Iterative categorisation (IC) (part 2): interpreting qualitative data

Abstract

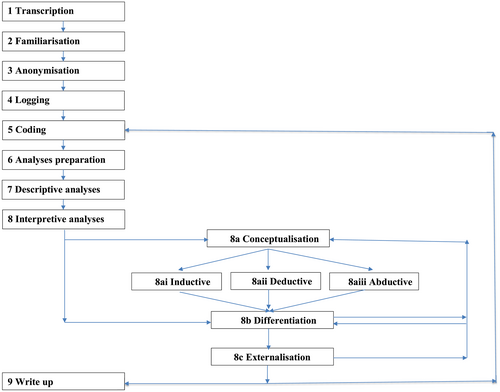

Iterative categorisation (IC) is a systematic and transparent technique for analysing qualitative textual data, first presented in Addiction in 2016. IC breaks the analytical process down into stages, separating basic ‘description’ from more advanced ‘interpretation’. This paper focuses on the interpretive analytical stage that is shown to comprise three core processes: (i) conceptualising (undertaken inductively, deductively or abductively); (ii) differentiating; and (iii) externalising. Each process is described, followed by published examples to support what has been explained. As qualitative analyses tend to be recursive rather than linear, the three processes often need to be repeated to account for all the data. Following the stages of IC will ensure that qualitative research generates improved understanding of the phenomena being studied, study findings contribute to and enhance the existing literature, the audience for any qualitative output is broad and international, and any practical implications or study recommendations are relevant to other contexts and settings.

Introduction

The analysis of qualitative data within addiction science and research more broadly is often poorly explained [1-3]. In 2016, Addiction published ‘Iterative Categorisation (IC): a systematic technique for analysing qualitative data’ within its Methods and Techniques series [2]. This paper has now been cited by qualitative researches working across a range of disciplines, and the technique has been demonstrated in talks and workshops internationally. Although qualitative analytic procedures are difficult to standardise, and there are multiple legitimate ways to undertake the analysis of qualitative textual data [1-4], IC offers researchers a rigorous and transparent step-by-step approach that increases the trustworthiness and potential reproducibility [5-7] of research findings. As the momentum for open science continues [8], accessibility and clarity are important for all methodological approaches in addiction science and beyond.

IC can be used with studies of any sample size and breaks the analytical process down into a series of largely sequential stages. These include ‘transcription’, ‘familiarisation’, ‘anonymisation’, ‘logging’, ‘coding, ‘analyses preparation’, ‘descriptive analyses’ and ‘interpretive analyses’. The initial 2016 IC paper covered all stages but focused predominantly on those prior to and including descriptive analyses. This second paper will elaborate on the more advanced interpretive stage; that is, how the researcher isolates emergent patterns, commonalities and differences in their data, explains both consistencies and inconsistencies, and relates their findings to a formalised body of knowledge. These processes are discussed in other qualitative analytical processes [4, 5, 9-11] but seldom described in any detail by researchers writing up their findings [2, 10]. Interpretation is essential because it raises the findings of a qualitative study from a simple, local ‘story’ to an account that has potential relevance to other settings and audiences [5, 6, 9, 11, 12]. To provide some context and background, the earlier stages of IC are first summarised; although the reader is advised to return to the 2016 IC paper for a fuller account.

Iterative categorisation (IC): a summary

The first aim of the analytical process is to begin to impose some order on any raw qualitative data [13]. If these comprise audio recordings from interviews or focus groups, they will need to be ‘transcribed’, ideally verbatim and to the level of detail required by the particular project and method [14]. If possible, fieldnotes (comprising descriptive information and researcher reflections) regarding a particular interview or focus group should be added to the top of that transcription so that all related data are in one document. All transcriptions and other textual material, such as more general fieldnotes or documentary materials, then need to be read and re-read to ensure that the researcher has ‘familiarised’ themselves with their content. After this, each transcription or document can be ‘anonymized’ using a simple but meaningful unique identifier (e.g. C01f might be used if the first participant recruited from study site C was female and C02m if the second participant was male). The anonymisation stage is to protect participant confidentiality while also ensuring that the researcher can easily recognize and locate the source of any data extract later in the analytical process. A robust system of ‘logging’ and storing study documents also needs to be established.

Next, the data are ‘coded’ (or ‘labelled’). This process can be conducted by pen and paper or by using a standard word processing package (e.g. Microsoft Word) or database (e.g. Microsoft Excel). However, coding is generally undertaken using a specialist qualitative software package, such as NVivo [15], MAXQDA [16] or Atlas.ti [17]. To this end, the data are loaded into the chosen software package, and codes are created to represent key issues, events or other phenomena of interest within the data. The data are then reviewed line-by-line and segments of text relating to each topic of interest are attached to the relevant codes. To facilitate a clear audit trail from the study aims and objectives (or research questions) to the study conclusions, coding in IC begins with the creation of deductive codes based on questions or topics raised by the researcher during the data generation stage. These can then be supplemented by inductive codes derived more creatively from topics or concepts emerging spontaneously in the data. The researcher should code the entire data set (‘complete coding’) [5], attaching segments of text to multiple codes as needed. On occasions, there may be a justification for ‘selective coding’ [5]; if, for example, a researcher wants to explore a particular aspect of the data in haste.

Before commencing more formal analyses, the researcher needs to embark on a simple but important preparatory stage. This involves exporting the coded data extracts from the qualitative software into a word processing package. Assuming the researcher is using Word, each code should have its own Word document. Therefore, a code labelled ‘cannabis’ in the qualitative software will now have a Word document labelled ‘cannabis codings’. The ‘cannabis codings’ document will include all of the data relating to cannabis, but the qualitative software will have appended document identifiers to every segment of text within the new Word document. This means that it will be possible to see the source of all data extracts at a glance. For example, a segment of text with the header ‘C01f’ clearly comes from the first study participant who was recruited from site C and was female, whereas a segment of text with the header ‘C02m’ is from the second study participant recruited from site C who was male.

Once the researcher is certain of the codes that need to be analysed to understand a particular phenomenon, each ‘codings’ document should be duplicated and labelled as a companion ‘analysis’ document. This would, for example, result in a ‘cannabis codings’ document and a ‘cannabis analysis’ document stored together in a ‘cannabis’ folder. Initially, both documents would contain exactly the same text. However, the researcher will next work on the analysis document(s) and leave the codings document(s) to one side for reference purposes only. To complete the preparatory stage, the newly created analysis documents are skim read by the researcher who might want to note down any immediate thoughts about the topics and themes within the data and how these interact. These are, however, only impressions, so are set aside whilst a more systematic inductive line-by-line analysis is undertaken. This is the start of the ‘descriptive analysis’.

During descriptive analyses, the researcher identifies important phrases, categories and themes in the data. This is achieved by working down each analysis document and reducing the content of each segment of text into bullet points. Each bullet point is written on a separate line and the source text identifier (e.g. C01f or C02m) is included at the end of each bullet point. Once a segment of text has been summarised, it is deleted leaving only the bullet point(s). As the researcher moves down the analysis document, bullet points that are similar can be grouped together or merged. Groups of bullet points can then be given headings and subheadings. At the end of this process, the researcher will be left with no original text. Instead, the analysis document will comprise headings and subheadings below which are summary bullet points where each bullet point is still linked to its original source by an identifier. The researcher can now review, rationalize and re-group all the points one further time to ensure a logical ordering or emerging narrative, usually with larger groupings of bulleted data appearing first. Findings can then be summarised in a few paragraphs of text at the top of the analysis document to complete the descriptive stage.

According to the 2016 IC article, the aim of the final interpretive process is to identify patterns, associations and explanations within the data. This is described in terms of finding themes that recur within and across the analyses documents; exploring whether and, if so, how themes can be recategorised into higher order concepts, constructs, theories or typologies; assessing the extent to which points, issues or themes apply to particular subsets or subgroups of the data/study participants; testing specific hunches or theories about the data; and finally, ascertaining how the findings complement or contradict previously published literature, theories, policies or practices. The 2016 paper notes that it is neither necessary nor possible to accomplish all of these goals with every analysis but provides limited detail regarding when or how different components of this stage should be executed. A more thorough account is now outlined below.

Interpretive analyses

In practice, the interpretive analytical stage comprises three core processes: (i) conceptualising; (ii) differentiating; and (iii) externalising. Whereas conceptualising is ‘recommended’, particularly for those working in more theoretical disciplines and contexts, differentiating and externalising should be undertaken during all studies. Conceptualizing is best performed before differentiating, and externalising is always best performed last. Nonetheless, the three processes often need to be repeated iteratively to account for all the data.

Figure 1 summarises IC, including the interpretive stage with its three core processes and their respective sub-components. Each process is described in turn below, and examples from the author's own published work are used to support what has been explained. This self-citation follows Sandelowski [18] who notes that she uses her own work as examples to avoid making false assumptions about the work of others, but also to capitalise on the ‘reflexivity’ by which researchers come to understand their motivations and choices. The reader may, of course, ascertain more detail about the examples by following up the original papers.

Conceptualising

Conceptualising is undertaken in one of three ways, (i) inductively; (ii) deductively; or (iii) abductively, depending on the epistemology of the researcher, the study aim/research question and the nature of the data generated. Using an inductive approach, the researcher reviews their descriptive themes and categories to identify more abstract concepts, constructs, or theory or even to develop a tentative typology or framework. This approach is most often associated with grounded theory [19, 20]. In contrast, the researcher who adopts a deductive approach assesses their descriptive themes and categories for evidence to support, refute or amend a concept, construct, theory, typology or framework specified before their analysis. This approach tends to be used by researchers who choose to bring an explicit world view, standpoint, perspective or heuristic to their research [18, 21]. Last, the researcher who deploys an abductive approach generates their descriptive themes and categories but simultaneously reads around the topic and wider literature to identify a concept, construct, theory, typology or framework that seems to fit their data best. This latter approach is particularly suited to applied research where a level of pragmatism is often necessary [22].

Inductive conceptualising

Inductive conceptualising is the least common approach to interpretive analyses using IC given that: (i) it is relatively rare for a single qualitative study to generate a completely new concept, construct, theory, typology or framework; and (ii) researchers can seldom disassociate themselves from all prior theoretical thinking or research on a topic before undertaking their own analyses [18, 22]. Indeed, a researcher who uses a topic guide to explore particular issues is de facto approaching their data with a range of assumptions. Nonetheless, using a slightly modified IC approach (whereby the data were initially analysed descriptively using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet rather than Microsoft Word documents), Neale et al. [23] constructed a proto-typology of opioid overdose onset. This was achieved by descriptively analysing first-hand accounts of non-fatal overdose and then grouping the findings to generate four types of overdose onset: ‘amnesic’ (no memory, rapid loss of consciousness and no description of the overdose experience); ‘conscious’ (some memory, sustained consciousness and a description of the overdose in terms of feeling unwell and symptomatic); ‘instant’ (some memory, immediate loss of consciousness and no description of the overdose experience); and ‘enjoyable’ (some memory, rapid loss of consciousness and a description of the overdose experience as pleasant or positive). The analyses highlighted the need for a range of interventions to address the different types of overdose onset and suggested that self-administration of the opioid antagonist naloxone might be possible in some contexts.

Deductive conceptualising

Deductive conceptualising, often based on sociological and psychological theories and frameworks, is relatively common in addiction research. Neale et al. [24] used the sociological concept of social capital [25, 26] to frame their analyses of relationships between peers in residential treatment. Data relating to residents' relationships with each other were assigned to codes labelled: ‘residents’, ‘buddy’, ‘peer support’, ‘community’ and ‘relationship changes’. The themes and categories emerging from the descriptive analyses of IC revealed how relationships between residents generated more negative than positive social capital, so undermining the notion of the community as a method of positive behaviour change in residential treatment settings. Meanwhile, Parkman et al. [27] deployed Andersen's Behavioural Model of Health Service Use [28, 29] to understand why people repeatedly attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons. Themes emerging from the descriptive analyses were mapped directly onto Andersen's model, showing how both ‘push factors’ (individual-level problems and wider community service failings) and ‘pull factors’ (positive experiences of, and beliefs about, emergency department care) contributed to repeated emergency department use.

Abductive conceptualising

The abductive approach to conceptualising recognises that qualitative data analysis is messy and non-linear. Therefore, there is no requirement for new theoretical insights to emerge directly from the data. Equally, the analyst is free to stray from their initial theoretical assumptions to pursue more interesting, lucrative or relevant theoretical avenues inspired by their descriptive analyses [22]. For example, coded data from a focus group study exploring heroin users' views and experiences of implants and depot injections for delivering long-acting opioid pharmacotherapy were grouped using IC, and new materialism theorising [30, 31] was only then identified by the research team as being useful for interpreting the findings [32]. The theory helped to explain why implants and depots are very complex medications with uncertain outcomes. In a separate study, unexpectedly detailed qualitative data generated from a free text box in a quantitative survey of sleep amongst people using alcohol and other drugs were reviewed line-by-line using IC and the results were inductively ordered under five headings [33]. These descriptive findings were then considered with reference to the Behaviour Change Wheel, a framework for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions [34], to inform the development of psychosocial interventions to improve sleep amongst people reporting drug and alcohol problems.

Differentiating

During the differentiating stage, the researcher works through their descriptive themes and categories, as well as any findings derived during conceptualisation, to check for similarities, differences or anomalies within individual data sources, between individual data sources and between subsets or subgroups of the data. For an interview study, this will include within individual participant's accounts, between individual participant's accounts and between the accounts of subgroups of participants [11]. If the data were generated from focus groups, the researcher will also be looking for similarities, differences or anomalies within and between focus groups, particularly if participants were recruited to specific groups based on demographic or other characteristics of interest.

Although this sounds like a Sisyphean task, the researcher needs to be pragmatic and select factors that seem most likely to be relevant based on their understanding of their data or their prior reading of the literature. For the most part, characteristics of interest will include participant gender, age, ethnicity and potentially one or two additional project specific characteristics. It is, however, important to caution that conclusions from this process can generally only ever be tentative because of non-random sampling and the small number of participants involved in most qualitative studies. Therefore, the researcher should endeavour to explain any evident consistencies or inconsistencies, but never over quantify their findings nor claim statistical differences [2]. The aim is simply to look for any notable patterns in the data, while also highlighting the limitations of qualitative research in this regard and the likely need for further empirical studies, particularly if the pattern has not previously been reported in the literature (see ‘externalising’ below).

Assuming that all transcriptions and other source documents had clear identifiers as recommended in the earlier anonymisation stage of IC and that the number of cases/participants is not too large, it should be relatively easy to see from the analysis document(s) whether one particular participant group (such as men or women or participants from site C as opposed to site A or B) repeatedly made the same point or points or if particular points were relevant to only one or two subsets of the data. To facilitate this process, it can also be useful to extend the source document identifiers at this stage by adding any extra qualifiers that might have emerged during the descriptive analyses as being of particular interest; for example, the letter H might be appended to all participants known to use heroin if the researcher now wanted to explore differences in responses between those who used or did not use this drug. Running a simple search and replace across the relevant analyses documents for the identifiers of all people known to use heroin can help to speed up this process (e.g. search ‘C01f’ and replace with ‘C01fH’).

In their analysis of residential treatment, Tompkins and Neale [35] conducted semi-structured interviews with staff and clients of a women-only residential rehabilitation service to better understand trauma-informed treatment delivery. Once the data had been analysed descriptively, similarities and differences within and between the accounts of the staff and the clients were reviewed. This revealed how the needs of staff and clients differed. Staff needed training, support and supervision to work with clients and to keep themselves safe. In contrast, clients required safety and stability to build trusting relationships with staff and to engage with the treatment. Parkman et al. [36], meanwhile, explored how people who frequently attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons use, view and experience specialist addiction services. When themes from their descriptive analyses were analysed for similarities and differences, they found that women were more likely to be receiving, and to want, support from a specialist addiction service than men. Although the authors cautioned that they could not generalize from their analyses, they noted that their findings might be relevant to other settings.

Externalising

The externalising stage is always essential to ensure that the researcher moves beyond a simple local account of their own data to give their findings relevance or meaning (also known as ‘transferability’ or ‘theoretical generalisability’ [5, 6, 9, 11, 12]) to other contexts or settings. Externalisation is similar to the ‘recontextualising’ process described by Morse [37] and is achieved when the researcher makes direct links between their own findings and established knowledge, thereby showing how their new analyses develop or challenge what is already understood about a topic [5, 18]. This established knowledge is generally found in wider literature relating to the topic of study, or to any specific concept, construct, theory, typology, framework, intervention, practice or policy featuring in their analyses. For those who have undertaken a deductive or abductive conceptualisation stage, some of this work will already be complete. Additional externalising can then be undertaken via a range of methods.

To begin, the researcher can return to literature previously cited in their research protocol and search for any new literature directly connected to their research topic or findings. If this proves limited or unsatisfactory, they can also identify and review literature from a cognate field or discipline to identify any useful links back to their own work. Additionally, the researcher can return to any notes or mind maps produced before the start of the descriptive analytical stage and check whether any of their earlier reflections are borne out in their findings, in this way generating inspiration for further literature searching. A researcher working within a particular theoretical tradition or branch of a discipline can also explore how their data are consistent with, add to, or contradict common assumptions in that field. Meanwhile, those working in more applied settings can review local, national and international policies, guidelines and service provision to see how their findings might relate to policy or practice. Relatedly, findings from a study of a particular intervention or service might be compared with other similar interventions or services or considered with reference to broader service commissioning processes to support, oppose or suggest changes to current service delivery.

When Neale and Strang [38] re-analysed a large historical data set comprising interviews conducted with people who had recently experienced an opioid overdose, they found that participants had limited knowledge of naloxone, although they routinely described it in negative terms and were critical of its medical administration. In contrast, observational data from the study indicated that participants did not always know that they had received naloxone and hospital doctors did not necessarily administer it inconsiderately. After reading around the literature (abductive conceptualising), the authors identified the concept of ‘contemporary legend’ [39, 40] as being helpful in explaining why people who used opioids were so afraid of naloxone. They then used their findings to make suggestions about the medical administration of naloxone within contemporary emergency settings. Specifically, they argued that good treatment involves building and sustaining trust with patients, providing clear information on how naloxone works, including its potential side effects, being sensitive to patients' likely fears and concerns and developing protocols on titrating naloxone dose against response to prevent acute withdrawal syndrome.

In a later study of a new innovation in residential treatment, Tompkins et al. [41] explored how welcome houses [42], which provide a relatively gentle introduction to the structured, rule-bound approach of therapeutic communities, affected treatment retention. The differentiating process, when applied to their descriptive analyses, suggested that welcome houses increased retention amongst people who had never been in residential treatment previously or who had complex needs. However, welcome houses appeared to decrease retention amongst people who were more stable at treatment entry. Drawing on the work of Goffman [43, 44], the authors concluded that welcome houses retained many of the core characteristics of total institutions but in an adapted ‘softer’ form better described by the term ‘reinventive institution’ [45]. Linking their findings directly to practice, the authors then argued that welcome houses should not be a mandatory stage within therapeutic communities. Rather, therapeutic community providers should consider each new resident's need for a welcome house as part of their assessment as this would help to ensure that an initiative that can increase retention for some does not inadvertently decrease retention for others.

Discussion

In the 2016 IC paper, descriptive analyses were presented as the quasi equivalent of running frequencies on quantitative data while interpretive analyses were described as the quasi equivalent of undertaking inferential statistics [2]. The point of this analogy was to emphasise that the qualitative researcher requires a basic descriptive understanding of the nature and range of topics and themes within their data set before they can advance to identifying meaningful patterns, categories or explanations and then relating these to a broader body of knowledge [11, 46]. In making this link with quantitative methods and in presenting the interpretive stage of IC as a series of relatively logical processes and components, the intention in this article has again been to help demystify qualitative data analyses. Nonetheless, as previously stated, analysing qualitative data is invariably creative and recursive rather than linear [4, 5, 9, 10, 46]. Accordingly, researchers are not expected to follow every stage and process of IC rigidly. On the contrary, they are encouraged to use the technique flexibly and even to adapt or develop components as needed [2].

As illustrated in Fig. 1 and described in the text above, the three processes of conceptualising, differentiating and externalising often need to be repeated. Additionally, it can be difficult to separate inductive, deductive and abductive approaches to conceptualising. Therefore, a researcher might undertake a deductive analysis based on an inductive finding (e.g. a finding emerges during the descriptive analyses and the researcher then decides to interrogate it deductively using a particular theoretical approach that interests them). Alternatively, they might undertake an inductive analysis of a deductive concept (e.g. the researcher codes their data using a particular concept but then analyses the data descriptively and interprets the finding with an open mind). Because a researcher may also formulate new ideas as they begin to write up their findings, they may additionally need to revisit earlier analytic processes at a fairly advanced stage in their study [4, 47]. It is important to note, however, that the actual sequencing of these events may be obscured in published qualitative articles because of the way that journals routinely require authors to present their work in linear stages [18].

The researcher starting their interpretive analyses will frequently have to make decisions about which codes and descriptive analyses documents to review to address their study aims, objectives or research questions or to better understand a specific concept, topic or issue in their data. Ideally, a researcher should analyse data from all study codes. Indeed, this is likely to be necessary when writing a thesis or major study report. Nonetheless, there will be occasions when it may not be possible or necessary to analyse every code or even to code all the data (see the reference to selective coding above [5]). Sometimes, the researcher will find that data from a single code have sufficient depth and detail to tell their own story and therefore potentially be the basis of a paper. On other occasions, the descriptive analyses from two or more codes may be interpreted in tandem to understand the phenomenon of interest.

When describing their analytical approach, the researcher always needs to be transparent [1, 2], but also often concise given the restricted word limit of many journals. Within the methods section of their paper or report, the researcher should explain the key IC stages and processes followed in as much detail as possible. In presenting findings, meanwhile, different disciplines have different traditions and expectations [5, 10]. Researchers writing for applied journals are likely to use the findings section to present their descriptive and differentiating analyses, documenting any themes or categories derived from the data as well as any apparent differences and similarities within and between subsets or subgroups of the data/study participants. Conceptualising and externalising can then be reserved for the article discussion and conclusion. In contrast, researchers submitting to sociological and theoretical journals are more likely to weave their descriptive and interpretive analyses together into one longer findings section. Regardless of approach, verbatim quotations that reflect the range of data sources or study participants can then be used to illustrate salient points [11].

As stated in the 2016 paper, IC is underpinned by concurrent data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing/verification [4]. In addition, it can support a range of common analytical approaches, such as thematic analysis, framework, constant comparison, content analysis, conversational analysis, discourse analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) and narrative analysis. Although IC was not originally developed to be a stand-alone method of analysing qualitative data, it seems important to consider whether or not it can actually be used in isolation. Reviewers of IC papers submitted for publication have suggested that the technique can be deployed independently and the published examples described in this article have confirmed that it is appropriate to use IC as a method in its own right [23, 24, 27, 32, 33, 35, 36]. Despite this, some clarification on how IC can be used to support other analytical approaches is required and, for this, it is helpful to consider the position of IC in relation to wider philosophical and methodological issues, specifically, how phenomena should be understood and addressed (‘research paradigm’), the nature of reality (‘ontology’) and the nature of knowledge (‘epistemology’) [48, 49].

Researchers hold diverse opinions on the extent to which there is ‘a reality’ that can be ‘measured’ (a ‘positivist’ paradigm) or ‘multiple realities’ that need to be ‘interpreted’ (a ‘constructivist’ paradigm) [49]. Although qualitative researchers tend toward more interpretivist and constructivist approaches, this is often a matter of degree and debate [50, 51]. Some qualitative researchers are content to identify themes and patterns in their data and to present these as ‘uncomplicated’ and ‘factual’. In contrast, others discuss their findings in a more circumspect way, emphasizing how these are co-constructed by researchers and participants in particular contexts and are therefore always ‘contingent’. Relatedly, some qualitative researchers focus their analyses on the content of participants' accounts, whereas others seek to uncover the latent meanings in their statements. IC is based on a pragmatic paradigm, meaning that it prioritises ‘what works’ and assumes that researchers will use the philosophical and methodological approaches best suited for the particular phenomenon being investigated [52, 53]. This is now illustrated by briefly revisiting some key IC stages.

During transcription, researchers using IC are encouraged to add both descriptive and reflective fieldnotes to their data, so enabling them to combine simple accounts of what happened during data generation with more subjective interpretations and understandings of how data are co-constructed with participants. During coding, both deductive and inductive codes are created, and these can be either descriptive (‘semantic’) or reflective (‘latent’) [5]. Additionally, as noted in the 2016 IC paper, researchers can code by a wide range of concrete and more abstract phenomena, including events or stories (for narrative analysis), feelings or experiences (for IPA), verbal interactions (for conversation analysis) or textual strategies (for discourse analysis). During the descriptive analytical stage, bullet points summarising data content can be supplemented with bullet points capturing the researcher's personal reflections, as long as these are easily distinguishable from each other (e.g. by using different text colours or fonts). Alternatively, a researcher can defer most of their meaning-making and critical reflection until the final interpretive stage. Having these kinds of options throughout the IC process enables researchers to weight their analyses toward their personal ontological and epistemological position, research paradigm and methodological approach.

Conclusion

Despite the long tradition of qualitative research within addiction science [54, 55], it has been argued that qualitative methods have been underused because of rigid addiction journal practices, the use of reviewers without appropriate qualitative expertise and the lack of credibility afforded to interpretive approaches to knowledge [55, 56]. Notwithstanding the emergence of checklists and guidelines for writing up qualitative research (e.g. CASP [57], COREQ [58], RATS [59]), qualitative researchers can compound their own marginalisation by failing to provide adequate accounts of how exactly they managed and analysed their data. This can hinder the ability of novice qualitative researchers to learn from the work of others and potentially undermines the credibility of qualitative science in the eyes of readers, editors and reviewers [1]. The value of IC is that it offers qualitative researchers a set of procedures to guide them through analysis to publication, leaving a clear audit trail [3]. Furthermore, using the stages of IC as suggested should ensure that qualitative analyses generate a better understanding of the phenomena being studied; study findings contribute to and enhance the existing literature; the audience for any qualitative output is broad and international; and any practical implications or study recommendations are relevant to other contexts and settings.

Declaration of interests

J.N. receives honoraria and some expenses from Addiction journal in her role as Commissioning Editor and Senior Qualitative Editor. In the last 3 years, she has received, through her University, research funding from Mundipharma Research Ltd and Camurus AB.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Robert West for challenging me to write the first IC article, Professor Susan Michie for challenging me to write this follow up, and the reviewers for providing constructive feedback. Thanks are also owed to all of my co-authors, students and workshop participants, who have helped develop my thinking over the years, and to everyone who has participated in interviews and focus groups, without whom qualitative research would not be possible. Joanne Neale is part-funded by the NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.