Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: a review and consolidation

Abstract

Interest in why firms conduct environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity is longstanding and increasing. Our understanding, however, remains fragmented with alternative accounts that seek to explain the relationship between ESG performance (ESGP) and corporate financial performance (CFP). This paper reviews alternative accounts for the relationship and finds that the weight of empirical evidence shows a positive, statistically significant but economically modest ESGP–CFP link, consistent with theoretical expectations. This economically modest relationship suggests ESG activity is unlikely to be primarily motivated by narrow measures of CFP. Further scholarship viewing ESG as part of overall firm activity would be constructive.

1 Introduction

Fundamentally, getting culture and conduct right is not merely a supervisory requirement. It is necessary for banks’ and banking’s economic and social sustainability. (G30, 2018)

Firms serve as economic actors – a production function in transforming inputs into outputs, and a direct distributive function in transfers to input providers. More broadly, the total costs and benefits of firm activity may not be entirely captured in observed market prices, generating increased interest in recent years regarding the role of firms (as individual organisations and collectively as an institution) in the communities in which they operate, responding to and reflecting economic conditions, as well as social, cultural and environmental considerations.

The rationale for ESG activity is not apparent in firm financial disclosures – their benefits and costs are not usually discernible in profit and loss statements, nor their accumulated value or decrement on balance sheets. Firms are under increasing pressure to ‘do good’ – to conduct themselves for more than financial gain – yet despite decades of academic interest, significant gaps remain in understanding how ESG is conceived, what motivates its undertaking, which stakeholders benefit, the form of those benefits, and where it might lead.

This article is concerned with advancing understanding of the motivations by profit-seeking firms to undertake voluntary ESG activities by consolidating and reviewing the meta-analytical evidence for the ESGP–CFP relationship. The concept of ‘firms’ here borrows from organisational economics – an economic actor which transforms inputs into outputs (a production function) which is managed (decisions on resource allocation) and has an owner or group of owners with an interest in the existence and successful operation of the firm (but is agnostic about the nature of its ownership structure) (Gibbons and Roberts, 2013). This last aspect enables the orientation of ESG activity, with firm activity affecting stakeholders beyond those with a direct interaction with it (e.g., owners, employees, customers and suppliers), and the firm being more than a narrow production function for the purposes of optimising the economic return to its owners. Secondly, the ESG activities of interest are those that are ‘voluntary’ and not compelled by law or regulation, with firm discretion between different courses of action where those decisions have consequences and are often made with imperfect information under uncertainty, and time and cognitive limitations.

For the purposes of this article, ESG is preferred to ‘corporate social responsibility’ (CSR), as it explicitly delineates its concerns (environmental, social and governance). The congruence between ESG and CSR is recognised, with Aguinis (2011, p. 855) defining CSR as ‘context-specific organisational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance’. There is significant scholarship marking the evolution of CSR and ESG and its associated concepts (see, e.g., Carroll, 1999, 2009; Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos, 2014; Sheehy, 2014); a detailed analysis of which is beyond the scope of this article.

The weight of evidence from the meta-analytical studies reviewed suggests a statistically significant positive ESGP–CFP relationship, consistent with theoretical expectations of a null to modestly positive link (Benabou and Tirole, 2010). The magnitude of the empirical relationship is economically modest (Cohen, 1988; Rosenthal and Rosnow, 1991), although small differences may matter in the global market for capital (Friede et al., 2015), with questions regarding whether the same measures of ESG performance are being measured (Margolis et al., 2007).

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the review methodology. Section 3 explores the main theoretical perspectives that seek to explain the ESGP–CFP association, illustrating the heterogeneity of scholarship in this field. Section 4 reviews the relevant meta-analytical evidence since 1980, and Section 5 concludes.

2 Review methodology

To examine the ESGP–CFP empirical relationship, information was extracted following a methodical literature search of electronic databases (Web of Science and University of Queensland database). A systematic keyword search was conducted for meta-analytical studies with ‘environmental, social and governance’ and ‘corporate social responsibility’ (and respective synonyms) together with ‘corporate performance’ or ‘corporate financial performance’ (and synonyms) published during the period January 1980 to February 2019. Incorporating studies from a recent review of ESGP–CFP meta-analytical studies (Busch and Friede, 2018), and additional studies identified by academic colleagues and ‘follow-on’ searches, a total of 69 studies were identified and screened for eligibility. To be included, studies must utilise ESGP and CFP metrics with sufficient statistical information to enable comparison between studies, including number of effect sizes and observations, and magnitude and significance of the findings. The studies were reviewed to ensure clear methods of sourcing the underlying articles and manipulation of the primary data, though it is recognised that this process is subjective (Borenstein et al., 2009). Event studies and outputs of probit models were excluded to enable effect sizes to be comparable across studies (Hang et al., 2019). Studies that were not eligible included meta-analyses that did not measure ESGP (e.g., Sainaghi et al., 2017) or CFP (e.g., Byron and Post, 2016; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al., 2016; Voegtlin and Greenwood, 2016), reviews that were conceptual in nature (e.g., Wood, 2010; Gautier and Pache, 2015), or related ESGP to disclosure rather than CFP (e.g., Khlif et al., 2015). Following this screening, a total of 21 studies were reviewed.

3 Alternative accounts

3.1 Context

Companies have long recognised that environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns and good business are not separable endeavours. In the nineteenth century, Macy’s, a progressive US department store, funded orphanages and social causes (Carroll, 2009). National Cash Register, one of the first companies to adopt a standardised sales process, recognised the link between worker welfare and productivity by providing lunch rooms and free clinics to employees (Carroll, 2009) as well as profit sharing (Visser, 2011). The nature of firms’ ESG activities mirror the concerns of the time, moving from early efforts based on philanthropy and social welfare, to notions of a firm’s responsibility as a trustee manager between stakeholders in the 1920s and 1930s. ESG expanded beyond firm financial performance in the 1960s, motivating debates in the 1970s and onward regarding the role of the firm in society as social and environmental causes emerged as important business issues (Carroll, 2009). Today, firms continue to see themselves as integral and dependent on the broader environment in which they currently operate, impacting future strategic options and how they may be prioritised (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016a,b).

Contemporary discourse in Australia enlivens debate on the role of business in society. The recently completed Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (Hayne, 2019) presents significant implications for industry policy and regulation (Gilligan, 2018) as well as company strategy, governance, culture and activities (Khoury et al., 2019). Beyond the financial services industry, finalisation of the updated ASX Corporate Governance Principles (ASX, 2019) engendered significant debate amongst top management and fund managers to reframe company governance and behaviours to reflect community expectations (Boyd, 2019).

3.2 Alternative accounts

There has been significant and increasing multi-disciplinary scholarship on ESGP and CFP, with a number of different loci of debates. Perhaps the most prominent discourse in this scholarship concerns who benefits from ESG, balancing the primacy of shareholder interests (namely that managers should maximise shareholder returns within legal constraints) (Friedman, 1970) and stakeholder theory (namely that firms are managed in the interests of those affected by its operations) (Sethi, 1979; Mitchell et al., 1997; Freeman 2002, 2011; Freeman et al., 2007). However, these positions may not be as diametrically opposed as an initial reading suggests. Friedman (1970, p. 126) recognised that business operated in a social context, that ‘society is a collection of individuals and of the various groups they voluntarily form’, whilst stakeholder theory has been integrated with the neo-classical economic approach of managers maximising the long-term value of the firm inclusive of stakeholder objectives (Jensen, 2001). Management-oriented literature suggests a middle ground wherein managers create ‘shared value’ between the firm’s shareholders and a broader set of stakeholders including employees, customers, suppliers and communities (Porter and van der Linde, 1995a; Porter and Kramer, 2011, 2006; Jones and Wright, 2018).

Secondly, the shareholder versus stakeholder beneficiary discourse references the broader notion of the role of business (individually and collectively) in society, drawing in orientations to the debate from a governance perspective. This orientation regarding the role of business in society to frame the ESGP–CFP relationship engenders considerations surrounding the boundaries of the firm (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2011), corporate citizenship and firm behaviour in society (Garriga and Mele, 2004; Scherer and Palazzo, 2007), and the intersection of business and moral and political philosophy frameworks, such as Kantian, virtue ethics, social contract theory and deliberative democracy (Hsieh, 2017).

A governance perspective on the organisational (individual firm-level activity) and institutional (business in society) nexus has implications for how firms are managed, for whose benefit, and how conflicts are addressed. Governance at an organisational level is concerned with the principal-agent problem arising from the separation of management and capital, and ‘deals with the ways in which suppliers of finance assure themselves of getting a return on their investment’ (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997, p. 737) with a presumptive orientation towards shareholder primacy. This may be too narrow, as firm activity affects a number of stakeholders (including employees, customers, suppliers and communities) and therefore corporate governance could be defined as ‘the design of institutions that induce or force management to internalise the welfare of stakeholders … with the case for shareholder value resting on the economics of incentives and control’ (Tirole, 2001, p. 4). However, an overly broad stakeholder approach to corporate governance may encompass too many potential externalities to be workable and may be indistinguishable from health, safety or environmental regulation (Hermalin, 2013).

Whilst corporate governance is typically an organisational-level concern (as arrangements that allocate control and decision-rights within firms as well as the checks and balances on their exercise), the link to institutional outcomes has been made by scholars and decision-makers. For example, in the context of the global financial crisis, Allen et al.(2008, p. v) noted that ‘corporate governance problems are the root of macroscopic failures recently witnessed in financial markets’. In the Australian context, the Royal Commission into the Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry has made material adverse findings of conduct by a large number of firms towards their customers (Hayne, 2019), with significant implications for the quality of board oversight and management incentives, firm culture and industry regulation (Khoury et al., 2019).

An economics approach to the ESGP–CFP relationship provides a third orientation. As indicated by the shareholder versus stakeholder primacy discourse and broader notions of corporate governance, the broader consequences of firm activity draw in considerations of externalities and market failures. The argument is that the costs and benefits of private goods provision is not fully captured in market prices, for example, that natural capital assets are scarce and have value beyond accounting measures that affect human well-being (Mayer, 2019). The scientific evidence confirming human activity as a significant, negative and growing impact on our climate (IPCC, 2014) with a number of planetary boundaries for human development breached or under threat (Rockstrom et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015) is suggestive of market failure on a grand scale – the unpaid social cost of fossil fuel (after firm profits and prevailing taxes and revenues from carbon pricing) could average US$5.8 trillion over the period 1995–2013 (Linnenluecke et al., 2018). A stakeholder approach could theoretically be stretched to encompass the scope of firm governance (with firms collectively regarded as an institution, essentially as private enterprise) to balance the rights and responsibilities of economic actors to society at large, in effect with economic actors as trustees exercising judgement on behalf of others (Mayer, 2019), although it is unclear what practical arrangements would be required. A macro-economic orientation provides the broadest perspective to frame the ESGP–CFP relationship, recognising the corporation as a ‘remarkable institution that has created more prosperity and misery than we could have imagined’ (Mayer, 2013, p. 1). The question of sustainable development, namely whether economic growth is compatible with sustainable human well-being over time, requires an accounting of tangible and intangible assets and how they may be affected by productive activity. This may require an assessment of shadow prices (referencing externalities) that may deviate from observed market prices (Arrow et al., 2012).

An issues-based organisational performance approach to the ESGP–CFP relationship provides a fourth, perhaps more practically oriented examination of the motivations and outcomes of that relationship. Firms undertake ESG activity for instrumental reasons to motivate an outcome (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012), adopting a business-case approach where the benefit of the activity exceeds its costs (Kurucz et al., 2009; Carroll and Shabana, 2010). Benabou and Tirole (2010) provide three theoretical foundations that link the concerns of economic actors to a firm’s ESG activity: (1) win-win, where ESG is undertaken to maximise long-term firm value; (2) delegated, where ESG is an expression of social values by the firm’s stakeholders; and (3) insider-initiated, where ESG reflects top managements’ values and personal interests. The overall ESGP–CFP relationship is likely to be null to slightly positive (Benabou and Tirole, 2010).

An issues-based approach encompasses a number of strands. A taxonomy may be to arrange scholarship into ESG performance measures, CFP measures and disclosure. For example, in regard to ESG performance measures, studies have examined environmental performance measures (Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012; Albertini, 2013) or more specifically around environmental processes or outcomes (Endrikat et al., 2014), placed social performance as the phenomenon of interest (Jones and Wright, 2018), or centred on governance attributes (Post and Byron, 2014). Many studies examine a range of CFP measures (operational, accounting and market) for their association with the ESGP measure of interest (e.g., all the meta-analytical studies reviewed in this article include multiple CFP measures). From a disclosure perspective, the literature shows evidence of ESGP as reducing informational asymmetry between the firm and key stakeholders (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Aghion and Holden, 2011; Nguyen et al., 2018), as well as being directed to a more specific outcome, for example ESG disclosure and dividend payments (Cheung et al., 2018; Ni and Zhang, 2019). Although ESG disclosures may be a proxy for actual ESGP (Beck et al., 2018), pressure from stakeholder groups in and outside the firm shape financial decisions, with firm decision-making taking into account how disclosure may favourably address stakeholder concerns (Coleman et al., 2010), raising risks of green- or white-washing. In addition to examination of the association between disclosure and performance, there remains the underlying issue of causality and its direction – although most studies focus on precedent-ESGP and consequent-CFP, there is evidence that the association may equally flow from CFP to ESGP (Margolis et al., 2007), supporting a resources-based approach to ESG (Barney, 1991; Barney et al., 2011).

In summary, there are a number of alternative but inter-related approaches to examining the ESGP–CFP relationship, concerning the beneficiaries of ESG (shareholder versus stakeholder), the allocation of control rights and decision-making (governance), firm activity in the context of broad notions of productive and allocative efficiency (economics), and a more issues-based organisational performance orientation. These alternative accounts are primarily motivated ‘to provide a framework for evaluating the conduct and policies of business enterprises in relation to society and for guiding managerial decision-making’ (Hsieh, 2017, p. 294) with the objective of creating some measure of wealth (Grewatsch and Kleindienst, 2017). However, despite significant scholarship, ‘research has not produced a solution, but rather isolated strands of partial insight about an unseen larger picture’ (Galbreath and Shum, 2012, p. 214). This may not be surprising – within the research on the association between corporate governance and firm performance (one strand of the broader ESGP–CFP relationship), much of the academic literature lacks formal theory (Hermalin and Weisbach, 2003) with little consensus on findings (Schultz et al., 2010), perhaps suggestive of endogeneity issues in the field (Gippel et al., 2015).

3.3 Observations

Despite longstanding, substantial and increasing academic interest in why firms might conduct ESG (reflecting its significance to practitioners, government and communities more broadly), the field remains fragmented (Garriga and Mele, 2004; Crane et al., 2009; Kurucz et al., 2009; Melé, 2009; Peloza, 2009; Carroll and Shabana, 2010; Peloza and Shang, 2010; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Mattingly, 2015). Perhaps unsurprisingly in a maturing field and dictated by the availability of observable empirical data, much of the research focuses on observable end outcomes of ESGP and CFP, with comparatively little work that conceives ESGP as part of overall firm activity.

A number of observations may be collated from the ESG literature which collectively calls for a more holistic and multi-disciplinary approach to ESG research. Firstly, to rebalance research away from further empirical study of the ESGP–CFP relationship (Wood, 2010; López-Arceiz et al., 2018; Hang et al., 2019), reflecting longstanding concerns that work is being focused on outcomes without sufficiently understanding motivators and causality in addition to ESG’s place in overall firm strategy (Ullmann, 1985; Grewatsch and Kleindienst, 2017). Secondly, to integrate conceptual streams to understand why firms undertake ESG activities (van Beurden and Gössling, 2008; Wood, 2010; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Gautier and Pache, 2015; Hou et al., 2015; Mattingly, 2015; Van der Byl and Slawinski, 2015; Hang et al., 2019), perhaps reflecting a need to better understand motivators at institutional, organisational and individual levels. Thirdly, to better understand company processes by which ESG actions lead to particular outcomes (Wood, 2010; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Gautier and Pache, 2015; Hang et al., 2019), perhaps reflecting a need to better understand the levers by which motivators are transformed into outcomes for the firm. Fourthly, to better understand the impact of ESG activity on the firm’s stakeholders (Peloza and Shang, 2010; Gautier and Pache, 2015), perhaps reflecting a need to measure the outcomes for whom ESG activity is in part undertaken. Finally, to better understand individual and psychological processes that inform ESG activity (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Revelli and Viviani, 2015; Ghobadian et al., 2015), perhaps reflecting non-financial factors that inform how ESG is perceived, framed and actioned. The calls within the ESG literature reflect similar encouragement within the broader finance literature, together with emerging trends in published research focusing on issues central to ESG considerations including environmental finance, and equity and diversity (Linnenluecke et al., 2017, 2016).

Re-orienting the study of ESG towards a more holistic and multi-disciplinary perspective may contribute to the development of a middle range theory (Merton, 1949) for why firms conduct ESG, and to practical understandings for firm management and regulation. This has implications regarding the understanding of the full scope of activities firms might undertake in their own interests, the structure of appropriate governance and incentives to align the interests of economic agents contributing to firm production, and the identification, assessment and regulation of market failures as a result of firm activity. That is, the study of why firms may conduct ESG activity sits at the intersection of two central pillars for economic activity – Adam Smith’s invisible hand with the self-interested action of economic agents focused on productive efficiency, and government intervention to redistribute wealth and income (as market outcomes may be inconsistent with social values) and address market failures (Benabou and Tirole, 2010).

3.4 Research metrics over 30 years

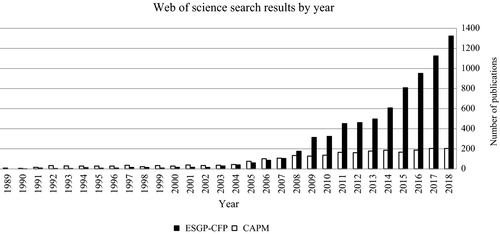

These various approaches underscore the substantial and increasing scholarship to advance theoretical and empirical understanding of the ESGP–CFP relationship. Over the last 30 years, a Web of Science search returns 7,485 publications in 135 categories with search terms comprising ‘environmental social governance’ or ‘corporate social responsibility’, and ‘corporate performance’ or ‘corporate financial performance’ (see Figures 1 and 2). As a comparison, a Web of Science search for ‘capital asset pricing model’ returns 2,636 publications over the same period.

The fragmentary nature of scholarship perhaps reflects ESG meaning different things to different stakeholders, depending on their concerns (Carroll, 2009, 1999; Crane et al., 2009; Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos, 2014; Sheehy, 2014; Lu and Taylor, 2016). Even where there is broad agreement, for example in relation to the overwhelming scientific evidence on anthropogenic climate change, there remains material disagreement at institutional, organisational and individual level about identifying, prioritising and resourcing responses. This debate appears to have a range of reasons – for example in the consideration of climate change, this may involve different values (to ascribe to activities, assets, sources and constructs), different beliefs (about our relationship to others, nature and deities), different evaluation of risks, different understandings of development, different and conflicting public messages about climate change, and different ways we govern ourselves and exercise power (Hulme, 2009).

The lack of an agreed theoretical framework to explain and predict firm-level ESG activity could reflect the dissonance between normative orientations (that the ESGP–CFP relationship should be positive and meaningful statistically as well socio-economically) and the weight of empirical evidence to date, which suggests a positive and statistically significant but economically modest relationship (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Margolis et al., 2007; Wood, 2010; Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012; Albertini, 2013; Endrikat et al., 2014; Hou et al., 2015; Lu and Taylor, 2016). Other studies illustrate a difficulty in being conclusive on the relationship, indicating that much depends on what ESGP and CFP measures are used (Ullmann, 1985; Allouche and Laroche, 2005; Margolis et al., 2007; Horváthová, 2010; Post and Byron, 2014). Institutional logics have been found to affect the size and strength of the relationship (Orlitzky, 2011), as well as to make no difference (Busch and Friede, 2018).

4 Findings from meta-analytical studies

4.1 Theoretical expectations

The literature suggests a range of theoretical frameworks that indicate that the ESGP–CFP relationship could be null, positive or negative. From an economic perspective, Benabou and Tirole (2010) provide three collectively comprehensive models – win-win, delegated and insider-initiated. The win-win model’s focus on minimising long-term contingent liabilities and strengthening market position resonates in the strategy and management literature where ESG activity differentiates a firm’s competitive position (Porter and van der Linde, 1995b) or is undertaken under a positive business case (Kurucz et al., 2009; Carroll and Shabana, 2010), and suggests a positive ESGP–CFP relationship (Benabou and Tirole, 2010). The delegated model resonates with stakeholder theory from the ESG literature (Sethi, 1979; Donaldson and Preston, 1995; Mitchell et al., 1997), with firm activity reflecting the values and decision-making by the firm’s customers, employees, capital providers and broader community, which mirrors legitimacy theory where business operations are validated by society (Davis, 1973). As a reflection of stakeholder demands (McWilliams and Siegel, 2010), this model also suggests a positive ESGP–CFP relationship (Benabou and Tirole, 2010). The insider-initiated model, with ESG activity motivated by the personal interests of top management, is unlikely to result in a positive ESGP–CFP relationship due to corporate governance and agency concerns (Benabou and Tirole, 2010; Ferrell et al., 2016). As ESG activity is often motivated by a range of factors (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012), many of which may not be observable, the overall ESGP–CFP relationship is likely to be null to slightly positive (Benabou and Tirole, 2010).

4.2 Descriptive statistics

The 21 meta-analytical studies on the ESGP–CFP relationship reviewed in this paper are summarised in Table 1. Effect sizes and observations in the underlying primary studies cover substantial data points. Thirteen studies are meta-analyses of the general ESGP literature, covering all industries and a range of ESGP and CFP measures, with one study explicitly focused on East Asian firms (Hou et al., 2015). Five studies specify environmental ESGP measures, with two focused on social and governance ESGP measures (both relating to women in top management positions). The wide range of ESGP measures in these studies (which include overall ESGP measures such as indices, process-outcome-disclosure measures, qualitative and quantitative measures) ‘raises questions about whether these all capture a single underlying construct’ (Margolis et al., 2007, p. 16). CFP measures reported in the underlying primary studies capture operational, accounting or market performance measures. The most commonly used meta-analytical methods are one of two types, namely Hedges and Olkin’s (1985) formulation or Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) version.

| Author(s), Date | Primary studies | Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect sizes (k) | Observations (n) | ESGP | CFP | ||

| 1 | Hang et al.(2019) | 893 | 757,154 | Environmental | All |

| 2 | Hoobler et al.(2018) | 78 | 117,639 | Social and Governance | All |

| 3 | Busch and Friede (2018) | 4,507 | 992,239 | All | All |

| 4 | López-Arceiz et al. (2018) | 678 | 1,368,044 | All | All |

| 5 | Rost and Ehrmann (2017) | 162 | 2,663 | All | All |

| 6 | Wang et al.(2016) | 119 | 150,706 | All | All |

| 7 | Lu and Taylor (2016) | 198 | 31,514 | All | All |

| 8 | Revelli and Viviani (2015) | 190 | 89,496 | All | Mkt |

| 9 | Hou et al.(2015) | 87 | 31,773 | All | All |

| 10 | Liu et al. (2015) | 10 | 2,525 | Environmental | All |

| 11 | Miras-Rodriguez et al. (2015) | 103 | 31,878 | All | All |

| 12 | Post and Byron (2014) | 131 | 90,070 | Social and Governance | All |

| 13 | Endrikat et al.(2014) | 245 | 201,511 | Environmental | All |

| 14 | Albertini (2013) | 205 | 62,943 | Environmental | All |

| 15 | Dixon-Fowler et al.(2012) | 71 | 22,869 | Environmental | All |

| 16 | Orlitzky (2011) | 388 | 33,878 | All | All |

| 17 | Vishwanathan (2010) | 189 | 611 | All | All |

| 18 | Margolis et al.(2007) | 192 | 27,848 | All | All |

| 19 | Allouche and Laroche (2005) | 373 | 57,409 | All | All |

| 20 | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | 388 | 33,878 | All | All |

| 21 | Orlitzky (2011) | 0 | 6,889 | All | All |

- Summary of 21 studies reviewed in this paper, based on systematic key word search of electronic databases conducted for meta-analytical studies with ‘environmental, social and governance’ and ‘corporate social responsibility’ (and respective synonyms) together with ‘corporate performance’ or ‘corporate financial performance’ (and synonyms) published during the period January 1980 to February 2019, augmented by referred and ‘follow on’ searches. Busch and Friede (2018) incorporates the same studies as Friede et al.(2015). ‘Effect Sizes (k)’ captures the number of standardised mean difference measures in the study, with ‘Observations (n)’ the number of observations in the study.

In terms of CFP outcomes, there are more studies reporting on accounting and market measures than operational measures, perhaps reflecting data availability (as firm financial performance and market data is often more accessible than operational data). Table 2 organises the meta-analytical studies by ESGP and CFP measures.

| ESGP measure | CFP measure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Operational | Accounting | Market | ||

| All | 1 | Busch and Friede (2018) | Busch and Friede (2018) | Busch and Friede (2018) | Busch and Friede (2018) |

| 2 | López-Arceiz et al. (2018) | Hou et al.(2015) | López-Arceiz et al. (2018) | López-Arceiz et al. (2018) | |

| 3 | Rost and Ehrmann (2017) | Wang et al.(2016) | Wang et al.(2016) | ||

| 4 | Wang et al.(2016) | Lu and Taylor, 2016 | Lu and Taylor (2016) | ||

| 5 | Lu and Taylor (2016) | Hou et al.(2015) | Revelli and Viviani (2015) | ||

| 6 | Hou et al.(2015) | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | Hou et al.(2015) | ||

| 7 | Miras-Rodriguez et al. (2015) | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | |||

| 8 | Orlitzky (2011) | ||||

| 9 | Vishwanathan (2010) | ||||

| 10 | Margolis et al.(2007) | ||||

| 11 | Allouche and Laroche (2005) | ||||

| 12 | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | ||||

| 13 | Orlitzky (2011) | ||||

| Environmental | 1 | Hang et al.(2019) | Hou et al.(2015) | Endrikat et al.(2014) | Endrikat et al.(2014) |

| 2 | Busch and Friede (2018) | Margolis et al.(2007) | Albertini (2013) | Albertini (2013) | |

| 3 | Lu and Taylor (2016) | Dixon-Fowler et al.(2012) | Dixon-Fowler et al.(2012) | ||

| 4 | Liu et al. (2015) | ||||

| 5 | Endrikat et al.(2014) | ||||

| 6 | Albertini (2013) | ||||

| 7 | Dixon-Fowler et al.(2012) | ||||

| 8 | Margolis et al.(2007) | ||||

| 9 | Allouche and Laroche (2005) | ||||

| 10 | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | ||||

| Social or Governance | 1 | Hoobler et al.(2018) | Hou et al.(2015) | Hoobler et al.(2018) | Hoobler et al.(2018) |

| 2 | Busch and Friede (2018) | Post and Byron (2014) | Post and Byron (2014) | ||

| 3 | Lu and Taylor (2016) | ||||

| 4 | Post and Byron (2014) | ||||

| 5 | Margolis et al.(2007) | ||||

| 6 | Allouche and Laroche (2005) | ||||

| 7 | Orlitzky et al.(2003) | ||||

- This table organises the 21 studies reviewed in this paper by ESGP measure (left-hand column) and CFP measure (headings at the top of the right-hand columns). Articles may be referenced multiple times in the table, as they may incorporate multiple ESGP and CFP measures.

4.3 Summary of findings

The weight of empirical evidence from the meta-analytical studies reviewed show that the ESGP–CFP relationship is positive and statistically significant but economically modest. The studies show the strongest relationship between ESGP measures and operational CFP measures, with declining correlation coefficients to accounting and market CFP measures. This perhaps reflects increasing variables that affect CFP outcomes – operational CFP measures may more directly relate to specific ESG activity, accounting CFP likely aggregates a wider bundle of firm activity than ESG, and market measures may be further confounded by an assessment of firm current and future earnings by shareholders relative to other investment opportunities. Table 3 sets out the median ESGP–CFP correlation from eligible studies organised by ESGP and CFP measures. The overall median correlation of 0.1430 for the ESGP–CFP relationship suggests that ESGP as the unit of analysis captures around 2.0 percent of the explained variance.

| ESGP measure | CFP measure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Operational | Accounting | Market | |

| All | 0.1430 | 0.2980 | 0.1410 | 0.0800 |

| Environmental | 0.0960 | 0.3015 | 0.0680 | 0.0545 |

| Social or Governance | 0.1270 | 0.0390 | 0.0335 | 0.0320 |

- This table shows the median of ESGP-CFP mean weighted correlations from the studies reviewed in this paper, organised by ESGP (left-hand column) and CFP (headings at the top of right-hand columns) measures.

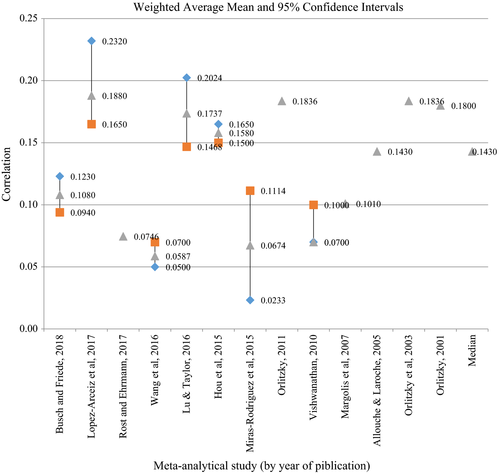

All 13 meta-analytical studies that review primary research on the overall ESGP–CFP relationship identify a positive, statistically significant relationship between ESGP and CFP. Seven studies provide confidence intervals at the 95 percent level. Figure 3 visualises the overall ESGP–CFP relationship, with a median 0.1430 mean weighted correlation coefficient from studies that find a statistically significant relationship. The correlation coefficients from these studies range from 0.0587 to 0.1880, within the ‘small’ range of coefficient effects (Cohen, 1988; Rosenthal and Rosnow, 1991), consistent with observations in some of the studies (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Lu and Taylor, 2016). The magnitude of the ESGP–CFP relationship has been stable over time, although the dispersion of correlations published in a given year has increased (Friede et al., 2015).

The economically modest ESGP–CFP relationship is further confounded by a lack of consensus in the studies concerning publication bias (the ‘file drawer’ problem; Rosenthal, 1979), whether the relationship is bi-directional and institutional logics. Hang et al.(2019) and Busch and Friede (2018) found no publication bias, whilst Rost and Ehrmann (2017) found a positive publication bias associated with later publications, higher impact journals, and studies testing no theory or applying weak methods. Although Endrikat et al.(2014) found some evidence of a bi-directional ESGP–CFP link, Wang et al.(2016) found no support for a statistically significant positive CFP–ESGP relationship. Orlitzky (2011) found that institutional logics affected the strength of the ESGP–CFP relationship, with lower mean weighted correlations published in economic, finance and accounting journals compared to social issues in management and business ethics journals or general management journals, suggesting that ‘conceptualisation of social science as a value-free process of (dis)confirming theoretical explanations is rather naïve’ (Orlitzky, 2011, p. 412); however, Busch and Friede (2018) found no difference. The different findings in the literature raises questions on whether the studies capture the same ESGP and CFP measures (Margolis et al., 2007; Revelli and Viviani, 2015; Lu and Taylor, 2016).

The meta-analytical studies demonstrate that factors other than ESGP are likely more significant determinants to the ESGP–CFP relationship, motivating the interest to understand the motivators and processes of ESG’s place in firm decision-making. This should not be interpreted as diminishing the importance of ESG, given the importance placed on non-financial performance by top management on firm existence and performance (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016a,b). Further, small effect sizes are common in the social sciences and may be relevant in global securities markets (Friede et al., 2015).

4.4 Environmental, social, and governance measures and CFP

Analysis of environmental and social or governance measures of ESGP and CFP suggests two broad observations. Firstly, the studies show a broadly similar strength of relationship between environmental ESGP–CFP and social or governance ESGP–CFP, with median weighted mean correlation coefficients of 0.0960 and 0.1270, respectively (see Table 3). Looking at the five studies with both environmental ESGP–CFP and social or governance ESGP–CFP meta-analyses within the same study, three studies identify a stronger social or governance ESGP–CFP relationship (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Margolis et al., 2007; Busch and Friede, 2018), one finds a stronger environmental ESGP–CFP relationship (Lu and Taylor, 2016), and one finds similar outcomes (Allouche and Laroche, 2005) (see Table 4). None of the studies provided confidence intervals for these correlation coefficients in regards to these measures.

| Study | Environmental ESGP to all CFP | Social or Governance ESGP to all CFP |

|---|---|---|

| Busch and Friede (2018) | 0.1060 | 0.1270 |

| Lu and Taylor (2016) | 0.2035 | 0.0689 |

| Margolis et al.(2007) | 0.0900 | 0.2200 |

| Allouche and Laroche (2005) | 0.1450 | 0.1430 |

| Orlitzky et al.(2003) | 0.0562 | 0.2301 |

| Median | 0.1060 | 0.1430 |

- This table shows the mean weighted correlations from the studies reviewed in this paper that report environmental ESGP to all forms of CFP, and social or governance ESGP to all forms of CFP. Not all studies in this paper included these measures.

Secondly, the relationship between environmental ESGP and operational CFP measures is substantially higher (0.3015 correlation coefficient) than for accounting (0.0680) or market (0.0545) CFP measures (see Table 3). This is not the case for social or governance ESGP and operational, accounting or market CFP measures (all in the 0.03–0.04 range). One study examines both the environmental and social governance ESGP against operational outcomes, reporting a 0.459 mean weighted correlation for environmental ESGP with operational measures, substantially higher than the 0.055 coefficient for social ESGP with operational measures (Hou et al., 2015). This poses a number of questions. Are environmental performance measures easier to define, execute and measure than social or governance measures, especially in operational terms? For example, comparing energy efficiency, waste management and resource use initiatives versus community engagement, firm reputation or diversity? Why do environmental performance measures (such as carbon reduction initiatives) have a stronger relationship than social or governance performance measures (such as board or management diversity, community engagement and philanthropy) to CFP? Are environmental performance measures more easily translatable to financial outcomes? More broadly, is the strength of the correlation between ESGP and CFP the only way to determine the importance of the ESGP measure being reviewed?

4.5 Accounting and market outcomes

Ten studies report on the strength of the relationship between various ESGP measures and accounting and market-based measures of CFP. The weight of evidence across these studies shows a higher correlation between various ESGP measures and accounting CFP than market-based CFP, with two studies reporting a stronger relationship to market-based measures (Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012; Hoobler et al., 2018), seven studies finding a stronger relationship to accounting measures (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Albertini, 2013; Post and Byron, 2014; Lu and Taylor, 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Busch and Friede, 2018; López-Arceiz et al., 2018), and one reporting a strong relationship with accounting measures for process environmental ESGP but a stronger relationship for outcome environmental ESGP with market measures (Endrikat et al., 2014) (see Table 5). Only the results from three of these studies (Albertini, 2013; Post and Byron, 2014; López-Arceiz et al., 2018) had no overlap of the confidence intervals for these measures, with each of these studies finding a stronger association between ESGP measures and accounting CFP. The other studies either did not provide confidence intervals or there was an overlap in the confidence intervals for these measures.

| Study | ESGP measure | Accounting CFP | Market CFP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Busch and Friede (2018) | All | 0.1150 | 0.0800 |

| López-Arceiz et al.(2018) | All | 0.1670 | 0.0820 |

| Wang et al.(2016) | All | 0.0489 | 0.0378 |

| Lu and Taylor (2016) | All | 0.1929 | 0.1520 |

| Orlitzky et al.(2003) | All | 0.2070 | 0.0733 |

| Endrikat et al.(2014) | Environmental processes | 0.0850 | 0.0070 |

| Environmental outcomes | 0.0510 | 0.0960 | |

| Albertini (2013) | Environmental | 0.2400 | 0.0300 |

| Dixon-Fowler et al.(2012) | Environmental | 0.0480 | 0.0790 |

| Hoobler et al.(2018) | Social or Governance | 0.0200 | 0.0500 |

| Post and Byron (2014) | Social or Governance | 0.0470 | 0.0140 |

| Median | 0.0850 | 0.0733 | |

| Average | 0.1111 | 0.0637 |

- This table shows the mean weighted correlations from the studies reviewed in this paper that report various ESGP measures with their respective accounting and market-based CFP. Not all studies in this paper included these measures.

Both the accounting and market-based financial performance measures referenced in the studies are measured at a greater level of aggregation (e.g., firm-wide) than the specific ESG activity measured, therefore likely measuring more than the outcomes of that activity. Accounting measures typically used in each of the studies include return on assets, return on equity, return on sales, earnings per share and return on investment (e.g., Albertini, 2013; Endrikat et al., 2014; Lu and Taylor, 2016), although other financial measures are also used (e.g., market shares in Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012). Market performance measures referenced in the studies include share price performance, Tobin’s Q and price–earnings ratios. Taken as a whole, the meta-analytical studies suggest that there is a more direct link between ESGP outcomes and accounting measures, with the ESGP–market CFP relationship further confounded by industry and macro-economic variables.

4.6 Moderator and mediator analysis

The meta-analyses reviewed in this paper include observations on the moderators (conditions under which ESGP is related to CFP) and mediators (variables that explain underlying processes between ESGP and CFP) of the ESGP–CFP relationship. Given the association is economically modest, it appears that moderator analysis of the ESGP–CFP relationship is continuing to mature, with little knowledge of the underlying processes between predictors of ESG activity and its outcomes (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012).

Traditional firm and industry characteristics have been found to be statistically significant moderators of the ESGP–CFP relationship, although the evidence remains inconclusive. In terms of firm size, two studies found that smaller firms tended to display a stronger ESGP–CFP relationship (Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012; Hou et al., 2015) perhaps due in part to the signalling role that ESGP plays, which becomes diluted as firm size increases (Hou et al., 2015). However, Orlitzky (2011) found that controlling for firm size does not confound the ESGP–CFP relationship, suggesting that other (mediating) factors such as strategic planning or organisational learning may be better predictors. The evidence regarding the influence of firm location on the relationship is mixed, with studies finding that non-US firms have a stronger ESGP–CFP relationship than US firms (Albertini, 2013; Friede et al., 2015; Lu and Taylor, 2016), whilst others suggest that US firms benefit from ESGP but not non-US firms (Dixon-Fowler et al., 2012). The evidence on the influence of firm ownership is similarly mixed, with Hou et al(2015) showing a stronger link for privately owned firms than public firms, whilst Dixon-Fowler (2012) finding no difference. Industry classification does not seem to be a statistically significant moderator of the ESGP–CFP relationship (Albertini, 2013; Hou et al., 2015).

These studies also considered the influence of more dynamic organisational processes that are statistically significant mediators of the ESGP–CFP relationship. At an organisational level, firms that have the ability to invest in ESGP may develop organisational resources and capabilities that can lead to competitive advantage, which in turn supports the validity of a resource-based view of the firm for ESGP (Albertini, 2013). Strategic integration of ESGP into firm strategy can help moderate the ESGP–CFP relationship – closer integration of ESGP into the firm’s overall strategy is indicative of a stronger ESGP–CFP relationship (Albertini, 2013; Post and Byron, 2014). Stakeholder engagement as part of ESGP is indicative of a stronger ESGP–CFP relationship – good ESGP helps to build a positive reputation with external stakeholders, with reputation indices within ESGP measures more highly correlated to CFP than other indicators of ESGP (Orlitzky et al., 2003).

At an institutional level, a stronger relationship is found in countries with better stakeholder protections and greater gender parity, suggesting that board cultures where different voices are heard and considered is important to the ESGP–CFP relationship (Post and Byron, 2014; Hoobler et al., 2018), with important implications for policy setting and governance structures. The ESGP–CFP relationship is also stronger for firms located in developing rather than developed countries, perhaps due to the importance of ESGP as a signalling device to improve relationships with stakeholders (Hou et al., 2015).

Finally, from a temporal perspective, longer term ESGP measures have a stronger impact on the ESGP–CFP relationship than shorter term measures (Lu and Taylor, 2016), perhaps reflecting the time required for the effect of ESG activity to emerge.

5 Conclusion

Theoretical expectations for the ESGP–CFP relationship suggest a null to modestly positive link. A systematic review of 21 meta-analytical studies supports the theoretical expectations, on the whole finding a positive, statistically significant but economically modest relationship. The relationship holds under various measures of ESG activity and CFP measures, and under different conditions. The relationship between environmental ESGP and CFP appears stronger than social or governance ESGP and CFP. The relationship between ESGP and operating CFP is stronger than with accounting CFP, which is in turn stronger than with market-based CFP. However, the economically modest association – ESGP as the unit of analysis captures around 2 percent of the explained variance to CFP – suggests that ESG activity is unlikely to be primarily motivated by narrow measures of CFP, yet interest in ESG is extensive and increasing.

In practice, the motivations for ESG activity may be mixed, creating theoretical and methodological issues in identifying the ESGP–CFP relationship being tested in empirical studies (Benabou and Tirole, 2010). It is not clear that ESG measures capture the same construct (Margolis et al., 2007), raising questions around the comparability and generalisability of findings. Perhaps revisiting existing and developing new theoretical frameworks away from a simplistic ESGP–CFP relationship (Grewatsch and Kleindienst, 2017), supported by empirical testing that considers the influence of any endogeneity (Antonakis et al., 2010; Gippel et al., 2015), may assist the development of new, robust, insights on the underlying motivators for ESG activity.

Two main implications may be drawn. Firstly, further work is required to identify and understand the motivators for ESG activity, and the processes that lead to CFP outcomes (as reflected in three of the five main gaps observed in the literature) to better understand processes, the impacts on firm stakeholders, and individual psychological processes that inform ESG activity. The other main implication points in the other direction, namely that more conceptual work is required to understand the motivators and processes of ESG within the firm’s broader strategy and priorities (reflecting two of the five main gaps identified by researchers) to rebalance research away from further empirical research and to connect conceptual streams. Both these implications indicate that further scholarship that views ESG activity as part of the broader bundle of firm activity may be constructive.