Carbon Accounting: Challenges for Research in Management Control and Performance Measurement

Abstract

Carbon reduction programs and corporate emissions reporting have expanded rapidly across firms in response to climate change and global warming. This development is partly driven by institutional demands and partly by value creation considerations. The consequences of these developments for management accounting and control (MAC) are not clear, despite anecdotal evidence that suggests an increasing effort to incorporate carbon accounting into traditional decision and reporting processes. The reasons for this lack of clarity are the disproportionate focus in practice on carbon disclosure, compared to a small number of empirical studies, and the absence of an academic debate in this novel area from a MAC perspective. This paper seeks to stimulate such an academic debate by reviewing the extant literature, identifying key theoretical and empirical shortcomings of extant academic research, and outlining some directions for future studies on carbon accounting. These directions are inspired by more established MAC research that may help to guide and organize MAC research in the emerging and exciting field of carbon accounting.

Current regulatory and market-driven changes related to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are expected to have a major impact across a wide variety of industries. According to a survey of 202 carbon management experts in the United Kingdom, increasing oil and electricity prices, the hidden cost of carbon, growing risks from energy supply disruption and board-level climate change compliance issues make carbon management a new imperative for finance and accounting executives (Verdantix, 2010). A Canadian report shows that nearly half of the heavy carbon emitting Canadian firms claimed that their chief financial officer (CFO) is assuming greater responsibility in the development of carbon management programs (FEI, 2010). Aside from mandatory compliance, CFOs need to cope with rising investor demands for transparent and credible exposure to carbon levels and associated abatement costs (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2012). It seems CFOs will increasingly have to incorporate the assets, liabilities and risks associated with managing GHG emissions into traditional accounting, governance and control mechanisms (Deloitte, 2009; CIMA, 2010; Ernst & Young, 2010).

Increased GHG emissions disclosure represents an emerging imperative for many companies; however, there is a dearth of knowledge about their transition towards carbon management and their attempt to align it with management accounting and performance measurement systems (Ratnatunga and Balachandran, 2009). Moreover, there is scant evidence of the due technical process required and the effort that is expended by management accountants and financial managers in that regard. Although the aforementioned practitioner surveys suggest a large (potential) impact of carbon accounting in management accounting practices, the magnitude and direction of the impact is less obvious and provides a relevant and timely avenue for academic research.

In this paper we begin by reviewing current research in accounting journals that has developed around carbon accounting, carbon control and carbon disclosure. Rather than aiming for a comprehensive overview, we highlight issues that pertain to control and performance measurement. We then focus on the emergent area of carbon accounting from a management accounting and control (MAC) perspective, which is the appropriate domain for control and performance measurement research. Given the paucity of current (academic) studies with a MAC focus, the paper specifies the main empirical and theoretical challenges underlying this novel accounting area by positioning carbon accounting in six extant debates taking place in the MAC literature. Finally, specific directions for future research and their potential managerial implications are developed and discussed.

This commentary aims to contribute to the literature on carbon accounting in three ways. First, extant research examines carbon accounting by drawing upon different theoretical frameworks. We argue that a diversity of papers in this area is beneficial at this stage in order to increase our knowledge about the intended and unintended effects of carbon accounting and carbon markets. However, we propose that some form of organization of the extant literature may help streamline research paradigms. Second, the limited number of studies performed show important potential parallels with traditional MAC topics, such that carbon accounting may also inform traditional MAC debates. Our commentary attempts to link the emergent area of carbon control with fundamental theoretical and empirical issues that take place in the MAC literature. We intend to highlight similarities and differences that could be informative for both areas. Third, the paper provides concrete suggestions to foster research in a relatively unexplored area. In contrast to recent examples of financial accounting studies published in this area, research with a MAC focus is lacking. We indicate a selected number of research areas that could be fruitfully investigated with implications for theory development, as well as potential improvements to the practice of emissions measurement and control to support emission trading markets and other GHG emissions policies and programs.

Literature Review

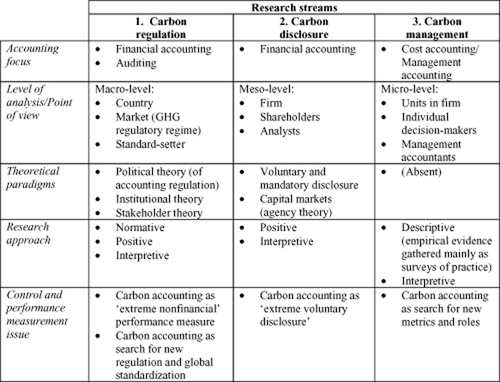

Research in accounting with an explicit focus on carbon accounting or carbon management is limited. There is, however, an increasing interest in this novel accounting area. Recent special issues on carbon accounting and reporting were published in Critical Perspectives in Accounting (Vol. 19, No. 4, 2008), the European Accounting Review (Vol. 17, No. 4, 2008), Accounting, Organizations and Society (Vol. 34, Nos 3–4, 2009) and Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (Vol. 24, No. 8, 2011). We present an overview of management studies that have addressed the antecedents and consequences of carbon accounting, and provide some insight into the accounting issues that pertain to control and performance measurement. For our overview, we propose that the literature can be broadly divided into three classes of studies. In Figure 1, we summarize the main features of each stream and we briefly comment on carbon regulation (stream 1), carbon disclosure (stream 2) and carbon management (stream 3) below.

Classification of Extant Carbon Accounting Literature

Carbon Regulation: Institutional Drivers of Carbon Accounting

As discussed in Kolk et al. (2008), carbon disclosure can be considered a form of ‘civil regulation’, a mode of corporate governance in which civil society actors employ information disclosure mechanisms to exert pressure on business to abide and comply with environmental and social norms. Establishing a carbon market requires a complex and bureaucratic infrastructure for the definition and measurement of carbon units for various activities, the allocation of emission rights, and the rules for carbon trading across national boundaries and different carbon jurisdictions (Kollmus, et al., 2010; Kossoy and Ambrosi, 2010; Young, 2010; Ratnatunga, et al., 2011). The artificial transformation of carbon from a negative externality into a commodity therefore requires a complex political process of institutionalization, which, in turn, tends to mask even more complex and much less understood technical measurement processes. A key success factor in such a process is ‘commensuration’, defined by Levin and Espeland (2002, p. 121) as ‘the transformation of qualitative relations into quantities on a common metric’. Mackenzie (2009a, 2009b) suggests that carbon information needs standardized units and measurement procedures or ‘metrology'—which is the science and technology of measurement. Such a metrological approach ensures that a quantity of gas measured at one place and at one time is sufficiently similar to the same quantity measured at a different place and time (MacKenzie, 2009a, p. 18). As GHG statements consist of predominantly nonfinancial information, which is subject to alternative choices in terms of reporting format and content (see also Bebbington and Larrinaga-Gonzalez, 2008; Olson, 2010), performance measurement challenges in terms of standard setting are abundant in comparison to more conventional accounting standards. We elaborate on some of these issues later in the paper.

In line with these arguments, a cluster of accounting studies focuses on the institutional and political context that characterizes current developments in carbon accounting. Some studies in the tradition of critical and sociological or the actor network theory perspective in accounting research comment on the creation of emission rights and carbon markets with an emphasis on the political decisions underlying these schemes (e.g., Callon, 2009; MacKenzie, 2009a). Other studies examine the role of standardization and the involvement of accounting standard bodies in setting up the bureaucracy of a carbon market. For instance, Cook (2009) reflects upon the policy mechanisms behind the standardization of carbon accounting. The paper explains how the initial attempt to promulgate a standard on GHG disclosure (IFRIC3) eventually failed. The main reason for withdrawal was the potential volatility arising from recognizing changes in the value of revalued emission rights allowances (intangible assets) in equity, while movements on the provision for emissions are recorded in the income statement. As a consequence, at the moment there is no authoritative guidance within International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) explicitly designed for transactions involving carbon allowances. Discussions are currently taking place within the International Accounting Standards Board to address this and related financial reporting issues concerning tradable emission rights and obligations under emission trading schemes. In the meantime, companies must interpret the existing standards (like IAS 2, 20, 37–39) and adapt them to their particular business model, strategy and transactions (cf. KPMG, 2008).

A similar void of authoritative guidance is currently affecting the provision of assurance services for GHG disclosure, as recently examined by Simnett et al. (2009). Their analysis develops around attempts to promulgate a GHG standard by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board after several meetings. Simnett et al. (2009) assess the type of disclosures that can be assured and discuss the challenges involved in the developments of an international assurance standard on GHG emission disclosures.

When reviewing the studies in this stream, the current approach is either descriptive or critical/normative. There is a lack of papers with a more positivist and theory-driven approach. Socio- and political economic theories (namely institutional and legitimacy theory) provide established theoretical frameworks that could be adapted in the area of carbon accounting and GHG disclosure (cf. Gray et al., 2010).

Studies published in the general management literature provide examples of theory-driven empirical research that could be imported to investigate antecedents of carbon accounting. Reid and Toffel (2009) draw on social movements and institutional change theories to explore how private and public political pressures can affect corporations' responses to shareholder activism. They argue that organizations will be more likely to acquiesce to external pressures if they, or other members of their institutional field, have been subjected to a formal shareholder resolution on a related topic. They further suggest that public politics moderates private politics by hypothesizing that organizations that face uncertain regulatory environments will be more willing to acquiesce to activist pressure. Using data from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) for US-based companies in 2006 and 2007, Reid and Toffel (2009) test these arguments in the context of climate change mitigation. They find that firms that have been targeted, and firms in industries in which other firms have been targeted by shareholder actions on environmental issues, are more likely to publicly disclose information to the CDP. In addition, they show that firms headquartered in states with proposed GHG regulations, which remain uncertain in terms of stringency and scope, are more likely than other firms to publicly disclose information to the CDP.

Three recent accounting studies that also address economic and institutional drivers of carbon disclosure are Cowen and Deegan (2011), Luo et al. (2012) and Stanny (2013). Cowen and Deegan (2011) investigate the chronological history of voluntary emissions reporting by Australian companies following the implementation period of the National Pollutant Inventory (NPI). Their findings confirm the reactive firms' responses to increased levels of disclosure, confirming the intuition of legitimacy and institutional theory of voluntary disclosure practices for pollution emissions of carbon monoxide and carbon disulfide. Luo et al. (2012) examine how Global 500 companies respond to the challenge of climate change and decide to voluntarily participate in the 2009 CDP. Companies facing direct economic consequences and those operating in GHG-intensive sectors are more likely to disclose. In addition, larger companies have a higher propensity for disclosing, suggesting that social pressure plays an important role. Stanny (2013) investigates the pattern of adoption of GHG disclosure for S&P 500 firms from 2006 to 2008. The disclosure patterns suggest that most firms' disclosures become routine practice once they begin to disclose, that is, they are ‘locked in’ in the provision of GHG emissions information for the years ahead.

Specific accounting-related research questions are topical for this area and require further investigation. For instance, it is still controversial whether GHG emissions disclosures should be mandated rather than remaining a firm's voluntary choice. As underscored by Cowen and Deegan (2011, p. 431) it is likely that GHG emissions disclosures will continue to be incomplete, inconsistent and lack comparability in the absence of mandatory disclosure requirements. Similarly, standard-setting policies may privilege standardization and international harmonization at the cost of differentiated regimes that could be better tailored to specific institutional and economic contexts. Finally, the integration of GHG emissions disclosure in IFRS provides an avenue for further research that could contribute to solving the various accounting dilemmas around the broader issue of reporting, assurance and valuation of nonfinancial information (cf. Olson, 2010).

Carbon Disclosure: Capital Market Drivers of Carbon Accounting

In contrast with the previous research area, the number of papers on carbon disclosure in financial accounting journals is growing rapidly. Carbon disclosure represents an extreme case of voluntary disclosure with all the measurement and behavioural questions and consequences that accompany the debate around this label (Berthelot et al., 2003; Clarkson, 2012; Clarkson et al., 2013). It combines features like forward-looking (e.g., announcing a plan to reduce GHG emissions), non-comparable (because there is no internationally agreed standard or authoritative guidance for benchmarking and measuring GHG emissions levels) and possibly unreliable disclosure (because in many cases the original disclosure is not subject to third-party verification or sanction). The main research question of interest for researchers in financial accounting is whether the disclosure of voluntary GHG information provides a signal to the capital market about how well a firm is managing its exposure to climate change risks. In line with this expectation, recent empirical evidence focuses on the relationship between specific carbon disclosure and firm value.

Hughes (2000) examines the association between sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions (formally not classified as a GHG) and the market value of equity using a sample of publicly traded electric utilities targeted as high-polluting by the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA). Hughes (2000) finds that the market penalizes the high-polluting utilities, but only during the years surrounding the enactment of the CAAA (1989–91). This is presumably the period in which the estimated future costs to comply with the CAAA were at their highest. The study finds no significant association between SO2 emissions and the market value of equity before 1989 or after 1991 for the high-polluting utilities.

Johnston et al. (2008) extend Hughes (2000) by examining the firm-value (as measured by market value) relevance of SO2 emissions allowances held by publicly traded U.S. electric utilities, which are subject to the emissions trading scheme put into place by the 1990 CAAA. Two components of the emissions allowances (an asset value and a real option value) that the authors argue are likely to be valued by the market are analyzed. Specifically, because the allowances do not expire, companies can purchase current vintage allowances and ‘bank’ them for future use. Thus, this allowance bank potentially reduces future cash outflows associated with emissions. Another mechanism to reduce future cash outflows is investing in scrubber technology, which provides a long-term positive effect in terms of reduced emissions. Consistent with their predictions, Johnston et al. (2008) find evidence that the market values SO2 emissions allowances as an asset, thus assigning a positive market price to them. They also find evidence that the market assigns a real option value to additional allowances purchased by the firm.

Instead of focusing on SO2 emissions, Chapple et al. (2013) examine the association between carbon (CO2) emissions and the market value of equity for a sample of publicly traded Australian firms, which, at the time of their study, were expected to be affected by a national Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) scheduled to start in 2011. Chapple et al. (2013) find that the market penalizes the firms that will be affected by the proposed ETS. Further, relative to less carbon-intensive firms, more carbon-intensive firms suffer a greater penalty, estimated at 6.57% of market capitalization. Matsumura et al. (2013) argue that prior research in financial accounting about environmental liabilities usually focused on liabilities either recognized on the balance sheet or disclosed in notes to the financial statements. In contrast, very little knowledge is available on off-balance sheet items. For this reason, focusing on carbon disclosure provides an opportunity to empirically test whether investors recognize liabilities that the accounting system does not recognize, and whether investors search for additional information outside financial statements and notes to assess a firm's liabilities. Therefore, Matsumura et al. (2013) examine the association between carbon emissions and the cost of capital components firm value by specifically disentangling the effects on cost of equity capital from the cost of debt (cf. also Dhaliwal et al., 2011). From the results of all the S&P 500 firms during 2006–08, the markets penalize all firms for carbon emissions, but a further penalty is imposed on firms that do not disclose emissions information.

While these studies adopt an economics-based perspective of carbon disclosure, alternative research paradigms in financial reporting could also provide fruitful insights (see Berthelot et al., 2003; Lee and Hutchison, 2005; Cho et al., 2012; Clarkson, 2012 for comprehensive literature reviews). For instance, Ertimur et al. (2010) address the issue of the credibility of voluntary GHG disclosure. They define credibility as a combination of comparability and verifiability. Two mechanisms that are argued to increase the credibility of voluntary environmental disclosures are participation in carbon disclosure programs such as the CDP and membership in market indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Together, these two commitment mechanisms work as legitimizing devices that are expected to positively influence investors. Ertimur et al. (2010) conclude that, while external commitment mechanisms can enhance the credibility of a firm's voluntary environmental disclosures, the efficacy of these mechanisms nevertheless depends on how the issue of comparability will be addressed in the coming years.

Overall, the growing interest in carbon accounting within mainstream financial accounting seems to classify GHG emissions disclosure as an extreme form of voluntary disclosure of nonfinancial information that could help test established theories of financial disclosure. While such a research stream provides a promising area for theory testing, we observe that this type of empirical research necessarily must rely on reliable and valid information about GHG disclosures. From several commentaries (Bebbington and Larrinaga-Gonzalez, 2008; Ertimur et al., 2010; Young, 2010), this seems not to be the case. In our opinion, there is a need to establish some solid foundations in this emergent area, starting from a more thorough understanding of internal mechanisms of carbon accounting. Before investigating capital market reactions to GHG emissions disclosure, it seems appropriate to examine how carbon accounting is deployed internally and how it relates to externally oriented accounting systems.

Carbon Management: Internal Drivers of Carbon Accounting

In the area of MAC, the issues identified by current carbon management studies mainly concern the questions of if and how firms will adapt their MAC systems internally to carbon management and carbon accounting. We define this stream as carbon measurement and controlling, even if the term ‘stream’ suggests a number of studies that vastly exceeds the extant studies actually available. Published studies within this perspective are, to the best of our knowledge, limited to papers by Ratnatunga (2007; 2008) and Ratnatunga and Balachandran (2009). These papers describe how carbon-related information could affect and control in various organizational areas (new product development, supply chain management, marketing and so forth). Basically, both papers are inventories of ‘could be’ statements with regard to this issue. For example, opinions collected from participants to 31 international environmental research symposia from 2003 to 2007 form the basis for judging the impact of the Kyoto Protocol on MAC in Ratnatunga and Balachandran (2009). In particular, they point to strategic cost management and strategic management accounting practices that may be affected by carbon accounting. In strategic cost management, carbon costing consists of a combination of advanced cost allocation techniques (like activity-based management and life-cycle costing) that improve the identification and assignments of carbon-related expenses and overheads to such objects as products, services, customers and organizational processes (Ratnatunga and Balachandran, 2009, p. 343). In strategic management accounting, issues are organized under general headings such as ‘business policy’, ‘human resource management’ and ‘marketing strategy’ (Ratnatunga and Balachandran, 2009, pp. 345–7).

These studies clearly point to the potential ramifications of the environmental debate in general, and issues related to carbon accounting specifically. However, the question remains as to whether the issues that are identified are conceptually and/or theoretically different from related challenges posed by autonomous developments in the management control arena. For example, the academic literature on Balanced Scorecards and similar methods used to measure the variety of nonfinancial drivers of firm performance already lists a multitude of challenges for contemporary management control. Luft (2009) discusses two important challenges in using combinations of accounting/financial and nonfinancial performance indicators, namely the accuracy of measuring nonfinancial performance and the appropriate weighting required to ensure balance across financial and nonfinancial measures. It is not clear per se why carbon accounting and GHG emissions indicators would pose additional challenges to those already identified.

In addition to these academic publications, the Chartered Institute for Management Accountants (CIMA) and Accounting for Sustainability (CIMA, 2010) conducted an international survey among sustainability professionals to investigate the role that climate change is having in shaping the management accounting profession. The survey highlights the potential beneficial effects of integrating carbon management in MAC systems, yet at the same time it documents that the diffusion of such practices appears to be limited. The survey provides an interesting inventory of the various reasons for, and obstacles against, the integration or even merging of environmental accounting and traditional accounting. Without much theoretical explanation, and without a specific focus on carbon accounting, the study documents that management accountants could have a role in areas such as carbon footprint calculation, tracking climate change performance measures/KPIs, preparing the business case for climate change initiatives and carbon accounting/budgeting.

In the absence of theory-driven studies in this area, further research seems warranted to examine the implications of carbon accounting on MAC.

Research Directions for Carbon Management Accounting and Control

The attention paid to carbon-related issues in the carbon management literature itself is limited, even if the contribution of management accounting research to the wider environmental management literature is broad (e.g., Epstein, 2008). There are a number of potential reasons for this lack of academic attention to MAC vis-à-vis carbon. The first can be found in the general reactive nature of the area of MAC research at large, in which there is little attention and appreciation of more pro-active research endeavours (such as ‘action research’, see Ahrens and Dent, 1998). The second can be found in the general emphasis on reporting issues that dominate the environmental and carbon accounting agenda, which seems to resonate better with the financial accounting literature. A third and more speculative reason acknowledges the assumption that extant practices in GHG emissions measurement present at least equivalent dilemmas comparable to other nonfinancial dimensions, such as occupational health and safety, reputation and corporate social responsibility, or community relations. Yet such an assertion has not been proved and it remains unclear whether carbon accounting generates new theoretical challenges to existing debates in management control and performance measurement theories.

In the remainder of this section, we expand our scope to the wider environmental management literature. We identify six potential streams for further MAC research in carbon and broader environmental accounting, which can be seen as specific opportunities for control and performance measurement research. For each of these directions, we briefly introduce the issues that dominate contemporary mainstream studies in the MAC field, we point to specific issues and potential pitfalls that may stem from an environmental management perspective, and discuss the viability and desirability of new MAC studies for each direction. We also discuss the extent to which these research directions are in need of new theoretical development given the specificities of carbon accounting. Figure 2 summarizes for each stream the main issues covered, together with theories and empirical methodologies potentially applicable.

Carbon Accounting Research Challenges for Management Control and Performance Measurement

Measurement Issues

The carbon accounting literature points to substantial difficulties and technical complications in defining and measuring GHG emissions (e.g., Milne and Grubnic, 2011). Indeed, the extant literature may not go far enough. There are also difficulties arising from the allocation of carbon emissions across geographic boundaries, across certain industries and within organizational boundaries. Goldsmith and Basak (2001) identify several limitations in the measurement of environmental performance indicators that apply to the measurement of GHG. First, since pollution is a dynamic problem, products, production processes and their associated pollutants change continuously, requiring metrics that can adapt to these changes. In addition, the cumulative effects of carbon dioxide may persist and build up over long periods of time. Second, hidden hazards are involved. The lack of observability for some pollutants, due either to improper auditing or to technological limitations of pollution measurement tools, can make GHG measures less reliable measures of ‘true’ environmental stewardship. Third, the subjectivity of carbon measurement remains problematic. Sampling costs (i.e., cheaper and less precise sampling procedures may be chosen), legal requirements depending upon regulatory schemes enforced by national governments, the environmental staff's current knowledge about environmental risk assessment and stakeholders' expectations may vary. Fourth, there is a problem of data aggregation. Measurement of carbon emissions consists of a series of measures collected over time, which tends to be aggregated into a single index or score (that may indeed reduce or ‘mask’ the complexities and issues contained in the source data itself). Finally, Goldsmith and Basak (2001) point to the problem of stochastic environmental events which is linked to the role of uncertainty in performance measurement, meaning that pollution output may be stochastic in nature and not entirely the result of direct or preventive management strategies.

Since, in an academic sense, evidence on GHG emissions measurement is still limited, accounting researchers could contribute to setting the foundations in this area by linking to two streams of study. The first stream of inquiry can be found in MAC studies on the broad debate of measurability of performance measures, particularly of nonfinancial information (see, for instance, Ittner and Larcker, 2001; 2003; Luft, 2009). In the extant MAC literature, measurability has at least two implications. From a cognitive psychology point of view, measurability relates to the characteristics of a certain performance metric. Here the issue is whether a certain measure is perceived as an appropriate measure for the characteristic or dimension that is supposed to be measured (construct validity). From an economic point of view the issue of measurability relates to the costliness of defining and measuring certain attributes and the relevance attributed to these attributes.

The managerial literature on nonfinancial information stresses the importance of such nonfinancial indicators in predicting future financial results. Best known as the ‘Balanced Scorecard Philosophy’, nonfinancial indicators are argued to be leading indicators of future financial performance. This philosophy emphasizes the functional effects of nonfinancial indicators as an effective antidote against managerial myopia, defined as a manager's dysfunctional inclination to only pay attention to the immediate rather than the distant future effects of his decisions. Clearly, the area of environmental performance in general and carbon accounting in particular is one area in which myopia may be prominent. This means that MAC studies may be inspired by the Balanced Scorecard literature in at least two ways. One is to understand better the cause-and-effect relationships between environmental (e.g., GHG emissions) performance indicators and financial performance measures. The debate taking place in the MAC literature on the ‘information content’ of nonfinancial performance measures such as customer satisfaction or operational efficiency could be expanded to include GHG emissions in the refinement of extant theoretical modelling and empirical specifications (Dikolli and Sedatole, 2007). Improving our understanding of the complex lead–lag relationships among GHG measures and financial performance would also be useful in practice to shift the attention of short-horizon managers towards the long-horizon interests of the firm in alignment with climate change mitigation strategies. Second, there is a need to understand how indicators potentially subject to all kinds of measurement problems and biases (Goldsmith and Basak, 2001) affect managerial decision-making. Environmental performance indicators and, moreover, carbon performance indicators can be perceived as an extreme form of nonfinancial performance measurement. However, if environmental regulation internalizes environmental performance of the firm, such as is potentially the case for carbon emissions, this provides an interesting opportunity to understand the trade-off between nonfinancials and financials (Luft, 2009). Indeed, as carbon emissions become a tradable commodity just like any of the other commodities that end up in the firm's profit and loss statement, the extent to which such performance indicators affect managerial decision-making becomes an empirical issue of prime importance. Even if carbon emissions become part of the traditional cost price and transfer pricing system, this does not immediately mean that their controllability mimics the controllability of ordinary commodities. Such controllability indeed requires a direct link between cost price and use of carbon emission rights.

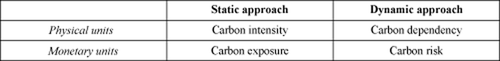

The second, related stream of research on measurement refers to research in environmental economics and industrial ecology that aims to define a consistent set of indicators able to appropriately capture the relation between a firm's carbon usage and its underlying business activities. For instance, recent papers by Hoffmann and Busch (2008) and Busch (2010) define four comprehensive and systematic corporate carbon performance indicators that differentiate between the physical (nonfinancial) and monetary (financial) dimension of performance, as well as current and future performance. The four dimensions are reproduced in Figure 3.

Corporate Carbon Performance Indicators

(Source: Hoffmann and Busch, 2008)

The framework they propose distinguishes a static nonfinancial measure of carbon intensity based on the physical carbon performance from a material flow perspective from a measure of carbon dependency that takes into account physical flows over time. On the financial side, they derive monetary implications of carbon intensity from a static perspective (labelled as carbon exposure) and a dynamic, long-term perspective (carbon risk). The examples provided by Hoffmann and Busch (2008,2008) across different sectors are exploratory and require further empirical testing and evidence that could be readily incorporated in future MAC studies on carbon accounting.

Under the heading of measurement, studies by Ratnatunga and Balachandran (2009) and Ratnatunga (2007, 2008) suggest that carbon accounting not only affects management control and performance measurement, but also the ‘costing’ and thus most of the traditional core areas of management accounting. As management accounting is firmly based on the idea of ‘different costs for different purposes’, it seems evident that the carbon agenda could impact costing principles, costing techniques and traditional costing problems. Yet, a closer analysis is needed to assess whether carbon accounting is not merely introducing new cost objects. If so, the question as to whether this provides any sort of challenge requires further theoretical and practical investigation.

Further, there is a growing amount of regulations and guidelines produced by government institutions that attempt to help operationalize and solve the technical challenges associated with GHG accounting. As one example, the Australian federal government has enacted the National Greenhouse Energy and Reporting Act (‘The NGER Act’). This scheme places mandatory reporting and, more importantly, measurement requirements on large emitting companies (Australian government 2007, 2008b). It was intended that the NGER Act would underpin any future emissions trading scheme with the necessary carbon emissions data. The role of the management accountant in interpreting and applying the vast volumes of measurement guidelines and determinations (see, e.g., Australian government, 2007, 2008a, 2008b, 2009) that have been produced as part of the NGER Act cannot be underestimated and provides a wealth of research opportunities. At the time of writing, despite a number of years of GHG measurement, control and data capture under the NGER scheme, academic literature exploring this from a MAC perspective has been quite limited.

Contracting and Incentives

The MAC literature pays ample attention to understanding the relationship between the use of nonfinancial information in the design of incentives schemes and managerial behaviour. An economics-based view and a psychology-based view can be distinguished on this issue. Economics-based studies, which are basically motivated by the principal–agent paradigm, point to the informativeness of nonfinancial indicators. According to the principal–agent paradigm, the informativeness of an indicator reflects the extent to which it is indicative of the agent's efforts towards value creation. This requires, at least, that the value production function of the firm is known.

In the area of GHG emissions and carbon accounting this value production function is not yet explicitly known, however in some jurisdictions it could be a function of the GHG emissions reduction targets set under an emissions trading regime and valued as the cost of trading carbon permits. This means that, in principle, the agency paradigm seems of little value to the explanation of certain management control arrangements in firms that include GHG emissions or other environmental performance indicators. However, current studies in financial accounting (see Berthelot et al., 2003; Dhaliwal et al., 2011; Clarkson, 2012; Matsumura et al., 2013) and general management (e.g., Dowell et al., 2000; Margolis and Walsh, 2001; Orlitzky, et al., 2003) that suggest a positive link between environmental performance (such as the management of GHG emissions) and firm financial performance may provide the grounds needed to apply agency thinking to environmental performance measurement. At a conceptual level, this link centres around the key property of performance measure congruity that is formulated in the economics (Baker, 2002) and accounting literature (Feltham and Xie, 1994; Datar et al., 2001). Congruent measures weight the various objectives that the agent (manager) pursues, according to the objectives of the organization. A consequence of using non-congruent measures is that a manager allocates his effort differently from what the organization would want the manager to do. As such, it is not just a matter of inducing the agent to expend effort, as principals want a manager to expend it in an appropriate direction. Congruity of environmental performance measures can hence be interpreted as the degree of congruence between the impact of an agent's action on environmental performance measures (like GHG emissions) and on the principal's payoff measured in terms of financial performance. In other words, environmental performance measures are more congruent (or less distortive in the terminology of Baker, 2002) when an agent's action that improves environmental performance also improves a firm's value. More precisely, what matters is not whether the measure is correlated with firm value, but whether the change on environmental performance measures covaries with the change in financial performance measures (Baker, 2002, p. 736).

MAC researchers could rely on a few analytical papers in environmental economics that explore principal–agent application and informativeness in the environmental area (see also Lothe et al., 1999; Lothe and Myrtveit, 2003). Gabel and Sinclair-Desgagné (1993) were the first to address the contractual aspects of managerial incentives to cope with the agency problems that potentially emerge with environmental-related decisions. They assume that top management aims at reducing environmental emissions or the possibility of an environmental accident, but the delegation of tasks and discretion to subordinates makes actual compliance uncertain. The research question they address is how should a chief executive officer link managerial compensation to performance with respect to environmental risk reduction. They present a multi-task principal–agent analytical model to assess the relevance of incentive pay linked to performance on environmental risk reduction. Their model assumes that: 1) the agent (i.e., the manager) does not have one but two tasks to perform, related either to the ‘standard’ task of enhancing the expected profit in conflict with the objective to reduce environmental risks; and 2) the agent has limited effort to split between the two tasks. Furthermore, it is posited that the principal cannot perfectly observe the extent of effort managers would allocate to the various tasks. One main analytical result presented in the article is that monetary incentives should become stronger as the principal becomes more eager to promote environmental risk-reducing activities relative to activities that enhance profit, and as the monitoring technology concerning environmental risk reduction becomes relatively more accurate. However, when total managerial effort reaches its peak, it might no longer be appropriate to make salaries vary with the observed reduction of environmental risk. Under these conditions, variable performance should only be based on financial performance measures.

In a subsequent paper, Sinclair-Desgagné and Gabel (1997) continue this line of research by focusing on optimal incentive structure in the presence of environmental audits. The analytical results prove that optimal wages after the introduction of an environmental audit should have a greater range than salaries paid when no audit has occurred. A second implication is that in this context the agent's allocation of effort is essentially determined by whether his prudence (i.e., the propensity to prepare and forearm oneself in the face of uncertainty) is stronger or weaker than his aversion to risk (i.e., how much one dislikes uncertainty and would turn away from uncertainty if possible). For instance, when prudence dominates, it is more beneficial to run an environmental audit if current profits are high and to offer the agent a larger expected salary each time an audit takes place. These theoretical expectations could be empirically investigated in the carbon accounting area, provided that researchers get access to reliable data about managerial contracts in which an explicit use of GHG indicators is used to evaluate and reward managerial performance.

Behavioural Effects of GHG and Carbon Performance Indicators

Another strand of MAC research, rooted in organizational behaviour and industrial psychology, examines the behavioural implications of incentive contracts and performance evaluation, focusing on the nature of performance indicators used. Luft (2009) provides a comprehensive overview of the issues surrounding nonfinancial measurement. Luft (2009) argues that the use of nonfinancial performance indicators is a field full of challenges. Among the benefits of nonfinancial information she documents that nonfinancial information answers the predictability of earnings and stock returns, and that the use of nonfinancial information is associated with increased learning. This is due to the fact that nonfinancial information provides a bridge between managerial action and financial returns. The introduction of nonfinancial measures seems to make managers aware of alternative task strategies that they may adopt to increase performance. Each of these issues provides an opportunity for research into carbon-related performance indicators. Indeed, Luft (2009) documents problems of nonfinancial indicators that are related to poor management or implementation.

Given the available evidence on the implementation of environmental management and measurement policies (e.g., CIMA, 2010), this provides a potential risk for the nonfinancial measurement associated with carbon policies. Luft's (2009) analysis points out an interesting path away from traditional discussions about the ‘accuracy’ or ‘reliability’ of performance indicators, and of their alleged ‘importance’. Instead, the choice for certain performance metrics should be related to the specific decision and should take into account the portfolio of available performance measures. One specific problem is related to the relative weighting of multiple indicators when they are used in (formal) performance-based compensation as well as in (informal) judgement and decision-making by managers in their day-to-day obligations. In this latter field, much evidence suggests that the way in which decision-makers interpret different informational cues might not be in line with the original intentions of the performance measurement system (Certo et al., 2008). This means that managers may be biased towards information that is irrelevant, distorted or that is judged to be incomparable across situations. This theme is part of a growing research stream on irrational decision-making, much of which is informed by Prospect Theory (Kanheman and Tversky, 1979). Studies in this field examine how decision-makers may overemphasize potential losses as compared to potential gains, and may show irrational and inconsistent preferences for the immediate and future outcomes of their decisions (Loewenstein and Prelec, 1992). Since many of the outcomes of carbon reduction policies have both immediate (i.e., cost increases) and future (i.e., sustainability) effects, understanding these potential biases will likely contribute to our understanding of the adoption of carbon accounting systems. Indeed, as such systems should align the behaviours of managers with their firm's strategies, they may be required to counter dysfunctional decision-making in the environmental arena, such as a manager's inclination to optimize the immediate future (i.e., cost reduction) at a cost to the distant future (i.e., increased environmental exposure). Such myopic behaviour is the focus of an increasing number of MAC studies (Laverty, 2004).

Measurement and Control of the Supply Chain

Just as companies tend to adapt their internal logistics operations before embarking on supply chain initiatives involving upstream suppliers and downstream customers, so carbon management is currently evolving from a company-specific activity into one involving the cooperation of companies at different levels in the supply chain. The Carbon Trust (2006) observed that many companies are traditionally quite inward-focused about energy consumption and carbon emissions but, following several pilot projects, found that there are additional opportunities to build influence, create knowledge, reduce carbon emissions and generate financial returns. The Carbon Trust has devised a methodology that companies collectively can use to measure CO2 emissions at each stage in a supply chain. This is largely based on techniques developed within the field of Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) to collect energy and emissions data, particularly for energy-intensive stages across the supply chain, construct a mass balance for the supply chain to ensure that all raw materials, waste, energy and emissions are accounted for, and calculate the carbon footprint of a product supply chain.

Carbon management represents another application in the MAC area that could be specifically linked to recent developments on management control in inter-firm relationships (cf. van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman, 2006; Vosselman and van der Meer-Kooistra, 2009). The main issue that could be examined revolves around the choice and effects of performance measurement systems to control GHG emissions along a firm's complex nexus of relationships with upstream suppliers and downstream customers. The contribution of MAC research would be particularly useful to address two practical problems that currently affect product-specific carbon accounting in supply chains. The first problem deals with the definition of boundaries in carbon emissions. The second problem refers to the allocation of carbon emissions (and related costs) across the various supply chain stages.

The GHG protocol differentiates three ‘scopes’, effectively drawing three boundaries around a business for carbon accounting and auditing purposes (WBCSD/World Resources Institute, 2004). Scope 1 emissions arise from activities for which the company is directly responsible, Scope 2 emissions are those indirect emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, heat and steam, while Scope 3 covers GHGs emitted by other businesses, such as third-party logistics, working on the company's behalf. Companies reporting their annual GHG emissions are required to quantify their Scopes 1 and 2 emissions but can exercise discretion over the inclusion of Scope 3 emissions. It is considered good practice for companies to include Scope 3 emissions in their carbon reporting as they are indirectly responsible for them. If they are excluded, companies can effectively reduce their corporate carbon footprint by outsourcing logistics activities. When collecting data for product-level carbon auditing, however, the inclusion of Scope 3 emissions for all the supply chain partners and their logistics providers will result in multiple counting, artificially inflating the total emissions allocated to a particular product (Hoffmann and Busch, 2008).

To minimize the risk of this occurring, corporate boundaries and related Scope 3 emissions must be clearly defined before the product-level auditing begins. However, deciding upon the start and end points for carbon measurement within the vertical supply chain is a controversial choice. If accepted practice in LCA were adopted, carbon emissions would be traced back to raw material sources or, in the case of recycled materials, the reprocessing point. Defining the end of the chain can be more problematic. To date, most of the carbon footprint pilot studies have assumed that the supply chain ends at the shop shelf. An increasing proportion of retail purchases are being made online and delivered to the home, yet effectively extending the chain to the point of use. Many LCAs also take account of resources expended and emissions released in the actual use of a product and its subsequent recycling or disposal. Including carbon emissions from these post-purchase activities in the footprint calculation would be fraught with difficulty given the variability of consumer travel behaviour, product usage and reverse logistics options (cf. McKinnon, 2010). However, ‘cradle to grave’ LCAs or ‘product road maps’ that consider use from primary producer through to consumers are gathering momentum in practice. Future academic research (by proponents of MAC) would assist in developing and refining further these efforts.

Another problem concerns the allocation of common and joint costs among different activities (transport, warehousing, consumption) along the various stages of a supply chain (‘cradle to cradle’; McDonough and Braungart, 2002). For example, where products share the same vehicles, warehouse space or handling equipment, the related energy consumption and emissions have to be allocated between them. Transport economists have long debated the allocation of common and joint costs between different consignments grouped on the same vehicle. The division of carbon emissions between consignments presents a similar analytical challenge. The greater the degree of disaggregation by consignment and even individual product, the more complex becomes this allocation problem, since the allocation could be determined by product weight, dimensions, handling characteristics or a combination of these criteria.

The complexity of defining boundaries and responsibility for assigning ownership of GHG emissions to either producer or consumer should not be taken lightly (Bastianoni et al., 2004; Archel et al., 2008; Young, 2010). Management accountants could contribute to the boundary and allocation debate in carbon accounting given their key role in the choice of performance measures and control systems in the supply chain. Dutta and Lawson (2008) describe a framework for incorporating carbon footprint into decision-making that emphasizes the role of value chain analysis. Future research at the interface of cost accounting, operations and supply chain management could shed light on improvements in measurement and the traceability of aggregated carbon emissions at corporate level as well as across the supply chain.

Role of Management Accounting Function/Controller

The CIMA (2010) study on the impact of management accounting on the environmental agenda opens up an interesting set of issues concerning the role of the financial management system and the management accountant. An important issue refers to who is ‘controlling’ the environmental agenda within the firm, and to what extent are traditional management accountants (or traditional management accounting activities) capable of addressing the challenges of carbon accounting. The CIMA (2010) study provides an interesting starting point for such an analysis. It documents that management accountants and environmental managers have different opinions, and not always optimistic expectations, about management accounting's potential to support environmental management with its traditional portfolio of tools (e.g., cost-benefit analysis, investment appraisal, Balanced Scorecard). Currently, there is no theory, let alone empirical evidence, to explain the extent to which environmental management goals and traditional firm goals are both supported via one integrated management accounting system (Perego and Hartmann, 2009).

In addition, research on carbon accounting could extend the debate on the role of the controller as either corporate policeman or business partner (e.g., Maas and Hartmann, 2010). With regard to the role of the controller, traditionally a distinction is made between two functions and there is an increasing interest in ethical issues and dilemmas that the combination of these functions may cause or aggravate. Hartmann and Maas (2010) examine, in particular, the extent to which various pressures in the controller's working environment do give rise to controllers' tendencies to manipulate performance data. Moreover, an area of further research in this regard could investigate the shift of roles and responsibilities for carbon accounting, management and control from environmental or production departments to financial or management accounting departments and why. In addition, an investigation into the merits of the rise in multi-disciplinary teams that characterizes the approach taken in practice by the Big 4 accountancy firms dedicated to carbon accounting would also be useful.

Carbon Accounting Information Systems

Commercially available accounting information systems (AIS) have evolved to the point where most include customized modules for environmental management. There are software packages available for hazardous materials inventory, environmental compliance activity documentation and more recently GHG accounting. A report published in 2009 estimates that approximately 60 companies worldwide offer GHG accounting software, and more than US$46 million was invested in GHG accounting software start-ups (Groom Energy Solutions, 2009). According to another report (Pike Research, 2010), the global market for GHG accounting software and support services grew by nearly 84% from 2008 to 2009, representing a total market of US$384 million. They predict that the market will achieve 40% compounded annual growth through to 2017. Australia's S2 intelligence reports that worldwide spending on green accounting systems will total US$595 billion through to 2015, including both GHG accounting software and environmental accounting software more broadly (S2 Intelligence, 2008).

Despite increasing evidence about companies' investments in carbon accounting, limited attention in the academic literature has been given so far to environmental information systems (Rikhardsson, 2001; Rikhardsson and Vedsø, 2002; Brown et al., 2005). Anecdotal evidence is available about the extent of the integration of environmental performance measures in AIS (Epstein, 1996; Reinhardt, 2000; Holliday et al., 2002). Richards et al. (2001) provide an early overview of the integration of AIS and environmental initiatives. For instance, Koehler (2001) describes the change in AIS that occurred in Baxter International to accommodate the managerial need for a more sophisticated environmental information system.

We argue that future research is therefore warranted on GHG accounting from an AIS perspective, provided that the quality and reliability of GHG information are necessary conditions to ensure managers take action and receive feedback consistent with a given corporate strategy of climate change mitigation. As a potential starting point, Shaft et al. (2002) examine how AIS can help an organization move towards environmentally responsive business practices. They identify a range of organizational information systems and discuss how these systems may support environmentally oriented decision-making. Similarly, Brown et al. (2005) develop a conceptual framework from the AIS literature that helps identify and frame environment-related information for operational and strategic decisions.

Another conceptual framework that could be readily applied to investigate carbon accounting refers to the dimensions underlying management accounting systems (MAS) developed by Chenhall and Morris (1986). Using a contingency-based approach to advanced manufacturing practices such as total quality management (e.g., Ittner and Larcker, 1995; Chenhall, 1997; Ittner and Larcker, 1997; Chong and Rundus, 2004; Van der Stede et al., 2006), just-in-time production (e.g., Sim and Killough, 1998; Fullerton and McWatters, 2002) and flexible manufacturing systems (e.g., Perera et al., 1997) have been investigated in association with MAS design. In a similar vein, researchers interested in carbon management could examine the relationships between a firm's environmental strategy of climate change mitigation and the characteristics (namely aggregation, broad scope, timeliness and integration) of its GHG accounting system (Perego and Hartmann, 2009). Such evidence would contribute to the literature that focuses on the fit between strategy and MAS (e.g., Abernethy and Guthrie, 1994; Chia, 1995; Bouwens and Abernethy, 2000; Chenhall, 2003).

Conclusion

In this paper, we aimed to provide an overview of extant studies in accounting that address the challenges of carbon accounting. In general, both academic journals and business practice tend to focus on external reporting and disclosure of carbon performance with little regard or a false assumption that MAC in this novel area is well developed. This overview has allowed us to discuss the current but limited number of studies in the area of carbon accounting that were performed from a specific MAC perspective. Moreover, given the many potential challenges to the MAC practice of carbon management, we identified six directions for future studies in carbon MAC. We further aimed to point to future directions for this literature by showing points of overlap and connection between carbon accounting issues and extant MAC research. Our analysis allows some generic and specific conclusions for these different aims.

Generally, we conclude that the environmental arena (and specifically GHG emissions) has rapidly become one of the most prominent arenas in which external, institutional settings have a potential effect on an organization's MAC treatments. This not only applies to basic measurement and costing techniques, but also to the extent to which firms should deal with internal issues, such as boundary-setting, internal transactions and the related problem of transfer pricing. Second, our analysis suggests that for each of the issues in which carbon accounting connects to extant individual studies and paradigms, these issues, without much exception, all belong to underdeveloped areas within the MAC literature itself. This applies especially to issues concerning the measurement of nonfinancial information and its use in incentive schemes. A third generic conclusion is that the body of theory supported by empirical evidence in MAC research on carbon accounting is extremely limited. An apparent reason for this lack of attention is the general reactive, rather than normative, nature of mainstream MAC research. In simple terms, one could argue that the amount of ‘extant practice’ when considering the GHG emissions data that has been accumulating, for example, with the mandatory trading scheme in Europe and the mandatory reporting scheme in Australia has been largely unexplored from a MAC perspective. Research opportunities seem abundant, or is it that pro-active MAC research strategies have lost momentum over the last decade? This provides a stark contrast with other literature streams (i.e., carbon regulation and carbon disclosure) on carbon accounting that we have identified, which are for a great part normative, and which, for the extent that they rely on theory, are concerned with carbon accounting issues that do have sufficient ‘extant practice’ because of current disclosure data. Fourth, and finally, we argue that the attention of MAC studies to carbon management will provide researchers with some tough challenges that already affect the current MAC paradigm. Carbon accounting could easily be seen as referring to an ‘extreme’ nonfinancial performance measurement system, with all the measurement and behavioural questions and consequences that accompany the debate around this label. In this sense the Balanced Scorecard literature shows the pitfalls of trying to understand the relationships between nonfinancial and financial performance. Discussion on the potential role of value measures (like economic profit) may provide insights into the relationships between carbon disclosure and value creation, for which even traditional studies have not fully included the MAC consequences. This means that, even though the institutional environment may be ready to repackage carbon and GHG emissions as marketable assets, managerial treatment may not be straightforward.