Impacts of COVID-19 on Women and/or Caregivers in Accounting Academia at Canadian Postsecondary Institutions and Suggestions Moving Forward: A Commentary*

Accepted by Leslie Berger. I am very grateful to Leslie Berger and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. In addition, I appreciate the detailed feedback from Merridee Bujaki, Sandra Scott, Candice Waddell-Henowitch, and Ravikiran Dwivedula. A special thank-you to my research assistant, Steffany Peters, for her excellent work. I gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the CAAA–Deloitte Fund for Accounting Research. Lastly, I would like to thank the contributors for their willingness to write a submission and answer follow-up questions.

ABSTRACT

enThis commentary provides insights on the issues faced by women and/or caregivers in accounting academia at Canadian postsecondary institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal reflections from 23 contributors across Canada were compiled and analyzed using thematic content analysis. Results show that COVID-19 has adversely impacted research, teaching, and other areas of work and life for this demographic. Research stopped or slowed, lower productivity was experienced, concerns over academic integrity increased, interactions with students decreased, academics left the profession, mental health was adversely impacted, and academics lost dedicated work time. In addition, the contributors provide suggestions to address these issues moving forward to help equity-seeking groups. Suggestions include support from postsecondary institutions at all levels, additional funding, adjustments to tenure and promotion criteria, and the option for a reduced workload.

RÉSUMÉ

frImpacts de la COVID-19 sur les femmes et les aidants naturels parmi les professeur(e)s de comptabilité dans les établissements d'enseignement postsecondaire canadiens et suggestions pour la suite des choses : Commentaire

Le présent commentaire fournit des observations sur les enjeux auxquels font face les femmes et les aidants naturels parmi les membres du corps professoral en comptabilité dans les établissements d'enseignement postsecondaire canadiens durant la pandémie de COVID-19. Les réflexions personnelles de 23 contributeurs du Canada ont été compilées et analysées dans le cadre d'une analyse de contenu thématique. Les résultats indiquent que la COVID-19 a eu un effet négatif sur la recherche, l'enseignement et d'autres aspects du travail et de la vie de ce groupe démographique. La recherche a été interrompue ou ralentie, la productivité a décru, les préoccupations relatives à l'intégrité universitaire ont augmenté, les interactions avec les étudiants ont diminué, des membres du corps professoral ont quitté la profession, la santé mentale de certains a été négativement affectée et d'autres ont perdu du temps de travail dédié. En outre, les contributeurs formulent des suggestions pour s'attaquer à ces enjeux à l'avenir afin d'aider les groupes en quête d'équité. Parmi leurs recommandations, mentionnons la prestation de soutien par les établissements d'enseignement postsecondaires à tous les niveaux, du financement additionnel, des modifications aux critères de titularisation et de promotion ainsi que la possibilité d'avoir une charge de travail réduite.

1 INTRODUCTION

Canadian academics across the country have been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the virus that causes COVID-19 to be the cause of a worldwide pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020), Parliament agreed to shut its doors (Bronskill 2020), Canada restricted entry into the country (Government of Canada 2020a), and most postsecondary institutions moved to remote learning (Doreleyers and Knighton 2020). When most institutions had only a few weeks left in their winter 2020 semesters, educators were forced to change plans, modify assessments, and make do with the technology available to them to finish out the term. When the initial lockdowns were implemented in March 2020 and most postsecondary institutions immediately closed, many assumed that life would be back to “normal” in the fall of that same year. This is not the case. Years are passing, and well into the winter 2022 postsecondary term, Canadians are still being affected by the pandemic.

Unlike countries such as China, which used a restrictive, mandated approach, and Sweden, which employed suggestions to its residents and less stringent policies (Yan et al. 2020), Canada's approach has been more moderate and measured. “Canadians have been asked to avoid social contact since mid-March 2020.…The objective was to slow down the number of infected people to give medical infrastructures time to admit new patients in need without running out of space and equipment” (Urrutia et al. 2021).

Women and caregivers have seen significant increases in their workloads as they attempt to balance the commitments of academia with the role of providing care to children, parents, and other family members (Collins et al. 2020). These increased care responsibilities have often resulted in reduced work time available for academic activities and are adversely impacting the advancement of women and caregivers' careers (Collins et al. 2020). Even before the pandemic, studies found that women and caregivers are impacted by care responsibilities to a greater extent than other academics (Derrick et al. 2019). This is due to the need to perform academic duties and additional caregiving duties simultaneously. Crook (2020) explains that despite a commitment to teaching and research, an overriding responsibility to maintain and develop the human life of one's children remains. This is explored further through findings that mothers have significantly reduced work time compared to fathers in families with young children (Collins et al. 2020). With the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns arise as to the additional impact on women and caregivers.

Postsecondary educators across Canada identified many similarities when faced with a global pandemic. Altogether, women and caregivers have been adversely impacted by the pandemic in their research, teaching, and overall work. When research slows or is stopped, future employment prospects are weakened. Related to teaching, academics cite lower productivity despite additional time spent, increased academic integrity issues, and less interaction with students. Mental health and loss of dedicated work time are also adversely impacting academics. The result is a decline of academics within the profession as academics leave, or consider leaving, their institutions. Before the pandemic, the declining numbers in the academic accounting profession had recently turned around (Oler et al. 2021). However, this commentary suggests that a decline in accounting faculty may return if issues are not addressed.

A commentary is a work that seeks to offer timely insights into issues that are of interest and importance to a broad audience. I offer a commentary on these challenging times, documenting issues identified by accounting academics who identify as women and/or caregivers, and how these individuals are impacted in both the short term and long term. This same group of individuals provides suggestions for addressing the issues created by COVID-19. My research objective is to understand how women and/or caregivers working in accounting at Canadian postsecondary institutions have specifically been impacted in their research, teaching, and other areas as well as to identify suggestions to remedy these implications. Individuals' comments are supplemented with support from professional literature to provide additional insight into how COVID-19 has impacted these equity-seeking groups.

This commentary accomplishes more than just bringing awareness to the issues faced by Canadian women and caregivers in accounting academia. It highlights suggestions made by this same demographic as to how the issues identified can be addressed going forward. This is particularly important in working toward equity for all in the workplace in the wake of the pandemic. In Canada, male academics outnumber female academics approximately 2:1 (Council of Canadian Academies 2012). Before the pandemic, significant progress was being made related to representation of women in the postsecondary ranks (Council of Canadian Academies 2012). However, the pandemic is having a significant impact on women and caregivers, as evidenced by the contributors' individual submissions. The impacts of COVID-19 are expected to extend well into the future and need to be identified before they can begin to be addressed.

The article by Sangster et al. (2020, 432) is the “first global survey of accounting faculty on the theme of crisis management in accounting education and on the specific effects of COVID-19.” This commentary is one of the first to synthesize the issues, and suggestions for addressing these issues, specific to Canadian accounting academics—with the goal being increased awareness of issues impacting women and/or caregivers during the pandemic. As the pandemic was unforeseen by most, little study has been done to date in the specific area of how accounting academics are impacted in their roles by COVID-19. This is an emerging topic, and although much more research will be required, it is imperative that it be studied in a timely manner. Issues need to be diagnosed before solutions can be found. Eagly and Carli (2007, 63) state, “If one has misdiagnosed a problem, then one is unlikely to prescribe an effective cure.”

The remainder of this commentary is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the background literature on this topic. Section 3 describes the methodology used in undertaking the work. Section 4 presents common issues identified by contributors related to research, teaching, and other areas, and section 5 includes suggestions identified that would assist in addressing the issues. Section 6 presents concluding remarks.

2 BACKGROUND LITERATURE

For decades, women have been working to achieve gender parity, and at the pre-pandemic rate of change, they were still many years away from achieving this goal. Before the pandemic, the majority of unpaid housework still fell to women (Fletcher 2017). COVID-19 has only magnified this issue. Several studies find that, with home-based work, “Women, in contrast to men, tend to reallocate the additional time ‘saved’ from not having to commute to additional caregiving or housework rather than to leisure” (Kurowska 2018, 404). Oleschuk (2020, 503) notes, “Rising care demands created by COVID-19—specifically those brought on by remote working, a lack of childcare, and the virus'[s] particular risk to aging populations—are disproportionately incurred by women and impede their ability to work.” Thus, home-based work may not be an optimal way to create a work-life balance for women and caregivers. However, home-based work was one of the consequences of the pandemic for most accounting academics.

According to Oleschuk (2020, 502), “Long-standing inequalities in both paid and domestic work appear to be exaggerated during the present pandemic circumstances in ways that disproportionately hinder the productivity of academic women.” A pre-pandemic study specific to academics conducted by Russell and Weigold (2020) finds that, in terms of work stress, women show higher levels than their male counterparts in terms of qualitative role overload, quantitative role overload, and role development. Women specifically commented on the “perceptions of pressures for women to take on additional tasks, many of which were consistent with stereotypically feminine roles” (Russell and Weigold 2020, 135). Stress and anxiety have been amplified for many women and caregivers during the pandemic.

A review of the literature shows extensive study on the pandemic and the topic of COVID-19. This has been the focus of many journals and articles; however, most articles are focusing on how COVID-19 is impacting teaching (Morgan and Chen 2021; Osborne and Hogarth 2021; Othman 2021; White 2021; Wong and Zhang 2021) and performance measurement systems at both a government and organizational level (Mitchell et al. 2021; Ahn and Wickramasinghe 2021; Delfino and van der Kolk 2021; Passetti et al. 2021). There is no doubt that females and caregivers face additional difficulties due to the pandemic. Disadvantaged groups have been disproportionately impacted by this crisis both socially and economically (Leoni et al. 2021). One of the reasons women and caregivers are disproportionately impacted is that measures used to divide tasks and workload fail to capture the emotional work involved in times of crisis (Perray-Redslob and Younes 2022). However, it has not yet been determined how Canadian accounting academics who fall into one or both categories of women and caregivers are being specifically impacted.

3 METHODOLOGY

Recruitment

An initial list of potential contacts was created from my experience working with Chartered Professional Accountants (CPA) organizations across Canada. Contributors were sought out via email and asked if they fit the profile and would be willing to write a submission. In addition, individuals who were emailed were asked if they knew others fitting the profile who would be interested in the project.1 Subsequently, the Canadian Academic Accounting Association (CAAA) emailed its members, asking for participation.

In the initial stages of this research, the decision was made to include names and institutions in submissions. However, after clear direction from numerous potential contributors, this decision was reversed. Anonymous submissions were the only way that contributors felt comfortable identifying specific issues and sources of stress without worrying about stigma and career-related concerns.

It is telling that of the 107 individuals I personally emailed, 54 did not respond at all, even after a second follow-up email. This may speak to the overwhelming burden individuals feel in terms of workload, particularly in managing and responding to emails. Participants who replied and declined the invitation to participate provided numerous comments. One contact replied that although this was an interesting project, their province had moved into “lockdown” and their kids were now at home. The contact felt overloaded with work and stated they would take an unpaid leave if that was an option. Another contact replied that they did not have time to write 1,000 words for a study and that this, in itself, was evidence of how they had been impacted. A third contact who had initially agreed to participate had to withdraw their participation due to health reasons. These comments speak to the negative impact the pandemic has had on research and teaching agendas.

Data Collection

- What specific changes have occurred in your life in the last year due to the pandemic that impact your teaching and research agendas?

- What are the short-term (6–18 months) and projected long-term (18 months to 5 years) implications of these changes?

- What would help you address the impact of COVID-19 in the areas described?

Table 1 presents an extract of the email sent to potential contributors for their reflections on COVID-19. No other guidance was given to contributors, in order to reduce the possibility for my personal experience to bias contributors' responses. A narrow window of time was provided for responses in an attempt to capture the impacts of the pandemic and suggestions for help at a specific point in time. Since the collection of data, some suggestions, such as availability of full vaccination, have occurred.

Participants are asked to write a 750- to 1,000-word submission addressing the following questions by May 7, 2021. The anonymous submission will be included in the published research study.

|

Two asks of you:

|

The compilations of personal reflections from 23 different accounting academics on the impact of COVID-19, and suggestions to address that impact, were the basis for this commentary. These contributions give Canadian accounting educators the ability to have their voices heard. In addition, it provides a space to express the challenges faced, the implications of these challenges, and suggestions for how they can be overcome.

Table 2 summarizes demographic data about the contributors. Women account for 87% of the participants. The majority of contributors hold the position of assistant professor (43%), followed by instructor or lecturer (39%). This coincides with the fact that 11 participants are early in their career (which is defined by the first five years in their role), 9 participants are in the middle of their careers, and the remaining 3 individuals are within two years of retirement. Nineteen of the contributors hold a CPA designation. Contributors are based in cities that range in size from less than 100,000 people to more than 1,000,000. Using data from 2021, it was found that over half of the participants (69%) teach at postsecondary institutions located in cities of under 500,000 people.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 20 | 87 |

| Male | 3 | 13 |

| Title | ||

| Assistant professor | 10 | 43 |

| Associate professor | 4 | 17 |

| Instructor/lecturer | 9 | 39 |

| Chair | 2 | 9 |

| Population where school is located (per 2021 data) | ||

| <99,999 | 7 | 30 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 9 | 39 |

| 500,000–999,999 | 3 | 13 |

| 1,000,000+ | 4 | 17 |

| Stage of career | ||

| Early (0–5 years experience) | 11 | 48 |

| Mid | 9 | 39 |

| Late (<2 years to retirement) | 3 | 13 |

| CPA designation | ||

| Yes | 19 | 83 |

| No | 4 | 17 |

| Caregiver of | ||

| Younger than school-age children | 3 | 13 |

| School-age children | 10 | 43 |

| Elders/dependent spouse or adult children | 4 | 17 |

Of the 23 contributors, many are providing care, with 10 contributors having school-age children, 3 having children younger than school age, and 3 having parents, disabled spouses, or adult children for whom they provide care.

Analysis

Contributions received from academics varied in size from 400 to 2,500 words. Contributions were read, edited, and then returned to contributors for approval of any changes made. Content analysis was used to identify themes related to the issues identified in the contributions and the suggestions put forth as to how academics could be helped. Content analysis is a technique that generates data by analyzing the content and message of written text (Hair et al. 2007). This research technique is used to make replicable inferences and allows qualitative data to be converted to quantitative data.

The data analysis began by having the researcher and research assistant read the first five contributions in their entirety. Then, submissions were carefully reread, highlighting text that identified an issue or suggestion. From these highlighted passages, keywords or phrases were developed. After open coding of the first five contributions, the remaining submissions were coded. New keywords or phrases were added on an as-needed basis, and when a new keyword or phrase was added, the previous contributions were reread and coded appropriately. When all transcripts had been read and coded, the researcher and research assistant examined all data that were labeled with a keyword or phrase. Some keywords or phrases were combined, and others were split into subcategories. Any differences between the researcher's and research assistant's classifications were discussed until a consensus was reached.

In addition to analysis of the contributions for similar issues and suggestions, the overall tone was also examined. Tone was assessed through multiple methods. One method included determining the number of words written on issues and suggestions about which the contributor felt positive, negative, or neutral. Another method used was looking for keywords or phrases that were definitive in their tone. Examples of keywords or phrases that were positive include “fortunate,” “grow as an educator,” and “hit the pandemic jackpot.” Keywords or phrases that were negative in nature include “nightmare,” “guilt,” and “sent me to the hospital.” Contributions were assessed as being neutral in tone if they had balanced word counts on positive and negative issues and included both positive and negative words or phrases.

Contributors were randomly assigned a contributor number (e.g., Contributor 1). These identifiers are used in reference to any quotations taken from the academic contributions. The individual contributions are presented in the supplementary Appendix.2

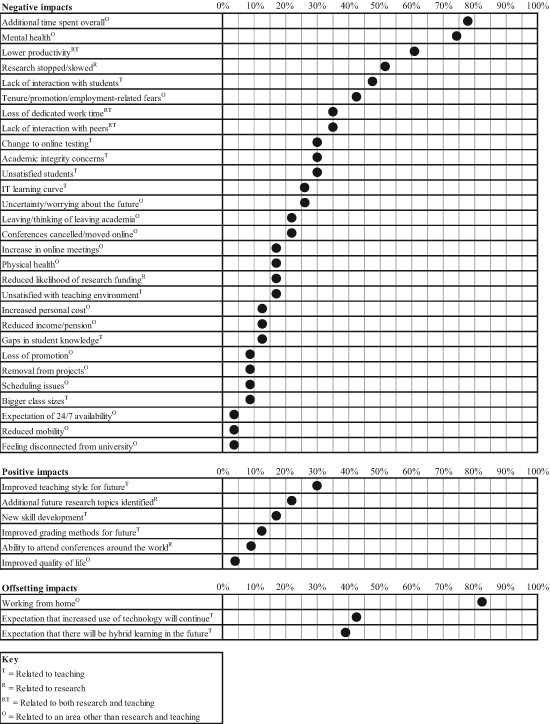

4 ISSUES IDENTIFIED

As a result of the increased workload noted by most participants and the 750- to 1,000-word limit, individual submissions highlighted only the issues and suggestions about which the contributor felt most strongly. Although some themes were only mentioned once, it is possible they are represented by a greater number of individuals, but due to the word limit, participants were unable to discuss them. Six issues were identified as having a positive impact on contributors and are shown in Table 3. These relate to improvements in teaching which will be utilized to a greater extent in the future, such as the flipped classroom approach, improved grading methods going forward, and new skill development. In addition, contributors identified the areas of additional research and the ability to attend conferences around the world remotely as positive outcomes of the pandemic. Moving forward, Contributor 20 sees “a strong research agenda” as “there have been so many events that have happened that will open up doors to new research ideas and rich data sets.” In addition, Contributor 23 noted, “The pandemic has actually allowed many more people and information to be available, even from further away. It is breaking down geographic barriers.”

|

There were three issues identified that are neither clearly positive nor negative in nature, as shown in Table 3. Almost all the contributors (19 of 23) noted the change to working from home since the onset of the pandemic and described both pros and cons related to this change. Benefits to working from home include the ability to multitask and the elimination of distractions from colleagues. One contributor appreciated working from home, noting, “Otherwise, I sit in a small cubicle space throughout the day subjected to colleagues nearby hosting Zoom classes and recording lectures. The office environment makes it tougher to concentrate and get anything accomplished” (Contributor 2). Other contributors disliked the change to working from home, with loss of dedicated work time due to childcare requirements being the most common reason cited. Even benefits of working from home, such as the elimination of the commute, have a downside. Contributor 8 stated that “no commute meant there was no time to transition from work to parent, but I did gain an hour each day for other use.”

Another issue most contributors noted is the change to teaching classes either synchronously, asynchronously, or a mix of both. Many contributors (10 of 23) expect there to be increased use of technology in the future, and 9 of the 23 participants expect to see hybrid learning in the future. These changes are described with mixed responses. Contributor 10 stated, “The transition to online classes is a time-intensive process, an investment that will likely not be recouped.” In contrast to this, Contributor 23 noted that they plan to offer a Zoom link going forward as “offering multiple delivery methods creates many benefits, including improved design for accessibility tools, such as closed captioning, environmental benefits through reduced commutes, and reinforced technology skills in the classroom.”

Table 3 lists all issues identified by contributors; overall, the majority of issues (29 of 38) identified are negative in nature. Contributors' most common insights are discussed as they relate to research, teaching, and other areas of academia. Research issues include the stopping or slowing of research. Teaching issues include lower productivity despite additional time spent, academic integrity concerns, lack of interaction with students, and use of the flipped classroom approach. The flipped classroom approach is the only issue discussed further that has positive implications. The other issues discussed are comprised of mental health, leaving academia, and loss of dedicated work time. Table 3 lists the issues identified that have adversely impacted contributors.

Research Issues: Research Stopped or Slowed

In the summer of 2020, accounting academics were extremely focused on the teaching and learning challenges experienced in the first few months of the pandemic, and they felt that research projects could be put aside for the short term with little consequence (Sangster et al. 2020). A year later, Canadian academics are more concerned with the negative impact of stopped or slowed research on their career advancement and job security. The stopping or slowing of research was one of the top issues identified by contributors. Contributors (12 of 23) discussed this issue in their submissions, with multiple contributors noting the standard 40-40-20 split between teaching, research, and service at their institutions being hard, if not impossible, to achieve during this time. As Contributor 15 expressed, “Conference papers were not finished, journal articles were not written, and grant applications were put on hold.”

Sentiments relating to research being a high-cognitive level task, and significant breaks in research being impactful, are echoed throughout the submissions. “The momentum I was building pre-pandemic on the tenure track will take a lot of effort to rebuild” (Contributor 7); “I am concerned that my research pipeline has suffered during the pandemic” (Contributor 12); and “I find myself struggling to get into research gear” (Contributor 15). Contributor 10 stated, “I was not able to apply for grants. This means that I do not have any current research in my pipeline and have had to triage what is remaining and summon the energy to get this going again.” This coincides with the decline of female authors on published papers which occurred at the start of the pandemic in some fields (Langin 2021). This decline in published work is directly impacted by the 33% larger drop in research hours that mothers suffered, in comparison to fathers, around the world (Langin 2021). Journals are noting fewer submissions from women, but not from men (Crook 2020). Although this is the case in the population at large, individual families have negotiated different arrangements, and some fathers working in academia have taken on the childcare work (Crook 2020).

In addition to the challenge of getting into research gear, the pandemic has impacted how research can be successfully conducted. Contributor 4 discussed the issue of low response rates when conducting experiments online as opposed to in person. The contributor was required to rerun the study and resubmit the results, but due to the pandemic forcing participation to occur online, the low response rate means that “this research study is likely to not be published at all before I retire.”

Part of the impact on research was due to conferences being canceled or moved online, limiting the dissemination of the work. In addition, the cancellation or moving of conferences online hindered opportunities to meet potential research collaborators: “Personally, research was difficult for several reasons. It was harder to reach out to colleagues for research discussions and to bounce ideas off them. The university was under significant financial constraints which meant that money for research was not available” (Contributor 20). Many of the benefits of attending conferences, such as networking and rapport building, cannot be replicated in a Zoom breakout room. Eight contributors mentioned the issue of being unable to interact with their peers, with some of this lost interaction resulting from conferences being canceled or moved online. For example, “I could not meet my co-authors in-person, which is something I find to be productive and inspiring” (Contributor 22).

Eight contributors who discussed the stopping or slowing of their research also identified tenure, promotion, or employment-related concerns. Within the 23 contributions, there is representation from individuals in the first few years of their careers all the way to those in the final stages of their time in academia. The majority of those who identified employment-related concerns are in the early stages of their academic careers. However, it should be noted that one accounting academic in the late stage of their career also recognized this as an issue: “Certainly, my younger colleagues need a lot of extra time on their tenure clocks. Their time to promotion is also likely to be affected, which can have a substantial impact on lifetime earnings” (Contributor 4).

Teaching Issues

Lower Productivity Despite Additional Time Spent

Besides working from home, additional time spent on work-related functions was the most common issue identified. Nearly all the additional time was focused on teaching-related activities. Fourteen of the 23 contributors identified lower productivity as an issue, and 18 contributors identified additional time devoted to work. Both issues had adverse effects on contributors. Note that lower productivity related to research was identified as a separate theme and is discussed under that heading above. Comments such as “since summer 2020, I have significantly reduced the number of projects I am involved with and resigned from one project” (Contributor 10) and “in the short term, course materials could not be updated for the current semester” (Contributor 21) indicate the lower productivity experienced by a significant portion of academics. Contributor 10 stated, “Currently, I am feeling some elements of burnout and am not enthused to get going and plan for the 2021–2022 academic year. This means that my courses for the upcoming year will not likely be refreshed and updated the way I would typically do from year to year.” Contributor 10 also noted, “I said no to a lot more items than I would typically decline in a given year, including textbook opportunities, collaborations, and professional development.” Unlike many other disciplines where reduced productivity is focused almost exclusively on the decrease in published papers, lower productivity in accounting also encompasses the decrease in educational leadership, service to CPA organizations, and reduced involvement in CPA's various programs and courses.

Of the 14 individuals citing lower productivity, all but one person expressly stated spending additional time on academic pursuits. These pursuits are almost all teaching-related, such as modifying courses for online delivery, filming videos for asynchronous classes, converting testing assessments for online platforms, and preparing materials for multiple methods of delivery within the same class. This is all in addition to the increased time spent on caregiving and domestic duties.

Despite working more hours, contributors still assessed their productivity during the pandemic as lower than before the pandemic. Contributor 17 said, “I began to work late into the night, or wake up extra early, in an attempt to get tasks done. Perhaps this does not sound like much, as of course, we have all worked long hours before. However, what made this different was that the long nights were not to get ahead or get some extra work done, but rather it was completely out of necessity, and still felt like not enough.”

Ten of the 23 contributors have school-age children who were sent home from school at various points since March 2020 for varying amounts of time due to provincial regulations and shutdowns. Of these 10 contributors, 3 made the decision to homeschool their children during the pandemic. In addition, 7 contributors care for family members with health-related concerns or children too young to attend school. The time associated with providing this additional care to minor children, elderly parents, and extended family was spent on top of the regular hours that would normally be devoted to work. This care work should be noted since the hours are extensive in number and have a great impact on the contributor.

Contributors also identified some changes brought on by the pandemic that resulted in saving time. Time-saving factors identified include Moodle's option to automatically mark tests and exams; no commute to work; no before and after time required for video meetings; outfits are less complex; not having to find keys; not having to find parking; and received teaching assistant help to offset work. These time-saving factors helped offset a small portion of the increased time spent overall.

Academic Integrity Concerns

Academic integrity issues negatively impacted contributors by requiring additional time to prevent academic dishonesty, detect potential opportunities for cheating to occur, and address the increased issues that arose. Seven of 23 contributors mentioned both online testing issues and academic integrity concerns. Research shows that students and faculty alike perceive that cheating is easier in an online learning environment (Kennedy et al. 2000). This is due to the ability to collaborate with other students, use of the Internet to look up answers, and access to websites where actual answers are provided to the specific questions asked. With the onset of the pandemic and most postsecondary campuses moving to online learning environments, the occurrence of cheating increased. This shift to online learning happened with no time to integrate rules and behaviors for ethical conduct suitable for an online environment or to develop specific techniques to prevent cheating. Without integrating the rules, behaviors, and specific techniques required, inappropriate behavior will increase (Marshall and Varnon 2017). Increased academic integrity issues coincide with the spike in results when Googling “assignment help” and “online exam help” after the onset of the pandemic (Hill et al. 2021). One of the more popular filing sharing sites, Chegg, found the number of student requests increased by almost 200% when comparing 2019 to 2020 (Lancaster and Cotarlan 2021).

Although postsecondary institutions have various proctoring software options available to them, contributors discussing this topic agreed there was no widespread acceptance of such software by their institutions. Contributor 2 states, “I did look into proctoring software, but my administration was doing everything in their power to not let it happen.…Administration basically said that requiring students to have their cameras on would be an invasion of their privacy.” According to Contributor 4, “Our VP Admin promised students that they would not be prohibited from going backwards on exams, which is an effective anti-cheating device,” and Contributor 22 stated, “Our university published a statement that the lockdown browser software for exams could potentially cause human rights issues and lead to student discrimination.” Lastly, proctoring software is most effective when students have the appropriate technology, but contributors noted that students sometimes lacked the webcams or appropriate lighting necessary for the software to function effectively.

Since the onset of the pandemic, results have shown that students dislike online exams. In addition, a lack of mutual trust during online exams exists between the students and the professors (Amzalag et al. 2021). Cheating is of particular concern for accounting academics as accounting students often plan on furthering their education by completing the CPA professional program and obtaining a CPA designation. Accounting academics know that integrity and professional conduct are cornerstones of the profession, and concerns regarding integrity of assessment are evident in the submissions. Contributors called academic integrity “the biggest topic related to changes in education” (Contributor 2) and “the most pressing issue” (Contributor 2). In addition, “The move to online teaching has created significant challenges in assessing student learning outcomes, and this is something that I think needs to be addressed by the academy” (Contributor 13).

Contributors were concerned and frustrated with academic integrity issues: “Many of my colleagues simply gave up worrying about academic integrity” (Contributor 2). Contributor 4 stated, “Advanced attempts to discourage cheating have resulted in failure of our learning management systems and our dean's office criticized us for it.” According to Contributor 13, “My experience with online tests leads me to believe that students are able to access resources even when writing the exam.”

Despite concerns with academic integrity, one contributor has conducted research on the topic of proctored versus unproctored exams. The results of this research led them to believe that proctoring is not essential if an applied exam is prepared. These findings were also supported when put into practice in that contributor's own classes. Contributor 13 echoed this statement: “I changed the style of exams I gave this term to essentially a take-home assignment that included mostly mini cases where different answers were expected from students. … In the end, I was satisfied that any cheating that had occurred was caught.” However, changing to applied exams or mini cases does have drawbacks, such as the significant amount of time required to create and mark these assessments. In addition, these alternative assessments are not possible in all courses due to the nature of the material being taught.

Lack of Interaction with Students

From the insights of these contributors, one can observe that moving to a remote learning3 environment has both opportunities and challenges (Adedoyin and Soykan 2020). In a remote learning environment, such as that utilized by most postsecondary institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic, instructors have minimal to no contact with students. This was stated by 11 of 23 contributors as a negative issue. Decreased social interaction and communication with other students, as well as decreased interaction with faculty and other university staff, was one of the most frequently voiced negative effects from students about remote learning environments (Hoss et al. 2021). As Contributor 1 stated, “Communicating virtually requires deliberateness,” and thus many instructors noted a lack of questions from students during and outside of class time with a decrease in visits during online office hours or open sessions. In addition, contributors found it difficult and ineffective to call upon students to answer questions or join in a discussion in a virtual environment: “I have had less access to my students, as students have felt less motivated to engage, and calling them out is not always supportive in this environment. In a classroom setting, it was possible to see from their body language whether they were ready to take a question or not” (Contributor 22).

Without the ability to interact in person with students, contributors found that they had less informal feedback from students about their learning. When students did ask questions via email, numerous email exchanges were needed to resolve issues that would have only taken a few minutes if asked in person. Interaction with students is a positive aspect of the teaching environment which was eroded by the pandemic and the sudden shift to online learning.

Although the lack of interaction with professors was not the sole reason, it was one of the reasons why students were unsatisfied with their learning experience. Contributor 16 stated that “students struggled and were frustrated. Not everyone is built for online learning.” Three contributors identified that the pandemic has created gaps in student knowledge, which will need to be addressed going forward. These gaps were identified as an issue for new students as well as graduating students. Contributor 20, teaching first-year students, stated, “These students are mostly coming from high school where they have had disrupted and condensed schedules, and most likely gaps in learning.” According to Contributor 16, “Students who are at the third- and fourth-year level, particularly those that are about to graduate, may end up missing the specialized and in-depth knowledge needed either for higher levels of education or for their desired roles in the labour market.” Lastly, as Contributor 18 noted, “Although we managed to teach the learning outcome, I question whether the students retained what we hoped they would.” These comments echo a frequently voiced concern from students related to the quality of teaching and learning deteriorating in an online learning environment (Hoss et al. 2021).

Flipped Classroom Improves Teaching Style

The remote learning environment was new to most contributors, as only 5 of 23 contributors acknowledged having previous online teaching experience. As a result, academics adopted new teaching methods to engage students and ensure content would be learned and retained as well as possible. This was identified as one of the most common areas where additional time was spent in the year.

In contrast to the adverse impacts other teaching-related issues had on academics, the flipped classroom approach was identified as a positive change. In adopting new teaching methods and techniques, the flipped classroom approach benefits students by having them learn the material on their own and then apply the material during class time by working through problems together: “By working through the numbers themselves, students will be engaged and able to better identify any areas they do not understand” (Contributor 1). Contributor 2 stated that “our face-to-face classes are more productive in that students are not just passively writing down my work but are actually engaged in the discussion and trying things on their own.” Even before the pandemic, the benefits of the flipped classroom approach have been well documented. Student learning is higher under this approach, as evidenced by exam and test scores and student satisfaction (Lag and Saele 2019).

Contributors noted the benefits of having created resources such as recorded lectures, recorded examples, and additional assessments. According to Contributor 12, “I developed video lectures going through the relevant slides, along with transcripts for hearing-impaired students. I also created more pieces of assessment for each course and subsequently reduced the weighting of examinations. The implications of these changes means that I can supplement the course I teach in the future with materials I have already developed.” Once made, these resources are at the instructors' disposal for future years, meaning that it will be easier for professors to implement or continue to use a flipped classroom approach.

Just under half of the contributors identified the expectation that, in the future, technology will be used more and a hybrid approach will be part of their teaching. Contributor 13 stated, “Given the potential for larger class sizes online, I personally suspect that online course delivery will be far more common in the future than it was in the past.” According to Contributor 2, “I believe, in the long term, teaching will see revolutionary changes. The notion of flexible and hybrid learning, as well as micro credentials, will disrupt traditional learning. Students will want teaching options and potentially even shorter degrees. The government is certainly putting emphasis on ‘ready soon’ careers.”

Although contributors identified that changes to the teaching environment in the future are likely, attitudes toward a more online-based format of learning were mixed: “It is disappointing that many of my colleagues plan to continue teaching online this fall not because of a fear of COVID-19, but because it is easier for them to give a lecture once rather than multiple times to different sections of students. Since they were forced to pivot their course online in 2020, they do not want to go back to the classroom.…[Students] need to be forced to interact with other people, particularly the shy and introverted students, of which I have many” (Contributor 18). Alternatively, Contributor 23 stated, “Unless advised otherwise by my institution, I will continue to offer a Zoom link to students in order to provide choice in attendance methods for the adult learner. Participation and engagement can be tracked whether the student is in-person or online.”

Other Issues

Mental Health

The amount of stress the pandemic has caused accounting professionals cannot be understated. A large majority of contributors, 17 out of 23, cited stress, anxiety, or a similar issue in their written submission. A study targeting academics conducted before the onset of the pandemic finds that women show higher levels of work stress than their male counterparts in terms of qualitative role overload, quantitative role overload, and role development (Russell and Weigold 2020). Women specifically comment on the “perceptions of pressures for women to take on additional tasks, many of which were consistent with stereotypically feminine roles” (Russell and Weigold 2020, 135). This has been amplified during the pandemic as females have taken on additional caregiving responsibilities. This rise in workload is one reason for the increased mental health issues identified. During the pandemic, in the population at large, one out of four people required mental health services (Cooke et al. 2020). In addition to the obvious short-term implications of stress, the long-term implications of elevated stress are cause for concern as physical well-being is often impacted (American Psychological Association 2018). Accounting academics share the stress and strain the pandemic has caused in comments such as the following: “Learning to use our learning management platforms was incredibly difficult and brought me to tears of frustration many times. From July until Christmas I worked every single day” (Contributor 4); “[My kids] need my constant attention, which is overwhelming” (Contributor 5); and “I feel depleted and unable to give anything more” (Contributor 22).

Most issues found to induce stress in accounting faculty and students in the summer of 2020 related to the switch to online learning and the associated technological issues (Sangster et al. 2020). A year later, my research finds that the issues inducing stress for accounting faculty have broadened. Multiple contributors noted that they are impacted by the uncertainty the future brings in general or are worried about what the future holds for them in their profession. According to Contributor 10, “Low-level anxiety surrounding the future demands and requirements from my employer has impacted other areas of my life. In particular, I have experienced difficulty feeling focused and a decreased ability and energy to take on new projects.” Contributor 17 stated, “My employment contract status is a particularly stressful point for me personally, as my current work and efforts will dictate whether or not I get a new contract.…At this rate, I fear I am going to be another statistic, which is heartbreaking given the commitment and ability I have in this current role.” Other reasons for stress vary from the increased workload, lack of childcare, care required for aging parents, being unable to visit or see family, lack of technical skills or support for technology, student needs, and administration at the postsecondary institutions to general uncertainty related to the pandemic. Contributor 18 noted that administration was trying their best, but it was a challenge: “The information we received from administration would change regularly, so it was difficult to know how we should be expected to teach in the fall 2020. One week we were told to plan for some in-class lectures, the next week we were to teach synchronously, and the following week asynchronously.” The uncertainty makes planning challenging and contributes to the anxiety academics feel. This also coincides with findings showing that women reported greater stress and anxiety at the start of the lockdown compared to men (Fisher and Ryan 2021).

Leaving Academia

Five of the 23 contributors specifically discussed leaving academia themselves or having colleagues leave or consider leaving their institutions. Some postsecondary institutions offered early retirement to certain individuals, while other institutions saw unplanned early retirements during the pandemic. Contributor 18 stated, “I plan to see how this fall term goes. If it is not a satisfying experience, I will move up my retirement date to 2022.” Contributor 13 retired at the end of 2020 but made the decision to teach sessionally during retirement the following year. However, after one year of sessional teaching during the pandemic, the individual made the decision to fully retire: “My decision not to continue to teach sessionally is due primarily to the high levels of stress that I am dealing with, which have been increased by the pandemic.” This corresponds with findings that over half of faculty at postsecondary institutions have seriously considered leaving academia or retiring (Tugend 2020). In this study, 35% of respondents have seriously considered leaving higher education and 38% have considered retiring. The increase in women and/or caregiver academics leaving the profession results in less representation within postsecondary institutions for these equity-seeking groups moving forward.

Other contributors cited the mental health aspect of working in academia during the pandemic: “I am seriously looking to move out of academia as the fissures in the system and overall toxicity are seriously impacting my wellbeing” (Contributor 15). Lastly—and of note as this specifically impacts women—is the loss of contract staff who may not return to academia. In a recent study of over 2,600 Canadian contract academics, 56% identified as women and 35% identified as men (Foster and Bauer 2018). Contributor 15 stated, “Contract staff are a very gender-imbalanced group, and my only female colleagues are in contract positions. Some have had to step back because of lack of childcare options and their income has been cut deeply as contract staff have no benefits to fall back on and no funding is provided for COVID-19 pivots.”

Two additional contributors to the five who identified leaving academia note that they were unsatisfied with the teaching environment created by COVID-19 but did not specifically tie their lack of satisfaction to leaving the profession: “The past year has been, by a wide margin, the most challenging and least satisfying year of my teaching career” (Contributor 14); “[The situation] has made teaching quite dissatisfying” (Contributor 18); “It was soul-crushing to get absolutely no engagement every week” (Contributor 19). Besides the lack of interaction with students, larger class size was also a source of frustration: “I am teaching a class of 700 students. I simply do not have the capacity to accommodate students' needs individually” (Contributor 22).

Loss of Dedicated Work Time

Most contributors mention the shift to working from home. Many of the benefits and drawbacks of working from home identified by contributors are echoed in Xiao et al. (2021). Benefits discussed in the contributions, as well as in Xiao et al.'s (2021) article, include being able to squeeze in midday workouts, not having to commute, and avoiding distractions from coworkers, especially in open plan offices. The cited drawbacks of working from home include lack of opportunities to socialize with colleagues, lack of physical movement leading to weight gain, and challenges in creating work-life boundaries. However, of all the drawbacks of working from home, the most commonly cited was the loss of dedicated work time: “Having the children at home resulted in time being taken away during the day since I had to spend time meeting my children's needs and demands” (Contributor 21).

Academic women's productivity is disproportionately hindered by the enduring inequities in paid and domestic work that are exaggerated in the pandemic (Oleschuk 2020). “Rising care demands created by COVID-19—specifically those brought on by remote working, a lack of childcare, and the virus'[s] particular risk to aging populations—are disproportionately incurred by women and impede their ability to work” (Oleschuk 2020, 503). When additional time is saved from not having to commute to work, women, unlike men, tend to use this additional time for caregiving or housework as opposed to taking time for themselves (Kurowska 2018).

Working from home blurs the boundaries between work and home life, and contributors with school-age children noted, “I have to work in the early mornings and late evenings when my kids are sleeping” (Contributor 5) and, “To adapt, I would work late into the evening/night. Normally I am the most productive during the daytime” (Contributor 12).

In an article in Pivot, McKeon (2021, 44) notes that a US couple who tracked the number of interruptions they faced from their two school-age children on a random morning during the lockdown found that “the average length of an uninterrupted stretch of work time was three minutes, 24 seconds. The longest uninterrupted period was 19 minutes, 35 seconds. The shortest was mere seconds.” This loss of dedicated work time due to disruptions and interruptions, and the blurring of the boundaries of work and home life, are directly tied to the lower productivity many academics experienced over the past year. Contributor 5 noted, “Due to the closure of elementary schools, I have to supervise [my children's] online learning while working a full-time job. Research is a high-cognitive-level task. It is challenging to multi-task while the kids are around, and my children are not old enough to play or study by themselves.…I can barely have 10 minutes of focused time on my teaching and research without any interruption.” The loss of dedicated work time lowers productivity and directly relates to concerns focused on the progress of one's career and job stability.

Issues Specific to Accounting Academics, Women, and Caregivers

Although the issues identified by academics working in the area of accounting are echoed by Canadian academics across other disciplines (Canadian Association of University Teachers 2020), some issues more specifically relate to accounting academics, women, and caregivers.

Accounting Academics

Specific concerns related to academic integrity are prevalent in accounting academia as many students plan to complete the CPA professional program after graduation. Since the foundation of the accounting profession is ethical integrity (Bagri 2016), and 19 of the 23 contributors hold a CPA designation, this may be a reason this issue was a focus in the submissions. Accounting educators know that CPAs and CPA students and candidates are expected to uphold the highest levels of academic honesty and thus called academic integrity “the most pressing issue” (Contributor 2) and “the biggest topic related to changes in education” (Contributor 2). To try and minimize the occurrence of academic integrity issues, many contributors moved to an increased number of assessments and application style questions and exams. The creation of these tools took significant time and did not improve academics' productivity. Contributor 22 stated, “So, beyond the usual time for exam setup that is related to the content, I have had to put a lot of creative thought into developing different types of questions that can be tested in a meaningful way online.” There are also testing challenges for certain courses as “some topics or concepts can only be tested a certain number of ways. In an in-class exam, the professor can control the distribution of exam questions by collecting the exams with the responses. In an online exam, the questions are out there and there is nothing that can be done to prevent distribution of exam questions” (Contributor 13).

Women

The majority of contributors hold the title of instructor/lecturer (39%) or assistant professor (43%) and are in the early (48%) or middle stage (39%) of their careers. As such, concerns about tenure, promotion, and employment were expressed in many of the contributions. The loss of dedicated work time led to loss of promotion and removal from projects for multiple contributors. Contributor 4 noted, “I was turned down for promotion this year, and I believe one part of the problem was that my teaching was viewed as less effective.” According to Contributor 7, “If I am falling behind, as I feel I am, then perhaps tenure is delayed, promotion is delayed, income growth and opportunities are delayed, and pension is reduced. Perhaps tenure does not happen at all.” Worries surrounding employment, and the resulting implications, are of particular concern as the gender balance in the ranks of the professoriate, specifically at the levels of full professor, does not match the gender balance of those achieving master's degrees or PhDs (Council of Canadian Academies 2012).

Caregivers

The loss of dedicated work time is specific to those identifying as caregivers. Not all women are caregivers, and those who are not noted, “The personal changes in my life due to the pandemic have fortunately been minimal” and “Spending day after day working out of the house has not been much of a problem” (Contributor 4). Also, not all caregivers are women. The contributions from three men identifying as being caregivers for children, parents, and disabled spouses are included in this commentary. However, as discussed above, those contributors with caregiving duties found the loss of dedicated work time to be a significant issue and taxing on their mental health.

5 SUGGESTIONS TO ADDRESS IDENTIFIED ISSUES

A variety of measures, as shown in Table 4, were recognized that would help address the issues women and caregivers in accounting academia are facing. The most common suggestions to address the issues identified are discussed under several headings. These headings include: support all around, additional funding, tenure and promotion committees to adjust standards, and option for reduced workload.

| No. | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Support from organization, dean, department, chair | 10 | 43 |

| 2 | Dedicated IT support from institution | 7 | 30 |

| 3 | Additional funding | 6 | 26 |

| 4 | Tenure/promotion committees to adjust standards | 5 | 22 |

| 5 | Option for reduced workload | 5 | 22 |

| 6 | Tenure extension | 4 | 17 |

| 7 | Professional development on various technology | 3 | 13 |

| 8 | Consistency in technology platforms and tools within department | 3 | 13 |

| 9 | Freedom to choose technology platforms and tools | 2 | 9 |

| 10 | Communication from institution about future plans | 2 | 9 |

| 11 | Sharing best practices between academics | 2 | 9 |

| 12 | Keeping K-12 schools open | 2 | 9 |

| 13 | More supports from textbook publishers | 2 | 9 |

| 14 | Fewer online meetings | 2 | 9 |

| 15 | Resource lists of babysitters, cleaning services, and tutors provided by institutions | 2 | 9 |

| 16 | Time to “readjust” to normal life | 1 | 4 |

| 17 | Seeking faculty input in decision-making process | 1 | 4 |

| 18 | Professional development on student assessment options | 1 | 4 |

| 19 | Reduced reliance on student assessment as a form of evaluation | 1 | 4 |

| 20 | Journal editors to adjust revision timelines | 1 | 4 |

| 21 | Additional daycares for school-age children | 1 | 4 |

| 22 | Vacations | 1 | 4 |

| 23 | Data to support decision making | 1 | 4 |

| 24 | Full vaccination | 1 | 4 |

Support All Around

Contributors suggested many ways that the short- and long-term issues identified could be addressed. The number one way that academics identify they would benefit is by receiving support. Ten of the 23 contributors identified this issue and stated that this support should come from their postsecondary institution, dean, department, chair, and the academy. In reality, the support contributors have received is mixed. For example, one dean reached out to offer support and assure faculty that reduced productivity is expected during this time. Contributor 3 noted, “Direct contact from the dean's office and their assurances are helpful.” But another dean's office criticized the department for a failure of the learning management system.

Contributor 8, who is the chair of their department, recognized that “there was an increased level of leadership expected.” The chair is the “sounding board for disappointed, frustrated, and stressed faculty” who are upset by administrative decisions and have many questions that the chair cannot answer. The need for leadership that was identified and executed by this chair was not implemented in the same manner at all institutions. Contributor 15 stated that “the idea of ‘leadership’ is fundamentally misunderstood” and “leadership at all levels has pretty much left it up to the individual to muddle through and make their own adaptations, seeking out their own way forward.” This was echoed by Contributor 16: “I was mostly left to my own devices and unsupported by my institution in terms of direction and access to technology that would be accommodating to all students.” Contributor 16 went on to say that if not for their high level of knowledge relating to technology, they would not have been able to provide students with the course content during the semester.

Similarly, the IT support for faculty has been mixed in its success. One institution provided daily remote teaching drop-in support as well as technical support during exams. Another institution's learning platform shut down multiple times, resulting in lost data. Dedicated IT support is specifically recognized by seven contributors as something that would help academics. This is needed not only by academics, but also by students. The additional time spent by multiple contributors addressing students' IT needs and questions could have been saved with dedicated support available. The time savings would also help lessen contributors' stress levels.

Overall, many contributors acknowledged that simply recognizing the situation would be a step forward: “I would benefit from recognition of the increased workflow and demands for my colleagues and myself” (Contributor 10) and “Some recognition that COVID-19 has impacted caregivers/mothers immensely would be appreciated” (Contributor 17). As the pandemic and its lasting effects stretch into the next academic year, it is important that all levels of an organization identify areas in which they can support faculty both inside and outside of the classroom.

Additional Funding

Additional funding was recognized by several contributors as a way to combat the implications of the pandemic and the increased workload. Some contributors received funding for teaching assistants, seminars, and markers. Contributor 22 noted, “I did receive support for seminars and marking during the past year and this was helpful.” Additional funding is identified as being needed for research assistants, teaching assistants, teaching releases, hiring help at home, supporting remote teaching, research grants, and attending conferences: “The impact of COVID-19 could be addressed by having more opportunities in the future to disseminate research results. This will require additional funding either from research grants or from administration for attendance at conferences” (Contributor 9).

Multiple contributors acknowledged the precarious financial situation many postsecondary institutions found themselves in due to the pandemic. The uncertainty related to enrolment of international students, travel restrictions implemented by the Canadian government, and physical distancing requirements have all cast doubt on current and projected levels of enrolment. This makes it more challenging to ask for and receive additional funds.

Tenure and Promotion Committees to Adjust Standards

The time to apply for tenure has been adjusted at some postsecondary institutions by one to two years. However, at other institutions, requirements have remained unchanged. Besides extending the time to apply for tenure, other adjustments need to be made related to the standards required to achieve both tenure and promotion.

- Student assessments of teaching during the pandemic should not be used in the usual manner. Assessments are noted to be less valid than usual by Contributor 4, who stated, “Students were understandably frustrated, but administrators need to recognize that issues attributable to the circumstances do not accurately reflect the talent of the professor. It is likely to be overly attributed to the professor.” As the circumstances related to the pandemic are outside the control of the instructor, student assessments and evaluations should not be used as a basis for determining teaching skill and ability.

- There needs to be an understanding that some research studies could be permanently shut down—or alternatively, an understanding that some forms of research, like that involving interpersonal relationships, will be less productive due to their nature and the fact that there is no ability to make up for lost time. According to Contributor 9, “My research program had to transition from in-person to virtual interviews. Consequently, the relationship building with the interviewees was limited. Although the interviews were accomplished, the prospects for additional research with those interviewees is limited as relationships were harder to develop meaningfully in a virtual space.”

- There needs to be a reduction in the number of publications required for those working toward tenure during the pandemic. As noted by Contributor 7, “Providing a credit towards tenure could be another solution. For example, if you need five publications but only have four through the period during the pandemic, perhaps an automatic credit of one could be provided to those who have caregiving responsibilities.”

- Tenure should be aligned to the criteria described in the San Francisco Declaration of Research Assessment, which stops the practice of aligning the merits of an individual's research contributions to the journal impact factor (Government of Canada 2020a, 2020b).

In addition to changes suggested to tenure and promotion standards, contributors noted that they would benefit if institutions were proactive in providing women and caregivers with resources to help recover from the pandemic: “Do it proactively, do not make people look for the stuff, they may not even know what to look for or what is available. I know in many cases we can ask for these or other accommodations, but to be honest this is difficult.…I think this should be proactive, so you do not have to out yourself and risk judgment from those around you” (Contributor 7).

Although institutions are currently focused on the impacts of the pandemic, concerns persist as to how long this will last. As noted by Contributor 9, “Hopefully, promotion and other evaluative decisions will be made with the understanding of that lost time. I do have concerns that the impact of pandemic pivots on productivity will be forgotten or inappropriately assessed, which will impact evaluations.” There is recognition among women and caregivers that they have not performed at pre-pandemic levels. According to Contributor 17, “These last two years were crucial for my academic career development, and they have derailed many plans, to say the least. I just hope for some consideration and additional time to meet the plans I had hoped to achieve.” Contributor 5 stated, “In the longterm, I will not be able to compete with other teachers and researchers who do not have to take care of children or other people. My performance might be poorer, and I will be less competitive to get external funding.” Tenure and promotion standards will need to be reconsidered for years to come to ensure all accounting academics impacted by the pandemic are being appropriately assessed.

Option for Reduced Workload

Providing those academics who are performing additional caregiving tasks during the pandemic with the option of a modified workload would be helpful: “A reduced workload would help mitigate exhaustion from working the two full-time jobs of caregiving and teaching” (Contributor 5). The modified workload could be in the form of funding to allow those impacted to hire teaching assistants, research assistants, or markers. Alternatively, funding could be used to pay for domestic help such as caregivers, tutors, and housekeepers. This would free up time for women and caregivers to devote to the additional workload they are facing due to the pandemic.

Suggestions arose that the reduced workload could be a reduction in the number of courses required to be taught. Stated Contributor 22, “Teaching could be counted as more per class, so that effectively professors would be teaching less classes.” This would help take into consideration the additional time spent by instructors on issues arising from the pandemic. Contributor 22 also noted, “A lot of the questions students would normally ask their peers, they ask me. This is fine, but is not something that is considered in the workload allocation.” In addition, “There were a number of students who cheated on the exam. For each one, I needed to write a separate report, which caused a lot of extra work too. None of this is considered in my work allocation” (Contributor 22).

Cutting back service requirements to the bare minimum during the pandemic would reduce individual workloads. This would include allowing academics to reduce or eliminate service outside postsecondary institutions, reduce service within postsecondary institutions to priority committees, and delay nonessential course development. According to Contributor 14, “Looking back over the past year, it seems that the biggest problem has been the unwavering commitment of our institution to go full speed ahead with new course development and implementation. Perhaps the more effective path would have been to put some of these plans on hold for at least a year.…To have a full teaching schedule, combined with developing three courses, all while adjusting from in-person to online teaching, has pushed me to the limit.”

6 CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

The objective of this commentary, and how it contributes to literature in the area of impacts of COVID-19 on Canadian accounting academics, is to document issues cited by those identifying as women and/or caregivers after one year of the COVID-19 pandemic—specifically, recording how these individuals are impacted in the short and longterm. These contributors have also provided suggestions for addressing the issues identified. Both the individual issues identified and the suggestions for improvement should be further researched to ensure equity in postsecondary institutions moving forward.

There are some benefits that have resulted from the pandemic and online learning environment. These include improved teaching and assessment styles, additional research topics identified, new skill development (particularly in information technology), and the ability to virtually attend conferences around the world. Many submissions included messages of hope, such as “although it has been difficult, I feel the year has caused me to grow as an educator” (Contributor 2); “I am grateful to have a whole new set of skills with online tools that I can utilize in different ways to be more effective in my teaching delivery in the future” (Contributor 9); “We all do hope that the research community will come out stronger at the end of the day” (Contributor 11); and “I do believe the worst of the workload is over. We hope for a better tomorrow” (Contributor 14).

However, unlike the “overwhelming message of optimism within the contributions” (Sangster et al. 2020, 436) expressed by accounting academics from around the world in the summer of 2020, one year later that same positive message is not shared. Many women and caregivers who are teaching and researching in accounting had a negative outlook on how their careers and personal lives have been impacted. The negative issues and problems caused by the pandemic are documented in many articles that have been published since 2020. As noted by Leoni et al. (2021, 1306), “The disproportionate impacts of the current crisis on already disadvantaged groups (low-income workers, those in casual/temporary/precarious employment, females, non-whites, migrants and older populations) have significantly deepened both intra- and inter-country social and economic inequalities.”

In the wide range of issues identified overall, many commonalities arise from the contributions. The most common issues recognized by Canadian accounting academics after one full academic year of the COVID-19 pandemic include research concerns related to the stopping or slowing of work, as well as teaching concerns, such as lower productivity despite additional time spent, increased academic integrity violations, and lack of interaction with students. Other significant concerns identified are mental health, the number of academics leaving the profession, and loss of dedicated work time.

Accounting academics require support from their institutions at all levels. This is identified as the number one way that issues related to the pandemic could be addressed moving forward. Dedicated IT support, additional funding, adjustments to tenure and promotion standards, and the option for a reduced workload are also suggested as ways to help accounting academics.

Although many of the issues discussed and suggestions for improvement identified by accounting academics in this commentary echo those cited by Canadian academics in general from one year ago (Canadian Association of University Teachers 2020), another year has passed with women and caregivers being disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The implications of many of the issues identified by the contributors will have long-term impacts, and these issues need to be documented so that they can be addressed. It is important to continue researching the impact of COVID-19 on women and caregivers in accounting academia so the advancement of women in the field continues. After the first year of the pandemic, some individuals remained neutral and one person had a great year, but most individuals had a negative outlook on academia after this time. Given the uncertainty about the duration and magnitude of COVID-19 disruptions going forward, issues that women and caregivers are facing need to be brought to attention. Sharing our problems and focusing on finding solutions together will help create a better future for all accounting educators.

This commentary has limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, the provinces of Quebec, Newfoundland, and New Brunswick are not represented in the contributions. This is because no participants from these provinces expressed interest in writing a contribution after being emailed by the researcher and contacted by CAAA in both English and French. As such, any issues and suggestions unique to these provinces are not represented in this study. Future research should include data from all provinces to further understand how the pandemic is impacting all Canadian accounting academics.

Second, because the contributions are written at one point in time, they do not necessarily reflect all the issues resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. As the pandemic is an evolving and ongoing situation, women and/or caregivers are likely to continue to be impacted in new ways going forward. Future research could assess how women and/or caregivers continue to be impacted in the future. In addition, research should be conducted on how suggestions to improve the problems brought on by the pandemic have been implemented within postsecondary institutions and society at large.

Considering the range of issues identified and the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of future research areas are suggested. These areas include an in-depth study of any of the single issues identified; if, and how, suggestions for help have been implemented; and education in the future.

First, a significant number of separate issues were identified by contributors. Many of these issues are such vast topics that they merit additional research to explore them in greater depth. Topics for future research on specific issues include the explicit factors that caused increased stress and anxiety, detailed reasons why students were unsatisfied with their learning experience, where accounting academics spent all their additional work time, and individuals leaving academia. In addition, research could be conducted specifically based upon demographics such as stage of career or rank within postsecondary institution, size of postsecondary institution, and type of caregiving duties.

Additional research topics addressing specific issues that emerged from the pandemic but which were exacerbated due to current world events, such as the conflict in Ukraine, increasing inflation rates, and higher cost of living, could be proposed.

Second, research needs to be conducted on if, and how, individuals impacted by the pandemic are assisted in accounting academia moving forward. Specific areas of research could include evaluating the workload assignments given to individuals tasked with caregiving duties; assessing the support provided to academics at all levels within postsecondary institutions; determining if, and how, additional funding has been provided to support those most impacted by the pandemic; and evaluating the consistency in learning management platforms used and their effectiveness.