Peer-induced cocaine seeking in rats: Comparison to nonsocial stimuli and role of paraventricular hypothalamic oxytocin neurons

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine if social vs nonsocial cues (peer vs light/tone) can serve as discriminative stimuli to reinstate cocaine seeking. In addition, to assess a potential mechanism, an oxytocin (OT) promoter-linked hM3Dq DREADD was infused into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to determine whether peer-induced cocaine seeking is decreased by activation of OT neurons. Male rats underwent twice-daily self-administration sessions, once with cocaine in the presence of one peer (S+) and once with saline in the presence of a different peer (S−). Another experiment used similar procedures, except the discriminative stimuli were nonsocial (constant vs flashing light/tone), with one stimulus paired with cocaine (S+) and the other paired with saline (S−). A third experiment injected male and female rats with OTp-hM3Dq DREADD or control virus into PVN and tested them for peer-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking following clozapine (0.1 mg/kg). Although acquisition of cocaine self-administration was similar in rats trained with either peer or light/tone discriminative stimuli, the latency to first response was reduced by the peer S+, but not by the light/tone S+. In addition, the effect of the conditioned stimulus was overshadowed by the peer S+ but not by the light/tone S+. Clozapine blocked the effect of the peer S+ in rats receiving the OTp-hM3Dq DREADD virus, but not in rats receiving the control virus. These results demonstrate that a social peer can serve as potent trigger for drug seeking and that OT in PVN modulates peer-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking.

1 INTRODUCTION

The social environment affects vulnerability to drug addiction.1-5 In humans, association with drug-using peers is a strong predictor of continued drug use6 and relapse,7 whereas maintaining a strong social support network with non-using peers may be protective.8 In preclinical models of relapse, however, social factors are rarely considered. Instead, preclinical models traditionally emphasise inanimate discrete stimuli (e.g. cue light) or interoceptive stimuli (e.g. stress and drug prime) as triggers for the reinstatement of drug seeking.9 Although two recent studies have demonstrated that social peers can serve as triggers for reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats,10, 11 it is unclear if peer-induced reinstatement differs in intensity or mechanism from reinstatement induced by nonsocial stimuli. In addition, it is unclear if oxytocin (OT) systems, which are known to be involved in social reward and recognition,12-14 play a role in peer-induced reinstatement.

OT reduces self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine and methamphetamine seeking,15-17 as well as reducing neuronal activity in nucleus accumbens [NAc18, 19]. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus may be involved, as OT neurons in this region project directly to NAc.20, 21 However, because these previous studies used nonsocial stimuli (cue light or drug prime) to induce drug seeking, it remains to be determined if OT neurons in PVN play a role in peer-induced reinstatement.

Here, we build on our previous model of peer-induced reinstatement using a social peer as a contextual discriminative stimulus.11 Although we use the term “reinstatement” for consistency with previous work using contextual discriminative stimuli to elicit drug seeking,10, 11, 22 the phenomenon could also be called “contextual renewal”, as has been shown with food seeking.23, 24 Two experiments (Experiments 1A and 1B) were conducted using a dual-compartment apparatus. In Experiment 1A, rats received alternating self-administration sessions (cocaine vs saline) with one peer present throughout each cocaine session (peer S+) and a different peer present throughout each saline session (peer S−). In contrast to our previous report,11 however, the discrete cue light conditioned stimulus (CS) that was paired with each cocaine and saline infusion during training was also assessed to ascertain the relative role of the peer S+ and cue light CS in controlling reinstatement of responding. In Experiment 1B, similar procedures were used with nonsocial discriminative stimuli (light/tone) in the adjacent chamber. In a final experiment (Experiment 2), we used a chemogenetic approach to test the effect of activation of OT neurons in PVN on peer-induced reinstatement. A viral construct that was linked to the OT promoter and produced copies of the excitatory hM3Dq receptor25 was paired with clozapine26, 27 to activate OT neurons in PVN during reinstatement.

2 METHODS

2.1 Subjects

Fifty male and 20 female Sprague–Dawley rats (approximately 60 days of age) were obtained from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN). The rats were housed individually in a temperature-controlled colony room on a 12:12 h light schedule (lights on at 0800 h), and experimentation occurred during the light phase. The rats had ad libitum access to water and food (Teklad Global 18% protein rodent diet, Inotiv Co, West Lafayette, IN, USA) in the home cage with coarse Sani-Chip bedding (PJ Murphy Forest Products, Montville, NJ, USA), except as noted. All procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky and conformed to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Edition). A total of 10 rats failed to complete the study due to catheter failure and 2 rats were removed from Experiment 2 due to lack of viral expression.

2.2 Apparatus

Pretraining with food reinforcement occurred in a single operant conditioning chamber (28 × 24 × 21 cm; ENV-008CT; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) containing two retractable levers flanking a central food tray connected to a pellet dispenser. A 28-V white cue light was located above each lever, and a white house light was mounted over the centre of the opposite wall.

Self-administration sessions occurred in a custom-built apparatus consisting of two adjoined operant chambers; one chamber was used for self-administration training (self-administration chamber), and the adjacent chamber was used to present the social and nonsocial discriminative stimuli. A wire screen partition (1.27 cm, 19 gauge) was used to separate the chambers, which were like those used in food pretraining, but with no food tray. Each chamber contained two retractable levers, with a 28-V cue light located 6 cm above each lever, placed on either side of one wall. On the top of the opposite wall was a white house light above a speaker fed by a tone generator. In the adjacent chamber, the levers were retracted, and this chamber was used to present either a social peer (Experiments 1A and 2) or a light/tone compound (Experiment 1B). Each apparatus was located within a sound-attenuating cabinet.

2.3 Food pretraining

In order to facilitate acquisition of cocaine self-administration in the dual-compartment apparatus with a social peer that could potentially distract from lever pressing, the rats were first pretrained alone to press a lever for food reinforcement in the single compartment apparatus that was distinct from the dual-compartment apparatus. Prior to jugular catheter surgery, the rats underwent 3–5 daily sessions of pretraining to press a lever for a food pellet under mild food deprivation (12–15 g/day). Pellet delivery occurred on a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule and was paired with a 20-s time out (TO) signalled by illumination of the cue light above the active lever; active lever responses during this period had no consequence. The rats were given access to ad libitum food following the final session, and surgery occurred the next day.

2.4 Surgery

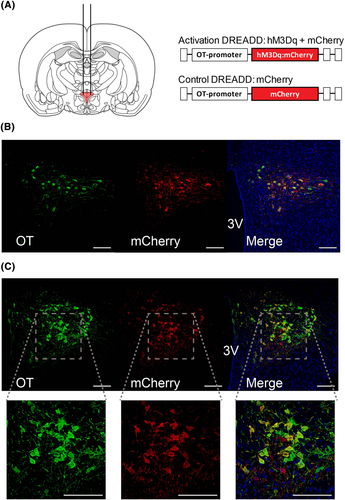

Self-administration rats were anaesthetised with a ketamine + xylazine mixture (males also received acepromazine) and received a chronically indwelling jugular catheter that exited via a dental acrylic head mount. While under anaesthesia, following implantation of the jugular catheter, the rats in Experiment 2 received craniotomies for bilateral infusions (280 nL per side) of the OT cell type specific DREADD (rAAV1/2 OTp-hM3Dq:mCherry) or control (rAAV1/2 OTp-mCherry) virus into the PVN [AP −1.8, ML ± 0.3, DV −8.028]. The viruses were cloned and packaged as described previously,25 at concentrations of ~ 1 × 1011 genomic copies per millimetre. The specificity and efficacy of rAAV1/2 OTp-hM3Dq:mCherry to infect and activate the majority of PVN OT neurons after i.p. injection of clozapine N-oxide (CNO) to rats has been previously confirmed25 and was also validated in our laboratory using cFos activation by 0.1 mg/kg clozapine (see supporting information S1). Viruses were infused over 2–3 min using a 1 μL Hamilton Neuros Syringe (Model 7001, #65458–01 with custom 45° bevel); the syringe tip was left in place for an additional 2 min after infusion. Following completion of each infusion, the craniotomies were patched with bone wax and a headcap was made using dental acrylic, completing the jugular catheter surgery.

2.5 Experiments 1A and 1B

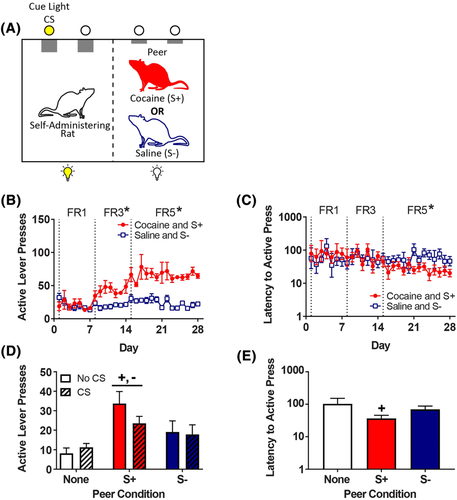

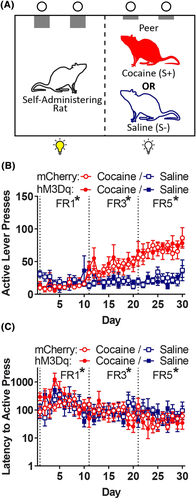

2.5.1 Experiment 1A: Social reinstatement

For discrimination training, the rats underwent twice-daily discrimination training sessions in the self-administration chamber (Figure 1A, left chamber) during the light cycle, with a minimum of 2 h intervening between each daily session. One of two peers (same sex and age as self-administering rat) was placed in the adjacent chamber (Figure 1A, right chamber) immediately before the self-administering rat entered the self-administration chamber. On each day of discrimination training, one of the sessions (counterbalanced) was designated as a cocaine self-administration session (1.0 mg/kg/infusion) with one peer (S+), whereas the other was a saline self-administration session with the other peer (S−). Assignment of the S+ and S− was random for peers. The programme that controlled each session was started immediately after the self-administering rat was hooked to the infusion tether and the doors of the sound-attenuation cabinet were closed.

The onset of each 60-min session was signalled by illumination of the house light and extension of both the active and inactive levers in the self-administration chamber. The self-administering rat could earn infusions according to the FR schedule, which increased from FR1 to a terminal FR5. Each infusion (0.1 mL delivered over 5.9 s) was paired with the onset of a 20-s TO, signalled by illumination of the cue light CS above the active lever. Responses during the TO had no programmed consequence. Only rats trained to self-administer cocaine (not the peers) had access to levers.

Following 28 days of self-administration (56 sessions), the rats underwent 12 twice-daily 60-min extinction sessions in which the peer discriminative stimuli and CS were omitted, followed by a series of 6 reinstatement tests; no infusions occurred during extinction or reinstatement, although reinstatement tests with the cue light CS present included the sound of pump activation. During each test, the rats were exposed to a combination of the peer discriminative stimuli (S+, S−, or none) and the cue light CS (present or absent), with order determined via Latin square design. Each reinstatement test was followed by four extinction sessions, with one half of the tests occurring in the first session of the day and one half in the second session of the day. Only rats trained to self-administer cocaine (not the peers) received extinction and reinstatement tests.

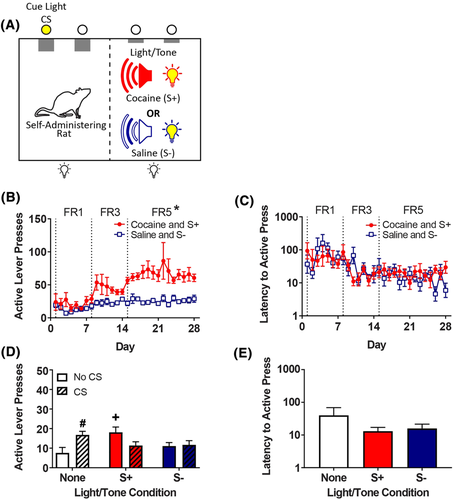

2.5.2 Experiment 1B: Nonsocial reinstatement

The rats in this experiment were trained to self-administer cocaine in the dual-compartment chamber similar to the rats described in Experiment 1A, except that a light/tone discriminative stimulus was used rather than a peer discriminative stimulus. For acquisition, the rats were placed alone in the self-administration chamber (Figure 2A, left chamber), and throughout the session the house light and tone generator in the adjacent chamber (Figure 2A, right chamber) were activated either constantly or in a flashing pattern (0.5 s on, 0.5 s off). Assignment of the S+ and S− was counterbalanced for light/tone pattern. In addition, the beginning of the session was signalled by extension of both the active and inactive levers in the self-administration chamber, along with the discriminative stimulus onset in the adjacent chamber.

Following self-administration training, the rats underwent extinction training as described in Experiment 1A and then received six reinstatement tests in which the rats were exposed to a combination of the light/tone discriminative stimuli (S+, S− or none) and the cue light CS (present or absent).

2.6 Experiment 2

This experiment determined the role of PVN OT neurons in peer-induced reinstatement in male and female rats.

2.6.1 Pretraining and self-administration training

Training was conducted as described in Experiment 1A, with one peer placed in the adjacent chamber (Figure 4A) before each session, except that the signalled TO (CS) was omitted to focus exclusively on the role of social discriminative stimuli. In addition, the FR requirement was incremented more slowly to the terminal FR5 because acquisition of self-administration was slower in this experiment, likely because of omission of the cue light CS.

2.6.2 Extinction and reinstatement

Following 10 once-daily extinction sessions in which the discriminative stimuli and infusions were omitted, the rats receiving the control or activation virus underwent 6 reinstatement tests, with tests in the presence of each peer condition (S+, S− or none) paired with drug (0.1 mg/kg clozapine or vehicle, i.p., 15 min prior to session); test order was determined by a Latin square design and tests were separated by 3 days of extinction training. Clozapine and vehicle were prepared as described previously.29 Clozapine was chosen over CNO because CNO is metabolised to clozapine in brain.26, 30 The clozapine dose selected has been shown to not alter locomotor activity on its own in other DREADD studies,26, 27 and this finding was also confirmed in our laboratory (see supporting information S2). Only rats trained to self-administer cocaine (not the peers) received extinction and reinstatement tests.

2.6.3 Perfusion and histology

The rats were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde on the day after completing their final reinstatement test in Experiment 2. Tissue was post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and then transferred to 30% sucrose. After the brains had sunk in the sucrose, they were sliced at 40 μm on a cryostat and stored in cryoprotectant at −20 °C. Next, the tissue was prepared by immunohistochemistry to verify infection. Briefly, four to eight slices from across the PVN were first washed in phosphate buffered saline and 0.1% triton (PBS+) and then pre-blocked with 3% donkey serum in PBS+ for 60 min at room temperature. Next, they were incubated with 1:1000 rabbit anti-dsRed (Living Colors DsRed Polyclonal Antibody #632496, TaKaRa) and 1:1000 mouse anti-OT antibody PS3831 in 3% donkey serum and PBS+ overnight at 4 °C. The tissue was washed in PBS+ before incubation with the secondary antibodies, 1:250 Donkey Anti-Rabbit (Alexa 488) and 1:250 Donkey Anti-Mouse (Alexa 647) in 3% donkey serum and PBS+ for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the tissue underwent a final series of PBS+ washes and then 30 s of direct staining with 1:1000 DAPI. The tissue was mounted on slides with Mowiol and then stored in at 4 °C until ready for imaging.

Images were taken at 10X and 20X using a Nikon Ti confocal microscope and pseudo-coloured so that mCherry appeared red and OT appeared green. Each set of tissue received the same set of adjustments to look-up-tables (LUTs) and threshold to enable visualisation of co-labelling.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using mixed model and mixed linear regression analysis in SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) proc GLIMMIX. In Experiments 1A and 1B, acquisition was analysed by examining the within-subject factors of drug and FR requirement, along with the continuous factor of session within FR requirement, for active lever presses and latency to the first active lever press. Extinction was analysed by examining active lever presses as a function of the within-subjects factor of session (continuous variable). The same analyses were conducted in Experiment 2, with virus and sex added as between-subject factors. In Experiments 1A and 1B, reinstatement was assessed as a function of the within-subject factors of the discriminative stimuli (peer or light/tone) and cue light CS. In Experiment 2, reinstatement was assessed as a function of the within-subject factors of peer discriminative stimuli and drug pre-treatment, and the between-subject factors of virus and sex. To determine if there was an effect of sex on peer-induced reinstatement, a secondary analysis was conducted using only the vehicle test data, collapsed across the virus condition. Post hoc tests of simple effect comparisons were conducted for significant main effects and interactions, with results adjusted using the Tukey–Kramer method when more than one comparison was made. A priori tests were also included in the analysis of the reinstatement data from Experiment 2. We examined the effects of the peer on reinstatement within each level of virus, the effects of virus within each combination of clozapine and peer, and the effect of drug within each combination of virus and peer. Time (e.g. first or second session of the day) was included as a covariate where appropriate. The overall results for each statistical analysis conducted are provided (see supporting information S3).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Experiment 1A: Peer-induced reinstatement

During acquisition of self-administration, mixed linear regression analysis of active lever presses (Figure 1B) revealed a drug × FR interaction (F2,18 = 22.0, p < 0.001), with a greater number of lever presses for cocaine than saline on the FR3 and FR5 components. Mixed linear regression analysis of the latency to first active lever press revealed a drug × FR interaction (F2,18 = 6.22, p = 0.009; Figure 1C), with post hoc analyses revealing a shorter response latency for cocaine compared to saline only on the terminal FR5 (t18 = 5.78, p < 0.001). At the end of extinction, the mean number of active responses decreased to 3.4 (results not shown).

Reinstatement of responding was affected by the peer discriminative stimulus (F2,18 = 13.0, p < 0.001; Figure 1D) but not by the cue light CS. Regardless of the CS condition, Tukey's post-hoc analysis of the peer effect on reinstatement revealed that the peer S+ increased responding compared to both the no peer (t18 = 5.09, p < 0.001) and the peer S− (t18 = 3.06, p = 0.017) conditions; the difference between peer S− and no peer conditions was not significant (t18 = 2.22, p = 0.095). Analysis of the response latency during reinstatement also revealed a main effect of the peer discriminative stimulus (F2,18 = 4.24, p = 0.031; Figure 1E), with Tukey's post hoc analysis revealing a shorter latency only when the peer S+ was present (t18 = 2.84, p = 0.028), relative to when no peer was present.

3.2 Experiment 1B: Light/tone-induced reinstatement

During acquisition, mixed linear regression analysis of active lever presses (Figure 2B) revealed a drug × FR interaction (F2,16 = 8.75, p = 0.003), with Tukey's post hoc test revealing a greater number of lever presses for cocaine than saline on the terminal FR5 (t16 = 13.6, p < 0.001). Mixed linear regression analysis of the latency to first active lever press (Figure 2C) revealed that the latency to the first active lever press was affected by the FR (F2,16 = 8.33, p = 0.003) and session (F1,483 = 6.29, p = 0.012), but the drug × FR × session interaction failed to reach significance (p = 0.084). At the end of extinction, the mean number of active responses decreased to 5.4 (results not shown).

For nonsocial reinstatement (Figure 2D), analysis of active lever pressing revealed a significant discriminative stimulus × CS interaction (F2,16 = 5.97, p = 0.012). Tukey's post-hoc analysis revealed that there was reinstatement, relative to extinction, when rats were exposed to the light/tone S+ (t16 = 3.35, p = 0.011) or the cue light CS (t16 = 2.91, p = 0.010). The difference between responding to the light/tone S+ and light/tone S−, when CS was absent, did not reach significance in the Tukey test (t16 = 2.20, p = 0.10). Analysis of the response latency to first active lever press during reinstatement (Figure 2E) revealed no significant difference among the discriminative stimulus conditions (p = 0.073).

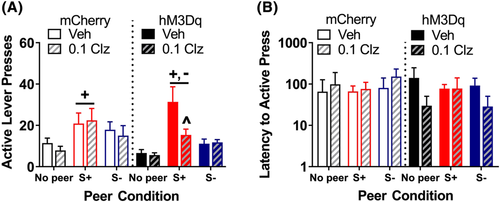

3.3 Experiment 2: Peer-induced reinstatement following activation of OT neurons in PVN

Immunohistochemical verification of viral infection (Figure 3) revealed that 9/9 rats receiving the mCherry virus and 8/10 rats receiving the mCherry:hM3Dq virus had detectable levels of mCherry expression in OT neurons (Figure 3B,C). The rate of infection of OT neurons by the control mCherry virus was 85%, and by the active mCherry:hM3Dq virus was 58%.

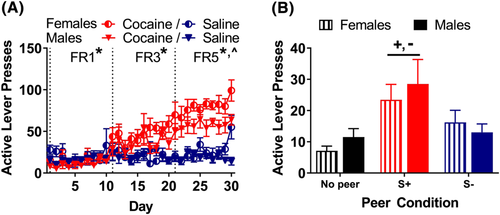

During acquisition, mixed linear regression analysis of active lever presses during acquisition (Figure 4B, collapsed across sex; and Figure 6A, separated by sex) revealed a drug × FR interaction (F2,30 = 47.8, p < 0.001) and a drug × session interaction (F1,945 = 4.05, p = 0.044). Post hoc analysis of the drug × FR interaction revealed that there was a significant effect of drug at each FR, with active lever press responding for cocaine versus saline, lower at FR1 (t30 = −2.72, p = 0.011) and higher at FR3 (t30 = 10.1, p < 0.001) and FR5 (t30 = 22.8, p < 0.001). There was also a FR × session × sex interaction (F2,945 = 3.85, p = 0.022), with females responding more than males across sessions as the FR was incremented (Figure 6A). However, the drug × sex interaction did not reach significance (p = 0.071). Analysis of latency to the first active lever press (Figure 4C, collapsed across sex) revealed a drug × FR interaction (F2,30 = 5.61, p = 0.009) and a drug × session interaction (F1,945 = 5.78, p = 0.016); the three-way drug × FR × session interaction failed to reach significance (p = 0.059). Tukey's post hoc analysis revealed that the latency was longer for cocaine at FR1 (t30 = −2.54, p = 0.017) but shorter for cocaine at FR3 (t30 = 2.66, p = 0.012) and FR5 (t30 = 3.63, p = 0.001); there was no main effect or interaction involving the sex or virus factors. Following extinction, the mean number of responses decreased to 12.1 (results not shown), with no effect of virus or sex.

For peer-induced reinstatement (Figure 5A, collapsed across sex), analysis of active presses revealed a main effect of peer (F2,26 = 17.9, p < 0.001), but the peer × drug × virus interaction failed to reach significance (p = 0.055). Tukey's post hoc analysis revealed that, collapsed across the virus condition, the peer S+ elicited greater responding relative to the peer S− (t26 = 3.55, p = 0.004) or no peer (t26 = 5.95, p < 0.001) conditions; there was also a trend toward a difference between the peer S− and no peer conditions (t26 = 2.4, p = 0.059). Planned comparisons of the effect of the peer within each virus group were used to confirm that the peer S+ elicited reinstatement when compared to the no peer condition for rats in both viral groups (activation: t26 = 4.8, p < 0.001; control: t26 = 3.58, p = 0.004). Although the control virus group appeared to have a weaker response to the peer S+ compared to the active virus group, planned comparison of the effect of the virus within the levels of peer and clozapine treatment revealed that this did not reach significance (t26 = 1.88, p = 0.072). When the effect of clozapine was examined separately through planned comparisons with each level of virus and peer, we found that clozapine reduced responding elicited by the peer S+ among rats receiving the activation virus (t26 = 3.15, p = 0.004) but not among rats receiving the control virus (p = 0.63). There was no effect of clozapine on responding in the presence of the peer S− or no peer conditions, regardless of virus condition (ps > 0.35). There was no effect of peer on latency to the first active lever press during reinstatement (Figure 5B, collapsed across sex) and the drug × virus interaction failed to reach significance (p = 0.091). Sex had no effect on reinstatement responding or latency (results not shown).

An exploratory analysis of potential sex differences in peer-induced reinstatement was conducted on data collapsed across the virus conditions in the absence of clozapine (Figure 6B, separated by sex). Analysis of the effects of sex and peer on responding during the vehicle tests revealed only a main effect of peer (F2,30 = 8.58, p = 0.001), with Tukey's post hoc analysis confirming that the peer S+ elicited more responding than the no peer (t30 = 4.06, p < 0.001) or peer S− (t30 = 2.76, p = 0.025) conditions; the difference between the peer S− and no peer conditions was not significant.

4 DISCUSSION

In two separate experiments (Experiments 1A and 1B), social or nonsocial cues were used as contextual discriminative stimuli for eliciting cocaine seeking. The ability of either a peer or light/tone discriminative stimulus to elicit cocaine seeking was compared when each was tested alone, as well as when each was tested in combination with a discrete cue light CS. Consistent with our previous study,11 we found that the presence of the peer S+ increased drug seeking relative to the peer S−. Using similar procedures, we found that the light/tone S+ also increased drug seeking. However, at least two differences in the results obtained across experiments suggest that peer-induced reinstatement differs from light/tone-induced reinstatement. First, the latency to earn the first infusion across acquisition was shorter on cocaine sessions than saline sessions using peer discriminative stimuli, but not using light/tone discriminative stimuli (cf. Figure 1C vs 2C), suggesting anticipatory responding occurred only with social stimuli. Second, in contrast to reinstatement elicited by the cue light CS in the light/tone experiment, the CS used in the peer experiment failed to elicit cocaine seeking (cf. striped white CS bar vs solid white No CS bars in None Condition in Figure 1D vs 2D). This latter finding suggests that when a nonsocial CS (cue light) is used within a nonsocial context (light/tone), associative strength is distributed across both the CS and contextual elements. In contrast, when the same nonsocial CS is used within a social context, associative strength appears to accrue to the peer only, thus overshadowing the association between the CS and cocaine.24, 32 Together, these results suggest a fundamental difference in how social and nonsocial stimuli control drug seeking.

The relatively weak reinstatement elicited by the light/tone discriminative stimulus contrasts with previous work by others showing contextual control of cocaine seeking with nonsocial discriminative stimuli presented in a single-chamber operant conditioning apparatus.33-35 A number of procedural differences prevent a direct comparison between those studies and the current one, but one important difference is that the previous studies used a white noise to signal cocaine availability (S+) and a house light to signal saline availability (S−). That approach, while producing more robust reinstatement than that observed here, relied on the S+ and S− activating different sensory modalities (auditory vs visual). In the current study, however, the light/tone discriminative stimuli affected the same sensory modalities but differed in pattern (i.e. constant or flashing) and were localised to an adjacent chamber, as well as being counterbalanced for S+ or S− conditions. This was done to ensure that the light/tone experiment more closely modelled the peer experiment, where the peers in the adjacent chamber activated the same sensory systems in the self-administering rat, differing only in individual identity. Although olfactory cues are not necessary for a discriminative stimulus to trigger reinstatement of cocaine seeking,33 it is possible the addition of olfactory cues in the peer context added an extra layer of information that enhanced the saliency of the social discriminative stimuli. Greater salience of a peer over light/tone context may also explain why the social discriminative stimulus, but not the nonsocial discriminative stimulus, produced anticipatory responding during discrimination as reflected in the latency to first active lever press.

Another key finding from the current study is that chemogenetic activation of OT neurons in PVN reduced peer-induced reinstatement. Although OT has multiple functions, it plays an important role in social reward12, 36 and has been identified as a potential treatment to reduce drug value and drug seeking.17, 19, 37-39 Social reward requires the recruitment of pre-synaptic OT receptors within NAc,40, 41 and NAc OT receptors mediate social investigation.42-44 Thus, since OT enhances the rewarding effect of social interaction,12 activation of PVN OT neurons in the current study may have increased the incentive salience of the peer S+ on the reinstatement test, thus eliciting approach to the peer and away from the active lever. However, the interpretation that OT activation simply enhances approach to a peer is mitigated somewhat by the finding that OT activation did not produce a similar decrease in lever pressing in the presence of the peer S−. As an alternative explanation, since OT decreases cocaine self-administration and decreases reinstatement to a cue light CS associated with cocaine,15, 16, 18, 45 it may be that OT simply blocked recall of the conditioned reinforcing effect of cocaine that was attributed to the peer S+, thus reducing the “craving” response underlying reinstatement. Further, we cannot rule out another alternative possibility that DREADD activation was aversive on its own, thus producing an anhedonia-related decrease in lever pressing.

In addition to social reward, OT is also involved in social recognition.14 While social reward depends on PVN projections to NAc, social recognition is thought to be mediated primarily by OT via projections from the PVN to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST).21 Supporting this, OT release is increased during a social recognition task36 and increasing OT, particularly within the BNST, enhances social recognition.12, 36 However, it is unlikely that the decrease in peer-induced reinstatement by OT activation in the current study was due to altered recognition of the social peers. If activation of OT neurons in the PVN enhanced peer recognition, one would predict a greater difference, not a reduced difference, when comparing responding in the presence of either the peer S+ or S−. Since this was not the case, we favour the explanation that OT activation altered the incentive value attributed to the peer S+.

In an exploratory analysis with low power, we found no reliable sex difference on peer-induced reinstatement despite evidence showing that there are sex-dependent effects of OT on social reward and recognition. For example, one study found that only males exhibited a positive relationship between BNST OT release and social recognition,36 with sex differences in OT systems being region specific.13, 42 There are also sex differences in social reward,46 which led us to examine the effects of sex on peer-induced reinstatement by combining data from both the control and active virus conditions, using only tests with the vehicle injection. Despite being an exploratory analysis due to low power, the failure to observe a reliable sex difference in peer-induced reinstatement is consistent with the lack of sex difference generally found with cue-induced reinstatement37, 45, 47, 48; however, there are exceptions [e.g.17]. Another study found no sex difference in context-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking.49 In addition, while one recent study found greater context-induced methamphetamine reinstatement in males than in females, it was only evident when expressed as a percentage of extinction behaviour.50 Further work is needed to determine if there are sex-dependent differences in the OT-induced decrease in peer-induced reinstatement observed here, especially since some studies suggest females may be more sensitive to the effects of OT in nonsocial models of drug-related behaviour.16, 17, 45

A few caveats should be noted in the current work. First, it is possible that the brief period of food-reinforced lever pressing prior to cocaine self-administration may have contributed to the reinstatement results. We minimized this potential by conducting food pretraining in a context distinctly different from the dual-compartment apparatus used to establish cocaine self-administration with a peer. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out some long-lasting carry over effect of the food pretraining. Second, since we did not determine if chemogenetic activity of OT in PVN altered light/tone-induced reinstatement, we cannot conclude that OT is specific to a social context. Third, since rats were housed individually in the home cage, it is possible that the lack of normal peer interaction enhanced the saliency of the peer S+ relative to the light/tone S+. It will be interesting to determine in future work if single- vs group-housed rats differ in peer-induced reinstatement.

In conclusion, while both social and nonsocial cues elicited cocaine seeking, only social cues reduced latency to the first response during acquisition and overshadowed the effect of the CS during reinstatement testing. Social peer-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking was decreased by clozapine in rats receiving OTp-hM3Dq DREADD virus into the PVN. These results demonstrate that a social peer can serve as potent trigger for drug seeking and that OT in PVN modulates peer-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking.

STATEMENT ON AUTHORSHIP

LRH, JSB and MTB were responsible for the study concept and design. LRH, BAH and SGM contributed to the acquisition of behavioural and immunohistochemical data. VG was responsible for supplying the virus and providing advice on its use. KES provided critical direction on conducting the immunohistochemical assays and imaging with confocal microscopy. LRH conducted the data analysis, and LRH and MTB were involved in interpretation of findings. LRH drafted the manuscript, and MTB provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Emily Denehy and Diego Benusiglio for their expert technical assistance. In addition, they thank Dr. Yavin Shaham for his helpful feedback during the early stages of these experiments. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants T32 DA16176 (for LRH) and R21 DA041755 (to MTB) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants GR 3619/13-1, GR 3619/15-1, GR 3619/16-1, and the SFB Consortium 1158-2 (to VG).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest to report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.