The Sociology of Exclusion: A Knowledge Synthesis of Imperialism, Colonialism, and Postcolonialism in Accounting Research*

Accepted by Merridee Bujaki. I am grateful for the feedback provided by the associate editor, Merridee Bujaki, and other anonymous referees during the review process. Ms. Bujaki's formative approach to the review of this article was a critical factor in its development. I also acknowledge the financial support I received from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Race and Gender Initiative, Canada.

ABSTRACT

enThe ways in which accountancy (accounting, accountability, and accountants) has been a device of imperialism, colonialism, and postcolonialism, and therefore has had deleterious effects on Indigenous peoples in former colonies and continues to negatively impact immigrants in postcolonial OECD countries, is under-researched. This structured literature review synthesizes studies in the accounting literature that have investigated imperialism, colonialism, and postcolonialism and identifies opportunities for future research. This study is part of a broader research project that reviewed 161 articles on accounting and discrimination. This article, based on 65 of the articles reviewed for the broader project, discusses existing knowledge on imperialism, colonialism, and postcolonialism. The author finds that the exclusion of Indigenous peoples in colonial times is shaped by perpetual oppressive relations. In the postcolonial United States and Old Commonwealth countries (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), these power relations are sustained by professions through the continuing exclusion of racialized people and immigrants, many from previous colonies. This study proposes future research directions to advance the decolonization of accounting research by foregrounding alternative perspectives of Indigeneity—such as Black Indigeneity—and enabling accounting scholars to confront the various subthemes of imperialism and postcolonialism in accounting, including Western accounting and accountability, professionalization, emancipatory accounting, and Indigenous knowledge and accounts.

RÉSUMÉ

frSociologie de l'exclusion : synthèse des connaissances sur l'impérialisme, le colonialisme et le postcolonialisme dans la recherche comptable

La recherche est lacunaire concernant les façons dont le domaine comptable (comptabilité, reddition de comptes et profession comptable) a été un instrument de l'impérialisme, du colonialisme et du postcolonialisme et, par conséquent, a entraîné des effets néfastes pour les Autochtones dans les anciennes colonies et continue d'avoir des répercussions négatives pour les immigrants dans les pays postcoloniaux de l'OCDE. Cette analyse documentaire structurée offre une synthèse des études qui, dans la littérature comptable, se sont penchées sur l'impérialisme, le colonialisme et le postcolonialisme, en plus de cerner des possibilités de recherche pour l'avenir. Notre étude fait partie d'un projet de recherche plus vaste dans le cadre duquel 161 articles sur la comptabilité et la discrimination ont été examinés. Le présent article, qui s'appuie sur 65 des articles passés en revue dans le cadre de ce plus vaste projet, aborde les connaissances actuelles sur l'impérialisme, le colonialisme et le postcolonialisme. Nous établissons que l'exclusion des personnes autochtones à l'époque coloniale est induite par des relations d'oppression perpétuelle. Aux États-Unis de l'époque postcoloniale et dans les vieux pays du Commonwealth (Canada, Australie et Nouvelle-Zélande), ces relations de pouvoir sont maintenues par diverses professions au moyen de l'exclusion continue des personnes racisées et immigrantes, dont un grand nombre issues d'anciennes colonies. Cette étude propose des pistes de recherche future visant à faire progresser la décolonisation de la recherche comptable en mettant en lumière des perspectives différentes concernant l'autochtonité — comme l'autochtonité noire — et en donnant aux spécialistes de la comptabilité l'occasion d'aborder divers sous-thèmes associés à l'impérialisme et au postcolonialisme dans le domaine comptable, y compris la comptabilité et la reddition de comptes en Occident, la professionalisation, la comptabilité émancipatoire ainsi que le savoir et les récits autochtones.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most OECD countries have become increasingly multicultural because of modern immigration. In Canada, for example, the 2021 Census identified 8,361,505 people (Statistics Canada, n.d.-a), or 23%, as (first-generation) immigrants and 2,204,485 people, or 6.1%, as Indigenous (Statistics Canada, n.d.-b).1 In reality, the other 70.9% of Canadians are also immigrants—descendants of second, third, or earlier generations who came to the country during colonial and postcolonial times (Statistics Canada, 2022). Migration is (and has always been) primarily informed by human economic needs. Of the immigrant population in Canada, 5,689,715 are economic migrants or are sponsored by their families, and 1,039,725 are refugees who immigrated in search of personal security (Statistics Canada, n.d.-a). Multiculturalism is thus the consequence of human mobility, and one of the consequences of multiculturalism is racism.

Although immigration has a long history as a social phenomenon, it has increased significantly with European imperialism and colonialism, both “forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically” (Kohn & Reddy, 2023, p. 1). Following Said (1993), Power and Brennan (2021) define imperialism as “the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory” and colonialism, “which is almost always a consequence of imperialism, as the implanting of settlements on distant territory” (p. 950). In this study, the term colonies refers to territories controlled by a large population of settled European immigrants from an imperialist empire (e.g., British settlement in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand and Portuguese settlement in Brazil). The establishment of colonies is a consequence of imperialism, but not all imperialism resulted in the establishment of colonies. Furthermore, while imperialism may not have always involved mass European migration to the dominions (e.g., European imperialism in Southeast Asia—see Wickramasinghe, 2015, for the Sri Lankan context—or European imperialism in Africa—see Sian, 2006, 2007, 2011, for studies in the Kenyan context and Ezzamel, 2005, for studies in the Egyptian context), it often involved voluntary migration from Europe and involuntary migration—that is, slavery—from Africa. As Buhr (2011) and Bujaki et al. (2023) note, postcolonialism follows colonialism.2

In Canada, immigration has continually increased since the first major wave of European immigrants arrived in the late 1880s, with exponential increases occurring since the early 1900s (Statistics Canada, 2016), except when legislation was used to curtail immigration by non-Europeans and other people deemed undesirable. Early Canadian immigration exclusion acts, for example, initially prevented criminals from immigration; at various times, legislation limited immigration by Jewish people (Centre for Holocaust Education and Scholarship, 2017), South Asians (Chinese Immigration Act, 1885), Black people (Order-in-Council PC 1911-1324, 1911), and people with disabilities (Boychuk, n.d.; Immigration Act, 1906), effectively criminalizing race and disability.

OECD countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand (the Old Commonwealth),3 and the United States have a shared history as British colonies. Moreover, these lands belonged to Indigenous peoples before they were dispossessed by colonialism. The colonial conquest was driven by the quest for political and economic control over new territories. The legacies of colonialism and slavery are intertwined. As the Centre for the Studies of the Legacies of British Slavery (n.d.) states, “Colonial slavery shaped modern Britain, and we all still live with its legacies.” However, to date, accounting research has focused primarily on the colonial aspects of imperialism and has not prioritized the interconnectedness of colonialism and slavery. To remedy this oversight, researchers such as those affiliated with the Centre for the Studies of the Legacies of British Slavery (n.d.) “are now moving in the direction of more focused research on the lives of enslaved people in the Caribbean.” As Sauerbronn et al. (2021) argue, the capitalist economic expansion sought by imperial forces was powered and sustained by slavery and forced labor: “Colonialism was characterized by commercial and mercantile capitalism, which led to maritime expansion and the search for new sources of products, spices, forced labor, and precious metals” (p.2).

British4 colonialists referred to the original inhabitants of the colonies as Natives or Indigenous; these terms have since come to be interpreted in accounting research to refer primarily to First Nations peoples in Canada, Aboriginal peoples in Australia and New Zealand, and American Indians or Indigenous Americans in the United States—disregarding the caution of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples in 1982 (United Nations [UN], 1982a) on imposing postcolonial definitions of Indigeneity on Indigenous peoples. My approach considers peoples who were relocated to other lands, such as enslaved Africans in Jamaica, as Indigenous, as their history with the lands preceded the arrival of the British. In addition to adhering to the recommendations of the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP; UN, 1982a), my understanding of Indigeneity is also consistent with Weaver (2001) and Miley and Read (2021), who use self-identification and historical continuity with a precolonial past as a criterion for Indigeneity.

I return to the concept of self-identification in the next section to redefine how Indigeneity is conceptualized. For now, however, suffice it to note that accounting is central to both colonial and postcolonial definitions of who qualifies as Indigenous; consequently, the relationship between Indigenous peoples and accounting is of interest to many accounting scholars. Sauerbronn et al. (2021) argue that accounting, as an institution, helps maintain neoliberal coloniality; and although accounting is often portrayed as an objective rendering of business accounts (politically and ideologically neutral), Bakre (2008) suggests that it is a political tool for colonization. Furthermore, Bakre (2008) argues that “within the triangular relationship of colonialism, capitalism, and the resultant imperialism, financial reporting has enabled colonial and other transnational businesses to accumulate and allocate economic surpluses and safeguard the interests of colonial and other international capital” (p. 487).

While the relationships between Indigenous peoples and accounting have been examined, research in this area is primarily confined to journals such as the Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (AAAJ) and Accounting, Organizations and Society (35 of the 65 articles reviewed). Furthermore, few studies explore accountancy's (accounting, accountability, and accountants) discrimination against Indigenous peoples in countries other than the Old Commonwealth or against immigrants in countries in postcolonial times. Consequently, this study conducts a structured literature review (SLR) of studies on how accounting and/or accountants, using the tools of imperialism, colonialism, and postcolonialism, have had deleterious effects on all Indigenous peoples in former colonies and continue to negatively impact immigrants in postcolonial OECD countries. This paper is one of several that relies on the same problematization and methods comprising a larger project whose objective is to identify, review, critique, and summarize the most relevant accounting studies of discrimination and marginalization more generally to identify gaps in the literature and avenues for future research. The larger project identifies four themes: imperialism and postcolonialism (the focus of this paper), anti-Black racism (Ufodike et al., 2023), intersectionality, and diversity. Of the 161 articles reviewed for the project, 56 are on imperialism and postcolonialism. A subsequent manual search revealed 9 additional articles published between 2020 and 2023, bringing the total to 65.

Reimagining Indigeneity in Accounting Research

Defining Indigeneity and who has it is a complex exercise. Weaver (2001) identifies three facets of Indigenous identity: self-identification, community identification, and external identification. External identification—namely, when Indigenous identity is defined from a non-Indigenous perspective—is problematic because it most often reinforces a colonial approach to Indigeneity. Weaver (2001) cites “[US] federal policy makers,” for example, as imposing “their own standards of who is considered a Native person in spite of the fact that this is in direct conflict with the rights of tribes/nations” (p. 246). Most of the accounting literature recognizes only the original inhabitants of Old Commonwealth countries as Indigenous. Although the literature also recognizes that attempting to define who qualifies as Indigenous perpetuates colonialism, it nonetheless falls into the same trap by adopting a narrow, external definition of Indigeneity.

In its first session in 1982, the UN WGIP (UN, 1982a) made the case for self-identification and the decolonization of definitions of Indigeneity. This 1982 meeting marked the first time that various Indigenous nongovernmental organizations such as the International Indian Treaty Council, the World Council of Indigenous Peoples, and the Indian Law Resource Centre, came together with governments to participate in UN-led discussions on the marginalization of Indigenous peoples; these discussions eventually culminated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007.

One of the key takeaways from this first meeting was the need for self-identification. The participants “stressed that some of the main problems with existing definitions were that they had not been formulated by the Indigenous populations themselves or with their significant participation. In order to attain meaningful definitions, it was indispensable to have a significant Indigenous input” (UN, 1982a, p. 8). Simply put, in postcolonial times, imperialist forces retained the prerogative to define Indigeneity, effectively continuing the marginalization of colonization, and the WGIP sought to correct this. The WGIP concluded that the following elements should be considered when addressing the question of Indigeneity: the existence of competing systems (e.g., culture and religion), subjective elements (e.g., self-identification), and objective elements (e.g., historical continuity and conformity with social, cultural, and institutional principles, including ecological attitudes) (UN, 1982a).

Under the WGIP's recommended processes and criteria by which Indigenous peoples self-identify, many African, Asian, and South American people of former colonies would also be considered Indigenous. Similarly, being the majority of the population in any country does not end Indigeneity; otherwise, Indigenous peoples in most of Oceania—Samoa, Guam, Tonga, Kiribati, and Fiji, to name a few countries—would not be Indigenous. Yet OECD-UN member countries have perpetuated the exclusion of Indigenous peoples in countries other than the Old Commonwealth from recognition as Indigenous. In the case of Africa, Sy and Tinker (2006) argue that “colonial and post-colonial ideologies have been integral to perpetuating a one-sided version of human development which denies a central role to Africa” (p. 112). They explicitly link colonialism and slavery and implicitly make a connection to accountancy by noting the specter of compensation: “A history that overlooks Africa, virtually excluding it from the map, makes it easier for colonial powers to evade recognizing moral and economic responsibility for the institution of slavery. Even an apology for slavery has been unforthcoming for fear that it might affect litigation and compensation” (Sy & Tinker, 2006, p. 112).

The 1982 UN WGIP session was the first global forum with the participation of governments to acknowledge certain rights of Indigenous peoples. It is noteworthy that the Anti-Slavery Society for the Protection of Human Rights was acknowledged at this meeting as dealing with Indigenous populations; however, slavery and Indigeneity have since been decoupled. The reasons are clear: economics. In 1981, the global movement to address colonial injustices against Indigenous peoples was initiated at the UN through a commissioned study of the problem of discrimination against Indigenous populations, with José Martínez Cobo as special rapporteur (UN, 1982b). Two aspects of Cobo's report stand out: first, he argued that Indigenous peoples had to be the original inhabitants of the colonized lands; second, he described Indigenous peoples as overcome or dominated by settlers. Cobo's argument that Indigenous peoples had to be original inhabitants was superseded by the UN WGIP in 1982, which held instead that the inhabitants of the territory at the time of the arrival of new groups of people (of a different culture) were to be known as Indigenous. The ensuing debate on how to define Indigenous status showed that pushback by Australia, the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Mexico came down to an economic basis for Indigeneity; these countries were concerned that granting Indigenous status would entail the awarding of benefits, which would create an expense for governments (UN, 1982b). The UN WGIP's and UNDRIP's recognition of Indigenous peoples' rights (Buhr, 2012)—an asset in accounting parlance—created a liability for governments, as the benefits linked to those rights were also attributable to past fiscal periods.

We have seen some of these government liabilities crystalize, such as the $1.3 billion settlement between Canada and Siksika Nation, one of the largest land claim settlements in Canadian history (Prime Minister of Canada, 2022). We have also seen assets adjudged to be exploitative such as the asset created by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, which established the Alaska Native Corporations and issued the shares to Alaskan Natives in exchange for all land claims (Thornburg & Roberts, 2012). In both examples, acknowledging Indigeneity came with recognizing rights and imposing obligations on governments.

The decolonization of research and education requires an acknowledgment of Black Indigeneity and the exclusion of Indigenous groups in Africa, South America, Asia, and elsewhere as well as the interconnectedness of colonization and slavery. Colonizers referred to the inhabitants of African colonies as Native, Indigenous, or Black in much the same way that Indigenous peoples were described in the Old Commonwealth. For instance, the Protection Board of New South Wales in Australia used fractions of Blackness to determine benefits eligibility for Aboriginal peoples (Greer, 2009), who today are not identified as Black peoples.

Colonialism was premised on a two-nation approach: the notion that one nation was advanced and developed and the other was “underdeveloped and in need of aid” (Sy & Tinker, 2006, p. 112). The view of Pygmies as Indigenous peoples, for example, may stem from them being perceived as recently discovered and therefore “underdeveloped.” This colonial pedagogy reinforces the idea that Africa (and Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, for that matter) was “discovered” and ignores the existence and reality of those who inhabited the lands before the arrival of European colonialists. Said (1993, cited in Gallhofer & Chew, 2000) finds the theme of discovery among novelists of the imperialist era, who, he notes, share a “standing interest in what was considered a lesser world, populated with lesser people of color, portrayed as open to the intervention of so many Robinson Crusoes” (p. xviii). In the countries of the Old Commonwealth, Neu (2000a, 2000b), Greer (2009), and Neu and Graham (2004), among others, document these colonial beliefs that certain places were underdeveloped, in need of discovery and aid. In Africa, Sy and Tinker (2006) argue that this two-nation ideology was officially adopted by the Berlin Conference on Africa of 1884–1885 and thereafter by its successors, the League of Nations and the UN.5 Prior to the Berlin Conference, however, “80 percent of Africa, composed of a thousand quite distinct indigenous languages and regions, was under traditional and local control. … In this paternalistic vision [of the Berlin Conference], the colonial powers were destined to lead, and the colonized were condemned to follow—as protectorates” (Sy & Tinker, 2006, p. 112).

Hence, in the spirit of decolonization, the current study also incorporates colonial and postcolonial studies in Africa, the British West Indies, and other parts of the Caribbean and South America. Jamaica is an interesting case study of how Indigenous peoples from Africa would qualify as Indigenous to the island as their arrival predates British colonialism. Jamaica is the largest island in the British West Indies, and over 2 million enslaved people from Nigeria (Igbo, Ibibio, and Yoruba), Ghana (Akan and Ashanti), and the Central African Republic were forced into slavery in Jamaica. Jamaica was colonized first by the Spaniards between 1494 and 1655 and subsequently by the British between 1670 (when the Treaty of Madrid was signed) and 1962, when Jamaica obtained independence (Embassy of Jamaica, n.d.). At the time of the Spanish conquest, Indigenous Jamaicans were Taino Indians; however, the Taino were enslaved by the Spaniards shortly after the Spaniards established their colony in 1510, and within 50 years of the Spanish conquest, the Taino had been exterminated entirely due to exploitation, starvation, and the introduction of European diseases from which they had no immunity (Embassy of Jamaica, n.d.). The Spaniards started importing enslaved Africans to Jamaica in 1513. As such, at the time of the arrival of the British, there were many Indigenous African Jamaicans, many of whom also fought against the British invasion in 1655.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, I discuss my method, followed by summaries of two previous relevant SLRs. Next, I present my findings, starting with my theoretical thematization—the sociology of exclusion and the sociology of inclusion—followed by the subthemes. The paper ends with a discussion and conclusion that presents my observations and suggestions for future research.

2 METHOD

As part of the larger knowledge synthesis project on discrimination and accountancy, I performed an SLR following Massaro et al.'s (2016) and Roussy and Perron's (2018) approaches, which entail writing a literature review protocol, developing the research questions to be addressed by the SLR, determining the types of studies to be included, carrying out a literature search, measuring each article's impact, defining an analytical framework to be used, testing both the reliability and validity of the literature review, coding and analyzing the data, and developing research questions to be answered in future research.

I reviewed accounting articles (including auditing studies) published in the ABI/INFORM Global database ID 1000001 from 1972 to 2020, irrespective of their method or theoretical perspective. The ABI/INFORM Global database is a leading source for disseminating research studies and measuring their impact within the field of accounting studies, which are classified in this database as subjects 4100–4199. This search yielded 161 papers for the total project, 56 of which were identified as fitting the imperialism and postcolonialism theme—the subject of this article. Following this step, I manually searched the database for papers published from 2020 to 2023, which resulted in the inclusion of 9 additional papers in the imperialism and postcolonialism theme. Sixty-five papers were selected for analysis and coding. See Ufodike et al. (2022) for a comprehensive description of my SLR method.

My thematization involved four steps consistent with Yin's (2009) approach of examining theoretical propositions, creating a description, using a mixture of quantitative and qualitative data, and examining rival theories. My analysis and coding relied on an iterative process (Yin, 2009) of checking, comparing, and theorizing the findings of the selected articles to ensure methodological rigor. First, I exported the references to Covidence, a tool that enhances the reliability of SLRs. Second, I applied various theoretical insights to the data and coded the data using in vivo texts (direct quotations). Third, I applied abstractions and assigned each article a preliminary theme. My initial three themes were (1) imperialism and accounting in OECD countries, (2) imperialism and accounting in former British colonies, and (3) non-Western accounting and emancipation. Finally, after all the papers were assigned an initial theme, I reanalyzed the identified themes to ensure clear delineation. My initial thematization included an analysis of each article by its theory, method, topic, key question, and key finding. My analysis for the second round of thematization was expanded to include each article's setting or country, level of study (country or organization), and initial themes. This additional coding enabled me to further reorganize my research to four final categories by splitting the non-Western accounting and emancipation subtheme into two separate subthemes (Western accounting and accountability and emancipation) and reorganizing the other two preliminary subthemes more aptly.

- Western accounting and accountability (32),

- Professionalization (8),

- Emancipatory accounting (3), and

- Indigenous knowledge and accounts (22).

Following Roussy and Perron (2018), I excluded papers that were not written in English. I recognize that the internationalization of accounting research has resulted in “downplaying or marginalizing certain ways of speaking, thinking, investigating, and writing” (Gendron, 2019, p. 1)6 and must acknowledge the relevant body of work in languages other than English; however, this study was constrained by the fact that I only speak English. This reality is consistent with the finding by Buhr (2011) that five English-speaking countries account for the majority of research in this area: the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

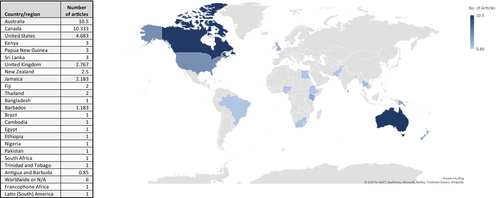

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 65 articles by country. One point signifies a focus on a single country. If an article was about more than one country, I used the appropriate fraction; for example, if an article was about Canada and England, each country received a count of 0.5 each. Figure 1 shows that Australia and Canada were the primary settings of investigation. Furthermore, the Old Commonwealth, the United Kingdom, and the United States—the same five countries referenced by Buhr (2011)—accounted for 31 (48%) of the 65 studies. Academic research in countries with a colonial history has confronted the role of accounting in dispossessing Indigenous peoples. Consequently, research in countries that have faced exacerbated societal issues related to colonialism may have benefited from local accounting researchers tackling these complex subjects in their scholarly work.

Notes: If an article is about more than one country, it is prorated accordingly. For example, an article on Canada and Britain would count as 0.5 articles for each country.

The 65 articles included in the final review were of varying impact. They were published in high-quality Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) A or A* accounting and auditing journals, well-regarded peer-reviewed journals (ABDC B or C), and, once, an unranked peer-reviewed journal (PR). My measurement criteria for the impact assessment were each journal's ABDC ranking.

Table 1 shows the article count by journal. Only 1 article was published in an unranked (PR) journal. The majority of the articles—35 of the 65—were published in two journals: AAAJ (25) and Accounting, Organizations and Society (10). The third most common journal was Critical Perspectives on Accounting, which published 6 articles. Table 2 describes the percentage distribution by journal ranking of the 105 articles for the broader project, excluding the imperialism and postcolonialism theme, and compares this distribution with the 65 articles on imperialism and postcolonialism.

| Journal name | ABDC ranking | Number of articles | Total by rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | A* | 25 | |

| Accounting, Organizations and Society | A* | 10 | 35 |

| Abacus | A | 2 | |

| Accounting & Finance | A | 1 | |

| Accounting and Business Research | A | 2 | |

| Accounting History | A | 3 | |

| Behavioral Research in Accounting | A | 1 | |

| Critical Perspectives on Accounting | A | 6 | |

| Enterprise & Society | A | 1 | |

| Financial Accountability & Management | A | 1 | |

| The Economic History Review | A | 1 | |

| The International Journal of Accounting | A | 1 | |

| Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management | A | 1 | 20 |

| Accounting Forum | B | 1 | |

| Accounting History Review | B | 1 | |

| Accounting Perspectives | B | 2 | |

| Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | B | 4 | 8 |

| Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting | C | 1 | 1 |

| International Journal of Business and Globalisation | PR | 1 | 1 |

| Total number of articles | 65 |

- Notes: The Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) journal ranking is available at https://abdc.edu.au/abdc-journal-quality-list/.

| Number of articles | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal ranking | Project (excl. imperialism) | Percentage | Imperialism and postcolonialism | Percentage |

| A* | 30 | 29 | 35 | 54 |

| A | 38 | 36 | 20 | 31 |

| B | 5 | 5 | 8 | 12 |

| C | 7 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| PR | 7 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| N/A | 18 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 105 | 65 | ||

- Notes: PR indicates unranked by ABDC, but peer-reviewed. N/A indicates unranked practitioner or non-peer-reviewed journals. The original project reviewed 161 papers, which included 56 for imperialism and postcolonialism. The imperialism and postcolonialism theme has now been expanded to incorporate 65 articles.

Table 2 shows that 83% of the imperialism and postcolonialism articles (vs. 65% for the larger project) were published in A or A* journals, compared with 2% for unranked and practitioner journals (vs. 24% for the larger project). Furthermore, none of the articles was published in a non-peer-reviewed or practitioner journal, compared with 17% for the broader project. These findings imply a greater acceptance of Indigenous studies in accounting research than in the past.

3 FINDINGS

Fourteen of the articles are in one of three special issues—two published by the AAAJ (10) and one by the Social and Environmental Accountability Journal (4). The most recent AAAJ special issue (vol. 22, no. 3), published in 2009, called for more research into accounting and subalternity. Jayasinghe and Thomas (2009) explain that subaltern communities generally have “variable degrees of literacy expression, both written and oral, that have produced imperfect or incomplete literate cultures. These subaltern communities are unable to openly express themselves, and/or are constrained in doing so. Their views and aspirations are often under-represented, if not entirely ignored, within colonial and elite documents” (p. 352).

The earlier AAAJ special issue (vol. 13, no. 3), published in 2000, called for papers that researched “accounting's role in the oppression of Indigenous peoples, Indigenous cultural perspectives upon accounting and more generally accounting's functioning in Indigenous cultural contexts” (Gallhofer & Chew, 2000, p. 256). In other words, this special issue focused on the use of accounting as a tool of economic, political, and cultural domination by the West. In particular, the systems of Western accounting practices and accountability are used to maintain the hegemonic powers of the dominant classes (Willmott et al., 1993) and perpetuate oppressive relations (Ufodike, 2017), which in turn reinforce the disempowerment of Indigenous peoples (Lombardi, 2016) across the postcolonial world. Subalternity and Indigeneity are distinct and different concepts; however, many Indigenous communities are also subaltern.

The third special issue was in the Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, which called for papers “that would move the current literature to new places, ideally positive new places” (Buhr, 2012, p. 60). Consequently, the articles in this special issue primarily focused on providing solutions to the challenges faced by Indigenous peoples or highlighting the value of Indigenous ways of doing.

My findings are organized as follows: first, I discuss two prior SLRs, by Bujaki et al. (2023) and by Salmon et al. (2023), the latter of which focused on business broadly and not just on accounting. The latter article is not classified as one of the 65 accounting studies in the imperialism and postcolonialism theme. It is nonetheless relevant to my study, as its review includes 24 accounting articles and 45 studies adopting critical theories. Following the discussion on SLRs, I present my findings, first by theoretical thematization—the sociology of exclusion and the sociology of inclusion—and then by the four research subthemes identified earlier: Western accounting and accountability, professionalization, emancipatory accounting, and Indigenous knowledge and accounts.

Previous Structured Literature Reviews

I identified two prior SLRs on Indigenous studies: the first focuses on accounting research (Bujaki et al., 2023), and the second focuses more broadly on management and organization research (Salmon et al., 2023). Bujaki et al. (2023) is the first SLR to focus exclusively on accounting research on Indigenous peoples. It highlights three prior literature reviews: Hammond (2003), Buhr (2011), and Greer and Neu (2009). Bujaki et al. (2023) exclude studies in Asia (Jayasinghe & Thomas, 2009; Miley & Read, 2021) and Africa (Degos et al., 2019; Power & Brennan, 2021) and focus on Oceania, the United States, and the former colonies of the Old Commonwealth. The SLR reviews 72 papers published between 1979 and 2019 and identifies nine broad themes: accountability and control, accounting education, accounting profession, accounting research, culture, governmentality, imperialism, postcolonialism, and social accounting.

Although critical studies effectively illuminate marginalization (i.e., the sociology of exclusion), they have been criticized for not doing enough to promote pathways to reconciliation and achieving a more inclusive society (i.e., the sociology of inclusion). Bujaki et al. (2023) opine, “Critical research in accounting tends to focus on the critique part of critical, and less so on the specific changes needed to promote social change” (p. 5).

Bujaki et al. (2023) further argue for the expansion of research that proposes avenues for the inclusion of Indigenous peoples (a view initially advanced by Buhr, 2011, 2012) and offer critical Indigenous theory (CIT) as a possible theoretical framework to assist in that quest: “More research related to accounting and Indigenous Peoples [should] adopt a CIT approach respecting Indigenous worldviews and developing suggestions for positive, forward-looking solutions” (Bujaki et al., 2023, p. 5).

In their study, Salmon et al. (2023) aspire to objectivity and state that they refrain from a critical study. They conduct an SLR analysis of 776 articles published in 253 journals between 1932 and 2021. Forty-five of these articles adopt a critical theory framework, and 24 are published in accounting journals. The SLR proposes three broad themes: cultural and epistemological elements that distinguish Indigenous peoples from their societal context; managerial and organizational aspects of Indigenous cultures; and perspectives and interactions between Indigenous peoples and other actors such as governments and firms.

Both Salmon et al. (2023) and Bujaki et al. (2023) adopt a definition of Indigenous peoples as the First Nations (in Canada), Māori (in Australia), and American Indians (in the United States). Gallhofer and Chew (2000) also recognize the groups of Indigenous peoples in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Oceania, and Pygmies as Indigenous peoples in Africa. I extend the work of these SLRs and prior studies by adopting a broader definition of Indigenous peoples consistent with the 1982 UN WGIP report discussed earlier. Furthermore, I argue that the chronology of colonialism and slavery cannot be decoupled. In aspiring to decolonize pedagogy and research, I must first highlight and explain exclusion in its current form and then strive for a sociology of inclusion. My theorization of these concepts follows.

4 THEORETICAL THEMATIZATION

My analysis employs theoretical thematization based on Llewellyn's (2003, pp. 674) five levels of theorization. Level 1, metaphors, addresses micro-empirical issues of social production. Level 2, differentiation, focuses on micro-empirical issues of social process. Level 3, concepts, focuses on meso-empirical issues of agency. Level 4, theorizing settings, “explains social, organizational or individual phenomena in their settings.” Finally, level 5, theorizing history, or more aptly structure (setting and time), explains the “large-scale and enduring aspects of the social realm (e.g. social institutions, culture, class, hierarchies and the distribution of power and resources).”

Llewellyn (2003) informs my theoretical themes, as she offers a new perspective of what counts as theory. My theoretical approach focuses on a binary meta-theoretical classification of the 65 articles based on their expressed objective(s) and findings, as focused on exclusion or inclusion. Llewellyn (2003) is apt because even if a paper does not clearly define a theoretical framework in the traditional sense (i.e., level 4 or 5), her expanded understanding of what constitutes theory allows me to deduce theory. Specifically, if the objective and findings of the paper are more focused on highlighting marginalization or exclusion, the article is classified as belonging to the sociology of exclusion. On the contrary, if the overarching objective and findings of the article are on ways to further inclusion, the article is classified as the sociology of inclusion. (I return to these two categories shortly.) Although I review some of the same articles as Llewellyn (2003) (e.g., Greer & Patel, 2000), I do not attempt a theoretical or methodological reconciliation of the articles I review with the articles she reviews. For example, Llewellyn (2003) classifies Greer and Patel (2000) as a level 1 conceptualization because they treat “yin and yang” as a metaphor. By contrast, I classify the same article as adopting a feminist approach, which ultimately highlights the incongruence between Western and Indigenous values and reveals the negative impacts of Western accounting approaches on Indigenous peoples. Consequently, I do not determine what level of theorization applies to Greer and Patel (2000) (or any other articles, for that matter), but conclude that the article's outcome highlights exclusion. In this example, the sociology of inclusion would be a meta-classification of articles that may fall under any of the five levels of Llewellyn (2003).

For the theoretical thematization, I divide the 65 articles into two groups of academic sources: the sociology of exclusion—namely, those that outline the historical, current, and legacy issues of colonialism and imperialism—and the sociology of inclusion—namely, those that focus on solutions to these problems and offer future research and policy directions. The first theme focuses on articles that illuminate marginalization in colonial or postcolonial times (i.e., the sociology of exclusion), whereas the second theme focuses on those that share with Buhr (2011) and Bujaki et al. (2023) aspirations to “move on from the grievance mode and instead focus on positive, forward-looking solutions” (Buhr, 2011, p. 141).

Sociology of Exclusion and Sociology of Inclusion

Sociology of Exclusion

The sociology of exclusion is a primarily critical and social framework for explaining systemic marginalization and institutional racism. The studies classified in this theoretical theme connect the dots between colonialism (imperialism and slavery), postcolonialism (immigration and professionalization), and accountancy. In other words, these studies are concerned with the relationship between the origins of exploitation by capitalist businesses, modern exclusion, and accountancy. As a business, imperialism is the business of accumulating surpluses (Bakre, 2008; Sauerbronn et al., 2021). Slavery is not only the business of suffering, but also the business of accumulating surpluses by maximizing productivity and achieving exceptional profit and losses based on low cost and free inputs—specifically, labor. Immigration is the business of human mobility, while professionalization is the business of gatekeeping.

Sociology of exclusion studies explain why Indigenous peoples globally experienced various forms of oppression, subjugation, and marginalization by European imperialism. This includes the Indigenous peoples in what is now known as Canada (Neu, 2000a, 2000b; Neu & Graham, 2006), Australia (Carnegie & Edwards, 2001; Chew & Greer, 1997; Evans & Jacobs, 2010), and New Zealand (Gallhofer et al., 2000), as well as those of various countries in Africa (Sian, 2007, 2011), Southeast Asia (Adams et al., 2007; Ashraf & Ghani, 2005; Constable & Kuasirikun, 2007; Kuasirikun & Constable, 2010), Oceania (Davie, 2000; Davie & McLean, 2017; Finau et al., 2019), South America (Sauerbronn et al., 2021), and the Caribbean (Annisette, 2000; Bakre, 2008).

In colonial times, oppression was facilitated by accounting and notions of accountability. As Jacobs (2000) argues, “Western forms of accountability tend to be oppressive for ethnic minorities and have a strong colonizing potential in relation to indigenous cultures” (pp. 362–363). In postcolonial times, marginalization is perpetuated by institutions such as legislatures (Ufodike et al., 2023) and professional accounting bodies (Annisette, 2000; Annisette & Trivedi, 2013; Ashraf & Ghani, 2005; Hammond, 2003; Poullaos, 2009, 2016). As Bakre (2008) finds, although the British Empire propagated discrimination based on race in colonial times, the independence of the colonies did not end discriminatory practices. The sociology of exclusion helps explain how, in postcolonial times, racialized immigrants continue to experience marginalization in the new economies, the cumulative effect being the perpetuation of oppressive relations spanning eras. In postcolonial times, discrimination continues based on class, gender, immigration status, and ethnicity (Annisette & Trivedi, 2013; Bakre, 2008; Sian, 2006).

My analysis of these studies reveals the use of various theories. Table 3 shows the 43 papers reviewed for the sociology of exclusion by theory, country, and level of analysis (organization, institution, or society). The studies synthesized in this paper primarily use social/critical theories, namely—imperialism, colonialism, and postcolonialism, three subjects that have been documented by accounting academics since 2000. In deciding on the appropriate theoretical theme, I look at the combination of the research purpose, theoretical and methodological approach, and findings in totality to make a binary decision on classifying between exclusion or inclusion. Although several articles have a dual focus (e.g., most articles reviewed for the sociology of inclusion logically start by unpacking a form of exclusion), they are categorized based on their primary focus.

| Theory | Level of analysis | Author(s) | Title | Year | Journal | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical theory | Organization | Alawattage and Wickramasinghe | Weapons of the weak: Subalterns’ emancipatory accounting in Ceylon Tea | 2009 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Sri Lanka |

| Institution | Annisette | Imperialism and the professions: The education and certification of accountants in Trinidad and Tobago | 2000 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Trinidad | |

| Society | Annisette and Trivedi | Globalization, paradox and the (un)making of identities: Immigrant Chartered Accountants of India in Canada | 2013 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Canada | |

| Bakre | Financial reporting as technology that supports and sustains imperial expansion, maintenance and control in the colonial and post-colonial globalisation: The case of the Jamaican economy | 2008 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Jamaica | ||

| Burchell et al. | The roles of accounting in organizations and society | 1980 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Global | ||

| Carnegie and Edwards | The construction of the professional accountant: The case of the Incorporated Institute of Accountants, Victoria (1886) | 2001 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Australia | ||

| Chew and Greer | Contrasting world views on accounting: Accountability and Aboriginal culture | 1997 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Australia | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Davie | Accounting for imperialism: A case of British-imposed indigenous collaboration | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Fiji |

| Davie and McLean | Accounting, cultural hybridisation and colonial globalisation: A case of British civilising mission in Fiji | 2017 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Fiji | ||

| Evans and Jacobs | Accounting: An un-Australian activity? | 2010 | Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management | Australia | ||

| Ezzamel | Accounting for the activities of funerary temples: The intertwining of the sacred and the profane | 2005 | Accounting and Business Research | Egypt | ||

| Ferry et al. | Accounting colonization, emancipation and instrumental compliance in Nigeria | 2021 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Nigeria | ||

| Finau et al. | Agents of alienation: Accountants and the land grab of Papua New Guinea | 2019 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Papua New Guinea | ||

| Fleischman et al. | The efficacy/inefficacy of accounting in controlling labour during the transition from slavery in the United States and British West Indies | 2011 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | United States, Caribbean (Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica), United Kingdom | ||

| Fleischman et al. | Plantation accounting and management practices in the US and the British West Indies at the end of the slavery eras | 2011 | The Economic History Review | United States, Caribbean (Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica), United Kingdom | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Gibson | Accounting as a tool for Aboriginal dispossession: Then and now | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Australia |

| Greer | “In the interests of the children”: Accounting in the control of Aboriginal family endowment payments | 2009 | Accounting History | Australia | ||

| Greer and Patel | The issue of Australian indigenous world-views and accounting | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Australia | ||

| Hardman | Canberra to Port Moresby: Government accounting and budgeting for the early stages of devolution | 1984 | Accounting & Finance | Papua New Guinea | ||

| Heier | Accounting for the business of suffering: A study of the antebellum Richmond, Virginia, slave trade | 2010 | Abacus | United States | ||

| Jacobs | Evaluating accountability: Finding a place for the Treaty of Waitangi in the New Zealand public sector | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | New Zealand | ||

| Jayasinghe and Thomas | The preservation of indigenous accounting systems in a subaltern community | 2009 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Sri Lanka | ||

| Kuasirikun and Constable | The cosmology of accounting in mid 19th-century Thailand | 2010 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Thailand | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Lehman et al. | Immigration and neoliberalism: Three cases and counter accounts | 2016 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | United States, Canada, and United Kingdom |

| Mihret et al. | Accounting professionalization amidst alternating state ideology in Ethiopia | 2012 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Ethiopia | ||

| Neu | Accounting and accountability relations: Colonization, genocide and Canada's first nations | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Canada | ||

| Neu | “Presents” for the “Indians”: Land, colonialism and accounting in Canada | 2000 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Canada | ||

| Neu and Graham | Accounting and the holocausts of modernity | 2004 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Canada | ||

| Neu and Graham | The birth of a nation: Accounting and Canada's First Nations, 1860–1900 | 2006 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Canada | ||

| Oldroyd et al. | The culpability of accounting practice in promoting slavery in the British Empire and antebellum United States | 2008 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | United States, Caribbean (Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica), United Kingdom | ||

| Poullaos | Profession, race and empire: Keeping the centre pure, 1921–1927 | 2009 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Britain (Scotland, Ireland, and England) | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Poullaos | Canada vs. Britain in the imperial accountancy arena, 1908–1912: Symbolic capital, symbolic violence | 2016 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Britain and Canada |

| Power and Brennan | Corporate reporting to the crown: A longitudinal case from colonial Africa | 2021 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | South Africa | ||

| Rodrigues et al. | Documenting, monetising and taxing Brazilian slaves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries | 2015 | Accounting History Review | Brazil | ||

| Rosenthal | From memory to mastery: Accounting for control in America, 1750–1880 | 2013 | Enterprise & Society | United Kingdom, Jamaica, Barbados | ||

| Sian | Operationalising closure in a colonial context: The Association of Accountants in East Africa, 1949–1963 | 2011 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Kenya | ||

| Sy and Tinker | Bury Pacioli in Africa: A bookkeeper's reification of accountancy | 2006 | Abacus | Global | ||

| Thornburg and Roberts | “Incorporating” American colonialism: Accounting and the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act | 2012 | Behavioral Research in Accounting | United States | ||

| Tyson et al. | Theoretical perspectives on accounting for labor on slave plantations of the USA and British West Indies | 2004 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | United States/British West Indies | ||

| Ufodike et al. | A knowledge synthesis of anti-Black racism in accounting researcha | 2023 | Accounting Perspectives | Australia | ||

| Institutional theory | Society | Baker and Schneider | Accountability and control: Canada's First Nations reporting requirements | 2015 | Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting | Canada |

| Neo-institutional theory | Society | Degos et al. | The history of accounting standards in French-speaking African countries since independence: The uneasy path toward IFRS | 2019 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Francophone Africa |

| N/A | Society | Ahraf and Ghani | Accounting development in Pakistan | 2005 | The International Journal of Accounting | Pakistan |

- Notes: aStructured literature review.

Only 1 of the 43 articles reviewed for the sociology of exclusion—Greer and Patel (2000)—adopted a unique critical stance—specifically, a feminist methodology. Greer and Patel (2000) argue that the core Indigenous yin (feminist) values of sharing, relatedness, and kinship are incompatible with Western accounting and accountability systems based on the masculine (yang) values of objectivity, efficiency, productivity, and logic. While the article also argues for the value of Indigenous knowledge, the dominant focus is the conflict of value systems that render Western accounting/accountability systems ineffective in achieving meaningful social and economic outcomes for Indigenous peoples. As such, the paper is classified under the sociology of exclusion.

Of the 43 papers classified as the sociology of exclusion, only 1 does not adopt a social/critical conceptualization. This paper is Degos et al. (2019), which adopts neo-institutional theory. Furthermore, only 2 articles carry out their analyses at the organizational and institutional levels—namely, Alawattage and Wickramasinghe (2009) and Annisette (2000), respectively. The level of analysis for all the others is society. This finding suggests that social theories (levels 4 and 5 of Llewellyn, 2003) are well suited for studies that illuminate social exclusion and marginalization. However, this finding also presents an opportunity for researchers to apply other theoretical perspectives and methods to their research that may result in findings weighted more toward solutions and inclusion.

Sociology of Inclusion

Table 4 shows that 22 studies are classified as the sociology of inclusion. These studies rely on multiple theoretical perspectives to simultaneously identify and propose solutions to marginalization. Consequently, CIT, practice theory, and action research all lend themselves to the sociology of inclusion, as do various forms of emancipatory research. The studies classified as the sociology of inclusion show more theoretical fluidity than those classified as the sociology of exclusion. Seven of the 22 articles adopt a theoretical lens other than critical theory—specifically, practice theory (1 article), theory of Indigenous alternatives for development (2 articles, including Bujaki et al., 2023), grounded theory (2 articles, Rkein & Norris, 2012, Rossingh, 2012), actor-network theory (1 article, Ufodike et al., 2022), and common pool theory (1 article, Ufodike et al., 2021). One study, Dillard and Reynolds (2008), adopts a feminist framework resulting in “inclusion” findings. Dillard and Reynolds (2008) discuss the Acoma myth of creation, which adopts a feminist (spiritual, emotional, and experiential) archetype story about creation and community. This message facilitates social integration, and although the article finds that the Acoma version of creation was supplanted by the Spaniards' Christian patriarchal ways of understanding, their dominant argument is that First Peoples' ancient creation myths worldwide are similar in their vision of unified beginnings and can inform our understanding and offer guidance on new ways of knowing and doing.

| Theory | Level of analysis | Author(s) | Title | Year | Journal | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice theory | Organization | Adams et al. | The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh | 2007 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Bangladesh |

| Gallhofer et al. | Some reflections on the construct of emancipatory accounting: Shifting meaning and the possibilities of a new pragmatism | 2019 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Global | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Baker et al. | Programme devolution accountability for First Nations: To whom for what? | 2012 | International Journal of Business and Globalisation | Canada |

| Bujaki et al. | A systematic literature review of Indigenous Peoples and accounting research: Critical Indigenous theory as a step toward relationship and reconciliation | 2023 | Accounting Forum | Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United States, Oceania | ||

| Constable and Kuasirikun | Accounting for the nation-state in mid nineteenth-century Thailand | 2007 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Thailand | ||

| Craig et al. | The concept of taonga in Māori culture: Insights for accounting | 2012 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | New Zealand | ||

| Critical theory | Society | Dillard and Reynolds | Green owl and the corn maiden | 2008 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | United States (New Mexico) |

| Gallhofer and Chew | Introduction: Accounting and Indigenous peoples | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Global | ||

| Gallhofer et al. | Developing environmental accounting: Insights from Indigenous cultures | 2000 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Australia | ||

| Lombardi | Disempowerment and empowerment of accounting: An Indigenous accounting context | 2016 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | Australia | ||

| Miley and Read | Entertainment as an archival source for historical accounting research | 2021 | Accounting History | Cambodia | ||

| Sauerbronn et al. | Decolonial studies in accounting? Emerging contributions from Latin Americaa | 2021 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Latin America | ||

| Sian | Inclusion, exclusion and control: The case of the Kenyan accounting professionalisation project | 2006 | Accounting, Organizations and Society | Kenya | ||

| Sian | Reversing exclusion: The Africanisation of accountancy in Kenya, 1963–1970 | 2007 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Kenya | ||

| Wickramsinghe | Getting management accounting off the ground: Post-colonial neoliberalism in healthcare budgets | 2015 | Accounting and Business Research | Sri Lanka | ||

| Actor network theory | Society | Ufodike et al. | Network accountability in healthcare: A perspective from a First Nations community in Canada | 2022 | Accounting Perspectives | Global |

| Common pool theory | Society | Ufodike et al. | First Nations gatekeepers as a common pool health care institution: Evidence from Canada | 2021 | Financial Accountability & Management | Canada |

| Grounded theory | Society | Rkein and Norris | Barriers to accounting: Australian Indigenous students’ experience | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | Australia |

| Rossingh | Collaborative and participative research: Accountability and the Indigenous voice | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | Australia | ||

| Theory of Indigenous alternatives for development | Society | Brown and Wong | Accounting and accountability of Eastern Highlands Indigenous cooperative reporting | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | Papua New Guinea |

| N/A | Society | Buhr | Indigenous peoples in the accounting literature: Time for a plot change and some Canadian suggestions | 2011 | Accounting History | Canada, United States, New Zealand, Australia |

| N/A | Society | Buhr | Indigenous peoples: Accounting and accountability | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | Global |

- Notes: aStructured literature review.

Table 4 shows that 2 of the 22 studies have an organizational setting, compared with 2 of 43 (see Table 3) in the case of the sociology of exclusion. Table 4 shows that 2 of the studies employ ethnomethodology (observation and participatory methodology)—level 3 conceptualization as per Llewellyn (2003)—and 5 rely on interviews as part of case studies—level 1, 2, or 3 theorizations as per Llewellyn (2003). Seven of the 22 articles utilize primary data, compared with 1 of 43 for the sociology of exclusion.

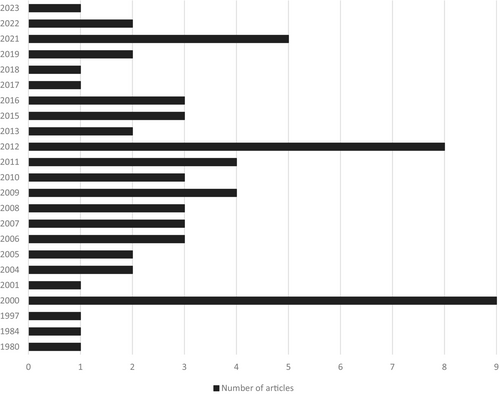

Figure 2 shows that only 2 articles were published before 1995 and that the period between 2000 and 2014 saw the most research output. The first article, by Burchell et al. (1980), argues that accounting is neither objective nor purpose-free, and the second, by Hardman (1984), investigates the devolution of responsibility for social programs to Indigenous communities. The articles categorized as the sociology of inclusion are primarily anchored in the Hardman (1984) perspective that accounting is not value-free, and many of the sociology of inclusion articles, given their approach to finding ways to achieve empowerment and agency, are related to principles of devolution—agency, self-governance, and highlighting Indigenous knowledge.

Table 4 shows that only 13 articles employ primary data or literature reviews as methods. Four are literature reviews, including two SLRs (Bujaki et al., 2023; Ufodike et al., 2023), and 8 rely on interviews or ethnomethodology (observation or participatory research). Llewellyn (2003) argues that “structural phenomena such as social institutions, culture, and the distribution of power and resources are not directly observable from the standard methods of qualitative research (i.e., interviews, focus groups, and participant observation) hence the greater reliance on rational argumentation (rather than empirical research)” (p. 677).

Table 5 shows the methodological distribution of the articles. Of the 43 articles classified as the sociology of exclusion, only Alawattage and Wickramasinghe (2009) use interviews. By contrast, of the 22 papers categorized as the sociology of inclusion, 7 use interviews, observation, or participatory research.

| Author(s) | Title | Year | Journal | Ranking | Framework | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jayasinghe and Thomas | The preservation of indigenous accounting systems in a subaltern community | 2009 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | A* | Exclusion | Interviews |

| Adams et al. | The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh | 2007 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | A* | Inclusion | Interviews |

| Lombardi | Disempowerment and empowerment of accounting: An Indigenous accounting context | 2016 | Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal | A* | Inclusion | Interviews |

| Ufodike et al. | First Nations gatekeepers as a common pool health care institution: Evidence from Canada | 2021 | Financial Accountability & Management | A | Inclusion | Interviews |

| Brown and Wong | Accounting and accountability of Eastern Highlands Indigenous cooperative reporting | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | B | Inclusion | Observation/textual analyses |

| Rkein and Norris | Barriers to accounting: Australian Indigenous students' experience | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | B | Inclusion | Interviews |

| Rossingh | Collaborative and participative research: Accountability and the Indigenous voice | 2012 | Social and Environmental Accountability Journal | B | Inclusion | Participative methodology |

| Ufodike et al. | Network accountability in healthcare: A perspective from a First Nations community in Canada | 2022 | Accounting Perspectives | B | Inclusion | Interviews |

| Buhr | Indigenous peoples in the accounting literature: Time for a plot change and some Canadian suggestions | 2011 | Accounting History | A | Inclusion | LR |

| Sauerbronn et al. | Decolonial studies in accounting? Emerging contributions from Latin America | 2021 | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | A | Inclusion | LR |

| Bujaki et al. | A systematic literature review of Indigenous Peoples and accounting research: Critical Indigenous theory as a step toward relationship and reconciliation | 2023 | Accounting Forum | B | Inclusion | SLR |

| Ufodike et al. | A knowledge synthesis of anti-Black racism in accounting research | 2023 | Accounting Perspectives | B | Exclusion | SLR |

- Notes: LR indicates literature review. SLR indicates structured literature review.

Modern Multiculturalism

As previously discussed, imperialism and colonialism “involve political and economic control over a dependent territory” (Kohn & Reddy, 2023, p. 1) and are about dominating and subjugating others who were deemed inferior. The basis for European imperialism—the dispossession and subjugation of others—was the Doctrine of Discovery, which stated that any lands not inhabited by Christians—the subjects of a European Christian monarch—were “empty” and available for colonization. The implication was that non-Christian Natives were of significantly lower or even nonhuman status (Ufodike & Vredenburg, 2020). Oppression often precedes subjugation because colonial oppression manifests several effects, including the “resistance struggles of various peoples and political movements” (Sauerbronn et al., 2021, p. 3). Consequently, resistance often results in imperialist efforts to suppress the resistance to maintain their dominion over the lands in question. Sian (2007) argues that “the race-based system of privilege constructed and operated in the colonial period is inextricably linked with the struggle for political power and the social and economic reforms” (p. 838).

Although there are similarities in the nature of oppression faced by Indigenous peoples worldwide, it is important to highlight a crucial distinction between the Indigenous experience with European immigration in the countries of the Old Commonwealth and the experience of Indigenous peoples elsewhere. The societies of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand became multicultural societies (where Indigenous populations became a minority) with the arrival of the British and other European settlers, whereas Indigenous peoples elsewhere (e.g., in Africa) may have been the majority of the population in their multicultural societies.

With the wave of immigrants during the colonial era, European imperial powers sought to eradicate the cultures they met and supplant Indigenous ways of knowing and doing with their own—not gradually, through fusion over ages, but forcefully and oppressively in a compressed period, leading to charges of genocide (see Neu, 2000a). The Europeans who settled in the Old Commonwealth then sought to exclude subsequent racialized non-European immigrants from participating in the wealth of the new countries.

In postcolonial times, after generations of immigration to the new country, immigrants may see their culture become fused or gradually influence the dominant culture. The Indigenous experience with multiculturalism in the Old Commonwealth is different. The mass migration from Europe over a relatively short time, coupled with strategies to eradicate Indigenous cultures, resulted in Indigenous peoples in the Old Commonwealth becoming a minority of the population on their own lands, in contrast to the African Indigenous experience, for example, where the Indigenous peoples remained as the majority even as colonies were settled and after the end of colonial rule. This meant that several African colonies, through nationalization and other efforts, have been able (or are actively seeking) to restore their cultures or achieve inclusion in accountancy (Mihret et al., 2012; Sian, 2007, 2011).

Subthemes

In total, only 12 of the 65 articles rely on primary data (Table 5), which highlights the methodological challenge of accessing Indigenous sites faced by non-Indigenous researchers. While the method adopted to conduct research has implications for the nature of the research findings (inclusion vs. exclusion, in this case), there are opportunities for more research that employs primary data.

Table 6 shows that approximately 68% (44 of 65) of the articles reviewed were published between 2000 and 2014, driven by three special issues, which published 14 of the 44 (32%) articles. Interest in the subject appears to be dwindling, as the total number of articles published between 2015 and 2019 is the lowest since the early 2000s.8 However, there also appears to be a pivot toward a sociology of inclusion following Buhr (2012) and Social and Environmental Accounting's special issue calling for a shift to research that highlights the agency of Indigenous peoples and Indigenous ways of knowing and doing. Consequently, 8 of the 17 (47%) articles published since 2015 are sociology of inclusion, compared with 14 of the 47 (30%) published before that.

| Article count by year of publication | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtheme/theme | Description | No. of articles | 1980–1984 | 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2009 | 2010–2014 | 2015–2019 | 2020–2023 |

| Western accounting | Studies (primarily colonial) that examine the legacy of accountancy in former colonies | 31 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Emancipation | Studies that examine how accounting practices (can) offer solutions to societal issues | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Indigeneous knowledge | Studies (primarily decolonial) that examine Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Professionalization | Studies (primarily postcolonial) that highlight exclusion by and through the accounting profession | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Sociology of exclusion | 43 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| Western accounting | Studies (primarily colonial) that examine the legacy of accountancy in former colonies | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Emancipation | Studies that examine how accounting practices (can) offer solutions to societal issues | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Indigineous knowledge | Studies (primarily decolonial) that examine Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing | 17 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | |||||

| Professionalization | Studies (primarily postcolonial) that highlight exclusion by and through the accounting profession | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Sociology of inclusion | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 65 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 15 | 17 | 10 | 8 | |

Further analysis of Table 6 also shows the number of articles published on each of the four subthemes by period. The articles classified in the Western accounting and accountability subtheme investigate the use of accounting and accountability constructs to dispossess Indigenous peoples or the cultural conflicts and tensions that Western standards of accountability create with Indigenous values. Emancipation studies highlight how accounting can be mobilized for an emancipation project or document the nationalization and localization of accounting practices. Indigenous knowledge and accounts studies highlight Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing as well as how Indigenous accounts, accounting, and accountability practices can further societal knowledge. Lastly, the professionalization subtheme documents how the professional accounting bodies in colonies went from excluding racialized peoples to minimally including them in more recent times. Next, I present my findings on each subtheme.

Western Accounting and Accountability

Studies in this subtheme examine the colonial legacy of accountancy in former British colonies. These articles primarily highlight exclusion (31 of 32 articles). These authors often explore these issues within the concepts of Western accounting, accountability, and accountants through the lenses of Bourdieu (Finau et al., 2019; Poullaos, 2009) and Foucauldian governmentality (Neu, 2000a, 2000b; Neu & Graham, 2004, 2006). Their aims are to foreground the harmful effects of accounting on Indigenous peoples through either marginalization or dispossession or examine how accounting was used to disempower (Gibson, 2000; Lombardi, 2016) and alienate (Finau et al., 2019) Indigenous peoples (e.g., through nonpermanent dispossession using land leases rather than sale). In these studies, dispossession occurred primarily by taking Indigenous wealth and resources, most notably land (for Canada, see Neu, 2000a, 2000b, and Neu & Graham, 2004, 2006; for Australia, see Gibson, 2000; for Oceania, see Davie, 2000, and Finau et al., 2019). Neu (2000a) argues that while accounting discourse was used to rationalize colonial relations, professional accounting techniques such as determining the value of land taken from Aboriginal peoples were intentionally used by the colonial government for dispossession; this is a common theme among these articles. Articles in this subtheme also find that the common custodianship of land was an integral Indigenous value.

Some studies use academic and nonacademic sources to explore the harmful effects of Western-based notions of accountability on Indigenous peoples and cultural conflicts or impacts on cultural values (Hardman, 1984). Chew and Greer (1997) and Greer (2009) provide an Australian perspective based on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, while Ufodike et al. (2022), Baker and Schneider (2015), and Baker et al. (2012) provide a Canadian perspective. Power and Brennan (2021) provide a perspective based on the British South Africa Company, and Ferry et al. (2021) provide a Nigerian perspective based on a case study of two public sector organizations. These studies find that the notions of accountability, based on a principal-agent model, are inconsistent with Indigenous culture or are ineffective. Dispossession also deprived Indigenous peoples of agency, as enslaved people in the case of the Tainos, the residential school system in Canada, boarding schools in Australia, and Native schools in New Zealand.

The final group of studies investigates the role of accountants (Finau et al., 2019; Oldroyd et al., 2008) or accounting (Fleischman et al., 2011a, 2011b; Heier, 2010) in slavery and plantation economies as well as how slavery shaped accounting standards (Fleischman et al., 2011a, 2011b; Rosenthal, 2013; Tyson et al., 2004). These studies are primarily conducted in the United States (Fleischman et al., 2011a, 2011b; Heier, 2010; Oldroyd et al., 2008) or British West Indies (Fleischman et al., 2011a, 2011b; Tyson et al., 2004). However, Rodrigues et al. (2015) provide a South American perspective, which is not as visible in the literature. Their study, which is important because more enslaved people were imported into Brazil (a Portuguese colony) than any other country, provides a case of non-British imperialism. Rodrigues et al. (2015) primarily rely on documentation originally written in Portuguese, expanding the Latin American context, as Sauerbronn et al. (2021) advise. A discussion of imperialism is incomplete without a discussion of slavery; while imperialism saw the largely voluntary migration of Europeans to colonies for economic reasons, these new economies were sustained by the involuntary, forced migration of enslaved Africans to the same colonies for economic reasons—namely, to provide free labor.

Oldroyd et al. (2008) appears to be the first accounting article to highlight accounting's role in achieving compensation paid to enslavers at the end of slavery. Other studies have sought to explore how accounting technologies have aided plantation economies in postcolonial times (Bakre, 2008; Fleischman et al., 2011a, 2011b). In his case study of Jamaica, Bakre (2008) examines the exploitative roles of accounting as a tool of imperialism in colonial and postcolonial Jamaica. He argues that during colonial times, Jamaica was primarily a plantation economy and that ending the slave trade did not halt imperial efforts. Rather, the emancipation of enslaved people was followed by a period of transformation along political, economic, class, ethnic, and cultural lines that aimed to continue the plantation-based economy. Emergent industries such as bauxite mining and tourism became the dominant foreign exchange earners, benefiting capitalistic corporations, multinational banks, and accounting firms. Bakre (2008) states that accounting practices were crucial elements of these ongoing colonization practices, as accountants and auditors helped legitimize the new capital generation methods and their utilization.

Similarly, Fleischman et al. (2011a, 2011b) discuss how accounting numbers were used to differentiate and discriminate against Black people during the transition from slavery to waged labor in the United States and British West Indies. They find that racial control, labor structures, and governmental mandates impacted the development of the accountancy profession and those who performed accounting functions and expanded accounting colonization in the postcolonial era.

Professionalization

Similar to the Western accounting and accountability subtheme, the studies in this subtheme highlight exclusion (six of eight articles), focusing on the postcolonial era. The articles find that exclusion has continued in postcolonial times, with discrimination based on societal relevance or class (Annisette & Trivedi, 2013), gender, immigration status (Annisette & Trivedi, 2013), and ethnicity/race (Annisette & Trivedi, 2013; Bakre, 2008; Sian, 2006). Public interest legislation that marginalizes Indigenous peoples (Ufodike, 2020), such as the Family Endowment Act of 1927 in Australia (Greer, 2009), has also played a role, as has professional closure (Ufodike et al., 2023), a form of gatekeeping equity as accountants (and other professions) are wont to do. Others highlight the role of accounting as a device of control and responsibilization. Lehman et al. (2016), for example, argue that “advanced” neoliberal governments such as colonial-era ones exercised their power through the process of responsibilization. Annisette and Trivedi (2013) argue that the Canadian government's Darwinian efforts aimed to select the “ideal” immigrant, who would then become acculturated into an ideal Canadian citizen over time, which resulted in accounting colonization being a technology of control and a tool to reduce the social and oral agency of immigrants within the points-based system.