Counter Accounting and Counter Accountability: A Post-COVID-19 Study of England's Hospital Infrastructure Crisis

Abstract

Post-COVID-19 England's health-care system remains in crisis, with growing waiting lists for elective care and rising backlog maintenance in its hospital infrastructure. The government indicates that its delivery plan issued in 2022, involving additional funding and greater use of the private sector, will tackle this problem. Framed as a consequence of the pandemic, in England, such a framing denies the historic problem of underfunding as well as the rise of financialization. Notably public accountability for health care has received little prominence over the past decade. This study uses an approach based on counter accounting to challenge the prevailing hegemony of English National Health System (NHS) health-care infrastructure policy and offers a counter-explanation of the current hospital infrastructure crisis. It examines an alternative set of evidence drawn from publicly available financial statements and other documents to make visible data relating to hospital infrastructure capital and revenue costs. This shows that health care has been systematically underfunded since the start of austerity in 2010, and that even additional funding during COVID-19 was insufficient to make up the shortfall. Previously weakened accountability mechanisms have been further displaced from the public eye by the rhetoric around COVID-19, meaning there is little challenge of private sector legitimacy in public health-care provision, despite its financialized nature. The study considers that instigating strong oversight and evaluation of hospital infrastructure policy is necessary as over the next decade many private sector contracts will terminate and funding is likely to be in short supply.

Having weathered the COVID-19 pandemic, England's health-care system (hereafter the National Health System – NHS) remains in crisis. Ambulances queue outside hospital Accident and Emergency departments, patients experience long waits to see their local doctors, and there are long waiting times for elective care. These concerns are not trivial. Patients not presenting for diagnosis until later, or presenting and then having their treatment delayed, means that conditions are not being caught until later stages, when disease may have progressed and there are fewer treatment options (Morris and Reed, 2022). Numerous medical studies provide evidence of the impact of the pandemic across the population in relation to cancer, mental welfare, and other diseases (Mansfield et al., 2021; Glasbey et al., 2021; Carmichael et al., 2023). Altogether there is more suffering for patients, and a need for more complex treatments, meaning more costs for the NHS.

Government rhetoric has emphasized that the pandemic focused care on COVID-19 patients, creating queues for other diagnoses and treatments. Such framing creates the notion that the problem is not the fault of government; instead it is external factors that are to blame. Moreover, the government solution makes it clear that by providing additional funding and making more use of the private sector, queues for treatment are expected to reduce by 2024/25.

This study uses an approach based on the concept of the counter account to offer an alternative story challenging the hegemonic narrative dominant in public discourse (Chiapello, 2017; Peda and Vinnari 2019; Laine and Vinnari, 2020). The counter account presented here challenges the prevailing hegemony of English NHS health-care capacity policy by showing that the crisis is the result of deliberate government policy choices around underfunding and the use of the private sector to deliver health-care infrastructure and services.

Public accountability has a role to play in understanding and evaluating government policy. The aftermath of the pandemic has raised a set of challenges around how operational changes made to the concept and practices of public accountability can contribute to and inform future policies and sustainable strategies for managing ongoing societal problems arising from the pandemic (Ahrens and Ferry, 2021; Bastida et al., 2022; Rinaldi, 2022). Prior to the pandemic, Bracci et al. (2015) had already raised concerns about accounting and accountability being viewed in a reductionist way, with Leoni et al. (2021, p. 1310) commenting that accountability had become a ‘disciplining and decision tool’ which ‘does not allow consideration of the plurality of priorities and needs which governments need to face and satisfy’. Post COVID-19, therefore, we need to better understand how public accountability and the related issues of transparency and trust have changed as a result of the truncated practices employed during the pandemic (Sian and Smyth, 2022; Ahrens and Ferry, 2021), and consider what impact such changes may have on public accountability for the future. This shift to the use of accountability mechanisms that focus on the provision of technical calculated data is the ‘new normality’ (Leoni et al., 2021, p. 1301), however Lapsley (2020, p. 553) suggests that the government may need to take a more responsive learning approach going forward, so that transparency and accountability are not lost to obfuscation.

The counter account is therefore linked to wider concerns around public accountability set in the context of neoliberalism and financialization. It examines an alternative set of evidence drawn from publicly available financial statements and other documents to make visible data relating to hospital infrastructure capital and related revenue costs. It uses the example of the UK's Private Finance Initiative (PFI) policy to offer a counter-explanation of the current NHS crisis that shows the impact of financialization in this process (Stafford et al., 2022). It follows Tweedie's (2023) call to challenge financial reporting in its current form, links this with Caperchione et al.'s (2017) call for more critical research to be carried out on Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and, following Hellowell et al. (2019), uses formal and numerical sources of information to dispute the case that the current NHS capacity crisis is a direct consequence of the pandemic. The contribution of this paper is therefore to use counter accounting to demonstrate the need for broader forms of public accountability, beyond the narrow, technical mechanisms that have become more prevalent post pandemic, so that there is greater transparency of the impact of financialization.

THE GOVERNMENT ACCOUNT

The motivation for this study began with the publication by the government in February 2022 of its delivery plan for tackling the COVID-19 backlog of elective care (NHS England, 2022). It centred around what was promoted as additional capital investment of over £8 billion (NHS England, 2022, p. 8), made up of £5.9 billion allocated over a three-year period, to increase the capacity available for clinical services to tackle the backlog of diagnosis and treatment, in addition to funding of £2.7 billion previously made available through the Elective Recovery and Targeted Investment Funds. According to the press release, NHS chief executive Amanda Pritchard said: ‘we are determined to make the best possible use of the additional investment and take the best from our pandemic response’; the then Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, said: ‘Today we have launched the biggest catch-up programme in the history of the health service backed by unprecedented funding’; and the then Health and Social Care Secretary, Sajid Javid, said: ‘We are absolutely committed to tackling the COVID backlog and building a health and social care system for the long term.’1 Significantly, this delivery plan only mentions additional capital investment, with no reference to additional revenue funding for the NHS, or where the additional staff needed will come from.

The plan aimed to address four areas of delivery: increasing health service capacity, prioritizing diagnosis and treatment, transforming how elective care is provided, and giving better support and information to patients (NHS England, 2022). There was an emphasis on transforming how services would be provided to patients by delivering more, delivering better, and offering more patient choice. That is to say, the plan presents this solution as a straightforward way post pandemic for the NHS to improve its performance, reduce the waiting list queues, and provide a better quality and more transparent patient experience. Dedicated surgical hubs and scaling up of community diagnostic hubs would provide better support for patients, with the plan promising ‘Using every pound carefully, maximising care and investing for the long term’ (NHS England, 2022, p. 7). However, the private sector was also given a substantial role, a key element being that patients would have the option of treatment in approved private sector centres. Here long-term partnership was seen as crucial in delivering the capacity necessary to tackle the backlog in elective care, as had been the case during the pandemic when the independent sector provided additional beds as well as staff and kit redeployment.

The February 2022 delivery plan was published in the context of the target of 40 new hospitals that has been frequently referred to in Conservative government health infrastructure plans. Originally revealed in the Health Infrastructure Plan (DHSC, 2019) as a ‘new hospital building programme’ being delivered as part of a ‘new, strategic approach to improving our health infrastructure’ which would ‘make sure all of the NHS’ hospital estate is fit for purpose and supports the provision of world class healthcare services’, the period 2020–2025 would see the delivery of six new hospitals with an investment of £2.6 billion whilst 2025–2030 would include schemes for a further 34 new-build hospitals (DHSC, 2019, p. 14). In October 2020 overall funding of £3.7 billion was confirmed for the 40 schemes, along with the opportunity for a further eight hospitals in future years.2 The same program, with the same hospital numbers, was flagged up again in July 2021 but essentially offered nothing new.3 An additional £600 million to deal with 1,789 backlog maintenance projects by March 2021 had been announced in December 2020.4 It should also be noted that in April 2020 the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) had announced that over £13 billion of debt held by NHS Trusts would be written off to help Trusts cope with struggling finances during the COVID-19 pandemic.5

The government account indicates that it was making significant additional funding available, its rhetoric inferring that this would be sufficient both to improve NHS infrastructure and enable the post-COVID-19 crisis in elective care to be resolved. Simply put, the implication is that delivery of the government plans as laid out above would thus eliminate both the waiting list in elective care as well as the problems in relation to backlog maintenance and bed capacity, providing a relatively straightforward story of restoring performance to pre-COVID-19 levels.

EMPLOYING A COUNTER ACCOUNTING LENS

In broad terms, counter accounting can be seen as a way of offering an alternative interpretation to a more dominant form of narrative, or account, that is widely prevalent within a society (Laine and Vinnari, 2020). Frequently described as ‘accounting for the other, by the other’ (Dey et al., 2011, p. 64), counter accounting can be seen as a tool with which to explore different stories and processes to those given by dominant actors (Lundholt et al., 2018). By their very nature, counter accounts are provided in relation to something else, that which they are countering. Within the accounting literature, they have been taken up by the critical accounting community. A frequent use has been in the context of corporate social responsibility, where counter accounts from independent groups can offer informed alternative narratives to the corporate stories of sustainability (Tregidga, 2017). They have also been used as a way of developing types of emancipatory accounting that will challenge the forces of capitalism (Gallhofer and Haslam, 2019). Whilst in some senses counter countering may be regarded as narrative rather than accounting in its purest sense, Tweedie (2023) recognizes that counter accounting provides a form of accountability given that one of its aims is to provide an alternative to conventional accounting by the state. It provides an opportunity to examine a broader, more nuanced analysis of public accountability drawn from a wide range of financial statements and other documents set within a broad political context. It therefore offers a way of developing the counter accounting project at a very practical level, as suggested by Tweedie (2023).

Within the accounting literature on health-care infrastructure, there has been little use of acknowledged counter accounts to date, with one example from Hellowell et al. (2019). However, given the ideological nature of the government's privatization agenda, an integral part of both neoliberalism and financialization, there is clearly scope to use counter accounting to challenge the status quo of government accounting and policy.

The counter accounting argument employed here is that rather than the current NHS financial crisis being caused by COVID-19 alone, there was a funding deficit prior to the pandemic that was worsening from year to year. The structural problems contributing to this deficit are linked to the broad privatization agenda that is part of neoliberalism and is now driven by financialization within the UK. In this context financialization is understood as the growing influence of the capital market in economic, social, and political life (Pike and Pollard, 2010), which has led at the macro level to the proliferation of financial markets, including secondary markets in infrastructure funds (Christophers, 2015), and at the micro level to the shareholder value revolution (Cooper, 2015; Froud et al., 2000). The fragmented nature of financial and accountability reporting within health care means that the impact of financialization remains hidden and obscured. Within hospital infrastructure, although there has been an attempt to increase transparency of equity returns for PFI overall, this has produced only limited improvements relating to the very small number of projects procured under the PF2 policy (NAO, 2018). Within the PFI/PPP accounting literature, Stafford et al. (2022, p. 209) set out how the concept of financialization is deeply embedded in the development of UK PFI policy, including the introduction of NPM techniques (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2004; Shaoul et al., 2007; Asenova and Beck, 2010). Although the term ‘financialization’ is not itself used when the policy starts, the features of financialization can be seen, including the bias towards the financial markets, the requirement for return on investments to be delivered, and the use of value for money as a supposedly impartial financial tool (Froud, 2003; Cooper and Taylor, 2005; Shaoul, 2005; Shaoul et al., 2012). Over time, the evidence of excessive profit extraction for private finance providers, a key outcome of financialization, has grown (Stafford et al., 2022, drawing on Edwards et al., 2004; Shaoul, 2005; Toms et al., 2011; Hellowell and Vecchi, 2012; NAO, 2012, 2018; Smyth and Whitfield, 2017).

The present study draws on these underlying concepts to address the following questions:

How do the government's claims regarding the provision of additional funding run counter to an analysis of NHS funding and capacity since 2010–2011?

How does the counter account created contribute to our understanding of the role of public accountability in financialized healthcare?

RESEARCH METHOD

The study uses the counter accounting-style financial analysis techniques pioneered by Shaoul (1997) and used in studies such as Acerete et al. (2011) and Hellowell et al. (2019) to challenge government claims about private finance. It shows how financial evidence from a public stakeholder perspective can be used to form a narrative that counters the story told in government rhetoric (Stafford, 2023). It draws on publicly available information in the form of documents, financial statements, and analyses provided by the government and various independent bodies, for both public and private sector players. Table 1 sets out the details of relevant timelines and data sources for the areas explored in this counter account. Data are provided at two levels of detail. Overall trends regarding NHS revenue funding, bed numbers, waiting lists, capital investment, and backlog maintenance are provided, in most cases, for the period from 2010/11 to 2021/22. The narrative begins with the start of austerity in the UK following the financial crisis, and when the Conservative Party came to power following 18 years of Labour government. The end point is the year 2021/22, the second of the two years when extra funding was provided due to COVID-19 and the latest year available for some data, for example, backlog maintenance. Detailed examination at the level of the individual Trusts studied and associated private sector partners (special purpose vehicles (SPVs) is provided for the period 2017/18 to 2021/22. Table 2 provides information relating to the Trusts responsible for the top five PFI projects in terms of capital value as reported by HM Treasury (2021).

| Data | Timeline | Source |

|---|---|---|

| NHS overall spend | 2010/11–2021/22 | BMA Health Funding Data Analysis, retrieved from https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/funding/health-funding-data-analysis |

| NHS umulative underspend | 2010/11–2021/22 | BMA Health Funding Data Analysis, retrieved from https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/funding/health-funding-data-analysis |

| Waiting lists | 2010/11–2022/23 | https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/rtt-waiting-times/rtt-data-2023-24/ |

| Population | 2011–2022 | https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates |

| Backlog maintenance | 2011–2022 | https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection |

| PFI details | 2018–2022 | HM Treasury spreadsheets |

| Trust annual reports and accounts | 2017/18–2021/2022 | Individual Trust websites and annual reports |

| SPV financial statements | 2018–2022 | FAME database; individual company accounts retrieved from Companies House |

| Trust name | PFI project hospitals | Capital value of PFI project £ million | Date of construction completion | Names of other main hospitals in the Trust | Special purpose vehicle (SPV) and its highest level shareholders (in brackets) | Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barts Health NHS Trust | - St Bartholomew's Hospital - The Royal London Hospital |

1,149 | 27/02/2016 | - Mile End Hospital - Whipps Cross Hospital - Newham Hospital |

Capital Hospitals Ltd (Equitix Noble Bidco Ltd, Innisfree (various funds) and DIF Infra Yield 1 Finance BV) |

Barts and the London NHS Trust merged with Newham University Hospital NHS Trust and Whipps Cross University Hospital NHS Trust on 01/04/2013. There is an additional PFI project for Newham Hospital with a capital value of £35m and a construction completion date of 22/06/2006 |

| University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | - Queen Elizabeth Hospital | 625 | 01/10/2011 | - Good Hope Hospital - Heartlands Hospital - Solihull Hospital |

Consort Healthcare (Birmingham) Ltd (Balfour Beatty plc, HICL Infrastructure plc and InfraRed Infrastructure Yield LP) |

The Trust merged with the Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust on 01/04/2018 |

| Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust | - Manchester Royal Infirmary - Royal Manchester Children's Hospital - Manchester Royal Eye Hospital - St Mary's Hospital |

512 | 23/08/2009 | - North Manchester General Hospital - University Dental Hospital of Manchester - Wythenshawe Hospital - Withington Community Hospital - Trafford General Hospital - Altrincham Hospital |

Catalyst Healthcare (Manchester) Ltd (Civis PFI/PPP Infrastructure Manchester Holdings Ltd, InfraRed Infrastructure Yield Holdings Ltd and Sodexho Investment Services Ltd) |

Altrincham and Trafford Hospitals joined what was then the Central Manchester Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust on 01/04/2012. Wythenshawe and Withington Community Hospitals then merged to establish the current Trust on 01/10/2017. Finally, on 01/04/2021, North Manchester General Hospital joined the Trust from Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust There is an additional PFI project for Wythenshawe Hospital with a capital value of £85m and a construction completion date of 01/12/2001 |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | - Southmead Hospital | 430 | 26/03/2014 | - Cossham Hospital - Frenchay Hospital |

The Hospital Company (Southmead) Ltd (PIP Multi-Strategy Infrastructure PPP LP and HICL Infrastructure plc) |

|

| North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust | - Peterborough City Hospital | 416 | 01/10/2010 | - Hinchingbrooke Hospital - Stamford and Rutland Hospital |

Peterborough (Progress Health) plc (InfraRed Infrastructure Yield LP) |

Peterborough and Stamford Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust acquired Hinchingbrooke Health Care NHS Trust on 01/04/2017 to form the current Trust |

- Sources: HM Treasury PFI Spreadsheet (2021); individual Trust websites and annual reports, various years; SPV annual accounts, various years

The Counter Account: An Alternative Analysis of the NHS Hospital Infrastructure Crisis

The counter account first examines trends in overall NHS spend, including capital investment, bed capacity, and waiting lists. It then considers the problem of rising costs and the impact of growing backlog maintenance across the English hospital estate. The final analysis considers the accounting and accountability of PFI and its impact on NHS funding and financialization.

Overall revenue spend in real terms for the NHS went up over the period 2010 to 2023, although the figures are skewed by the extra expenditure for COVID-19 in 2020/21 and 2021/22 (see Table 3). However, the rate of increase is low compared to the average historical growth rate of 4.1% over the years 1955/56 to 2009/10. Even with the additional COVID-19 spending, the BMA reports that there is a cumulative underspend of £322 billion (BMA, 2023). Over the same time period, the population in England has grown from an estimated 52.6 million in 2010 to an estimated population of 56.5 million in both 2020 and 2021, the latest years available. Using these figures, the per capita amount rose from £2,441 in 2010 to £3,388 in 2020, prior to the additional COVID-19 spending. However, in comparison to other European countries, this figure is at the low end (The Health Foundation, 2022). In addition, part of the population growth is due to ageing, with the elderly having correspondingly more complex health needs. The Health Foundation (2022) notes that underfunding in health has likely contributed to the NHS being less resilient in terms of care and capacity during and after COVID-19 than would otherwise have been the case. The counter account here therefore casts considerable doubt over the government's claim of providing sufficient additional funding to eliminate the elective care crisis.

| 2010/11 | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NHS revenue spending in England £bn real terms* |

128.4 | 128.7 | 129.5 | 131.8 | 135.3 | 139.5 | 140.9 | 143.2 | 143.7 | 150.3 | 191.4 | 193.0 |

| Percentage increase over previous year | – | 0.2% | 0.6% | 1.8% | 2.7% | 3.1% | 1.0% | 1.6% | 0.3% | 4.6% | 27.3% | 0.8% |

NHS capital spending in England£bn real terms* |

5.5 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 13.7 | 9.9 |

| Percentage increase over previous year | – | 10.9% | 0.0% | 11.5% | –8.8% | –6.5% | –5.2% | 14.5% | 11.1% | 14.3% | 71.3% | –27.7% |

| Backlog maintenance £bn | N/A | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 10.2 |

| Percentage increase over previous year | – | – | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.5% | 16.3% | 10.0% | 9.1% | 8.3% | 38.5% | 2.2% | 10.9% |

| Cumulative percentage increase | – | – | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.5% | 25.0% | 37.5% | 50.0% | 62.5% | 125.0% | 130.0% | 155.0% |

| PFI unitary charges £bn # | 1.44 | 1.62 | 1.71 | 1.78 | 1.86 | 1.94 | 1.93 | 1.97 | 2.04 | 2.10 | 2.14 | 2.20 |

| Percentage increase over previous year | – | 12.5% | 5.6% | 4.1% | 4.5% | 4.3% | –0.5% | 2.1% | 3.6% | 2.9% | 1.9% | 2.8% |

| Percentage of NHS spending | 1.12% | 1.26% | 1.32% | 1.35% | 1.37% | 1.39% | 1.37% | 1.38% | 1.42% | 1.40% | 1.12% | 1.14% |

- * 2023/24 prices based on March 2023 GDP Deflator. # Prior to 2011/12 the figures are distorted due to some PFI hospitals still being constructed.

- Sources: See Table 2.

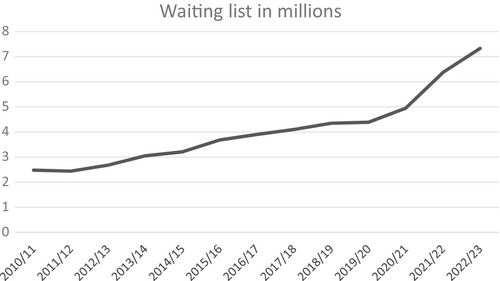

Indeed, waiting lists were already on the rise prior to COVID-19. Figure 1 shows waiting lists increasing year on year from 2011/12 onwards, with a 77% increase between 2010/11 and 2019/20, just prior to the pandemic. The further 70% increase in waiting list numbers between 2019/20 and 2022/23 covers not only the expected backlog due to elective care stopping during the pandemic, when routine referrals and surgery were cancelled, but also what the BMA (2022) refers to as the ‘hidden backlog’ of those who did not come forward with health-care needs at the time, and who now have more complex or advanced conditions which require more time and treatment to resolve.

Hospital bed numbers have also been in decline (The Kings Fund, 2021). OECD figures show that in 2022 the UK had the lowest beds per 1,000 inhabitants of the G7 at 2.3, a fall of 44% from the year 2000 with UK bed indicators falling below the US in 2010 and Canada in 2015.6 Therefore, there was evidence of a shortage of beds well before COVID-19, with The King's Fund (2021) reporting that ‘In 2019/20, overnight general and acute bed occupancy averaged 90.2 per cent, and regularly exceeded 95 per cent in winter, well above the level many consider safe’.

At the same time as bed numbers have been decreasing, NHS costs have increased, and at a faster rate than NHS funding (Hellowell, 2018; Hellowell et al., 2019). From 2013–2014 onwards, Trusts started to go into deficit on their annual revenue budgets, with two thirds of Trusts in this position in 2014/15. The 2015 Spending Review alleviated the position to some extent by starting the process of transferring funds from the capital to the revenue budgets, but many Trusts, including two thirds of London Trusts, remained in significant deficit up to 2019/20.7 Gainsbury (2021) notes that one of the reasons was ‘unrealistically high assumptions about the value of cost savings that could be extracted from providers’ expenses’.

Even before the government started to move funds out of the annual capital spending budget, NHS capital spending (see Table 3) was low in comparison to international standards, to the extent that poor built environments and ageing equipment meant that staff could not deliver optimal care (Kraindler et al., 2019). The poor condition of much of the English hospital estate has been a perennial problem for the NHS, with buildings still in use in 2023 that pre-date the formation of the NHS in 1948 as well as later buildings from the 1960s onwards which are now in a poor state of repair due to structural failure. Successive Conservative governments in power from 1979 put little investment into hospital infrastructure, and it fell to the Labour government from 1997 to introduce a program of hospital building using the PFI policy to leverage the use of private finance. By the end of the Labour government in 2010, there were 109 NHS PFI projects relating to hospitals with a total capital value of £12.1 billion (HM Treasury, 2021).8 However, as there are 515 NHS hospitals in England, this represents only just over 20% of hospitals.9 In 2012 the Coalition government replaced PFI with the Private Finance 2 (PF2) program, but in health care this delivered only the much-delayed and over-budget Midland Metropolitan Hospital (NAO, 2020), the policy being discontinued in 2018.

Much of the NHS estate has therefore been left in a poor state of repair. With insufficient funding being available since austerity as reported above, there has been growing backlog maintenance, defined as ‘the measure of how much would need to be invested to restore a building to a certain state based on a state of assessed risk criteria. It does not include planned maintenance work (rather, it is work that should already have taken place)’.10 Table 3 shows the rise in backlog maintenance over the years 2011/12 to 2021/22, with the amount increasing by 155% to £10.2 billion over the 11-year period. This amount is notably higher than the £8 billion allocated by the government for capital investment to 2030.

PFI contracts also contribute to the pressure on NHS costs, with additional costs including higher operating costs, higher costs of finance, and the additional burden of having to provide a return to investors (Edwards et al., 2004). Although unitary charges only account for around 1.4% of overall annual NHS spend (see Table 3), at local Trust level they can create affordability issues.11 At the start of austerity, the Treasury (2011) issued guidance on how Trusts with PFI hospitals could implement savings. Some Trusts have tried to reduce costs and make their projects more affordable on an individual basis. Two Trusts (Tees Esk and Wear Valley NHS Foundation Trust and Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust) have successfully terminated PFI contracts (West Park and Hexham respectively) early to reduce operational expenditure. Although there was a significant cost to break the contracts, the expected savings were also substantial (Whitfield, 2017; Hellowell et al., 2019). One Trust, the South London Healthcare Trust, went bankrupt over the high cost of its PFI hospitals. Lethbridge (2014) notes that the costs of servicing the capital for the two PFI hospitals within the Trust were much higher than the average, thereby contributing to the deficit that pushed the Trust into administration. One of the hospitals concerned, the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, Woolwich, further exercised a break in the soft Facilities Management element (cleaning, laundry, grounds maintenance, and catering) of its PFI contract in February 2020 (Lewisham and Greenwich Annual Report, 2019/20), which has led to a reduction of around £9 million per year in the service element payment for PFI schemes (Lewisham and Greenwich Annual Report, 2020/21). A further Trust, Barts Health NHS Trust, which has the largest PFI scheme in the country (see Table 2), made the decision at the time of construction not to fit out two whole floors of the Royal London hospital in a bid to reduce operational costs from the start. Bed numbers reduced from 1,248 down to 990, a cut of 21%. Even with this decision, actual unitary charges remained higher than originally projected and are forecast to rise each year to a maximum of £221 million in 2047/48, after which the contract ends (HM Treasury, 2021).

The government's account indicated that in April 2020 £13 billion of debt was being written off to help Trusts manage their finances better. However, whilst the public may have understood this alleviation of NHS Trust debt as a wiping out of loans, in fact the policy saw the conversion of debt borrowed from the DHSC to public dividend capital, the NHS's version of equity. But although equity, unlike debt, does not need to be repaid, in the NHS system of accounting it does incur an annual cost, currently set at 3.5% of the relevant assets of each NHS Trust, meaning that Trusts may still face financial difficulties. Kraindler (2020) notes concerns about the ongoing financial positions of those Trusts which had found themselves in financial difficulties prior to the pandemic, given that the underlying problems causing deficits in the first place will not have gone away.

NHS Trusts usually consist of more than one hospital, meaning that Trusts with PFI hospitals may make financial decisions on infrastructure at the expense of other hospitals in the same Trust. PFI contracts include the cost of maintaining building and equipment—whilst this can be very expensive it does mean that facilities and equipment are well maintained over time.12 In contrast, the non-PFI hospitals in the same Trust are unlikely to be well maintained or to have sufficient equipment replacement, and if the Trust is under financial pressure, then backlog maintenance for these hospitals could rise. Table 4 shows the financial outcomes for the years 2017/18 to 2021/22 for the Trusts with the five biggest PFI schemes, all of which also contain non-PFI, and therefore older, hospitals. It shows a mixed picture with all Trusts recording at least one deficit during this period and four recording at least three deficits, despite the extra COVID-19 income in 2020/21 and 2021/22. Barts Health NHS Trust shows the worst deficit, and is in deficit throughout the period. It also has the highest backlog maintenance, and stands out as the Trust with the fifth highest backlog in 2022 (Appleby, 2022). University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust has managed to move into a surplus position in 2018/19 and thereafter; this may be because its unitary charge as a percentage of income is around half that of the other Trusts, and it is not addressing its rising backlog maintenance. Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust has the most hospitals and two PFI schemes which gives it the largest overall operating income; however, it has also been running deficits since 2019/20. Unitary charges are high as there are two projects, but backlog maintenance was low until the North Manchester General Hospital joined the Trust in 2021/22.13 North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust has by far the highest unitary charge as a percentage of income, averaging £12.4 million per year prior to COVID-19, reflecting the fact that the PFI scheme for the Peterborough City Hospital was regarded as unaffordable from the start (NAO, 2012). The decision in 2017 to acquire Hinchingbrooke Health Care NHS Trust was an attempt to reduce the annual deficit by spreading the costs over wider sources of income, but although income has risen by 48% over the five-year period, it remains in annual deficit.

| Trust | Total operating income £m | % increase year on year | Surplus/Deficit for year £m | % of income | Unitary payments £m | % of income | Backlog maintenance £m | % of income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barts Health NHS Trust | ||||||||

| 2017/18 | 1,512.7 | – | –108.3 | –7.2% | 122.9 | 8.1% | 134.0 | 8.9% |

| 2018/19 | 1,526.7 | 0.9% | –87.3 | –5.7% | 122.2 | 8.0% | 200.0 | 13.1% |

| 2019/20 | 1,698.1 | 11.2% | –76.3 | –4.5% | 123.8 | 7.3% | 267.0 | 15.7% |

| 2020/21 | 1,987.7 | 17.1% | –2.5 | –0.1% | 126.1 | 6.3% | 177.7 | 8.9% |

| 2021/22 | 2,032.5 | 2.3% | –20.3% | –1.0% | 130.4 | 6.4% | 315.1 | 15.5% |

| University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | ||||||||

| 2017/18 Note 1 | 1,548.8 | – | –31.8 | –2.1% | 55.1 | 3.6% | 128.1 | 8.3% |

| 2018/19 | 1,613.6 | 4.2% | 132.8 | 8.2% | 57.6 | 3.6% | 130.0 | 8.1% |

| 2019/20 | 1,758.4 | 9.0% | 0.4 | 0.0% | 60.2 | 3.4% | 139.8 | 8.0% |

| 2020/21 | 2,050.5 | 16.6% | 13.7 | 0.7% | 61.6 | 3.0% | 151.2 | 7.4% |

| 2021/22 | 2,066.2 | 0.8% | 34.8 | 1.7% | 62.7 | 3.0% | 191.6 | 9.3% |

| Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust | ||||||||

| 2017/18 Note 2 | 826.8 | – | 209.6 | 25.4% | 60.4 | 7.3% | 49.0 | 5.9% |

| 2018/19 | 1706.8 | – | 26.8 | 1.6% | 116.3 | 6.8% | 51.8 | 3.0% |

| 2019/20 | 1825.7 | 7.0% | –27.5 | –1.5% | 124.4 | 6.8% | 55.1 | 3.0% |

| 2020/21 | 2152.2 | 17.9% | –32.9 | –1.5% | 125.3 | 5.8% | 56.3 | 2.6% |

| 2021/22 Note 3 | 2472.9 | 14.9% | –11.3 | –0.5% | 128.2 | 5.2% | 223.6 | 9.0% |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | ||||||||

| 2017/18 | 570.9 | – | –16.7 | –2.9% | 49.1 | 8.6% | 11.0 | 1.9% |

| 2018/19 | 607.6 | 6.4% | –5.5 | –0.9% | 50.6 | 8.3% | 11.0 | 1.8% |

| 2019/20 | 670.2 | 10.3% | –3.6 | –0.5% | 49.3 | 7.4% | 28.0 | 4.2% |

| 2020/21 | 774.9 | 15.6% | 4.5 | 0.6% | 50.9 | 6.6% | 20.4 | 2.6% |

| 2021/22 | 792.1 | 2.2% | –0.2 | 0.0% | 50.1 | 6.3% | 25.1 | 3.2% |

| North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust | ||||||||

| 2017/18 | 420.4 | – | –7.6 | –1.8% | 55.0 | 13.1% | 26.7 | 6.4% |

| 2018/19 | 435.9 | 3.7% | –46.5 | –10.7% | 56.3 | 12.9% | 26.7 | 6.1% |

| 2019/20 | 521.4 | 19.6% | 0.4 | 0.1% | 58.2 | 11.2% | 660.2 | 11.5% |

| 2020/21 | 583.3 | 11.9% | –2.2 | –0.4% | 60.0 | 10.3% | 43.5 | 7.5% |

| 2021/22 | 621.8 | 6.6% | –0.7 | –0.1% | 62.0 | 10.0% | 54.3 | 8.7% |

- Adjusted to include figures for Heart of England NHS FT. Six months only due to Trust merger on 01/10/2017 (see Table 2). Includes the North Manchester General Hospital, which joined the Trust on 01/04/21. Sources: Trust annual report and accounts, various years, ERIC database, various years.

Examining the relevant SPVs’ financial statements for these Trusts also shows a mixed picture (see Table 5). With the exception of Catalyst Healthcare (Manchester) Ltd in 2020/21, none of the SPVs for these contracts show a net profit margin greater than 10%, and only Peterborough (Progress Health) plc has no loss-making years. It is, however, the only SPV showing negative equity, due to not yet having earned sufficient profits to wipe out start-up losses incurred over the period 2008–2011. Return on equity percentages remain below 10% for all SPVs, apart from years 2018–2020 for Capital Hospitals Ltd and 2020–2021 for Catalyst Healthcare (Manchester) Ltd. However, all projects are largely financed by debt, not equity, as shown by the capital gearing ratio in excess of 84% for all SPVs. The interest rate on debt ranges from 4.5% to 8.5% for the years 2017/18 to 2020/21 and, for Capital Hospitals Ltd and Catalyst Healthcare (Manchester) Ltd, it exceeds 11% for 2021/22, due to rising inflation. Notably for these two SPVs and for Consort Healthcare (Birmingham) Ltd the majority of debt is provided in the form of group loans, meaning that the groups are receiving good low-risk returns on their investments in the form of interest received.

| SPV | Turnover £m | Interest received £m | Interest paid £m | Profit for the year £m | Total debt £m | Total equity £m | Net profit margin | Interest rate on debt | Capital gearing ratio | Return on capital employed | Return on equity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Hospitals Ltd | |||||||||||

| 2017/18 | 59.3 | 77.0 | 85.5 | –1.2 | 1,450.0 | 13.6 | –2.0% | 5.9% | 99.1% | –0.1% | –8.8% |

| 2018/19 | 67.6 | 66.0 | 72.5 | 6.6 | 1,444.2 | 20.2 | 9.8% | 5.0% | 98.6% | 0.5% | 32.7% |

| 2019/20 | 63.4 | 59.0 | 64.7 | 3.6 | 1,424.3 | 23.9 | 5.7% | 4.5% | 98.3% | 0.2% | 15.1% |

| 2020/21 | 71.0 | 62.0 | 70.6 | 1.8 | 1,414.7 | 25.6 | 2.5% | 5.0% | 98.2% | 0.1% | 7.0% |

| 2021/22 | 85.3 | 141.8 | 167.3 | –8.1 | 1,502.2 | 17.5 | –9.5% | 11.1% | 98.8% | –0.5% | –46.3% |

| Consort Healthcare (Birmingham) Ltd | |||||||||||

| 2017/18 | 34.1 | 39.5 | 43.1 | 1.2 | 755.9 | 30.4 | 3.5% | 5.7% | 96.1% | 0.2% | 3.9% |

| 2018/19 | 34.5 | 39.3 | 44.8 | –1.4 | 766.5 | 29.0 | –4.1% | 5.8% | 96.4% | –0.2% | –4.8% |

| 2019/20 | 35.4 | 39.0 | 46.6 | –3.3 | 776.2 | 25.7 | –9.3% | 6.0% | 96.8% | –0.4% | –12.8% |

| 2020/21 | 39.2 | 38.3 | 46.9 | –5.1 | 785.3 | 20.6 | –13.0% | 6.0% | 97.4% | –0.6% | –24.8% |

| 2021/22 | 40.1 | 42.6 | 60.8 | –13.6 | 806.4 | 7.0 | –33.9% | 7.5% | 99.1% | –1.7% | –194.3% |

| Catalyst Healthcare (Manchester) Ltd | |||||||||||

| 2017/18 | 58.4 | 32.3 | 37.4 | 0.3 | 465.5 | 45.4 | 0.5% | 8.0% | 91.1% | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| 2018/19 | 60.1 | 32.1 | 33.4 | 2.9 | 470.2 | 48.2 | 4.8% | 7.1% | 90.7% | 0.6% | 6.0% |

| 2019/20 | 63.0 | 31.5 | 34.3 | 1.4 | 470.8 | 49.6 | 2.2% | 7.3% | 90.5% | 0.3% | 2.8% |

| 2020/21 | 60.9 | 30.7 | 26.4 | 7.9 | 448.2 | 57.5 | 13.0% | 5.9% | 88.6% | 1.6% | 13.7% |

| 2021/22 | 75.3 | 32.1 | 55.8 | –12.8 | 469.4 | 44.7 | –17.0% | 11.9% | 91.3% | –2.5% | –28.6% |

| The Hospital Company (Southmead) Ltd | |||||||||||

| 2017/18 | 18.4 | 45.1 | 48.2 | –3.7 | 564.6 | 110.7 | –20.1% | 8.5% | 83.6% | –0.5% | –3.3% |

| 2018/19 | 16.0 | 45.3 | 42.5 | 0.2 | 560.3 | 94.9 | 1.3% | 7.6% | 85.5% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| 2019/20 | 11.6 | 45.2 | 42.3 | –2.7 | 562.2 | 88.5 | –23.3% | 7.5% | 86.4% | –0.4% | –3.1% |

| 2020/21 | 16.9 | 46.1 | 43.4 | 0.7 | 556.6 | 107.7 | 4.1% | 7.8% | 83.8% | 0.1% | 0.6% |

| 2021/22 | 20.0 | 46.8 | 44.3 | –1.3 | 550.3 | 77.4 | –6.5% | 8.1% | 87.7% | –0.2% | –1.7% |

| Peterborough (Progress Health) plc | |||||||||||

| 2017/18 | 38.4 | 21.2 | 24.1 | 6.5 | 374.1 | –57.6 | 16.9% | 6.4% | 118.2% | 2.1% | –11.3% |

| 2018/19 | 43.7 | 20.9 | 23.8 | 6.6 | 452.5 | –60.2 | 15.1% | 5.3% | 115.3% | 1.7% | –11.0% |

| 2019/20 | 45.0 | 24.1 | 23.3 | 6.0 | 422.1 | –38.1 | 13.3% | 5.5% | 109.9% | 1.6% | –15.7% |

| 2020/21 | 55.5 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 6.4 | 434.5 | –49.1 | 11.5% | 5.3% | 112.7% | 1.7% | –13.0% |

| 2021/22 | 45.8 | 22.2 | 22.5 | 5.4 | 498.7 | –93.8 | 11.8% | 4.5% | 123.2% | 1.3% | –5.8% |

Overall, for the five Trusts studied, there is a continuing pattern of either recorded deficits and/or rising backlog maintenance, whilst in contrast their PFI private partners were delivering good low-risk returns for their financiers.

Table 2 shows the highest-level shareholders identified for each of the five SPVs. These top-level shareholders are all infrastructure investment entities, with organizational structures designed via a complex web of holding and finance companies so that no one party owns or controls enough of the SPV to require consolidation.

Over the time that PFI hospitals have been in existence, institutional investors, including private equity and the equity markets, have recognized that health care is a good infrastructure asset class to invest in, due to the low risk but stable and often excessive returns (PwC, 2010; Whitfield and Smyth, 2019). Whitfield (2017) notes that hospitals and health centres saw the second highest number of equity transactions (behind schools and colleges), representing a total of 277 (27.8%) out of 1,003 transactions in the European Services Strategy Unit PPP Equity Database 1998–2016. It should also be noted that of course these secondary market transactions merely demonstrate the playing out of financialization; they do not bring additional resources into projects, but simply offer institutional investors the opportunity to seek out long-term profits from existing projects in stable and low-risk sectors (Stafford et al., 2022). However, in summary, it can be seen that the private sector, whether at SPV level or in the infrastructure market more generally, is delivering a higher level of financial performance than the NHS Trusts with which they are interacting, whether directly through a PFI contract, or indirectly by financing the SPV through either or both of equity and debt. The government account gave the private sector a substantial role in delivering the capacity needed to tackle backlog in elective care, yet this counter account indicates that the private sector puts additional pressure on NHS costs whilst it benefits from stable low-risk returns.

DISCUSSION

The counter accounting approach used here offers an alternative story to the hegemonic narrative presented by the UK government. It shows that the transformational delivery of elective care set out in the government's plan (NHS England, 2022) cannot be achievable given the context shown above of continuing insufficient funding, decreasing bed capacity, a large and growing pool of poorly maintained hospital infrastructure, and increasing involvement of the private sector, this last inevitably meaning the extraction of financial resources away from the public sector. All of this is happening at the expense of the growing number of patients, a growing proportion of whom have complex medical needs. The NHS continues to be in deficit for revenue spending, meaning less elective care will be carried out and waiting lists will not reduce (Helm and Campbell, 2023; Campbell, 2023). Capacity-building programs are behind schedule with the NAO (2023) noting that the government has not achieved Value for Money in its new hospital building program. Bed shortages continue and are made worse by bed blocking as elderly patients have nowhere safe to go. Until social care is reformed in England performance will continue to decline (Ham, 2023). Furthermore the counter account shows how backlog maintenance continues to rise, both at overall and local levels. The government's stated amount of £600 million to cover this is insufficient to cover even the five Trusts’ backlog analyzed in this study.

The implied risk is that England may develop a two-tier hospital system, as usage may adapt to take advantage of the best infrastructure. PFI hospital infrastructure is well maintained and operated, as it has to be under contract requirements, although this is expensive. Although there are no studies on backlog maintenance in the UK, Herath et al. (2023) note that in Australian schools PFI-style procurement methods unsurprisingly lead to overall improvements in infrastructure maintenance, but that additional funding is needed to bring the quality of maintenance in non-PFI schools up to the same level as PFI schools. It follows that, unless there is significant investment to decrease backlog maintenance, non-PFI hospitals will become less efficient as buildings deteriorate and the number and value of high-risk maintenance issues increase. White (2019) confirms this situation in his study of Ontario PPP and non-PPP hospitals. In England the NHS delivery plan refers to transforming patient choice. It is likely that where there is the opportunity to do so, patients who can will choose to attend modern, well-maintained buildings over old and crumbling structures for their elective care, as Acerete et al. (2011) note in their study of the Alzira hospital in Spain. Ceteris paribus, this situation has the potential to impact Trust income, given that patients can choose to attend hospitals across more than one Trust area. A further consequence is likely to be increased health inequality, as it is the well-informed and likely wealthier patients who choose where to be treated, compared to the less well-to-do.

However, this is a complex scenario. Given that hospitals generate income based on the procedures they undertake, this means that PFI hospitals with fewer beds than the hospitals they replaced could therefore be restricted in their ability to earn income from NHS commissioning groups, especially if they experience bed blocking. But at the same time unitary costs for PFI hospitals are increasing, which must be met due to the legally binding nature of the contracts. Although Trusts have been urged by the DHSC to make savings, this is difficult to achieve given PFI contracts tend to benchmark costs upwards. Decisions made relating to how Trusts are structured and how and where PFI hospitals have been provided could lead to some Trusts being able to sustain high incomes due to having modern hospitals and good bed capacity, whilst other Trusts could lose out if they hold the more expensive PFI contracts combined with lower bed throughput, combined with old or failing infrastructure elsewhere in the Trust. Overall this can lead to both intra- and inter-Trust tension, given that the insufficient resources available do not permit fair allocation of resources. Consideration of such implications should be part of a robust public accountability system.

The counter account is set during a time of systematic decline in the structures of public accountability in the UK. The abolition of the Audit Commission in 2012 led to a decline in monitoring and therefore in transparency of how contract management and decision-making power was being managed in the health-care sector (Ellwood and Garcia-Lacalle, 2015). The replacement mechanisms on which bodies such as Monitor (the sector regulator for NHS services, since 2016 part of NHS Improvement) focus, rely on features such as traffic light systems where financial performance is measured according to pre-determined norms. As such they could be regarded as precursors of the types of calculations discussed by Ahrens and Ferry (2021) in their analysis of surveillance measures during COVID-19. An issue with such an approach to financial performance in health is that the accountability mechanism becomes focused on whether or not technical measures are met at the detailed level. Items that fall outside the narrow frame of monitoring can be overlooked, as can the wider picture regarding the public interest. Ahrens and Ferry (2021) have called for continued use of VFM audits to ensure public accountability is maintained. The NAO has continued to carry out a range of VFM reports on health-care matters, publishing 20 reports on health care since the start of the pandemic. However, its broader remit at government level, compared to the more regional focus of the former Audit Commission, means less attention is paid to issues of regional and/or local importance. Additionally, as the NAO can only comment on, but not challenge, government policy, it acts only within the prevailing government's hegemony.

In contrast, the counter account given here is framed in the wider context of neoliberalism and financialization. This enables examination of public accountability around the challenges provided by the turn to the private sector in health care. Many developed countries now face a key challenge about the extent to which the private sector should be providing some of the health care within national health-care systems largely funded through social security contributions. In the UK context, Heald and Hodges (2020) note that such a system cannot be adequately delivered without raising rates of tax. Additionally, such private provision of public services should be evaluated and held accountable to the public, given that private providers generate returns to their investors and lenders from their activities, as health care is one of the many sectors now subject to financialization (Hunter and Murray, 2019).

In the UK, growing private delivery of health-care-related services is a long-standing feature which has occurred particularly through the use of PFI hospitals, although other parts of the health and social care system are also implicated, for example, the growing problems in social care (Burns et al., 2016), the increasing use of outsourcing whereby private companies deliver health-care services such as scans on behalf of the NHS, and the incursion of American companies into primary health-care centres (Spolar, 2022). During their time in government, the Labour government were explicit about their use of private finance to improve hospital infrastructure via PFI. Whilst this was very costly and reduced bed capacity, the Labour government funded the NHS adequately to manage the additional costs and to control backlog maintenance and waiting lists. The counter account shows the results when policies changed with the Coalition and Conservative governments. Increases in annual funding fell, and when the PFI policy was cancelled in 2012 there was no adequate replacement. Consequently, costs and backlog maintenance started to grow. As a consequence, although the government rhetoric is one of patient choice across different publicly funded providers, in reality the only choice patients have for prompt treatment is whether they are willing and able to pay for private health care. Such a scenario increases health-care inequalities observed during COVID-19 (Warner et al., 2022).

Whilst concerns regarding the impact of accounting for and accountability of England's PFI hospitals were identified early in the operational phase (Edwards et al., 2004), it has proved difficult to establish the effectiveness of contracts (NAO, 2011). The trend towards increasing fragmentation of scrutiny (Eckersley et al., 2014) and the difficulties of public monitoring across private groups with complex contractual arrangements means that the PFI policy has risked increased costs for the public sector due to ineffective accounting and accountability practices. At the same time there has been minimal scrutiny of the gains being made by the private sector over the life of PFI and other NHS contracts with the private sector, despite the well-publicized concerns raised about excess returns generated (CHPI, 2017), leakage of money out of the public sector system, and the development of a secondary market enabling capital gains to be made (Whitfield and Smyth, 2019).

CONCLUSION

This study provides counter evidence about NHS performance and spending to challenge prevailing government rhetoric about the catchup on elective care to be provided post COVID-19. It has shed some light on the deficits in NHS infrastructure funding and investment over the past decade, which have suffered from a lack of visible and joined-up public accountability. In line with Lapsley (2020), it indicates that broad and transparent accountability is needed beyond just the detailed accountability mechanisms that Leoni et al. (2021) note have become the norm during and after the pandemic.

Effective public accountability is particularly necessary given that the UK government account downplays the significance of financialization in relation to its delivery plan for post-COVID-19 activity. The references to additional funding being made available to tackle lack of capacity and backlog, better provision of elective care, and better patient information are unsurprisingly focused on improving performance. However, the plan overtly states that patients will be able to choose to use the publicly funded part of the private sector as part of the government's agenda for transforming patient choice. This ties in with the neoliberal agenda that infrastructure policies and the related role of infrastructure asset management funds are needed more than ever over the foreseeable future to meet the growing global infrastructure gap. Therefore consideration of financialization and its implications for managing public sector procurement should be an integral part of any high-level public accountability system.

This study paves the way for future research into public health care and health inequalities through further counter-accountability studies in the broadest sense. Social care, public health initiatives, general practitioners, dentistry, and peripheral services such as audiology and optometry are all areas where the boundaries between public and private sector provision are becoming increasingly more blurred due to funding shortages, and where health inequalities are likely to increase due to lack of individual funds.

It is essential in today's financialized world to take a wider view in evaluating public policies which may depend on private providers, including equity shareholders and other financiers, as key stakeholders, so that a balanced assessment can be made of policy performance. Such an assessment should consider that if private finance is to be used then assessing a fair return is needed; equally public opinion wants to see a transparent allocation of taxpayers’ money to health-care services. In the case of NHS Trusts and capital investment in hospitals, strong oversight and rigorous policy evaluation are particularly important given that over the next decade the cost of private sector involvement will increase, contracts for many hospitals will reach termination, and public funding is likely to be in short supply.

Biography

Anne Stafford ([email protected]) is at Alliance Manchester Business School.

REFERENCES

- 1 https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/02/nhs-publishes-electives-recovery-plan-to-boost-capacity-and-give-power-to-patients/

- 2 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-confirms-37-billion-for-40-hospitals-in-biggest-hospital-building-programme-in-a-generation

- 3 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/eight-new-hospitals-to-be-built-in-england

- 4 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/build-back-better-600-million-to-upgrade-and-refurbish-nhs-hospitals; Funding allocated to NHS trusts to upgrade and refurbish hospitals (publishing.service.gov.uk)

- 5 NHS Trusts can take two forms. They were set up by the Conservative government in 1991 and controlled by government. In 2004 the Labour government introduced Foundation Trusts, which have more autonomy and independence over their actions, and as a consequence have introduced more fragmentation into health-care delivery. For simplicity and the purposes of this paper, both types of Trust are simply referred to as ‘Trusts’.

- 6 https://data.oecd.org/healtheqt/hospital-beds.htm

- 7 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/trusts-deficit

- 8 Some projects provide only a new centre or a new ward rather than a complete new hospital.

- 9 In 2023 there were 220 general acute hospitals, 49 specialist hospitals, and 246 community hospitals according to the NHS website: https://www.england.nhs.uk/nhsbirthday/about-the-nhs-birthday/nhs-in-numbers-today/)

- 10 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/england-2021-22

- 11 This calculation has been adjusted to exclude (a) the years before PFI projects reached steady state in 2012/13 and (b) the two years 2020/21 and 2021/22 due to the effect of the extra funding for COVID-19.

- 12 The issue of whether the facilities remain fit-for-purpose when treatments and policies change over time but the PFI contract does not is valid but beyond the scope of this study.

- 13 This hospital is scheduled to be replaced by one of the 40 new hospitals promised by the government.