An Exploration of Technological Innovations in the Audit Industry: Disruption Theory Applied to a Regulated Industry*

Accepted by Camillo Lento. This project is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the CAAA Research Grant Program. Thanks to Sameera Hassan for research assistance and to James Gaa, Theresa Libby, Sue McCracken, Brad Pomeroy, Adam Vitalis, our interviewees, anonymous reviewers at the 2020 CAAA Annual General meeting, and anonymous reviewers at the 2020 EAA Annual General meeting.

ABSTRACT

enTechnological innovation is increasing throughout the audit industry. Although prior research has explored how specific technological innovations have influenced the audit product and the profitability of the audit, the strategic implications of technological innovation for the audit industry have yet to be examined. To address this issue, we adopt Christensen's seminal theory of technological innovation (introduced in his 1997 book The Innovator's Dilemma) to gain insight into the results of 27 semistructured interviews with auditors and audit technical specialists. Consistent with Christensen's sustaining and efficiency strategic responses, our findings suggest that, at this time, technology is primarily being used by the audit industry to strengthen the audit industry's ability to serve mainstream clients by providing a “higher-quality” and lower-cost audit to replace menial tasks that historically have been done by junior auditors. We find that industry-disruptive new market entry is currently prevented by regulatory and professional barriers; however, strategic disruption to the audit industry appears inevitable as technology is already being used in audits of nonregulated markets by new entrants. Strategically, the audit industry will survive in its current recognizable form only if self-disruption occurs before the regulatory barriers are dropped, which requires significant upskilling in the industry to ensure that firms have the skills to be first movers whenever technological innovations are introduced.

RÉSUMÉ

frEXPLORATION DES INNOVATIONS TECHNOLOGIQUES DANS LE SECTEUR DE L'AUDIT : APPLICATION DE LA THÉORIE DES PERTURBATIONS À UN SECTEUR RÉGLEMENTÉ

L'innovation technologique joue un rôle de plus en plus important dans le secteur de l'audit. Alors que la recherche antérieure a examiné de quelle façon les innovations technologiques particulières ont influencé les produits d'audit et la profitabilité des audits, personne ne s'était encore intéressé aux conséquences stratégiques de l'innovation technologique dans ce domaine. Pour traiter cette question, nous recourons à la théorie charnière de l'innovation technologique de Christensen (présentée dans son livre de 1997 intitulé The Innovator's Dilemma) pour mieux comprendre les résultats de 27 entretiens semi-structurés avec des auditeurs et des spécialistes techniques de l'audit. Conformément aux réponses stratégiques de l'innovation de continuité et de l'innovation d'efficience de Christensen, nos résultats portent à croire qu'à l'heure actuelle, la technologie est principalement utilisée par le secteur de l'audit pour renforcer sa capacité à servir des clients ordinaires et à leur offrir des audits « de qualité supérieure » à prix réduit pour remplacer les tâches subalternes effectuées normalement par les assistants d'audit. Nous constatons que l'arrivée sur le marché de nouveaux entrants perturbateurs est entravée par des obstacles réglementaires et professionnels; toutefois, la perturbation stratégique du secteur de l'audit semble inévitable, car la technologie est déjà utilisée par les nouveaux entrants pour les audits des marchés non réglementés. Sur le plan stratégique, le secteur de l'audit survivra dans sa forme reconnaissable actuelle seulement s'il apporte les changements nécessaires avant l'élimination des obstacles réglementaires, ce qui nécessite une mise à niveau considérable des compétences dans ce secteur pour s'assurer que les entreprises ont les compétences nécessaires pour réagir dès l'introduction d'innovations technologiques.

1 INTRODUCTION

Technological disruption. Competitive pressures. Political uncertainty. We are living in a time of massive, chaotic change, and there's hardly a business or profession that hasn't been turned on its head in the last decade.

—Joy Thomas, CEO of CPA Canada (Pivot, May/June 2019)

Historically, the audit industry's adoption of technology has lagged behind that of its clients (Alles, 2015); however, more recent audit research suggests that the rate of adoption of technology in the audit industry is accelerating (i.e., Austin et al., 2021; Brennan et al., 2019; Cong et al., 2018; Cooper et al., 2019; Hsieh & Brennan, 2022; Moffitt et al., 2018; Munoko et al., 2020; No et al., 2019; Zhang, 2019; Zhaokai & Moffitt, 2019). While audit research has begun examining the effects of different technological tools on the audit product itself, the implications of the ongoing technological transformation for the audit industry are unclear.1 However, given the critical and monopolistic role the audit industry has in providing assurance essential to efficient operations of financial markets and capital allocations, it is important for the audit industry, regulators, and society in general to understand and anticipate the strategic implications of technological innovation on the audit industry as a whole (Knechel, 2021).

In this paper, we develop a theory-based understanding of the present and future implications of the adoption of technology for the audit industry. We use the lens of disruption theory (Christensen, 1997). Disruption theory is a theory of competitive response, where disruption is a process, not an event, and innovations can only be disruptive relative to something else (Denning, 2016). The theory of disruption identifies critical indicators of an industry's response to technological innovation and has been extensively used in the strategic management literature to gain insight into the transformative influence of technology on an industry (Christensen et al., 2018; Denning, 2016). Disruption theory outlines three possible technological innovations: sustaining innovations, efficiency innovations, and market-creating (disruptive) innovations.2 Sustaining technological innovations use technology to better serve the existing mainstream client base along historic product dimensions (Christensen et al., 2018; King & Baatartogtokh, 2015).3 Efficiency innovations focus on enabling the incumbent to do more with fewer resources by focusing on how the product is made (Christensen et al., 2013; Christensen & Dillon, 2020; Denning, 2015, 2016; Mezue et al., 2015). Market-creating (disruptive) technological innovation expands the market to include new customers with a transformed product at a lower price (Pistone & Horn, 2016). Christensen finds that market-creating technical innovation tends to be successful in the long term since the creation of new products and new markets, in time, transforms the industry and often usurps incumbents (Christensen et al., 2018; King & Baatartogtokh, 2015).

We apply the theory of disruption (Christensen et al., 2018) to analyze semistructured interviews we conducted with 27 audit professionals working in the field as audit technical specialists and global audit leaders of technology. Technological innovation has already started to alter the audit product, profit structure, and market for the static audit. Overall, on a strategic level, we find that a market-creating (disruptive) response to technological innovation is not yet occurring in the audit industry; instead, at the present time, audit firms throughout the industry are implementing technology to pursue sustaining-style product improvements to better cater to their mainstream customers and efficiency-style innovations to help them maintain or improve their own margins. Our interviewees recognize that the regulatory monopoly granted to auditors has insulated the audit industry from disruptive new market entry and facilitated both sustaining and efficiency responses to technological innovation throughout the audit industry. Securities regulators and reporting requirements currently restrict new competitor entry to the auditing market, which allows audit firms to reap the profits associated with technological efficiencies and attempt to develop new products for their mainstream clients. However, our interviewees are aware that this regulatory safeguard will eventually disintegrate as regulators themselves increase their comfort and proficiency with technological advances (cf. King & Baatartogtokh, 2015). It follows that the audit industry must be prepared for disruptive transformation when the regulatory barriers fall or when the usefulness of static regulated audits is supplanted by real-time financial information.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 first presents research on technological innovations used in auditing and then disruption theory as advanced by Christensen and his colleagues. Section 3 outlines our research methodology and describes our sample of interviewees. Section 4 presents the analysis of our interviews organized by the distinguishing features of technology innovation provided by disruption theory. Finally, we discuss the implications of the technical transformation of the audit industry and identify opportunities for future research.

2 BACKGROUND

Research Question

Our investigation into the strategic implications for the audit industry begins with a review of prior literature that considers the influence of specific technological innovations on the audit and on audit firms. Table 1 presents the audit papers which we rely upon in the development of our research question and in our research.

| Paper title and author | Specific technology examined | Observed state of use in practice | Industry/market implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| An examination of audit information technology use and perceived importance (Janvrin et al., 2008) | None—IT examined and broadly defined as anything that enhances an auditor's capacity to perform an audit task | Some applications were used extensively (e.g., electronic workpapers, Internet search tools) and some were not (e.g., tests of online transactions, database modeling). Adoption was greatest at Big 4 firms versus national and local firms | Some early considerations |

| A Big 4 firm's use of information technology to control the audit process: How an audit support system is changing auditor behavior (Dowling & Leech, 2012) | System to manage electronic workpapers | Fully adopted by the Big 4 firm examined | n/a (firm-level) |

| Drivers of the use and facilitators and obstacles of the evolution of Big Data by the audit profession (Alles, 2015) | Big data | Theoretical consideration of the future use of big data by audit firms | Do not specifically extend to industry/market implications |

| Technological disruption in accounting and auditing (Cong et al., 2018) | Blockchain | Editorial in nature; considers the potential impact of blockchain on the audit industry | Potential for market disruption of blockchain empowers and fuels demand for continuous assurance |

| Information technology in an audit context: Have the Big 4 lost their advantage? (Lowe et al., 2018) | IT broadly defined and examined; specific technologies include workpaper review and group brainstorming | Some technology innovations were applied in specific applications (e.g., fraud review, tests of online transactions); IT audit technologies were widely adopted, except for only-local firms | n/a |

| Robotic process automation for auditing (Moffitt et al., 2018) | RPA | The paper is editorial in nature and considers the potential impact of RPA on audit practice | n/a |

| Corporate governance implications of disruptive technology: An overview (Brennan et al., 2019) | Big data, cryptocurrency, blockchain, sharing economy, crowdsourcing | The paper is editorial in nature and considers the potential of these technologies to change corporate governance | Call for research potential for industry disruption |

| Robotic process automation in public accounting (Cooper et al., 2019) | RPA | Tax services are furthest along with adopting RPA, followed by advisory services, and then assurance services, which are furthest behind as they are only in the pilot stages. Benefits and costs of RPA implementation are considered | Considers RPA specifically |

| The role of internet-related technologies in shaping the work of accountants: New directions for accounting research (Moll & Yigitbasioglu, 2019) | Cloud services, big data, blockchain, AI | Reviews accounting literature on these technologies and puts forth future research opportunities | Call for additional research |

| Multidimensional audit data selection (MADS): A framework for using data analytics in the audit data selection process (No et al., 2019) | Data analytics, 100% population testing | Paper proposes a data analysis framework to guide population testing | n/a |

| Applying deep learning to audit procedures: An illustrative framework (Sun, 2019) | Deep learning, AI | Paper proposes a framework to guide the use of deep learning in audits | n/a |

| Contract analytics in auditing (Zhaokai & Moffitt, 2019) | Textual analysis | Paper proposes a framework for incorporating textual analysis to audit contracts | n/a |

| Intelligent process automation in audit (Zhang, 2019) | IPA, RPA, AI | Paper proposes a framework for incorporating IPA into audit tasks | n/a |

| Big data analytics and other emerging technologies: The impact on the Australian audit and assurance profession (Kend & Nguyen, 2020) | Big data, AI, robotics (i.e., drones, RPA), blockchain | Australian auditors are in the early stages of implementing big data, AI, and robotics on a consistent basis and are optimistic about the further use of these tools (e.g., helping automate previous tasks so auditors can focus more on judgment tasks) but are also concerned that these same tools may not be feasible for smaller firms. Practically speaking, blockchain is not being implemented, and there is much doubt and uncertainty about whether it will be implemented on a broad scale | Description of influence of AI and RPA—analysis is at firm level |

| The ethical implications of using artificial intelligence in auditing (Munoko et al., 2020) | AI | Secondary reporting of claims of increased investment and implementation of AI by accounting firms. Primary reporting of AI is used to conduct analytics over greater data sets and automation of audit tasks. AI usage is still in the early stages at the time of reporting, with an eye toward expanded usage | n/a (firm-level; little consideration of industry/strategic implications) |

| The data analytics journey: Interactions among auditors, managers, regulation, and technology (Austin et al., 2021) | Data analytics | Auditors' data analytics journey has started, with auditors using advanced analytics to deliver more insights to their clients and provide audit evidence. Progress is slow, sometimes because they are waiting for clients to catch up to their level of technological progress and sometimes because of a lack of clear regulation, which inhibits auditors' willingness to roll out and expand usage of data analytics | Specific to data analytics, with industry implications |

| The future of assurance in capital markets: Reclaiming the economic imperative of the auditing profession (Knechel, 2021) | Technology is used as a term to capture ways information is measured and disseminated, as well as how this information can be audited | The paper considers how auditors may adapt to facilitating more reliable information in a world of increasing data flows, which are themselves a result of technological innovations | n/a (auditor-level) |

| Issues, risks, and challenges for auditing crypto asset transactions (Hsieh & Brennan, 2022) | Cryptoassets | The paper summarizes existing guidance on how to audit cryptoassets to help highlight challenges and the risks of auditing cryptoassets | n/a (no strategic implications for industry) |

| The emergence of audit data analytics in existing audit spaces: Findings from three technologically advanced audit and assurance service markets (Kend & Nguyen, 2022) | ADA | Australian, UK, and New Zealand stakeholders' audit data analytics journey is underway, with ADA specialist teams being formed to assist core auditor teams with ADA and technical skills. Big 4 auditors are further along in the journey than non–Big 4 auditors. Impediments to completing the journey toward full adoption include cost absorption issues, as auditors struggle to convince clients to pay for the technology investment, and regulator guidance issues, as auditors are uncertain about how evidence garnered by new technologies will be assessed by regulators | Some strategic implications for industry limited to data analytics |

- Notes: ADA, audit data analytics; AI, artificial intelligence; IPA, intelligence process automation; RPA, robotic process automation.

Nineteen papers are included in Table 1, which span the period from 2008 to 2022. We find that the early papers examining technological innovation in the audit domain are primarily descriptive and exploratory in nature and focus on adoption of a particular type of innovation in a single audit firm (Alles, 2015; Cooper et al., 2019; Dowling & Leech, 2012; Janvrin et al., 2008; Moffitt et al., 2018; Moll & Yigitbasioglu, 2019). The next phase of audit research in technological innovation is advanced by several papers that propose the use of various frameworks for guiding the adoption of particular technological innovation in audit firms (Lowe et al., 2018; No et al., 2019; Sun, 2019; Zhang, 2019; Zhaokai & Moffitt, 2019). More recently, the research in technological innovation has become more focused on how specific technological innovations, such as blockchain (Hsieh & Brennan, 2022; Kend & Nguyen, 2020), artificial intelligence (AI) (Munoko et al., 2020), and data analytics (Austin et al., 2021; Kend & Nguyen, 2022) influence audit practice.4

Of particular relevance to the development of our research question is recent research by Austin et al. (2021) and Kend and Nguyen (2022), as well as Knechel (2021). In particular, Austin et al. (2021) and Kend and Nguyen (2022) investigate the technological adoption of data analytics in the financial reporting environment and find that the adoption of data analytics reduces costs and causes tension between audit firms, their clients, and regulators. They also allude to the possibility that technological adoption may alter the product provided to the audit client and undermine the pricing model of audit hours used by audit firms. In addition, Knechel (2021) highlights the need for transformation of the audit product itself, given the changes afforded by the increased information availability to the capital markets and the increased use of technology in the audit context. While these papers identify the importance of considering the influence of technological innovation on the profitability of the audit and the audit product itself, our paper builds upon this research by considering the strategic implications of the technological transformation of the audit product for the audit industry associated with these changes. Accordingly, our interest focuses on the industry-level question of the effect of the adoption of technological innovation on the audit industry. This leads to the research question for our study:

Research Question.What are the strategic implications of technological innovation for the audit industry?

Disruption Theory

Given our research question, we turn to disruption theory to provide a foundation for understanding the strategic implications of the effect of technological innovation on an industry (Christensen, 1997; Christensen & Dillon, 2020; Christensen & van Bever, 2014; Denning, 2016; Mezue et al., 2015). Disruption theory was first developed after Bower and Christensen (1995) observed the demise of the disk drive industry due to technological evolution. The early days of computing were dominated by industrial applications, and the traditional disk drive industry was developed to serve large corporate clients with deep pockets that could accommodate large mainframe computers and disk drives. With increasing technological innovation, the dominant companies in the disk drive industry sustained their position of dominance by focusing on their largest and most profitable customers and making larger drives for these customers' powerful industrial mainframes. These improvements, while appealing to large industrial customers, were quite impractical to a then-nascent segment of the market: home computing (Christensen, 1997). While the large incumbent firms in the disk drive industry were myopically focused on using technology to produce improved mainframe disk drives, other firms used technological advancements to create a new market of home computing by producing smaller disk drives that eventually displaced and disrupted the disk drive industry.

Three Forms of Innovation

Too frequently, [people] use the term [disruption] loosely to invoke the concept of innovation in support of whatever it is they wish to do. Many researchers, writers, and consultants use “disruptive innovation” to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and previously successful incumbents stumble. But that's much too broad a usage.

Market-creating innovations are the only type of innovations that can be classified as disruptive innovations and have the possibility to disrupt a market—as disruption is defined by Christensen as “an innovation that begins on the fringes of established markets and eventually comes to dominate mainstream markets” (Denning, 2015, p. 4).

Sustaining innovations make a good product better (Denning, 2016). These technological innovations are applied to improve the existing product or service dimensions and upsell more and/or better products and services to the existing customer base. A sustaining response upholds the existing trajectory of performance improvement along valued product dimensions for mainstream customers (Christensen et al., 2018; Hwang & Christensen, 2008). Sustaining innovations keep margins attractive and the market vibrant. They can improve profitability and create some top-line growth through price increases, but they typically do not create growth from new consumption, nor do they create jobs (Denning, 2016). In well-run firms, a sustaining response to technological innovation is most prevalent (Mezue et al., 2015). As a result, most companies tend to overshoot the performance needs of their customers by introducing products and services that are too expensive, sophisticated, or complicated and, at the same time, unwittingly open the door to disruptive innovations at the bottom of the market (Pistone & Horn, 2016).

Efficiency innovations are traditionally implemented to lower costs, and these savings are typically passed on to the consumer. Examples of efficiency innovations include cost reductions through Toyota's just-in-time production and Walmart's retail model (Christensen & van Bever, 2014; Mezue et al., 2015). By doing more with less, efficiency innovations eliminate jobs or outsource them to more efficient providers (Mezue et al., 2015). Efficiency innovation's goal is to retain the existing customer base by lowering the price while maintaining quality.

by which a product or service powered by a technology enabler initially takes root in simple applications at the low end of a market or new market—typically by being less expensive and more accessible—and then relentlessly moves upmarket, eventually displacing established competitors. (Christensen & Dillon, 2020, p. 22)

Market-creating innovations are initially not breakthrough innovations that dramatically alter how business is done but rather consist of products and services that are simple, accessible, and affordable, which at first are modest innovations.

A market-creating innovation offers a novel mix of attributes that at first may appeal only to those that are cost-sensitive or to new customers who were previously unable to afford products or services (Pistone & Horn, 2016). These novel attributes typically do not meet the traditional needs of large, established customers and are often viewed to be of lower quality. Over time these innovations continue to improve in quality and features and have the potential to upend the market status quo by providing solutions capable of handling more complex problems in ways that are simpler, more affordable, or more convenient than the dominant solutions of the incumbent providers (Christensen et al., 2015; Christensen et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2019; Pistone & Horn, 2016). Of note is that market-creating (disruptive) innovations are most often, but not always, initiated by new entrants to the market; however, Christensen et al. (2015) note that incumbents can also take advantage of technological innovations to anticipate new markets and forestall new entry.

The distinguishing features of the three forms of technology innovation (i.e., sustaining, efficiency, and market-creating) articulated by Christensen's theory of disruption can be summarized in three dimensions: (1) the product dimensions targeted, (2) the profit impact, and (3) the type of market impact, including the customer segment impacted (Christensen et al., 2018). A summary of the key elements and forms of innovations is presented in Table 2.

| Category | Product dimensions targeted | Profit impact | Market impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustaining innovations | Improve the quality of existing product: technical innovation increases quality on existing valued product dimensions, processes, and cost structures | Higher profit: Selling more or better product to the same customer, at the same or a higher price. As a result, margins are increased Make more money by selling additional value, including service innovations |

Market incumbents use technological innovation to improve the existing business model, with the focus on improving existing product for the existing market Known customer, mainstream: High value customer—may result in overserved customer |

| Efficiency innovations | Product often is a commodity. Generic and not subject to change. No change to product quality in response to increased entry to and competition in the marketplace. Process innovations enable the incumbent to do more with fewer resources by focusing on how the product is made | Maintain profit and free up cash flow Maintain margins in the face of increased competition and profit squeezes by streamlining the process and thereby lowering costs and eliminating jobs |

Market incumbents adopt process innovation to obtain cost efficiencies needed to maintain margins for the existing mature or declining market Known customer base: Goal is to retain existing customer base |

| Market-creating innovations | Transform the product: Initially, the product is of an inferior quality, and technological transformation provides a more affordable and accessible substitute | Lower price. Technological innovation creates a smaller, cheaper, more affordable product substitute | Unobtrusive entrants use technological innovation to serve underserved or new customers, and as a result, technological innovation creates new markets and seeds new market growth New markets and customers for which no products previously existed or were previously neither affordable nor accessible Low-value customer was previously ignored |

While disruption theory has been extensively used to investigate innovation and competitive responses in the general business literature, it has received little attention from accounting researchers. For example, Hopp et al. (2018) analyze 1,078 papers that use a disruption theory lens and find only 10 in the accounting domain. However, since its first application, the theory of disruption has been used as a lens to consider the transformative effects of technology across many industries, including excavating equipment and steel production (Christensen, 1997), semiconductors (Christensen, 2006), retailing (Christensen & Tedlow, 2000), the healthcare industry (Hwang & Christensen, 2008), and vehicles (Christensen & Raynor, 2013).6 Perhaps most relevant to the audit industry, disruption theory has been used to analyze innovations in the service sectors through investigation of management consulting (Christensen et al., 2013), colleges and universities (Christensen et al., 2011; Flavin & Quintero, 2018), retail banking (Das, 2017), and the legal industry (Pistone & Horn, 2016). Pistone and Horn's (2016) analysis of the legal industry demonstrates the early-stage impact of a market-creating technical innovation in a regulated industry and thus highlights the need to similarly examine the audit industry. The lack of application of disruption theory to the audit domain may be due to the historically slow rate of technological transformation found in the audit industry (Alles, 2015).

Recent audit research suggests that the rate of technology adoption in the audit industry is accelerating (i.e., Brennan et al., 2019; Cong et al., 2018; Cooper et al., 2019; Hsieh & Brennan, 2022; Moffitt et al., 2018; Munoko et al., 2020; No et al., 2019; Zhang, 2019; Zhaokai & Moffitt, 2019), which is likely to alter the audit product and, potentially, the audit industry significantly (cf. Denning, 2015). Firms are investing significant amounts of resources, both in terms of time and money, and the profession is critically concerned with its ability to adopt technology at a fast enough pace (Cohn, 2019; Salijeni et al., 2019). The stage of technological adoption provides an ideal setting to use disruption theory as a framework to understand the strategic influence of technological innovation on the audit industry. Consequently, an analysis of how technology is affecting the audit industry is particularly beneficial to providing an understanding of the way in which the audit industry and audit product are being transformed by technological innovation, and the trajectories and opportunities the audit industry will face in the future.

3 METHOD AND SAMPLE

We used semistructured interviews of audit professionals who were highly involved with implementation or use of audit technology in their audit firm to gather their perspectives on the implementation and effects of technology innovation on the audit and the audit industry (Horton et al., 2004).7 Given that existing accounting research indicates the rate of adoption of technology presently appears to vary significantly across the audit industry, we were concerned that there may be significant variation in the observations across different interviewees (Horton et al., 2004). With this in mind, we consider semistructured interviews to be particularly appropriate as they allow for a refinement of the interview protocol based on the discussions with the interviewees as the interview period progresses, focusing on the most important and contradictory issues to the interviewees in this setting (Horton et al., 2004).

To facilitate the creation of our interview protocol, we first reviewed the information technology literature to identify models of technology adoption (e.g., Rogers et al.'s [2014] theory of diffusion of innovation and Lai's [2017] review of adoption models) (Bédard & Gendron, 2004). These models help to highlight the potential barriers and catalysts to technology adoption at the industry level. We then considered the academic literature on technology adoption, as specifically identified in Table 1, but also included the professional press (e.g., Accounting Horizons special issues on big data [Vol. 22, No. 2, 2015] and audit data analytics [Vol. 33, No. 3, 2019]; Pivot, Simon, 2018).

Our initial protocol was broad and thorough and designed in the style of Gioia (Gioia et al. 2013, p. 19). This initial protocol was sent to an expert panel of accounting academics with expertise in assurance to provide feedback.8 We used their feedback to fine-tune the interview protocol for clarity and comprehensiveness, forming the initial interview protocol. To ensure subjects had considered all the possibilities, we provided every subject with a copy of the original protocol so they could consider as broad a set of questions as possible and address those they saw as important. Two researchers conducted all interviews either in person or via phone. Interviewees could choose to be audio recorded, or, if they preferred, the researchers would take notes during the interview. Audio recordings were used to allow the researchers to focus on the interviewees' responses and generate follow-up questions, eliminating the need to take verbatim notes. Only two of our interviewees declined to be recorded. Consistent with ethics requirements, interviewees were informed they would be speaking on conditions of anonymity such that no individual response could be traced back to them.9

We started each interview by collecting background information on each interviewee, which was used to break the ice and establish a rapport between the interviewee and the researchers, increasing trust (Bédard & Gendron, 2004). Next, we focused on the changes the interviewees were seeing within their firms and where they did not see any changes. To understand the issues from the interviewees' perspectives, we explored concerns they had with the new technological changes, what they found to be benefits, and the changes they would like to see on the horizon. Our next line of questioning had our interviewee share their professional and ethical concerns regarding the implementation of technology, and this was followed by questions regarding the interaction of technology with their clients and the adoption of technology by their teams. We followed their lead and probed the areas that they identified to be of relevance (Gioia et al., 2013; Horton et al., 2004). Finally, we asked our interviewees to highlight any areas they thought were important that we had not yet discussed (Bédard & Gendron, 2004). We revised the interview protocol to ensure we followed up on interesting themes with subsequent interviewees (Bédard & Gendron, 2004; Gioia et al., 2013; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Our refined list of questions is included in Appendix 1, which provides those questions that were used across the interviewees and were the ultimate focus of our analysis.10

After each interview, audio recordings were transcribed by a professional transcription service and edited and validated by the two interviewers. Data were anonymized. Interviewees were provided with an anonymized transcript (or researchers' notes) and asked to validate them. The copies of the interview recordings were destroyed after the transcriptions were validated by interviewees.

Obtaining the Sample

Our research question was to determine how technological innovation was influencing the audit and the audit industry, and the extent of that influence. With this research question in mind, we ensured that we captured a variety of perspectives across the industry by interviewing audit professionals of different ranks at different audit firms with different sizes. To obtain our sample, we relied upon professional contacts for introduction into audit firms throughout the audit industry (Bédard & Gendron, 2004; Power & Gendron, 2015). We concentrated our recruiting on auditing professionals and targeted audit specialists (i.e., designated accountants), audit technology leaders, and firm leaders who were involved with the use of technology throughout the audit industry in Canada. We employed a snowball technique to obtain additional contacts throughout the industry.11

In total, 27 subjects across seven firms were interviewed. The interviews were conducted between December 2018 and May 2019, with follow-up interviews starting in November 2021.12 As shown in Table 3, interviewees held positions ranging from associates to partners, as well as members of national assurance teams, members of global audit technology teams, and chief technology officers. Our interviewees in the larger audit firms ranged from partner to those at lower levels, all of whom were highly involved with technology, and included a minimum of two partners from three of the Big 4 firms, including the lead partner in charge of audit technology and a senior audit manager for all Big 4 firms. All interviewees, except one from a non–Big 4 firm, were auditing professionals, and all worked in the auditing area.13 Due to our interest in audit technology innovation, we focused our main analysis on the audit technology leaders within the firms. The nonpartner interviewees focused their responses more heavily on the mechanics of auditing and the effects of technological implementation on the audit process. Thus, our sample in the large firms enabled us to identify any deviations between the overall innovation discussed by the leaders of the firm and triangulate this with the changes observed by managers and staff (Malsch & Salterio, 2016).

| Number | Date | Rank | Firm | Interview format | Length (minutes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 5, 2018 | Partner—Tech Role | Big 4 A | Male | In person | 74 |

| 2 | December 11, 2018 | Partner | Non–Big 4 A | Male | Phone | 34 |

| 3 | January 8, 2019 | Partner | Non–Big 4 B | Male | Phone | 46 |

| 4 | January 14, 2019 | Partner—Tech Leader | Big 4 B | Male | In person | 48 |

| 5 | January 14, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 A | Female | In person | 48 |

| 6 | January 14, 2019 | Partner—Managing Partner | Big 4 A | Female | In person | 70 |

| 7 | January 14, 2019 | Partner—Tech Role | Big 4 A | Male | In person | 70 |

| 8 | January 15, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 C | Female | In person | 56 |

| 9 | January 15, 2019 | Partner | Big 4 B | Male | In person | 54 |

| 10 | January 30, 2019 | CIO (non-CPA) | Non–Big 4 B | Female | Phone | 30 |

| 11 | February 19, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 A | Male | Phone | 55 |

| 12 | February 19, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 A | Male | Phone | 49 |

| 13 | February 20, 2019 | Partner—Tech Role | Big 4 D | Female | In person | 52 |

| 14 | February 20, 2019 | Partner | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 39 |

| 15 | February 21, 2019 | Partner | Big 4 D | Male | Phone | 38 |

| 16 | February 22, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 A | Male | Phone | 54 |

| 17 | March 20, 2019 | Partner | Non–Big 4 C | Female | Phone | 30 |

| 18 | April 18, 2019 | Director | Big 4 D | Female | In person | 33 |

| 19 | April 18, 2019 | Associate | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 20 |

| 20 | April 18, 2019 | Senior Manager | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 22 |

| 21 | April 18, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 27 |

| 22 | April 18, 2019 | Senior Manager | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 20 |

| 23 | April 18, 2019 | Director | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 32 |

| 24 | April 18, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 21 |

| 25 | April 18, 2019 | Senior Associate | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 20 |

| 26 | April 18, 2019 | Manager | Big 4 D | Male | In person | 24 |

| 27 | May 8, 2019 | Senior Manager | Big 4 C | Male | Phone | 35 |

| Average interview length | 41 | |||||

We quickly found that non–Big 4 audit firms had not yet significantly embraced technological innovation. We interviewed three partners and one chief information officer (CIO) in smaller audit firms, who all observed that many clients had not yet engaged in technological transformation in their own business and, as a result, technological modification to their audit process was obstructed due to clients' lack of technical sophistication. In other words, these auditors could not bring technological innovations to their audit procedures even if they wanted to because their clients' data were simply not compatible with any technological innovations. In addition, the lack of uniformity of systems across clients impeded their ability to apply technology efficiently. All firms were investigating investment in technology, but none were at the advanced stages of the Big 4 audit firms. The CIO saw potential for technology to overtake the reporting of financial information—and, correspondingly, the audit—but had not seen this within their clients yet.

In our interviews with those working at smaller firms, saturation was achieved almost immediately. Saturation is the point at which additional interviewees did not add additional or disconfirming information or insights into the research question for a subpopulation (Neu et al., 2014). For larger firms, we interviewed a total of 23 interviewees. We found that no additional insights were gleaned after our 17th Big 4 interviewee and therefore felt we were at the point of saturation according to qualitative research recommendations (e.g., Dai et al., 2019; Malsch & Salterio, 2016; Morse, 1995, 2000; Power & Gendron, 2015). However, we continued with an additional 6 interviews that had already been scheduled and, with no new insights from these interviews, we were satisfied that we obtained saturation; thus, no further interviews were required (Gioia et al., 2013; Mason, 2010; Neu et al., 2014; Strauss & Corbin, 1994).14

Data Analysis Approach

Our primary analysis occurred after the transcription and anonymization of all interviews was completed (Austin et al., 2021; Bédard & Gendron, 2004). The data were analyzed through an iterative process independently by four members of the research team based on the interview questions, previous readings of relevant literature, and the recurring themes identified while reading interview transcripts (Anderson-Gough, 2004; Bédard & Gendron, 2004; Daoust & Malsch, 2020; Gioia et al., 2013). Consistent with Gioia et al. (2013), a large quantity of codes and categories emerged early in the research. In subsequent meetings, the research team members' independent categorization schemes were compared as a first step to seek “similarities and differences among the many categories … a process that eventually reduces the germane categories to a more manageable number” (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 20). Agreement was developed through discussion and reference to the transcripts by the development of “consensual decision rules about how various terms or phrases are to be coded” (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 22). During this process, disruption theory emerged as our theoretical lens as interviewees focused on how technology was impacting the audit industry, and the practitioner literature stressed the impending disruption of the audit (Patriquin, 2019; Rinaldi, 2019). Using this lens, we refined our categorization schemes and further refined key categories. Additional meetings were held regarding interpretations of interviews and disruption theory coding to help develop deeper insights as well as to ensure we maintained distance from the data. A coding flowchart was developed that detailed how the codes were related, and the definitions and criteria for each was then developed, reviewed, and agreed upon. Two members of the research team coded the responses—one who was involved in the interview process and one who was not—to ensure that the coding was not significantly influenced by the interviewer's closeness to the process.15 Interview transcripts were coded line by line, following the coding scheme by theme, whereby individual responses may be coded into multiple codes; codes were not assigned by question. We remained open to new themes emerging from our interviews, added additional codes as necessary during the coding process, and held further meetings to discuss and agree on changes to the coding flowchart (Ketokivi & Mantere, 2010). NVivo was used to facilitate the coding process.16 The finished codebook is presented in Appendix 3.

4 ANALYSIS

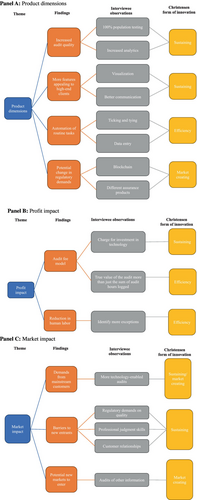

To facilitate an understanding of the data, we present a thematic map (Figure 1) that is organized according to three themes that emerged from our analysis: (1) the product dimension (Panel A), (2) the profit impact (Panel B), and (3) the market impact (Panel C). The thematic map is used to facilitate the visualization of the links between the responses of our interviewees and disruption theory as well as the subsequent conclusions we have drawn from our analysis. As shown in Figure 1, according to a disruption theory perspective, technological innovation influences three different dimensions of an industry: the product, the profitability, and the market. We map our qualitative data onto these three dimensions to organize the interviewees, assessments of the influence of innovation technology on audit practices. For each theme, we present the various observations regarding the influence of technological innovation described by our interviewees and link them to the factor affected and the type of innovation to which they correspond.

We organize the discussion of our analysis according to the three themes as presented on the thematic map: (1) product dimensions targeted, (2) profit impact, and (3) market impact.

Product Dimensions Targeted

A key differentiator between the forms of innovations presented by Christensen et al. (2018) is how technological innovations transform the core product. Alternate transformations to the core product include a change in a valued dimension, such as increasing audit quality17 (sustaining innovations), reducing product costs (efficiency innovations), and offering an alternative product that can be substituted for the given functionality (market-creating [disruptive] innovation). Regulation in the audit industry is likely to influence product transformation given that regulation dictates and defines the base level of acceptable audit product quality, limiting the feasibility of entry of a low-quality alternative to the market. However, as seen in the legal industry, transformation may still be possible.

Sustaining Innovations

Auditors are adopting sustaining innovations throughout the audit to increase the quality of the audit and the quality of the service provided to the client. The use of audit technology to audit 100% of the population may be replacing the traditional audit sampling techniques and may be a notable example of a quality improvement to the audit product. Our interviewees noted that technology was being used to increase or “enhance” the quality of the product above the base level of quality required by regulators: “So that's one benefit that we can give out, is it's a higher-quality audit” (INT23).18

We are enabling more technology in the audit. Ultimately, the clients understand how much technology we are putting in the audit and more automation and changing the way we work, then they may shorten that expectation gap because you're gonna be able to do more. (INT18)

With technology-enabled audits, the client becomes more informed about the work the auditor is doing and the assurance being provided, which allows for more informed expectations of audit quality. At the same time, the auditor can increase audit quality through the implementation of that same technology, thereby jointly reducing the expectation gap.

I think the biggest benefit of using [technology] in the audit is to be able to look at the full population, right? And to look at 100% of the population of the data and that's been the big hit with our clients. … But in this way, we're looking at the whole population and actually looking for outliers, so things that are inherently riskier, and then we pinpoint those items to look at. (INT12)

By virtue of examining entire populations of transactions as opposed to sampling, these new tools are seen to increase audit quality by increasing the quantity of the audit evidence examined.

Well, when we're testing estimates … [technology provides] the ability for us to be able to understand how sensitive these estimates are, as well as put in our own assumptions to it and see if we can challenge them. So, that's the real big value. (INT26)

The use of sensitivity testing increases audit quality and provides the auditor with meaningful insights to share with the audit client, including their audit committee, when discussing financial statement quality and risk.

I would say they are used to provide insights into their business. So, process flow of transactions or outliers and … just giving them, you get so much data, it's providing them … like turning that data into information and providing them information they didn't see within the audit evidence side of things, but we're also trying to get meaningful insights for the data we use. (INT6)

Our interviewees identified that technological innovation enhances auditors' ability to offer higher-end services to existing clients, including increased visualization of audit findings and more meaningful, value-added conversations. This ability to enhance services to the established client base is consistent with sustaining innovation on the part of the auditor incumbent: “The other real benefit is that we get a lot of conversation, like more intelligent conversation, with our clients, where we tell them, ‘FYI, look at that in your books, and that will help you going forward’” (INT26).

[We presented] … a video with a white board story of the D and A [data analytics] concept together with an engagement team member speaking to what was happening within the same video. Our clients absolutely loved it. They'd never seen such an innovative way of doing an audit procedure, but then also presenting it and demonstrating the results innovatively using graphics. (INT16)

Auditors are attempting to demonstrate to their audit clients that they are responding to their needs through (sustaining) technological transformation of the audit, which is producing a higher-quality audit beyond what was previously provided by the auditor and required by regulation. The increased quality is gained through higher-quality audit techniques, such as audit by exception, but is also increased through new data visualization technology to communicate audit findings to their clients and provide their clients with high-quality insights into both their financial reporting quality and their business.

Efficiency Innovations

So that's one benefit … is a more cost-effective audit, because we're going to be relying a lot more on machine hours and allowing our staff that are on the engagements to spend more of their hours analyzing and coming to conclusions, versus vouching, ticking and tying, transforming [the] client's data set to fit into our work papers, so you can start the analysis, which frankly would take up 60%, 70% of a lot of our junior staff's time.(INT24)

So, the goal would be that it [technology] replaces substantive evidence, right? Because that is how you are going to eventually get efficiency. The goal will be that we replace substantive procedures. A lot of what we see right now is value add. (INT6)

The replacement of these procedures is being implemented primarily using robotic processing automation (RPA) in the audit:20 “RPAs that can do the vouching for the associates … and you're gonna cut your time dramatically” (INT22).

I think a lot of what is being replaced is all the manual grunt work. All the stuff that a first year may be doing when they first come into the firm. Making lead sheets, reconciling this and that. I think that is all being very easily replaced. (INT5)

So, we come in via virtual private network. It is secure, get the tables. We know the data we need, and we, basically, can do that whole process in 45 minutes. From client GL [general ledger], automated calculation, published to a visualization software, in the auditor's hands in 45 minutes. (INT15)

Efficiency innovations do not enhance or change the existing audit product itself but are reducing the cost of the audit work through the reduction of staff hours.

Market-Creating (Disruptive) Innovations

So, someone could say, once the blockchain technology is up and running and is really, really good, why do I need a financial statement audit? Why do I need one? … [Our job] would be over the blockchain. The assurance over the blockchain itself, and that's where I think the future of the profession is ultimate digital assurance more so than financial statement assurance. (INT1)

When you look at something like blockchain as an example, does that become so powerful and so mainstream and accepted by regulators, that it essentially negates the need for, or dramatically changes, the way an audit must be conducted? (INT15)

Blockchain represents a risk that the traditional financial statement audit as a product may be replaced or disrupted and therefore may no longer be of value to the market.

In addition to the risk of market-creating (disruptive) innovations, one interviewee also pointed to an expansion of the audit product through technology in the form of different levels of assurance at different prices. This would allow companies who have greater trust issues or whose financial statement users want additional assurance to pay a premium for an audit whose assurance level is above that required by regulation or standards: “If you want the standard audit which is in adherence to the auditing standards, then you're going to pay Y, which is probably going to be less than X for that type of work” (INT20).

The tools that are being implemented within the audit allow for higher audit quality than required by standards and may enable the auditors to tailor their audit quality and their pricing to the specific needs of their clients.

Although the current technological innovations within the audit follow sustaining and efficiency innovations by focusing on improving the current product (quality of the audit) for the existing high end of the market and on improving efficiencies of the audit process, auditors are conscious that this may not be the only way forward. Market-creating (disruptive) innovations, although not imminent, are not impossible for them to foresee. Overall, the product dimensions analysis indicates that disruption is not happening as most findings point to either sustaining or efficiency innovations.

Profit Impact

Sustaining Innovations and Efficiency Innovations

The challenge that we have in that instance is they equate efficiency to cost savings, and we have to then educate on better quality, better value-added insights into your business, and frankly, the tools we're building, we don't build for free. (INT15)

Maybe in the last many years we've told our own people and our clients to think of the value we bring and measure that in terms of hours. And it's almost now going back and recalibrating that and saying, “You've never paid us a fair rate per our fee.” You've paid us for bringing you something. We're now bringing you that same thing and more, but our effort level may have shifted to technology tools, to service and development centers outside of your immediate visibility, and maybe a smaller team, but that's because the work is done differently elsewhere. Whether through service delivery or automation. (INT13)

These conversations parallel findings by Austin et al. (2021), who note that the implementation of data analytics has caused similar tensions with regard to fee discussions between auditors and clients. Our interviewees highlight that there are several advantages to the technology-enabled audit that strengthen their position in these fee discussions. The increased ability to demonstrate and illustrate audit work and insights through technology visualizations, the demonstrable increase in audit quality produced through audit by exception, and the insights gained through the technology-enabled audit all provide the auditor with greater negotiating power in these fee discussions.

Market-Creating (Disruptive) Innovations

We see no evidence of a decrease in the price of the audit for audit clients. According to Christensen's (1997) categorization, market-creating innovations capture the low end of the market, which was previously not served by the existing incumbents through the offering of a low-cost alternative. Consistent with historical practices in the audit industry, even if technological innovations lower the costs of the audit for the audit firm, they do not currently translate into lower audit fees for the audit client. Overall, we see no evidence of disruption from analysis of the profit impact of audit technology innovations.

Market Impact

Sustaining Innovations and Efficiency Innovations

One of the reasons we're pushing this so much is because we see the want for this in our clients. I think almost every proposal that we do now, we're putting in there what technology we have and what we have in the pipeline and how we use it to differentiate ourselves from the competition. (INT12)

As articulated by our interviewees, auditors are advertising their use of technology innovation within the audit during the request for proposal stage.

They're aware of certain technologies, and when they come speak to you, they're not talking to you about, “How does [firm] do the search for unrecorded liabilities?” They're asking you, … “What is [firm] doing in terms of automation right now?” (INT11)

I think the initial drive came from clients who, when they tender, they are asking firms to talk about their strategy for how they use technology in their audits, especially data analytics. (INT17)

We [audit committee] want something. If you articulate exactly what you want, they'd say, “I don't know, go figure it out with the company. We don't know, but we just heard that we should do this. We read the Globe [The Globe and Mail] yesterday and someone talked about it.” (INT7)

As audit firms adopt technological innovation for their existing, mainstream client base, this is consistent with Christensen's (1997) sustaining and efficiency innovations.

Market-Creating (Disruptive) Innovations

The historical financial statements have been our bread and butter, but we've got to leave that and look to the other kind of information we can provide assurance on. And we're just not moving fast enough, in my opinion. We are in a great position because we have the clients. We have access to the data. We have the confidence of the client to deal with them in terms of dealing with their information, confidentiality, services we can provide.

…

We're just not selling it. … I would say that something for example, assurance on MD&A, assurance on other KPI, like it's out there. The ability to do that today exists in the framework in the standards we've got. We just are reluctant to push that, and I think that will be our downfall.

…

Like additional assurance upon MD&A. Additional assurance upon some of the metrics that are in MD&A. If you read a client's MD&A, a customer's MD&A, I say that's just the fairy tale they've put together. Because until you can determine that those things and those quants and those numbers and the story they've come up with can be verified against something? It's just the words and the story they want to tell. (INT7)

Audit firms identified that the technology tools that are being implemented within the audit are also allowing for the possibility of expanding the audit and assurance market to new areas both for existing traditional audit clients and for new clients.

Prior disruption studies and theory indicate that disruption often comes from the lower tier of the market. Our interviewees are conscious of the possible threat of disruption, but they did not identify the non–Big 4 firms as the source. Our non–Big 4 firm interviewees were investing in technology, but not to the extent of the Big 4 firms. Most cited issues of a lack of sufficient investment money and lack of homogeneity and sophistication of their clients' accounting systems to make any significant moves on the audit technology front practical at this point. The smaller firms are starting to integrate increased technology on the audit through the purchasing of predeveloped software, some of which is sourced from a Big 4 firm, but they lagged the developments of the Big 4 firms. Although the non–Big 4 firms are certainly not standing idly by in the audit technology implementation game, we see no evidence of imminent disruption innovations stemming from them.

[Y]ou worry about disruption, like you really worry about it as a profession. (INT1)

Yeah, I think our threat today continues to be the Big 4. But I think the future is the unknown, and you don't know. (INT15)

Yes, Google. Absolutely. Google filed in the last six months, patents around audit, I believe. So, when you look at that … I've rolled them into what's out there that we don't know. Like, it could be Google, it could be. (INT15)

It could be Google or Microsoft. They have a lot of money to put into this stuff, and they've developed accounting software. They could pull so much data and analyze so many things so much faster than we could. The accounting firms, [firm] and the others, we were not originally technology firms. Now we're trying to adopt this technology to help enable the audit. We're saying we're going to a tech-enabled audit and going through digital transformation. There's a lot of things I think we're learning along the way and putting in the right kind of people because maybe your traditional accountant may not have the right skill set to lead some of this change. (INT18)

As articulated by this interviewee, although audit firms have the required financial and accounting skills and knowledge, they lag the technology companies in terms of technology and innovation skills. While the audit firms are catching up, the fear is that they may not catch up fast enough.

Instead of Googles of the world becoming the auditors, you're going to see underlying partnerships [with technology companies]. … Think about it. 'Cause that way, why not partner, and then speed up that process if that's inevitable anyway? (INT 23)

We were like, we're not gonna beat these guys, so let's partner up with them. So, our new [Big 4 A] auditing platform is called, we partner with [Tech A] on that. We partner with [Tech B] on the business process mining tool because we're not gonna beat 'em … but can take the best of what they do. (INT1)

One form of cooperation between technological and audit firms was identified by interviewee 23, who noted that the audit itself could be broken into parts where the auditing firms perform the final audit work, but a significant amount of the engagement is managed by another firm with technological skills and competencies: “It [the audit] could be pulled apart. The audit being pulled into different pieces and delivered by different firms … like source consulting.”

Now we are in the era of sensors. And sensors to me will be the cornerstone of pretty much everything when it comes to revenue cataloging. How do you … think about it, this new store is the Amazon. You walk in and you're paying because they know who you are by face recognition. So, your revenue recognition is based out of the camera and whatever algorithm there is behind it. From that regard, then, the reason that the Googles of the world and what not have not stepped in yet, because we don't have a whole lot. When that becomes the norm and data is pretty much the only thing needed in order to perform an audit, I do believe that they will step in. (INT23)

The other thing I worry about a little bit from a profession perspective is the biggest thing you have with your clients, or historically you ever had with your clients, is the relationships, right? You had the one-on-one relationships with your audit committees, with management, with those … if someone decides to build a better mousetrap, one of these start-up companies or MindBridge or someone figures out a real-time auditing before we do. Relationships, for 200 years of auditing, trumped everything. Technology's going to trump relationships at some point. (INT1)

Is there an upstart that comes in with something that attaches to SAP? You press a button, and you've essentially got a report that says you know, everything coming out of SAP is … complies with, is IFRS compliant or something like that. So, I think those … the risks around that are far greater than they've ever been. (INT15)

All interviewees recognized that there was a risk of market-creating (disruptive) innovations on the horizon, although most recognized that there are significant barriers which increase the uncertainty of disruption and allude to the fact that it is not on the immediate horizon. These concerns are merely speculative at this stage, and thus we conclude that the type of market impact indicated by audit technology innovations is not disruptive. Rather, both the demands from customers for more technology-enabled audits and the barriers to new entrants in the regulated audit space point toward audit technology innovations being sustaining innovations.

Follow-up Interviews and Analysis: An Update

We undertook additional data collection starting in November 2021 to gain our interviewees' perspectives on the key insights presented in our analysis and the potential changes that occurred since their initial interviews. The follow-up interview protocol is included in Appendix 2.

Of the original 27 interviewees, 23 were still with the same audit firm, 3 had left auditing, and 1 was no longer reachable.21 As a result, 26 of the 27 interviewees were sent a request for additional comments. Nine prior interviewees responded, with 6 interviewees consenting to be reinterviewed and 3 interviewees sending their comments by email.22,23 Our follow-up interviews were conducted in December 2021 through Zoom conferencing and were recorded and transcribed. A response rate of 35% for follow-up interviews is considered reasonable given the time lapse between interview stages. Although it is smaller, the follow-up sample is representative of our main sample and included partners from three of the four Big 4 firms and an audit technology leader from one of the Big 4 firms. Table 4 provides details on the follow-up interviews using the same interview numbers as the original interviews.

| Number | Date | Rank | Firm | Interview format | Length (minutes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 14, 2021 | Partner—Tech Role | Big 4 A | Male | Online | 31 |

| 6 | December 14, 2021 | Partner—Managing Partner | Big 4 A | Female | Online | 15 |

| 7A | December 13, 2021 | Partner—Tech Role | Big 4 A | Male | Online | 21 |

| 9 | December 13, 2021 | Partner | Big 4 B | Male | Online | 15 |

| 11 | December 14, 2021 | Manager | Big 4 A | Male | Online | 22 |

| 14 | December 13, 2021 | Partner | Big 4 D | Male | Online | 16 |

| Average interview length | 20 | |||||

- Notes: Due to a change in role, interviewee 7 from our original interviews referred us to their replacement for the follow-up interview. Interviewee 7A is in the same role within the same firm as our prior interviewee 7.

After the follow-up interviews were completed, we member-checked our findings (Malsch & Salterio, 2016) by providing our interviewees with a summary of our results and asked them to provide their comments and observations. No interviewee voiced any concerns with regard to our summary or identified the need to modify or alter the findings.24

Our follow-up interviews validated the original interview results. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has required adjustments in delivery of the audit, at this point, technology has not altered the forms of innovations happening in firms in the audit industry. Firms have continued to progress in their use of RPAs to automate existing audit procedures and reduce or eliminate manual audit tasks. However, new core products or entrants to the audit industry have not emerged: “The fundamental financial statement audit is still the bedrock, is still like the bulk of what, from a business perspective, is the bulk of what the profession is doing” (follow-up, INT13).

So, I wouldn't say we have seen anybody encroach in our market; that is a risk point for us, though, because, and this is the industry and I've said it for a while. That if we don't move and we don't move fast, there is very much an entry point for some of the larger tech firms to try and gobble up this market, right, so that's a real risk. (follow-up, INT7A)

More recently, the audit industry has been focused on developing technological skills and competencies and applying them to auditing, but also on moving beyond the static financial statement audit. The larger audit firms are taking advantage of the accelerated technological advancements, suggesting that market-creating (disruptive) innovations could be nearing for the audit industry. They have already recognized the need to upskill their technical expertise and embrace a more proactive approach to technological innovation as they become increasingly aware of the disruptive force that technological transformation will have on the audit industry. In line with the warning advanced by disruption theory (King & Baatartogtokh, 2015), the audit industry is attempting to forestall new entry by spearheading innovations and is keenly aware of threats by its competitors.

Summary of Findings

As identified on the thematic map, our interviewees indicate that technological innovation was being used to affect product dimensions and profitability as well as the market aspect of the audit. The final column of the thematic map indicates that technological innovations are primarily consistent with sustaining and efficiency innovations, as per disruption theory (Christensen, 1997). Nevertheless, the last column of the thematic map shows market changes in an aspect of the product dimension and also in the market of unregulated audits. While at the present time technology has been used to increase the quality and efficiency of the current mainstream regulated audit product, auditors are conscious that new technologies—for example, blockchain and population testing—have already started to make inroads in altering the audit product, and new market entry has already taken place in the unregulated fringes of the audit industry.

Our analysis suggests that the audit industry has thus far implemented technological innovations by focusing exclusively on their mainstream client base by implementing sustaining innovations with a focus on upselling quality innovations to mainstream customers. Consistent with a sustaining response, the audit industry was initially “pulled” by their technologically advanced clients to increase their technical skillset and invest in technology to match their own. Using technological innovations such as 100% population testing and data analytics, auditors are now able to raise audit quality to a higher level that exceeds regulatory standards. Interviewees stressed the value of also increasing the quality of communication and delivering additional insights through technology innovations such as data visualization, but these, too, are only important if the clients value them.

5 IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Our study makes several contributions that extend audit research to the industry level and present strategic implications of technological innovation for the audit product, the profitability of the audit, and the audit market. First, our analysis indicates that technological innovation will continue to expand and alter the audit product to the extent that static financial statements will be supplemented with real-time reporting, consistent with the conclusion of Austin et al. (2021), who specifically focused on auditors' adoption of data analysis tools. In addition, with continued technological innovation, including the adoption of other technologies such as blockchain, the usefulness of the static financial statement audit will erode. Going forward, increasing dependence on technology is at first likely to supplement the exclusive reliance on static financial information as users will augment their reliance on it with real-time sources of financial information (Cong et al., 2018); however, the evolution to the replacement and primary reliance on real-time reporting is imminent. Of note, this evolution to the provision of audit services for real-time financial information will require technological enhancement and upskilling for auditors and audit processes (Denning, 2016; Knechel, 2021). Future research is needed to determine what is required to compete in these new audit arenas and respond to client needs.

Second, technological innovation has resulted in lower costs. The audit industry has used cost efficiencies associated with the application of technology to reduce labor and variable costs, which at the present time are not being passed to audit clients. Instead, audit firms have justified the maintenance of higher audit fees by pointing to the significant capital required to invest in technology and the true value of a quality audit to clients. While the use of technology undermines the audit industry's reliance on the traditional audit fee model, decoupling audit fees from audit hours highlights the need to develop a new fee model to effectively justify audit costs to the client.

Disruption theory (Christensen, 1997) suggests that these efficiency savings should be passed on to the customer through lower pricing to reduce the risk of entry from a low-cost provider; as the market for audit—in nonregulated markets—continues to expand, other suppliers are acquiring skill sets that in the longer term may usurp the monopoly produced by regulation in the face of continued technological innovation. The presence of profit levels protected by regulatory barriers invites new entry when regulatory barriers fall. This was recognized by our interviewees who suggested that regulatory barriers are allowing the auditors to gain skills and knowledge that may allow for their own expansion of the market and potential future self-disruption.

Third, while technological innovation has resulted in labor and cost savings, regulation allows the audit industry to maintain current price levels by preventing entry of new products or new competitors through regulatory requirements for quality demanded by the profession, the securities market, and/or securities regulators (Malsch & Gendron, 2013). New market entry has already occurred in the audit industry in those areas not covered by regulation. Regulatory barriers to entry caused by current standards may presently isolate the audit of financial statements from new entrants; however, this barrier may not protect the industry forever. While it is difficult at the present time for new market entrants to enter the regulated audit industry, regulatory requirements have thus far provided an effective barrier to delay speedy entry and give incumbent firms time to position themselves before new entrants can gain a foothold.

While regulation acts as a barrier to new market entrants, it does not fully eliminate the possibility of one appearing and disrupting the status quo. New entrants may emerge from within the audit industry itself as large firms focus on customers who are amenable to technology-enabled audits. Small audit firms with experience dealing with small, unsophisticated clients can continue to gobble up those businesses whose data are not amenable to a technology-enabled audit, and may increase their market share accordingly. They may also pivot and upskill their auditors to compete for technology-enabled audits as such audits have fewer barriers to competition. For example, technology empowers remote work, and audit firms no longer necessarily need offices or staff in a particular part of the world to perform audits there. New entrants from outside the audit industry may also make their presence felt. For example, large technology firms who already specialize in data analysis, such as Google, may partner with smaller firms or even regulators to better serve the regulated market through real-time financial reporting. Longstanding relationships between incumbent firms and companies, which have traditionally been key to client retention, may erode as new, more technological, innovations make their way into the market.

Firms are currently upskilling in technology and are hoping to leverage these new skills to expand the market for assurance services beyond the regulated financial statement audit. Some interviewees recognized that the current reliance on regulation cannot permanently deter a disruptive response, but rather gives the industry the luxury of time to acquire the necessary competencies to spearhead market-creating (disruptive) innovation by industry incumbents, and they hoped this will result in longer-term self-disruption, which may promote the survival of the audit industry in the longer term.

Although regulation may delay or alter new market entry associated with technological innovation at the present time for the audit, the audit industry, like the legal industry, may be running out of time to anticipate and prepare for new products and new markets that can and will emerge when regulation and regulators are no longer present or somehow alter the barriers to technological innovation (Cong et al., 2018; King & Baatartogtokh, 2015; Munoko et al., 2020). When disruptive technological innovation occurs, regulators will be pressed to provide regulatory guidance, as Munoko et al. (2020) identify that auditors' use of technology alters professional skepticism and mindset. Additional research is needed to explore which means can be taken to ensure audit quality with technological innovation. Finally, with a future lowering of regulatory barriers, non-auditor entry may occur directly and/or through partnerships with audit firms. Future research is needed to explore the implications of “non-auditor” entry as well as to explore the required technology skills needed in a differentiated audit market.