When Peer Recognition Backfires: The Impact of Peer Information on Subsequent Helping Behavior*

Accepted by Leslie Berger. I appreciate guidance from my co-supervisors, Tim Bauer and Adam Presslee, and I appreciate helpful comments from Jillian Adams, Andrew Bauer, Leslie Berger, Ivee Che, Changling Chen, Krista Fiolleau, Hisham Kazi, Ala Mokhtar, Seda Oz, Bradley Pomeroy, Joyce Tian, Adam Vitalis, Shumiao Wang, Alan Webb, Christine Wiedman, Jonathan Yuan, and two anonymous reviewers. I thank the School of Accounting and Finance at the University of Waterloo for funding this study. My experiment received approval from the University of Waterloo Research Ethics Board.

ABSTRACT

enPeer recognition systems (PRS) have gained popularity in recent years as a means for organizations to promote employee helping behavior. However, there are theoretical reasons to believe that peer information that is publicly disclosed in PRS may reduce subsequent helping behavior, and I use an experiment to test my theory. Specifically, I examine a three-employee setting where an employee (the worker) receives no recognition for helping a coworker (the recognizer) but another coworker (the helper) does. I predict and find that the worker's willingness to subsequently help the recognizer/helper is lower when the worker perceives that the worker's initial help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the helper's. I also find that the worker's perception of fairness mediates the process, and the worker's willingness to help the recognizer has a spillover effect on the worker's willingness to help the helper. My study provides the first empirical evidence of the negative impact that PRS have on helping behavior.

RÉSUMÉ

frL'envers de la reconnaissance des pairs : Impact des renseignements relatifs aux pairs sur les comportements d'aide ultérieurs

Les systèmes de reconnaissance des pairs (SRP), qui ont gagné en popularité au cours des dernières années, permettent aux organisations d'encourager les comportements d'aide chez les employés. Il existe toutefois des raisons théoriques de croire que les renseignements sur les pairs qui sont dévoilés publiquement dans les SRP peuvent réduire les comportements d'aide ultérieurs, et j'ai recours à une expérience pour mettre ma théorie à l'épreuve. Plus précisément, j'examine un milieu comptant trois employés où un d'entre eux (le travailleur) n'obtient aucune reconnaissance après avoir aidé un collègue (le reconnaissant), alors qu'un autre collègue (l'aidant) en reçoit. Je prédis et établis que la propension du travailleur à aider ultérieurement le reconnaissant ou l'aidant est plus faible quand le travailleur perçoit que l'aide qu'il a initialement fournie au reconnaissant est plus importante (plutôt que moins importante) que celle fournie par l'aidant. Je montre aussi que la perception qu'a le travailleur de l'équité influence le processus, et que la propension du travailleur à aider le reconnaissant a un effet d'entraînement sur sa propension à aider l'aidant. Mon étude dégage les premières données empiriques concernant l'impact négatif des SRP sur les comportements d'aide.

INTRODUCTION

Peer recognition systems (PRS) are management control systems in which employees can recognize other employees for their workplace efforts (Black 2020). PRS have gained popularity in recent years and are used by many large organizations such as Boeing, Coca-Cola, Amazon, and Google (Bell 2021; SelectSoftwareReviews 2021). Although the advocates of PRS claim that PRS offer several benefits (e.g., reduced employee turnover, improved employee engagement), I explore in this study whether peer information disclosed in PRS can reduce workplace helping behavior.

Workplace helping behavior (herein referred to as “helping behavior”) refers to any assistance or support on work-related problems from one employee to another (Anderson and Williams 1996). Companies prefer employees to help one another, but it is difficult and thus costly to contract on helping behavior because it is difficult for managers to observe employees' helping (Baiman 1990; Holmstrom 1979; Prendergast 1999; Sprinkle 2003). Conversely, it is relatively easy for employees who receive help to recognize those who help them via PRS because they observe the whole helping process, and PRS have made it easy to give recognition (Bell 2021). Anecdotal evidence suggests that some companies have seen their employees become more willing to help others after PRS implementation (Bucketlist n.d.; Cooleaf n.d.; Wayne and Nathaniel 2014; Zappos Insights n.d.). However, it is not clear how representative these success stories are. Some companies have noticed that peer recognitions through PRS are inconsistent due to personal relationship bias and disagreements over the recognition criteria (N. S. Ho and Nguyen 2021). In this study, I go one step further to show that peer information publicly disclosed in PRS may highlight the inconsistency in recognition and reduce helping behavior.

Information contained within PRS includes who gives recognition, who is recognized, and the reason they are being recognized, which allow employees to compare themselves with others when that information is disclosed to all employees (Festinger 1954, 1957; T. H. Ho and Su 2009; Tafkov 2013).1 Applying equity theory (Adams 1963, 1965), I argue that employees compare their help and recognition to that of other employees to determine whether they are treated fairly by those they helped, and that employees reciprocate unfair treatment by reducing subsequent helping behavior. I examine a setting consisting of three employees: the recognizer, the helper, and the worker. The helper and the worker both help the recognizer but only the helper is recognized for helping. The worker is more likely to consider their nonrecognition to be unfair when they perceive that their help exceeds the helper's than when they perceive that their help subceeds the helper's. Furthermore, reciprocity theory suggests that employees maintain a balance in their relationship with others by treating others the way others treat them (Fehr and Gachter 2000). Hence, I predict that the worker's subsequent helping of the recognizer is lower when the worker perceives that their initial help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the initial help of the helper.

I also predict a similar result for the worker's subsequent helping of the helper. The worker is more likely to develop malicious envy toward the helper when they perceive that their help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the helper's because of their desire to be recognized and their perceived lower level of control over the situation. Unlike benign envy, which motivates one to acquire more for oneself, malicious envy drives the worker to act negatively toward the helper.

I conduct a 2 (Relative Initial Help) × 2 (Helping Target) mixed experiment with 202 online Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers. The dependent variable is subsequent help. I develop the experiment scenario based on the three-employee setting described above. All the participants assume the role of the worker, read a vignette describing the scenario, and determine their subsequent willingness to help the recognizer and the helper. When describing the scenario, I hold constant in all conditions that the participants do not receive recognition. The between-group variable is the worker's relative initial help level (More: more than the helper's initial help; Less: less than the helper's initial help) and the within-group variable is the target of subsequent helping (Helping Target: Recognizer and Helper).

The results support both of my predictions but only support my theory underlying Hypothesis 1 (H1). I do not find evidence for my theory behind Hypothesis 2 (H2). The worker's subsequent help is lower for both the recognizer and the helper when their initial help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the helper's. Based on path analysis, perceived fairness of the recognition mediates the effect of relative initial help on the subsequent helping of the recognizer and envy does not mediate the effect of relative initial help on the subsequent helping of the helper. Instead, the change in subsequent helping of the helper results from a spillover of the change in a willingness to help the recognizer.

My study contributes to theory and practice in three ways. First, my study contributes to the peer recognition literature by examining the efficacy of public PRS. The extant literature has just begun to explore the efficacy of PRS: Black (2020) examines the effect of private peer recognition on helping behavior; Evans et al. (2022) focus on the effect of the leaderboard feature of PRS on helping behavior; Burke et al. (2022) study the effect of PRS on help-seeking behavior; and N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021) investigate managers' struggles with PRS implementation in practice. My study extends the literature by investigating how public peer information may trigger a drop in helping behavior. In particular, my paper builds on themes discussed in N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021) to show potential consequences of some of the problems that managers have seen during PRS implementation. I find that publicly disclosed peer information can reduce employees' willingness to help their peers. This effect is not limited to those who give unfair recognition—it can spill over to other employees.

Second, my study expands on the helping literature (Black et al. 2019; Branas-Garza 2007; Brown et al. 2022; Deckop et al. 2003; He et al. 2021) by offering evidence on both a direct effect (Hypothesis 1 (H1)) and a spillover effect (Hypothesis 2 (H2)) of public peer information. Although my results only suggest that envy does not mediate the spillover effect and does not pinpoint any other theory behind such spillover, my results do hint that perceptions of organizational justice could drive the spillover effect. Prior literature shows similar spillover effects among employees, organizations, and customers: employees who are treated more unfairly by managers tend to treat customers more unfairly, and employees who are treated more fairly by customers tend to help coworkers more often (Bowen et al. 1999; Folger et al. 2010). However, researchers have not shown how unfair treatment from employees can affect other employees' perceptions of organizational justice, which affects their subsequent helping behavior. My study offers initial evidence on the spillover effect, and future research can test whether the spillover effect is driven by employees' perception of organizational justice.

Finally, my study contributes to practice by demonstrating the negative impact of peer information. The anecdotal evidence of the positive impact of PRS may indicate a blend of both positive impact and negative impact, meaning that managers may not have achieved optimal outcomes with PRS. Although this may be the case for many organizations given the wide usage of public PRS, managers may not be aware of the problem. The media has not brought this to managers' attention, and it is difficult for managers to notice employees who provide help but are not recognized, as managers have limited ability to observe employees' helping behaviors in the first place. My results provide initial evidence of a negative impact of public peer information, and future research may use field data to further validate and quantify the negative impact.

BACKGROUND

The use of recognition has a long history. For instance, the US Army started to recognize soldiers' heroic acts with the Medal of Honor in the 1860s (Congressional Medal of Honor Society n.d.). Companies recognize employees for helping others and for achieving outstanding performance; employee recognition has grown into a $46-billion market (Bersin 2012; Black 2020; Frey and Gallus 2017; Quinn 2021; Zappos Insights n.d.). The traditional employee recognition process uses a top-down approach, where managers (and executives) give recognition to their subordinates. Although prior literature suggests that this type of employee recognition has several benefits, such as reinforcing work attendance and motivating higher effort (Burke 2018; Wang 2017; Werner 1992), the top-down approach of employee recognition has limitations.

Under a top-down approach, a manager's ability to capture and recognize desirable behavior or performance of their subordinates is limited by their ability to observe such desirable outcomes (Agrawal 2018; O'Donnell 2021). Because managers often have limited time to spend around their subordinates, their subordinates' recognition-deserving behavior can be costly to observe. In contrast, employees routinely spend time with their coworkers. They have more opportunities to witness their coworkers' recognition-deserving behavior and they can easily give recognition via PRS. Thus, it is not too surprising that in the past decade there has been a rapid growth in the number of organizations adopting PRS. In 2013, World at Work (2013) reported that 42% of the employers surveyed used PRS. In another survey conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM 2018), 80% of HR professionals surveyed claim that their companies use PRS. Successful implementation of PRS usually leads to high participation, with some companies reporting that 95% of employees use PRS each month (SelectSoftwareReviews 2021; Wilson 2019). Employees find peer recognition desirable, and some companies have seen the positive impact of peer recognition (Achor 2016; Brownlee 2019; Wickham 2022).

But as the old saying goes, there are two sides to every coin. What could backfire with PRS? Could the downside of PRS go unnoticed by management? In this study, I experimentally investigate one potential negative impact of PRS on helping behavior. Helping behavior refers to any assistance or support on work-related problems from one employee to another (Anderson and Williams 1996). Companies prefer employees to help one another, but it is difficult and thus costly to contract on helping behavior because employees' helping is difficult to observe by management (Baiman 1990; Holmstrom 1979; Prendergast 1999; Sprinkle 2003). As the number of companies adopting PRS continues to grow, recent anecdotal evidence suggests that some companies have seen their employees become more willing to help others after PRS implementation (Bucketlist n.d.; Cooleaf n.d.; Wayne and Nathaniel 2014; Zappos Insights n.d.). However, it is not clear how representative these successful examples are. N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021), for example, reveal from interviews that some companies struggle with their PRS. In particular, N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021) suggest that employees' recognition of other employees is biased toward personal relationships and that employees tend to disagree on what should be recognized. Thus, evidence from practice indicates that companies may not be able to promote helping behavior with PRS. It is important, then, to understand the effect of inconsistent peer recognition on helping behavior.

Prior literature has investigated various ways to motivate helping behavior as well as factors that can reduce helping behavior (Bamberger and Belogolovsky 2017; Branas-Garza 2007; Guchait et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2010; Sawyer et al. 2021). As for the efficacy of PRS on helping and help-seeking behavior, researchers have shown that group identity, monetary rewards, and design of a leaderboard feature can affect whether PRS promotes helping behaviors (Black 2020; Burke et al. 2022; Evans et al. 2022). My study extends the literature by examining the effect of peer information that has been disclosed in public acts of peer recognition, wherein peer information is conveyed to all employees. In this case, employees can compare their situations with those of other employees and conclude whether they are treated fairly depending on whether or not the recognition is given in a consistent manner. Employees who feel unfairly treated may reduce their helping behavior.2

I examined 24 popular PRS platforms used by more than 9,000 companies worldwide, and 23 (96%) of them make peer recognition public by default (see Table 1). Building on the popularity of public peer recognition, I consider a setting consisting of three employees: the recognizer, the helper, and the worker. The helper and the worker both help the recognizer but only the helper is publicly recognized for helping.3 Within this setting, I focus on subsequent helping behavior of the worker after they learn about peer information. There are two advantages of using this setting. First, it allows me to study the effect of peer information on employees' willingness to help both the recognizer and the helper. Second, because the decision to recognize the worker and the decision to recognize the helper are made by one recognizer instead of two recognizers, the worker cannot attribute the variance in the recognition outcomes to different recognition criteria used by different recognition decision-makers.

| Panel A: Number of company customers and basic features | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | Estimated number of company customers | Disclosed to other employees by default? (Y/N) | Reward | ||

| Recognizer name | Recognizee name | Reason for recognition | ||||

| 1 | Kazoo | ≥600 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 2 | Bonusly | ≥100 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 3 | Reward Gateway | ≥1,900 | Y | Y | Y | Customizable |

| 4 | Bucketlist | ≥10 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 5 | Assembly | ≥2,400 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 6 | Workvivo | ≥10 | Y | Y | Y | Award nomination |

| 7 | Kudos | ≥80 | Y | Y | Y | Customizable |

| 8 | Motivosity | ≥7 | Y | Y | Y | Cash |

| 9 | Blueboard | ≥200 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 10 | Preciate | ≥2,200 | Y | Y | Y | Badges and stickers |

| 11 | AwardCo | ≥141 | Y | Y | Y | Cash |

| 12 | Guusto | ≥160 | Y | Y | Y | Cash |

| 13 | Snappy | ≥200 | N | N | N | Merchandise |

| 14 | Nectar | ≥5 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 15 | Fond | ≥6 | Y | Y | Y | Customizable |

| 16 | Xoxoday Empuls | ≥800 | Y | Y | Y | Customizable |

| 17 | HeyTaco! | ≥25 | Y | Y | Y | Badges and stickers |

| 18 | Cooleaf | ≥6 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 19 | Bonfyre | ≥6 | Y | Y | Y | Badges and stickers |

| 20 | Bravo | ≥1 | Y | Y | Y | Appreciation card |

| 21 | Reflektive | ≥12 | Y | Y | Y | Positive feedback in performance review (formal) |

| 22 | Vantage Circle | ≥54 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| 23 | WorkStride | ≥150 | Y | Y | Y | Cash |

| 24 | Achievers | ≥45 | Y | Y | Y | Reward points |

| Panel B: Frequency of disclosure types | |

|---|---|

| Disclosure type | Frequency |

| Recognizer name, recognizee name, and reason for recognition—public | 23 |

| Recognizer name, recognizee name, and reason for recognition—private | 1 |

| Total | 24 |

| Panel C: Frequency of reward types | |

|---|---|

| Reward type | Frequency |

| Appreciation card | 1 |

| Award nomination | 1 |

| Badges and stickers | 3 |

| Positive feedback in performance review (formal) | 1 |

| Cash | 4 |

| Customizable | 4 |

| Merchandise | 1 |

| Reward points | 9 |

| Total | 24 |

-

Notes: When companies do not state how many customers use their platform, I take the minimum number of the company's customers supported by the facts on the websites. For example, if a company states that its customers are from more than 100 countries, then I put “≥100.” If a company only has a few companies listed as their customers without stating the number of company customers, then I count the number of customers listed and use that number. HeyTaco does not mention any companies using it, but it mentions that more than 5,000 teams from small businesses and Fortune 500 companies use it. I estimated the number of company users assuming there are 200 teams for each company user of HeyTaco. The 24 samples identify at least 9,118 companies using PRS.

The table is based on information collected from the following web pages:

- https://www.selectsoftwarereviews.com/buyer-guide/employee-rewards-recognition

- https://www.kazoohr.com/why-choose-kazoo

- https://go.bonus.ly/schedule-a-peer-recognition-demo?utm_campaign=rewards&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=ssr&ssrid=ssr

- https://www.rewardgateway.com/

- https://bucketlistrewards.com/employee-recognition-select-software/?ssrid=ssr

- https://www.joinassembly.com/?utm_source=ssr&ssrid=ssr

- https://www.workvivo.com/communication-platform/

- https://www.kudos.com/product/recognition/

- https://www.motivosity.com/

- https://www.blueboard.com/products/spot-recognition

- https://join.preciate.com/en/preciate-recognition

- https://www.award.co/recognize

- https://gifted.co/

- http://www.guusto.com/

- https://www.meetsnappy.com/

- https://snacknation.com/blog/employee-recognition-software/

- https://try.nectarhr.com/?utm_campaign=SnackNation&utm_source=snacknation&utm_medium=partner&utm_content=employee-recognition-software

- https://www.fond.co/offer/home/?utm_source=SnackNation&utm_medium=Referral&utm_campaign=Content%20Partnership&utm_content=Employee%20Recognition%20Software

- https://www.xoxoday.com/empuls-features/employee-recognition?utm_medium=BestEmployee_Lsiting3&utm_source=SnackNation_Listing3&utm_campaign=SnackNation_Listing3&utm_keyword=undefined&utm_matchtype=undefined&utm_device=undefined&utm_position=undefined&utm_ad_copy=undefined

- https://www.heytaco.chat/

- https://www.cooleaf.com/

- https://bonfyreapp.com/recognition

- http://bravo.pozitive.io/

- https://www.reflektive.com/

- https://www.vantagecircle.com/

- https://www.workstride.com/programs/employee-recognition/

- https://www.achievers.com/platform/recognize/

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Social Comparison in PRS

The peer information disclosed in PRS helps employees make comparisons between themselves and others. Social comparison theory suggests that individuals use comparison results to update their self-image and that they constantly monitor their self-image because maintaining a good self-image is important to them, and by outperforming others they can support their good self-image (Festinger 1954, 1957; T. H. Ho and Su 2009; Tafkov 2013). In other words, there is competition for good self-image that drives social comparison. Tafkov (2013) identified three conditions determining the intensity of the competition: task comparability, (comparison) target comparability, and importance of the comparison domain. These conditions can be met for PRS and helping behavior.

First, employees receive information about their coworkers' helping behavior in PRS and can compare their levels of helping with such information. For instance, programmers may spend 15 minutes creating a few lines of code for coworkers that they do not know how to write. Although 15 minutes may not be long, providing such help requires advanced coding knowledge and more creativity. Hence, the amount of help may be perceived to be high. Alternatively, employees in a non-inventory-management department could spend a whole weekend helping their coworkers in an inventory-management department complete inventory counts. Although inventory counts may not require much knowledge, the time spent indicates a high amount of effort. Thus, the amount of help may be considered high as well. Helping behaviors involve multiple dimensions—some are common for all kinds of helping (e.g., knowledge/ability requirements, time spent by help provider, and time saved by help receiver) and some are unique to only one kind or a few kinds of helping (e.g., accuracy of information shared). Lipe and Salterio (2000) find that superiors' evaluations are only affected by common measures of performance, not by unique measures of performance. In a similar vein, I argue that employees are likely to focus on common dimensions of helping behaviors when they assess level of helping and compare helping behaviors. More importantly, these common dimensions provide multiple ways to compare helping behaviors. Employees do not need to agree on how to compare helping behaviors—they may pick their preferred way of comparing helping behaviors. This does not lower the comparability of helping behaviors for them. Rather, it increases the likelihood that employees will disagree on who helps more and who helps less.

Second, coworkers can be comparable targets for employees because of many things they have in common. Employees and their coworkers have similar positions, receive similar pay, and work in the same culture. In some cases, they do the same set of tasks at work and report to the same supervisor. Despite the fact that some differences exist among coworkers, many prior studies provide evidence that employees choose their coworkers for both work-related and non-work-related comparisons (Anwar et al. 2016; Brockner 1990; Shah 1998; Shin and Sohn 2015; Smucker 2001).

Finally, employees value peer recognition. According to a survey conducted by Reward Gateway (2018), lack of recognition (40%) is among the top three reasons why employees feel demotivated. Another survey conducted by Achievers (2020) shows that 36% of employees consider quitting their job because of a lack of recognition, making it the number one reason why employees consider quitting. Correspondingly, JetBlue saw a 3% increase in retention and a 2% increase in engagement for every 10% increase in recognition upon implementing its PRS (Achor 2016). If employees at JetBlue did not care about peer recognition, JetBlue would not have seen this positive impact of PRS. Given that Tafkov's (2013) three conditions can be met, I expect the comparisons among employees within a PRS will be frequent and extensive.

Subsequent Helping of the Recognizer

The comparisons enabled by PRS influence a worker's assessment of how fairly they are treated, which drives the worker's subsequent helping of the recognizer. Employees care about fairness and when they compare themselves with others, they assess whether they are treated fairly (Adams 1965; Simons and Roberson 2003). Equity theory suggests that employees use the relationship between their help (input) and recognition (outcome) for this comparison, where a consistent relationship indicates fair treatment (Adams 1963, 1965). In this study, I refer to this relationship between help and recognition as a recognition threshold due to the dichotomous nature of recognition.

In my setting, the outcomes are fixed—the worker is not recognized whereas the helper is recognized. Thus, the worker will judge the consistency of the recognizer's recognition threshold by comparing the perceived amount of help they provide to the recognizer versus the perceived amount of help that the helper provides to the recognizer. If the worker perceives that they provided less help than the helper did, the worker may conclude that their nonrecognition is fair—the inferred justification is that their help is too little to be recognized. In contrast, if the worker perceives that they provided more help than the helper, the worker is likely to conclude that the recognizer is being unfair.

Assessments of fairness drive the worker's subsequent helping of the recognizer in a reciprocal manner. Reciprocity is a norm where, if an individual receives kind/unkind acts from another, the relationship between them becomes imbalanced until the individual responds with kind/unkind acts to restore the balance of the relationship (Fehr and Gachter 2000).4 Such a norm assures those who help that they can expect their favor to be returned in the future, and coworkers rely on this norm to guide their actions in the absence of formal control (Blau 1964; Deckop et al. 2003; Gouldner 1960; Selznick 1994). When the worker perceives that the worker's initial help is more than the helper's initial help, the worker is more likely to conclude that the recognizer is being unfair by recognizing the helper but not recognizing the worker. To reciprocate the perceived unfair treatment, the worker will be less willing to help the recognizer in the future. Conversely, if the worker perceives that the worker's initial help is less than the helper's initial help, the worker likely has no reason to reduce their subsequent helping of the recognizer. Hence, I predict the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).In a three-employee setting where the worker and the helper help the recognizer but only the helper is recognized by the recognizer, the worker's subsequent helping of the recognizer is lower when the worker perceives that the worker's initial help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the helper's initial help.

Subsequent Helping of the Helper

Next, I consider the worker's subsequent behavior of the helper. Unlike the recognizer, the helper has no action directed toward the worker. This means that the worker has neither a favor to return nor a score to settle with the helper. As a result, reciprocity theory does not predict changes in the worker's subsequent helping behavior toward the helper. However, envy may cause a change in the worker's subsequent helping behavior toward the helper.

Envy is a negative emotion that an individual can experience from a perceived inferiority resulting from being compared with those who possess something that the individual desires but does not have; envy can occur between individuals with perceived similarities such as coworkers (Kim et al. 2010; Parrott and Smith 1993; Salovey and Rodin 1984; Schaubroeck and Lam 2004; Smith and Kim 2007). Research has identified two forms of envy: benign envy and malicious envy (Foster 1972; Lange and Crusius 2015; Silver and Sabini 1978; Smith and Kim 2007). Benign envy prompts envious individuals to acquire more for themselves whereas malicious envy leads envious individuals to react negatively toward envied individuals (Foster 1972; Lange and Crusius 2015; Silver and Sabini 1978; Smith and Kim 2007; Van de Ven et al. 2009). Prior literature also suggests that malicious envy is more likely provoked than benign envy when envious individuals perceive that envied individuals do not deserve the advantage/achievement and when envious individuals find themselves lacking control over the situation (Montal-Rosenberg and Moran 2020; Van de Ven et al. 2012).

In my setting, the worker may envy the helper because recognition is desirable to both the worker and the helper, but only the helper receives it. This envy is also more likely to be malicious when the worker perceives that their initial help exceeds the helper's because (i) the worker will perceive the helper to be less deserving of recognition, and (ii) the worker will conclude that they cannot control whether they receive recognition, seeing that more help does not lead to a higher chance of receiving recognition. In this case, the imbalance between the initial help provided and the recognition received drives the worker to achieve mental balance by reducing the likelihood of helping the helper in the future (Cohen-Charash and Mueller 2007; Heider 1958; Kim et al. 2010; Montal-Rosenberg and Moran 2020; Smith 2000). In contrast, when the worker perceives that their initial help is less than the helper's, the difference in recognition can be justified by the difference in help provided, and the worker may not reduce subsequent helping behavior of the helper. Hence, I predict the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).In a three-employee setting where the worker and the helper help the recognizer but only the helper is recognized by the recognizer, the worker's subsequent helping of the helper is lower when the worker perceives that the worker's initial help exceeds (vs. subceeds) the helper's initial help.

METHOD

Overview

I conduct a 2×2 mixed experiment using MTurk workers as participants.5 The first factor is a between-group manipulation of the worker's relative initial help level (More: more than the helper's initial help; Less: less than the helper's initial help). The second factor is a within-group measure of the worker's subsequent helping behavior toward the recognizer and the helper (Helping Target: Recognizer and Helper). The dependent variable is subsequent help. I hold constant across all conditions that the helper is recognized but the worker is not. Participants are randomly assigned to one of the two relative initial help conditions, assume the role of the worker at a fictitious company, read through the scenario (written based on my setting of interest), and proceed to a knowledge check. Participants who pass the knowledge check questions on their first try proceed immediately, whereas the rest of the participants review correct answers to all knowledge check questions before proceeding. After the knowledge check, participants make decisions on their subsequent willingness to help the recognizer and the helper. The post-experiment questionnaire then measures the hypothesized mediators (fairness and envy) and ask about demographic information.

Scenario Description

I develop the experiment scenario based on my setting of interest, where participants take on the role of the worker. I instruct participants to imagine working for a fictitious company with two other employees, Richard (the recognizer) and Harry (the helper). Participants are told that the company uses a PRS and that the PRS discloses peer information to all employees when employees recognize their peers. I add a general description of how the PRS works at the company based on my observations from 24 popular PRS that I examined previously (see Table 1).6 The scenario then states that Richard has recognized Harry but not the participant. Finally, participants are informed of their perceived initial help level relative to Harry's initial help level.7 As previously discussed, perceived similarity between the participants and the helper is critical for a strong test of my theory. Hence, I make it explicit to participants that they are to see many similarities between Harry and themselves.

The scenario has five key information components: (i) the peer information contains three pieces (name of the employee giving recognition, name of the employee receiving recognition, and the reason for the recognition); (ii) the recognition is public; (iii) the recognizer gives recognition; (iv) the helper receives recognition; and (v) the participant provides less (more) help. I use five knowledge check questions to ensure participants understand the five key information components. For each knowledge check question, if a participant does not get the correct answer the first time, the correct answer is immediately shown to the participant so that they have a second chance to learn about the corresponding key information component.

Independent and Dependent Variables

I manipulate between-participants relative initial help (Relative Initial Help) at two levels—less than the helper's initial help (Condition 1: Less)—and more than the helper's initial help (Condition 2: More). To manipulate Relative Initial Help, the participants are told, “You believe you provided less (more) help to Richard than Harry did.”

- Moving forward, I am willing to help Richard (Harry) if he falls behind in his work.

- Moving forward, I am willing to share my expertise with Richard (Harry).

- Moving forward, I am willing to help Richard (Harry) if he has work-related problems.

Note that the Helping Target is measured within participants using different wordings in these Likert scale items. I counterbalance questions for the two dependent variables to avoid order effects in response to the dependent variable questions.

Mediators

My theory suggests that fairness (Fairness) and envy (Envy) mediate the effect of relative initial help on subsequent helping of the recognizer and the helper, respectively. Consistent with common practice in behavioral accounting research (Asay et al. 2022), I measure my process variables in the post-experiment questionnaire instead of before the dependent variable questions to prevent the mediator variable questions from contaminating the measurement of the dependent variable.

I use one 7-point Likert scale item adapted from Colquitt (2001) to measure participants' perceived fairness (Fairness). Participants read the statement, “Richard's decision of not recognizing me is justified” and indicate their level of agreement on a scale of −3 (strongly disagree) to +3 (strongly agree). This measure draws participants’ attention to the fairness reflected in the relationship between help and recognition.

- I envy Harry because he receives recognition.

- I wish to take the recognition away from Harry.

- Envious feelings cause me to dislike Harry.

Statement (a) measures whether the participants envy Harry, and statements (b) and (c) measure whether the envy is malicious or not.

RESULTS

Participants

Bentley (2021) reports that 43 experiments using MTurk workers have on average 217 participants in total and 52 participants per experimental condition. He further suggests using 112–221 participants for a main effect (56–111 per condition) and 325–584 for an ordinal interaction (82–146 per condition). Following his suggestion, I recruit 202 participants for the study.9 In addition, I follow the recommendation by Peer et al. (2014) to use only MTurk workers that have completed more than 500 Human Intelligence Tasks with approval rates of higher than 95%. All participants are more than 18 years old and currently live in the United States.

Data collection was completed over four days. Participants earned USD$2.00 for participation and, on average, it took them 224.1 minutes to complete the experiment.10 Out of 202 MTurk workers who participated in this experiment, 130 (64.4%) are male, 70 (34.7%) are female, and 2 (0.9%) participants prefer not to disclose their gender. Participants' average age is 39 years and average full-time work experience is 13 years. Regarding participants' current or most recent jobs, the majority (50.5%) are at the middle-management level, 9.9% are at the upper-management level, and the remainder are either at the staff level (26.2%) or the lower-management level (13.4%). More than half of the participants have experience giving/receiving peer recognition (61.9%) or have experience using a PRS (62.4%).11 Responses to these two questions are highly positively correlated (r = 0.87, p < 0.001), suggesting that most of the participants who give or receive peer recognition do so via PRS.12

Because random assignment is critical to concluding on causality (see footnote 6 for a more detailed discussion), I verify random assignment by examining participants' demographics across conditions. Among all the participants, 103 are assigned to the Less condition and 99 are assigned to the More condition. Gender, age, and work experience do not differ by condition (gender: t(200) = 1.49, p = 0.14; age: t(200) = 0.21, p = 0.84; work experience: t(200) = 0.45, p = 0.65). In conclusion, random assignment is effectively achieved.

Preliminary and Descriptive Statistics

I use factor analysis to examine whether the variables that are measured using multiple questions represent a single factor (see Table 2). The three questions measuring Recognizer Help load on a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.12, ordinal alpha = 0.88; Gadermann et al. 2012), and the three questions measuring Helper Help load on a single factor (eigenvalue = 1.67, ordinal alpha = 0.79; Gadermann et al. 2012). The three questions measuring Envy also load on a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.02, ordinal alpha = 0.86; Gadermann et al. 2012).13 Hence, I use the participants' average ratings for Recognizer Help (Recognizer Help Avg), Helper Help (Helper Help Avg), and Envy (Envy Avg) to test my hypotheses.14

| Panel A: Factor loading for willingness to help the recognizer | |

|---|---|

| Recognizer Helpa | |

| Moving forward, I am willing to help Richard if he falls behind in his work. | 0.88 |

| Moving forward, I am willing to share my expertise with Richard. | 0.77 |

| Moving forward, I am willing to help Richard if he has work-related problems. | 0.84 |

| Panel B: Factor loading for willingness to help the helper | |

|---|---|

| Helper Helpb | |

| Moving forward, I am willing to help Harry if he falls behind in his work. | 0.78 |

| Moving forward, I am willing to share my expertise with Harry. | 0.63 |

| Moving forward, I am willing to help Harry if he has work-related problems. | 0.76 |

| Panel C: Factor loading for envy | |

|---|---|

| Envyc | |

| I envy Harry because he receives recognition. | 0.73 |

| I wish to take the recognition away from Harry. | 0.85 |

| Envious feelings cause me to dislike Harry. | 0.83 |

- Notes: I use Oblimin rotation for factor analyses. Panel A displays factor loadings for the three questions measuring Recognizer Help. N = 202. All three questions load on a single factor, explaining 68.3% of the variance. Panel B displays factor loadings for the three questions measuring Helper Help. All three questions load on a single factor, explaining 52.7% of the variance. Panel C displays factor loadings for the three questions measuring Envy. All three questions load on a single factor, explaining 64.9% of the variance. aRecognizer Help contains three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. bHelper Help contains three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. cEnvy contains three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' envy toward the helper. When I perform factor analysis on all six willingness to help items, the six items load on one factor (eigenvalue = 3.47, ordinal alpha = 0.89), explaining 57.4% of the variance. The three items measuring Recognizer Help have factor loadings of 0.88, 0.81, and 0.82; the three items measuring Helper Help have factor loadings of 0.68, 0.66 and 0.67. This shows that Recognizer Help and Helper Help are two levels of a single variable. When I perform factor analysis on the fairness item and the three envy items, the four items load on one factor (eigenvalue = 2.29, ordinal alpha = 0.80), explaining 56.8% of the variance in total. The fairness item has a factor loading of 0.40; the three envy items have factor loadings of 0.72, 0.90, and 0.86. The fairness item has a poor loading and differs from the three envy items (Stevens 1992). When the fairness item is dropped, the ordinal alpha increases to 0.86.

The descriptive statistics of the dependent variables, Recognizer Help Avg and Helper Help Avg, along with descriptive statistics of Fairness and Envy Avg, are displayed in Table 3. Means of Recognizer Help Avg (Less: M = 1.74; More: M = 1.11) and Helper Help Avg (Less: M = 1.75; More: M = 1.44) are both lower in the More condition than in the Less condition. The median of Recognizer Help Avg is lower in the More condition (MED = 1.67) than in the Less condition (MED = 2.00), while the median of Helper Help Avg is the same in both conditions (MED = 1.67). The first and third quantile for both Recognizer Help Avg (Less: Q1 = 1.33, Q3 = 2.33; More: Q1 = 0.33, Q3 = 2.00) and Helper Help Avg (Less: Q1 = 1.33, Q3 = 2.33; More: Q1 = 1.00, Q3 = 2.00) are lower in the More condition than in the Less condition.

| Relative Initial Helpa | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less (N = 103) | More (N = 99) | |||||||||

| M | SD | 25% | MED | 75% | M | SD | 25% | MED | 75% | |

| Recognizer Help Q1 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.10 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Recognizer Help Q2 | 1.70 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.62 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Recognizer Help Q3 | 1.86 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.24 | 1.54 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Recognizer Help Avgb | 1.74 | 1.00 | 1.33 | 2.00 | 2.33 | 1.11 | 1.40 | 0.33 | 1.67 | 2.00 |

| Helper Help Q1 | 1.70 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.36 | 1.16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Helper Help Q2 | 1.63 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Helper Help Q3 | 1.94 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.48 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Helper Help Avgc | 1.75 | 0.78 | 1.33 | 1.67 | 2.33 | 1.44 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 2.00 |

| Fairnessd | 1.31 | 1.40 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.49 | 1.85 | −1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Envy Q1 | 0.53 | 1.94 | −1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.71 | 1.65 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Envy Q2 | 0.13 | 2.27 | −2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.29 | 2.06 | −1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Envy Q3 | −0.29 | 2.05 | −2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 1.91 | −1.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 |

| Envy Avge | 0.12 | 1.89 | −1.67 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 0.37 | 1.66 | −0.67 | 0.67 | 2.00 |

- Notes: The table displays means, standard deviations, medians, first quantile (25%), and third quantile (75%) for the dependent variables and mediating variables across the two conditions (Less and More). N = 202. aRelative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. bRecognizer Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.88) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel A). cHelper Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.79) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel B). dFairness is participants' rating of the perceived fairness (7-point Likert scale, −3 to +3) regarding the recognizer's recognition. eEnvy Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale (−3 to +3) items measuring participants' envy toward the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.86) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel C).

Hypothesis Testing

I am interested in the variances in Recognizer Help and Helper Help across the two experiment groups (between-group variance). However, the variances can also come from participants' inconsistent reactions to Helping Target within each group because participants are nested within the two groups and the willingness to help at both Helping Target levels are measured at the group level. Thus, the error terms of Recognizer Help and Helper Help will be correlated if the data is only analyzed at the between-group level. I examine how consistently the participants answer Recognizer Help and Helper Help questions by calculating the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). The results indicate that participants answer Recognizer Help and Helper Help questions consistently and variance in willingness to help is mostly caused by Relative Initial Help (ICC = 0.753, F = 4.047, p < 0.001).15 This validates my need to employ an analysis technique that accounts for my nested design.

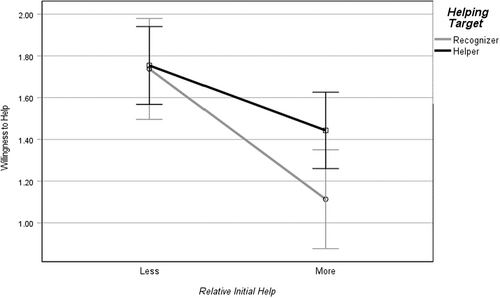

I use a mixed ANOVA because it allows me to decompose the variance in the dependent variables into within-group variance and between-group variance, removing the correlated portion in error terms.16 As shown in Table 4, the 2×2 mixed ANOVA reveals a significant within-group effect of Helping Target (F(1, 200) = 6.27, p = 0.013, = 0.03) and between-group effect of Relative Initial Help (F(1, 200) = 11.67, p < 0.001, = 0.55). However, both effects are qualified by the significant interaction between Helping Target and Relative Initial Help (F(1, 200) = 5.13, p = 0.025, = 0.03). Estimated marginal means suggest that this is an ordinal interaction (Figure 1). Helper Help (Less: M = 1.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) [1.57, 1.94]; More: M = 1.44, 95% CI [1.26, 1.63]) appears to be no less than Recognizer Help (Less: M = 1.74, 95% CI [1.50, 1.98]; More: M = 1.11, 95% CI [0.88, 1.35]) in both conditions, and Recognizer Help decreases more than Helper Help from the Less condition to the More condition.17

| Panel A: Mixed ANOVA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Predictor | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p | Partial |

| Within | Helping Target | 3.03 | 1 | 3.03 | 6.27 | 0.013 | 0.03 |

| Helping Target×Relative Initial Help | 2.47 | 1 | 2.47 | 5.13 | 0.025 | 0.03 | |

| Error | 96.43 | 200 | 0.48 | ||||

| Between | Relative Initial Help | 22.07 | 1 | 22.07 | 11.67 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Error | 378.16 | 200 | 1.89 | ||||

| Panel B: Planned contrasts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helping target | Contrast | Value of contrast | Std. error | df | t | p | Cohen's d |

| Recognizer | Relative Initial Help (Less vs. More) |

0.62 | 0.17 | 200 | 3.64 | <0.001 | 0.51 |

| Helper | Relative Initial Help (Less vs. More) |

0.31 | 0.13 | 200 | 2.35 | 0.020 | 0.33 |

- Notes: Panel A shows the results of a mixed ANOVA (N = 202). Both Helping Target and Relative Initial Help have significant main effects, but the main effects are qualified by the significant interaction effect between Helping Target and Relative Initial Help. Panel B shows the results of planned contrasts. For both Helping Targets (the Recognizer and the Helper), Relative Initial Help has a significant simple effect. However, the simple effect of Relative Initial Help is stronger for the Recognizer. Relative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. Helping Target is either the recognizer (the employee who receives help from both the worker and the helper but only recognizes the helper) or the helper (the employee who provides help and receives recognition).

Notes: This figure displays estimated marginal means of willingness to help the two Helping Targets (the recognizer and the helper) across the two conditions of Relative Initial Help. The error bars represent a 95% CI. Relative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, the participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, the participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. Helping Target is either the recognizer (the employee who receives help from both the worker and the helper but only recognizes the helper) or the helper (the employee who provides help and receives recognition).

H1 predicts that Recognizer Help is lower in the More condition (M = 1.11; SD = 1.40) than in the Less condition (M = 1.74; SD = 1.00). A planned contrast (Table 4, panel B) confirms that Recognizer Help Avg is significantly lower (t(200) = −3.64, p < 0.001, d = 0.51) in the More condition than the Less condition. This result provides support for H1.

H2 predicts that Helper Help is also lower in the More condition (M = 1.44; SD = 1.07) than in the Less condition (M = 1.75; SD = 0.78). A planned contrast (Table 4, panel B) confirms that Helper Help Avg is significantly lower (t(200) = −2.35, p = 0.020, d = 0.33) in the More condition than the Less condition. This result provides support for H2.

Supplemental Analysis

Path Analysis

I examine the processes underlying H1 and H2 using explorative path analysis. Path analysis breaks down the association between independent variables and dependent variables into direct and indirect paths based on theories, and all the paths are simultaneously tested to confirm the theorized relationships between my constructs with less measurement error (Kelly and Presslee 2017; Kline 2011). I conduct path analysis using a maximum likelihood estimation method. All the path estimates are unconstrained.

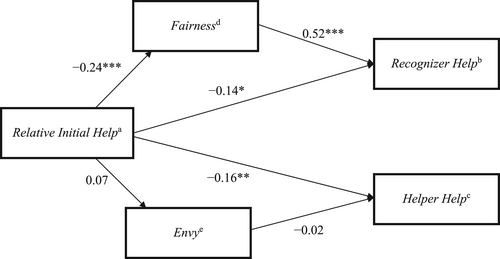

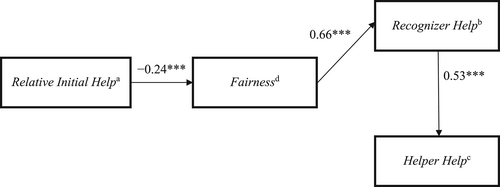

I start with the path model (the whole model) suggested by my hypotheses (Figure 2). My theory underlying H1 suggests that Fairness mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Recognizer Help. My theory underlying H2 suggests that Envy mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Helper Help. The whole model does not fit the data well (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.29, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.88, (2) = 34.69, p < 0.001; Kline 2011). Thus, I do not analyze the path model coefficients. When I consider the path Relative Initial Help → Fairness → Recognizer Help only, the model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.10, CFI = 0.98, (1) = 2.96, p = 0.09; Kline 2011). This supports the process underlying H1 (Relative Initial Help → Fairness: β = −0.24, p < 0.001; Fairness → Recognizer Help: β = 0.66, p < 0.001). Conversely, when I consider the path Relative Initial Help → Envy → Helper Help only, the model does not fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.14, CFI = 0.13, (1) = 5.12, p = 0.02), indicating that Envy does not mediate the process underlying H2.

Notes: This figure presents the path analysis based on the hypothesized dependencies of constructs. aRelative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. bRecognizer Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.88) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel A). cHelper Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.79) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel B). dFairness is participants' rating of the perceived fairness regarding the recognizer's recognition. eEnvy Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' envy toward the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.86) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel C). Per H1, Fairness mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Recognizer Help. Per H2, Envy mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Helper Help. I allow Fairness and Envy to co-vary. I also allow Recognizer Help and Helper Help to co-vary. This analysis uses responses from all participants (N = 202). All paths are estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. All coefficients are standardized. This model does not fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.29, CFI = 0.88, (2) = 34.69, p < 0.001; Kline 2011). When I extract only the path Relative Initial Help → Fairness → Recognizer Help, the model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.10, CFI = 0.98, (1) = 2.96, p = 0.09; Kline 2011). *, **, and *** represent significance levels of 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01, respectively.

Notes: This figure presents the path analysis based on the hypothesized dependencies of constructs with the spillover effect path (Recognizer Help → Helper Help) added. aRelative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. bRecognizer Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.88) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel A). cHelper Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.79) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel B). dFairness is participants' rating of the perceived fairness regarding the recognizer's recognition. eEnvy Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' envy toward the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.86) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel C). Per H1, Fairness mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Recognizer Help. Per H2, Envy mediates the relationship between Relative Initial Help and Helper Help. I allow Fairness and Envy to co-vary. I also allow Recognizer Help and Helper Help to co-vary. This analysis uses responses from all participants (N = 202). All paths are estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. All coefficients are standardized. This model does not fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.18, CFI = 0.98, (1) = 7.603, p = 0.006; Kline 2011). When I extract only the path Relative Initial Help → Fairness → Recognizer Help, the model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.10, CFI = 0.98, (1) = 2.96, p = 0.09; Kline 2011). *, **, and *** represent significance levels of 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01, respectively.

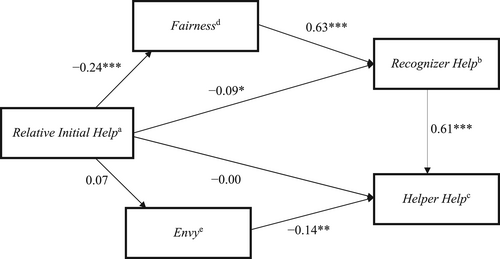

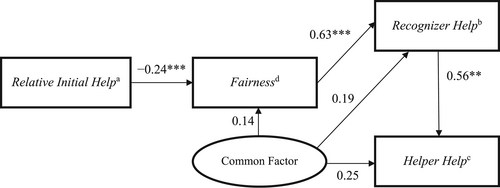

To further explore the process underlying H2, I add an alternative path to the model (Relative Initial Help → Fairness → Recognizer Help): Recognizer Help → Helper Help (Figure 4).18 Under this path, the participants' willingness to help the helper depends on their willingness to help the recognizer. Participants become less willing to help the helper as the change in their willingness to help the recognizer spills over. The model with this alternative path added fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.99, (2) = 3.06, p = 0.22; Kline 2011) and all the correlation coefficients are significant (Relative Initial Help → Fairness: β = −0.24, p < 0.001; Fairness → Recognizer Help: β = 0.66, p < 0.001; Recognizer Help → Helper Help: β = 0.53, p < 0.001). Relative Initial Help has an indirect effect of −0.40 on Recognizer Help (p < 0.001) and an indirect effect of −0.16 on Helper Help (p < 0.001).19 Therefore, path analysis suggests that the lower Helper Help is due to a spillover of lower Recognizer Help.20

Notes: This figure presents the path analysis based on the path identified from stage one (Figure 2 and Figure 3). aRelative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. bRecognizer Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.88) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel A). cHelper Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.79) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel B). dFairness is participants' rating of the perceived fairness regarding the recognizer's recognition. (Recognizer Help → Helper Help) added. For how these constructs are measured, refer to Figure 2. The added path represents the spillover effect of Recognizer Help on Helper Help. This analysis uses responses from all participants (N = 202). All paths are estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. All coefficients are standardized. This model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.99, (2) = 3.06, p = 0.22; Kline 2011). *** represents significance level of 0.01.

Common Method Bias

Common method bias refers to the variance due to measurement rather than the variance of underlying constructs (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Given that I use 7-point Likert scales to measure each of Recognizer Help, Helper Help, Fairness, and Envy from the same source, common method bias could be a threat—it could be that participants are just trying to be consistent in their responses across questions. Following the suggestion of Podsakoff et al. (2003), I use common latent factor analysis, shown in Figure 5. This method has been used by many researchers (Moorman and Blakely 1995; Podsakoff et al. 1990). I add a single unmeasured latent factor with all the measures to capture common method bias and I do not need to identify or measure any specific factor causing common method bias. If the spillover effect is purely explained by common method bias, the path between Recognizer Help and Helper Help will no longer be significant after adding the unmeasured latent factor. The results show the opposite—all the paths remain significant (Relative Initial Help → Fairness = −0.24, p < 0.001; Fairness → Recognizer Help = 0.63, p < 0.001; Recognizer Help → Helper Help = 0.56, p = 0.015). Therefore, common method bias does not explain my results.

Note: This figure presents the path analysis based on the path model presented in Figure 3, with common latent factor to control for common method bias. aRelative Initial Help is manipulated at two levels: Less and More. In the Less condition, participants are told that they provided less initial help than the helper; in the More condition, participants are told that they provided more initial help than the helper. bRecognizer Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the recognizer. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.88) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel A). cHelper Help Avg is the average rating of the three 7-point Likert scale items measuring participants' willingness to help the helper. This average rating is used based on an internal consistency test (ordinal alpha = 0.79) and a polychoric factor analysis (see Table 2, panel B). dFairness is participants' rating of the perceived fairness regarding the recognizer's recognition. This analysis uses responses from all participants (N = 202). All paths are estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. All coefficients are standardized. The unstandardized coefficients of the common factor are constrained to be equal. The unstandardized coefficient of the common factor is 0.24, suggesting that 6% of variance is explained by common method variance. This model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.09, CFI = 0.99, (2) = 5.14, p = 0.08; Kline 2011). *** and ** represent significance levels of 0.01 and 0.05, respectively.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

I use an experiment to examine how peer information disclosed by PRS affects employees' subsequent willingness to help. I consider a setting with three employees: the recognizer, the helper, and the worker. Both the helper and the worker help the recognizer but only the helper is recognized by the recognizer. I find that the worker's willingness to help the recognizer and the helper are both lower when the worker perceives that their initial help exceeds the helper's than when the worker perceives that their initial help subceeds the helper's. Path analysis suggests that fairness mediates the relationship between relative initial help and subsequent helping for the recognizer, but it does not suggest that envy mediates the relationship between relative initial help and subsequent helping for the helper. Instead, I find evidence that the worker's lower level of willingness to help the helper is a spillover from the reciprocal reaction to the recognizer's nonrecognition.

One concern about my study is how likely it is that the recognizer in practice will recognize the helper who helps less and not recognize the worker who helps more, because it seems to be violating the norm of giving recognition. I argue that this situation is likely to occur in practice for two reasons. First, the amount of help in my setting is perceived rather than objectively measured. Employees may disagree over assessed levels of helping. As mentioned earlier, there are multiple common dimensions shared by all types of helping behaviors and employees may attach different weights to each dimension when assessing the amount of help. In addition, a help-providing employee and a help-receiving employee are likely to perceive different help amounts from the same helping behavior, because the help-providing employee's assessment of the impact of their help is likely less accurate than the help-receiving employee's, whereas the help-providing employee's assessment of the input requirements (e.g., knowledge and time) of their help is likely more accurate than the help-receiving employee's. In my setting, if the worker's helping behavior is actually high-cost but low-impact, the recognizer may choose to not recognize the worker because the recognizer thinks the worker's help is less impactful and less costly than the helper's help, but the worker may think that their help is more impactful and more costly than the helper's help. Second, employees may have different recognition criteria, and they may be biased when giving recognition. If the recognizer only gives recognition to their friends or employees from their department and only the helper meets the criteria, the recognizer will only recognize the helper even when the worker provides more help. My arguments are supported by concurrent findings in N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021).21

A second concern about my study is that my results show a negative consequence of using PRS, but most anecdotal evidence discusses the positive impact of PRS. There are two things to consider in order to reconcile these differences. First, it is not clear how representative these stories of successful PRS implementation are, and many PRS software companies have incentives to promote their software by only showing success stories. Second, the evidence of the positive impact of PRS only shows overall results at an organizational level, which may be a blend of both positive and negative impacts of PRS at the individual/group level. Although this seems to make the negative impact of peer recognition less concerning to managers, it does not make my study any less important since my study hints at the existence of a negative impact that can prevent managers from obtaining the maximum value from their PRS without mitigating the risk of having it backfire.

Although my study does not show what managers can do to reduce the risk of public PRS backfiring, I propose two possible measures for managers to consider and for future studies to test their efficacy. First, managers may consider offering more guidelines on what kinds of helping behavior should be recognized and on how to assess levels of help. Such guidelines may lower the propensity of disagreements over assessed levels of help and may prevent a low level of help recognition from frustrating unrecognized employees who previously offered more help. But making these guidelines may prove too costly given the diversity of helping behaviors in the workplace. Alternatively, managers may reduce the disclosed details of helping behavior to a level that prevents employees from making comparisons. However, without any detail of helping disclosed, employees may collude and recognize each other for helping behavior that never occurred. Although this is also possible when details of helping are disclosed, the probability of collusion being detected by other employees is lower than when details of helping are not disclosed. The reason is that employees who work together can observe each other's activities to a certain level.

My study contributes to research and practice in three ways. First, my study contributes to the peer recognition literature by examining the efficacy of public PRS. The extant literature has just begun to explore the efficacy of PRS: Black (2020) examines the effect of private peer recognition on helping behavior; Evans et al. (2022) focus on the effect of the leaderboard feature of PRS on helping behavior; Burke et al. (2022) study the effect of PRS on help-seeking behavior; and N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021) investigate managers' struggles with PRS implementation in practice. My study extends the literature by investigating how public peer information may trigger a drop in helping behavior. In particular, my paper builds on themes discussed in N. S. Ho and Nguyen (2021) to show potential consequences of some of the problems that the managers have seen during PRS implementation. I find that publicly disclosed peer information can reduce employees' willingness to help their peers. This effect is not limited to those who give unfair recognition—it can spill over to other employees.

Second, my study expands on the helping literature (Black et al. 2019; Branas-Garza 2007; Brown et al. 2022; Deckop et al. 2003; He et al. 2021) by offering evidence on both a direct effect (H1) and a spillover effect (H2) of public peer information. Although my results suggest only that envy does not mediate the spillover effect and does not pinpoint any other theory behind such spillover, my results do hint that perceptions of organizational justice could be driving the spillover effect. Prior literature shows similar spillover effects among employees, organizations, and customers: employees who are treated more unfairly by managers tend to treat customers more unfairly, and employees who are treated more fairly by customers tend to help coworkers more often (Bowen et al. 1999; Folger et al. 2010). However, researchers have not shown how unfair treatment from employees can affect other employees' perceptions of organizational justice and change their helping behavior. My study offers initial evidence on the spillover effect, and future research can test whether the spillover effect is driven by employees' perceptions of organizational justice.22

Finally, my study contributes to practice by demonstrating the negative impact of peer information. As discussed earlier in this study, anecdotal evidence of the positive impact of PRS in practice may show a blend of both positive impact and negative impact, meaning that managers may not have achieved optimal outcomes with PRS. While this may be the case for many organizations given the wide usage of public PRS, managers may not be aware of the problem. The media has not brought this to the managers' attention, and it is difficult for managers to notice employees who provide help but are not recognized because of the managers' limited ability to observe employees' helping behaviors in the first place. My results provide initial evidence of the negative impact of peer information and future research may use field data to further validate and quantify the negative impact.

My study has some limitations that can be addressed by future research. First, my study may be vulnerable to common method bias. While I use a few techniques to reduce common method bias—including using questions adapted from prior studies with significant results, putting mediator questions after dependent variable questions, counterbalancing dependent variable questions, and conducting factor analysis and path analysis—I cannot eliminate all of the potential impact of common method bias. For instance, one alternative explanation for the non-finding on the mediating effect of envy is the social undesirability of envy. Envy is often considered to be a bad thing (e.g., Roman Catholics believe that envy is one of the seven deadly sins). As a result, participants may hesitate to admit that they envy others (Foster 1972). However, because I use questions adapted from Lange and Crusius (2015) who find significant results on envy, this is less of a concern. Future research may further examine the role of envy in recognition programs.

Second, the generalizability of my theory is limited by the degree to which Tafkov's (2013) three conditions are met in practice. Although prior studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that Tafkov's (2013) three conditions are met to a certain level in practice, employees may have difficulties assessing inputs/outcomes of helping behavior and not all employees may find peer recognition desirable. Researchers can look further into the applicability of these three conditions in different workplace settings. Particularly, exploring how employees compare helping behaviors and other prosocial behaviors can be quite value-adding.

Third, my study does not consider other channels for gratitude outside PRS. In the workplace, PRS is not the only way for employees to appreciate their peers; they can also say thank you via email or with a cup of coffee. The channels are so diverse that including these channels outside PRS would overcomplicate my study. Future research can examine how these channels outside PRS affect the efficacy of PRS.