Modulation of brain structure by catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism in chronic cannabis users

Abstract

Neuroimaging studies have shown that chronic consumption of cannabis may result in alterations in brain morphology. Recent work focusing on the relationship between brain structure and the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphism suggests that functional COMT variants may affect brain volume in healthy individuals and in schizophrenia patients. We measured the influence of COMT genotype on the volume of four key regions: the prefrontal cortex, neostriatum (caudate-putamen), anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus-amygdala complex, in chronic early-onset cannabis users and healthy control subjects. We selected 29 chronic cannabis users who began using cannabis before 16 years of age and matched them to 28 healthy volunteers in terms of age, educational level and IQ. Participants were male, Caucasians aged between 18 and 30 years. All were assessed by a structured psychiatric interview (PRISM) to exclude any lifetime Axis-I disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition. COMT genotyping was performed and structural magnetic resonance imaging data was analyzed by voxel-based morphometry. The results showed that the COMT polymorphism influenced the volume of the bilateral ventral caudate nucleus in both groups, but in an opposite direction: more copies of val allele led to lesser volume in chronic cannabis users and more volume in controls. The opposite pattern was found in left amygdala. There were no effects of COMT genotype on volumes of the whole brain or the other selected regions. Our findings support recent reports of neuroanatomical changes associated with cannabis use and, for the first time, reveal that these changes may be influenced by the COMT genotype.

Introduction

Cannabis is currently the most consumed illicit drug worldwide (Watson, Benson & Joy 2000). Previous structural neuroimaging studies have not reported differences between cannabis users compared with control groups as to global brain measures, and studies based on specific region of interest have reported inconsistent results (Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Martin-Santos et al. 2010). One explanation for the discrepancies observed in human volumetric studies may be the heterogeneity across study samples in terms of duration and frequency of use, as well as quantity and type of cannabis smoked and demographic characteristics (Lorenzetti et al. 2010). Despite these conflicting results, there is evidence that earlier (before the age of 17) onset of cannabis use may be associated with greater detrimental effects on brain morphology compared with onset later on in life (Wilson et al. 2000). Additionally, long-term cannabis use may result in persistent alterations in brain function and morphology, particularly in those areas related with executive functioning, reward circuitry and memory, such as the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), basal ganglia (e.g. neostriatum) and medial temporal areas (e.g. hippocampus and amygdala) (Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Martin-Santos et al. 2010), where CB1 receptors are more concentrated (Burns et al. 2007). Severity of cannabis use has also been found to be associated with gray matter volume in the prefrontal cortex in a group of subjects at clinical risk for psychosis and healthy controls (Stone et al. 2012).

Genetic variation may also play an important role in determining brain morphology. Recent studies focused on the relationship between brain structure and the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism suggest that functional COMT variants could affect brain volume in schizophrenia patients (Ohnishi et al. 2006), subjects at risk for psychosis (McIntosh et al. 2007) and even in healthy individuals (Honea et al. 2009), although negative results have also been reported (Barnes et al. 2012). In addition, preliminary data of several genes modulating the adverse effects of cannabis on the brain, including COMT polymorphism, have also been reported in long-term chronic cannabis users (Solowij et al. 2012). The COMT gene displays a functional polymorphism at codon 158 causing a valine (val) to methionine (met) substitution (Val158Met, rs4680) resulting in three genotypes (val/val, val/met and met/met). Whereas the met/met variant shows a 40% lower enzymatic activity, which is associated with high levels of extrasynaptic dopamine, the val/val variant implies higher enzymatic activity, which results in low levels of extrasynaptic dopamine (Chen et al. 2004). COMT has an important role in clearing dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (Tunbridge, Harrison & Weinberger 2006), in subcortical regions such as basal ganglia and medial temporal lobe, as well as in the cerebellum and the spinal cord (Hong et al. 1998; Honea et al. 2009). Furthermore, epidemiological as well as experimental studies have shown that val-allele carriers may be more sensitive to the longer term effects of cannabis as well as the acute effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, particularly if there is prior evidence of psychosis liability (Henquet et al. 2006; Estrada et al. 2011). Nevertheless, to our knowledge, there are no previous studies published that have examined the influence of COMT polymorphism on brain morphology in subjects chronically exposed to cannabis.

The aim of the present study was therefore to explore the influence of COMT Val158Met functional polymorphism on four key regions: the prefrontal cortex, neostriatum (caudate-putamen), ACC and the hippocampus-amygdala complex, in a group of early-onset chronic cannabis users compared with non-using control subjects using voxel-based morphometry (VBM). VBM has been used successfully in prior research to identify changes in brain morphology related to common genetic polymorphisms, such as COMT (Honea et al. 2009) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Pezawas et al. 2004). We hypothesized that COMT Val158Met functional polymorphism would be associated with brain morphological deficits in early-onset chronic cannabis users relative to healthy controls, with dose-dependent associations between volume brain variations and val-allele dosage.

Methods

Subjects

Participants were primarily recruited via a web page and distribution of flyers and ads. To assess for study eligibility, a comprehensive telephone screening measures was performed (contact and sociodemographic data and a standardized drug use questionnaire). If considered eligible, subjects were required to undergo a detailed medical history check, routine laboratory tests, physical examination, urine and hair toxicology screens and a brief neurological examination. Drug use characteristic were systematically assessed using ad hoc questionnaire. The units used were as follows: number of cigarettes for tobacco use per day; standard units of alcohol per week and number of ‘joints’ for cannabis consumption per day and week.

Inclusion criteria required that participants were male, between 18 and 30 years of age, Caucasian, with IQ > 90 and fluent in Spanish. To be included in the cannabis-user group, the subject had to fulfill the following criteria: onset of cannabis use before the age of 16 years; cannabis use between 14 and 28 ‘joints’/week during at least the last 2 years and continued until entry into the study; no previous use of any other drug of abuse more than five lifetime except nicotine or alcohol; positive urine drug screen for cannabinoids but negative for opiates, cocaine, amphetamines and benzodiazepines on the day of the assessment, tested using immunometric assay kits. Control subjects had to fulfill the following criteria: no more than 15 lifetime experiences with cannabis (with none in the past month), no previous use of any other drug of abuse more than five lifetime except nicotine or alcohol. All controls had a negative urine drug screen for opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines and cannabinoids, tested using immunometric assay kits (Instant-View; ASD Inc, Poway, CA, USA). Hair testing was performed in all subjects to verify either repeated cannabis consumption (chronic cannabis users group) or non-consumption (control group).

Exclusion criteria included any lifetime Axis I disorder (substance use disorders and non-substance use disorders) according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association 2000) except for nicotine use disorder assessed by a structured psychiatric interview (PRISM) (Torrens et al. 2004); use of psychoactive medications; history of chronic medical illness or neurological conditions that might affect cognitive function; head trauma with loss of consciousness > 2 minutes; learning disability or mental retardation; left-handedness and non-correctable vision, color blindness or hearing impairments. Subjects also received the vocabulary subscale of WAIS-III, to provide an estimate of verbal intelligence (Wechsler 1997).

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject after they had received a complete description of the study and been given the chance to discuss any questions or issues. Upon completion of the study, all subjects received financial compensation for participation. The study was approved by the Ethical and Clinical Research Committee of our institution (CEIC-Parc de Salut Mar).

Genotyping methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood leukocytes of all the participants using Flexi Gene DNA kit (Qiagen Iberia, S.L., Spain) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The COMT Val158Met single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) allelic variants were determined using the 5′ exonuclease TaqMan assay with ABI 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Real-Time PCR) supplied by Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA. Primers and fluorescent probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems with TaqMan SNP Genotyping assays (assay ID C_2255335_10). Reaction conditions were those described in the ABI PRISM 7900HT user's guide. Endpoint fluorescent signals were detected on the ABI 7900, and the data were analyzed using Sequence Detector System software, version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems).

Structural image processing and analyses

Images were acquired with a 1.5-T Signa Excite system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) equipped with an eight-channel phased-array head coil. A high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was obtained for each subject using a three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient inversion-recovery prepared sequence with 130 contiguous slices (TR, 11.8 milliseconds; TE, 4.2 milliseconds; flip angle, 15°; field of view, 30 cm; 256 × 256 pixel matrix; slice thickness, 1.2 mm).

Imaging data were transferred and processed on a Microsoft Windows platform using a technical computing software program (MATLAB 7.8; The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA) and Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8; The Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK). Following inspection for image artifacts, image preprocessing was performed with the VBM toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/). Briefly, native-space magnetic resonance imaging were segmented and normalized to the SPM-T1 template using a high-dimensional DARTEL transformation. In addition, the Jacobian determinants derived from the spatial normalization were used to modulate image voxel values to restore volumetric information (affine and non-linear) (Good et al. 2001). Finally, images were smoothed with an 8 mm full width at half maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive results are presented as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and frequencies (absolute, relative) for categorical variables.

Global gray matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid volumes, as well as total intracranial volume (TIV), were obtained after data pre-processing and compared between groups with independent samples t-tests in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v.18; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Voxel-wise regional volume differences were studied with SPM tools. To study the effects on brain morphology of the interaction of COMT genotype and chronic cannabis use, we used a two-sample t-test design (chronic cannabis users versus controls) with age and global gray matter volume as nuisance covariates, and modeling the COMT genotype as a quantitative variable (number of met alleles: 0, 1, 2) in interaction with group. This approach allowed the assessment of between-group differences in the correlations of the number of met alleles with voxel-wise gray matter values, and we reported results from regions where such between-group differences were statistically significant (i.e. interactions). This analysis was initially restricted to four key regions: the prefrontal cortex, neostriatum (caudate and putamen), ACC and the hippocampus-amygdala complex) using an anatomical mask created with the Wake Forest University pickAtlas (Maldjian et al. 2003). Importantly, these masks were used to perform voxel-wise analyses within such regions, allowing a more precise anatomical localization of our findings. However, average volumes were also calculated for each region by adding up modulated voxel values included in the masks (i.e. adding up voxel values previously multiplied by the Jacobian determinants derived from the normalization step). The resulting values were transformed to milliliters and are presented in Table 3 in relation to TIV. In addition, a whole-brain analysis was also performed (see below).

To complement the above analyses, we also assessed for between-group differences (irrespective of genotype) in regional gray matter volumes using a two-sample t-test design with age and TIV as nuisance covariates. Finally, exploratory voxel-wise correlation analyses were also performed to test, within the cannabis user group, for significant associations between regional volumes and lifetime cannabis consumption (number of ‘joints’) by introducing this variable as a regressor of interest, as well as age and TIV as nuisance covariates.

Significance thresholds for global brain SPM analyses were set at P < 0.05, family-wise error corrected for multiple comparisons across the brain. When the analyses were restricted to a regional anatomical mask (i.e. to study the effects of COMT genotype/cannabis use interaction), the correction for multiple comparison was adjusted to the number of voxels within the mask (i.e. small volume correction). To account for the different number of voxels within each mask, and thus for the different significance threshold set for each region, these analyses were also performed at more lenient significance threshold of P < 0.001 uncorrected for multiple comparisons. In addition, to get a better notion of the anatomical extension of the findings, results were always displayed (i.e. in figures) at P < 0.001 (uncorrected). For SPSS analyses, the statistical threshold was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

A final sample of 57 subjects was included: 29 early-onset cannabis users and 28 drug-free control subjects. Main demographic and drug use characteristics are described in Table 1. No differences were found in demographic and drug use variables between both groups except for alcohol and tobacco use. None of them met lifetime criteria for abuse or dependence of alcohol. All participants were under the risk dose of 28 unit of alcohol per week. On average, cannabis users smoked no more than seven cigarettes per day (range = 0–20). Only three participants smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (two cases and one control subject).

| Cannabis users | Control | td.f.=57/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/n (SD/%) | Mean/n (SD/%) | |||

| Age | 20.8 (2.1) | 22.1 (3.0) | 1.87 | 0.065 |

| Males | 29 (100) | 28 (100) | — | — |

| Cannabis use | ||||

| Onset of use (age, years) | 14.9 (1.1) | 16.8 (2.0) | 2.96 | 0.001 |

| Total lifetime cannabis use (number of joints) | 5203 (4192) | 4.9 (6.1) | 6.68 | < 0.001 |

| Onset regular use (age, years) | 18.1 (2.1) | — | — | — |

| Duration of use (years) | 5.9 (2.4) | — | — | — |

| Current cannabis use (joints/day) | 2.5 (1.5) | — | — | — |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Age of onset of use | 15.0 (1.1) | 15.8 (1.5) | 2.35 | 0.023 |

| Duration of use | 5.7 (2.3) | 6.3 (3.1) | 0.87 | 0.389 |

| Alcohol units per week | 5.3 (3.8) | 3.1 (3.1) | 2.49 | 0.020 |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Current smokers | 27 (93.1) | 9 (32.1) | 21.8 | < 0.001 |

| Age of onset of use | 16.3 (1.5) | 16.3 (2.2) | 0.57 | 0.955 |

| Duration of use (years) | 4.5 (2.7) | 4.9 (3.3) | 0.34 | 0.737 |

| Cigarettes per day | 6.0 (5.0) | 2.4 (5.9) | 1.79 | 0.082 |

- d.f. = degrees of freedom; SD = standard deviation.

Genotype frequencies of the COMT gene are presented in Table 2. Genotype frequencies of the COMT gene were as follows: 11 subjects were homozygous for the met allele, 13 were val/val and 33 were val/met carriers. There was no evidence that these data were not in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

| Cannabis (n = 29) | Control (n = 28) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMT Val108/158 Met | 0.563 | ||

| Met/Met | 4 | 7 | |

| Val/Met | 18 | 15 | |

| Val/Val | 7 | 6 |

- COMT = catechol-O-methyltransferase; met = methionine; val = valine.

Global volume measurements and whole-brain between group differences

Global gray matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid volumes were related to TIV. Between-group comparisons detected no significant differences for any of these variables. Table 3 presents global tissue volumes normalized to TIV.

| Mean (SD) | td.f.=55 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray mattera | Cannabis | 49.29 (2.07) | 0.77 | 0.447 |

| Controls | 48.90 (1.84) | |||

| White matter | Cannabis | 35.32 (1.61) | −0.54 | 0.589 |

| Controls | 35.54 (1.49) | |||

| Cerebrospinal fluid | Cannabis | 15.39 (1.29) | −0.55 | 0.586 |

| Controls | 15.56 (1.11) | |||

| Intracranial volume | Cannabis | 1488 (137) ml | 1.06 | 0.296 |

| Controls | 1522 (112) ml | |||

| Prefrontal cortexb | Cannabis | 8.91 (0.57) | 0.32 | 0.747 |

| Controls | 8.86 (0.50) | |||

| Anterior cingulate cortex | Cannabis | 0.69 (0.06) | −1.22 | 0.229 |

| Controls | 0.71 (0.05) | |||

| Neostriatum | Cannabis | 0.73 (0.09) | 6.46 | < 0.001 |

| Controls | 0.60 (0.05) | |||

| Hippocampus-amygdala | Cannabis | 0.70 (0.04) | −0.36 | 0.717 |

| Controls | 0.71 (0.03) | |||

- aGlobal tissue volumes are presented normalized to TIV. bVolumes of the four regions of interest are presented normalized to TIV and collapsed across hemispheres. d.f. = degrees of freedom; ml = milliliters; SD = standard deviation.

Irrespective of genotype, chronic cannabis users showed a gray matter volume increase in the postcentral gyrus of the left hemisphere at a significance threshold of P < 0.001 uncorrected (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In a post hoc assessment, we observed that the volume of this region was not affected by the genotype or the interaction between group and genotype. Likewise, we did not observe any significant gray matter volume reductions in chronic cannabis users. Finally, we did not observe any significant between-group difference when this analysis was restricted to our four selected regions.

COMT genotype and chronic cannabis use between-group interactions

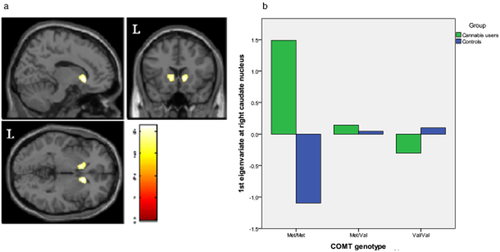

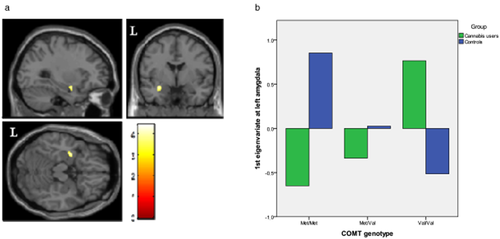

We found significant between-group differences in the genotype-gray matter volume correlations in two out of our four regions. Specifically, in chronic cannabis users, we found a negative correlation between bilateral ventral caudate nucleus volume and the number of val alleles, while the reverse association was observed in healthy controls: the more val alleles, the more ventral caudate gray matter volume (Fig. 1). In contrast, we observed that in chronic cannabis users a greater number of val alleles were associated with significant increase in left amygdala volume. The opposite was true for controls: the more val alleles, the smaller the gray matter volume in left amygdala (Fig. 2).

Regions of interaction between catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genotype and brain morphology superimposed on selected slices of a normalized brain (ROI analysis). (a) In the right and left ventral caudate nucleus, while gray matter volume was negatively correlated with the number of Val alleles in chronic cannabis users, the opposite pattern of correlation was observed in control subjects (right: peak at x, y, z = 12, 20, −2; t = 4.07; P(SVC-FWE corrected) = 0.034; left: peak at x, y, z = −11, 15, −0; t = 4.20; P(SVC-FWE corrected) = 0.023). (b) Relationship between gray matter volume in right ventral caudate and COMT genotype. Figure shows a reverse relationship between groups. Voxels with P < 0.001 (uncorrected) are displayed. Regional volumes were adjusted to age and total intracranial volume. Color bar represents t value. L indicates left hemisphere

Regions of interaction between catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genotype and brain morphology superimposed on selected slices of a normalized brain (ROI analyses). (a) In the amygdala of the left hemisphere, gray matter volumes were correlated with the number of Val alleles in chronic cannabis users, while the opposite pattern of correlation was observed in control subjects (peak at x, y, z = −30, −1, −18; t = 3.82; P(SVC-FWE corrected) = 0.046). (b) Differences in gray matter volume in left amygdala between Val and Met alleles. Figure shows a reverse relation between groups. Voxels with P < 0.001 (uncorrected) are displayed. Regional volumes were adjusted to age and total intracranial volume. Color bar represents t value. L indicates left hemisphere

Importantly, to account for the different number of voxels within each masked region, and thus for the different corrected significance thresholds set for each region, we repeated the interaction analyses at the whole-brain level. While the above findings were also observed at significance level of P < 0.001 (uncorrected), no significant findings were observed within the other selected regions (prefrontal cortex and ACC) at this significance threshold.

Lifetime cannabis use

We observed a positive correlation between brain morphology and lifetime cannabis use (‘joints’) only at a significance threshold of P < 0.001 uncorrected. Specifically, this correlation was observed between the volume of the most caudal portion of the rectal gyrus-subgenual cingulate cortex and the accumulated number of joints consumed (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Correlations between regional brain volumes and lifetime cannabis use (‘joints’) were not affected by COMT genotype.

Discussion

This study provides evidence of the impact of COMT Val158Met genetic variation on brain structure in a group of early-onset chronic cannabis users compared with healthy controls using VBM. Our results show a significantly influence of the COMT polymorphism in bilateral ventral caudate nucleus volume in both groups but in an opposite direction: more copies of val allele was associated with lesser volume in chronic cannabis users and more volume in controls. An opposite pattern was observed for the left amygdala; the greater number of copies of val allele was associated with increased volume in chronic cannabis users and decreased volume in controls. We also identified a significant positive correlation between caudal rectal gyrus-subgenual cingulate cortex volume and the number of joints consumed. Finally, we reported an almost significant gray matter volume increase in the postcentral gyrus of the left hemisphere in chronic cannabis users.

The observed interaction between COMT genotype and chronic cannabis use on brain morphology is a novel and interesting finding, particularly given current models of substance use disorders. For instance, it has been proposed that the transition to addiction may begin with an increased excitability of the mesolimbic dopamine system followed by a cascade of neuroadaptations in areas related to addiction circuitry, such as the ventral striatum, which has a major role in the acute reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse (Koob & Volkow 2010). In this sense, the activation of dopamine, which may be influenced by COMT genotype, contributes to increased excitability of the ventral striatum with decreased glutamatergic activity during withdrawal and increased glutamatergic activity during drug-primed and cue-induced drug seeking (Koob & Volkow 2010). Similar to other drugs of abuse, cannabinoids facilitate the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (Tanda, Pontieri & Di 1997), despite the mechanism by which this occur remaining unknown. On the other hand, several preclinical studies have reported the impact of variation in dopamine neurotransmission, especially extracellular dopamine concentration, on neuronal growth and survival, particularly in striatum (Santiago et al. 2000). Animal knockout models with reduction in dopamine signaling show important impairments in neuronal differentiation (Zhou & Palmiter 1995). Chronically elevated extracellular dopamine concentration is neurotoxic (Santiago et al. 2000) and alters the expression of the BDNF (Fumagalli et al. 2003). Research in animal models suggests that exogenous cannabinoids, like THC, facilitate dopaminergic neurotransmission in several regions of the brain, including the striatum and prefrontal cortex (Maldonado et al. 2011). Human neurochemical imaging studies have reported inconsistent results, with only one study reporting a modest increase in dopamine striatal concentrations (Bossong et al. 2009). However, there is evidence that cannabis may play a role in modulating striatal function (Bhattacharyya et al. 2009b, 2012). Over- and under-stimulation may potentially result in impaired neuronal growth and survival, indicating that an optimum range for extracellular dopamine may exist (Honea et al. 2009), which may be region specific and influenced by genetics and environment.

Few studies have described the influence of Val158Met polymorphism on brain structure in healthy subjects (Ohnishi et al. 2006; Zinkstok et al. 2006; Honea et al. 2009; Ehrlich et al. 2010; Barnes et al. 2012). In 151 healthy volunteers, subjects carrying the val allele had a significantly smaller volume of the hippocampus and parahippocampus gyrus (Honea et al. 2009) relative to met homozygotes. Conversely, val-alleles carriers were also shown to have a non-significant trend-level effect of increased volume in the prefrontal cortex (Honea et al. 2009). Consistently, another study also described a linear effect of COMT genotype on medial temporal lobe volumes in 114 healthy individuals (Ehrlich et al. 2010). In this study, val-allele carriers had decreased volumes in the amygdala bilaterally and in the right hippocampus, with slightly greater effect in the left amygdala (Ehrlich et al. 2010). In line with the evidence mentioned above, we also found a decreased volume in the temporal lobe of val-allele carrying subjects in the control group, although it was restricted to the left amygdala. The modest size of our sample may have contributed to the relative localized effect of genotype that we have observed. In contrast, one study did not detect a main effect of genotype in the medial temporal lobe in 76 controls (Ohnishi et al. 2006), and two other studies found no group differences in regional gray matter density (Zinkstok et al. 2006) and volume (Barnes et al. 2012) as a function of genotype in 154 and 82 young healthy adults, respectively. It has been suggested that volume measures, as opposed to density measures, may be more sensitive indicators of genotype-related alterations (Zinkstok et al. 2006; Honea et al. 2009).

To the best of our knowledge, no previous structural or functional imaging study has focused on the influence of COMT genotype in cannabis users. However, it is remarkable to note that the effects of chronic cannabis use on brain structure and integrity are consistent with studies showing similar alterations in patients with schizophrenia (Bhattacharyya et al. 2009a). Morphometric studies have consistently reported up to 6% volume reductions in the hippocampus and the amygdala in schizophrenic patients (Honea et al. 2005), suggesting that these structural changes could reflect a central pathophysiological process associated with the illness. Furthermore, cannabis use or dependence in schizophrenic patients has been associated with smaller anterior (Szeszko et al. 2007) and posterior cingulate cortex (Bangalore et al. 2008), and cerebellar white-matter volume reduction (Solowij et al. 2011), and those who continue to use cannabis show greater loss of gray matter volume than those who do not (Rais et al. 2008). On the other hand, the COMT polymorphism has shown to influence brain structure and function in people at high risk of psychosis and schizophrenia in cingulate, lateral prefrontal cortex and temporal regions (Ohnishi et al. 2006; McIntosh et al. 2007; Ehrlich et al. 2010; Raznahan et al. 2011). In particular, the COMT Met allele has been associated with larger, and the val allele with smaller, medial temporal lobe volumes in schizophrenic patients, suggesting that the val allele may contribute, at least in part, to lower medial temporal volumes in these patients (Ehrlich et al. 2010). Interestingly, in our chronic cannabis users for whom other schizophrenia risk factors were exhaustively excluded, we found that the met allele was associated with lower, and the val allele with higher, left amygdala volume, providing further evidence of how the environment and genetics may interact to influence the brain structure.

We also observed a positive correlation between caudal rectal gyrus-subgenual cingulate cortex volume and the number of ‘joints’ used (both lifetime and the year before the study), which has not been previously reported (Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Cousijn et al. 2012). We have found no other correlations, despite an apparent inverse relationship existing between the amounts of cannabis used and (para-) hippocampal and amygdala volumes (Lorenzetti et al. 2010). These volumetric discrepancies reported across human studies may be due to differences in imaging methods (e.g. image resolution, used of automated volumetric versus manual methods), cannabis use pattern (age of onset, length of use, frequency, quantity of use, concentration of THC of ‘joint’), and demographic characteristics, which easily could lead to non-comparable samples that difficult the interpretation of results (Lorenzetti et al. 2010). For instance, samples with greater cannabis exposure (Matochik et al. 2005; Yücel et al. 2008) have demonstrated reductions in medial temporal brain regions, while samples with a relatively lower quantity of smoked cannabis, more similar to our sample, have exhibited no morphological changes (Wilson et al. 2000; Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Cousijn et al. 2012). Furthermore, our results support that additional factor, such as the genetic influence may also be determinant on brain morphology.

Animal studies have consistently demonstrated that THC induces dose-dependent neurotoxic changes in brain regions that are rich with cannabinoid receptors (Landfield, Cadwallader & Vinsant 1988), such as hippocampus, septum, amygdala and cerebral cortex (Heath et al. 1980; Lawston et al. 2000; Downer et al. 2001). In contrast, human imaging studies that have examined regular cannabis users present contradictory findings (Lorenzetti et al. 2010), insomuch as both positive (Yücel et al. 2008) and negative (Jager et al. 2007) influences on brain structure have been noted. In line with other published studies and recent reviews (Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Martin-Santos et al. 2010), we found no differences between groups in terms of global measures, but we reported a trend-level increase in gray matter volume of the left postcentral gyrus in chronic cannabis users. The only other VBM study in chronic cannabis users also showed cannabis users to have greater gray matter tissue density in the left pre and postcentral gyrus (Matochik et al. 2005). Interestingly, recent data from animal studies suggest that sensorimotor cortex may be especially vulnerable to cannabis abuse during adolescence due to the different developmental trajectories of CB1 expression (Heng et al. 2011). Thus, while in medial prefrontal and in limbic/associative regions seems to be a pronounced and progressive decrease in CB1 expression, major changes in sensorimotor cortices occurred only after the adolescence period, suggesting that cannabis abuse during adolescence may have a relatively more impact on sensorimotor functions (Heng et al. 2011). Exogenous cannabinoid administration may alter astrocyte functioning, which play a critical role in eliminating weaker connections (Bindukumar et al. 2008). By interfering with these processes, cannabis exposure during adolescence may impair typical pruning and ultimately result in larger regional volumes in specific brain areas. The mentioned VBM study also reported other structural differences that we have not observed despite having a greater sample size, such as a greater gray matter tissue density in right sensorimotor area, right thalamus and white-matter tissue density differences in parietal lobule, fusiform gyrus, lentiform nucleus and pons (Matochik et al. 2005). Discrepancies could be explained by differences in cannabis use parameters (such as pattern of cannabis use, early onset), sociodemographic features (we included only Caucasian subjects that were on average 5 years younger) and sample characteristics (i.e. sample size).

No other structural differences between the chronic cannabis users and healthy controls were found using our VBM approach, but it has been described both positive and negative results when studies investigated specific regions, such as hippocampus, parahippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum [for review see (Lorenzetti et al. 2010; Martin-Santos et al. 2010)].

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we use a relatively small sample size for a structural neuroimaging study; however, the strength of our observed findings instills confidence in their validity. The results cannot be generalized to all chronic cannabis users as our sample was comprised of a group of male early-onset regular cannabis users without the confounding effect of other drug use and neurological or other psychiatric illnesses. The cross-sectional design does not allow us to address the question whether cannabis abuse alters brain morphology although its impact on normal neurodevelopment or if the observed structural differences are pre-existent, causing individuals to be more prone to develop cannabis dependence (Cheetham et al. 2012). Overall, despite methodological differences across previous structural studies, findings appears to support of the idea that regular cannabis use may have a modulatory structural effect on specific brain regions, and that the Val158Met polymorphism may play a particular role in the sensitivity of these effects of cannabis on brain morphology.

In summary, our findings support recent reports of neuroanatomical changes associated with cannabis use and, for the first time, reveal that these changes may be influenced by the COMT genotype. Further prospective, longitudinal research is needed to examine the gene-environment influence and the mechanisms of long-term cannabis related brain impairment.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been partially supported by grants: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, PNSD: PI101/2006 and PNSD: PI041731/2011 (R.M-S.), PNSD: SOC/3386/2004 (M.F.), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, ISCIII-FEDER, RTA:RD06/0001/1009 (M.T.). DIUE de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2009 SGR 718 (R.D.T., M.F.) and SGR 1435 (R.M.-S., J.A.C.); SGR 2009/719 (R.D.T., M.F.); C.S-M. is funded by a Miguel Servet contract from the Carlos III Health Institute (CP10/00604). B.J.H. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Clinical Career Development Award (I.D. 628509). J.A.C receives a CNPq (Brazil) productivity award (IC). None of the grants had further role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript and decision to submit it for publication. The authors disclose no competing financial interests.

Authors Contribution

RM-S, CS-M, MF and JP were responsible for the study design. ABF, ML-S and LBH contributed to the acquisition of the clinical and neuroimaging data. CS-M, MLS, LBH and AB performed the neuroimaging and statistical analysis. AB, CS-M and RM-S drafted the manuscript. SB, JP, BJH and JAC provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors contributed and critically reviewed the content and have approved the final version of the manuscript.