Intraoperative opioid administrations, rescue doses in the post-anaesthesia care unit and clinician-perceived factors for dose adjustments in adults: A Danish nationwide survey

Abstract

Background

The impact of demographic- and surgical factors on individual perioperative opioid requirements is not fully understood. Anaesthesia personnel adjust opioid administrations based on their own clinical experience, expert opinions and local guidelines. This survey aimed to assess the current practice of anaesthesia personnel regarding intraoperative opioid treatment for postoperative analgesia and rescue opioid dosing strategies in the post-anaesthesia care unit in Denmark.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey with 37 questions addressing pain management and opioid-dosing strategies. Local site investigators from 46 of 47 public Danish anaesthesia departments distributed the survey. Data collection took place from 5 February to 30 April 2024.

Results

Of the 4187 survey participants, 2025 (48%) answered. Intra- and postoperative opioid doses were adjusted based on chronic pain, age, preoperative opioid use, body weight and type of surgery. Between 84% and 89% of respondents adhered to and had perioperative pain management guidelines available. Respondents preferred intraoperative fentanyl (44%) and morphine (36%) to prevent postoperative pain. Median intraoperative intravenous morphine equivalents ranged from 0.12 to 0.38 mg/kg in clinical scenarios. In these cases, the following variables were assembled in different combinations to assess their impact on dosing: age (30 vs. 65 years), sex (female vs. male), ASA score (1 vs. 3) and type of surgery (anterior cruciate ligament vs. laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery). Respondents preferred intravenous morphine and fentanyl for moderate and severe postoperative pain, respectively. Median postoperative rescue doses were 0.06–0.12 mg/kg in clinical scenarios based on shifting combinations of the variables: age (30 vs. 65 years), ASA score (1 vs. 3) and degree of expected pain (moderate vs. severe).

Conclusion

Respondents preferred fentanyl and morphine for postoperative pain control with considerable variation in choice of opioid and morphine equivalent dose. Respondents expressed that guidelines were highly available and strongly adhered to. Opioid dosing was predominantly guided by chronic pain, age, preoperative opioid use, body weight and type of surgery.

Editorial Comment

This nationwide Danish survey provides insight into current perioperative opioid practices in Denmark, revealing a strong adherence to guidelines yet substantial variation in dosing strategies. Factors such as age, chronic pain and surgical type influence opioid administration. Similar to most practices worldwide, most anesthesiologists/nurse anaesthetists preferred fentanyl and morphine in the intraoperative period.

1 INTRODUCTION

Opioids play an important role in perioperative pain management, both as a key component of multimodal analgesia and as the first-line treatment for patients experiencing postoperative breakthrough pain.1, 2 The use of opioids must be carefully balanced to ensure adequate analgesia while minimising the risk of opioid-related adverse events (ORADEs).3-7 Although equipotent doses of various opioids may offer similar levels of analgesia and adverse event profiles, each opioid has unique pharmacodynamic properties. These properties may make certain opioids more or less appropriate for different surgical populations or specific phases of the intra- and postoperative course.8, 9

There is limited evidence regarding the impact of demographic- and surgical factors on individual opioid requirements during recovery, specifically at the end of surgery and in the post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU).10, 11 No evidence-based guidelines currently exist on how factors such as age, sex, co-morbidities, chronic pain and other relevant factors should influence the titration of perioperative opioids.11-16 Therefore, anaesthesia personnel must rely on personal clinical experience, expert opinions and local guidelines.10, 11, 17 This reliance can lead to significant inter-provider variation in the administration of opioid doses, even among otherwise homogenous surgical patient populations.

Current research has predominantly focused on procedure-specific pain management and optimisation of opioid-sparing multimodal analgesia.5, 18-22 However, there is a lack of evidence concerning the individual preferences of anaesthesia personnel regarding perioperative pain management with opioids. In this Danish nationwide survey, we aimed to assess current practices in intraoperative opioid administrations for postoperative pain management, the use of rescue opioids in the PACU and the factors considered by anaesthesia personnel when adjusting intra- and postoperative opioid doses.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design, approvals and consent

The manuscript was prepared according to the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS)23 (Appendix 1) and conducted via the secure web application Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN, USA)24 hosted by the Capital Region of Denmark. The study was registered in the controller's (the Capital Region of Denmark) record of processing activities (reference no: p-2023-15040, approved 5 December 2023). Ethical approval was unnecessary as no patient data were collected, and participants were anonymous. A protocol was uploaded to https://opiaid.dk/survey before the survey activation (9 January 2024). Informed consent from participants was obtained as the first item of the questionnaire.

2.2 Population

All anaesthesiologists, nurse anaesthetists and post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) nurses who are involved in the perioperative management of adult patients within the Danish public hospital system.

2.3 Danish healthcare and organisation

The Danish healthcare system provides free healthcare services to approximately six million residents25 distributed across five regions, which collectively house 47 public anaesthesia departments. According to self-reported departmental employee records for 2024, 1699 anaesthesiologists, 1196 nurse anaesthetists and 1292 PACU nurses are employed across the departments. In Denmark, nurse anaesthetists are responsible for maintenance and intraoperative analgesic administrations in collaboration with anaesthesiologists. See Appendix 2 for additional details regarding anaesthesia education in Denmark.

2.4 Survey design

This cross-sectional survey consisted of 37 questions sub-grouped into four sections: demographics, pain management guidelines, intra- and postoperative opioid management practices in different clinical scenarios (Appendix 3). Anaesthesiologists answered both intra- and postoperative questions. Nurse anaesthetists were only presented with questions regarding the intraoperative phase, and PACU nurses were only presented with questions regarding the postoperative phase. Respondents could exit the survey before completion, resulting in section-specific missing data. The survey was pilot-tested by anaesthesia personnel at three different hospitals from 29 September 2023 to 29 January 2024 (Appendix 2).

2.4.1 Section 1: Demographic data

Participants were asked six questions on their clinical background, seniority in their position, hospital and departmental affiliation, and the surgical specialities they provide anaesthesia for.

2.4.2 Section 2: Guidelines for intra- and postoperative pain management

Eight questions related to surgery, such as the availability of local written instructions, degree of adherence to guidelines and specific patient groups, were included in the guidelines. Respondents were asked to categorise their guidelines as general or procedure-specific, while more specific content of guidelines was outside the scope of this survey.

2.4.3 Section 3: Intraoperative practice

Thirteen questions were asked about preferred opioids, patient factors affecting dose adjustments and chosen doses in four predefined clinical cases. The cases were designed to assess specific demographic- or surgical factors to evaluate their impact on opioid dosage practices. Regional anaesthesia was not considered an option in the cases.

2.4.4 Section 4: Postoperative practice

Ten questions were asked about opioid titration strategies in the PACU, including five predefined clinical scenarios on opioid rescue dosing strategies. PACU nurses were further asked to grade the impact of pain and ORADEs on patient recovery.

Clinical cases (sections 3 and 4)

For all cases, acetaminophen, NSAID and dexamethasone 16 mg intravenous (i.v.) were administered; general anaesthesia was maintained with propofol and remifentanil; the patient had declined peripheral or neuraxial blocks, had a normal renal function, no allergies or contraindications to opioids or no history of severe opioid-related side effects.

The intraoperative clinical cases were designed to isolate higher age and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, female sex, lower weight and type of surgery (anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and laparoscopic cholecystectomy) to investigate their impact on opioid dosing strategies.

Intraoperative cases: Which opioid and what dose do you administer at the end of surgery (40–60 min before the expected end of surgery)?

- 30-year-old male, 180 cm, 80 kg, ASA 1, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

- 80-year-old male, 180 cm, 80 kg, ASA 3, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

- 30-year-old male, 180 cm, 80 kg, ASA 1, laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

- 30-year-old female, 180 cm, 60 kg, ASA 1, laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Postoperative cases: Which opioid and what dose do you administer 30 min after PACU arrival?

- 30-year-old ASA 1 patient weighing 80 kg with moderate postoperative pain (NRS 4–7).

- 65-year-old frail ASA 3 patient weighing 80 kg with moderate postoperative pain (NRS 4–7).

- 30-year-old ASA 1 patient weighing 80 kg with severe postoperative pain (NRS 8–10).

- 65-year-old frail ASA 3 patient weighing 80 kg with severe postoperative pain (NRS 8–10).

- Young patient, 80 kg, NRS 5, received 5 mg i.v. morphine. No pain relief was experienced during the initial rescue 20 min after administration. Do you administer more morphine or switch to another drug?

2.5 Survey distribution

The site participation rate was 98% (46 of 47 sites). At each site, a designated local representative was responsible for identifying eligible participants, distributing the survey via email with an online link and sending at least three reminder emails. Before survey activation, site investigators received a brief study protocol, a demo version of the survey and a project video presentation (https://opiaid.dk) from the coordinating site. Each site investigator also provided a list of the total number of invited participants from each profession, which was used to calculate the overall and profession-specific response rates. The survey was open for data collection from 5 February to 30 April 2024, with a minimum of three reminders sent to all participating sites before survey closure.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages followed by nominator and denominator and continuous as either mean (95% confidence intervals [CI]) or median (IQR), depending on the distribution of data. Additional details are presented in the full statistical analysis report (Appendix 4). The anaesthesia personnel's specific choice of opioids and doses were presented along with conversion values into i.v. morphine equivalents (MEQ)/kg using the opioid conversion26 presented in Appendix 2. Missingness was reported for each survey section. All analyses were conducted as complete case analyses without imputation. We used a convenience sample with no formal sample size estimation and did not use any measures to adjust for non-representativeness in the survey sample. Data were handled and analysed using R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).27

3 RESULTS

3.1 Response rates and demographics

We invited 4187 anaesthesia personnel to participate, of whom 2850 accessed the survey link. Among these, 2025 answered at least one clinical question, defining them as the overall respondents. The overall response rate was 48%, with a median site response rate of 50% (IQR 43–63) (Appendix 2). The geographical distribution is detailed in Table 1.

| Overall respondents n = 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | Serviced surgical specialties | ||

| Nurse anaesthetist | 797 (39%) | Abdominal surgery | 1421 (70%) |

| Anaesthesiologist | 665 (33%) | Gynaecology/obstetrics | 1160 (57%) |

| PACU nurse | 563 (28%) | Vascular surgery | 323 (16%) |

| Region | Breast surgery | 379 (19%) | |

| Region Hovedstaden | 662 (33%) | Neurosurgery | 176 (9%) |

| Region Midtjylland | 510 (25%) | Orthopaedics | 1487 (73%) |

| Region Nordjylland | 210 (10%) | Plastic surgery | 398 (20%) |

| Region Sjælland | 299 (15%) | Paediatrics | 902 (45%) |

| Region Syddanmark | 344 (17%) | Cardiothoracic surgery | 213 (11%) |

| Experience in years | Urology | 724 (36%) | |

| Median [IQR] | 11 [4;20] | Otolaryngology | 673 (33%) |

| Other | 177 (9%) | ||

- Abbreviation: PACU, post-anaesthesia care unit.

When stratified by profession, the response rates were 56% (665/1196) for anaesthesiologists, 47% (797/1699) for nurse anaesthetists and 44% (563/1292) for PACU nurses. The respondents pool consisted of 33% (665/2025) anaesthesiologists, 39% (797/2025) nurse anaesthetists and 28% (563/2025) PACU nurses (Table 1). The median anaesthesia-related work experience was 12 years (IQR 5–20) for anaesthesiologists, 13 years (IQR 5–20) for nurse anaesthetists and 7 years (IQR 2.5–16) for PACU nurses (Appendix 4). The respondents most frequently provided anaesthesia and pain management to orthopaedic-, abdominal- and/or gynaecology-obstetric patients (Table 1).

Proportionate missingness for each of the 37 questions ranged between 0% and 22% (see Appendix 2 for further details).

3.2 Guidelines for intraoperative pain management

Intraoperative guidelines for pain management were reported to be available by 89% (1304/1460) of respondents. Guidelines were followed ‘often’ or ‘always’ by 84% (1108/1320) and mainly consisted of combined general and procedure-specific recommendations (Table 2). Guidelines were deemed to cover individual analgesic needs to an ‘acceptable’, ‘good’ or ‘really good’ degree by 65% (824/1260) of the respondents, with specific recommendations for chronic pain (38%), kidney insufficiency (15%), age (13%) and substance abuse (11%). Factors less commonly covered in the guidelines included body weight (8%), comorbidities in general (6%), cancer (4%), alcohol abuse (4%) and dementia (1%) (Appendix 4).

| Overall responses: n = 1462 (anaesthesiologists 665 [46%], nurse anaesthetists 797 [54%]) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Which opioids do you prefer to use intraoperatively? | |||

| First choice | Second choice | Third choice | |

| Fentanyl | 643 (44%) | 482 (33%) | 196 (13%) |

| Morphine | 519 (36%) | 378 (26%) | 223 (15%) |

| Sufentanil | 167 (11%) | 195 (13%) | 141 (10%) |

| Oxycodone | 113 (8%) | 163 (11%) | 417 (29%) |

| Methadone | 2 (0%) | 99 (7%) | 269 (18%) |

| Alfentanil | 1 (0%) | 81 (6%) | 76 (5%) |

| Other | 15 (1%) | 53 (4%) | 113 (8%) |

| Ketogan | 0 (0%) | 8 (0%) | 22 (2%) |

| Intraoperative guidelines are: | |

|---|---|

| General and procedure-specific guidelines | 810 (55%) |

| Only general guidelines | 271 (19%) |

| Only procedure-specific guidelines | 223 (15%) |

| Neither general nor procedure-specific guidelines | 58 (4%) |

| I am not aware | 98 (7%) |

| Do you adhere to these guidelines? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| 1% (n = 14) | 2% (n = 23) | 13% (n = 175) | 70% (n = 928) | 14% (n = 180) |

| To what degree does these guidelines account for individual variation in opioid requirements: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bad | Less good | Acceptable | Good | Really good |

| 7% (n = 86) | 28% (n = 350) | 38% (n = 480) | 23% (n = 298) | 4% (n = 46) |

- Note: The two most frequent responses are highlighted for each category. The proportion of missing responses for specific questions was 0–202 (0%–14%). Fifty-nine answered ‘do not know’ regarding individual variation.

3.3 Guidelines for postoperative pain management

Postoperative guidelines for pain management were reported to be available by 88% (1024/1159) of respondents. Guidelines were followed ‘often’ or ‘always’ by 88% (910/1038) and mainly consisted of combined general and procedure-specific recommendations (Table 3). Guidelines were deemed to cover individual analgesic needs to an ‘acceptable’, ‘good’ or ‘really good’ degree by 74% (730/992) of respondents, with specific recommendations for chronic pain (42%), kidney insufficiency (30%), acute surgery (33%), age (24%), substance abuse (13%) and body weight (10%). Less common factors included in the guidelines were comorbidities in general (6%), alcohol abuse (5%), cancer (5%) and dementia (2%) (Appendix 4).

| Overall responses: n = 1159 (anaesthesiologists 596 [51%], PACU nurses 563 [49%]) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Which rescue opioids do you administer to moderate pain; severe pain; and severe pain and nausea? | |||

| Moderate pain, no ORADEs | Severe pain, no ORADEs | Severe pain + severe nausea | |

| Morphine i.v. | 621 (54%) | 361 (31%) | 123 (11%) |

| Morphine p.o. | 65 (6%) | 5 (0%) | 3 (0%) |

| Fentanyl i.v. | 217 (19%) | 406 (35%) | 349 (30%) |

| Oxycodone i.v. | 91 (8%) | 83 (7%) | 331 (29%) |

| Oxycodone p.o. | 17 (2%) | 1 (0%) | 11 (1%) |

| Sufentanil i.v. | 80 (7%) | 95 (8%) | 84 (7%) |

| Alfentanil i.v. | 4 (0%) | 98 (9%) | 50 (4%) |

| Combined opioids | 46 (4%) | 89 (8%) | 77 (7%) |

| Methadone p.o. | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) |

| Ketogan p.o. | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (0%) |

| Other | 12 (1%) | 14 (1%) | 58 (5%) |

| No more opioids | 54 (5%) | ||

| Postoperative guidelines are: | |

|---|---|

| General and procedure-specific guidelines | 577 (50%) |

| Only general guidelines | 384 (33%) |

| Only procedure-specific guidelines | 63 (5%) |

| Neither general nor procedure-specific guidelines | 22 (2%) |

| I am not aware | 113 (10%) |

| Do you adhere to these guidelines? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| 0% (n = 5) | 2% (n = 20) | 10% (n = 103) | 67% (n = 689) | 21% (n = 221) |

| To what degree does these guidelines account for individual variation in opioid requirements: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bad | Less good | Acceptable | Good | Really good |

| 6% (n = 64) | 20% (n = 198) | 39% (n = 384) | 27% (n = 272) | 8% (n = 74) |

- Note: The two most frequent responses are highlighted for each category, The proportion of missing responses for specific questions was 0–122 (0%–14%). Forty-five answered ‘do not know’ regarding individual variation.

- Abbreviation: ORADEs, opioid-related adverse events.

3.4 Intraoperative opioid administration strategies

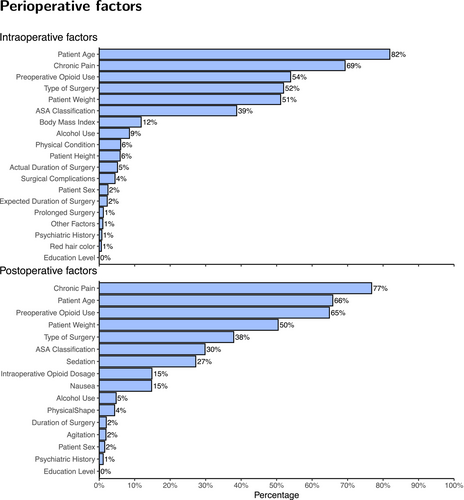

The preferred intraoperative opioids for postoperative analgesia were fentanyl (44%; 643/1460) and morphine (36%; 519/1460) (Table 2). The most important factors in intraoperative opioid dose adjustment were deemed to be age (82%), chronic pain (69%), pre-operative opioid use (54%), type of surgery (52%) and body weight (51%) (Figure 1).

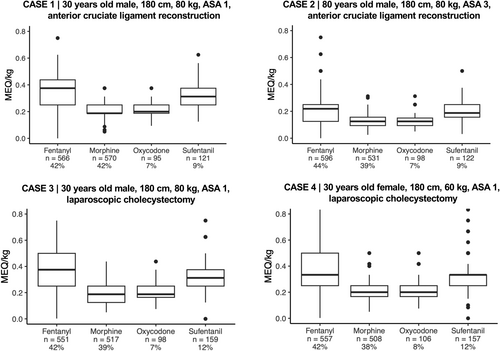

In the four intraoperative cases (variables: 30 or 65 years old; male or female; ASA score 1 or 3; anterior cruciate ligament- or laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery), the median intraoperative opioid doses for postoperative analgesia ranged from 0.12 to 0.38 mg i.v. MEQ/kg (Figure 2). Overall, fentanyl and morphine were the most preferred opioids. Among those who preferred fentanyl, 72% (407/568) initiated the treatment during or shortly after induction and subsequently titrated dosages during surgery to provide both intra- and postoperative analgesia (Appendix 4). Median MEQ/kg doses were consistently higher for fentanyl, followed by sufentanil, oxycodone and lastly, morphine (Figure 2). MEQ/kg doses were comparable between sex and type of surgery (cholecystectomy or anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction) while being elderly or ASA 3 would lead to a dose reduction (Figure 2). This pattern was consistent regardless of which opioid respondents chose. The interquartile ranges (25-75%) of chosen doses were between 10.4 and 15.2 mg, which reflects a large inter-clinician variability in preferred opioid dosages for patients with identical baseline characteristics and surgical procedures.

3.5 Postoperative opioid administration strategies

Respondents selected the four most important factors for dose adjustments in the postoperative setting, which were chronic pain (77%), age (66%), preoperative opioid use (65%), body weight (50%) and type of surgery (38%) (Figure 1).

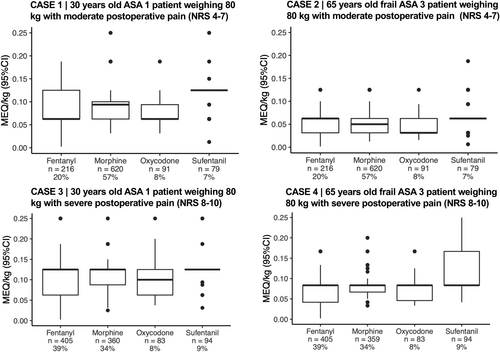

In all postoperative cases (variables: 30 or 65 years old; male or female; ASA score 1 or 3; moderate or severe pain), morphine i.v. was the preferred rescue opioid for patients with moderate postoperative pain (NRS 4–7), whereas fentanyl i.v. was preferred for patients with severe pain (NRS 8–10) (Table 3, Figure 3). MEQ/kg doses were highest for respondents using sufentanil, followed by oxycodone, morphine, and fentanyl.

When assessing all opioids, young, healthy patients would receive a median of 0.09 mg i.v. MEQ/kg (IQR 0.06–0.12) for moderate pain and 0.12 mg MEQ/kg (IQR 0.06–0.12) for severe pain (postoperative cases 1 and 3). If the patient was elderly and classified as ASA 3, median doses were reduced to 0.06 mg MEQ/kg (IQR 0.03–0.06) for moderate pain and 0.08 mg MEQ/kg (IQR 0.06–0.08) for severe pain (postoperative case 2 and 4; Appendix 4). Lastly, in a young, healthy patient with moderate pain who had received an initial rescue morphine dose and experienced no pain relief after 20 min, 81% (926/1148) would administer more morphine immediately, 9% (103/1148) would administer another opioid immediately, 9% (101/1148) would wait another 10 min and 1% (11/1148) would wait another 20 min (postoperative case 5).

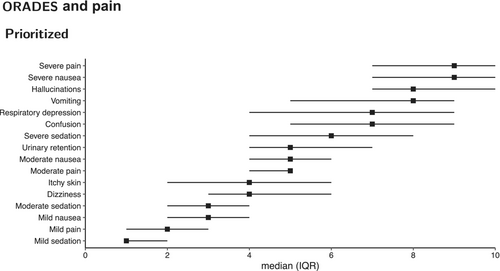

3.6 Impact of pain and ORADEs

When scoring the negative impact on the recovery of pain and ORADEs (0–10 numeric rating scale), PACU nurses considered the most important factors to be severe pain (NRS 9; IQR 7–10), severe nausea (NRS 9; IQR 7–10), hallucinations (NRS 8; IQR 7–10) and vomiting (NRS 8; IQR 5–9) (Figure 4). Similar severity degrees of pain and nausea (mild, moderate or severe) were regarded to have a similar negative impact on patient recovery.

4 DISCUSSION

In this nationwide Danish survey of anaesthesia personnel, we assessed intra- and postoperative opioid treatment strategies for analgesia during recovery in PACU. We found a high availability of and adherence to pain management guidelines. The most significant factors influencing opioid dose adjustments were chronic pain, age, preoperative opioid use, body weight and type of surgery. Fentanyl and morphine were the most preferred opioids for intraoperative use, although there was considerable variation in the choice of opioid and MEQ doses. Consequently, the selection of opioids and dosing strategies for intraoperative prophylactic or postoperative rescue analgesia may vary depending on the individual anaesthesia professional responsible. PACU nurses identified nausea and pain as the two most significant and equally negative factors impacting recovery in PACU.

4.1 Factors influencing opioid administration

We found that anaesthesia personnel predominantly focused on chronic pain, age, preoperative opioid use, body weight and type of surgery to guide perioperative opioid dosing. This is consistent with findings from previous studies.16, 28-31 These studies also suggest that other factors may impact opioid requirements: female sex, psychological distress, anxiety and smoking, although the impact of female sex seems to be controversial.32, 33 While preoperative anxiety or psychological distress were not on the list of factors in our survey, anaesthesia personnel rarely added them under ‘other predictors’.

4.2 Choice of opioids

Danish anaesthesia personnel preferred fentanyl and morphine intraoperatively for postoperative analgesia. For postoperative rescue opioid analgesia, morphine i.v. was preferred for moderate postoperative pain, fentanyl i.v. or morphine i.v. were most preferred for severe pain, and fentanyl i.v. or oxycodone i.v. were preferred for severe pain with ORADEs. In the literature, it is debatable whether fentanyl, oxycodone, and morphine differ in their impact on the risk of ORADEs. However, it has been suggested that oxycodone or fentanyl may reduce ORADE incidences compared with morphine.9, 34 Due to its short-acting pharmacodynamics, fentanyl may require larger MEQ doses to provide adequate analgesia over time.35 Longer treatment with large MEQ doses combined with potential likability from short-acting opioids may increase the risk of addiction and abuse.36-39 Whether this is the case for short-term opioid treatment during the recovery phase is unclear. We observed that only a small number of anaesthesia personnel used methadone as first- or second-line treatment intraoperatively. A recent study suggests that methadone may reduce the need for rescue opioids without increased risk of ORADEs.40

4.3 Opioid dosing variations

In our survey, we found considerable variation in opioid dosing, which has also previously been demonstrated among anaesthesia personnel in the intraoperative phase,41-43 during recovery36 and among surgeons at discharge.44 These findings can partly be explained by limited evidence, random variation, and individual emphasis on various factors.

Current evidence suggests that i.v. MEQ between 3 and 6 mg corresponds to one meaningful ORADE, around 5 mg i.v. MEQ seems reasonable to consider as a clinically relevant difference for postoperative opioid consumption.7, 45 A recent study reported that up to 20% of patients experience moderate to severe pain shortly after PACU arrival.46 There is likely an optimal intraoperative opioid dose for each unique patient in terms of benefits and harm, resulting in the lowest level of pain and ORADEs after anaesthesia.26

Opioid dosing ranges found in this survey come from hypothetical cases but seem to approximate opioid doses that have been reported previously.47 We cannot make statements about how Danish anaesthesia personnel actually dose. However, our survey helps to elucidate patterns in anaesthesiologists, nurse anaesthetists and PACU nurses. Heterogeneity at the clinician level seems to contribute strongly to variation despite high adherence to guidelines. This study does not evaluate the quality or efficacy of guidelines; therefore, we cannot make statements about the most optimal opioid strategies. However, we encourage using multimodal procedure-specific pain management as the current gold standard.48 Given the considerable variations in opioid doses, evidence-based guidelines, pain education, and individualised dosing algorithms could guide clinicians in targeting the optimal doses.

Higher intraoperative MEQ doses for short-acting opioids, such as fentanyl and sufentanil, found in our survey suggest that opioid conversions may not only depend on potency but also on duration of action.49

4.4 Impact of ORADEs

PACU nurses regarded nausea and pain to be equally negative factors impacting recovery in the PACU, which aligns with patient perspectives on nausea.50, 51 Apart from being directly patient-relevant, ORADEs negatively impact health care costs and clinical outcomes,52, 53 and pain management strategies should emphasise reducing ORADEs.

4.5 Strengths and limitations

A strength of the survey is the nationwide coverage and the use of site investigators, which ensured acceptable overall response- and missingness rates compared with other surveys in pain management, where response rates range between 13% and 31%.54-57 Other strengths are that the survey was pilot-tested three times in different regions before distribution, and a protocol was published before the survey launch. Our findings on opioid dosing variation do not surprise us because this phenomenon is well-documented. Nonetheless, this survey makes an earnest and novel attempt to provide, as comprehensively as possible, a multidimensional perspective of the aspects that influence dosing across the perioperative course amongst Danish anaesthesia personnel. It facilitates stronger awareness and discussion about opioid pain management, and it offers the potential for creating more user-friendly guidelines that encompass patient-specific aspects. In addition, it elucidates some aspects of opioid practice that can help inform the design of artificial intelligence-based prediction models of optimal opioid doses for patients.

Our survey has some important limitations. The clinical cases are simplified compared with daily clinical practice, and we refrained from advanced statistical analyses on these because we considered them beyond the scope of this survey. In clinical scenarios, patients received systemic multimodal analgesia but not regional anaesthesia despite its regular use in clinical practice. We excluded regional anaesthesia to avoid response fatigue given the level of detail of such procedures, for example, type of technique, concentration, dose and adjuvants. Likewise, we did not specify intraoperative remifentanil consumption nor make it clear whether local infiltration analgesia was administered in the clinical scenarios—not doing so may have increased the variance of our results. Moreover, anaesthesia personnel who do not provide anaesthesia and analgesia to abdominal and/or orthopaedic surgeons (<30% of respondents) may have chosen doses for clinical cases based on prior experience in these specialities. However, we did not inquire further into how much time had elapsed since respondents potentially held such positions. Only a small number of respondents used combinations of opioids in the postoperative cases. These were omitted from the results section even though anaesthesia personnel likely combine drugs and doses to provide short- and long-term pain relief. Further, we did not include the small number of entries such as ‘preoperative anxiety’ or ‘psychological distress’ under ‘other predictors’ regarding factors influencing opioid administrations. We sought to strike a balance between providing sufficient information and avoiding respondent fatigue, which may have affected and reduced the validity of our results. Potential sources of bias are variations in response- and missingness rates. In terms of generalisability, an overall response rate of 48% does not reflect the entire population of Danish anaesthesia personnel. To the best of our knowledge, other nationwide surveys on opioid practices amongst anaesthesia personnel in other countries do not exist. Therefore, whether our results are comparable in the broader context is uncertain.

5 CONCLUSION

Anaesthesia and PACU personnel in Denmark reported high availability of and adherence to perioperative pain management guidelines. The most important factors used for opioid dose adjustments were in line with findings from the existing literature. Anaesthesia and PACU personnel generally preferred fentanyl and morphine for intra- and postoperative pain management with considerable dosing variations. It remains unknown whether this variation has a clinically relevant impact on the proportion of patients experiencing postoperative pain and ORADEs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

APHK and MW conceptualised the study and drafted the survey content with revisions from OM, AKN, CSM, TI and TXMT. TXMT and MW designed the survey in REDCap. TXMT coordinated the study, and OM and AKN assisted with the recruitment of site-investigators. MHO conducted the statistical analysis. TXMT and APHK drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and take responsibility for the content. The OPI•AID Collaborators (see Acknowledgments section) contributed to the recruitment of study participants and data collection. All authors fulfil the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to heartfully thank site investigators and respondents who contributed their time and effort to ensure the successful completion of this project. CSM has founded a start-up company, WARD24/7 ApS, with the aim of pursuing the regulatory and commercial activities of the WARD project (Wireless Assessment of Respiratory and Circulatory Distress, a project developing a clinical support system for continuous wireless monitoring of vital signs). WARD24/7 ApS has obtained a license agreement for any WARD-project software and patents. One patent has been filed: ‘Wireless Assessment of Respiratory and Circulatory Distress (WARD), EP 21184712.4 and EP 21205557.8’. None of the other authors had any commercial conflict of interest.

Collaborators

The OPI•AID Collaborator Group are listed below in alphabetical order by first name. The collaborators should be defined as seen in the ‘Collaborator Names’-section in Authorship in MEDLINE (nih.gov):

Alexander Rosholm Tørresø (Hospital Sønderjylland, Aabenraa and Sønderborg, Denmark)

Anders Kehlet Nørskov (Copenhagen University Hospital—North Zealand, Hillerød, Denmark)

Anders Peder Højer Karlen (Copenhagen University Hospital—Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Anneline Borchsenius Seegert (Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark)

Ede Orbán (Aalborg University Hospital, Thisted, Denmark)

Elin María Thorsteinsdottir (Viborg Regional Hospital, Viborg, Denmark)

Eske Kvanner Aasvang (Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Fabian Spies (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark)

Hans-Hinrich Wilckens (Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, Næstved, Denmark)

Hayan El-Hallak (Copenhagen University Hospital—Herlev and Gentofte, Gentofte, Denmark)

Jannie Bisgaard (Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark)

Jimmi M. S. Jensen (Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark)

Johan Heiberg (Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Kariatta Esther Værum Novrup (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark)

Karsten Kindberg (Bornholms Hospital, Bornholm, Danmark)

Kim Wildgaard (Copenhagen University Hospital—Herlev and Gentofte, Herlev, Denmark)

Kristine Nielsen Strunge (Gødstrup Regional Hospital, Gødstrup, Denmark)

Laila Mulla Reich (Copenhagen University Hospital—Amager and Hvidovre, Hvidovre, Denmark)

Lene Lehmkuhl (Odense University Hospital—Svendborg Sygehus, Svendborg, Denmark)

Mads Have (Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark)

Marie Louise Lyster (North Denmark Regional Hospital, Frederikshavn and Hjørring, Denmark)

Mark Søgaard Niegsch (Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Mathilde Enevoldsen (Viborg Regional Hospital, Viborg, Denmark)

Mette Lea Mortensen (Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Mikkel Schjødt Heide Jensen (Silkeborg Regional Hospital, Silkeborg, Denmark)

Niels Vendelbo Knudsen (Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Niklas Ingemann Nielsen (Copenhagen University Hospital—Amager and Hvidovre, Hvidovre, Denmark)

Omar Faiz Hashim Al Mohamadamin (Zealand University Hospital, Nykøbing Falster, Denmark)

Pernille Linde Jellestad (Holbæk Hospital, Holbæk, Denmark)

Rajiv Gambhir (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark)

Simon Strøyer (Copenhagen University Hospital—Amager and Hvidovre, Hvidovre, Denmark)

Stefan Anegaard Lausdahl (Lillebælt Hospital, Vejle, Denmark)

Stine Thorhauge Zwisler (Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark)

Thomas Gyldenløve (Horsens Regional Hospital, Horsens, Denmark)

Torsten Wentzer Licht (Friklinikken i Region of Southern Denmark, Grindsted, Denmark)

Tutku Karaca (Randers Regional Hospital, Randers, Denmark)

Wojciech Jan Pietrzyk (Lillebælt Hospital—Kolding Sygehus, Kolding, Denmark)

Yifei Cao (Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, Slagelse, Denmark)

Alexander Rosholm Tørresø, Anders Kehlet Nørskov, Anders Peder Højer Karlen, Anneline Borchsenius Seegert, Ede Orbán, Elin María Thorsteinsdottir, Eske Kvanner Aasvang, Fabian Spies, Hans-Hinrich Wilckens, Hayan El-Hallak, Jannie Bisgaard, Jimmi M. S. Jensen, Johan Heiberg, Kariatta Esther Værum Novrup, Karsten Kindberg, Kim Wildgaard, Kristine Nielsen Strunge, Laila Mulla Reich, Lene Lehmkuhl, Mads Have, Marie Louise Lyster, Mark Søgaard Niegsch, Mathilde Enevoldsen, Mette Lea Mortensen, Mikkel Schjødt Heide Jensen, Niels Vendelbo Knudsen, Niklas Ingemann Nielsen, Omar Faiz Hashim Al Mohamadamin, Pernille Linde Jellestad, Rajiv Gambhir, Simon Strøyer, Stefan Anegaard Lausdahl, Stine Thorhauge Zwisler, Thomas Gyldenløve, Torsten Wentzer Licht, Tutku Karaca, Wojciech Jan Pietrzyk, Yifei Cao

FUNDING INFORMATION

TXMT and APHK received funding from Copenhagen University Hospital—Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The full statistical analysis is available, and the R-scripts can be acquired through contact with the corresponding author.