Job Market Competency Requirements for Accounting Professionals: A Comparative Analysis of Online Job Ads from SMEs and Large Enterprises*

Accepted by Philippe Lassou. The authors thank Philippe Lassou (associate editor) and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

ABSTRACT

enCompared to large enterprises (LEs), small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have unique characteristics that may affect their needs in several areas. Thus, the “one-size-fits-all” approach to meeting the needs of both groups of enterprises would be inappropriate in different circumstances. In this study, we examine the current competency requirements of the Canadian market for professional accounting jobs with the following research question in mind: To what extent do SMEs' requirements for professional accounting positions differ from those of large companies? The study draws on person-environment fit theory and job market signaling theory. It is based on a content analysis of 310 online job postings (of which 111, or 35.8%, are from SMEs) for accounting professionals or for positions requiring strong accounting knowledge. Our results show a complex picture made up of similarities and differences between SMEs and LEs' requirements when recruiting professionals in accounting-related positions. The study points to some paradoxes and contributes to the debate about the evolution of accounting education in relation to specific business needs. In particular, the study suggests that SMEs' competency requirements are not necessarily commensurate with the needs dictated by their specific context. From a practical point of view, the results of the study could be of interest to SME managers and organizations dedicated to SMEs' development; recruitment services; national accounting organizations, such as the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada; and the academic and professional communities involved in the training of professional accountants.

RÉSUMÉ

frExigences du marchÉ de l'emploi en matiÈre de compÉtences pour les professionnels de la comptabilitÉ : analyse comparative des offres d'emploi en ligne des PME et des grandes entreprises

Par rapport aux grandes entreprises, les petites et moyennes entreprises (PME) ont des caractéristiques uniques qui peuvent affecter leurs besoins dans plusieurs domaines. Par conséquent, dans bien de situations, il serait mal avisé de vouloir répondre uniformément aux besoins des deux groupes d'entreprises. Dans cette étude, nous examinons les exigences actuelles du marché canadien en matière de compétences pour les postes de professionnels comptables en gardant à l'esprit la question de recherche suivante : dans quelle mesure les exigences des PME en matière de postes de professionnels comptables diffèrent-elles de celles des grandes entreprises? L'étude s'appuie sur la théorie de l'adéquation personne-environnement et sur la théorie des signaux du marché de l'emploi. Elle repose sur une analyse de contenu de 310 offres d'emploi en ligne (dont 111 – 35.8 % proviennent de PME) pour des professionnels de la comptabilité ou des postes nécessitant de solides connaissances comptables. Nos résultats montrent une image complexe faite de similitudes et de différences entre les exigences des PME et des grandes entreprises lorsqu'elles recrutent des professionnels pour des postes liés à la comptabilité. L'étude met en évidence certains paradoxes et contribue au débat sur l'évolution de l'enseignement de la comptabilité par rapport aux besoins spécifiques des entreprises. En particulier, l'étude suggère que les exigences des PME en matière de compétences ne correspondent pas nécessairement aux besoins dictés par leur contexte spécifique. D'un point de vue pratique, les résultats de l'étude pourraient intéresser les dirigeants de PME et les organisations dédiées au développement des PME, les services de recrutement, les organisations comptables nationales telles que l'Ordre des comptables professionnels agréés du Canada, ainsi que les communautés académiques et professionnelles impliquées dans la formation des comptables professionnels.

1 INTRODUCTION

The environmental context in which enterprises operate evolves, and sometimes the changes involved can be profound. One of the roles of managers is to ensure that their companies keep pace with these changes to survive and remain competitive. To do so, they need to ensure that the skills required of their employees meet the current and future needs of their organizations. Although the changing environment applies to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as to large enterprises (LEs), prior studies tend to demonstrate that both categories of enterprises may differently perceive, be affected by, or adapt themselves to the same changes. In other words, “size matters” in many aspects, due essentially to size-related discrepancies in objectives, resource constraints (Laukkanen et al., 2007), and organizational culture (Gray et al., 2003). In this study, we investigate potential differences between SMEs and LEs with regard to current competency requirements for accounting-related jobs. In accordance with the person-job fit perspective, part of person-environment (P-E) fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018), we assume that SMEs and LEs may seek different competency profiles for their jobs. Understanding these differences and their implications may help different stakeholders avoid the “one-size-fits-all” approach when addressing the competency needs of organizations with regard to professional accounting services. Thus, the guiding research question is as follows: To what extent do SMEs' requirements for professional accounting positions differ from those of large companies? The emphasis on the distinction between SMEs and large companies is a continuation of the “big GAAP/little GAAP debate” (Christie & Brozovsky, 2010; Morris & Campbell, 2006). Indeed, based on discussions of the subject in the scientific literature, the debate seems to have been put on hold with no satisfying conclusion having been reached (Wright et al., 2012). Our results will contribute to this debate by providing the empirical basis for comparisons of the accounting competencies required according to company size. This is also in line with calls to consider the differences between SMEs and large companies in terms of the competency requirements for accounting professionals (Schutte & Lovecchio, 2017; Subačienė et al., 2022). In the same vein, Armitage et al. (2016) have argued that “there is value in research specifically focused on the use of management accounting techniques by SMEs,” particularly “given their distinctiveness relative to large firms” (p. 33).

Although this study builds on previous research, it does address some of the limitations of the latter. Prior research has shown that competencies required of accounting professionals are multifaceted and have been evolving, reflecting the dynamic nature of the economic and technological environment (Kroon et al., 2021; Melnyk et al., 2020). While traditional technical competencies remain crucial, there has been a growing emphasis on interpersonal and digital skills (Dolce et al., 2019; Subačienė et al., 2022; Weli & Marsudi, 2022). Despite this evolution, research continues to point to a persistent gap between the competencies developed through the training offered to accountants and the specific expectations of the labor market (Elbarrad & Belassi, 2023; Gupta & Marshall, 2010; Kroon & Alves, 2023). In particular, it appears that the relative level of importance of competencies does not translate into an equivalent level of proficiency of professional accountants (Budding et al., 2022). The persistence of these gaps shows that research has so far failed to suggest effective ways of bridging them. This failure seems to be the result of at least two research limitations. First, the research often lacks theoretical and empirical rigor or validation (Dyckman & Zeff, 2014; Kroon & Alves, 2023; Weigel & Hiebl, 2023; Wolcott & Sargent, 2021) and fails to provide actionable insights for curriculum development, thereby limiting its practical applicability in addressing the competency gaps in the accounting profession. Lastly, the research often fails to account for the diverse perspectives of various stakeholders, including employers, professional organizations, and the accountants themselves, leading to a fragmented understanding of competency requirements (Elbarrad & Belassi, 2023; Parvaiz et al., 2017). Considering the limitations of previous research, the present study is built on solid theoretical foundations and adopts a rigorous empirical approach. In addition, it considers different perspectives, notably by comparing employers' needs with the academic training sanctioned by the professional order of accountants.

Based on job market signaling theory (Spence, 1973) and following prior research (Dunbar et al., 2016; Gardiner et al., 2018), we assume that whenever enterprises' managers announce their job openings, they are giving relatively clear signals about their current and future needs. In accordance with this assumption, we collected and analyzed data from 310 online job advertisements (job ads) for accounting professional positions or for jobs requiring strong accounting content knowledge (such as CFO or controller). In the data collection process, we targeted job ads originating in Canada, whether published in English, French, or both languages. Through a content analysis of job ads, we highlight prominent accounting-related competencies that Canadian SMEs and LEs currently require from their prospective employees. We also highlight competencies that, although listed by Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada), are absent or almost absent from the market requirements. After the content analysis, we proceed with a cluster analysis that allows us to uncover patterns in organizations' competency requirements.

The results show a complex picture of similarities and differences between SMEs and LEs' requirements when recruiting professionals in accounting-related positions. They highlight some paradoxes that should draw the attention of different stakeholders. For instance, when compared to LEs, SMEs recruit accounting professionals for higher-level positions, without requiring more work experience or a professional accreditation, requirements that would normally be justified by the responsibilities at that level. That level would also justify more requirements of enabling competencies by SMEs, but the results show no significant differences between SMEs and LEs in this regard. Overall, it seems that the requirements of SMEs do not necessarily reflect their specific needs. In addition, highlighting the competencies more or less required by LEs and SMEs provides a contribution to the debate on the practical choices regarding the relevance and the modalities of training on these competencies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 deals with the theoretical foundations of the study—in particular, the formulation of the research hypotheses. Section 3 deals with the methodological aspects, detailing the data collection and coding processes as well as the data analysis. We devote Sections 4 and 5, respectively, to the presentation and discussion of the results. In particular, we discuss the theoretical and practical contributions of the study in Section 5. Finally, we devote Section 6 to the concluding remarks.

2 THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

We begin by discussing the concepts of competency and competence before elaborating on the competency-based training approaches in the accounting profession. Then, we discuss to what extent SMEs present specific accounting competency requirements. After that, we present the theoretical perspectives adopted in this study before formulating the research hypotheses.

Competency or Competence?

As illustrated by prior studies over at least the last three decades (Delamare Le Deist & Winterton, 2005; Eraut, 1998; Norris, 1991; Teodorescu, 2006), the complexity of the concept of “competency” has contributed to confusion in its use in the context of education and training in different professions. In particular, the use of the concept in its two variations (competency and competence) has been inconsistent (Delamare Le Deist & Winterton, 2005). In spite of the confusion and the inconsistency that shroud these concepts, we can infer from their discussions in the above-mentioned studies that competency refers to a set of generic or general characteristics, behaviors, attributes, or skills that are the hallmarks of successful individuals in different situations and for a reasonably long period of time, while competence is more context-specific and task-oriented. More specifically, competence refers to the “ability to perform the tasks and roles required to the expected standard” (Eraut, 1998, p. 129). Teodorescu (2006) argues that the focus of competence models is “the definition of measurable, specific, and objective milestones describing what people have to accomplish to consistently achieve or exceed the goals for their role, team, division, and whole organization” (p. 28).

It also appears that competencies are necessary inputs for competence. Indeed, certain knowledge, behavior, and attributes prepare one to successfully accomplish the required tasks. Thus, competency-based training focuses “on the definition and achievement of ‘competencies’ which, when aggregated, [are] assumed to constitute competence in one particular kind of job” (Eraut, 1998, p. 131). However, one can analyze the relation in both directions, meaning that through the repeated accomplishment of a given task (competence), people end up developing or improving specific knowledge, behavior, and attributes (competency). This close link adds to the confusion one finds in the literature and practice related to competency-based training in many fields.

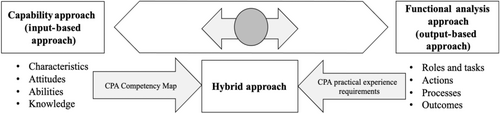

Competency-Based Training Approaches in Accounting

One may establish a parallel between competency/competence conceptions on the one hand and two main competency-based training approaches on the other. These approaches are the functional analysis approach (also called output-based approach) and the capability approach (also known as the input-based approach) (Uwizeyemungu et al., 2020). The output-based approach, which relies on the expected performance outcomes of job tasks based on the definition of requirements of such tasks, is more aligned with the concept of competence. As for the concept of competency, it is more aligned with the input-based approach, which relies on characteristics, attitudes, skills, or knowledge possessed by individuals that will have to perform a task or a set of tasks pertaining to a job role.

Conceptually speaking, these approaches, each in their pure form, reflect two opposite positions that we can place on the extreme ends of a continuum, as illustrated in Figure 1: at the first end, a pure input-based approach would be theoretical, emphasizing the acquisition of cognitive processes for a given task; on the other end, a pure output-based approach would be practical, emphasizing well-described, observable actions, and measurable outcomes of the task. However, the pure forms of both approaches are rather rhetoric, considering that, in reality, theory informs practice, and vice versa, in the sense that practice or experience may help to refine theory. It is undoubtedly with this in mind that Bassellier et al. (2003), studying the information technology (IT) competencies required of non-IT professionals, defined a competence as a duality of knowledge and experience. Thus, the paradigm shift advocated for in business education for the adoption of a competence-based approach (Bratianu et al., 2020) is more about moving the needle toward the functional analysis (output-based) approach rather than scratching altogether the capability (input-based) approach. The question that remains, however, is to determine to what extent the needle (illustrated by the circle in Figure 1) should be moved.

The accounting profession in North America initiated the move toward a competency-based approach in 1989, in reaction to a report by the Big 8 CPA firms in the United States (Palmer et al., 2004). Nowadays, it appears that the CPA certification body has adopted a hybrid approach (see Figure 1), thus acknowledging the dual nature of the accounting profession that requires accounting professionals demonstrate a mix of knowledge and practical experience. The CPA Competency Map (CPA Canada, 2020) details specific competencies CPA candidates must develop “during the CPA certification program, including both the professional education program component and the practical experience component” (p. 2). CPA Canada (2021) complemented the Competency Map with an ad hoc document, CPA Practical Experience Requirements, focusing on the practical experience requirements. In line with these documents, new versions have been proposed (CPA Canada, 2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b), including Competency Map 2.0 (CPA Canada, 2022c).

CPA Canada's competency frameworks do not specifically elaborate on potential differences between SMEs and LEs. But, as explained in the introduction, there are reasons to think that the specificities of SMEs may affect their accounting competency needs to some extent.

Accounting Competency Requirements for SMEs

For a long time, management science literature has denounced the practice of not differentiating between different sizes of organizations and of considering by default an SME as no more than a reduced form of a large company (Hadjimanolis, 2000; Torrès & Julien, 2005). Torrès and Julien (2005) emphasize the specific nature of SMEs, which, according to the literature, is based on at least six characteristics. First, SMEs generally operate with fewer resources. Second, their strategies and processes are often more intuitive and less formalized. Third, they are characterized by the centralization of management around the owner-manager. A fourth characteristic is the low level of specialization and functional differentiation in terms of management, employees, and equipment. A fifth characteristic concerns the generally informal and poorly organized information system of SMEs. Finally, SMEs are generally characterized by a greater proximity at different levels, allowing direct contact between hierarchical levels and more informal, friendly working relationships.

In this study, we simply define SMEs as firms with fewer than 250 full-time employees, which is the threshold proposed by the OECD (2005), of which Canada is a member. We have adopted this threshold rather than the one of 500 full-time employees sometimes used in Canada (Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada, 2019), based on the observation that, as they grow, companies tend to adopt “denaturing” practices that distance them from the specificities of small businesses and make them more like large corporations (Torrès & Julien, 2005).

SMEs are an important component of the economic fabric of countries throughout the world. In Canada, for instance, firms with fewer than 100 employees make up 97.9% of all enterprises and account for 69.8% of the private workforce (Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada, 2019). Consequently, no professional body whose members are called upon to serve businesses can ignore SMEs. This is particularly true for the accounting profession as a significant amount of accounting professional activities is directed toward SMEs. Banham and He's (2014) study suggests that SMEs generate “about 71% of the total business in public practicing accounting firms” (p. 211). It is thus surprising to notice that little is actually known about accounting at the SME level (Armitage et al., 2016; Pan & Lee, 2020; Tudor & Muţiu, 2008). However, it is generally assumed that SMEs, due to their specificities when compared to LEs, may have different requirements with regard to accounting services. This acknowledgment has led to calls for the adaptation of GAAP to the reality of SMEs. The debate around this matter, called the “big GAAP/little GAAP debate,” has been going on for many years (Burton & Hillison, 1979; Lippitt & Oliver, 1983; Morris & Campbell, 2006) and seems to have reached a crisis point, prompting some to wonder if it will ever end (Wright et al., 2012). In July 2009, following and in the midst of this debate, the IASB issued the IFRS for Small and Medium-Sized Entities (IFRS for SMEs; IFRS, 2009). In spite of its title, which suggests that the standard's applicability is limited to SMEs, its definition indicates that the IFRS for SMEs applies to all nonpublicly accountable entities, regardless of their size (Warren et al., 2020). Warren et al. (2020) suggest that the “perversity” of the title and the “contradictions” between the title and the scope of the standard were “the outcome of a complex political process of negotiation and compromise” (p. 125). In June 2013, acknowledging this confusion, the IASB issued a guide to help micro-sized entities apply the IFRS for SMEs (IFRS, 2013). However, all these developments did not put an end to the debate on the relevance of the “little GAAP.” We are still far from reaching unanimity on this matter, and despite the remarkable promotional efforts of various institutions, many professional accountants still have doubts about the merits of the IFRS for SMEs (Ghio & Verona, 2018). There is at least one case reported in which the proposal to enforce the standard was deemed controversial, which led the standard setter to step back and work on addressing the “anomalies” in the standard (Arafat et al., 2020).

The application of the IFRS for SMEs to all nonpublicly accountable entities, regardless of their size, makes it comparable to the Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE), released in Canada in 2009 (Durocher & Fortin, 2014). In both cases, even if company size is not the primary criterion for the application of these standards, we have to recognize that SMEs are predominantly private companies and as such will be the main users of these standards.

Despite the lack of unanimity and the controversies raised here and there, the IFRS for SMEs has progressed. The count from IFRS (2023) shows that as of July 2024, out of 168 jurisdictions listed, the standard was required or permitted by 86 jurisdictions (51.19%) and under consideration in 12 (7.14%), for a total of 98 (58.33%).

Theoretical Perspectives

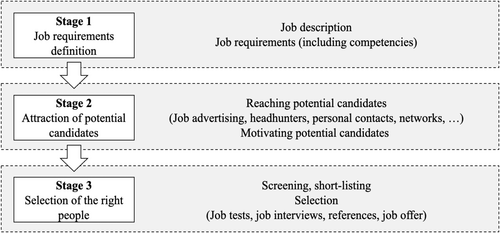

The present study relies on job ads to identify the job market requirements, particularly in terms of competencies. However, job advertisement is only a portion of the hiring process. This process is one of the activities that has a significant impact on a company's success. Effective recruitment involves finding and hiring the best candidates to achieve the organization's strategic objectives (John, 2019). As summarized in Figure 2, the hiring process can be broken down into three broad stages: the job requirements definition stage, the attraction stage, and the selection stage (Ganesan et al., 2018; Hamilton & Davison, 2018; Hippolyte & Haruna, 2017; Stoilkovska et al., 2015). Within the second stage, one of the most common recruiting strategies used to attract the right candidates is job advertisement. To reach and attract potential candidates, job advertisement may use different channels, such as newspapers, Internet, formal or informal networks, television, and radio. Generally, when combining multiple channels, a job ad designer will try to use the same information, no matter the ad vehicle, to ensure consistency and equal employment opportunities (Stoilkovska et al., 2015). In this study, we have chosen online job ads as they are the recruiters' favorite tool and the most common approach used to reach job seekers (Ganesan et al., 2018).

As shown by a study by Mahjoub and Kruyen (2021), most ad-related studies are atheoretical. Only a few of them (11.5%) have explicitly applied one or more theoretical perspectives. In the few studies that applied theories, Mahjoub and Kruyen (2021) identified eight theories, among which the most used were P-E fit theory (36%), signaling theory (21%), and congruity theory (14%), for a total of 71% of the studies. We based the rationale of this study on the premises of both P-E fit theory and signaling theory, and we did not consider congruity theory, whose focus is on-the-job ads reception, and would thus require inputs from job seekers.

P-E fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018) explains the attraction of a job seeker toward a particular organization by the level of compatibility between that individual and the work environment offered by the organization. Studies that use P-E fit theory as their theoretical perspective intend “to explain why some applicants or employees feel more inclined to pursue a job with a certain employer, intend to quit the organization, or are more committed” (Verwaeren et al., 2017, p. 2814). In a broader perspective, the P-E fit covers several subareas, such as person-organization fit, person-job fit, person-vocation fit, person-group fit, person-supervisor fit, and person-reward fit (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Verwaeren et al., 2017). The match between people's knowledge, skills, and abilities, on the one hand, and the requirements of the job, on the other hand, pertains to the person-job fit subarea, and it would be the most aligned with the present study.

Signaling theory explains, in particular, the behavior of two parties in communication while being in a situation of information asymmetry. In the absence of direct and complete information, each party tries to read between the lines to find cues (signals) that would allow them to complement the information it already has on the other party. Knowing this, any party may intentionally spread some cues to convey the desired message. The domain of the labor market is well suited to signaling theory and has provided the context of the initial development of that theory (Spence, 1973). There are previous studies that have used signaling theory to analyze job ads (Ganesan et al., 2018; Moore & Khan, 2020).

In accordance with P-E fit theory, we assume that companies recruiting accounting professionals express their requirements for candidates in terms of expected experience and competencies by taking into account their organizational context as well as the characteristics of the open job in that context. Also, based on signaling theory, we assume that job ads for accounting professionals contain plain or decipherable signals conveyed by the job market toward prospective employees in accounting positions, and we assume that those signals may be meaningful for accounting bodies and accounting educators. The focus is as much on single competencies signaled in job ads as competency sets that would result in accounting job profiles.

Research Hypotheses

Prior studies suggest that due to the scarcity of studies that have specifically focused on accounting in SMEs, little is known about the evolution of SMEs' accounting function (Pan & Lee, 2020; Tudor & Muţiu, 2008). However, based on a combination of (1) the results of the few existing studies, (2) the known specificities of SMEs, and (3) the accounting profession characteristics, we formulate hypotheses with regard to what one may expect from SMEs' versus LEs' accounting job requirements. We begin with hypothesizing about the job position characteristics before elaborating on the nature of required competencies.

2.1 Job Position Characteristics

Generally, a simpler organizational structure is an important characteristic that distinguishes SMEs from LEs (Lavia López & Hiebl, 2015). An organizational structure is “a set of positions and parts of organizations that develop systematic and relatively long-lasting relationships”; it has been “understood more specifically in terms of the division and coordination of the job” (Marín-Idárraga & Hurtado González, 2021, p. 910).

Because of the simplicity of their organizational structure, SMEs are more likely to offer newly recruited professionals positions high up in the organizational hierarchy, involving them in decision-making, with a broader range of responsibilities (Moy & Lee, 2002). In their systematic review of research dealing with accountants in SMEs, Weigel and Hiebl (2023) conclude that accountants in SMEs often need to fulfill multiple roles, including providing reporting services, acting as advisors, and serving as intermediaries between capital providers and the business, which necessitates a broad skill set encompassing financial reporting, advisory capabilities, and strong interpersonal skills. They also highlight the fact that, compared with large firms, accountants in SMEs are very important human resources whose individual impact is more significant. We thus surmise that, in accordance with P-E fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018), SMEs recruiting accounting professionals will be looking to fulfill higher-level positions. In accordance with signaling theory, SMEs will have to find ways to signal this job level (and the responsibilities that come with it) through their job ads. Such signals are usually reflected in the job titles offered as well as in the position of the immediate supervisor (Poba-Nzaou et al., 2020; Uwizeyemungu et al., 2020). In view of the above developments, we can expect the titles indicated in open positions for professional accountants, as well as the titles of immediate supervisors, to signal a higher level in the organizational hierarchy in SMEs than they would in LEs. Hence, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).Job announcements for positions open for accounting professionals are more likely to signal a hierarchically higher level in SMEs than in large firms.

When recruiting, it is common for organizations to require a certain level of experience that would help the newly recruited employees to be effective immediately or at least in the very short term. This is particularly true for employers recruiting accounting professionals, who, in addition to expecting basic accounting and strong analytical skills from their prospective employees, require business awareness or “real-life” experience (Kavanagh & Drennan, 2008). This last study showed that skills related to business awareness/real-life experience were highly valued by employers, especially since they are quite rare among candidates. Firms also value prior work experience as it helps candidates develop generic skills such as interpersonal capabilities, communication, and leadership (Courtis & Zaid, 2002; Jackling & De Lange, 2009). Thus, one could argue that work experience in general, and especially when it is specific to an accounting context, is a major factor for accounting graduates' employability (Low et al., 2016).

Organizations will likely require more experience for senior positions than for junior ones. We assume that SMEs will need their newly recruited accounting professionals to have accumulated some work experience given that, as already mentioned, they will likely end up in decision-making positions and will have to take on a wide range of responsibilities (Moy & Lee, 2002; Weigel & Hiebl, 2023). As for LEs, the need for experience from their newly recruited employees is less acute or urgent: usually, unlike SMEs, large companies have well-established finance and accounting departments (Schutte, 2013; Schutte & Lovechio, 2014); it is thus more likely that LEs will already have at their disposal a large pool of experienced employees in their accounting departments and can, therefore, afford to hire junior employees whose lack of, or limited, experience would be compensated for by that of existing employees. Moreover, it is more likely that the newly recruited candidate in an LE will have to assume a narrowly defined activity requiring specific technical expertise (Hayes et al., 2018) and less work experience. In addition, it has been shown that the larger an accounting firm is, the more it has proactive learning mechanisms and financial means to update its employees' competencies (Hayes et al., 2018; Malo et al., 2024). The point here is that, to a greater extent than SMEs, large companies can afford to hire the least experienced employees. In other words, and with reference to P-E fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018), the environment of large companies makes it easier for them to integrate less experienced people into their accounting departments.

Regarding the requirements of an accounting professional accreditation or any other professional accreditation, we can apply the same reasoning we applied to the work experience. In an earlier phase of this study (Uwizeyemungu et al., 2020), we noted that organizations expecting a wide range of competencies from their candidates were more likely to require an accounting professional accreditation. We concluded that an accounting professional accreditation somehow serves as a signal of the extent of competencies a candidate has developed. Therefore, as SMEs need accounting professionals with more versatile competencies (Hayes et al., 2018; Weigel & Hiebl, 2023), they would be more inclined to rely on an accreditation as a signal of that versatility. For LEs, we can expect that they will already have a large pool of employees in place in their generally well-established and well-staffed financial departments (Schutte & Lovechio, 2014), some of whom have an accounting accreditation. The considerations above allow the formulation of the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).Compared to jobs for accounting professionals open in LEs, job openings in SMEs are more likely to require more work experience and an accounting professional accreditation from prospective candidates.

2.2 Job Competency Requirements

Prior studies have underlined the link between firm size and the degree of job specialization (Oesterreich & Teuteberg, 2019): the larger the firm, the greater the degree of job specialization. Thus, an important characteristic that will likely be common in most SMEs is the low level of specialization in their jobs, which means that in many positions, there will be more generalists performing a variety of tasks (Yew Wong & Aspinwall, 2004). This means that newly recruited accountants in SMEs will have to assume a broader range of responsibilities, requiring a certain level of versatility in competencies for one recruit (Hayes et al., 2018; Weigel & Hiebl, 2023). By comparison, LEs will likely have well-defined positions with limited sets of competency requirements. Following the logic of P-E fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018), the internal environment of SMEs would force them to look for candidates with broad competencies; otherwise, these candidates would find it difficult to meet the versatile needs of SMEs. With reference to signaling theory, the number and diversity of competencies required in a job announcement can be seen as signals of the scope of responsibilities associated with the open position. The developments above allow us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).Compared to LEs, SMEs are more likely to require more competencies for one accounting job announced.

3 (H3) refers to competencies in general, regardless of their type, and can be refined as the needs of SMEs and LEs with regard to the type of competencies required from their newly recruited accounting professionals, which may also vary. The CPA Canada competency framework (CPA Canada, 2020, 2022a) distinguishes two types of competencies: enabling competencies and technical competencies. The framework breaks down enabling competencies into seven areas and technical competencies into six areas (Table 1).

| Enabling competencies | Technical competencies |

|---|---|

| 1. Acting ethically and demonstrating professional values | 1. Financial reporting |

| 2. Leading | 2. Strategy and governance |

| 3. Collaborating | 3. Management accounting |

| 4. Managing self | 4. Audit and assurance |

| 5. Adding value | 5. Finance |

| 6. Solving problems and making decisions | 6. Taxation |

| 7. Communicating |

Enabling competencies, also referred to as pervasive, soft, behavioral, generic, or transversal skills (Barišić et al., 2021), are a set of overarching skills or meta-competencies which individuals require when utilizing other competencies (Morpurgo & Azevedo, 2021). These other competencies are technical competencies, which are task-specific, nonpersonal skills, referred to as hard skills. They are specific to an area of professional expertise or qualification.

The CPA framework acknowledges the importance of IT competencies but does not dedicate a separate category to them, considering that they are spread across the other six categories of technical competencies (CPA Canada, 2020, p. 137). While the rationale behind this decision is understandable, it results in IT competencies being overshadowed by the other technical competencies they are supposed to enable. Given their pervasive nature and their growing importance in professional jobs, and particularly the growing demand for accounting professionals to develop advanced IT competencies (Pan & Seow, 2016), we decided to treat them separately as a third type of competencies alongside the enabling and technical competencies.

Considering that, on the one hand, that accounting professionals recruited in SMEs will have to take on higher responsibilities upon their first day on the job, and on the other hand, that the importance of enabling competencies increases as one moves from lower to higher levels of job positions (Margheim et al., 2010; Uwizeyemungu et al., 2020), we can assume that SMEs will be prone to expect their candidates to possess a good number of enabling skills.

The picture with technical competencies seems less clear. On the one hand, as the importance of technical skills decreases as one moves toward higher-level jobs, one can assume that SMEs whose newly recruited professionals will likely end up in top jobs (Moy & Lee, 2002) might be less inclined to require technical competencies. Moreover, given the more general nature of their jobs, SMEs will be less likely to seek out highly specialized accounting technical competencies. On the other hand, an accounting professional in an SME will be responsible for most of the accounting operations, a role that requires extensive technical skills. In an LE, a professional entering the workforce in an accounting position will likely be responsible for a narrowly defined area instead of the whole process and will simply need a set of limited (or specialized) technical competencies. The need to require both technical and enabling competencies from candidates has been empirically established for small to medium-sized accounting firms (Hayes et al., 2018). We thus assume that, in accordance with P-E fit theory (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006; van Vianen, 2018), SMEs will value both technical and enabling competencies more than LEs. Hence, we formulate the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).Job offers from SMEs will have more requirements for enabling competencies than those from LEs.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).Job offers from SMEs will have more requirements for technical competencies than those from LEs.

As for IT competencies, the need for such competencies can be assumed to be commensurate with the extent of IT use in enterprises. Prior studies on IT adoption have consistently shown that adoption rates are higher in LEs than in SMEs, a phenomenon known as the digital divide between SMEs and LEs (Arendt, 2008; Bach et al., 2013). We thus propose that LEs will, more than SMEs, tend to require IT competencies from their candidates. Hence, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3c (H3c).Job offers from LEs will have more requirements for IT competencies than those from SMEs.

3 METHOD

Data Source

For this study, we rely on secondary data in the form of online job ads posted on various job websites. As previously demonstrated and in line with job market signaling theory, online job ads constitute a reliable source of data in different research areas (Almgerbi et al., 2022; Kennan et al., 2006; Mahjoub & Kruyen, 2021; Poba-Nzaou et al., 2020). We rely solely on online job ads, which in the current digital age dominate the job market. Emerging around 1992, online job ads quickly spread across the World Wide Web, due notably to their numerous advantages when compared to offline job ads (Romanko & O'Mahony, 2022). They are more customizable and therefore more relevant, as they ensure a wider coverage while being more cost-efficient. Estimates are that online postings represent 60%–70% of all vacant positions, and 80%–90% for positions in which at least a bachelor's degree is a requirement (Carnevale et al., 2014), as is the case for professional accountants in Canada.

We collected job ads for accounting professionals in Canada over the period 2016–2020. After the removal of duplicates, we found a total of 310 job ads that met all the inclusion criteria. The first inclusion criterion was that the open position had to be either an accounting position or a position specifically requiring accounting skills. The second inclusion criterion was that the prospective employer had to be a Canadian organization. These criteria allow for the comparison of organizations that are under the same legal system and that refer to the same competency framework for the accounting profession. As a third inclusion criterion, the clear identification of the recruiting organization in the job ad allowed for the collection of data on prospective employers (size and sector of activity).

Job ads collected came from general job websites, as follows: Indeed (152 ads, 49.0%); Workopolis (73, 23.6%); Jobillico (40, 12.9%); Jobboom (30, 9.7%); Neuvoo (13, 4.2%); and other sources (2, 0.6%). One may combine Indeed and Workopolis statistics given that the first acquired the second in 2018 (Cheesman, 2018). This raises the representation of Indeed to 225 ads (72.6%). These statistics reflect the predominance of Indeed in the market of online job search engines in Canada (Dilmaghani, 2019). We completed the data gathered from job websites by consulting the official websites of recruiting organizations. This was necessary whenever the details provided in the ads were insufficient to portray the prospective recruiter, notably in terms of size (number of employees) and sector of activity.

Data Collection

We asked two research assistants to browse online job sites looking for job ads that met the inclusion criteria. The research assistants first identified the sites where online job ads were posted in Canada and then searched for ads using the following keywords: accountant/accounting, finance/financial, audit/auditor, control/controller, tax/taxation. The first research assistant covered the period 2016–2017, and the second covered 2018–2020. Each research assistant collected the data in two phases. The first phase corresponded to the general data collection from online job sites and, whenever necessary, from recruiting organizations' websites. The second phase consisted of extracting competency requirements from each job ad and classifying them into different competency categories according to the coding scheme (presented in the next section). Whenever the research assistants identified a job ad that met all the criteria, they recorded it entirely in a PDF file and gave it an identification number. They then gathered relevant information from each job ad and entered it in a prepared Excel spreadsheet. The spreadsheet was prepared so that it could be used to collect relevant information for the two phases of data collection. This information includes general data on the job ad (website, date published, expected start date for the job, language); information on the recruiting organization (name, location of headquarters, size [number of employees], main activity sector, type of clientele); information about the advertised position (title, direct supervisor); and information about general requirements (qualification [training, experience, knowledge of the sector], professional accreditation); and competency requirements. The file thus formed assembled the raw data for the subsequent steps of data coding and analysis.

Coding Process

For general information regarding the job ad, the recruiting organization, and general requirements, we relied on an inductive coding process. This means that for each type of information, we elaborated a series of codes following a scoping review of the content of data collected. For the most part, this information was factual (e.g., number of employees, job websites), and the coding was meant to facilitate statistical analyses. For example, codes 1, 2, 3, and 4 represented, respectively, organizations with fewer than 100 employees; with 100 or more employees but fewer than 250; with 250 or more but fewer than 500; and organizations with 500 or more employees.

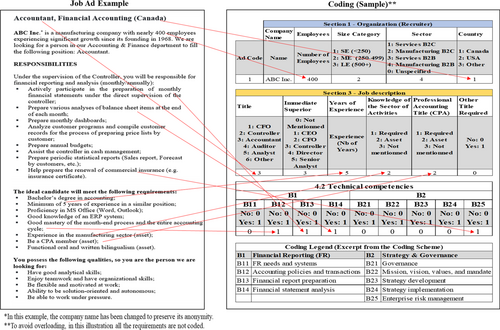

For the competency requirements, we mixed deductive and inductive approaches of coding. For the deductive approach, we elaborated a competency framework based mostly on CPA Canada's competency framework, using the 2020 version (CPA Canada, 2020),1 the most recent available during the study.

To elaborate the initial coding scheme, we made a number of practical decisions. The first decision was to consider a third type of competencies, namely the IT competencies. We have already explained the rationale behind this decision. For this added type of competencies, we elaborated a coding scheme based on Bassellier et al.'s (2003) IT competency for business managers. We adapted the framework to take into account two main factors. First, considering the IT developments since the publication of the framework, we slightly adapted it to include competencies that arose along with enterprise-integrated software packages, Internet-based systems and cybersecurity concerns, data analytics, and knowledge-based systems. Second, as this study targets specifically accounting professionals, competencies related to functional software particularly applied in finance/accounting were included in the framework. We ended up with a well-developed coding scheme for IT competencies that can be found in a previous study (Uwizeyemungu et al., 2020). However, in this study, we have adopted a condensed version of this coding scheme, using the six broad categories of IT competencies of the scheme.

The second practical decision was with regard to the depth of our coding scheme. As the CPA framework progressively subdivides competencies into sub-competencies that are themselves subdivided into more detailed competencies, for the sake of parsimony we decided to limit ourselves to the second level of subdivision in each category of competencies. We present in Appendix 1 the competency coding scheme with which we started the coding process. In total, the coding scheme comprises 66 competencies distributed as follows: 27 enabling competencies (grouped into 7 subcategories), 33 technical competencies (grouped into 6 subcategories), and 6 subcategories of IT competencies.

We prepared an Excel spreadsheet detailing competencies as found in the coding scheme, and we reserved additional columns for potential competencies not already listed. With this last precaution, we wanted to make sure to account for any new competency required by prospective employers but not already listed in the CPA framework. This is in accordance with an inductive coding approach.

For the coding, we asked one of the two research assistants to code all the data based on the coding scheme. More precisely, for competency requirements, the research assistant read every competency requirement listed in a job ad and compared it to the list of competencies in the coding scheme. The assistant used a binary coding system: code one for each matched competency in the scheme, and zero otherwise. If the assistant did not find a required competency in the initial coding scheme, the instruction was to add it to the scheme. In Appendix 2, we provide an example of a typical job ad and show how it has been coded.

To improve and verify the reliability of the coding process, we took the following precautions. First, before the coding process per se, we randomly selected 10 cases from the data, and the research assistant, along with the two authors, coded them separately. We then met to discuss the results of our coding in order to develop a common interpretation of the coding scheme. Second, during the coding process by the research assistant, the two authors were available to discuss any doubts that arose during the process. The main coder (research assistant) had instructions to note any case that seemed unclear for discussion with the whole research team. Third, when the coding process was over, in order to assess to what extent the process was reliable, the two coauthors independently coded 80 randomly selected excerpts of required competencies from the raw data, and we cross-compared the results of the three coders (research assistant plus the two co-authors) for the same segments. These cross-comparisons produced the following Cohen's kappa inter-coder reliability coefficients: 0.77 between coders 1 and 2; 0.79 between coders 1 and 3; and 0.73 between coders 2 and 3. From these coefficients, we can conclude that there is substantial inter-coder agreement (Stemler, 2004).

Clustering Analysis

We used the results of the content analysis to perform a clustering analysis. With this analysis, the intention was to uncover potential patterns of competencies required by prospective employers. The cluster analysis would then allow us to find n groups (clusters) of job ads, constituted such that each group contains ads that are similar to each other (in terms of required competencies) while being substantially different from ads in other groups. For this end, we used numbers of required competencies in different competency subcategories as the clustering variables. For each subcategory of competencies, we counted the number of competencies each organization in the sample required in its job announcement, and we used this value as an indication of the importance of that subcategory for the recruiting employer.

Taking into account that the maximum number of competencies varies from one competency subcategory to another, we first had to standardize the data to avoid giving more weight to subcategories with a high number of competencies (Balijepally et al., 2011; Brusco et al., 2017). We also made sure that multicollinearity among the clustering variables was not an issue: the correlation matrix in Appendix 3 shows negligible correlations varying from a minimum of −0.22 to a maximum of 0.31.

One of the major difficulties in a clustering analysis consists of determining the optimal number of clusters (Mur et al., 2016; Sinaga & Yang, 2020), a decision that weighs heavily on the quality of clustering results. The literature regarding the issue abounds, and there are a multitude of indices proposed to help decide (Charrad et al., 2014). The problem, however, is that different indices sometimes suggest divergent solutions, which raises the question of which indices one should pick. Charrad et al. (2014) proposed considering multiple indices and to take as optimal the number of clusters on which the majority of the indices converge (majority rule). For this purpose, they developed an R package (NbClust) allowing consideration of up to 30 indices simultaneously and different options for the number of clusters, in a single function call.

In this study, we relied on the R package NbClust to determine the number of clusters based on the majority rule. We then combined two types of clustering algorithms. We applied the agglomerative hierarchical clustering algorithm with Ward's minimum variance and squared Euclidian distances as grouping criteria. This allowed the determination of the clusters' centroids. Next, we used the determined optimal number of clusters and the centroids produced by the hierarchical clustering algorithm as initial seeds for a nonhierarchical clustering algorithm (k-means algorithm).

We then proceeded with a discriminant function analysis to validate the cluster analysis results (Hair et al., 2010). Overall, the results of the discriminant function analysis show that 94.0% of LEs and 97.3% of SMEs were correctly classified in their respective clusters. We finally performed a Tamhane's T2 (post hoc) test to ascertain pair-wise differences between clusters' means.

Data Sample

Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the sample. The table combines characteristics of recruiting organizations as well as characteristics of the announced job positions. SMEs, namely those under 250 employees according to the OECD's definition, represent 35.8% of the sample, and LEs (at least 250 employees) represent 64.2%.

| Recruiting organization's characteristics | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Size (number of employees) | < 250 | 35.8 |

| 250–499 | 11.3 | |

| > 499 | 52.9 | |

| Sector | Services | 59.0 |

| Manufacturing | 41.0 | |

| Job position characteristics | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Job title | CFO | 1.6 |

| Controller | 28.7 | |

| Accountant | 5.5 | |

| Analyst | 64.2 | |

| Reporting level | CEO | 6.5 |

| CFO | 31.0 | |

| Controller | 14.5 | |

| Senior analyst/director | 9.7 | |

| Not mentioned | 38.4 | |

| Minimum experience required | 2 years or less | 15.2 |

| 3–4 years | 39.4 | |

| 5 years or more | 45.5 | |

| Sector experience | Required | 24.8 |

| Asset | 18.1 | |

| Not required | 57.1 | |

| Accounting professional accreditation | Required | 48.1 |

| Asset | 22.6 | |

| Not required | 29.4 | |

| Other professional accreditation required | No | 94.8 |

| Yes | 5.2 | |

For the industrial sector, we considered the manufacturing/service distinction since manufacturing firms may have different predispositions and motivations than service firms with respect to adopting contemporary accounting innovations (Preda & Watts, 2004) and would thus need different sets of accounting competencies. In the sample, service firms represent 59.0% against 41.0% for manufacturing firms.

The advertised jobs in the sample are mainly about recruiting a financial analyst (64.2%), and to some extent, they are about filling the controller position (28.7%). The two positions alone account for 92.9% of the jobs advertised for accounting professionals. Only 61.6% of job ads in the sample explicitly mention the reporting level (supervisor) of the prospective employee. The majority of job announcements identify as direct supervisor the CFO (31.0% of all ads, and half [50.2%] of ads that provide the information) and the controller (14.5% of all ads, and 23.5% of ads that provide the information).

In terms of required experience from the candidates, an overwhelming majority of organizations (84.9%) in the sample require a minimum work experience of at least 3 years. Organizations that require a minimum work experience of at least 5 years represent 45.5% of the sample. As for the specific experience related to the activity sector of the recruiting organization, 42.9% of employers deem it either as a required condition (24.8%) or a valuable asset (22.6%). Seven out of 10 employers (70.7%) seeking to recruit an accounting professional consider an accounting professional accreditation as a required condition (48.1%) or an asset (22.6%). A tiny proportion of employers (5.2%) requires any other type of professional accreditation. Examples of required certifications other than CPA include Project Management and Assessment Certification, Project Management Professional, or Chartered Financial Analyst.

4 PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

Job Position Characteristics

In a preliminary analysis of the data, we begin by assessing whether SMEs and LEs in the sample differ significantly with regard to the characteristics of job positions they announce and with regard to the general requirements they expect from candidates in accounting-related jobs. Table 3 presents the results of this comparison.

| SMEs N = 111 | LEs N = 199 | Total N = 310 | Chi-square | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | O | E | R | O | E | R | ||

| Job title | CFO | 1 | 1.8 | −0.8 | 4 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 5 | 47.089*** |

| Controller | 58 | 31.9 | 26.1 | 31 | 57.1 | −26.1 | 89 | ||

| Accountant | 5 | 6.1 | −1.1 | 12 | 10.9 | 1.1 | 17 | ||

| Analyst | 47 | 71.3 | −24.3 | 152 | 127.7 | 24.3 | 199 | ||

| Reporting level | CEO | 17 | 7.2 | 9.8 | 3 | 12.8 | −9.8 | 20 | 29.611*** |

| CFO | 34 | 34.4 | −0.4 | 62 | 61.6 | 0.4 | 96 | ||

| Controller | 19 | 16.1 | 2.9 | 26 | 28.9 | −2.9 | 45 | ||

| Senior analyst/director | 4 | 10.7 | −6.7 | 26 | 19.3 | 6.7 | 30 | ||

| Not mentioned | 37 | 42.6 | −5.6 | 82 | 76.4 | 5.6 | 119 | ||

| Minimum experience required | 2 years or less | 14 | 16.8 | −2.8 | 33 | 30.2 | 2.8 | 47 | 1.935 |

| 3–4 years | 41 | 43.7 | −2.7 | 81 | 78.3 | 2.5 | 122 | ||

| 5 years or more | 56 | 50.5 | 5.5 | 85 | 90.5 | −5.5 | 141 | ||

| Sector experience | Required | 28 | 27.6 | 0.4 | 49 | 49.4 | −0.4 | 77 | 0.444 |

| Asset | 22 | 20.1 | 1.9 | 34 | 35.9 | −1.9 | 56 | ||

| Not required | 61 | 63.4 | −2.4 | 116 | 113.6 | 2.4 | 177 | ||

| Accounting professional accreditation | Required | 51 | 53.4 | −2.4 | 98 | 95.6 | 2.4 | 149 | 4.166 |

| Asset | 32 | 25.1 | 6.9 | 38 | 44.9 | −6.9 | 70 | ||

| Not required | 28 | 32.6 | −4.6 | 63 | 58.4 | 4.6 | 91 | ||

| Other professional accreditation required | No | 107 | 105.3 | 1.7 | 187 | 188.7 | −1.7 | 294 | 0.433 |

| Yes | 4 | 5.7 | −1.7 | 12 | 10.3 | 1.7 | 16 | ||

- Notes: O, observed frequency; E, expected frequency; R, residual (O − E).

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Among the data set of 310 job ads collected, a large portion (199; 64.2%) came from LEs. The overrepresentation of LEs in the sample is even more noticeable if one considers that LEs make up a tiny portion of Canadian enterprises (Tam et al., 2022). The same statistics show that small enterprises employ a significant portion (68.3%) of the total Canadian labor force. However, one may argue that statistics from the sample might be biased due to possible differences between SMEs and LEs with regard to the use of online-based recruitment. Indeed, the study by Campos et al. (2018) suggests that Internet recruitment is more likely in large firms. In this regard, the results of a study by Parry and Tyson (2008) are more nuanced. These authors found that while larger organizations are more likely to use and be successful in using their corporate website for online recruitment, it is the medium-sized organizations that are more likely to choose commercial online job sites (which constitute the source of the data). Therefore, in conclusion for this point, we would argue that the overrepresentation of accounting-related jobs coming from LEs in the sample does not stem from a sampling bias in favor of LEs.

We hypothesized that the hierarchical level of announced positions would be relatively higher in SMEs than in LEs (1 (H1)). We can verify this hypothesis by analyzing statistics related to job titles and reporting levels in Table 3. For both variables, differences between SMEs and LEs are statistically significant. For job titles, it appears that notable differences come from two job titles—namely, controllers and analysts. When compared to LEs, SMEs seem to disproportionately seek to recruit more controllers. The opposite happens when we consider the recruitment of analysts: LEs are more likely to recruit analysts. With regard to reporting levels, the picture is less clear, maybe because more than 38% (119 out of 310) of the job ads do not provide this information. In this regard, LEs represent more than their fair share among firms that do not mention the reporting level. Nevertheless, it appears from the available information that the newly recruited accountants are more likely to report to a CEO when they are recruited by SMEs. Overall, the results from the data confirm 1 (H1).

From the results in Table 3, we cannot confirm 2 (H2). The results show that, whether for the minimum number of years of experience required or for the requirement of experience in the sector of activity, the differences between SMEs and LEs are not statistically significant. The results also suggest that the size of firms has no bearing on whether a professional accreditation (accounting accreditation or other) would be required or considered an asset.

Competency Requirements by Firm Size

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics showing the extent to which different competencies are, on average, prevalent in the requirements of the organizations in the sample. These statistics are broken down into two parts to assess whether there are significant differences in the competencies required by SMEs as compared to large companies.

| All firms | SMEs (≤ 249) | LEs (≥ 250) | t-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 310 | n = 111 | n = 199 | ||||

| Mean | SD | VIFa | Mean | Mean | ||

| A: Enabling competencies | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.78 | 0.81 | −0.89 | |

| A1—Acting ethically and demonstrating professional values | 0.56 | 0.75 | 1.17 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.37 |

| A2—Leading | 0.49 | 0.71 | 1.17 | 0.40 | 0.55 | −1.80 |

| A3—Collaborating | 1.02 | 0.76 | 1.16 | 0.97 | 1.05 | −0.80 |

| A4—Managing self | 1.55 | 0.97 | 1.20 | 1.56 | 1.55 | 0.09 |

| A5—Adding value | 0.49 | 0.66 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.89 |

| A6—Solving problems and making decisions | 0.73 | 0.75 | 1.21 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.33 |

| A7—Communicating | 0.78 | 0.81 | 1.22 | 0.64 | 0.85 | −2.25* |

| B: Technical competencies | 1.17 | 0.43 | 1.30 | 1.10 | 4.12*** | |

| B1—Financial reporting | 2.04 | 1.14 | 1.16 | 2.26 | 1.92 | 2.56* |

| B2—Strategy and governance | 0.78 | 0.91 | 1.28 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 1.13 |

| B3—Management accounting | 2.12 | 1.49 | 1.11 | 2.12 | 2.12 | 0.01 |

| B4—Audit and assurance | 0.42 | 0.56 | 1.16 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 1.67 |

| B5—Finance | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.47 | 1.18 | 2.45* |

| B6—Taxation | 0.38 | 0.81 | 1.22 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 3.83*** |

| C: Information technology competencies | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.30 | −0.14 | |

| C1—Generic knowledge | 0.09 | 0.31 | 1.15 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.15 |

| C2—Knowledge of office productivity software | 0.80 | 0.40 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| C3—Data, database, and analytics | 0.11 | 0.34 | 1.18 | 0.04 | 0.15 | −2.76** |

| C4—Enterprise integrated systems | 0.43 | 0.50 | 1.19 | 0.40 | 0.45 | −0.85 |

| C5—Functional software applied in finance/accounting | 0.25 | 0.47 | 1.17 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 2.77** |

| C6—IT governance and management | 0.06 | 0.28 | 1.19 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −1.20 |

| Total | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 1.82 | |

- Notes: Boldface indicates aggregate values for each of the main competency categories (A, B, and C) and for the entire competency set (Total).

- a Variance inflation factor (VIF) = 1/(1 − Ri2) (where Ri2 is the unadjusted R2 obtained when variable i is regressed against all other variables forming a construct).

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed t-test).

Table 4 reflects statistics based on index scores in each of the 19 subcategories of competencies. An index score corresponds to the sum number of individual competencies a firm requires in each subcategory. For example, in the subcategory of financial reporting, which contains four items (competencies) according to the coding grid (Appendix 1), a firm may get an index score from 0 to 4 depending on the number of items its job ad displays in that subcategory. As suggested, whenever one uses index measures based on multiple items, it is necessary to ensure that multicollinearity among items is not an issue (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001). This was done through the verification of the variance inflation factor (VIF) for the 19 subcategories. These values (Table 4) vary from a minimum of 1.08 to a maximum of 1.28, values far below the cutoff threshold of 3.3 (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006), meaning that there is no multicollinearity in the index scores.

We have formulated a number of research hypotheses on differences between SMEs and LEs with regard to competencies required. First, we expected that SMEs would generally require a higher number of competencies than LEs, all competency categories combined (3 (H3)). The overall mean across all subcategories of competencies (Total raw) shows that there are no significant differences between SMEs and LEs. Therefore, we cannot confirm 3 (H3).

In the broad category of enabling competencies, overall, our results show no significant differences between SMEs and LEs, thus invalidating 3a (H3a). In the broad category of technical competencies, we can confirm 3b (H3b) as it appears that overall, the number of technical competencies required is significantly higher in SMEs than in LEs. As for the broad category of IT competencies, we found no overall significant differences between the two groups of firms, which leads us to invalidate 3c (H3c).

Table 4 also allows us to open up the broad competency categories and to scrutinize potential differences between SMEs and LEs at the level of the 19 competency subcategories. We found significant differences in only 6 out of 19 subcategories of competencies: 1 subcategory out of 7 from enabling competencies (communicating); 3 subcategories out of 6 from technical competencies (financial reporting, finance, and taxation); and 2 subcategories out of 6 from IT competencies (data, databases, and analytics; functional software applied in finance/accounting).

Configurations of Signaled Competencies

When stating their competency requirements in job ads, firms enumerate a number of competencies. One can assume that for similar jobs, companies will require more or less identical or comparable competencies. One would then expect to find competencies in job ads that are generally and frequently required together in such a way that they form bundles of coherent competencies. This allows the analysis of required competencies with a configurational approach. This approach “views organizational phenomena as clusters of interconnected elements that need to be simultaneously apprehended” (Liu et al., 2022, p. 1281). Consequently, we expected to uncover some competency patterns or competency configurations offering, to some extent, a more holistic and integrated image of the job market competency needs in the accounting field—hence, the clustering analysis.

The main objective that was pursued with the clustering analysis in this study was to check whether one can uncover different configurations in competencies signaled by SMEs and those signaled by LEs. We split the data set into two subsamples, one of SMEs (n = 111) and the other of LEs (n = 199). We ran the R package NbClust (Charrad et al., 2014) on both subsamples. For the SMEs subsample, 9 indices from the 23 indices applicable on the data set proposed two as the optimal number of clusters. In second position was a solution with four clusters suggested by 5 indices. For the LEs subsample, 13 indices recommended as optimal a three-cluster solution, followed by a two-cluster solution proposed by 4 indices. Applying the majority rule, we considered, for further analysis, a two-cluster solution for SMEs, and a three-cluster solution for LEs. These results show that the SMEs group generates fewer competency configurations than the group of LEs. Although this difference may not seem particularly significant at first glance, it is worth noting, and it can be explained. As already pointed out, to meet their general needs, SMEs will tend to require a broad spectrum of competencies from their candidates, while large companies will tend to require specific competencies within the competency spectrum. As a result, there will be a greater possibility of variability in competency configurations among LEs than among SMEs.

Table 5 presents the results of a two-cluster solution for SMEs. There are two clusters of equivalent size, with few significant differences. Only 4 groups of competencies out of 19 distinguish the two clusters: 1 group of enabling competencies (communicating), 2 groups of technical competencies (management accounting and taxation), and 1 group of IT competencies (knowledge of office productivity software). As the differences between the two clusters are not sufficiently clear-cut, it is difficult to qualify them. However, based on the few demarcation points that emerge, we can say that the first cluster is made up of SMEs requiring more management accounting competency from their accounting professional, and the second cluster by SMEs requiring more tax competency.

| Cluster 1 n = 55; 49.5% | Cluster 2 n = 56; 50.5% | t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: Enabling competencies | |||

| A1—Acting ethically and demonstrating professional values | 0.58 | 0.59 | −0.049 |

| A2—Leading | 0.35 | 0.45 | −0.898 |

| A3—Collaborating | 0.84 | 1.11 | −1.878 |

| A4—Managing self | 1.4 | 1.71 | −1.723 |

| A5—Adding value | 0.44 | 0.63 | −1.430 |

| A6—Solving problems and making decisions | 0.73 | 0.77 | −0.313 |

| A7—Communicating | 0.47 | 0.80 | −2.378* |

| B: Technical competencies | |||

| B1—Financial reporting | 2.22 | 2.3 | −0.423 |

| B2—Strategy and governance | 0.78 | 0.93 | −0.836 |

| B3—Management accounting | 3.29 | 0.96 | 14.556*** |

| B4—Audit and assurance | 0.44 | 0.54 | −0.974 |

| B5—Finance | 1.55 | 1.39 | 0.910 |

| B6—Taxation | 0.38 | 0.84 | −2.485** |

| C: Information technology competencies | |||

| C1—Generic knowledge | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.688 |

| C2—Knowledge of office productivity software | 0.91 | 0.73 | 2.470** |

| C3—Data, database, and analytics | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.807 |

| C4—Enterprise integrated systems | 0.45 | 0.34 | 1.194 |

| C5—Functional software applied in finance/accounting | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.061 |

| C6—IT governance and management | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.018 |

- Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 6 presents the results of a three-cluster solution for the subsample of LEs. It is worth noting that IT competencies do not play any role in differentiating the three clusters. The smallest cluster (Cluster 3, 18.6%) comprises firms that most value enabling competencies. They also value technical competencies, particularly strategy and governance, management accounting (at the same level as Cluster 1), and finance (at the same level as Cluster 2). Clusters 1 and 2 are comparable in size, but different in terms of competency requirements. While firms in Cluster 1 require at least three types of technical competencies at a higher level (financial reporting, management accounting, and taxation), the only technical competency required at a high level by firms in Cluster 2 is finance competency. The nature of the dominant competencies in each cluster of LEs leads us to suggest that companies in Cluster 2 are essentially looking to fill the lower-level positions of accounting professionals (financial analysts); companies in Cluster 3 are mainly looking to fill the highest-level positions (senior or managerial positions); and companies in Cluster 2 are looking to fill the middle-level positions (top technical professionals).

| Cluster 1 n = 80; 40.2% | Cluster 2 n = 82; 41.2% | Cluster 3 n = 37; 18.6% | N = 199 100% | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Enabling competencies | |||||

| A1—Acting ethically and demonstrating professional values | 0.600a | 0.329b | 0.946a | 0.553 | 10.288*** |

| A2—Leading | 0.275c | 0.488b | 1.270a | 0.548 | 27.307*** |

| A3—Collaborating | 0.838b | 1.024b | 1.541a | 1.045 | 12.310*** |

| A4—Managing self | 1.563 | 1.500 | 1.622 | 1.548 | 0.213 |

| A5—Adding value | 0.313b | 0.500a,b | 0.703a | 0.462 | 5.263** |

| A6—Solving problems and making decisions | 0.525b | 0.695b | 1.189a | 0.719 | 9.921*** |

| A7—Communicating | 0.700b | 0.829b | 1.243a | 0.854 | 5.641** |

| B: Technical competencies | |||||

| B1—Financial reporting | 2.725a | 1.646b | 0.784c | 1.920 | 64.384*** |

| B2—Strategy and governance | 0.450b | 0.659b | 1.514a | 0.734 | 21.586*** |

| B3—Management accounting | 0.438a | 0.268b | 0.486a | 2.116 | 151.192*** |

| B4—Audit and assurance | 0.438 | 0.268 | 0.486 | 0.377 | 2.738 |

| B5—Finance | 0.863b | 1.354a | 1.459a | 1.176 | 6.164** |

| B6—Taxation | 0.475a | 0.073b | 0.162b | 0.251 | 8.395*** |

| C: Information technology competencies | |||||

| C1—Generic knowledge | 0.063 | 0.098 | 0.162 | 0.096 | 1.179 |

| C2—Knowledge of office productivity software | 0.813 | 0.829 | 0.622 | 0.784 | 3.644 |

| C3—Data, database, and analytics | 0.075 | 0.159 | 0.270 | 0.146 | 3.483 |

| C4—Enterprise integrated systems | 0.425 | 0.488 | 0.405 | 0.447 | 0.479 |

| C5—Functional software applied in finance/accounting | 0.200 | 0.159 | 0.243 | 0.191 | 0.55 |

| C6—IT governance and management | 0.025 | 0.061 | 0.216 | 0.075 | 4.942 |

- Notes: Different subscript letters (a, b, c) within rows indicate significant (p < 0.05) pair-wise differences between means on Tamhane's T2 (post hoc) test.

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Most and Least Required Competencies

A close look at the statistics in Table 4 gives a glimpse of which types of competencies firms require most or least frequently. After checking overall mean values in Table 4, we can conclude that employers tend to mostly require technical competencies before enabling competencies, with IT competencies being the least required. The top 5 out of the 19 subcategories of competencies are management accounting (in the first place; mean equals 2.12), financial reporting (2; 2.04), managing self (3; 1.55), finance (4; 1.28), and collaborating (5; 1.02). We also note that the 5 least popular subcategories are IT governance and management (1; 0.06); IT generic knowledge (2; 0.09); data, database, and analytics (3; 0.11); functional software applied in finance/accounting (4; 0.25); and audit and assurance (5; 0.42). One cannot fail to note that 4 of the 5 subcategories of competencies least in demand by the market pertain to the broad category of IT competencies.

The results in Table 7 allow us to further portray the most required individual competencies. The table presents the 20 most required competencies overall and compares their rankings within our subsamples of SMEs and LEs. From a purely arithmetic point of view, we can note that 12 of the competencies ranked in the top 20 are technical competencies, as compared to 6 enabling competencies and 2 IT competencies. However, the most required individual competency is an IT-related competency, C20 (knowledge of office productivity software), present in 79.7% of job ads. Following, in second position, is an enabling competency, A41 (adaptability, resilience and agility; 75.2%), and in third position, a technical competency, B12 (accounting policies and transactions; 68.4%).

| Competency code | Global ranking (n = 310) | Ranking in SMEs (n = 111) | Ranking in LEs (n = 199) | Difference (SMEs − LEs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | Diff. rank | Diff. % | |

| C20 | 79.7 | 1 | 82.0 | 1 | 78.4 | 1 | 0 | 3.6 |

| A41 | 75.2 | 2 | 76.6 | 2 | 74.4 | 2 | 0 | 2.2 |

| B12 | 68.4 | 3 | 76.6 | 3 | 63.8 | 3 | 0 | 12.8 |

| B32 | 62.3 | 4 | 63.1 | 6 | 61.8 | 4 | 2 | 1.3 |

| B13 | 57.4 | 5 | 66.7 | 5 | 52.3 | 6 | −1 | 14.4 |

| A32 | 57.1 | 6 | 57.7 | 7 | 56.8 | 5 | 2 | 0.9 |

| A62 | 52.3 | 7 | 54.1 | 8 | 51.3 | 7 | 1 | 2.8 |

| A71 | 46.8 | 8 | 39.6 | 13 | 50.8 | 8 | 5 | −11.2 |

| A43 | 44.8 | 9 | 48.6 | 9 | 42.7 | 10 | −1 | 5.9 |

| B52 | 43.5 | 10 | 67.6 | 4 | 30.2 | 19 | −15 | 37.4 |

| B11 | 43.2 | 11 | 45.9 | 10 | 41.7 | 11 | −1 | 4.2 |

| C40 | 42.6 | 12 | 38.7 | 16 | 44.7 | 9 | 7 | −6 |

| B33 | 38.7 | 13 | 43.2 | 11 | 36.2 | 15 | −4 | 7 |

| B51 | 38.1 | 14 | 38.7 | 14 | 37.7 | 13 | 1 | 1 |

| B36 | 37.4 | 15 | 38.7 | 15 | 36.7 | 14 | 1 | 2 |

| B31 | 36.1 | 16 | 30.6 | 19 | 39.2 | 12 | 7 | −8.6 |

| B14 | 35.2 | 17 | 36.9 | 17 | 34.2 | 16 | 1 | 2.7 |

| B24 | 32.6 | 18 | 35.1 | 18 | 31.2 | 17 | 1 | 3.9 |

| B42 | 31.6 | 19 | 42.3 | 12 | 25.6 | 21 | −9 | 16.7 |

| A42 | 29.0 | 20 | 25.2 | 21 | 31.2 | 17 | 4 | −6 |

- Notes: The letter in the competency code indicates the broad category of competencies: A, enabling competencies; B, technical competencies; C, IT competencies.

It is worth noting that the top 3 individual competencies are similarly ranked in the two subsamples of SMEs and LEs. The most significant discrepancies in competency ranking between SMEs and LEs among the top 20 are for the following competencies: treasury management (B52), ranked 4th in SMEs and 19th in LEs; internal and external audit requirements (B42), ranked 12th and 21st, respectively, in SMEs and LEs; and enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems (C40), ranked 16th in SMEs and 9th in LEs.

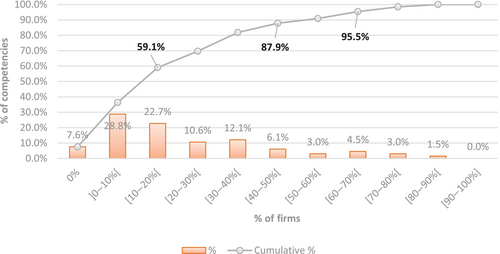

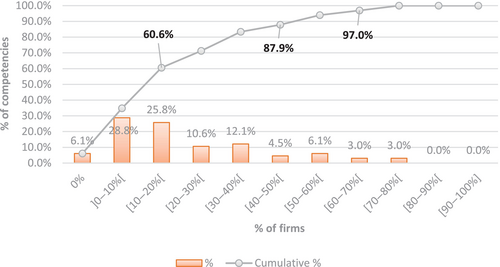

We can also note that there are competencies that, although they are for all practical purposes at the same rank in the SMEs and LEs subsamples, are present in substantially different proportions in the two groups. This is the case for competency B12 (accounting policies and transactions), which ranks third in both groups but is reported in 76.6% of SMEs and only 63.8% in LEs. This is also the case for competency B13 (financial report preparation), ranked 5th and 6th, respectively, in SMEs and LEs, but signaled in 66.7% of SMEs and 52.3% of LEs.