Conus medullaris termination: Assessing safety of spinal anesthesia in the L2–L3 interspace

Abstract

Background

Classic teaching is that spinal anesthesia is safe at or below the L2–L3 interspace. To evaluate this, we sought to determine the percentage of individuals with a conus medullaris termination (CMT) level at or below the L1–L2 interspace. Further, the relationship of CMT level to age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and spinal pathology was examined, as was the reliability of using Tuffier's line (TL) as an anatomical landmark.

Methods

This retrospective study evaluated magnetic resonance images of 944 adult patients to determine the CMT level. The relationship between age, sex, height, BMI, and spinal pathology and CMT level was explored by logistic regression. The correspondence of the TL line to the L4–L5 interspace and the presence of overlap with the CMT were examined using 720 lumbar x-rays of the same patient cohort.

Results

Of 944 patients (mean age, 57.8 years; 49% male), 18.9% had CMT at or below the L1–L2 interspace, and spinal anesthesia at the L2–L3 interspace was found to carry a 0.7% incidence of neuraxial risk. Only the presence of congenital spinal abnormalities was found to be significantly predictive of having a CMT at or below the L1–L2 interspace. TL was found to correspond to the L4–L5 interspace in 99.8% of patients with lumbar x-rays.

Conclusions

Spinal anesthesia at the L2–L3 interspace, using TL as an anatomical landmark, is safe in >99% of patients. However, caution must be exercised in all patients as demographic variables were found to be limited in predicting a low CMT level.

Editorial Comment

Unlike previous smaller studies, this retrospective study included MRI data from a total of 944 patients. The present study confirms that spinal anesthesia at the L2–L3 interspace or below can be considered safe. The findings indicate that Tuffier's line can be used as a reliable anatomical landmark.

1 INTRODUCTION

An important question for the safety of spinal neuraxial techniques is the true anatomic location of the caudal tapering of the spinal cord, the conus medullaris termination (CMT). The correct appreciation of its position has important consequences, as the placement of a spinal needle above its terminal level can lead to neurological injury. Anatomic CMT positions have been explored in both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cadaveric studies,1 and have been found to be between T12 and L3 and follow a normal distribution with a peak incidence of position at the lower third of the L1 vertebra.2-5 However, anatomic variants due to age,5-7 sex,2-4, 6, 8 height,9 body mass index (BMI), and spinal cord pathology2 may result in the CMT being located at a lower position with consequential increased risk of neurologic injury.8

Of further concern is that anesthesiologists often fail to correctly identify the lumbar interspaces by palpation on clinical examination. Tuffier's line (TL), a horizontal line that intersects both iliac crests, is often used on palpation as an anatomical landmark for the L4–L5 interspace to guide needle insertion. However, surface palpation has been shown to inaccurately identify intervertebral spaces with a margin of error of up to four spaces, and anesthesiologists may underappreciate the level of the CMT over 50% of the time.10 While convenient, the use of TL as a landmark may lead to the selection of an inappropriately high vertebral interspace that may put patients at risk for spinal cord injury or an inappropriately elevated spinal block.

Given the continued reports of spinal cord injury below L2 secondary to spinal anesthesia,11-14 and the higher incidence of these complications in patients with spinal pathology,15, 16 this study aims to evaluate the safety of spinal anesthesia at the L2–L3 interspace and below. Currently available literature reports findings in small and specific populations, such as pediatric patients, parturients, elderly, and obese patients. Our study's objective was to use a larger, more representative sample of adult patients where the results have more generalizability. First, we will investigate the percentage of patients with CMT terminating at or below the level of the L1–L2 interspace. We will then correlate this finding to predictor variables for having a low CMT position (e.g., age, sex, BMI, height, and spinal pathology). This study also evaluates the reliability and clinical safety of TL by investigating whether it accurately corresponds to the L4–L5 interspace on radiography and that it does not overlap with a patient's CMT.

2 METHODS

With approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (13/12/2013, Project number 13-820-C), a retrospective radiographic study was performed on spinal MRIs and lumbar x-rays of 944 adult patients (>18 years; 474 men and 470 women) who presented for imaging for pre-existing spinal pathology at Hamilton Health Sciences between September 2011 and September 2013. Informed consent was waived as this was a chart review. Abnormal MRI scans were included and further categorized according to the presenting abnormality. Exclusion criteria included sacralization or lumbarization (difficulties in accurately determining CMT position); MRI did not include the lumbar region; and lumbar x-rays were only from intraoperative fluoroscopy.

Two independent radiologists determined the position of the CMT and TL on imaging. All MRI scans were taken in the supine position, and the CMT position was visualized on a midline, sagittal sequence using T1- or T2-weighted imaging with a 4 mm slice thickness. TL was determined on lumbar x-ray. Any disagreement in position determination was resolved by discussion between the two radiologists until consensus.

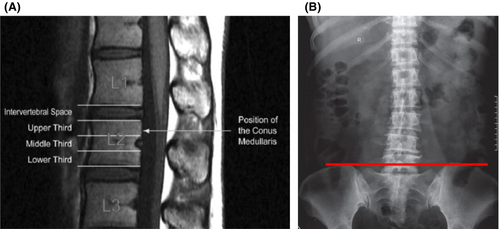

The CMT was defined as the most distal point of the spinal cord visualized on imaging. Its position was determined by dividing the vertebral bodies into upper, middle, and lower thirds, with the intervertebral disc being considered a separate region. The CMT position was assigned by drawing a horizontal line perpendicular to the long axis of the cord (Figure 1A) as per the method of Reimann and Anson.17 To determine the correspondence of TL to the L4–L5 interspace on lumbar x-ray, we considered this space to be inclusive of both the L4 and L5 vertebrae and the interspace between them. These data were collected from the x-rays by drawing a horizontal line across the highest points of the iliac crests (Figure 1B).

Patients' age, sex, ethnicity, weight, height, and BMI were also recorded. Lumbar x-ray reports, if completed within 5 years of the MRI, abdominal x-ray reports, and documentation of spinal pathology were obtained from health records.

2.1 Statistical analysis

Nine hundred thirty-seven people are required to detect a proportion of 2.5% of patients with CMT positioned below L2, with a two-sided 95% confidence interval and a 1% margin of error.6 These computations were derived from the simple asymptotic formula based on the normal approximation to the binomial. The sample size was computed using PASS 2024, version 24.0.2.

CMT position was reported for each vertebral level or interspace as the number (n) and percentage (%) of patients with a given CMT position with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A univariable logistic regression was performed to explore potential risk factors (for CMT termination at or below the L2/3 level) and expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI. The frequency of the vertebral positions corresponding to TL on lumbar x-ray was reported as the number (n) and percentage (%) of patients with a given position with a 95% CI. The analyses were exploratory, and therefore we did not adjust for the level of significance for multiple testing and did not quote p-values. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 16 (College Station, TX, USA).

3 RESULTS

The anatomical position of the CMT was evaluated in 991 patients; 21 patients were excluded due to not meeting the age criteria, four were excluded due to unidentifiable CMT positions, and 22 were excluded due to lumbarization and sacralization. Of the 944 remaining patients (mean age, 57.8 years; 49% male), the CMT position was found to be most frequently (51.1%) at the L1 vertebral level. Of these, 766 patients (81.1%) had a CMT that terminated at the L1–L2 interspace or above, while 178 patients (18.9%) had a CMT that terminated below this level. Three patients (0.3%) were found to have a CMT positioned at the L2–L3 interspace and three patients (0.3%) were found to have a CMT positioned at the L3–L4 interspace or below. Overall, the CMT was found to terminate at or below the L2–L3 interspace in seven patients (0.7%, 95% CI: 0–2.57) (Table 1). Interrater agreement was 99% in CMT determination, which rose to 100% after discussion of the cases where there were differences.

| CMT location | n (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| T11–12 interspace | 2 (0.2) | 0–0.51 |

| T12 | 114 (12.1) | 9.99–14.16 |

| T12 upper vertebra | 11 (1.2) | 0.48–1.85 |

| T12 middle vertebra | 31 (3.3) | 2.14–4.42 |

| T12 lower vertebra | 72 (7.6) | 5.93–9.32 |

| T12–L1 interspace | 168 (17.8) | 15.35–20.24 |

| L1 | 482 (51.1) | 47.86–54.25 |

| L1 upper vertebra | 187 (19.8) | 17.26–22.36 |

| L1 middle vertebra | 160 (17.0) | 14.55–19.35 |

| L1 lower vertebra | 135 (14.3) | 12.06–16.54 |

| L1–2 interspace | 109 (11.6) | 9.5–13.59 |

| L2 | 62 (6.6) | 4.98–8.15 |

| L2 upper vertebra | 40 (4.2) | 2.95–5.52 |

| L2 middle vertebra | 17 (1.8) | 0.95–2.65 |

| L2 lower vertebra | 5 (0.5) | 0.07–0.99 |

| L2–3 interspace | 3 (0.3) | 0–0.68 |

| L3 | 0 | – |

| L3–4 interspace | 1 (0.1) | 0–0.31 |

| L4 | 2 (0.2) | 0–0.51 |

| L4 upper vertebra | 2 (0.2) | 0–0.51 |

| L4 middle vertebra | 0 | – |

| L4 lower vertebra | 0 | – |

| L4–5 interspace | 0 | – |

| L5 | 0 | – |

| L5 upper vertebra | 0 | – |

| L5 middle vertebra | 0 | – |

| L5 lower vertebra | 0 | – |

| S1 | 1 | – |

| S1 upper vertebra | 1 (0.1) | 0–0.31 |

- Note: Data are expressed as the frequency, the % of total patients (N = 944), and the 95% CI.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMT, conus medullaris termination.

Table 2 illustrates the univariable analysis of potential predictive demographic factors in patients who have a CMT positioned above the L1–L2 interspace and those who have a CMT positioned at the L1–L2 interspace or below. Univariable logistic regression for predictor variables demonstrated that increases in age, increases in BMI, increases in height; male sex, or the presence of spinal pathology, other than congenital abnormalities, did not significantly increase a patient's odds of having a CMT that terminates at or below the L1–L2 interspace. The presence of congenital spinal abnormality increased a patient's odds of having a CMT at or below the L1–L2 interspace by 4.42 (95% CI: 1.41–13.87).

| Variable | CMT above L1–L2 interspace (n = 766) | CMT at or below the L1–L2 interspace (n = 178) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years), n; mean (SD) | 766; 56.3 (16.4) | 178; 59.0 (16.3) | 1.10 (1.00–1.22)* |

| BMI (kg/m2), n; mean (SD) | 356; 29.1 (5.8) | 76; 28.4 (5.6) | 0.89 (0.71–1.11)a |

| Height (cm), n; mean (SD) | 357; 169.5 (10.2) | 76; 167.8 (11.2) | 0.85 (0.67–1.08)b |

| Male sex, n (%) | 384 (50.1) | 90 (50.6) | 1.02 (0.74–1.42) |

| Lumbar spine pathology | |||

| Disc bulge/herniation, n (%)c | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 2.16 (0.19–23.93) |

| Spinal canal stenosis, n (%)c | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0) | ** |

| Scoliosis, n (%) | 92 (12.0) | 18 (10) | 0.82 (0.48–1.41) |

| Compression fracture, n (%) | 72 (9.40) | 17 (9.5) | 1.02 (0.58–1.77) |

| Spina bifida, n (%)c | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | ** |

| Osteoarthritis, n (%) | 78 (10.2) | 20 (11.2) | 1.12 (0.66–1.88) |

| Osteopenia/Osteoporosis, n (%)c | 18 (2.4) | 4 (2) | 0.96 (0.32–2.86) |

| Congenital/developmental variant, n (%)d | 6 (0.78) | 6 (3.37) | 4.42 (1.41–13.87) |

| Tethered spinal cord, n (%)d | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | ** |

| Neoplasia, n (%)c | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1) | 4.34 (0.61–31.03) |

| Traumatic lesion, n (%)c | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 4.32 (0.27–69.43) |

| Inflammation, n (%)c | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | ** |

| Infection, n (%)c | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 4.32 (0.27–69.43) |

| Hematoma, n (%)d | 5 (0.6) | 3 (2) | 2.61 (0.62–11.02) |

| Degenerative disc disease, n (%) | 297 (38.8) | 81 (45.51) | 1.32 (0.95–1.83) |

| Spondylolisthesis, n (%) | 116 (15.14) | 29 (16.29) | 1.09 (0.70 to.70) |

| Postoperative changes, n (%) | 155 (20.23) | 30 (16.85) | 0.80 (0.52–1.23) |

| Discitis n (%)d | 7 (0.91) | 4 (2.25) | 2.49 (0.72–8.61) |

| Other, n (%) | 27 (3.52) | 8 (4.49) | 1.33 (0.43–4.13) |

- Note: ORs calculated by univariable logistic regression for predicting a low CMT level. Lumbar pathologies were diagnosed by x-ray (n = 720). Regression performed with change in age by 10 years.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CMT, conus medullaris termination; OR, odds ratio.

- a Regression performed with change in BMI by 5 kg/m2.

- b Regression performed with change in height by 10 cm.

- c Fisher's exact test performed.

- d Diagnosed by MRI studies.

- ** Logistic regression not performed due to insufficient events.

We further sought to quantify the number needed to harm (NNH) if spinal anesthesia were to be performed at a given interspace between T11 and L5. We determined that 18.9% of participants would be at risk of spinal cord injury if spinal anesthesia were to be performed at the L1–L2 interspace whereas only 0.7% of the patient population would be at risk if neuraxial anesthesia were to be performed one interspace lower (Table 3).

| Location of needle insertion (interspace) | Incidence of neuraxial risk, % | Average number of attempts until the first failure,a NNH |

|---|---|---|

| T11–T12 | 100 | 1 |

| T12–L1 | 87.7 | 2 |

| L1–L2 | 18.9 | 6 |

| L2–L3 | 0.7 | 136 |

| L3–L4 | 0.4 | 239 |

| L4–L5 | 0.1 | 910 |

- Abbreviation: NNH, number needed to harm.

- a Calculated as the reciprocal of the incidence (1/%).

A second variable in the conduct of prudent spinal anesthesia technique is the accuracy and safety of the landmark that is used to guide needle insertion. Lumbar x-rays were obtained for 720 patients. TL on x-ray imaging corresponded to the L4–L5 interspace in 99.1% of patients. TL corresponded to a vertebral level above the L4 vertebrae in 0.1% of patients (Table S1). It was further found that a patient's TL overlapped with their CMT in three cases and with the interspace above TL line in four cases (Table S2).

4 DISCUSSION

Spinal anesthesia is a common technique in which needle insertion is usually aimed at the L3–L4 interspace, based on the teaching that neuraxial anesthesia at or below the L2–L3 interspace is safe. However, although rare, these injuries carry significant burden, and continued reports of spinal cord injury have substantiated the need to revisit this paradigm.11-14, 18, 19

In this study, we found that 18.9% of patients had a CMT located at or below the L1–L2 interspace and concordantly, found an incidence of risk of 18.9% if spinal anesthesia were to be performed at that level. The incidence of risk dropped to 0.7% if performed at the L2–L3 level. In performing a logistic regression analysis, we did not find that increases in age, BMI, weight, height, or male sex significantly increased the odds that a patient would have a CMT positioned at or below the L1–L2 interspace. However, patients with congenital spinal abnormalities may be at higher risk for spinal cord injury due to increased odds of having a CMT at or below the L1–L2 interspace (OR: 4.42; 95% CI: 1.41–13.87). Lastly, it was found that TL (determined radiologically in patients standing upright without lumbar flexion) corresponded to a vertebral level above L4 in only 0.1% of patients. However, if spinal anesthesia were to be performed at the interspace level corresponding to TL, the level above or below, the frequency of overlapping with CMT would be 1.1%. This latter finding is significant as this is how most clinicians landmark for their needle insertion, and it is not uncommon to try multiple levels when doing spinal anesthesia.

While it was found that congenital spinal abnormality did increase the chance of having CMT occur lower than the L1–L2 interspace, this was not the case with all of the other spinal pathologies in the study sample: disc herniation, spinal stenosis, scoliosis, compression fracture, spina bifida, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, tethered spinal cord, neoplasm, traumatic lesion, inflammation, infection, hematoma, degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis, postoperative changes, and discitis. This is also reflected in the literature. In a study evaluating the level of CMT in healthy individuals and those with lumbar disc herniation, Kalindemirtas et al. found no statistically significant difference between the two groups.20 Similarly, MRI evaluation of patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) showed no difference in CMT compared with age-matched individuals without AIS.21, 22 Additionally, lumbar spinal stenosis23 and thoracic vertebral compression fracture2 may be factors in the level of CMT. In our study, the most common lumbar spine pathologies (ranked in order of frequency seen) in this study sample were degenerative disc disease, postoperative changes, spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, and osteoarthritis, and these conditions accounted for 90% of the pathology seen. The fact that the presence of lumbar spine pathology, other than congenital abnormality, did not impact the CMT level in this large study sample helps make the findings from this study more generalizable to patients without lumbar spine pathology; of note, spinal anesthesia is routinely used in commonly performed orthopedic, urological, abdominal, and thoracic surgeries,24-26 and our data further underscore the variability of CMT position in a general adult population.

Our results for the CMT levels are consistent with previously published studies that have reported that 8.45% to 26% of patients have a CMT position below the L1–L2 interspace.3, 6, 23, 27 However, we did not replicate previous findings of CMT level discrepancies on the basis of sex, which indicated more caudal CMT levels in females.2, 4, 6, 8 The studies that reported sex differences, with the exception of the work by Lin et al., investigated the CMT position in a healthy adult population. In contrast, our patient population was presenting for imaging for diagnostic purposes, and our results may reflect methodological confounds. Patients of both sexes in our study may have had non-specific vertebral deformities such as loss of bone mass or degenerative disc changes that reduce the height of the vertebral body and decrease the position of the CMT.28, 29 The chance of having at least one vertebral deformity has previously been shown to be 39% in both men and women30 and may explain our study's lack of sex differences. However, these findings are not consistent with previous work that indicates that the effects of spinal pathology on CMT position are more pronounced in females, likely secondary to females having a greater vulnerability to changes in bone mineral density.2

Previously, studies have also reported a lower CMT position with increasing age,5, 7 but this finding was not replicated in our study. The authors of the previous studies hypothesized that age-related deterioration of the spine may explain the lower CMT position.2 It is possible that in our patient cohort, age was not independently predictive of having a low CMT position. Rather, spinal deterioration and decreased spinal length as a result of changes to the intervertebral discs, ligaments, and vertebral bodies may be predictive of a low CMT level. These changes can be a function of aging but also of other spinal pathologies, such as previous back injury.31 Again, it is possible that our study's use of a patient cohort with pre-existing pathology may have confounded the relationship between age and CMT position. Furthermore, the age distribution of our sample, with mean ages of 56 and 59 in both groups, may be such that we did not capture the extremes of ages in which there may be a more pronounced correlation to CMT position.5

While the relationship between sex, age, and the CMT position has been extensively studied in MRI studies, the influence of height and BMI has not. Our study did not find that increases in height or BMI increased the odds of having a CMT position at or below the L1–L2 interspace. Of the spinal pathologies studied, the only variable that was found to be predictive of a low CMT position was congenital spinal abnormalities. Overall, these data imply that anesthesiologists must consider the possibility of a low CMT level in all patients, as demographic variables are largely unreliable in predicting a low CMT level. They should also be particularly vigilant when providing spinal anesthesia to patients with known congenital spinal abnormalities.

Last, our study established the relationship between TL and its radiographic vertebral correlates. Our results suggest that it is an accurate marker of the L4–L5 interspace and can be used safely for landmarking as it overlaps with the CMT in <1% of patients. These results are consistent with previous work that demonstrated that on average, there are two vertebral bodies and two disc spaces separating the CMT and TL.4 While TL was found to indicate the L4–L5 interspace in >99% of patients, this is a radiographic correlation, and does not account for variations in patient position or body habitus that may modify its reliability on palpation, where it has been shown to correspond instead to the L3–L4 interspace.32 Furthermore, TL was evaluated with the patient in the supine position. The vertebral level of TL when patients are in the left lateral decubitus position or when the spine is flexed for needle insertion may be different than when patients are supine.33 This may explain in part the observed differences between the space that is indicated by TL radiologically and that which is felt on palpation. Examining the patient by ultrasound is thought to better identify the appropriate site of lumbar level for spinal anesthesia.34

Our study differed from previously published literature in its large sample size and its broader study of predictor variables that included BMI and height. However, this study has several limitations. The patient population in this study had an indication for spinal imaging due to pre-existing pathology. Consequently, our results may not be generalizable to a younger and healthier adult population. Due to its relationship with age, sex, and BMI, pre-existing pathology in our patients also precludes an independent analysis of the association between these predictor variables and the CMT level. Furthermore, spinal pathology at the thoracic or cervical levels may have a differential effect on the CMT position, and these were not analyzed in our study. Finally, some spinal pathologies such as spina bifida, inflammation and spinal canal stenosis had so few documented events that a logistic regression was unable to be performed with any kind of statistical power (Appendix A). Selecting participants based on the presence of select spinal pathologies and enlarging our study cohort may allow for a better appreciation of the effect of specific spinal pathologies on CMT localization and improve the analysis of our study. Another limitation of our study is that TL was determined radiologically, whereas in clinical practice it is determined by palpation of the iliac crests. Given that body habitus impacts the level of TL when determined by palpation, our findings may have found the level of TL at a level below where it would have been found if it was assessed clinically in our study population. Future studies could address these limitations by determining TL both clinically and radiologically in a prospective manner in a sample of patients who undergo MRI for study purposes as opposed to a clinical complaint.

Ultimately, our study indicates that while it carries a non-zero risk of spinal cord injury, spinal anesthesia at the L2–L3 interspace is reasonably safe. The results further indicate that it is important for anesthesiologists to give consideration to the site of spinal needle placement in all patients as demographic variables, other than the presence of a congenital spinal abnormality, were not found to be predictive of a low CMT level. In addition, anesthesiologists must consider the precision of the technique that is used to landmark. While TL was found in the majority of cases to radiologically correspond to the L4–L5 interspace and to allow for a safe margin with the CMT level, complex patient factors such as body habitus or position may lead to inaccuracies and ultimately compromise the safety of the technique.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

James E. Paul conceived the study, supervised the data extraction, planned the analysis, and contributed to writing the manuscript. Lisa A. Udovic conceived the study, built the data extraction form, and assisted with the data extraction. Kathleen Oman and Leora Bernstein assisted with data extraction and writing the manuscript. Luigi Matteliano and Nina Singh interpreted the MRI scans and lumbar x-rays and contributed to the manuscript. Alexa Caldwell contributed to writing the manuscript. Thuva Vanniyasingam completed the study analysis. Lehana Thabane assisted with the development of the study and supervised the data analysis. All authors contributed extensively to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are most grateful to the staff of the imaging services at Hamilton Health Sciences for the provision of the imaging used in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX A

Frequency of “other” types of lumbar x-ray pathologies.

| “Other” x-ray pathology | Frequency (n) |

|---|---|

| 6 lumbar vertebrae TL at L5–L6 | 1 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 1 |

| Decreased lumbar lordosis | 1 |

| Disc degenerative changes | 1 |

| Grade 1 anterolisthesis of L4 over L5 and bilateral spondylosis | 1 |

| Grade 1–2 anterolisthesis with bilateral spondylosis | 1 |

| L4–5 grade 1 anterolisthesis | 1 |

| L5 compression fracture | 1 |

| Loss vertebral body height | 1 |

| Loss of lumbar lordosis | 1 |

| Lucency of L3 | 1 |

| No anteroposterior view provided | 1 |

| 5 lumbar-type vertebrae with a transitional S1 vertebrae | 1 |

| Lumbarization of S1 | 1 |

| Paget's disease | 1 |

| Retrolisthesis | 1 |

| Sacralization of L5 on the left side, disc space narrowing | 1 |

| Vacuum disc phenomenon | 1 |

| Anterolisthesis | 1 |

| Burst fracture | 1 |

| Dextroscoliosis at L3 | 1 |

| Disc space narrowing | 1 |

| Erosion | 1 |

| Hemivertebrae | 1 |

| Mild degenerative change | 1 |

| Postoperative hardware intact | 1 |

| Posterior fixation of L4/L5 loss of L5/S1 | 1 |

| Reduction in disc height | 1 |

| Sacralization of L5 | 1 |

| Screws and metal rods inserted | 1 |

| Spondylolysis | 3 |

| Wedging | 1 |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.