The association of modifiable and socio-demographic factors with first transitions from smoking to exclusive e-cigarette use, dual use or no nicotine use: Findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children United Kingdom birth cohort

Lindsey Hines, Elinor Curnow and Hannah Sallis are joint senior authors.

Funding information: This work was supported by Cancer Research United Kingdom (UK) (PRCPJT-May21\100007); the Cancer Research UK Integrative Cancer Epidemiology Programme (C18281/A29019); and the Medical Research Council and University of Bristol Integrative Epidemiology Unit (MC_UU_00032/2 and MC_UU_00032/7). The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (217065/Z/19/Z) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). This publication is the work of the authors and will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper.

Abstract

Background and Aims

E-cigarettes can aid smoking cessation and reduce carcinogen exposure. Understanding differences in characteristics between young adults who quit smoking, with or without e-cigarettes, or dual use can help tailor interventions. The aim of this study was to describe first transitions from smoking and explore substance use, sociodemographic, and health characteristic associations with the probability of each possible first transition from smoking.

Design and Setting

Longitudinal birth cohort data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), conducted in the United Kingdom.

Participants

A total of 858 participants were included who reported tobacco smoking in the past month at age 21 during a questionnaire collected in 2013.

Measurements

The first reported non-exclusive smoking event following smoking, observed approximately annually between ages 22 and 30, was categorized as either no nicotine use, exclusive e-cigarette use, or dual use. Discrete-time subdistribution hazard models were used to examine associations between different covariates, including substance use, sociodemographic, and health characteristics, with the probability of each first transition from smoking. Analyses were adjusted for early-life confounders and weighted to mitigate bias.

Findings

Among participants, 52% stopped nicotine use, 27% reported dual use, and 9% used e-cigarettes exclusively. Smoking weekly or more (Subdistribution Hazard Ratio [SHR] = 0.28, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.22–0.35), having many friends who smoke (SHR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.50–0.81), and lower education (SHR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.52–0.90) reduced the likelihood of no nicotine use and increased dual use (frequent smoking SHR = 3.00, 95% CI = 1.96–4.59; peer smoking SHR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.07–2.24; education SHR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.03–2.90). Cannabis use (SHR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.49–0.92), drug use (SHR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.59–0.99), less exercise (SHR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.53–0.95), and early parenthood (SHR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.27–0.79) reduced no nicotine use. Higher BMI (SHR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.08–2.31) increased dual use.

Conclusions

In the United Kingdom, young adults who smoke frequently, have more smoking peers, have lower education, engage in drug use, exercise less, or become parents early appear to be less likely to stop nicotine use than other young adults who smoke. Frequent smoking, peer smoking, lower education, and higher body mass index also appear to be associated with increased dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco control approaches in the United Kingdom (UK) have achieved great success given smoking rates have been declining since records began in 1974 [1]. However, harm reduction is essential for individuals who smoke tobacco and have either struggled to quit or do not intend to. One potential harm reduction tool is electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), which may support smoking cessation. E-cigarettes are devices that heat liquid, often containing propylene glycol, vegetable glycerine, flavourings, nicotine and other additives, to form an aerosol that can be inhaled. The aerosol contains lower levels of selected toxicants compared to cigarette smoke [2]. When used for smoking cessation, nicotine e-cigarettes can be more successful than traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), nicotine-free e-cigarettes, or behavioural support alone [3, 4].

Since emerging on the UK market in 2007 [5], e-cigarettes have grown in popularity. An estimated 4.7 million adults in Great Britain used e-cigarettes in 2023, 56% of whom previously smoked, and 37% of whom currently smoke [6]. Recent reduction in smoking rates may be partly driven by the availability of e-cigarettes, which may attract people who would not have otherwise used NRT [7-10]. E-cigarettes have been regulated as consumer products as part of the UK Tobacco and Related Products Regulations since 2016 [11-13]. Recently the UK government and National Health Service pioneered a Swap to Stop campaign aimed to help people quit smoking by offering free vape starter kits and behavioural support [14]. However, not all people who smoke switch to solely vaping or use e-cigarettes to try to stop smoking.

When people continue to smoke alongside using e-cigarettes this is referred to as dual use. Dual use is associated with greater nicotine dependence and consumption of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes [15], may expose a person to similar levels of carcinogens as only smoking [16], and is unlikely to substantially reduce harm if it does not lead to quitting smoking [17]. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors associated with dual use to target those most in need of support to effectively use e-cigarettes to stop smoking.

Previous research has identified predictors of e-cigarette use, including higher tobacco dependence [18], smoking by friends or family and higher impulsivity [19], internalising mental health symptoms [20], drunkenness, energy drink use and poor academic achievement [21] and conduct problems [22]. Studies have also shown that e-cigarette use may be less persistent over time than cigarette use [23-25] and may facilitate a quicker transition to smoking abstinence [26]. However, much of this research has focused on adolescence or the entire adult age range, has limited follow-up data up to a few years and has focused on one or few predictors. This study adds to existing knowledge by using 8 years of multiple follow ups in a rich longitudinal dataset of young adults in the United Kingdom.

This study investigates differences in a broad range of characteristics between young adults in the United Kingdom who previously reported smoking and subsequently reported either using e-cigarettes exclusively or while smoking (dual use) or quit smoking without using e-cigarettes. Understanding the factors associated with different initial transitions from smoking can help identify target populations who are less likely to quit smoking or use e-cigarettes, or more likely to dual use.

Aims

This study aims to (1) report the first self-reported changes in nicotine use, including transitions to no nicotine use, exclusive e-cigarette use and dual use in participants who previously reported smoking in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC); and (2) explore the relative strength of associations between substance use, socio-demographic and health characteristics with the probability of each possible first transition from smoking.

METHODS

Participants

Pregnant women resident in Avon, United Kingdom with expected delivery dates between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992 were invited to take part in the study. Briefly, 14 541 women were initially recruited, resulting in 14 062 live births and 13 988 children alive at 1 year, and additional children were subsequently enrolled. The study has been described at length previously [27-31]. Further details related to the ALSPAC sample can be found in Text S1.

The eligible sample for the present analyses (n = 3290) consists of G1 participants in ALSPAC who responded to the 21+ questionnaire (administered from mid-December 2013 when participants were ~21 years of age) and reported whether they had smoked in the past 30 days. The analytic sample (n = 858) is limited to participants who responded ‘yes’ to smoking in the past 30 days. Of these 803 (94%) participants also reported their smoking and e-cigarette use behaviour at least once in a following timepoint. Attrition and selection into the sample is illustrated in Figure S1.

Design

This is a secondary analysis of ALSPAC, a longitudinal birth cohort survey. Data used in the present study were collected via self-reported questionnaires and clinic attendance. This analysis focuses on participants who had smoked in the past month at 21 years of age and subsequent nicotine use from 22 to 30 years of age.

Outcomes

Nicotine use status at each timepoint, where smoking and e-cigarette use data have been collected, (22, 23, 24, 28 and 30 years) was categorised as either ‘exclusive smoking’ (smoked in the past month but not currently using e-cigarettes), ‘no nicotine use’ (no smoking or e-cigarette use), ‘exclusive e-cigarette use’ (no smoking but currently using e-cigarettes) or ‘dual use’ (smoking and e-cigarette use). To note, we use the term ‘no nicotine use’ for conciseness, but this definition refers to the use of nicotine products assessed in this study (i.e. cigarettes and e-cigarettes) and does not consider other sources of nicotine.

The first transition following smoking at 21 years, if any, was determined based on the first reported non-exclusive smoking event (nicotine use status) during the 22- to 30-year time period. Participants' first-reported transitions from smoking were then derived by identifying the earliest follow-up (~1, 2, 3, 7 or 9 years after the 21+ questionnaire) at which either no nicotine use, exclusive e-cigarette use or dual use was reported. Those who only reported exclusive smoking by the final follow-up were assigned the maximum time. An illustrative example is shown in Figure S2.

Exposures

Exposures of interest were determined through discussion among the study team and examination of the literature. We have summarised relevant existing literature in Table S1. Eleven dichotomised substance use, socio-demographic and health characteristics were investigated, spanning a wide range of potential intervention targets. Available measures collected during or in the 3 years before the 21+ questionnaire were selected.

Substance use

Measures related to substance use include smoking frequency [smoked in past month but less than weekly (reference category) vs. weekly or more] at age 21 years, and frequency of binge drinking six or more units of alcohol [never, monthly or less (ref) vs. weekly or more], past year cannabis use frequency [never, not in the past year, less than monthly (ref) vs. monthly or more] and past year drug use [no (ref) vs. yes], all collected at age 20 years.

Social and socio-demographic factors

Measures related to social and socio-demographic factors include peer smoking, referring to the number of friends who had smoked cigarettes from 18 years of age until now [none, a few or some (ref) vs. most or all], educational attainment [degree-level (ref) vs. A-level, below or other], where A-level (‘Advanced Level’) qualifications typically follow General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations or equivalent, usually in the age range of 16 to 18 years, both collected at age 20 years, and early parenthood [no (ref) vs. yes] and neighbourhood deprivation, estimated via Townsend deprivation scores [least deprived quintile (ref) vs. more deprived quintiles], both collected at age 21 years.

Physical and mental health

Measures related to physical and mental health include body mass index (BMI) [less than 25 (ref) vs. 25 or more] and frequency of exercise in the past year [weekly or more (ref) vs. less than weekly], both collected at age 18 years, and depressive symptoms in the previous 2 weeks, estimated via Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) scores [less than 12 (ref) vs. 12 or more], collected at age 21 years. Higher scores on the SMFQ suggest more severe depressive symptoms, where a score of 12 or higher may indicate the presence of depression.

Confounders

Analyses were adjusted for four early-life confounders; sex assigned at birth [male (ref) vs. female], ethnicity [White (ref) vs. minority ethnic], average household income (Great Britain Pound) per week at age 11 [560+ (ref) vs. 430–559, 240–429, <240] and parental smoking [no (ref) vs. yes] reported by the mother and/or her partner when the participant was age 12 years. Although it is best to use precise terminology to describe the specific ethnicity of a person or group, these data were unavailable. Instead, ALSPAC derived ethnicity based on the reported ethnic groups of the mother and father. Here, we use ‘minority ethnic’ to refer to participants from all other ethnic groups combined when compared to participants with two White parents. This uses ‘minority’ in a United Kingdom context, but these groups often represent the global majority.

Statistical analysis

Data were cleaned and variables created using Stata (version 18) [32] removing participants who had withdrawn their consent by the time data were accessed. Statistical analyses and data visualisation were carried out in R (version 4.3.3) [33]. This study adhered to the STROBE guidelines for the reporting of observational studies (Table S2) [34].

Subdistribution hazard discrete-time models [35, 36] were used to gain insight into covariate associations with the probability of each first-reported transition from smoking. These models can accommodate competing risks in a discrete time setting where participants experiencing a competing non-exclusive smoking event remain in the risk set given nicotine use status is transitory. These models were used to investigate 11 substance use, socio-demographic and health characteristic (18–21 years) associations with the relative likelihood of each transition from smoking (22–30 years) over time. Results describe the relative change in the subdistribution hazard ratio associated with each characteristic adjusted for four baseline confounders. Further details related to the statistical analysis approach can be found in Text S2.

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to impute any missing data [37, 38]. Details on missingness and how it was dealt with in this sample [39] can be found in Text S3, Figures S3–S7 and Tables S3–S4. As the analytic sample is conditioned on smoking status and this may induce bias, downstream discrete-time survival analyses were weighted by the propensity of participants to report past-month smoking at age 21 years [40, 41]. This is described in Text S4 and illustrated in Figure S8.

There were limited data on subsequent transitions (i.e. after the first transition from smoking) hence the focus of the present study is on the first reported non-exclusive smoking event. However, all observed transitions are described in Text S5 and shown in Tables S5–S6.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

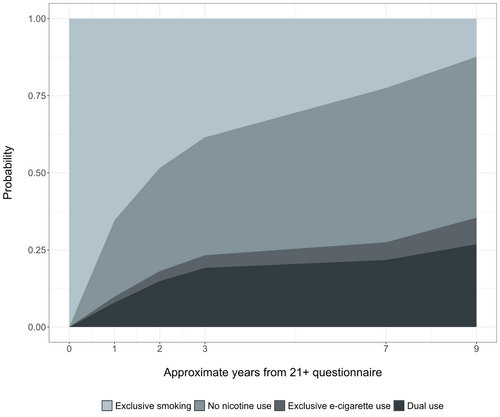

Reported exclusive smoking declined with time, while no nicotine use and e-cigarette use increased with time. Initially dual use was more commonly reported than exclusive e-cigarette use, however, at later timepoints similar proportions are observed (Figure S9).

In the analytic sample (n = 858), only 8% of participants reported being a parent at 21 years and only 4% had at least one parent from a minority ethnic background (Table 1). Frequency of exercise measured in the 18-year questionnaire showed the most missingness (44%) out of the investigated characteristics. Differences in participant characteristics by whether or not any transition was reported, and by each first transition from smoking can be found in Tables S7–S8. Table S9 shows differences in participant characteristics by the four included early-life confounders.

| Characteristic | Missing n (%) | Non-missing n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Early-life confounders | ||

| Sex assigned at birth | 0 (0) | |

| Male | 308 (36) | |

| Female | 550 (64) | |

| Ethnicity | 70 (8.2) | |

| White | 760 (96) | |

| Minority ethnic | 28 (3.6) | |

| Household income (11 y) | 207 (24) | |

| 560+ | 265 (41) | |

| 430–559 | 141 (22) | |

| 240–429 | 176 (27) | |

| <240 | 69 (11) | |

| Parental smoking (12 y) | 137 (16) | |

| No | 547 (76) | |

| Yes | 174 (24) | |

| Substance use | ||

| Smoking frequency (21 y) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Occasional | 312 (37) | |

| Weekly or more | 541 (63) | |

| Binge drinking frequency (20 y) | 228 (27) | |

| Never, monthly or less | 353 (56) | |

| Weekly or more | 277 (44) | |

| Cannabis use (20 y) | 215 (25) | |

| Never, less than monthly or not in past year | 489 (76) | |

| Monthly or more | 154 (24) | |

| Drug use (20 y) | 245 (29) | |

| No | 347 (57) | |

| Yes | 266 (43) | |

| Social and socio-demographic factors | ||

| Peer smoking (20 y) | 218 (25) | |

| None, a few or some | 261 (41) | |

| Most or all | 379 (59) | |

| Education (20 y) | 211 (25) | |

| Degree-level | 134 (21) | |

| A-level or lower/other | 513 (79) | |

| Being a parent (21 y) | 9 (1.0) | |

| No | 779 (92) | |

| Yes | 70 (8.2) | |

| Neighbourhood deprivation (21 y) | 23 (2.7) | |

| Least deprived quintile | 293 (35) | |

| More deprived quintiles | 542 (65) | |

| Physical and mental health | ||

| BMI (18 y) | 253 (29) | |

| <25 | 470 (78) | |

| ≥25 | 135 (22) | |

| Exercise frequency (18 y) | 375 (44) | |

| Weekly or more | 314 (65) | |

| Less than weekly | 169 (35) | |

| Depressive symptoms (21 y) | 30 (3.5) | |

| <12 SMFQ score | 653 (79) | |

| ≥12 SFMQ score | 175 (21) | |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (%); y, approximate years of age.

First self-reported changes in nicotine use

By the end of follow-up 12% of participants were still exclusively smoking and had not reported quitting or using e-cigarettes at any point (Figure 1). Of those with an observed non-exclusive smoking event, most first reported no nicotine use (52%) and a large proportion of initial transitions to no nicotine use occurred approximately 1 year following the 21+ questionnaire. Transitions from smoking to first using e-cigarettes were seen in 36% of participants and more participants reported dual use (27%) than exclusive e-cigarette use (9%).

Associations between characteristics with probability of each transition

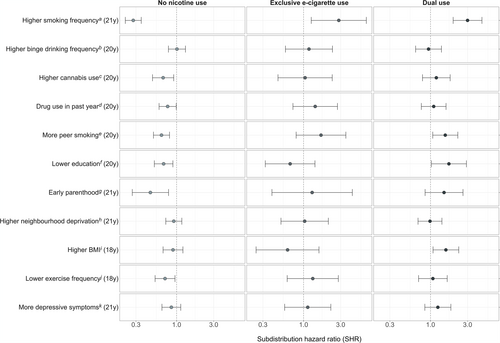

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the pooled results related to the 11 main characteristics of interest after adjustment for early-life confounders and weighting for selection via smoking. These are discussed below.

| Characteristic | No nicotine use (52%) | Exclusive e-cig use (9%) | Dual use (27%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 95% CI | P | SHR | 95% CI | P | SHR | 95% CI | P | |

| Substance use | |||||||||

| Smoking frequency (21 y) | |||||||||

| Occasional | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Weekly or more | 0.28 | 0.22–0.35 | <0.001 | 2.84 | 1.26–6.42 | 0.012 | 3.00 | 1.96–4.59 | <0.001 |

| Binge drinking frequency (20 y) | |||||||||

| Never, monthly or less | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Weekly or more | 1.01 | 0.78–1.30 | >0.9 | 1.17 | 0.58–2.36 | 0.700 | 0.94 | 0.64–1.38 | 0.800 |

| Cannabis use (20 y) | |||||||||

| Never, less than monthly, not past year | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Monthly or more | 0.67 | 0.49–0.92 | 0.013 | 1.05 | 0.47–2.34 | >0.9 | 1.19 | 0.79–1.79 | 0.400 |

| Drug use (20 y) | |||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.59–0.99 | 0.042 | 1.41 | 0.73–2.73 | 0.300 | 1.10 | 0.76–1.58 | 0.600 |

| Social and socio-demographic factors | |||||||||

| Peer smoking (20 y) | |||||||||

| None, a few, or some | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Most or all | 0.64 | 0.50–0.81 | <0.001 | 1.68 | 0.80–3.50 | 0.200 | 1.55 | 1.07–2.24 | 0.021 |

| Education (20 y) | |||||||||

| Degree-level | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| A-level or lower/other | 0.68 | 0.52–0.90 | 0.006 | 0.67 | 0.32–1.40 | 0.300 | 1.72 | 1.03–2.90 | 0.040 |

| Being a parent (21 y) | |||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.46 | 0.27–0.79 | 0.005 | 1.29 | 0.39–4.24 | 0.700 | 1.49 | 0.85–2.62 | 0.200 |

| Neighbourhood deprivation (21 y) | |||||||||

| Least deprived quintile | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| More deprived quintiles | 0.92 | 0.73–1.17 | 0.500 | 1.03 | 0.51–2.08 | >0.9 | 0.98 | 0.69–1.40 | >0.9 |

| Physical and mental health | |||||||||

| BMI (18 y) | |||||||||

| <25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ≥25 | 0.90 | 0.67–1.21 | 0.500 | 0.62 | 0.25–1.58 | 0.300 | 1.58 | 1.08–2.31 | 0.019 |

| Exercise frequency (18 y) | |||||||||

| Weekly or more | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Less than weekly | 0.71 | 0.53–0.95 | 0.023 | 1.31 | 0.62–2.80 | 0.500 | 1.07 | 0.70–1.64 | 0.700 |

| Depressive symptoms (21 y) | |||||||||

| <12 SMFQ score | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ≥12 SMFQ score | 0.86 | 0.65–1.13 | 0.300 | 1.13 | 0.57–2.24 | 0.700 | 1.24 | 0.85–1.83 | 0.300 |

- Abbreviations: e-cig, electronic cigarette; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio, SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire.

Substance use

Smoking frequency at age 21 years was the only characteristic associated with the probability of all possible first transitions from smoking. Participants who smoked weekly or more were less likely to transition to no nicotine use [subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR) = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.22–0.35], and more likely to first report exclusive e-cigarette use (SHR = 2.84, 95% CI = 1.26–6.42) and dual use (SHR = 3.00, 95% CI = 1.96–4.59) as opposed to a competing event or no event, at any given time, compared to participants who smoked less frequently.

There was no evidence to suggest binge drinking more regularly was associated with the probability of any transitions from smoking in this study. Participants who, at age 20 years, reported using cannabis monthly or more in the past year (SHR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.49–0.92), or using other drugs in the past year (SHR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.59–0.99) were less likely to transition to no nicotine use, as opposed to using e-cigarettes or continuing exclusive smoking, compared to those who did not use drugs. There was little to no evidence that other substance use was associated with the probability of first using e-cigarettes.

Social and socio-demographic factors

Participants who reported that most or all their friends smoked were less likely to transition to no nicotine use (SHR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.50–0.81), and more likely to first transition to dual use (SHR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.07–2.24) compared to participants with fewer friends who smoked.

Participants who reported having fewer educational qualifications at age 20 years were also less likely to first transition to no nicotine use (SHR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.52–0.90) and more likely to first report dual use (SHR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.03–2.90) following smoking, compared to those with higher education.

There was weak evidence to suggest peer smoking and education was associated with the probability of first transitions to exclusive e-cigarette use given the large amount of uncertainty reflected in the wide CI. However, the point estimate related to the association of peer smoking with exclusive e-cigarette use was similar as for dual use. Conversely the point estimate reflecting the association of education with exclusive e-cigarette use showed the opposite direction of association compared to dual use.

Participants who reported being a parent at age 21 years were less likely to first transition to no nicotine use (SHR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.27–0.79) compared to non-parents. There was little to no evidence that parenthood was associated with the probability of first using e-cigarettes.

There was no clear evidence to suggest neighbourhood deprivation at age 21 years was associated with the probability of any first transitions from smoking in this study.

Physical and mental health

Participants with a BMI over or equal to 25 at age 18 years were more likely to first transition to dual use (SHR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.08–2.31) than those with a lower BMI. There was little to no evidence that BMI was associated with the probability of first transitions to no nicotine use, or to exclusive e-cigarette use.

Participants who exercised less than weekly in the past year at age 18 were less likely to transition to no nicotine use (SHR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.53–0.95) compared to more active participants. There was little to no evidence that exercise frequency was associated with the probability of transitions to using e-cigarettes following smoking.

There was little to no evidence to suggest that higher depressive symptoms at age 21 years was associated with the probability of any first transitions from smoking in this study.

Other analyses

Results related to the four early-life confounders are shown in Table S10, but not discussed here as these coefficients cannot be interpreted as the effect of each on transitions from smoking because of mutual adjustment.

Results from unweighted, unadjusted and complete case analyses are shown in Tables S11–S13. Results from unweighted and unadjusted analyses were similar to those described above, while the unweighted complete case analyses showed some differences and are described in Text S3.

DISCUSSION

In a sample of young adults who smoked tobacco, this study explored predictors (18–21 years) of first reported transitions from smoking (21 years) to no nicotine use, exclusive e-cigarette use and dual use, in early adulthood (22–30 years) within a UK setting.

There were many barriers to stopping nicotine use identified, where complex lifestyle behaviours and stressors may make quitting tobacco use more difficult. Despite the increased prevalence of e-cigarette use amongst those who previously or currently smoked [1], some groups may not take up e-cigarettes such as people who exercise less, use drugs or became parents early. The continued use of tobacco in these groups is likely to exacerbate existing health inequalities as those using cannabis are at increased risk of mental health disorders [42, 43], the combined use of tobacco and lower physical activity has additive impacts on poor physical health [44], and continued use of tobacco amongst parents makes next generations more likely to smoke themselves [45]. Consequently, these groups represent key targets for smoking cessation and harm reduction interventions.

Several groups who were less likely to report no nicotine use were more likely to first transition to dual use. These include people who smoke more, have lower educational attainment, or more friends who smoke. Findings are mixed regarding harm reduction via dual use. There is evidence that dual use is related to reduced tobacco cigarette consumption [46], but other evidence indicates that dual use may not provide substantial harm reduction [16, 17, 47]. It is unknown whether these individuals used e-cigarettes with an aim of ceasing smoking, as previously reported motivations for dual use focus on pleasure rather than desire to quit [15]. Dual use may then reflect ambivalence toward quitting or an attempt to mitigate harm while maintaining nicotine dependence. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that dual use may be particularly common among people with more entrenched smoking habits or social influences, who may in turn not feel ready or able to fully quit smoking. Understanding how these groups can be encouraged to solely use e-cigarettes, which has lower impacts on health than dual use [47], is then an important step for public health. Our findings suggest that while smoking frequency and peer smoking may influence e-cigarette use generally, education and BMI may distinguish whether individuals exclusively use e-cigarettes or dual use. This supports previous work showing how e-cigarette use often co-exists with tobacco use within lower socio-economic groups rather than displacing it [48, 49].

Current research into e-cigarette use often focusses on individuals who previously did not smoke [50, 51], whereas our focus on individuals who already used tobacco fulfils important gaps in the literature and offers insights and implications for tobacco cessation and harm reduction. Current intervention to increase tobacco cessation focusses on a variety of strategies such as behavioural therapies [52], pharmacological treatments [53], financial incentives [54] and innovative digital approaches [55-58]. Tailored programmes that help people who smoke switch to less harmful alternatives to smoking and help people who dual use switch completely to e-cigarettes, could be developed and better promoted toward people who are more demographically vulnerable or dependant on cigarettes [59]. However, currently the effects of tailoring smoking cessation interventions for disadvantaged people have been limited [60], and programs that aim to integrate and address substance use, physical inactivity and smoking concurrently need to be improved [61]. Given e-cigarettes are providing a new avenue to help people quit smoking, where behavioural support combined with e-cigarette use has been shown to be particularly effective [62], it is important to ensure any ensuing reductions in smoking-related harms are equitable [63].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the length of follow-up data spanning young adulthood, the use of a phenotypically rich cohort with many measures of relevant risk factors, the use of a competing risk framework, and the use of multiple imputation and weights to mitigate complete case and selection bias, respectively, to garner more robust findings.

Limitations include the small sample size, measurement error where complex characteristics have been simplified and potential confounding or interactions between the characteristics being separately investigated. Left and interval censoring is another issue that may lead to less precise estimates. Current e-cigarette use before 22 years was not known nor the exact timings of reported first transitions from smoking. People who occasionally smoke might also exhibit fluctuations that do not necessarily indicate sustained transitions. Other sources of nicotine such as NRT were not investigated. Findings may also be subject to attrition bias as continued participation in ALSPAC has been shown to be non-random [64, 65].

The landscape of e-cigarettes in the United Kingdom is rapidly evolving and increasing in popularity [66] where the use of e-cigarettes within England among smokers and recent ex-smokers plateaued from 2013 to 2020, but has grown since [67]. This makes it difficult to understand the influence of participant characteristics independent of their current technological, social and political contexts.

Larger and better powered studies will be needed to investigate how characteristics such as depressive symptoms or neighbourhood deprivation, which may contribute smaller effects and vary over time, influence transitions away from exclusive smoking. Such studies could also be used to explore subsequent transitions between nicotine use states (e.g. no nicotine use after using e-cigarettes) via multi-state model analysis. Future work should also examine the complex interplay between different characteristics and motivations on quitting smoking or using e-cigarettes.

Implications

We identified many groups who may be less motivated or able to quit smoking, and likely need greater efforts from stop smoking interventions. Some groups, such as people with higher BMI, lower education or more peers who smoke, do appear to be using e-cigarettes, but often by combining e-cigarette use with tobacco and, therefore, may not fully benefit from their harm reduction potential. Other groups such as people who are less active or use other substances may not be engaging with e-cigarettes, or find it more difficult than others to feel encouraged to switch from smoking to vaping. Future policies and interventions should address the potential harms of dual use versus completely switching to e-cigarettes and encourage safer alternative sources of nicotine, especially if they are unable or unwilling to quit smoking unaided or with other nicotine replacement methods.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alexandria Andrayas: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (lead); visualization (lead); writing—original draft preparation (lead); writing—review and editing (lead). Jon Heron: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); supervision (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Jasmine Khouja: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Hannah Jones: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Hannah Sallis: Funding acquisition (lead); conceptualization (lead); supervision (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Marcus Munafò: Funding acquisition (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Lindsey Hines: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); supervision (lead); writing—review and editing (equal). Elinor Curnow: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (lead); visualization (lead); supervision (equal); writing—review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data used in this project and any resulting data from the analyses are available on request to the ALSPAC Executive Committee ([email protected]) and subject to a data access fee. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Bristol [68]. The study website contains details of available data through a fully searchable data dictionary and variable search tool: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and Local Research Ethics Committees (NHS Haydock REC: 10/H1010/70). Informed consent for the use of data collected via questionnaires and clinics was obtained from participants following the recommendations of the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee at the time. Consent for biological samples has been collected in accordance with the Human Tissue Act (2004). Data access for this project was granted (B3499/B4347) before this study. Datasets were created using syntax templates from the 25 January 2024.

The proposed analysis of data was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) here: https://osf.io/nuz5b. Deviations from this pre-registration are described in Text S6. The code used for data analysis is available in a github repository here: https://github.com/alexandrayas/ALSPAC_CRUK_smkvap/tree/main/Transitions%20from%20smoking.