Does legal protection affect firm value? Evidence from China’s stock market

Abstract

We examine the question of whether firms derive value in areas with higher legal protection by studying how the difference among regional legal protection levels affects capital market reactions to firms receiving administrative penalty in China. The results show that the level of legal protection has a positive effect on the market reaction to administrative penalty announcements, and the effect is attenuated by non-state ownership. Furthermore, we find evidence of higher efficiency of law enforcement in regions with higher level of legal protection.

1 Introduction

The misrepresentation of a listed company refers to misconduct in which the offender violates the securities law by providing false records or misleading statements on material events during securities issuance or transactions, or material omissions and improper disclosures. It is widely acknowledged that civil litigation defends investors’ rights through misrepresentation supervision of listed companies, and the legal protection of minority investors improves firm valuation in developed economies (La Porta et al., 2002). Nevertheless, much of the literature that considers this mechanism does not apply to emerging markets such as that of China. Allen et al.(2005) consider China a counterexample to the law and finance literature in general, and Layton (2008) specifically indicates that private enforcement through civil litigation faces numerous barriers in the current legal environment in China. However, in the past twenty years China’s legal environments to protect investors have improved substantially. For example, Chen et al.(2010) and Berkman et al.(2010) both document the substantial development of the Chinese institutional environment to become more investor-friendly. On the other hand, huge differences exist in economic development, financial markets and also legal environments among the different regions in China (Hasan et al., 2009; Xu, 2011). Our aim is to examine whether different regional levels of investor protection influence firm valuation in China.

The unique institutional arrangement in the Chinese capital market provides an opportunity to examine the relationship between firm value and the level of legal protection. On 15 January 2002, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued ‘Notice of the Supreme People’s Court on Relevant Issues of Filing of Civil Tort Dispute Cases Arising from Misrepresentation in the Capital Market’ (hereinafter referred to as ‘the 1.15 Notice’), entitling the Intermediate People’s Court to accept civil claim cases of misrepresentation involving listed companies. However, the 1.15 Notice stipulates that only cases with the administrative penalty decision of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) can be accepted. In other words, the investors’ civil action must be preceded by administrative punishment. Theoretically, the stock price is expected to change negatively on announcement of the administrative punishment. In view of the huge differences in the judicial environment and law enforcement among the various regions in China, investors’ expectation of transparency of civil litigation in the case of misrepresentation will vary as well. For firms in areas with higher investor protection, investors would expect a relatively transparent litigation process and a more certain result for civil compensation, which would reduce the uncertainty used in firm valuation by the stock market. Therefore, we focus on the market reaction to the administrative punishment among different legal protection levels.

Data from misrepresentation cases of Chinese listed companies between January 2000 and June 2016 offer evidence of the relationship between level of legal protection and firm value. The main finding is that the level of regional legal protection has a significant positive effect on the capital market reaction. The higher the level of regional legal protection, the larger the cumulative abnormal return. We further find that non-state ownership of listed companies attenuates the above relationship, which is consistent with the explanation that state ownership has more influence on the legal enforcement system. In addition, we trace 224 cases of civil litigation for misrepresentation and manually collect data with a sample period of more than 16 years. It is found that the level of legal protection has a positive effect on the efficiency of law enforcement. In regions with higher levels of legal protection, the average length of a civil case is significantly shorter (6.2 months), as is the length of closing a civil case (11.18 months).

This paper contributes to the existing literature in the following ways. First, given the differences in levels of legal protection among the various regions in China, this paper provides empirical evidence of economic consequences for selective law enforcement in China’s capital market, which to the best of our knowledge, is still very limited in law and finance research in emerging markets. Second, we find that the difficulty in enforcing securities laws in China stems from the weak judicial environment rather than from the absence of civil law. Our findings add more empirical evidence to previous research such as Huang (2013) through quantitative analysis of civil litigation cases. Third, the research demonstrates the complementary relationship between administrative regulation and the legal litigation mechanism, which helps to settle the controversy over their relationship. Shleifer (2012) finds that administrative regulation is an effective substitute for the lawsuit mechanism, while Helland and Klick (2013) claim that the relationship between administrative regulation and the legal litigation mechanism is more of cooperation than substitution. Our study supports Helland and Klick (2013) and demonstrates that, in the absence of an effective legal litigation mechanism, the effectiveness of administrative regulation is constrained in emerging capital markets such as China.

2 Literature review and research hypotheses

2.1 Legal protection and firm valuation

2.1.1 Supervision of misrepresentation

Misrepresentation of listed companies is the most severe violation of information disclosure regulations in the Chinese securities market. Civil litigation and administrative supervision are commonly adopted tools for discouraging misrepresentation. One view is that administrative regulation and legal litigation are mutually substitutable. La Porta et al.(2000) find that administrative regulation is an effective substitute for inefficient judicial enforcement in emerging markets with a weak judicial system. More emphasis should be put on the importance of public enforcement than on private enforcement of securities laws (La Porta et al., 2006), and public enforcement can better explain the development of financial markets worldwide than can private enforcement (Jackson and Roe, 2009; Xu et al., 2019). Shleifer (2012) shows that the effectiveness of administrative regulations is negatively correlated with that of legal proceedings in investor protection and corporate governance. Helland and Klick (2007) study 130 class action lawsuits involving insurance companies during the period from 1992 to 2002. They conclude that administrative supervision combined with legal litigation effectively encourage compliance. Humphery-Jenner (2013) examines the strict laws and weak administrative regulations in relation to market manipulation activities in China. He demonstrates that without strong administrative regulations, even a sound legal system is ineffective.

Although the above two views disagree on whether administrative supervision could substitute legal protection, they both support that a sound legal environment can safeguard the development of a transparent and strong financial market.

2.1.2 Civil litigation and the financial market

A legal system which favours investor rights will encourage investment in companies within the system, thereby promoting the development of the financial market. Laws also constitute a transaction environment for companies. A legal system not only safeguards intellectual property and other assets of a company, but also establishes the code of conduct that every market participant must follow.

On the one hand, a sound legal system can enhance investor confidence to improve firm value, which is reflected in financing costs and market liquidity. Laeven and Majnoni (2003) examine differences in judicial efficiency in various countries and find that those countries with higher judicial and enforcement efficiency have lower loan interest rates. Hasan et al.(2009) provide empirical evidence that the development of legal environments is associated with financial deepening and also stronger economic growth rates using panel data for the Chinese provinces. Wang et al.(2016) conduct research on litigation risk, legal environment and debt costs. Their research shows that the potential litigation risks of enterprises are positively related to the cost of debt financing, and this relationship is more obvious in regions where litigation costs are high. Luo et al.(2016) study the impact of regional law enforcement level on credit markets, capital markets and financial marketisation. Their overall results show that the improvement of regional law enforcement not only increases bank credit scale and promotes capital markets but also improves the degree of marketisation of the financial industry.

On the other hand, a sound legal system can provide an institutional guarantee and monitor the market behaviour of companies, thereby decreasing uncertainty related to litigation costs. Laws can serve as deterrents, discouraging corporate misconduct and ensuring the benign development of financial markets. Pan et al.(2015) examine the relationship of corporate litigation risk, judicial local protectionism and enterprise innovation. Their results indicate that local judicial protectionism impacts the results of corporate litigation and thus affects the innovation activities of enterprises. Cao et al.(2017) measure the independence of the local judiciary and court president (judge) exchanges in the High People’s Court in 2008. They use the difference-in-differences (DID) method to test the influence of judges’ exchanges on the legal enforcement of regulation violations of listed companies, and demonstrate that the improvement of judicial independence strengthens investor protections through its influences on the regulatory authorities, investors and companies, and reduces tunnelling through related party transactions.

2.1.3 Legal protection and market reactions to announcement of misrepresentation penalties

In China, administrative supervision involving third parties such as the sponsor system, independent directors, external auditors and CSRC examination is consistent across all regions. However, the level of law enforcement by local courts varies due to the local juridical system. Since local courts are established by and responsible for the People’s Congresses at the same level, the local judicial system is greatly influenced by the local government. As specified by the 1.15 Notice, nearly 50 Intermediate People’s Courts, which handle civil litigation for misrepresentation, are in eastern, central and western China. Across these regions, the administrative capacity of the government, the relationship between the government and the market, the level of economic and social development, the efficiency and fairness of the judiciary, and the level of legal compliance are not consistent, which inevitably results in differences in the level of legal protection. In the context of a unified regulatory environment, such regional differences in level of legal protection provide an opportunity to test the influence of legal protection on financial markets.

H1: Capital market reaction to announcement of misrepresentation penalties is positively related to the level of legal protection. The higher the level of legal protection, the more positive the market reaction and vice versa.

2.2 The influence of state ownership: incremental effect

For historical and political reasons, state-owned enterprises have a close relationship with the government, which not only induces misrepresentation but also hinders any settlement. As for the court, local Chinese courts lack sufficient independence. The intention of their establishment was not to constrict the power of local governments, but to act as one of the administrative units within the political system. Therefore, the authority of the courts is granted by the government rather than by law. Whether to use the law to resolve disputes and to what extent the law is used depend largely on the government.

As for the local government, decentralisation reforms have aroused local governments’ enthusiasm for economic development and local governments ‘initiate, negotiate, implement, divert, and resist reforms, policies, rules, and laws’ (Xu, 2011). In civil compensation cases of misrepresentation, local governments may avoid civil compensation litigation through interference with the local courts in order to protect state-owned enterprises (SOEs), resulting in more uncertainty for SOEs to follow through with compensation obligations, especially in areas with lower levels of legal protection (Chen et al., 2009).

As for regulation, selective regulation remains an issue that has not yet been settled. Regulators consciously and proactively deregulate state-owned enterprises, which not only undermines the impact of law enforcement but also encourages the opportunistic behaviour of potential violators. Research has provided evidence that the nature of property rights of debtors affects the relationship between litigation risk and the cost of debt financing. Specifically, if the debtor is a state-owned enterprise, the debt litigation risk is not fully included in the pricing of the debt contract (Wang et al., 2016).

H2: The effect of the level of legal protection on the capital market response will be more attenuated for non-SOEs than for SOEs.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample selection and data sources

This paper uses the sample of all A-share companies that were subject to administrative sanctions issued by the CSRC and its agencies for misrepresentation from 1 January 2000 to 30 June 2016. We eliminate the following four types from our sample: (i) corporate stocks that stopped trading before the penalty announcement date and continued suspension of trading until the penalty announcement date; (ii) corporate stocks that stopped trading less than 15 trading days after the penalty announcement date and continued suspension for more than 1 month; (iii) corporate stocks whose regression coefficients β1 do not pass the t-test at the 5 percent level; (iv) corporate stocks whose fitness in regression results is less than 10 percent according to the stock normal return evaluated by the market model. By referring to the research of Xin et al.(2013), we define misrepresentation penalty announcements as administrative penalty announcements containing ‘fictitious profit’, ‘fictitious asset’, ‘postponing disclosure’, ‘false record (misleading statement)’, and ‘major omission’. We obtain penalty data from Chinese Listed Companies Violation Database in China Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR). After eliminating the four types of data described above, the final sample size is 224.

Table 1 illustrates the geographical divergence between the distribution of punished companies and that of A-share companies. The distribution divergence indicates that, in contrast to the regions with low levels of legal protection such as northwest and southwest China, the proportion of misrepresentation among listed companies is relatively less in regions with high levels of legal protection such as eastern and northern China.

| Region | No. of punished companies | Proportion in sample | Regional proportion of A-share companies | Distribution divergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern China | 24 | 10.71% | 20.54% | −47.86% |

| Eastern China | 73 | 32.59% | 35.34% | −7.78% |

| Northeast China | 12 | 5.36% | 5.78% | −7.27% |

| Central China | 24 | 10.71% | 8.90% | 20.34% |

| Southern China | 47 | 20.98% | 16.90% | 24.14% |

| Northwest China | 17 | 7.59% | 5.07% | 49.70% |

| Southwest China | 27 | 12.05% | 7.47% | 61.31% |

| Total | 224 | 100% | 100% | – |

3.2 Variable measurements

3.2.1 Dependent variable: cumulative abnormal return (CAR)

By referring to prior literature (Berkman et al., 2010), we define the event day as the announcement date of the administrative penalty decision and use a standard Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)-adjusted return model to calculate the cumulative abnormal return. The event window is seven days (CAR[−3, +3]).

3.2.2 Independent variables

Following Pan et al. (2015), we use the score of judicial transparency of the Intermediate People’s Court in each province, municipality or autonomous region to measure the level of law protection. If the score is higher than the sample median, the law protection level variable takes a value of 1. Otherwise, the variable is 0.

We use the nature of controlling shareholders to measure the nature of property rights. If the controlling shareholder is a non-SOE, the nature of property rights variable takes a value of 1. Otherwise, the variable is 0.

3.2.3 Control variables

Following Chen et al.(2009) and Xin et al.(2013), we use the following control variables: share proportion of controlling shareholders (Ctrpct), company size measured by the natural logarithm of total assets (Size), profitability (Roe), financial leverage (Lev), and the divergence between voting rights and ownership (Divg). Industry and year effects are also controlled for.

Tables 2 and 3 show the definitions and descriptive statistics of the main variables. Correlation coefficients are less than 0.3 (unlisted), so the multicollinearity problem is not a serious concern.

| Variable | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| CAR of single stock | CARit | Cumulative abnormal return in the event window [−3, +3] calculated by market model |

| Law protection | Lawprotect | Dummy variable: 1 if the judicial transparency score is higher than the sample median; 0 otherwise |

| Nature of property right | Private | Dummy variable: 1 if the controlling shareholder is non-SOE; 0 otherwise |

| Ownership ratio of controlling shareholder | Ctrpct | The most recent controlling shareholder’s share proportion before the event day |

| Company size | Size | The natural logarithm of the most recent total assets before the event day |

| Profitability | Roe | The most recent earnings divided by total equity before the event day |

| Financial leverage | Lev | The most recent total liability divided by total assets before the event day |

| Divergence | Divg | Ratio of voting rights and ownership of controlling shareholder |

| Industry | Industry | Industry dummy variable |

| Year | Year | Year dummy variable |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR[−3,+3] | 224 | −0.000 | 0.069 | −0.280 | 0.217 |

| Lawprotect | 224 | 51.597 | 16.550 | 0.000 | 76.500 |

| Private | 224 | 0.679 | 0.468 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Ctrpct | 224 | 0.318 | 0.157 | 0.057 | 0.900 |

| Size | 224 | 21.014 | 1.266 | 16.219 | 24.933 |

| Roe | 224 | −0.017 | 0.498 | −2.214 | 1.228 |

| Lev | 224 | 0.673 | 0.615 | 0.070 | 0.968 |

| Divg | 224 | 4.953 | 6.384 | 1.000 | 23.980 |

3.3 Regression model

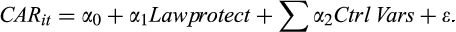

(1)

(1)We focus mainly on the sign and significance level of the coefficient α1. If α1 is significantly positive, the market reaction to the penalty announcement will be more positive for companies located in regions with a higher level of legal protection, which means a higher level of legal protection may increase firm value.

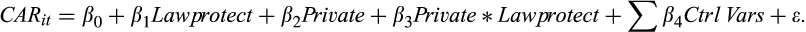

(2)

(2)We focus on the sign and significance level of the coefficient β3. If β3 is significantly negative, the level of legal protection would have less influence on stock market reaction of non-SOEs than that of SOEs.

4 Empirical results

The empirical results are divided into four parts: the cross-sectional difference in CARit, multiple regression results of the standard event study, and the robustness test of the measurement of key variables and the possibility of endogeneity.

4.1 Cross-sectional difference in cumulative abnormal returns

Table 4 shows the result of the value of all-sample CARit as well as the difference between high versus low levels of legal protection. The CARit in the event window [−3, +3] of the punished companies is −0.0004 for the entire sample and is not significant from zero, which indicates that the capital market does not have a significant negative reaction to the announcement of an administrative penalty for misrepresentation. However, when we group the sample by the level of legal protection, the CARit of punished companies is 0.78 percent in regions with a higher level of legal protection and −0.87 percent in regions with a lower level of legal protection. The mean difference between the two groups is −1.65 percent and is significant at the 10 percent level, which provides preliminary evidence that the market reaction to administrative punishment will be more positive if the level of legal protection is higher.

| Obs. | Mean of CARit | Mean/Mean difference t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | 224 | −0.0004 | −0.0875 |

| Lower legal protection group | 110 | −0.0087 | −1.7583* |

| Higher legal protection group | 114 | 0.0078 |

- *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

To deal with individual heterogeneity of stocks, we further calculate the CART on each day during a longer event window [−15, +15] and observe the relationship between the level of legal protection and the short-term market reaction more directly. The average CART is negative in the [−15, +15] period. The sample is also divided into two groups: companies in regions with higher and lower levels of legal protection. It is found that the average CART is positive and does not fluctuate significantly around the event day for companies in regions with relatively higher levels of legal protection. However, for companies in regions with relatively lower levels of legal protection, the average CART is negative, and the market reaction becomes more negative after the event day.

4.2 Regression results

Table 5 displays the regression results of CAR [−3, +3] and the independent variables. We control industry and year effects and use a white correction method for heteroskedasticity. In column (1), only the independent variable Lawprotect is included and its coefficient is 0.001, which is significant at the 5 percent level. In column (2), we add control variables into the model, and the coefficient of Lawprotect remains significant. In columns (3) and (4), we study companies in regions with lower and higher levels of legal protection, respectively. Column (3) shows results of companies in regions with lower levels of legal protection, the coefficient of Lawprotect is 0.002, which is significant at the 5 percent level. However, in the sub-sample of companies in regions with higher levels of legal protection, the coefficient of Lawprotect is 0.001, which is not significant statistically. Empirical results suggest that the market response of the administrative penalty announcement for misrepresentation is affected by the level of legal protection, so hypothesis H1 is supported.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawprotect | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.002** | 0.001 | 0.002*** |

| (2.54) | (2.43) | (2.36) | (0.64) | (3.73) | |

| Private | 0.057* | ||||

| (1.72) | |||||

| Law × Private | −0.001** | ||||

| (−2.11) | |||||

| Ctrpct | 0.054 | −0.008 | 0.082 | 0.047 | |

| (1.54) | (−0.12) | (1.35) | (1.36) | ||

| Size | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.011 | −0.003 | |

| (−0.72) | (0.62) | (−1.24) | (−0.68) | ||

| Roe | 0.009 | −0.001 | 0.014 | 0.009 | |

| (1.01) | (−0.09) | (0.82) | (1.05) | ||

| Lev | −0.012* | −0.006 | −0.014 | −0.012* | |

| (−1.67) | (−0.54) | (−1.02) | (−1.84) | ||

| Divg | −0.000 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.000 | |

| (−0.25) | (−0.46) | (0.57) | (−0.13) | ||

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 224 | 224 | 110 | 114 | 224 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.024 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.046 | 0.043 |

- *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

In column (5), we further examine the interactive effect of the nature of property rights on the relationship between the level of legal protection and the market response. The coefficient of the independent variable Lawprotect is 0.002, and its significance level increases from 5 to 1 percent. The coefficient of the interaction term is −0.001, which is significantly negative at the 5 percent level. The result suggests that property rights do play a role and the influence is attenuated by non-SOEs.

4.3 Robust tests

We also conduct a series of robustness tests. First, we use a longer event window of 7 days before and after the event day (i.e., CAR [−7, +7]) to calculate the market reaction to the penalty announcement of misrepresentation. As shown in column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient of Lawprotect is 0.001 and significant at the level of 1 percent, which reveals a positive relationship between the level of law protection and the market reaction. Moreover, the coefficient of interaction term is still negative. Considering that the penalty information may be leaked before the event day, we also use CAR [0, +10] as the dependent variable and control CAR [−10, 0] as an independent variable. As shown in column (2) of Table 6, the relationships still exist, and the R2 increases to 21.6 percent.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | CAR[−7, +7] | CAR[0, +10] | CAR[−3, +3] | CAR[−3, +3] |

| Lawprotect | 0.001*** | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | |

| (2.93) | (3.03) | (4.04) | ||

| Law × Private | −0.001** | −0.002** | −0.001* | |

| (−2.17) | (−2.05) | (−1.96) | ||

| Lawprot_prov | 0.002*** | |||

| (3.23) | ||||

| Law × priv_prov | −0.001* | |||

| (−1.67) | ||||

| CAR[-10, 0] | −0.204*** | |||

| (−2.81) | ||||

| Mktindex | −0.004 | |||

| (−1.36) | ||||

| Private | 0.048* | 0.067 | 0.047 | 0.055* |

| (1.90) | (1.38) | (1.33) | (1.65) | |

| Ctrpct | 0.011 | −0.030 | 0.048 | 0.050 |

| (0.43) | (−0.62) | (1.37) | (1.46) | |

| Size | −0.003 | 0.006 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| (−0.91) | (0.95) | (−0.65) | (−0.63) | |

| Roe | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| (0.41) | (−0.07) | (1.11) | (1.12) | |

| Lev | −0.004 | −0.008 | −0.013* | −0.013* |

| (−0.90) | (−0.75) | (−1.83) | (−1.96) | |

| Divg | −0.000 | −0.002** | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−0.55) | (−2.24) | (−0.05) | (−0.17) | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 224 | 224 | 224 | 224 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.160 | 0.216 | 0.037 | 0.045 |

- *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

Second, we change the measurement of the key independent variable Lawprotect. In Table 5, we use the average score of transparency of all Intermediate People’s Courts in provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions. In Table 6, we use the average score of People’s Court of both the Intermediate and High People’s Court. The variable and the interaction term are denoted by ‘Lawprot_prov’ and ‘Law × priv_prov’, respectively. As shown in column (3), the relationships still exist despite the significance level of the interaction term (Law × priv_prov) dropping from 5 to 10 percent.

Finally, we examine the endogeneity of the variables. The relationship that we have observed between the level of legal protection and the short-term capital market reaction may be a pseudo-correlation due to a common driven factor, the degree of marketisation. Therefore, we add marketisation into the regression model to alleviate the possible problem. Marketisation is measured by the marketisation index of provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions compiled by Fan et al.(2011), and the data after 2009 are replaced by data in 2009. In column (4) of Table 6, we find that the coefficient of marketisation degree (Mktindex) is not significant, and the variables Lawprotect and interaction term remain robust.

4.4 Heckman two-step sample selection model

The empirical result coefficients could be overestimated or underestimated without considering potential self-selection bias that might arise from the fact that firms self-select their operating location based on lower or higher level of legal protection. Heckman (1979) focuses on self-selection concerns and provides the Heckman regression to alleviate self-selection bias by introducing the inverse Mill’s ratio into the regression model.

In the first stage, we estimate a probit regression in which the likelihood of higher level of legal protection, denoted by Pr(higher legal protection), is regressed on a set of firm-specific variables and region variables that might influence the legal protection choice of different companies. For firm-specific variables, the probit model included the size of company (Size), the profitability of equity (Roe) and whether controlling shareholders are state-owned or not (Private). For the regions variable, we use the treaty port dummy variable following Keller et al.(2017). They examine the effect of treaty ports on internal trade and the law system shaped in China during the period 1842–1943, and find that these ports were not only the conduits of goods but also the carriers of western influence by setting up western courts and legal systems. For example, the one area in which western presence was particularly important was the customs system, which from 1859 onwards operated under the auspices of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service (CMCS). Therefore, while considering the difference in the level of legal protection among regions, the legal traditions and level denoted by the treaty port probably play an important role in the evolution of legal protection. Therefore, we use the variable Treatyport as one of the determinants for higher level of protection. Specifically, if a company registers in a province that was one of the 15 treaty ports during the Qing Dynasty, the variable Treatyport equals 1, and 0 otherwise.

In the second stage, we estimate our main regressions to deal with potential self-selection biases. We follow the two-stage treatment effect procedure of Heckman (1979) to compute the inverse Mills ratio, denoted by Lambda, from the first-stage probit estimate, and then include Lambda in the second-stage regressions.

Table 7 reports the results that consider the self-selection biases. The coefficient of Lawprotect is 0.002, which remains positively significant at the 1 percent level, and the coefficient of the interaction term also remains negatively significant at the 5 percent level. Both year and industry effect are controlled.

| First-stage probit regression | Heckman approach with inverse Mills ratio (Lambda) included | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Dependent variable | Pr(higher legal protection) | CAR[−3, +3] |

| Lawprotect | 0.002*** | |

| (4.33) | ||

| Private | 0.176 | 0.061* |

| (0.84) | (1.84) | |

| Law × Private | −0.001** | |

| (−2.09) | ||

| Size | 0.027 | −0.002 |

| (0.34) | (−0.47) | |

| Roe | 0.197 | 0.012 |

| (1.00) | (1.39) | |

| Ctrpct | 0.045 | |

| (1.28) | ||

| Lev | −0.014** | |

| (−2.11) | ||

| Divg | −0.000 | |

| (−0.26) | ||

| Treatyport | 1.931*** | |

| (8.66) | ||

| Lambda | 0.024* | |

| (1.95) | ||

| Industry | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes |

| N | 224 | 224 |

| Pseudo R2/Adj.R2 | 0.3246 | 0.054 |

- *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

5 Further investigation on litigation efficiency

To provide more in-depth and persuasive evidence on the governance mechanism of administrative supervision and legal protection in response to misrepresentation by listed companies, we further examine the effect of the level of legal protection on misrepresentation civil cases, including the severity of misrepresentation by punished companies, the filing rate, the timeliness of filing, and the timeliness of closing. We manually collect data on the timing of misrepresentation, the date on which misrepresentation was disclosed, the announcement date for the administrative penalty, the filing date of civil cases, the closing date of civil cases and the judgment date of civil lawsuits. The data is collected from ‘The courts’ judgments collection of securities civil compensation cases in China’, China Judgments Online, announcements of listed companies on CNINFO, announcements of listed companies on Sina Finance, and so on. Specifically, the case filing rate is defined as the proportion of punished companies filed by civil case in all punished companies. The timeliness of filing a case is defined as the number of months between the announcement date of the administrative penalty and the filing date for a civil case. The timeliness of closing a case is defined as the number of months between the filing date of a civil case and the date of first instance judgment.

The main questions examined in this section are as follows. On the one hand, before a company receives a misrepresentation penalty, does the level of legal protection affect the possibility or severity of the misrepresentation? On the other hand, after a misrepresentation penalty, does the level of legal protection affect the filing rate, the timeliness of filing and the timeliness of closing of civil proceedings?

Between-groups mean difference t-test results are displayed in Table 8. In a decreasing sample of 149 companies due to missing data, 27 listed companies (18.1 percent) suffered the maximum penalty. The proportion of companies suffering the maximum penalty is 23.5 percent (19 companies) in the regions with lower levels of legal protection, while that proportion drops to 11.8 percent (8 companies) in the regions with higher levels of legal protection. The difference between the two groups is 11.7 percent, which is statistically significant at the 10 percent level. Therefore, we infer that misrepresentation is more serious for listed companies in regions with relatively low levels of legal protection.

| Variable | Total sample | Lower legal protection | Higher legal protection | Mean difference t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | ||

| Proportion of companies suffering maximum penalty | 149† | 0.181 | 81 | 0.235 | 68 | 0.118 | 1.854* |

| Proportion of filing of civil litigation | 224 | 0.424 | 118 | 0.467 | 104 | 0.377 | 1.341 |

| Timeliness of filing civil litigation (months) | 95 | 16.96 | 55 | 19.59 | 40 | 13.39 | 2.710*** |

| Timeliness of closing civil litigation (months) | 70 | 19.98 | 41 | 24.71 | 29 | 13.53 | 3.619*** |

- *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively.

- † There are 75 missing variables in the Wind Database of whether the company suffer maximum penalty.

We further compare the filing rate of civil litigation for misrepresentation under different levels of legal protection. As shown in Table 8, no significant difference between groups is observed. The main reason for this may be that the administrative penalty is an important precondition of filing civil litigation for misrepresentation. For companies that have suffered administrative penalties, as long as the investors submit relevant litigation material in accordance with the law, filing requirements of the Court of First Instance will be met. Therefore, Courts of First Instance have relatively few discretionary rights in ‘whether to file a case or not’, which results in insignificant differences in filing rates.

However, Table 8 shows that the timeliness of filing civil litigation is evidently different under different levels of legal protection. In regions where the level of legal protection is relatively low, the average time for filing a case is 19.59 months. In regions where the level of legal protection is relatively high, the average time for filing a case is 13.39 months, which is 6.2 months shorter than the former. The difference of half a year is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. It suggests that a higher level of legal protection helps to address the filing obstacles of civil litigation of misrepresentation and promotes the efficiency of the filing process.

Table 8 also reports the impact of differences in the level of legal protection on the timeliness of closing civil litigation of misrepresentation. In regions with lower levels of legal protection, the average time for closing a case is 24.71 months. However, in regions with higher levels of legal protection, the average time for closing a case is 13.53 months. The difference is 11.18 months, which is also statistically significant at the 1 percent level. This result indicates that the efficiency of closing civil litigation for misrepresentation is significantly higher in regions with higher levels of legal protection. The mechanism is that in regions with greater legal protection, the court has a greater interest in defending the investors’ interests, a higher level of professionalism, and a higher level of transparency in civil litigation. In fact, civil litigation for misrepresentation such as YinGuangXia (SZ.000557) and Hongguang Industry (SH.600083) fully demonstrated the effect of the efficiency of rule enforcement in different regions on the implementation of legal provisions.

It is worth noting that the level of legal protection does not affect the plaintiffs’ success rate in civil litigation. The selective enforcement of local courts intervenes more in the litigation process than in the litigation result. By reading and analysing a large number of court trial documents, we conclude the following possible reasons. An administrative penalty is a precondition for civil litigation in response to misrepresentation of listed companies. Therefore, the listed company is convicted by the court prior to the civil trial for misrepresentation. In most cases, whether the plaintiff wins and is compensated depends mainly on the administrative penalty announcement rather than on the court’s judgment. The failure of the plaintiff in a small number of cases results from the plaintiff’s inability to prove a causal relationship between the investment loss and the misrepresentation, or fail to submit relevant evidence, such as a securities account card and the securities transaction record. This further explains Huang (2013) finding that the compensation rate of civil litigation for misrepresentation is much higher in China than in the United States.

6 Conclusion

The Chinese stock market has experienced rapid growth and it is important to understand the underlying institutions supporting that growth, as argued in recent surveys (Linnenluecke, et al., 2017; Han, et al., 2018; De Villiers and Hsiao, 2018). Misrepresentation is a serious problem in the information disclosure process of listed companies in China. It seriously infringes on the interests of investors and greatly hinders the sound development of the securities market. This paper holds the view that the level of legal protection where the listed companies are located affects the market response to the announcement of administrative penalties for misrepresentation. Specifically, the market reaction is positively related to the level of legal protection. In regions with higher levels of legal protection, investors anticipate less difficulty in civil litigation and a more certain litigation result, which attaches more operating certainty to the listed firms, so the short-term response of the capital market is more positive. However, in regions with lower levels of legal protection, investors expect more difficulty in civil litigation and more uncertain litigation results, which would add much more operating uncertainty to the firms, therefore resulting in a more negative short-term response in the capital market. Additionally, state ownership aggravates the negative reaction of the capital market. Finally, a follow-up study on civil litigation cases of misrepresentation with manually collected data in a sample period of 16 years shows that in regions with higher levels of legal protection, the timeliness of filing and closing is significantly shorter. This provides more direct evidence of the conclusion that legal protection favours investors’ interests, decreases firm operating uncertainty and increases firm value.

The research findings make contributions in two aspects. First, we provide more direct evidence for the relationship between legal protection and firm value. A sound legal system is of great importance to the financial market. Second, we emphasise the importance of the construction of a civil liability system in defending investors’ rights and improving transparency in capital markets. On account of uneven levels of legal protection in different regions, feasible ways to defend investors’ rights are setting up several nationwide professional courts that specialise in securities civil litigation cases, simplifying the procedures for civil litigation, and granting investors the right to choose the court of first instance.

References

- The ‘1.15 Notice’ stipulates the necessity of the decision of the administrative sanction imposed by the CSRC and its agency. On 1 February 2003, ‘Several Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Trial of Civil Compensation Cases Caused by Misrepresentation in the Stock Market’ pointed out that ‘the administrative judgments of the Ministry of Finance, other administrative authorities and the institutions entitled to make administrative penalties or crime judgments from courts’ are also valid preconditions for filing misrepresentation cases.

- Ping An Securities is the sponsor of Wanfu Biotechnology (SZ.300268), found guilty of misrepresentation. For details of prepayment, see http://www.cs.com.cn/sylm/jsbd/201305/t20130510_3978522.html.

- Industrial Securities is the sponsor of Xintai Electric (SZ.300372), found guilty of misrepresentation. For details, see http://www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2017-06/10/c_1121119201.htm.

- http://wenshu.court.gov.cn.

- http://www.cninfo.com.cn.

- http://finance.sina.com.cn.