Financial Resilience Perspective on COVID-19 Business Support: A Comparative Study of Four European Countries

The authors are indebted to the reviewer of the EIASM 2022 public sector conference, as well as the reviewers of the Durham 2022 symposium on accountability in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, for their comments and suggestions. They also merit the valuable comments and suggestions of the Abacus special issue editors and reviewers.

Abstract

This paper investigates COVID-19 business support in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Simple and generally applicable programs for wage and fixed-cost support are predominant. From a financial resilience perspective, support programs can be seen as coping responses to the crisis through attempts at bouncing back to the situation before the virus outbreak. This also holds for the dynamics of the support during the pandemic, where governments balanced the desire to return to normal economic circumstances that called for stricter access conditions, and the need to provide support for a longer-lasting pandemic that required the opposite. Bouncing-forward responses, such as setting up new post-shock configurations, were largely absent, which is likely to be due to the need for quick and adequate responses that gave limited time for critical reflection. The impacts of business support on the number of bankruptcies and employment figures were positive. Unemployment and fiscal impacts diverged among the four countries, and it is suggested that governmental structure was influential: unitary states performed better than federal states. The paper also reflects on the lessons learned from COVID-19 for support in future crises, like the recent energy crisis, and points to an increasing attention to information-sharing within the government system, but also notes limited progress in critical thinking.

At the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 virus outbreak gave rise to constraints that had substantial consequences for the survival of many businesses. This is because they lost a lot of their income, while most of their costs continued or could not be reduced proportionally to their income loss. Hence, many governments instigated programs for financial support of these organizations, in order to avoid unemployment and bankruptcy.

Although COVID-19-related business support has been widely applied around the world, in-depth analyses of this support are scarce. This is apparent from special issues on COVID-19 in accounting journals (e.g., Grossi et al., 2020; Leoni et al., 2021), as well as public administration journals (e.g., Kuhlmann et al., 2021). Only one paper in these special issues discusses governmental business support due to the pandemic (Andrew et al., 2021), but its focus is limited. Two international comparative studies about COVID-19 business support are, however, worth mentioning. An IMF report (Ebeke et al., 2021) shows that support measures were effective in reducing liquidity risks and saving jobs, whereas their impact on solvency risks was limited. Demou et al. (2021) add that in OECD countries, wage support, in particular, was effective.

Our study aims to make a distinctive contribution by providing an in-depth analysis of COVID-19 business support in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal. In taking a financial resilience perspective, we focus on governments’ coping and anticipatory responses to the pandemic, on lessons learned, as well as COVID-19's impacts on fiscal matters and employment. In addition, comparing countries with a federal or unitary governmental structure (respectively Belgium and Germany as opposed to the Netherlands and Portugal) allows us to investigate whether the specific administrative structure matters. Our investigations are based on a qualitative approach and rely on government documents, reports of institutions for applied research, official statistics, and interviews with key actors.

FINANCIAL RESILIENCE AS A THEORETICAL STANCE

Positioning Our Study in the Resilience Literature

Resilience is not a new concept. In his seminal paper about new public management (NPM), Hood (1991) points to a set of public sector values related to resilience, endurance, robustness, survival, and adaptivity, which allow operations to continue, even in adverse ‘worst cases’, and to adapt rapidly in a crisis (Hood, 1991, pp. 13–14). Resilience as a concept has been adopted in many different fields, such as ecological systems and physical systems. More recently, the concept received much attention in the fields of disaster management (Boin and van Eeten, 2013), organizational science, and supply chain management (see Bahmra et al., 2011).

Initially, resilience was restricted to the capacity to withstand an external shock or crisis, to react and absorb its impact in order to restore the situation (or return to the trend) before the shock, labelled as ‘bouncing back’ (Bhamra et al., 2011; Boin and Van Eeten, 2013). Later on, the concept was extended to also consider the so called ‘bouncing-forward’ capacity, which refers to setting up new post-shock configurations, called ‘transformational resilience’ (Shen et al., 2023), as well as anticipation of and quick adaptation to new challenges before they happen, called ‘evolutionary resilience’ (Saliterer et al., 2021).

Most relevant for our study are the insights derived from the financial resilience literature. Since the financial crisis of 2008 and the resulting austerity programs, the impact of shocks on public finance has been intensively studied by public policy and public sector accounting scholars. Various empirical studies have investigated financial resilience. They include: Barbera et al. (2017) in Austria and Germany; Barbera et al. (2017, 2021) in Italy; Wójtowicz and Hodži (2022) in Poland and Croatia; Padovani et al. (2021) in Portugal and Italy; Upadhaya et al. (2020) in India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka; Ahrens and Ferry (2020) in the UK; and Lee and Chen (2022) in the US.

Many studies that investigate the financial resilience of governments in a crisis context examine the relationship between hindering or stimulating factors for becoming or staying resilient. Such factors include financial aspects (e.g., indebtedness), elements of human resources (e.g., personnel capacities), and political circumstances (e.g., political stability). Financial resilience can be measured as the time for recovering from a financial setback due to a crisis, or by comparing pre- and post-crisis financial criteria, such as debt over GDP (see, for instance, Barbera et al., 2017, 2021; Padovani et al., 2020; Upadhaya et al., 2020; Lee and Chen, 2022; Wójtowicz and Hodži, 2022). Of the formerly listed studies only Upadhaya et al. (2020), Ahrens and Ferry (2020), Wójtowicz and Hodži (2022), and Padovani et al. (2021) focus on financial resilience related to the COVID-19 crisis. Our study differs from this research in two ways. First, it is dedicated to measures that specifically cope with the financial impacts of a crisis, in particular COVID-19 business support. Second, it acknowledges that the COVID-19 crisis is characterized by extreme uncertainty and turbulence, which calls for an investigation of direct consequences, such as providing business support, but also indirect consequences in terms of learning for future crises. This also underpins the importance of investigating COVID-19 coping and anticipatory responses that have never been explicitly related to business support. The next section provides a theoretical lens for the analysis of the four country studies. These country studies, including a comparative analysis are presented in the subsequent section. The following section reflects on these findings in the light of the more recent business support during the energy crisis 2022-2023. The final section comprises conclusions and reflections.

A Framework for Financial Resilience

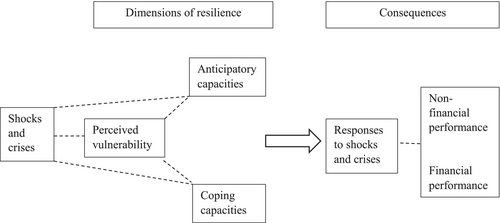

Our study builds on the theoretical framework for financial resilience as developed by Barbera et al. (2023), the core elements of which are depicted in Figure 1. A brief clarification of this framework is given below.

(Source: Barbera et al., 2023)

Vulnerability concerns the extent to which organizations can be negatively affected by shocks and crises. Anticipatory capacities aim to identify and control vulnerabilities, for example, through the monitoring of potential threats and through risk management. Coping capacities can lead to actions or responses to manage the crisis or shock, such as buffering (by absorbing the impact of a crisis); adaptation (i.e., incremental changes of structures and processes), and transformative capacities (which point to radical changes in structures and processes). These coping responses resonate with bouncing-back and bouncing-forward strategies, which can have non-financial impacts (e.g., on health and employment) and fiscal impacts (e.g., governmental finances in terms of deficits and debts).

Operationalization of the Financial Resilience Framework for our Study

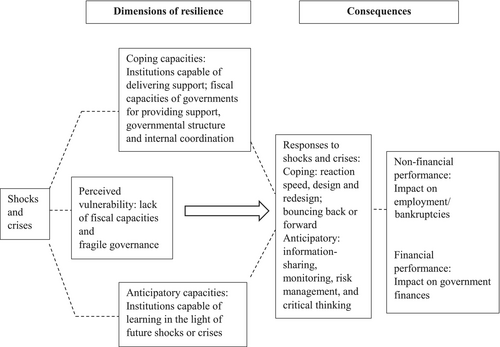

Because our study focuses on business support as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, we will elaborate on and expand the more general framework in Figure 1 for the business support context (see Figure 2 and further clarifications below).

(Source: inspired by Barbera et al., 2023, and elaborated on and expanded by the authors)

Perceived vulnerability is associated with a lack of capacity for adequately responding to a crisis or shock. Vulnerability can have various dimensions (see, for instance, Padovani et al., 2020), but we focus on two important ones. First, a lack of fiscal capacity, measured by government debt over GDP, can be an obstacle in providing business support during a crisis. Second, fragile governance can be a hindrance for effective business support, that is, support programs that insufficiently achieve relevant goals in financial and employment terms. Our study relies on indicator values for six governance dimensions, developed by the World Bank, which are published annually for more than 200 countries (see, for clarification, Kaufmann et al., 2010). The World Bank defines governance as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised. Three areas of governance are identified, and each include two indicators: 1) the processes of selecting, monitoring, and replacing government (with voice and accountability, as well as political stability and absence of violence/terrorism indicators); 2) the capacity for formulating and implementing policies (with government effectiveness and regulatory quality indicators); and 3) the respect of citizens and the state for governing institutions (with rule of law and control of corruption indicators). The underlying data are mainly based on surveys and input from experts.

In general, capacities refer to a specific ability, while responses refer to the way in which reactions are shaped. Of course, coping capacities and responses are related, as are anticipatory capacities and responses.

Coping capacities for crisis-related business support may include, on the one hand, financial facilities for taking adequate measures to tackle the crisis. However, De Jong and Ho (2021; see also Chen et al., 2021) find that serious indebtedness of OECD countries did not hinder generous COVID-19-related policies, but this relationship regards fiscal measures in general, while our focus is on financial support for businesses. On the other hand, coping capacities can also refer to institutional enablers for taking action, especially the availability of governmental organizations that have the capacity to execute business support programs, which mirrors governance issues as introduced under vulnerability. Coping responses related to business support comprise specific dimensions: reaction speed; design principles (in particular, generally applicable versus tailor-made programs); and reasoning behind adaptation of programs over the course of time (e.g., new types of programs, and revisions of access conditions to existing support programs).

Anticipatory capacities concern the abilities of institutions to learn from COVID-19 business support for future support programs. A distinction can be made between first-order and second-order anticipatory responses. First-order responses refer to how governments prepare themselves for similar crises in the future, especially through monitoring the features that may impact the design of business support. Second-order responses go beyond similar crises and concern crises with different causes, scopes, and consequences; for instance, what can be learned from business support during the COVID-19 pandemic for similar support during other types of crises, such as the energy crisis (or other shocks and crises like climate catastrophes, supply-chain disturbances, or banking crises). According to Barbera et al. (2023), various measures can be part of organizational learning, that is, information sharing (so, with other organizations facing similar challenges); and monitoring (of future events and circumstances), including risk management (see also Ahrens and Ferry, 2020; Bracci et al., 2022); as well as critical thinking about existing policy-making.

The effectiveness of business support can be measured through non-financial and financial measures. The main non-financial performance dimensions of business support are concerned with avoiding employment losses and bankruptcies. The financial dimensions of business support effectiveness regard the impact on government finances in terms of debt over GDP.

Clues for a Comparative Analysis

Responses of governments to a crisis might be dependent upon country-specific characteristics (see Kuhlmann and Wollmann, 2019). Specifically, we envisage that countries with a federal structure possibly attribute responsibilities about these programs to both the federal and sub-federal layer, which could lead to either divergent or complementary approaches at both layers, resulting in additional expenses, whereas countries with a centralized governmental structure potentially rely on a more coherent (and less costly) support program. Chen et al. (2021), in an international comparative study about the first half year of the COVID-19 pandemic, confirm the thesis of a relatively larger business support in federal countries. Fiscal capacities might also contribute to a large extent of business support, but, as argued before, this relationship is contested in research about crisis-related governmental interventions. In addition, our study can provide knowledge on how coordination mechanisms and information-sharing among various governmental layers and institutions can contribute to effective business support in times of crisis, which can be part of anticipatory capacities.

Research Questions

- To what extent were governments in the four countries vulnerable, in the sense of having a lack of capacity for adequately responding to the COVID-19 crisis?

- In terms of coping capacities and responses, how quickly did governments in the four countries react to the outbreak of the crisis by installing business support programs, how large was the business support, and how was it designed, especially in terms of the types of support, and the target groups of the support? Can the support be categorized as a bouncing-back or a bouncing-forward response?

- In terms of coping capacities and responses, how were business support programs in each of the countries adapted in the course of the crisis, over the years 2020–2021, in terms of expenditure as well as types and target groups, and for what reasons? Can the dynamics of the support be categorized as a bouncing-back or a bouncing-forward response?

- What were the fiscal and employment impacts of business support in each of the countries?

- In terms of coping capacities and responses, which circumstances can potentially explain similarities and differences among the four selected countries in the design and dynamics of business support, as well as their impacts, in which elements of governmental structure, government governance, and its fiscal capabilities might be considered?

- In terms of anticipatory capacities and responses, what did governments in the four countries learn from business support programs during the 2020–2021 COVID-19 pandemic for similar or different crisis-related programs in the future, through information sharing, monitoring, risk management, and critical thinking?

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

Table 1 presents a comparison of the findings about COVID-19 business support in the four countries. This section discusses these findings.

| Research questions | Issues for comparison | Belgium | Germany | The Netherlands | Portugal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping responses regarding the design of the support | Speed of the response: | Immediate after the virus outbreak | Immediate after the virus outbreak | Immediate after the virus outbreak | Immediate after the virus outbreak |

| Support 2020 + 2021 as a percentage of annual GDP (sum) | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 2.3 | |

| Types of support | Unemployment benefits; income loss support; credit guarantees; COVID-19 loans; default moratorium | Unemployment benefits; short-term working allowance; support for SMEs and self-employed; facilities for loans; reduction in VAT rates | Wage supplementation; fixed-cost supplementation, both due to income losses; loan facilities | Wage supplementation; support for SMEs and self-employed due to income losses; short-term work allowance; fixed-cost supplementation; tax deferrals | |

| Target groups of support | Generally applicable | Mostly generally applicable | Generally applicable | Generally applicable but also specific groups, e.g., tourism | |

| Bouncing back or forward | Bouncing back | Bouncing back | Bouncing back | Bouncing back | |

| Coping responses regarding the adaptation of the support | Change in support as percentage of GDP | From 3.4 (2020) to 1.9 (2021) | From 1.9 (2020) to 2.4 (2021) | From 2.3 (2020) to 1.8 (2021) | From 0.9 (2020) to 1.4 (2021) |

| Adaptations of the support design in the course of time | More specific (related to extent of compensation), and stricter (access conditions) | Access conditions to support became stricter; special support for hard-hit sectors | Conditions were relaxed and support became more generous over time | Enlargement of short-term work allowance; support became more generous | |

| Bouncing back or forward | Mainly bouncing back, indications for bouncing forward | Bouncing back | Bouncing back | Bouncing back | |

| Impacts of the support | Fiscal impacts (debt over GDP) | From 98% in 2019 to around 113% in 2021 | From 60% in 2019 to around 70% in 2021 | From 49% in 2019 to around 53% in 2021 | From 117% in 2019 to around 133% in 2021 |

| Employment and bankruptcy impacts | Number of bankruptcies decreased; unemployment increased | Number of bankruptcies remained low; unemployment rate rose but recovered soon | Number of bankruptcies decreased; support avoided rise in (low) unemployment rate; part of support was wasted | Unemployment initially increased but decreased at the end of 2020 | |

| Explanations for similarities and differences | Governmental structure, federal versus unitary | Tax measures at federal level and income loss support at regional level | Measures mainly at federal level, states involved in implementation | Exclusively measures at the central level | Exclusively measures at the central level |

| Governance (governance score between −2.5 and 2.5) | Good (1.3) | Good (1.5) | Good (1.6) | Moderate (1.0) | |

| Fiscal capabilities | High debt ratio and high level of support | Low debt ratio and high level of support | Low debt ratio and medium level of support | High debt rate and low level of support |

Perceived Vulnerability

The vulnerability of government in the four countries comprises two dimensions, that is, lack of fiscal capacity and fragile governance. Fiscal capacity is measured by government debt over GDP, particularly in the year just before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, that is, 2019. Belgium and Portugal had a relatively poor fiscal health, with a debt over GDP ratio of about 98% and 117% respectively, whereas this ratio was relatively good in Germany (around 60%) and the Netherlands (around 49%), which were close to or below the EU standard of 60%.

Governance in the four countries is measured by the World Bank worldwide governance indicators (see further Kaufmann et al., 2010). Based on the years 2015–2021, we calculated the average indicator values over the six governance dimensions as introduced in the theory section (see Table 2 and related clarifications). Values can range from –2.5 to 2.5; the higher the score, the better (source: wigidataset). This results in the following outcomes for our study: 1.3 for Belgium, 1.5 for Germany, 1.6 for the Netherlands, and 1.0 for Portugal. Consequently, all four countries score well on governance, although Portugal is somewhat lagging behind (as standard deviations are very low, average differences are significant). So, effective governance might be a bit more problematic in Portugal. It seems that the overall vulnerability was higher in Belgium and Portugal than in Germany and the Netherlands, where a stronger responsiveness could be expected.

We will explore the possible influence of these two vulnerability dimensions on expenditure for business support and impacts later in this section.

Speed, Extent, and Design of the Support

In all four countries business support measures were implemented immediately after the virus outbreak. However, over the period 2020–2021, business support as a percentage of GDP was much lower in Portugal (2.3%) than in the Netherlands (4.1%), Germany (4.3%), and Belgium (5.3%).

Some types of support were present in all four countries, especially wage supplementation and loan facilities. However, there were differences between the types of business support and target groups. Unemployment benefits were important in Belgium and Germany, short-term work allowances were applied in Germany and Portugal, and fixed-cost support was established in the Netherlands and Portugal. Business support was predominantly arranged to be generally applicable to all firms suffering from COVID-19 restrictions. The extent of income loss, in case of wage or fixed-cost supplementation, or liquidity problems due to a lack of income from sales, in case of loan facilities, were conditions for receiving financial support. Portugal also instigated specific support, that is, for the tourism and commerce sectors in particular.

The preference for generally applicable support arrangements was impacted by the need to give rapid support, which required simple and easily manageable support criteria. In a similar vein, in several countries already existing arrangements were revitalized. Germany activated automatic stabilizers (unemployment insurance) and short-time working benefits. The latter enable companies to reduce their activities while employees remain employed in their respective company but receive income compensation in the form of government funds. The instrument existed previously but due to the pandemic, an adequate application process and various other factors (such as the extension of the reference period in favour of the beneficiary), were reasons for its activation. In Belgium the legalistic framework of the measure called ‘hindrance allowance’, previously dedicated to sales losses due to road works, was reused during the COVID-19 crisis as a lump sum cash allowance for all firms suffering as a result of the pandemic.

In Belgium both federal and regional governments were engaged in specific sector support, but tax measures were restricted to the federal government. The federal state installed a temporary moratorium on company bankruptcies and granted a state guarantee for new credits for non-financial corporations, including the self-employed, and the non-profit sector. The regions were in the lead regarding the allowances (e.g., Flemish Protection Mechanism (FPM)) to compensate for lost business income, but they also funded COVID-19 loans through their public investment vehicles.

In Germany, the 16 states (Länder) were involved in the implementation of the response packages to ensure a rapid outflow of funds, supplementing the federal aid only in some cases, for example, if certain sectors in the Länder were particularly affected (e.g., tourism). The program design and the provision of funds have nevertheless been carried out mainly by the federal government. An exception is ‘aid for hardship cases’ financed equally by the federal and state governments.

In the Netherlands as a decentralized unitary state, COVID-19 business support was only provided by the central government. Two business support measures were by far the largest: wage supplementation due to income loss for businesses and non-profit agencies (NOW) and fixed costs supplementation (TVL/TOGS; details are in van Helden et al., 2022). The latter type of support started later (in the Summer of 2020) than the former (March 2020).

Portugal is a centralized and unitary country with a market dominated by SMEs that were most affected by the COVID-19 shocks (Ebeke et al., 2021). It approved the first support measures (simplified lay-off) quickly and in a relatively simple way (Gomes, 2021) to mitigate, contain, and manage the spread of COVID-19. The support for income losses and fixed costs increased at a later stage (APOIAR program). The target sectors of these support measures were tourism, manufacturing industries, trade (non-food), automotive, and transport equipment. Companies with up to 10 workers represented around 80% of the businesses supported in 2020.

In all four countries, the business support packages were aimed to avoid bankruptcy and employment losses in all industries, in order to restore the situation before the pandemic outbreak. We therefore consider these support measures to be a bouncing-back response. Governments were not prepared for providing business support on short notice after the virus outbreak. So, they were forced to develop and implement simple support arrangements, and did not appear to have the time to consider types of support that would create new post-shock configurations, called bouncing-forward responses.

Dynamics in the Extent and Design of the Support

After the initial and quick implementation of the support in all four countries, large differences in the dynamics of the extent and design of the support among the countries are observed. While in Germany and Portugal support increased by 0.5% of GDP from 2020 to 2021, the opposite was true for the Netherlands (decrease of 0.5%) and Belgium (decrease of 1.5%).

In the Netherlands and Portugal access conditions for support were relaxed and support became more generous, thereby responding to the increasingly longer duration of the pandemic and its consequences for survival of specific categories of firms.

In the Netherlands, wage support was implemented as a simple measure in order to provide rapid support. However, this simplicity came at the expense of leaving little room for customization. Whereas the percentage of wage costs compensated originally was expected to diminish over time, it largely remained unchanged over the period. Fixed-cost support was initially meant to be temporary for a period of three months, but eventually it was continued until the third quarter of 2022. The first tranche was targeted at SMEs in branches that were hit most by the pandemic, but in the second tranche this group was extended to all SMEs and from the third quarter of 2020 onwards, all business entities were included. Despite the more generous access conditions for wage supplementation applications in 2021 in comparison to 2020, total support diminished over these years due to a substantial lower number of applications as a consequence of less severe COVID-19 constraints.

In Portugal, programs that were initiated at the beginning of the pandemic were extended and expanded. The short-term work scheme approved until the end of August 2020 was adjusted and enlarged in line with the evolution of the pandemic. Government decided to extend the first support measures allowing the companies affected by the new economic restrictions to keep or join the ‘simplified lay-off’ or the ‘support for progressive recovery’ until December 2020. The support for progressive recovery was revised from October to December 2020. In addition, in the last trimester of 2020, a financial incentive scheme was installed for covering additional fixed costs and tax deferral. This package was adjusted over time and aligned with the evolution of the pandemic and the worsening of the pandemic situation in January 2021. Support decisions to companies are dependent on analyses and validations by certified accountants and tax advisors.

At the onset of the crisis, the Belgian government responded quickly by installing generic, simple, lump sum types of support that could be accessed by all sectors (Dhyne and Duprez, 2021). Yet, over time, measures became less generous and more sector-specific, conditional, and restricted to healthy and tax-compliant businesses (e.g., Flemish Protection Mechanism).

In Germany, initially, leakages were accepted for offering quick and lump-sum aid. Due to the need to act quickly, few clear guidelines were formulated, which led to extensive use of some programs. The later programs were increasingly tailored to individual sectors and formulated stricter access conditions, and companies had to provide more evidence to receive support. In the course of the pandemic, several extensions were gradually provided until 2022, when special regulations were created for particularly hard-hit sectors, such as the travel, culture, and event industry, and also for start-ups. In contrast to ‘immediate aid’, later aid could only be provided with the help of a tax advisor, lawyer, auditor, or certified public accountant.

As we found that most adaptations were not designed to set up new post-shock configurations, we consider these to be bouncing-back responses. However, by restricting the support to healthy and tax-compliant businesses, Belgium also shows some indications of a bouncing-forward approach. It may come as a surprise that governments in the four countries did not consider more specific types of business support that would respond to the post-pandemic weaknesses of particular sectors, such as a lack of IT integration or a poor competitive profile. Although time pressures became less prominent in the course of the pandemic and bouncing-forward responses would become more likely, the simplicity of bouncing-back responses was seemingly preferred.

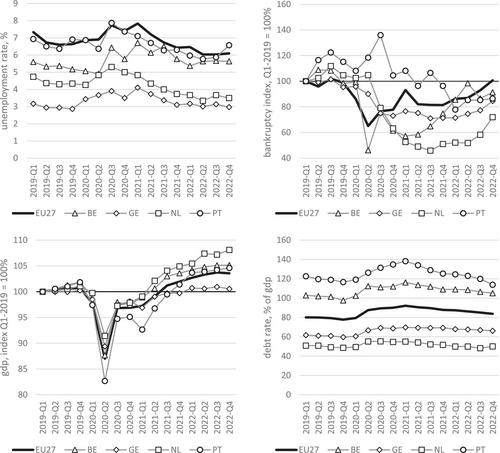

Understanding the Impacts of the Support

Figure 3 shows the impacts of the support. It indicates that the fiscal impact differed considerably among the four countries. Whereas debt over GDP was already high before the start of the pandemic in Belgium (101%) and Portugal (120%), these percentages increased further to 113% and 133%, respectively, at the end of 2021. In the other two countries, these percentages also rose, but from a lower base and to a lesser extent: in Germany from 60% to 70% and in the Netherlands from 49% to 53%, in 2019 and 2021 respectively.

(Source: authors' own depiction, own calculation, data: Eurostat)

In addition, Figure 3 shows the number of bankruptcies and the unemployment rate before and during the COVID-19 period, as crucial non-financial indicators of the business support. In general, the number of bankruptcies remained low during the pandemic, and after a rise in unemployment, a quick recovery in employment figures was noticeable.

In Belgium, firms seemed to have coped relatively well thanks to government support (NBB, 2022). Compared to pre-crisis years, the percentage of firms that ran losses and the percentage of overleveraged firms decreased. The number of bankruptcies was lower than before the pandemic. Zegel et al. (2021) evaluated the impact of the Flemish support measures from the start of the pandemic up to the third round of the Flemish Protection Mechanism. More than 50% of the support was directed towards sectors that were hit the most (SMEs in retail and catering). The Flemish regional product was estimated to have decreased by at least 8.5% in the absence of the support measures. Graydon's (2021) analysis for 2020 reveals that without the support measures, the Flemish pre-COVID-19 extremely healthy SMEs that were not crisis resistant would have increased by 16%. The percentage of Flemish zombie firms (heavily indebted firms that face the risk of going bankrupt) was estimated at 2.4% of Flemish SMEs.

In Germany, the impact of the support packages was generally considered to have been positive. Severe negative effects on the labour market were prevented and unemployment already reached its pre-crisis level in late 2021. Numbers of bankruptcies were lower than before the crisis and did not increase noticeably even after the expiration of the special regulations for corporate insolvencies in summer 2021. From the companies’ point of view, non-repayable aid measures and relaxations in profit taxation were rated as very helpful for companies while loans or guarantees were seen as less beneficial (DIHKT, 2020). Short-time work, bridging aid, and the economic stabilization fund were also generally seen as positive.

Although unemployment increased at the beginning of the COVID-19 period, later on it decreased to a lower level than before the outbreak in the Netherlands. Furthermore, the number of bankruptcies in 2021 was about half the amount in 2019. The measures helped to avoid bankruptcies and allowed employees to keep their jobs. In the absence of business support, the unemployment rate would have been between 0.7 and 2.0 percentage points higher. So, extensive support in 2020 has limited the economic damage (CPB, 2021). However, a substantial part of the support was given to firms with either a lack of economic potential, or firms with enough equity to survive without governmental support. This implies that, due to the generic type of support, part of it was wasted (CPB, 2021).

In Portugal, in the period 2020–2021, almost one third of the national workforce benefited from the ‘simplified lay-off’, which is the type of support with the highest fiscal impact. Furthermore, the ‘APOIAR’ program caused the greatest impact in 2021 among the various business support measures (1.1 billion euros to help about 100,000 businesses). Businesses that benefited from this kind of support were obliged to retain employment and not pay out profits or other funds to partners. Unemployment rose at the start of the pandemic, from 6.7% in 2019 to 7.1% in 2020, but unemployment fell to 6.3% at the end of 2021. In addition, the bankruptcies index became lower in 2022 than in 2019 and GDP increased to higher levels than in 2019.

Table 2 summarizes our evidence on the impacts of COVID-19 business support on fiscal matters and employment in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal, including possibly relevant antecedents for these impacts, as derived from our theoretical framework about financial resilience in Figure 2.

| Countries | Antecedents | Impacts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal opportunities and extent of support* | Governmental structure (federal or unitary)** | Governance score*** | Fiscal impact (pre-peak-post)**** | Employment impact (pre-peak-post)***** | |

| Belgium | Low opportunity: 100% support: 5.3% | Federal (more coordination) | High: 1.3 | 100–109–105% | 6.2–6.3–5.6% |

| Germany | High opportunity: 60% support: 4.3% | Federal (more coordination) | High: 1.5 | 62–69–66% | 3.3–3.7–3.1% |

| Netherlands | High opportunity: 52% support: 4.1 % | Unitary (less coordination) | High: 1.6 | 53–53–51% | 5.1–4.2–3.5% |

| Portugal | Low opportunity: 120% support: 2.3% | Unitary (less coordination) | Moderate: 1.0 | 121–125–114% | 7.7–6.6–6.0% |

- * indicates fiscal opportunity measured as debt over GDP in pre-COVID-19 year 2019 (see Figure 3); COVID-19 business support measured as expenditures over GDP in 2020–2021 (see Table 1).

- ** indicates more coordination between government layers can give rise to a less effective support.

- *** indicates scores are average values over 2015–2021 based on worldwide governance indicators of the World Bank; scores range from –2.5 (bad) to 2.5 (good) (source: wigidataset).

- **** indicates measured as debt over GDP as an average of 2017–2018–2019 values (pre-COVID-19 years), 2021 (peak COVID-19 year), and 2022 (post-COVID-19 year).

- ***** indicates measured as unemployment rate as an average of 2017–2018–2019 values (pre-COVID-19 years), 2021 (peak COVID-19 year), and 2022 (post-COVID-19 year).

Table 2 reveals that the fiscal impacts have a similar pattern in all four countries: after a rise of indebtedness during the COVID-19 years 2020–2021, a recovery is noted after these years. The impacts on unemployment are different for two pairs of countries: while in Belgium and Germany an initial rise in unemployment is followed by a decrease, in the Netherlands and Portugal unemployment decreases between 2019 and 2022. However, differences between both pairs of countries are small. This analysis suggests that a main reason for these differences might be the government structure: a unitary rather than a federal state with relatively low coordination burdens may enhance support effectiveness. It is noteworthy that support is far less generous in Portugal than in the other countries, which can be explained by Portugal's high level of indebtedness, while the governance score is only moderate. Portugal therefore performs well given the limited resources spent: so, it can be labelled as a ‘cost-effective’ provider of business support.

Inspired by the financial resilience framework in Figure 2, the above explorations give rise to the following reflections on the influence of antecedents on the impacts of business support. Government structure—either federal or unitary—seems to matter. Belgium and Germany as federal countries are spending more on business support than the Netherlands and Portugal as unitary states, while their performance is not significantly better. A strong governance does not have a systematic influence on business support effectivity. Germany and the Netherlands with higher governance scores than Belgium and Portugal do not perform better than the latter two. Moreover, the influence of fiscal opportunities on delivering support is mixed. Whereas the high level of indebtedness may have prevented Portugal from providing generous support, almost equally indebted Belgium provided the most generous support. The generosity of support in the less indebted countries, Germany and the Netherlands, is also high.

Prudence is required regarding the interpretation of the figures in Table 2. The table can only present the possible impacts of business support in the short term, while longer-term impacts can be different. Moreover, causal links between antecedents and impacts may be disputable. This is especially the case with regard to debt over GDP, where many other factors can be influential, for instance in Belgium the government had to spend billions of euros to cope with flood damages. In addition, government governance is assumed to be equally rated for business support institutions as for government as a whole, for which indicator values were used. Hence, the figures in Table 2 need to be understood in combination with the detailed evidence on each of the countries, as presented earlier in this subsection.

LEARNING FROM COVID-19 BUSINESS SUPPORT

This section discusses the learning effects of the COVID-19 business support processes and how these might impact the handling of future crises. Learning includes information-sharing and consultation within the government sector, as well as monitoring, risk management, and critical thinking. These issues are related to anticipatory capacities and responses (see Figure 2). As this type of information cannot be derived directly from statistical data, while detailed information from literature is still lacking, our evidence is based on two interviews in each of the four countries, that is, from the responsible ministry or an organization that actually provided support, and the court of auditors. Interviews were conducted by the authors and lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

Consultation and Information-sharing

All four countries were overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Without a quick intervention from their governments, many employees would have lost their jobs. Providing business support on short notice with limited monitoring and surveillance was therefore the highest priority. This meant that in these first months of the pandemic, room for information-sharing and critical thinking within the governmental system was widely lacking. But after this first episode, governments became more prone to benefiting from expertise and experiences of other stakeholders in government.

While in Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal governments were not prepared for providing business support, evidence about this issue in Belgium seems inconclusive. While the Belgian Court of Auditors signals an absence of preparedness, the agency for delivering support in Flanders claims that it was well-prepared, given its long-lasting experience in this domain that dates back to 2002.

The Belgian Court of Auditors has encouraged business support agencies to develop more formal information systems for underpinning support decisions, and it has also warned against a lack of structural consultation among support-providing agencies, which could be harmful for providing justified support. Despite the advice from the Court of Auditors, no formal consultation structure of various actors in the provision of business support could be realized. The German Federal Court of Auditors criticized the lack of a legal framework for delivering support, including confusion about responsibilities at the federal and Länder level. The German Ministries for Economic Affairs at the federal and Länder level confirm that they had to improvise in the early stages of the crisis, while there was a good information flow. The Dutch agency for wage support delivery became involved in information-sharing and consultation with other agencies with similar tasks, but also with the tax office (about recovery of unjustified payments), and the Chambers of Commerce (about the most vulnerable branches). A representative of the Ministry of Economic Affairs in Portugal highlights the involvement of the Association of Certified Accountants for assuring information provision for proper business support. In addition, the Court of Auditors highlighted the need for a clear definition of target groups and specific objectives in the design of future support programs.

Risk Management

In Belgium no risk management systems were in place. There were initiatives for developing such systems, but the energy crisis hindered the realization of these initiatives because priority had to be given to the operations of giving business support.

In Germany risk management was criticized by the Federal Court of Auditors because the federal government was the only funder of the support. In addition, it was acknowledged that a revision of the support would have been desirable when the crisis turned out to be less threatening than initially expected.

The agency that executed wage support in the Netherlands indicates that risk management systems were in place, and there was also intensive coordination with the audit and enforcement departments of the ministry of Social Affairs and Employment that is politically responsible for this type of support. Wage support is divided into subsequent stages of three to six months and at the beginning of each stage a risk assessment was made, for example about improper data supply by companies, or improper use of regulations.

Risk management systems were also developed by the Portuguese central government in the form of control and auditing systems, sometimes based upon requests by the European Union. In this respect the collaboration with the Tax Office and the auditing profession is seen as a guarantee for avoidance of risks in the application and payment of support. The administrative simplification and automation of the application process became more efficient and transparent.

Critical Thinking and Change

Whilst information-sharing and consultation refer to an anticipatory capacity of openness towards inputs from other stakeholders, critical thinking and related action might have stronger consequences. It is concerned with an inclination to be prone to revising existing practices. Our evidence from the interviews reveals that critical thinking was seen as infeasible during the first months of the pandemic, due to the pressures for delivering fast support, but it gradually took shape.

The Belgium government made the decision to make business support more sector-specific in the course of the pandemic. In addition, data systems were improved to mitigate the risks of ex-post controls and repayment claims.

In Germany, it was determined that unnecessary funding and double funding, at both the federal and Länder level, should be excluded from the outset in the future. In addition, the various support measures must be more specific and more clearly demarcated from each other, although support should not be sector-specific. The Federal Court of Auditors clearly preferred the bouncing-back strategies in business support. While the auditors have criticized the insufficient ex-post performance review, the ministries of economics at the two government layers note that the learning effects have already been used for more recent crisis management.

The agency for providing wage support in the Netherlands argues that this support was gradually enhanced through so-called client trajectories, in which various actors coordinated their contributions, while clients are only faced with one service point. Although generally applicable wage support was reconsidered in this country, the alternative option of sector-specific support was ultimately rejected due to a lack of reliable data for handling applications. The Court of Auditors signalled deficiencies in the control systems for fixed-cost support, which were partly attributed to the application of automated devices for decisions regarding applications.

In Portugal a system for spotting vulnerable sectors was developed in order to effectively provide sector-specific support. The Court of Auditors promoted learning by advocating openness of different institutions to cooperate in the future.

Overall Assessment

This section about lessons learned from COVID-19 business support indicates that the need to provide quick support after the outbreak of the pandemic gave little room for consultation and information-sharing among actors within the governmental system. But, in the course of the pandemic these actors became more prone to benefiting from the experiences of others. The evidence about the development of risk management systems and critical thinking about existing support practices suggests less progress. Intentions for installing risk management systems were not realized in some countries due to, among other factors, pressures for delivering support during the energy crisis. Neither critical thinking nor related actions, in which alternative options for more sector-specific business support could have been considered, were developed to a significant extent. In sum, a quick response to the virus outbreak by providing business support was a symptom of well-functioning crisis management, but there was a lack of ex-post monitoring and critical reflection.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

This paper investigates COVID-19 business support in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Because of the need to provide quick and effective support to firms suffering from COVID-19 constraints, simple and generally applicable support arrangements were launched for wage or fixed-cost support that did not require substantial control or monitoring. Also, already existing arrangements, such as unemployment benefits, were revitalized for COVID-19 support. The paper also investigates the dynamics of the support during the pandemic. In this respect, governments had to balance the desire to return to normal economic circumstances that called for stricter access conditions, and the need to provide support for a longer-lasting pandemic that required the opposite. We developed a financial resilience framework, inspired by Barbera et al.'s (2023) more general framework, but now aligned with business support, which reveals that coping responses to the crisis were aimed at bouncing back to the situation before the virus outbreak. Bouncing-forward responses, such as setting up new post-shock configurations, were largely absent. This was due to the need for quick and adequate responses that gave limited time for critical reflection. The impacts of the support were positive, that is, the number of bankruptcies remained low, and unemployment recovered quickly after a first increase in two of the four countries, while it even gradually decreased in the other two countries. This study reveals that unemployment and fiscal impacts diverged among the four countries, and it is suggested that only one factor was influential: unitary states performed better than federal states. This outcome of our study resonates with earlier studies, which indicate that diverging or complementary approaches at different governmental layers in federal countries result in additional expenses, whereas unitary countries potentially rely on a more coherent (and less costly) approach for support (Liu and Greva-May, 2021, p. 139; Chen et al., 2021). Our paper also reflects on the lessons learned from COVID-19 support for support in future crises, such as the recent energy crisis, and shows that consultation and information-sharing within the governmental system were gradually taking shape, while the development of risk management systems and critical reflections of existing practices remained limited.

Our study makes significant contributions to the existing body of knowledge about government responses to the COVID-19 crisis. First, it develops a tailor-made framework for understanding crisis-related business support from a financial resilience perspective. This framework systematically addresses various types of coping and anticipatory responses to the crisis, including their financial and non-financial impacts. Second, our study investigates support programs under different governmental structures (federal and unitary), fiscal capacities, and scores on government governance dimensions, and points to important links between these antecedents and impacts.

Our investigations are subject to limitations, which also imply suggestions for future research. The number of countries is limited to four, whereas a larger number of countries could contribute to finding more generalizable outcomes. Hence, a potentially interesting route for research is a comparative analysis based on a quantitative examination of many countries about the effects of governmental structure, fiscal capacities, and governance dimensions on governmental expenditures for business support programs, and employment outcomes. In addition, we only interviewed a limited number of key actors in the domain of COVID-19 business support, whereas a larger number of interviews could give further evidence about the underpinnings of the provided support. Finally, an assessment of the vulnerability of various subsectors within the business sector could enrich the analysis about the effectiveness of the support, as would an analysis of the support impacts over a longer time frame.

Biography

Jan van Helden ([email protected]) is at University of Groningen. Tjerk Budding is at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Patricia Gomes is at Polytechnic University of Cávado and Ave. Mario Hesse is at University of Leipzig. Carine Smolders is at Ghent University.