Measurement Model or Asset Type: Evidence from an Evaluation of the Relevance of Financial Assets

Abstract

This study focuses on the operation of the Level 1, 2, and 3 measurement uncertainty hierarchy embedded in the SFAS 157 accounting for financial assets. Prior studies conclude the SFAS 157 fair value measurement model and prevailing financial market conditions are causal factors for the lower value relevance of the Level 3 financial assets. The contribution of our paper is to provide evidence on an additional, hitherto undocumented source of measurement uncertainty impacting the relevance of SFAS 157 financial assets to investors: the type of asset appearing in Level 3 financial assets as a result of asset securitizations and SFAS 140 securitization accounting. The paper also presents evidence that suggests the SFAS 166 amendments were unable to fully address informational transparency for financial assets arising from securitizations. The key contribution is evidentiary insights suggesting the prescribed measurement model has a relatively lower impact on measurement uncertainty and relevance of financial assets compared to the effects of the asset type.

This study examines differences in the relevance of financial assets measured in accordance with SFAS 157 Fair Value Measurements (FASB, 2006), which envisages increasing measurement uncertainty across a fair value hierarchy (i.e., Level 1 < Level 2 < Level 3). Our paper aims to extend the literature with evidence on the source of measurement uncertainty affecting the relevance of financial assets measured using the Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs in accordance with SFAS 157. We consider this issue in the context of asset securitizations that were accounted for in accordance with SFAS 140 Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguishments of Liabilities (FASB, 2000) until 2009, and subsequently under the amendments in SFAS 166 Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets (FASB, 2009) (hereafter referred to as the SFAS 166 period). Importantly, whereas asset securitizations primarily gave rise to financial assets measured with SFAS 157 Level 3 inputs under SFAS 140, in the SFAS 166 period (after 2009) there was increasing recognition of financial assets from securitizations measured with SFAS 157 Level 2 inputs.

This setting provides the opportunity to evaluate whether differences in measurement uncertainty and relevance are attributable to the measurement model adopted or alternatively the type of assets involved. The prior literature finds the Level 3 assets from the SFAS 140 period (up to 2009) are less value relevant compared to Level 1 and Level 2 financial assets, with this effect ascribed to the SFAS 157 fair value model (Song et al., 2010). Goh et al. (2015) revisit this issue and conclude financial market uncertainties (in the 2008–2009 crisis period) are the key driver of measurement uncertainty impacting the Level 3 financial assets. However, a question yet to be addressed is the relative impact of asset securitizations, and the associated standards SFAS 140 and SFAS 166, on the nature of the financial assets and the attending measurement uncertainty and relevance.

To address the gap in the literature, this paper examines the following effects: (1) measurement uncertainty arising from the fair value measurement model prescribed by SFAS 157 as suggested by Song et al. (2010) and measurement uncertainty arising from the prevailing market uncertainty effects as suggested by Goh et al. (2015); and (2) measurement uncertainty attributable to the nature of the financial assets arising from asset securitizations. The relevance construct refers to investor usefulness and takes its meaning from the SFAC No. 8 Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (FASB, 2010, QC6): ‘Relevant financial information is capable of making a difference in the decisions made by users’. To attempt to identify whether securitizations is an important source of measurement uncertainty, the study is set in 2008–2014 to provide a sample of firms (i) exposed to the financial market crises and aftermath, (ii) exposed to the growth and subsequent cooling of the asset securitization market, and (iii) exposed to the effects of accounting rules for asset securitizations in SFAS 140 and subsequent to the SFAS 166 period. 1 The paper's key contribution is evidence that asset type rather than the accounting measurement model appears to be a primary driver of asset measurement uncertainty, and consequently the relevance, of financial assets.

The motivation for this paper lies in the renewed measurement debate following the 2008–2009 financial crisis. An accounting measurement model capable of producing relevant information for decision making has been a significant accounting issue for the last 50 years (e.g., Chambers, 1966) with the deliberations fundamentally extending into the conceptual framework projects (Zeff, 2013). Accordingly, there is continuing demand for evidence on the practical relevance of prescribed measurement models for users of general purpose financial reports. The FASB and IASB conceptual framework project (issued in 2010) produced the ‘relevance’ definition included in SFAC No. 8 Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. The IASB revisions exposed in 2015 introduce a ‘measurement uncertainty’ dimension to this relevance definition (AASB, 2015); specifically, measurement uncertainty affects relevance when a measure for an asset or a liability cannot be observed directly and must therefore be estimated. Much of the debate to date has focused on measurement uncertainty arising from the accounting measurement model. However, the IASB measurement uncertainty concept recognizes that assets themselves differ in their measurability. Recognition of this issue by the IASB does highlight a potential narrowness in the critics’ arguments that the fair value measurement model under SFAS 157 created measurement uncertainty for financial assets thereby exacerbating the financial crisis (e.g., Berman, 2008). 2 In light of these issues, this paper aims to provide evidentiary insights on the contribution of the measurement model type versus the asset type (assets from securitizations) to the measurement uncertainty of SFAS 157 financial assets.

The analyses employ a sample of banks comprising 5,672 firm quarters over the period 2008 to 2014. We start with the full sample of banks that covers the financial crisis and post crisis time periods, includes securitizers and non-securitizers, and covers the application of SFAS 140 until 2009 and then the SFAS 166 period from 2010 until 2014. For this sample of banks, we first confirm the Song et al. (2010) finding that financial assets measured using the Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are value relevant. Further, we observe the expected pattern of decreasing value relevance moving from Level 1 down to Level 3 inputs consistent with the measurement uncertainty hierarchy built into SFAS 157. However, inconsistent with Song et al. (2010) there is no significant difference in the relevance of financial assets measured with Level 2 and 3 inputs.

Next we repeat the analysis for the 1,442 bank quarters not undertaking asset securitizations over 2008–2014. For these non-securitizers, the results show the value relevance of the Level 1, 2, and 3 financial assets are not statistically different from each other. Accordingly, the second contribution of the paper is to suggest the source of measurement uncertainty reflected in the implemented SFAS 157 hierarchy of uncertainty inputs is likely the nature of the assets arising from securitizations. Concerns expressed about measurement uncertainty arising from the SFAS 157 fair value measurement model may, therefore, be overstated.

To further illuminate the source of measurement uncertainty impacting financial assets we focus separately on 1,667 firm quarters in 2008–2009 when SFAS 140 applied and 4,005 firm quarters in 2010–2014 when SFAS 166 applied. These tests employ securitizer dummy variable interactions to further evaluate the impact of asset securitizations on measurement uncertainty and the relevance of financial assets measured in accordance with SFAS 157. In addition, we provide insights into the impact of the SFAS 166 amendments to SFAS 140, which changed the practice of the seller retaining the riskiest securities from the securitization portfolio to seller's retaining securities that provided a proportional representation of the securitization portfolio.

For the sample of 1,667 firm quarters during the SFAS 140 period and until 2009, once the interactions capturing securitization effects are included, we do not observe the SFAS 157 pattern of increasing measurement uncertainty and decreasing relevance moving from assets measured with Level 1 to Level 3 inputs as documented by Song et al. (2010). Instead, the results suggest that non-securitizers’ financial assets measured with Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are not statistically different from each other in terms of their value relevance, while Level 3 financial assets for securitizers that would have mainly comprised financial assets from securitization are not value relevant. 3 This finding is consistent with the securitizers’ asset type (residual assets from securitizations) comprising so much measurement uncertainty that there is no relevant information for investors. Conversely, the evidence is consistent with the non-securitizers’ asset type(s) comprising so little measurement uncertainty that the Level 1, 2, and 3 financial assets are value relevant but with no difference in value relevance for the three types of inputs. Accordingly, the third contribution of this paper is to provide evidence suggestive of issues in the accounting for asset securitizations under SFAS 140. In addition, while Goh et al. (2015) argue prevailing financial market conditions caused the lower value relevance of Level 3 financial assets, our results suggest the probable explanation is the type of asset appearing in Level 3 financial assets as a result of securitization practices and SFAS 140 securitization accounting (until 2009).

A remaining issue is whether the SFAS 166 amendments to SFAS 140 were successful in addressing the SFAS 140 securitization accounting issues. Our final tests attempt to provide insights on this issue from a sample of 4,005 firm quarters in 2010–2014 in the SFAS 166 period. For the non-securitizers, the results are the same as those in the period to 2009 with the financial assets measured with all three levels of input being value relevant, but tending not to be statistically different from each other in their value relevance excepting Levels 1 and 2. For the securitizers, we find neither the Level 2 nor Level 3 financial assets are incrementally value relevant. SFAS 166 amendments are implicated in this result because the amendments caused many financial assets arising from securitization to be measured using Level 2 inputs instead of Level 3 inputs. In the SFAS 166 period, the securitization residual assets are now mixed in with liquidity assets in the Level 2 category. Accordingly, the final contribution of the paper is to suggest that SFAS 166 was unable to address the measurement uncertainties associated with securitization assets. Fine grained disclosures detailing the types of financial assets held by banks are still not made available under SFAS 166 or any other standard. This opaqueness leaves investors in the dark and hence the uncertainty surrounding securitization likely taints the whole Level 2 category in relation to its value relevance.

Regulatory Background and Hypothesis Development

Fair Value Accounting for Financial Assets under SFAS 157

As the financial crisis of 2008–2009 unfolded, fair value financial reporting practices by banks attracted considerable criticism. In the US, the regulatory basis for determining fair values is SFAS 157 Fair Value Measurements, which was issued in 2006. 4 A number of accounting regulations rely on this accounting standard, including SFAS 140 Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguishments of Liabilities and SFAS 166 Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets.

In general, fair value under SFAS 157 is a market measurement based on market prices or estimated using assumptions. ‘Fair value’ is defined as the price that would be paid for the transfer of an asset (or liability) in an orderly transaction (para. 5). Considerable guidance is also provided on how to implement this measurement including what is an appropriate market (para. 8), the characteristics of participants (para. 10), valuation techniques (para. 18), and the inputs into valuation (para. 21). At the heart of the SFAS 157 measurement model is a scheme for estimating fair value on an increasing continuum of measurement uncertainty, which is identified as the ‘fair value hierarchy’ (para. 22). The top of the hierarchy is fair value measured using Level 1 inputs. Level 1 is the lowest measurement uncertainty and the preferred inputs, if available, comprise unadjusted quoted prices for identical assets in active markets. Moving down the continuum, fair values based on Level 2 inputs are subject to greater measurement uncertainty. These inputs are observable (directly or indirectly) in active markets and can include the price of similar assets, with necessary adjustments to reflect the specific nature of the asset (or liability) being measured. At the bottom of the continuum is fair value measurement using Level 3 inputs that are subject to the greatest measurement error, which SFAS 157 tags as the lowest priority. Level 3 inputs are not observable in active markets and firms may, therefore, base measurement on internal data. Importantly, the SFAS 157 hierarchy of measurement identifies distinct categories of assets where increasing measurement uncertainty is expected, providing the opportunity to study the links between measurement uncertainty and the relevance of the financial information.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, as the business practices of the banks and other stakeholders were exposed, the SFAS 140 accounting practices for the securitization of financial assets also drew criticism. Asset securitizations were commonly used by banks to avoid regulatory capital constraints (Jones, 2000) and increased the banks’ overall economic risks (Thomas, 1999). Securitization transactions were initially accounted for under SFAS 140 Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguishments of Liabilities (issued in 2000). The most prevalent and perhaps problematic asset securitizations were those undertaken using a qualifying special purpose entity (SPE), for which consolidation was not required. The transfer of the financial assets to the SPE was accounted for by the transferor as a sale (para. 9), with all of the financial assets transferred being derecognized, any residual interests recognized at fair value, and any gain on sale recognized in earnings (para. 11). The residual interests included mortgage service rights together with junior securities from the securitized tranche retained by the transferor in recognition of the agency problems inherent in these transactions. These residual interests are unique to the portfolio of financial assets securitized and would not be traded in active markets. Accordingly, these interests would be measured using Level 3 inputs. From the perspective of the type of asset, the securitizations were opaque transactions and, accordingly, the ensuing Level 3 assets were more than likely difficult information for investors to process (Ryan, 2008).

Hence, for firms undertaking asset securitizations accounted for under SFAS 140 (until 2009) there would be two impacts on the financial statements. First, there would be increased income arising from the crystallization of gains on the origination and securitization of the financial assets. Second, there would be an accumulation of residual interests for which measurement with Level 3 inputs would be required (Cowan and Cowan, 2004). 5 There may also be unrecognized liabilities arising from implicit recourse agreements (Barth and Landsman, 2010; Higgins and Mason, 2004; Landsman et al., 2008; Schipper and Yohn, 2007). Wells Fargo and Company (WFC) provides examples of these effects. WFC disclose that approximately 18% of its fair value assets required measurement with Level 3 inputs and ‘virtually all of our financial assets valued using Level 3 measurements represented mortgage service rights’ (WFC, 2008, p. 41). East West Bancorp Inc. (EWBC, 2008, p. 11) provides a broader elaboration of asset holdings measured with Level 3 inputs that ‘typically includes mortgage servicing assets, impaired loans, private label mortgage-backed securities, retained residual interests in securitizations, and purchased residual securities’.

The SFAS 140 accounting practices for securitizations changed when SFAS 166 Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets took effect for financial years commencing after 15 November 2009. SFAS 166 was a response to criticism of accounting practices for asset securitizations and placed limits on the use of qualifying SPEs and the circumstances in which the transfer of financial assets could be recognized as a sale (para. 2). Accounting for the transfer as a sale by the transferor is now limited to circumstances where the transferor retains a proportionate (not risk stratified) ownership interest in the assets transferred. To the extent that asset securitization still occurs, some of the retained interests (e.g., mortgage service rights) will still be valued with Level 3 inputs. However, other retained interests that are proportionate interests in the securitized assets are more likely to have similar assets traded in markets. This market would provide information enabling measurement with Level 2 inputs, and according to the uncertainty hierarchy built into SFAS 157, measurement uncertainty would be lower than previously under the retention of risk-stratified interests. Hence, in the SFAS 166 period, securitization accounting is expected to be accompanied by a relative increase in financial assets measured with Level 2 inputs and a decrease in assets measured with Level 3 inputs.

Importantly for this study, this regulatory change provides the opportunity to evaluate whether the impact of measurement uncertainty on relevance arises from the fair value measurement hierarchy in SFAS 157, or alternatively from measurement uncertainties associated with the type of assets arising from asset securitizations. Further, the regulatory change allows an analysis of the success of the SFAS 166 amendments focusing on the information environment for financial assets arising from the asset securitizations.

Hypothesis Development

The focus of this study is the impact of measurement uncertainty on the relevance of financial statement information in the context of fair value accounting for financial assets. Accordingly, while there are significant literatures considering alternative measurement models (e.g., Chambers, 1966), and whether information provided on a basis other than historic cost is relevant (e.g., Barth and Clinch, 1998), our attention is directed to the literature on the application of fair value accounting to financial instruments.

The determination of a relevant and implementable basis for measuring financial assets and liabilities has long been an issue. Subsequent to the 1980s savings and loans crisis, the limitations of historic cost accounting for financial assets and liabilities was identified along with evidence that fair value accounting may have provided more timely warnings of emerging problems (Allen and Carletti, 2008). These past information failures were a factor in the decision to require fair value disclosures for financial instruments in SFAS 107 Disclosures about Fair Value of Financial Instruments (issued in 1991). SFAS 157 followed in 2006, which identified bases for determining fair values, and this was prescribed for certain financial assets and liabilities by specific regulations.

However, fresh concerns about fair value measurement emerged in the aftermath of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. For example, Wayne Abernathy, executive vice-president for financial and regulatory affairs at the American Bankers Association argued the application of fair value accounting forced banks to write down assets where little or no market existed, contributing to a downward spiral of the financial system (Berman, 2008). The essence of the criticism is fair value accounting makes financial statements volatile and fair value has such high measurement uncertainty that the relevance of financial statement information is undermined.

Concerns about high measurement uncertainty and low relevance of financial statement information are identified in the literature. Nelson (1996) and Eccher et al. (1996) find no convincing evidence that fair value disclosures of financial assets are value relevant to investors. They attribute the lack of value relevance to the measurement uncertainty inherent in fair values. However, Barth et al. (1996) find fair value disclosures are value relevant after contextual conditioning variables are introduced. Their evidence suggests fair value disclosures are value relevant despite possible measurement uncertainty. Further, Barth et al. (1996) note that the amount of information about financial assets may vary across different types of assets thereby affecting the assets’ value relevance.

More recently, researchers have directed their attention to fair value measurement for a particular class of financial assets; those measured using the Level 3 inputs as defined in SFAS 157. In contrast to financial assets measured with Level 1 inputs (quoted prices in active markets for identical assets) or Level 2 inputs (observable either directly or indirectly), measurement with Level 3 unobservable inputs is subject to potentially greater measurement uncertainty. This aspect of the implementation of SFAS 157 has generated concerns that measurement uncertainty will undermine the relevance of reported financial asset information. Song et al. (2010) considered this issue and found the financial assets measured using Level 3 inputs are less value relevant compared to those assets measured with Level 1 and Level 2 inputs. However, Song et al. (2010) studied the operation of SFAS 157 in the financial crisis period and, as suggested by (Goh et al., 2015), it is unclear whether their finding is due to the operation of SFAS 157 or is an artefact of the financial crisis. In this paper, we argue that the prior literature has omitted variables relating to the ‘type of asset’, and in particular, that financial assets from asset securitizations are implicated in the lower value relevance of some types of financial assets. Accordingly, as a prelude to specific predictions relating to financial assets from asset securitizations, the first hypothesis examines whether the Song et al. (2010) and Goh et al. (2015) results are observed over the longer period 2008–2014, which spans the financial crisis and the years thereafter.

H1.Financial assets measured using fair value measurement under the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 hierarchy of inputs are value relevant, with the highest measurement uncertainty and lowest value relevance for the financial assets measured with Level 3 inputs.

In this general setting, that does not distinguish the financial assets of securitizing firms from non-securitizing firms, a lack of support for Hypothesis 1 would suggest that other forces in addition to measurement under the SFAS 157 hierarchy of inputs are in play. Understanding whether this is indeed the case is important for considering whether there may be a case for constraints on the use of fair value measurement or whether the focus is more usefully directed to specific assets and transactions. Measurement uncertainty is potentially greatest in the case of financial assets measured using Level 3 inputs, putting these assets at the forefront of deliberations on the measurement model. 6

There is precedent in the literature for suggesting the type of assets impacts measurement uncertainty and relevance. For example, Barth et al. (2012) suggest the relevance of fair value financial instruments may be affected by their nature (i.e., asset type) and the authors direct their attention to financial assets arising from asset securitizations. If asset type rather than accounting measurement model was the fundamental source of measurement uncertainty, this would mean some assets measured using Level 3 inputs would be value relevant while others would not, depending on how much internal information is available to inform the Level 3 inputs under SFAS 157. This is a significant issue because it has implications for research design in studies of the relevance of assets arising from accounting standards. Moreover, a role for asset type implies that fair value measurement might not be the over-arching concern for standard setters aiming for relevant accounting information. Instead, the goal of relevant financial reporting might more pertinently focus on the accounting rules for the particular type of asset and transaction. In this context, Barth and Landsman (2010) identify two aspects of concern in accounting for asset securitizations. First, SFAS 140 requires that the residual interest assets resulting from asset securitizations remain on the securitizer's balance sheet (e.g., mortgage service rights and junior securities). Problematically, prior to the amendments in 2009, the requirements of SFAS 140 led to these residual interest assets coming from the riskiest of risk-stratified tranches of securitized assets. Moreover, the retained service rights are also accompanied by undisclosed levels of implicit recourse provided to the purchaser of the securities. Second, there is significant opacity surrounding the securitization transaction reporting particularly pertaining to detailed breakdowns of financial assets and the extent of unrecognized obligations relating to qualifying SPEs.

Accordingly, there is a question surrounding the source of measurement uncertainty, and hence value relevance of the assets measured using the SFAS 157 inputs. We do know that asset securitizations accounted for under SFAS 140 give rise to financial assets that are risky, not traded, and difficult to measure (e.g., Ryan, 2008), and hence, would intuitively fully invoke the hierarchy of measurement uncertainty built into SFAS 157. Conversely, the financial assets reported by non-securitizing firms that are not subject to SFAS 140 tend to come from more standardized and historically transparent transactions. We argue the latter financial assets are therefore more observable assets that are less likely to generate the strictly increasing pattern of measurement uncertainty across the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 input hierarchies. We therefore make the following prediction.

H2a.For non-securitizing firms, financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 hierarchical inputs are value relevant, but do not display a strictly decreasing pattern of value relevance across the Level 1, 2, and 3 input assets.

Support for this hypothesis would suggest that the value relevance of the financial assets under SFAS 157 is an asset ‘type’ effect, while rejection of this hypothesis would suggest that the value relevance of the financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 hierarchy is a fair value measurement model or financial market conditions effect.

We next include controls for asset securitization to further evaluate whether the type of asset has an impact on measurement uncertainty and value relevance. We focus first on asset securitizations accounted for in accordance with SFAS 140 prior to amendments at the end of 2009. A consequence of asset securitization in this period is an accumulation of residual interests such as junior securities and mortgage servicing rights on the balance sheet. It is only possible for the firms to measure these assets using Level 3 inputs. As discussed above, for banks that securitize assets these residual interest assets would represent a significant component of their assets measured with Level 3 inputs. Measurement uncertainty for these residual assets is likely to be high because they are ‘junior’ securities retained to address agency problems and are the most exposed to the risk of the assets securitized (Cowan and Cowan, 2004; Jones, 2000). There is also evidence that firms securitizing more risky assets are likely to be required to hold more residual interests (Chen et al., 2008). In relation to mortgage service rights, value will be contingent on the quality of the securitized assets with which problems emerged as the financial crisis unfolded (Ryan, 2008). Because of the banks’ difficulties measuring these residual assets without the existence of an active market, it is expected there will be greater measurement uncertainty and relatively lower relevance for the securitizers’ Level 3 assets compared to the non-securitizers’ Level 3 assets that come from less opaque securitization transactions.

H2b.In the SFAS 140 period (i.e., 2008–2009), financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 hierarchical inputs are value relevant, with the highest measurement uncertainty and lowest value relevance for the financial assets measured with Level 3 inputs for the securitizing firms, compared to the financial assets measured with Level 3 inputs for non-securitizing firms.

The implication of this hypothesis is that measurement uncertainty is a first order function of the type of assets under measurement, while a rejection of the hypothesis suggests the value relevance of the financial assets is a SFAS 157 fair value model or financial market conditions effect.

The SFAS 166 amendments to SFAS 140 have two important accounting impacts. First, it is more likely that similar securities to those retained from securitizations would be trading in markets. Therefore, measurement of some of the retained interests would have now employed Level 2 inputs. Second, there is a lower accumulation of high-risk financial assets by the transferor, for which measurement with Level 3 inputs is required (because of proportional rather than risk-stratified retention of interests in the securitized assets). If these SFAS 166 changes address measurement uncertainty concerns there is expected to be no difference in the relevance of assets measured with Level 2 and Level 3 inputs for firms undertaking asset securitizations compared to non-securitizers.

However, an additional measurement uncertainty effect is that the Level 2 input assets also include an undisclosed portion of liquidity assets. Therefore, even though the retained interests are likely less risky with more information available for measurement on average under the SFAS 166 amendments, there may still be significant uncertainty about the riskiness of the assets from securitizations as well as uncertainty about the composition of the Level 2 category. These uncertainties (especially coming on the back of the financial crisis) would be expected to decrease the information conveyed to investors by the Level 2 and 3 input assets from securitizations.

H2c.In the SFAS 166 period, financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 hierarchy inputs are value relevant, with the highest measurement uncertainty and lowest value relevance for financial assets measured with Level 2 and 3 inputs for securitizing firms compared to non-securitizing firms.

The implication of this hypothesis is that issues with asset securitization were not fully addressed by the SFAS 166 regulatory amendments. Conversely, if the hypothesis is rejected and there is no difference in the value relevance of Level 2 and 3 input assets for securitizing firms compared to non-securitizing firms, the implication is that the SFAS 166 amendments were able to address the issues relating to financial assets from asset securitizations.

Research Design

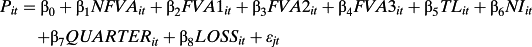

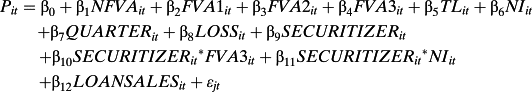

(1)

(1)The specification of equation 1 is similar to Goh et al. (2009) and Song et al. (2010) except that the test is extended to cover the financial crisis and the aftermath (2008–2014). The dependent variable, Pit, is the closing share price measured on the trading day following the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank's quarterly 40 calendar day deadline for reporting of consolidated financial statements by Bank Holding Companies. NFVA are the non-fair value reported assets measured per share for quarter t. FVA1, FVA2 and FVA3 are Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 recognized fair value financial assets per share for quarter t, respectively. TL is recognized total liabilities and NI is net income before extraordinary items and per share for quarter t. 7 Dummy variables capture the financial quarter to which the results relate (QUARTER) and whether the firm records a loss (LOSS). Recognizing the potential for implicit recourse arising from securitizations, loan sales are included for the quarter t (LOANSALES). 8 The estimation also includes firm and year fixed effects.

Equation 1 is first estimated for the full sample of 5,672 firm quarters over 2008–2014 to test Hypothesis 1. If fair value measurements are value relevant, we expect to see the effects reflected in the coefficients on the financial assets measured with Level 1 inputs (β2), Level 2 inputs (β3), and Level 3 (β4) inputs. Specifically, if measurement uncertainty is increasing and value relevance is decreasing across the SFAS 157 fair value hierarchy, the coefficients on the financial assets measured with Level 1 inputs (β2), Level 2 inputs (β3), and Level 3 (β4) inputs will be decreasing monotonically (i.e., from Level 1 to Level 3). We employ Wald statistics to evaluate the statistical significance of the estimated coefficients from a theoretical measure of one as well as differences of the coefficient from each other.

To test Hypothesis 2a, equation 1 is re-estimated while restricting the sample to the 1,442 bank quarters not undertaking asset securitizations over 2008–2014. For the non-securitizers, if there is still evidence the fair value financial assets are value relevant this effect will be reflected in the coefficients on financial assets measured with Level 1 inputs (β2), Level 2 inputs (β3), and Level 3 (β4) inputs. Furthermore, if measurement uncertainty is increasing and relevance is still decreasing down the fair value hierarchy, the coefficients on financial assets measured with Level 1 inputs (β2), Level 2 inputs (β3), and Level 3 (β4) inputs will be decreasing. Conversely, if asset type is a more important factor in measurement uncertainty, we would not expect to observe the monotonically declining value relevance for this sample of non-securitizing firms.

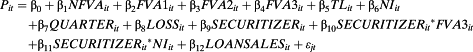

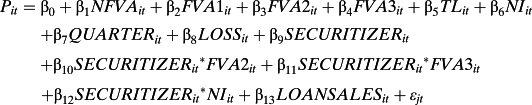

(2)

(2)The details of asset securitizations are not disclosed in the bank's financial reports, leading to asset securitizations and the associated assets and liabilities being described as opaque (Barth and Landsman, 2010). We therefore rely on the limited securitization information available from the Chicago Federal Reserve regulatory filings required by the banks meeting the loan volume threshold for filing. 9 We note that as the proportion of non-securitization assets measured using Level 3 inputs increases, the power of the tests diminishes and biases against finding a difference between the value relevance of securitizers and non-securitizers’ fair value assets. A dummy variable is coded one for banks undertaking asset securitization in fiscal quarter t and zero otherwise (SECURITIZER). The securitizer dummy variable is interacted with financial assets valued with Level 3 inputs (FVA3) to test whether there are differences in the relevance of financial assets valued with Level 3 inputs for firms undertaking asset securitizations compared to the value relevance of Level 3 assets for non-securitizers. The securitizer dummy variable is also interacted with net income (NI) because asset securitization under SFAS 140 accelerates income recognition. The dummy variable for firms undertaking asset securitization (SECURITIZER) is also expected to capture differences in the pricing of banks undertaking asset securitization. If there is evidence that financial assets valued with Level 3 inputs are subject to greater measurement uncertainty and are less relevant for firms undertaking asset securitizations, the coefficient β10 will be negative.

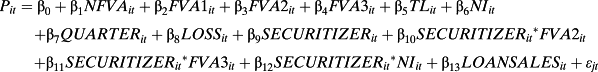

(3)

(3)Hypothesis 2c evaluates whether there are still differences in the value relevance of financial assets subject to the SFAS 157 hierarchy of inputs, and whether there are differences in the relevance of assets measured with Level 2 and Level 3 inputs for firms undertaking asset securitizations compared to non-securitizing firms in the SFAS 166 period. The changes wrought by SFAS 166 in relation to the accounting for securitizations served to move many residual assets from the Level 3 category to the Level 2 inputs category. The Level 2 measure is not as high up the measurement uncertainty hierarchy as Level 3 input measures. However, this decreasing measurement uncertainty effect comes up against a possible countervailing effect. If SFAS 166 is unable to resolve uncertainty and opaqueness of securitization transactions, investors may actually be worse off, with both Level 2 and 3 assets under SFAS 157 difficult to process. Further, an undisclosed proportion of liquidity assets are mixed with the residual assets in the Level 2 measure. Equation 3 includes an additional interaction, SECURITIZER*FVA2, to capture financial assets from securitizations measured using Level 2 inputs. If the securitizers’ financial assets measured using Level 2 and Level 3 inputs are subject to relatively greater measurement uncertainty and are thus less value relevant, the coefficients β10 and β11 will be negative, indicating they are smaller than the estimated coefficients for the non-securitizer's SFAS 157 financial assets.

Sample and Data Description

The empirical analysis requires firms to have financial assets measured under the accounting standard, SFAS 157, which had effect for financial years commencing after 15 November 2007. Further, the sample requires banks undertaking, as well as those not undertaking, the asset securitizations that are accounted for in accordance with SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 (SFAS 166 took effect for financial years commencing after 15 November 2009). The sample therefore comprises regulated depository financial institutions identified using the Wharton's Bank Regulatory Database and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. 10 To be included in the sample, firms require the following data: (a) Schedule RC-P 1–4 Family Residential Mortgage Banking Activities in Domestic Offices, which is the source of information about banks’ mortgage lending activities; (b) Compustat accounting data; and (c) CRSP stock prices measured on the trading day following the Federal Reserve Bank's 40 calendar day (after quarter end) deadline. To achieve these data requirements, the Compustat financial data are supplemented with data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago regulatory filings. Because there is a loan volume threshold before filings are required, the sample does not include the smaller banks from the bank population. Further, the number of bank quarters fluctuates according to variation in the banks generating sufficient loan volume to meet the filing volume threshold. As shown in Table 1 Panel A, this process gives rise to a sample of 5,672 firm-quarter observations for the period 1 January 2008 to 30 September 2014. Of these observations, 1,667 relate to periods when SFAS 140 was effective, and 4,005 observations relate to the post-2009 period when SFAS 166 was effective. All variables are restricted to five standard deviations from the mean to alleviate the effects of outliers, and are reported on a per share basis unless otherwise specified.

Descriptive statistics for the sample firms are reported in Table 1 Panels B, C, and D. The mean (median) value of the banks’ assets subject to fair value measurement is $34.37 ($23.47) per share, representing a sizable 20.1% of the firms’ average total assets. The mean value of assets measured on the basis of Level 2 inputs is $32.21 per share, which comprises 93.7% of the average total fair value assets, while mean assets measured on the basis of Level 3 inputs are only $0.81 per share (2.3% of the total fair value assets) but a more substantial 4.8% of shareholders’ equity.

| Panel A: Sample frequency relative to the CRSP/Compustat bank frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

# Sample Banks (SIC 6020, 6035, 6036) |

CRSP/Compustat Banks (SIC 6020, 6035, 6036) | Percentage | |

| Quarter 1 2008 | 206 | 553 | 37.25% |

| Quarter 2 2008 | 230 | 574 | 40.07% |

| Quarter 3 2008 | 244 | 594 | 41.08% |

| Quarter 4 2008 | 250 | 576 | 43.40% |

| Quarter 1 2009 | 245 | 570 | 42.98% |

| Quarter 2 2009 | 241 | 564 | 42.73% |

| Quarter 3 2009 | 251 | 555 | 45.23% |

| Quarter 4 2009 | 234 | 550 | 42.55% |

| Quarter 1 2010 | 233 | 540 | 43.15% |

| Quarter 2 2010 | 227 | 527 | 43.07% |

| Quarter 3 2010 | 228 | 524 | 43.51% |

| Quarter 4 2010 | 220 | 518 | 42.47% |

| Quarter 1 2011 | 213 | 515 | 41.36% |

| Quarter 2 2011 | 208 | 507 | 41.03% |

| Quarter 3 2011 | 206 | 505 | 40.79% |

| Quarter 4 2011 | 201 | 499 | 40.28% |

| Quarter 1 2012 | 197 | 503 | 39.17% |

| Quarter 2 2012 | 197 | 498 | 39.56% |

| Quarter 3 2012 | 197 | 493 | 39.96% |

| Quarter 4 2012 | 194 | 493 | 39.35% |

| Quarter 1 2013 | 187 | 489 | 38.24% |

| Quarter 2 2013 | 185 | 490 | 37.76% |

| Quarter 3 2013 | 182 | 484 | 37.60% |

| Quarter 4 2013 | 179 | 482 | 37.14% |

| Quarter 1 2014 | 173 | 480 | 36.04% |

| Quarter 2 2014 | 175 | 480 | 36.46% |

| Quarter 3 2014 | 169 | 470 | 35.96% |

| 5,672 | 14,033 | 40.42% | |

| Panel B: Full sample (n = 5,672 firm-quarters) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | |

| Pit | 17.272 | 14.000 | 0.190 | 94.370 |

| NFVAit | 136.310 | 124.333 | –60.604 | 731.857 |

| FVA1it | 1.350 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 71.590 |

| FVA2it | 32.210 | 23.469 | 0.000 | 261.311 |

| FVA3it | 0.806 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 25.563 |

| TLit | 153.904 | 138.419 | 0.020 | 757.078 |

| NIit | 0.124 | 0.231 | –12.574 | 5.226 |

| Loanit | 80.163 | 72.317 | 0.000 | 493.538 |

| Loansalesit | 2.695 | 0.798 | 0.000 | 63.704 |

| Securitizerit | 1 = 4230 | 0 = 1442 | ||

| Lossit | 1 = 1055 | 0 = 4617 | ||

| Panel C: SFAS 140 sample (n = 1,667 firm-quarters) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | |

| Pit | 15.553 | 12.000 | 0.190 | 94.370 |

| NFVAit | 147.155 | 132.856 | 19.506 | 731.857 |

| FVA1it | 1.882 | 0.104 | 0.000 | 71.590 |

| FVA2it | 28.306 | 21.279 | 0.000 | 205.975 |

| FVA3it | 1.233 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 24.946 |

| TLit | 162.129 | 146.284 | 7.478 | 757.078 |

| NIit | –0.186 | 0.153 | –12.574 | 4.386 |

| Loanit | 88.091 | 79.832 | 0.000 | 403.231 |

| Loansalesit | 2.507 | 0.662 | 0.000 | 49.547 |

| Securitizerit | 1 = 1212 | 0 = 455 | ||

| Lossit | 1 = 533 | 0 = 1134 | ||

| Panel D: SFAS 166 sample (n = 4,005 firm-quarters) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | |

| Pit | 17.988 | 14.800 | 0.280 | 90.990 |

| NFVAit | 131.796 | 120.867 | –60.604 | 666.464 |

| FVA1it | 1.129 | 0.037 | 0.000 | 46.369 |

| FVA2it | 33.835 | 24.579 | 0.000 | 261.311 |

| FVA3it | 0.629 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 25.563 |

| TLit | 150.480 | 135.407 | 0.020 | 691.894 |

| NIit | 0.253 | 0.265 | –10.277 | 5.226 |

| Loanit | 77.061 | 70.225 | 0.004 | 493.538 |

| Loansalesit | 2.774 | 0.844 | 0.000 | 63.704 |

| Securitizerit | 1 = 3018 | 0 = 987 | ||

| Lossit | 1 = 522 | 0 = 3483 | ||

- Panel B provides descriptive statistics for the full sample of 5,672 firm-quarters over the period 31 January 2008 to 30 September 2014. Panel C comprises 1,667 firm-quarters for which SFAS 140 was applicable. Panel D comprises 4,005 firm-quarters for which SFAS 166 applied. All variables are reported on a per share basis unless specified otherwise.

- Pit equals closing share price for firm i for quarter t measured on the trading day following the Federal Reserve Bank's 40 calendar day deadline for consolidated financial filing (after quarter end); NFVAit are assets that do not require fair value measurement for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it are assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it are assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it are assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit are total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; SECURITIZERit is a dummy variable coded one if the firm undertook asset securitization in the current quarter t for firm i and zero otherwise; LOANSALESit are the amount of closed-end 1–4 family mortgage loans sold in quarter t for firm i; and LOSSit is a dummy variable coded one if firm i recorded a loss in quarter t and zero otherwise.

These statistics might suggest that with so few assets subject to measurement with Level 3 inputs any concerns with measurement uncertainty are misplaced. However, while the Level 3 financial assets reported by the banks were small the data is skewed and, importantly, the potential leveraging on the reported financial assets was large. In particular, the securitizers’ unrecognized obligation from their implicit recourse could have required absorbing losses up to the full amount of transferred assets (Niu and Richardson, 2006, p. 1108). This leveraging effect is likely an issue for some banks in the sample considering the full sample includes 4,230 (74.6%) firm quarters where securitizations are undertaken while the securitizing frequency in 2008–2009 when SFAS 140 applied is 72.7% of the total firm quarters in this period (in which the residual assets were measured using Level 3 inputs). In fact, there is little change in the proportion of firm quarters with securitizations over the entire sample period with a securitizing frequency in the SFAS 166 period of 75.3% of the firm-quarters. However, the volume of non-agency securitizations declined dramatically from 2002 to 2007 that featured a US$5,696.9 billion volume of issues compared to the ensuing period, 2008 to 2013, for which the volume was US$275.7 billion, comprising one twentieth (4.84%) of the prior period. 9

The sample also includes 1,055 (18.6%) firm quarters of reported losses with a greater incidence in the period when SFAS 140 (32.0%) applied compared to the SFAS 166 period (13.0%). The mean market to book ratio is also lower in the SFAS 140 period (0.94) compared to the SFAS 166 period (1.06).

Table 2 highlights some differences in the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 firm quarters. The Level 3 input assets declined significantly from the SFAS 140 period to the SFAS 166 period. Concurrently, Level 2 input assets increased significantly. These findings reflect the effects of the SFAS 166 amendments in changing the retained interests of the transferors from the highest risk securities to holdings that are proportionally representative of the securitized assets, so that the residual assets qualify for Level 2 input measurement.

| Firm-quarters where the firm has undertaken asset securitization over the period 1 January 2008 to 30 September 2014 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |||||||||

| SFAS 140 | SFAS 166 | SFAS 140 | SFAS 166 | T-test | P-value | Man-Whitney | P-value | |||

| FVAssets/TAit | 16.70% | 19.70% | 15.80% | 18.00% | 53.46 | 0.00 | *** | 9.077 | 0.00 | *** |

| FVA1/TAit | 1.20% | 0.60% | 0.10% | 0.10% | 13.74 | 0.00 | *** | –5.119 | 0.00 | *** |

| FVA2/TAit | 14.80% | 18.70% | 14.20% | 17.20% | 108.99 | 0.00 | *** | 12.467 | 0.00 | *** |

| FVA3/TAit | 0.70% | 0.30% | 0.10% | 0.00% | 9.16 | 0.00 | *** | –5.506 | 0.00 | *** |

| FVL/TLit | 0.60% | 0.80% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 12.25 | 0.00 | *** | 1.814 | 0.07 | * |

| LoanSales/Loansit | 5.00% | 6.40% | 2.10% | 2.90% | 33.83 | 0.00 | *** | 6.945 | 0.00 | *** |

- FVAssetsit are financial assets accounted for under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TAit are total assets for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it are assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it are assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it are assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVLit are financial liabilities accounted for under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit are total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; and LOANSALESit are the amount of closed-end 1–4 family mortgage loans sold in quarter t for firm i and comprises separate variables for the current quarter and the preceding 3 quarters (Qtr t–1, t–2, t–3).

| Panel A: Periods where SFAS 140 was applicable (1,667 firm-quarters) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pit | NFVAit | FVA1it | FVA2it | FVA3it | TLit | NIit | LoanSales | |

| Pit | 0.378 | 0.187 | 0.507 | 0.105 | 0.442 | 0.791 | 0.284 | |

| NFVAit | 0.424 | 0.146 | 0.428 | 0.148 | 0.953 | 0.211 | 0.732 | |

| FVA1it | 0.177 | 0.067 | 0.081 | 0.201 | 0.180 | 0.099 | 0.042 | |

| FVA2it | 0.468 | 0.479 | 0.007 | 0.272 | 0.612 | 0.396 | 0.281 | |

| FVA3it | 0.194 | 0.381 | 0.065 | 0.380 | 0.199 | 0.025 | –0.020 | |

| TLit | 0.478 | 0.962 | 0.123 | 0.689 | 0.447 | 0.285 | 0.696 | |

| NIit | 0.393 | –0.009 | 0.027 | 0.094 | –0.095 | 0.007 | 0.174 | |

| LOANSALES | 0.256 | 0.697 | 0.019 | 0.318 | 0.153 | 0.666 | 0.015 | |

| Panel B: Periods where SFAS 166 was applicable (4,005 firm-quarters) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pit | NFVAit | FVA1it | FVA2it | FVA3it | TLit | NIit | LoanSales | |

| Pit | 0.550 | 0.272 | 0.439 | 0.179 | 0.554 | 0.763 | 0.325 | |

| NFVAit | 0.595 | 0.153 | 0.580 | 0.136 | 0.958 | 0.611 | 0.860 | |

| FVA1it | 0.258 | 0.136 | 0.119 | 0.244 | 0.182 | 0.225 | –0.002 | |

| FVA2it | 0.430 | 0.501 | 0.271 | 0.163 | 0.743 | 0.549 | 0.478 | |

| FVA3it | 0.215 | 0.213 | 0.194 | 0.340 | 0.178 | 0.156 | 0.022 | |

| TLit | 0.600 | 0.952 | 0.230 | 0.736 | 0.295 | 0.631 | 0.817 | |

| NIit | 0.485 | 0.305 | 0.123 | 0.311 | 0.131 | 0.325 | 0.415 | |

| LOANSALES | 0.312 | 0.839 | 0.008 | 0.383 | 0.036 | 0.789 | 0.163 | |

- Correlation matrices for variables used in this study are presented separately for the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 periods, respectively. Pearson correlations are reported above the diagonal and Spearman correlations are below the diagonal. The bolded correlation statistics are significant at 5% level of significance or less.

- Bolded values indicate significance at the 1% level for two-tailed tests. Pit equals closing share price for firm i for quarter t measured on the trading day following the Federal Reserve Bank's 40 calendar day deadline for consolidated financial filing (after quarter end); NFVAit are assets that do not require fair value measurement for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it are assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it are assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it are assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit are total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; and LOANSALESit is the amount of closed-end 1–4 family mortgage loans sold in quarter t for firm i.

Table 3 presents Pearson and Spearman correlations. The correlations embed two clusters of collinearity effects relating first to the specific structure of bank balance sheets and second to securitizations. First, the bank structure of high leverage, capital adequacy requirements, and hence high non-financial asset proportion, and low equity, gives rise to high correlations between the non-financial assets and total liabilities. This collinearity is not troubling econometrically in the current context because tests are not conducted for non-financial assets and the total liabilities. For the tests we do conduct, this collinearity would bias down the T-statistics and hence bias against finding a result. Second, the securitization transactions give rise to a cluster of collinearities in the data. For example in the SFAS 140 period, LOANSALES is significantly correlated with total liabilities, non-financial assets, and Levels 2 and 3 financial assets (TL, NFVA, FVA2, FVA3), but not the Level 1 assets or net income (FVA1, NI). However in the SFAS 166 period, LOANSALES is significantly correlated with the total liabilities, non-financial, and Level 2 financial assets, and net income (TL, NFVA, FVA2, NI), but not the Level 1 or Level 3 financial assets. Securitizations are the source of these relations. Net income is less directly linked to LOANSALES in the SFAS 140 period because core income for securitizers tends to come from securitization sales and not loans directly, and hence we do observe a LOANSALES to NI correlation. Conversely in the SFAS 166 period, the non-agency securitizations have all but ceased and securitization securities are guaranteed by the regulated insurers (e.g., Fannie Mae). Accordingly, the risk attending loan sales and securitizations is arguably lower and the quality of the tranches is more transparent while the residual assets are now measured using primarily Level 2 inputs. Accordingly, LOANSALES is now more aligned to net income but no longer associated with the Level 3 financial assets. The effect of these correlations on tests conducted in relation to the fair value financial assets is to bias the T-statistics down and adversely impact our ability to observe a result.

Results

Hypothesis 1 Results for the Full Sample (n = 5, 672 firm quarters)

We begin with tests of Hypothesis 1 for the full sample from 2008–2014 comprising securitizers and non-securitizers and covering the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 periods. In keeping with the general sample of banks and the SFAS 157 uncertainty hierarchy, Hypothesis 1 predicts that the Level 1, 2, and 3 financial assets measured using fair value measurement under SFAS 157 are value relevant with the highest measurement uncertainty and lowest value relevance for the financial assets measured with Level 3 inputs.

Table 4 presents the results from equation 1. We first consider the results for the equation estimated without income (NI) in the first two columns of the results. Consistent with the measurement uncertainty hierarchy built into SFAS 157, the coefficients on fair value assets measured with Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are decreasing in size (1.203, 0.927, and 0.544). Wald tests suggest the coefficient on assets measured with Level 3 inputs is significantly less than one, and is significantly less than the estimated coefficients on the assets measured with Level 1 inputs. The coefficients on the assets not at fair value (NFVA) and the total liabilities (TL) have signs and significances broadly consistent with expectations taking into account the large leverage of banks, low equity, and capital adequacy requirements impacting the holding of ‘not at fair value’ assets (NFVA).

| Analysis based on the full sample of firms for all firm-quarters from 1 January 2008 to 30 September 2014 including securitizers and non-securitizers and both the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 application periods (n = 5,672) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | ||

| INTERCEPT | 4.648 | 3.90*** | 3.410 | 3.04** | 5.000 | 4.24*** | |

| NFVA | 0.896 | 8.57*** | 0.730 | 6.88*** | 0.702 | 6.84*** | |

| FVA1 | + | 1.203 | 7.66*** | 1.018 | 6.69*** | 1.001 | 6.76*** |

| FVA2 | + | 0.927 | 8.77*** | 0.746 | 6.84*** | 0.711 | 6.73*** |

| FVA3 | + | 0.544 | 2.04* | 0.531 | 2.22* | 0.558 | 2.38* |

| TL | –0.907 | –7.93*** | –0.727 | –6.26*** | –0.695 | –6.18*** | |

| NI | 3.317 | 6.99*** | 2.535 | 5.51*** | |||

| QUARTER | –1.409 | –6.51*** | –0.612 | –2.99** | |||

| LOSS | –3.201 | –3.38*** | |||||

| FIRM FIXED EFFECTS | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.464 | 0.503 | 0.511 | ||||

| Coefficient Tests for Hypothesis 1 | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald test: FVA1 = 1 | 1.67 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = 1 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 5.45 | 0.03 | 7.48 | 0.00 | |

| Wald test: FVA3 = 1 | 2.92 | 0.09 | 3.84 | 0.51 | 3.53 | 0.06 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA2 | 5.18 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 6.61 | 0.01 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA3 | 5.11 | 0.02 | 3.39 | 0.06 | 2.85 | 0.09 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = FVA3 | 2.22 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

- Two tail probability reported with * p < .1, **p < .05, *** p < .01. Wald tests indicate whether the tested hypothesis can be rejected. Robust standard errors adjust for cluster effects arising from the same bank observations in separate quarters. A significant F-statistic indicates the null hypothesis of zero for the coefficient is rejected. Pit equals closing share price for firm i for quarter t; NFVAit is assets that do not require fair value measurement for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it is assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it is assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it is assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit is total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; LOSSit is a dummy variable coded one if firm i recorded a loss in quarter t and zero otherwise; and QUARTERit takes the value of one for the most recent past March, June, September, or December quarter and zero otherwise.

The full model results are reported in the last two columns of Table 4 including net income (NI), and the quarter (QUARTER) and loss (LOSS) variables. The coefficients on the financial assets measured using Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are again decreasing in size (1.001, 0.711, and 0.558) in keeping with the SFAS 157 measurement uncertainty hierarchy. According to the Wald tests, the coefficient estimates for the assets measured with Level 1 inputs are not different from one, while the assets measured using Level 2 and Level 3 inputs are significantly less than one and significantly less than the coefficient on the Level 1 assets. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 1 insofar as the financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are value relevant. However, in contrast to Song et al. (2010) there are no significant differences in the coefficient estimates for the assets measured using Level 2 and Level 3 inputs in this full sample test across the 2008–2014 period. This result is not consistent with the SFAS 157 uncertainty hierarchy and suggests other effects are in play, which is examined in the remaining analysis below.

Hypothesis 2a Results for the Non-Securitizer Sample (n = 1,442 firm quarters)

Table 5 reports the results for tests of Hypothesis 2a. Hypothesis 2a focuses on non-securitizers and predicts the assets measured using SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are value relevant but do not decline monotonically in value relevance as has been concluded in the literature due to the SFAS 157 hierarchy (Song et al., 2010) or financial market conditions (Goh et al., 2015). The objective of the test is to evaluate whether the SFAS 157 measurement uncertainty hierarchy result applies generally as a result of the accounting measurement model embedded in SFAS 157 or whether the type of assets arising from asset securitizations informs the implementation of SFAS 157. Accordingly, we limit our analysis based on equation 1 to firms not undertaking asset securitizations. We acknowledge the non-securitizing firms may have purchased assets arising from asset securitization and if so these financial assets would more likely be traded and therefore be subject to measurement using Level 2 inputs. A breakdown of purchased assets from securitizations is not available and this is thus a limitation of this study.

Equation 1 is first estimated without income (NI) for the non-securitizers and the results are reported in the first two columns of Table 5. The estimated coefficients for the fair value assets measured using the Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are no longer decreasing monotonically (1.138, 0.788, and 0.838), which decline would be expected if it is the accounting measurement model in SFAS 157 primarily informing the asset measures. When the full model is estimated as reported in the last two columns of Table 5, this pattern of Level 1, 2, and 3 input assets persists with the coefficient estimates no longer decreasing monotonically (0.986, 0.631, and 0.781). Consistent with Hypothesis 2a, all three financial asset measures are value relevant (FVA1, FVA2, FVA3). However, there is no evidence that assets measured using Level 3 inputs are less relevant compared to those assets measured using Level 1 and 2 inputs, as in the evidence reported by Song et al. (2010) and Goh et al. (2015). The Wald tests suggest the coefficients for the three financial asset measures are not statistically different from each other as would be expected if the dominant factor informing the measures were the SFAS 157 hierarchy. Hence, there is support for Hypothesis 2a. The findings so far therefore are suggestive that the Levels 1, 2, and 3 hierarchy of measurement uncertainty results reported in Table 4 are at least partly attributable to financial assets arising from asset securitizations rather than a first order effect attributable primarily to the type of measurement model built into SFAS 157.

| Analysis based on all firm-quarters from 31 January 2008 to 30 September 2014 including only non-securitizers and both the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 application periods (n = 1442) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | ||

| INTERCEPT | 2.080 | 1.02 | 1.523 | 0.78 | 3.050 | 1.50 | |

| NFVA | 0.740 | 3.27** | 0.612 | 2.78** | 0.598 | 2.91 | |

| FVA1 | + | 1.138 | 3.15** | 0.995 | 2.81** | 0.986 | 2.87** |

| FVA2 | + | 0.788 | 3.67*** | 0.651 | 3.12** | 0.631 | 3.22** |

| FVA3 | + | 0.834 | 2.12* | 0.757 | 2.00* | 0.781 | 2.12* |

| TL | –0.736 | –3.07** | –0.599 | –2.58* | –0.582 | –2.70** | |

| NI | 2.362 | 4.15*** | 1.454 | 3.02** | |||

| QUARTER | –0.858 | –2.22* | –0.434 | –1.21 | |||

| LOSS | –3.777 | –3.34** | |||||

| FIRM FIXED EFFECTS | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.526 | 0.544 | 0.554 | ||||

| Coefficient Tests for Hypothesis 2a | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald test: FVA1 = 1 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.96 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = 1 | 0.97 | 0.32 | 2.78 | 0.09 | 3.54 | 0.06 | |

| Wald test: FVA3 = 1 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.55 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA2 | 1.70 | 0.20 | 1.68 | 0.20 | 1.18 | 0.18 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA3 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.21 | 6.45 | 0.16 | 0.69 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = FVA3 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

- Two tail probability reported with * p < .1, **p < .05, *** p < .01. Wald tests indicate whether the tested hypothesis can be rejected. Robust standard errors adjust for cluster effects arising from the same bank observations in separate quarters. A significant F-statistic indicates the null hypothesis of zero for the coefficient is rejected. Pit equals closing share price for firm i for quarter t; NFVAit is assets that do not require fair value measurement for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it is assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it is assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it is assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit is total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; LOSSit is a dummy variable coded one if firm i recorded a loss in quarter t and zero otherwise; and QUARTERit takes the value of one for the most recent past March, June, September, or December quarter and zero otherwise.

Hypotheses 2b and 2c Results for the SFAS 140 and SFAS 166 Subsamples (n = 1,667 and 4,005 firm quarters respectively)

Two features built into the 2008–2014 sample period are first, that is, the securitizations up to 2009 were opaque transactions involving a large volume of non-agency securitizations, for which the underlying loans did not meet regulatory requirements for guarantees (e.g., by Fannie Mae), and therefore had to be implicitly guaranteed by the originating banks (Ryan, 2008). Second, the securitizations after 2009 took place in a different environment in which the excessive risk taking and poor lending standards of the previous years were now exposed and non-agency securitizations had come to a virtual standstill with any new securitizations more than likely now eligible for the institutional guarantee. We exploit these different periods to examine the impact of securitizations on measurement uncertainty and value relevance. Equation 2 is estimated for the subsample of bank quarters for which SFAS 140 was applicable (i.e., 2008–2009), including variables proxying for attributes of the securitization transactions. We next repeat this analysis for the subsample of bank quarters in the SFAS 166 period (i.e., 2010–2014).

Table 6 reports the estimates from equation 2 for the SFAS 140 subsample. When equation 2 is estimated without net income (NI) or the variables capturing effects coming from the asset securitizations (first two columns), the coefficient estimates for the fair value assets measured with Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs exhibit a decreasing pattern (1.166, 1.036, and 0.391) consistent with the SFAS 157 measurement uncertainty hierarchy. In addition, Wald tests indicate the coefficient for the assets measured with Level 3 inputs is significantly less than one, and significantly less than the coefficient on assets measured with Level 1 and Level 2 inputs. At first glance, this result is consistent with Song et al. (2010) and the effects of the measurement uncertainty hierarchy in SFAS 157. However, these results from equation 2 are the mean effects for securitizers and non-securitizers.

| Analysis based on securitizers and non-securitizers for the SFAS 140 (2008–2009 financial crisis) application period (n = 1,667) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | ||

| INTERCEPT | 6.147 | 4.26*** | 7.748 | 5.61*** | 5.888 | 3.90*** | |

| NFVA | 0.865 | 5.45*** | 0.658 | 4.48*** | 0.677 | 4.56*** | |

| FVA1 | + | 1.166 | 6.09*** | 0.911 | 5.03*** | 0.918 | 5.08*** |

| FVA2 | + | 1.036 | 6.37*** | 0.775 | 4.99*** | 0.791 | 5.07*** |

| FVA3 | + | 0.391 | 1.32 | 0.468 | 2.00* | 0.801 | 2.75** |

| TL | –0.903 | –5.16*** | –0.672 | –4.09*** | –0.690 | –4.17*** | |

| NI | 1.448 | 5.51*** | 0.193 | 0.57 | |||

| QUARTER | –1.525 | –9.03*** | –0.812 | –5.64*** | –0.859 | –5.62*** | |

| LOSS | –6.889 | –9.67*** | –7.005 | –9.79*** | |||

| SECURITIZER | 2.918 | 2.82** | |||||

| SECURITIZER*FVA3 | – | –0.394 | –1.35 | ||||

| SECURITIZER*NI | 1.627 | 3.44*** | |||||

| LOANSALES | –0.223 | –2.64** | |||||

| FIRM FIXED EFFECTS | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.415 | 0.525 | 0.540 | ||||

| Coefficient Tests for Hypothesis 2b | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald test: FVA1 = 1 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.65 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = 1 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 2.10 | 0.14 | 1.79 | 0.18 | |

| Wald test: FVA3 = 1 | 4.23 | 0.04 | 5.16 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.49 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA2 | 1.76 | 0.19 | 2.66 | 0.10 | 2.31 | 0.13 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA3 | 8.52 | 0.00 | 4.62 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.66 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = FVA3 | 6.67 | 0.01 | 2.56 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.96 |

- Two tail probability reported with * p < .1, **p < .05, *** p < .01. Wald tests indicate whether the tested hypothesis can be rejected. Robust standard errors adjust for cluster effects arising from the same bank observations in separate quarters. A significant F-statistic indicates the null hypothesis of zero for the coefficient is rejected. Pit equals closing share price for firm i for quarter t; NFVAit is assets that do not require fair value measurement for firm i for quarter t; FVA1it is assets that require fair value measurement using quoted prices in active markets for identical assets under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA2it is assets that require fair value measurement using inputs other than quoted prices observable for the asset either directly or indirectly under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; FVA3it is assets that require fair value measurement using unobservable inputs under SFAS 157 for firm i for quarter t; TLit is total liabilities for firm i for quarter t; NIit is income before extraordinary items for firm i for quarter t; LOSSit is a dummy variable coded one if firm i recorded a loss in quarter t and zero otherwise; and QUARTERit takes the value of one for the most recent past March, June, September, or December quarter and zero otherwise; SECURITIZERit is a dummy variable coded one if the firm undertook asset securitization in the current quarter t for firm i and zero otherwise; LOANSALESit is the amount of closed-end 1–4 family mortgage loans sold in quarter t for firm i.

Accordingly, the last two columns of Table 6 report estimates from equation 2 now including variables capturing effects arising from the securitizations (SECURITIZER, SECURITIZER*FVA3, SECURITIZER*NI, LOANSALES). The results from this expanded equation show that the SFAS 157 measurement uncertainty hierarchical effects are no longer observed for FVA1, FVA2, FVA3. In particular, when the estimation includes the securitization related variables (SECURITIZER, SECURITIZER*FVA3, SECURITIZER*NI), the coefficients for the fair value assets measured using Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs FVA1, FVA2, FVA3 are value relevant but are no longer decreasing monotonically (0.918, 0.791, and 0.801). Moreover, the Wald statistics suggest the coefficients of the three variables are not statistically different from one or from each other.

However, the coefficient on the interaction between securitizer and the assets measured with Level 3 inputs (SECURITIZER*FVA3) is negative as predicted but is not significant, notwithstanding the magnitude of the coefficient suggesting the measurement error is so large that investors find the number is uninformative. This result is intuitive given the opacity of the securitizations in the SFAS 140 period, and the fact that the Level 3 assets were associated with the riskiest tranche of securities, and an unrecorded (potentially large) liability relating to implicit guarantees to make good any losses on the underlying loans.

Hence, the results provide support for Hypothesis 2b. The assets measured using Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are value relevant, and the Level 3 input assets are less value relevant for the securitizers compared to the non-securitizers. There are also other effects of asset securitization transactions and associated accounting under SFAS 140 evident in Table 6. First, the coefficient on loan sales is negative and significant suggesting investors place higher value relevance on the banks reporting lower loan sales in the last four quarters. This result likely reflects investors’ awareness of the securitizers’ unrecognized obligations arising from implicit recourse to ‘absorb losses up to the full amount of transferred assets’ (Niu and Richardson, 2006, p. 1108). The loan sales are also mechanically correlated with the Level 3 financial assets in the SFAS 140 period (Table 3 Panel A: significant 0.153 Spearman correlation) (but are uncorrelated in the SFAS 166 period as the Level 3 assets shifted into the Level 2 input measurement). Second, the coefficient for the interaction between securitizer and net income (SECURITIZER*NI) is positive and significant. This result is an artefact of SFAS 140, which accounts for transfers of securitization securities as sales at the time of transfer despite the implicit recourse provided in respect of the transferred securities. This sales accounting and risk-based stratification of the securities under SFAS 140 came at a time of soaring non-agency securitizations subject to considerable (and opaque) credit risk, and likely disrupted the link between the loan sales and net income. For example, the Spearman's correlations in Table 3 show loan sales are not correlated with net income (insignificant Spearman coefficient of 0.015) in the SFAS 140 period but are positively correlated in the SFAS 166 period (significant Spearman coefficient of 0.163). 4

Table 7 reports the estimates for tests of Hypothesis 2c from equation 3. Hypothesis 2c predicts that in the period when SFAS 166 was applicable, financial assets measured using the SFAS 157 Level 1, 2, and 3 hierarchy are value relevant with the highest measurement uncertainty and lowest value relevance for the Level 2 and Level 3 input assets of securitizing firms compared to non-securitizing firms. The initial intuition for Hypothesis 2c is that the changed rules for sales accounting for transferred securities, and the move away from risk-stratified retained interests in the pool of securities to retained interests that are a proportional representation of the securities, addressed securitization accounting issues. The effect of this SFAS 166 change in securitization accounting is that many financial assets from securitization are now measured using Level 2 inputs rather than Level 3 inputs. However, against this intuition is the fact that disclosures relating to securitization did not improve after SFAS 166, which we discovered when collecting data for the empirical tests. Further, liquidity assets and securitization assets are now mixed together in undisclosed proportions in the Level 2 category. Coming on the back of the financial crisis excesses, Hypothesis 2c makes a prediction informed by the intuition that SFAS 166 was not able to address securitization accounting problems.

Looking now at the results, the first two columns of Table 7 include estimates without net income. The coefficients for the fair value assets measured using Level 1, 2, and 3 inputs are decreasing (1.343, 0.906, and 0.672) consistent with the SFAS 157 hierarchical measurement model. However, this latter test is an average result across both non-securitizers and securitizers. Again, this result is consistent with the results reported above for the first two columns of Table 6 for tests of Hypothesis 2b and Song et al. (2010). However, once again this result is not observed once the securitization variables are included in the estimation of equation 3.

| Analysis based on securitizers and non-securitizers for the SFAS 166 (post financial crisis) application period (n = 4,005) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | Coeff. | T-stat. and Prob. | ||

| INTERCEPT | –1.111 | –0.45 | –2.401 | –0.97 | –2.810 | –0.86 | |

| NFVA | 0.923 | 6.78*** | 0.708 | 4.87*** | 0.720 | 5.05*** | |

| FVA1 | + | 1.343 | 5.32*** | 1.123 | 4.55*** | 1.150 | 4.81*** |

| FVA2 | + | 0.907 | 6.43*** | 0.676 | 4.44*** | 0.699 | 4.85*** |

| FVA3 | + | 0.672 | 1.91 | 0.543 | 1.54 | 1.070 | 2.23* |

| TL | –0.924 | –6.16*** | –0.693 | –4.33*** | –0.702 | –4.48*** | |

| NI | 4.469 | 4.12*** | 3.806 | 2.22* | |||

| QUARTER | 3.934 | 1.95 | 5.788 | 2.97** | 3.902 | 1.22 | |

| LOSS | 0.504 | 0.31 | 0.535 | 0.33 | |||

| SECURITIZER | 3.351 | 2.42* | |||||

| SECURITIZER*FVA2 | – | –0.036 | –0.78 | ||||

| SECURITIZER*FVA3 | – | –1.014 | –1.62 | ||||

| SECURITIZER*NI | 0.819 | 0.44 | |||||

| LOANSALES | –1.129 | –2.04* | |||||

| FIRM FIXED EFFECTS | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.54 | ||||

| Coefficient Tests for Hypothesis 2c | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald test: FVA1 = 1 | 1.85 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.53 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = 1 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 4.52 | 0.03 | 4.34 | 0.03 | |

| Wald test: FVA3 = 1 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 1.68 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.88 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA2 | 4.05 | 0.05 | 4.76 | 0.03 | 5.26 | 0.02 | |

| Wald test: FVA1 = FVA3 | 2.27 | 0.13 | 1.68 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.88 | |

| Wald test: FVA2 = FVA3 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.46 |