Debt covenants in Japanese loan markets: in comparison with the traditional relationship banking

Abstract

This study investigates determinants of debt covenants in Japanese loan markets. We focus on a unique monitoring mechanism by Japanese banks and hypothesise that debt covenants substitute for the traditional main bank governance. Consistently, we find that debt covenants are less likely to be used for firms with stronger ties with their main banks. We also document that such use of debt covenants results in borrower’s upward earnings management. Overall, our evidence suggests that, in the Japanese context, debt covenants are used as a substitute for the main bank system yet they alone are an incomplete monitoring mechanism.

1 Introduction

A long literature highlights that debt covenants are an important monitoring mechanism that governs allocation of cash flow and control rights between lenders and borrowers (Smith and Warner, 1979; Christensen et al., 2016). Consistent with the arguments, a number of empirical studies examine the role and structure of debt covenants and document that they are useful in mitigating conflicts between shareholders/managers and creditors (e.g., Chava and Roberts, 2008; Nini et al., 2012). However, on the other hand, we have much less evidence on the relative importance of debt covenants over other governance mechanisms. Specifically, bank lenders have strong incentives and abilities to directly monitor borrowers due to their stake at risk and private information sources (Diamond, 1984; Fama, 1985; Diamond and Rajan, 2001). As such, the importance of debt covenants can be dependent on the strength of the bank–firm relationship. This study provides initial evidence on the interrelation of debt covenants and direct bank monitoring.

Prior research has examined the relative importance of debt covenants largely by conducting comparative analyses in international settings (Qi et al., 2011; Miller and Reisel, 2012; Hong et al., 2016). In these studies, the broader research question is whether country-level institutions substitute for debt covenants in mitigating conflicts between lenders and borrowers, and scholars consistently document that strong creditor rights/laws relate to the less frequent use of debt covenants. In our study, we take a different approach and focus on the importance of covenants compared to bank direct monitoring via bank-firm relationship. Accordingly, our research question is different from those studies and addresses whether and how the strength of bank–firm relations affects the use of debt covenants.

To answer this question, we focus on a single country and examine debt covenants in Japanese loan markets. Using a single country allows us to keep the institutional environment/legal system constant and thus to draw more meaningful inference of the comparison between debt covenants and bank monitoring. It is worthwhile to focus on Japanese firms for the following reasons. First, Japan is typically classified as a bank-oriented country and has a unique corporate governance through direct monitoring by the main bank (Kaplan and Minton, 1994; Shuto and Iwasaki, 2015). The close tie between a firm and a specific bank is referred to as the main bank system, which is traditionally characterised by concentrated lending, shareholding of client firms and dispatch of board members (Aoki et al., 1994). This specific feature provides a useful research setting to examine how direct bank monitoring relates to the use of covenants. Second, unlike other bank-oriented countries, there is more frequent use of debt covenants in the Japanese loan markets. Existent research has argued that debt covenants are less prevalent in bank-oriented countries (e.g., Leuz et al., 1998; Hong et al., 2016). By contrast to the implications, debt covenants were conventionally included for corporate bonds in the Japanese markets due to regulatory requirements. The practice has spread to the loan markets during the 1990s and Japanese lender banks have been using covenants in their loan agreements over the last decades. The more frequent use of debt covenants in Japan can extend and complement the previous literature and allows us to empirically compare the role with the traditional Japanese bank governance. Finally, past research into debt covenants has been conducted largely in the US context. Therefore, there is a paucity of evidence about whether and how covenants are used outside the United States (Hong et al., 2016). To enhance our limited knowledge on debt covenants, it is worthwhile and interesting to investigate other markets, especially, a non-Western country.

We begin our analysis by constructing a primary dataset on debt covenants in Japan. Although commercial databases (for example, Dealscan) provide a useful source of debt contracts, the coverage is sparse, particularly outside the US. Accordingly, we manually collect information on debt covenants from firms’ annual security reports (‘Yukashouken Houkokusho’, an equivalent to 10-K in SEC filings), resulting in 2,596 firm-years of loan covenants from 2004 to 2013. From the collected data, we find that the type and threshold of debt covenants do not vary among Japanese firms. Specifically, a combination of two covenants, ‘maintenance of net assets’ and ‘maintenance of earnings’, is predominant in Japanese loan agreements. Furthermore, our data show that covenants, such as those directly restricting additional lending, new debt issuance, investments or dividend payments, are hardly used, which contrasts markedly to the US context (Denis and Wang, 2014).

We next examine whether the use of covenants relates to other governance mechanism in the Japanese loan markets. Specifically, under the main bank system, the close relationship between a firm and its main bank can substitute for debt covenants in mitigating conflicts stemming from information symmetries between lenders and borrowers. In other words, debt covenants can be less important for firms with a closer relationship with their main banks, but, conversely, they can be a useful monitoring tool in the absence of close bank–firm association because they restrict borrowers’ moral hazard and provide early warning signals (Christensen et al., 2016). We test this prediction in a sample of 19,370 firm-year observations of Japanese listed companies. Consistently, our regression analyses show that debt covenants are less likely to be used for firms with closer relations with their main banks, providing evidence of substitution between the two monitoring mechanisms. The result is robust to many sensitivity tests, including alternative measures of bank–firm relationship, potential self-selection problem and endogeneity issues in bank–firm relations.

Furthermore, we extend our analysis by examining whether the use of covenants leads to better monitoring outcomes, in particular, in the absence of a close bank–firm relationship. We use borrowers’ discretionary accruals as an outcome of monitoring (Ahn and Choi, 2009). Our regression analysis shows that the interaction of debt covenants and main bank–firm relation yields negative coefficients, indicating the effect of debt covenants depends on the strength of the main bank affiliation. In particular, we document consistent evidence that the use of debt covenants is more likely to lead to higher discretionary accruals when the main bank–firm relation is weak, suggesting that using covenants as a substitute results in borrowers’ upward earnings management, which deteriorates covenant efficiency. Overall, our evidence suggests that, in the Japanese context, debt covenants are used as a substitute for the main bank system yet covenants alone are an incomplete monitoring mechanism.

We contribute to the literature in several significant ways. First, we contribute to the literature on debt covenants. Prior studies on debt covenants have been conducted largely in the US context, and therefore there is a paucity of evidence about debt covenants outside Western countries. We provide large-sample evidence on debt covenants in Japanese loan markets and document remarkable difference from the US studies. Second, although a number of studies have empirically examined the role of debt covenants, the relative importance over other governance mechanisms has remained an open question. This study provides new insight by documenting that debt covenants can substitute for direct monitoring by bank lenders yet covenants alone are an imperfect monitoring mechanism. Third, our evidence also has implications for accounting and finance researchers who use cross-country settings for debt contracts. While there is a growing body of evidence based on international settings, we document a large difference in the number of covenant observations for Japanese firms. This suggests a potential sample bias in prior studies and highlights the importance of rectifying the sparse coverage on debt covenants in international settings.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 develops our hypothesis based on prior literature and characteristics of Japanese debt covenants. Section 3 describes our research design, sample and testing variables. Section 4 presents and interprets the results of our analyses. In Section 5, we conduct additional analyses for the effect of debt covenants on borrowers’ discretionary accruals. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2 Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1 Theories for debt covenants

The importance of debt covenants as a monitoring mechanism is well established. Prior literature suggests that two different theories can provide the raison d'être of debt covenants (Christensen et al., 2016). First, agency theories predict that, under information asymmetry, the use of debt covenants mitigates conflicts of interest between shareholders/managers and bondholders. The seminal work of Smith and Warner (1979) specifies sources of conflicts (example.g., dividend payment, claim dilution and asset substitution) and discusses that covenants can solve these conflicts by restricting managers’ opportunistic wealth transfer actions. Second, on the other hand, incomplete contract theories suggest that the use of covenants mitigates the incompleteness of debt contracts and enhances the contract efficiency. It is costly and almost impossible to write complete contracts that specify all contingencies (Hart, 1995). Thus, debt covenants, which allocate cash flow and control rights contingent on future events, economise the initial costs for writing complete contracts. Under this view, covenants largely function as a trigger for renegotiation or an early warning signal that gives creditors a chance to protect their interests.

Although these two underlying theories are not mutually exclusive and should be viewed as complementary (Christensen et al., 2016), which of these is supported is dependent on the characteristics of debt covenants. Under the agency perspective, debt covenants improve contract efficiency by directly restricting certain managerial actions, such as dividend payments and additional borrowing. On the other hand, under the incomplete contracting perspective, covenants allocate control rights to the contracting parties and do not require certain forms of direct restriction to the extent that they provide an early warning signal and a chance to renegotiate. These arguments indicate that the theoretical backgrounds can differ by the characteristics of debt covenants.

2.2 Debt covenants in Japanese loan markets

For the two different theories, we first describe and analyse the characteristics of Japanese debt covenants. Due to the lack of mandatory requirements on loan documents from central reporting agencies, the information on debt covenants is largely reliant on firms’ voluntary disclosure in the Japanese reporting environment. Accordingly, we use an availability sampling method to obtain our data on debt covenants from firms’ mandatory annual security reports (Yukashouken Houkokusho). Our initial sample of loan covenants consists of 2,596 firm-year observations representing 700 Japanese listed firms from January 2004 to December 2013. The collected sample varies in terms of firms’ disclosure and includes (i) firms disclosing only the existence of covenants (559 firm-years), (ii) firms disclosing the types of covenants (298 firm-years), and (iii) firms disclosing the types and thresholds of covenants (1,739 firm-years). As a result, approximately 78.5 percent of our sample provides information about the types of debt covenants and we primarily focus on those observations hereafter in this section.

Table 1 reports the types and frequency of debt covenants. As shown in the table, we find that ‘maintenance of net assets’ (93.5 percent) and ‘maintenance of earnings’ (82.4 percent) are predominant in the Japanese loan markets, which contrasts markedly to the US context where various covenants are used (Dichev and Skinner, 2002; Demerjian and Owens, 2016). This homogeneity may stem from an old Japanese regulation for unwarranted bonds that required issuers to include these two covenants during the 1980s. In other words, lender banks may follow and mimic the old convention and apply the similar types of covenants for their loan contracts. Consistently, the use of other types of covenants is not prevalent. Debt covenants, such as those directly restricting additional lending, additional debt issuance, investments or dividends, are hardly ever used, which is also notably different from the US (Nini et al., 2012; Denis and Wang, 2014). For the number of covenants applicable to each firm, untabulated result shows that more than 60 percent of our sample includes two items, most of which are a combination of ‘maintenance of net assets’ and ‘maintenance of earnings’.

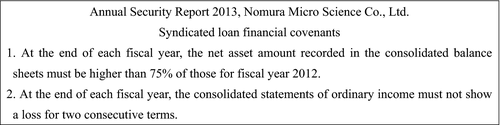

Using observations that disclose both types and thresholds of debt covenants (1,739 firm-years), we investigate the definitions of ‘maintenance of net assets’ and ‘maintenance of earnings’ because these are the most frequently used in the Japanese context. First, we find that ‘maintenance of net assets’ generally requires borrowers to maintain over X percent of net assets at the end of the fiscal year compared to those of the reference year (i.e., the net worth covenant). Untabulated statistics show that the threshold is set at 75 percent for more than 60 percent of the covenants. In addition, approximately 90 percent of the observations use the book value of net assets as reported on firms’ balance sheet without any adjustments. Second, for covenants on ‘maintenance of earnings’, we find that the most frequently used earnings are ‘net income before extraordinary items’ (85.0 percent) followed by ‘operating income’ (23.3 percent). Further, over 70 percent of the covenants require the borrower not to report losses for two consecutive years. These findings confirm that Japanese debt covenants are uniform and untailored in terms of their characteristics. Figure 1 illustrates a typical example of a debt covenant in Japan.

Moreover, we examine 325 firm-years that violate debt covenants during the sample period. The percentage out of the initial sample, 12.5 percent, is relatively small and suggests that the use of covenants does not always trigger the violation and lead to default. In Japan, violation of covenants gives lenders rights to require immediate full loan repayments and thus borrowers have to accelerate their debt obligations when they violate. However, we find that lenders are more likely to grant waivers for borrowers’ technical default (48.3 percent) and it is very rare that borrowers pay off their debts in full (5.8 percent). In addition, there are cases in which bank lenders modify the lending agreements to resolve borrowers’ status of violation (16.0 percent). The evidence is similar to those in prior studies, reporting that violation is not a serious event associated with bankruptcy (Dichev and Skinner, 2002; Denis and Wang, 2014).

These characteristics of Japanese debt covenants, particularly their uniformity and the presence of waivers for violation, are likely consistent with the view under incomplete contract theories. If covenants are used for the purpose of restricting managers’ opportunistic actions as predicted by the agency perspective, lenders should carefully tailor them to prevent borrowers’ moral hazards ex ante (Christensen et al., 2016). Rather, untailored uniform covenants are expected to economise the initial costs for writing loan contracts and serve as an early warning signal or a trigger for renegotiations. Consistently, most Japanese covenants are financial covenants which are contingent on the borrower’s performance and financial health as measured by earnings and net assets. Similarly, evidence that Japanese banks tend to grant waivers for violation implies that debt covenants are merely a trigger to obtain controls and protect their interests.

2.3 Hypothesis development

Prior literature investigates the role of debt covenants by identifying the determinants and provides evidence on when and how they are used in debt markets. For example, El-Gazzar and Pastena (1991) document that loan characteristics, such as materiality of debts, existence of collateral, and borrower’s leverage ratio, affect the use of covenants, suggesting that they are used for reducing risks in large and unsecured loans. Begley and Feltham (1999) focus on managerial incentives and report that alignment of managers’ preference with shareholders influences the use of financial covenants. More recently, Bradley and Roberts (2015) provide comprehensive evidence and find that covenants are used for small, highly growing and levered firms and also for loans made by investment and syndicate banks.

While the studies discussed above largely focus on the US, some recent studies examine the importance of debt covenants by conducting comparative analyses in international settings. These studies examine whether country-level institutional factors can substitute for covenants in mitigating conflicts between lenders and borrowers. Qi et al.(2011) find that bonds of firms incorporated in countries with strong creditor rights include fewer covenants. Similarly, Miller and Reisel (2012) and Hong et al.(2016) report that debt covenants are more prevalent in countries with stronger law enforcement and weaker creditor rights. By and large, these empirical studies are consistent with the theories of debt covenants and suggest that they play a significant role when lenders bear greater risks in terms of borrower’s and loan characteristics as well as legal environments.

In this study, we extend the literature by examining the determinants of debt covenants in the Japanese loan markets. Specifically, we focus on the unique monitoring mechanism of Japanese banks and investigate the relative importance of debt covenants within an economy. It is well known that Japan has a peculiar corporate governance through direct monitoring by the main bank (Kaplan and Minton, 1994; Shuto and Iwasaki, 2015). The close tie between a firm and a specific bank is referred to as the main bank system, which is traditionally characterised by concentrated lending, shareholding of client firms and dispatch of board members (Aoki et al., 1994). The main bank takes primary responsibility for monitoring the client firm and particularly plays a significant role during times of borrower distress by taking the initiative to restructure the firm (Morck and Nakamura, 1999). Thus, the monitoring mechanism is often called ‘contingency governance’ (Aoki et al., 1994).

We expect that this specific bank–firm relationship affects the use of debt covenants for three reasons. First, the close tie with the main bank itself can mitigate information asymmetry and thus reduces the need for including covenants as a monitoring mechanism. On the other hand, the absence of close bank–firm relations indicates lender’s limited access to borrower’s status, requiring another tripwire to obtain control and cash flow rights over borrowers. Second, both the main bank system and debt covenants can serve as contingent monitoring mechanisms. As shown in the previous section, Japanese firms tend to use financial covenants that give the lender control over the borrower contingent on their economic status. Such use of covenants can be an effective substitute for the main bank system as it provides the chance and right to intervene in distressed borrowers in a timely manner. Third, prior studies document that the main bank system has reduced the prominent role of monitoring over the last decades, largely due to non-performing loans after the bursting of the Japanese stock and real estate bubbles (Peek and Rosengren, 2005). Arikawa and Miyajima (2007, 2015) document that dispatch of board members and shareholding of client firms became less frequent among Japanese banks. Given this economic circumstance, lenders have incentive to use covenants to supplement the weakened bank–firm relationship. Following the above discussion, we expect that debt covenants and the main bank system are substitutable in the Japanese context, and predict that, ceteris paribus, debt covenants are less likely to be used for firms with stronger ties with their main banks.

3 Empirical tests

3.1 Regression model

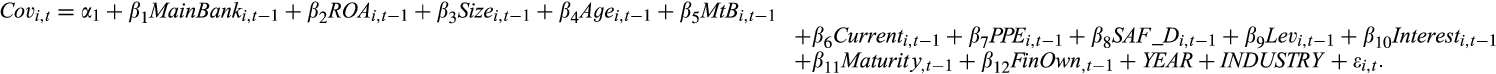

()

()

Covi,t is a dummy variable that equals one if debt covenants exist in loan contracts for firm i in year t and zero otherwise. As discussed in Section 2.2, we draw our data on debt covenants from firms’ annual security reports (Yukashouken Houkokusho). Specifically, using the EOL/Pronexus database, a most comprehensive source for financial filings of Japanese listed firms, we search for and manually collect both qualitative and quantitative data by using the term ‘covenants’. As a result, we identify 2,596 firm-years of debt covenants from January 2004 to December 2013.

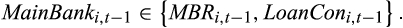

Our principal variable is MainBank, which takes one of two different measures of firm’s loan structure. First, following prior studies, we define the main bank as the firm’s largest lender (Aoki et al., 1994; Kang et al., 2000). Then, we compute the main bank relation as the ratio of loans from the main bank to total loans (MBR). However, because this definition may lead to mis-specification of the actual main bank for a firm, we also compute the concentration of firm’s loan balances. LoanCon is the Herfindahl–Hirschman index of loans to a firm, calculated as the sum of the squares of loans from each bank as a percentage of total loans. While this does not specify the name of the firm’s main bank, it can represent the firm’s loan structure and affiliation with its lenders. As well as MBR, a higher value of LoanCon indicates stronger main bank–firm relations for the firm-year. Therefore, according to our hypothesis, the signs of these variables are expected to be significantly negative.

The other variables in Equation (1) are controls. As discussed in Section 2, prior studies have shown that both borrower’s and loan characteristics affect the use of covenants. For the former, we include the following seven financial key ratios: ROA, Size, Age, MtB, Current, PPE and SAF_D. For the latter, we include four variables: Lev, Interest, Maturity and FinOwn. In Japan, details of each loan contract (example.g., lender’s name, loan size, maturity and interest rates) are rarely disclosed publicly. Hence, it is difficult to construct variables based on the loan level. Alternatively, we use information in firms’ annual reports and compute weighted average loan interests and maturity for each firm-year (see Appendix II). In terms of shareholder structure, we include FinOwn to control the relationship between borrowers and dealing banks.

We estimate Equation (1) using firm-year unbalanced panel data. We adjust the standard errors for heteroscedasticity, serial- and cross-sectional correlation using a two-dimensional cluster at the firm and year levels (Petersen, 2009). Moreover, we include industry and year dummies to control industry- and year-fixed effects, respectively.

3.2 Sample and descriptive statistics

- The firms must be compliant with Japanese accounting standards.

- A fiscal period must have 12 months.

- The firms must be non-financial (excluding bank, insurance and security sectors).

- The firms must have loan balances at the fiscal year end.

- All data must be available for the estimation of Equation (1).

For the fourth criterion, we do not presume that loan covenants exist for firms without loan balances. As our interest focuses on the determinants of debt covenants and the relationship with the main bank, we exclude observations without any loans at the fiscal year end. We obtain our data from the NEEDS-FinancialQUEST, a most comprehensive financial database in Japan.

Our main testing sample consists of 19,587 firm-year observations: 1,866 observations with covenants and 17,721 observations without them. Again, we note that our debt covenant observations are largely based on firms’ voluntary disclosure, which can cause a potential bias in the sample due to observations that have debt covenants but do not report them publicly. We come back to this issue in Section 4.2. In order to mitigate the influence of outliers, we winsorise all continuous variables in Equation (1) at the 1 and 99 percent levels at the firm-year level.

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics. The mean of Cov, our dependent variable, indicates a ratio of covenant observations out of our testing sample. The value is approximately 9.5 percent, suggesting disproportionality in our sample. However, logistic regression is an appropriate approach where disproportionate sampling from two populations occurs. In logistic regression, the coefficients of the independent variables are not affected by the unequal sampling rates.

Table 3 shows the correlations among our testing variables. Consistent with our hypothesis, our two main bank measurements (MBR and LoanCon) are negatively correlated with Cov (p-values < 0.001, two-tailed). Among others, the correlations between MBR and LoanCon are positive and extremely high (0.966 and 0.948), indicating that the proportion of loans financed from the main bank substantially determines firm’s loan structure. To check multicollinearity among our independent variables, we compute the variance inflation factors and find that these are smaller than five in all estimations; as such we conclude that this is not present to such an extent that it materially biases coefficient standard errors.

4 Empirical results

4.1 The use of debt covenants and the bank–firm relationship

Table 4 reports the results for our determinant tests. The first column shows the results using only determinants identified in prior studies, suggesting both borrower’s and loan characteristics affect the use of covenants as predicted. In columns (2) and (3), we test our hypothesis and find the estimated coefficients on MBR and LoanCon are negative and statistically significant. The z-statistics are −3.59 and −3.94, respectively. Consistent with our hypothesis, the results indicate that debt covenants are less likely to be used for firms with closer relationship with their main banks.

In terms of control variables, we find consistent evidence that the variables ROA, Size, Age, SAF_D, Lev, Interest and Maturity are associated with the use of debt covenants. One difference from prior studies is the negative coefficient of ROA, which has hitherto been reported as positive in the literature (Graham et al., 2008). However, our result is consistent with predictions in agency theories because the agency problem between shareholders and creditors is more pronounced when the firm has a greater risk of bankruptcy (Smith and Warner, 1979).

4.2 Robustness checks

4.2.1 Alternative measures for the bank–firm relationship

We conduct a number of additional tests to evaluate the robustness of our empirical results. First, we use alternative variables for the firm’s relationship with the main bank. While we defined the main bank as a given firm’s largest lender, the specification of the actual main bank is substantially challenging. Alternatively, we use a database called Nikkei-Cges that provides unique corporate governance data for Japanese listed firms and apply three additional measures on the bank–firm relationship: MBR_N, MBOwn_N and MBOutside_N. The first is the ratio of loans provided by the main bank to total loans, the second is the ratio of shares owned by the main bank, and the last one is a dummy variable that takes a value of one if the firm has outside directors from its main bank and zero otherwise. According to our hypothesis, all those main bank variables are negatively associated with the use of debt covenants.

Columns (1)–(3) of Table 5 show the results of using these alternative variables. As Nikkei-Cges started recording data on main banks in 2006, we exclude observations whose fiscal year ends in 2004 and 2005. Consistently, we find that the coefficient on MBR_N is negative and significant at the 5 percent level (z-value = −2.38). On the other hand, the coefficients on MBOwn_N and MBOutside_N are insignificant. These suggest that results in the previous section are robust to an alternative metric of the bank–firm relation as measured by borrower’s loan structure. Moreover, the evidence supports a view that bank–firm affiliation is no longer captured by shareholding and board members (Arikawa and Miyajima, 2007, 2015).

4.2.2 The effect of violating firms

Our second test considers the effect of firms that violate covenants. It is expected that violating firms are largely distressed and exhibit different financial characteristics. Moreover, Japanese listed firms are obliged to disclose information on material uncertainty when identified events cast significant doubts on the firm’s ability to continue as a going concern. Hence, our measurement of covenants can be biased by violating firms to the extent that the ‘identified events’ include firm’s covenant violation. To consider these potential effects, we exclude 240 firm-years that violate debt covenants at the end of fiscal years. Untabulated results report that the coefficients on MBR and LoanCon are negative and significant at the 1 percent level (z-statistics are −3.16 and −3.65, respectively), indicating our findings are robust to the effect of violating firms.

4.2.3 Self-selection problem

As our measurement of Cov is based on firm’s voluntary disclosure, the results may be affected by firms that have covenants but do not report them publicly. If so, our results are subject to endogeneity stemming from self-selection bias. To address this issue, we identify and exclude suspicious observations from our analyses. Using a set of control variables in Equation (1), we first estimate the predicted probability of the existence of debt covenants. Then, we define suspicious as firm-years of Cov = 0 that have higher probability than the median of that for subsample of Cov = 1. This identifies 3,055 firm-years of suspicious observations, which we remove to mitigate potential self-selection bias. Untabulated results show that the coefficients on MBR and LoanCon remain negative and significant at the 1 percent level (z-values are −3.40 and −3.69, respectively). We also use the third quartile and median of predicted probability in a subsample of Cov = 0 in defining suspects and confirm that selecting a particular discriminant point does not affect our results.

4.2.4 Endogeneity in bank–firm relations

The preceding analyses cannot rule out the possibility that the main bank–firm relation is endogenous. In particular, the bank–firm relationship can be subject to the firm’s financial policy and thus endogenously determined by other unobservable factors, such as firm’s preference and motivation for financing. To address this potential concern, we perform instrumental variable regression analyses as suggested by Hentschel and Kothari (2001) and Frankel et al.(2006). This involves rank-ordering the endogenous variable MainBank and then assigning all sample firm-years to three ranked portfolios (i.e., zero to two) using the 33rd and 67th percentiles as break points. We use the portfolio ranking as an instrument in a two-stage probit regression. The predicted values from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of the portfolio ranking on the endogenous variable are used in the second stage regression by replacing the original endogenous variable. The assumption for this procedure is that the crude portfolio ranks are indicative about the level of the bank–firm relationship, but the partitioning is so crude that it is less likely to pick up the endogenously determined variation in firm’s relationship with the main bank. Table 1 reports the results for the two-stage probit regression analyses. While the Wald test of exogeneity weakly rejects the null hypothesis of no endogeneity for MBR, it suggests that LoanCon can be treated as an exogenous variable. Similar to those in the main analyses, variables for the bank–firm relation remain statistically significant. Moreover, we also conduct sensitivity checks using four and five portfolios based on the values of quartiles and quintiles, respectively, and find that the tenor of our results is unchanged. Although this analysis suggests that the reported results are robust to endogeneity problems, it must be acknowledged that the validity of portfolio ranks as an instrument is dependent on the assumption of exogenous assignments (Larcker and Rusticus, 2010).

| Types of debt covenants | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Maintenance of net assets | 1,904 | 93.5 |

| Maintenance of earnings | 1,678 | 82.4 |

| Balance of debt with interest | 251 | 12.3 |

| Debt service coverage ratio | 87 | 4.3 |

| Equity ratio | 83 | 4.1 |

| Leverage ratio | 79 | 3.9 |

| Interest coverage ratio | 62 | 3.0 |

| Restrictions on lending | 57 | 2.8 |

| Maintenance of bond or credit rating | 56 | 2.7 |

| Restrictions on investments | 44 | 2.2 |

| Inventory turnover period in days | 22 | 1.1 |

| Restrictions on distribution | 16 | 0.8 |

| Current ratio | 14 | 0.7 |

| Total number of observations | 2,037 | |

4.2.5 Other empirical issues

Furthermore, we include a lagged variable for the use of covenants to control for the persistence of firm’s disclosure policy. As our measurement of covenants depends on firm’s voluntary disclosure, it is possible that the firm continues to disclose information about covenants once it started to do so. If so, we may overestimate the measurement to the extent that the firm repeatedly refers to the same covenants every year until the loan matures. To alleviate this concern, we include a lagged variable Covi,t−1 as an independent variable and estimate Equation (1). Although this does not indicate any theoretical linkage, the effect could be significant particularly for our firm-year sample. Untabulated results present that the coefficients of Covi,t−1are 5.47 and 5.46 (z-values are 26.44 and 26.35) for estimations using MBR and LoanCon, respectively. On the other hand, the coefficients on MBR and LoanCon remain negative and statistically significant at the 1 percent level (z-values are −2.62 and −2.66, respectively). Finally, we exclude 64 firm-years that have covenants both in their loans and bonds to configure a more rigorous context for testing loan covenants. Again, results are quite similar to those in the main analysis.

5 Additional analyses

Our findings thus far indicate that debt covenants in Japan are used as a substitute to the main bank governance. However, it is still in question whether such use of covenants leads to better monitoring outcomes, in particular, in the absence of strong bank–firm relations. In these cases, debt covenants are more likely to be a pure substitute and we should expect that they play an important role in place of direct monitoring by the main bank. In this section, we focus on borrowers’ discretionary accruals as an outcome of bank monitoring (Ahn and Choi, 2009) and additionally examine whether covenants can be a good substitute for the main bank governance.

Creditors generally prefer conservative earnings because their profit claims are largely fixed and less relevant with increased earnings (Kothari et al., 2010). Conservative earnings can inhibit managers’ ex ante moral hazard by reducing earnings available for distribution and enhance the value of covenants as an early warning signal. By contrast, aggressive earnings can reduce the efficiency of covenants by delaying the early detection of borrowers’ financial distress, which harms creditors’ benefits. Leftwich (1983) and Beatty et al.(2008) document that creditors modify lending agreements to incorporate their demands for conservative accounting.

However, it is yet unclear whether the use of debt covenants leads to aggressive or conservative earnings. For instance, Nikolaev (2010) argues that untimely reporting of losses is likely to tarnish the firm’s reputation in credit markets and therefore managers have an incentive to meet the demand for conservative accounting. By contrast, the positive accounting theory predicts that debt covenants give managers incentives to manipulate earnings in order to avoid the violation of covenants (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986; Dichev and Skinner, 2002).

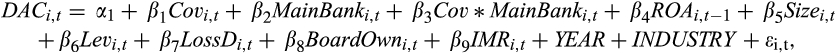

()

()We include IMR to mitigate endogeneity issues. Because our main analyses have already shown that the use of debt covenants is endogenously determined, we consider the effect by including the inverse Mills ratio obtained from Probit estimation of Equation (1). Therefore, our analyses are equivalent to the Heckman two-stage regression analysis, which alleviates self-selection bias and endogeneity. The testing sample reduces to 17,490 firm-years due to data availability for estimating discretionary accruals and we exclude observations that violate debt covenants in year t to rule out the abnormal effect on discretionary accruals.

Table 7 provides the results. From column (1), we find that both Cov and MBR positively relate to borrower’s discretionary accruals. However, the interaction term (Cov*MBR) exhibits a negative and significant coefficient at the 5 percent level, suggesting that covenants are more likely to result in higher (lower) discretionary accruals in the absence (presence) of the main bank–firm relationship. Moreover, the difference in coefficients between Cov and Cov*MBR is statistically significant (t-value = 2.21). This implies the effect of covenants is dependent on the strength of main bank affiliation. Column (2) provides similar results using LoanCon.

To focus on the effect of covenants as a pure substitute, we construct a dummy variable based on the first tertile of main bank variables (MainBank_Low) and incorporate the interaction with Cov. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 2 present the results. As shown, the coefficients on Cov*MBR_Low and Cov*LoanCon_Low are positive and significant at the 1 percent level. The results are consistent with those in columns (1) and (2) and suggest that covenants lead to higher discretionary accruals and thus more aggressive earnings in the absence of close bank–firm relations. We confirm that the result is very similar when we use the median and first quartile of main bank variables in defining the dummy variables of MainBank_Low.

| Obs. | Mean | SD | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covi,t | 19,587 | 0.095 | 0.294 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| MBRi,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.416 | 0.192 | 0.053 | 0.283 | 0.370 | 0.497 | 1.000 |

| LoanConi,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.302 | 0.194 | 0.024 | 0.182 | 0.248 | 0.348 | 1.000 |

| ROAi,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.042 | 0.055 | −0.225 | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.064 | 0.429 |

| Sizei,t −1 | 19,587 | 10.606 | 1.512 | 6.022 | 9.533 | 10.431 | 11.489 | 14.660 |

| Agei,t −1 | 19,587 | 3.860 | 0.557 | 0.693 | 3.638 | 4.007 | 4.190 | 4.663 |

| MtBi,t −1 | 19,587 | 1.209 | 1.204 | 0.193 | 0.576 | 0.878 | 1.408 | 11.178 |

| Currenti,t −1 | 19,587 | 1.432 | 0.864 | 0.316 | 0.951 | 1.249 | 1.689 | 11.446 |

| PPEi,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.347 | 0.191 | 0.003 | 0.210 | 0.332 | 0.464 | 0.862 |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.253 | 0.435 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Levi,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.616 | 0.198 | 0.079 | 0.482 | 0.615 | 0.741 | 0.969 |

| Interesti,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.051 |

| Maturityi,t −1 | 19,587 | 1.960 | 0.716 | 1.009 | 1.418 | 1.826 | 2.318 | 4.506 |

| FinOwni,t −1 | 19,587 | 0.196 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.089 | 0.171 | 0.286 | 0.530 |

- Covi,t is a dummy variable that equals one if debt covenants exist in loan contracts for firm i in year t and zero otherwise; MBRi,t−1 denotes the percentage of loans financed from the main bank to total loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1; LoanConi,t−1 denotes the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index of loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1, calculated as the sum of the squares of loans from each bank as a percentage of total loans; ROAi,t−1 is the net income before extraordinary items for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets; Sizei,t−1 denotes the natural log of total assets for firm i in year t−1; Agei,t−1 is the natural log of the number of years firm i has been established at the fiscal year end t−1; MtBi,t−1 denotes the market-to-book ratio at the fiscal year end for firm i in year t−1; Currenti,t−1 denotes the ratio of current assets to current liability at the fiscal year end for firm i in year t−1; PPEi,t−1 denotes the amount of plant, property and equipment for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets; SAF_Di,t−1 is a dummy variable that equals one if the value of SAF2002 (Shirata, 2003) for firm i in year t−1 is lower than 0.68 and zero otherwise; Levi,t−1 denotes the amount of total liabilities for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets; Interesti,t−1 denotes the weighted average interest rate on borrowing loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1; Maturityi,t−1 denotes the weighted average maturity of borrowing loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1; and FinOwni,t−1 denotes the percentage of firm shares held by financial institutions for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1. All continuous variables are winsorised at the 1 and 99 percent levels.

These findings provide additional important insights. First, debt covenants are likely to give borrowers an incentive to manage earnings upwards when the bank–firm relation is weak. This particularly highlights the negative consequences of accounting-based covenants (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986) and collective action problem among lenders: the more banks are involved with a borrower, the less incentive each bank has to monitor it. Second, the findings suggest that debt covenants themselves are not good substitutes for the main bank governance in terms of monitoring outcome. Rather, the negative coefficients on Cov*MainBank indicate that a combination of relationship- and contract-based monitoring is more likely to result in conservative earnings that are beneficial to creditors.

6 Conclusions

In this study, we examine debt covenants in the Japanese loan markets and investigate their relative importance by comparing them with the unique monitoring mechanism of the main bank. We report three main findings. First, our primary dataset on Japanese loan covenants shows that the types and contents of covenants do not vary among firms. In most cases, they consist of a combination of maintenance of net assets and accounting earnings, suggesting debt covenants largely serve as an early warning signal or a trigger for renegotiation in the Japanese context. Second, we focus on a unique monitoring mechanism, the main bank system, and find that debt covenants are less likely to be used for firms with a stronger relationship with their main banks. The evidence suggests that debt covenants substitute for the traditional main bank monitoring. Third, we find that the use of covenants as a substitute for main bank monitoring is more likely to result in borrower’s upward earnings management, which can harm lender’s benefits. Overall, our evidence suggests that, in the Japanese context, debt covenants are used as a substitute for the main bank governance, yet they alone are an incomplete monitoring mechanism.

We contribute to the literature in significant ways. Prior studies on debt covenants have been conducted largely in the US context, and therefore, there is a paucity of evidence outside Western countries. We provide large-sample evidence of Japanese loan covenants and document remarkable difference from the US studies. Moreover, we shed new light on the importance of covenants within an economy. Our evidence indicates that debt covenants can substitute for direct monitoring by bank lenders, yet they alone are imperfect. Finally, the evidence should draw attention of researchers who use international settings for debt covenants. We present a large difference in the number of Japanese covenants from previous international studies, suggesting a potential sample bias and the importance of rectifying the sparse coverage in cross-country settings.

All studies are subject to caveats, and ours is no exception. First, our sample of debt covenants depends largely on firm’s voluntary disclosure, which inevitably makes the findings subject to possible self-selection bias. We attempt to control the issue by conducting a number of robustness checks. However, to the extent that these controls are not sufficient, readers should interpret the results with reasonable caution. Second, the findings in this study are based on firm-year observations rather than loan-years, due to the data unavailability for loan details in the Japanese reporting environment. Thus, the potential heterogeneity among loans within a firm has not been considered. Third, the evidence in this paper might be specific to Japanese firms. Because Japan has experienced a long economic stagnation, our findings may be subject to the effect of long-term recession and underlying macro-economic structural changes. Therefore, the findings must be interpreted carefully in terms of their generalisability. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study enhances our knowledge about whether and how debt covenants are used in a different context from that of Western countries.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covi,t | (1) | −0.028 | −0.036 | −0.112 | 0.033 | −0.028 | −0.017 | −0.044 | 0.015 | 0.115 | 0.110 | 0.094 | 0.082 | −0.048 | |

| MBRi,t −1 | (2) | −0.035 | 0.948 | 0.032 | −0.259 | −0.110 | −0.051 | 0.188 | −0.092 | −0.014 | 0.092 | −0.224 | −0.046 | −0.232 | |

| LoanConi,t −1 | (3) | −0.041 | 0.966 | 0.046 | −0.303 | −0.135 | −0.062 | 0.232 | −0.116 | −0.037 | 0.072 | −0.267 | −0.076 | −0.269 | |

| ROAi,t −1 | (4) | −0.091 | 0.029 | 0.039 | 0.058 | −0.137 | 0.348 | 0.217 | 0.027 | −0.502 | −0.178 | −0.146 | 0.044 | 0.097 | |

| Sizei,t −1 | (5) | 0.021 | −0.214 | −0.219 | 0.039 | 0.354 | 0.108 | −0.084 | 0.061 | −0.072 | −0.074 | 0.123 | 0.186 | 0.657 | |

| Agei,t −1 | (6) | −0.053 | −0.108 | −0.123 | −0.112 | 0.284 | −0.071 | −0.037 | 0.100 | −0.013 | 0.036 | 0.020 | 0.022 | 0.473 | |

| MtBi,t −1 | (7) | −0.007 | 0.027 | 0.030 | 0.204 | −0.002 | −0.117 | −0.133 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.273 | 0.088 | 0.092 | |

| Currenti,t −1 | (8) | −0.020 | 0.236 | 0.266 | 0.108 | −0.086 | −0.068 | −0.096 | −0.485 | −0.159 | −0.080 | −0.567 | −0.030 | 0.005 | |

| PPEi,t −1 | (9) | 0.013 | −0.087 | −0.104 | 0.031 | 0.080 | 0.124 | 0.004 | −0.389 | −0.073 | 0.001 | 0.075 | 0.345 | 0.084 | |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | (10) | 0.115 | −0.005 | −0.015 | −0.443 | −0.065 | −0.045 | 0.102 | −0.084 | −0.062 | 0.298 | 0.265 | −0.046 | −0.153 | |

| Levi,t −1 | (11) | 0.092 | −0.211 | −0.231 | −0.079 | 0.140 | −0.052 | 0.256 | −0.494 | 0.090 | 0.252 | 0.179 | 0.099 | −0.030 | |

| Interesti,t −1 | (12) | 0.101 | 0.129 | 0.121 | −0.152 | −0.065 | −0.008 | 0.086 | −0.015 | −0.007 | 0.287 | 0.134 | 0.157 | −0.098 | |

| Maturityi,t −1 | (13) | 0.064 | 0.035 | 0.027 | 0.024 | 0.215 | 0.013 | 0.037 | 0.053 | 0.350 | −0.039 | 0.117 | 0.070 | 0.106 | |

| FinOwni,t −1 | (14) | −0.049 | −0.219 | −0.223 | 0.073 | 0.647 | 0.392 | −0.019 | −0.042 | 0.070 | −0.146 | −0.102 | −0.032 | 0.112 |

- Pearson’s correlation coefficients appear below the diagonal; Spearman’s correlation coefficients appear above the diagonal. All variables are defined in Appendix I.

| Dependent variable = Covi,t | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted sign | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Coef. | z-value | Coef. | z-value | Coef. | z-value | ||

| MBRi,t −1 | − | −0.98 | [−3.59]*** | ||||

| LoanConi,t −1 | − | −1.21 | [−3.94]*** | ||||

| ROAi,t −1 | − | −3.58 | [−4.02]*** | −3.71 | [−3.99]*** | −3.76 | [−3.96]*** |

| Sizei,t −1 | ? | 0.14 | [3.41]*** | 0.13 | [3.08]*** | 0.13 | [3.00]*** |

| Agei,t −1 | − | −0.21 | [−2.35]** | −0.22 | [−2.45]** | −0.23 | [−2.51]** |

| MtBi,t −1 | − | −0.07 | [−1.68]* | −0.07 | [−1.56] | −0.06 | [−1.48] |

| Currenti,t −1 | − | 0.02 | [0.36] | 0.05 | [0.78] | 0.07 | [0.94] |

| PPEi,t −1 | − | 0.41 | [1.44] | 0.38 | [1.31] | 0.37 | [1.27] |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | + | 0.41 | [3.48]*** | 0.39 | [3.39]*** | 0.39 | [3.38]*** |

| Levi,t −1 | + | 1.39 | [6.09]*** | 1.28 | [5.56]*** | 1.25 | [5.40]*** |

| Interesti,t −1 | ? | 32.72 | [4.30]*** | 37.02 | [4.83]*** | 38.04 | [4.98]*** |

| Maturityi,t −1 | + | 0.21 | [3.19]*** | 0.23 | [3.36]*** | 0.23 | [3.36]*** |

| FinOwni,t −1 | − | −0.65 | [−1.23] | −0.81 | [−1.55] | −0.85 | [−1.61] |

| Year Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | ||||

| Industry Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.117 | 0.120 | 0.122 | ||||

| Wald Chi2 | 1258.20 | 1297.93 | 1310.78 | ||||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 19,370 | 19,370 | 19,370 | ||||

| Dep. Var. = 1 | 1,866 | 1,866 | 1,866 | ||||

| % | 9.63% | 9.63% | 9.63% | ||||

- All variables are defined in Appendix I. All z-statistics are corrected for heteroscedasticity, and cross-sectional and time-series correlation using a two-way cluster at the firm and year level (Petersen, 2009). A total of 217 firm-year observations are omitted from estimation due to the perfect correlations between dependent variables and some industry dummies.

- ***, **, * Indicate statistical significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

| Dependent variable = Covi,t | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted sign | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Coef. | z-value | Coef. | z-value | Coef. | z-value | ||

| MBR_Ni,t −1 | − | −0.60 | [−2.38]** | ||||

| MBOwn_Ni,t −1 | − | −7.92 | [−1.42] | ||||

| MBOutside_Ni,t −1 | − | 0.05 | [0.23] | ||||

| ROAi,t −1 | − | −3.82 | [−3.30]*** | −6.79 | [−4.30]*** | −3.68 | [−4.05]*** |

| Sizei,t −1 | ? | 0.11 | [2.46]** | 0.05 | [0.90] | 0.14 | [3.36]*** |

| Agei,t −1 | − | −0.16 | [−1.83]* | −0.03 | [−0.29] | −0.20 | [−2.24]** |

| MtBi,t −1 | − | −0.08 | [−1.87]* | −0.09 | [−1.60] | −0.07 | [−1.56] |

| Currenti,t −1 | − | 0.01 | [0.12] | −0.03 | [−0.39] | 0.03 | [0.38] |

| PPEi,t −1 | − | 0.49 | [1.65] | 0.43 | [1.05] | 0.44 | [1.52] |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | + | 0.40 | [3.27]*** | 0.43 | [3.54]*** | 0.41 | [3.51]*** |

| Levi,t −1 | + | 1.16 | [4.80]*** | 1.66 | [5.19]*** | 1.39 | [6.07]*** |

| Interesti,t −1 | ? | 43.99 | [4.46]*** | 23.04 | [2.43]** | 32.40 | [4.17]*** |

| Maturityi,t −1 | + | 0.24 | [3.44]*** | 0.26 | [3.74]*** | 0.20 | [3.09]*** |

| FinOwni,t −1 | − | −0.69 | [−1.32] | −0.08 | [−0.11] | −0.69 | [−1.29] |

| Year Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | ||||

| Industry Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.101 | 0.103 | 0.118 | ||||

| Wald Chi2 | 904.90 | 754.30 | 1254.96 | ||||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 13,656 | 12,560 | 19,122 | ||||

| Dep. Var. = 1 | 1,618 | 1,263 | 1,834 | ||||

| % | 11.85% | 10.06% | 9.59% | ||||

- All variables are defined in Appendix I. All z-statistics are corrected for heteroscedasticity, and cross-sectional and time-series correlation using a two-way cluster at the firm and year level (Petersen, 2009). Observations for each estimation vary due to the data availability for variables on the main bank.

- ***, **, * Statistical significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

| Dependent variable = Covi,t | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted sign | (1) | (2) | |||

| Coef. | z-value | Coef. | z-value | ||

| MB_Instrumenti,t −1 | − | −0.38 | [−2.30]** | ||

| LC_Instrumenti,t −1 | − | −0.51 | [−2.69]*** | ||

| ROAi,t −1 | − | −2.04 | [−4.57]*** | −2.04 | [−4.56]*** |

| Sizei,t −1 | ? | 0.07 | [2.84]*** | 0.05 | [2.78]*** |

| Agei,t −1 | − | −0.12 | [−2.45]** | −0.13 | [−2.53]** |

| MtBi,t −1 | − | −0.03 | [−1.44] | −0.03 | [−1.35] |

| Currenti,t −1 | − | 0.03 | [0.79] | 0.04 | [0.95] |

| PPEi,t −1 | − | 0.20 | [1.18] | 0.19 | [1.17] |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | + | 0.21 | [3.82]*** | 0.20 | [3.77]*** |

| Levi,t −1 | + | 0.72 | [5.55]*** | 0.71 | [5.39]*** |

| Interesti,t −1 | ? | 19.24 | [5.07]*** | 19.70 | [5.12]** |

| Maturityi,t −1 | + | 0.12 | [3.61]*** | 0.12 | [3.63]*** |

| FinOwni,t −1 | − | −0.40 | [−1.35] | −0.42 | [−1.44] |

| Year Fixed Effects | Included | Included | |||

| Industry Fixed Effects | Included | Included | |||

| Wald Chi2 | 513.08 | 513.28 | |||

| Prob> Chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Wald tests of exogeneity | 3.18 | 1.17 | |||

| Prob> Chi2 | 0.075 | 0.279 | |||

| N | 19,370 | 19,370 | |||

- This table shows the results using two-stage probit estimations. The first stage is OLS regression using portfolio ranks based on MainBanki,t−1 as an instrument variable. The predicted values from the first stage regression of the portfolio ranking on the endogenous variable, MBRi,t−1 and LoanConi,t−1, are defined as MB_Instrumenti,t−1 and LC_Instrumenti,t−1, respectively. All other variables are defined in Appendix I. Wald tests of exogeneity show statistics for the null hypothesis of no endogeneity. All z-statistics are corrected for heteroscedasticity, and cross-sectional and time-series correlation using a two-way cluster at the firm and year level (Petersen, 2009).

- ***, **, * Statistical significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

| Dependent variable = DACi,t | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted sign | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

| Coef. | t-value | Coef. | t-value | Coef. | t-value | Coef. | t-value | ||

| Constant | 0.00 | [0.31] | 0.00 | [0.21] | 0.01 | [0.45] | 0.00 | [0.23] | |

| Covi,t | ? | 0.01 | [1.94]* | 0.01 | [1.47] | −0.01 | [−2.82]*** | −0.01 | [−2.88]*** |

| MBRi,t | ? | 0.01 | [1.94]* | ||||||

| Covi,t × MBRi,t | ? | −0.03 | [−2.28]** | ||||||

| MBR_Lowi,t | ? | −0.00 | [−1.39] | ||||||

| Covi,t × MBR_Lowi,t | ? | 0.01 | [2.76]*** | ||||||

| LoanConi,t | ? | 0.01 | [1.94]* | ||||||

| Covi,t × LoanConi,t | ? | −0.03 | [−1.92]* | ||||||

| LoanCon_Lowi,t | ? | −0.00 | [−1.13] | ||||||

| Covi,t × LoanCon_Lowi,t | ? | 0.01 | [2.91]*** | ||||||

| ROAi,t | + | 0.12 | [6.53]*** | 0.11 | [6.47]*** | 0.11 | [6.45]*** | 0.11 | [6.39]*** |

| Sizei,t | + | −0.00 | [−1.20] | −0.00 | [−1.15] | −0.00 | [−1.27] | −0.00 | [−1.23] |

| Levi,t | + | 0.02 | [5.00]*** | 0.02 | [5.14]*** | 0.02 | [4.84]*** | 0.02 | [5.00]*** |

| Loss_Di,t | − | −0.01 | [−3.46]*** | −0.01 | [−3.48]*** | −0.01 | [−3.37]*** | −0.01 | [−3.34]*** |

| BoardOwni,t | + | −0.02 | [−2.68]*** | −0.01 | [−2.65]*** | −0.01 | [−2.65]*** | −0.01 | [−2.62]*** |

| IMR_MBRi,t | −0.01 | [−1.82]* | −0.01 | [−1.63] | |||||

| IMR_LCi,t | −0.01 | [−1.66]* | −0.00 | [−1.40] | |||||

| Year Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | Included | |||||

| Industry Fixed Effects | Included | Included | Included | Included | |||||

| Difference between Cov and Cov × MainBank | 0.04 | [2.21]** | 0.03 | [1.85]* | |||||

| Difference between Cov and Cov × MainBank_Low | −0.02 | [−2.90]*** | −0.02 | [−3.05]*** | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.047 | |||||

| N | 17,490 | 17,490 | 17,940 | 17,490 | |||||

- DACi,t denotes the discretionary accruals, as measured by the regression model suggested in Kasznik (1999); MBR_Lowi,t and LoanCon_Lowi,t are dummy variables that equal one if firm i is placed below the first tertile of MBRi,t and LoanConi,t in year t and zero otherwise, respectively; Loss_Di,t is a dummy variable that equals one if firm i reports a net loss in year t and zero otherwise; BoardOwni,t is the percentage of firm shares held by board members; IMR_MBRi,t and IMR_LCi,t are the inverse Mills ratios obtained from probit estimations of Equation (1) using MBRi,t–1 and LoanConi,t–1 as independent variables, respectively; and other variables are defined in Appendix I. All t-statistics are corrected for heteroscedasticity, and cross-sectional and time-series correlation using a two-way cluster at the firm and year level (Petersen, 2009).

- ***, **, * Statistical significance at the 1, 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively.

Appendix I

Variable definitions

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Main analysis | |

| Covi,t | A dummy variable that equals one if debt covenants exist in loan contracts for firm i in year t and zero otherwise |

| MBRi,t −1 | The percentage of loans financed from the main bank to total loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1. We define the main bank as the largest lender for firm i in year t−1 |

| LoanConi,t −1 | The Herfindahl–Hirschman index of loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1, calculated as the sum of the squares of loans from each bank as a percentage of total loans |

| ROAi,t −1 | The net income before extraordinary items for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets |

| Sizei,t −1 | The natural logarithm of total assets for firm i in year t – 1 |

| Agei,t −1 | The natural logarithm of the number of years firm i has been established at the fiscal year end t−1 |

| MtBi,t −1 | The market-to-book ratio at the fiscal year end for firm i in year t – 1 |

| Currenti,t −1 | The ratio of current assets to current liabilities at the fiscal year end for firm i in year t – 1 |

| PPEi,t −1 | The amount of plant, property and equipment (PPE) for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets |

| SAF_Di,t −1 | A dummy variable that equals one if the value of SAF2002 (Shirata, 2003) for firm i in year t−1 is lower than 0.68 and zero otherwise. SAF2002 = 0.01036*(Retained Earnings/Total Assets*100) + 0.02682*(net earnings before taxes/Total Assets*100)-0.06610*(Inventories*12/Sales)-0.02368*(Interest expenses/Sales*100)+0.70773. The discrimination point is 0.68 |

| Levi,t −1 | The amount of total liabilities for firm i in year t−1, scaled by lagged total assets |

| Interesti,t −1 | Weighted average interest rates on loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1 (see Appendix II) |

| Maturityi,t −1 | Weighted average maturity of loans for firm i at the fiscal year end t−1 (see Appendix II) |

| FinOwni,t −1 | The percentage of firm shares held by financial institutions for firm i at the fiscal year end t – 1 |

| MBR_Ni,t −1 | The percentage of loans from the main bank to total loans for firm i in year t−1. Available since 2006, Nikkei-Cges, Item Code: RTO_TPBK_D |

| MBOwn_Ni,t −1 | The percentage of shares held by the main bank for firm i in year t−1. Available since 2006, Nikkei-Cges, Item Code: RTO_TPBK |

| MBOutside_Ni,t −1 | A dummy variable that equals one if firm i has outside directors from its main bank in year t−1 and zero otherwise. Available since 2006, Nikkei-Cges, Item Code: IDMBRTO |

| Additional tests | |

| DACi,t | The discretionary accruals for firm i in year t, as measured by the regression model suggested in Kasznik (1999) |

| MBR_Lowi,t (LoanCon_Lowi,t) | A dummy variable that equals one if firm i is placed below the first tertile of MBRi,t (LoanConi,t) in year t and zero otherwise |

| Loss_Di,t | A dummy variable that equals one if firm i reports a net loss in year t and zero otherwise |

| BoardOwni,t | The percentage of firm shares held by its board members for firm i at the fiscal year end t |

| IMR_MBRi,t(IMR_LCi,t) | The inverse Mills ratio obtained from probit estimation of Equation (1) using MBRi,t (LoanConi,t) as independent variables, respectively |

Appendix II

Measurement of loan interest and loan maturity

In the Japanese reporting environment, the details of each loan contract are rarely disclosed in a public manner. Alternatively, we use information in firm’s annual security reports to measure average loan interest and loan maturity for each firm-year observation. For the interest rate (Interest), we calculate weighted average interest using information in ‘supplementary schedules on borrowing loans’: that is, the balances and average interest rates for (i) short-term loans, (ii) current portion of long-term loans and (iii) long-term loans. The sum of the products of these three loan components (i.e., future average loan interest expenses) are divided by total loan amounts at the fiscal year end.

References

- The Ministry of Finance in Japan required issuers to include several covenants in their unwarranted bonds for securing and developing bond markets during the 1980s. However, the regulation was repealed in 1995 and it became much rarer to use covenants in corporate bonds. On the other hand, the practice has gradually spread to the loan markets since the 1990s and now covenants are largely used for private loan agreements in the Japanese context. Consistently, our collected data show that there are 105 firm-years of bond covenants, which is much less than the 2,596 firm-years of loan covenant observations.

- This is the case even for cross-country research. As discussed in Hong et al.(2016), the coverage of Dealscan, a popular commercial debt contract database, is sparse particularly for countries outside the United States. Although prior literature uses Japanese debt contracts as a portion of international samples, the coverage is significantly limited.

- Prior studies largely focus on Western countries including the US, the UK and Australia. Moir and Sudarsanam (2007) examine debt covenants in the UK and Ramsay and Sidhu (1998) and Mather and Peirson (2006) investigate Australian firms. Yet, the sample in studies outside the US is substantially limited and based on questionnaire and interviews.

- We check the data coverage by collecting all debt contract data recorded in Dealscan for the period 2004–2013. We obtain 20,188 debt contracts for 62 countries in total and find that 79.3 percent of these are for US firms. Covenant data could be more limited outside the US because of the lack of requirements on loan documents from central reporting agencies akin to the US SEC in most countries (Hong et al., 2016). Because Japanese financial services agencies do not require such documents, data has to rely on manual collection.

- For example, debt covenants that require borrowers to maintain a certain level of interest coverage are well explained under the incomplete contracting perspective. This is because there are more direct alternatives for restricting excessive debts that the agency perspective primarily concerns (Christensen et al., 2016).

- We confirm that all covenants are included in loan contracts, whereas 64 firm-years also have covenants for their bonds. Yet, we cannot distinguish types of each loan because most firms disclose their information through the simple word ‘loan’, which makes it difficult to understand the details of loan contracts with covenants, such as loan size, maturity and the name of financial institutions. Consequently, it is difficult in Japan to investigate debt covenants at the loan level, which makes us use firm-years rather than loan-years as a sample.

- The Japanese Ministry of Finance required issuers to include covenants in their unwarranted bonds for securing and developing bond markets during the 1980s. In particular, the regulation strongly encouraged companies to include some or all of following covenants depending on bond rating: (i) restrictions on providing collateral, (ii) maintenance of net assets, (iii) restriction on dividends, and (iv) maintenance of accounting earnings.

- Specifically, we document the number of covenants used for each firm-year as follows: 13.8 percent include only one item; 61.2 percent include two items; 16.9 percent include three items; and 8.1 percent of our sample include more than three items.

- We further investigate the subsequent period of violating firms and find that only 24 firm-years of those were consequently delisted from the stock exchanges, which require listing firms to exceed their assets over debts. We note that these delisted firms are eliminated from our empirical tests as we use a lagged regression model.

- See also Billett et al.(2004) and Graham et al.(2008) for the determinants of debt covenants in the US context.

- Although we predict that debt covenants and main bank governance are substitutable, it does not necessarily indicate that they are mutually exclusive. As the main bank system does not fully disappear (Arikawa and Miyajima, 2015), both debt covenants and main bank monitoring can coexist at the firm level in combination.

- Specifically, we use the words ‘条項’, and ‘コベナンツ’ in Japanese. Furthermore, to assess coverage, we also use the words ‘財務特約’ and ‘財務上の特約’ (financial special agreements) as Japanese regulations had used these words to express covenants in unwarranted bonds during the 1980s. However, we confirm that this does not materially result in additional observations on loan covenants. We also check our coverage using Dealscan and find that only 24 debt contracts are recorded for Japanese firms from 2004 to 2013.

- Shirata (2003) develops a model for predicting bankruptcy using Japanese firm observations. SAF_D indicates a ‘distressed’ firm which is more likely to be bankrupt (see Appendix I).

- A challenge in analysing main banks is the specification of the main bank for a firm. Therefore, we use aggregated shares owned by financial institutions. We come back to this issue in Section 4.2.

- Although the database records unique data for corporate governance in Japanese listed firms, the coverage is relatively sparse compared to FinancialQUEST used in the previous section.

- We estimate the predicted probability without MainBank because defining and omitting suspicious observations based on Equation (1) indicates refinement of model fitting by its nature, which is in favour of our hypothesis testing. We confirm that our results do not change when we estimate the predicted probability including MainBank.

- To account for the consistency in the distribution of error terms between our system of equations, we estimate Equation (1) as a Probit model for the second stage regression.

- Prior studies have proposed a number of proxies for accounting conservatism. However, Garcia Lara et al.(2009) argue that increases in accounting conservatism are driven by discretionary accruals. Thus, we regard conservative accounting as represented by lowering earnings and use discretionary accruals. For model specification, we do not primarily follow Kothari et al.(2005) because we include ROA as a control variable in Equation (2). We find that the results do not change materially when we use discretionary accruals based on the Jones (1991) and Kothari et al.(2005) models.

- We compute two inverse Mills ratios: one is based on estimation using MBR and the other is based on regression using LoanCon. To avoid redundancy, we do not report the results for the first stage probit regressions, which are very similar to those in Table 4.

- We note that, in contrast to columns (1) and (2), the estimated coefficients on Cov are negative and significant in columns (3) and (4). However, this provides similar implications as columns (1) and (2) and suggests that covenants are more likely to result in lower discretionary accruals for firms of MainBank_Low = 0, that is, in the presence of not-weak relations with main banks.