The Accountability System for Material Misstatements and Executive Pay Performance Sensitivity: A Quasi-natural Experiment

Dr Wenjun Liu acknowledges financial support from the the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 71702032); the Humanities and Social Science Project of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 21YJC630085), and the Science and Technology Innovation Special Fund of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Grant No. KFb22107XA). Dr June Cao acknowledges financial support from Jiangsu University Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (Grant No. 2022SJYB0354), Nanjing Audit University Research and Cultivation Program for Young Teachers (Grant No. 2021QNPY013), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22BGL078), and the School of Accounting, Economics and Finance of Curtin University.

Abstract

This study examines the impact of the accountability system for material misstatements (ASMM) on the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings in China. Using a difference-in-differences model, we find that the ASMM significantly decreases the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings, which we attribute to the monitoring and unintended effects of the ASMM. As executives’ cost to manage reported earnings for more bonuses is significantly heightened by the ASMM, their high compensation sensitivity to reported earnings, which contain earnings management, reduces. The unintended consequence is that executives’ risk aversion is also incentivized to preserve performance pay while the ASMM restricts earnings management, and boards reduce executives’ compensation sensitivity to accounting earnings to encourage their risk taking. These phenomena are more pronounced in companies with high agency conflict, audited by non-Big 4 auditors, and less followed by analysts. The results indicate that corporate governance reforms that introduce personal responsibilities in China can improve the accuracy of accounting earnings but decrease the efficiency of assessing executive hard work. The board reacts to this change by increasing the role of stock returns in executive compensation contracts. This is consistent with the view that the principal dynamically adjusts executive compensation contracts to make them incentive compatible (Tirole and Laffont, 1988; Hall and Knox, 2004; He, 2011). Our study provides critical implications for the importance of institutional environments to impact governance reforms in emerging markets and beyond.

Executives are motivated to use financial misstatements to distort accounting earnings, one of the most widely used performance proxies in executives’ compensation contracts (Sloan, 1993; Banker et al., 2009), for various, complex reasons.1 In recent years, information disclosure violations have become the most common violations committed by companies in China's capital markets.2 In response, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has implemented an accountability system for major misstatements (ASMM). This ground-breaking initiative introduces executives’ personal responsibility into corporate governance reform (ASMM).

This study first investigates whether personal responsibility measures introduced via the ASMM are an effective means to curb executive misstatements. If misstatements are significantly reduced and corporate disclosure becomes more transparent, it may affect the weight of accounting earnings in compensation contract design. The sensitivity of executive compensation to corporate performance is important to enhancing executives’ willingness to become more productive. We thus posit that the introduction of ASMM could affect executive pay-performance sensitivity.

To enhance investor protection (Liao et al., 2022), most regulatory reforms have focused on strengthening board independence and refining equity structures (Dahya and McConnell, 2007; Kumar and Sivaramakrishnan, 2008). However, Kumar and Sivaramakrishnan (2008) find that boards composed of more independent directors have less effective oversight. The changes that mandate particular board structures may cause firms to deviate from their optimal governance structures for individuals (Gillan and Martin, 2007). Initial corporate governance reforms have been found to have a limited effect. The concerns of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the general public about investor protection and information quality, in particular, were rampant after the Enron and WorldCom incidents. This resulted in the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), which introduces personal liabilities into corporate governance and provides a new global corporate governance reform idea3 in response to public concerns and the SEC's pressure for corporate governance reform (Fram, 2004).

This accountability approach subjects executives to higher violation costs and legal risks (Bargeron et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2013). Theoretically, this could help promote executive compliance and strengthen corporate governance. It has been implemented in the US Dodd-Frank Act (DFA) (e.g., Section 954). Moreover, the introduction of personal responsibility is more common in emerging capital markets. India introduced Section 23E to expand the personal liabilities of management, boards, and auditors in 2004 (Koirala et al., 2020) and introduced personal liability for independent directors in 2014 (Naaraayanan and Nielsen, 2021). However, evidence for the impact of the introduction of personal responsibility measures on corporate risk taking is mixed and may deter individuals from serving as independent directors. As the second largest economic entity and the largest emerging capital market, the Chinese capital market is rapidly developing but suffers from low litigation risk and weak investor protection (Lennox and Wu, 2022), leading to an opaque disclosure environment. To restrain executives’ information manipulation, the ASMM, which strengthens executives’ responsibility for information disclosure, was introduced by the CSRC for the first time in late 2009 in China.

In late 2009, the CSRC issued the Announcement on Preparation of the Annual Reports and Related Work of Listed Firms in 2009 (Announcement No. 34), which required listed companies in China to establish an accountability system for material misstatements of information disclosed in their annual reports (ASMM).4 The ASMM is a mechanism that outlines the accountability relating to, and punishment for making, material misstatements in financial reporting. This system enforces penalties such as fines, demotions, dismissals, and criminal liability for executives and other responsible parties found guilty of misstatements. The outcomes of these penalties are made public, adding to the system's effectiveness in increasing executive responsibility for misstatements. Through ASMM, the CSRC aims to increase executives’ responsibility for misstatements by tracking and disclosing accountability for material misstatements (CSRC, 2009).

However, does the introduction of executive information disclosure responsibility contribute to corporate governance? Radcliffe et al. (2017, p. 622) refute the view that ‘greater accountability is key to successful corporate reform’. We empirically explore whether and how the ASMM affects the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings. We focus on the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings because, first, the quality of accounting information plays a critical role in determining the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting performance (Healy, 1985; Carter et al., 2009; Adut et al., 2013). Previous studies document that earnings-based compensation contracts can lead to earnings management and fail to promote genuine corporate performance (Healy, 1985; Guidry et al., 1999; Bergstresser and Philippon, 2006). When earning-based contracts fail to incentivize executive hard work for genuine performance, which may lead to earnings management, the board ultimately reduces pay-performance sensitivity.

Second, when executives’ responsibility for information disclosure is substantially enhanced, do boards weigh accounting earnings more heavily when formulating contracts? Previous studies respond to this question by examining the economic consequences of SOX, but the evidence is inconclusive. On the one hand, the literature shows that the implementation of SOX can limit discretionary accruals and promote the alignment of interests between executives and shareholders. Boards thus increase the weight of accounting earnings in compensation contracts (Carter et al., 2009; Chen, Jeter, and Yang, 2015). On the other hand, some studies find that SOX, which focuses on ex post penalties, may aggravate information manipulation (Goldman and Slezak, 2006), reduce executive risk taking (Cohen et al., 2013), and reduce executive pay-performance sensitivity (Cohen et al., 2013). The main reason for these inconclusive findings may be the lack of an ideal control group in the US (Dey, 2010). This issue continues to pose a difficult challenge to those investigating the real impact of SOX, an important corporate governance reform, on executive pay-performance sensitivity. Contrarily, the time at which companies implement an ASMM demonstrates staggered features, providing a quasi-natural experiment setting to utilize the powerful staggered difference-in-differences (DiD) technique. We consider corporate governance reform with respect to the ASMM a quasi-natural shock to investigate how heightened executive responsibility affects executive pay-performance sensitivity.

Our research question is thus an empirical issue. First, the ASMM's strict supervision may limit executives’ opportunities to misreport and thus restrict their suboptimal decisions which decreases the firm's value. This can help improve the quality of information, encourage firms to report accounting earnings that realistically reflect their executives’ efforts, and consequently, increase the weight accorded to accounting performance in executive compensation contracts (Baiman and Verrecchia, 1995; Carter et al., 2009). However, previous studies document that executives engage in earnings management when the bonus payment is high (Jongjaroenkamol and Laux, 2017). Their accounting manipulation will reduce the board's ability to detect poorly performing executives (Jongjaroenkamol and Laux, 2017). Dechow et al. (2010) also argue that informed boards tolerate executives reporting higher earnings for bonuses. As ASMM restricts executives’ ability to manage earnings for more bonuses, the high sensitivity of executive compensation to reported earnings may be reduced. Additionally, executives are found to make risk-averse and myopic investments in response to short-term pressures (Asker et al., 2015). The ASMM restricts executives from relieving investment pressure by making misstatements. Investors, whose attention has been attracted by the ASMM, may also create further short-term pressure on executives to perform, leading to risk-averse investment decisions. These behaviours distort the reflection of executive efforts derived from accounting earnings, and, in turn, boards reduce executives’ compensation sensitivity to accounting earnings.

Examining a sample of non-financial and non-special treatment companies listed in the A-share market from 2007 to 2021 in China, we find that the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings significantly decreases after a firm establishes the ASMM. This finding is stable through a series of robustness tests, including the parallel trend tests, propensity score matching, a placebo test, Heckman tests, the exclusion of concerns on the nature of property rights, state-owned enterprise clawback system, anti-corruption initiatives and seasoned equity offerings, alternative measures of firm performance, alternative measures of dependent variables, and replacement of the regression model. We further explore the underlying economic mechanism through which the ASMM affects executive pay-performance sensitivity. We find that the decreased earnings management and risk-taking activities after the ASMM are underlying mechanisms through which executive pay-performance sensitivity decreases.

Since the ASMM's strict economic and reputation penalties prevent executives from managing accruals earnings, we argue that this effect of the ASMM on executives’ compensation sensitivity to accounting earnings is higher in firms with higher agency conflict between shareholders and managers. This is because executives are more likely to manage earnings for performance compensation in companies with higher agency conflicts. Moreover, as the strict external environment can restrain earnings management (Yu, 2008), we argue that reducing the ASMM on executives’ high compensation sensitivity to reported earnings, which is manipulated for high compensation, may be more pronounced in companies with a weak accounting environment. More specifically, auditors and analysts have a public scrutiny effect. Big audit firms provide higher-quality audit services than small ones, and higher analyst coverage is associated with more transparent corporate disclosure (Yu, 2008; Samuels et al., 2023). As Big 4 auditors and high analyst coverage exert a higher external monitoring effect, which can restrict executives’ ability to manage earnings for high-performance compensation, we find that the baseline result is stronger in firms with non-Big 4 auditors and that are less followed by analysts.

Given that accounting earnings and stock returns are two important indicators of executive effort (Baiman and Verrecchia, 1995), we further investigate whether boards are more likely to rely on stock returns if the ASMM leads to accounting earnings having a decreased effect on executive compensation contracts than if it does not. Our motivation for this investigation is that equity-based indicators are more comprehensive and timelier in reflecting firm performance, and they incentivize executives over a more extended period than other indicators (Leone et al., 2006). At the same time, as cash and stock are two main forms of executives’ compensation, we also identify whether the ASMM leads to a shift in compensation between cash and equity compensation. We provide no evidence that the ASMM promotes executives’ higher total compensation sensitivity to stock returns. However, we find the sensitivity of both executives’ cash and equity compensation sensitivity to stock returns increases after establishing an ASMM after we split total compensation into cash and stock proportion. This suggests that the board weighs and dynamically adjusts different performance indicators (Tirole and Laffont, 1988) of executive incentives after the firm implements an ASMM. We also consider the possibility that the ASMM might induce real earnings management that is more hidden to preserve high-performance compensation, to which boards may respond by reducing the weight of accounting earnings in compensation contracts. We rule out the alternative explanation as we find there is no change in real earnings management after establishing the ASMM.

Our study makes four contributions to the literature and has practical implications for regulators. First, whereas previous studies show that corporate governance affects executive pay-performance sensitivity (Goldman and Slezak, 2006; Carter et al., 2009), we find that corporate governance reform aimed at introducing executives’ responsibility fails to enhance the role of accounting information in executive compensation contracts. The reasons are complex. One reason is that the ASMM suppressed accrual earnings management and increased the accuracy of reported earnings, reducing executive compensation sensitivity to reported earnings as executives overestimating reported earnings caused previously exorbitant pay sensitivity to reported earnings. Another reason is that the ASMM induces risk aversion in executives, making boards reduce the weight of accounting earnings in executives’ compensation contracts. Here, we develop new insights by providing evidence on the relationship between corporate governance reform, earnings management, risk taking, and executive pay-performance sensitivity in emerging capital markets.

Second, although the ASMM is a key corporate governance regime first proposed in response to information disclosure by the CSRC, few studies examine its governance effects. In contrast, we conduct a preliminary examination of the corporate governance effects of this important mechanism. Accordingly, our study provides important empirical evidence and has implications for regulators regarding the real impact of corporate governance reform.

Third, phenomena such as executives’ overinvestment driven by high levels of monetary compensation (Xu and Xia, 2012), earnings management (Lang et al., 2006), and insider trading (Zhu and Wang, 2015) in emerging markets with weak investor protection raise concerns about the failure of the compensation contract and questions about the board's role in compensation contracts and corporate governance. We find that as executives respond to the ASMM with sub-optimal investment decisions, boards reduce the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings and increase the weight of stock returns in compensation contracts. This demonstrates their ability to dynamically adjust the design of compensation contracts to corporate governance practices and executive behaviour (Harris and Holmstrom, 1982; Tirole and Laffont, 1988).

Finally, by examining how ASMM, a punitive mechanism, and pay for accounting earnings, an incentive, are synergistic or mutually exclusive, we provide an essential reference for regulators in emerging markets to improve the regulatory mechanism for information disclosure and for listed companies to increase the efficiency of their compensation contracts and their incentives for executives.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Previous executive compensation research based on agency theory (Jensen and Murphy, 1990) advocates linking executive compensation to accounting earnings to achieve incentive compatibility and maximize firm value. Earnings-based compensation can also protect executives from the damage to their interests caused by large fluctuations in stock prices and market factors (Sloan, 1993).

In contrast, more recent studies find that compensation contracts based on accounting earnings can exacerbate firm information asymmetries and aggravate agency problems due to contractual incompleteness, such as executives’ performance manipulation through earnings management (Guidry et al., 1999), the excessive allocation of merger prices to goodwill (Shalev et al., 2013) to maximize short-term bonuses and compensation, and inducing risk-averse executives to abandon high-risk investment strategies (Xue, 2007).

To mitigate agency conflicts and improve the efficiency of compensation contracts, previous studies explore the role of corporate governance in determining executive pay-performance sensitivity (Cornett et al., 2008; Carter et al., 2009; Chen, Jeter, and Yang, 2015; Qiu and Steve, 2018). Theoretically, earnings-based compensation contracts appear to be ineffective because of executives’ earnings manipulation. However, company boards should increase their reliance on accounting earnings and increase pay-performance sensitivity when executives’ opportunistic behaviour is curbed, and accounting earnings better reflect those executives’ efforts (Carter et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, relevant research in the context of SOX provides conflicting evidence on this issue. Some scholars support the ‘governance view’. That is, the implementation of regulatory reform increases scrutiny of executive manipulation and improves the quality of financial reports (Chen, Jeter, and Yang, 2015), prompting firms to increase their emphasis on accounting earnings in bonuses and compensation contracts (Carter et al., 2009). However, those scholars’ findings are challenged by the lack of a control group within the US, which makes it difficult to identify the true impact of SOX (Dey, 2010).

Another group of academics argues that through modelling analysis, SOX, which aims to reduce financial misreporting through regulation and ex post penalties, can exacerbate information manipulation, reduce firm value (Goldman and Slezak, 2006), and reduce executive pay-performance sensitivity (Qiu and Steve, 2018), supporting the ‘agency view’. Some empirical research even finds that firms in the post-SOX period shifted from accrual-based to real earnings management (Cohen et al., 2008); in addition, they decreased their research and development expenditures, capitalized investments, and made investments related to mergers and acquisitions, decreasing the performance sensitivity of executive compensation (Cohen et al., 2013) and indicating more severe agency conflicts than had existed before SOX.

Moreover, Gayle et al. (2022) document that although SOX reduces the conflict of interest between CEOs and shareholders, it also leads to increased agency costs due to the higher risk premiums demanded by CEOs to maintain their alignment with shareholders’ interests. Hence, neither analytical nor empirical studies make consistent findings on the impact of corporate governance mechanisms aimed at improving the quality of corporate disclosure and executive pay-performance sensitivity.

The introduction of the ASMM in the Chinese capital market provides a valuable context for clarifying this issue. First, the ASMM is a corporate governance reform established by Chinese companies in staggered stages, so can be considered as multiple shocks. Our DiD model can effectively prevent confounding events from influencing our findings, helping us identify the real effect of the system and clarify the causal relationship. Previous SOX-based studies have not addressed this. Thus, our use of the ASMM context not only helps clarify the controversy in the literature on corporate governance and the pay-performance sensitivity of executives, but also provides evidence from emerging capital markets for use in studies related to the economic consequences of corporate governance reforms.

Second, China is an emerging capital market with weak legal enforcement and investor protection (Chen et al., 2016; Lennox and Wu, 2022), low information quality, and widespread earnings management (Lang et al., 2006; Wang and Wu, 2011), making it quite different from developed capital markets such as the US and the UK (Cheng et al., 2022). For these reasons, the governance effects of introducing personal executive responsibility into corporate governance reforms may differ between emerging and developed capital markets. Our study identifies implications and directions for corporate governance reform and relevant studies in emerging capital markets.

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

Institutional Background

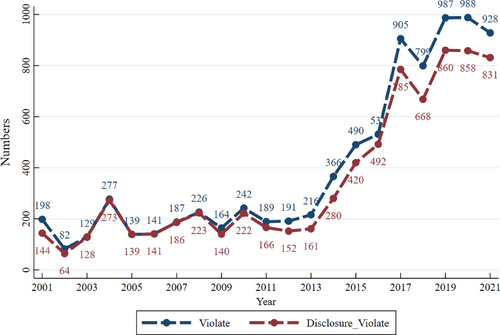

The ASMM is a penalty for material misstatements made by companies, with executives and others responsible held accountable and the outcome made public. The Chinese capital market has experienced countless misstatement scandals, drawing constant attention from regulators. As shown in Figure 1, penalties imposed by the CSRC on listed companies for information disclosure violations have increased considerably in the past two decades and accounted for a significant proportion of corporate violations.

Note: Figure 1 summarizes the statistics on the administrative penalties imposed by the CSRC on listed companies for violations, in particular, information disclosure violations, in each year from 2001 to 2021. The blue dashed line plots the trend in administrative penalties imposed by the CSRC on listed companies for violations by year, while the red dashed line shows the trend in disclosure violations imposed by it.

To enhance executives’ information disclosure responsibilities and quality in annual reports, the ASMM was first introduced in late 2009, with the CSRC's Announcement on Preparation of the Annual Reports and Related Work of Listed Firms in 2009 (Announcement No. 34)5 and has been established by listed firms since 2010. With an ASMM, companies are required to truthfully provide an itemized disclosure of the causes and effects of misreporting in their annual reports, the accountability measures taken by the board against those responsible, and the outcomes of handling. Compared with previous regulatory reforms, which mainly were aimed at the board of directors (Kumar and Sivaramakrishnan, 2008; Liao et al., 2022) and focused on financial fraud (Yang et al., 2017), this approach not only increases executive responsibility for information disclosure but also represents a new chapter in the governance of companies’ disclosure of irregularities in the Chinese capital markets.

The ASMM has three main features. First, the scope of accountability for misstatements is broad. The accountability scope includes material misstatements, including corrections of material accounting errors, additions of material omissions, and revisions of earnings forecasts during the annual, semi-annual, and quarterly reports. Second, the target of accountability is comprehensive. Executives such as the chairman, CEO, CFO, and the head of the accounting department are responsible for the truthfulness, accuracy, completeness, timeliness, and fairness of the information disclosed and the financial reporting.6 Third, the accountability measures are severe. These accountability measures include, but are not limited to, financial penalties, notification of criticism, demotion, and dismissal. Depending on the circumstances of the misstatement, accountability measures can be combined, and misstatements can even be referred to the judicial authorities if they are serious and suspected of being criminal. As a result, those responsible for disclosure violations have greater accountability, and the accountability results disclosed in annual reports are more widely disseminated under the ASMM than in the past.

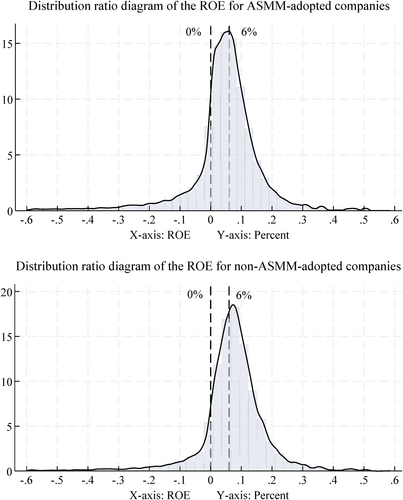

The ASMM also reforms corporate governance by combining public and private enforcement. On the one hand, the ASMM proposed by the CSRC is mandatory to a certain extent. Ideally, all companies should actively follow the call to establish an ASMM. However, due to China's weak law enforcement environment, listed companies did not implement the policy simultaneously when it was introduced. Instead, the introduction was staggered and some companies have yet to establish it, despite the CSRC stressing in several announcements that listed companies should establish it. Moreover, due to resource constraints, CSRC supervision of companies is selective and lagging (Xu and Xu, 2020). The supervision of companies’ establishment of ASMM may need to be delegated to local regulatory bureaus. Some local regulators of the CSRC (e.g., the Shenzhen Bureau) have issued announcements clearly indicating that they will strictly review and punish companies that fail to establish an ASMM,7 but more regional regulators do not require this. As a result, about 30.4% of companies still have not established an ASMM (as shown in Table 1). Our study uses companies with an ASMM in 2010–2021 as the treatment group and companies without an ASMM as the control group.

| YEAR | N | TREAT = 1 | TREAT = 0 | Percentage | TREAT×POST = 1 | TREAT×POST = 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 1,230 | 1,014 | 216 | 82.40% | 0 | 1,230 |

| 2008 | 1,396 | 1,163 | 233 | 83.30% | 0 | 1,396 |

| 2009 | 1,467 | 1,230 | 237 | 83.80% | 0 | 1,467 |

| 2010 | 1,477 | 1,229 | 248 | 83.20% | 1,062 | 415 |

| 2011 | 1,525 | 1,254 | 271 | 82.20% | 1,162 | 363 |

| 2012 | 1,556 | 1,270 | 286 | 81.60% | 1,225 | 331 |

| 2013 | 1,562 | 1,262 | 300 | 80.80% | 1,240 | 322 |

| 2014 | 1,505 | 1,199 | 306 | 79.70% | 1,188 | 317 |

| 2015 | 1,510 | 1,180 | 330 | 78.10% | 1,167 | 343 |

| 2016 | 1,644 | 1,205 | 439 | 73.30% | 1,191 | 453 |

| 2017 | 1,812 | 1,198 | 614 | 66.10% | 1,178 | 634 |

| 2018 | 2,123 | 1,259 | 864 | 59.30% | 1,243 | 880 |

| 2019 | 2,175 | 1,249 | 926 | 57.40% | 1,241 | 934 |

| 2020 | 2,307 | 1,209 | 1,098 | 52.40% | 1,209 | 1,098 |

| 2021 | 2,742 | 1,199 | 1,543 | 43.70% | 1,199 | 1,543 |

| N | 26,031 | 18,120 | 7,911 | 69.60% | 14,305 | 11,726 |

- Note: Table 1 reports the year distribution of our sample. TREAT equals one if the firm establishes an ASMM in 2010–2021, and zero otherwise. Percentage denotes the proportion of treatment groups in that year. POST equals one when the firm year is in the post-establishment period, and zero otherwise.

Hypothesis Development

A weak financial reporting environment encourages executive misstatement (Jongjaroenkamol and Laux, 2017) and suboptimal decisions not consistent with firm value (Cheng et al., 2013), causing accounting earnings to deviate in a manner that truly reflects executive effort. We argue that the ASMM limits executives’ opportunistic behaviour and promotes the board's use of earnings-based compensation contracts. Compensation contracts based on accounting earnings are widely used in the Chinese capital market. Nevertheless, a lack of effective monitoring in the Chinese market can motivate executives to act opportunistically, leading to repeated misstatements and strong incentives to conceal information. These motivations, which are complex, may include meeting earnings expectations (Barua et al., 2010), maximizing short-term bonuses (Guidry et al., 1999), appropriation (Nagar and Schoenfeld, 2021), empire building (Hope and Thomas, 2008), insider trading (Frankel and Xu, 2004), tax avoidance (Kim et al., 2011), and external funding (Dordzhieva et al., 2022). Consequently, accounting information can distort agency conflicts between shareholders and executives. Information disclosure plays a significant role in the board's supervision of executives (Franco et al., 2013), but the board's access to internal information is limited. This impedes its oversight of executive behaviour and leads to the failure of compensation contracts that are based on accounting earnings.

The ASMM, with its broader scope of accountability, more comprehensive accountability targets, and more severe accountability measures, closely links executives’ personal wealth and professional reputation with future development in terms of the quality of the information they provide. This can increase the costs of misstatement, encouraging rational executives not only to reduce any incentives to misstate but also to improve the accounting information system, thereby enhancing the quality of accounting information. When the accuracy of reported earnings improves, its weight in compensation contracts can increase (Baiman and Verrecchia, 1995).

Moreover, when the ASMM strengthens accountability penalties for executive misstatements and limits executives’ use of private information to obtain excessive returns, it encourages executives to abandon their hold on internal information, reducing information asymmetry between shareholders and management and strengthening the board's regulatory function (Franco et al., 2013). Accordingly, if the ASMM's governance of information disclosure is conducive to limiting the distortion of accounting earnings, this will improve accounting earnings’ accurate reflection of executive efforts and strengthen the board's oversight of executive conduct. Consequently, it will facilitate the use of accounting earnings in compensation contracts, as reflected in the increased sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings. Therefore, Hypothesis 1a is formulated as follows.

H1a.The sensitivity of executives’ compensation to accounting earnings increases after the implementation of ASMM.

However, the restriction of ASMM on corporate misreporting may also reduce executive pay-performance sensitivity, as empirical evidence shows that executives manipulate earnings for high-performance compensation (Guidry et al., 1999; Cornett et al., 2008). Not only that, the ASMM may intensify risk-aversion behaviour among executives, prompting the board to reduce the weight of accounting earnings in executive compensation contracts.

Excessively high-powered incentive compensation will cause aggressive misreporting (Marinovic and Povel, 2017; Jongjaroenkamol and Laux, 2017). Several studies provide evidence that bonus payments provide executive incentives to meet earnings benchmarks (Matsunaga and Park, 2001; Dechow et al., 2010). To achieve the potential earnings benchmark for bonus payments, executives are motivated to manage earnings (Guidry et al., 1999) and reduce the board's ability to detect and dismiss poor-performing executives (Jongjaroenkamol and Laux, 2017). Not only that, boards were also found to conspire with executives to report more earnings. Dechow et al. (2010) show that managers’ report securitization gains instead of accounting earnings when earnings are low or negative, in order to report larger gains, and that more independent or informed boards do not intervene in the CEO's high compensation sensitivity to reported securitization gains. Moreover, Chen and Lu (2011) find in the context of China that companies manage earnings to enhance compensation, and earnings-based incentive compensation leads to more income-increasing earnings management. We argue that if executives’ ability to manage reported earnings is restricted, high compensation sensitivity to reported earnings, usually overstated for more bonuses, will reduce.

More specifically, the ASMM may restrict executive manipulation of discretionary accruals to overstate reported earnings when executives are incentivized by bonus-based compensation. This will reduce their compensation sensitivity to reported earnings. Accrual-based earnings management, which is the most common tool to manage earnings, often contradicts the Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises (ASBE) (Ho et al., 2015) and is susceptible to producing misstatements (Dechow et al., 1996), and thus is more likely to be penalized by the ASMM. While boards may not sufficiently implement the ASMM because they are aware of and tolerating executives’ earnings management for more reported earnings (Dechow et al., 2010), the ASMM may also play a governance role as external stakeholders will monitor the execution of the system. The CSRC requires companies to disclose their establishment of ASMM publicly, and some local supervision bureaus (e.g., the Shenzhen Bureau) of the CSRS also include the implementation of ASMM in their routine inspections of listed companies. The ASMM implemented by companies suffers from public supervision. Although securities regulation is not efficiently enforced in China (Song and Ji, 2012), stakeholders and potential investors of companies also monitor the execution of the ASMM and will consider any misstatement they uncover when making investment decisions. Hence, companies establishing an ASMM do so with increased scrutiny, which means executives have to give up their manipulation of discretionary accruals. This will reduce executives’ compensation sensitivity to reported earnings if they previously were managing earnings for high bonus-based compensation.

In addition, executives sacrifice relatively valuable long-term investments to meet short-term performance goals (Graham et al., 2005; Chen, Cheng, Lo, and Wang, 2015; Kraft et al., 2018). Even in the absence of earnings manipulation, widespread risk aversion and moral hazard issues among executives can still lead to a biased reflection of accounting earnings in a manner that obscures executive efforts. Given a strong incentive to circumvent oversight for self-interested purposes, executives whose opportunistic behaviours are limited by the ASMM may engage in alternative undesirable behaviours. Specifically, executives are found to shift to a more myopic investment strategy to preserve earning-based compensation when accrual-based earnings management is dissuaded (Biddle et al., 2024). The ASMM restricts companies from hiding negative information and increases executive pressure to maximize short-term performance, which may lead to executives’ increased risk aversion and moral hazard. As a result, boards reduce the weighting of accounting earnings in compensation contracts (Peek and Moers, 2001). This is because positive net present value investments that enhance firm value are often high-risk projects that involve expensing upfront investments and long payback periods, resulting in poor short-term accounting earnings. High risk also implies uncertainty about high returns and the risk that firms will invest unsuccessfully and experience financial distress (Holmstrom, 1989; Tian and Wang, 2014), along with the possibility that executives will suffer reputational damage and mandatory departures because of their failed decisions (Lehn and Zhao, 2006). Furthermore, the ASMM may increase the likelihood that external information users will view stringent governance of misstatements as a signal of high quality. If establishing the ASMM attracts attention from investors and increases the consideration of accounting earnings in investment decisions, it may also increase the pressure on executives for short-term performance and prompt short-termism.

To avoid an earnings decrease and improve short-term performance, executives may reduce their exposure to high-risk investments and choose suboptimal investments (Chen, Cheng, Lo, and Wang, 2015). To reduce executives’ risk aversion and myopic behaviour, the board will reduce the weight of accounting earnings in compensation contracts, manifested in executive compensation's reduced performance sensitivity. Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis H1b.

H1b.The sensitivity of executives’ compensation to accounting earnings decreases after the ASMM implementation.

SAMPLE SELECTION AND MODEL

Sample

China's accounting standards, implemented in 2007, have converged with the International Financial Reporting Standards (Zhang, 2022). Considering the impact of the differences in calculation standards for financial indicators, our sample begins in 2007. Our sample selection is described in detail in Table A2 of the Appendix. First, to explore the impact of ASMM establishment on executive compensation contracts, we select a sample from 2007 to 2021 (44,303). Second, we eliminate companies listed on the B-share market (1,549), companies from financial industries (943), and observations with missing financial data (5,826). As in Nienhaus (2022), firms without at least one observation before and after the year of ASMM establishment are eliminated to improve the validity of the DiD model (9,954). We eventually obtain 26,031 valid firm-year observations. Among them, 18,120 observations, representing 1,359 listed companies, are in the treatment group. The observations for the control group are 7,911, representing 1,604 listed companies. The data relating to ASMM establishment are manually extracted from the Cninfo website,8 and other data are from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database. In addition, to exclude the effect of outliers, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% percentiles, and all regressions are clustered at the firm level for standard errors.

Model Specification

The dependent variables, TPAY1 and TPAY2, refer to the logarithm of executives’ annual compensation and the logarithm of the annual compensation of the top three executives, respectively.10 Referring to the method of Chan et al. (2012), TREAT equals one if the company is an ASMM adopter (treatment group) and equals zero if it is instead a non-adopter (control group). POST is an indicator variable that identifies the pre- and post-adoption periods, which equals one for a firm year in which the ASMM adopters have ASMM provisions in place, and zero otherwise. To identify the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings, we construct the variable return on assets (ROA), defined as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) divided by total assets. The coefficient α1 of TREAT×POST×ROA is the critical indicator of interest in this paper, measuring how and to what extent ASMM affects the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings.

Further, referring to Ke et al. (1999) and Rhodes (2016), we control for a range of corporate finance and governance characteristics, including firm size (SIZE), leverage (LEV), sales growth (GROWTH), market-to-book ratio (MTB), volatility of return on assets (varROA), R&D investment (RND), nature of property rights (SOE), years of CEO tenure (CEOTENURE), duality of chairman and CEO (DUAL), board size (BOARD), the proportion of independent directors (INDE), institutional shareholdings (INSSHR), and whether the auditors are from Big 4 accounting firms (BIG4). Following Banker et al. (2009) and Rhodes (2016), we control for the interaction term between the above control variables and ROA to capture cross-sectional differences in executive pay-performance sensitivity. The variables are defined in Table A1 of the Appendix. There may be unique characteristics of firms and years that are not time-varying and unobservable, leading to endogeneity issues in the regressions. For this reason, we control for firm and year-fixed effects.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample by year. Since 2010, companies’ establishment of the ASMM has been staggered, facilitating our construction of a DiD model and alleviating the endogeneity problem. Although a considerable proportion of enterprises has not established the ASMM, the annual distribution shows that the sample of the treatment group in each year accounts for 69.60%, indicating that most firms have complied with the requirements of the CSRC and declared their intention to establish the ASMM.

Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables in Model (1). Panel A shows the descriptive statistics of the full sample. The mean of the logarithm of the compensation and the logarithm of the top three executive compensation are 16.86 and 16.30, respectively, with standard deviations of 2.603 and 2.877, showing a large gap in executive compensation between different firms. The ASMM has been established by 69.6% of the firms, which are classified as the treatment group, whereas 55% of the observations are from the year the ASMM was established or in subsequent years. In addition, the descriptive statistics of other variables are consistent with recent studies focused on the Chinese capital market (Yao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020).

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics of full sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLE | N | MEAN | MIN | P25 | MEDIAN | P75 | MAX | S.D. |

| TPAY1 | 26,031 | 16.86 | 13.03 | 14.95 | 15.85 | 18.87 | 22.97 | 2.603 |

| TPAY2 | 26,031 | 16.30 | 12.44 | 14.16 | 15.01 | 18.63 | 22.91 | 2.877 |

| TREAT | 26,031 | 0.696 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.460 |

| TREAT×POST | 26,031 | 0.550 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.498 |

| ROA | 26,031 | 0.074 | –0.275 | 0.045 | 0.073 | 0.109 | 0.279 | 0.074 |

| SIZE | 26,031 | 22.23 | 19.24 | 21.25 | 22.08 | 23.04 | 26.28 | 1.389 |

| LEV | 26,031 | 0.480 | 0.069 | 0.318 | 0.481 | 0.636 | 1.030 | 0.213 |

| GROWTH | 26,031 | 0.203 | –0.675 | –0.033 | 0.105 | 0.274 | 4.464 | 0.604 |

| MTB | 26,031 | 2.109 | 0.847 | 1.213 | 1.602 | 2.338 | 10.98 | 1.586 |

| varROA | 26,031 | 0.044 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.048 | 0.484 | 0.065 |

| RND | 26,031 | 0.014 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.090 | 0.018 |

| SOE | 26,031 | 0.499 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.500 |

| CEOTENURE | 26,031 | 3.927 | 0.083 | 1.417 | 3.083 | 5.583 | 15.25 | 3.330 |

| DUAL | 26,031 | 0.214 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.410 |

| BOARD | 26,031 | 2.265 | 1.792 | 2.197 | 2.303 | 2.303 | 2.773 | 0.180 |

| INDE | 26,031 | 0.372 | 0.300 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.417 | 0.571 | 0.053 |

| INSSHR | 26,031 | 0.502 | 0.009 | 0.341 | 0.514 | 0.673 | 0.955 | 0.228 |

| BIG4 | 26,031 | 0.070 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.255 |

| Panel B: Difference in statistics between treatment and control groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLE | TREAT = 0 | TREAT = 1 | Diff. | |||

| (N = 7,911) | (N = 18,120) | |||||

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | T-value | Z-value | |

| TPAY1 | 18.13 | 17.75 | 16.30 | 15.55 | 54.89*** | 47.70*** |

| TPAY2 | 17.70 | 17.38 | 15.69 | 14.72 | 54.72*** | 47.39*** |

| ROA | 0.081 | 0.081 | 0.071 | 0.070 | 10.21*** | 14.47*** |

| SIZE | 22.18 | 21.94 | 22.24 | 22.15 | –3.17*** | –7.32*** |

| LEV | 0.430 | 0.417 | 0.502 | 0.506 | –25.45*** | –25.49*** |

| GROWTH | 0.204 | 0.130 | 0.202 | 0.094 | 0.24 | 10.66*** |

| MTB | 2.052 | 1.609 | 2.133 | 1.599 | –3.78*** | 0.89 |

| varROA | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.048 | 0.026 | –13.87*** | –13.79*** |

| RND | 0.02 | 0.016 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 35.51*** | 37.88*** |

| SOE | 0.360 | 0 | 0.560 | 1 | –30.13*** | –29.62*** |

| CEOTENURE | 3.851 | 3.417 | 3.961 | 2.917 | –2.45** | 5.66*** |

| DUAL | 0.284 | 0 | 0.184 | 0 | 18.16*** | 18.05*** |

| BOARD | 2.244 | 2.303 | 2.274 | 2.303 | –12.41*** | –13.57*** |

| INDE | 0.375 | 0.364 | 0.371 | 0.333 | 6.055*** | 7.64*** |

| INSSHR | 0.472 | 0.491 | 0.515 | 0.520 | –14.15*** | –10.72*** |

| BIG4 | 0.094 | 0 | 0.059 | 0 | 10.20*** | 10.18*** |

- Note: Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the main variables for Model (1). Panel A and Panel B present the descriptive statistics for the full sample and the univariate analysis between the treatment group and the control group, respectively. All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Panel B shows the descriptive statistics between the treatment and control groups. The mean value of the logarithm of executive compensation (TPAY1) for the treatment group is 16.30, compared to 18.13 for the control group. This indicates that the mean values of the logarithm of executive compensation are lower for the treatment group than for the control group. When one observes the medians and the compensation of the top three executives, the conclusion is also consistent. In terms of the mean and median values of the control variables, all of the variables differ significantly between the treatment and control groups. Accordingly, it is necessary to put these control variables into the model. We also mitigate this problem later using propensity score matching, the details of which are described in a later section.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

The Baseline Results

The results for H1a and H1b are presented in Table 3, Panel A. Columns (1) and (2) show the relationship between accounting earnings and executive compensation. When using TPAY1 and TPAY2 as the dependent variables and ROA as the independent variable, the coefficients of ROA are 1.183 and 1.207 at the 1% significance level. This indicates that accounting earnings are a commonly used performance indicator for listed companies in China. Columns (3) and (4) show the impact of the ASMM on executive total compensation. The coefficients of TREAT×POST show that executive compensation significantly decreases after firms establish an ASMM.

| Panel A: The impact of ASMM on the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | |

| TREAT×POST×ROA | –0.936*** | –0.984*** | –0.831*** | –0.849*** | ||||

| (–3.05) | (–2.95) | (–2.89) | (–2.72) | |||||

| TREAT×POST | –0.124** | –0.118** | –0.057 | –0.047 | –0.065 | –0.058 | ||

| (–2.37) | (–2.10) | (–0.97) | (–0.75) | (–1.13) | (–0.95) | |||

| ROA | 1.183*** | 1.207*** | 1.184*** | 1.208*** | 1.733*** | 1.785*** | –0.195 | –1.273 |

| (5.95) | (5.53) | (5.94) | (5.53) | (7.10) | (6.74) | (–0.04) | (–0.27) | |

| ROA×SIZE | 0.076 | 0.073 | ||||||

| (0.43) | (0.38) | |||||||

| ROA×LEV | –1.184* | –1.096 | ||||||

| (–1.81) | (–1.55) | |||||||

| ROA×GROWTH | 0.323 | 0.291 | ||||||

| (1.58) | (1.31) | |||||||

| ROA×MTB | 0.121* | 0.158** | ||||||

| (1.73) | (2.10) | |||||||

| ROA×varROA | –12.213*** | –13.086*** | ||||||

| (–8.50) | (–8.31) | |||||||

| ROA×RND | –3.301 | –4.543 | ||||||

| (–0.38) | (–0.50) | |||||||

| ROA×SOE | –0.626* | –0.631 | ||||||

| (–1.71) | (–1.58) | |||||||

| ROA×CEOTENURE | 0.008 | 0.007 | ||||||

| (0.18) | (0.16) | |||||||

| ROA×DUAL | 0.153 | 0.151 | ||||||

| (0.37) | (0.34) | |||||||

| ROA×BOARD | 0.906 | 1.269 | ||||||

| (1.02) | (1.30) | |||||||

| ROA×INDE | 1.270 | 1.909 | ||||||

| (0.40) | (0.55) | |||||||

| ROA×INSSHR | 0.581 | 0.842 | ||||||

| (0.61) | (0.82) | |||||||

| ROA×BIG4 | –0.697 | –0.788 | ||||||

| (–1.18) | (–1.20) | |||||||

| SIZE | 0.737*** | 0.756*** | 0.739*** | 0.758*** | 0.742*** | 0.761*** | 0.734*** | 0.753*** |

| (17.78) | (16.44) | (17.82) | (16.47) | (17.85) | (16.51) | (16.54) | (15.25) | |

| LEV | –1.189*** | –1.318*** | –1.188*** | –1.317*** | –1.197*** | –1.327*** | –1.155*** | –1.290*** |

| (–8.16) | (–8.21) | (–8.15) | (–8.20) | (–8.20) | (–8.26) | (–7.82) | (–7.94) | |

| GROWTH | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.013 | –0.022 | –0.012 |

| (0.39) | (0.83) | (0.35) | (0.80) | (0.29) | (0.74) | (–1.09) | (–0.53) | |

| MTB | 0.068*** | 0.082*** | 0.068*** | 0.083*** | 0.068*** | 0.083*** | 0.046*** | 0.057*** |

| (4.98) | (5.58) | (5.02) | (5.61) | (5.04) | (5.63) | (3.08) | (3.52) | |

| varROA | –0.335 | –0.211 | –0.336 | –0.212 | –0.350 | –0.227 | 0.015 | 0.167 |

| (–1.06) | (–0.61) | (–1.06) | (–0.61) | (–1.12) | (–0.65) | (0.05) | (0.49) | |

| RND | 9.180*** | 9.940*** | 9.152*** | 9.914*** | 9.207*** | 9.971*** | 8.439*** | 9.240*** |

| (6.08) | (6.18) | (6.07) | (6.17) | (6.12) | (6.22) | (5.31) | (5.45) | |

| SOE | –0.598*** | –0.665*** | –0.597*** | –0.665*** | –0.595*** | –0.662*** | –0.560*** | –0.627*** |

| (–5.82) | (–5.84) | (–5.82) | (–5.83) | (–5.80) | (–5.82) | (–5.34) | (–5.41) | |

| CEOTENURE | –0.002 | 0.002 | –0.002 | 0.003 | –0.001 | 0.003 | –0.001 | 0.003 |

| (–0.42) | (0.57) | (–0.39) | (0.59) | (–0.35) | (0.64) | (–0.19) | (0.60) | |

| DUAL | 0.088* | 0.106** | 0.087* | 0.105** | 0.085* | 0.103** | 0.078 | 0.095* |

| (1.90) | (2.10) | (1.89) | (2.09) | (1.84) | (2.04) | (1.47) | (1.65) | |

| BOARD | 0.541*** | 0.405*** | 0.541*** | 0.405*** | 0.543*** | 0.407*** | 0.470*** | 0.309* |

| (3.91) | (2.62) | (3.91) | (2.62) | (3.93) | (2.64) | (3.11) | (1.83) | |

| INDE | 0.635* | 0.666* | 0.632* | 0.664* | 0.638* | 0.670* | 0.491 | 0.475 |

| (1.73) | (1.66) | (1.73) | (1.66) | (1.75) | (1.68) | (1.22) | (1.08) | |

| INSSHR | –0.687*** | –0.797*** | –0.689*** | –0.800*** | –0.702*** | –0.814*** | –0.834*** | –0.972*** |

| (–4.30) | (–4.55) | (–4.31) | (–4.56) | (–4.40) | (–4.65) | (–4.59) | (–4.87) | |

| BIG4 | –0.096 | –0.084 | –0.094 | –0.082 | –0.092 | –0.080 | –0.028 | –0.008 |

| (–1.29) | (–1.01) | (–1.27) | (–1.00) | (–1.24) | (–0.97) | (–0.34) | (–0.08) | |

| _cons | –0.294 | –0.825 | –0.350 | –0.879 | –0.463 | –0.998 | –0.173 | –0.600 |

| (–0.32) | (–0.80) | (–0.38) | (–0.85) | (–0.50) | (–0.97) | (–0.18) | (–0.55) | |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 |

| adj. R2 | 0.297 | 0.271 | 0.297 | 0.271 | 0.298 | 0.272 | 0.308 | 0.281 |

| Panel B: The Oster (2019) method | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Assumption of Model (1) | |||

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | ||

| 1.3 R2; δ = 1 | Estimated β from Model (1) = 0 | 1.3 R2; δ = 1 | Estimated β from Model (1) = 0 |

| (1) ‘True’ α1 Bound | (2)δ | (3)‘True’ α1 Bound | (4)δ |

| [-0.871, –0.831] | 221.25 | [–0.857, –0.849] | 24.61 |

| Panel C: The test of parallel trend assumption | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TPAY1 | (2) TPAY2 | |||

| Coefficient | T-Value | Coefficient | T-Value | |

| TREAT×PRE_2 × ROA | 0.407 | (0.90) | 0.463 | (0.96) |

| TREAT×PRE_1 × ROA | –0.071 | (–0.15) | –0.131 | (–0.26) |

| TREAT×CURRENT×ROA | 0.611 | (1.25) | 0.659 | (1.26) |

| TREAT×POST_1 × ROA | –0.402 | (–0.89) | –0.267 | (–0.55) |

| TREAT×POST_2 × ROA | 0.099 | (0.17) | 0.181 | (0.29) |

| TREAT×POST_3 × ROA | –1.338** | (–2.49) | –1.304** | (–2.16) |

| TREAT×POST_4 × ROA | –1.134*** | (–2.96) | –1.210*** | (–2.89) |

| TREAT×PRE_2 | –0.159** | (–2.39) | –0.161** | (–2.28) |

| TREAT×PRE_1 | –0.133* | (–1.67) | –0.138 | (–1.62) |

| TREAT×CURRENT | –0.256*** | (–2.75) | –0.256** | (–2.57) |

| TREAT×POST_1 | –0.179* | (–1.88) | –0.189* | (–1.86) |

| TREAT×POST_2 | –0.290*** | (–2.74) | –0.297*** | (–2.62) |

| TREAT×POST_3 | –0.247** | (–2.36) | –0.265** | (–2.34) |

| TREAT×POST_4 | –0.144 | (–1.38) | –0.137 | (–1.22) |

| ROA | –1.751 | (–0.41) | –3.045 | (–0.66) |

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | ||

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| N | 26,031 | 26,031 | ||

| adj. R2 | 0.309 | 0.282 | ||

- Note: Table 3 reports the baseline results, tests for omission factors, and verifies the assumption of a parallel trend. In Panel A, columns (1) and (2) report the influence of ROA on executives’ compensation, columns (3) and (4) report the influence of the ASMM on executives’ compensation, columns (5) and (6) report the influence of the ASMM on executives’ pay-performance sensitivity excluding the effect of the interaction term between ROA and the control variables, and columns (7) and (8) report the influence of the ASMM on executives’ pay-performance sensitivity using Model (1), respectively. Panel B reports tests for the impact of omitted variables in Model (1). Panel C shows the verification of the assumption of a parallel trend. All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. Year and firm fixed effects are included in the model. The standard errors of all regression models are clustered at the firm level. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Columns (5)–(8) of Table 3 Panel A show the results of the tests of H1a and H1b. In columns (5) and (6), excluding the effect of the interaction term between ROA and the control variables, the coefficients of ROA are 1.733 and 1.785 and significant at the 1% level. This indicates that the accounting earnings of firms without the ASMM are significantly and positively related to executive compensation. The coefficients of TREAT×POST×ROA are –0.936 and –0.984, respectively, and significant at the 1% level. Further, the results of Model (1) are presented in columns (7) and (8). Regardless of whether TPAY1 or TPAY2 is the dependent variable, the coefficient of ROA is positive but insignificant,11 and the coefficients of TREAT×POST×ROA are –0.831 and –0.849, respectively, at the 1% level. Consequently, the sensitivity of executive compensation to accounting earnings significantly decreases after establishing the ASMM, and thus H1b is supported.

Omitted Variable Issue

Referring to Donohoe et al. (2022), we use Oster's (2019) approach to explore the impact of omitted factors in Model (1). The examination is divided into two parts: whether there are any omitted variables equivalent in importance to the observed variables in Model (1) that have an impact on the regression results, and how many times the impact of the unobserved factors needs to be greater than that of the observed variable to overturn the findings in the baseline results. First, it assumes that the R2 of the main test becomes 1.3 times its original value after introducing an omitted factor of equal importance (δ = 1) to the observed factor (TREAT×POST×ROA), whereby the interval of the true α1 of the main test is restored. Suppose the interval of the restored true α1 is within the 99.5% confidence interval of the coefficient of TREAT×POST×ROA in Model (1) and does not contain the value of zero. In that case, the coefficient of TREAT×POST×ROA in Model (1) is considered stable. It is unlikely that there are unobserved factors as important as the observed variables.

Second, assuming that the coefficient of TREAT×POST×ROA in Model (1) becomes zero or significantly positive after the inclusion of the omitted factor, the importance (δ) of the omitted factor relative to the observed factor (TREAT×POST×ROA) is calculated. Oster (2019) argues that when the absolute value of δ exceeds one, it is unlikely that there are unobserved factors that significantly affect the main test. The omitted variable tests for Model (1) are presented in Panel B. In columns (1) and (3), regardless of whether TPAY1 or TPAY2 are taken as the dependent variable, the interval of true α1 does not contain zero and is within the 99.5% confidence interval of the coefficient of TREAT×POST×ROA in Model (1). The absolute value of δ is 221.25 and 24.61, respectively, much greater than 1. Given the evidence above, we believe that omitted variables are unlikely to be a concern in our model.

Parallel Trend Assumption Test

The DiD model can only be valid when the assumption of parallel trends is satisfied. If the trends of the dependent variables were systematically different between the treatment and control groups, our conclusions would be challenged by incorrect research design. Therefore, we construct the dummy variables PRE_t (t = 1, 2, 3), CURRENT, and POST_t (t = 1, 2, 3, 4) to identify the changes in executive compensation in each year before and after the point of establishment of the system to test the parallel trend assumption.

The variable PRE_t (t = 1, 2, 3) is equal to one if the firm-year is in the third year and before, the second year, and the first year before the treatment group established the ASMM, and zero otherwise. In contrast, CURRENT and POST_t (t = 1, 2, 3, 4) are equal to one when the firm-year is in the current year, the first year, the second year, the third year, the fourth, and the subsequent years when the treatment group establishes the ASMM, and zero otherwise. Using PRE_3 as the benchmark and replacing POST in Model (1) with PRE_t (t = 1, 2), CURRENT, and POST_t (t = 1, 2, 3, 4), we construct a Model (2). The control variables are the same as in Model (1).

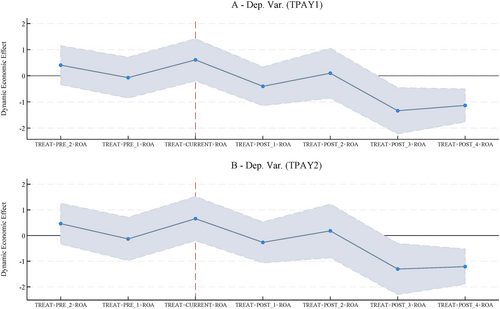

The regression results are presented in Table 3, Panel C, and Figure 2, respectively. The coefficients of TREAT×PRE_t × ROA are not significant, indicating no significant difference in the pay-performance sensitivity of executives between the treatment and the control groups before establishing the ASMM. Although the coefficients of TREAT×CURRENT×ROA, TREAT×POST_1 × ROA, and TREAT×POST_2 × ROA are not significant, the coefficients of TREAT×POST_3 × ROA and TREAT×POST_4 × ROA are significantly negative. This indicates that executive pay-performance sensitivity declines significantly after three years since the establishment of the ASMM.

Note: Figure 2 shows the results of whether the assumption of parallel trends is met for Model (1). Panel A and Panel B correspond to Model (2), with TPAY1 and TPAY2 as dependent variables, respectively. The horizontal coordinates are the time points for each year before and after the implementation of the ASMM, and the vertical coordinates correspond to the values of the solid dots in blue, which measure the coefficients of the time-based dummy variables in Model (2). The shadowed areas identify the level of significance of the coefficients on the time-based dummy variables at each time point. If the shadowed area at a given point does not contain the horizontal line of zero, the coefficient on the dummy variable is significant at the 10% level or above.

MECHANISM TEST

| Panel A: Tests for the sensitivity of executives’ compensation to accrual earnings and impact of ASMM on it | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | |

| DA×TREAT×POST | –0.426** | –0.346 | ||

| (–2.20) | (–1.65) | |||

| TREAT×POST | –0.113** | –0.106* | ||

| (–2.14) | (–1.88) | |||

| DA | 0.239** | 0.229* | 1.256 | 1.640 |

| (2.18) | (1.92) | (0.51) | (0.61) | |

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 25,914 | 25,914 | 25,914 | 2,5914 |

| adj. R2 | 0.298 | 0.272 | 0.302 | 0.275 |

| Panel B: Mechanism Test of Accrual Earnings Management | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | ||||

| (1)DA | (2)DA | (3)DA | (4)DA | (5)DA | |

| Increase | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | ||

| TREAT×POST | –0.008** | ||||

| (–2.22) | |||||

| POST×ROA | –0.739 | –1.956*** | –0.801 | –2.026*** | |

| (–1.49) | (–3.61) | (–1.50) | (–3.51) | ||

| POST | –0.166 | –0.152 | –0.163 | –0.125 | |

| (–1.64) | (–1.26) | (–1.52) | (–0.95) | ||

| ROA | 0.483*** | –5.988 | –1.864 | –8.336 | –1.576 |

| (28.07) | (–0.70) | (–0.25) | (–0.93) | (–0.19) | |

| Difference in coefficients of POST×ROA | p value = 0.028 | p value = 0.030 | |||

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 24,167 | 7,887 | 10,233 | 7,887 | 10,233 |

| adj. R2 | 0.170 | 0.378 | 0.278 | 0.340 | 0.257 |

| Panel C: Mechanism test of risk taking | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | ||||

| (1)RISK | (2)RISK | (3)RISK | (4)RISK | (5)RISK | |

| Increase | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | ||

| TREAT×POST | –0.001* | ||||

| (–1.82) | |||||

| POST×ROA | –0.093 | –1.644*** | 0.014 | –1.659*** | |

| (–0.09) | (–4.42) | (0.01) | (–4.13) | ||

| POST | –0.378** | –0.126 | –0.367** | –0.134 | |

| (–2.28) | (–1.41) | (–2.10) | (–1.37) | ||

| ROA | 0.011*** | 12.139 | –9.459* | 14.327 | –11.030* |

| (3.48) | (0.94) | (–1.72) | (1.04) | (–1.83) | |

| Difference in coefficients of POST×ROA | p value = 0.016 | p value = 0.036 | |||

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 24,250 | 3,189 | 14,918 | 3,189 | 14,918 |

| adj. R2 | 0.288 | 0.288 | 0.336 | 0.275 | 0.303 |

- Note: Table 4 shows the mechanism test. Panel A reports the results of models (3) and (4). Panel B shows the mechanism test of earnings management. When using DA as the dependent variable, column (1) shows the regression result of Model (5) and columns (2)–(5) show the result of Model (6). Panel C shows the mechanism test of corporate risk taking. When using RISK as the dependent variable, column (1) shows the regression result of Model (5) and columns (2)–(5) show the result of Model (6). All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. Year and firm fixed effects are included in the model. The standard errors of all regression models are clustered at the firm level. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

We next construct Models (5) and (6) to test the potential paths by which the ASMM influences executives’ pay-performance sensitivity. We verify the mechanisms proposed above by testing the impact of the ASMM on earnings management and risk aversion and whether the changes in earnings management and risk aversion translate to a reduction in executive pay-performance sensitivity.

The results of Models (5) and (6) are presented in Panels B and C of Table 4. From column (1) of Panels B and C, we find that after the ASMM is established, firms’ accrual-based earning management and corporate risk taking decrease, indicating that firms’ establishment of the ASMM can inhibit executives’ opportunistic behaviour but induce executives’ risk aversion, validating our inference. Columns (2)–(5) of Panel B show that the reduction effect of the ASMM on the pay-performance sensitivity of executives is significantly higher in companies with decreased DA. According to columns (2)–(5) of Panel C, the reduction effect of the ASMM on the pay-performance sensitivity of executives is significantly higher for firms with reduced corporate risk taking. This confirms that the ASMM constrains executives’ earnings management, which relieves the high pay-performance sensitivity associated with high earnings management. However, the ASMM also exacerbates executives’ risk aversion, which makes the board reduce the sensitivity of executive compensation to earnings to encourage executives to take risks. These both validate the mechanism that we propose.

ROBUSTNESS TEST

Propensity Score Matching

Significant differences in firm characteristics may exist between the treatment and the control groups, which could affect the validity of the regression results. Using propensity score matching to screen the sample, this problem can be mitigated. Referring to the method of Kubick et al. (2020), we use the treatment group in the year prior to the establishment of the ASMM (1,307 observations) and all the control group firms (7,910 observations) as matched subjects. We use firm size (SIZE), leverage (LEV), return on assets (ROA), sales growth (GROWTH), market-to-book ratio (MTB), whether the firm is loss-making (LOSS), fixed asset ratio (TANGIBLES), R&D investment (RND), agency cost (MFEE), firm age (AGE), nature of property rights (SOE), board size (BOARD), the proportion of independent directors (INDE), institutional shareholdings (INSSHR), CEO tenure (CEOTENURE), and Big-4 accounting firms (BIG4) as matching indicators (Bao et al. 2018), with the threshold of 0.005 for a 1 to 1 match without putback in the same year. As a result, 431 firms in the control group and 431 firms in the treatment group are successfully matched, representing 3,803 and 5,536 observations, respectively. Based on the matched observations, we retest Model (1) with the matching sample. The results are presented in Table 5.

| Panel A: Differences between the treatment and control groups before versus after matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

| Control | Treatment | Diff. | Control | Treatment | Diff. | |

| Mean | Mean | T-Value | Mean | Mean | T-Value | |

| (N = 7,910) | (N = 1,307) | (N = 431) | (N = 431) | |||

| SIZE | 22.18 | 21.61 | 13.90*** | 21.96 | 21.88 | 0.92 |

| LEV | 0.430 | 0.495 | –10.46*** | 0.495 | 0.479 | 1.05 |

| GROWTH | 0.204 | 0.195 | 0.56 | 0.207 | 0.178 | 0.65 |

| MTB | 2.051 | 2.454 | –9.30*** | 2.242 | 2.244 | –0.02 |

| LOSS | 0.095 | 0.112 | –1.94* | 0.097 | 0.093 | 0.23 |

| TANGIBLES | 0.222 | 0.266 | –8.53*** | 0.249 | 0.257 | –0.65 |

| RND | 0.020 | 0.006 | 22.61*** | 0.008 | 0.008 | –0.26 |

| MFEE | 0.080 | 0.098 | –7.65*** | 0.093 | 0.092 | 0.10 |

| AGE | 1.866 | 2.132 | –10.12*** | 2.123 | 2.121 | 0.02 |

| SOE | 0.360 | 0.559 | –13.82*** | 0.573 | 0.552 | 0.62 |

| BOARD | 2.244 | 2.288 | –8.33*** | 2.299 | 2.286 | 1.09 |

| INDE | 0.375 | 0.366 | 5.91*** | 0.367 | 0.367 | –0.21 |

| INSSHR | 0.472 | 0.539 | –8.64*** | 0.555 | 0.547 | 0.49 |

| CEOTENURE | 3.851 | 3.281 | 6.90*** | 3.295 | 3.462 | –1.02 |

| BIG4 | 0.094 | 0.050 | 5.17*** | 0.100 | 0.081 | 0.95 |

| Panel B: PSM + DID | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | |

| TREAT×POST×ROA | –1.012** | –0.992** |

| (–2.23) | (–2.02) | |

| TREAT×POST | –0.050 | –0.044 |

| (–0.63) | (–0.51) | |

| ROA | 1.767 | 0.706 |

| (0.30) | (0.11) | |

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9,339 | 9,339 |

| adj. R2 | 0.326 | 0.298 |

- Note: Table 5 shows the propensity score matching of Model (1). Panel A shows the differences in firm characteristics between the treatment and control groups before and after matching. Panel B shows the regression results using samples with the propensity score match. All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. Year and firm fixed effects are included in the model. The standard errors of all regression models are clustered at the firm level. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Panel A reports the results of the test. Columns (1)–(3) show the differences in the matching indicators between the treatment and the control groups before matching, with a sample of the treatment group in the year prior to the establishing year and the entire control group. Columns (4)–(6) show the differences in firm characteristics between the groups after matching. According to columns (3) and (6), most of the firm characteristic indicators are significantly different before matching, whereas the difference disappears after matching, which indicates that our matching is effective. Panel B shows the regression result of Model (1) using the matching sample. The coefficients of TREAT×POST×ROA are all significantly negative, which means that the results of the baseline test hold.

Placebo Test

Although the ASMM established by Chinese listed companies demonstrates staggered establishment characteristics, which greatly alleviates our concerns about omitted factors contributing to the findings, we use a placebo test to investigate this issue further. Placebo tests are conducted by randomly generating treatment groups.

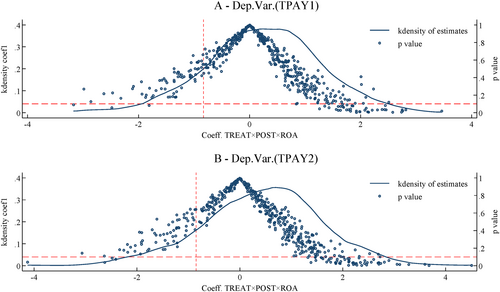

Referring to Zhang et al. (2022), we use the treatment group sample for the year prior to the establishment of the system and all the control group samples to construct the placebo test of a randomly selected treatment group. We randomly select 1,500 firms as the pseudo-treatment group and the remaining firms as the pseudo-control group. Based on the pseudo-treatment and pseudo-control groups, we generate the pseudo-dummy variable TREAT×POST and the key variable TREAT×POST×ROA. After repeating the random sampling 500 times, we plot the distribution of the estimated coefficients and p-values of pseudo-TREAT×POST×ROA from the 500 regressions, and the results are presented in Figure 3. The coefficients of pseudo-TREAT×POST×ROA are mainly distributed around zero, and the p-values are also mostly above the 10% significance level, implying that our conclusions are relatively unlikely to be driven by other policies or unobserved factors.

Note: Figure 3 shows the placebo test using the placebo-treatment group. Panel A and B present the placebo test results, with TPAY1 and TPAY2 as the dependent variables, respectively. The horizontal coordinates are the regression coefficients for the pseudo-TREAT×POST×ROA, and the vertical coordinates are the p-values of the regression coefficients. The horizontal dashed line indicates the significance level of 10%, and the vertical dashed line refers to the regression coefficient of TREAT×POST×ROA in Model (1). If the coefficients and p-values for pseudo-TREAT×POST×ROA are distributed around the vertical and horizontal dashed lines, it implies that the placebo test failed and the presence of unobserved factors leading to the regression results is more probable.

Heckman Test

We use the two-stage Heckman treatment effects model to mitigate the self-selection problem in establishing the ASMM. We construct the selection model for the ASMM in the first stage, as shown in Model (7), using the establishment ratio of the ASMM in each industry among years (IV) as the instrumental variable, and the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) is calculated accordingly. The control variables are the same as in Model (1), with industry and year-fixed effects. After adding the IMR to Model (1), we construct Model (8), and the results are presented in Table 6. Column (1) shows that the coefficient of IV is significantly positive, indicating that IV is positively correlated with TREAT. After adding the IMR into Model (1), the results in columns (2) and (3) show that the results of the main test hold.

| The First Stage | The Second Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| prob. (TREAT) | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | |

| TREAT×POST×ROA | –0.845*** | –0.862*** | |

| (–2.93) | (–2.75) | ||

| TREAT×POST | –0.077 | –0.070 | |

| (–1.37) | (–1.16) | ||

| ROA | –0.910*** | –0.476 | –1.536 |

| (–6.36) | (–0.11) | (–0.33) | |

| IV | 2.497*** | ||

| (15.38) | |||

| IMR | –0.230 | –0.215 | |

| (–1.54) | (–1.31) | ||

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IND FE | Yes | No | No |

| FIRM FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 |

| pseudo/adj. R2 | 0.138 | 0.308 | 0.281 |

- Note: Table 6 shows the Heckman test of Model (1). Column (1) reports the regression results from the first-stage regression for the exogenous variable. Columns (2) and (3) show the second-stage regression. All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. Year and firm fixed effects are included in the model. The standard errors of all regression models are clustered at the firm level. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Concerns about the Nature of Property Rights

After we add SOE and its interaction terms with TREAT×POST×ROA, TREAT×POST and ROA to Model (1), Model (9) is constructed to identify the moderating effect of the nature of property rights on the relationship between ASMM and executive pay-performance sensitivity. The results are presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7. The coefficients of SOE×TREAT×POST×ROA are not significant, suggesting that the reduction effect of the ASMM on the performance sensitivity of executive compensation is common in state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | TPAY1 | TPAY2 | |

| SOE×TREAT×POST×ROA | –0.099 | –0.140 | ||||||

| (–0.18) | (–0.24) | |||||||

| SOE×TREAT×POST | –0.195** | –0.297*** | ||||||

| (–2.46) | (–3.43) | |||||||

| SOE×ROA | –0.642 | –0.660 | –0.196 | –0.160 | –0.775** | –0.794** | –0.379 | –0.319 |

| (–1.32) | (–1.26) | (–0.50) | (–0.37) | (–2.10) | (–1.98) | (–0.92) | (–0.70) | |

| SOE | –0.433*** | –0.434*** | –0.506*** | –0.536*** | –0.546*** | –0.611*** | –0.383*** | –0.443*** |

| (–3.83) | (–3.49) | (–4.48) | (–4.30) | (–5.23) | (–5.30) | (–3.68) | (–3.85) | |

| CLAWBACK×TREAT×POST×ROA | 0.184 | 0.092 | ||||||

| (0.26) | (0.12) | |||||||

| CLAWBACK×TREAT×POST | –0.017 | –0.029 | ||||||

| (–0.19) | (–0.31) | |||||||

| CLAWBACK×ROA | –1.539** | –1.748*** | ||||||

| (–2.41) | (–2.61) | |||||||

| CLAWBACK | –0.084 | –0.147 | ||||||

| (–0.83) | (–1.35) | |||||||

| ANTI_CORR×TREAT×POST×ROA | 0.100 | –0.010 | ||||||

| (0.17) | (–0.02) | |||||||

| ANTI_CORR×TREAT×POST | 0.093 | 0.112 | ||||||

| (1.12) | (1.24) | |||||||

| ANTI_CORR×ROA | –1.458*** | –1.553*** | ||||||

| (–2.89) | (–2.87) | |||||||

| ANTI_CORR | –0.016 | –0.020 | ||||||

| (–0.20) | (–0.23) | |||||||

| TREAT×POST×ROA | –0.816* | –0.829* | –0.696** | –0.669** | –0.443 | –0.351 | –1.520*** | –1.566*** |

| (–1.88) | (–1.75) | (–2.25) | (–1.99) | (–1.23) | (–0.90) | (–4.19) | (–3.93) | |

| TREAT×POST | 0.048 | 0.112 | –0.080 | –0.075 | –0.148*** | –0.156** | 0.094 | 0.110 |

| (0.59) | (1.28) | (–1.38) | (–1.20) | (–2.61) | (–2.57) | (1.27) | (1.37) | |

| ROA | 0.159 | –0.733 | –1.316 | –2.464 | –3.160 | –4.560 | –0.553 | –0.881 |

| (0.04) | (–0.16) | (–0.30) | (–0.53) | (–0.74) | (–0.99) | (–0.10) | (–0.15) | |

| CONTROLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FIRM FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YEAR FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 26,031 | 12,499 | 12,499 |

| adj. R2 | 0.309 | 0.283 | 0.310 | 0.284 | 0.309 | 0.282 | 0.256 | 0.239 |

- Note: Table 7 shows the tests for the heterogeneity impact of the nature of property rights, the influence of the state-owned enterprises’ clawback system, anti-corruption, and listed companies’ SEO events. All variables are defined in Table A1 in the Appendix. Year and firm fixed effects are included in the model. The standard errors of all regression models are clustered at the firm level. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Concerns about Other Confounding Events

Given the extensive time span covered by our sample, it is possible that significant events occurring during the period could have influenced the findings presented. Although we have employed placebo tests to address this concern, we acknowledge the need to explore notable events that may potentially impact the conclusions.