Does Integrated Reporting Matter to the Capital Market?

Abstract

Integrated reporting (<IR>) is an emerging international corporate reporting initiative to address limitations to extant corporate reporting approaches, which are commonly criticized for being both voluminous and disjointed. While <IR> is gaining in popularity, current momentum has been limited due to a lack of clear evidence of its benefits. Utilizing the most suitable setting currently available, being discretionary disclosures made by listed companies on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, this study provides evidence that analyst forecast error reduces as a company's level of alignment with the <IR> framework increases. Further, the improved alignment is associated with a subsequent reduction in the cost of equity capital for certain reporting companies. The results are obtained after controlling for factors relating to financial transparency and the issuance of standalone non-financial reports, which suggests that <IR> is providing incrementally useful information to the capital market over and above existing reporting mechanisms.

Businesses, investors, capital markets, and the broader economy all depend upon the provision of high-quality, value-relevant information from companies to ensure the efficient and effective allocation of resources, to encourage a vibrant climate for investment, and to facilitate transparent, ethical, and sustainable business practices. While there have been a number of attempts by individuals and groups to expand or enhance the value-relevance of the information produced by companies to aid decision-making, a recent initiative called Integrated Reporting (<IR>) has the potential to change the landscape of corporate reporting.

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), which is a ‘global coalition of regulators, investors, companies, standard setters, the accounting profession and NGOs’ (IIRC, 2013), has played a pivotal role in raising the international profile of, and developing a global framework for, <IR>. The aim of an integrated report is to provide a concise, holistic account of company value and performance by reporting a comprehensive range of financial as well as human, intellectual, environmental, and social factors that impact on a company's short-, medium-, and long-term capacity for value creation. As such, it incorporates but goes beyond the types of information currently reported in companies' financial statements (IIRC, 2013).

Organizations have increasingly utilized mechanisms beyond financial statements to satisfy increased stakeholder demands for information about their organizations, the chief conduit for which has been standalone sustainability reports (Simnett et al., 2009; Cohen et al., 2012). While the practice of issuing standalone sustainability reports is now a mainstream business practice (KPMG, 2013), one of the major criticisms of this practice is the sheer volume of information produced, often without identification of strategic or financial implications or relation to information contained in the Annual Report, which has rendered it of little use to information users, especially providers of financial capital (Eccles and Krzus, 2010; Eccles and Serafeim, 2014).

One aim of <IR> is to reduce the clutter of current corporate reporting by promoting conciseness. <IR> claims to do this by having a different materiality lens whereby directors disclose what they consider to be material to the value-creating activities of the organization. A further claimed benefit of <IR> is that it combines the most material elements from an organization's separate reporting strands into a concise, coherent report. In so doing, it not only reports the most strategically relevant information, which is important for investors' investment decisions (Cheng et al., 2015), but also shows the connectivity between these elements and explains how they affect the ability of an organization to create and sustain value in the short, medium and long term (IIRC, 2013a), addressing the potential short-termism of current reporting practice. 1

<IR> has gained significant momentum since the establishment of the IIRC in 2011, culminating in the release of the <IR> framework in December 2013 (IIRC, 2013a). The significance of <IR> is further evidenced by the increased interest in the IIRC Pilot Programmes 2 as well as an increasing number of regulatory initiatives around the world that are consistent with the principles of <IR>. 3 Anecdotal and survey evidence indicates that <IR> brings internal benefits to a company in the form of accelerating integrated thinking within organizations, which leads to better management decision-making (IIRC and Blacksun, 2014). This new type of reporting is aimed at ‘providers of financial capital’ as its primary audience (IIRC, 2013a). If the <IR> reporting initiative is indeed helpful to such providers in assessing the prospects of companies, it is expected that some capital market benefits will accrue to the reporting companies such as enhanced reputation and increased transparency, which could result in a lower cost of capital (IIRC, 2011; IRCSA, 2011; PwC, 2014).

However, empirical evidence substantiating the benefits of <IR> remains sparse. Therefore, this study aims to provide empirical evidence to answer the question ‘Does <IR> matter to the capital market?’ In doing so, it first examines whether information contained in integrated reports is useful to sophisticated capital market participants such as analysts by examining the effect of companies producing integrated reports more aligned with the <IR> framework (referred to as higher integrated reports) on sell-side analysts' earnings forecast properties. The study then considers the potential flow-on effect of the improved information environment by examining whether companies producing higher quality integrated reports enjoy the benefit of a reduced implied cost of equity capital (ICC).

With their significant emphasis on the corporate governance environment, the South African JSE became a forerunner in the adoption of <IR> by being the first stock exchange globally to incorporate the move toward <IR> into its listing rules, under its King Code on Corporate Governance (JSE, 2015). However, it is worth noting that the concept of <IR> is mandated on an ‘apply or explain’ basis, and full alignment with the <IR> framework may well take companies a number of years (KPMG, 2012). In the early years of application, companies choosing to apply the concept have significant discretion as to what they disclose and how they disclose it. This discretion creates significant variations in the alignment of the integrated reports with the <IR> framework, and therefore the quality of the integrated reports produced by the South African companies. For example, as a first step toward integration, some companies simply stapled their Corporate and Social Responsibility (CSR) reports with their Annual Reports (a combined report, rather than an integrated report) while others have gone much further in adopting the <IR> framework to communicate the strategic intentions, the business model, the risks and opportunities faced by the company, and how these factors interact with each other to affect the value-creation ability of the company. As a result, although all of the various reports are titled ‘Integrated Reports’, the level of alignment with the <IR> framework differs significantly across companies.

In addition, the <IR> framework is principles-based in order to strike an appropriate balance between flexibility and prescription that recognizes the wide variation in individual circumstances of different organizations while enabling a sufficient degree of comparability across organizations to meet relevant information needs (IIRC, 2013a). It is recognized within the <IR> framework that those responsible for the preparation and presentation of the integrated report need to exercise judgement, given the specific circumstances of the organization to determine which matters are material and how they are best disclosed (IIRC, 2013a). It is therefore the difference in the level of alignment arising from managements' discretion, and changes in alignment within a company over the years, that this study is capturing to test whether it makes a difference to the capital market.

Nonetheless, the South African experience in adopting the International <IR> framework 4 presents the most suitable setting to examine our research questions because (i) it is the only exchange that has embraced and encouraged <IR> over a period of time which thus allows changes and any associated impacts in the reporting quality to be observed, (ii) it is the only exchange where listed companies have the explicit goal to align with the <IR> framework, and (iii) the announcement to incorporate the move towards <IR> into the listing rules in South Africa presents an exogenous shock to companies, thereby offering a natural experiment setting which is particularly beneficial in reducing the potential endogeneity bias usually present in studies examining the economic consequences of voluntary disclosures (Gipple et al., 2015). To further address potential endogeneity concerns, additional measures, including the lead–lag approach, the changes specification, and Heckman's two-stage analysis are also employed in the study.

Using a sample of 443 company-year observations listed on the JSE from 2009 to 2012, we find that the level of alignment of an integrated report with the <IR> framework is negatively associated with analyst earnings forecast error and weakly negatively associated with analyst earnings forecast dispersion, suggesting that information contained in an integrated report is useful for analysts in assessing the future financial performance of companies. Further, we identify a negative relationship between the level of alignment of integrated reports with the framework and both the ICC and the realized market returns, which is consistent with previous studies (Jones et al., 2007; Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009) and the proposition that investors are willing to accept a lower rate of return as a result of reduced information risk from the improved information environment for these companies. Sub-sample analysis suggests that the benefit of ICC reduction is more evident among companies with a low analyst following, since the benefit is expected to be less significant for those with better information environments, that is, those companies with a larger analyst following (Botosan, 1997; Griffin and Sun, 2014; Merton, 1987).

The results from this study are obtained after the company-level characteristics relating to financial transparency and the issuance of standalone CSR reports are controlled for, suggesting that information contained in an integrated report is incrementally useful to analysts and investors in addition to current reporting practices. This is further evidenced from the results of additional analyses that indicate that it is mainly those components containing new information in an integrated report that are driving the results identified. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the quality of integrated reports matters to capital market participants. Specifically, integrated reports with a higher level of alignment with the <IR> framework bring the benefit of an improved information environment for reporting companies, evidenced by improved analyst forecast accuracy. This improved information environment in turn brings the benefit of a lower ICC to reporting companies.

This paper has several contributions. First, there has been debate on whether <IR> has real benefits or is just a passing fad. By documenting empirical evidence on whether <IR> is value-enhancing to reporting companies, this study assists in moving the debate forward and provides incentives for the voluntary adoption of <IR>. Second, <IR> is increasingly on the agenda of regulators around the world (IIRC, 2014a). At the international level, support for <IR> has been received from influential corporate forums such as the B20 (B20, 2014) and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). At the national level, many countries are revising their corporate reporting regulations in a manner consistent with the principles of <IR>. 5 The results from the current study are therefore expected to have practical regulatory implications. In particular, the experience and lessons from companies listed on the JSE can provide valuable guidance for regulators in other jurisdictions about the costs and benefits of adopting <IR>. Finally, this study extends the testing of voluntary disclosure theory which to date is limited to either only financial information (Beyer et al., 2010; Healy and Palepu, 2001) or only non-financial information (Dhaliwal et al., 2011, 2012, 2013) into a new and distinctive realm of voluntary corporate reporting, one that goes beyond current corporate reporting practices and which may become the norm for corporate reporting in the near future (IIRC, 2013a).

Theory and Literature Review

Information Quality and Analysts' Earnings Forecasts

As outlined above, this study examines whether the different levels of alignment with the <IR> framework in companies' integrated reports arising from managements' disclosure discretions matters to the capital market. Owing to the discretionary nature of the disclosures at this early stage of the journey, we employ voluntary disclosure theory in developing our hypothesis.

Voluntary disclosure theory asserts that voluntary disclosures help to improve the information environment of companies by enhancing analysts' understanding of companies' prospects (e.g., Beyer et al., 2010). Following the theory, empirical studies generally document a positive relationship between disclosure quality and analysts' earnings forecasting properties, such as lower forecast error and dispersion (Barron et al., 1999; Barth et al., 2001; Bradshaw et al., 2008; Hope, 2003; Lang and Lundholm, 1993; Plumlee, 2003). The general argument from these studies is that better disclosure quality enhances analysts' understanding of the company's performance and future outlook and helps analysts interpret the disclosures in an informed and similar manner, which in turn results in an improved forecast accuracy and a lower forecast dispersion (Hope, 2003; Lang and Lundholm, 1996). Moreover, better disclosures lower the costs of processing and interpreting the disclosures, and thus enhance analysts' ability to correctly incorporate all pertinent information, which in turn results in improved earnings forecasts (Lehavy et al., 2011).

Evidence from prior literature also reveals that analysts use non-financial information in their earnings forecasting (Dhaliwal et al., 2012; Nichols and Wieland, 2009; Orens and Lybaert, 2007; Simpson, 2010). The supply of non-financial information is beneficial in reducing analyst earnings forecast error and dispersion (Dhaliwal et al., 2011, 2012; Nichols and Wieland, 2009) and analysts issue more optimistic recommendations for companies with higher CSR ratings (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2015). In fact, considerable evidence shows that analysts use financial information and non-financial information interactively in their earnings forecasting (Coram et al., 2011; García-Meca and Martinez, 2007; Ghosh and Wu, 2012; Maines et al., 2002; Orens and Lybaert, 2010; Pflugrath et al., 2011; Simpson, 2010). This means that both types of information are integral to analysts' earnings forecasting.

Theoretically, the ability of analysts to forecast earnings should improve with the amount of disclosure (regardless of whether disclosures are financial or non-financial) as long as they help analysts to assess companies' future performance. However, analysts are known to have cognitive limitations in information processing and the complexity of the task is found to adversely affect analyst earnings forecast error and dispersion. For example, analysts' forecasts have been found to be less accurate if they are associated with complex changes to tax laws (Plumlee, 2003), and more complex accounting choices can negatively affect forecast accuracy and increase dispersion (Bradshaw et al., 2008). Further, although analysts exert extra effort in generating reports when analyzing companies that produce less readable 10-K filings, these less readable 10-Ks are still associated with greater dispersion, lower accuracy, and greater overall uncertainty in analyst earnings forecasts (Lehavy et al., 2011).

Thus, if such problems exist for analysts relying on complex financial information, then adding non-financial information into their decision-making processes could exacerbate the adverse effects. This is especially the case when the correlation between non-financial information and financial information is not well articulated, which adds significantly to the total task complexity and thus the issue of ‘overload’ for analysts. Empirical evidence shows that analysts tend to underreact to information in non-financial measures (e.g., customer acquisition cost, average revenue per user) even though those measures can have significant predictive ability for future earnings (Rajgopal et al., 2003; Simpson, 2010).

Furthermore, the relevance of the information format has also been well documented in psychology and accounting studies, revealing that the way information is systematically presented affects the way people think about that information. Informationally equivalent disclosures that vary only in their ease of processing can have differential effects on market prices (Hopkins, 1996; Hodge, 2001; Hodge et al., 2006; Kelton et al., 2010; Koonce and Mercer, 2005). The insights from these studies suggest that even if <IR> is simply an improved re-formatting of information currently required, it could still beneficially impact upon users' information processing, including sophisticated users like financial analysts. By incorporating material non-financial information with financial information into one report, <IR> can increase the salience of those material non-financial information items, which users may ignore if they are reported separately (Agnew and Szykman, 2005; Hirshleifer and Teoh, 2003).

To summarize, disclosure theories and associated empirical evidence demonstrate that both financial and non-financial information have the potential to improve analysts' forecasting abilities if they are value-relevant and/or they help to reduce information acquisition and processing costs. Studies using psychology theories suggest that analysts' earnings forecasting abilities could be hindered by voluminous reporting and by their failure to fully incorporate non-financial information into their decision making.

Information Quality and the Cost of Equity Capital

Theoretical studies have established both direct and indirect links through which financial information can affect the cost of equity capital. The direct links include risk sharing (Merton, 1987) and the reduction of estimation/information risk (Barry and Brown, 1984, 1985; Brown, 1979; Coles et al., 1995). This line of research suggests that providing better information will reduce the estimation risk and therefore the cost of capital. The indirect links include the effect on market liquidity and information asymmetry (Baiman and Verrecchia, 1996; Diamond and Verrecchia, 1991; Easley and O'Hara, 2004; Verrecchia, 2001) and the effect on companies' real decisions (Lambert et al., 2007).

Despite theoretical conjecture on the negative link between discretionary disclosures and the cost of equity capital, the empirical evidence on the link is less consistent and robust for a definitive and unambiguous conclusion to be drawn (Beyer et al., 2010; Botosan, 2006; Core, 2001; Healy and Palepu, 2001; Kothari, 2001; Leuz and Wysocki, 2008). However, overall, the empirical studies generally provide support for the theoretical negative link between the level/quality of discretionary disclosures and the cost of equity capital, although the results appear to be sensitive to many factors such as the presence of market intermediaries (Botosan, 1997; Griffin and Sun, 2014), the types and frequency of disclosures (Botosan and Plumlee, 2002; Kothari et al., 2009), missing control variables such as earnings quality (Francis et al., 2008), and countries' institutional factors (Chen et al., 2009; Francis et al., 2005; Hail and Leuz, 2006, 2009).

With the increasing trend of supplementing financial information disclosure with non-financial information disclosure, research has extended voluntary disclosure theory to non-financial information, with the assumption that this non-financial information is value-relevant (Margolis et al., 2009; Margolis and Walsh, 2003; Orlitzky et al., 2003). Following this line of thought, a number of studies have examined the impact of CSR disclosures/performance on the cost of equity capital and have generally documented a negative relationship 6 (Dhaliwal et al., 2011, 2013; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Plumlee et al., 2015). While these recent studies on CSR disclosures/performance yield useful insights into how non-financial information affects investor behaviour, they suffer from some limitations. First, these studies generally examine the issuance status of the CSR report (issued or not issued) without further distinguishing between the difference in the quality of those reports. Second, while the issuance of a CSR report signals progress toward expanding current corporate reporting to include environmental, social, and governance issues, there are criticisms that these reports are not easily related to a company's strategy and business model, and are thereby less effective in communicating the company's performance to investors (Eccles and Krzus, 2010; Serafeim, 2014).

Despite ample evidence suggesting an interconnected relationship between non-financial information and financial information, most existing research examines them in isolation. Indeed, this propensity reflects the current bifurcated state of corporate reporting. The concept of <IR> aims to advance and enhance corporate reporting by placing emphasis on the interconnections between different types of information currently reported in separate strands. <IR> is still an emerging phenomenon so therefore empirical research about it is both recent and sparse. Among the limited empirical studies on <IR>, Serafeim (2014) provides evidence on the value of this form of reporting by examining the investor base of companies that practice <IR>. Using the data on Thompson Reuters Asset4 database to proxy for <IR>, Serafeim notes an association between <IR> and the investor clientele in terms of the investment horizon, but he also notes that it is not clear how investors change capital allocation decisions based on the information within integrated reports. Furthermore, as the data from the Asset4 database do not provide links to the content elements of integrated reports, Serafeim is not able to determine which elements of <IR> are most effective in attracting long-term investors.

Our study advances the literature by examining two direct outcomes of user decisions, that is, the impact on analysts' earnings forecasting tasks and the change in reporting companies' cost of equity capital. Further, examining the level of alignment of companies' integrated reports with the <IR> framework allows for a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between the disclosure quality of the integrated report and the associated economic outcomes.

Hypothesis Development

<IR> and Analyst Earnings Forecast Accuracy and Dispersion

The preceding literature review suggests analysts' earnings forecasting ability could be improved in three ways: (i) by having new value-relevant information; (ii) by having better disclosed information, which reduces information acquisition costs, and/or a cognitive effect in processing and interpreting the information; and (iii) by having better presented information, which facilitates the incorporation of all relevant information into the user decision-making process.

<IR> places emphasis on narrating companies' value-creation stories during the short, medium, and long term by providing information relating to corporate strategy, business model, and future outlook (IIRC, 2013a). The long-term focus of <IR> corresponds well to the information demands of analysts with their long-term earnings forecasting horizon. In addition to current corporate reporting requirements, the integrated report can also provide new information, which is supported by the findings from an investor survey that was undertaken, and is described in the methodology section. Thus, the integrated report is expected to provide both new and useful information to analysts for their earnings forecasting tasks.

The principles of <IR> mean that it provides more than additional value-relevant information. In particular, the key underlying principles of <IR> are materiality, conciseness, and connectivity (IIRC, 2013a). The materiality principle helps to de-clutter the report by including only substantial matters affecting a company's value-creation ability. This in turn reduces the costs of information acquisition and processing, thereby relieving information overload faced by analysts. The conciseness principle stresses the need for cross-referencing between elements of the report and shifting detailed standard information to other platforms/documents. This helps to reduce the cognitive effort exerted by analysts in analyzing and interpreting the information. The connectivity principle means that the relationships among key elements included in the report are explicitly and clearly presented and articulated. This is not only useful in enhancing analysts' ability to incorporate all value-relevant information into their decision making, but also in easing analysts' information analyzing processes. In sum, the combined aim of these <IR> principles is to alleviate the information overload problem encountered by users by de-cluttering the report and highlighting the connections between different parts of the reports.

Accordingly, the integrated report not only potentially contains new value-relevant information which is helpful in assessing the long-term prospects of companies, but also information that is easier to process, thus enabling analysts to incorporate all pertinent information. In this way, analysts can have a better understanding of the company's performance and future outlook and thus make improved forecasts.

However, the effectiveness of <IR> is dependent on the quality of the integrated report, and more specifically on how well the prescribed <IR> principles are followed. In this sense, integrated reports that are more closely aligned with the <IR> principles are expected to be more helpful to analysts.

This discussion leads to the first set of hypotheses to be tested in this study:

H 1a.Companies producing integrated reports more aligned to the <IR> framework have lower analyst earnings forecast error.

Following on from the previous discussion, if the integrated report contains useful value-relevant information, which is easy to understand and interpret, the reduced level of ambiguity will enhance the consensus among analysts during their earnings forecasting tasks. This effect is hypothesized as follows:

H 1b.Companies producing integrated reports more aligned to the <IR> framework have lower analyst earnings forecast dispersion.

<IR> and the Cost of Equity Capital

- Signalling the quality of the company. <IR> requires a clear vision and commitment to sustainable value-creation activities and helps to identify risks and opportunities within the business. Thus, to report in an integrated manner signals to readers that sustainability is an integrated part of a company's daily business conduct and significant risks and opportunities are well managed.

- Expanding the information set of the company's disclosure. <IR> has the ability to expand the information set so as to include all value drivers of the company (e.g., financial, environmental, social, and human) into one report and to connect them to describe the value-creation activities. In this way, it not only saves users' information search costs and therefore helps increase liquidity, but more importantly creates new information content not necessarily captured in the current corporate reporting suite, such as corporate strategy, the company's business model, and future-oriented information. More importantly, it highlights the links among all these value drivers, which in turn reduces information asymmetry between the company and investors.

- Reducing uncertainty in assessing the company's performance. Many CFOs interviewed by Graham et al. (2005) revealed that reducing uncertainty about the company's prospects is the most important motivation for making voluntary disclosures. The principles of <IR> place emphasis on the disclosure of corporate strategy, the company's business model, and forward-looking information, with the aim of reducing the uncertainty around the company's long-term performance. Thus, if the principles of <IR> are followed, an integrated report could help reduce the uncertainty relating to the company's long-term performance and therefore the information risk of the company, resulting in a lower cost of equity capital.

Collectively, theoretical arguments support the notion that <IR> could help reduce the cost of equity capital if the principles of <IR> are adequately followed, which is formally hypothesized as follows:

H 2.Companies producing integrated reports more aligned to the <IR> framework have a lower cost of equity capital.

It is recognized that companies' annual reports are not the only avenue through which companies disseminate information to stakeholders. Companies use other channels such as websites, conference calls, management forecasts, and media to communicate with information users. Nonetheless, market intermediaries, such as analysts, play an important role in analyzing, processing, and disseminating information about companies. The theoretical model of risk sharing noted by Merton (1987) suggests that disclosures by lesser known companies can make investors aware of their existence and therefore enlarge their investor base, which in turn improves risk sharing and lowers the cost of capital. In this sense, such an effect is likely to be less relevant for large companies, which are likely to have advanced information-sharing mechanisms such as a larger analyst and investor following. Voluntary disclosure theory also posits that the benefit of additional disclosure depends on the company's information environment (Diamond and Verrecchia, 1991; Lambert et al., 2007; Verrecchia, 1983). This is particularly relevant to our study as the disclosures in annual reports may be more important for some companies than others.

This asymmetric effect has been identified empirically (e.g., Botosan, 1997; Griffin and Sun, 2014). Our study is similar to Botosan (1997) in that we use disclosure in annual reports as a proxy for companies' overall disclosure quality. Thus, the effect of <IR> on the cost of equity capital could differ between companies with different information environments. This is formally hypothesized as follows:

H 2a.The association between the level of alignment of the integrated report with the <IR> framework and the cost of equity capital is more significant for companies with a smaller analyst following.

Empirical Analysis

Sample and Data

The sample selection process started with all listed companies on the JSE with fiscal years ending in 2009 to 2012 that are also included on Global Compustat. This list of companies was then merged with corresponding analyst data from I/B/E/S. The annual fundamental data, market data, and exchange rate data were obtained from Global Compustat. All data were downloaded from Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS).

After filtering for analyst data and required control variables, the final sample consisted of 443 company-year observations over four years (132 unique companies) for analyst forecast error 7 and dispersion analysis and 430 company-year observations (130 unique companies) for cost of equity capital analysis.

Research Model

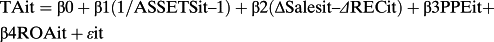

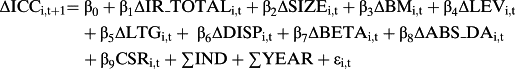

(1)

(1) (2)

(2)The models follow those used in Dhaliwal et al. (2012) with the addition of the issuance status of a standalone CSR report as a control variable, which was examined in Dhaliwal et al. (2012) and found to help reduce analyst forecast error. All variables are analyzed in their changes form 8 rather than levels form to address the potential endogeneity concern (Dhaliwal et al., 2011), as this approach controls for unobserved company characteristics (whether constant or time-variant) which might be correlated with analyst forecast properties. Further, to ensure that the results are not driven by the potential endogenous relation between changes in <IR> and ICC, all independent variables are lagged by one year.

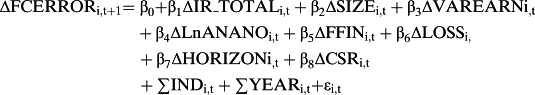

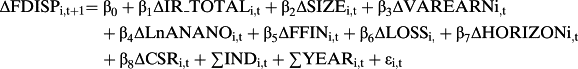

(3)

(3)Equation 3 is developed from Dhaliwal et al. (2011) and similarly, all variables are analyzed in their changes form and a lead–lag approach is used in the model to ameliorate endogeneity concerns. To test Hypothesis 2(a) on the role of the information environment in the relationship between <IR> and ICC, the sample companies are partitioned into high versus low analyst sub-samples based on the sample median number of analysts following the company. The regression in equation 3 is run separately for the two sub-samples.

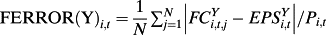

Variable Definition–Dependent Variables

Subscripts i, t, and j denote company i, year t, and forecast j, respectively. Indicator Y takes three values—zero, one and two—to denote whether the target earnings and forecasts are for current year, one-year ahead, or two-years ahead. 10 FC is the analyst earnings forecast for time t, and EPS is the actual earnings per share for time t. For consistency, both FC and EPS are obtained from the I/B/E/S database. The forecast horizon is restricted to a maximum of two years for the same reason noted in Dhaliwal et al. (2012): analysts typically do not make forecasts for periods beyond the third fiscal year. Further, as the sample period of this study is from 2009 to 2012, the sample size significantly decreases for three-year-ahead forecasts. Only forecasts made after the fiscal year-end month (1 to 12) 11 are used to allow analysts to incorporate the information contained in the integrated reports into their forecasts.

The natural logarithm of analyst forecast error (FERROR) is used in the regression to remove the skewness in the data as shown by the Skewness/Kurtosis tests, and the histogram suggests that the analyst forecast error is significantly right skewed. This approach is similar to that adopted in Lehavy et al. (2011).

Analyst forecast dispersion (FDISP)

Following Lang and Lundholm (1993), Hope (2003), and Lehavy et al. (2011), analyst forecast dispersion is defined as the standard deviation of analysts' EPS median forecasts scaled by the share price at the fiscal year-end. For the same reason noted for forecast error, only forecasts made after the fiscal year-end month (1 to 12) are used.

Implied Cost of Capital (ICC)

The ICC in this study is calculated in the first instance using the PEG model from Easton (2004), namely ICC_PEG. A number of different models are available to calculate the cost of equity capital, and there is still significant debate as to which are the best measures (Botosan and Plumlee, 2005; Easton and Monahan, 2005; Botosan and Plumlee, 2011). The PEG model is used in this study based on its popularity in previous studies due to parsimony and the finding that it tends to outperform other measures (Botosan and Plumlee, 2005). Regarding sensitivity tests, however, several other measures are employed to test the robustness of the results, including the GLS model developed from Gebhardt et al. (2001), the CT model developed from Claus and Thomas (2001), and the simultaneous estimation method developed from Easton et al. (2002). In addition, in view of the criticisms of the measurement errors associated with the ex-ante ICC, the ex-post realized market return is also used to substantiate the main results.

Independent Variable of Interest

The level of alignment of an integrated report with the <IR> framework (IR_TOTAL)

The independent variable of interest is the level of alignment of an integrated report with the <IR> framework (quality of <IR>). It is measured as the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL) derived from a coding framework constructed in accordance with the <IR> Prototype Framework 12 issued by the IIRC in October 2012. As mentioned previously, there are significant variations in the level of ‘integrativeness’ of reports produced by JSE companies, which necessitates the development of proper measures to capture the variations among these reports. Owing to the emerging nature of <IR>, there is currently no readily available external data provider supplying in-depth information on integrated reports; therefore, in order to capture heterogeneity between integrated reports, it was necessary to: (i) construct a coding framework from the <IR> Prototype Framework issued by the IIRC in October 2012; and (ii) employ an independent double coding process to code each integrated report against the coding framework so as to determine the level of alignment between the sampled reports and the <IR> framework.

Two key controls were employed in designing the coding framework. First, input was received from key IIRC personnel involved in developing the <IR> framework and second, the coding framework was validated through an investor survey. The investor survey was conducted in December 2012 using Qualtrix. The survey sampled 35 global investor organizations participating in the IIRC's Pilot Programme Investor Network (PPIN). These are large organizations with billions of dollars' worth of assets under management. Fifteen responses were received during the two-week survey period. The survey instrument is the self-constructed coding framework. The respondents were asked to comment on the completeness and appropriateness of using this coding framework to measure the quality of integrated reports. Further, they were asked to rate the ‘importance’ (the extent to which this component is important to investor decision making) and ‘newness’ (the estimated proportion of organizations for which this information is not currently disclosed in publicly available reports, such as annual reports and CSR reports) of each of the 31 components in the coding framework.

The finalized coding framework has 31 components across eight dimensions (refer to Appendix 2). The integrated reports produced by sample companies between 2009 and 2012 were scored against the 31 components from zero to one. 13 Thus the maximum possible total score of an integrated report is 31. Since the coding framework was developed from the principles-based <IR> prototype framework, there are no prescribed specific key performance indicators (KPIs), measurement methods, or disclosure of individual matters. Rather, the intent of the principles-based approach is to strike an appropriate balance between flexibility and prescription that recognizes the wide variation in individual circumstances of difference organizations while enabling a sufficient degree of comparability across organizations to meet relevant information needs (IIRC, 2013a). Therefore, tensions such as the need to cover many aspects and yet be concise are reflected in the principles of the framework and are interpreted by the coders. Recognizing the subjective nature of the coding process due to the principles-based nature of the coding framework, we employed a 100% double coding process. Two coders, including one of the authors, completed the process independently and then engaged in iterative rounds of discussions until all disagreements were resolved. The Pearson/Spearman/Cronbach's Alpha/Standardized Cronbach's Alpha scores between the two coders are 0.975/0.975/0.986/0.987.

The validity of the coding framework was further confirmed by the consistency between the scores derived using the coding framework and the external ratings produced by Ernst and Young on the quality of the integrated reports produced by the top 50 listed companies on JSE in 2011 14 (EY, 2012).

The higher the total score of the integrated report, the more aligned the report is with the <IR> framework. 15 We expect this to improve information transparency and thereby reduce the cost of equity capital. Thus IR_TOTAL is expected to have a negative coefficient.

Control Variables

The control variables follow Dhaliwal et al. (2011, 2012) and Francis et al. (2008). The definitions of these control variables can be found in Appendix 1. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1 and 99 percentile to deal with potential outliers. 16

Descriptive statistics—sample for analysts' earnings forecast analysis

Table 1, Panel A presents the descriptive statistics for the pooled sample used for the analyst earnings forecast analysis. The mean disclosure score of the integrated reports is 6.273 out of a maximum possible score of 31, reflecting the early stage of the practice of producing integrated reports. The total number of observations for each of the sample years (2009–2012) is 114/113/110/106 respectively. The yearly statistics (not reported) do not reveal particular patterns among dependent variables, although the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework, measured by the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL), displays an upward trend across the sample years, reflecting a learning effect for the required disclosures over time. There is also a jump from 4.902 to 7.724 in the disclosure score between 2010 and 2011, consistent with the timing of the adoption of the ‘apply or explain’ requirement by the JSE. On average, over 30% of the companies were found to still issue standalone CSR reports in addition to integrated reports. As the yearly changes in variables are included in the regression models, Panel B of Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the variables in their changes form. The sample size thus reduces from 443 to 307. 17 Overall, there is very little change to the dependent variables (∆FCERROR and ∆FDISP). The total disclosure score of integrated reports (∆IR_TOTAL), on the other hand, improves by an average of 2 each year.

| Panel A: Full sample and yearly sample for analyst earnings forecast analysis | Panel B: Summary statistics of the yearly change in variables used in the full sample for analyst earnings forecast analysis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Full sample | ||||||||||||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Variable | Obs | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| FCERROR | 443 | −4.406 | −4.339 | 1.240 | −7.594 | 0.118 | ∆FCERROR | 307 | −0.048 | −0.029 | 1.135 | −2.955 | 2.904 |

| FDISP | 443 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.183 | ∆FDISP | 307 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.013 | −0.035 | 0.082 |

| IR_TOTAL | 443 | 6.273 | 5.250 | 4.400 | 0.250 | 18.000 | ∆IR_TOTAL | 307 | 1.938 | 1.500 | 2.028 | −1.750 | 8.750 |

| SIZE | 443 | 9.760 | 9.760 | 1.704 | 6.325 | 13.871 | ∆SIZE | 307 | 0.093 | 0.079 | 0.150 | −0.412 | 1.242 |

| VAREARN | 443 | 0.593 | 0.593 | 1.344 | −3.281 | 3.597 | ∆VAREARN | 307 | 0.035 | −0.003 | 0.218 | −0.709 | 1.582 |

| ANANO | 443 | 6.363 | 6.363 | 3.883 | 1.083 | 16.000 | ∆ANANO | 307 | 0.180 | 0.080 | 0.180 | −3.250 | 3.750 |

| LnANANO | 443 | 1.615 | 1.615 | 0.739 | 0.080 | 2.773 | ∆LnANANO | 307 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.300 | −0.875 | 0.865 |

| FFIN | 443 | −0.427 | −0.427 | 0.495 | −1.000 | 0.000 | ∆FFIN | 307 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.427 | −1.000 | 1.000 |

| LOSS | 443 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.235 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ∆LOSS | 307 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.302 | −1.000 | 1.000 |

| HORIZON | 443 | 240.953 | 240.953 | 18.481 | 123.200 | 355.000 | ∆HORIZON | 307 | 2.713 | −0.583 | 18.694 | −139.300 | 112.750 |

| CSR | 443 | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.464 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ∆CSR | 307 | −0.010 | 0.000 | 0.338 | −1.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C: Full sample and yearly sample for cost of equity capital analysis | Panel D: Mean comparisons for sub-samples of cost of equity capital analysis (means in bold are significantly different at p < 0.05, two-tailed) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Full sample | High analyst following | Low analyst following | t-value | p-value | ||||||||||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Median | Std.Dev. | Min | Max | Variable | Obs | Mean | Obs | Mean | Obs | Mean | ||

| ICC_PEG | 430 | 0.137 | 0.126 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.372 | ICC_PEG | 430 | 0.137 | 216 | 0.126 | 214 | 0.148 | 4.619 | 0.000 |

| IR_TOTAL | 430 | 6.283 | 5.250 | 4.412 | 0.250 | 18.000 | IR_TOTAL | 430 | 6.283 | 216 | 8.370 | 214 | 4.175 | −11.196 | 0.000 |

| SIZE | 430 | 9.433 | 9.418 | 1.532 | 5.264 | 13.002 | SIZE | 430 | 9.433 | 216 | 10.279 | 214 | 8.580 | −13.803 | 0.000 |

| BM | 430 | 0.644 | 0.510 | 0.546 | 0.063 | 4.108 | BM | 430 | 0.644 | 216 | 0.497 | 214 | 0.792 | 5.806 | 0.000 |

| LEV | 430 | 0.552 | 0.536 | 0.216 | 0.012 | 1.000 | LEV | 430 | 0.552 | 216 | 0.580 | 214 | 0.524 | −2.679 | 0.008 |

| LTG | 430 | 0.210 | 0.116 | 0.192 | −0.167 | 1.297 | LTG | 430 | 0.210 | 216 | 0.184 | 214 | 0.236 | 2.816 | 0.005 |

| DISP | 430 | −2.489 | −2.560 | 0.841 | −5.725 | 0.069 | DISP | 430 | −2.489 | 216 | −2.544 | 214 | −2.433 | 1.362 | 0.174 |

| BETA | 430 | 0.886 | 0.862 | 0.400 | −0.018 | 2.145 | BETA | 430 | 0.886 | 216 | 0.884 | 214 | 0.888 | 0.098 | 0.922 |

| DA | 430 | 0.051 | 0.032 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.355 | DA | 430 | 0.051 | 216 | 0.048 | 214 | 0.054 | 1.018 | 0.309 |

| CSR | 430 | 0.302 | 0.000 | 0.460 | 0.000 | 1.000 | CSR | 430 | 0.302 | 216 | 0.380 | 214 | 0.224 | −3.550 | 0.000 |

| Panel E: Summary statistics of the yearly change in variables used in the full sample for the cost of equity capital analysis plus mean comparisons for sub-samples partitioned by the sample median number of analysts following (means in bold are significantly different at p < 0.05, two-tailed) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | High analyst following | Low analyst following | t-value | p-value | ||||||||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | median | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Obs | Mean | Obs | Mean | ||

| ∆ICC_PEG | 294 | −0.00835 | −0.01004 | 0.03335 | −0.18110 | 0.13476 | 147 | −0.00810 | 147 | −0.00861 | −0.1303 | 0.8964 |

| ∆IR_TOTAL | 294 | 1.92260 | 1.50000 | 2.02450 | −1.75000 | 8.75000 | 147 | 2.40646 | 147 | 1.43878 | −4.2134 | 0.0000 |

| ∆SIZE | 294 | 0.13443 | 0.13782 | 0.28915 | −1.13943 | 1.55216 | 147 | 0.12112 | 147 | 0.14775 | 0.6410 | 0.5220 |

| ∆BM | 294 | −0.00235 | −0.00571 | 0.26678 | −1.57491 | 1.58686 | 147 | 0.01805 | 147 | −0.02275 | −1.3125 | −1.3125 |

| ∆LEV | 294 | −0.00968 | −0.00595 | 0.05095 | −0.26873 | 0.17475 | 147 | −0.00929 | 147 | −0.01008 | −0.1320 | 0.8951 |

| ∆LTG | 294 | −0.00175 | −0.00201 | 0.20035 | −0.96200 | 0.98587 | 147 | 0.00029 | 147 | −0.00379 | −0.1167 | 0.9072 |

| ∆DISP | 294 | −0.06487 | −0.08024 | 0.60574 | −1.63937 | 1.77347 | 147 | −0.10335 | 147 | −0.02639 | 0.9216 | 0.3575 |

| ∆BETA | 294 | −0.00883 | −0.00624 | 0.12012 | −0.55675 | 0.42747 | 147 | −0.01302 | 147 | −0.00465 | 0.6053 | 0.5454 |

| ∆DA | 294 | −0.00287 | −0.00018 | 0.06609 | −0.23071 | 0.30895 | 147 | −0.00502 | 147 | −0.00072 | 0.5578 | 0.5774 |

| ∆CSR | 294 | −0.00340 | 0.00000 | 0.32525 | −1.00000 | 1.00000 | 147 | −0.04082 | 147 | 0.03401 | 1.9822 | 0.0484 |

- Refer to Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

Sample for Cost of Equity Capital Analysis

Table 1, Panel C provides summary statistics for the cost of equity capital analysis. The average ICC for JSE listed companies during the period 2009 to 2012 is 0.137, which is slightly higher than that of US listed companies (which is usually around 0.11, see Easton and Monahan, 2005), but is closer to the results for South African companies in international studies (i.e., 0.16, see Hail and Leuz, 2006). Overall, the cost of capital shows a moderate downward trend across the sample years. Similar to the results in Panel A, the average total score for integrated reports is 6.283 and displays a slight increase from 2009 (3.479) to 2010 (4.733), but almost doubles in the year 2011 (7.493), reflecting the effect of mandatory JSE regulation on <IR> adoption by companies.

Hypothesis 2(a) hypothesizes that the negative relationship between the level of alignment of reports and the cost of equity capital will be more significant among companies with a low analyst following. Panel D of Table 1 displays a mean comparison between companies with a high (low) analyst following. 17 The results show that companies with a high analyst following have a lower ICC (t = 4.619) and higher <IR> disclosure scores (t = 11.196); are larger in size (t = 13.803); have a lower book-to-market ratio (t = 5.806); are more highly leveraged (t = 2.679); have a lower growth rate (t = 2.816); and are more likely to issue standalone CSR reports (t = 3.550).

Panel E of Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the yearly change in all variables used for the cost of equity capital analysis. Owing to the use of the changes form, the sample size reduces from 430 to 294. On average, there is a decrease in the ICC of 0.8% (∆ICC_PEG) and an increase in the integrated report disclosure score of nearly 2 (∆IR_TOTAL) across the sample years. When the difference between companies with differing levels of analyst following 18 is examined, there are no significant differences between the two groups except for the changes in the integrated report disclosure score (∆IR_TOTAL, t = 4.213, p < 0.000) and issue of a standalone CSR report (∆CSR, t = 1.982, p < 0.048). This shows that companies with a larger analyst following improved in their disclosure scores. This is consistent with the findings from Graham et al. (2005), that companies with a large analyst coverage view reputation for transparent reporting as an important motivation for voluntary disclosure. Meanwhile, companies with a larger analyst following issue fewer standalone CSR reports, which is likely due to their perception that the practice of <IR> is sufficient (thus rendering the standalone CSR report to be less relevant).

The Pearson correlations (untabulated) suggest a negative relationship between analyst forecast error (FCERROR) and disclosure scores (IR_TOTAL) (−0.196, p < 0.000). Similarly, a negative relationship is identified between analyst forecast dispersion (FDISP) and disclosure scores (−0.099, p < 0.038), although with a much smaller magnitude. A negative relationship between the disclosure score of integrated reports (IR_TOTAL) and the cost of equity capital measures is also identified (−0.161, p < 0.0008). Other variables all have expected signs and none of the unexpected correlations are high enough to raise potential multicollinearity concerns.

Empirical Results

H1(a) testing

In Hypothesis 1(a), a negative relationship is hypothesized between the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework and analyst earnings forecast error. Hypothesis 1(a) is tested by estimating an OLS regression of the changes in analyst earnings forecast error (∆FCERROR) on the changes in the total disclosure scores (∆IR_TOTAL) of companies' integrated reports. As outlined earlier, the sample size now decreases from 443 to 307. The results are reported in Table 2 (column 1). The total disclosure scores of integrated reports are observed to be negatively and significantly related to analysts' earnings forecast error, providing support for Hypothesis 1(a). In particular, a one-unit increase in the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL) decreases the scaled analysts' forecast error (FCERROR) by 9.72%.

| Predicted sign | (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV = ∆ FCERROR | DV = ∆FDISP | ||

| ∆IR_TOTAL | − | −0.0972*** (−3.148) | −0.000447 (−1.374) |

| ∆SIZE | − | 0.694 (1.645) | −0.0126** (−2.037) |

| ∆VAREARN | + | −0.799*** (−3.075) | 0.000854 (0.379) |

| ∆LnANANO | − | 0.121 (0.503) | 0.00192 (0.593) |

| ∆FFIN | + | −0.146 (−0.873) | −0.00177 (−1.410) |

| ∆LOSS | + | −0.110 (−0.452) | −3.19e-05 (−0.0129) |

| ∆HORIZON | + | 0.00453 (1.194) | −3.34e-05 (−0.839) |

| ∆CSR | − | 0.110 (0.487) | 0.000160 (0.0892) |

| Year | Yes | Yes | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | |

| Clustered by companies | Yes | Yes | |

| Constant | −0.353*** (−2.812) | 0.00287 (1.195) | |

| Observations | 307 | 307 | |

| R-squared | 0.097 | 0.133 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.0370 | 0.0752 |

- Coefficient values (robust t-statistics) are shown with standard errors clustered at the company level.

- *** ,

- ** , and

- * , indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively, two-tailed. Refer to Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

Other variables significantly impacting analyst earnings forecast error include company size (SIZE, t = 1.645, p < 0.100) and earnings volatility (VAREAN, t = −3.075, p < 0.001). 15 Overall, supporting evidence has been found for Hypothesis 1(a) that the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework is negatively associated with analyst earnings forecast error.

H1 (b) testing

Hypothesis 1(b) hypothesizes a negative association between the level of alignment of integrated reports and analyst forecast dispersion. The regression results for Hypothesis 1(b) are shown in column 2 of Table 2. Although a negative sign is observed for the measure of the level of alignment (i.e., the total disclosure score of integrated reports IR_TOTAL), it is not statistically significant enough for inferences to be drawn (t = −1.374). It is also noted that the coefficient on the disclosure score (IR_TOTAL) has a much smaller magnitude (−0.0004) compared to that for analyst forecast accuracy (−0.0972) as reported in column 1 of Table 2. This finding indicates that the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework has a stronger effect in influencing analyst forecast error than analyst forecast dispersion. The only control variable that is significant in affecting analyst forecast dispersion is company size (t = −2.037, p < 0.050). Given that the negative relationship is not statistically significant, Hypothesis 1(b) is not found to be supported.

Collectively, there is evidence that an improvement in the level of alignment of companies' integrated reports helps improve analyst earnings forecast accuracy. There is no evidence statistically significant enough for us to conclude that such improvement also helps reduce analyst forecast dispersion. The insignificant result found on analyst forecast dispersion is not surprising given the equivocal nature of findings from previous studies on analyst forecasts dispersion (e.g., Cuijpers and Buijink, 2005; Preiato et al., 2014).

H2 and H2(a) testing

Hypothesis 2 hypothesizes a negative relationship between the ICC and the disclosure score of companies' integrated reports. Hypothesis 2 is tested by estimating OLS regressions of the changes in the cost of equity capital (∆ICC_PEG) on the changes in the disclosure scores of integrated reports (∆IR_TOTAL). The regression results are presented in Table 3. As explained earlier, the sample size is now reduced from 430 to 294, which works against finding statistically significant results for the hypothesis testing. Nonetheless, a negative and significant relationship is identified for the overall sample (column 1), providing support for Hyotheses 2 and 2(a). Specifically, a one-unit improvement in the level of alignment of the integrated report brings down the cost of equity capital by 0.216% (column 1). The sub-sample analysis shows that this negative relationship is mainly contributed by the sub-group with a lower analyst following (column 3), providing support for Hypothesis 2(a). The finding is consistent with Botosan (1997) and Griffin and Sun (2014). It also provides support for the voluntary disclosure theory and the Merton (1987) theoretical model that the benefit of higher quality disclosures is expected to be more pronounced in environments with low public information availability.

| Predicted sign | DV = ∆ICC_PEG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||

| Full sample | High analyst following | Low analyst following | ||

| ∆IR_TOTAL | − | −0.00216* (−1.863) | −0.000936 (−1.032) | −0.00560* (−1.953) |

| ∆SIZE | − | −0.0429** (−2.339) | −0.00547 (−0.334) | −0.0579*** (−2.709) |

| ∆BM | + | −0.0177 (−1.078) | −0.0234 (−0.845) | −0.00985 (−0.624) |

| ∆LEV | + | 0.0443 (1.076) | 0.0147 (0.386) | 0.0906 (1.040) |

| ∆LTG | + | −0.00524 (−0.582) | 0.0159* (1.688) | −0.0172 (−1.238) |

| ∆DISP | + | −0.00329 (−0.698) | 0.00373 (0.687) | −0.00804 (−1.310) |

| ∆BETA | + | −0.0109 (−0.437) | −0.0285 (−1.633) | 0.000471 (0.0131) |

| ∆DA | + | 0.00803 (0.249) | −0.0137 (−0.653) | 0.0775 (1.264) |

| ∆CSR | − | −0.00930** (−2.197) | −0.0140* (−1.877) | −0.00644 (−0.855) |

| Year indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Industry indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Clustered by companies | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Constant | −0.000129 (−0.0289) | −0.00705* (−1.746) | 0.00292 (0.443) | |

| Observations | 294 | 147 | 147 | |

| R-squared | 0.132 | 0.189 | 0.258 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.0687 | 0.0603 | 0.140 | |

- Coefficient values (robust t-statistics) are shown with standard errors clustered at the company level.

- *** ,

- ** , and

- * , indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively, two-tailed.

- Refer to Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

Sensitivity Analysis

Heckman's two-stage analysis

Although multiple measures are employed in the main analysis to ameliorate the potential endogeneity concern, we run the commonly used Heckman's two-stage analysis as a sensitivity analysis. In order to perform Heckman's two-stage analysis, the endogenous variable (i.e., IR_TOTAL) is converted into a dummy variable using the sample median split (i.e., HIGHIR) in the first stage as the dependent variable. Two exclusion restrictions are included in the first-stage analysis. IR_POLICY is a dummy variable coded one if the company's annual report is subject to the <IR> policy, that is, if the company's fiscal year starts on or after March 2010 and zero otherwise. 11 The other exclusion restriction we use is profitability, measured as the income before extraordinary items over total assets (ROA) of the reporting company. 12

Results from the second stage of the Heckman's analysis (reported in Tables 4 and 5) show that once Heckman's two-stage analysis is performed, 13 the dummy variable of <IR> disclosure score (HIGHIR) now becomes negatively and significantly related to analyst forecast error and dispersion, lending additional support for Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b). As for the results on Hypothesis 2, the coefficient on HIGHIR (column 4 of Table 5) now becomes negative as hypothesized, and with a t-statistic (t = −1.430) close to conventional significance level compared to a positive sign (column 1 of Table 5) before Heckman's two-stage analysis is used. The sub-sample analysis produces results consistent with Hypothesis 2(a) and the main analysis.

| IVs | Raw analysis | Heckman's two-stage analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (5) | (6) | |

| DV = FERROR | DV = FDISP | DV = FERROR | DV = FDISP | |

| IR_TOTAL | −0.0320 (−1.263) | −0.000420 (−1.406) | ||

| HIGHIR | −0.351** (−2.266) | −0.00459** (−2.286) | ||

| SIZE | −0.00411 (−0.0616) | −0.000114 (−0.104) | 0.202* (1.885) | 0.00367 (1.425) |

| VAREARN | 0.0298 (0.535) | −0.000675 (−0.563) | −0.0205 (−0.386) | −0.00155 (−1.513) |

| LnANANO | −0.444*** (−3.693) | −0.00326* (−1.806) | −0.237* (−1.834) | 0.000619 (0.326) |

| FFIN | 0.0424 (0.330) | 0.000789 (0.475) | 0.0593 (0.469) | 0.00115 (0.640) |

| LOSS | 0.422 (1.270) | 0.00788 (1.412) | 0.592* (1.797) | 0.0110** (2.003) |

| HORIZON | 0.00796** (2.002) | 4.32e-05 (0.953) | 0.00692 (1.506) | 2.38e-05 (0.485) |

| CSR | 0.232* (1.843) | 0.00136 (0.833) | 0.302** (2.352) | 0.00255 (1.517) |

| INVMILLS | 0.762** (2.352) | 0.0142 (1.561) | ||

| Year indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −6.176*** (−5.291) | 0.00942 (0.851) | −8.740*** (−6.543) | −0.0380 (−1.173) |

| Observations | 443 | 443 | 443 | 443 |

| R-squared | 0.292 | 0.182 | 0.318 | 0.221 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.259 | 0.143 | 0.284 | 0.182 |

- Coefficient values (robust t-statistics) are shown with standard errors clustered at the company level.

- *** ,

- ** , and

- * , indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively, two-tailed.

- Refer to Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

| IVs | Raw analysis | Heckman's two-stage analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| DV = ICC_PEG | DV = ICC_PEG | DV = ICC_PEG | DV = ICC_PEG | DV = ICC_PEG | DV = ICC_PEG | |

| Full sample | High analyst following | Low analyst following | Full sample | High analyst following | Low analyst following | |

| IR_TOTAL | 0.000225 (0.328) | 0.00114* (1.696) | −0.00305 (−1.497) | |||

| HIGHIR | −0.00764 (−1.430) | 0.00668 (1.500) | −0.0229** (−2.478) | |||

| SIZE | −0.00541** (−2.533) | −0.00198 (−0.787) | −0.00418 (−0.934) | −0.0101*** (−2.931) | −0.00335 (−0.950) | −0.0135** (−2.440) |

| BM | 0.0105 (1.589) | 0.00912* (1.974) | 0.0114 (1.324) | 0.00699 (1.010) | 0.00740 (1.433) | 0.00524 (0.602) |

| LEV | 0.0136 (0.925) | −0.0255* (−1.699) | 0.0450 (1.598) | 0.00199 (0.122) | −0.0300* (−1.750) | 0.0210 (0.725) |

| LTG | 0.0556*** (4.254) | 0.0475*** (3.077) | 0.0520** (2.518) | 0.0590*** (4.467) | 0.0516*** (3.113) | 0.0569*** (2.768) |

| DISP | 0.0140*** (3.543) | 0.0196*** (4.892) | 0.0119** (2.150) | 0.0137*** (3.564) | 0.0191*** (4.631) | 0.0119** (2.204) |

| BETA | 0.0291*** (3.888) | 0.0190** (2.008) | 0.0374*** (3.379) | 0.0273*** (3.583) | 0.0177* (1.795) | 0.0326*** (2.971) |

| DA | 0.0238 (0.725) | −0.0107 (−0.443) | 0.0741 (1.199) | 0.0293 (0.904) | −0.0128 (−0.499) | 0.0792 (1.309) |

| CSR | −0.0109** (−2.134) | −0.0150*** (−2.990) | −0.00419 (−0.406) | −0.0119** (−2.363) | −0.0167*** (−3.232) | −0.00816 (−0.815) |

| INVMILLS | −0.0197* (−1.763) | −0.00889 (−0.788) | −0.0281* (−1.790) | |||

| Year indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Clustered by companies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.164*** (4.911) | 0.166*** (5.987) | 0.150** (2.636) | 0.238*** (4.789) | 0.191*** (3.995) | 0.270*** (3.504) |

| Observations | 430 | 216 | 214 | 430 | 216 | 214 |

| R-squared | 0.429 | 0.557 | 0.407 | 0.438 | 0.553 | 0.427 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.399 | 0.509 | 0.342 | 0.408 | 0.502 | 0.361 |

- Coefficient values (robust t-statistics) are shown with standard errors clustered at the company level.

- *** ,

- ** , and

- * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively, two-tailed.

- Please refer to Appendix 1 for variable definitions.

Overall, compared to the results when the endogeneity concern is not controlled for, the Heckman's two-stage analysis produces results that are consistent with other approaches used in the main analysis to control for endogeneity concerns.

Alternative Measures of the Cost of Equity Capital

In this section, we report results using several alternative measures of the cost of equity capital: first, the GLS model developed from Gebhardt et al. (2001), second, the CT model developed from Claus and Thomas (2001), and third, the simultaneous estimation method developed from Easton et al. (2002). All three alternative measures produce results consistent with the main analysis, albeit not statistically significant. The insignificant results from using these three alternative measures could potentially be due to the different assumptions that go into these measures, and perhaps more importantly, because ICC_PEG is much more parsimonious in calculation compared to any of the other measures, suffers fewer measurement errors, and is recommended as one of the superior models in Botosan and Plumlee (2005).

As a second type of alternative measure, the realized (ex-post) return (calculated as the 12-month monthly market-adjusted cum-dividend returns calculated from daily security prices after fiscal year-end) is used as the dependent variable to replace the implied (ex-ante) cost of equity capital. One of the most commonly used measures to evaluate the validity of accounting-based estimates of the ICC is to test their association with realized returns (Easton and Monahan, 2005; Guay et al., 2011). Further, the ex-post realized return has the advantage of suffering fewer measurement errors than the implied (ex-ante) cost of equity capital. Thus, the realized returns are commonly used as an additional analysis to see if the results corroborate those from using the ex-ante implied return, that is, the implied cost of equity capital (Francis et al., 2008). The regression results (untabulated) reveal that companies with higher <IR> scores are associated with a lower return, consistent with the expectation that these companies are regarded as having lower risks for investors, and are therefore willing to invest with lower returns. This is supported by the findings in Jones et al. (2007), that higher levels of sustainability disclosure are associated with negative abnormal returns, and in Hong and Kacperczyk (2009), that sin stocks (alcohol, tobacco, and gaming) have higher expected returns because they are neglected by norm-constrained investors and face greater litigation risk. The sub-sample analysis also produces similar results to the main analysis in that the negative relationship between the disclosure score and the monthly return is only significant among those with a low analyst following. Therefore, the result on the realized return corroborates those found on the ICC in the main analysis, thus providing further support for Hypotheses 2 and 2a.

Alternative Measures of Analyst Earnings Forecast Error and Dispersion

The measure of forecast error and dispersion in the main analysis is consistent with previous studies such as Lang and Lundholm (1996), Hope (2003), Lehavy et al. (2011) and Dhaliwal et al. (2012). However, Cheong and Thomas (2011) challenged the routinely followed way of measuring analyst forecast error on scale (usually by share price or actual/forecast EPS). Their reasoning was that both analyst forecast error and dispersion vary little with scale for EPS forecasts in a number of large markets around the world. In view of the findings by Cheong and Thomas (2011), we used the unscaled/raw analyst forecast error as an alternative dependent variable in the sensitivity analysis.

The results for Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b) hold, supporting the conclusion that improvement in the disclosure score of the integrated report helps improve analyst forecast accuracy but not forecast dispersion.

Alternative Measures of the Level of Alignment of Integrated Reports with the <IR> Framework

In the main analysis, the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework is measured using the total disclosure score of those reports ranging from 0−31. Although the use of a continuous score is deemed appropriate and necessary given the significant variations in the level of alignment of integrated reports produced, a potential downside is that such a measure is noisy given the limitations of a user-defined coding framework and the inevitable subjectivity that goes into the coding process. To address the aforementioned limitation in the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL), a dichotomous variable (HIGHIR) is created which equals one if the disclosure score on the integrated report produced by the company is greater than the sample median disclosure score and zero if it is not. Although the level of variation is restricted in the use of the dichotomous variable (HIGHIR), it is believed to have the benefit of being less noisy. The use of the dichotomous variable produces qualitatively similar results to those obtained from the main analysis, except when testing Hypothesis 1(b) on the relationship between the level of integrativeness and analyst earnings forecast dispersion. In the latter case a significant and negative relationship was identified (t = −2.084, p < 0.05) as opposed to insignificant results using the continuous disclosure score (IR_TOTAL), lending some support for Hypothesis 1(b).

Another limitation of the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL) is the potential bias derived from the check-list approach used in the scoring process. In order to circumvent such a limitation in the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL), an impression score (IR_IMPR) was also collected during the coding process. The coder was required to score the report from 0–7 based on his/her overall impression of the report against the principles of an integrated report set out by the IIRC. Thus, the impression score (IR_IMPR) is inherently more subjective than the total disclosure score (IR_TOTAL) but suffers less bias due to not employing the check-list approach of coding. The use of the impression score (IR_IMPR) as the independent variable of interest produces results qualitatively similar to those obtained from the main analysis.

Additional Analyses

Tests on the unique characteristics of <IR>

As mentioned previously, an investor survey was carried out preceding the data collection process to collect respondents' ratings on the level of ‘importance’ and ‘newness’ of the 31 components included in the coding framework. The ratings collected from the survey were then used to create the following three variables: (i) the importance score (IMP), which is the sum of the scores of each component 4 weighted by the median ratings on ‘importance’ from the investor survey; (ii) the newness score (NEW), which is the sum of the scores of each component 5 weighted by the median ratings on ‘newness’ from the investor survey; and (iii) the importance times newness score (IMPNEW), which is the sum of the scores of each component weighted by the median ratings on ‘importance’ and ‘newness’ from the investor survey. The regressions in the main analysis were re-run with these three variables as independent variables of interest to see if the results identified in the main analysis are driven by any of these characteristics of <IR>.

In addition, another variable is created to capture one of the key and unique features of <IR>, that is, connectivity. The connectivity score (CONNECT) is the sum of the scores of those elements reflecting the connectivity principle outlined in the <IR> framework. 6 Results show that all four measures are negatively and significantly related to analyst forecast error, but not dispersion, and three of the four measures, namely, the importance score (IMP), the newness score (NEW), and the importance times newness score (IMPNEW) are found to be significantly negatively related to the cost of equity capital. Hence, the unique connectivity feature of <IR> seems to have a direct effect on analyst earnings forecast tasks, but the flow-on effect for a reduction in the cost of equity capital does not materialize. One possible reason is that the average score on connectivity is very low and lacks variation 7 due to the very early stage of the practice of <IR>. This may limit the power of the test which is particularly pertinent in the analysis of the cost of equity capital.

Current Year and Two-year-ahead Analyst Earnings Forecast

In the main analysis, only the one-year-ahead analyst earnings forecast properties are used as the dependent variable. However, as an additional analysis, the current year and two-year-ahead forecast error and dispersion are also calculated and regressed on the disclosure score of sample companies. Results (untabulated) demonstrate that the disclosure scores of companies' integrated reports are not significantly related to either the current year or the two-year-ahead analyst forecast error and dispersion.

Conclusion

This study is motivated by a need to provide empirical evidence substantiating the claimed benefits of <IR>, which is an emerging corporate disclosure approach that has been described by some as the ‘future of corporate reporting’ (IIRC, 2014a). The significance of <IR> is evidenced by: the growing number of companies voluntarily producing integrated reports; the convening of multiple influential parties including investors under the global authority of the IIRC to provide guidance and impetus to <IR>; and the increasing number of regulations around the world that pay attention to <IR>.

Advocates of <IR> have listed a number of its benefits to multiple parties including reporting companies, providers of financial capital, and broader stakeholder groups. However, to date, few of those claimed benefits have been tested empirically. This study is among the first to provide evidence on the capital market benefits of <IR> in two areas: first, whether the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework affects analyst earnings forecast accuracy and dispersion; and second, whether companies producing integrated reports with a high level of alignment enjoy the benefit of reduced cost of equity capital.

This study takes advantage of the 2010 requirement for companies listed on the JSE in South Africa to produce an integrated report on an ‘apply or explain’ basis. With 443 company-year observations listed on the JSE from 2009 to 2010, we found that the level of alignment of integrated reports is negatively associated with analyst earnings forecast error, demonstrating that information contained in the integrated report is helpful for analysts in formulating their prediction for earnings, probably because the integrated report contains information on corporate strategy, business model, and future-oriented information. Particularly, information representing the ‘connectivity’ and ‘newness’ features of <IR> is negatively associated with analyst forecast error, suggesting an integrated report contains new information over and above the current reporting suite, which therefore gives additional help to analysts when predicting the future profitability of companies. There is only very weak evidence, however, to suggest that the level of alignment is also negatively associated with analyst earnings forecast dispersion.

Further, we found that the improvement in the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework is associated with a subsequent reduction in the cost of equity capital and the realized market returns, which is consistent with the notion that investors are willing to accept a lower rate of return as a result of reduced information risk. Sub-sample analysis reveals that this benefit is more evident among companies with a low analyst following. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the benefit of reduced cost of equity capital from producing high-quality integrated reports (measured as a higher level of alignment with the <IR> framework) could be attributed to an improved information environment for reporting companies. As such, the effect is more significant for those companies with limited information environments, that is, those companies with a smaller analyst following.

These results are obtained after controlling for company-level financial transparency and the issuance of standalone CSR reports. This suggests that information contained in an integrated report is incrementally useful to investors and analysts over and above the current reporting suite. Overall, the results from this study suggest that <IR> does matter to the capital market in that it helps improve the information environment of reporting companies, evidenced by improved analyst forecast accuracy. This improved information environment in turns brings the benefit of a reduced cost of equity capital to reporting companies.

Moreover, this study has extended the test of voluntary disclosure theory into the context of <IR>, which integrates financial information and non-financial information, and has found some evidence consistent with that theory. Importantly, the results of this study provide empirical evidence for some of the claimed benefits of <IR>. This work can therefore inform market and regulatory incentives for the wider adoption of <IR>. Indeed, this study sheds light on the current state and consequences of <IR> adoption in South Africa before and after the JSE listing requirement, which offers valuable information for regulators' assessments regarding the adoption of <IR> in other markets.

However, our results should be considered in light of the following limitations. First, the availability of analyst forecast data and the labour-intensive nature of the coding process constrained the sample size of the study; however, this only works against finding any statistically significant results. Second, the use of a self-constructed coding framework makes future replication difficult. In addition, the principles-based nature of the coding framework brings a certain level of individual judgement to the coding process. Nonetheless, we expect the double independent coding process to significantly alleviate this concern. Third, there is an endogeneity concern. In this study, multiple measures, including the use of the change specification, the lead−lag approach, and the natural experimental setting, were employed to ameliorate the concern. In addition, other commonly used approaches, including the Heckman's two-stage analysis are also used as sensitivity analyses to address the issue. Nonetheless, owing to the inherent limitations of each measure, it is hard to claim that the endogeneity issue has been completely removed from the analysis.