Working on the Railroad: Public Accounting Talent in the United States—The Case of Haskins & Sells (Now Deloitte)

Abstract

Nineteenth century US railroads were the first ‘big businesses’ and had profound influence on society. This paper addresses one source of talent for the early US public accounting profession—railroads. Following the end of the US Civil War (1861–65), industrial expansion was a revolutionary experience, with large trusts appearing in the wake of the railroad's maturing influence on the development of a vast continental economy. Accounting practice also was impacted by railroads. For example, the development of annual reports, income measurement, the standardization of reporting by regulators, developing fixed and variable cost, and throughput concepts for capital intensive business—all were related to the railroads. This paper focuses on a significant link between the emerging public accounting profession and the railroads by examining how an early major US public accounting firm relied upon accounting skill developed within railroads as an important source of talent. Arguably, talent is the most important resource of a professional firm. While it is a commonly held view that the immigration of UK accountants in the late nineteenth century was the source of public accounting talent, this paper provides evidence of a competing explanation—the sourcing of talent from a firm (Haskins & Sells) that continues to the present day as Deloitte. Key leadership and personnel of that time gained their experience while working on the domestic railroads.

The early partners of Haskins & Sells used to claim that no accountant was worth his salt unless he had worked for the railroads.

H&S Reports (1965, p. 22).

Traditional explanations of public accounting talent sourcing in the US in the early period of development include a prominent if not predominant view of the role of immigration to America of British and Scottish accountants in the late nineteenth century. This paper reports research findings of an alternative view, that is, the sourcing of early talent in a major early public accounting firm, Haskins & Sells (now Deloitte). Today, training and career flow—from public accounting to corporations—is quite different from how it was at the founding of the American public accounting profession over 100 years ago. The flow back then was reversed, from industry—in particular, the railroads—to public accounting. The experience gained by accountants and auditors in working with railroads became a major pillar of the CPA profession as ‘railroad’ accounting and auditing practices spread, particularly to industrial and financial companies.

Railroads played a vital role in the development of nineteenth century America (Previts and Merino, 1998, p. 160). Railroads were also prominent in sourcing public accounting talent. The needs of railroads revolutionized the country by creating new industries such as coal and iron mining, steel, travel and the associated development of hotels and sightseeing, and communications with the advance of the telegraph, which utilized railroad property and controlled the movement of trains. Railroads also led to the development of management career professionals, because a hierarchical system of coordination and control became necessary for synchronization of railroad operations. Similarly, railroads stimulated Wall Street to the extent that most securities being traded at the end of the nineteenth century were railroad stocks and bonds, as the railroads required unprecedented amounts of capital. The railroads brought towns and their citizens together—forging a nation out of a collection of states. The growth of railroads created ‘railroad time’—the standardization of the time-of-day zones for regions of the country. And yet, the railroads' influence on US public accounting has not been explained in depth. This paper aims to fill that gap.

As to talent, there were other turn-of-the-century public accounting sources in the US, including old-line bookkeeping firms that had offered their services for at least a generation before; some in this business sought to upgrade their status by joining the new profession. And, as noted, the influx of chartered accountants from the UK led to the establishment of several firms, some opening branches of their UK businesses. America proved to be a profitable, growing market for these British firms, staffed with partners who had been trained, apprenticed, and chartered in the UK. Arthur Young, a Scottish immigrant, was different in that he formed his firm after working in America, yet his ‘academy’ was the British accounting practice from which he had received the foundation of his experience.

This paper provides evidence of a previously unnoticed phenomenon as to a significant source of talent in the establishment of the public accounting profession—the US railroads. The paper discusses the influence of the American railroads, and the accountants they educated, on the early development of public accounting in America—with specific emphasis on the founders and early staff at the firm of Haskins & Sells (H&S). H&S was the first truly American CPA firm and was within five years of its founding the largest CPA firm in the country. The railroad roots of that firm's early partners and staff provide support for a premise that railroads shaped American's public accounting profession in a unique and meaningful way.

Literature Review

A review of previous research generally fits well into the following groups: migration from the UK; railroad sourcing of talent; and railroad accounting innovations. These will be explored in turn in the following subsections

UK Migration

General histories have often alluded to the fact that the American accounting profession grew from British roots (Chatfield, 1977, p. 151). To some extent, this was true, but not entirely. Lee points to a lack of qualified public accountants to provide audit services in the US in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Lee, 2001, p. 543), which hindered the development of the profession in the US (Lee, 2001, p. 544) and led to the recruitment of chartered accountants from the UK to fill the void. Some of these immigrants subsequently became giants in the US profession and provided leadership and direction in the development of US public accounting practice. As Lee notes, the immigration of UK accountants into the US was a temporary flow and never formed the majority in US practice (Lee, 2001, p. 538). Thus, there seems to have been other streams of influence at work in the development of the US accounting profession. The railroads were one such major influence.

Lee also observes that the first decade of the twentieth century was ‘exceedingly important in the history of the US public accountancy profession’ (Lee, 2001, p. 551). This period is the focal point of this study as well. Finally, Lee observes that networking by firms in the recruitment of accountants from the UK (Lee, 2001 p. 557) was often based on recruitment of those from the same birthplace, or with the same credentials and experience, as the firm partners. This same kind of networking took place with railroad accountants entering into public accounting.

Railroad Sourcing of Talent

Miranti and Goodman point out that the ‘railroad accounting model’ was developed in the nineteenth century as a response to the information needs of three groups (Miranti and Goodman, 1996, p. 487). First was management—the railroad managers who utilized cost data to operate the railroads, controlling people and equipment across a wide geographical area according to a close schedule and a single-track system that required careful coordination. Second were investors who had provided unprecedented amounts of capital to build rail lines. This group needed information to evaluate stock and bond investments. Given their external position, these providers of capital also had to monitor railroad managers. Third were regulators at state and national levels who used accounting information to control rates charged for freight and passengers. The ‘railroad accounting model’ dominated the nineteenth century such that it influenced capital-intensive industries that were seeking capital to develop, such as the steel industry, utilities, and manufacturers (Miranti and Goodman, 1996, p. 487).

Railroad Accounting Innovations

Previts, Samson, and Flesher have examined extensively the contributions of US railroads prior to the Civil War (1861–65) to the development of accounting and auditing. Previts and Samson (2000) analyzes the content of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) annual reports for 25 years to trace the development of annual reports, their content, and the evolution of financial statement format (Previts and Samson, 2000). Flesher et al. (2003, 2005) examine the use of the audit committee of directors by railroads. The public interest dimension of US railroads is examined in Previts et al. (2003) and the problems of income measurement of nineteenth century railroads are examined in Samson et al. (2003). In addition Samson et al. (2006) examine corporate governance and raising capital from external investors during the early years (1831) at the B&O Railroad. Samson and Previts (1999) consider managerial accounting information developed and utilized at the development stage of the B&O. This issue is further explored for its cost accounting contributions in Flesher et al. (2000). Flesher et al. (1996) profiles the early CPAs who started the US accountancy profession, a group that included both Haskins and Sells. With respect to financial statements, an article by Rosen and DeCoster (1969) attributes the invention of the cash-flow statement to the nineteenth century railroads. These studies provide examples of railroad innovations, including the format and content of annual reports, the measurement of income with depreciation of long-lived assets as not only a theoretical but a pragmatic issue, the standardization of accounting methods and accounts to aid regulators, the concept of retained earnings as a source of capital, and the use of internal auditors, controllers, audit committees, vouchers, and controls over cash. The managerial accounting concepts of fixed costs and variable costs and the impact of efficiency (throughput) on the profitability of large scale, capital intensive businesses were learned at the railroads and later applied in heavy manufacturing. The studies indicate the role played by the railroads in the development of accounting in America; the thesis of this article is to emphasize that, to a similar extent, individuals with railroad accounting experience were a major source of the talent that developed the American public accounting profession.

The Railway Accounting Officers Association

The professional development of railroad accountants and auditors can be considered as stemming from two phenomena—one dealing with the subject matter and the other with the channelling of employment opportunities. A major factor was the establishment of the Railway Accounting Officers Association (RAOA), which occurred about the same time that the American Institute of Accountants (now the AICPA) was founded. The RAOA, successor to the Association of American Railway Officers, traces its history to 1887. It was formed to assist in solving the problems created by individual railroad billing practices for freight shipments across several railroad lines. A uniform method of billing and settlement was needed and was developed by the Association. This billing/settlement for freight shipments was quickly adopted by most railroads. Thus, this association of railroad accountants was instrumental in resolving a specific industry problem. The Association then became involved in working with the newly created Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), an agency that had the task of regulating railroads, particularly the fees charged for inter-state shipments of freight (RAOA, 1926).

Eight years before the passage of the 1887 Act to Regulate Commerce that established federal oversight by the ICC of multi-state railroads, the State Railroad Commissioners regularly met to urge uniformity in railroad accounting. The 1879 National Convention of Railroad Commissioners met in Saratoga Springs, New York, in June. The main topic at the meeting was uniformity of accounts kept by railroads in their reporting to state regulators, unsurprising given that the leading state regulator was Charles Francis Adams (grandson/great grandson of the two Presidents Adams), who had long worked in regulating Massachusetts railroads by trying to require uniform financial reporting that would allow the financial markets to regulate railroads. The presentations at the Convention were reported in Railroad Gazette and also in Railway Age at the time. These and subsequent discussions by the state railroad commissioners caused the RAOA, the voluntary organization of railroad accountants formed to deal with inter-railroad billing practices, to take up the issue of uniform reporting (Cullen, 1926, p. 798).

In regulating the railroads, the ICC found itself woefully understaffed. To carry out the mandate of the 1887 Act to Regulate Commerce, standardized accounting reports of each railroad were needed. To accomplish its work at a minimum cost to the ICC, the chief of the ICC's Bureau of Accounts, Henry C. Adams (no relation to C. F. Adams), utilized the accountants at the railroads through the industry association, the RAOA (Miranti and Goodman, 1996, p. 488). Adams saw the railroad accountants as having a public purpose—to help the government regulate the railroad—in addition to the traditional duties of employees looking after the interests of their employer. The ICC sought to employ the concept of ‘fair return’ for railroad shipment rates and required accounting information from the railroads about their cost and profits. Because each railroad was calculating its income differently, the ICC specified uniform accounting. The RAOA worked to help develop this uniform accounting along lines tracing back to the Saratoga Springs Convention.

Working together in the association caused these accountants to think of themselves other than as employees of a given railroad employer. They saw themselves as confronted by similar problems—changes that were being mandated by regulators, and dealing with managers and superintendents who operated the railroad without an appreciation of accounting and auditing. Railroad accountants began to bond together and started to think of themselves as professionals, with duties and loyalties different from mere employees. This feeling is evident in an editorial in Railway Age that is quoted in RAOA (1926), which praises the accounting officers for the independence shown despite pressure from management to support the effort to open the railroad accounts to public inspection (ICC) in 1906. The railway accountants saw cooperation and sharing of information with their colleagues at other lines as important and the Association promoted free interchange of business ideas. They began to envision themselves as a profession, perceiving that their responsibilities went beyond those of being good employees to investors and to users of financial accounting information (RAOA, 1926, p. 12). R. E. Berger, auditor of the Wabash Railroad Company, echoed this idea of a profession of accounting when he described the railroad accountant as having a duty ‘to promote methods that are considered to be for the best interest of railway accounting as a science and as a profession’ (RAOA, 1926, p. 10). In a 1907 letter written by the ICC to the RAOA, the Commission pointed out that not only do railroad accountants have duties and responsibilities to their respective companies, they also had an important duty and responsibility to the public at large. The Commission then points out that railway accountants are ‘joint administrators’ with the ICC to regulate commerce (RAOA, 1926, p. 10).

From this, one can see that railroad accountants certainly moved beyond bookkeeping to being advisors to top management and further, to having public responsibility in their work, giving them a professional identity. This professionalism made accounting officers different from the typical bookkeeper of the period, who was doing similar work as a public accountant, but for a single employer. The RAOA included public accountants as well as railroad accountants; H&S partner Homer A. Dunn represented the firm in the RAOA. In the membership roster, however, public accountants were listed as ‘honorary members’, which presumably meant that they could not vote (since the number of votes a person could cast was based on the number of miles of track that person's company operated). According to the organization's membership directories, before Dunn joined H&S, he was listed as a regular voting member, but after joining the firm his status changed to honorary.

The second phenomenon related to the professional development of accountants was that their employment was directed toward a clear career path that was established in the hierarchy of railroad accounting positions. This hierarchy seemed to be similar at all railroads such that an accountant could ‘move up’ in his career by moving to a higher position with another employer. As will be seen in a later section, in the 1880–1900 era, there was a very fluid employment situation in which young accountants did move frequently from railroad to railroad. The railroads seem to have tolerated and promoted this—perhaps because of a shortage of accounting talent.

Generalizing from the profiles of the H&S partners, the career paths of railroad accountants seem to have commenced at the local station level, where these men started their careers by assisting the station manager or serving as telegraph operators. The next step up was as assistant clerks doing bookkeeping work. The responsibilities were limited to only a particular set of accounts. Typically, this assistant bookkeeper job was in the headquarters or at a major division office. From here, the career typically included time spent as general bookkeepers, and also time serving in the handling of assets, that is, cashiers, paymaster, and so on. The Chief Clerk's position was often the next stage of the railroad accountant's career, followed by the auditor's position. Assistant comptroller and then comptroller were the highest positions attainable.

The fluid and adaptable nature of this career path suggests that railway accountants were particularly well suited to work as CPAs, who were also often in new cities, often on engagements that required travel, and often doing different types of work. The dynamics of frequent job-changes and travel as railway auditors can be found in the backgrounds of H&S partners.

The Founding of Haskins & Sells

The practice of the accounting firm of H&S commenced on 4 March 1895, with the opening of the office in New York City. Prior to establishing their practice, the founders of the firm, Charles Waldo Haskins and Elijah Watt Sells, met and worked for two years together in Washington DC where they served as advisers on a Congressional Commission (the Dockery Commission) to investigate ways of improving the operations of the Executive Branch. Their advice about accounting and auditing became the basis of commission recommendations and led to modernization of the practices of federal departments. With the end of the Commission's work, the two advisers formed their own accounting firm, H&S, and soon became two of the first 11 CPAs in America (Foye, 1970, pp. 1–2).

- Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Co.

- United States Rubber Company

- Erie Railroad Co.

- Vassar College

- Cincinnati & New Orleans Railroad

- American Trust Co.—Cleveland

- Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad

- St Louis Street Railways

- John Muir & Co.

- New York University

- American Express Co.—London and Paris

- Borden's Condensed Milk Co.

- City of New Rochelle

- Presbyterian Hospital

- Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co.

- Atlanta and West Point Railroad Co.

- The Western Railway of Alabama

The railroad clients were obtained mainly because of the strength of Mr Haskins' and Mr Sells' past connections to this industry. Not clearly indicated by the above listing is the relative importance of the railroads, which may have been the major part of H&S's practice in these early days (see Appendix A). The connection with railroads went deeper than railroads being clients. The partners of H&S had much experience and training at railroads. At least nine of the first 10 partners at H&S had significant railroad experience, as did several other accountants within the firm (Foye, 1970). The experiences of many of these individuals are given in the following paragraphs to document how significant the railroad background was during the firm's early years.

Charles Waldo Haskins, the senior partner, was born in New York City in 1852. His family was prominent and well connected within the business community. His father owned a brokerage firm, and Charles married into another prominent New York family (his wife was Henrietta Havemeyer from the Havemeyer Sugar Trust family). Haskins graduated from Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute in 1867 and spent two years studying art in Paris. His first employment was with Frederick Butterfield & Co., an importer in New York City, where he worked five years as an accountant. From here, he moved to his father's brokerage business. Next, Haskins worked as an accountant for North River Construction Company, which was building a railroad line across New York State. Haskins then went to work with the Westshore and Buffalo Railroad, serving as the general bookkeeper and the auditor of disbursements. When the New York Central Railroad acquired Haskins' employer in 1886, Haskins started a sole-practitioner accounting practice in New York City. In the course of serving as a public accountant, Haskins also held several posts—presumably as a part-time officer—with various companies. These positions were as accountant, auditor, or controller for various small railroads, a mining company, a construction company, a steamship company, and a bank (H&S, 1947, p. 8).

During this period as a sole-practitioner, Haskins was the Comptroller for both the Central of Georgia Railway and the Chesapeake and Western Railroad. His role in mining was as the receiver for the Augusta Mining and Investment Company. He held the office of Secretary for a bank, the Manhattan Trust Company, and served as Secretary of the Old Dominican Construction Company. For the Ocean Steamship Company, Haskins served as comptroller. How extensive these roles were and how many occurred at the same time are not known. In any event, Haskins was well connected to New York businesses and had training early in his role as bookkeeper, accountant, comptroller, and auditor with the railroads (H&S, 1947, pp. 7–8).

Elijah Watt Sells had even more extensive experience with railroad accounting. Sells, the junior partner of the H&S firm, was born in 1858 in Iowa. His father worked as an auditor for the US Post Office (appointed by Abraham Lincoln). 1 At 16, Sells became the assistant station agent at Gardiner, Kansas, for the Leavenworth, Lawrence, & Galveston Railroad. Sells next worked in the general office of the Fort Scott & Memphis Railroad in Kansas City. His ensuing job was with the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad. From 1879–1881, Sells served in a succession of jobs—cashier, paymaster, and bookkeeper—for the Chicago, Dubuque, and Minnesota Railroad at Dubuque, Iowa. For the years 1881–1884, Sells was the Chief Clerk for the Comptroller of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company in Portland, Oregon. In 1884, he moved to become the Auditor for the Pacific Coast Railroad (headquartered in San Luis Obispo, California). After a brief stay, he moved up the California coast to San Francisco to work as an auditor for the Oregon Improvements Company. In 1887, he moved back to the Midwest to be the Assistant Comptroller for the Kansas City, Fort Scott & Memphis Railroad. The following year he became the Secretary and Auditor for the Colorado Midland Railroad, which was part of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad (Foye, 1970, p. 5). After five years, Sells became the Chief Clerk for the general auditor of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe. This last position he held for only a few months, before going to Washington DC and serving on the staff of the Congressional Committee (Flesher et al., 1996, p. 259).

Charles Stewart Ludlam became the third H&S partner, after Charles Waldo Haskins' death in 1903. Ludlam also had extensive experience with railroads and acquired his accounting experience there. Ludlam's career began in 1880 at age 14 as an office boy for Pullman Company, which promoted him to bookkeeper to handle the company's capital stock accounts. His next job was in the accounting department of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad. From here, he moved to become the general bookkeeper at the Colorado Midland Railway. In Colorado, Ludlam met and went to work for J. J. Hagerman, a wealthy investor who had extensive Colorado business holdings. Ludlam's job was general accountant and auditor of Hagerman's investments, which included railroads, construction, mining, irrigation, and land companies. Through this Colorado experience, Ludlam met Elijah Watt Sells while the latter was the Secretary and Auditor for the Colorado Midland Railroad. In 1895, when H&S began to practise together in New York City, Charles Ludlam went to work for them. During the early years at H&S, Ludlam worked on special railroad projects including the reorganization of the St Louis Street Railway system and on accounting issues related to rates permitted by Oklahoma. This rate-engagement affected not only Oklahoma railroads, but also railroads of the adjacent states of Missouri and Arkansas (H&S, 1947, pp. 13–15).

Homer Adams Dunn went to work at H&S in 1902 and became the fourth partner in 1907. Prior to arriving at H&S, Dunn had 20 years of railroad experience. He started at 17 as a telegraph operator for the Valley Falls station of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad in 1880. After a year, he was transferred to Augusta, Kansas, to serve as acting agent, then relief agent, operator, and dispatcher. Shortly afterward in late 1881, he was again transferred, this time to Topeka, Kansas, and given the job of stenographer for the Shop Office of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe. He became the stenographer and clerk for the Missouri & Kansas Telephone Company, and then for the United Telegraph Company, during 1882. In 1883, Dunn rejoined the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad as stenographer and clerk to the general freight agent. Dunn left again and became the stenographer and clerk to the Comptroller of the Fort Scott & Memphis Railroad in 1884. In 1888, Dunn worked as the Freight and Passenger Accountant for the Kansas City, Memphis, & Birmingham Railroad. He rejoined the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe in December 1888 as Chief Clerk, working for Elijah Watt Sells. Dunn changed jobs again to become the Chief Clerk of the railroad's Collateral Property Accounts—which represented the railroad's investment in eight coal companies, 10 land companies, two water companies, three retail merchandise companies, a grain operator, and a hospital association. In this position of Chief Clerk of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe, Dunn also was in charge of the General Auditor's Office of the railroad. His duties expanded when, in December 1896, he was also made the assistant auditor of disbursements (H&S, 1947, pp. 15–16).

H&S, formed in 1895, was growing quickly and Haskins' connections led to several railroads becoming clients. The firm needed an auditor with railroad experience; Charles Waldo Haskins wrote to Dunn asking him if he would be interested in joining H&S, ‘if openings came in the east’. He called Dunn ‘a first class railroad accountant’. Dunn initially declined the offer to join the firm but in 1897, Haskins again contacted Dunn. This time Haskins urged Dunn to take a position of Auditor with a client, the Central of Georgia Railway, and to revise the railroad accounting system. Dunn followed Haskins' recommendation and worked with the railroad until 1902 when Sells succeeded in hiring Dunn away from the Central of Georgia Railway (H&S, 1947, pp. 15–16). After joining the firm, Dunn wrote several articles, including ‘Railway Accounting in Its Relationship to the Twentieth Section of the Act to Regulate Commerce’ and ‘Depreciation in Railway Accounting’ (Dunn, 1908).

Howard Cook started with H&S in 1899 as a stenographer. He had worked at the Atlanta & West Point Railroad and at the Western Railway of Alabama, both of which were H&S clients, audited by Elijah Watt Sells. It was Sells who took notice of Cook's abilities, hired him, and encouraged him to become a CPA. Cook took night classes in accounting from Haskins (at New York University) and became a CPA in 1907. He was made a partner of the firm in 1910 (Foye, 1970, p. 34). Much of Cook's accounting knowledge was acquired after leaving the railroads. However, Cook's start at the railroad was instrumental in leading him to H&S and thus to Cook becoming a CPA.

Charles Morris' career is similar to some of the previously discussed H&S partners. He joined H&S in 1900 after spending the first eight years of his post-collegiate career working for several railroads in various positions. During these eight years, he worked his way quickly up the corporate ladder to the position of Chief Clerk for the consolidated Kansas City, Memphis, & Birmingham Railroad and the Kansas City, Fort Scott, & Memphis Railroad. It was during his time at the railroad that he developed his accounting and auditing knowledge (Foye, 1970, p. 34).

John Franklin Forbes came to H&S in 1912 by merging his California-based practice with H&S. The firm knew of Forbes long before the merger; almost a decade earlier, H&S (in 1904 and 1905) had audited the United Railways of California for financier Patrick Calhoun. Forbes had been United Railway's general accountant since 1902. Forbes then went on to open up his own accounting practice in 1906, and continued to do special engagements for United Railways up to 1912 when H&S merged with Forbes' practice. The result was that United Railways was his largest client in California (Foye, 1970, p. 38).

Arthur Stuart Vaughan, after high school graduation in 1888, went to work in the Comptrollers' office of the Cincinnati, New Orleans, & Texas Pacific Railroad. The company president, John Scott, who was also serving as President of the Colorado Midland Railway Company and was an official of several other railroads, mentored him. At Scott's direction, Vaughan worked for several of these railroads. At the Colorado Midland Railway, Vaughan met the company secretary, Elijah Watt Sells. The two founding partners, Mr Haskins and Mr Sells had held a meeting in Scott's 46 Wall Street office in the winter of 1894–95 to discuss plans about opening the firm. They asked Vaughan to join them in opening their New York accounting practice, but he declined. Vaughan conducted audits on a part-time basis for H&S between 1897 and 1900 while employed by Scott. In December 1900 he joined H&S (Foye, 1970, p. 37).

DeRoy S. Fero, another early partner, who received New York CPA certificate number 73 in 1897, had obtained railroad experience as a travelling auditor for the Santa Fe Railroad in early 1897. He joined the firm later in the year and became a partner in 1907. Not too much is known about Fero's early years. He was born in the Midwest in 1866. He left the firm in 1912 due to ill health. He eventually formed his own firm in 1917 and practised until his death in 1940 (Webster, 1954, pp. 348–49).

Leonard Hubbard Conant, a non-partner with significant railroad experience, was one of the pioneers of the CPA profession who held New York CPA certificate number three; he later received New Jersey certificate number 13. 2 In 1902, L. H. Conant was listed as a principal in the firm, having joined by way of merger. When the firm of H&S incorporated in 1903 (following the death of Haskins), Conant was elected as the corporate vice president and treasurer. Conant had been affiliated with a firm in London, Conant & Grant, which merged with H&S in 1901. This was the first merger undertaken by H&S (Foye, 1970, p. 18). Conant was born in Washington DC on 25 April 1856. His father had been associated with J. Condit Smith in the construction of the Chicago & Atlantic Railway. Conant was a descendent of Roger Conant, who had come to America in 1623 and became the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. From 1873 to 1879, Conant worked in the treasurer's office of the New York & Oswego Midland Railway, and in the Freight department of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He worked for his father's firm from 1879 to 1883. He then worked for the Chicago & Atlantic Railway in 1883. In 1889, he left the railroad to form his own public accounting firm, along with a partner, Francis M. Crook (Flesher et al., 1996, p. 256). Crook died in 1894, after which Conant practised on his own until joining H&S. Conant was the 1897–98 treasurer of the American Association of Public Accountants (today, AICPA) and was elected president for 1901–02. A short sketch published in 1897 noted that he specialized in municipal and railroad matters. His knowledge in the latter field led to his engagement by the ICC in its suit against the Lehigh Valley Railroad (‘Leonard H. Conant, C.P.A’, 1897, p. 46).

The H&S Engagement Records: Railroad Clients

The original engagement ledger of H&S from 1901–03 was made available to researchers in 2004 by Deloitte & Touche's contribution to the University of Mississippi Library. The file, which was previously regarded as confidential, was kept for decades in the office of the firm's managing partners. The discussion surrounding this primary document is included herein as evidence to further support the breadth of early public accounting clientele, while observing the ‘anchoring’ of practice—to the degree of 20% of the initial 100 engagements—in railroads, including many important and major roads, such as the Philadelphia & Reading, the Chesapeake & Ohio, the Lehigh Valley, the St Louis, Kansas City, & Colorado, and the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, plus many others.

Given the broad range of clientele on the list and the dominance of railroad trained partners found in the early years of the firm, the secondary influence of their railroad knowledge applied to practice is made even more evident.

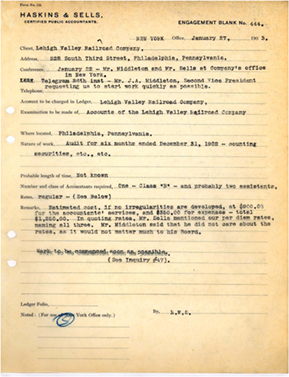

Insights from Preliminary Examination of Engagement File

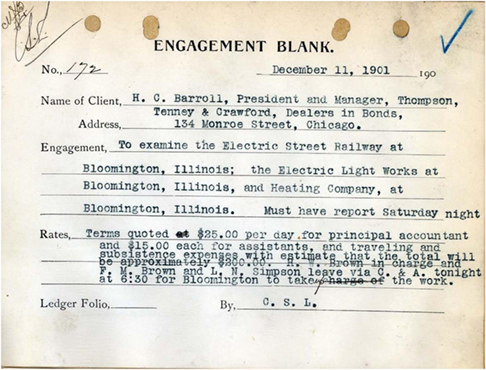

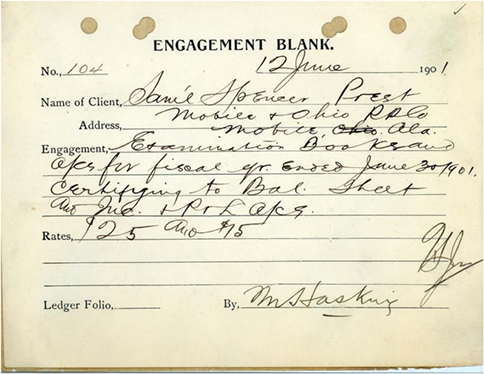

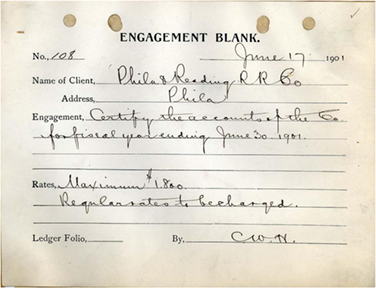

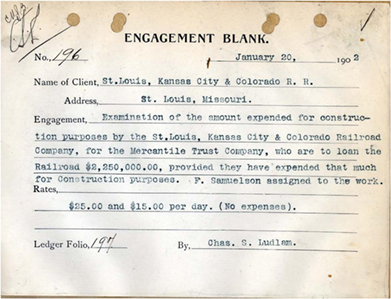

The letters in the H&S engagement book are numbered from 100 to 700. It contains 600 records of accounting engagements for clients during the period 1901 to 1903 (there is no number 101). These remarkable records are both handwritten (and, thus, varied in legibility) and typed. Appendix A lists the first 100 clients in the engagement book. Appendix B shows photocopies of examples of these records. Each has the engagement number and the date of the record, followed by the client identification. Under ‘engagement’ is an abbreviated note about the work to be done. The auditee is specified if different from the client, as is often the case. The rates quoted for the engagement are given. The record contains a place for ledger folio reference and the partner's initials (‘CWH’—Charles Waldo Haskins, ‘EWS’ Elijah Watt Sells). Other initials and names occasionally are given as the source of the entry. However, ‘EWS’ is the predominant engagement partner in the records. The provenance of this collection is outlined in Appendix D.

The first 100 engagement records reveal a diverse client practice. The importance of railroads as clients of H&S cannot be overstated. In the first 100 engagements from the engagement book, railroads made up 20%. Yet this percentage probably understates the railroad contribution to the practice because railroads would have been larger, more important clients and would have created larger fees given the number of hours involved and the complexity of the work. Significantly, railroad work caused H&S to seek out an experienced railroad accountant (Homer Adams Dunn) to help with this work. In addition to railroads, there were streetcar systems, banks, retail stores, manufacturers, city governments, and law partnerships. This variety of client activities may have challenged the H&S staff, as specialization by industry/client type was not yet a norm. The engagement work itself centred on audit/examination of accounts, accounting systems work, forensic (fraud) work, write-up work, and miscellaneous services, such as grading the City of Chicago civil service exam papers. The preponderance of activities seems to have been audit/examination of accounts type of work. In some of these engagements, a complete audit was done; in other cases, a more limited engagement was performed—a subsidiary, a particular office location or particular accounts, such that several engagements were less than full audits of all accounts. The engagements for audits or examination of accounts were often done at the request of a client who was an investor rather than at the request of the company being audited. Thus, a different attitude perhaps existed about who was the client in the audit situation from the attitude that exists 110 years later. Auditing for fraud seems to have been a relatively important part of the practice.

The H&S practice, even during this early period, had developed to include international engagements. The American Express work (#149) as well as several other engagements (#144, #143, #145, #146, and #148) were European assignments. H&S opened a London office in early 1901. The engagements reflect geographic diversity. Despite its office opening in New York City, the New York clients led to ‘out-of-town’ engagements, which in turn caused H&S to open offices in quick succession in Chicago (December 1900), London (April 1901), Cleveland, St Louis (1902), and Pittsburgh (1903). The firm spread to other US cities during the next decade.

The H&S engagement book notes the agreed-on fees for each engagement. The typical caption is that H&S would receive per day $25 for principals and $15 for staff. For partners, Elijah W. Sells, for example, the charge was $50 per day. The daily charge for accountants was increased to include travel costs for out-of-town engagements.

The H&S Railway Accountants' Contributions to the Profession

In addition to establishing a firm that is now a significant part of Deloitte, Charles Waldo Haskins' major professional contribution was his early and significant involvement in the passage of the New York law in 1896 that established a commission to examine CPA candidates for licensing. This became the prototype for legislation in other states for the CPA designation. He and his partner, Elijah Watt Sells, were a driving force behind the founding of the School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance at New York University, a pioneer program of teaching accounting at a university. In fact, Haskins not only taught accounting in this program, he was appointed the first Dean of the School (Previts and Merino, 1998, p. 199). Thus his contribution to accounting can certainly be seen today in CPA licensing and in the acceptance of accounting being taught at the university level.

Elijah Watts Sells' major contributions, in addition to establishing a firm, and his work on the reorganization of the Administrative Branch of government, include his work in having accounting accepted as a university-level subject, serving as the president in 1906–08 of the forerunner of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, his political activity aimed at government reform, his work and writings about cost accounting systems of manufacturers, and writing about corporate governance and financial accounting issues such as promoting the natural business year. His work also was aimed at world peace (Flesher et al., 1996, p. 259). He also worked with governments, for example, he helped modernize the Philippine governmental accounting system (Chatfield and Vangermeersch, 1996, p. 530).

Charles Stewart Ludlam worked on several railroad projects at H&S. Most notable were the reorganization of the St Louis Street railways and his work in support of railroads in Oklahoma rate cases, which had a broader, regional impact.

Homer Adams Dunn was widely respected as the best-grounded practitioner of his time. He was highly regarded as an original thinker and had a broad understanding of the various accounting and auditing methods. He wrote several papers on topics such as utility investor informational needs, railroad accounting and commerce regulation, and accounting methods for anthracite coal operators. Professionally, Dunn was active, including serving as vice president of the American Society of Public Accountants (1922–23), which subsequently merged with the AICPA) and in 1908 as the founding president of the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) (Flesher, 2007, p. 11).

Viewing the railroads as a going concern, any attempt to so classify the assets as to protect the interest of the investor must recognize a distinction between capital resources and those which are commonly regarded as current. The capital assets are those properties or belongings which are procured through capital expenditures and which are permanently or continuously needed in the business, such as right of way of the road-bed, rolling stock and equipment, buildings, machine shops, terminal properties, etc., etc. The purpose of procuring these properties is not that they may be sold at a profit, nor converted into cash as a means of meeting expenses or paying current liabilities. They are acquired for the purpose of using them in the business. Together they make up the working plant or business mechanisms by means of which the corporation is to obtain the income (Cleveland, 1906, p. 388).

This passage, which appeared in one of the earliest issues of the Journal of Accountancy, clearly relates the notion of going concern to railroad accounting and the manner by which assets of the railroad are to be valued, not at sale, market or liquidation values, but at a going concern value. The going concern value is the value that best evidences these assets as used in the ongoing and continuous process of providing railroad capacity. As such, this is an example of a ‘railroad paradigm’, which continues through to this day to serve as a basis for valuation consideration. The value of capital assets of a railroad as a going concern must have reference to maintenance and not to saleability or financial conversion into cash. This article also reflected advanced thinking about corporate governance issues.

Cleveland then went on to discuss the importance of depreciation expense recognition to maintaining capital, preventing excess dividends, distributions to shareholders at the suffering of bondholders, and the long-term operation of the railroad. He is specific in describing ‘wear and tear’ on railroad assets, suggesting steel rails have a useful life of 10 years before they must be replaced, pine ties have a five year useful life, wooden buildings have a 20 year life, while brick and stone buildings have a 50 year life. Cleveland then notes the importance of inspection by auditors of these long-lived properties to assure bond and stock investors that capital is being maintained (Cleveland, 1906, p. 389). He continued his urging of employment of an auditor by citing various manipulation practices that had been uncovered at the railroads of the period (Cleveland, 1906, p. 390–93).

Another View of Early Us Railway Audits?

Of one thing a proprietor may always be assured. If he becomes careless of his own obligation to those rendering honorable services, he may not expect those under him to apply the golden rule … When this personal contact is lost a stockholder who fails to provide a system which will give credit for integrity, cannot complain if he finds that his own interests have been sacrificed on the alter of graft (Cleveland, 1906, p. 393).

Evidence But Not Generalization

How widespread was the practice of railroad accountants becoming CPAs is a subject for future consideration. The evidence presented herein suggests that there is a broader pattern, but it is not yet sufficiently developed as a pattern to generalize further. It certainly was true at H&S, but did it extend to other firms as well? It appears likely that many other early CPAs also received their initial accounting training and experience while working for railroads. For example, Theodore Ernst, co-founder of Ernst and Ernst, had a railroad background. He worked for a railway for seven years prior to joining his brother in the Cleveland accounting practice. And, as noted above, Frederick S. Cleveland, who worked at H&S and wrote extensively about railroad accounting, is another CPA who contributed to this railroad era (Jobe and Flesher, 2005; Cleveland and Powell, 1909).

At Jones, Caesar, & Company, the American affiliate of the British Price Waterhouse, Charles J. Marrs was one of the firm's first hires when the firm began in 1895 (DeMond, 1951, p. 30). Marrs had worked for eight years at the Chicago, Milwaukee, & St Paul Railroad prior to being hired at Jones, Caesar, & Company. His railroad accounting knowledge was quickly utilized as his early years of a long career at the firm were on the accounts of several railroads. Shortly after Marrs' hiring, Jones Caesar began serving four railroad clients: the Mexican International Railroad; the Northern Pacific Railway; the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad; and the Louisville & Nashville Railway (DeMond, 1951, pp. 31–3).

All of the above railroad clients resulted from J.P. Morgan's request for audits. Morgan represented the bondholders and these railroads had experienced financial difficulties during the 1890s.

Peat, Marwick, Mitchell, and Co., formed in 1897 by two Scotsmen, also had early railroad clients, but a review of the firm history gives little indication of domestic railroad background among the early staff, since most of the staff were from Scotland. Yet, James Marwick and Roger Mitchell first met during the former's audit of the Fitchburg Railroad; Mitchell was an agent for his father's company in Fitchburg, MA (Wise, 1982, pp. 7–8).

Another luminary of this period, Homer St Clair Pace, a pioneer accounting educator and founder of Pace University, developed his accounting skills first serving the president of the Great Western Railroad of Chicago, and later, after moving to New York City in 1901, he became the railroad's corporate secretary. He co-founded the firm Pace & Pace in 1906, which developed into the international accounting firm of Pace, Gore, and McLaren by the late 1920s (Rabinowitz, 2004).

Conclusions and Research

This study provides evidence of a significant domestic talent sourcing relationship between railroad accounting work experience and entry into the early US public accounting profession at one of the then largest CPA firms. Most of the early partners and other employees at the turn-of-the-century H&S had significant US railroad experience. This experience led to the development of a major practice involving railroad clients, which was perhaps not surprising given the impact of railroads on the economy.

This paper presents important evidence that confirms that domestic US railroads were a major source of expertise that helped establish the nascent CPA profession, with respect to one major firm. It establishes a viable premise that accounting experience gained by early CPAs in that industry is a vital explanation as to the human resource development of accountancy in the US in this early period. The experience of working on the railroad, as well as the daily routine and standard of living, were relevant to the skills of CPAs. This seems especially true in the areas of auditing, systems, and forensic accounting. Also, as noted, the lifestyle and career path of railway accountants were conducive to the requirements for individuals with careers in public accounting.

However, future research is needed to broaden the scope of the study to more firms to strengthen the findings related herein and to further substantiate the domestic sourcing of early CPA talent. Further research about entities, such as the so called ‘most notable body of private accountants in the world’, the RAOA, a professional organization formed in the late nineteenth century, is needed to determine whether there are records about the type of training and education that may have been undertaken in the railway industry for accountants and auditors (H&S Reports, 1965, p. 22). Seemingly, railroad accountants and auditors learned primarily through on-the-job training, but this premise has not been examined.

With further research into sources, including early railroad publications such as Railway Age magazine, started in 1856 as the Western Railway Gazette, and similar industry sources, there is much to be learned about the practice of accounting in this industry. With further evidence, traditional generalizations and considerations about the sourcing of early US public accounting talent can be improved and possible alternative premises generated and evaluated.

Appendix A: H&S Engagement Book—First 100 Entries

| Engagement Number | Client | Type of Work |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | E.B. Patten & Co. | Audit of office accounts |

| 101 (Not found) | ||

| 102 | City of Atlanta | Audit |

| 103 | Federal Telephone | Special report setup books |

| *104 | Mobile & Ohio RR | Audit |

| 105 | Henry Weil—Cigar Co. | Audit |

| 106 | Cooley Credit Co. | Audit of Account |

| 107 | City of Chicago | Examination of special assessment accounts |

| *108 | Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Co. | Audit |

| 109 | US Rubber Co. | Audit |

| 110 | Realty Trust | Examine accounts of Southern Mfg. of Richmond business |

| 111 | Mercantile Trust | MC Wetmore Tobacco—contracts reviewed |

| *112 | Erie Railroad | Audit |

| 113 | John Dickey Gas Co. | Audit, Gas Co. (Augusta, GA) |

| 114 | Pioneer Cooperage Co. | Audit System Consulting |

| 115 | MC Wetmore Tobacco | Audit |

| 116 | Vassar College | Audit |

| 117 | Edwin V. Hall | Pass Book—(bank account) examination |

| 118 | Manhattan State Hospital | Audit statements & cash acct. |

| 119 | George Lawley & Son | Examination of Accounting System |

| 120 | US Rubber | Accounting Systems Installation |

| 121 | Westinghouse, Church Kerr, & Co. | Audit certain accounts |

| *122 | C&O Railroad | Audit |

| 123 | Cleveland Machine | Audit |

| 124 | American Trust | Audit |

| 125 | Joseph Hull—Prairie Pebble Phosphate | Audit Mfg. |

| 126 | Delaney & Delaney | Write-up work prepare financials |

| *127 | Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad | Audit of Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad |

| 128 | Just M. Stevedony Company | Audit |

| 129 | Universal Tobacco | Audit |

| 130 | Hudson River Stone Supply | Audit |

| 131 | Platt—Attorney—Estate | Estate Work |

| 132 | Electric Vehicle | Audit |

| *133 | St Louis & Chicago Railroad | Audit |

| 134 | Brown Bros. | Audit |

| 135 | John Muir & Co. | Audit |

| 136 | University of New York | Audit |

| *137 | Savannah Georgia Railroad | Audit |

| *138 | Savannah Georgia Railroad | System |

| *139 | Savannah Florida & Western Railroad | Bookkeeping |

| *140 | Savannah Georgia Railroad | Audit |

| *141 | Savannah Railroad | Audit |

| 142 | State of Missouri Bond Accounts | Audit |

| 143 | ‘The Artist’ Magazine (Europe) | Financial Investigation |

| 144 | Sanders Swann & Co. (Europe) | Audit |

| 145 | Quaker Oats (Europe) | Audit |

| 146 | Cuban Pan-American Express (Europe) | |

| 147 | John Martin | Law firm audit |

| 148 | Metropolitan District Electric Traction Co. (Europe) | Audit |

| 149 | American Express (Europe) | Audit |

| 150 | Robert Graves Co. | Audit |

| 151 | Cooley Credit | Audit |

| 152 | MM Cohen | System |

| 153 | Bank of Cuba in Havana | Examination (Audit) |

| 154 | Seullin & Gallagher Iron & Steel | Audit/System |

| 154 | Kansas & Texas Coal Co. | Audit |

| 155 | York Pitt Natural Gas | Examination (Audit) |

| 156 | M.J. Taylor | System/bookkeeping |

| 157 | United Cigar Co. | System/bookkeeping |

| 158 | Borden Condensed Milk | Audit investigation |

| 159 | Orlando Gregren Estate | Estate accounts |

| 160 | City of New Rochelle | Investigate city accounts |

| 161 | Presbyterian Hospital | Audit |

| 162 | Standard Typewriter | System |

| 163 | Payson Thomas | Write-up work |

| *164 | Worchester Webster Street Railway | Audit |

| 165 | Catholic Diocese | Examination/audit |

| 166 | E.C. Jones | Audit/Systems |

| 167 | City Club | Audit |

| 168 | National Ribbon Co. | Audit |

| *169 | Lake Shore Electric Railway | Audit of Cleveland Electric Railroad |

| *170 | Ulster & Delaware Railroad | Examine books (audit) |

| *171 | Chicago City Railway | Audit of property accounts |

| *172 | Electric Street Railway | Audit |

| 173 | Anthony Scovill Company | Systems |

| 174 | Haight Freese | Examine accounts (audit) |

| 175 | Schinasi Brothers | Write-up-prepare statements |

| 176 | United Telephone, Telegraph | Audit |

| 177 | St Joseph Light Heat Power | Examine accounts (audit) |

| 178 | Borden's Condense Milk | Examine accounts (audit) |

| *179 | New Orleans City Railroad | Audit |

| 180 | Osborn Flexible Conduit Co. | Audit |

| *181 | Everett-Moore Properties (telephone & electric railway) | Audit |

| 182 | Hyde Exploring Expedition | Examine accounts (audit) |

| 183 | Wilson Stevens | Audit |

| 184 | Provident Chemical Co. | Examination of accounts (audit) |

| 185 | Walker —handwriting | forgery—examine handwriting |

| 186 | Crude Rubber Co. | Bankruptcy—accounts/statements of revenue |

| 187 | Reynolds Tobacco Co. | Examine accounts (audit) |

| 188 | J. Ottimann Co. | Audit |

| 189 | Wm. Caldwell | Question of accounting |

| 190 | Lawrence Barnam | Audit |

| 191 | Manhattan Life Insurance | Audit of offices |

| 192 | Cassalt—Real Estate Trust | Audit of sand quarries |

| 193 | City of Chicago | Audit of Appropriations Bill |

| 194 | Union Trust Co. | Audit of accounts |

| 195 | City of Chicago | Marking Civil Service Exam Papers |

| *196 | St Louis, Kansas City & Colorado Railroad | Audit of construction accounts |

| 197 | Woman's Committee—NYU | Systems |

| 198 | Westinghouse Electric Mfg. Co. | Systems work |

| 199 | H.W. Palen's Sons | Set-up accounting system |

| 201 | Thomson Carmack |

*Indicates a railroad client.

Appendix C: First Ten Partners of Haskins & Sells

| Became | |

|---|---|

| Partner | |

| CHARLES W. HASKINS | 1895 |

| ELIJAH W. SELLS | 1895 |

| CHARLES S. LUDLAM | 1903 |

| HOMER A. DUNN | 1907 |

| DEROY S. FERO | 1907 |

| HOWARD B. COOK | 1910 |

| CHARLES E. MORRIS | 1910 |

| ARTHUR S. VAUGHAN | 1910 |

| DUDLEY C. MORRIS | 1910 |

| JOHN F. FORBES | 1912 |

Appendix D: Provenance of H&S Engagement Records

The history of the survival of 100-year-old records of H&S engagements reflects the dynamic circumstances of the US profession in recent years as well as the care and preservation instincts of members of H&S who were entrusted with these important proprietary documents. Rhea Tabakin, an employee of the firm who was the ultimate custodian of these significant documents, is certainly the reason that these records are now preserved and housed at the National Library of the Accounting Profession at the University of Mississippi, where they are available to other researchers.

Ms Tabakin, formerly senior manager of Integrated Services and Knowledge at Deloitte Services, the successor to H&S, recalls that the records were in the Deloitte, H&S library in the Executive Office at 42nd Street, New York City when she joined the firm in 1979. She believes the records came from the firm's Wall Street office when the office was split between the New York practice and the national headquarters. At the time when Deloitte, H&S merged with Touche Ross in 1989, the engagement records were in the 42nd Street library archive in the executive office. The merger led to the decision to send the old firm records to the record retention facility at Wilton, CT. Ms Tabakin thought the engagement file and the photos of the founders were too important to be stored in this manner, so she retained these items and shipped only the less historically significant records to Wilton.

The historically unique engagement book and founder photographs were in Ms Tabakin's desk on the 100th floor of the World Trade Center in 1993 when the bomb blast went off in the lower level parking garage. She retrieved these items a month later and stored them in her home for a year and then moved them into the new office at the World Financial Center.

A year or so later, Ms Tabakin's decision not to store these items at Wilton proved correct because, in 1995, the firm celebrated its 100th year anniversary and wanted to use historical documents stored at Wilton to write the history of Deloitte & Touche. None of the H&S materials that had been shipped for storage at Wilton could be located. It was decided by leading partners that the historical materials that were in Ms Tabakin's care should stay with her and not be transferred to Wilton, lest these be lost as well (Tabakin, 2003).

After discussions, but no final decision, the attack on the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 was the catalyst for the documents to be moved to a library archive where they could be better preserved and protected. At the time of the disaster, the engagement records were in Ms Tabakin's desk at the World Financial Center. After two months of not being able to get back into the building, one of the first things she did when she returned was to again take them home with her. She returned the records to her World Financial Center office later in the fall of 2001 when she felt safer. Ms Tabakin, now having gone through two bombings and lost records, approached a former H&S employee who was then consulting with the firm as to the legislative history of the profession. That individual, in turn, contacted a leading accounting historian in residence at the University of Mississippi to arrange for the H&S engagement book to be donated to the National Library of the Accounting Profession at the University of Mississippi where it could be preserved along with the AICPA's document collection. This transfer took place in the summer of 2004 when Tabakin convinced the firm's senior partners to allow the volume to be donated.

References

- 1 The signed letter of appointment is framed and on display in the Deloitte offices in New York City.

- 2 Thus, with the inclusion of Conant, the firm of H&S included three of the first 10 CPAs in America, since Haskins held certificate number six and Sells was issued certificate number 10. All were issued on the same date and the numbers were allocated in alphabetical order (Flesher et al., 1996).