Long-Term post-merger announcement performance. A case study of Australian listed real estate

Abstract

This study examines the long-term postmerger performance of Australian Real Estate Investment Trusts (A-REITs). The A-REIT sector is used as a case study being less vulnerable to agency issues due to its regulatory structure (Eichholtz and Kok, 2008; Ratcliffe et al., 2009). Research on conventional firms has shown, on average, shareholders are worse off in the long run (Alexandridis et al., 2012). In contrast, we find that shareholders experience significantly positive abnormal returns, after accounting for the financial crisis. This outcome suggests that when managers are restricted with the use of retained earnings and the type of investment, they may be less susceptible to hubris and/or agency issues.

1 Introduction

The postmerger performance of firms has long been the subject of academic debate. Manne (1965) argued that mergers and acquisitions (M&As) should provide for the efficient management of companies, the protection of noncontrolling investors, improved mobility of capital and an efficient allocation of scarce resources. However, research on the long-run performance of acquiring firms in a merger suggests that this may not necessarily be the case (Brown and da Silva Rosa, 1998). Several studies have shown that on average, bidding firm shareholders are worse off in the long run. This calls into question the motivations for M&A activity and suggests that they may be motivated more by agency and/or hubris rather than efficiency considerations (Conn et al., 2005; Ang et al., 2008; Alexandridis et al., 2012).

Agrawal et al. (1992) and Rau and Vermaelen (1998) argue that the market reassesses the acquirer over time as new information regarding the M&A is released. It therefore follows if the acquisition was motivated by manager's self interest and/or overestimation of possible synergistic benefits, this may lead to negative abnormal post-M&A performance. Furthermore, Rau and Vermaelen (1998) and Savor and Lu (2009) argue that manager's may be entrenched by prior performance and therefore overpay for an acquisition. Jensen and Ruback (1983, p. 20) comment ‘these postoutcome negative abnormal returns (ARs) are unsettling because they are inconsistent with market efficiency and suggest that changes in stock prices overestimate the future efficiency gains from mergers’. Campbell et al. (2009) describes this anomaly of postmerger underperformance as troubling because it suggests evidence of weak form market efficiency.

The purpose of this study is to extend on prior research to investigate whether the long-term anomaly holds, within the Australian context. The study employs two methodologies to examine the long-term wealth effects for shareholders. The first is the buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) method, described by Barber and Lyon (1997). The second is based on the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model.1 The research will use the Australian Real Estate Investment Trust (A-REIT) sector as a case study for the examination. The A-REIT sector is chosen because of its significance as an investment vehicle. Furthermore, it provides an opportunity to test the information efficiency of the Australian M&A market, within a controlled sector. Excess returns are calculated over the 1, 2 and 3-year postannouncement event window for A-REIT announcements from January 1996 to December 2012.

Ghosh et al. (2012) argue that the regulatory structure of the REIT industry has critical and noteworthy implications for corporate finance theories and concepts. Eichholtz and Kok (2008) suggest that, due to their regulatory environment, the listed real estate sector may be less vulnerable to agency problems. In particular, there are two regulatory provisions within the A-REIT sector that are relevant to the effectiveness of the market for corporate control. First, A-REITs are required to distribute 100 percent of net taxable income to shareholders to avoid paying income tax at the trust level (tax transparency) (Ratcliffe and Dimovski, 2014). This limits manager's access to retained earnings, and they are therefore reliant on the capital market to raise funds. The limited access to free cash flow and reliance on capital markets should decrease information asymmetries and agency issues (Eichholtz and Kok, 2008; Ratcliffe et al., 2009). Second, the large majority of the A-REITs income must be derived from real estate assets to retain their tax transparency status (EPRA, 2014).2 This restriction has the potential to prevent cross-industry M&As, reducing the manager's options for value destroying diversification motives and empire building (Ghosh et al., 2012).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section two presents the institutional background of A-REITs. Section three summarises the literature and develops the research question. The research methodology and data collection procedures are discussed in section four. The presentation of the results and discussion is provided in part five and finally section six identifies areas for future research along with the concluding comments.

2 A-REIT institutional background

Prior literature shows that REITs provide many useful characteristics and attributes to their investors. They allow liquidity and transparency to property investment (Newell, 2005; Dolvin and Pyles, 2009) not generally available to direct property investment. Additionally, the inclusion of REITs in an investment portfolio can act as a defensive stock (Glascock et al., 2000; Newell and Tan, 2003; Newell, 2005) due to their lower volatility and diversification benefits (Ratcliffe and Dimovski, 2007). The Australian REIT sector is recognised as a world leader in securitised property (Higgins and Ng, 2009) and now comprises an important component of the property market (Parker, 2011). As at March 2015, the A-REIT sector had a market capitalisation of $118.4 billion, which equates to approximately 7 percent of the overall Australian equities market (ASX, 2015). In addition, the A-REIT sector is the second largest REIT regime globally, making up 8.3 percent of the global REIT market (EPRA, 2014).

Newell (2008) highlights the importance of property investment to superannuation funds. The estimated collective worth of Australia's superannuation industry totals $1.93 trillion as at December 2014 (APRA, 2015). Superannuation funds have 8 percent of their assets allocated to real estate, this includes 3 percent directly invested in A-REITs (APRA, 2015). The importance of the A-REIT sector is expected to continue to grow as the retirement investment industry responds to the demands of an ageing population. Reddy (2013) examined the asset allocation of industry superannuation funds and found funds would improve their risk-adjusted returns by increasing their investment allocation in property assets to 21 percent. In addition, a market report by Jones Lang LaSalle (2012) has forecasted real estate allocation by superannuation funds to increase to 25 percent over the next decade. In Australia, approximately 70 percent of investment grade property is securitised. Of this, 46 percent is owned by A-REITs (ACFS, 2013). Ratcliffe et al. (2009) identifies M&As as a way for A-REITs to continue to grow, increase market share and improve shareholder returns.

3 Literature

Prior literature shows no clear consensus regarding the long-term postacquisition performance of bidding firms. Numerous studies have employed different methods with differing conclusions. Bessembinder and Zhang (2013) suggest that long-term studies may be subject to methodological problems. Martynova and Renneboog (2008, p. 2164) suggest that differing results are due to the ‘impossibility to isolate the pure takeover effect from the impact of other events occurring in the years subsequent to the acquisition’. In this section, we examine the extant literature across the different methodologies along with a review of the Australian literature.

Agrawal and Jaffe (2000) provide an extensive review of the postacquisition literature from 1974 to 1998. The vast majority of early studies employed either a market model, market adjusted model, the capital asset-pricing model or a beta-decile matching portfolio to calculate the cumulative average abnormal returns (CARs). Results of these early studies show, on average, that acquirers earn negative ARs postannouncement. For example, Ellert (1976), Dodd and Ruback (1977) and Malatesta (1983) all found negative CARs over the postannouncement period utilising the market model.

Langetieg (1978) identified possible disadvantages of the early methodologies employed in estimating postmerger performance. The author calculated acquirer ARs using a control-firm approach. The excess returns were calculated as the difference between the bidding firm's performance and the control firm's returns. Langetieg (1978) posits that the use of a control group would assess the robustness of the impact the M&A had on existing shareholders. Results showed that acquiring firms earn insignificant ARs over the 1- and 2-year timeframes. Langetieg (1978) concluded that the control-firm approach results are consistent with the efficient market hypothesis.

3.1 Buy-and-hold ARs

The results presented by Langetieg (1978) brought forward the focus on the possible disadvantages of the models employed in estimating postmerger performance. Barber and Lyon (1997), Kothari and Warner (1997) and Lyon et al. (1999) have criticised the methodologies employed in the early post-M&A studies and recommend the use of a buy-and-hold methodology. Barber and Lyon (1997, p. 342) argue that earlier methods to calculate long-term excess returns ‘are conceptually flawed and/or lead to biased test statistics’. Early results from employing BHAR methodology returned insignificant excess returns over the 3-year postannouncement period (Higson and Elliott, 1998; Mitchell and Stafford, 2000).

However, subsequent international studies observed significant negative BHARs post-M&A announcement. In the UK, Cosh and Guest (2001), Sudarsanam and Mahate (2003) and Conn et al. (2005) observed negative and significant BHARs over the 3- to 4-year postannouncement period, ranging from −7.50 percent to −16.30 percent. Betton et al. (2007) examined US M&As and found significant negative BHARs of −21.90 percent over the 5-year postannouncement period. Ang et al. (2008) also observed negative and significant BHARs of −5.02 percent. Following on from these US studies, Bouwman et al. (2009) detected negative and significant BHARs of −7.22 percent. Finally, Bessembinder and Zhang (2013) found acquirers earn negative and significant BHARs of −7.90 percent over the 5-year postannouncement period.

3.2 Three-factor model

Fama and French (1993) propose that the three-factor asset-pricing model be employed to examine long-term abnormal performance because the returns can be described by the size and book-to-market factors. Mitchell and Stafford (2000, p. 288) argue ‘the systematic errors that arise with imperfect expected return proxies – the bad model problem – are compounded with long-horizon returns’. In addition, Mitchell and Stafford (2000) discuss that the BHAR method ignores any cross-sectional dependence of the over-lapping excess returns of individual event firms.

Gregory (1997) employed the three-factor model to examine UK M&As. Results showed bidders earn negative and significant mean monthly ARs of −0.75 percent. This result was supported by later studies examining US acquirers (Mitchell and Stafford, 2000; Gaspar et al., 2005) and Canadian M&As (André et al., 2004). All three studies report negative and significant mean monthly ARs ranging from −0.20 percent to −0.75 percent.

However, Moeller et al. (2004) observed insignificant non-negative monthly ARs. Similarly, Croci et al. (2010) study of UK M&As from 1990 to 2005 also reported insignificant mean monthly ARs. Subsequent studies employing the three-factor model display mixed results. For example, Bouwman et al. (2009), Dutta and Jog (2009) and Latorre et al. (2014) all observed positive and significant mean monthly ARs, ranging from +0.52 percent to +0.70 percent, in their studies of the United States, Canadian and Spanish M&A markets, respectively. In contrast, Alexandridis et al. (2006) reports significantly negative excess returns of −1.02 percent in their UK study and Alexandridis et al. (2012) finds US bidders earn negative and significant mean ARs of −0.25 percent.

A number of studies identify the possible differences in methods and therefore to test the robustness of their results the studies employed both methods. Conn et al. (2005) observed negative and significant postannouncement performance across both methods.3 While Croci et al. (2010) and Datta et al. (2013) detected, insignificant excess returns in both methodologies. Dutta and Jog (2009) present positive and significant ARs from the three-factor model, but insignificant positive BHARs. Finally, Bouwman et al. (2009) produced completely contrasting results. Three-factor average monthly ARs were +0.66 percent and significant (equating to a cumulative average AR of +15.84 percent over the 2-year event period), compared to a negative and significant BHAR of −7.22 percent. Unfortunately, the authors did not provide an explanation for the contrasting results. They did, however, cite Loughran and Ritter (2000) that ‘since different methods have different powers of detecting abnormal performance, there should be differences in AR estimates across different methodologies’ (Bouwman et al., 2009, p. 654).

3.3 Australian evidence

Dodd (1976) conducted the first study of Australian post-M&A performance. He examined the 1-year postannouncement CARs for successful acquirers from 1960 to 1970. Results were consistent with early international studies and showed bidders earned negative and significant ARs. Similarly, McDougall and Round (1986), employing a market model method, showed acquirers earn negative and significant CARs of −18.0 percent over the 2-year postevent period. McDougall and Round (1986, p. 189) concluded that M&As ‘appear to have been caused by so-called managerial motives, or by the desire to develop or enhance market power’.

Subsequent studies employing market model methodology have also observed consistent results for bidders post-M&A. Both Bellamy and Lewin (1992) and Nankervis and Singh (2012) find acquires earn negative and significant CARs in the long-term postperiod. In contrast, Dullard and Hawtrey (2008) find bidders earn positive and significant CARs of +10.57 percent over the [0, +36] event window. The authors conclude that M&As in Australia improve the share price performance of acquirers. However, Dullard and Hawtrey (2008) noted their results may be subject to size bias and the market model employed for the long-term analysis.

The study by Brown and da Silva Rosa (1998) was the first Australian investigation to employ the BHAR methodology. The study found that after controlling for the bias described by Barber and Lyon (1997), acquiring firms earn insignificant excess returns over the [+6, +36] postevent period. Brown and da Silva Rosa (1998, p. 36) conclude that ‘the long-term performance of the acquiring firms in the postmerger period is consistent with the proposition that the market for corporate control is informationally efficient’.

Duong and Izan (2012) also employed BHAR methodology to examine Australian M&As from 1980 to 2004. The study found no significant evidence of postacquisition underperformance. However, the authors extended the analysis to examine the impact merger waves may have on bidder performance. Results showed that M&As occurring during a merger wave resulted in negative and significant long-run BHARs of −2.53 percent over the [0, +18] event window. In contrast, M&As occurring outside a merger wave period returned BHARs of +4.58 percent; however, the result was not significant. The authors concluded that acquisitions made during merger waves provide evidence for the hubris and/or agency motives for M&As.

Australian research results show some consistency with international studies, in that the choice of methodology can have an impact on the observed ARs. Studies that have estimated CARs have found, on average, bidder's wealth is adversely impacted post the M&A. However, studies utilising BHAR methodology do not find sufficient evidence to suggest the postbid phenomenon holds for Australian M&As.4

3.4 REIT postannouncement performance

Research into REIT postannouncement shareholder performance has been limited to only two papers, both of which investigated the US REIT market. Sahin (2005) was the first researcher to investigate the long-term performance utilising both BHAR and three-factor model methodologies. Both methods returned insignificant excess returns results over the 3-year postannouncement period.5

Following on from Sahin (2005), Campbell et al. (2009) conducted the second investigation into the long-term wealth effects within the US REIT sector. Campbell et al. (2009, p. 105) tested if ‘the anomaly of postmerger underperformance observed in conventional firms applies to the case of REITs’. In contrast to Sahin (2005), the study observed negative and significant BHARs of −9.9 percent over the 5-year postacquisition period. However, both the one- and 3-year excess returns were statistically insignificant. The authors concluded that the results confirm that postacquisition underperformance of US REITs is consistent with those observed in more general corporate finance studies and provide support for the hubris and/or agency motive.

Examination of the literature makes it difficult to draw any strong conclusions. On average, the results across varying methods of measuring long-term returns suggest market inefficiency. However, Fama (1998) argues that market efficiency should not be discarded. He suggests that an efficient market produces different types of events that individually cause share prices to over or under-react. The under-reaction will be approximately as frequent as the over-reaction in an efficient market. If these anomalies are split randomly between each other, they are consistent with market efficiency.

Furthermore, it appears that the long-term return anomalies that suggest market inefficiency are sensitive to a number of factors. These include the methodology (Martynova and Renneboog, 2008; Bessembinder and Zhang, 2013), the different markets examined (e.g. Unite States versus Europe), the different time periods studied and possibly the different data sets. To add to the existing knowledge and shed more light on postannouncement shareholder performance, we employ both the BHAR and three-factor methodologies. In addition, by examining the postannouncement performance within the same industry decreases possible ‘inaccuracies resulting from missing pricing factors that may have varying effects across industries’ (Campbell et al., 2009, p. 108).

4 Data collection and methodology

4.1 Data collection

To examine the long-term postannouncement performance of A-REIT acquirers over the period of January 1996 to December 2012, we calculate the excess returns over three-event windows; 1, 2 and 3 years. The screening process employed was:

- the A-REIT monthly share prices must be available for a minimum period of twelve months after the announcement month, to a maximum of 36 months;

- there must be an absence of large-scale confounding events occurring during the postannouncement period6 and,

- accounting data available from their respective annual/semi-annual reports prior the announcement.

This screening resulted in 65 observations for the 1-year event window. The 2-year window comprises 49 observations, while the 3-year period contains 35 observations. The differences in the number of observations across the three periods are due to the first filtering requirement. For example, if a bidder makes an announcement in July 2001 and another in October 2002, the 2001 announcement would only be included in the 1-year excess return calculations. The ARs would not be calculated for the 2- and 3-year periods, because they overlap the October 2002 announcement. However, the October 2002 announcement has no overlapping postannouncement periods, and therefore, excess returns would be calculated for the 1-, 2- and 3-year event windows.

In relation to the buy-and-hold methodology, the study also required the construction of a matching/control portfolio. The control firms are selected from the A-REIT sector and are subject to the same filtering processes described above, with the additional constraint that the control firm is not involved in a M&A during the sample period.

4.2 Methodology

This section presents the two methodologies employed in the postannouncement study. The first method calculates the buy-and-hold excess returns. The second method is based on the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model, which estimates the average monthly ARs. Gregory (1997) and Limmack (1997) discuss that the choice of event study methodology to access long-term performance can have an important impact on the level of ARs. Utilising two different methods will enable the study to test the robustness of the post-M&A performance of A-REIT acquirers. As identified earlier, this is the first Australian postannouncement study, to the authors' knowledge, to employ the three-factor model. Consistent with short-term event study investigations, the study must firstly identify the date of the M&A announcement. Following Campbell et al. (2009), the event month [t = 0] for the study is set as the month end in which the M&A is announced.

4.3 Buy-and-hold abnormal returns

To calculate BHARs, the study needs to firstly identify an appropriate benchmark (nonevent) control sample. Barber and Lyon (1997) and Lyon et al. (1999) argue that the choice of the control sample has an important impact on the empirical power and the test statistics resulting in biased outcomes. Following Lyon et al. (1999) and Campbell et al. (2009), this study identifies all nonevent A-REIT firms available for the study period. The firms are then ranked on market size and then market-to-book value. Market size is calculated as the number of shares on issue times the closing share price one calendar month before the event occurrence. Market-to-book value is calculated as the firm's market value, divided by the book value of the firm reported in their annual report prior the M&A announcement.

The event firm is then matched to three nonevent firms that comprise the control portfolio that is closely equivalent to size and market-to-book value and the control sample is then matched to the event firm for the full buy-and-hold period.7 Utilising control portfolios from the same industry decreases possible ‘inaccuracies resulting from missing pricing factors that may have varying effects across industries’ (Campbell et al., 2009, p. 108).

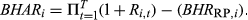

(1)

(1) (2)

(2)BHARi is the BHAR for event firm i over the time period T; Ri,t is the monthly total return for event firm i in month t; Rj,t is the monthly total return for nonevent firm j in month t; n is the number of nonevent firms that make up the control portfolio; and BHRRP,i is the arithmetic average compounded monthly return of the control portfolio.

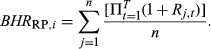

(3)

(3) is the sample mean BHAR calculated over time period T; σ(BHART) is the cross-sectional sample standard deviation; and N is the number of event observations.

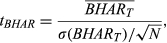

is the sample mean BHAR calculated over time period T; σ(BHART) is the cross-sectional sample standard deviation; and N is the number of event observations. (4)

(4) (5)

(5) (6)

(6)The calculation of  is an estimate of the coefficient of skewness, and

is an estimate of the coefficient of skewness, and  is the standard t-statistic of Equation 3 (Lyon et al., 1999).

is the standard t-statistic of Equation 3 (Lyon et al., 1999).

4.4 Three-factor model

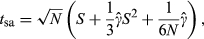

(7)

(7)where Ri,t is the return on security i in month t; Rf,t is the return on the 180-day Bank Accepted Bill Rate in month t; αi is the intercept term; RMRFt is the excess return on the value-weighted market index; SMBt is the return difference between the portfolios of small and large firms in month t; HMLt is the return difference between the portfolios of high and low book-to-market firms in month t; and εi,t is the standard error term.

The intercept, αi, is the variable of interest in the model and measures the mean monthly AR of the event firm. A positive intercept indicates the sample firm has outperformed, after controlling for market, size and book-to-market factors (Barber and Lyon, 1997).

Because the focus of the study is on the A-REIT sector, calculation of the factors is developed from the A-REIT universe. Excluding conventional firms from the estimation of the factors removes any possible noise within the factors that may not be relevant to the A-REIT sector. The market index employed is the S&P/ASX200 A-REIT index. This index captures the price movements of those entities classified as A-REITs on the ASX.

The calculation of the SMB and HML factors follows Brailsford et al. (2012) and Fama and French (1993). Mitchell and Stafford (2000) establish that there is cross-sectional correlation of individual event firms when estimating long-term ARs. Bouwman et al. (2009) discuss that by employing the three-factor model automatically accounts for cross-sectional correlations in the portfolio variance at each point in time. In addition, the three-factor model does not require size and book-to-market data for the event firms, as is the case with the BHAR method does (Barber and Lyon, 1997). Barber and Lyon (1997) demonstrate large firms or firms with low book-to-market values may have common share returns that more closely follow the returns of small firms or high book-to-market firms.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Buy-and-hold abnormal returns

The BHAR results for A-REIT acquirers are presented in Table 1. Panel A displays the results for the full sample period. A-REIT bidders earn negative and significant BHARs over the 2- and 3-year periods of −8.21 percent and −12.27 percent, respectively. These outcomes imply the existence of hubris and/or agency issues. However, the influence of the financial crisis needs to be examined before any strong conclusions can be drawn. Panels B and C of Table 1 partitions the BHARs for announcements occurring prior and post-December 2007 to investigate any differences between the two periods. Pre-GFC results show that A-REIT bidders earn positive and significant BHARs of +3.77 percent over the 1-year period. Both the 2- and 3-year periods are positive but insignificant. This result provides support for the synergy motive for A-REIT M&As in the pre-GFC period.

| Panel A: 1996:2012 | 1 year (65 obs) | 2 year (49 obs) | 3 year (35 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | −2.95 | −8.21 | −12.27 |

| p-Value | 0.246 | 0.034** | 0.002*** |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.220 | 0.019** | 0.002*** |

| Panel B: 1996:2007 | 1 year (43 obs) | 2 year (29 obs) | 3 year (17 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | +3.77 | +2.57 | +0.01 |

| p-Value | 0.055* | 0.471 | 0.998 |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.015** | 0.381 | 0.928 |

| Panel C: 2008:2012 | 1 year (22 obs) | 2 year (20 obs) | 3 year (18 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | −16.07 | −23.85 | −23.86 |

| p-Value | 0.004*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

- This table shows the buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) for acquiring A-REITs over the study period of January 1996 to December 2012. BHARs are calculated over the 1-, 2- and 3-year postannouncement periods. Panel A shows the BHARs calculations for full sample period. Panel B shows the BHARs calculations up to December 2007. Panel C shows all BHAR calculations that occurred after December 2007. BHARs are calculated using the size and market-to-book matching as described by Lyon et al. (1999). p-Values are calculated using a standard t-statistic and a skewness-adjusted t-statistic. ***, **, *show statistical significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent level, respectively.

In contrast, the post-GFC BHARs [2008–2012] are highly significant and negative across all three periods. As shown in Table 1, these range from −16.07 percent for the 1-year window to −23.86 percent for the 3-year period. This outcome highlights the structural change in the A-REIT sector as a result of the GFC. These results support the claims of Betton et al. (2007) who suggest that negative postbid ARs may be due to a negative industry shock. However, one would expect a shock like the GFC to impact nonmerged firms as well. This outcome may be due to the high uncertainty and volatility in the A-REIT sector during this period, making it more difficult to integrate the assets of the target firm and achieve any possible synergistic benefits.

In addition, Rose (2011) highlights that Australian commercial property values were exceptionally high in 2006/2007. With the onset of the GFC, a large number of A-REITs re-valued their property portfolios. In 2009, approximately 40 percent of A-REITs reported property valuation write-downs of greater than 20%, with an average sector write-down of 16 percent (BDO, 2009). This suggests that, in addition to the problems with integrating the targets assets, over-payment for property assets prior to the GFC and subsequent revaluations compounded the under-performance.

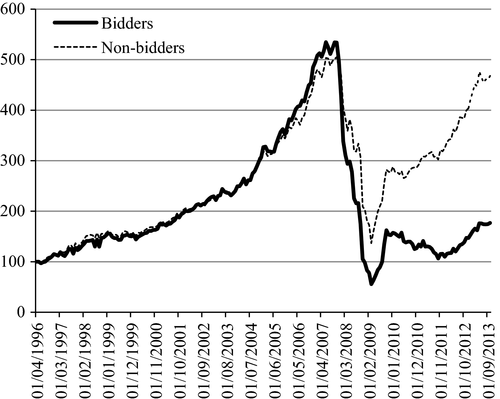

Figure 1 presents the indexed returns for the acquirers and nonacquirers portfolio over the study period. The figure shows that the bidders portfolio closely tracks the control portfolio from 1996 to October 2005. Between October 2005 and October 2007, the bidders' portfolio slightly outperforms the control sample. However, it is clearly evident that after December 2007 both portfolios sharply declined with the acquirers' sample falling at a greater rate. Figure 1 highlights a structural break in the sector as a result of the financial crisis.

The impacts of the GFC appear to continue until March 2009, after which both the acquirers and nonbidder control portfolios begin to recover. BDO (2010) observed a dramatic fall in A-REIT volatility in 2009 compared to 2008. PCA (2010) suggest that the recovery of the sector was due to A-REITs focusing on their core business of rental returns and lower risk exposures. A large number of A-REITs rebalanced their balance sheets through assets sales and capital raisings during the GFC (Newell and Peng, 2009; Dimovski and O'Neill, 2012). This restructuring resulted in a large fall in leverage levels, decrease in exposure to international property markets and a reduction in higher risk activities (e.g. property development), resulting in a decrease in the risk profile of the sector (BDO 2010).

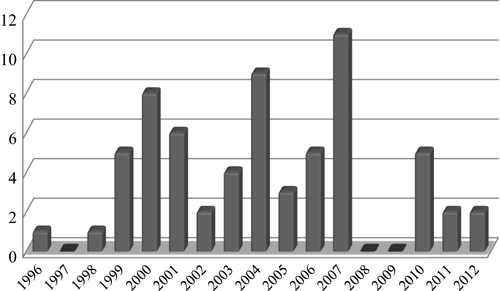

Figure 2 shows the A-REIT M&A announcements by year employed in the study. It can be seen that consolidation activity within the sector gathered momentum in 1999. However, there were no M&A observations from 2008 to 2009 as the impacts of the financial crisis took effect on A-REITs. Martynova and Renneboog (2008) identify that M&A activity ‘is usually disrupted by a steep decline in stock markets and a subsequent recession’. This study therefore concludes that there are three distinct subperiods of activity within the overall analysis. These are pre-December 2007, January 2008 to March 2009 and April 2009 onwards.

Given the observed structural breaks in the data set, the post-December 2007 subsample was further divided into two periods. Any postannouncement ARs calculations that extend over the period of January 2008 to March 2009 are classified as being during the GFC subsample, while calculations occurring after March 2009 are classified as the post-GFC subsample. Table 2 presents the results for these two subsamples.

| Panel A: during-GFC | 1 year (13 obs) | 2 year (13 obs) | 3 year (14 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | −20.27 | −20.78 | −29.53 |

| p-Value | 0.008*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Panel B: post-GFC | 1 year (9 obs) | 2 year (7 obs) | 3 year (4 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | −10.01 | −29.55 | −4.03 |

| p-Value | 0.228 | 0.090* | 0.751 |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.200 | 0.101 | 0.863 |

| Panel C: excl. GFC | 1 year (52 obs) | 2 year (36 obs) | 3 year (21 obs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (%) | +1.38 | −3.67 | −0.76 |

| p-Value | 0.537 | 0.437 | 0.851 |

| Skewness-adjusted p-value | 0.539 | 0.391 | 0.850 |

- This table shows the buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) for acquiring A-REITs over the subperiods. BHARs are calculated over the 1-, 2- and 3-year postannouncement periods. Panel A shows the BHARs calculations for any observation whose returns extend over the period of January 2008 to March 2009. Panel B shows the BHARs calculations after March 2009. Panel C show BHARs calculations excluding the period January 2008 to March 2009. BHARs are calculated using the size and MVBV-matched approach described by Lyon et al. (1999). p-Values are calculated using a standard t-statistic and a skewness-adjusted t-statistic. ***, **, *show statistical significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent level, respectively.

Panel A shows the BHAR results for postannouncement returns that extend past December 2007. The excess returns are negative and significant across all three-event windows, ranging from −20.27 percent in the 1-year model to −29.53 percent for the 3 years. This result is consistent with Duong and Izan (2012) who provides evidence that M&As occurring late in a merger wave earn lower excess returns. Panel B results show that acquirers earn negative and significant BHARs in the 2-year window although one outlier drives this significance. Real Estate Capital US Property Trust was identified to have a BHAR value of −120.02 percent, more than three standard deviations away from the mean BHAR. After removing this outlier observation, the BHAR result was a negative but insignificant value of −14.47 percent. Both 1- and 3-year periods are insignificant.8

Comparing Panel A and B results suggests that the negative BHARs in the 2008 to 2012 subperiod of Table 1 are being driven by postannouncement returns that extend across the financial crisis period. Panel C displays the BHAR results over the full study period, excluding the GFC. The excess returns are insignificant across all three-event periods.9

Results for A-REIT bidders prior the onset of the GFC suggest that the reason for M&As was the synergy motive. One-year BHARs are positive and significant, while the 2- and 3-year BHARs are positive, but insignificant. Conversely, it is evident that A-REIT acquirers were severely punished by investors after the onset of the GFC. The results from the BHAR modelling show that, after accounting for the GFC, the A-REIT sector is consistent with informational efficiency.

5.2 Three-factor model abnormal returns

Three-factor model ARs for A-REITs is presented in Table 3. Panel A displays the full study period, A-REIT bidders exhibit negative and significant ARs in the 2-year event window. The intercept is negative, but insignificant, for the 1- and 2-year periods. This outcome varies slightly from the BHAR results, which displayed significantly negative BHARs over the 3-year model.

| Panel A: 1996:2012 | 1 year (780 obs) | 2 year (1176 obs) | 3 year (1260 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | −0.004 | 0.152 | −0.005 | 0.049** | −0.001 | 0.947 |

| RMRF | 1.114 | 0.000*** | 1.257 | 0.000*** | 1.365 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | 0.081 | 0.236 | 0.127 | 0.034** | 0.078 | 0.238 |

| HML | −0.056 | 0.391 | 0.115 | 0.051* | 0.214 | 0.001*** |

| R 2 | 0.251 | 0.305 | 0.336 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.248 | 0.304 | 0.334 | |||

| Panel B: 1996:2007 | 1 year (516 obs) | 2 year (696 obs) | 3 year (612 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | 0.005 | 0.012** | 0.003 | 0.093* | 0.001 | 0.748 |

| RMRF | 0.584 | 0.000*** | 0.745 | 0.000*** | 0.790 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | 0.063 | 0.251 | 0.036 | 0.354 | 0.051 | 0.174 |

| HML | −0.081 | 0.168 | −0.035 | 0.406 | −0.045 | 0.261 |

| R 2 | 0.092 | 0.162 | 0.224 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.087 | 0.159 | 0.220 | |||

| Panel C: 2008:2012 | 1 year (264 obs) | 2 year (480 obs) | 3 year (648 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | −0.014 | 0.067* | −0.011 | 0.096* | −0.004 | 0.525 |

| RMRF | 1.247 | 0.000*** | 1.366 | 0.000*** | 1.452 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | 0.071 | 0.648 | 0.261 | 0.040** | 0.146 | 0.189 |

| HML | 0.0253 | 0.855 | 0.214 | 0.052* | 0.286 | 0.006*** |

| R 2 | 0.269 | 0.298 | 0.347 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.261 | 0.294 | 0.344 | |||

- This table presents the results of the three-factor model ordinary least squares regression using monthly data for A-REIT bidders over the sample period of 1996–2012. RMRF is the excess return on the A-REIT index, SMB is the return difference between a portfolio of small and large A-REITs, HML is return difference between the portfolios of high and low book-to-market A-REITs. The INTERCEPT measures the mean monthly abnormal return. The number of observations represents monthly bidder excess returns over the event windows. Panel A shows the calculations for the full study period. Panel B presents the results up to December 2007 (pre-GFC), and Panel C shows results for the post-GFC subperiod. ***, **, *show statistical significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent level, respectively.

Results for bidders separated by pre- and post-GFC are displayed in Panels B and C of Table 3, respectively. Pre-GFC ARs are positive across all three-event periods, and both the 1- and 2-year models are statistically significant. This result supports the BHAR conclusions that prior to the onset of the GFC, A-REIT M&As were driven by the synergy motive. Post-GFC results show, consistent with the BHAR approach, that acquirers earn negative and significant ARs across both the 1- and 2-year event periods. However, in contrast, the 3-year window is now insignificant.

We further examine the excess returns over the GFC period. The results are presented in Table 4. Consistent with the BHAR model, acquirers earn negative and significant excess returns during the GFC period in the 1-year event window. Conversely, the 2- and 3-year periods are insignificant. Post-March 2009 long-term ARs are comparable with Table 2, with only the 2-year event period displaying a negative and significant intercept. However, again the significance disappears after removing the outlier observation. Panel C shows the ARs for the full sample, excluding the GFC period. As with the BHAR results, both the 2- and 3-year periods are insignificant. It is observed, however, that the 1-year period AR is positive and significant. The mean monthly AR over the twelve-month period is +0.4 percent.

| Panel A: During-GFC | 1 year (156 obs) | 2 year (312 obs) | 3 year (504 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | −0.022 | 0.082* | −0.005 | 0.638 | 0.007 | 0.370 |

| RMRF | 1.219 | 0.000*** | 1.425 | 0.000*** | 1.461 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | −0.009 | 0.973 | 0.288 | 0.085* | 0.139 | 0.294 |

| HML | 0.068 | 0.761 | 0.317 | 0.036** | 0.339 | 0.009*** |

| R 2 | 0.256 | 0.291 | 0.344 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.241 | 0.284 | 0.340 | |||

| Panel B: Post-GFC | 1 year (108 obs) | 2 year (168 obs) | 3 year (144 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | −0.001 | 0.821 | −0.010 | 0.083* | −0.001 | 0.700 |

| RMRF | 0.817 | 0.001*** | 1.123 | 0.000*** | 1.306 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | 0.082 | 0.714 | 0.150 | 0.379 | 0.069 | 0.553 |

| ' | −0.049 | 0.729 | −0.039 | 0.731 | 0.082 | 0.299 |

| R 2 | 0.121 | 0.181 | 0.431 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.096 | 0.165 | 0.419 | |||

| Panel C: Excl. GFC | 1 year (624 obs) | 2 year (864 obs) | 3 year (756 obs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | Coef. | p-Val | |

| INTERCEPT | 0.004 | 0.051* | −0.001 | 0.921 | 0.000 | 0.890 |

| RMRF | 0.641 | 0.000*** | 0.847 | 0.000*** | 0.918 | 0.000*** |

| SMB | 0.063 | 0.243 | 0.052 | 0.213 | 0.034 | 0.334 |

| HML | −0.077 | 0.148 | −0.050 | 0.223 | −0.006 | 0.864 |

| R 2 | 0.102 | 0.169 | 0.276 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.097 | 0.166 | 0.273 | |||

- Table 4 presents the results of the three-factor model ordinary least squares regression using monthly data for A-REIT bidders over the different subperiods. RMRF is the excess return on the A-REIT index, SMB is the return difference between a portfolio of small and large A-REITs, HML is return difference between the portfolios of high and low book-to-market A-REITs. The INTERCEPT measures the mean monthly abnormal return. The number of observations represents monthly bidder excess returns over the event windows. Panel A shows the AR calculations for any observation whose returns extend over the period of January 2008 to March 2009. Panel B shows the AR calculations after March 2009. Panel C show AR calculations excluding the period January 2008 to March 2009. ***, **, * show statistical significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent level, respectively.

Overall, the results from the three-factor model support the BHAR findings. Prior to the GFC, there is evidence that A-REIT acquisitions were not value destroying for shareholders. However, it is observed that the period of the financial crisis is a significantly different period in the evaluation of the long-term performance of A-REIT bidders. The post-March 2009 period shows some indication that the M&A market in the A-REIT sector is recovering, possibly due to the refocussing of A-REITs on their core business. However, due to a low number of observations, it is difficult to obtain a strong conclusion for this subperiod.

6 Conclusion

This paper has examined whether the long-term postannouncement underperformance anomaly holds in the Australian REIT sector. To test the robustness of postannouncement performance, the study employed two methodologies; BHARs and the three-factor model ARs. The A-REIT sector was selected as a case study because of its regulatory structure. This environment allowed for the examination of long-term postannouncement shareholder performance in a setting that is less vulnerable to agency problems (Eichholtz and Kok, 2008; Ratcliffe et al., 2009).

Results show that A-REIT bidders significantly underperform across the full study period. This finding suggests that the market is not operating efficiently and that the market for corporate control in Australia could be driven by hubris and/or agency issues. Further examination identified a structural break in the sample due to the GFC, resulting in differing outcomes across three different periods. In the precrisis period, A-REIT bidders earned positive and significant excess returns. This result is robust across both methodologies and suggests that the motive for A-REIT M&As was driven by synergy.

Abnormal returns for acquirers whose postannouncement returns extended over the GFC period were negative and highly significant. The outcome is observed in both methodologies. It is hypothesised that the negative excess returns during the crisis subperiod were due to the high volatility and uncertainty in the sector making it difficult for acquirers to integrate the target's assets. In addition, bidders may have over-paid for property assets prior the GFC and the subsequent revaluations compounded their under-performance. It is acknowledged that the number of observations during and post the financial crisis is in some cases low. Nevertheless, it is felt that there is sufficient overall evidence to suggest that the GFC has significantly impacted on the market for corporate control in the A-REIT sector.

Comparing our results to prior research on conventional firms suggest that when managers have less restriction in retained earnings and the type of investment, they may be more susceptible to empire building, than the growth maximisation hypothesis (Marris, 1963). More research into the long-term performance of acquirers in Australia is needed. This includes employing the three-factor and BHAR methods, together with closer examination of different industries, to identify what further impacts agency issues may have on shareholder wealth.

Our results also show that the financial crisis has had a significant impact on the A-REIT sector and the overall investment landscape. However, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions on the impact of the crisis on the market for corporate control, due to low observation numbers. We believe that as more observations become available in this current environment it will provide additional research opportunities and therefore provide an even greater understanding of M&As within Australia.