SAEM GRACE: Anti-craving medications for alcohol use disorder treatment in the emergency department: A systematic review of direct evidence

Supervising Editor: Richard Sinert.

Abstract

Objectives

Alcohol-related concerns commonly present to the emergency department (ED), with a subset of individuals experiencing the symptoms of an alcohol use disorder (AUD). As such, examining the efficacy of pharmacological anti-craving treatment for AUD in the ED is of increasing interest. The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the direct evidence assessing the efficacy of providing anti-craving medications for AUD treatment in the ED.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted according to the patient-intervention-control-outcome question: (P) adults (≥18 years old) presenting to the ED with an AUD (including suspected AUD); (I) anti-craving medications (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin); (C) no prescription or placebo; (O) reduction of repeat ED visits, engagement in addiction services, reductions in heavy drinking days, reductions in any drinking and amount consumed (or abstinence), and in relapse. Two reviewers independently assessed articles for inclusion and conducted risk of bias assessments for included studies.

Results

From 143 potentially relevant articles, 6 met inclusion criteria: 3 clinical trials, and 3 case studies. The clinical trials identified evaluated oral versus extended-release naltrexone, monthly extended-release naltrexone injections, and disulfiram. Both oral and extended-release naltrexone resulted in decreased alcohol consumption. Monthly extended-release naltrexone injections resulted in significant improvements in drinking and quality of life. Although out of scope, the disulfiram studies identified did not result in an improvement in drinking in comparison to no medication.

Conclusions

Overall, there are few studies directly examining the efficacy of anti-craving medications for AUD in the ED, although the limited evidence that exists is supportive of naltrexone pharmacotherapy, particularly extended-release injection formulation. Additional randomized controlled trials are necessary for substantive direct evidence on anti-craving medication initiation in the ED.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is one of the most widely used psychoactive drugs globally, with greater than half of the population reporting at least annual use across Europe, the Americas, and the Western Pacific,1 and is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality.2 Globally, alcohol is responsible for 5.3% of all deaths, the loss of more than 132 million disability-adjusted life-years,1 and is the seventh leading risk factor for both deaths and disability-adjusted life-years.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that ~40% of the harms associated with alcohol use can be attributed to the acute effects of consumption (e.g., injuries) while the remainder are due to the consequences of chronic use, which include cancer, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, infectious diseases, and alcohol use disorder (AUD), the psychiatric condition reflecting alcohol addiction.1, 4 Additional forms of morbidity include associations with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, neurological conditions, and dementia.5

Given the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with alcohol consumption, it is unsurprising that alcohol-related concerns commonly present to the emergency department (ED),6-9 and visits for alcohol-related concerns are increasing.10, 11 These concerns include management of the acute consequences of drinking, such as an injury; medical consequences of chronic use, such as liver disease; or management of alcohol withdrawal after cessation of chronic heavy consumption in AUD. Averaged across countries, the estimated lifetime prevalence of AUD is 8.6%, with rates being substantially higher in North America at approximately 13.8%–18.1%.12, 13 Although presenting to the ED with an alcohol-related complaint does not necessarily mean that the individual has an AUD, the condition is nonetheless highly prevalent among those seeking alcohol-related care. One in four of individuals in the ED for alcohol-related concerns will meet criteria for problematic alcohol use when assessing individuals using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test14, 15 and more than 10% of these individuals will meet criteria for alcohol dependence on more thorough assessment.16, 17 Furthermore, 64% of individuals presenting to the ED for alcohol intoxication have a history of AUD.8

Given the prevalence of individuals with AUD in the ED, there is increasing interest regarding whether the ED is an appropriate setting for the initiation of treatment for AUD. Efforts in this area have historically focused on implementing a protocol of routine alcohol screening, brief intervention, and treatment referral (SBIRT), with generally favorable, albeit variable, outcomes.18, 19 Although training curricula have been developed to facilitate implementation,15 a constraint of this work is that the interventions delivered (e.g., motivational interviewing) are not within the traditional scope of an ED physician. However, with the emergence of pharmacological treatments with proven efficacy for reducing alcohol use and craving in AUD,20, 21 ED physicians may be appropriate clinicians for initiating pharmacological treatment. Medications such as naltrexone, acamprosate, and gabapentin have all shown some efficacy as medications for alcohol and, while varying in pharmacological mechanisms, are broadly referred to as “anti-craving” medications. Both naltrexone and acamprosate have the most evidence supporting their efficacy for treating mild to severe AUD (with majority of studies conducted demonstrating efficacy for moderate to severe AUD). Gabapentin, on the other hand, may be considered for individuals with moderate to severe AUD who may not have responded or are intolerant to naltrexone and acamprosate.21 Specifically, naltrexone and acamprosate are considered first-line agents, and gabapentin is considered a second-line agent.21 Implementing medication-based treatment is important because AUD is often undertreated22 and only a minority of patients with AUD receive evidence-based pharmacotherapies.23, 24 In the United States, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health show a high prevalence of past 12-month health care utilization by individuals with an AUD at 81.4% (of which, 30% was an emergency room visit).25 Although a majority of individuals were screened for AUD, brief intervention only occurred in 28.4% of individuals with severe AUD (and lower for those with mild/moderate AUD). Only 4.3%–15.5% of individuals were referred to treatment, and only 5.8% of individuals with an AUD ultimately received treatment. These data suggest a large gap between individuals seeking help for an AUD and the proportion of these individuals who ultimately receive any form of treatment.25 Additionally, data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) shows that only 4.8% of individuals with AUDs in the past 12-months report receiving treatment for their AUD.26 Thus, there is a need for evidence-based recommendations or guidelines for treating AUD in the ED.27

The Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE) initiative is developing pragmatic clinical guidelines for ED settings.28 The current systematic review appraises the existing direct evidence for the efficacy of initiating anti-craving pharmacological treatments for AUD management in the ED as part of the GRACE evidence-to-decision guideline development process.

METHOD

Population-intervention-comparator-outcome (PICO) question

The PICO question can be summarized as: (P) in patients 18 years of age or older who present to the ED with AUD/suspected AUD and are discharged home (not admitted), (I) does the prescription of an anti-craving medication (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, or gabapentin), (C) compared to no prescription, improve (O) alcohol-related outcomes? Specific outcomes of interest are listed in Table 1.

| Domain | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults older than 18 with AUD who present to the ED | Any reasonable measure of AUD acceptable, including AUDIT |

| Intervention | Anti-craving medications

|

|

| Comparison | No prescription or placebo | |

| Outcome |

Reduction of repeat ED visits Engagement in addiction services (f/u rates) Reduction of heavy drinking days Reduction in any drinking (abstinence) Reduction in amount consumed Reduction in relapse |

Up to 3 months |

| Concept mapping | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key concepts | Alcohol use disorder | Emergency medicine | Craving | Anti-craving medication |

| Related terms | AUD, AUDIT | ED, ER, urgent care, acute care | Naltrexone, Acamprosate, Gabapentin | |

| Search terms: (alcohol OR alcohol use disorder OR AUD) AND (emergency department OR ED OR emergency room OR ER OR emergency OR urgent care) AND (Naltrexone OR Acamprosate OR Gabapentin) | ||||

| Databases: Ovid Medline, APA PsycInfo; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Scopus | ||||

- Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; ED, emergency department; ER, emergency room; PICO, patient-intervention-control-outcome.

Databases included in the search were OVID Medline Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present (March 8, 2022), APA PsycInfo 1806 to February Week 4 2022, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials November 2021, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and executed by a medical librarian (K.C.) except for the search on the Scopus database, which was conducted by a Research Assistant (KM; See Appendix A of Data S1 for the librarian search strategy). Each database was searched for the concepts: AUD, emergency medicine, and anti-craving medication. Any relevant review articles yielded from the search were further scanned for additional references and were not excluded at the abstract screening phase but were excluded during full-text extraction. The search was updated on December 16, 2022, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram reflects the additional records from the updated search.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are in Table 2. Studies were included if the study population was over 18, presenting to the ED for AUD or suspected AUD treatment, and were given an anti-craving prescription (naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin). Studies were excluded if the study population did not present to the ED, if the anti-craving medication was either topiramate or baclofen (disulfiram was included because it is an approved AUD pharmacotherapy), if patients were not discharged, if the article was not accessible or not available in English, if it was a proposed clinical trial with no published results at the time of the search, or if the study was a review/commentary/clinical guideline. However, relevant review articles and non-empirical sources were accessed for reference screening. Each article was assessed for inclusion by two independent reviewers by screening titles and abstracts. Subsequently, relevant articles were flagged, the full text was accessed/reviewed, and the relevant information was extracted. Discrepancies about study inclusion were resolved through discussion between reviewers and consultation with I.B. and J.M. This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.29

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

- Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; ED, emergency department; ER, emergency room; PICO, patient-intervention-control-outcome.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (ROB 2)30 was used to assess risk of bias for the randomized trials, whereas The Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-1)31 assessment tool was used to assess risk of bias for non-randomized trials. Discussion and consensus were used to resolve disagreements in ratings.

RESULTS

Study selection and characteristics

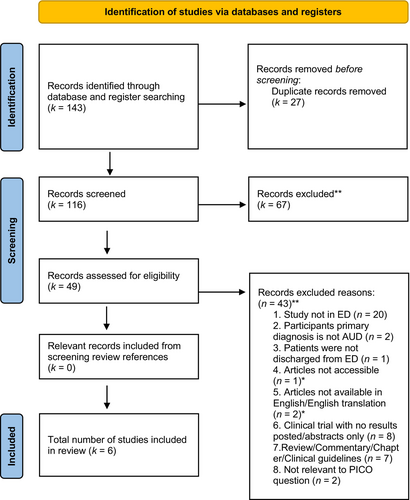

A total of 143 potentially relevant articles were uncovered from the search, of which 49 were identified for full-text screening after removing duplicates and conducting title and abstract screening. A total of 6 additional articles from non-empirical (i.e., reviews, commentaries, clinical guidelines) articles were also full text assessed to screen reference lists for potentially relevant articles, of which none were relevant; therefore, no studies were included in the review from reference lists. Of the total 49 full-text articles accessed, 6 articles met inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for PRISMA flowchart).

Clinical trials

Three clinical trials were included, enrolling a total of 130 patients, and are described in Table 3. The first assessed the efficacy of oral versus extended-release naltrexone,32 and reported naltrexone to decrease alcohol consumption significantly in both oral form and extended-release form.32 Anderson et al. conducted a pilot study examining the effects of oral and extended-release intramuscular naltrexone administered alongside substance use navigation to 59 patients in an ED setting (n = 18 received extended-release, and n = 41 received oral naltrexone). The main outcomes of interest included follow-up engagement in addiction treatment within the first month after being discharged from the ED, and the presence of adverse events. Four patients in the oral naltrexone group and five patients in the extended-release group attended follow-up treatment following the ED visit. The strengths of this study include being one of the first to examine the administration of both oral and extended-release naltrexone for moderate to severe AUD in the ED. The limitations include the lack of comparison between oral versus extended-release naltrexone, and examination of the effects of gabapentin and acamprosate prescribed at discharge, although this is limited due to the small proportion of patients prescribed these medications and low sample size overall.32

| Study | Design | Population | Intervention | Control/No prescription condition | Outcomes | Risk of bias judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, et al. (2021) | Pseudo-RCT (patients chose intervention) |

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

50 mg Oral naltrexone (n = 41) daily |

380 mg Extended-release naltrexone (n = 18) monthly IM injection |

Follow-up

Adverse events

|

High risk |

| Murphy et al. (2022) | Open-label, single-arm study |

Inclusion

Exclusion

|

Extended-release naltrexone (3 injections total at weeks 0, 4, and 8) and case management services provided by a research case manager who was experienced in working with individuals with alcohol use disorder | No comparison (patients serve as their own control) |

Change in daily alcohol consumption (defined as difference in daily alcohol consumption measured at week 12 compared with baseline; median, [IQR])

Alcohol use disorder identification test consumption score (median, [IQR])

Rolling median daily alcohol consumption (median number of drinks reported per person/duration of the reporting period; median, [IQR])

Change in quality of life (Kemp quality of life score; mean, [SD])

Alcohol-related consequences (SIP-2R; median [IQR])

WHO drinking risk level (median [IQR])

Overall, significant improvements in all measures of alcohol consumption, quality of life, and alcohol-related consequences. |

Serious |

| Ulrichsen et al. (2010) | Open label, randomized controlled study |

Inclusion

Exclusion

|

Disulfiram, 800 mg twice a week. If side-effects occurred, the dose could be adjusted to 400 mg or 200 mg twice a week (n = 19) |

Patients in the control group had a similar contact to the patients in the disulfiram group, but received no medication (n = 20) |

No. of participants abstaining from alcohol through treatment period

Time to first drink

Number of alcohol-free days

|

High risk |

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AUD, alcohol use disorder; AUDIT-C, ; ED, emergency department; IM, intramuscular; IQR, interquartile range; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

The second study assessed the efficacy of disulfiram treatment, a medication not targeted by this review, but described for completeness. The trial found a 6-month disulfiram treatment program had no significant difference in patient outcomes in comparison to no medication.33 Specifically, Ulrichsen et al. conducted an open controlled study with two groups of patients: (1) received disulfiram 800 mg 2×/week for 26 weeks (n = 19), and (2) did not receive disulfiram (n = 20). Individuals also received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Several outcomes were assessed including abstinence from alcohol during treatment, time to first drink, number of alcohol-free days and completion of CBT. Individuals initially presented to the ED, however, were then admitted to a psychiatric center. Following hospitalization, individuals attended the study and CBT groups as outpatients. There were no significant group differences in individuals who were abstinent, time to first drink, the number of alcohol-free days or the number of individuals who completed CBT. The strengths of this study include the longitudinal design, and randomization into treatment and a comparison/placebo group. The limitations include potential bias in the participants who consented to participate, potentially because patients who wanted to be treated with disulfiram following alcohol relapse would be more likely to volunteer. Furthermore, although patients originally presented to the ED, the study and disulfiram treatment did not take place in the ED, meaning the equivalence to ED patients in other settings is not clear, and patients were also initially treated with phenobarbital prior to the study.33

The third clinical trial was a 12-week prospective open-label single-arm study including monthly extended-release naltrexone injections, which were administered at weeks 0, 4, and 8.34 In addition to several feasibility outcomes, the primary clinical outcome of interest was change in daily alcohol consumption (differences between the start and end of treatment). Secondary outcomes included changes in quality of life and alcohol-related problems. The trial found a significant improvement in patients' daily alcohol consumption, WHO drinking level risk, alcohol-related consequences, and quality of life from before and after the 12 weeks of treatment and case management initiated in the ED. Daily consumption decreased by −7.5 drinks/day (95% confidence interval [−8.6, −5.9]), drinking risk level decreased by 2 points, and quality of life increased by a clinically significant amount. The strengths of this study include it being one of the first to examine longitudinal effects of naltrexone initiated in the ED, and the inclusion of multiple drinking measures and a quality-of-life measure. Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size, lack of comparison group, and not being able to estimate the effect size of naltrexone versus the other psychosocial or case management interventions separately, which may have differentially contributed to improved outcomes over the 12 weeks.34

Case studies

Three case studies were identified. One case study reported on an adverse reaction of hypoxia following naltrexone administration. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone and bronchodilator therapy and was discharged with a course of oral prednisone, albuterol inhaler, and an outpatient pulmonology follow-up.35 Two of the cases reported on the presentation of an adverse disulfiram-ethanol reaction in a patient presenting to the ED. Although disulfiram was not a target medication in this review, the outcomes are reported for completeness. One of the patients was treated with intravenous fluids and norepinephrine and was able to be discharged to the psychiatric ward after 4 days.36 The other patient was treated with hydration, intramuscular thiamine supplements, and benzodiazepines, but required neurorehabilitation to recover gait function, which was previously diminished (Table 4).37

| Article | Article type | Case demographics | Intervention | Outcomes | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moreels et al. (2012) | Case study |

Age: 42 Gender: Woman Race: Unknown History of mood swings and problem alcohol consumption |

400 mg disulfiram, self-administered |

|

N/A |

| Korpole et al. (2020) | Case study |

Age: 32 Gender: Woman Race: Unknown History of AUD and OUD |

Intramuscular naltrexone *Naltrexone prescribed for AUD and OUD management **Unknown if naltrexone was administered in ED |

|

|

| Tartara et al. (2013) | Case study |

Age: 50 Gender: Woman Race: Unk History of chronic problem alcohol use and depression |

Disulfiram |

|

N/A |

DISCUSSION

The current systematic review examined the direct evidence for using three anti-craving pharmacotherapies for treating AUD in the ED, finding a very limited number of studies. For naltrexone, one study described a naturalistic trial of oral naltrexone versus injectable naltrexone.32 Of note, the medication program described included substance use navigators providing motivational interviewing and considerable linkage between patients and a hospital-based program for follow-up addiction treatment. Nonetheless, the follow-up rates were very low for both formulations and no clear inferences could be made about significant differential effects on drinking. Another trial examining the effect of a 12-week extended-release naltrexone treatment on daily drinking and alcohol-related consequences found significant improvement.34 However, it must be noted that individuals were also receiving motivational interviewing and half of the participants were provided additional case management services.34 In addition, among the 32 patients enrolled, only 23 received all 3 injections. Finally, one case report described an adverse reaction of acute eosinophilic pneumonia after receiving injectable naltrexone, which was treated using intravenous methylprednisolone and bronchodilator therapy.35 Thus, two of the three studies do not provide unequivocally positive evidence on initiating naltrexone treatment in the ED, and only the trial by Murphy et al. provides evidence that initiating naltrexone in the ED leads to substantive improvements in drinking and quality of life. Thus, additional trials with high-retention and a follow-up, and trials with larger sample sizes for greater generalizability are required to support these findings. One of the most effective strategies for increasing follow-up among individuals with substance use disorders and for retaining individuals in treatment and recovery management check-ups is contingency management.38 Contingency management involves providing individuals with tangible reinforcers when individuals engage in behavioral change.39 Incorporating a contingency management component to intervention-based RCTs could improve follow-up rates.

Additionally, future research could experimentally examine medication-only versus medication + additional services to parse-out the specific efficacy of naltrexone or other medications alone. However, it is important to highlight that it is unlikely that recommended best practices would ultimately include medication in isolation without offering patients any other services. For example, motivational interviewing or brief interventions can be effective for addressing alcohol in the ED40-42 and contemporary general practice recommendations include combination therapy (i.e., pharmacotherapies in addition to behavioral interventions).21, 43 Regarding acamprosate and gabapentin, no publications investigating initiating either medication for AUD in the ED were identified. Beyond the target medications, a small number of studies investigated disulfiram, an aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor that interrupts alcohol metabolism and produces an unpleasant syndrome comprising flushing, nausea/vomiting, tachycardia, palpitations, diaphoresis, and vertigo.44 Disulfiram is a second-line AUD medication because of its relatively poor efficacy in the absence of supervised administration and the potentially dangerous consequences of drinking while taking disulfiram.21 The current review recapitulates this perspective to the extent that one trial found no evidence of benefit when disulfiram was initiated in the ED in comparison to usual care,33 and the case studies reported adverse consequences from alcohol-disulfiram interactions.35-37 These results are complemented by two additional case studies from the ED highlighting potential harms from alcohol-disulfiram interactions.45

A potential reason for the lack of studies may be because AUDs, much like other substance use disorders, remain highly stigmatized. Specifically, stigma occurs at many levels, including societal, and even within the health care system itself, as AUDs are often treated as if they are on the periphery of health care. Stigma also acts as a barrier for individuals to access treatment.46, 47 One study examining provider perspectives on the initiation of AUD treatment in the ED identified numerous barriers. For example, capability-related barriers were identified, which included a lack of training in medical school about how to treat AUDs and being unfamiliar with screening tools for how to identify AUDs. Other barriers included staff bias, and the feeling that treating individuals with AUD is complex.48 ED provider stigma may also be present in some cases.49 Given the paucity of direct evidence on this topic, awareness for funding resources and recognition of gaps in medical training and clinical care should be identified for conditions frequently presenting to the ED.50 Identifying priority research areas, increasing training to diagnose and treat individuals with AUDs, and advocating for funding for increasing research in ED settings is critical.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the findings from this systematic review. The first is the lack of studies directly examining the efficacy of anti-craving medication administration for AUD in the ED, meaning conclusions at this stage should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, two of the three existing studies had relatively small sample sizes, with significant loss to follow-up, while the other relevant studies were all case studies. Related, the review was restricted to English language studies, although this is mitigated by the fact that there does not appear to be a sizable non-English literature base. Although the Murphy et al. study demonstrates promising results for initiating anti-craving medication for AUD treatment in the ED, it should be noted that this study was conducted in 2020–2021, corresponding to earlier coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) waves, during which fewer individuals may have been presenting to the ED. This potentially limits the generalizability of the study findings and understanding the true feasibility of initiating treatment for AUD in the ED. Additionally, studies used different and sometimes limited measures to assess efficacy (e.g., focusing on the number of alcohol-free days or abstinence from alcohol). Future studies should use validated alcohol use measures and include quality of life indices to capture the full effect of initiating medication in the ED on an individual's AUD (e.g.,51). Additionally, future studies could extend to look beyond the initial treatment initiation to see what the effects of the medications are longer term. This will allow for improvement in clinical care guidelines and guide the provision of anti-craving medications in ED settings.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review suggests there is relatively little direct evidence addressing initiation of anti-craving medications for AUD in the ED and what little there is suggests that, when initiated, it is challenging to connect AUD patients to follow-up care. Findings from one clinical trial suggest that extended-release naltrexone administration coupled with a motivational interviewing intervention initiated in the ED results in relatively rapid decreases in daily drinking and improved quality of life. Placebo-controlled RCTs are required to corroborate and extend these findings. Although the ED is unquestionably a context where contact with individuals with AUDs commonly takes place, the viability of initiating medication-based treatment there is definitively known based on the current direct evidence.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: I.B. and J.M.; acquisition of the data: K.C. and K.P.; analysis and interpretation of the data: K.P., W.S., K.M., M.S.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J.M., I.B., K.C., K.P., W.S., K.M., M.S.; statistical expertise:N/A; acquisition of funding: J.M. and I.B.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was partially supported through funding from the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) to conduct a systematic review based on Patient-Intervention-Control-Outcome (PICO) question developed by the Guideline for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE) Writing Team. The paper was written in conjunction with the SAEM GRACE initiative. JM is supported by the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research and a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Translational Addiction Research. JM is a principal in Beam Diagnostics, Inc. and has consulted to Clairvoyant Therapeutics, Inc. No other authors have disclosures.