The effect of government-guided funds on target industries in development zones – Evidence from China

Abstract

The interplay between state-led interventions and market-driven forces has gained unparalleled prominence. This paper examines China's strategic use of government-guided funds (GGFs) and their consequential impact on its national high-tech zones (NHZs). Through an analysis of 1599 annual observations from 123 NHZs spanning 2007–2019, we reveal a compelling correlation between GGF investments and augmented industrial activity. Our findings indicate that NHZs benefitting from GGF allocations evidenced a significant 5.5% surge in industrial activity. Two underlying mechanisms drive this relationship. The leverage mechanism portrays GGFs as attractors of private social capital to tech-centric ventures within NHZs. Meanwhile, the guidance mechanism underscores NHZs' strategic clustering of high-tech sectors, amplifying benefits from shared resources and knowledge. Empirical analysis affirms both mechanisms, showing NHZs with robust social capital magnetism and tech clustering derive pronounced gains from GGF interventions. Our results carry practical implications for both policymakers and academicians, offering a nuanced understanding of the symbiotic relationship between fiscal strategies and industrial growth.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the global economic landscape, countries face the challenge of balancing innovation-driven growth with financial stability (Acemoglu et al., 2006; Aghion et al., 2015; Brunnermeier & Sannikov, 2014; Hall, 2002; Rajan & Zingales, 1996). China stands out in this context, adeptly leveraging both state-led and private sector approaches to fuel its industrial expansion (Alder et al., 2016; Bo, 2020; Lu et al., 2019, 2023; Zheng et al., 2017). This study probes a pivotal component of China's fiscal and strategic architecture: the implementation of government-guided funds (GGFs) and their impact on the trajectory of its national high-tech zones (NHZs). We aim to investigate whether GGF investments act as instruments accelerating NHZs' industrial growth, or if they remain as mere policy signals with negligible tangible outcomes.

State interventions have historically been pivotal in shaping market dynamics (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; Rodrik, 2008; Stiglitz, 1989). Within China's unique place-based policy paradigm, the creation and promotion of development zones signify a strategic move to facilitate specific economic outcomes (Wang, 2013; Zeng, 2011). These NHZs, positioned as nexuses of innovation, provide an insight into its broader growth strategy (Tian & Xu, 2022). Simultaneously, the rise of GGFs gives us an avenue to investigate the strategic financing mechanisms underpinning China's economic activities. More than just financial conduits, GGFs crystallise the state's broader strategic intent, nudging sectors perceived as the vanguard for future economic transitions (Colonnelli et al., 2024; Cumming, 2007; Cumming et al., 2017; Grilli & Murtinu, 2015). These sectors, characterised by their technological intensity and innovation potential, lie at the heart of China's aspirations to transition from a production-centric economy to a globally competitive innovation hub.

Cumming and Li (2013), Brander et al. (2015) and Guerini and Quas (2016) have accentuated the multifarious dimensions of GGFs. However, gaps remain, especially concerning their effectiveness in realising the industrial objectives in high-tech sectors (Bertoni & Tykvová, 2015; Grilli & Murtinu, 2014). Also, the existing literature centres predominantly on the exit performance of GGFs, often overlooking their broader industrial implications (Alperovych et al., 2015; Guerini & Quas, 2016; Luukkonen et al., 2013; Suchard et al., 2021). For instance, Suchard et al. (2021) examine the effects of Chinese state-owned venture capital (GVC) on start-up exits and venture fund performance and find that firms with government venture capital ties are more likely to exit successfully, particularly through mainland initial public offerings (IPOs). This is attributed to China's regulated IPO landscape and GVCs' ability to navigate political uncertainties.

NHZs, by design, serve as centres of integrated innovation (Howell, 2019). Their success is tied to various factors, including capital accessibility, emphasising the role of GGFs (Li et al., 2023). Existing literature, such as Busso et al. (2013), Briant et al. (2015) and Austin et al. (2018), among others, have examined the tangible impacts and financial implications of place-based strategies. Nevertheless, the debate continues, enriched by divergent perspectives from Ossa (2015) and Criscuolo et al. (2019).

In the context of China, GGFs, by their inherent design and function, channel investments into regions with perceived growth potential (Suchard et al., 2021). When these funds are directed towards NHZs, they act as an infusion of essential capital that can be leveraged to upscale industrial activities (Bayar et al., 2019). In addition, the funds from GGFs can also be utilised to build or upgrade necessary infrastructure, such as transportation networks, power grids and communication systems. Specifically, they can facilitate the adoption of cutting-edge technologies that can radically optimise industrial processes, thereby fostering growth (Puri & Zarutskie, 2012). Further, with financial backing from GGFs, NHZs can attract top-tier talent and expertise (Gompers & Lerner, 2001; Zider, 1998). An influx of talent invariably correlates with enhanced industrial productivity and innovation. Hence, GGF investments do not merely act as passive infusions of capital into NHZs. Instead, they trigger a multi-faceted chain reaction that touches upon talent attraction, infrastructure development and advanced technology adoption (Standaert & Manigart, 2018). Thus, we propose that GGF investments significantly promote the industrial development of NHZs.

Using a dataset spanning 1599 annual observations from 123 NHZs from 2007 to 2019, we examine the dynamics between these state-directed financial mechanisms and the progression of high-tech industries within NHZs. Specifically, we assess the impact of development zone policies on designated target industries. The empirical analysis indicates a positive and statistically significant association between GGF investments and the growth of target industries within NHZs. More specifically, NHZs that benefited from GGF investments experienced a 5.5% rise in electricity consumption (an indicator of industrial activity), compared to NHZs without such funding.

In our subsequent analysis, we examine the mechanisms underpinning the observed positive correlation. Specifically, the analysis focuses on two potential pathways: the leverage mechanism, rooted in the magnetism of social capital, and the guidance mechanism, centred on industry clustering within NHZs.

The leverage mechanism posits that government intervention, through GGFs, acts as a signalling mechanism, attracting private social capital to start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the technology domain (Colonnelli et al., 2024; Hellmann & Puri, 2002; Lerner, 2000). This suggests that NHZs with a stronger capability to lure social capital would witness a more pronounced positive effect of GGF investments. On the other hand, the guidance mechanism emphasises the clustering or agglomeration of target industries within NHZs (Gurrieri, 2019; Porter, 2000). Development zones aim to intentionally create such clusters to benefit from shared resources, knowledge spillovers (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996) and other synergies. Thus, zones with more concentrated high-tech industries would reflect a heightened influence of GGF investments on target industry development (Gompers & Lerner, 2001). As expected, the empirical results confirm that both the influx of social capital and the agglomeration of target industries within NHZs emerge as critical mechanisms explaining the positive impact of GGF investments on target industrial growth in these zones.

This paper contributes significantly to at least two main streams of academic literature. Firstly, we focus on GGFs and their interplay with NHZs. Prior to this study, the literature focuses either on state-sponsored financial mechanisms or on the role of high-tech zones in industrial growth (e.g., Billings, 2009; Hanson & Rohlin, 2011; Neumark & Kolko, 2010; Wang, 2013). By contrasting these two elements, we offer a composite understanding of the interplay between state-led financing mechanisms and spatial industrial strategies.

Secondly, we explore the role of government-backed venture funds (i.e., GGFs) in venture capital. Previous research, such as Brander et al. (2015), suggests that GGFs can enhance successful exits and innovation. In contrast, other studies like Brander et al. (2010) indicate potential inefficiencies in GGF investments. Importantly, much of the existing literature focuses on the exit performance of GGFs, often sidelining their broader impact. Our study pivots from this trend to investigate how GGF investments contribute to the development of target industries within NHZs. By dissecting these underlying mechanisms – social capital attraction and the guidance mechanism – the study also facilitates an understanding of how and why GGF investments influence target industries within NHZs.

This paper contributes significantly to the theoretical understanding of state-led financial mechanisms and their impact on industrial growth within high-tech zones. By integrating the perspectives of place-based policy and government-backed venture capital, we advance the theoretical framework that explains how targeted financial interventions can catalyse industrial development. Our study extends the existing literature by elucidating the dual mechanisms of social capital attraction and industry clustering, providing a nuanced understanding of how GGFs serve as pivotal instruments in achieving strategic economic objectives. This theoretical exploration not only bridges the gap between state policy and industrial outcomes but also offers a comprehensive model that can be applied to other contexts and economies.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses China's development zone policy and related institutional features and Section 3 reports our data sources and variable construction. In Section 4, we present the baseline analysis and robustness checks. Section 5 explores the underlying mechanisms influencing the observed relationship. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 INSTITUTION BACKGROUND

2.1 Overview of China's development zones

By 2021, China had an impressive portfolio of 615 national-level development zones, according to the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. These zones spanned diverse categories, including 230 national-level economic and technological development zones, 176 high-tech industrial development zones, 167 customs special supervision zones (which further bifurcate into bonded zones and export processing zones), 19 border or cross-border economic cooperation zones, and 23 other classifications. Adding to this landscape, China also hosted an additional 2108 provincial-level development zones.

Each of these development zones aligns with distinct hierarchies and objectives. National-level zones, bearing the endorsement of the State Council, encapsulate a broad spectrum ranging from economic and technological, to high-tech industrial realms. On the other hand, provincial zones, steered by provincial governments, predominantly fall into two clusters: economic development zones that mirror their national counterparts and specialised industrial parks. These parks are pivotal, aiming to catalyse specific industrial ventures and projects.1

The allure of national zones rests in their comprehensive incentive structures, which often eclipse those of provincial zones. However, when it comes to sheer numbers and expansive territorial coverage, provincial zones take the lead. These provincial entities are particularly strategic, nurturing industrial hubs that predominantly orbit around resource-intensive and labour-centric activities.

2.2 Strategic divergences and targeted industries

These zones do not adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to industrial development. The national high-tech zones, typically nestled in prime urban locales and coastal areas, gravitate towards the high-tech sector. They often seek to amalgamate native resources with advanced foreign technological assets and managerial acumen. In contrast, provincial zones, while still essential, focus on galvanising regional economic uplift and driving industrial modernisation. Bonded zones, usually established in pivotal trade regions, are attuned to the nuances of foreign commerce, while export processing zones exclusively engage in activities like processing imported raw materials for subsequent export.

Given this vast and varied ecosystem, our research narrows its lens specifically on NHZs. This focus is driven by the enhanced preferential policies these zones offer, paired with their alignment to the industries that are also targeted by GGFs (Tian & Xu, 2022).

2.3 Historical context

Stepping back to appreciate the bigger picture, these development zones, in the tapestry of China's economic metamorphosis, signify essential nodes of growth (Yeung et al., 2018). Historically, these zones have served as pivotal spatial testing grounds, facilitating industrial congregations, ensuring job avenues and pushing the envelope of economic progress. Illustrative cases like the Shenzhen Special Administrative Region and the Shanghai Pudong New Area underline their transformative prowess.

Central to their operational philosophy is the strategic selection of target industries, which are deemed as potential growth engines (Wang & Wei, 2010). These chosen industries, often embryonic in their developmental arc, grapple with challenges, from establishing market trust (Akerlof, 1970), and navigating the maze of information asymmetry (Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981), to securing vital R&D funds (Hall & Lerner, 2010). Yet, with the infrastructural and policy backing of development zones, they thrive, innovate and shape industrial horizons.

2.4 Government-sponsored venture capital

Beyond spatial economics, another dimension crucial to China's industrial strategy is the role of GGFs. These funds, designed as remedies to market inefficiencies, play a salient role in nurturing high-tech start-ups. China's venture capital trajectory, in contrast to developed economies, has been meticulously crafted through government channels. With a clear agenda to bridge the investment deficit faced by start-ups, GGFs are envisaged to mobilise private investment into early-stage ventures (Brander et al., 2015).

The statistics further underline China's commitment. As of 2021, according to PEdata, China boasts a robust infrastructure of 1988 GGFs, injecting an impressive RMB 6.16 trillion into their initiatives. What is pivotal here is the nuanced role of GGFs in the broader developmental narrative. Unlike conventional industrial policies, GGFs serve as strategic levers to spur high-quality development within specific industries. Governed by state oversight, they ensure a seamless alignment between investment thrusts and government developmental blueprints. By leveraging financial capital, they guide social capital towards target industries, thereby amplifying industrial growth trajectories.

3 DATA AND SUMMARY STATISTICS

3.1 Sample selection and data sources

Our study utilises a dataset with three critical dimensions, reflecting the comprehensive nature of the research framework. The first dimension focuses on electricity consumption patterns within NHZs, obtained from provincial and city statistics bureaus. This data offers valuable insight into the energy utilisation dynamics in these zones. The second dimension deals with the operations of GGFs, data for which has been extracted from PEdata – a leading resource for venture capital activities in China.2 To ensure accuracy and completeness, this data has undergone additional manual cross-check. The third dimension comprises data sourced from the China City Statistical Yearbook, providing an essential context of the cities hosting these NHZs and their respective urban nuances.

Our aim is to gauge the long-term effects of GGFs on NHZs' industrial evolution. To achieve this, we examine a policy impact window that spans 5 years before and after a specific GGF's implementation. An important observation is that GGF activities, especially investments, intensified post-2012. However, in early 2020, the unexpected emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant interruptions in NHZs due to stringent city lockdowns and epidemic control measures. Given these dynamics, our chosen data collection timeline runs from 2007 to 2019.

To ensure that the dataset is robust and representative, several preprocessing steps were initiated. Firstly, we eliminated samples that had an investment entry time of less than 5 years as of the end of 2019. This was to ensure the longevity of the sample's policy impacts. Additionally, NHZs located in the four distinct municipalities – Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing – were excluded. This decision is rooted in the understanding that these municipalities possess specific economic characteristics and dynamics that might skew the results. In the final preprocessing step, NHZs that lacked electricity consumption data were omitted.

After the data selection criteria, the final dataset includes 1599 annual observations covering 123 NHZs over an expansive 13-year span, from 2007 to 2019. This dataset is pivotal for the ensuing empirical analyses, providing a foundation upon which the study's conclusions will be drawn.

3.2 Variable measurement

3.2.1 Dependent variable

Amid the conventional reliance on gross domestic product (GDP) as the primary metric for evaluating economic health and development progress, the method presents several constraints regarding the authenticity and precision of data. Feenstra et al. (2015) articulate the pitfalls in GDP computations, such as methodological inconsistencies, potential data distortions and imprecise price indices. These limitations necessitate an alternative evaluative approach, especially in capturing the nuanced dynamism within NHZs.

In this context, our study adopts electricity consumption as a more reflective and reliable indicator of industrial development, echoing the insights of Henderson et al. (2012) that such data can effectively mirror economic activity, particularly in environments where traditional metrics might falter. This shift is not merely methodological but anchored in the fundamental correlation between energy demand and economic vibrancy, as outlined by Fernald (2014). Economic expansions, evidenced by a robust GDP, inherently stimulate increased production and commercial activities, thereby escalating electricity usage (Steinbuks & Foster, 2010). Conversely, a recessionary phase, marked by a GDP contraction, aligns with reduced industrial output and subsequent diminished power consumption (Wolfram et al., 2012).

By consolidating data meticulously sourced from provincial and municipal statistics bureaus, this research seeks to circumvent the shortcomings associated with GDP reliance. The strategic pivot to electricity consumption data aims to yield a more nuanced, objective and precise depiction of the economic tempo within NHZs, thereby offering a more holistic understanding of their developmental trajectory. This approach not only fortifies the methodological robustness of our analysis but also enhances the interpretative value of our findings in the broader discourse on regional industrial development.

3.2.2 Control variable

To account for potential influencing factors affecting industrial development within high-tech zones, this study incorporates several control variables based on the existing literature (Chen et al., 2009; Tian & Xu, 2022; Tsui, 2011). These control variables have been sourced from the China City Statistical Yearbook, covering the period from 2007 to 2019. This ensemble includes metrics, such as: the GDP fraction derived from the primary industry of the host city of the NHZ (GDP1); the slice of GDP attributed to the city's secondary industry (GDP2); the share of GDP stemming from the tertiary industry of the city (GDP3); the portion of GDP allocated to local government budgetary expenditure (Govexp); the fraction of GDP anchored on the tangible deployment of foreign direct investments in the city (Fdi); the ratio of year-end deposits with financial establishments vis-à-vis GDP (Fisav); and the contribution of total postal and telecommunication services to the city's GDP (Infor).

In instances where data for these control variables were missing, a data imputation technique is adopted. The mean values from city-year data a year prior and post the missing data timeframe are used for this purpose. Appendix 1 provides definitions of these main variables. Descriptive statistics for these variables, which are utilised in our empirical analysis, are presented in Table 1. The mean value for Ln(Ele) is 12.730. Nighttime light intensity (NL) averages at 15.136. GDP1 has a mean of 0.093, while GDP2 and GDP3 average 0.498 and 0.408, respectively. Fdi stands at a mean of 0.023. Fisav averages 1.343. For Govexp, the mean value is 0.147. Lastly, Infor has a mean of 0.003.

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln(Ele) | 1599 | 12.730 | 1.255 | 9.226 | 15.940 |

| NL | 1599 | 15.136 | 11.564 | 0.000 | 56.215 |

| GDP1 | 1599 | 0.093 | 0.061 | 0.004 | 0.321 |

| GDP2 | 1599 | 0.498 | 0.093 | 0.165 | 0.851 |

| GDP3 | 1599 | 0.408 | 0.098 | 0.118 | 0.792 |

| Fdi | 1599 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.232 |

| Fisav | 1599 | 1.343 | 0.652 | 0.015 | 7.562 |

| Govexp | 1599 | 0.147 | 0.071 | 0.001 | 1.485 |

| Infor | 1599 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

- Note: This table provides a comprehensive set of descriptive statistics that cover the entire sample period, from 2007 to 2019. Ln(Ele) represents the natural logarithm of electricity consumption; NL reflects Nighttime Light; GDP1, GDP2 and GDP3 stand for the contributions of primary, secondary and tertiary industries to city-level GDP, respectively. Govexp is the proportion of GDP accounted for by local government budgetary expenditure, Fdi denotes the proportion of GDP accounted for by actual utilisation of foreign direct investment in the city, Fisav indicates the share of year-end deposits of financial institutions in GDP, and Infor represents the share of total postal and telecommunication services in GDP. Variable definitions are provided in Appendix 1.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1 Baseline results

The current proliferation of GGFs presents an opportune quasi-natural experimental context for investigating their impact on the industrial growth of NHZs. Two salient features of GGF investments provide a favourable framework for mitigating potential biases. First, the investment choices made by GGFs hinge on the specific investment institutions involved, lending them a degree of exogeneity (Da Rin et al., 2013). This characteristic helps mitigate concerns related to reverse causality and addresses endogeneity issues that may otherwise confound the analysis.

where signifies the level of industrial development in NHZ i in year t, expressed as the natural logarithm of electricity consumption; is a policy indicator variable equalling one when an NHZ has received investments from GGFs and zero otherwise; serves as a time indicator, taking a value of one indicating the initial year and subsequent years following GGF investment in an NHZ, and zero otherwise. If GGFs indeed promote the industrial development of NHZs, should be both significant and positive. The variables encompass a set of control variables, and the variable definition is provided in Appendix 1. and represent time and individual fixed effects, respectively.

Panel A of Table 2 presents the baseline results, which scrutinise the impact of GGF investments on electricity consumption within NHZs. In column (1), the coefficient of Treat × Post is positively significant at the 1% level, demonstrating the pronounced, positive ramifications of GGF investments on NHZs' electricity consumption (a proxy for industrial vigour), thereby indicating a significant promotion of industrial development by GGFs.

| Variables | Panel A: The baseline results | Panel B: Analysis of parallel trends | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Variable | Ln(Ele) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||

| Treat × Post | 0.057*** | 0.055*** | Treat × pre_5 | −0.006 |

| (3.30) | (3.11) | (−0.14) | ||

| GDP1 | −0.352 | Treat × pre_4 | 0.037 | |

| (−0.49) | (1.13) | |||

| GDP2 | −0.202 | Treat × pre_3 | 0.013 | |

| (−0.30) | (0.43) | |||

| GDP3 | −0.183 | Treat × pre_2 | 0.029 | |

| (−0.26) | (0.91) | |||

| Current | 0.031 | |||

| Fdi | 0.474* | (0.97) | ||

| (1.78) | Treat × post_1 | 0.082*** | ||

| Fisav | −0.001 | (2.59) | ||

| (−0.07) | Treat × post_2 | 0.070** | ||

| Govexp | −0.292*** | (2.22) | ||

| (−3.78) | Treat × post_3 | 0.080** | ||

| Infor | 2.212** | (2.55) | ||

| (2.20) | Treat × post_4 | 0.110*** | ||

| (3.50) | ||||

| Treat × post_5 | 0.018 | |||

| (0.53) | ||||

| Constant | 12.497*** | 12.720*** | Constant | 12.494 |

| (1051.38) | (18.56) | (1019.08) | ||

| Observations | 1599 | 1599 | Observations | 1599 |

| Adjust_R2 | 0.485 | 0.489 | Adjust_R2 | 0.485 |

| City and year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | City FE | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the findings of the staggered DiD model. Panel A presents the baseline results, and the result of the parallel trends test is provided in Panel B. Treat equals 1 if an NHZ has received GGF investments and 0 otherwise, and Post is a dummy variable set to 1 to indicate the initial year and subsequent years following GGFs' investment in an NHZ, and to 0 otherwise. Variable definitions are provided in Appendix 1. Coefficient estimates are provided with their respective t-statistics shown in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Diving into the economic implications, our estimations presented in column (2) of Table 2, spotlight a 5.5% (that is, 0.055% × 100) elevation in electricity consumption for the treatment cohort, relative to its control counterpart following GGF investments. This result not only signifies the potency of GGF capital but also reinforces its role as a catalyst in amplifying industrial productivity.

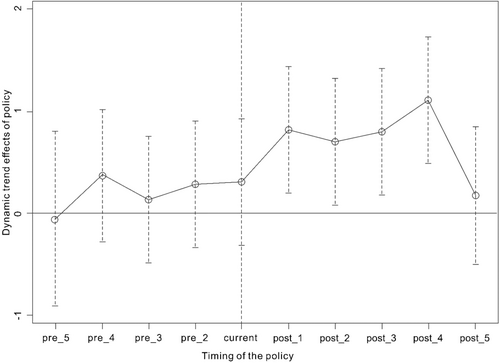

The coefficient of this interaction term (where M and N represent the number of periods before and after the policy, respectively) assesses the difference in trends between the treatment and control groups during period (that is, *). Furthermore, the annual observations of both the treatment and control groups are utilised as the sample, with a window period spanning 5 years before and after the initial GGF investment (referred to as ). If the assumption of parallel trends holds, the estimated coefficients of the interaction terms prior to the year of GGFs' first investment should not exhibit statistical significance different from zero.

In Panel B of Table 2, the result highlights that during the initial 5 years preceding the first GGF investment, the estimated coefficients of the interaction term do not attain statistical significance at all, until the first year subsequent to the GGF investment, lending support to the parallel trend hypothesis.

We now investigate the dynamic economic effects of GGF investments across years through visual graphical representations based on the regression outcomes. To mitigate covariance effects, the period prior to the event (pre_1) is excluded. As depicted in Figure 1, the estimated coefficients exhibit fluctuations around zero (with the 95% confidence interval encompassing a value of zero) preceding GGF investments. It reveals no discernible differentials between treatment and control groups in the pre-GGF investment period. Yet, post GGF intervention, a consistent, pronounced positive impact emerges, reinforcing the symbiotic relationship between GGF investments and industrial growth within NHZs.

4.2 Robustness checks

4.2.1 PSM–DiD

While the traditional DiD method provides evidence supporting the positive impact of GGF investment on the industrial growth of NHZs (Bertrand et al., 2004), concerns persist regarding potential systematic differences between the treatment and control groups of NHZs (Tian & Xu, 2022). To address issues such as endogeneity and selectivity bias, we employ the propensity score matching DiD (PSM-DiD) approach (Imai et al., 2008). This method aims to re-evaluate the policy effects of GGF investment while minimising disparities between the treatment and control groups before GGF intervention.

The PSM-DiD procedure involves constructing a Probit regression model and applying a period-by-period matching method to pair NHZs. Specifically, NHZs in the treatment and control groups are separately matched within each of the first n periods of the treatment effect. This pairing, grounded in past economic indicators such as GDP1, GDP2 and GDP3, etc., serve as the determinants of the matching criteria. Consequently, we identified 42 pairs of matched NHZs. In unreported results, we confirm the absence of systematic disparities post-matching between the treatment and control groups (results available upon request).

Column (1) of Table 3 illustrates the transformative influence of GGF investments on NHZs' industrial vigour using the PSM-DiD apporach. In the immediate year succeeding the GGF investment, electricity consumption in the treatment NHZs increased by 3.3% (that is, 0.033% × 100), relative to their control counterparts, reaffirming the robustness of our baseline results regarding the substantial positive impact of GGF investment on industrial development in NHZs.

| Ln(Ele) | NL | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Treat × Post | 0.031* | 0.079 | 0.085*** | 0.074*** | −0.014 |

| (1.75) | (0.15) | (3.28) | (3.80) | (−0.77) | |

| GDP1 | 15.128 | 20.439 | −0.040 | −0.306 | |

| (0.73) | (0.99) | (−0.15) | (−0.43) | ||

| GDP2 | −7.137 | 20.580 | −0.049 | −0.242 | |

| (−0.36) | (0.99) | (−0.53) | (−0.36) | ||

| GDP3 | −12.865 | 20.474 | −0.115 | −0.231 | |

| (−0.63) | (0.99) | (−1.08) | (−0.33) | ||

| Fdi | −7.447 | 0.133 | 0.122 | 0.472* | |

| (−0.97) | (0.42) | (0.51) | (1.77) | ||

| Fisav | 1.083*** | −0.004 | 0.03 | −0.001 | |

| (3.06) | (−0.34) | (0.12) | (−0.08) | ||

| Govexp | −1.322 | −0.230* | −0.220** | −0.299*** | |

| (−0.59) | (−1.82) | (−2.58) | (−3.86) | ||

| Infor | −69.191** | 1.390 | 0.004 | 2.530** | |

| (−2.38) | (1.31) | (0.01) | (2.53) | ||

| Constant | 13.912*** | 19.188 | −7.843 | 10.143*** | 12.753*** |

| (342.20) | (0.97) | (−0.38) | (53.07) | (18.56) | |

| Observations | 504 | 1599 | 1107 | 1508 | 1599 |

| Adjust_R2 | 0.487 | 0.184 | 0.372 | 0.483 | 0.486 |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table presents the resultss of various robustness checks. Column (1) underscores the transformative impact of GGF investments on the industrial vitality of NHZs, employing the PSM-DiD approach. Column (2) displays results obtained by substituting the dependent variable, wherein the Nighttime Light Data from national-level high-tech zones serves as the dependent measure. Column (3) reports results of sensitivity analyses related to policy-time variations. Column (4) presents a subsample analysis that controls for the upgrading effect. Column (5) shows the results of placebo tests. Variable definitions are provided in the Appendix 1. Coefficient estimates are provided with their respective t-statistics shown in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

4.2.2 Alternative measure of dependent variable

In this robustness test, we substitute the dependent variable, electricity consumption, with night-time light data for NHZs (Henderson et al., 2012). Recognising that GGF investment predominantly affects daytime operations and production activities within NHZs (Lerner, 2000), there is an inherent variance in the effect on different economic facets. Specifically, NL likely remains stable given that many companies halt operations post-daytime hours (Donaldson & Storeygard, 2016). Since the night-time light intensity is expected to remain relatively constant (or unaffected by GGF investment), it is used as a placebo test. If GGF investment primarily impacts daytime operational activities in NHZs, then logically, we shouldn't observe any pronounced shifts in night-time light intensity after the GGF investment. If the placebo test reveals significant effects in areas where none are expected (like night-time light intensity), it may suggest that other external or unobserved factors are influencing our results, potentially undermining the credibility of our baseline analysis.

The night-time light data are sourced from China National Resources and Dynamic Statistical Database. The results of this placebo test are presented in column (2) of Table 3. It shows the statistical insignificance of the Treat × Post coefficient, ascertaining the robustness and validity of our baseline observations.

4.2.3 Change in regression time window

A crucial aspect of evaluating the impact of any financial or economic policy is to assess its temporal consistency, especially in scenarios where the policy's implementation is gradual (Chen et al., 2016; Mian et al., 2014). To this end, this paper delves into understanding the longevity and stability of the influence GGF investment has on the industrial progression of NHZs.

Given that there is not a distinct, pre-defined event window given the incremental nature of GGF investment across our dataset, it is imperative to explore various time frames to ensure the robustness of the results. This exploration is even more pertinent considering the marked surge in GGF investments in NHZs starting from the year 2011. Consequently, for the purposes of this sensitivity analysis, we have chosen a time frame extending from 2011 to 2019.

The results of this analysis are presented in column (3) of Table 3. Remarkably, the coefficient of Treat × Post remains statistically significant at the 1% level within this altered time frame. Such unwavering consistency, in the context of an adjusted time window, reinforces that GGF investments have indeed had a tangible, positive effect on the industrial landscape of NHZs.

4.2.4 Controlling for the upgrading effect: a subsample analysis

In the late months of 2008, China witnessed a policy overhaul when its State Council embarked on the journey to escalate provincial-level development zones to the status of NHZs. This evolution was incremental, making the time dynamics of its effects even more crucial to understand. Such an elevation to NHZ status was expected to bring a cascade of benefits – from the magnetisation of more investments and bolstered fiscal revenues for local governments to the creation of potent economic agglomerations. However, a critical research concern arises: these significant shifts, inherently beneficial for industrial development, might mask or magnify the tangible impact of GGF investments on NHZs, leading to a potential attribution error.

Given the potential overlap in the positive influences from both these policy changes and GGF investments, isolating the effects becomes paramount. To ensure that the impact attributed to GGF investments is not confounded by the NHZ upgrading, we engaged in an additional subsample analysis. This entailed the omission of samples that underwent the metamorphosis from provincial-level zones to NHZs.

As shown in column (4) of Table 3, it becomes evident that the earlier observed statistical significance at the 1% level remains unchanged. These results emphasise the resilience and genuine nature of the impact of GGF investments on NHZs' industrial development, holding firm even when the potential confounder of NHZ upgrading is carefully removed from the analysis.

4.2.5 Placebo test

To ascertain that any observed enhancement in the industrial development of NHZs is solely attributed to the impact of GGF investments, a placebo test is conducted by replicating the baseline DiD regression while constructing an artificially designated investment year, discerning whether GGF investments were indeed the main impetus for industrial growth or if external elements played a part.

Our preliminary assessment of GGF investment patterns across the sample indicated that a vast majority, specifically 21 out of the 23 treatment cases, witnessed investment events post-2010. Consequently, the year 2010 was selected as the artificial investment year, and subsequently, we structured our sample timeframe to span from 2007 to 2013, capturing a symmetric three-year window both prior and succeeding this constructed event year. In this analysis, the dependent variable in Equation (1) was replaced with a new dummy variable, , which takes the value of 1 when NHZ becomes a recipient of GGF investment post-2010, and 0 otherwise.

The results, as presented in column (5) of Table 3, demonstrate that the coefficients of the interaction terms are not statistically significant. This observation suggests that, when the timeline of GGF investments is artificially repositioned, such investments do not appear as significant drivers for NHZs' industrial momentum. This reinforces the conclusions drawn from the baseline analysis, emphasising the pivotal role of GGF investments in driving the industrial development of NHZs.

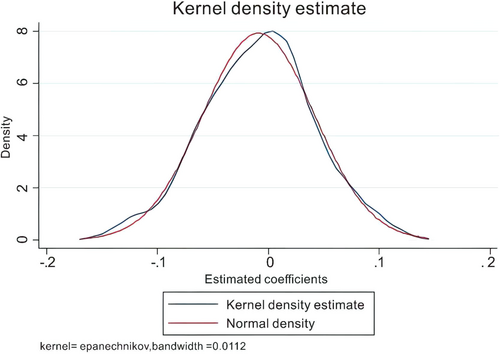

To further validate our findings, we also conducted a robustness check by redefining our control and treatment groups. We created a new control group by randomly selecting NHZs that had benefitted from GGF investments and aligned them with the original group's policy implementation schedule. This method ensured that for every NHZ receiving GGF investment in a given year, an equivalent NHZ was selected for policy implementation in the new control group that same year. The baseline model was re-estimated with this revised sample, and the process was iterated 1000 times for the placebo test. Detailed results, including the distribution of the placebo test results, are provided in Appendix 2. This analysis reinforces the credibility of our baseline findings and supports the validity of our primary research conclusions.

5 ADDITIONAL ANALYSIS

This section delves into an examination of the underlying mechanisms that shed light on the positive impact of GGF investments on the development of target industries within NHZs. This analysis aims to uncover potential mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon, with a particular focus on two key factors: the attraction of social capital, referred to as the ‘leverage mechanism’ and the stimulation of industrial agglomeration in target sectors, termed the ‘guidance mechanism’. Through empirical evidence, this section seeks to substantiate these mechanisms as plausible explanations for the observed positive effect of GGF investments on NHZs' industrial development.

5.1 Leverage mechanism

This section delves into the attraction of social capital, emphasising its impact and relevance in the financial ecosystem. Prior studies have assessed the role of state-owned venture capital institutions in the dynamics of social capital. Cumming (2007) examined the influence of government venture capital funds on private capital within the Australian context from 1982 to 2005, revealing positive associations. Cumming and Li (2013) also observed a significant positive impact on the venture capital market in the United States between 1995 and 2010, particularly in terms of the number of start-ups receiving the Small Business Innovation Research Program (SBIRP). Further, Brander et al. (2015) further substantiate this claim, employing cross-country panel data from 2000 to 2008 to ascertain a strong positive impact of government venture capital on social private investment metrics. Interestingly, Guerini and Quas (2016) state that government venture capital plays a pivotal role in diminishing information asymmetry in high-tech start-ups, enhancing their appeal to private venture capitalists.

Governmental forays into the financial sector, specifically through interventions, are typically geared towards rectifying market inefficiencies (Brander et al., 2015). GGFs, in particular, leverage governmental credibility, positioning public capital as a strong signal in the market (Alperovych et al., 2018; Colombo et al., 2016). Consequently, this will facilitate the flow of social capital into start-ups and SME tech firms, bridging any prevailing financing gaps. Essentially, these investments act as signals, attenuating risks and uncertainties for private venture capitalists, thereby catalysing increased market participation.

Given the discussed leverage mechanism, it is posited that NHZs, adept at attracting social capital, stand to gain considerably from GGF investment interventions. In contrast, those NHZs with subpar attraction abilities might find their industrial trajectories uninfluenced by GGF allocations. To empirically test this proposition, a group regression analysis is employed. The sample is classified into two distinct subgroups predicated on their inherent capability to attract social capital. This capability was quantitatively assessed using the Business Environment Index which captures diverse facets of the prevailing business milieu, developed by Peking University covering the temporal span from 2017 through 2020.

Table 4 presents the results. Columns (1) and (2) focus on the subgroup with a Business Environment Index below the treatment group's mean, while columns (3) and (4) examine the subgroup with an index above the mean. The result in column (2) reveals an insignificant coefficient for the interaction term, Treat × Post. This insignificance underscores that NHZs, with a relatively diminished capacity to attract social capital, tend to remain impervious to the pronounced effects of GGF investments, consistent with our prediction. In contrast, in column (4), the Treat × Post coefficient is significant at the 1% confidence level. Within 1 year following GGF investments, the electricity consumption in NHZs from this subgroup increased by 6.7% compared to the control counterparts, lending empirical support to our hypothesis. This reiterates the pivotal role of social capital as a facilitative mechanism in amplifying the efficacy of GGF investments within NHZs.

| Variables | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat × Post | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.072*** | 0.067*** |

| (1.55) | (1.49) | (3.24) | (3.00) | |

| GDP1 | −0.272 | −0.361 | ||

| (−0.39) | (−0.51) | |||

| GDP2 | −0.111 | −0.214 | ||

| (−0.17) | (−0.32) | |||

| GDP3 | 0.014 | −0.210 | ||

| (0.02) | (−0.30) | |||

| Fdi | 0.185 | 0.293 | ||

| (0.68) | (0.97) | |||

| Fisav | −0.002 | −0.007 | ||

| (−0.18) | (−0.53) | |||

| Govexp | −0.253*** | −0.249*** | ||

| (−3.26) | (−3.11) | |||

| Infor | 2.944** | 2.363** | ||

| (2.46) | (2.31) | |||

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1430 | 1430 | 1469 | 1469 |

| Adjust_R2 | 0.476 | 0.479 | 0.485 | 0.489 |

- Note: This table provides empirical results of the leverage mechanisms. Columns (1) and (2) depict NHZs positioned below the treatment group's median Business Environment Index, representing zones with limited capability in social capital acquisition. Conversely, Columns (3) and (4) capture the subset boasting an index surpassing this median, signifying NHZs adept in such an acquisition. Variable definitions are provided in Appendix 1. Coefficient estimates are provided with their respective t-statistics shown in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

5.2 Guidance mechanism

The second plausible mechanism under scrutiny is the guidance mechanism, focusing on the role of development zones in cultivating industry-specific clusters through strategic policy initiatives. At the heart of such zones lies the intent to entice companies from analogous industries (Delgado et al., 2014; Ellison et al., 2010). They benefit from preferential treatments, spanning tax reliefs, strategic land allocations, streamlined export procedures and financial incentives (Combes et al., 2012). This engineered concentration initiates a ‘Marshal-type’ agglomeration effect (Kline & Moretti, 2014; Rosenthal & Strange, 2004). As a result, these zones become hotbeds of rich labour markets, synergistic business interplay and knowledge diffusion, catalysing a sustained growth trajectory for the resident firms, as expounded by Combes et al. (2012), Wang (2013) and Guiso et al. (2021). It is then hypothesised that by cultivating such industry concentrations, GGF investments could potentially enhance the development pace of target industries within NHZs.

To assess this hypothesis, the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Index (IRIEC), developed by Peking University, is employed to gauge the extent of clustering within NHZs' target industries. Given the high-tech orientation of the majority of these target industries, the index aptly captures the concentration gradient of high-tech sectors within the NHZs.4

Again, a group regression test is utilised to explore the link between GGF investments and the development of target industries alongside the promotion of their agglomeration within NHZs. The treatment sample is classified into two distinct segments: one characterised by a pronounced density of high-tech industries (reflected by innovation and entrepreneurship index values exceeding the treatment group's average) and its counterpart manifesting a relatively dilute high-tech industrial landscape (indexed below the mean). We posit that NHZs characterised by a dense aggregation of high-tech enterprises would manifest a heightened responsiveness to GGF investments, leading to accelerated growth in their target industries.

Table 5 sheds light on the empirical findings. While columns (1) and (2) cater to the subgroup with an IRIEC below the treatment group's mean, columns (3) and (4) provide insights into the complementary subgroup with an IRIEC exceeding the mean. The coefficient for Treat × Post in column (2) is statistically insignificant, suggesting a muted impact of GGF investments on NHZs marked by subpar high-tech industry concentration, consistent with our conjecture. Contrarily, column (4) shows a statistically positive correlation with Treat × Post, significant at the 1% threshold. That is, following the infusion of GGF funds, there is a surge in the electricity consumption metric by 9.6% for NHZs in this bracket, relative to their counterparts in the control segment. These results affirm that a higher degree of high-tech industry clustering leads to a more pronounced impact of GGF investments on the development of target industries within NHZs, thereby corroborating the initial conjecture.

| Variables | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) | Ln(Ele) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treat*Post | −0.017 | −0.014 | 0.101*** | 0.096*** |

| (−0.65) | (−0.51) | (4.68) | (4.36) | |

| GDP1 | −0.347 | −0.292 | ||

| (−0.50) | (−0.40) | |||

| GDP2 | −0.116 | −0.187 | ||

| (−0.18) | (−0.27) | |||

| GDP3 | −0.009 | −0.144 | ||

| (−0.01) | (−0.20) | |||

| Fdi | −0.013 | 0.412 | ||

| (−0.05) | (1.48) | |||

| Fisav | −0.007 | −0.003 | ||

| (−0.53) | (−0.26) | |||

| Govexp | −0.234*** | −0.259*** | ||

| (−3.01) | (−3.27) | |||

| Infor | 3.528*** | (1.51) | ||

| (2.95) | (2.31) | |||

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1404 | 1404 | 1495 | 1495 |

| Adjust_R2 | 0.478 | 0.482 | 0.487 | 0.490 |

- Note: This table delineates the empirical results on the interplay between GGF investments and the industrial agglomeration within NHZs. Columns (1) and (2) depict NHZs with an IRIEC falling below the treatment group's average, signalling lesser industrial concentration. In contrast, columns (3) and (4) encapsulate NHZs outstripping this average, reflecting a more robust high-tech industry presence. Variable definitions are provided in Appendix 1. Coefficient estimates are provided with their respective t-statistics shown in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

6 CONCLUSION

In an era characterised by dynamic global economic shifts, understanding the role of state-led initiatives in shaping the technological and industrial landscape becomes important. This study delved deep into the symbiotic relationship between government-guided funds and their pronounced impact on the target industries located within NHZs. Through a difference-in-differences approach, we extrapolate the nuanced effects of staggered GGF investments, illuminating the transformative capacity of such funds in catalysing industrial advancements within China's NHZs. Specifically, our findings show that NHZs receiving GGF allocations experienced a notable increase in industrial activity, with a 5.5% rise compared to those without such funding.

At the heart of our findings lie two mechanisms that lend credence to the observed empirical outcomes: the pivotal mobilisation of social capital and the orchestrated guidance mechanism. Our findings reveal that state-led financial initiatives, embodied by GGFs, not only bridge critical financing gaps but also serve as potent catalysts, channelling private venture capital towards high-tech start-ups and SMEs. This mobilisation of social capital is particularly pronounced in NHZs endowed with robust business ecosystems, as quantified by the Business Environment Index.

The guidance mechanism brings to the fore the strategic role of NHZs in fostering high-tech industrial clusters. These artificial conglomerations, underpinned by favourable policies, set in motion a virtuous cycle of knowledge dissemination, business synergy and a conducive labour market. We show that NHZs characterised by heightened high-tech clustering stand to benefit more substantially from GGF interventions. Theoretically, our research advances the understanding of how state-led financial mechanisms and place-based policies synergistically foster industrial development, offering a model that can be applied to other economic contexts.

In summary, this study accentuates the multifaceted repercussions of government-induced financial strategies within the technological industry. While GGF investments stimulate growth and development, the magnified effects observed in NHZs with favourable business environments and pronounced high-tech concentrations signal the importance of strategic locational choices and policy design. As governments globally grapple with the challenge of fostering innovation and ensuring sustained industry growth, the findings from our research offer timely policy implications and set the stage for future scholarly exploration in this domain. Looking forward, there are several avenues for future research. First, studying the impacts of GGFs at different administrative levels, such as provincial or municipal GGFs, could provide a more nuanced understanding of their effectiveness. Second, exploring the long-term impacts of GGFs on economic resilience and sustainability would be valuable. Lastly, investigating the role of specific policy instruments and their interaction with GGFs can offer a deeper understanding of optimal policy design to foster innovation-driven growth.

APPENDIX 1

Variable definitions

The Appendix provides a detailed exposition of the variables employed in our study. For each variable, its definition and source of extraction are systematically delineated.

| Variables | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Ln(Ele)i,t | Natural logarithm of the electricity consumption data of a national high-tech zone i in year t | Statistics bureaus of provinces and cities |

| NLi,t | The Nighttime Light data of a national high-tech zone i in year t | CNRDS |

| Independent variable | ||

| The dummy variable of government-guided fund investment in the development zone | PEdata | |

| Control variables | ||

| GDP1i,t | The proportion of GDP accounted for by the primary industry in the cities where the national high-tech zone is located | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| GDP2i,t | The proportion of GDP accounted for by the secondary industry in the cities | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| GDP3i,t | The proportion of GDP accounted for by the tertiary industry in the cities | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| Govexpi,t | The proportion of GDP accounted for by local government budgetary expenditure | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| Fdii,t | The proportion of GDP accounted for by actual utilisation of foreign direct investment in the city | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| Fisavi,t | The share of year-end deposits of financial institutions in GDP | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| Infori,t | The share of total postal and telecommunication services in GDP | China City Statistical Yearbook |

APPENDIX 2

Placebo test results

This appendix provides detailed results from the robustness check conducted to validate our primary findings. The placebo test involved redefining our control and treatment groups and iterating the process 1000 times to ensure the reliability of the results. Panel A presents the summary statistics of the placebo test results. The average coefficient for the DiD variable is −0.009, which is significantly lower than the baseline regression of 0.055, indicating an absence of significant effects in the placebo trials. Panel B shows the distribution of the placebo test results, illustrating the effects obtained. The distribution aligns with the anticipated distribution under the scenario of no actual policy impact, thereby affirming the reliability of our primary research findings.

Panel A: Summary statistic of placebo test results

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | 1000 | −0.009 | 0.050 | −0.159 | 0.134 |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1 For more details, see the Ministry of Science and Technology website: http://www.most.gov.cn/gxjscykfq/ldjh/.

- 2 Data source: PEdata, https://www.pedata.cn.

- 3 The key advantage of staggered DID is that it allows for a more nuanced understanding of how the timing of GGFs can affect industrial development of NHZs.

- 4 The IRIEC's construction is based on a myriad of metrics sourced from the national industrial and commercial enterprise registration database from 1990 to 2020. It captures dimensions such as new enterprise formations, foreign capital attractions, venture capital influxes, patents granted and trademark registrations.