to their mounds after capture. These birds were classified as non-breeding as their association with their mound ceased. However, their behaviour may be different to birds that chose not to breed in subsequent seasons that were equally classified as non-breeding. If samples had been larger, these two groups would have ideally been separated into disrupted breeding and non-breeding groups. In future, we suggest trialling trapping birds in soft-sided cage traps away from the mounds using feeders to minimize disruption to breeding activity.

Although Malleefowl in our study were regularly recorded crossing unsealed roads up to 20 m wide, they very rarely used open agricultural land and only crossed cleared areas that were less than 250 m wide. Benshemesh (1992) also found Malleefowl used corridors of vegetation instead of travelling over burnt country. Avoiding open spaces is likely a self-defence mechanism against raptors, which have been reported to attack Malleefowl (Korn, 1986; Priddel & Wheeler, 1994, 1996) and caused Malleefowl to hide in dense scrub (Frith, 1962a). Although Malleefowl have been recorded at the edge of paddocks and roads feeding on grain (Benshemesh et al., 2020; Short & Parsons, 2008; van der Waag, 2004), our results show they rarely ventured into cleared areas and when they did, they remained within 80 m of uncleared vegetation.

While conservation preference is given to larger and connected vegetation patches (Margules & Pressey, 2000; Moilanen et al., 2005), research shows that smaller, fragmented patches are also important and have high conservation value (Fahrig et al., 2019; Volenec & Dobson, 2020; Wintle et al., 2018). One Malleefowl in our study remained in an isolated 107 ha patch of vegetation for 4 years and maintained a mound each year suggesting that relatively small habitat patches can represent important habitat for the species. Benshemesh et al. (2020) found Malleefowl had higher breeding activity in smaller rather than larger patches. However, although Malleefowl were able to persist and breed in small patches, these isolated patches restricted movement, particularly when not breeding. The effect of this restriction is unknown but is likely to include difficulty in recolonizing patches after fire or drought, inbreeding depression and increased risk of extinction due to stochastic events (Lacy, 2000). Research on other ground-dwelling birds has shown that occupancy is related to patch size and proximity to other patches (Bollmann et al., 2011). We, therefore, encourage conservation managers to include and even emphasize the reconnection and restoration of small habitat patches which will not only benefit Malleefowl but biodiversity more broadly. Our results suggest that habitat patches should be as close as 250 m to facilitate dispersal.

Although movement patterns were strongly driven by breeding and patch size, temperature and rainfall had a significant influence on Malleefowl movement. The predicted reduction in movement is substantial. Malleefowl have a heat tolerance of around 41–42°C and start showing heat dissipation and avoidance behaviours above this temperature but can also show these behaviours at lower temperatures if they have to tend the mound unexpectedly at a time when they would normally be resting (Booth, 1985). High temperatures are detrimental to the survival and health of arid-zone birds (Conradie et al., 2019; van de Ven et al., 2020) and studies show how thermal refuges under taller vegetation are preferred by other gallinaceous birds to limit exposure to high temperatures (Carroll et al., 2015, 2017). With the number of days over 40°C predicted to double in South Australia by the end of the century (CSIRO and BOM, 2015), climate change will almost certainly have an impact on Malleefowl movement and flow-on effects on foraging and breeding success.

Our data showed a clear pattern of movement throughout the day. Birds were largely sedentary at their roost sites moved slightly more in the mornings, more again during the day and most at dusk. Many authors report peaks in activity in the late afternoon (Bellchambers, 1916; Benshemesh, 1992; Frith, 1957), which possibly reflects movement towards favoured roosting sites. Benshemesh (1992) and Frith (1959) also reported increased activity in the early morning, which we did not record. This is very likely because we can only measure the linear distance between two fixes and any divergent movement is missed, meaning the linear distance between fixes is unlikely to reflect the actual movement and thus is not suitable for inferring activity as such. For the same reason, our study has recorded far shorter daytime distances moved than Weathers and Seymour (1998), who, through continuous observation, calculated an average walking speed of 1.2 km/h (maximum 8.3 km/h) and a daily travelling distance of 2.1 km. However, walking per se only made up 12% of their birds' daily activities. We recorded the greatest linear movement during the day, while other studies report Malleefowl resting more in the middle of the day, typically in the shade, due to hot ambient temperature or after prolonged periods of digging (Frith, 1956, 1959; Weathers et al., 1993; Weathers & Seymour, 1998). This is likely because our daytime hourly distance was based on multiple fixes throughout the day and not solely on midday.

Movement patterns of Malleefowl, like other species, are likely related to social and resource patterns that were unable to be measured in this study. Resources are patchily distributed in arid and semi-arid environments which may account for some of the longer movements observed in our study; however, there was no obvious pattern discernible from the satellite images or ground visits (aside from the Malleefowl that died during drought conditions). Preliminary analysis of diurnal habitat use of three of the tracked Malleefowl found little influence of vegetation variables on movement (Stenhouse, 2022). Overall, all three Malleefowl in the Stenhouse (2022) study clearly preferred micropatches of mallee with tall canopies (likely as refuges from heat and predators and for roosting) and, to a lesser degree, less understorey cover. Furthermore, each bird avoided different ground cover plants (e.g. Triodia, Atriplex and Geijera), depending on availability, but there was a common preference for Eremophila and aversion for Senna. Further research needs to be conducted in this area to understand the motivation behind the movement patterns observed in the present study.

We observed high mortality in birds tagged for this study, with 67% dying within a year of tagging and most mortality caused by fox and cat predation. This supports past findings of high mortality in adults (Booth, 1987a; Priddel & Wheeler, 2003). For a long-lived bird that is thought to live for up to 25 years in the wild (Benshemesh, 2007), such a high mortality rate is concerning. Movement in unknown habitats (for dispersal) increases predation risk (Yoder et al., 2004) and habitat fragmentation increases nest predation (Kurki et al., 2000) in other ground-dwelling birds and may play a role. Only two individuals from this study survived for over 12 months: one in the smallest and one in the largest patch of habitat.

Our study was limited by a small sample size (seven birds, only one of which was female). Birds were wary and difficult to trap at the mound and changes in immediate post-trapping behaviour and mortality in some birds suggests that this method is not ideal for trapping Malleefowl. Individual Malleefowl reacted differently to capture; while some Malleefowl returned to their mounds after a few days, others only returned after 3 weeks and 55% never returned. The untagged breeding mates continued to tend the mound for up to 3 weeks when birds were missing. Loosening of the mound substrate regularly is crucial, as otherwise, the soil gets compacted and chicks will suffocate trying to get out of the mound (Benshemesh, 1992; Frith, 1959). However, Benshemesh (1992) observed chicks hatching up to 6–8 weeks after the parents deserted the mound after a fire. The effect of trapping on behaviour and mortality suggests that other methods like soft netting around all sides of the trap or drop-frame trapping should be considered. Once tags were attached to Malleefowl, they were well tolerated with one individual carrying a tag for over 4 years without any observed effect. We interpreted statistical results cautiously, as there were few samples in the intermediate patch size range, and the regression fit was largely driven by the largest patches. However, visual inspection confirms that most Malleefowl in larger patches travelled further and had larger home ranges. Furthermore, only three of the six males bred (one of which lived in the smallest patch and was tracked over five seasons), which led to asymmetries in the data sets, strongly influencing movement metrics.

In conclusion, Malleefowl movement in our study was influenced mainly by breeding status and the patch size of available native vegetation. We recorded high mortality due to predation from introduced predators. Malleefowl were closely tied to patches of native vegetation, only moving up to 250 m across cleared land and making very little use of cleared agricultural land. Movement patterns suggest that Malleefowl in low-rainfall areas such as the Eyre Peninsula may be seasonal nomads (Lenz et al., 2015) that are tightly associated with their mounds while breeding but move significantly further afield when not breeding to explore and disperse to new areas if patches of native vegetation were contiguous or closely spaced. Results suggest that even small remnant patches of native vegetation can support breeding Malleefowl pairs, although perhaps not indefinitely so as genetic processes may lead to inbreeding and extinction in bottlenecked Malleefowl populations (Priddel & Wheeler, 1999, 2005; Stenhouse et al., 2022). As Malleefowl are long-lived birds, their ability to move and disperse within and between habitat patches is critical to their survival and recolonization of patches after drought, heatwaves or wildfire, all of which are predicted to increase in frequency with climate change. More GPS tracking, particularly of female birds, would assist in determining the factors influencing survival but initial results suggest that controlling introduced cats and foxes, protecting and improving existing native vegetation through herbivore control and building corridors connecting remnant patches of vegetation to enable dispersal could improve Malleefowl conservation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Peri Stenhouse: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (supporting); project administration (lead); resources (lead); software (lead); validation (equal); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Katherine Moseby: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (supporting); methodology (lead); supervision (lead); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all volunteers who have generously assisted in the field: Barbara Murphy, Ned Ryan-Schofield, Anara Watson, Paul Fennel, Cat Lynch, and especially Kathryn Venning; Graeme Tonkin for helping with trapping and advice; Robert Wheeler for advice, help with transmitter attachment, trapping, providing the trap and comments on this manuscript; Alan Stenhouse, John Read and Greg Kerr for field assistance and comments on the manuscript and Joe Benshemesh for comments on the manuscript. We thank Dave C. Paton for advice and help with banding; Andrew Bennet and Raoul Ribot for their help with GPS transmitters and data; Zoos SA staff and vets, especially Dave McLelland, for helping with transmitter attachment trials; Jack Tatler for advice; Amelie Jeanneau for spatial data help; Steve Delean for his invaluable statistical support. Lastly, thanks to DEW staff for their continued support and to Eyre Peninsula landowners Allan Zerna, Ken Lamb and Jerry Perfit (Cowell); Robert & Jill Dart, Rex Eatts, Clive Chambers & Family (Yalanda); Dan Vorstenborsch (Hambidge); Jeff McLachlan and Andrew and Mark Arbon (Hincks); Peter Hitchcock (Lock) and Ecological Horizons (Secret Rocks) for assistance and access to/through their properties. We thank three anonymous reviewers for their thorough comments that improved the manuscript. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley - The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This project was undertaken with approval from the University of Adelaide Animal Ethics Committee (S-2016-105) and the SA Department of Environment and Water and the Environment (permits A26564-1 to 5).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.